History of University College London on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The philosopher and jurist

The philosopher and jurist  Bentham's body is on public display at UCL in a wooden cabinet, at the end of the South Cloisters of the

Bentham's body is on public display at UCL in a wooden cabinet, at the end of the South Cloisters of the

UCL

University of London

UCL History Page

World of UCL- a free book about the history of UCL

UCL site 1827 {{University College London, university History of the University of London

University College London

, mottoeng = Let all come who by merit deserve the most reward

, established =

, type = Public research university

, endowment = £143 million (2020)

, budget = ...

(UCL) was founded on 11 February 1826, under the name ''London University'', as a secular

Secularity, also the secular or secularness (from Latin ''saeculum'', "worldly" or "of a generation"), is the state of being unrelated or neutral in regards to religion. Anything that does not have an explicit reference to religion, either negativ ...

alternative to the strictly religious universities of Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

and Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a College town, university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cam ...

. It was founded with the intention from the beginning of it being a university, not a college or institute. However its founders encountered strong opposition from the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britai ...

, the existing universities and the medical schools which prevented them from securing the Royal Charter

A royal charter is a formal grant issued by a monarch under royal prerogative as letters patent. Historically, they have been used to promulgate public laws, the most famous example being the English Magna Carta (great charter) of 1215, but s ...

under the title of "university" that would grant "London University" official recognition and allow it to award degrees. It was not until 1836, when the latter-day University of London

The University of London (UoL; abbreviated as Lond or more rarely Londin in post-nominals) is a federal public research university located in London, England, United Kingdom. The university was established by royal charter in 1836 as a degree ...

was established, that it was legally recognised (as a college, under the name of ''University College, London'') and granted the authority to submit students for the degree examinations of the University of London.

In 1900 when the University of London was reconstituted as a federal university, UCL became one of the founding colleges. Through much of the 20th century it surrendered its legal independence to become fully owned by the University of London. It was rechartered as an independent college in 1977, has received government funding directly since 1993, and gained the power to award degrees in its own right in 2005. From 2005, the Institute has branded itself as UCL (rather than University College London) and has used the strapline "London's Global University".

Early years

Priority

UCL's foundation date of 1826 makes it the third oldest university institution in England, and it was certainly founded with the intention of it being England's third university, but whether or not UCL is actually the third oldest university in England is questionable: UCL makes this claim on its website, but so do the Universities ofLondon

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

(1836) and Durham Durham most commonly refers to:

*Durham, England, a cathedral city and the county town of County Durham

*County Durham, an English county

* Durham County, North Carolina, a county in North Carolina, United States

*Durham, North Carolina, a city in N ...

(1832). Other higher education institutions in England have institutional ancestry preceding their formation as "universities": for example what is now the University of Nottingham

, mottoeng = A city is built on wisdom

, established = 1798 – teacher training college1881 – University College Nottingham1948 – university status

, type = Public

, chancellor ...

can trace some elements back to 1798 but only began university-level teaching with the foundation of the first civic college in 1881 (royal charter as University College Nottingham in 1903), and did not gain University status (via a new royal charter) until 1948. Conversely, King's College London (KCL) was founded after UCL, but received its Royal Charter (granting it legal existence as a corporation) in 1829, before UCL, so arguably is older, leading King's College students to claim the title of third oldest university in England for their institute.

In more recent publications, the claim was instead made that UCL was "the first university to be founded in London", avoiding explicit conflict with Durham's claim although maintaining the argument with KCL and the University of London. This claim still implied that UCL should be considered a university from 1826, and thus could be considered an implicit claim to be the third oldest university in England. It has, however, been dropped from the prospectus for 2019 entry although it appears on the UCL website.

The situation is further confounded by the fact that (unlike London and Durham) neither UCL nor KCL are ''de jure'' universities in their own right (though they are now ''de facto'' universities), but constituent colleges of the University of London

The University of London (UoL; abbreviated as Lond or more rarely Londin in post-nominals) is a federal public research university located in London, England, United Kingdom. The university was established by royal charter in 1836 as a degree ...

, and are thus not named as universities in 19th century references. It is a fact, however, that UCL was an early member of a rapid expansion of university institutions in the UK in the 19th century.

Foundation

The proposal for foundation of what became UCL arose from an open letter, published in ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper '' The Sunday Times'' (f ...

'' in February 1825, from the poet Thomas Campbell to the MP and follower of Jeremy Bentham

Jeremy Bentham (; 15 February 1748 Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O.S._4_February_1747.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New Style dates">O.S. 4 February 1747">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.htm ...

, Henry Brougham. Campbell had visited the university at Bonn

The federal city of Bonn ( lat, Bonna) is a city on the banks of the Rhine in the German state of North Rhine-Westphalia, with a population of over 300,000. About south-southeast of Cologne, Bonn is in the southernmost part of the Rhine-Ru ...

in today's Germany, which (unlike Oxbridge at that time) allowed religious toleration

Religious toleration may signify "no more than forbearance and the permission given by the adherents of a dominant religion for other religions to exist, even though the latter are looked on with disapproval as inferior, mistaken, or harmful". ...

. Brougham was a supporter of spreading education and a founder (in 1826) of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge

The Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge (SDUK) was founded in London in 1826, mainly at the instigation of Whig MP Henry Brougham, with the object of publishing information to people who were unable to obtain formal teaching or who pr ...

.

Isaac Lyon Goldsmid

Sir Isaac Lyon Goldsmid, 1st Baronet (13 January 1778 – 27 April 1859) was a financier and one of the leading figures in the Jewish emancipation in the United Kingdom, who became the first British Jew to receive a hereditary title.

Biography

...

, a leader of London's Jew

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""T ...

ish community, convinced Brougham and Campbell to work together on the proposed 'London University'. They were supported by representatives of a number of religious, philosophical and political groups, including Roman Catholics, Baptists, Utilitarians

In ethical philosophy, utilitarianism is a family of normative ethical theories that prescribe actions that maximize happiness and well-being for all affected individuals.

Although different varieties of utilitarianism admit different charact ...

, and abolitionists

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The Britis ...

. Others represented included James Mill

James Mill (born James Milne; 6 April 1773 – 23 June 1836) was a Scottish historian, economist, political theorist, and philosopher. He is counted among the founders of the Ricardian school of economics. He also wrote ''The History of Brit ...

and the Congregationalist benefactor Thomas Wilson. A 1923 mural in the UCL Main Library depicts as "The Four Founders of UCL" Bentham, Brougham, Campbell and Henry Crabb Robinson

Henry Crabb Robinson (13 May 1775 – 5 February 1867) was an English lawyer, remembered as a diarist. He took part in founding London University.

Life

Robinson was born in Bury St. Edmunds, Suffolk, third and youngest son of Henry Robinson ( ...

(although Bentham, while an inspiration to the other three, was not directly involved in the College's founding).

The College formally came into existence as a Joint Stock Company on 11 February 1826 as 'The University of London', and was unique in Great Britain in being completely secular

Secularity, also the secular or secularness (from Latin ''saeculum'', "worldly" or "of a generation"), is the state of being unrelated or neutral in regards to religion. Anything that does not have an explicit reference to religion, either negativ ...

