The

history

History (derived ) is the systematic study and the documentation of the human activity. The time period of event before the invention of writing systems is considered prehistory. "History" is an umbrella term comprising past events as well ...

of

Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, ...

dates to contact the

pre-Roman peoples of the

Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on ...

coast of the

Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula (),

**

* Aragonese and Occitan: ''Peninsula Iberica''

**

**

* french: Péninsule Ibérique

* mwl, Península Eibérica

* eu, Iberiar penintsula also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in southwestern Europe, def ...

made with the

Greeks

The Greeks or Hellenes (; el, Έλληνες, ''Éllines'' ) are an ethnic group and nation indigenous to the Eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea regions, namely Greece, Cyprus, Albania, Italy, Turkey, Egypt, and, to a lesser extent, ot ...

and

Phoenicians

Phoenicia () was an ancient thalassocratic civilization originating in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily located in modern Lebanon. The territory of the Phoenician city-states extended and shrank throughout their his ...

and the first writing systems known as

Paleohispanic scripts were developed. During

Classical Antiquity

Classical antiquity (also the classical era, classical period or classical age) is the period of cultural history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD centred on the Mediterranean Sea, comprising the interlocking civilizations of ...

, the peninsula was the site of multiple successive colonizations of Greeks, Carthaginians, and Romans. Native peoples of the peninsula, such as the

Tartessos people, intermingled with the colonizers to create a uniquely Iberian culture. The Romans referred to the entire Peninsula as

Hispania

Hispania ( la, Hispānia , ; nearly identically pronounced in Spanish, Portuguese, Catalan, and Italian) was the Roman name for the Iberian Peninsula and its provinces. Under the Roman Republic, Hispania was divided into two provinces: Hi ...

, from where the modern name of Spain originates. The region was divided up, at various times, into different Roman provinces. As was the rest of the

Western Roman Empire

The Western Roman Empire comprised the western provinces of the Roman Empire at any time during which they were administered by a separate independent Imperial court; in particular, this term is used in historiography to describe the period ...

, Spain was subject to the numerous invasions of

Germanic tribes during the 4th and 5th centuries CE, resulting in the loss of Roman rule and the establishment of Germanic kingdoms, most notably the

Visigoths

The Visigoths (; la, Visigothi, Wisigothi, Vesi, Visi, Wesi, Wisi) were an early Germanic people who, along with the Ostrogoths, constituted the two major political entities of the Goths within the Roman Empire in late antiquity, or what is k ...

and the

Suebi

The Suebi (or Suebians, also spelled Suevi, Suavi) were a large group of Germanic peoples originally from the Elbe river region in what is now Germany and the Czech Republic. In the early Roman era they included many peoples with their own name ...

, marking the beginning of the

Middle Ages in Spain.

Various Germanic kingdoms were established on the Iberian peninsula in the early 5th century CE in the wake of the fall of Roman control; germanic control lasted about 200 years until the

Umayyad conquest of Hispania

The Umayyad conquest of Hispania, also known as the Umayyad conquest of the Visigothic Kingdom, was the initial expansion of the Umayyad Caliphate over Hispania (in the Iberian Peninsula) from 711 to 718. The conquest resulted in the decline of t ...

began in 711 and marked the introduction of

Islam

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God (or '' Allah'') as it was revealed to Muhammad, the ...

to the Iberian Peninsula. The region became known as

Al-Andalus

Al-Andalus translit. ; an, al-Andalus; ast, al-Ándalus; eu, al-Andalus; ber, ⴰⵏⴷⴰⵍⵓⵙ, label= Berber, translit=Andalus; ca, al-Àndalus; gl, al-Andalus; oc, Al Andalús; pt, al-Ândalus; es, al-Ándalus () was the M ...

, and excepting for the small

Kingdom of Asturias

The Kingdom of Asturias ( la, Asturum Regnum; ast, Reinu d'Asturies) was a kingdom in the Iberian Peninsula founded by the Visigothic nobleman Pelagius. It was the first Christian political entity established after the Umayyad conquest of ...

, a Christian

rump state in the north of Iberia, the region remained under the control of Muslim-lead states for much of the

Early Middle Ages

The Early Middle Ages (or early medieval period), sometimes controversially referred to as the Dark Ages, is typically regarded by historians as lasting from the late 5th or early 6th century to the 10th century. They marked the start of the Mi ...

, a period known as the

Islamic Golden Age

The Islamic Golden Age was a period of cultural, economic, and scientific flourishing in the history of Islam, traditionally dated from the 8th century to the 14th century. This period is traditionally understood to have begun during the reign ...

. By the time of the

High Middle Ages

The High Middle Ages, or High Medieval Period, was the periodization, period of European history that lasted from AD 1000 to 1300. The High Middle Ages were preceded by the Early Middle Ages and were followed by the Late Middle Ages, which ended ...

, Christians from the north gradually expanded their control over Iberia, a period known as the

Reconquista

The ' ( Spanish, Portuguese and Galician for "reconquest") is a historiographical construction describing the 781-year period in the history of the Iberian Peninsula between the Umayyad conquest of Hispania in 711 and the fall of the N ...

. As they expanded southward, a number of Christian kingdoms were formed, including the

Kingdom of Navarre

The Kingdom of Navarre (; , , , ), originally the Kingdom of Pamplona (), was a Basque kingdom that occupied lands on both sides of the western Pyrenees, alongside the Atlantic Ocean between present-day Spain and France.

The medieval state took ...

(a Basque kingdom centered on the city of

Pamplona

Pamplona (; eu, Iruña or ), historically also known as Pampeluna in English, is the capital city of the Chartered Community of Navarre, in Spain. It is also the third-largest city in the greater Basque cultural region.

Lying at near above ...

), the

Kingdom of León

The Kingdom of León; es, Reino de León; gl, Reino de León; pt, Reino de Leão; la, Regnum Legionense; mwl, Reino de Lhion was an independent kingdom situated in the northwest region of the Iberian Peninsula. It was founded in 910 when t ...

(in the northwest, originally an offshoot of, and later supplanting, the Kingdom of Asturias), the

Kingdom of Castile

The Kingdom of Castile (; es, Reino de Castilla, la, Regnum Castellae) was a large and powerful state on the Iberian Peninsula during the Middle Ages. Its name comes from the host of castles constructed in the region. It began in the 9th ce ...

(in central Iberia), and the

Kingdom of Aragon

The Kingdom of Aragon ( an, Reino d'Aragón, ca, Regne d'Aragó, la, Regnum Aragoniae, es, Reino de Aragón) was a medieval and early modern kingdom on the Iberian Peninsula, corresponding to the modern-day autonomous community of Aragon ...

