History of electrochemistry on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Electrochemistry, a branch of

In 1709, Francis Hauksbee at the

In 1709, Francis Hauksbee at the  Despite the gain in knowledge of electrical properties and the building of generators, it wasn't until the late 18th century that Italian

Despite the gain in knowledge of electrical properties and the building of generators, it wasn't until the late 18th century that Italian  Galvani's scientific colleagues generally accepted his views, but

Galvani's scientific colleagues generally accepted his views, but

In 1800, English chemists William Nicholson and

In 1800, English chemists William Nicholson and  John Daniell began experiments in 1835 in an attempt to improve the voltaic battery with its problems of being unsteady and a weak source of electric current. His experiments soon led to remarkable results. In 1836, he invented a primary cell in which hydrogen was eliminated in the generation of the electricity. Daniell had solved the problem of polarization. In his laboratory he had learned to alloy the

John Daniell began experiments in 1835 in an attempt to improve the voltaic battery with its problems of being unsteady and a weak source of electric current. His experiments soon led to remarkable results. In 1836, he invented a primary cell in which hydrogen was eliminated in the generation of the electricity. Daniell had solved the problem of polarization. In his laboratory he had learned to alloy the  In 1866,

In 1866,

The race for the commercially viable production of

The race for the commercially viable production of  On February 10, 1922, the "

On February 10, 1922, the "

Corrosion-Doctors.org

*A classic and knowledgeable—but dated—reference on the history of electrochemistry is by 1909 Nobelist in Chemistry, Wilhelm Ostwald: Elektrochemie: Ihre Geschichte und Lehre, Wilhelm Ostwald, Veit, Leipzig, 1896. (https://archive.org/details/elektrochemieih00ostwgoog). An English version is available as "Electrochemistry: history and theory" (2 volumes), translated by N. P. Date. It was published for the Smithsonian Institution and the National Science Foundation, Washington, DC, by Amerind Publ. Co., New Delhi, 1980. History of chemistry Electrochemistry Electrolysis

chemistry

Chemistry is the science, scientific study of the properties and behavior of matter. It is a natural science that covers the Chemical element, elements that make up matter to the chemical compound, compounds made of atoms, molecules and ions ...

, went through several changes during its evolution from early principles related to magnets in the early 16th and 17th centuries, to complex theories involving conductivity, electric charge

Electric charge is the physical property of matter that causes charged matter to experience a force when placed in an electromagnetic field. Electric charge can be ''positive'' or ''negative'' (commonly carried by protons and electrons respe ...

and mathematical methods. The term ''electrochemistry'' was used to describe electrical phenomena in the late 19th and 20th centuries. In recent decades, electrochemistry

Electrochemistry is the branch of physical chemistry concerned with the relationship between electrical potential difference, as a measurable and quantitative phenomenon, and identifiable chemical change, with the potential difference as an outco ...

has become an area of current research, including research in batteries

Battery most often refers to:

* Electric battery, a device that provides electrical power

* Battery (crime), a crime involving unlawful physical contact

Battery may also refer to:

Energy source

*Automotive battery, a device to provide power t ...

and fuel cells

A fuel cell is an electrochemical cell that converts the chemical energy of a fuel (often hydrogen fuel, hydrogen) and an oxidizing agent (often oxygen) into electricity through a pair of redox reactions. Fuel cells are different from most bat ...

, preventing corrosion

Corrosion is a natural process that converts a refined metal into a more chemically stable oxide. It is the gradual deterioration of materials (usually a metal) by chemical or electrochemical reaction with their environment. Corrosion engine ...

of metals, the use of electrochemical cells to remove refractory organics and similar contaminants in wastewater electrocoagulation and improving techniques in refining

{{Unreferenced, date=December 2009

Refining (also perhaps called by the mathematical term affining) is the process of purification of a (1) substance or a (2) form. The term is usually used of a natural resource that is almost in a usable form, b ...

chemicals with electrolysis

In chemistry and manufacturing, electrolysis is a technique that uses direct electric current (DC) to drive an otherwise non-spontaneous chemical reaction. Electrolysis is commercially important as a stage in the separation of elements from n ...

and electrophoresis

Electrophoresis, from Ancient Greek ἤλεκτρον (ḗlektron, "amber") and φόρησις (phórēsis, "the act of bearing"), is the motion of dispersed particles relative to a fluid under the influence of a spatially uniform electric fie ...

.

Background and dawn of electrochemistry

The 16th century marked the beginning of scientific understanding of electricity and magnetism that culminated with the production of electric power and theindustrial revolution

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going f ...

in the late 19th century.

In the 1550s, English scientist William Gilbert spent 17 years experimenting with magnetism

Magnetism is the class of physical attributes that are mediated by a magnetic field, which refers to the capacity to induce attractive and repulsive phenomena in other entities. Electric currents and the magnetic moments of elementary particles ...

and, to a lesser extent, electricity. For his work on magnets, Gilbert became known as "The Father of Magnetism." His book ''De Magnete'' quickly became the standard work throughout Europe on electrical and magnetic phenomena, and made a clear distinction between magnetism and what was then called the "amber effect" (static electricity).

In 1663, German physicist

A physicist is a scientist who specializes in the field of physics, which encompasses the interactions of matter and energy at all length and time scales in the physical universe.

Physicists generally are interested in the root or ultimate caus ...

Otto von Guericke

Otto von Guericke ( , , ; spelled Gericke until 1666; November 20, 1602 – May 11, 1686 ; November 30, 1602 – May 21, 1686 ) was a German scientist, inventor, and politician. His pioneering scientific work, the development of experimental me ...

created the first electrostatic generator, which produced static electricity by applying friction. The generator was made of a large sulfur

Sulfur (or sulphur in British English) is a chemical element with the symbol S and atomic number 16. It is abundant, multivalent and nonmetallic. Under normal conditions, sulfur atoms form cyclic octatomic molecules with a chemical formula ...

ball inside a glass globe, mounted on a shaft. The ball was rotated by means of a crank and a static electric spark was produced when a pad was rubbed against the ball as it rotated. The globe could be removed and used as an electrical source for experiments with electricity. Von Guericke used his generator to show that like charges repelled each other.

The 18th century and birth of electrochemistry

Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

in London discovered that by putting a small amount of mercury

Mercury commonly refers to:

* Mercury (planet), the nearest planet to the Sun

* Mercury (element), a metallic chemical element with the symbol Hg

* Mercury (mythology), a Roman god

Mercury or The Mercury may also refer to:

Companies

* Merc ...

in the glass of Von Guericke's generator and evacuating the air from it, it would glow whenever the ball built up a charge and his hand was touching the globe. He had created the first gas-discharge lamp

Gas-discharge lamps are a family of artificial light sources that generate light by sending an electric discharge through an ionized gas, a plasma.

Typically, such lamps use a

noble gas (argon, neon, krypton, and xenon) or a mixture of thes ...

.