; in fact no minister of religion was allowed to sit on the College Council. Thomas Arnold was to refer to it as "that Godless institution in Gower Street".

The Council appointed in 1827 as Warden Leonard Horner

Leonard Horner FRSE FRS FGS (17 January 1785 – 5 March 1864) was a Scottish merchant, geologist and educational reformer. He was the younger brother of Francis Horner.

Horner was a founder of the School of Arts of Edinburgh, now Heriot-Wa ...

, the founder of what is now Heriot-Watt University, but after internal disagreements he left in 1831 and the post was abolished. During this period the College founded University College School

("Slowly but surely")

, established =

, closed =

, type = Public schoolIndependent day school

, religion =

, president =

, head_label = Headmaster

, head = Mark Beard

, r_head_label =

, r_he ...

, originally called the London University School (1830). In 1833 the foundation stone was laid for the hospital which had always been planned in association with the College, then known as the 'North London Hospital', but today University College Hospital

University College Hospital (UCH) is a teaching hospital in the Fitzrovia area of the London Borough of Camden, England. The hospital, which was founded as the North London Hospital in 1834, is closely associated with University College Lond ...

.

The University College was founded based on practices at the University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh ( sco, University o Edinburgh, gd, Oilthigh Dhùn Èideann; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in post-nominals) is a public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Granted a royal charter by King James VI in 15 ...

and other Scottish universities. "The strongest, single, intellectual influence was that of Edinburgh, and, from the example of the Scottish Universities, London drew many of its most distinctive features. The extended range of the subjects of university study, the lecture system, the non-residence of students, their admission to single courses, the absence of religious tests, the dependence of the professors upon fees and the democratic character of the institutions, were all deliberate imitations of Scottish practice"

The Council sought to arrange a formal incorporation of the institution under the name of the 'University of London' via a royal charter

A royal charter is a formal grant issued by a monarch under royal prerogative as letters patent. Historically, they have been used to promulgate public laws, the most famous example being the English Magna Carta (great charter) of 1215, but s ...

, which would have officially granted them the title of "university" and thus degree awarding powers. This was first applied for in 1830, under the Whig government of Earl Grey

Earl Grey is a title in the peerage of the United Kingdom. It was created in 1806 for General Charles Grey, 1st Baron Grey. In 1801, he was given the title Baron Grey of Howick in the County of Northumberland, and in 1806 he was created Viscou ...

, with Brougham as Lord Chancellor

The lord chancellor, formally the lord high chancellor of Great Britain, is the highest-ranking traditional minister among the Great Officers of State in Scotland and England in the United Kingdom, nominally outranking the prime minister. Th ...

, another London University council member, Sir Thomas Denman as Attorney General (until his appointment as Lord Chief Justice of England

Lord is an appellation for a person or deity who has authority, control, or power over others, acting as a master, chief, or ruler. The appellation can also denote certain persons who hold a title of the peerage in the United Kingdom, or a ...

in 1832)

and two former councillors Lord Lansdowne (1826 - 1830) and Lord John Russell

John Russell, 1st Earl Russell, (18 August 1792 – 28 May 1878), known by his courtesy title Lord John Russell before 1861, was a British Whig and Liberal statesman who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1846 to 1852 and a ...

(1826 - 1828) in the cabinet as Lord President of the Council and Paymaster of the Forces

The Paymaster of the Forces was a position in the British government. The office was established in 1661, one year after the Restoration of the Monarchy to King Charles II, and was responsible for part of the financing of the British Army, in ...

respectively.

In February 1831 it was reported that "a charter, which now only awaits the royal signature, is to be granted to the University of London". But before it could be signed, the University of Cambridge voted to petition the king against granting any charter allowing degrees to be awarded "designated by the same titles, or granting the same privileges, as the degrees now conferred by the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge".

The attempt to win a charter as a University in 1831 was successfully blocked by Oxford and Cambridge. The application was renewed in 1833, but found formidable opposition in Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: representing the electorate, making laws, and overseeing the government via hearings and inquiries. Th ...

, from the Church of England, from Oxford and Cambridge again, and from the medical profession. Opposition also came from abroad; Count Metternich instructed his ambassador to Britain in 1825 to "tell His Majesty of my absolute conviction that the implementation of this plan would bring about England's ruin". Thomas Babington Macaulay

Thomas Babington Macaulay, 1st Baron Macaulay, (; 25 October 1800 – 28 December 1859) was a British historian and Whig politician, who served as the Secretary at War between 1839 and 1841, and as the Paymaster-General between 1846 and 1 ...

however predicted "that it is destined to a long, a glorious and a beneficent existence".

In April and May 1834, the renewed application for a charter was discussed by the Privy Council, with petitions against the application being heard from Oxford and Cambridge, the Royal College of Physicians

The Royal College of Physicians (RCP) is a British professional membership body dedicated to improving the practice of medicine, chiefly through the accreditation of physicians by examination. Founded by royal charter from King Henry VIII in 1 ...

, and the medical schools in London. The hearings were inconclusive and no recommendation was made before the Whig government, by then led by Lord Melbourne

William Lamb, 2nd Viscount Melbourne, (15 March 177924 November 1848), in some sources called Henry William Lamb, was a British Whig politician who served as Home Secretary (1830–1834) and Prime Minister (1834 and 1835–1841). His first pre ...

after Grey's retirement, fell in November 1834.

In March 1835, another London University council member, William Tooke, proposed an address in the House of Commons praying the King to grant a charter to London University allowing it to grant degrees in all faculties except theology. This was carried 246 - 136 despite the opposition of the government. The response was that the Privy Council would be called upon to report on the matter. Then the Tory government fell and Melbourne returned as Prime Minister.

Russell and Lansdowne returned to government with Melbourne, Russell being promoted to Home Secretary

The secretary of state for the Home Department, otherwise known as the home secretary, is a senior minister of the Crown in the Government of the United Kingdom. The home secretary leads the Home Office, and is responsible for all national s ...

. But Brougham was out, with Melbourne telling Russell, "it can never be safe to place him … in an important executive or administrative office". On 30 July, in response to a question from Tooke, the Attorney General Sir John Campbell announced that two charters would be granted, one to the (then) London University (i.e. UCL) "not as a University but as a College", with "no power … of granting academical degrees", the second "for the purpose of establishing a Metropolitan University" - what was to become the University of London

The University of London (UoL; abbreviated as Lond or more rarely Londin in post-nominals) is a federal public research university located in London, England, United Kingdom. The university was established by royal charter in 1836 as a degree ...

. This was condemned as a "barren collegiate charter" by Tooke, who called on the London University (UCL) "to consider whether, His Majesty in his most gracious answer to the Address of the House of Commons recognised by name, and in explicit terms, the , it is not by this royal and official sanction of its style as a University, entitled, without further pageantry or form, to confer all manner of degrees except in Theology and Medicine" (emphasis in original).

