History of catecholamine research on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The

The

In the early 1890s, in the laboratory of

In the early 1890s, in the laboratory of

was desirous of discussing with me the results which he had been obtaining from the exhibition by the mouth of extracts from certain animal tissues, and the effects which these had in his hands produced upon the blood vessels of man.” Systemic effects of orally given adrenaline are highly unlikely, so details of the canonical text may be legend.

On March 10, 1894, Oliver and Schafer presented their findings to the

On March 10, 1894, Oliver and Schafer presented their findings to the

Elliott 1904 xx.jpg

Elliott 1904 xxi.jpg

The breakthrough for chemical neurotransmission came when, in 1921,

The next step led to the central nervous system. It was taken by

The next step led to the central nervous system. It was taken by

own naked eye: Instead of the pink color given by the comparatively high concentrations of dopamine in the control samples, the reaction vials containing the extracts of the Parkinson's disease striatum showed hardly a tinge of pink discoloration″.

In 1970, von Euler and Axelrod were two of three winners of the ''Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine'', “for their discoveries concerning the humoral transmitters in the nerve terminals and the mechanism for their storage, release and inactivation”, and in 2000 Carlsson was one of three winners who got the prize “for their discoveries concerning signal transduction in the nervous system”.

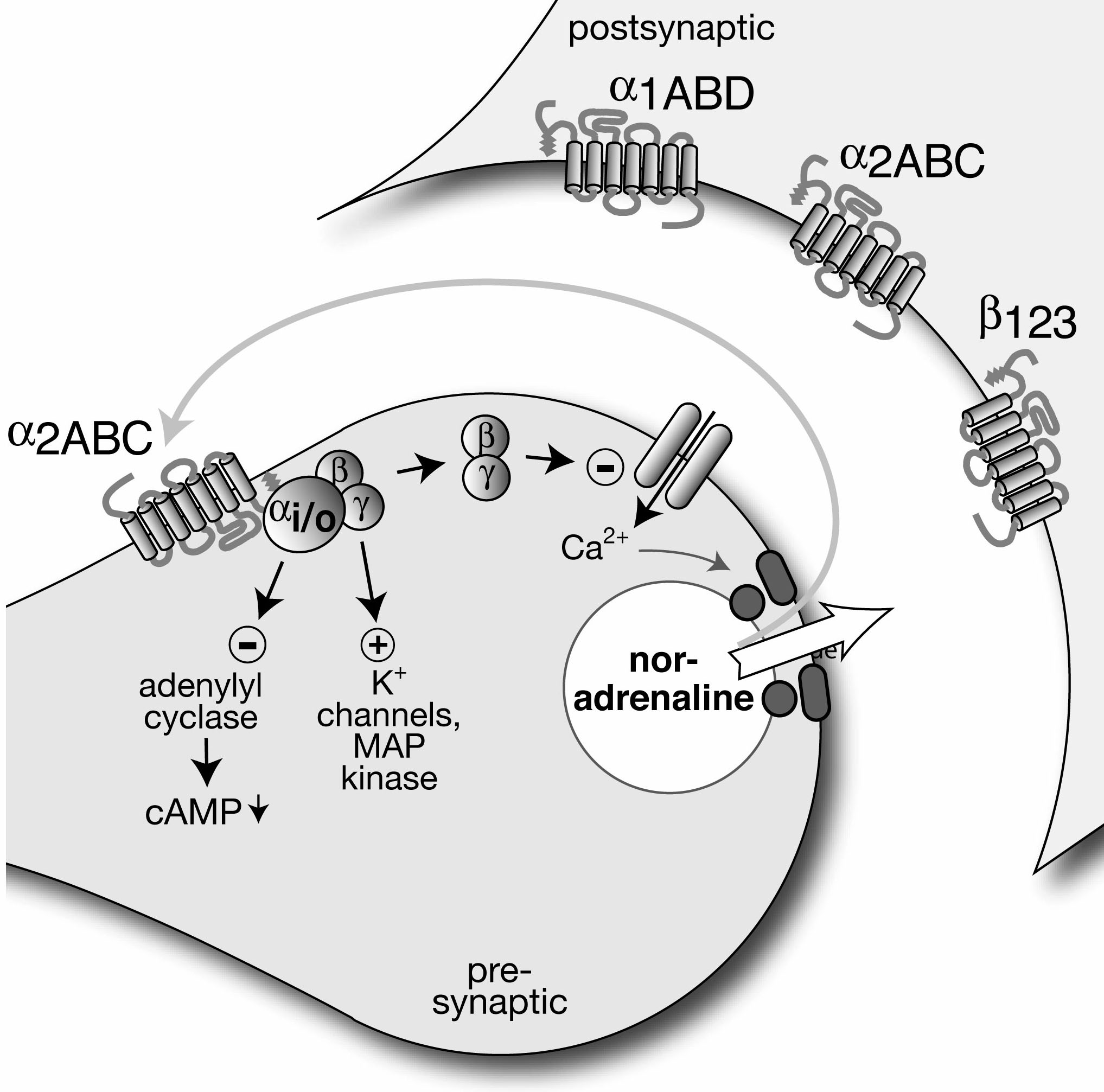

Research on the catecholamines was interwoven with research on their receptors. In 1904, Dale became head of the Wellcome Physiological Research Laboratory in London and started research on

Research on the catecholamines was interwoven with research on their receptors. In 1904, Dale became head of the Wellcome Physiological Research Laboratory in London and started research on

The

The catecholamine

A catecholamine (; abbreviated CA) is a monoamine neurotransmitter, an organic compound that has a catechol (benzene with two hydroxyl side groups next to each other) and a side-chain amine.

Catechol can be either a free molecule or a subst ...

s comprise the endogenous substances dopamine

Dopamine (DA, a contraction of 3,4-dihydroxyphenethylamine) is a neuromodulatory molecule that plays several important roles in cells. It is an organic compound, organic chemical of the catecholamine and phenethylamine families. Dopamine const ...

, noradrenaline

Norepinephrine (NE), also called noradrenaline (NA) or noradrenalin, is an organic chemical in the catecholamine family that functions in the brain and body as both a hormone and neurotransmitter. The name "noradrenaline" (from Latin '' ad'', ...

(norepinephrine), and adrenaline

Adrenaline, also known as epinephrine, is a hormone and medication which is involved in regulating visceral functions (e.g., respiration). It appears as a white microcrystalline granule. Adrenaline is normally produced by the adrenal glands and ...

(epinephrine), as well as numerous artificially synthesized compounds such as isoprenaline

Isoprenaline, or isoproterenol (brand name: Isoprenaline Macure), is a medication used for the treatment of bradycardia (slow heart rate), heart block, and rarely for asthma. It is a non-selective β adrenoceptor agonist that is the isopropylam ...

, an anti-bradycardiac medication. Their investigation comprises a major chapter in the history of physiology

Physiology (; ) is the scientific study of functions and mechanisms in a living system. As a sub-discipline of biology, physiology focuses on how organisms, organ systems, individual organs, cells, and biomolecules carry out the chemical ...

, biochemistry

Biochemistry or biological chemistry is the study of chemical processes within and relating to living organisms. A sub-discipline of both chemistry and biology, biochemistry may be divided into three fields: structural biology, enzymology and ...

, and pharmacology

Pharmacology is a branch of medicine, biology and pharmaceutical sciences concerned with drug or medication action, where a drug may be defined as any artificial, natural, or endogenous (from within the body) molecule which exerts a biochemica ...

. Adrenaline was the first hormone

A hormone (from the Greek participle , "setting in motion") is a class of signaling molecules in multicellular organisms that are sent to distant organs by complex biological processes to regulate physiology and behavior. Hormones are required ...

extracted from an endocrine gland

Endocrine glands are ductless glands of the endocrine system that secrete their products, hormones, directly into the blood. The major glands of the endocrine system include the pineal gland, pituitary gland, pancreas, ovaries, testes, thyroid ...

and obtained in pure form, before the word ''hormone'' was coined. Adrenaline was also the first hormone whose structure and biosynthesis were discovered. Second to acetylcholine

Acetylcholine (ACh) is an organic chemical that functions in the brain and body of many types of animals (including humans) as a neurotransmitter. Its name is derived from its chemical structure: it is an ester of acetic acid and choline. Part ...

, adrenaline and noradrenaline were some of the first neurotransmitter

A neurotransmitter is a signaling molecule secreted by a neuron to affect another cell across a synapse. The cell receiving the signal, any main body part or target cell, may be another neuron, but could also be a gland or muscle cell.

Neuro ...

s discovered, and the first intercellular biochemical signals to be found in intracellular

This glossary of biology terms is a list of definitions of fundamental terms and concepts used in biology, the study of life and of living organisms. It is intended as introductory material for novices; for more specific and technical definitions ...

vesicles

Vesicle may refer to:

; In cellular biology or chemistry

* Vesicle (biology and chemistry), a supramolecular assembly of lipid molecules, like a cell membrane

* Synaptic vesicle

; In human embryology

* Vesicle (embryology), bulge-like features o ...

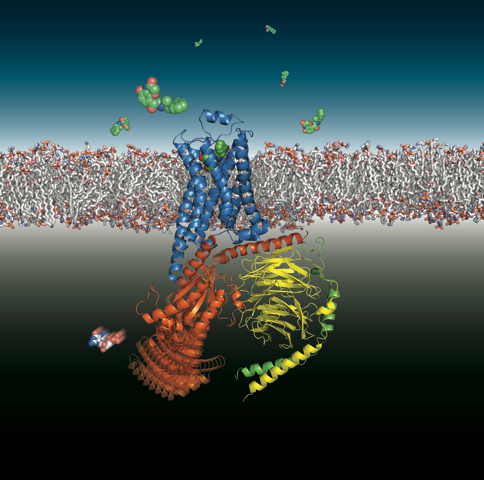

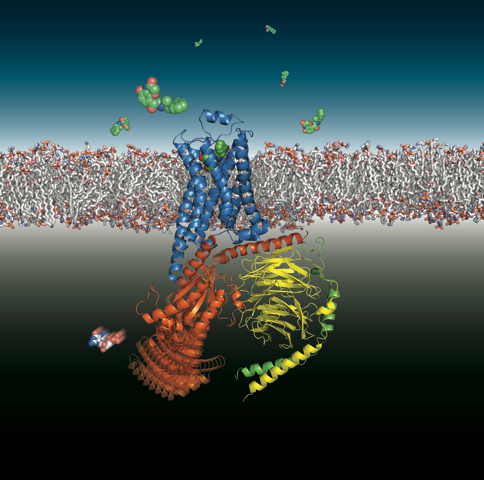

. The β-adrenoceptor was the first G protein-coupled receptor

G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), also known as seven-(pass)-transmembrane domain receptors, 7TM receptors, heptahelical receptors, serpentine receptors, and G protein-linked receptors (GPLR), form a large group of evolutionarily-related p ...

whose gene was cloned

Cloning is the process of producing individual organisms with identical or virtually identical DNA, either by natural or artificial means. In nature, some organisms produce clones through asexual reproduction. In the field of biotechnology, c ...