Between 1729 and 1736, two English scientists, Stephen Gray and Jean Desaguliers, performed a series of experiments which showed that a cork

Cork or CORK may refer to:

Materials

* Cork (material), an impermeable buoyant plant product

** Cork (plug), a cylindrical or conical object used to seal a container

***Wine cork

Places Ireland

* Cork (city)

** Metropolitan Cork, also known as G ...

or other object as far away as 800 or 900 feet (245–275 m) could be electrified by connecting it via a charged glass tube to materials such as metal wires or hempen string. They found that other materials, such as silk

Silk is a natural protein fiber, some forms of which can be woven into textiles. The protein fiber of silk is composed mainly of fibroin and is produced by certain insect larvae to form cocoons. The best-known silk is obtained from the coc ...

, would not convey the effect.

By the mid-18th century, French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

chemist

A chemist (from Greek ''chēm(ía)'' alchemy; replacing ''chymist'' from Medieval Latin ''alchemist'') is a scientist trained in the study of chemistry. Chemists study the composition of matter and its properties. Chemists carefully describe th ...

Charles François de Cisternay Du Fay

Charles François de Cisternay du Fay (14 September 1698 – 16 July 1739) was a French chemist and superintendent of the Jardin du Roi.

He discovered the existence of two types of electricity and named them "vitreous" and "resinous" (later kn ...

had discovered two forms of static electricity, and that like charges repel each other while unlike charges attract. Du Fay announced that electricity consisted of two fluids: ''vitreous'' (from the Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

for "glass"), or positive, electricity; and ''resinous'', or negative, electricity. This was the "two-fluid theory" of electricity, which was opposed by Benjamin Franklin's "one-fluid theory" later in the century.

In 1745, Jean-Antoine Nollet

Jean-Antoine Nollet (; 19 November 170025 April 1770) was a French clergyman and physicist who did a number of experiments with electricity and discovered osmosis. As a deacon in the Catholic Church, he was also known as Abbé Nollet.

Biography

...

developed a theory of electrical attraction and repulsion that supposed the existence of a continuous flow of electrical matter between charged bodies. Nollet's theory at first gained wide acceptance, but met resistance in 1752 with the translation of Franklin's ''Experiments and Observations on Electricity

''Experiments and Observations on Electricity'' is a mid-eighteenth century book consisting of letters from Benjamin Franklin. These letters concerned Franklin's discoveries about the behavior of electricity, based on experimentation and scient ...

'' into French. Franklin and Nollet debated the nature of electricity, with Franklin supporting action at a distance and two qualitatively opposing types of electricity, and Nollet advocating mechanical action and a single type of electrical fluid. Franklin's argument eventually won and Nollet's theory was abandoned.

In 1748, Nollet invented one of the first electrometers, the electroscope, which showed electric charge using electrostatic attraction

Coulomb's inverse-square law, or simply Coulomb's law, is an experimental law of physics that quantifies the amount of force between two stationary, electrically charged particles. The electric force between charged bodies at rest is conventiona ...

and repulsion. Nollet is reputed to be the first to apply the name "Leyden jar

A Leyden jar (or Leiden jar, or archaically, sometimes Kleistian jar) is an electrical component that stores a high-voltage electric charge (from an external source) between electrical conductors on the inside and outside of a glass jar. It typi ...

" to the first device for storing electricity. Nollet's invention was replaced by Horace-Bénédict de Saussure's electrometer in 1766.

By the 1740s, William Watson had conducted several experiments to determine the speed of electricity. The general belief at the time was that electricity was faster than sound, but no accurate test had been devised to measure the velocity of a current. Watson, in the fields north of London, laid out a line of wire supported by dry sticks and silk which ran for 12,276 feet (3.7 km). Even at this length, the velocity of electricity seemed instantaneous. Resistance

Resistance may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Comics

* Either of two similarly named but otherwise unrelated comic book series, both published by Wildstorm:

** ''Resistance'' (comics), based on the video game of the same title

** ''T ...

in the wire was also noticed but apparently not fully understood, as Watson related that "we observed again, that although the electrical compositions were very severe to those who held the wires, the report of the Explosion at the prime Conductor was little, in comparison of that which is heard when the Circuit is short." Watson eventually decided not to pursue his electrical experiments, concentrating instead upon his medical career.

By the 1750s, as the study of electricity became popular, efficient ways of producing electricity were sought. The generator developed by Jesse Ramsden

Jesse Ramsden FRS FRSE (6 October 1735 – 5 November 1800) was a British mathematician, astronomical and scientific instrument maker. His reputation was built on the engraving and design of dividing engines which allowed high accuracy measureme ...

was among the first electrostatic generators invented. Electricity produced by such generators was used to treat paralysis, muscle spasms, and to control heart rates. Other medical uses of electricity included filling the body with electricity, drawing sparks from the body, and applying sparks from the generator to the body.

Charles-Augustin de Coulomb developed the law of electrostatic attraction in 1781 as an outgrowth of his attempt to investigate the law of electrical repulsions as stated by Joseph Priestley

Joseph Priestley (; 24 March 1733 – 6 February 1804) was an English chemist, natural philosopher, separatist theologian, grammarian, multi-subject educator, and liberal political theorist. He published over 150 works, and conducted exp ...

in England. To this end, he invented a sensitive apparatus to measure the electrical forces involved in Priestley's law. He also established the inverse square law

In science, an inverse-square law is any scientific law stating that a specified physical quantity is inversely proportional to the square of the distance from the source of that physical quantity. The fundamental cause for this can be understoo ...

of attraction and repulsion magnetic poles, which became the basis for the mathematical theory of magnetic forces developed by Siméon Denis Poisson. Coulomb wrote seven important works on electricity and magnetism which he submitted to the Académie des Sciences between 1785 and 1791, in which he reported having developed a theory of attraction and repulsion between charged bodies, and went on to search for perfect conductors and dielectrics

In electromagnetism, a dielectric (or dielectric medium) is an electrical insulator that can be polarised by an applied electric field. When a dielectric material is placed in an electric field, electric charges do not flow through the mater ...

. He suggested that there was no perfect dielectric, proposing that every substance has a limit, above which it will conduct electricity. The SI unit of charge is called a coulomb

The coulomb (symbol: C) is the unit of electric charge in the International System of Units (SI).

In the present version of the SI it is equal to the electric charge delivered by a 1 ampere constant current in 1 second and to elementary char ...

in his honour.

In 1789, Franz Aepinus

Franz Ulrich Theodor Aepinus (13 December 172410 August 1802) was a German mathematician, scientist, and natural philosopher residing in the Russian Empire. Aepinus is best known for his researches, theoretical and experimental, in electricity an ...

developed a device with the properties of a "condenser" (now known as a capacitor

A capacitor is a device that stores electrical energy in an electric field by virtue of accumulating electric charges on two close surfaces insulated from each other. It is a passive electronic component with two terminals.

The effect of ...