(in

Catalonia

Catalonia (; ca, Catalunya ; Aranese Occitan: ''Catalonha'' ; es, Cataluña ) is an autonomous community of Spain, designated as a '' nationality'' by its Statute of Autonomy.

Most of the territory (except the Val d'Aran) lies on the no ...

and surrounding areas of Eastern Iberia). The history of these kingdoms and other are intertwined and they eventually consolidated into two roughly equivalent polities, the

Crown of Castile

The Crown of Castile was a medieval polity in the Iberian Peninsula that formed in 1230 as a result of the third and definitive union of the crowns and, some decades later, the parliaments of the kingdoms of Castile and León upon the accessi ...

and the

Crown of Aragon

The Crown of Aragon ( , ) an, Corona d'Aragón ; ca, Corona d'Aragó, , , ; es, Corona de Aragón ; la, Corona Aragonum . was a composite monarchy ruled by one king, originated by the dynastic union of the Kingdom of Aragon and the County of ...

, roughly occupying the central and eastern thirds of the Iberian Peninsula respectively. During this period, the southwestern portion of the Peninsula developed into the

Kingdom of Portugal

The Kingdom of Portugal ( la, Regnum Portugalliae, pt, Reino de Portugal) was a monarchy in the western Iberian Peninsula and the predecessor of the modern Portuguese Republic. Existing to various extents between 1139 and 1910, it was also kn ...

, and developed its own distinct national identity separate from that of Spain.

The

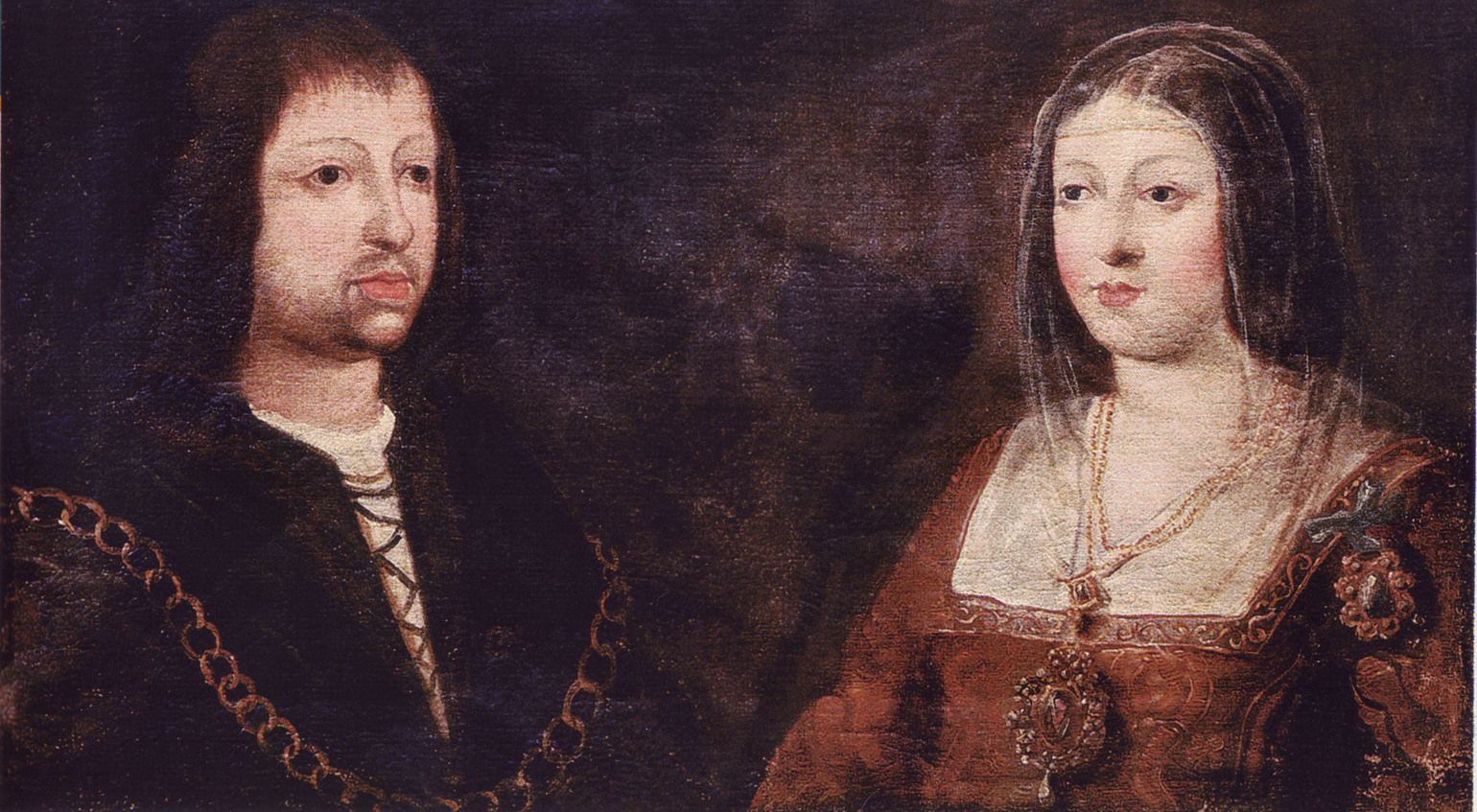

early modern period is generally dated from the union of the Crowns of Castile and Aragon under the

Catholic Monarchs,

Isabella I of Castile

Isabella I ( es, Isabel I; 22 April 1451 – 26 November 1504), also called Isabella the Catholic (Spanish: ''la Católica''), was Queen of Castile from 1474 until her death in 1504, as well as Queen consort of Aragon from 1479 until 1504 b ...

and

Ferdinand II of Aragon

Ferdinand II ( an, Ferrando; ca, Ferran; eu, Errando; it, Ferdinando; la, Ferdinandus; es, Fernando; 10 March 1452 – 23 January 1516), also called Ferdinand the Catholic (Spanish: ''el Católico''), was King of Aragon and Sardinia fro ...

in 1469. This marked what is

historiographically considered the foundation of unified Spain, although technically Castile and Aragon continued to maintain independent institutions for several centuries. The

conquest of Granada

The Granada War ( es, Guerra de Granada) was a series of military campaigns between 1482 and 1491 during the reign of the Catholic Monarchs, Isabella I of Castile and Ferdinand II of Aragon, against the Nasrid dynasty's Emirate of Granada. It ...