.

Adrenaline in the adrenal medulla

Forerunners

British physician and physiologist Henry Hyde Salter (1823–1871) included a chapter on treatment ″by stimulants" in a book onasthma

Asthma is a long-term inflammatory disease of the airways of the lungs. It is characterized by variable and recurring symptoms, reversible airflow obstruction, and easily triggered bronchospasms. Symptoms include episodes of wheezing, cou ...

first published in 1860. He noted the benefits of strong coffee, presumably because it dispelled sleep, which favored asthma. Even more impressive to him, however, was the response to ″strong mental emotion″: ″The cure of asthma by violent emotion is more sudden and complete than by any other remedy whatever; indeed, I know few things more striking and curious in the whole history of therapeutics. (..) The cure (..) takes no time; it is instantaneous, the intersect paroxysm ceases on the instant.″ The retrospective interpretation is that the ″cure″ was due to release of adrenaline from the adrenals.

At this same time, the French physician Alfred Vulpian

Edmé Félix Alfred Vulpian (5 January 1826 – 18 May 1887) was a French physician and neurologist. He was the co-discoverer of Vulpian-Bernhardt spinal muscular atrophy and the Vulpian-Heidenhain-Sherrington phenomenon.

Vulpian was born in Par ...

also made discoveries about the adrenal medulla. Material scraped from the adrenal medulla became green when ferric chloride

Iron(III) chloride is the inorganic compound with the formula . Also called ferric chloride, it is a common compound of iron in the +3 oxidation state. The anhydrous compound is a crystalline solid with a melting point of 307.6 °C. The colo ...

was added. This did not occur with the adrenal cortex nor with any other tissue. Vulpian even came to the insight that the substance entered "''le torrent circulator''" ("the circulatory torrent"), for blood from the adrenal veins did give the ferric chloride reaction.

In the early 1890s, in the laboratory of

In the early 1890s, in the laboratory of Oswald Schmiedeberg

Johann Ernst Oswald Schmiedeberg (10 October 1838 – 12 July 1921) was a Baltic German pharmacologist. In 1866 he earned his medical doctorate from the University of Dorpat with a thesis concerning the measurement of chloroform in blood, before ...

in Strasbourg

Strasbourg (, , ; german: Straßburg ; gsw, label=Bas Rhin Alsatian, Strossburi , gsw, label=Haut Rhin Alsatian, Strossburig ) is the prefecture and largest city of the Grand Est region of eastern France and the official seat of the Eu ...

, the German pharmacologist Carl Jacob (1857–1944) studied the relationship between the adrenals and the intestine. Electrical stimulation of the vagus nerve

The vagus nerve, also known as the tenth cranial nerve, cranial nerve X, or simply CN X, is a cranial nerve that interfaces with the parasympathetic control of the heart, lungs, and digestive tract. It comprises two nerves—the left and right ...

or injection of muscarine

Muscarine, L-(+)-muscarine, or muscarin is a natural product found in certain mushrooms, particularly in ''Inocybe'' and ''Clitocybe'' species, such as the deadly '' C. dealbata''. Mushrooms in the genera ''Entoloma'' and ''Mycena'' have al ...

elicited peristalsis

Peristalsis ( , ) is a radially symmetrical contraction and relaxation of muscles that propagate in a wave down a tube, in an anterograde direction. Peristalsis is progression of coordinated contraction of involuntary circular muscles, which ...

. This peristalsis was promptly abolished by electrical stimulation of the adrenals. The experiment has been called "the first indirect demonstration of the role of the adrenal medulla as an endocrine organ ndactually a more sophisticated demonstration of the adrenal medullary function than the classic study of Oliver and Schafer". While this may be true, Jacob did not envisage a chemical signal secreted into the blood to influence distant organs, the actual function of a hormone, but nerves running from the adrenals to the gut, "Hemmungsbahnen für die Darmbewegung".

Oliver and Schäfer 1893/94

George Oliver was a physician practicing in thespa town

A spa town is a resort town based on a mineral spa (a developed mineral spring). Patrons visit spas to "take the waters" for their purported health benefits.

Thomas Guidott set up a medical practice in the English town of Bath in 1668. H ...

of Harrogate

Harrogate ( ) is a spa town and the administrative centre of the Borough of Harrogate in North Yorkshire, England. Historic counties of England, Historically in the West Riding of Yorkshire, the town is a tourist destination and its visitor at ...

in North Yorkshire

North Yorkshire is the largest ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county (lieutenancy area) in England, covering an area of . Around 40% of the county is covered by National parks of the United Kingdom, national parks, including most of ...

. Edward Albert Schäfer was Professor of Physiology at University College London

, mottoeng = Let all come who by merit deserve the most reward

, established =

, type = Public research university

, endowment = £143 million (2020)

, budget = ...

. In 1918, he prefixed the surname of his physiology teacher William Sharpey

William Sharpey FRS FRSE LLD (1 April 1802 – 11 April 1880) was a Scottish anatomist and physiologist. Sharpey became the outstanding exponent of experimental biology and is described as the "father of British physiology".

Early life

Sharpe ...

to his own to become Edward Albert Sharpey Schafer. The canonical story, told by Henry Hallett Dale

Sir Henry Hallett Dale (9 June 1875 – 23 July 1968) was an English pharmacologist and physiologist. For his study of acetylcholine as agent in the chemical transmission of nerve pulses (neurotransmission) he shared the 1936 Nobel Prize in Ph ...

, who worked at University College London from 1902 to 1904, runs as follows:

Dr Oliver, I was told, … had a liking and a ′flair′ for the invention of simple appliances, with which observations and experiments could be made on the human subject. Dr Oliver had invented a small instrument with which he claimed to be able to measure, through the unbroken skin, the diameter of a living artery, such as theDespite this tale being reiterated many times, it is not beyond doubt. Dale himself said that it was handed down in University College, and showed some surprise that the constriction of the radial artery was measurable. Of Oliver's descendants, none recalled experiments on his son. Dale's report of subcutaneous injections contradicts the concerned parties. Oliver: “During the winter of 1893–4, while prosecuting an inquiry as to … agents that vary the caliber of … arteries … I found that the administration by the mouth of a glycerin extract of the adrenals of the sheep and calf produced a marked constrictive action on the arteries.” Schafer: “In the autumn of 1893 there called upon me in my laboratory in University College a gentleman who was personally unknown to me. … I found that my visitor was Dr. George Oliver,radial artery In human anatomy, the radial artery is the main artery of the lateral aspect of the forearm. Structure The radial artery arises from the bifurcation of the brachial artery in the antecubital fossa. It runs distally on the anterior part of the f ...at the wrist. He appears to have used his family in his experiments, and a young son was the subject of a series, in which Dr Oliver measured the diameter of the radial artery, and observed the effect upon it of injecting extracts of various animal glands under the skin. … We may picture, then, Professor Schafer, in the old physiological laboratory at University College, … finishing an experiment of some kind, in which he was recording the arterialblood pressure Blood pressure (BP) is the pressure of circulating blood against the walls of blood vessels. Most of this pressure results from the heart pumping blood through the circulatory system. When used without qualification, the term "blood pressure" r ...of an anaesthetized dog. … To him enters Dr Oliver, with the story of the experiments on his boy, and, in particular, with the statement that injection under the skin of a glycerin extract from calf’s suprarenal gland was followed by a definite narrowing of the radial artery. Professor Schafer is said to have been entirely skeptical, and to have attributed the observation to self-delusion. … He can hardly be blamed, I think; knowing even what we now know about the action of this extract, which of us would be prepared to believe that injecting it under a boy’s skin would cause his radial artery to become measurably more slender? Dr Oliver, however, is persistent; he … suggests that, at least, it will do no harm to inject into the circulation, through a vein, a little of the suprarenal extract, which he produces from his pocket. So Professor Schafer makes the injection, expecting a triumphant demonstration of nothing, and finds himself standing ′like some watcher of the skies, when a new planet swims into his ken,′ watching the mercury rise in the manometer with amazing rapidity and to an astounding height.