On 2 December 1835, a meeting of the proprietors discussed the government plan. Brougham explained that while "it went a little to his heart … to sink into a college when they had originally started as an university" this would be worth it for the benefits the new University of London would bring them. On one point, however, he objected to the plan – the names of the degrees were to be A.B., A.M., etc., differentiating them (as requested by Cambridge's 1831 petition) from the ancient universities. He said that "for his own part he would rather accept it he government's plan coupled as it is with these objections, than reject it altogether", although he thought the Council should "exert themselves to the utmost" to get the government to agree to the new university granting the same degrees as Oxford and Cambridge. Tooke proposed the resolution: "That although the tenor of his Majesty's gracious answer to the address of the House of Commons, for a charter to enable the London University to grant degrees in all faculties except theology or divinity, was not fully realized, yet, as the government had proposed a comprehensive and efficient plan, this meeting agrees to the same, resting with confidence on the board of examiners to be appointed by government." After some discussion, this was amended to: "That his Majesty's Ministers having, in consequence of the gracious answer returned from the throne to the address of the House of Commons, devised a more efficient and comprehensive plan than was contemplated for giving academical honours in all the faculties, except divinity, this meeting is satisfied that this institution has nothing to fear from competition, and cordially and gratefully accepts the said plan, and recommends it to the adoption of the Council." The amended resolution was passed unanimously.

The government did, in the event, alter the name of the degrees to be granted by the University of London, and the charter of incorporation under the name of University College, London was issued on 28 November 1836, with the charter establishing the University of London being issued later on the same day.

After the Council had recommended acceptance of the charter, a Special General Meeting of the proprietors was called on 28 January 1837. Despite concerns being raised about the possible impact of the Act of Uniformity on the college, the proprietors voted unanimously to accept the charter.

Development

In December 1837 the sub-committee drawing up the regulations for examinations in classics at the University of London passed a resolution (10 to 9) in favour of requiring candidates for the BA to pass an examination on one of the gospels or the Acts of the Apostles on Greek, as well as on scripture history. The University referred this decision to the home secretary,Lord John Russell

John Russell, 1st Earl Russell, (18 August 1792 – 28 May 1878), known by his courtesy title Lord John Russell before 1861, was a British Whig and Liberal statesman who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1846 to 1852 and a ...

, to determine whether this would be legal.

Russell was also petitioned by a United Committee representing three dissenting denominations and by the Council of UCL. The dissidents pointed out that introducing an examination on the Bible was "an indirect violation of the liberal principle on which the University of London was founded", the Council agreed, adding that the proprietors of UCL had been "induced to surrender any claim which they might be supposed to have acquired to a charter of incorporation as a University … on the clear understanding that the University this proposed to be substituted was to be grounded on the same principles as the institution which had given rise to it".

These led to a request from Russell to Lord Burlington

Earl of Burlington is a title that has been created twice, the first time in the Peerage of England in 1664 and the second in the Peerage of the United Kingdom in 1831. Since 1858, Earl of Burlington has been a courtesy title used by the duk ...

(Chancellor of the University of London) on 18 December "to bring again under the consideration of the Senate the proposed rule". This was opposed, however, by a letter to the Senate of the University (via Burlington) from the Principal ( Hugh James Rose) and the professors of Mathematics, Classical Literature, and English Literature and Modern History at King's College London. They claimed that as encouragement of a "regular and liberal course of education" was one of the objectives of the University, as laid out in its charter, it could not positively exclude the study of the Bible, which they regarded as an essential part of education.

In the end, victory went, as with the dispute over the names of London degrees, to the UCL party. The University of London Senate voted "almost unanimously" in February 1838 to make examinations on the Bible optional. The incident did, however, serve to emphasise the lack of connection between the colleges and the University, with the Morning Chronicle noting that: "The possibility of so nugatory a proceeding would have been obiviated had the University College been allowed some participation in the Acts of the University."

On 7 May 1842, the proprietors annulled the regulations of the original Deed of Settlement and put in place new bylaws, including a provision for shares to be forfeited or ceded back to the College who would distribute them to honours graduates from the University of London who had studied at the College, thus admitting some alumni to the membership and management of the College. These alumni members were termed "Fellows of the College".

In 1869 an even greater constitutional change took place. The University College (London) Act was passed, with the effect of "divesting he College

He or HE may refer to:

Language

* He (pronoun), an English pronoun

* He (kana), the romanization of the Japanese kana へ

* He (letter), the fifth letter of many Semitic alphabets

* He (Cyrillic), a letter of the Cyrillic script called ''He'' ...

of the character of a proprietary body of shareholders, and … its reconstitution for public objects". Fears had arisen that the proprietors retained the right to dissolve the College and divide its assets. There were also doubts as to whether the 1842 bylaws were legal. A meeting of proprietors unanimously approved the bill on 24 February 1869, and it became law on 24 June 1869. The act revoked the Royal Charter of 1836 and reincorporated the College (still under the name of "University College, London"); the members of the College being defined as the former proprietors, who became "governors" unless they had previously been fellows in which case they remained "fellows", and the registered donors, who became "life governors".

The Campaign for a Teaching University for London

The new charter awarded to the University of London in 1858 broke the exclusive connection between the University and the affiliated schools and colleges. The change was strongly objected to by UCL, with the proprietors passing motions saying "That this meeting … understanding that the Senate f the University of Londonproposes that collegiate education shall no longer be necessary for candidates for degrees in arts and laws, desires to express is disapproval of the proposed change, as one likely to be injurious to the cause of regular and systematic education, and as not only lowering the value, but altering the very meaning, of an English University degree" and "That University College having been pointed out in 1835 by the address of the House of Commons to the Crown, as the future University of London and having chiefly waived its claims to that high dignity in order to promote the public welfare, has peculiar right to object to a change which will destroy the essential character of that university constitution on the faith of which it consented to surrender its position".George Grote

George Grote (; 17 November 1794 – 18 June 1871) was an English political radical and classical historian. He is now best known for his major work, the voluminous ''History of Greece''.

Early life

George Grote was born at Clay Hill near B ...

objected to the resolutions, noting their similarity to the objections raised against allowing dissenters to take degrees. Despite the objections of UCL (and other colleges), the new charter was passed.

In the latter half of the 19th century, the tensions between the colleges and the University of London led to a campaign for a Teaching University for London. It was first proposed in 1864 that teaching should be added to the University of London, but this was rejected by the University Senate. It was proposed again in 1878 and again rejected. After the formation of the Victoria University in 1880, with a federal link between teaching (initially only in Owens College) and examining in the University, the University of London Convocation (which had been formed from the graduates by the 1858 charter) voted in favour of a similar move for London in 1881 and 1882. These were again defeated in the Senate.

In 1884 the Association for Promotion of a Teaching University for London was publicly launched by UCL, King's, and the London medical schools. However, Convocation was persuaded that a teaching university would lead to a reduction in degree standards and voted against a teaching University in 1885.

It was felt that with the creation of the Victoria University, Owens College had, despite being smaller and younger than UCL, achieved what UCL had been unable to do – gain degree-awarding powers.

considering applying to become a college of the Victoria University, UCL joined forces with King's and the medical schools to propose the formation of a separate federal university in London, to be called the Albert University. The Royal College of Physicians and the Royal College of Surgeons, meanwhile, petitioned that they be granted degree awarding powers in Medicine and Surgery. Faced with these various options, a Royal commission was established in 1888 to look into the matter.