, and the

first voyage of Columbus, both in 1492, made that year a critical inflection point in Spanish history. The victory over Granada marked the official end of the Reconquista, as it was the last Muslim-ruled kingdom in Iberia, and the voyages of the various explorers and

Conquistadors of Spain during the subsequent decades helped establish a

Spanish colonial empire which was among the largest the world had ever seen. King

Carlos I Carlos I may refer to:

*Carlos I of Spain (1500–1558), also Charles V of the Holy Roman Empire

*Carlos I of Portugal

''Dom'' Carlos I (; English: King Charles of Portugal; 28 September 1863 – 1 February 1908), known as the Diplomat ( pt, ...

, grandson of Ferdinand and Isabella through their daughter Joanna, established the

Spanish Habsburg dynasty. It was under the rule of his son

Philip II of Spain

Philip II) in Spain, while in Portugal and his Italian kingdoms he ruled as Philip I ( pt, Filipe I). (21 May 152713 September 1598), also known as Philip the Prudent ( es, Felipe el Prudente), was King of Spain from 1556, King of Portugal from ...

that the

Spanish Golden Age

The Spanish Golden Age ( es, Siglo de Oro, links=no , "Golden Century") is a period of flourishing in arts and literature in Spain, coinciding with the political rise of the Spanish Empire under the Catholic Monarchs of Spain and the Spanish Ha ...

flourished, the Spanish Empire reached its territorial and economic peak, and his palace at

El Escorial became the center of artistic flourishing. However, Philip's rule also saw the calamitous destruction of the

Spanish Armada

The Spanish Armada (a.k.a. the Enterprise of England, es, Grande y Felicísima Armada, links=no, lit=Great and Most Fortunate Navy) was a Spanish fleet that sailed from Lisbon in late May 1588, commanded by the Duke of Medina Sidonia, an ar ...

, coupled with financial mismanagement that led to numerous state bankruptcies and independence of the

Northern Netherlands, which marked the beginning of the slow decline of Spanish influence in Europe.

Spain's power was further tested by their participation in the

Eighty Years' War

The Eighty Years' War or Dutch Revolt ( nl, Nederlandse Opstand) ( c.1566/1568–1648) was an armed conflict in the Habsburg Netherlands between disparate groups of rebels and the Spanish government. The causes of the war included the Ref ...

, whereby they tried and failed to recapture the newly independent Dutch Republic, and the

Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War was one of the longest and most destructive conflicts in European history, lasting from 1618 to 1648. Fought primarily in Central Europe, an estimated 4.5 to 8 million soldiers and civilians died as a result of batt ...

, which resulted in continued decline of Habsburg power in favor of French

Bourbon dynasty

The House of Bourbon (, also ; ) is a European dynasty of French origin, a branch of the Capetian dynasty, the royal House of France. Bourbon kings first ruled France and Navarre in the 16th century. By the 18th century, members of the Spanis ...

. Matters came to a head during the reign of

Charles II of Spain

Charles II of Spain (''Spanish: Carlos II,'' 6 November 1661 – 1 November 1700), known as the Bewitched (''Spanish: El Hechizado''), was the last Habsburg ruler of the Spanish Empire. Best remembered for his physical disabilities and the War ...

, whose mental incapacity and inability to father children left the future of Spain in doubt. Upon his death, the

War of the Spanish Succession

The War of the Spanish Succession was a European great power conflict that took place from 1701 to 1714. The death of childless Charles II of Spain in November 1700 led to a struggle for control of the Spanish Empire between his heirs, Phil ...

broke out between the French Bourbons and the Austrian Habsburgs over the right to succeed Charles II. The Bourbons prevailed, resulting in the ascension of

Philip V of Spain

Philip V ( es, Felipe; 19 December 1683 – 9 July 1746) was King of Spain from 1 November 1700 to 14 January 1724, and again from 6 September 1724 to his death in 1746. His total reign of 45 years is the longest in the history of the Spanish mo ...

. Though himself a French prince, Philip quickly established himself as his own person, taking Spain into the various wars to recapture the Spanish-controlled lands in Southern Italy recently lost. Spain's apparent resurgence was cut short by losses during the

Napoleonic era

The Napoleonic era is a period in the history of France and Europe. It is generally classified as including the fourth and final stage of the French Revolution, the first being the National Assembly, the second being the Legislativ ...

, when Napoleon placed his own brother,

Joseph Bonaparte

it, Giuseppe-Napoleone Buonaparte es, José Napoleón Bonaparte

, house = Bonaparte

, father = Carlo Buonaparte

, mother = Letizia Ramolino

, birth_date = 7 January 1768

, birth_place = Corte, Corsica, Republic ...

, as King of Spain, turning it into a French puppet state. Concurrent with, and following, the Napoleonic period the

Spanish American wars of independence

The Spanish American wars of independence (25 September 1808 – 29 September 1833; es, Guerras de independencia hispanoamericanas) were numerous wars in Spanish America with the aim of political independence from Spanish rule during the early ...

resulted in the loss of most of Spain's territory in the Americas. During the re-establishment of the Bourbon rule in Spain,

constitutional monarchy

A constitutional monarchy, parliamentary monarchy, or democratic monarchy is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in decision making. Constitutional monarchies dif ...

was introduced in 1813. As with much of Europe, Spain's history during the nineteenth century was tumultuous, and featured alternating periods of republican-liberal and monarchical rule.

The twentieth century began for Spain in foreign and domestic turmoil; the

Spanish-American War led to losses of Spanish colonial possessions and a series of military dictatorships, first under

Miguel Primo de Rivera and secondly under

Dámaso Berenguer

Dámaso Berenguer y Fusté, 1st Count of Xauen (4 August 1873 – 19 May 1953) was a Spanish general and politician. He served as Prime Minister of Spain, Prime Minister during the last thirteen months of the reign of Alfonso XIII.

Biography

...

. During Berenguer's dictatorship, the king,

Alfonso XIII was deposed and a

new Republican government was formed. Ultimately, the political disorder within Spain led to a coup by the military which led to the

Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlism, Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebeli ...

, in which the Republican forces squared off against the

Nationalist

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: Th ...

s. After much foreign intervention on both sides, the Nationalists emerged victorious thanks to the help provided by Nazi Germany and Italy, their leader

Francisco Franco

Francisco Franco Bahamonde (; 4 December 1892 – 20 November 1975) was a Spanish general who led the Nationalist forces in overthrowing the Second Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil War and thereafter ruled over Spain from 193 ...