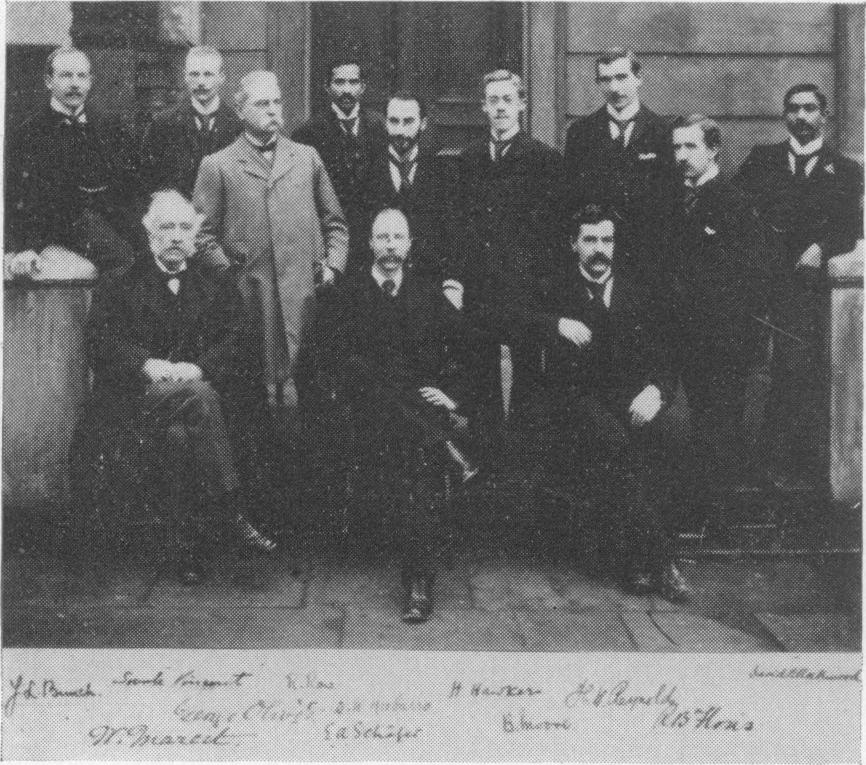

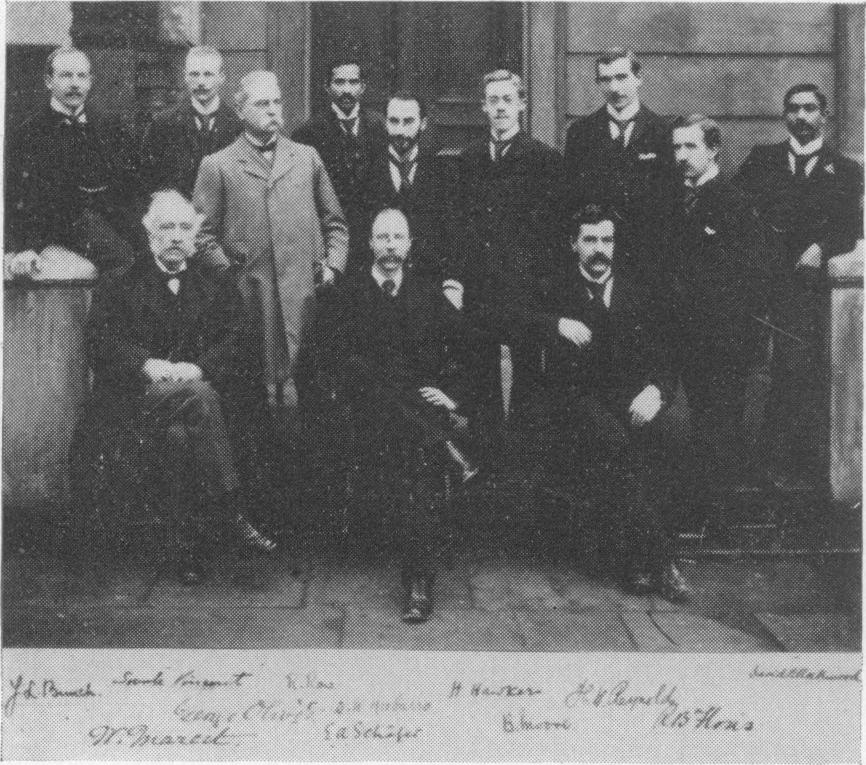

On March 10, 1894, Oliver and Schafer presented their findings to the

On March 10, 1894, Oliver and Schafer presented their findings to the Physiological Society

The Physiological Society, founded in 1876, is a learned society for physiologists in the United Kingdom.

History

The Physiological Society was founded in 1876 as a dining society "for mutual benefit and protection" by a group of 19 physiologist ...

in London. A 47-page account followed a year later, in the style of the time without statistics, but with precise description of many individual experiments and 25 recordings on kymograph

A kymograph (from Greek κῦμα, swell or wave + γραφή, writing; also called a kymographion) is an analog device that draws a graphical representation of spatial position over time in which a spatial axis represents time. It basically consi ...

smoked drums, showing, besides the blood pressure increase, reflex bradycardia

Reflex bradycardia is a bradycardia (decrease in heart rate) in response to the baroreceptor reflex, one of the body's homeostatic mechanisms for preventing abnormal increases in blood pressure. In the presence of high mean arterial pressure, the ...

and contraction of the spleen

The spleen is an organ found in almost all vertebrates. Similar in structure to a large lymph node, it acts primarily as a blood filter. The word spleen comes .

. ″It appears to be established as the result of these investigations that the suprarenal capsules are to be regarded although ductless, as strictly secreting glands. The material which they form and which is found, at least in its fully active condition, only in the medulla of the gland, produces striking physiological effects upon the muscular tissue generally, and especially upon that of the heart and arteries. Its action is produced mainly if not entirely by direct action.″

The reports created a sensation. Oliver was fast to try adrenal extracts in patients, orally again and rather indiscriminately, from Addison's disease

Addison's disease, also known as primary adrenal insufficiency, is a rare long-term endocrine disorder characterized by inadequate production of the steroid hormones cortisol and aldosterone by the two outer layers of the cells of the adrenal ...

, hypotension

Hypotension is low blood pressure. Blood pressure is the force of blood pushing against the walls of the arteries as the heart pumps out blood. Blood pressure is indicated by two numbers, the systolic blood pressure (the top number) and the dias ...

(″loss of vasomotor tone″), Diabetes mellitus

Diabetes, also known as diabetes mellitus, is a group of metabolic disorders characterized by a high blood sugar level ( hyperglycemia) over a prolonged period of time. Symptoms often include frequent urination, increased thirst and increased ap ...

and Diabetes insipidus

Diabetes insipidus (DI), recently renamed to Arginine Vasopressin Deficiency (AVP-D) and Arginine Vasopressin Resistance (AVP-R), is a condition characterized by large amounts of dilute urine and increased thirst. The amount of urine produce ...

to Graves' disease

Graves' disease (german: Morbus Basedow), also known as toxic diffuse goiter, is an autoimmune disease that affects the thyroid. It frequently results in and is the most common cause of hyperthyroidism. It also often results in an enlarged thyr ...

(″exophthalmic goiter″). It seems he adhered to contemporary ideas of organotherapy, believing that powerful substances existed in tissues and ought to be discovered for medicinal use. He immediately went on to extract the pituitary gland

In vertebrate anatomy, the pituitary gland, or hypophysis, is an endocrine gland, about the size of a chickpea and weighing, on average, in humans. It is a protrusion off the bottom of the hypothalamus at the base of the brain. The ...

and, again with Schafer, discovered vasopressin

Human vasopressin, also called antidiuretic hormone (ADH), arginine vasopressin (AVP) or argipressin, is a hormone synthesized from the AVP gene as a peptide prohormone in neurons in the hypothalamus, and is converted to AVP. It then travel ...

. In 1903 adrenaline, meanwhile purified, was first used in asthma. The use was based, not on the bronchodilator

A bronchodilator or broncholytic (although the latter occasionally includes secretory inhibition as well) is a substance that dilates the bronchi and bronchioles, decreasing resistance in the respiratory airway and increasing airflow to the lun ...

effect, which was discovered later, but on the vasoconstrictor

Vasoconstriction is the narrowing of the blood vessels resulting from contraction of the muscular wall of the vessels, in particular the large arteries and small arterioles. The process is the opposite of vasodilation, the widening of blood vessel ...

effect, which was hoped to alleviate the “turgidity of the bronchial mucosa” – presumably vascular congestion and edema. Also as of 1903, adrenaline was added to local anesthetic

A local anesthetic (LA) is a medication that causes absence of pain sensation. In the context of surgery, a local anesthetic creates an absence of pain in a specific location of the body without a loss of consciousness, as opposed to a general an ...

solutions. The surgeon Heinrich Braun

Heinrich Friedrich Wilhelm Braun (1 January 1862 – 26 April 1934) was a German surgeon remembered for his work in the field of anaesthesiology. He was a native of Rawitsch, Province of Posen (today called Rawicz, Poland).

Braun attended the K ...

in Leipzig

Leipzig ( , ; Upper Saxon: ) is the most populous city in the German state of Saxony. Leipzig's population of 605,407 inhabitants (1.1 million in the larger urban zone) as of 2021 places the city as Germany's eighth most populous, as wel ...

showed that it prolonged the anesthesia at the injection site and simultaneously reduced ″systemic″ effects elsewhere in the body.

Independent discoverers

A year after Oliver and Schafer, Władysław Szymonowicz (1869–1939) andNapoleon Cybulski

Napoleon Nikodem Cybulski (Polish pronunciation: ; 14 September 1854 – 26 April 1919) was a Polish physiologist and a pioneer of endocrinology and electroencephalography. In 1895, he isolated and identified adrenaline.

Life

Napoleon Cybulski wa ...

of the Jagiellonian University

The Jagiellonian University (Polish: ''Uniwersytet Jagielloński'', UJ) is a public research university in Kraków, Poland. Founded in 1364 by King Casimir III the Great, it is the oldest university in Poland and the 13th oldest university in ...

in Kraków

Kraków (), or Cracow, is the second-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula River in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, the city dates back to the seventh century. Kraków was the official capital of Poland until 1596 ...

reported essentially similar findings and conclusions. In one aspect, they went beyond the work in England. They found that blood from the adrenal veins caused hypertension when injected intravenously in a recipient dog, whereas blood from other veins did not, showing that the adrenal pressor substance was in fact secreted into the blood and confirming Vulpian. The Polish authors freely acknowledged the priority of Oliver and Schäfer, and the British authors acknowledged the independence of Szymonowicz and Cybulski. The main difference was in the location of the action: to the periphery by Oliver and Schäfer but, erroneously, to the central nervous system by Szymonowicz and Cybulski.

Another year later, the US-American ophthalmologist William Bates, perhaps motivated like Oliver, instilled adrenal extracts into the eye and found that ″the conjunctiva of the globe and lids whitened in a few minutes″, correctly explained the effect by vasoconstriction, and administered the extracts in various eye diseases.