The commission reported in 1889, rejecting the petition of the Royal Colleges and recommending reform of the University of London, with a minority report favouring the granting of the charter to the Albert University. It was agreed that if reform of the existing University failed, the new University should be established.

A complicated scheme for reform of the University was drawn up in 1891 but was rejected by Convocation, leading to a renewal of the petition of UCL and King's to form the Albert University. This was approved by the Privy Council later in 1891 and was (in accordance with an 1871 law) laid in the Houses of Parliament for comment, with the name now changed to the Gresham University with the joining of Gresham College

Gresham College is an institution of higher learning located at Barnard's Inn Hall off Holborn in Central London, England. It does not enroll students or award degrees. It was founded in 1596 under the will of Sir Thomas Gresham, and hosts ove ...

to the scheme.

The charter for the Gresham University was opposed by the Victoria University, by the Senate and Convocation of the University of London, by the provincial medical schools, and by other colleges in London that were not part of the scheme. In response to this, the government set up a second Royal Commission in 1892.

The new commission recommended reform of the University of London rather than establishment of a new body, and that this be carried out by Act of Parliament rather than by Royal Charter. This was accepted by Convocation in 1895 and a bill to put it into effect had past its first reading when the government fell. A second bill was introduced in the House of Lords, but did not pass the Commons. A third bill was introduced in the Lords in February 1898 and finally passed both houses, despite a number of blocking amendments, receiving Royal Assent on 12 August.

The University of London was reformed under the University of London Act 1898 to become a federal teaching university for London while retaining its position as an examining body for colleges outside of the capital. UCL became a school of the University "in all faculties".

Jeremy Bentham and UCL

The philosopher and jurist

The philosopher and jurist Jeremy Bentham

Jeremy Bentham (; 15 February 1748 Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O.S._4_February_1747.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New Style dates">O.S. 4 February 1747">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.htm ...

(1748–1832), advocate of Utilitarianism, is often credited with being one of the founders of the original 'University of London'. This is not the case, although the myth of his direct participation has been perpetuated in a mural by Henry Tonks

Henry Tonks, FRCS (9 April 1862 – 8 January 1937) was a British surgeon and later draughtsman and painter of figure subjects, chiefly interiors, and a caricaturist. He became an influential art teacher.

He was one of the first British arti ...

, in the dome above the Flaxman gallery (named after artist John Flaxman

John Flaxman (6 July 1755 – 7 December 1826) was a British sculptor and draughtsman, and a leading figure in British and European Neoclassicism. Early in his career, he worked as a modeller for Josiah Wedgwood's pottery. He spent several ye ...

in the UCL Main Building

The Main Building of University College London, facing onto Gower Street, Bloomsbury, includes the Octagon, Quad, Cloisters, Main Library, Flaxman Gallery and the Wilkins Building. The North Wing, South Wing, Chadwick Building and Pearson Buil ...

). This shows William Wilkins, the architect of the main building, submitting the plans to Bentham for his approval while the portico is under construction in the background. The scene is however apocryphal. Bentham was eighty years of age when the new University opened its doors in 1828, and took no formal part in the direct campaign to bring it into being.

Although Bentham played no direct part in the establishment of UCL, he can still be considered as its spiritual father. Many of the founders held him in high esteem, and their project embodied many of his ideas on education and society. Jeremy Bentham was a strong advocate for making higher education more widely available, and is often linked with the University's early adoption of a policy of making all courses available to people regardless of sex, religion or political beliefs. When the College's Upper Refectory was refurbished in 2003, it was renamed the Jeremy Bentham Room (sometimes abbreviated JBR) in tribute.

UCL Main Building

The Main Building of University College London, facing onto Gower Street, Bloomsbury, includes the Octagon, Quad, Cloisters, Main Library, Flaxman Gallery and the Wilkins Building. The North Wing, South Wing, Chadwick Building and Pearson Buil ...

; he had directed in his will that he wanted his body to be preserved as a lasting memorial to the university. This 'Auto-Icon' has become famous. Unfortunately, when it came to his head, the preservation process went disastrously wrong and left it badly disfigured. A wax

Waxes are a diverse class of organic compounds that are lipophilic, malleable solids near ambient temperatures. They include higher alkanes and lipids, typically with melting points above about 40 °C (104 °F), melting to giv ...

head was made to replace it; the actual head is now kept in the college vaults.

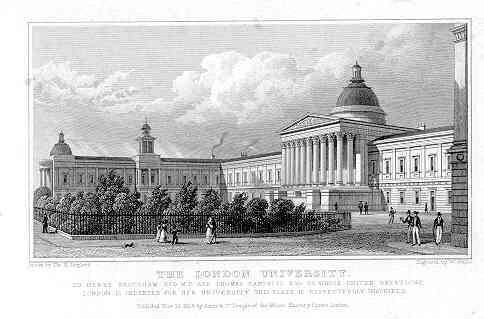

Construction of the Main Building

In 1827, a year after the founding of UCL, construction of the Main Building began on the site of the proposed Carmarthen Square (at the time wasteland, used occasionally for duelling or dumping). Eight acres of ground were purchased for £30,000 by Goldsmid, John Smith and Benjamin Shaw. The Octagon Building is a term used for the whole of the Main Building, but more appropriately for a central part of it. At the centerpiece of the building is an ornate dome, which is visible throughout the immediate area. The Octagon was designed by the Architect William Wilkins, who also designed theNational Gallery

The National Gallery is an art museum in Trafalgar Square in the City of Westminster, in Central London, England. Founded in 1824, it houses a collection of over 2,300 paintings dating from the mid-13th century to 1900. The current Director ...

. The original plans by Wilkins called for a U shaped enclosure around the Quad (square). These plans however were stymied for want of funding, and work on the main building was not completed until the 20th century, (after the building itself had suffered damage during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

). The Main Building was finally finished in 1985, 158 years after the foundations were laid, with a formal opening ceremony by Queen Elizabeth II

Elizabeth II (Elizabeth Alexandra Mary; 21 April 1926 – 8 September 2022) was Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms from 6 February 1952 until her death in 2022. She was queen regnant of 32 sovereign states during ...

.

Milestones

UCL claims to be the first higher education institution in England to accept students of any race, class or religion, although there are records of at least one mixed-race student from Jamaica entering Oxford in 1799. More recent publications have revised the claim to drop the mention of race. UCL also claims to have been the first to accept women on equal terms with men, in 1878. However, theUniversity of Bristol

, mottoeng = earningpromotes one's innate power (from Horace, ''Ode 4.4'')

, established = 1595 – Merchant Venturers School1876 – University College, Bristol1909 – received royal charter

, type ...

also makes this claim, University College Bristol having admitted women from its foundation in 1876. The College of Physical Sciences in Newcastle, a predecessor institution of Newcastle University, also admitted women from its foundation, in 1871. At UCL, women were only admitted to Arts, Law and Science in 1878 and remained barred from Engineering and Medicine. Women were first allowed to enter the medical school in 1917, and admissions remained restricted until much later. Men and women had separate staff common rooms until 1969, when Brian Woledge (then Fielden professor of French) and David Colquhoun

David Colquhoun (born 19 July 1936) is a British pharmacologist at University College London (UCL). He has contributed to the general theory of receptor and synaptic mechanisms, and in particular the theory and practice of single ion channel ...

