History of Venice on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The

The

The Quadi and

The Quadi and

During the reign of the successor of the Participazio,

During the reign of the successor of the Participazio,

(available on-line)

Around 841, the

In the

In the

Venice was asked to provide transportation for the Fourth Crusade, but when the crusaders could not pay for chartering their shipping, the doge

Venice was asked to provide transportation for the Fourth Crusade, but when the crusaders could not pay for chartering their shipping, the doge

In the early 15th century, the Venetians further expanded their possessions in Northern Italy, and assumed the definitive control of the Dalmatian coast, which was acquired from

In the early 15th century, the Venetians further expanded their possessions in Northern Italy, and assumed the definitive control of the Dalmatian coast, which was acquired from  On May 29, 1453

On May 29, 1453

The

The  Difficulties in the rule of the sea brought further changes. Until 1545 the oarsmen in the galleys were free sailors enrolled on a wage. They were originally Venetians, but later Dalmatians, Cretans and Greeks joined in large numbers. Because of the difficulty in hiring sufficient crews, Venice had recourse to conscription, chaining the oarsmen to the benches as other navies had already done. Cristoforo da Canal was the first Venetian to command such a galley. By 1563, the population of Venice had dropped to about 168,000 people.

With the outbreak of another war with the Ottomans in 1570, Venice, Spain and the Pope formed the Holy League, which was able to assemble a grand fleet of 208 galleys, 110 of which were Venetian, under the command of John of Austria, half-brother of Philip II of Spain. The Venetians were commanded by

Difficulties in the rule of the sea brought further changes. Until 1545 the oarsmen in the galleys were free sailors enrolled on a wage. They were originally Venetians, but later Dalmatians, Cretans and Greeks joined in large numbers. Because of the difficulty in hiring sufficient crews, Venice had recourse to conscription, chaining the oarsmen to the benches as other navies had already done. Cristoforo da Canal was the first Venetian to command such a galley. By 1563, the population of Venice had dropped to about 168,000 people.

With the outbreak of another war with the Ottomans in 1570, Venice, Spain and the Pope formed the Holy League, which was able to assemble a grand fleet of 208 galleys, 110 of which were Venetian, under the command of John of Austria, half-brother of Philip II of Spain. The Venetians were commanded by

In 1617, whether on his own initiative, or supported by his king, the Spanish viceroy of Naples attempted to break Venetian dominance by sending a naval squadron to the Adriatic. His expedition met with mixed success, and he retired from the Adriatic. Rumours of sedition and conspiracy were meanwhile circulating in Venice, and there were disturbances between mercenaries of different nationalities enrolled for the war of Gradisca. The Spanish ambassador, the Marquis of Bedmar, was wise to the plot, if not the author of it. Informed of this by a Huguenot captain, the Ten acted promptly. Three "bravos" were hanged, and the Senate demanded the immediate recall of the Spanish ambassador.

Tension with Spain increased in 1622, when

In 1617, whether on his own initiative, or supported by his king, the Spanish viceroy of Naples attempted to break Venetian dominance by sending a naval squadron to the Adriatic. His expedition met with mixed success, and he retired from the Adriatic. Rumours of sedition and conspiracy were meanwhile circulating in Venice, and there were disturbances between mercenaries of different nationalities enrolled for the war of Gradisca. The Spanish ambassador, the Marquis of Bedmar, was wise to the plot, if not the author of it. Informed of this by a Huguenot captain, the Ten acted promptly. Three "bravos" were hanged, and the Senate demanded the immediate recall of the Spanish ambassador.

Tension with Spain increased in 1622, when  War also moved to the mainland in the middle of 1645, when the Turks attacked the frontiers of Dalmatia. In the latter the Venetians were able to save their coastal positions because of their command of the sea, but on 22 August, the Cretan stronghold of

War also moved to the mainland in the middle of 1645, when the Turks attacked the frontiers of Dalmatia. In the latter the Venetians were able to save their coastal positions because of their command of the sea, but on 22 August, the Cretan stronghold of

By 1796, the Republic of Venice could no longer defend itself. Though the Republic still possessed a fleet of 13 ships of the line, only a handful were ready for sea, and the army consisted of only a few brigades of mainly Dalmatian mercenaries. In spring 1796 Piedmont fell and the Austrians were beaten from Montenotte to Lodi. The army under

By 1796, the Republic of Venice could no longer defend itself. Though the Republic still possessed a fleet of 13 ships of the line, only a handful were ready for sea, and the army consisted of only a few brigades of mainly Dalmatian mercenaries. In spring 1796 Piedmont fell and the Austrians were beaten from Montenotte to Lodi. The army under

''Storia di Venezia''

History of Venice

{{DEFAULTSORT:Venice *History of the Republic of Venice Economic history of Italy

The

The Republic of Venice

The Republic of Venice ( vec, Repùblega de Venèsia) or Venetian Republic ( vec, Repùblega Vèneta, links=no), traditionally known as La Serenissima ( en, Most Serene Republic of Venice, italics=yes; vec, Serenìsima Repùblega de Venèsia, ...

( vec, Repùblica Vèneta; it, Repubblica di Venezia) was a sovereign state

A sovereign state or sovereign country, is a political entity represented by one central government that has supreme legitimate authority over territory. International law defines sovereign states as having a permanent population, defined te ...

and maritime republic

The maritime republics ( it, repubbliche marinare), also called merchant republics ( it, repubbliche mercantili), were thalassocratic city-states of the Mediterranean Basin during the Middle Ages. Being a significant presence in Italy in the Mi ...

in Northeast Italy

Northeast Italy ( it, Italia nord-orientale or just ) is one of the five official statistical regions of Italy used by the National Institute of Statistics (ISTAT), a first level NUTS region and a European Parliament constituency. Northeast ...

, which existed for a millennium between the 8th century and 1797.

It was based in the lagoon communities of the historically prosperous city of Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 bridges. The isla ...

, and was a leading European economic and trading power during the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

and the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history

The history of Europe is traditionally divided into four time periods: prehistoric Europe (prior to about 800 BC), classical antiquity (800 BC to AD ...

, the most successful of Italy's maritime republics

The maritime republics ( it, repubbliche marinare), also called merchant republics ( it, repubbliche mercantili), were Thalassocracy, thalassocratic city-states of the Mediterranean Basin during the Middle Ages. Being a significant presence in I ...

. By the late Middle Ages, it held significant territories in the mainland of northern Italy, known as the Domini di Terraferma

The ( vec, domini de terraferma or , ) was the hinterland territories of the Republic of Venice beyond the Adriatic coast in Northeast Italy. They were one of the three subdivisions of the Republic's possessions, the other two being the origi ...

, along with most of the Dalmatian coast on the other side of the Adriatic Sea

The Adriatic Sea () is a body of water separating the Italian Peninsula from the Balkan Peninsula. The Adriatic is the northernmost arm of the Mediterranean Sea, extending from the Strait of Otranto (where it connects to the Ionian Sea) to t ...

, and Crete

Crete ( el, Κρήτη, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cyprus, ...

and numerous small colonies around the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the ...

, together known as the Stato da Màr.

A slow political and economic decline had begun by around 1500, and by the 18th century the city of Venice largely depended on the tourist trade, as it still does, and the Stato da Màr was largely lost.