.) The Aepinus condenser was the first capacitor developed after the Leyden jar, and was used to demonstrate conduction and induction

Induction, Inducible or Inductive may refer to:

Biology and medicine

* Labor induction (birth/pregnancy)

* Induction chemotherapy, in medicine

* Induced stem cells, stem cells derived from somatic, reproductive, pluripotent or other cell t ...

. The device was constructed so that the space between two plates could be adjusted, and the glass dielectric separating the two plates could be removed or replaced with other materials.

Despite the gain in knowledge of electrical properties and the building of generators, it wasn't until the late 18th century that Italian

Despite the gain in knowledge of electrical properties and the building of generators, it wasn't until the late 18th century that Italian physician

A physician (American English), medical practitioner (Commonwealth English), medical doctor, or simply doctor, is a health professional who practices medicine, which is concerned with promoting, maintaining or restoring health through th ...

and anatomist Luigi Galvani

Luigi Galvani (, also ; ; la, Aloysius Galvanus; 9 September 1737 – 4 December 1798) was an Italian physician, physicist, biologist and philosopher, who studied animal electricity. In 1780, he discovered that the muscles of dead frogs' legs ...

marked the birth of electrochemistry by establishing a bridge between muscular contractions and electricity with his 1791 essay ''De Viribus Electricitatis in Motu Musculari Commentarius'' (Commentary on the Effect of Electricity on Muscular Motion), where he proposed a "nerveo-electrical substance" in life forms.

In his essay, Galvani concluded that animal tissue contained a before-unknown innate, vital force, which he termed "animal electricity," which activated muscle

Skeletal muscles (commonly referred to as muscles) are organs of the vertebrate muscular system and typically are attached by tendons to bones of a skeleton. The muscle cells of skeletal muscles are much longer than in the other types of muscl ...

when placed between two metal probes. He believed that this was evidence of a new form of electricity, separate from the "natural" form that is produced by lightning and the "artificial" form that is produced by friction (static electricity). He considered the brain to be the most important organ for the secretion of this "electric fluid" and that the nerves conducted the fluid to the muscles. He believed the tissues acted similarly to the outer and inner surfaces of Leyden jars. The flow of this electric fluid provided a stimulus to the muscle fibres.

Alessandro Volta

Alessandro Giuseppe Antonio Anastasio Volta (, ; 18 February 1745 – 5 March 1827) was an Italian physicist, chemist and lay Catholic who was a pioneer of electricity and power who is credited as the inventor of the electric battery and the ...

, the outstanding professor of physics at the University of Pavia

The University of Pavia ( it, Università degli Studi di Pavia, UNIPV or ''Università di Pavia''; la, Alma Ticinensis Universitas) is a university located in Pavia, Lombardy, Italy. There was evidence of teaching as early as 1361, making it one ...

, was not convinced by the analogy between muscles and Leyden jars. Deciding that the frogs' legs used in Galvani's experiments served only as an electroscope, he held that the contact of dissimilar metals was the true source of stimulation. He referred to the electricity so generated as "metallic electricity" and decided that the muscle, by contracting when touched by metal, resembled the action of an electroscope. Furthermore, Volta claimed that if two dissimilar metals in contact with each other also touched a muscle, agitation would also occur and increase with the dissimilarity of the metals. Galvani refuted this by obtaining muscular action using two pieces of similar metal. Volta's name was later used for the unit of electrical potential, the volt

The volt (symbol: V) is the unit of electric potential, electric potential difference (voltage), and electromotive force in the International System of Units (SI). It is named after the Italian physicist Alessandro Volta (1745–1827).

Defi ...

.

Rise of electrochemistry as branch of chemistry

In 1800, English chemists William Nicholson and

In 1800, English chemists William Nicholson and Johann Wilhelm Ritter

Johann Wilhelm Ritter (16 December 1776 – 23 January 1810). was a German chemist, physicist and philosopher. He was born in Samitz (Zamienice) near Haynau (Chojnów) in Silesia (then part of Prussia, since 1945 in Poland), and died in Munic ...

succeeded in separating water into hydrogen

Hydrogen is the chemical element with the symbol H and atomic number 1. Hydrogen is the lightest element. At standard conditions hydrogen is a gas of diatomic molecules having the formula . It is colorless, odorless, tasteless, non-toxic, an ...

and oxygen

Oxygen is the chemical element with the symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group in the periodic table, a highly reactive nonmetal, and an oxidizing agent that readily forms oxides with most elements as wel ...

by electrolysis

In chemistry and manufacturing, electrolysis is a technique that uses direct electric current (DC) to drive an otherwise non-spontaneous chemical reaction. Electrolysis is commercially important as a stage in the separation of elements from n ...

. Soon thereafter, Ritter discovered the process of electroplating

Electroplating, also known as electrochemical deposition or electrodeposition, is a process for producing a metal coating on a solid substrate through the reduction of cations of that metal by means of a direct electric current. The part to be ...

. He also observed that the amount of metal deposited and the amount of oxygen produced during an electrolytic process depended on the distance between the electrodes. By 1801 Ritter had observed thermoelectric currents, which anticipated the discovery of thermoelectricity by Thomas Johann Seebeck.

In 1802, William Cruickshank designed the first electric battery capable of mass production. Like Volta, Cruickshank arranged square copper plates, which he soldered at their ends, together with plates of zinc of equal size. These plates were placed into a long rectangular wooden box which was sealed with cement. Grooves inside the box held the metal plates in position. The box was then filled with an electrolyte of brine

Brine is a high-concentration solution of salt (NaCl) in water (H2O). In diverse contexts, ''brine'' may refer to the salt solutions ranging from about 3.5% (a typical concentration of seawater, on the lower end of that of solutions used for br ...

, or watered down acid. This flooded design had the advantage of not drying out with use and provided more energy than Volta's arrangement, which used brine-soaked papers between the plates.

In the quest for a better production of platinum

Platinum is a chemical element with the symbol Pt and atomic number 78. It is a dense, malleable, ductile, highly unreactive, precious, silverish-white transition metal. Its name originates from Spanish , a diminutive of "silver".

Platinu ...

metals, two scientists, William Hyde Wollaston

William Hyde Wollaston (; 6 August 1766 – 22 December 1828) was an English chemist and physicist who is famous for discovering the chemical elements palladium and rhodium. He also developed a way to process platinum ore into malleable ingo ...

and Smithson Tennant, worked together to design an efficient electrochemical technique to refine or purify platinum. Tennant ended up discovering the elements iridium

Iridium is a chemical element with the symbol Ir and atomic number 77. A very hard, brittle, silvery-white transition metal of the platinum group, it is considered the second-densest naturally occurring metal (after osmium) with a density of ...

and osmium

Osmium (from Greek grc, ὀσμή, osme, smell, label=none) is a chemical element with the symbol Os and atomic number 76. It is a hard, brittle, bluish-white transition metal in the platinum group that is found as a trace element in alloys, mos ...