Chemistry

In 1897,John Jacob Abel

John Jacob Abel (19 May 1857 – 26 May 1938) was an American biochemist and pharmacologist. He established the pharmacology department at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in 1893, and then became America's first full-time professor o ...

in Baltimore

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the List of municipalities in Maryland, most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, and List of United States cities by popula ...

partially purified adrenal extracts to what he called “epinephrin”, and Otto von Fürth in Strasbourg to what he called “Suprarenin”. The Japanese chemist Jōkichi Takamine, who had set up his own laboratory in New York, invented an isolation procedure and obtained it in pure crystal form in 1901, and arranged for Parke-Davis

Parke-Davis is a subsidiary of the pharmaceutical company Pfizer. Although Parke, Davis & Co. is no longer an independent corporation, it was once America's oldest and largest drug maker, and played an important role in medical history. In 1970 ...

to market it as ”Adrenalin”, spelt without the terminal “e”. In 1903, natural adrenaline was found to be optically active

Optical rotation, also known as polarization rotation or circular birefringence, is the rotation of the orientation of the plane of polarization about the optical axis of linearly polarized light as it travels through certain materials. Circul ...

and levorotary

Optical rotation, also known as polarization rotation or circular birefringence, is the rotation of the orientation of the plane of polarization about the optical axis of linearly polarized light as it travels through certain materials. Circul ...

. In 1905 synthesis of the racemate was achieved by Friedrich Stolz

Friedrich Stolz (6 April 1860 – 2 April 1936) was a German chemist and, in 1904, the first person to artificially synthesize epinephrine (adrenaline).

References

*

1860 births

1936 deaths

19th-century German chemists

20th-century Ger ...

at Hoechst AG

Hoechst AG () was a German chemicals then life-sciences company that became Aventis Deutschland after its merger with France's Rhône-Poulenc S.A. in 1999. With the new company's 2004 merger with Sanofi-Synthélabo, it became a subsidiary of the ...

in Höchst (Frankfurt am Main)

Höchst ( or ) is a quarter of Frankfurt am Main, Germany. It is part of the ''Ortsbezirk West''.

Höchst am Main was annexed by Frankfurt am Main in 1928, at the same time as Sindlingen, Unterliederbach and Zeilsheim. Höchst is situated 10&nbs ...

and by Henry Drysdale Dakin

Henry Drysdale Dakin Fellow of the Royal Society, FRS (12 March 188010 February 1952) was an England, English chemist.

He was born in London as the youngest of 8 children to a family of steel merchants from Leeds. As a school boy, he conducted w ...

at the University of Leeds

, mottoeng = And knowledge will be increased

, established = 1831 – Leeds School of Medicine1874 – Yorkshire College of Science1884 - Yorkshire College1887 – affiliated to the federal Victoria University1904 – University of Leeds

, ...

. In 1906 the chemical structure was elucidated by Ernst Joseph Friedmann (1877–1956) in Strasbourg, and in 1908 the dextrorotary

Optical rotation, also known as polarization rotation or circular birefringence, is the rotation of the orientation of the plane of polarization about the optical axis of linearly polarized light as it travels through certain materials. Circul ...

enantiomer was shown to be almost inactive by Arthur Robertson Cushney (1866–1926) at the University of Michigan

, mottoeng = "Arts, Knowledge, Truth"

, former_names = Catholepistemiad, or University of Michigania (1817–1821)

, budget = $10.3 billion (2021)

, endowment = $17 billion (2021)As o ...

, leading him to conclude that ″the ‘receptive substance’ affected by adrenalin″ is able to discriminate between the optical isomers and, hence, itself optically active. Overall, 32 designations have been coined, of which “adrenaline”, preferred in the United Kingdom, and “epinephrine”, preferred in the United States, persist as generic names in the scientific literature.

Adrenaline as a transmitter

A new chapter was opened whenMax Lewandowsky

upPortrait of Lewandowsky

Max Lewandowsky (28 June 1876 – 4 April 1916) was a German neurologist, who was a native of Berlin, born into a Jewish family.

Personal life

Lewandowsky studied medicine at the Universities of Marburg, Berlin an ...

in 1899 in Berlin observed that adrenal extracts acted on the smooth muscle

Smooth muscle is an involuntary non-striated muscle, so-called because it has no sarcomeres and therefore no striations (''bands'' or ''stripes''). It is divided into two subgroups, single-unit and multiunit smooth muscle. Within single-unit mus ...

of the eye and orbit

In celestial mechanics, an orbit is the curved trajectory of an object such as the trajectory of a planet around a star, or of a natural satellite around a planet, or of an artificial satellite around an object or position in space such as a p ...

of cats – such as the iris dilator muscle

The iris dilator muscle (pupil dilator muscle, pupillary dilator, radial muscle of iris, radiating fibers), is a smooth muscle of the eye, running radially in the iris and therefore fit as a dilator. The pupillary dilator consists of a spokelike ...

and nictitating membrane

The nictitating membrane (from Latin '' nictare'', to blink) is a transparent or translucent third eyelid present in some animals that can be drawn across the eye from the medial canthus to protect and moisten it while maintaining vision. All ...

– in the same way as sympathetic nerve

The sympathetic nervous system (SNS) is one of the three divisions of the autonomic nervous system, the others being the parasympathetic nervous system and the enteric nervous system. The enteric nervous system is sometimes considered part of the ...

stimulation. The correspondence was extended by John Newport Langley

John Newport Langley (2 November 1852 – 5 November 1925) was a British physiologist, who made substantive discoveries about the nervous system and secretion.

Life

He was born in Newbury, Berkshire the son of John Langley, the local schoolmast ...

and, under his supervision, Thomas Renton Elliott

Thomas Renton Elliott (11 October 1877 – 4 March 1961) was a British physician and physiologist.

Biography

Elliott was born in Willington, County Durham, as the eldest son to retailer Archibald William Elliott and his wife, Anne, daughter of ...

in Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cambridge bec ...

. In four papers in volume 31, 1904, of the ''Journal of Physiology'' Elliott described the similarities organ by organ. His hypothesis stands in the abstract of a presentation to the Physiological Society

The Physiological Society, founded in 1876, is a learned society for physiologists in the United Kingdom.

History

The Physiological Society was founded in 1876 as a dining society "for mutual benefit and protection" by a group of 19 physiologist ...

of May 21, 1904, a little over ten years after Oliver and Schafer's presentation: ″Adrenalin does not excite sympathetic ganglia

A ganglion is a group of neuron cell bodies in the peripheral nervous system. In the somatic nervous system this includes dorsal root ganglia and trigeminal ganglia among a few others. In the autonomic nervous system there are both sympatheti ...

when applied to them directly, as does nicotine

Nicotine is a natural product, naturally produced alkaloid in the nightshade family of plants (most predominantly in tobacco and ''Duboisia hopwoodii'') and is widely used recreational drug use, recreationally as a stimulant and anxiolytic. As ...

. Its effective action is localized at the periphery. I find that even after complete denervation, whether of three days’ or ten months’ duration, the plain muscle of the dilatator pupillae will respond to adrenalin, and that with greater rapidity and longer persistence than does the iris whose nervous relations are uninjured. Therefore, it cannot be than adrenalin excites any structure derived from, and dependent for its persistence on, the peripheral neurone. ... The point at which the stimulus of the chemical excitant is received, and transformed into what may cause the change of tension of the muscle fiber, is perhaps a mechanism developed out of the muscle cell in response to its union with the synapsing sympathetic fiber, the function of which is to receive and transform the nervous impulse. "Adrenalin" might then be the chemical stimulant liberated on each occasion when the impulse arrives at the periphery.″ The abstract is the ″birth certificate″ of chemical neurotransmission. Elliott was never so explicit again. It seems he was discouraged by the lack of a favorable response from his seniors, Langley in particular, and a few years later he left physiological research.

Otto Loewi

Otto Loewi (; 3 June 1873 – 25 December 1961) was a German-born pharmacologist and psychobiologist who discovered the role of acetylcholine as an endogenous neurotransmitter. For his discovery he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Med ...

in Graz

Graz (; sl, Gradec) is the capital city of the Austrian state of Styria and second-largest city in Austria after Vienna. As of 1 January 2021, it had a population of 331,562 (294,236 of whom had principal-residence status). In 2018, the popul ...

demonstrated the ″humorale Übertragbarkeit der Herznervenwirkung″ in amphibian

Amphibians are tetrapod, four-limbed and ectothermic vertebrates of the Class (biology), class Amphibia. All living amphibians belong to the group Lissamphibia. They inhabit a wide variety of habitats, with most species living within terres ...

s. ''Vagusstoff'' transmitted inhibition from the vagus nerve

The vagus nerve, also known as the tenth cranial nerve, cranial nerve X, or simply CN X, is a cranial nerve that interfaces with the parasympathetic control of the heart, lungs, and digestive tract. It comprises two nerves—the left and right ...

s, and ''Acceleransstoff'' transmitted stimulation from the sympathetic nerves to the heart. Loewi took some years to commit himself with respect to the nature of the ''Stoffe'', but in 1926 he was sure that ''Vagusstoff'' was acetylcholine, writing in 1936 ″I no longer hesitate to identify the ''Sympathicusstoff'' with adrenaline.″

He was correct in the latter statement. In most amphibian organs including the heart, the concentration of adrenaline far exceeds that of noradrenaline, and adrenaline is indeed the main transmitter. In mammal

Mammals () are a group of vertebrate animals constituting the class Mammalia (), characterized by the presence of mammary glands which in females produce milk for feeding (nursing) their young, a neocortex (a region of the brain), fur or ...

s, however, difficulties arose. In a comprehensive structure-activity study of adrenaline-like compounds, Dale and the chemist George Barger

George Barger FRS FRSE FCS LLD (4 April 1878 – 5 January 1939) was a British chemist.

Life

He was born to an English mother, Eleanor Higginbotham, and Gerrit Barger, a Dutch engineer in Manchester, England.

He was educated at Utrecht and ...

in 1910 found that Elliott's hypothesis assumed a stricter parallelism between the effects of sympathetic nerve impulses and adrenaline than actually existed. For example, sympathetic impulses shared with adrenaline contractile effects in the trigone

Trigone may refer to:

* Trigone of the lateral ventricle

* Trigone of urinary bladder

The trigone (a.k.a. vesical trigone) is a smooth triangular region of the internal urinary bladder formed by the two ureteric orifices and the internal ure ...

but not relaxant effects in the fundus of the cat's urinary bladder

The urinary bladder, or simply bladder, is a hollow organ in humans and other vertebrates that stores urine from the kidneys before disposal by urination. In humans the bladder is a distensible organ that sits on the pelvic floor. Urine enters ...