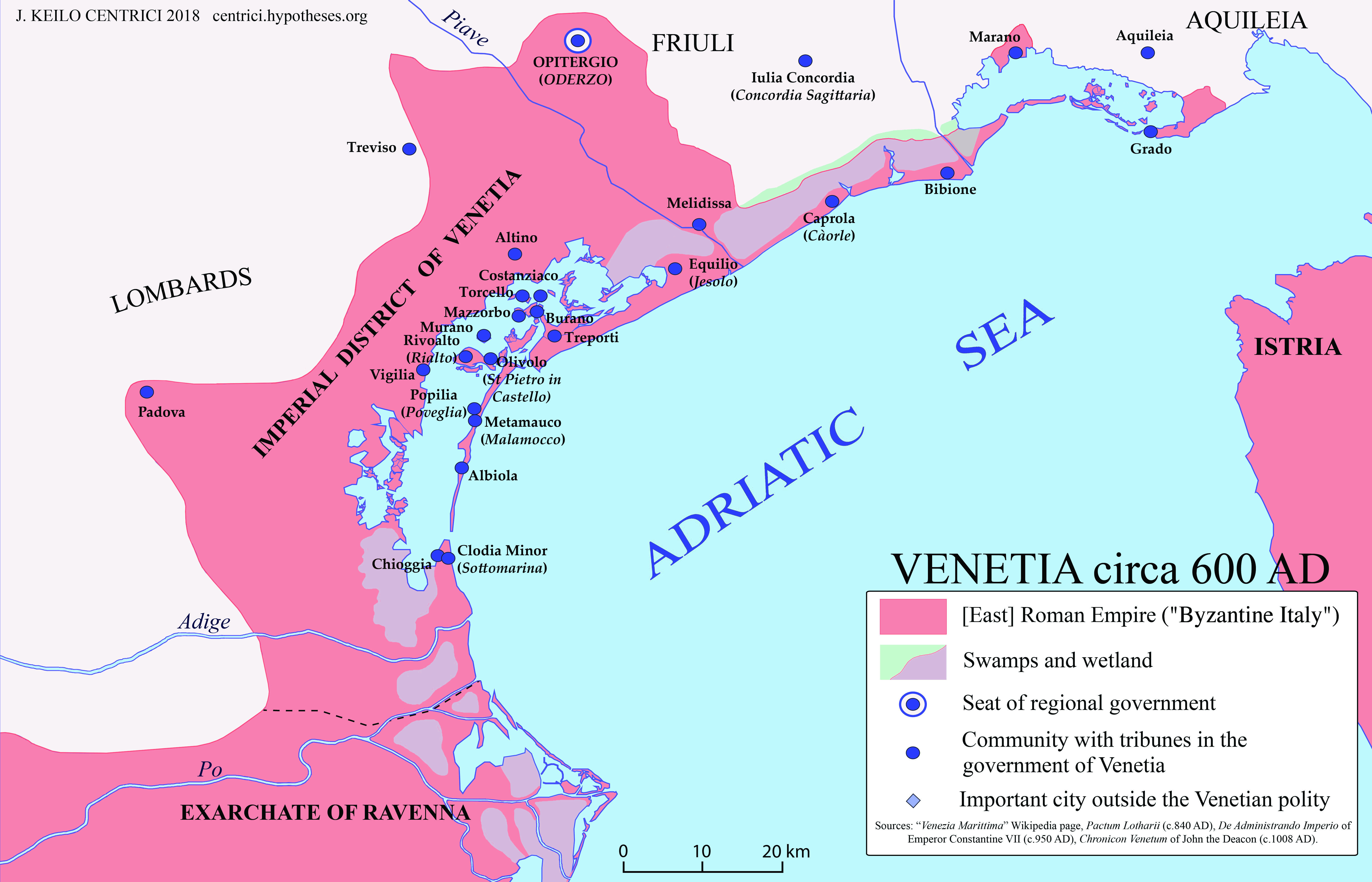

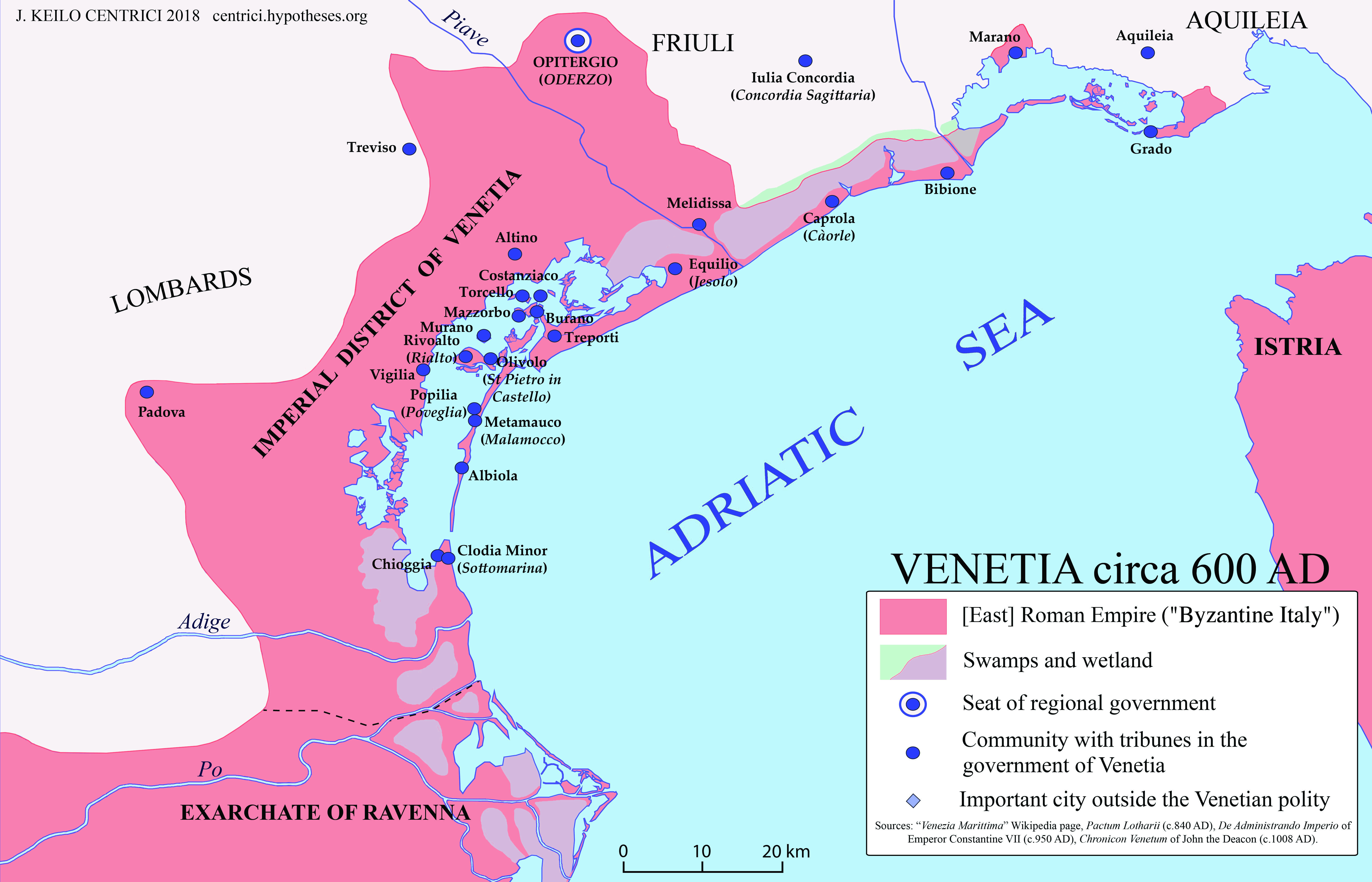

Origins

Although no surviving historical records deal directly with the founding of Venice, the history of the Republic of Venice traditionally begins with the foundation of the city at Noon on Friday, 25 March, AD 421, by authorities fromPadua

Padua ( ; it, Padova ; vec, Pàdova) is a city and ''comune'' in Veneto, northern Italy. Padua is on the river Bacchiglione, west of Venice. It is the capital of the province of Padua. It is also the economic and communications hub of the ...

, to establish a trading-post in that region of northern Italy. The founding of the Venetian republic is also said to have been marked at that same event with the founding of the church of St. James. However, the church (believed to be Saint Giacomo di Rialto) dates back no further than the eleventh century, at the earliest, or the mid-twelfth century, at the latest. The 11th century ''Chronicon Altinate'' also dates the first settlement in that region, Rivo Alto ("High Shore", later Rialto

The Rialto is a central area of Venice, Italy, in the ''sestiere'' of San Polo. It is, and has been for many centuries, the financial and commercial heart of the city. Rialto is known for its prominent markets as well as for the monumental Ria ...

), to the dedication of that same church (i.e., San Giacometo on the bank of the current Grand Canal).

According to tradition, the original population of the region consisted of refugees—from nearby Roman cities such as Padua

Padua ( ; it, Padova ; vec, Pàdova) is a city and ''comune'' in Veneto, northern Italy. Padua is on the river Bacchiglione, west of Venice. It is the capital of the province of Padua. It is also the economic and communications hub of the ...

, Aquileia, Treviso

Treviso ( , ; vec, Trevixo) is a city and '' comune'' in the Veneto region of northern Italy. It is the capital of the province of Treviso and the municipality has 84,669 inhabitants (as of September 2017). Some 3,000 live within the Ven ...

, Altino, and Concordia (modern Concordia Sagittaria

Concordia Sagittaria is a town and ''comune'' in the Metropolitan City of Venice, Veneto, Italy.

History

The town was founded in 42 BC as ''Iulia Concordia'' by the Romans, where the Via Annia and the Via Postumia crossed each other. The establi ...

), as well as from the undefended countryside—who were fleeing successive waves of Hun and Germanic invasions from the mid-second to mid-fifth centuries. This is further supported by documentation on the so-called "apostolic families", the twelve founding families of Venice who elected the first doge, who in most cases traced their lineage back to Roman families.

The Quadi and

The Quadi and Marcomanni

The Marcomanni were a Germanic people

*

*

*

that established a powerful kingdom north of the Danube, somewhere near modern Bohemia, during the peak of power of the nearby Roman Empire. According to Tacitus and Strabo, they were Suebian.

Or ...

destroyed the main Roman town in the area, Opitergium (modern Oderzo

Oderzo ( la, Opitergium; vec, Oderso) is a '' comune'' with a population of 20,003 in the province of Treviso, Veneto, northern Italy.

It lies in the heart of the Venetian plain, about to the northeast of Venice. Oderzo is crossed by the Montic ...

) in AD 166–168. This part of Roman Italy was again overrun in the early 5th century by the Visigoths

The Visigoths (; la, Visigothi, Wisigothi, Vesi, Visi, Wesi, Wisi) were an early Germanic people who, along with the Ostrogoths, constituted the two major political entities of the Goths within the Roman Empire in late antiquity, or what is ...

and by Attila of the Huns who sacked Altinum (a town on the mainland coast of the lagoon of Venice) in 452. The last and most enduring immigration into the north of the Italian peninsula, that of the Lombards

The Lombards () or Langobards ( la, Langobardi) were a Germanic people who ruled most of the Italian Peninsula from 568 to 774.

The medieval Lombard historian Paul the Deacon wrote in the '' History of the Lombards'' (written between 787 an ...

in 568, was the most devastating for the north-eastern region, Venetia (modern Veneto

it, Veneto (man) it, Veneta (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 = ...

and Friuli

Friuli ( fur, Friûl, sl, Furlanija, german: Friaul) is an area of Northeast Italy with its own particular cultural and historical identity containing 1,000,000 Friulians. It comprises the major part of the autonomous region Friuli Venezia Giuli ...