, who led a fascist dictatorship for almost four decades. Francisco's death ushered in a return of the monarchy King

Juan Carlos I

Juan Carlos I (;,

* ca, Joan Carles I,

* gl, Xoán Carlos I, Juan Carlos Alfonso Víctor María de Borbón y Borbón-Dos Sicilias, born 5 January 1938) is a member of the Spanish royal family who reigned as King of Spain from 22 Novem ...

, which saw a liberalization of Spanish society and a re-engagement with the international community after the oppressive and isolated years under Franco. A new liberal

Constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When these pr ...

was established in 1978. Spain entered the

European Economic Community

The European Economic Community (EEC) was a regional organization created by the Treaty of Rome of 1957,Today the largely rewritten treaty continues in force as the ''Treaty on the functioning of the European Union'', as renamed by the Lis ...

in 1986 (transformed into the

European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational union, supranational political union, political and economic union of Member state of the European Union, member states that are located primarily in Europe, Europe. The union has a total area of ...

with the

Maastricht Treaty

The Treaty on European Union, commonly known as the Maastricht Treaty, is the foundation treaty of the European Union (EU). Concluded in 1992 between the then-twelve member states of the European Communities, it announced "a new stage in the ...

of 1992), and the

Eurozone

The euro area, commonly called eurozone (EZ), is a currency union of 19 member states of the European Union (EU) that have adopted the euro (€) as their primary currency and sole legal tender, and have thus fully implemented EMU pol ...

in 1998. Juan Carlos abdicated in 2014, and was succeeded by his son

Felipe VI

Felipe VI (;,

* eu, Felipe VI.a,

* ca, Felip VI,

* gl, Filipe VI, . Felipe Juan Pablo Alfonso de Todos los Santos de Borbón y Grecia; born 30 January 1968) is King of Spain. He is the son of former King Juan Carlos I and Queen Sofía, an ...

, the current king.

Prehistory

The earliest record of

hominids living in Western Europe has been found in the Spanish cave of

Atapuerca; a flint tool found there dates from 1.4 million years ago, and early human

fossils

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

date to roughly 1.2 million years ago.

Modern humans in the form of

Cro-Magnon

Early European modern humans (EEMH), or Cro-Magnons, were the first early modern humans (''Homo sapiens'') to settle in Europe, migrating from Western Asia, continuously occupying the continent possibly from as early as 56,800 years ago. They i ...

s began arriving in the Iberian Peninsula from north of the

Pyrenees

The Pyrenees (; es, Pirineos ; french: Pyrénées ; ca, Pirineu ; eu, Pirinioak ; oc, Pirenèus ; an, Pirineus) is a mountain range straddling the border of France and Spain. It extends nearly from its union with the Cantabrian Mountains to ...

some 35,000 years ago. The most conspicuous sign of prehistoric human settlements are the famous

paintings in the northern Spanish cave of

Altamira

Altamira may refer to:

People

*Altamira (surname)

Places

* Cave of Altamira, a cave in Cantabria, Spain famous for its paintings and carving

*Altamira, Pará, a city in the Brazilian state of Pará

* Altamira, Huila, a town and municipality in ...

, which were done c. 15,000

BC and are regarded as paramount instances of

cave art

In archaeology, Cave paintings are a type of parietal art (which category also includes petroglyphs, or engravings), found on the wall or ceilings of caves. The term usually implies prehistoric origin, and the oldest known are more than 40,000 ye ...

.

Archeological evidence in places like

Los Millares and

El Argar, both in the

province of Almería

Almería (, also , ) is a province of the autonomous community of Andalusia, Spain. It is bordered by the provinces of Granada, Murcia, and the Mediterranean Sea. Its capital is the homonymous city of Almería.

Almería has an area of . With 701, ...

, and La Almoloya near

Murcia suggests developed cultures existed in the eastern part of the Iberian Peninsula during the late

Neolithic

The Neolithic period, or New Stone Age, is an Old World archaeological period and the final division of the Stone Age. It saw the Neolithic Revolution, a wide-ranging set of developments that appear to have arisen independently in several pa ...

and the

Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second pri ...

.

Around 2500 BC, the nomadic shepherds known as the

Yamna or

Pit Grave culture conquered the peninsula using new technologies and horses while killing all local males according to DNA studies. Spanish prehistory extends to the pre-Roman

Iron Age

The Iron Age is the final epoch of the three-age division of the prehistory and protohistory of humanity. It was preceded by the Stone Age ( Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic) and the Bronze Age ( Chalcolithic). The concept has been mostly ...

cultures that controlled most of

Iberia

The Iberian Peninsula (),

**

* Aragonese language, Aragonese and Occitan language, Occitan: ''Peninsula Iberica''

**

**

* french: Péninsule Ibérique

* mwl, Península Eibérica

* eu, Iberiar penintsula also known as Iberia, is a pe ...

: those of the

Iberians

The Iberians ( la, Hibērī, from el, Ἴβηρες, ''Iberes'') were an ancient people settled in the eastern and southern coasts of the Iberian peninsula, at least from the 6th century BC. They are described in Greek and Roman sources (amon ...

,

Celtiberians

The Celtiberians were a group of Celts and Celticized peoples inhabiting an area in the central-northeastern Iberian Peninsula during the final centuries BCE. They were explicitly mentioned as being Celts by several classic authors (e.g. Strab ...

,

Tartessians

Tartessos ( es, Tarteso) is, as defined by archaeological discoveries, a historical civilization settled in the region of Southern Spain characterized by its mixture of local Paleohispanic and Phoenician traits. It had a proper writing system ...

,

Lusitanians, and

Vascones

The Vascones were a pre-Roman tribe who, on the arrival of the Romans in the 1st century, inhabited a territory that spanned between the upper course of the Ebro river and the southern basin of the western Pyrenees, a region that coincides wi ...

and trading settlements of

Phoenicia

Phoenicia () was an ancient thalassocratic civilization originating in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily located in modern Lebanon. The territory of the Phoenician city-states extended and shrank throughout their his ...

ns,

Carthaginians

The Punic people, or western Phoenicians, were a Semitic people in the Western Mediterranean who migrated from Tyre, Phoenicia to North Africa during the Early Iron Age. In modern scholarship, the term ''Punic'' – the Latin equivalent of the ...

, and

Greeks

The Greeks or Hellenes (; el, Έλληνες, ''Éllines'' ) are an ethnic group and nation indigenous to the Eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea regions, namely Greece, Cyprus, Albania, Italy, Turkey, Egypt, and, to a lesser extent, ot ...

on the

Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on ...

coast.