. In this respect, ″amino-ethanol-catechol″ – noradrenaline – mimicked sympathetic nerves more closely than adrenaline did. The Harvard Medical School

Harvard Medical School (HMS) is the graduate medical school of Harvard University and is located in the Longwood Medical Area of Boston, Massachusetts. Founded in 1782, HMS is one of the oldest medical schools in the United States and is consi ...

physiologist Walter Bradford Cannon

Walter Bradford Cannon (October 19, 1871 – October 1, 1945) was an American physiologist, professor and chairman of the Department of Physiology at Harvard Medical School. He coined the term "fight or flight response", and developed the theory ...

, who had popularized the idea of a sympatho-adrenal system preparing the body for fight and flight, and his colleague Arturo Rosenblueth

Arturo Rosenblueth Stearns (October 2, 1900 – September 20, 1970) was a Mexican researcher, physician and physiologist, who is known as one of the pioneers of cybernetics.

Biography

Rosenblueth was born in 1900 in Ciudad Guerrero, Chihuahua ...

developed an elaborate but ″queer″Z. M. Bacq ZM: ''Chemical transmission of nerve impulses.'' In: M. J. Parnham, J. Bruinvels (Eds.): ''Discoveries in Pharmacology.'' Amsterdam, Elsevier, 1983, vol. 1, pp 49–103. . theory of two ''sympathins'', ''sympathin E'' (excitatory) and ''sympathin I'' (inhibitory). The Belgian pharmacologist Zénon Bacq as well as Canadian and US-American pharmacologists between 1934 and 1938 suggested that noradrenaline might be the – or at least one – postganglionic sympathetic transmitter.H. Blaschko: ''Catecholamines 1922–1971''. In: H. Blaschko und E. Muscholl (Ed.): ''Catcholamines. Handbuch der experimentellen Pharmakologie'' volume 33. Berlin, Springer-Verlag, 1972, pp. 1–15. . However, nothing definite was brought to light till after the war. In the meantime, Dale created a terminology that has since imprinted the thinking of neuroscientist

A neuroscientist (or neurobiologist) is a scientist who has specialised knowledge in neuroscience, a branch of biology that deals with the physiology, biochemistry, psychology, anatomy and molecular biology of neurons, Biological neural network, n ...

s: nerve cells should be named after their transmitter, i.e. ''cholinergic'' if the transmitter was ″a substance like acetylcholine", and ''adrenergic'' if it was ″some substance like adrenaline″.

In 1936, the year when Loewi accepted adrenaline as the (amphibian) sympathetic transmitter, Dale and Loewi received the ''Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine

The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine is awarded yearly by the Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institute for outstanding discoveries in physiology or medicine. The Nobel Prize is not a single prize, but five separate prizes that, accord ...

'' ″for their discoveries relating to chemical transmission of nerve impulses″.

Formation and destruction

″Our modern knowledge of thebiosynthetic

Biosynthesis is a multi-step, enzyme-Catalysis, catalyzed process where substrate (chemistry), substrates are converted into more complex Product (chemistry), products in living organisms. In biosynthesis, simple Chemical compound, compounds are mo ...

pathway for the catecholamines begins in 1939, with the publication of a paper by Peter Holtz and his colleagues: they described the presence in the guinea-pig kidneys of an enzyme that they called dopa decarboxylase

Aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase (AADC or AAAD), also known as DOPA decarboxylase (DDC), tryptophan decarboxylase, and 5-hydroxytryptophan decarboxylase, is a lyase enzyme (), located in region 7p12.2-p12.1.

Mechanism

The enzyme uses pyrid ...

, because it catalyzed the formation of dopamine and carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide (chemical formula ) is a chemical compound made up of molecules that each have one carbon atom covalently double bonded to two oxygen atoms. It is found in the gas state at room temperature. In the air, carbon dioxide is transpar ...

from the amino acid L-dopa

-DOPA, also known as levodopa and -3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine, is an amino acid that is made and used as part of the normal biology of some plants and animals, including humans. Humans, as well as a portion of the other animals that utilize -DOPA ...

.″ The German-British biochemist Hermann Blaschko (1900–1993), who in 1933 had left Germany because he was Jewish, wrote this in 1987 in Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

, looking back on “a half-century of research on catecholamine biosynthesis”. The paper by Peter Holtz (1902–1970) and his coworkers originated from the Institute of Pharmacology in Rostock

Rostock (), officially the Hanseatic and University City of Rostock (german: link=no, Hanse- und Universitätsstadt Rostock), is the largest city in the German state of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern and lies in the Mecklenburgian part of the state, c ...

. Already in that same year both Blaschko, then in Cambridge, and Holtz in Rostock predicted the entire sequence tyrosine

-Tyrosine or tyrosine (symbol Tyr or Y) or 4-hydroxyphenylalanine is one of the 20 standard amino acids that are used by cells to synthesize proteins. It is a non-essential amino acid with a polar side group. The word "tyrosine" is from the Gr ...

→ l-DOPA → ''oxytyramine'' = dopamine → noradrenaline → adrenaline. Edith Bülbring, who also had fled National Socialist

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Na ...

racism

Racism is the belief that groups of humans possess different behavioral traits corresponding to inherited attributes and can be divided based on the superiority of one race over another. It may also mean prejudice, discrimination, or antagonism ...

in 1933, demonstrated methylation

In the chemical sciences, methylation denotes the addition of a methyl group on a substrate, or the substitution of an atom (or group) by a methyl group. Methylation is a form of alkylation, with a methyl group replacing a hydrogen atom. These t ...

of noradrenaline to adrenaline in adrenal tissue in Oxford in 1949, and Julius Axelrod

Julius Axelrod (May 30, 1912 – December 29, 2004) was an American biochemist. He won a share of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1970 along with Bernard Katz and Ulf von Euler. The Nobel Committee honored him for his work on the re ...

detected phenylethanolamine N-methyltransferase

Phenylethanolamine ''N''-methyltransferase (PNMT) is an enzyme found primarily in the adrenal medulla that converts norepinephrine (noradrenaline) to epinephrine (adrenaline). It is also expressed in small groups of neurons in the human brain and ...

in Bethesda, Maryland

Bethesda () is an unincorporated, census-designated place in southern Montgomery County, Maryland. It is located just northwest of Washington, D.C. It takes its name from a local church, the Bethesda Meeting House (1820, rebuilt 1849), which in ...

in 1962. The two remaining enzymes, tyrosine hydroxylase

Tyrosine hydroxylase or tyrosine 3-monooxygenase is the enzyme responsible for catalyzing the conversion of the amino acid L-tyrosine to L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (L-DOPA). It does so using molecular oxygen (O2), as well as iron (Fe2+) and t ...

and dopamine β-hydroxylase

Dopamine beta-hydroxylase (DBH), also known as dopamine beta-monooxygenase, is an enzyme () that in humans is encoded by the DBH gene. Dopamine beta-hydroxylase catalyzes the conversion of dopamine to norepinephrine.

The three substrates of ...

, were also characterized around 1960.

Even before contributing to the formation pathway, Blaschko had discovered a destruction mechanism. An enzyme ''tyramine oxidase'' described in 1928 also oxidized dopamine, noradrenaline and adrenaline. It was later named ''monoamine oxidase

Monoamine oxidases (MAO) () are a family of enzymes that catalyze the oxidation of monoamines, employing oxygen to clip off their amine group. They are found bound to the outer membrane of mitochondria in most cell types of the body. The first ...

''. This seemed to clarify the fate of the catecholamines in the body, but in 1956 Blaschko suggested that, because the oxidation was slow, “other mechanisms of inactivation … will be found to play an important part. Here is a gap in our knowledge which remains to be filled.” Within a year, Axelrod narrowed the gap by showing that dopamine, noradrenaline and adrenaline were O-methylated by catechol-O-methyl transferase

Catechol-''O''-methyltransferase (COMT; ) is one of several enzymes that degrade catecholamines (neurotransmitters such as dopamine, epinephrine, and norepinephrine), catecholestrogens, and various drugs and substances having a catechol structu ...

. To fill the gap completely, however, the role of membranes had to be appreciated ().

Noradrenaline

Thanks to Holtz and Blaschko it was clear that animals synthesized noradrenaline. What was needed to attribute a transmitter role to it was proof of its presence in tissues at effective concentrations and not only as a short-lived intermediate. On April 16, 1945,Ulf von Euler

Ulf Svante von Euler (7 February 1905 – 9 March 1983) was a Swedish physiologist and pharmacologist. He shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1970 for his work on neurotransmitters.

Life

Ulf Svante von Euler-Chelpin was born in S ...

of Karolinska Institute

The Karolinska Institute (KI; sv, Karolinska Institutet; sometimes known as the (Royal) Caroline Institute in English) is a research-led medical university in Solna within the Stockholm urban area of Sweden. The Karolinska Institute is consist ...

in Stockholm, who had already discovered or co-discovered substance P

Substance P (SP) is an undecapeptide (a peptide composed of a chain of 11 amino acid residues) and a member of the tachykinin neuropeptide family. It is a neuropeptide, acting as a neurotransmitter and as a neuromodulator. Substance P and its clos ...

and prostaglandin

The prostaglandins (PG) are a group of physiologically active lipid compounds called eicosanoids having diverse hormone-like effects in animals. Prostaglandins have been found in almost every tissue in humans and other animals. They are derive ...

s, submitted to ''Nature'' the first of a series of papers that gave this proof. After many bioassays and chemical assays on organ extracts he concluded that mammalian sympathetically innervated tissues as well as, in small amounts, the brain, but not the nerve-free placenta

The placenta is a temporary embryonic and later fetal organ that begins developing from the blastocyst shortly after implantation. It plays critical roles in facilitating nutrient, gas and waste exchange between the physically separate mater ...

, contained noradrenaline and that noradrenaline was the ''sympathy'' of Cannon and Rosenblueth, the ″physiological transmitter of adrenergic nerve action in mammals″. Overflow of noradrenaline into the venous blood of the cat's spleen upon sympathetic nerve stimulation two years later bore out the conclusion. In amphibian hearts, on the other hand, the transmitter role of adrenaline was confirmed.