). It also confined the Italian territories of the Eastern Roman Empire to part of central Italy and the coastal lagoons of Venetia, known as the Exarchate of Ravenna

The Exarchate of Ravenna ( la, Exarchatus Ravennatis; el, Εξαρχάτο της Ραβέννας) or of Italy was a lordship of the Eastern Roman Empire (Byzantine Empire) in Italy, from 584 to 751, when the last exarch was put to death by the ...

. Around this time, Cassiodorus

Magnus Aurelius Cassiodorus Senator (c. 485 – c. 585), commonly known as Cassiodorus (), was a Roman statesman, renowned scholar of antiquity, and writer serving in the administration of Theodoric the Great, king of the Ostrogoths. ''Senator'' ...

mentions the ''incolae lacunae'' ("lagoon dwellers"), their fishing and their saltworks and how they strengthened the islands with embankments. The former Opitergium region had finally begun to recover from the various invasions when it was destroyed again, this time for good, by the Lombards

The Lombards () or Langobards ( la, Langobardi) were a Germanic people who ruled most of the Italian Peninsula from 568 to 774.

The medieval Lombard historian Paul the Deacon wrote in the '' History of the Lombards'' (written between 787 an ...

led by Grimoald in 667.

As the power of the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

dwindled in northern Italy in the late 7th century, the lagoon communities came together for mutual defence against the Lombards, as the Duchy of Venetia. The Duchy included the patriarchate

Patriarchate ( grc, πατριαρχεῖον, ''patriarcheîon'') is an ecclesiological term in Christianity, designating the office and jurisdiction of an ecclesiastical patriarch.

According to Christian tradition three patriarchates were est ...

s of Aquileia and Grado

Grado may refer to:

People

* Cristina Grado (1939–2016), Italian film actress

* Jonathan Grado (born 1991), American entrepreneur and photographer

* Francesco De Grado ( fl. 1694–1730), Italian engraver

* Gaetano Grado, Italian mafioso

* ...

, in modern Friuli, by the Lagoon of Grado and Carole, east of that of Venice. Ravenna and the duchy were connected only by sea routes, and with the duchy's isolated position came increasing autonomy. The ''tribuni maiores'' formed the earliest central standing governing committee of the islands in the lagoon - traditionally dated to c. 568.

Early in the 8th century, the people of the lagoon elected their first leader Orso Ipato

Orso Ipato (Latin: ''Ursus Hypatus''; died 737) was the third traditional Doge of Venice (726–737) and the first historically known. During his eleven-year reign, he brought great change to the Venetian navy, aided in the recapture of Ravenn ...

(Ursus), who was confirmed by Byzantium with the titles of '' hypatus'' and ''dux

''Dux'' (; plural: ''ducēs'') is Latin for "leader" (from the noun ''dux, ducis'', "leader, general") and later for duke and its variant forms (doge, duce, etc.). During the Roman Republic and for the first centuries of the Roman Empire, '' ...

''. Historically, Ursus was the first Doge of Venice

The Doge of Venice ( ; vec, Doxe de Venexia ; it, Doge di Venezia ; all derived from Latin ', "military leader"), sometimes translated as Duke (compare the Italian '), was the chief magistrate and leader of the Republic of Venice between 726 ...

. Tradition, however, since the early 11th century, dictates that the Venetians first proclaimed one Paolo Lucio Anafesto

Paolo Lucio Anafesto ( la, Paulucius Anafestus) was, according to tradition, the first Doge of Venice, serving from 697 to 717. He is known for repelling Umayyad attacks.

Biography

A noble of Eraclea, then the primary city of the region, he was ...

(Anafestus Paulicius) duke in AD 697, although the tradition dates only from the chronicle of John, deacon of Venice (John the Deacon); nonetheless, the power base of the first doges was in Eraclea.

Initially, the main settlement was elsewhere in the lagoon and not on the islands of the Rialto group which would later be the heart of Venice. One of the few early settlements attested in the Rialto group was the island of Olivolo (now called S. Pietro in Castello), at the western end of the archipelago, closer to the sandbars of the lagoon. Archaeological excavation shows that this island was already inhabited in the 5th century. 6th and 7th century Byzantine imperial seals indicate that, at this time, it was politically important. There was also a castle, perhaps from the 6th century. John the Deacon's early 11th century ''Chronicon Venetum'' reports that the diocese of Olivolo was founded in 774-76 by the doge Maurizio Galbaio

Maurizio Galbaio (Latin: Mauricius Galba) (died 787) was the seventh traditional, but fifth historical, Doge of Venice from 764 to his death. He was the first great doge, who reigned for 22 years and set Venice on its path to independence and s ...

(764-87), that a bishop Olberio was established in Olivolo by 775 and attributes the foundation of the cathedral of S. Pietro to bishop Orso Partecipazio and its completion to 841. Another attestation of an early settlement in the Rivo Alto group is in what was to become the ''sestriere'' (district) of Cannaregio. Whatever early settlements there were in the Rivo Alto group of islands, which was to form the city of Venice, the area did not begin to become properly urbanised until the 9th century.

Rise

Orso Ipato's successor,Teodato Ipato

Teodato Ipato (also Diodato or Deusdedit; la, Theodatus Hypatus) was Doge of Venice from 742 to 755. With his election came the restoration of the dogato, which had been defunct since the assassination of his father, Orso Ipato. Before his ele ...

, moved his seat from Eraclea to Malamocco (on the Lido) in the 740s. He was the son of Orso and represented the attempt of his father to establish a dynasty. Such attempts were more than commonplace among the doges of the first few centuries of Venetian history, but all were ultimately unsuccessful.

The changing politics of the Frankish Empire

Francia, also called the Kingdom of the Franks ( la, Regnum Francorum), Frankish Kingdom, Frankland or Frankish Empire ( la, Imperium Francorum), was the largest post-Roman barbarian kingdom in Western Europe. It was ruled by the Franks du ...

began to change the factional division of Venice. One faction was decidedly pro-Byzantine. They desired to remain well-connected to the Empire. Another faction, republican in nature, believed in continuing along a course towards practical independence. The other main faction was pro-Frankish. Supported mostly by clergy (in line with papal sympathies of the time), they looked towards the new Carolingian king of the Franks, Pepin the Short, as the best provider of defence against the Lombards. A minor, pro-Lombard, faction was opposed to close ties with any of these further-off powers and interested in maintaining peace with the neighbouring Lombard kingdom, which surrounded Venice except on the seaward side.

Teodato Ipato

Teodato Ipato (also Diodato or Deusdedit; la, Theodatus Hypatus) was Doge of Venice from 742 to 755. With his election came the restoration of the dogato, which had been defunct since the assassination of his father, Orso Ipato. Before his ele ...

was assassinated and his throne usurped, but the usurper, Galla Gaulo

Galla Gaulo or Galla Lupanio was the fifth traditional Doge of Venice (755–756).

History

Gaulo was elected to the throne after deposing and blinding his predecessor, Teodato Ipato. He came to power at a time when there were three clear factio ...

, suffered a like fate within a year. During the reign of his successor, Domenico Monegario

Domenico Monegario was the traditional sixth Doge of Venice (756–764).

History

He was elected with the support of the Lombard king Desiderius. However, in order to maintain necessary good relations with Byzantium and the Franks, two trib ...

, Venice changed from a fisherman's town to a port of trade and centre of merchants. Shipbuilding was also greatly advanced and the pathway to Venetian dominance of the Adriatic was laid. Also during Domenico Monegario

Domenico Monegario was the traditional sixth Doge of Venice (756–764).

History

He was elected with the support of the Lombard king Desiderius. However, in order to maintain necessary good relations with Byzantium and the Franks, two trib ...

's tenure, the first dual tribunal

A tribunal, generally, is any person or institution with authority to judge, adjudicate on, or determine claims or disputes—whether or not it is called a tribunal in its title.

For example, an advocate who appears before a court with a single ...

was instituted. Each year, two new tribunes were elected to oversee the doge and prevent abuse of power.

In that period because, Venice had established itself a thriving slave trade, buying in Italy, among other places, and selling to the Moors in Northern Africa ( Pope Zachary himself reportedly forbade such traffic out of Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

).

The pro-Lombard Monegario was succeeded in 764, by a pro-Byzantine Eraclean, Maurizio Galbaio

Maurizio Galbaio (Latin: Mauricius Galba) (died 787) was the seventh traditional, but fifth historical, Doge of Venice from 764 to his death. He was the first great doge, who reigned for 22 years and set Venice on its path to independence and s ...

. Galbaio's long reign (764-787) vaulted Venice forward to a place of prominence not just regionally but internationally and saw the most concerted effort yet to establish a dynasty. Maurizio oversaw the expansion of Venetia to the Rialto

The Rialto is a central area of Venice, Italy, in the ''sestiere'' of San Polo. It is, and has been for many centuries, the financial and commercial heart of the city. Rialto is known for its prominent markets as well as for the monumental Ria ...

islands. He was succeeded by his equally long-reigning son, Giovanni Giovanni may refer to:

* Giovanni (name), an Italian male given name and surname

* Giovanni (meteorology), a Web interface for users to analyze NASA's gridded data

* ''Don Giovanni'', a 1787 opera by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, based on the legend of ...