(then a young lecturer) got a motion passed to end segregation.

UCL was a pioneer in teaching many topics at university level, establishing the first British professorship

Professor (commonly abbreviated as Prof.) is an academic rank at universities and other post-secondary education and research institutions in most countries. Literally, ''professor'' derives from Latin as a "person who professes". Professors ...

s in, amongst other subjects, chemistry (1828), English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ide ...

(1828, Rev. Thomas Dale

Sir Thomas Dale ( 1570 − 19 August 1619) was an English naval commander and deputy-governor of the Virginia Colony in 1611 and from 1614 to 1616. Governor Dale is best remembered for the energy and the extreme rigour of his administration in ...

), German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

** Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

(1828, Ludwig von Mühlenfels), Italian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, an ethnic group or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance language

*** Regional Ita ...

(1828, Sir Antonio Panizzi

Sir Antonio Genesio Maria Panizzi (16 September 1797 – 8 April 1879), better known as Anthony Panizzi, was a naturalised British citizen of Italian birth, and an Italian patriot. He was a librarian, becoming the Principal Librarian (i.e. head ...

), geography

Geography (from Greek: , ''geographia''. Combination of Greek words ‘Geo’ (The Earth) and ‘Graphien’ (to describe), literally "earth description") is a field of science devoted to the study of the lands, features, inhabitants, an ...

(1833), French (1834, P. F. Merlet), zoology

Zoology ()The pronunciation of zoology as is usually regarded as nonstandard, though it is not uncommon. is the branch of biology that studies the animal kingdom, including the structure, embryology, evolution, classification, habits, and ...

(1874, Sir Ray Lankester

Sir Edwin Ray Lankester (15 May 1847 – 13 August 1929) was a British zoologist.New International Encyclopaedia.

An invertebrate zoologist and evolutionary biologist, he held chairs at University College London and Oxford University. He was th ...

), Egyptology

Egyptology (from ''Egypt'' and Greek , ''-logia''; ar, علم المصريات) is the study of ancient Egyptian history, language, literature, religion, architecture and art from the 5th millennium BC until the end of its native religious p ...

(1892), and electrical engineering (1885, Sir Ambrose Fleming). UCL also claims to have offered the first systematic teaching in Engineering, Law and Medicine at an English university, although its Engineering course, established in 1841, followed the establishment of engineering courses at Durham (1838) and King's College London (1839).

The Slade School of Fine Art

The UCL Slade School of Fine Art (informally The Slade) is the art school of University College London (UCL) and is based in London, England. It has been ranked as the UK's top art and design educational institution. The school is organised as ...

was founded at the College in 1871 following a bequest from Felix Slade

Felix Joseph Slade (6 August 1788 – 29 March 1868) was an English lawyer and collector of glass, books and prints.

A fellow of the Society of Antiquaries (1866) and a philanthropist who endowed three Slade Professorships of Fine Art at the ...

.

UCL claims to be the first University institution in England to establish a students' union, in 1893. However, this postdates the formation of the Liverpool Guild of Students

Liverpool Guild of Students is the students' union of the University of Liverpool. The Guild was founded in 1889, with the building constructed in 1911.

The title also refers to the Guild of Students building, which is the centre point of acti ...

in 1892. Men and women had separate unions until 1945.Landmarks20th century

In 1900 the University of London was reconstituted as a federal university with new statutes drawn up under the University of London Act 1898. UCL, along with a number of other colleges in London, became schools of the University of London. While most of the constituent institutions retained their autonomy, UCL was merged into the University in 1907 under the University College London (Transfer) Act 1905 and lost its legal independence. (KCL also surrendered its independence a few years later, in 1910.) This necessitated the separation of University College Hospital and University College School as separate institutions (which they remain). A new charter in 1977 re-incorporated UCL and restored its independence, although it remained a college of the University of London and was not able to award degrees in its own right until 2005. Further pioneering professorships established in the 20th century includedphonetics

Phonetics is a branch of linguistics that studies how humans produce and perceive sounds, or in the case of sign languages, the equivalent aspects of sign. Linguists who specialize in studying the physical properties of speech are phoneticians. ...

(1921, Daniel Jones), Ramsay professor of chemical engineering

Chemical engineering is an engineering field which deals with the study of operation and design of chemical plants as well as methods of improving production. Chemical engineers develop economical commercial processes to convert raw materials int ...

(1923, E. C. Williams), psychology

Psychology is the scientific study of mind and behavior. Psychology includes the study of conscious and unconscious phenomena, including feelings and thoughts. It is an academic discipline of immense scope, crossing the boundaries between ...

(1928, Charles Spearman

Charles Edward Spearman, FRS (10 September 1863 – 17 September 1945) was an English psychologist known for work in statistics, as a pioneer of factor analysis, and for Spearman's rank correlation coefficient. He also did seminal work on mod ...

), and papyrology

Papyrology is the study of manuscripts of ancient literature, correspondence, legal archives, etc., preserved on portable media from antiquity, the most common form of which is papyrus, the principal writing material in the ancient civilizations ...

(1950, Sir Eric Gardner Turner

Sir Eric Gardner Turner CBE (26 February 1911 – 20 April 1983) was an English papyrologist and classicist.

Turner was born in Broomhill, Sheffield. He was educated at King Edward VII School and Magdalen College, Oxford, and taught classics ...

).

In 1906, Sir Gregory Foster

Sir Thomas Gregory Foster (10 June 1866 – 24 September 1931) was the Provost of University College London from 1904 to 1929,Elizabeth J. Morse, 'Foster, Sir (Thomas) Gregory, first baronet (1866–1931)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biograph ...

, who had been Secretary of the College, was appointed to the new post of Provost of UCL, which he occupied until 1929.

In 1973, UCL became the first international link to the ARPANET

The Advanced Research Projects Agency Network (ARPANET) was the first wide-area packet-switched network with distributed control and one of the first networks to implement the TCP/IP protocol suite. Both technologies became the technical fou ...

, the precursor of today's internet

The Internet (or internet) is the global system of interconnected computer networks that uses the Internet protocol suite (TCP/IP) to communicate between networks and devices. It is a '' network of networks'' that consists of private, pub ...

, sending the world's first electronic mail

Electronic mail (email or e-mail) is a method of exchanging messages ("mail") between people using electronic devices. Email was thus conceived as the electronic (digital) version of, or counterpart to, mail, at a time when "mail" meant ...

, or e-mail

Electronic mail (email or e-mail) is a method of exchanging messages ("mail") between people using electronic devices. Email was thus conceived as the electronic (digital) version of, or counterpart to, mail, at a time when "mail" meant ...