. Wollaston's effort, in turn, led him to the discovery of the metals palladium

Palladium is a chemical element with the symbol Pd and atomic number 46. It is a rare and lustrous silvery-white metal discovered in 1803 by the English chemist William Hyde Wollaston. He named it after the asteroid Pallas, which was itself na ...

in 1803 and rhodium

Rhodium is a chemical element with the symbol Rh and atomic number 45. It is a very rare, silvery-white, hard, corrosion-resistant transition metal. It is a noble metal and a member of the platinum group. It has only one naturally occurring isoto ...

in 1804.

Wollaston made improvements to the galvanic battery (named after Galvani) in the 1810s. In Wollaston's battery, the wooden box was replaced with an earthenware vessel, and a copper plate was bent into a U-shape, with a single plate of zinc placed in the center of the bent copper. The zinc plate was prevented from making contact with the copper by dowels (pieces) of cork or wood. In his single cell design, the U-shaped copper plate was welded to a horizontal handle for lifting the copper and zinc plates out of the electrolyte when the battery was not in use.

In 1809, Samuel Thomas von Soemmering developed the first telegraph

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore is a method of telegraphy, whereas p ...

. He used a device with 26 wires (1 wire for each letter of the German alphabet) terminating in a container of acid. At the sending station, a key, which completed a circuit with a battery, was connected as required to each of the line wires. The passage of current caused the acid to decompose chemically, and the message was read by observing at which of the terminals the bubbles of gas appeared. This is how he was able to send messages, one letter at a time.

Humphry Davy

Sir Humphry Davy, 1st Baronet, (17 December 177829 May 1829) was a British chemist and inventor who invented the Davy lamp and a very early form of arc lamp. He is also remembered for isolating, by using electricity, several elements for t ...

's work with electrolysis led to conclusion that the production of electricity in simple electrolytic cells resulted from chemical reactions between the electrolyte and the metals, and occurred between substances of opposite charge. He reasoned that the interactions of electric currents with chemicals offered the most likely means of decomposing all substances to their basic elements. These views were explained in 1806 in his lecture ''On Some Chemical Agencies of Electricity'', for which he received the Napoleon Prize from the Institut de France

The (; ) is a French learned society, grouping five , including the Académie Française. It was established in 1795 at the direction of the National Convention. Located on the Quai de Conti in the 6th arrondissement of Paris, the institute m ...

in 1807 (despite the fact that England and France were at war at the time). This work led directly to the isolation of sodium and potassium from their common compounds and of the alkaline earth metals from theirs in 1808.

Hans Christian Ørsted

Hans Christian Ørsted ( , ; often rendered Oersted in English; 14 August 17779 March 1851) was a Danish physicist and chemist who discovered that electric currents create magnetic fields, which was the first connection found between electricity ...

's discovery of the magnetic effect of electric currents in 1820 was immediately recognised as an important advance, although he left further work on electromagnetism

In physics, electromagnetism is an interaction that occurs between particles with electric charge. It is the second-strongest of the four fundamental interactions, after the strong force, and it is the dominant force in the interactions of a ...

to others. André-Marie Ampère

André-Marie Ampère (, ; ; 20 January 177510 June 1836) was a French physicist and mathematician who was one of the founders of the science of classical electromagnetism, which he referred to as "electrodynamics". He is also the inventor of nu ...

quickly repeated Ørsted's experiment, and formulated them mathematically (which became Ampère's law) . Ørsted also discovered that not only is a magnetic needle deflected by the electric current, but that the live electric wire is also deflected in a magnetic field, thus laying the foundation for the construction of an electric motor. Ørsted's discovery of piperine

Piperine, along with its isomer chavicine, is the alkaloid responsible for the pungency of black pepper and long pepper. It has been used in some forms of traditional medicine.

Preparation

Due to its poor solubility in water, piperine is typica ...

, one of the pungent components of pepper, was an important contribution to chemistry, as was his preparation of aluminium

Aluminium (aluminum in American and Canadian English) is a chemical element with the symbol Al and atomic number 13. Aluminium has a density lower than those of other common metals, at approximately one third that of steel. I ...

in 1825.

During the 1820s, Robert Hare developed the Deflagrator, a form of voltaic battery having large plates used for producing rapid and powerful combustion

Combustion, or burning, is a high-temperature exothermic redox chemical reaction between a fuel (the reductant) and an oxidant, usually atmospheric oxygen, that produces oxidized, often gaseous products, in a mixture termed as smoke. Combusti ...

. A modified form of this apparatus was employed in 1823 in volatilising and fusing carbon

Carbon () is a chemical element with the symbol C and atomic number 6. It is nonmetallic and tetravalent

In chemistry, the valence (US spelling) or valency (British spelling) of an element is the measure of its combining capacity with o ...

. It was with these batteries that the first use of voltaic electricity for blasting under water was made in 1831.

In 1821, the Estonia

Estonia, formally the Republic of Estonia, is a country by the Baltic Sea in Northern Europe. It is bordered to the north by the Gulf of Finland across from Finland, to the west by the sea across from Sweden, to the south by Latvia, a ...

n-German physicist, Thomas Johann Seebeck, demonstrated the electrical potential in the juncture points of two dissimilar metals when there is a temperature difference between the joints. He joined a copper wire with a bismuth wire to form a loop or circuit. Two junctions were formed by connecting the ends of the wires to each other. He then accidentally discovered that if he heated one junction to a high temperature, and the other junction remained at room temperature, a magnetic field was observed around the circuit.

He did not recognise that an electric current was being generated when heat was applied to a bi-metal junction. He used the term "thermomagnetic currents" or "thermomagnetism" to express his discovery. Over the following two years, he reported on his continuing observations to the Prussian Academy of Sciences, where he described his observation as "the magnetic polarization of metals and ores produced by a temperature difference." This Seebeck effect became the basis of the thermocouple

A thermocouple, also known as a "thermoelectrical thermometer", is an electrical device consisting of two dissimilar electrical conductors forming an electrical junction. A thermocouple produces a temperature-dependent voltage as a result of the ...

, which is still considered the most accurate measurement of temperature today. The converse Peltier effect was seen over a decade later when a current was run through a circuit with two dissimilar metals, resulting in a temperature difference between the metals.

In 1827 German scientist Georg Ohm

Georg Simon Ohm (, ; 16 March 1789 – 6 July 1854) was a German physicist and mathematician. As a school teacher, Ohm began his research with the new electrochemical cell, invented by Italian scientist Alessandro Volta. Using equipment of his o ...

expressed his law in his famous book ''Die galvanische Kette, mathematisch bearbeitet'' (The Galvanic Circuit Investigated Mathematically) in which he gave his complete theory of electricity.

In 1829 Antoine-César Becquerel developed the "constant current" cell, forerunner of the well-known Daniell cell. When this acid-alkali cell was monitored by a galvanometer, current was found to be constant for an hour, the first instance of "constant current". He applied the results of his study of thermoelectricity to the construction of an electric thermometer, and measured the temperatures of the interior of animals, of the soil at different depths, and of the atmosphere at different heights. He helped validate Faraday's laws and conducted extensive investigations on the electroplating

Electroplating, also known as electrochemical deposition or electrodeposition, is a process for producing a metal coating on a solid substrate through the reduction of cations of that metal by means of a direct electric current. The part to be ...

of metals with applications for metal finishing and metallurgy

Metallurgy is a domain of materials science and engineering that studies the physical and chemical behavior of metallic elements, their inter-metallic compounds, and their mixtures, which are known as alloys.