. Giovanni clashed with Charlemagne

Charlemagne ( , ) or Charles the Great ( la, Carolus Magnus; german: Karl der Große; 2 April 747 – 28 January 814), a member of the Carolingian dynasty, was King of the Franks from 768, King of the Lombards from 774, and the first ...

over the slave trade and entered into a conflict with the Venetian church.

Dynastic ambitions were shattered when the pro-Frankish faction was able to seize power under Obelerio degli Antoneri in 804. Obelerio brought Venice into the orbit of the Carolingian Empire

The Carolingian Empire (800–888) was a large Frankish-dominated empire in western and central Europe during the Early Middle Ages. It was ruled by the Carolingian dynasty, which had ruled as kings of the Franks since 751 and as kings of the ...

. However, by calling in Charlemagne's son Pepin, '' rex Langobardorum'', to his defence, Obelerio raised the ire of the populace against himself and his family and they were forced to flee during Pepin's siege of Venice.

The siege proved a costly Carolingian failure. It lasted six months, with Pepin's army ravaged by the diseases of the local swamps and eventually forced to withdraw. A few months later Pepin himself died, apparently as a result of a disease contracted there.

Venice thus achieved lasting independence by repelling the besiegers. This was confirmed in an agreement between Charlemagne

Charlemagne ( , ) or Charles the Great ( la, Carolus Magnus; german: Karl der Große; 2 April 747 – 28 January 814), a member of the Carolingian dynasty, was King of the Franks from 768, King of the Lombards from 774, and the first ...

and Nicephorus which recognized Venice as Byzantine territory and also recognized the city's trading rights along the Adriatic coast, where Charlemagne previously ordered the Pope to expel the Venetians from the Pentapolis.

Early Middle Ages

The successors of Obelerio inherited a united Venice. By the '' Pax Nicephori'' (803), the two emperors had recognised Venetian ''de facto'' independence, while it remained nominally Byzantine in subservience. During the reigns ofAgnello Participazio

Agnello Participazio (Latin: Agnellus Particiacus) was the tenth traditional and eighth (historical) doge of the Duchy of Venetia from 811 to 827. He was born to a rich merchant family from Heraclea and was one of the earliest settlers in the R ...

(c. 810-827) and his two sons, Venice grew into its modern form. Around 810, Agnello moved the ducal seat from Malamocco to an island of the Rivo Alto group close to the family's property near the Church of Santi Apostoli, near the eastern bank of the Grand Canal, after Pepin, the Frankish

Frankish may refer to:

* Franks, a Germanic tribe and their culture

** Frankish language or its modern descendants, Franconian languages

* Francia, a post-Roman state in France and Germany

* East Francia, the successor state to Francia in Germany ...

king of Italy, attacked Malamocco but failed to invade the lagoon. This marked the beginning of the urbanisation of the islands of the Rivo Alto group, heart of the modern city of Venice. Agnello's dogeship was marked by the expansion of Venice into the sea through the construction of bridges, canals, bulwarks, fortifications, and stone buildings. The modern Venice, at one with the sea, was being born. Agnello was succeeded by his son Giustiniano, who brought the body of Saint Mark the Evangelist

Mark the Evangelist ( la, Marcus; grc-gre, Μᾶρκος, Mârkos; arc, ܡܪܩܘܣ, translit=Marqōs; Ge'ez: ማርቆስ; ), also known as Saint Mark, is the person who is traditionally ascribed to be the author of the Gospel of Mark. Accor ...

to Venice from Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandri ...

and made him the patron saint of Venice.

During the reign of the successor of the Participazio,

During the reign of the successor of the Participazio, Pietro Tradonico

Pietro Tradonico ( la, Petrus Tradonicus; c. 800 - 13 September 864) was Doge of Venice from 836 to 864. He was, according to tradition, the thirteenth doge, though historically he is only the eleventh. His election broke the power of the Partici ...

, Venice began to establish its military might which would influence many a later crusade and dominate the Adriatic for centuries, and signed a trade agreement with the Holy Roman Emperor Lothair I, whose privileges were later expanded by Otto I

Otto I (23 November 912 – 7 May 973), traditionally known as Otto the Great (german: Otto der Große, it, Ottone il Grande), was East Frankish king from 936 and Holy Roman Emperor from 962 until his death in 973. He was the oldest son of He ...

. Tradonico secured the sea by fighting Narentine

The Narentines were a South Slavic tribe that occupied an area of southern Dalmatia centered at the river Neretva (), active in the 9th and 10th centuries, noted as pirates on the Adriatic. Named ''Narentani'' in Venetian sources, Greek sou ...

and Saracen

upright 1.5, Late 15th-century German woodcut depicting Saracens

Saracen ( ) was a term used in the early centuries, both in Greek and Latin writings, to refer to the people who lived in and near what was designated by the Romans as Arabia Pe ...

pirate

Piracy is an act of robbery or criminal violence by ship or boat-borne attackers upon another ship or a coastal area, typically with the goal of stealing cargo and other valuable goods. Those who conduct acts of piracy are called pirates, v ...

s. Tradonico's reign was long and successful (837 – 864), but he was succeeded by the Participazio and it appeared that a dynasty might finally be established.

In the ''pactum Lotharii

The ''Pactum Lotharii'' was an agreement signed on 23 February 840, between Republic of Venice and the Carolingian Empire, during the respective governments of Pietro Tradonico and Lothair I. This document was one of the first acts to testify to ...

'' of 840 between Venice and the Carolingian Empire

The Carolingian Empire (800–888) was a large Frankish-dominated empire in western and central Europe during the Early Middle Ages. It was ruled by the Carolingian dynasty, which had ruled as kings of the Franks since 751 and as kings of the ...

, Venice promised not to buy Christian slaves in the Empire, and not to sell Christian slaves to Muslims.''Slavery, Slave Trade.'' ed. Strayer, Joseph R. Dictionary of the Middle Ages. Volume 11. New York: Scribner, 1982. Il ''pactum Lotharii'' del 840 Cessi, Roberto. (1939–1940) – In: Atti. Istituto Veneto di Scienze, Lettere ed Arti, Classe di Scienze Morali e Lettere Ser. 2, vol. 99 (1939–40) p. 11–49 The Venetians subsequentently began to sell Slavs and other Eastern European non-Christian slaves in greater numbers. Caravans of slaves traveled from Eastern Europe, through Alpine passes in Austria, to reach Venice. Surviving records valued female slaves at a '' tremissa'' (about 1.5 grams of gold or roughly of a dinar) and male slaves, who were more numerous, at a ''saiga'' (which is much less).MGH, Leges, Capitularia regum Francorum, II, ed. by A. Boretius, Hanovre, 1890, p. 250–25(available on-line)

Eunuch

A eunuch ( ) is a male who has been castrated. Throughout history, castration often served a specific social function.

The earliest records for intentional castration to produce eunuchs are from the Sumerian city of Lagash in the 2nd millenni ...

s were especially valuable, and "castration houses" arose in Venice, as well as other prominent slave markets, to meet this demand.Jankowiak, Marek. Dirhams for slaves. Investigating the Slavic slave trade in the tenth centurAround 841, the

Republic of Venice

The Republic of Venice ( vec, Repùblega de Venèsia) or Venetian Republic ( vec, Repùblega Vèneta, links=no), traditionally known as La Serenissima ( en, Most Serene Republic of Venice, italics=yes; vec, Serenìsima Repùblega de Venèsia, ...

sent a fleet of 60 galleys (each carrying 200 men) to assist the Byzantines in driving the Arabs

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Western Asia, ...

from Crotone, but failed.

Under Pietro II Candiano

Pietro II Candiano ( – 939) was the nineteenth Doge of Venice between 932 and 939. He followed Orso II Participazio (912–932) to become Doge in 932.

Career

The Candiano family was the most important family of Venice during the tenth century. ...

, Istrian cities signed an act of devotion to the Venetian rule. His father (Pietro Candiano I) attempted to attack and destroy Marania or Pagania or Narentines and secure safe passage to Venetian fleets and treaders near Croatian Dalmatia . On 887 September 18, Candiano was captured by the Admiral of the Maranium Navy and killed. He was the first and only Duke of Venice to lose his life in an attempt to secure the Dalmatian Coast to Venice. The autocratic, philo-Imperial Candiano dynasty was overthrown by a revolt in 972, and the populace elected doge Pietro I Orseolo

Pietro I Orseolo OSBCam, also named ''Peter Urseulus'', (928–987) was the Doge of Venice from 976 until 978. He abdicated his office and left in the middle of the night to become a monk. He later entered the order of the Camaldolese Hermits of ...

; however, his conciliating policy was ineffective, and he resigned in favour of Vitale Candiano

Vitale Candiano (died 979) was the 24th doge of the Republic of Venice.

Biography

He was the fourth son of the 21st doge, Pietro III Candiano, and Arcielda Candiano (sometimes given as Richielda). His brother the 22nd Doge Pietro IV and his y ...

.

Starting from Pietro II Orseolo

Pietro II Orseolo (961−1009) was the Doge of Venice from 991 to 1009.

He began the period of eastern expansion of Venice that lasted for the better part of 500 years. He secured his influence in the Dalmatian Romanized settlements from the Croa ...