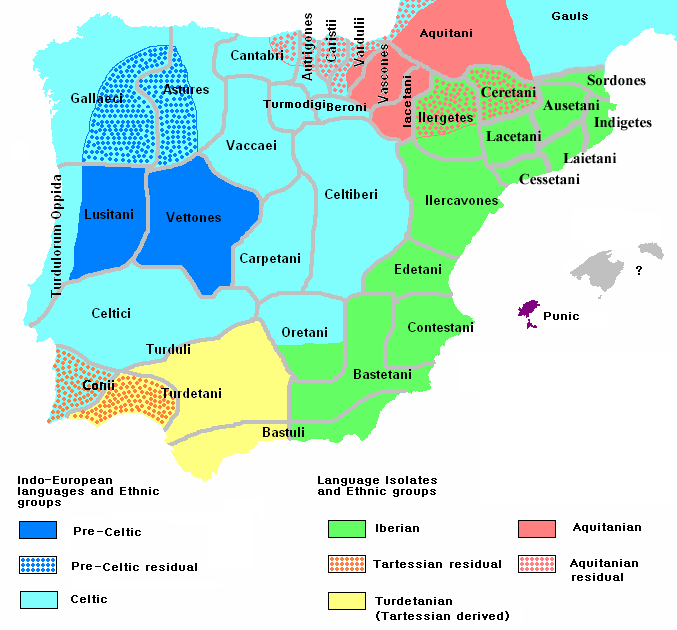

Early history of the Iberian Peninsula

Before the

Roman conquest the major cultures along the Mediterranean coast were the

Iberians

The Iberians ( la, Hibērī, from el, Ἴβηρες, ''Iberes'') were an ancient people settled in the eastern and southern coasts of the Iberian peninsula, at least from the 6th century BC. They are described in Greek and Roman sources (amon ...

, the

Celts

The Celts (, see pronunciation for different usages) or Celtic peoples () are. "CELTS location: Greater Europe time period: Second millennium B.C.E. to present ancestry: Celtic a collection of Indo-European peoples. "The Celts, an ancient ...

in the interior and north-west, the

Lusitanians in the west, and the

Tartessians

Tartessos ( es, Tarteso) is, as defined by archaeological discoveries, a historical civilization settled in the region of Southern Spain characterized by its mixture of local Paleohispanic and Phoenician traits. It had a proper writing system ...

in the southwest. The seafaring Phoenicians, Carthaginians, and Greeks successively established trading settlements along the eastern and southern coast. The development of writing in the peninsula (the so-called

paleohispanic script

The Paleohispanic scripts are the writing systems created in the Iberian peninsula before the Latin alphabet became the main script. Most of them are unusual in that they are semi-syllabic rather than purely alphabetic, despite having s ...

s) should have taken place after the arrival of early Phoenician settlers and traders (tentatively dated 9th century BC or sometime later).

The south of the peninsula was rich in archaic Phoenician colonies, unmatched by any other region in the central-western Mediterranean. They were small and densely packed settlements. The colony of

Gadir—which sustained strong links with its metropolis of

Tyre—stood out from the rest of the network of colonies, also featuring a more complex sociopolitical organization.

Archaic Greeks arrived to the Peninsula by the late 7th century BC. They founded

Greek colonies such as

Emporion (570 BC).

The Greeks are responsible for the name ''Iberia'', apparently after the river Iber (

Ebro

, name_etymology =

, image = Zaragoza shel.JPG

, image_size =

, image_caption = The Ebro River in Zaragoza

, map = SpainEbroBasin.png

, map_size =

, map_caption = The Ebro ...

). By the 6th century BC, much of the territory of southern Iberia passed to

Carthage

Carthage was the capital city of Ancient Carthage, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the classi ...

's overarching influence (featuring two centres of Punic influence in ''Gadir'' and ''Mastia''); the latter grip strengthened from the 4th century BC on. The

Barcids, following their landing in Gadir in 237 BC, militarily conquered the territories that had already belonged to the sphere of influence of Carthage. Up until 219 BC, their presence in the peninsula was underpinned by their control of places such as

Carthago Nova and Akra Leuké (both founded by Punics), as well as the network of old Phoenician settlements.

The peninsula was one of the military theatres of the

Second Punic War

The Second Punic War (218 to 201 BC) was the second of three wars fought between Carthage and Rome, the two main powers of the western Mediterranean in the 3rd century BC. For 17 years the two states struggled for supremacy, primarily in Ital ...

(218–201 BC) waged between Carthage and the

Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( la, Res publica Romana ) was a form of government of Rome and the era of the classical Roman civilization when it was run through public representation of the Roman people. Beginning with the overthrow of the Roman Ki ...

, the two powers vying for supremacy in the western mediterranean. Romans expelled Carthaginians from the peninsula in 206 BC.

The peoples whom the

Romans met at the time of their invasion in what is now known as Spain were the Iberians, inhabiting an area stretching from the northeast part of the Iberian Peninsula through the southeast. The Celts mostly inhabited the inner and north-west part of the peninsula. To the east of the

Meseta Central, the

Sistema Ibérico area was inhabited by the

Celtiberians

The Celtiberians were a group of Celts and Celticized peoples inhabiting an area in the central-northeastern Iberian Peninsula during the final centuries BCE. They were explicitly mentioned as being Celts by several classic authors (e.g. Strab ...

, reportedly rich in

precious metal

Precious metals are rare, naturally occurring metallic chemical elements of high economic value.

Chemically, the precious metals tend to be less reactive than most elements (see noble metal). They are usually ductile and have a high lu ...

s (which were obtained by Romans in the form of

tribute

A tribute (; from Latin ''tributum'', "contribution") is wealth, often in kind, that a party gives to another as a sign of submission, allegiance or respect. Various ancient states exacted tribute from the rulers of land which the state conq ...

s). Celtiberians developed a refined technique of iron-forging, displayed, for example, in their quality weapons.

The

Celtiberian Wars were fought between the advancing

legions of the Roman Republic and the Celtiberian tribes of Hispania Citerior from 181 to 133 BC. The Roman conquest of the peninsula was completed in 19 BC.

Roman Hispania (2nd century BC – 5th century AD)

''

Hispania

Hispania ( la, Hispānia , ; nearly identically pronounced in Spanish, Portuguese, Catalan, and Italian) was the Roman name for the Iberian Peninsula and its provinces. Under the Roman Republic, Hispania was divided into two provinces: Hi ...

'' was the name used for the Iberian Peninsula under

Roman rule from the 2nd century BC. The populations of the peninsula were gradually culturally

Romanized

Romanization or romanisation, in linguistics, is the conversion of text from a different writing system to the Roman (Latin) script, or a system for doing so. Methods of romanization include transliteration, for representing written text, and ...