, in the same year. UCL was also one of the first universities in the world to conduct space research. It is the driving force of the Mullard Space Science Laboratory

The UCL Mullard Space Science Laboratory (MSSL) is the United Kingdom's largest university space research group. MSSL is part of the Department of Space and Climate Physics at University College London (UCL), one of the first universities in the ...

, managed by UCL's Department of Space and Climate Physics.

In 1993 a shake up of the University of London meant that UCL (and other colleges) gained direct access to government funding and the right to confer University of London degrees themselves. This led to UCL being regarded as a ''de facto'' university in its own right.

Mergers

In 1986 the Institute of Archaeology became a department of UCL, and in 1999 theSchool of Slavonic and East European Studies

The UCL School of Slavonic and East European Studies (SSEES ) is a school of University College London (UCL) specializing in Central, Eastern and South-Eastern Europe, Russia and Eurasia. It teaches a range of subjects, including the history ...

also joined the College.

In 1988 UCL merged with the Institute of Laryngology & Otology, the Institute of Orthopaedics, the Institute of Urology & Nephrology and Middlesex Hospital Medical School

Middlesex Hospital was a teaching hospital located in the Fitzrovia area of London, England. First opened as the Middlesex Infirmary in 1745 on Windmill Street, it was moved in 1757 to Mortimer Street where it remained until it was finally clos ...

. In 1994 the University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust

University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (UCLH) is an NHS foundation trust based in London, United Kingdom. It comprises University College Hospital, University College Hospital at Westmoreland Street, the UCH Macmillan Cancer ...

was established. UCL merged with the College of Speech Sciences and the Institute of Ophthalmology in 1995, the School of Podiatry in 1996 and the Institute of Neurology in 1997. In August 1998 the medical school at UCL joined with the Royal Free Hospital Medical School to create the Royal Free and University College Medical School, renamed in October 2008 to the UCL Medical School

UCL Medical School is the medical school of University College London (UCL) and is located in London, United Kingdom. The School provides a wide range of undergraduate and postgraduate medical education programmes and also has a medical educatio ...

. In 1999 the Eastman Dental Institute joined the Medical School, which, resulting from the incorporation of these major postgraduate medical institutes, has made UCL one of the world's leading centres for biomedical research.

Galton and Eugenics

Although Francis Galton was never formally associated with UCL, he worked closely with Karl Pearson andFlinders Petrie

Sir William Matthew Flinders Petrie ( – ), commonly known as simply Flinders Petrie, was a British Egyptologist and a pioneer of systematic methodology in archaeology and the preservation of artefacts. He held the first chair of Egyp ...

both professors at the college. In 1904, UCL established the Eugenics

Eugenics ( ; ) is a fringe set of beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetic quality of a human population. Historically, eugenicists have attempted to alter human gene pools by excluding people and groups judged to be inferior o ...

Records Office at Galton's urging, and in 1907 this became the Eugenics Laboratory.

Galton died in 1911 and left funds to establish a Chair in National Eugenics, with Pearson named in his will as the first holder. In 1963, the Francis Galton Laboratory of National Eugenics became the Galton Laboratory of the Department of Human Genetics & Biometry, and in 1996 became part of the Department of Biology.

In recent years, Galton's legacy has been controversial. In 2014, the Provost of UCL, Michael Arthur, was asked by a student why Galton was still celebrated. Arthur replied "You’re not the first person to make that point to me; my only defence is that I inherited him". On 19 June 2020, UCL’s President & Provost Professor Michael Arthur announced the "denaming" of spaces and buildings named Francis Galton (and Karl Pearson) with immediate effect.

Nobel Laureates

19 Nobel Laureates of the 20th century were based at UCL: 1904 Chemistry: SirWilliam Ramsay

Sir William Ramsay (; 2 October 1852 – 23 July 1916) was a Scottish chemist who discovered the noble gases and received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1904 "in recognition of his services in the discovery of the inert gaseous element ...

• 1913 Literature: Rabindranath Tagore

Rabindranath Tagore (; bn, রবীন্দ্রনাথ ঠাকুর; 7 May 1861 – 7 August 1941) was a Bengali polymath who worked as a poet, writer, playwright, composer, philosopher, social reformer and painter. He resh ...

• 1915 Physics: Sir William Henry Bragg

Sir William Henry Bragg (2 July 1862 – 12 March 1942) was an English physicist, chemist, mathematician, and active sportsman who uniquelyThis is still a unique accomplishment, because no other parent-child combination has yet shared a Nobel ...

• 1921 Chemistry: Frederick Soddy

Frederick Soddy FRS (2 September 1877 – 22 September 1956) was an English radiochemist who explained, with Ernest Rutherford, that radioactivity is due to the transmutation of elements, now known to involve nuclear reactions. He also prov ...

• 1922 Physiology or Medicine: Archibald Vivian Hill

• 1928 Physics: Owen Willans Richardson

Sir Owen Willans Richardson, FRS (26 April 1879 – 15 February 1959) was a British physicist who won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1928 for his work on thermionic emission, which led to Richardson's law.

Biography

Richardson was born in Dews ...

• 1929 Physiology or Medicine: Sir Frederick Gowland Hopkins

Sir Frederick Gowland Hopkins (20 June 1861 – 16 May 1947) was an English biochemist who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1929, with Christiaan Eijkman, for the discovery of vitamins, even though Casimir Funk, a Po ...

• 1936 Physiology or Medicine: Sir Henry Hallett Dale

Sir Henry Hallett Dale (9 June 1875 – 23 July 1968) was an English pharmacologist and physiologist. For his study of acetylcholine as agent in the chemical transmission of nerve pulses (neurotransmission) he shared the 1936 Nobel Prize in Ph ...

• 1944 Chemistry: Otto Hahn

Otto Hahn (; 8 March 1879 – 28 July 1968) was a German chemist who was a pioneer in the fields of radioactivity and radiochemistry. He is referred to as the father of nuclear chemistry and father of nuclear fission. Hahn and Lise Meitner ...

• 1947 Chemistry: Sir Robert Robinson

• 1955 Chemistry: Vincent du Vigneaud

Vincent du Vigneaud (May 18, 1901 – December 11, 1978) was an American biochemist. He was recipient of the 1955 Nobel Prize in Chemistry "for his work on biochemically important sulphur compounds, especially for the first synthesis of a polypep ...

• 1959 Chemistry: Jaroslav Heyrovský

Jaroslav Heyrovský () (December 20, 1890 – March 27, 1967) was a Czech chemist and inventor. Heyrovský was the inventor of the polarographic method, father of the electroanalytical method, and recipient of the Nobel Prize in 1959 for his ...

• 1960 Physiology or Medicine: Peter Brian Medawar

Sir Peter Brian Medawar (; 28 February 1915 – 2 October 1987) was a Brazilian-British biologist and writer, whose works on graft rejection and the discovery of acquired immune tolerance have been fundamental to the medical practice of tissu ...

• 1962 Physiology or Medicine: Francis Harry Compton Crick

• 1963 Physiology or Medicine: Andrew Fielding Huxley

Sir Andrew Fielding Huxley (22 November 191730 May 2012) was an English physiologist and biophysicist. He was born into the prominent Huxley family. After leaving Westminster School in central London, he went to Trinity College, Cambridge on ...