, who reigned from 991, attention towards the mainland was definitely overshadowed by a strong push towards control of Adriatic Sea. Inner strife was pacified, and trade with the Byzantine Empire boosted by the favourable treaty (''Grisobolus'' or Golden Bull

A golden bull or chrysobull was a decree issued by Byzantine Emperors and later by monarchs in Europe during the Middle Ages and Renaissance, most notably by the Holy Roman Emperors. The term was originally coined for the golden seal (a ''bull ...

) with Emperor Basil II

Basil II Porphyrogenitus ( gr, Βασίλειος Πορφυρογέννητος ;) and, most often, the Purple-born ( gr, ὁ πορφυρογέννητος, translit=ho porphyrogennetos).. 958 – 15 December 1025), nicknamed the Bulgar S ...

. The imperial edict granted Venetian traders freedom from taxation paid by other foreigners and the Byzantines themselves.

On Ascension Day in 1000 a powerful fleet sailed from Venice to resolve the problem of the Narentine pirates. The fleet visited all the main Istrian and Dalmatian cities, whose citizens, exhausted by the wars between the Croatian king Svetislav and his brother Cresimir, swore an oath of fidelity to Venice. the Main Narentine harbours ( Lagosta, Lissa and Curzola) tried to resist, but they were conquered and destroyed (see: battle of Lastovo). The Narentine pirates were suppressed permanently and disappeared. Dalmatia formally remained under Byzantine rule, but Orseolo became "Dux Dalmatie" (Duke of Dalmatia"), establishing the prominence of Venice over the Adriatic Sea. The " Marriage of the Sea" ceremony was established in this period. Orseolo died in 1008.

Venice's control over the Adriatic was strengthened by an expedition by Pietro's son Ottone

''Ottone, re di Germania'' ("Otto, King of Germany", HWV 15) is an opera by George Frideric Handel, to an Italian–language libretto adapted by Nicola Francesco Haym from the libretto by Stefano Benedetto Pallavicino for Antonio Lotti's opera ...

in 1017, by which time Venice had assumed a key role in balancing power between the Byzantine and Holy Roman Empires.

During the long Investiture Controversy

The Investiture Controversy, also called Investiture Contest ( German: ''Investiturstreit''; ), was a conflict between the Church and the state in medieval Europe over the ability to choose and install bishops ( investiture) and abbots of mona ...

, an 11th-century dispute between Henry IV, Holy Roman Emperor

Henry IV (german: Heinrich IV; 11 November 1050 – 7 August 1106) was Holy Roman Emperor from 1084 to 1105, King of Germany from 1054 to 1105, King of Italy and Burgundy from 1056 to 1105, and Duke of Bavaria from 1052 to 1054. He was the so ...

and Pope Gregory VII over who would control appointments of church officials, Venice remained neutral, and this caused some attrition of support from the Popes. Doge Domenico Selvo

Domenico Selvo (died 1087) was the 31st Doge of Venice, serving from 1071 to 1084. During his reign as Doge, his domestic policies, the alliances that he forged, and the battles that the Venetian military won and lost laid the foundations for m ...

intervened in the war between the Normans

The Normans ( Norman: ''Normaunds''; french: Normands; la, Nortmanni/Normanni) were a population arising in the medieval Duchy of Normandy from the intermingling between Norse Viking settlers and indigenous West Franks and Gallo-Romans. ...

of Apulia and the Byzantine Emperor Alexios I Komnenos

Alexios I Komnenos ( grc-gre, Ἀλέξιος Κομνηνός, 1057 – 15 August 1118; Latinized Alexius I Comnenus) was Byzantine emperor from 1081 to 1118. Although he was not the first emperor of the Komnenian dynasty, it was during ...

in favour of the latter, obtaining in exchange a bull declaring the Venetian supremacy in the Adriatic coast up to Durazzo, as well as ''the exemption from taxes for his merchants in the whole Byzantine Empire'', a considerable factor in the city-state's later accumulation of wealth and power serving as middlemen for the lucrative spice

A spice is a seed, fruit, root, bark, or other plant substance primarily used for flavoring or coloring food. Spices are distinguished from herbs, which are the leaves, flowers, or stems of plants used for flavoring or as a garnish. Spice ...

and silk trade

The Silk Road () was a network of Eurasian trade routes active from the second century BCE until the mid-15th century. Spanning over 6,400 kilometers (4,000 miles), it played a central role in facilitating economic, cultural, political, and rel ...

that funnelled through the Levant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is ...

and Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Medit ...

along the ancient Kingdom of Axum

The Kingdom of Aksum ( gez, መንግሥተ አክሱም, ), also known as the Kingdom of Axum or the Aksumite Empire, was a kingdom centered in Northeast Africa and South Arabia from Classical antiquity to the Middle Ages. Based primarily in wh ...

and Roman-Indian routes via the Red Sea

The Red Sea ( ar, البحر الأحمر - بحر القلزم, translit=Modern: al-Baḥr al-ʾAḥmar, Medieval: Baḥr al-Qulzum; or ; Coptic: ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϩⲁϩ ''Phiom Enhah'' or ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϣⲁⲣⲓ ''Phiom ǹšari''; ...

.

The war was not a military success, but with that act the city gained total independence. In 1084, Domenico Selvo

Domenico Selvo (died 1087) was the 31st Doge of Venice, serving from 1071 to 1084. During his reign as Doge, his domestic policies, the alliances that he forged, and the battles that the Venetian military won and lost laid the foundations for m ...

led a fleet against the Normans

The Normans ( Norman: ''Normaunds''; french: Normands; la, Nortmanni/Normanni) were a population arising in the medieval Duchy of Normandy from the intermingling between Norse Viking settlers and indigenous West Franks and Gallo-Romans. ...

, but he was defeated and lost 9 great galleys, the largest and most heavily armed ships in the Venetian navy.

High Middle Ages

In the

In the High Middle Ages

The High Middle Ages, or High Medieval Period, was the period of European history that lasted from AD 1000 to 1300. The High Middle Ages were preceded by the Early Middle Ages and were followed by the Late Middle Ages, which ended around AD 150 ...

, Venice became wealthy through its control of trade between Europe and the Levant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is ...

, and began to expand into the Adriatic Sea

The Adriatic Sea () is a body of water separating the Italian Peninsula from the Balkan Peninsula. The Adriatic is the northernmost arm of the Mediterranean Sea, extending from the Strait of Otranto (where it connects to the Ionian Sea) to t ...

and beyond. Venice was involved in the Crusades almost from the very beginning; 200 Venetian ships assisted in capturing the coastal cities of Syria after the First Crusade

The First Crusade (1096–1099) was the first of a series of religious wars, or Crusades, initiated, supported and at times directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The objective was the recovery of the Holy Land from Islamic r ...

, and in 1123 they were granted virtual autonomy in the Kingdom of Jerusalem

The Kingdom of Jerusalem ( la, Regnum Hierosolymitanum; fro, Roiaume de Jherusalem), officially known as the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem or the Frankish Kingdom of Palestine,Example (title of works): was a Crusader state that was establish ...

through the ''Pactum Warmundi

The Pactum Warmundi was a treaty of alliance established in 1123 between the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem and the Republic of Venice.

Background

In 1123, King Baldwin II was taken prisoner by the Artuqids, and the Kingdom of Jerusalem was sub ...

''. In 1110, Ordelafo Faliero

Ordelafo Faliero de Doni (or Dodoni) (died 1117 in Zadar, Kingdom of Hungary) was the 34th Doge of Venice.

Biography

He was the son of the 32nd Doge, Vitale Faliero de' Doni. He was a member of the Minor Council (''minor consiglio''), an asse ...

personally commanded a Venetian fleet of 100 ships to assist Baldwin I of Jerusalem

Baldwin I, also known as Baldwin of Boulogne (1060s – 2April 1118), was the first count of Edessa from 1098 to 1100, and king of Jerusalem from 1100 to his death in 1118. He was the youngest son of Eustace II, Count of Boulogne, and Ida of Lor ...

in capturing the city of Sidon

Sidon ( ; he, צִידוֹן, ''Ṣīḏōn'') known locally as Sayda or Saida ( ar, صيدا ''Ṣaydā''), is the third-largest city in Lebanon. It is located in the South Governorate, of which it is the capital, on the Mediterranean coast. ...

.

In the 12th century, the republic built a large national shipyard that is now known as the Venetian Arsenal

The Venetian Arsenal ( it, Arsenale di Venezia) is a complex of former shipyards and armories clustered together in the city of Venice in northern Italy. Owned by the state, the Arsenal was responsible for the bulk of the Venetian republic's ...

. Building new and powerful fleets, the republic took control over the eastern Mediterranean. The first exchange business in the world was started in Venezia, to support merchants from all over Europe. The Venetians also gained extensive trading privileges in the Byzantine Empire, and their ships often provided the Empire with a navy. In 1182 there was an anti-Catholic massacre by the Orthodox Christian population of Constantinople, with the Venetians as the main targets.

The rise of Venetian power

Venice was asked to provide transportation for the Fourth Crusade, but when the crusaders could not pay for chartering their shipping, the doge

Venice was asked to provide transportation for the Fourth Crusade, but when the crusaders could not pay for chartering their shipping, the doge Enrico Dandolo

Enrico Dandolo (anglicised as Henry Dandolo and Latinized as Henricus Dandulus; c. 1107 – May/June 1205) was the Doge of Venice from 1192 until his death. He is remembered for his avowed piety, longevity, and shrewdness, and is known for his r ...

offered to delay the payment in exchange for their aid in recapturing Zara (today ''Zadar

Zadar ( , ; historically known as Zara (from Venetian and Italian: ); see also other names), is the oldest continuously inhabited Croatian city. It is situated on the Adriatic Sea, at the northwestern part of Ravni Kotari region. Zadar ser ...