Metallurgy encompasses both the sc ...

. Solar cell

A solar cell, or photovoltaic cell, is an electronic device that converts the energy of light directly into electricity by the photovoltaic effect, which is a physical and chemical phenomenon.

technology dates to 1839 when Becquerel observed that shining light on an electrode submerged in a conductive solution would create an electric current.

Michael Faraday

Michael Faraday (; 22 September 1791 – 25 August 1867) was an English scientist who contributed to the study of electromagnetism and electrochemistry. His main discoveries include the principles underlying electromagnetic inducti ...

began, in 1832, what promised to be a rather tedious attempt to prove that all electricities had precisely the same properties and caused precisely the same effects. The key effect was electrochemical decomposition. Voltaic and electromagnetic electricity posed no problems, but static electricity did. As Faraday delved deeper into the problem, he made two startling discoveries. First, electrical force did not, as had long been supposed, act at a distance upon molecules to cause them to dissociate. It was the passage of electricity through a conducting liquid medium that caused the molecules to dissociate, even when the electricity merely discharged into the air and did not pass through a "pole" or "center of action" in a voltaic cell. Second, the amount of the decomposition was found to be related directly to the amount of electricity passing through the solution.

These findings led Faraday to a new theory of electrochemistry. The electric force, he argued, threw the molecules of a solution into a state of tension. When the force was strong enough to distort the forces that held the molecules together so as to permit the interaction with neighbouring particles, the tension was relieved by the migration of particles along the lines of tension, the different parts of atoms migrating in opposite directions. The amount of electricity that passed, then, was clearly related to the chemical affinities of the substances in solution. These experiments led directly to Faraday's two laws of electrochemistry which state:

*The amount of a substance deposited on each electrode of an electrolytic cell is directly proportional to the amount of electricity passing through the cell.

*The quantities of different elements deposited by a given amount of electricity are in the ratio of their chemical equivalent weight

In chemistry, equivalent weight (also known as gram equivalent) is the mass of one equivalent, that is the mass of a given substance which will combine with or displace a fixed quantity of another substance. The equivalent weight of an element is ...

s.

William Sturgeon built an electric motor in 1832 and invented the commutator

In mathematics, the commutator gives an indication of the extent to which a certain binary operation fails to be commutative. There are different definitions used in group theory and ring theory.

Group theory

The commutator of two elements, a ...

, a ring of metal-bristled brushes which allow the spinning armature to maintain contact with the electric current and changed the alternating current

Alternating current (AC) is an electric current which periodically reverses direction and changes its magnitude continuously with time in contrast to direct current (DC) which flows only in one direction. Alternating current is the form in whic ...

to a pulsating direct current

Direct current (DC) is one-directional flow of electric charge. An electrochemical cell is a prime example of DC power. Direct current may flow through a conductor such as a wire, but can also flow through semiconductors, insulators, or even ...

. He also improved the voltaic battery and worked on the theory of thermoelectricity.

Hippolyte Pixii, a French instrument maker, constructed the first dynamo in 1832 and later built a direct current dynamo using the commutator. This was the first practical mechanical generator of electric current that used concepts demonstrated by Faraday.

John Daniell began experiments in 1835 in an attempt to improve the voltaic battery with its problems of being unsteady and a weak source of electric current. His experiments soon led to remarkable results. In 1836, he invented a primary cell in which hydrogen was eliminated in the generation of the electricity. Daniell had solved the problem of polarization. In his laboratory he had learned to alloy the

John Daniell began experiments in 1835 in an attempt to improve the voltaic battery with its problems of being unsteady and a weak source of electric current. His experiments soon led to remarkable results. In 1836, he invented a primary cell in which hydrogen was eliminated in the generation of the electricity. Daniell had solved the problem of polarization. In his laboratory he had learned to alloy the amalgam

Amalgam most commonly refers to:

* Amalgam (chemistry), mercury alloy

* Amalgam (dentistry), material of silver tooth fillings

** Bonded amalgam, used in dentistry

Amalgam may also refer to:

* Amalgam Comics, a publisher

* Amalgam Digital, an in ...

ated zinc of Sturgeon with mercury. His version was the first of the two-fluid class battery and the first battery that produced a constant reliable source of electric current over a long period of time.

William Grove produced the first fuel cell

A fuel cell is an electrochemical cell that converts the chemical energy of a fuel (often hydrogen) and an oxidizing agent (often oxygen) into electricity through a pair of redox reactions. Fuel cells are different from most batteries in requ ...

in 1839. He based his experiment on the fact that sending an electric current through water splits the water into its component parts of hydrogen and oxygen. So, Grove tried reversing the reaction—combining hydrogen and oxygen to produce electricity and water. Eventually the term ''fuel cell'' was coined in 1889 by Ludwig Mond

Ludwig Mond FRS (7 March 1839 – 11 December 1909) was a German-born, British chemist and industrialist. He discovered an important, previously unknown, class of compounds called metal carbonyls.

Education and career

Ludwig Mond was born i ...

and Charles Langer, who attempted to build the first practical device using air and industrial coal gas

Coal gas is a flammable gaseous fuel made from coal and supplied to the user via a piped distribution system. It is produced when coal is heated strongly in the absence of air. Town gas is a more general term referring to manufactured gaseous ...

. He also introduced a powerful battery at the annual meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science in 1839. Grove's first cell consisted of zinc in diluted sulfuric acid and platinum in concentrated nitric acid

Nitric acid is the inorganic compound with the formula . It is a highly corrosive mineral acid. The compound is colorless, but older samples tend to be yellow cast due to decomposition into oxides of nitrogen. Most commercially available nitri ...

, separated by a porous pot. The cell was able to generate about 12 ampere

The ampere (, ; symbol: A), often shortened to amp,SI supports only the use of symbols and deprecates the use of abbreviations for units. is the unit of electric current in the International System of Units (SI). One ampere is equal to elect ...

s of current at about 1.8 volts. This cell had nearly double the voltage of the first Daniell cell. Grove's nitric acid cell was the favourite battery of the early American telegraph (1840–1860), because it offered strong current output.

As telegraph traffic increased, it was found that the Grove cell discharged poisonous nitrogen dioxide gas. As telegraphs became more complex, the need for a constant voltage became critical and the Grove device was limited (as the cell discharged, nitric acid was depleted and voltage was reduced). By the time of the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

, Grove's battery had been replaced by the Daniell battery. In 1841 Robert Bunsen replaced the expensive platinum electrode used in Grove's battery with a carbon electrode. This led to large scale use of the "Bunsen battery" in the production of arc-lighting and in electroplating.