, and local leaders were admitted into the Roman aristocratic class.

The Romans improved existing cities, such as

Tarragona

Tarragona (, ; Phoenician: ''Tarqon''; la, Tarraco) is a port city located in northeast Spain on the Costa Daurada by the Mediterranean Sea. Founded before the fifth century BC, it is the capital of the Province of Tarragona, and part of Tarr ...

(''Tarraco''), and established others like

Zaragoza

Zaragoza, also known in English as Saragossa,''Encyclopædia Britannica'"Zaragoza (conventional Saragossa)" is the capital city of the Province of Zaragoza, Zaragoza Province and of the autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Ara ...

(''Caesaraugusta''),

Mérida (''Augusta Emerita''),

Valencia

Valencia ( va, València) is the capital of the autonomous community of Valencia and the third-most populated municipality in Spain, with 791,413 inhabitants. It is also the capital of the province of the same name. The wider urban area al ...

(''Valentia''),

León ("Legio Septima"),

Badajoz

Badajoz (; formerly written ''Badajos'' in English) is the capital of the Province of Badajoz in the autonomous community of Extremadura, Spain. It is situated close to the Portuguese border, on the left bank of the river Guadiana. The populati ...

("Pax Augusta"), and

Palencia. The peninsula's economy expanded under Roman tutelage. Hispania supplied Rome with food, olive oil, wine and metal. The emperors

Trajan

Trajan ( ; la, Caesar Nerva Traianus; 18 September 539/11 August 117) was Roman emperor from 98 to 117. Officially declared ''optimus princeps'' ("best ruler") by the senate, Trajan is remembered as a successful soldier-emperor who presi ...

,

Hadrian

Hadrian (; la, Caesar Trâiānus Hadriānus ; 24 January 76 – 10 July 138) was Roman emperor from 117 to 138. He was born in Italica (close to modern Santiponce in Spain), a Roman ''municipium'' founded by Italic settlers in Hispania ...

, and

Theodosius I

Theodosius I ( grc-gre, Θεοδόσιος ; 11 January 347 – 17 January 395), also called Theodosius the Great, was Roman emperor from 379 to 395. During his reign, he succeeded in a crucial war against the Goths, as well as in two ...

, the philosopher

Seneca, and the poets

Martial

Marcus Valerius Martialis (known in English as Martial ; March, between 38 and 41 AD – between 102 and 104 AD) was a Roman poet from Hispania (modern Spain) best known for his twelve books of ''Epigrams'', published in Rome between AD 86 and ...

,

Quintilian

Marcus Fabius Quintilianus (; 35 – 100 AD) was a Roman educator and rhetorician from Hispania, widely referred to in medieval schools of rhetoric and in Renaissance writing. In English translation, he is usually referred to as Quintilia ...

, and

Lucan

Marcus Annaeus Lucanus (3 November 39 AD – 30 April 65 AD), better known in English as Lucan (), was a Roman poet, born in Corduba (modern-day Córdoba), in Hispania Baetica. He is regarded as one of the outstanding figures of the Imperial ...

were born in Hispania. Hispanic bishops held the

Council of Elvira around 306.

After the fall of the

Western Roman Empire

The Western Roman Empire comprised the western provinces of the Roman Empire at any time during which they were administered by a separate independent Imperial court; in particular, this term is used in historiography to describe the period ...

in the 5th century, parts of Hispania came under the control of the Germanic tribes of

Vandals

The Vandals were a Germanic peoples, Germanic people who first inhabited what is now southern Poland. They established Vandal Kingdom, Vandal kingdoms on the Iberian Peninsula, Mediterranean islands, and North Africa in the fifth century.

The ...

,

Suebi

The Suebi (or Suebians, also spelled Suevi, Suavi) were a large group of Germanic peoples originally from the Elbe river region in what is now Germany and the Czech Republic. In the early Roman era they included many peoples with their own name ...

, and

Visigoths

The Visigoths (; la, Visigothi, Wisigothi, Vesi, Visi, Wesi, Wisi) were an early Germanic people who, along with the Ostrogoths, constituted the two major political entities of the Goths within the Roman Empire in late antiquity, or what is k ...

.

The collapse of the

Western Roman Empire

The Western Roman Empire comprised the western provinces of the Roman Empire at any time during which they were administered by a separate independent Imperial court; in particular, this term is used in historiography to describe the period ...

did not lead to the same wholesale destruction of Western classical society as happened in areas like

Roman Britain

Roman Britain was the period in classical antiquity when large parts of the island of Great Britain were under occupation by the Roman Empire. The occupation lasted from AD 43 to AD 410. During that time, the territory conquered wa ...

,

Gaul

Gaul ( la, Gallia) was a region of Western Europe first described by the Romans. It was inhabited by Celtic and Aquitani tribes, encompassing present-day France, Belgium, Luxembourg, most of Switzerland, parts of Northern Italy (only during ...

and

Germania Inferior during the

Early Middle Ages

The Early Middle Ages (or early medieval period), sometimes controversially referred to as the Dark Ages, is typically regarded by historians as lasting from the late 5th or early 6th century to the 10th century. They marked the start of the Mi ...

, although the institutions and infrastructure did decline. Spain's present languages, its religion, and the basis of its laws originate from this period. The centuries of uninterrupted Roman rule and settlement left a deep and enduring imprint upon the culture of Spain.

Gothic Hispania (5th–8th centuries)

The first

Germanic tribes to invade Hispania arrived in the 5th century, as the

Roman Empire decayed.The

Visigoths

The Visigoths (; la, Visigothi, Wisigothi, Vesi, Visi, Wesi, Wisi) were an early Germanic people who, along with the Ostrogoths, constituted the two major political entities of the Goths within the Roman Empire in late antiquity, or what is k ...

,

Suebi

The Suebi (or Suebians, also spelled Suevi, Suavi) were a large group of Germanic peoples originally from the Elbe river region in what is now Germany and the Czech Republic. In the early Roman era they included many peoples with their own name ...

,

Vandals

The Vandals were a Germanic peoples, Germanic people who first inhabited what is now southern Poland. They established Vandal Kingdom, Vandal kingdoms on the Iberian Peninsula, Mediterranean islands, and North Africa in the fifth century.