''), which had rebelled against Venetian rule in 1183, placing itself under the dual protection of the Papacy and King Emeric of Hungary

Emeric, also known as Henry or Imre ( hu, Imre, hr, Emerik, sk, Imrich; 117430 November 1204), was King of Hungary and Croatia between 1196 and 1204. In 1184, his father, Béla III of Hungary, ordered that he be crowned king, and appointed him ...

, and had proved too well fortified for Venice to retake alone.

Upon accomplishing this in 1202, the crusade was again diverted to Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya ( Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis ( ...

, the capital of the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

. After being deposed from power, Alexios IV Angelos

Alexios IV Angelos or Alexius IV Angelus ( el, Ἀλέξιος Ἄγγελος) (c. 1182 – February 1204) was Byzantine Emperor from August 1203 to January 1204. He was the son of Emperor Isaac II Angelos and his first wife, an unknown Palaio ...

offered to the Crusaders 10,000 Byzantine soldiers to help fight in the Crusade, maintain 500 knights in the Holy Land, the service of the Byzantine navy (20 ships) in transporting their army to Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Medit ...

, and 200,000 silver marks to help pay off the Crusaders' debt to Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 bridges. The isla ...

if the Crusaders helped re-install him as emperor.

The Crusaders agreed and restored Alexios to power in 1203; however, he refused to hold up his end of the bargain. The Venetians and French crusaders responded by commencing a siege of Constantinople and in 1204, they captured and sacked the city. Venetians saved from the sack several artistic works, such as the famous four bronze horses and brought them back to Venice.

Byzantine hegemony was destroyed, and in the partition of the Empire that followed, Venice gained strategic territories in the Aegean Sea

The Aegean Sea ; tr, Ege Denizi (Greek: Αιγαίο Πέλαγος: "Egéo Pélagos", Turkish: "Ege Denizi" or "Adalar Denizi") is an elongated embayment of the Mediterranean Sea between Europe and Asia. It is located between the Balkans ...

(three-eighths of the Byzantine Empire), including the islands of Crete

Crete ( el, Κρήτη, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cyprus, ...

and Euboea

Evia (, ; el, Εύβοια ; grc, Εὔβοια ) or Euboia (, ) is the second-largest Greek island in area and population, after Crete. It is separated from Boeotia in mainland Greece by the narrow Euripus Strait (only at its narrowest poin ...

. Moreover, some present day cities, such as Chania

Chania ( el, Χανιά ; vec, La Canea), also spelled Hania, is a city in Greece and the capital of the Chania regional unit. It lies along the north west coast of the island Crete, about west of Rethymno and west of Heraklion.

The muni ...

on Crete, have core architecture

Architecture is the art and technique of designing and building, as distinguished from the skills associated with construction. It is both the process and the product of sketching, conceiving, planning, designing, and constructing building ...

that is substantially Venetian in origin. The Aegean islands formed the Venetian Duchy of the Archipelago.

The Republic of Venice signed a trade treaty with the Mongol Empire in 1241.

In 1295, Pietro Gradenigo

Pietro Gradenigo (1251 – 13 August 1311) was the 49th Doge of Venice, reigning from 1289 to his death.

When he was elected Doge, he was serving as the podestà of Capodistria in Istria. Venice suffered a serious blow with the fall of Acre, ...

sent a fleet of 68 ships to attack a Genoese fleet at Alexandretta, then another fleet of 100 ships were sent to attack the Genoese in 1299. In 1304, Venice fought a brief Salt War with Padua.

In the 14th century, Venice faced difficulties to the east, especially during the reign of Louis I of Hungary. In 1346 he made a first attempt to free Zara from Venetian suzerainty, but was defeated. In 1356 an alliance was formed by the counts of Gorizia, Francesco I da Carrara Francesco I da Carrara (29 September 1325, in Monza – 6 October 1393, in Padua), called il Vecchio, was Lord of Padua from 1350 to 1388.

The son of the assassinated Giacomo II da Carrara, he succeeded him as lord of Padua by popular acclamation ...

, lord of Padua

Padua ( ; it, Padova ; vec, Pàdova) is a city and ''comune'' in Veneto, northern Italy. Padua is on the river Bacchiglione, west of Venice. It is the capital of the province of Padua. It is also the economic and communications hub of the ...

, Nicolaus, patriarch of Aquileia and his half brother emperor Charles IV

Charles IV ( cs, Karel IV.; german: Karl IV.; la, Carolus IV; 14 May 1316 – 29 November 1378''Karl IV''. In: (1960): ''Geschichte in Gestalten'' (''History in figures''), vol. 2: ''F–K''. 38, Frankfurt 1963, p. 294), also known as Charle ...

, Louis I, and the dukes of Austria. The league's troops occupied Grado

Grado may refer to:

People

* Cristina Grado (1939–2016), Italian film actress

* Jonathan Grado (born 1991), American entrepreneur and photographer

* Francesco De Grado ( fl. 1694–1730), Italian engraver

* Gaetano Grado, Italian mafioso

* ...

and Muggia

Muggia ( vec, label=Venetian, Triestine dialect, Muja; german: Mulgs; fur, Mugle; sl, Milje) is an Italian town and ''comune'' in the south-west of the Province of Trieste, in the region of Friuli-Venezia Giulia on the border with Slovenia. Lying ...

(1356), while Louis stripped Venice of Dalmatia.

Along the Dalmatian coast, his army had attacked the Dalmatian cities of Zara, Traù, Spalato

)''

, settlement_type = City

, anthem = ''Marjane, Marjane''

, image_skyline =

, imagesize = 267px

, image_caption = Top: Nighttime view of Split from Mosor; 2nd row: Cathedra ...

and Ragusa. The siege of Treviso

Treviso ( , ; vec, Trevixo) is a city and '' comune'' in the Veneto region of northern Italy. It is the capital of the province of Treviso and the municipality has 84,669 inhabitants (as of September 2017). Some 3,000 live within the Ven ...

(July–September 1356) was a failure. Venice suffered a severe defeat at Nervesa (13 January 1358), being forced to withdraw from Dalmatia and give it again to the Kingdom of Hungary

The Kingdom of Hungary was a monarchy in Central Europe that existed for nearly a millennium, from the Middle Ages into the 20th century. The Principality of Hungary emerged as a Christian kingdom upon the coronation of the first king Stephen ...

. Venetians resigned themselves to the unfavorable conditions stipulated in the Treaty of Zara, which was signed on February 18, 1358.

From 1350 to 1381, Venice also fought an intermittent war with the Genoese. Initially defeated, the Venetians destroyed the Genoese fleet at the Battle of Chioggia

The Battle of Chioggia was a naval battle during the War of Chioggia that culminated on June 24, 1380 in the lagoon off Chioggia, Italy, between the Republic of Venice, Venetian and the Republic of Genoa, Genoese fleets."Carlo Zeno". Encyclopædia ...

in 1380 and retained their prominent position in eastern Mediterranean affairs at the expense of Genoa. However, the peace caused Venice to lose several territories to other participants to the war: Conegliano

Conegliano (; Venetian: ''Conejan'') is a town and ''comune'' of the Veneto region, Italy, in the province of Treviso, about north by rail from the town of Treviso. The population of the city is of people. The remains of a 10th-century castle a ...

was occupied by the Austrians

, pop = 8–8.5 million

, regions = 7,427,759

, region1 =

, pop1 = 684,184

, ref1 =

, region2 =

, pop2 = 345,620

, ref2 =

, region3 =

, pop3 = 197,990

, ref3 ...

; Treviso

Treviso ( , ; vec, Trevixo) is a city and '' comune'' in the Veneto region of northern Italy. It is the capital of the province of Treviso and the municipality has 84,669 inhabitants (as of September 2017). Some 3,000 live within the Ven ...

was taken over by Carraresi

The House of Carrara or Carraresi (da Carrara) was an important family of northern Italy in the 12th to 15th centuries. The family held the title of Lords of Padua from 1318 to 1405.

Under their rule, Padua conquered Verona, Vicenza, Treviso, F ...

; Tenedos

Tenedos (, ''Tenedhos'', ), or Bozcaada in Turkish, is an island of Turkey in the northeastern part of the Aegean Sea. Administratively, the island constitutes the Bozcaada district of Çanakkale Province. With an area of it is the third l ...

fell to the Byzantine Empire; Trieste fell to the Patriarchate of Aquileia

The Patriarchate of Aquileia was an episcopal see in northeastern Italy, centred on the ancient city of Aquileia situated at the head of the Adriatic, on what is now the Italian seacoast. For many centuries it played an important part in histor ...

; and the Serenissima lost control of Dalmatia to Hungary.

In 1363, a colonial revolt broke out in Crete that needed considerable military force and five years to suppress.

15th century

In the early 15th century, the Venetians further expanded their possessions in Northern Italy, and assumed the definitive control of the Dalmatian coast, which was acquired from

In the early 15th century, the Venetians further expanded their possessions in Northern Italy, and assumed the definitive control of the Dalmatian coast, which was acquired from Ladislaus of Naples

Ladislaus the Magnanimous ( it, Ladislao, hu, László; 15 February 1377 – 6 August 1414) was King of Naples from 1386 until his death and an unsuccessful claimant to the kingdoms of Hungary and Croatia. Ladislaus was a skilled political and m ...