Wilhelm Weber developed, in 1846, the electrodynamometer

The wattmeter is an instrument for measuring the electric active power (or the average of the rate of flow of electrical energy) in watts of any given circuit. Electromagnetic wattmeters are used for measurement of utility frequency and audio ...

, in which a current causes a coil suspended within another coil to turn when a current is passed through both. In 1852, Weber defined the absolute unit of electrical resistance (which was named the ohm

Ohm (symbol Ω) is a unit of electrical resistance named after Georg Ohm.

Ohm or OHM may also refer to:

People

* Georg Ohm (1789–1854), German physicist and namesake of the term ''ohm''

* Germán Ohm (born 1936), Mexican boxer

* Jörg Ohm (b ...

after Georg Ohm). Weber's name is now used as a unit name to describe magnetic flux

In physics, specifically electromagnetism, the magnetic flux through a surface is the surface integral of the normal component of the magnetic field B over that surface. It is usually denoted or . The SI unit of magnetic flux is the weber ( ...

, the weber

Weber (, or ; German: ) is a surname of German origin, derived from the noun meaning " weaver". In some cases, following migration to English-speaking countries, it has been anglicised to the English surname 'Webber' or even 'Weaver'.

Notable pe ...

.

German physicist Johann Hittorf

Johann Wilhelm Hittorf (27 March 1824 – 28 November 1914) was a German physicist who was born in Bonn and died in Münster, Germany.

Hittorf was the first to compute the electricity-carrying capacity of charged atoms and molecules (ions), an ...

concluded that ''ion movement'' caused electric current. In 1853 Hittorf noticed that some ions traveled more rapidly than others. This observation led to the concept of transport number, the rate at which particular ions carried the electric current. Hittorf measured the changes in the concentration of electrolysed solutions, computed from these the transport numbers (relative carrying capacities) of many ions, and, in 1869, published his findings governing the migration of ions.