• 1970 Physiology or Medicine: Bernard Katz

• 1970 Physiology or Medicine: Ulf Svante von Euler

• 1988 Physiology or Medicine: Sir James W. Black

Sir James Whyte Black (14 June 1924 – 22 March 2010) was a Scottish physician and pharmacologist. Together with Gertrude B. Elion and George H. Hitchings, he shared the Nobel Prize for Medicine in 1988 for pioneering strategies for rational d ...

• 1991 Physiology or Medicine: Bert Sakmann

Bert Sakmann (; born 12 June 1942) is a German cell physiologist. He shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine with Erwin Neher in 1991 for their work on "the function of single ion channels in cells," and the invention of the patch cl ...

21st century

The UCL Jill Dando Institute of Crime Science, the first university department in the world devoted specifically to reducing crime, was founded in 2001. In October 2002, a plan to merge UCL withImperial College London

Imperial College London (legally Imperial College of Science, Technology and Medicine) is a public research university in London, United Kingdom. Its history began with Prince Albert, consort of Queen Victoria, who developed his vision for a cu ...

was announced by both institutions. The merger was widely seen as a ''de facto'' takeover of UCL by Imperial College and was opposed by both staff and UCL Union

Students' Union UCL (formerly University College London Union) is the students' union of University College London. Founded in 1893, it is one of the oldest students' unions in England, although postdating the Liverpool Guild of Students which ...

, the students' union. A vigorous campaign included websites run by both staff (David Colquhoun

David Colquhoun (born 19 July 1936) is a British pharmacologist at University College London (UCL). He has contributed to the general theory of receptor and synaptic mechanisms, and in particular the theory and practice of single ion channel ...

), and by students (David Conway, then a postgraduate student in the department of Hebrew and Jewish studies). The latter featured an agony uncle column by "Jeremy Bentham" to defend the College. On 18 November 2002 the merger was called off, in no small part because of revelations on those sites.

On 1 August 2003, Professor Malcolm Grant

Sir Malcolm John Grant, , (born 29 November 1947) is a barrister, academic lawyer, and former law professor. Born and educated in New Zealand, he was the ninth President and Provost of University College London – the head as well as principa ...

took the role of President and Provost (the principal of UCL), taking over from Sir Derek Roberts, who had been called out of retirement as a caretaker provost for the college, and had supported the plan for the failed merger. Shortly after Grant's inauguration, UCL began the 'Campaign for UCL' initiative, in 2004. It aimed to raise £300m from alumni and friends. This kind of explicit campaigning is traditionally unusual for UK universities, and is similar to US university funding. UCL had a financial endowment in the top ten among UK universities at £81m, according to the Sutton Trust (2002). Grant has also aimed to enhance UCL's global links, declaring UCL London's "Global University". Significant interactions with France's École Normale Supérieure

École may refer to:

* an elementary school in the French educational stages normally followed by secondary education establishments (collège and lycée)

* École (river), a tributary of the Seine flowing in région Île-de-France

* École, S ...

, Columbia University

Columbia University (also known as Columbia, and officially as Columbia University in the City of New York) is a private research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Church in Manhatt ...

, Caltech

The California Institute of Technology (branded as Caltech or CIT)The university itself only spells its short form as "Caltech"; the institution considers other spellings such a"Cal Tech" and "CalTech" incorrect. The institute is also occasional ...

, New York University

New York University (NYU) is a private research university in New York City. Chartered in 1831 by the New York State Legislature, NYU was founded by a group of New Yorkers led by then- Secretary of the Treasury Albert Gallatin.

In 1832, th ...

, University of Texas

The University of Texas at Austin (UT Austin, UT, or Texas) is a public research university in Austin, Texas. It was founded in 1883 and is the oldest institution in the University of Texas System. With 40,916 undergraduate students, 11,075 ...

, Villanova University

Villanova University is a private Roman Catholic research university in Villanova, Pennsylvania. It was founded by the Augustinians in 1842 and named after Saint Thomas of Villanova. The university is the oldest Catholic university in Penns ...

and universities in Osaka

is a designated city in the Kansai region of Honshu in Japan. It is the capital of and most populous city in Osaka Prefecture, and the third most populous city in Japan, following Special wards of Tokyo and Yokohama. With a population of ...

have developed during the first few years of his tenure as provost.

The London Centre for Nanotechnology

The London Centre for Nanotechnology is a multidisciplinary research centre in physical and biomedical nanotechnology in London, United Kingdom. It brings together three institutions that are world leaders in nanotechnology, University Colleg ...

was established in 2003 as a joint venture between UCL and Imperial College London. They were later joined by King's College London in 2018.

Since 2003, when UCL professor David Latchman became master of the neighbouring Birkbeck, he has forged closer relations between these two University of London colleges, and personally maintains departments at both. Joint research centres include the UCL/Birkbeck Institute for Earth and Planetary Sciences, the UCL/Birkbeck/ IoE Centre for Educational Neuroscience, the UCL/Birkbeck Institute of Structural and Molecular Biology, and the Birkbeck-UCL Centre for Neuroimaging.

UCL's strengths in biomedicine will be significantly augmented with the move of the National Institute for Medical Research

The National Institute for Medical Research (commonly abbreviated to NIMR), was a medical research institute based in Mill Hill, on the outskirts of north London, England. It was funded by the Medical Research Council (MRC);

In 2016, the NIMR b ...

(NIMR) from Mill Hill

Mill Hill is a suburb in the London Borough of Barnet, England. It is situated around northwest of Charing Cross. Mill Hill was in the historic county of Middlesex until 1965, when it became part of Greater London. Its population counted 18,45 ...

to UCL as preferred partner which was announced in 2006. Founded in 1913 and the Medical Research Council's first and largest laboratory, its scientists have garnered five Nobel prizes. NIMR today employs over 700 scientists and has an annual budget of £27 million. Construction of the new premises, the Francis Crick Institute, commenced in 2011; King's College London and Imperial College also became partners of the Institute.

The UCL Ear Institute

The UCL Ear Institute is an academic department of the Faculty of Brain Sciences of University College London (UCL) located in Gray's Inn Road in the Bloomsbury district of Central London, England, next to the Royal National Throat, Nose and Ear H ...

was established, with the support of a grant from the Wellcome Foundation

The Wellcome Trust is a charitable foundation focused on health research based in London, in the United Kingdom. It was established in 1936 with legacies from the pharmaceutical magnate Henry Wellcome (founder of one of the predecessors of Glax ...

, on 1 January 2005.

In 2007, Grant separated teaching from research in the Faculty of Life Sciences. In the process UCL's eminent departments of Pharmacology and Physiology vanished (see Department of Pharmacology at University College London, 1905 – 2007.

UCL applied to the Privy Council for the power to award degrees in its own right. This was granted in September 2005, and the first degrees were awarded in 2008.