The war prevented Peter Holtz and his group in Rostock from being recognized side by side with von Euler as discoverers of the second catecholamine transmitter noradrenaline. Their approach was different. They sought for catecholamines in human urine and found a blood pressure-increasing material ''Urosympathin'' that they identified as a mixture of dopamine, noradrenaline and adrenaline. “As to the origin of ''Urosympathin'' we would like to suggest the following. Dopamine in urine is the fraction that was not consumed for the synthesis of ''sympathin E'' and ''I''. … ''Sympathin E'' and ''I'', i.e. noradrenaline and adrenaline, are liberated in the region of the sympathetic nerve endings when these are excited.” The manuscript was received by Springer-Verlag

Springer Science+Business Media, commonly known as Springer, is a German multinational publishing company of books, e-books and peer-reviewed journals in science, humanities, technical and medical (STM) publishing.

Originally founded in 1842 in ...

in Leipzig on October 8, 1944. On October 15, the printing office in Braunschweig

Braunschweig () or Brunswick ( , from Low German ''Brunswiek'' , Braunschweig dialect: ''Bronswiek'') is a city in Lower Saxony, Germany, north of the Harz Mountains at the farthest navigable point of the river Oker, which connects it to the Nor ...

was destroyed by an airstrike. Publication was delayed to volume 204, 1947, of ''Naunyn-Schmiedebergs Archiv für Pharmakologie und Experimentelle Pathologie''. Peter Holtz later used to cite the paper as ″Holtz et al. 1944/47″ or ″Holtz, Credner and Kroneberg 1944/47″.

Remembering his and Barger's structure-activity analysis of 1910, Dale wrote in 1953: “Doubtless I ought to have seen that nor-adrenaline might be the main transmitter – that Elliott’s theory might be right in principle and faulty only in this detail. … It is easy, of course, to be wise in the light of facts recently discovered; lacking them I failed to jump to the truth, and I can hardly claim credit for having crawled so near and then stopped short of it.”

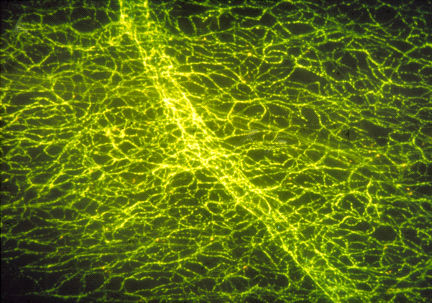

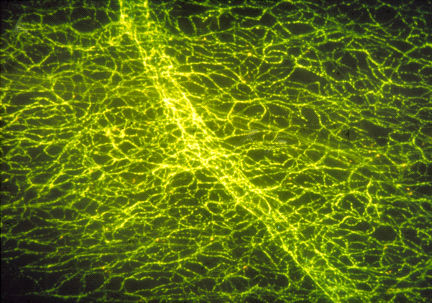

The next step led to the central nervous system. It was taken by

The next step led to the central nervous system. It was taken by Marthe Vogt

Marthe Louise Vogt (September 8, 1903 – September 9, 2003) was a German scientist recognized as one of the leading neuroscientists of the twentieth century. She is mainly remembered for her important contributions to the understanding of t ...

, a refugee from Germany who at that time worked with John Henry Gaddum

Sir John Henry Gaddum (31 March 1900 – 30 June 1965) was an English pharmacologist who, with Ulf von Euler, co-discovered the neuropeptide Substance P in 1931. He was a founder member of the British Pharmacological Society and first edit ...

in the Institute of Pharmacology of the University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh ( sco, University o Edinburgh, gd, Oilthigh Dhùn Èideann; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in post-nominals) is a public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Granted a royal charter by King James VI in 15 ...

. ″The presence of noradrenaline and adrenaline in the brain has been demonstrated by von Euler (1946) and Holtz (1950). These substances were supposed, undoubtedly correctly, to occur in the cerebral vasomotor <= vasoconstrictor> nerves. The present work is concerned with the question whether these sympathomimetic amines

Sympathomimetic drugs (also known as adrenergic drugs and adrenergic amines) are stimulant compounds which mimic the effects of endogenous agonists of the sympathetic nervous system. Examples of sympathomimetic effects include increases in heart ...

, besides their role as transmitters at vasomotor endings, play a part in the function of the central nervous tissue itself. In this paper, these amines will be referred to as ''sympathin'', since they were found invariably to occur together, with noradrenaline representing the major component, as is characteristic for the transmitter of the peripheral sympathetic system.″ Vogt created a detailed map of noradrenaline in the dog brain. Its uneven distribution, not reflecting the distribution of vasomotor nerves, and its persistence after removal of the superior cervical ganglia made it ″tempting to assign to the cerebral ''sympathin'' a transmitter role like that which we assign to the ''sympathin'' found in the sympathetic ganglia and their postganglionic fibers.″ Her assignment was confirmed, the finishing touch being the visualization of the noradrenaline as well as adrenaline and () dopamine pathways in the central nervous system by Annica Dahlström

Annica Dahlström (born 1941) is a Swedish physician and Professor Emerita of Histology and Neuroscience at the Department of Medical Chemistry and Cell Biology at Gothenburg University.

Dahlström's research focuses on how nerve cells store and t ...

and with the formaldehyde fluorescence method developed by Nils-Åke Hillarp

Nils-Åke Hillarp (4 July 1916 – 17 March 1965) was a Swedish scientist and a prominent force in research on the brain's monoamines.

Biography

Hillarp was the son of merchant Nils Bengtsson and Hulda, former Johansson, and the brother of Rut Hi ...

(1916–1965) and Bengt Falck (born 1927) in Sweden and by immunochemistry

Immunochemistry is the study of the chemistry of the immune system. This involves the study of the properties, functions, interactions and production of the chemical components (antibodies/immunoglobulins, toxin, epitopes of proteins like CD4, a ...

techniques.

Dopamine

As noradrenaline is an intermediate on the path to adrenaline, dopamine is on the path to noradrenaline (and hence adrenaline.) In 1957 dopamine was identified in the human brain by researcherKatharine Montagu

Katharine Montagu was the first researcher to identify dopamine in human brains.

Working in Hans Weil-Malherbe’s laboratory at the Runwell Hospital outside London the presence of dopamine was identified by paper chromatography in the brain of ...

. In 1958/59 Arvid Carlsson

Arvid Carlsson (25 January 1923 – 29 June 2018) was a Swedish neuropharmacologist who is best known for his work with the neurotransmitter dopamine and its effects in Parkinson's disease. For his work on dopamine, Carlsson was awarded the No ...

and his group in the Pharmacology Department of the University of Lund

, motto = Ad utrumque

, mottoeng = Prepared for both

, established =

, type = Public research university

, budget = SEK 9 billion corpus striatum

The striatum, or corpus striatum (also called the striate nucleus), is a nucleus (a cluster of neurons) in the subcortical basal ganglia of the forebrain. The striatum is a critical component of the motor and reward systems; receives glutamat ...

, which contained only traces of noradrenaline. Carlsson's group had previously found that reserpine

Reserpine is a drug that is used for the treatment of high blood pressure, usually in combination with a thiazide diuretic or vasodilator. Large clinical trials have shown that combined treatment with reserpine plus a thiazide diuretic reduces m ...

, which was known to cause a Parkinsonism

Parkinsonism is a clinical syndrome characterized by tremor, bradykinesia (slowed movements), rigidity, and postural instability. These are the four motor symptoms found in Parkinson's disease (PD), after which it is named, dementia with Lewy bo ...

syndrome, depleted dopamine (as well as noradrenaline and serotonin) from the brain. They concluded that ″dopamine is concerned with the function of the corpus striatum and thus with the control of motor function″. Thus for the first time the reserpine-induced Parkinsonism in laboratory animals and, by implication, Parkinson's disease

Parkinson's disease (PD), or simply Parkinson's, is a long-term degenerative disorder of the central nervous system that mainly affects the motor system. The symptoms usually emerge slowly, and as the disease worsens, non-motor symptoms becom ...

in humans was related to depletion of striatal dopamine. A year later Oleh Hornykiewicz

Oleh Hornykiewicz (17 November 1926 - 26 May 2020) was an Austrian biochemist.

Life

Oleh Hornykiewicz was born in 1926 in Sykhiw (a district of Lviv), then in Poland (now Ukraine). In 1951, he received his M.D. degree from the University of Vie ...

, who had been introduced to dopamine by Blaschko and was carrying out a color reaction on extracts of human corpus striatum in the Pharmacological Institute of the University of Vienna

The University of Vienna (german: Universität Wien) is a public research university located in Vienna, Austria. It was founded by Duke Rudolph IV in 1365 and is the oldest university in the German-speaking world. With its long and rich histor ...

, saw the brain dopamine deficiency in Parkinson's disease ″with Membrane passage

Membranes

A membrane is a selective barrier; it allows some things to pass through but stops others. Such things may be molecules, ions, or other small particles. Membranes can be generally classified into synthetic membranes and biological membranes. Bi ...

play a twofold role for catecholamines: catecholamines must pass through membranes and deliver their chemical message at membrane receptors

Receptor may refer to:

*Sensory receptor, in physiology, any structure which, on receiving environmental stimuli, produces an informative nerve impulse

*Receptor (biochemistry), in biochemistry, a protein molecule that receives and responds to a n ...

.

Catecholamines are synthesized inside cells and sequestered in intracellular vesicles. This was first shown by Blaschko and Arnold Welch (1908–2003) in Oxford and by Hillarp and his group in Lund for the adrenal medulla and later for sympathetic nerves and the brain. In addition the vesicles contained adenosine triphosphate

Adenosine triphosphate (ATP) is an organic compound that provides energy to drive many processes in living cells, such as muscle contraction, nerve impulse propagation, condensate dissolution, and chemical synthesis. Found in all known forms of ...

(ATP), with a molar noradrenaline:ATP ratio in sympathetic nerve vesicles of 5.2:1 as determined by Hans-Joachim Schümann (1919–1998) and Horst Grobecker (born 1934) in Peter Holtz′ group at the Goethe University Frankfurt

Goethe University (german: link=no, Johann Wolfgang Goethe-Universität Frankfurt am Main) is a university located in Frankfurt am Main, Germany. It was founded in 1914 as a citizens' university, which means it was founded and funded by the wealt ...