. Venice installed its own noblemen to govern the area, for example, Count Filippo Stipanov in Zara. This move by the Venetians was in response to the threatened expansion of Giangaleazzo Visconti

Gian Galeazzo Visconti (16 October 1351 – 3 September 1402), was the first duke of Milan (1395) and ruled the late-medieval city just before the dawn of the Renaissance. He also ruled Lombardy jointly with his uncle Bernabò. He was the foundi ...

, Duke of Milan

Milan ( , , Lombard: ; it, Milano ) is a city in northern Italy, capital of Lombardy, and the second-most populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of about 1.4 million, while its metropolitan city h ...

. Control over the north-east cross-country routes was also needed to ensure the safety of travelling merchants. By 1410, Venice had a navy of some 3,300 ships (manned by 36,000 men) and had taken over most of Venetia, including such important cities as Verona

Verona ( , ; vec, Verona or ) is a city on the Adige River in Veneto, Italy, with 258,031 inhabitants. It is one of the seven provincial capitals of the region. It is the largest city municipality in the region and the second largest in nor ...

and Padua

Padua ( ; it, Padova ; vec, Pàdova) is a city and ''comune'' in Veneto, northern Italy. Padua is on the river Bacchiglione, west of Venice. It is the capital of the province of Padua. It is also the economic and communications hub of the ...

.

The situation in Dalmatia was settled in 1408 by a truce with Sigismund of Hungary

Sigismund of Luxembourg (15 February 1368 – 9 December 1437) was a monarch as King of Hungary and Croatia (''jure uxoris'') from 1387, King of Germany from 1410, King of Bohemia from 1419, and Holy Roman Emperor from 1433 until his death in 1 ...

. When this expired, Venice immediately invaded the Patriarchate of Aquileia, and subjugated Traù, Spalato

)''

, settlement_type = City

, anthem = ''Marjane, Marjane''

, image_skyline =

, imagesize = 267px

, image_caption = Top: Nighttime view of Split from Mosor; 2nd row: Cathedra ...

, Durazzo, and other Dalmatian cities. The difficulties of Hungary allowed the Republic to consolidate its Adriatic dominions.

Under doge Francesco Foscari

Francesco Foscari (19 June 1373 – 1 November 1457) was the 65th Doge of the Republic of Venice from 1423 to 1457. His reign, the longest of all Doges in Venetian history, lasted 34 years, 6 months and 8 days, and coincided with the inception o ...

(1423–57) the city reached the height of its power and territorial extent. In 1425 a new war broke out, this time against Filippo Maria Visconti of Milan. The victory at the Battle of Maclodio

The Battle of Maclodio was fought on 11 October 1427, resulting in a victory for the Venetians under Carmagnola over the Milanese under Carlo I Malatesta. The battle was fought at Maclodio (or Macalo), a small town near the River Oglio, fifte ...

of Count of Carmagnola, commander of the Venetian army, resulted in the shift of the western border from the Adige to the Adda. However, such territorial expansion was not welcome everywhere in Venice; tension with Milan remained high, and in 1446 the Republic had to fight another alliance, formed by Milan, Florence, Bologna, and Cremona. After an initial Venetian victory under Micheletto Attendolo

Micheletto Attendolo, also called Micheletto da Cotignola, (c. 1370 – February 1463) was an Italian condottiero. He was seigneur of Acquapendente, Potenza, Alianello, Castelfranco Veneto and Pozzolo Formigaro.

Born in Cotignola, he was ...

at Casalmaggiore, however, Visconti died and a republic was declared in Milan. The Serenissima had then a free hand to occupy Lodi and Piacenza

Piacenza (; egl, label= Piacentino, Piaṡëinsa ; ) is a city and in the Emilia-Romagna region of northern Italy, and the capital of the eponymous province. As of 2022, Piacenza is the ninth largest city in the region by population, with over ...

, but was halted by Francesco Sforza

Francesco I Sforza (; 23 July 1401 – 8 March 1466) was an Italian condottiero who founded the Sforza dynasty in the duchy of Milan, ruling as its (fourth) duke from 1450 until his death. In the 1420s, he participated in the War of L'A ...

; later, Sforza and the Doge allied to allow Sforza the rule of Milan, in exchange for the cession of Brescia

Brescia (, locally ; lmo, link=no, label= Lombard, Brèsa ; lat, Brixia; vec, Bressa) is a city and ''comune'' in the region of Lombardy, Northern Italy. It is situated at the foot of the Alps, a few kilometers from the lakes Garda and Iseo ...

and Vicenza

Vicenza ( , ; ) is a city in northeastern Italy. It is in the Veneto region at the northern base of the ''Monte Berico'', where it straddles the Bacchiglione River. Vicenza is approximately west of Venice and east of Milan.

Vicenza is a thr ...

. Venice, however, again changed side when the power of Sforza seemed to become excessive: the intricate situation was settled with the Peace of Lodi

Peace is a concept of societal friendship and harmony in the absence of hostility and violence. In a social sense, peace is commonly used to mean a lack of conflict (such as war) and freedom from fear of violence between individuals or groups. ...

(1454), which confirmed the area of Bergamo and Brescia to the Republic. At this time, the territories under the Serenissima included much of the modern Veneto

it, Veneto (man) it, Veneta (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 = ...

, Friuli

Friuli ( fur, Friûl, sl, Furlanija, german: Friaul) is an area of Northeast Italy with its own particular cultural and historical identity containing 1,000,000 Friulians. It comprises the major part of the autonomous region Friuli Venezia Giuli ...

, the provinces of Bergamo, Cremona and Trento, as well as Ravenna

Ravenna ( , , also ; rgn, Ravèna) is the capital city of the Province of Ravenna, in the Emilia-Romagna region of Northern Italy. It was the capital city of the Western Roman Empire from 408 until its collapse in 476. It then served as the ca ...

, Istria, and Dalmatia. Eastern borders were with the county of Gorizia

The County of Gorizia ( it, Contea di Gorizia, german: Grafschaft Görz, sl, Goriška grofija, fur, Contee di Gurize), from 1365 Princely County of Gorizia, was a State of the Holy Roman Empire. Originally mediate ''Vogts'' of the Patriarchs of ...

and the ducal lands of Austria, while in the south was the Duchy of Ferrara

The Duchy of Ferrara ( la, Ducatus Ferrariensis; it, Ducato di Ferrara; egl, Ducà ad Frara) was a state in what is now northern Italy. It consisted of about 1,100 km2 south of the lower Po River, stretching to the valley of the lower Reno ...

. Oversea dominions included Euboea

Evia (, ; el, Εύβοια ; grc, Εὔβοια ) or Euboia (, ) is the second-largest Greek island in area and population, after Crete. It is separated from Boeotia in mainland Greece by the narrow Euripus Strait (only at its narrowest poin ...

and Egina

Aegina (; el, Αίγινα, ''Aígina'' ; grc, Αἴγῑνα) is one of the Saronic Islands of Greece in the Saronic Gulf, from Athens. Tradition derives the name from Aegina, the mother of the hero Aeacus, who was born on the island and b ...

.

Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya ( Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis ( ...

fell to the Ottomans, but Venice managed to maintain a colony in the city and some of the former trade privileges it had had under the Byzantines. Indeed, in 1454, the Ottomans granted the Venetians their ports and trading rights. Despite the recent Ottoman defeats by John Hunyadi

John Hunyadi (, , , ; 1406 – 11 August 1456) was a leading Hungarian military and political figure in Central and Southeastern Europe during the 15th century. According to most contemporary sources, he was the member of a noble family of ...

of Hungary and by Skanderbeg

, reign = 28 November 1443 – 17 January 1468

, predecessor = Gjon Kastrioti

, successor = Gjon Kastrioti II

, spouse = Donika Arianiti

, issue = Gjon Kastrioti II

, royal house = Kastrioti

, father ...

in Albania, war was unavoidable. In 1463 the Venetian fortress of Argos

Argos most often refers to:

* Argos, Peloponnese, a city in Argolis, Greece

** Ancient Argos, the ancient city

* Argos (retailer), a catalogue retailer operating in the United Kingdom and Ireland

Argos or ARGOS may also refer to:

Businesses

...

was ravaged. Venice set up an alliance with Matthias Corvinus of Hungary

Matthias Corvinus, also called Matthias I ( hu, Hunyadi Mátyás, ro, Matia/Matei Corvin, hr, Matija/Matijaš Korvin, sk, Matej Korvín, cz, Matyáš Korvín; ), was King of Hungary and Croatia from 1458 to 1490. After conducting several m ...

and attacked the Greek islands by sea and Bulgaria by land. The allies were forced to retreat on both fronts, however, after several minor victories. Operations were reduced mostly to isolated ravages and guerrilla attacks, until the Ottomans moved on a massive counteroffensive in 1470: this resulted in Venice losing its main stronghold in the Aegean Sea, Negroponte. The Venetians sought an alliance with the Shah of Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

and other European powers, but, receiving only limited support, could make only small-scale attacks at Antalya

la, Attalensis grc, Ἀτταλειώτης

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code = 07xxx

, area_code = (+90) 242

, registration_plate = 07

, blank_name = Licence plate

...

, Halicarnassus

Halicarnassus (; grc, Ἁλικαρνᾱσσός ''Halikarnāssós'' or ''Alikarnāssós''; tr, Halikarnas; Carian: 𐊠𐊣𐊫𐊰 𐊴𐊠𐊥𐊵𐊫𐊰 ''alos k̂arnos'') was an ancient Greek city in Caria, in Anatolia. It was located i ...

and Smirne.