The ...

and

Alans arrived in Hispania by crossing the Pyrenees mountain range, leading to the establishment of the

Suebi Kingdom

The Kingdom of the Suebi ( la, Regnum Suevorum), also called the Kingdom of Galicia ( la, Regnum Galicia) or Suebi Kingdom of Galicia ( la, Galicia suevorum regnum), was a Germanic post-Roman kingdom that was one of the first to separate from ...

in

Gallaecia

Gallaecia, also known as Hispania Gallaecia, was the name of a Roman province in the north-west of Hispania, approximately present-day Galicia (Spain), Galicia, Norte, Portugal, northern Portugal, Asturias and León (province), Leon and the lat ...

, in the northwest, the

Vandal Kingdom of Vandalusia (Andalusia), and finally the

Visigothic Kingdom

The Visigothic Kingdom, officially the Kingdom of the Goths ( la, Regnum Gothorum), was a kingdom that occupied what is now southwestern France and the Iberian Peninsula from the 5th to the 8th centuries. One of the Germanic successor states to ...

in Toledo. The

Romanized

Romanization or romanisation, in linguistics, is the conversion of text from a different writing system to the Roman (Latin) script, or a system for doing so. Methods of romanization include transliteration, for representing written text, and ...

Visigoths entered Hispania in 415. After the conversion of their monarchy to

Roman Catholicism

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

and after conquering the disordered Suebic territories in the northwest and

Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

territories in the southeast, the Visigothic Kingdom eventually encompassed a great part of the Iberian Peninsula.

As the

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Roman Republic, Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings aro ...

declined,

Germanic tribes invaded the former empire. Some were ''

foederati

''Foederati'' (, singular: ''foederatus'' ) were peoples and cities bound by a treaty, known as ''foedus'', with Rome. During the Roman Republic, the term identified the ''socii'', but during the Roman Empire, it was used to describe foreign stat ...

'', tribes enlisted to serve in Roman armies, and given land within the empire as payment, while others, such as the

Vandals

The Vandals were a Germanic peoples, Germanic people who first inhabited what is now southern Poland. They established Vandal Kingdom, Vandal kingdoms on the Iberian Peninsula, Mediterranean islands, and North Africa in the fifth century.

The ...

, took advantage of the empire's weakening defenses to seek plunder within its borders. Those tribes that survived took over existing Roman institutions, and created successor-kingdoms to the Romans in various parts of Europe. Hispania was taken over by the

Visigoths

The Visigoths (; la, Visigothi, Wisigothi, Vesi, Visi, Wesi, Wisi) were an early Germanic people who, along with the Ostrogoths, constituted the two major political entities of the Goths within the Roman Empire in late antiquity, or what is k ...

after 410.

At the same time, there was a process of "Romanization" of the Germanic and

Hunnic tribes settled on both sides of the ''

limes

Limes may refer to:

* the plural form of lime (disambiguation)

Lime commonly refers to:

* Lime (fruit), a green citrus fruit

* Lime (material), inorganic materials containing calcium, usually calcium oxide or calcium hydroxide

* Lime (color), a ...

'' (the fortified frontier of the Empire along the

Rhine

), Surselva, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source1_coordinates=

, source1_elevation =

, source2 = Rein Posteriur/Hinterrhein

, source2_location = Paradies Glacier, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source2_coordinates=

, source ...

and

Danube

The Danube ( ; ) is a river that was once a long-standing frontier of the Roman Empire and today connects 10 European countries, running through their territories or being a border. Originating in Germany, the Danube flows southeast for , pa ...

rivers). The Visigoths, for example, were converted to

Arian Christianity

Arianism ( grc-x-koine, Ἀρειανισμός, ) is a Christological doctrine first attributed to Arius (), a Christian presbyter from Alexandria, Egypt. Arian theology holds that Jesus Christ is the Son of God, who was begotten by God t ...

around 360, even before they were pushed into imperial territory by the expansion of the

Huns

The Huns were a nomadic people who lived in Central Asia, the Caucasus, and Eastern Europe between the 4th and 6th century AD. According to European tradition, they were first reported living east of the Volga River, in an area that was part ...

.

In the winter of 406, taking advantage of the frozen Rhine, refugees from (

Germanic)

Vandals

The Vandals were a Germanic peoples, Germanic people who first inhabited what is now southern Poland. They established Vandal Kingdom, Vandal kingdoms on the Iberian Peninsula, Mediterranean islands, and North Africa in the fifth century.

The ...

and

Sueves, and the (

Sarmatian)

Alans, fleeing the advancing Huns, invaded the empire in force.

The Visigoths, having

sacked Rome two years earlier, arrived in Gaul in 412, founding the Visigothic kingdom of

Toulouse

Toulouse ( , ; oc, Tolosa ) is the prefecture of the French department of Haute-Garonne and of the larger region of Occitania. The city is on the banks of the River Garonne, from the Mediterranean Sea, from the Atlantic Ocean and fr ...

(in the south of modern France) and gradually expanded their influence into Hispania after the battle of Vouillé (507) at the expense of the Vandals and Alans, who moved on into North Africa without leaving much permanent mark on Hispanic culture. The

Visigothic Kingdom

The Visigothic Kingdom, officially the Kingdom of the Goths ( la, Regnum Gothorum), was a kingdom that occupied what is now southwestern France and the Iberian Peninsula from the 5th to the 8th centuries. One of the Germanic successor states to ...

shifted its capital to

Toledo and reached a high point during the reign of

Leovigild.

Visigothic rule

The

Visigothic Kingdom

The Visigothic Kingdom, officially the Kingdom of the Goths ( la, Regnum Gothorum), was a kingdom that occupied what is now southwestern France and the Iberian Peninsula from the 5th to the 8th centuries. One of the Germanic successor states to ...

conquered all of Hispania and ruled it until the early 8th century, when the peninsula fell to the

Muslim conquests. The Muslim state in Hispania came to be known as

Al-Andalus

Al-Andalus translit. ; an, al-Andalus; ast, al-Ándalus; eu, al-Andalus; ber, ⴰⵏⴷⴰⵍⵓⵙ, label= Berber, translit=Andalus; ca, al-Àndalus; gl, al-Andalus; oc, Al Andalús; pt, al-Ândalus; es, al-Ándalus () was the M ...

. After a period of Muslim dominance, the

medieval history of Spain is dominated by the long Christian ''

Reconquista

The ' ( Spanish, Portuguese and Galician for "reconquest") is a historiographical construction describing the 781-year period in the history of the Iberian Peninsula between the Umayyad conquest of Hispania in 711 and the fall of the N ...

'' or "reconquest" of the Iberian Peninsula from Muslim rule. The Reconquista gathered momentum during the 12th century, leading to the establishment of the Christian kingdoms of

Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, República Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of th ...