. Blaschko and Welch wondered how the catecholamines got out when nervous impulses reached the cells. Exocytosis

Exocytosis () is a form of active transport and bulk transport in which a cell transports molecules (e.g., neurotransmitters and proteins) out of the cell ('' exo-'' + ''cytosis''). As an active transport mechanism, exocytosis requires the use o ...

was not among the possibilities they considered. It required the analogy of the ″quantal″ release of acetylcholine at the neuromuscular junction

A neuromuscular junction (or myoneural junction) is a chemical synapse between a motor neuron and a muscle fiber.

It allows the motor neuron to transmit a signal to the muscle fiber, causing muscle contraction.

Muscles require innervation to ...

shown by Bernard Katz

Sir Bernard Katz, Fellow of the Royal Society, FRS (; 26 March 1911 – 20 April 2003) was a German-born British people, British physician and biophysics, biophysicist, noted for his work on nerve physiology. He shared the Nobel Prize in Physiol ...

, third winner of the 1970 ''Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine''; the demonstration of the co-release with catecholamines of other vesicle constituents such as ATP and dopamine β-hydroxylase; and the unquestionable electron microscopic images of vesicles fusing with the cell membrane

The cell membrane (also known as the plasma membrane (PM) or cytoplasmic membrane, and historically referred to as the plasmalemma) is a biological membrane that separates and protects the interior of all cells from the outside environment ( ...

– to establish exocytosis.

Acetylcholine, once released, is degraded in the extracellular space

Extracellular space refers to the part of a multicellular organism outside the cells, usually taken to be outside the plasma membranes, and occupied by fluid. This is distinguished from intracellular space, which is inside the cells.

The compositi ...

by acetylcholinesterase

Acetylcholinesterase (HGNC symbol ACHE; EC 3.1.1.7; systematic name acetylcholine acetylhydrolase), also known as AChE, AChase or acetylhydrolase, is the primary cholinesterase in the body. It is an enzyme

Enzymes () are proteins that a ...

, which faces that space. In the case the catecholamines, however, the enzymes of degradation monoamine oxidase and catechol-O-methyl transferase, like the enzymes of synthesis, are intracellular. Not metabolism but uptake through cell membranes therefore is the primary means of their clearance from the extracellular space. The mechanisms were deciphered beginning in 1959. Axelrod's group in Bethesda wished to clarify the in vivo

Studies that are ''in vivo'' (Latin for "within the living"; often not italicized in English) are those in which the effects of various biological entities are tested on whole, living organisms or cells, usually animals, including humans, and ...

fate of catecholamines using radioactively labelled catecholamines of high specific activity

Specific activity is the activity per unit mass of a radionuclide and is a physical property of that radionuclide.

Activity is a quantity (for which the SI unit is the becquerel) related to radioactivity, and is defined as the number of radi ...

, which had just become available. 3H-adrenaline and 3H-noradrenaline given intravenously to cats were partly O-methylated, but another part was taken up in the tissues and stored unchanged. Erich Muscholl (born 1926) in Mainz

Mainz () is the capital and largest city of Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany.

Mainz is on the left bank of the Rhine, opposite to the place that the Main (river), Main joins the Rhine. Downstream of the confluence, the Rhine flows to the north-we ...

, who had worked with Marthe Vogt in Edinburgh, wished to know how cocaine

Cocaine (from , from , ultimately from Quechuan languages, Quechua: ''kúka'') is a central nervous system (CNS) stimulant mainly recreational drug use, used recreationally for its euphoria, euphoric effects. It is primarily obtained from t ...

sensitized tissues to catecholamines – a fundamental mechanism of action of cocaine discovered by Otto Loewi and Alfred Fröhlich

Alfred Fröhlich (August 15, 1871 – March 22, 1953) was an Austrian-American pharmacologist and neurologist born in Vienna.

Biography

Fröhlich was born in Vienna, into a Jewish family.Joseph Meites, ''Pioneers in Neuroendocrinology'', Spr ...

in 1910 in Vienna. Intravenous noradrenaline was taken up into the heart and spleen of rats, and cocaine prevented the uptake, ″thus increasing the amount of noradrenaline available for combination with the adrenergic receptors″. The uptake of 3H-noradrenaline was severely impaired after sympathectomy

A sympathectomy is an irreversible procedure during which at least one sympathetic ganglion is removed. One example is the lumbar sympathectomy, which is advised for occlusive arterial disease in which L2 and L3 ganglia along with intervening sym ...

, indicating that it occurred mainly into sympathetic nerve terminals. In support of this, Axelrod and Georg Hertting (born 1925) showed that freshly incorporated 3H-noradrenaline was re-released from the cat spleen when the sympathetic nerves were stimulated. A few years later, Leslie Iversen (born 1937) in Cambridge found that other cells also took up catecholamines. He called uptake into noradrenergic neurons, which were cocaine-sensitive, ''uptake1'' and uptake into other cells, which were cocaine-resistant, ''uptake2''. With the reserpine-sensitive uptake from the cytoplasm

In cell biology, the cytoplasm is all of the material within a eukaryotic cell, enclosed by the cell membrane, except for the cell nucleus. The material inside the nucleus and contained within the nuclear membrane is termed the nucleoplasm. The ...

into the storage vesicles there were thus three catecholamine membrane passage mechanisms. Iversen's book of 1967 “The Uptake and Storage of Noradrenaline in Sympathetic Nerves” was successful, showing the fascination of the field and its rich pharmacology.

With the advent of molecular genetics

Molecular genetics is a sub-field of biology that addresses how differences in the structures or expression of DNA molecules manifests as variation among organisms. Molecular genetics often applies an "investigative approach" to determine the ...

, the three transport mechanisms have been traced to the proteins and their genes since 1990. They now comprise the plasma membrane ''noradrenaline transporter

The norepinephrine transporter (NET), also known as noradrenaline transporter (NAT), is a protein that in humans is encoded by the solute carrier family 6 member 2 (SLC6A2) gene.

NET is a monoamine transporter and is responsible for the sodium- ...

'' (NAT or NET), the classical uptake1, and the analogous ''dopamine transporter

The dopamine transporter (also dopamine active transporter, DAT, SLC6A3) is a membrane-spanning protein that pumps the neurotransmitter dopamine out of the synaptic cleft back into cytosol. In the cytosol, other transporters sequester the dopam ...

'' (DAT); the plasma membrane ''extraneuronal monoamine transporter'' or ''organic cation transporter 3'' (EMT or SLC22A3

Solute carrier family 22 member 3 (SLC22A3) also known as the organic cation transporter 3 (OCT3) or extraneuronal monoamine transporter (EMT) is a protein that in humans is encoded by the ''SLC22A3'' gene.

Polyspecific organic cation transporter ...

), Iversen's uptake2; and the ''vesicular monoamine transporter

The vesicular monoamine transporter (VMAT) is a transport protein integrated into the membranes of synaptic vesicles of presynaptic neurons. It transports monoamine neurotransmitters – such as dopamine, serotonin, norepinephrine, epinephrine, ...

'' (VMAT) with two isoforms. Transporters and intracellular enzymes such as monoamine oxidase operating in series constitute what the pharmacologist Ullrich Trendelenburg at the University of Würzburg

The Julius Maximilian University of Würzburg (also referred to as the University of Würzburg, in German ''Julius-Maximilians-Universität Würzburg'') is a public research university in Würzburg, Germany. The University of Würzburg is one of ...

called ''metabolizing systems''.

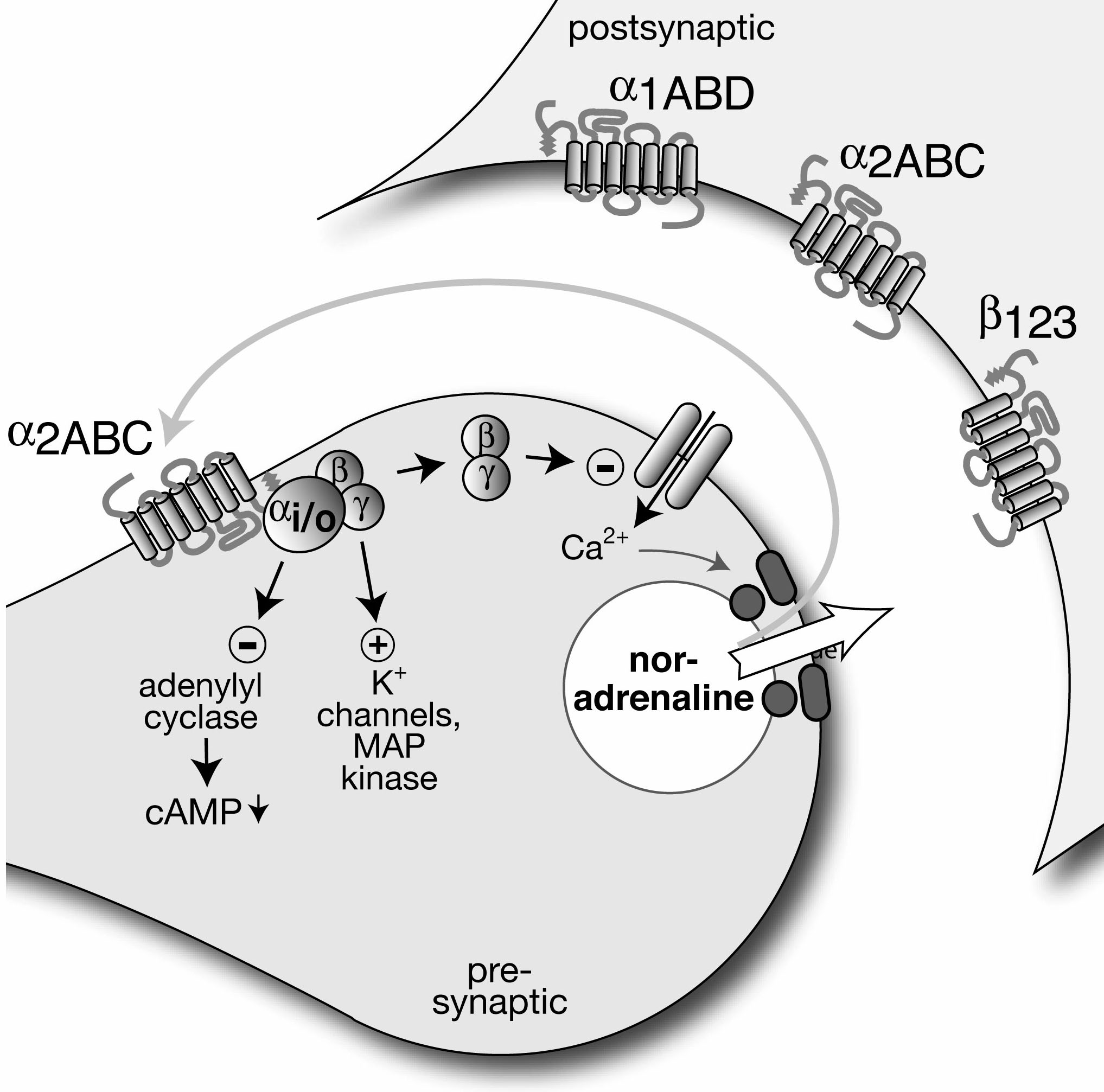

Receptors

Research on the catecholamines was interwoven with research on their receptors. In 1904, Dale became head of the Wellcome Physiological Research Laboratory in London and started research on

Research on the catecholamines was interwoven with research on their receptors. In 1904, Dale became head of the Wellcome Physiological Research Laboratory in London and started research on ergot

Ergot ( ) or ergot fungi refers to a group of fungi of the genus ''Claviceps''.