The Ottomans conquered the Peloponnesus and launched an offensive in the Venetian mainland, closing in on the important centre of Udine

Udine ( , ; fur, Udin; la, Utinum) is a city and ''comune'' in north-eastern Italy, in the middle of the Friuli Venezia Giulia region, between the Adriatic Sea and the Alps (''Alpi Carniche''). Its population was 100,514 in 2012, 176,000 with t ...

. The Persians, together with the Caramanian amir, were severely defeated at Terdguin, and the Republic was left alone. Further, much of Albania was lost after Skanderbeg's death. However, the heroic resistance of Scutari under Antonio Loredan forced the Ottomans to retire from Albania, while a revolt in Cyprus

Cyprus ; tr, Kıbrıs (), officially the Republic of Cyprus,, , lit: Republic of Cyprus is an island country located south of the Anatolian Peninsula in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Its continental position is disputed; while it is ge ...

gave back the island to the Cornaro family and, subsequently, to the Serenissima (1473). Its prestige seemed reassured, but Scutari fell anyway two years later, and Friuli was again invaded and ravaged. On January 24, 1479, a treaty of peace was finally signed with the Ottomans. Venice had to cede Argo, Negroponte, Lemnos

Lemnos or Limnos ( el, Λήμνος; grc, Λῆμνος) is a Greek island in the northern Aegean Sea. Administratively the island forms a separate municipality within the Lemnos regional unit, which is part of the North Aegean region. The p ...

and Scutari, and pay an annual tribute of 10,000 golden '' ducati''. Five years later the agreement was confirmed by Mehmed II's successor, Bayezid II, with the peaceful exchange of the islands of Zakynthos

Zakynthos (also spelled Zakinthos; el, Ζάκυνθος, Zákynthos ; it, Zacinto ) or Zante (, , ; el, Τζάντε, Tzánte ; from the Venetian form) is a Greek island in the Ionian Sea. It is the third largest of the Ionian Islands. Z ...

and Kefalonia between the two sides.

In 1482 Venice allied with Pope Sixtus IV in his attempt to conquer Ferrara, opposed to Florence, Naples, Milan, and Ercole d'Este. When Papal-Venetian milices were smashed at the Battle of Campomorto, Sixtus changed side. Again alone, the Venetians were defeated in the Veronese by Alfonso of Calabria, but conquered Gallipoli, in Apulia, by sea. The balance was changed by Ludovico Sforza of Milan, who ultimately sided with Venice: this led to a quick peace, which was signed near Brescia on 7 August 1484. In spite of the numerous setbacks suffered in the campaign, Venice obtained the Polesine

Polesine (; vec, label=unified Venetian script, Połéxine ) is a geographic and historic area in the north-east of Italy whose limits varied through centuries; it had also been known as Polesine of Rovigo for some time.

Nowadays it corresponds w ...

and Rovigo

Rovigo (, ; egl, Ruig) is a city and ''comune'' in the Veneto region of Northeast Italy, the capital of the eponymous province.

Geography

Rovigo stands on the low ground known as Polesine, by rail southwest of Venice and south-southwest of P ...

, and increased its prestige in the Italian peninsula at the expense of Florence especially. In the late 1480s, Venice fought two brief campaigns against the new Pope Innocent VIII and Sigismund of Austria

Sigismund (26 October 1427 – 4 March 1496), a member of the House of Habsburg, was Duke of Austria from 1439 (elevated to Archduke in 1477) until his death. As a scion of the Habsburg Leopoldian line, he ruled over Further Austria and the ...

. Venetian troops were also present at the Battle of Fornovo, in which the Italian League fought against Charles VIII of France. Alliance with Spain/Aragon in the following reconquest of the Kingdom of Naples granted it the control of the Apulian ports, important strategic bases commanding the lower Adriatic, and the Ionian islands.

Despite the setbacks in the struggle against the Turks, at the end of the 15th century, with 180,000 inhabitants, Venice was the second largest city in Europe after Paris and probably the richest in the world. The territory of the Republic of Venice extended over approximately with 2.1 million inhabitants (for comparison, at about the same time England had three million inhabitants, the whole of Italy 11 million, France 13 million, Portugal 1.7 million, Spain six million, and the Holy Roman Empire ten million).

Administratively the territory was divided into three parts:

# the ''Dogado

The Dogado, or Duchy of Venice, was the homeland of the Republic of Venice, headed by the Doge. It comprised the city of Venice and the narrow coastal strip from Loreo to Grado, though these borders later extended from Goro to the south, Polesine ...

'' (the territory under the Doge), comprising the islets of the city and the original lands around the lagoon;

# the '' Stato da Mar'' (the State of the Sea), comprising Istria, Dalmatia, the Albanian coasts, the Apulian ports, the Venetian Ionian Islands, Crete

Crete ( el, Κρήτη, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cyprus, ...

, the Aegean Archipelago, Cyprus

Cyprus ; tr, Kıbrıs (), officially the Republic of Cyprus,, , lit: Republic of Cyprus is an island country located south of the Anatolian Peninsula in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Its continental position is disputed; while it is ge ...

and fortresses and trading posts around southeastern Europe and the Middle East;

# the '' Stato di Terraferma'' (the State of the Mainland), comprising Veneto, Friuli, Venetia Iulia, East Lombardy and Romagna.

In 1485, the French ambassador, Philippe de Commines

Philippe de Commines (or de Commynes or "Philippe de Comines"; Latin: ''Philippus Cominaeus''; 1447 – 18 October 1511) was a writer and diplomat in the courts of Burgundy and France. He has been called "the first truly modern writer" ( Charle ...

, wrote of Venice,

League of Cambrai, Lepanto and the loss of Cyprus

In 1499 Venice allied with Louis XII of France against Milan, gaining Cremona. In the same year the Ottoman sultan moved to attack Lepanto by land and sent a large fleet to support the offensive by sea. Antonio Grimani, more a businessman and diplomat than a sailor, was defeated in the sea Battle of Zonchio in 1499. The Turks once again sacked Friuli. Preferring peace to total war against the Turks, Venice surrendered the bases of Lepanto, Modon and Coron. Venice became rich on trade, but the guilds in Venice also produced superior silks, brocades, goldsmith jewelry and articles, armour and glass in the form of beads and eyeglasses. However, Venice's attention was diverted from its usual trade and maritime position by the delicate situation in Romagna, then one of the richest lands in Italy. Romagna was nominally part of the Papal States but effectively divided into a series of small lordships that were difficult for Rome's troops to control. Eager to take some of Venice's lands, all neighbouring powers joined in theLeague of Cambrai

League or The League may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* ''Leagues'' (band), an American rock band

* ''The League'', an American sitcom broadcast on FX and FXX about fantasy football

Sports

* Sports league

* Rugby league, full contact footba ...

in 1508, under the leadership of Pope Julius II

Pope Julius II ( la, Iulius II; it, Giulio II; born Giuliano della Rovere; 5 December 144321 February 1513) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 1503 to his death in February 1513. Nicknamed the Warrior Pope or th ...

. The pope wanted Romagna, emperor Maximilian I Friuli

Friuli ( fur, Friûl, sl, Furlanija, german: Friaul) is an area of Northeast Italy with its own particular cultural and historical identity containing 1,000,000 Friulians. It comprises the major part of the autonomous region Friuli Venezia Giuli ...

and Veneto

it, Veneto (man) it, Veneta (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 = ...

, Spain the Apulian ports, the king of France Cremona, the king of Hungary Dalmatia, and each of the others some part. The offensive against the huge army enlisted by Venice was launched from France. On 14 May 1509 Venice was crushingly defeated at the Battle of Agnadello, in the Ghiara d'Adda, marking one of the most delicate points of Venetian history. French and Imperial troops were occupying Veneto, but Venice managed to extricate itself through diplomatic efforts. The Apulian ports were ceded in order to come to terms with Spain, and Pope Julius II soon recognized the danger brought by the eventual destruction of Venice (then the only Italian power able to face large states like France or Ottoman Turkey). The citizens of the mainland rose to the cry of "Marco, Marco", and Andrea Gritti

Andrea Gritti (17 April 1455 – 28 December 1538) was the Doge of the Venetian Republic from 1523 to 1538, following a distinguished diplomatic and military career. He started out as a successful merchant in Constantinople and transitioned into t ...

recaptured Padua in July 1509, successfully defending it against the besieging Imperial troops. Spain and the pope broke off their alliance with France, and Venice also regained Brescia and Verona from France. After seven years of ruinous war, the Serenissima regained her mainland dominions up to the Adda. Although the defeat had turned into a victory, the events of 1509 marked the end of the Venetian expansion.

The

The Gasparo Contarini

Gasparo Contarini (16 October 1483 – 24 August 1542) was an Italian diplomat, cardinal and Bishop of Belluno. He was one of the first proponents of the dialogue with Protestants, after the Reformation.

Biography

He was born in Venice, the eldes ...

book ''De Magistratibus et Republica Venetorum'' (1544) illustrates the unique system of government in Venice and extols its various institutions. It also shows the astonishment of foreigners at the independence of Venice and its resistance to Italy's loss of freedom – and at it having emerged unscathed from the war against the League of Cambrai. Contarini suggested that the secret of Venice's greatness lay in the co-existence of the three types of government identified by Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ph ...

: monarchy