In 2007, the UCL Cancer Institute was opened in the newly constructed Paul O'Gorman Building. In August 2008, UCL formed UCL Partners, an academic health science centre, with Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children NHS Trust

Great Ormond Street Hospital (informally GOSH or Great Ormond Street, formerly the Hospital for Sick Children) is a children's hospital located in the Bloomsbury area of the London Borough of Camden, and a part of Great Ormond Street Hospita ...

, Moorfields Eye Hospital NHS Foundation Trust

Moorfields Eye Hospital NHS Foundation Trust is an NHS foundation trust which runs Moorfields Eye Hospital.

The Trust employs over 1,700 people. Over 24,000 ophthalmic operations are carried out and over 300,000 patients are seen by the hospita ...

, Royal Free London NHS Foundation Trust

The Royal Free London NHS Foundation Trust (formerly the Royal Free Hampstead NHS Trust) is an NHS foundation trust based in London, United Kingdom. It comprises Royal Free Hospital, Barnet Hospital, Chase Farm Hospital, as well as clinics r ...

and University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust

University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (UCLH) is an NHS foundation trust based in London, United Kingdom. It comprises University College Hospital, University College Hospital at Westmoreland Street, the UCH Macmillan Cancer ...

. In 2008, UCL established the UCL School of Energy & Resources in Adelaide

Adelaide ( ) is the capital city of South Australia, the state's largest city and the fifth-most populous city in Australia. "Adelaide" may refer to either Greater Adelaide (including the Adelaide Hills) or the Adelaide city centre. The dem ...

, Australia, the first campus of a British university in the country. The school was based in the historic Torrens Building

The Torrens Building, named after Sir Robert Richard Torrens, is a State Heritage-listed building on the corner of Victoria Square and Wakefield Street in Adelaide, South Australia. It was originally known as the New Government Offices, and a ...

in Victoria Square and its creation followed negotiations between UCL Vice Provost Michael Worton and South Australian Premier Mike Rann.

In 2009, the Yale UCL Collaborative was established between UCL, UCL Partners, Yale University

Yale University is a Private university, private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the List of Colonial Colleges, third-oldest institution of higher education in the United Sta ...

, Yale School of Medicine

The Yale School of Medicine is the graduate medical school at Yale University, a private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. It was founded in 1810 as the Medical Institution of Yale College and formally opened in 1813.

The primary te ...

and Yale – New Haven Hospital

Yale New Haven Hospital (YNHH) is a 1,541-bed hospital located in New Haven, Connecticut. It is owned and operated by the Yale New Haven Health System. YNHH includes the 168-bed Smilow Cancer Hospital at Yale New Haven, the 201-bed Yale New Haven ...

. It is the largest collaboration in the history of either university, and its scope has subsequently been extended to the humanities and social sciences.

In October 2013, it was announced that the Translation Studies Unit of Imperial College London

Imperial College London (legally Imperial College of Science, Technology and Medicine) is a public research university in London, United Kingdom. Its history began with Prince Albert, consort of Queen Victoria, who developed his vision for a cu ...

would move to UCL, becoming part of the UCL School of European Languages, Culture and Society. In December 2013, it was announced that UCL and the academic publishing company Elsevier

Elsevier () is a Dutch academic publishing company specializing in scientific, technical, and medical content. Its products include journals such as '' The Lancet'', ''Cell'', the ScienceDirect collection of electronic journals, '' Trends'', ...

would collaborate to establish the UCL Big Data Institute. In January 2015, it was announced that UCL had been selected by the UK government as one of the five founding members of the Alan Turing Institute

The Alan Turing Institute is the United Kingdom's national institute for data science and artificial intelligence, founded in 2015 and largely funded by the UK government. It is named after Alan Turing, the British mathematician and computing ...

(together with the universities of Cambridge, Edinburgh, Oxford and Warwick), an institute to be established at the British Library to promote the development and use of advanced mathematics, computer science, algorithms and big data.

In August 2015, the Department of Management Science and Innovation was renamed as the School of Management and plans were announced to greatly expand UCL's activities in the area of business-related teaching and research. The school moved from the Bloomsbury campus to One Canada Square

One Canada Square is a skyscraper in Canary Wharf, London. It was completed in 1991 and is the third tallest building in the United Kingdom at above ground levelAviation charts issued by the Civil Aviation Authority containing 50 storeys.

On ...

in Canary Wharf in 2016.

UCL established the Institute of Advanced Studies (IAS) in 2015 to promote interdisciplinary research in humanities and social sciences. The annual Orwell Prize

The Orwell Prize, based at University College London, is a British prize for political writing. The Prize is awarded by The Orwell Foundation, an independent charity (Registered Charity No 1161563, formerly "The Orwell Prize") governed by a boa ...

for political writing moved to the IAS in 2016.

In June 2016, it was reported in ''Times Higher Education

''Times Higher Education'' (''THE''), formerly ''The Times Higher Education Supplement'' (''The Thes''), is a British magazine reporting specifically on news and issues related to higher education.

Ownership

TPG Capital acquired TSL Education ...

'' that as a result of administrative errors hundreds of students who studied at the UCL Eastman Dental Institute between 2005 and 2006 and 2013–14 had been given the wrong marks, leading to an unknown number of students being attributed with the wrong qualifications and, in some cases, being failed when they should have passed their degrees. A report by UCL's Academic Committee Review Panel noted that, according to the institute's own review findings, senior members of UCL staff had been aware of issues affecting students' results but had not taken action to address them. The Review Panel concluded that there had been an apparent lack of ownership of these matters amongst the institute's senior staff.

In December 2016, it was announced that UCL would be the hub institution for a new £250 million national dementia research institute, to be funded with £150 million from the Medical Research Council and £50 million each from Alzheimer's Research UK

Alzheimer's Research UK (ARUK) is a dementia research charity in the United Kingdom, founded in 1992 as the Alzheimer's Research Trust.

ARUK funds scientific studies to find ways to treat, cure or prevent all forms of dementia, including Alzhei ...

and the Alzheimer's Society

Alzheimer's Society is a United Kingdom care and research charity for people with dementia and their carers. It operates in England, Wales and Northern Ireland, while its sister charitieAlzheimer Scotlandand Alzheimer's Society of Ireland cover ...

.

In May 2017, it was reported that staff morale was at "an all time low", with 68% of members of the academic board who responded to a survey disagreeing with the statement "UCL is well managed" and 86% with "the teaching facilities are adequate for the number of students". Michael Arthur, the provost and president, linked the results to the "major change programme" at UCL. He admitted that facilities were under pressure following growth over the past decade, but said that the issues were being addressed through the development of UCL East and rental of other additional space.

It was announced in August 2018 that a £215 million contract for construction of the largest building in the UCL East development, Marshgate 1, had been awarded to Mace, with building planned to begin in 2019 and be completed by 2022.

Notes and references

;Notes ;ReferencesSources and further reading

* * * * * *External links

UCL

University of London

UCL History Page

World of UCL- a free book about the history of UCL

UCL site 1827 {{University College London, university History of the University of London

University College

In a number of countries, a university college is a college institution that provides tertiary education but does not have full or independent university status. A university college is often part of a larger university. The precise usage varies ...