The most prominent member of this group is ''Claviceps purpurea'' ("rye ergot fungus"). This fungus grows on rye and related plants, and produces alkaloids that ca ...

extracts. The relevance of his communication in 1906 ″On some physiological actions of ergot″ lies less in the effects of the extracts given alone than in their interaction with adrenaline: they reversed the normal pressor effect of adrenaline to a depressor effect and the normal contraction effect on the early-pregnant cat's uterus

The uterus (from Latin ''uterus'', plural ''uteri'') or womb () is the organ in the reproductive system of most female mammals, including humans that accommodates the embryonic and fetal development of one or more embryos until birth. The uter ...

to relaxation: ''adrenaline reversal''. The pressor and uterine contraction effects of pituitary extracts, in contrast, remained unchanged, as did the effects of adrenaline on the heart and effects of parasympathetic nerve

The parasympathetic nervous system (PSNS) is one of the three divisions of the autonomic nervous system, the others being the sympathetic nervous system and the enteric nervous system. The enteric nervous system is sometimes considered part of t ...

stimulation. Dale clearly saw the specificity of the ″paralytic″ (antagonist

An antagonist is a character in a story who is presented as the chief foe of the protagonist.

Etymology

The English word antagonist comes from the Greek ἀνταγωνιστής – ''antagonistēs'', "opponent, competitor, villain, enemy, riv ...

) effect of ergot for ″the so-called myoneural junctions connected with the true sympathetic or thoracic

The thorax or chest is a part of the anatomy of humans, mammals, and other tetrapod animals located between the neck and the abdomen. In insects, crustaceans, and the extinct trilobites, the thorax is one of the three main divisions of the crea ...

-lumbar

In tetrapod anatomy, lumbar is an adjective that means ''of or pertaining to the abdominal segment of the torso, between the diaphragm and the sacrum.''

The lumbar region is sometimes referred to as the lower spine, or as an area of the back i ...

division of the autonomic nervous system

The autonomic nervous system (ANS), formerly referred to as the vegetative nervous system, is a division of the peripheral nervous system that supplies viscera, internal organs, smooth muscle and glands. The autonomic nervous system is a control ...

″ – the adrenoceptors. He also saw its specificity for the ″myoneural junctions″ mediating smooth muscle contraction as opposed to those mediating smooth muscle relaxation. But there he stopped. He did not conceive any close relationship between the smooth muscle-inhibitory and the cardiac sites of action of catecholamines.

Catecholamine receptors persisted in this wavering state for more than forty years. Additional blocking agents were found such as tolazoline

Tolazoline is a non-selective competitive α-adrenergic receptor antagonist. It is a vasodilator that is used to treat spasms of peripheral blood vessels (as in acrocyanosis). It has also been used (in conjunction with sodium nitroprusside) ...

in Switzerland and phenoxybenzamine

Phenoxybenzamine (marketed under the trade names Dibenzyline and Dibenyline) is a non-selective, irreversible alpha blocker.

Uses

It is used in the treatment of hypertension, and specifically that caused by pheochromocytoma. It has a slower on ...

in the United States, but like the ergot alkaloid

Alkaloids are a class of basic, naturally occurring organic compounds that contain at least one nitrogen atom. This group also includes some related compounds with neutral and even weakly acidic properties. Some synthetic compounds of similar ...

s they blocked only the smooth muscle excitatory receptors. Additional agonist

An agonist is a chemical that activates a receptor to produce a biological response. Receptors are cellular proteins whose activation causes the cell to modify what it is currently doing. In contrast, an antagonist blocks the action of the ago ...

s also were synthesized. Outstanding among them became isoprenaline, N-isopropyl

In organic chemistry, propyl is a three-carbon alkyl substituent with chemical formula for the linear form. This substituent form is obtained by removing one hydrogen atom attached to the terminal carbon of propane. A propyl substituent is ofte ...

-noradrenaline, of Boehringer Ingelheim

C.H. Boehringer Sohn AG & Co. is the parent company of the Boehringer Ingelheim group, which was founded in 1885 by Albert Boehringer in Ingelheim am Rhein, Germany. As of 2018, Boehringer Ingelheim is one of the world's largest pharmaceutical ...

, studied pharmacologically along with adrenaline and other N-substituted noradrenaline derivatives by Richard Rössler (1897–1945) and Heribert Konzett (1912–2004) in Vienna. The Viennese pharmacologists used their own ''Konzett-Rössler test'' to examine bronchodilation. Intravenous injection of pilocarpine

Pilocarpine is a medication used to reduce pressure inside the eye and treat dry mouth. As eye drops it is used to manage angle closure glaucoma until surgery can be performed, ocular hypertension, primary open angle glaucoma, and to bring abou ...

to induce bronchospasm

Bronchospasm or a bronchial spasm is a sudden constriction of the muscles in the walls of the bronchioles. It is caused by the release (degranulation) of substances from mast cells or basophils under the influence of anaphylatoxins. It causes di ...

was followed by intravenous injection of the agonists. “Arrangement of all amines according to their bronchodilator effect yields a series from the most potent, isopropyl-adrenaline, via the approximately equipotent bodies adrenaline, propyl

In organic chemistry, propyl is a three-carbon alkyl substituent with chemical formula for the linear form. This substituent form is obtained by removing one hydrogen atom attached to the terminal carbon of propane. A propyl substituent is often ...

-adrenaline and butyl

In organic chemistry, butyl is a four-carbon alkyl radical or substituent group with general chemical formula , derived from either of the two isomers (''n''-butane and isobutane) of butane.

The isomer ''n''-butane can connect in two ways, givi ...

-adrenaline, to the weakly active isobutyl

In organic chemistry, butyl is a four-carbon alkyl radical or substituent group with general chemical formula , derived from either of the two isomers (''n''-butane and isobutane) of butane.

The isomer ''n''-butane can connect in two ways, givi ...

-adrenaline.” Isoprenaline also exerted marked positive chronotropic

Chronotropic effects (from ''chrono-'', meaning time, and ''tropos'', "a turn") are those that change the heart rate.

Chronotropic drugs may change the heart rate and rhythm by affecting the electrical conduction system of the heart and the ner ...

and inotropic

An inotrope is an agent that alters the force or energy of muscular contractions. Negatively inotropic agents weaken the force of muscular contractions. Positively inotropic agents increase the strength of muscular contraction.

The term ''inotro ...

effects. Boehringer introduced it for use in asthma in 1940. After the war it became available to Germany's former enemies and over the years was traded under about 50 names. In addition to this therapeutic success it was one of the agonists with which Raymond P. Ahlquist

Raymond Perry Ahlquist (July 26, 1914 – April 15, 1983) was an American pharmacist and pharmacologist. He published seminal work in 1948 that divided adrenoceptors into α- and β-adrenoceptor subtypes. This discovery explained the acti ...

solved the ″myoneural junction″ riddle. “By virtue of this property the reputation of the substance spread all over the world and it became a tool for many investigations on different aspects of pharmacology and therapeutics.” The story had a dark side: overdosage caused numerous deaths due to cardiac side effects, an estimated three thousands in the United Kingdom alone.

Ahlquist was head of the Department of Pharmacology of the University of Georgia

, mottoeng = "To teach, to serve, and to inquire into the nature of things.""To serve" was later added to the motto without changing the seal; the Latin motto directly translates as "To teach and to inquire into the nature of things."

, establ ...

School of Medicine, now Georgia Regents University

Augusta University (AU) is a public research university and academic medical center in Augusta, Georgia. It is a part of the University System of Georgia and has satellite medical campuses in Savannah, Albany, Rome, and Athens. It employs over ...

. In 1948 he saw what had escaped Dale in 1906. “The adrenotropic receptors have been considered to be of two classes, those whose action results in excitation and those whose action results in inhibition of the effector cells. Experiments described in this paper indicate that although there are two kinds of adrenotropic receptors they cannot be classified simply as excitatory or inhibitory since each kind of receptor may have either action depending on where it is found.” Ahlquist chose six agonists, including adrenaline, noradrenaline, α-methylnoradrenaline and isoprenaline, and examined their effects on several organs. He found that the six substances possessed two – and only two – rank orders of potency in these organs. For example, the rank order of potency was ″adrenaline > noradrenaline > α-methylnoradrenaline > isoprenaline″ in promoting contraction of blood vessels, but ″isoprenaline > adrenaline > α-methylnoradrenaline > noradrenaline″ in stimulating the heart. The receptor with the first rank order (for example for blood vessel contraction) he called ''alpha adrenotropic receptor'' (now ''α-adrenoceptor'' or ''α-adrenergic receptor''), while the receptor with the second rank order (for instance for stimulation of the heart, but also for bronchodilation) he called ''beta adrenotropic receptor'' (now ''β-adrenoceptor'' or ''β-adrenergic receptor''). ″This concept of two fundamental types of receptors is directly opposed to the concept of two mediator substances (''sympathin E'' and ''sympathin I'') as propounded by Cannon and Rosenblueth and now widely quoted as ‘law’ of physiology. ... There is only one adrenergic neuro-hormone, or ''sympathin'', and that ''sympathin'' is identical with epinephrine.”