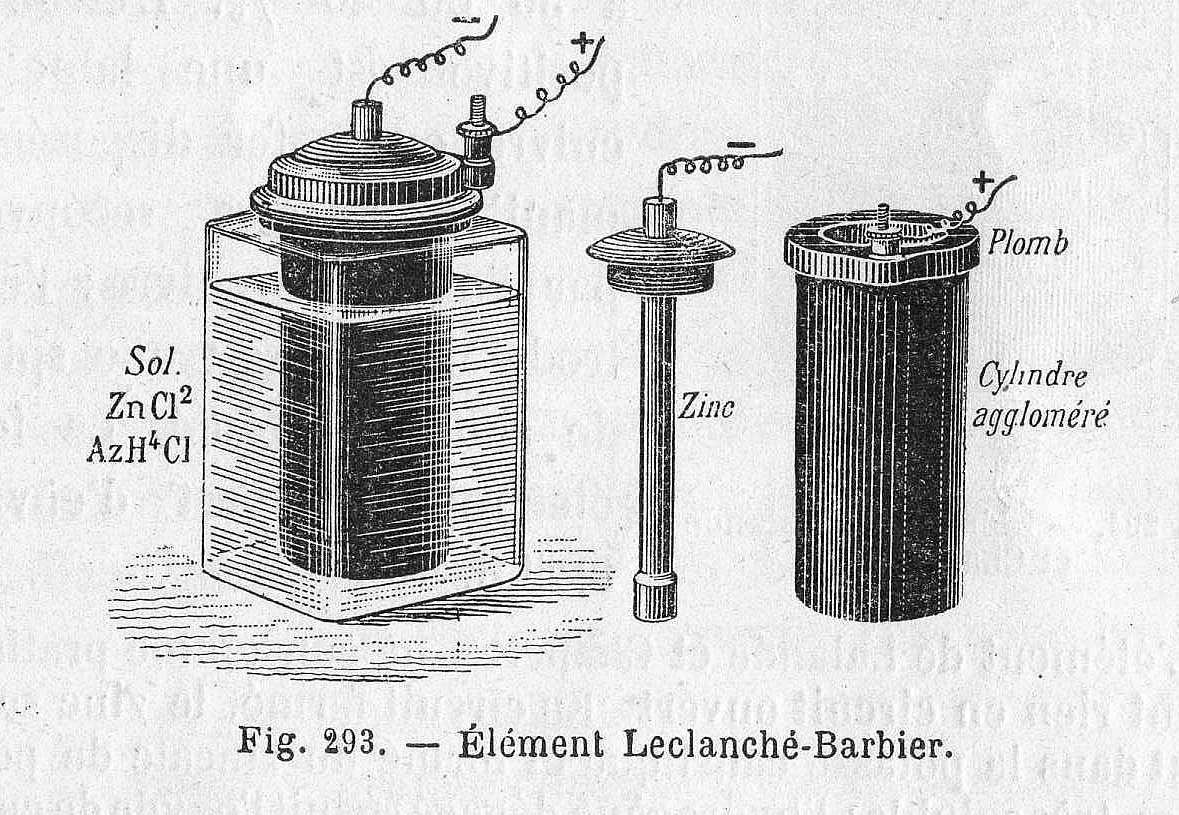

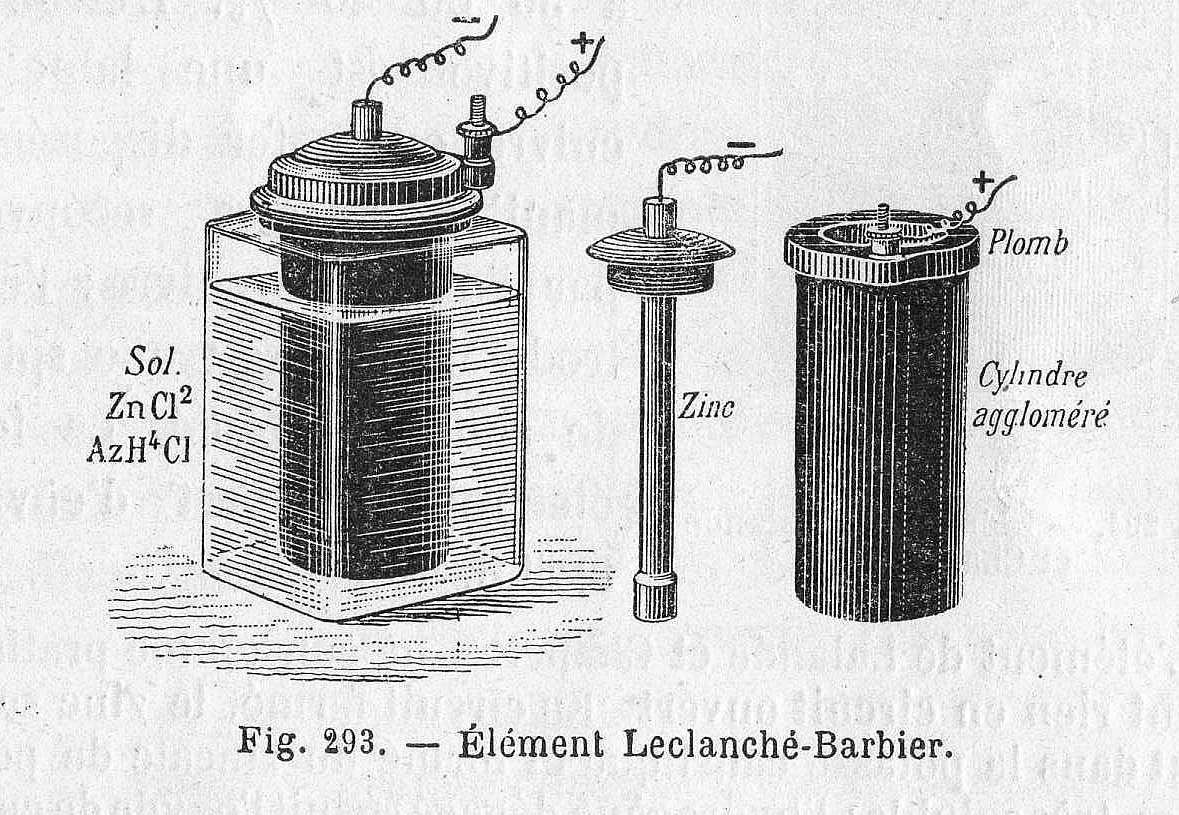

In 1866,

In 1866, Georges Leclanché

Georges Leclanché (October 9, 1839 – September 14, 1882) was a French electrical engineer chiefly remembered for his invention of the Leclanché cell, one of the first modern electrical batteries and the forerunner of the modern dry cell batter ...

patented a new battery system, which was immediately successful. Leclanché's original cell was assembled in a porous pot. The positive electrode (the cathode

A cathode is the electrode from which a conventional current leaves a polarized electrical device. This definition can be recalled by using the mnemonic ''CCD'' for ''Cathode Current Departs''. A conventional current describes the direction in whi ...

) consisted of crushed manganese dioxide with a little carbon mixed in. The negative pole (anode

An anode is an electrode of a polarized electrical device through which conventional current enters the device. This contrasts with a cathode, an electrode of the device through which conventional current leaves the device. A common mnemonic is ...

) was a zinc rod. The cathode was packed into the pot, and a carbon rod was inserted to act as a current collector. The anode and the pot were then immersed in an ammonium chloride solution. The liquid acted as the electrolyte, readily seeping through the porous pot and making contact with the cathode material. Leclanché's "wet" cell became the forerunner to the world's first widely used battery, the zinc-carbon cell.

Late 19th century advances and the advent of electrochemical societies

In 1869 Zénobe Gramme devised his first clean direct current dynamo. His generator featured a ring armature wound with many individual coils of wire.Svante August Arrhenius

Svante August Arrhenius ( , ; 19 February 1859 – 2 October 1927) was a Swedish scientist. Originally a physicist, but often referred to as a chemist, Arrhenius was one of the founders of the science of physical chemistry. He received the Nobe ...

published his thesis in 1884, ''Recherches sur la conductibilité galvanique des électrolytes'' (Investigations on the galvanic conductivity of electrolytes). From the results of his experiments, the author concluded that electrolytes, when dissolved in water, become to varying degrees split or dissociated into positive and negative ions. The degree to which this dissociation occurred depended above all on the nature of the substance and its concentration in the solution, being more developed the greater the dilution. The ions were supposed to be the carriers of not only the electric current, as in electrolysis, but also of the chemical activity. The relation between the actual number of ions and their number at great dilution (when all the molecules were dissociated) gave a quantity of special interest ("activity constant").

The race for the commercially viable production of

The race for the commercially viable production of aluminium

Aluminium (aluminum in American and Canadian English) is a chemical element with the symbol Al and atomic number 13. Aluminium has a density lower than those of other common metals, at approximately one third that of steel. I ...

was won in 1886 by Paul Héroult and Charles M. Hall

Charles Martin Hall (December 6, 1863 – December 27, 1914) was an American inventor, businessman, and chemist. He is best known for his invention in 1886 of an inexpensive method for producing aluminum, which became the first metal to att ...

. The problem many researchers had with extracting aluminium was that electrolysis of an aluminium salt dissolved in water yields aluminium hydroxide

Aluminium hydroxide, Al(OH)3, is found in nature as the mineral gibbsite (also known as hydrargillite) and its three much rarer polymorphs: bayerite, doyleite, and nordstrandite. Aluminium hydroxide is amphoteric, i.e., it has both basic and ...

. Both Hall and Héroult avoided this problem by dissolving aluminium oxide in a new solvent— fused cryolite ( Na3Al F6).

Wilhelm Ostwald, 1909 Nobel Laureate

The Nobel Prizes ( sv, Nobelpriset, no, Nobelprisen) are awarded annually by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, the Swedish Academy, the Karolinska Institutet, and the Norwegian Nobel Committee to individuals and organizations who make out ...

, started his experimental work in 1875, with an investigation on the law of mass action of water in relation to the problems of chemical affinity, with special emphasis on electrochemistry and chemical dynamics

Chemical kinetics, also known as reaction kinetics, is the branch of physical chemistry that is concerned with understanding the rates of chemical reactions. It is to be contrasted with chemical thermodynamics, which deals with the direction in wh ...

. In 1894 he gave the first modern definition of a catalyst

Catalysis () is the process of increasing the rate of a chemical reaction by adding a substance known as a catalyst (). Catalysts are not consumed in the reaction and remain unchanged after it. If the reaction is rapid and the catalyst recyc ...

and turned his attention to catalytic reactions. Ostwald is especially known for his contributions to the field of electrochemistry, including important studies of the electrical conductivity and electrolytic dissociation of organic acids.

Hermann Nernst developed the theory of the electromotive force of the voltaic cell in 1888. He developed methods for measuring dielectric constant

The relative permittivity (in older texts, dielectric constant) is the permittivity of a material expressed as a ratio with the electric permittivity of a vacuum. A dielectric is an insulating material, and the dielectric constant of an insulat ...

s and was the first to show that solvents of high dielectric constants promote the ionization of substances. Nernst's early studies in electrochemistry were inspired by Arrhenius' dissociation theory which first recognised the importance of ions in solution. In 1889, Nernst elucidated the theory of galvanic cells by assuming an "electrolytic pressure of dissolution," which forces ions from electrodes into solution and which was opposed to the osmotic pressure of the dissolved ions. He applied the principles of thermodynamics to the chemical reactions proceeding in a battery. In that same year he showed how the characteristics of the current produced could be used to calculate the free energy change in the chemical reaction producing the current. He constructed an equation, known as Nernst Equation, which describes the relation of a battery cell's voltage to its properties.

In 1898 Fritz Haber published his textbook, ''Electrochemistry: Grundriss der technischen Elektrochemie auf theoretischer Grundlage'' (The Theoretical Basis of Technical Electrochemistry), which was based on the lectures he gave at Karlsruhe

Karlsruhe ( , , ; South Franconian: ''Kallsruh'') is the third-largest city of the German state (''Land'') of Baden-Württemberg after its capital of Stuttgart and Mannheim, and the 22nd-largest city in the nation, with 308,436 inhabitants. ...

. In the preface to his book he expressed his intention to relate chemical research to industrial processes and in the same year he reported the results of his work on electrolytic oxidation and reduction, in which he showed that definite reduction products can result if the voltage at the cathode is kept constant. In 1898 he explained the reduction of nitrobenzene

Nitrobenzene is an organic compound with the chemical formula C6H5 NO2. It is a water-insoluble pale yellow oil with an almond-like odor. It freezes to give greenish-yellow crystals. It is produced on a large scale from benzene as a precursor t ...

in stages at the cathode and this became the model for other similar reduction processes.

In 1909, Robert Andrews Millikan

Robert Andrews Millikan (March 22, 1868 – December 19, 1953) was an American experimental physicist honored with the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1923 for the measurement of the elementary electric charge and for his work on the photoelectric e ...

began a series of experiments to determine the electric charge carried by a single electron. He began by measuring the course of charged water droplets in an electrical field. The results suggested that the charge on the droplets is a multiple of the elementary electric charge, but the experiment was not accurate enough to be convincing. He obtained more precise results in 1910 with his famous oil-drop experiment

The oil drop experiment was performed by Robert A. Millikan and Harvey Fletcher in 1909 to measure the elementary electric charge (the charge of the electron). The experiment took place in the Ryerson Physical Laboratory at the University of Chi ...

in which he replaced water (which tended to evaporate too quickly) with oil.

Jaroslav Heyrovský, a Nobel laureate, eliminated the tedious weighing required by previous analytical techniques, which used the differential precipitation of mercury by measuring drop-time. In the previous method, a voltage was applied to a dropping mercury electrode and a reference electrode was immersed in a test solution. After 50 drops of mercury were collected, they were dried and weighed. The applied voltage was varied and the experiment repeated. Measured weight was plotted versus applied voltage to obtain the curve. In 1921, Heyrovský had the idea of measuring the current flowing through the cell instead of just studying drop-time.

On February 10, 1922, the "

On February 10, 1922, the "polarograph

A Polarograph is a chemical analysis instrument used to record automatic voltage-intensity curves.

The Polarograph uses an electrolytic cell consisting of an electrode or microelectrode small area, generally of mercury drop type, which is a very f ...

" was born as Heyrovský recorded the current-voltage curve for a solution of 1 mol/L NaOH. Heyrovský correctly interpreted the current increase between −1.9 and −2.0 V as being due to the deposit of Na+ ions, forming an amalgam. Shortly thereafter, with his Japanese colleague Masuzo Shikata was a Japanese chemist and one of the pioneers in electrochemistry. Together with his mentor and colleague, Czech chemist and inventor Jaroslav Heyrovský, he developed the first polarograph, a type of electrochemical analyzing machine, and co-a ...

, he constructed the first instrument for the automatic recording of polarographic curves, which became world-famous later as the polarograph.

In 1923, Johannes Nicolaus Brønsted

Johannes Nicolaus Brønsted (; 22 February 1879 – 17 December 1947) was a Danish physical chemist, who developed the Brønsted–Lowry acid–base theory simultaneously with and independently of Martin Lowry.

Biography

Brønsted was born in ...

and Thomas Martin Lowry

Thomas Martin Lowry (; 26 October 1874 – 2 November 1936) was an English physical chemist who developed the Brønsted–Lowry acid–base theory simultaneously with and independently of Johannes Nicolaus Brønsted and was a founder-member an ...

published essentially the same theory about how acids and bases behave using electrochemical basis.

The International Society of Electrochemistry (ISE) was founded in 1949, and some years later the first sophisticated electrophoretic

Electrophoresis, from Ancient Greek ἤλεκτρον (ḗlektron, "amber") and φόρησις (phórēsis, "the act of bearing"), is the motion of dispersed particles relative to a fluid under the influence of a spatially uniform electric fie ...

apparatus was developed in 1937 by Arne Tiselius

Arne Wilhelm Kaurin Tiselius (10 August 1902 – 29 October 1971) was a Swedish biochemist who won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1948 "for his research on electrophoresis and adsorption analysis, especially for his discoveries concerning t ...

, who was awarded the 1948 Nobel prize for his work in protein electrophoresis

Electrophoresis, from Ancient Greek ἤλεκτρον (ḗlektron, "amber") and φόρησις (phórēsis, "the act of bearing"), is the motion of dispersed particles relative to a fluid under the influence of a spatially uniform electric fie ...

. He developed the "moving boundary," which later would become known as ''zone electrophoresis'', and used it to separate serum proteins in solution. Electrophoresis became widely developed in the 1940s and 1950s when the technique was applied to molecules ranging from the largest proteins to amino acids and even inorganic ions.

During the 1960s and 1970s quantum electrochemistry

The scientific school of Quantum electrochemistry began to form in the 1960s under Revaz Dogonadze. Generally speaking, the field comprises the notions arising in electrodynamics, quantum mechanics, and electrochemistry; and so is studied by a very ...

was developed by Revaz Dogonadze Revaz Dogonadze (November 21, 1931 – May 13, 1985) was a notable Georgian scientist, Corresponding Member of the Georgian National Academy of Sciences (GNAS) (1982), Doctor of Physical & Mathematical Sciences (Full Doctor) (1966), Professor (1972) ...

and his pupils.

See also

*Electrochemistry

Electrochemistry is the branch of physical chemistry concerned with the relationship between electrical potential difference, as a measurable and quantitative phenomenon, and identifiable chemical change, with the potential difference as an outco ...

* History of the battery

Batteries provided the primary source of electricity before the development of electric generators and electrical grids around the end of the 19th century. Successive improvements in battery technology facilitated major electrical advances, ...

*

References

*{{cite web, title=Physician-described use of electricity in medicine, work=T.Gale's Electricity, or Ethereal Fire, Considered, 1802, url=http://www.iment.com/maida/familytree/henry/theman/atlocustgrove/medical/electricity/tableofcontents.htm, accessdate=March 10, 2008Corrosion-Doctors.org

*A classic and knowledgeable—but dated—reference on the history of electrochemistry is by 1909 Nobelist in Chemistry, Wilhelm Ostwald: Elektrochemie: Ihre Geschichte und Lehre, Wilhelm Ostwald, Veit, Leipzig, 1896. (https://archive.org/details/elektrochemieih00ostwgoog). An English version is available as "Electrochemistry: history and theory" (2 volumes), translated by N. P. Date. It was published for the Smithsonian Institution and the National Science Foundation, Washington, DC, by Amerind Publ. Co., New Delhi, 1980. History of chemistry Electrochemistry Electrolysis

Electrochemistry

Electrochemistry is the branch of physical chemistry concerned with the relationship between electrical potential difference, as a measurable and quantitative phenomenon, and identifiable chemical change, with the potential difference as an outco ...