,

Aragon

Aragon ( , ; Spanish and an, Aragón ; ca, Aragó ) is an autonomous community in Spain, coextensive with the medieval Kingdom of Aragon. In northeastern Spain, the Aragonese autonomous community comprises three provinces (from north to s ...

,

Castile and

Navarre

Navarre (; es, Navarra ; eu, Nafarroa ), officially the Chartered Community of Navarre ( es, Comunidad Foral de Navarra, links=no ; eu, Nafarroako Foru Komunitatea, links=no ), is a foral autonomous community and province in northern Spain, ...

and by 1250, had reduced Muslim control to the

Emirate of Granada

)

, common_languages = Official language: Classical ArabicOther languages: Andalusi Arabic, Mozarabic, Berber, Ladino

, capital = Granada

, religion = Majority religion: Sunni IslamMinority religions:R ...

in the south-east of the peninsula. Muslim rule in Granada survived until 1492, when it fell to the

Catholic Monarchs.

Hispania never saw a decline in interest in classical culture to the degree observable in Britain, Gaul, Lombardy and Germany. The Visigoths, having assimilated Roman culture and its language during their tenure as ''foederati'', tended to maintain more of the old Roman institutions, and they had a unique respect for legal codes that resulted in continuous frameworks and historical records for most of the period between 415, when Visigothic rule in Hispania began, and 711 when it is traditionally said to end.chap The

''Liber Iudiciorum'' or Lex Visigothorum (654), also known as the Book of Judges, which

Recceswinth promulgated, based on Roman law and Germanic customary laws, brought about legal unification by applying it to the entire population both Goths and Hispano-Romans. According to the historian Joseph F. O'Callaghan, at that time they already considered themselves one people, the process of population unification had been completed, and together with the Hispano-Gothic nobility they called themselves the ''gens Gothorum''.

In the early Middle Ages, the ''Liber Iudiciorum'' was known as the Visigothic Code and also as the ''

Fuero Juzgo The ''Fuero Juzgo'' () was a codex of Spanish laws enacted in Castile in 1241 by Fernando III. It is essentially a translation of the ''Liber Iudiciorum'' that was formulated in 654 by the Visigoths.

The ''Fuero Juzgo'' was first applied legally ...

''. Its influence on law extends to the present day.

The proximity of the Visigothic kingdoms to the Mediterranean and the continuity of western Mediterranean trade, though in reduced quantity, supported Visigothic culture. The Visigothic ruling class looked to

Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

for style and technology.

Spanish Catholic religion also coalesced during this time. The period of rule by the

Visigothic Kingdom

The Visigothic Kingdom, officially the Kingdom of the Goths ( la, Regnum Gothorum), was a kingdom that occupied what is now southwestern France and the Iberian Peninsula from the 5th to the 8th centuries. One of the Germanic successor states to ...

saw the spread of

Arianism

Arianism ( grc-x-koine, Ἀρειανισμός, ) is a Christological doctrine first attributed to Arius (), a Christian presbyter from Alexandria, Egypt. Arian theology holds that Jesus Christ is the Son of God, who was begotten by God ...

briefly in Hispania. The

Councils of Toledo

From the 5th century to the 7th century AD, about thirty synods, variously counted, were held at Toledo (''Concilia toletana'') in what would come to be part of Spain. The earliest, directed against Priscillianism, assembled in 400. The "thir ...

debated creed and liturgy in orthodox

Catholicism

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

, and the Council of Lerida in 546 constrained the clergy and extended the power of law over them with the approval of the Pope. In 587, the Visigothic king at Toledo,

Reccared, converted to Catholicism and launched a movement in Hispania to unify the various religious doctrines that existed in the land. This put an end to dissension on the question of Arianism.

The Visigoths inherited from Late Antiquity a sort of

prefeudal system in Hispania,

based in the south on the Roman

villa

A villa is a type of house that was originally an ancient Roman upper class country house. Since its origins in the Roman villa, the idea and function of a villa have evolved considerably. After the fall of the Roman Republic, villas became ...

system and in the north drawing on their vassals to supply troops in exchange for protection. The bulk of the Visigothic army was composed of slaves, raised from the countryside. The loose council of nobles that advised Hispania's Visigothic kings and legitimized their rule was responsible for raising the army, and only upon its consent was the king able to summon soldiers.

The economy of the Visigothic kingdom depended primarily on agriculture and animal husbandry; there is little evidence of Visigothic commerce and industry.

The native Hispani maintained the cultural and economic life of Hispania, such as it was, and they were responsible for the relatively prosperous times in the 6th and 7th centuries. Administrative affairs in society were still based on Roman law, and only gradually did Visigothic customs and Roman common law merge.

The Visigoths did not, until the period of Muslim rule, intermarry with the Spanish population, preferring to remain separate, and the Visigothic language left only the faintest mark on the modern languages of Iberia. The historian Joseph F. O'Callaghan says in his book, ''A History of Medieval Spain'', that at the end of the Visigothic era the assimilation of Hispano-Romans and Visigoths was occurring rapidly, and the leaders of society were beginning to see themselves as one people. The old differences were disappearing, there was no longer a separate people, nor a divided nobility.

Little literature in the Gothic language remains from the period of Visigothic rule—only translations of parts of the Greek Bible and a few fragments of other documents have survived.

The Hispano-Romans found Visigothic rule and its early embrace of the Arian heresy more of a threat than Islam, and shed their thralldom to the Visigoths only in the 8th century, with the aid of the Muslims themselves.

The most visible effect of Visigothic rule was the depopulation of the cities as their inhabitanats moved to the countryside. Even while the country enjoyed a degree of prosperity when compared to France and Germany, where the people suffered famines during this period, the Visigoths felt little reason to contribute to the welfare, permanency, and infrastructure of their people and state. This contributed to their downfall, as they could not count on the loyalty of their subjects when the

Moors

The term Moor, derived from the ancient Mauri, is an exonym first used by Christian Europeans to designate the Muslim inhabitants of the Maghreb, the Iberian Peninsula, Sicily and Malta during the Middle Ages.

Moors are not a distinc ...

arrived in the 8th century.

Goldsmithery in Visigothic Hispania

In Spain, an important collection of Visigothic metalwork was found in

Guadamur, in the

Province of Toledo

Toledo is a province of central Spain, in the western part of the autonomous community of Castile–La Mancha. It is bordered by the provinces of Madrid, Cuenca, Ciudad Real, Badajoz, Cáceres, and Ávila. Its capital is the city of Toledo.

...

, known as the

Treasure of Guarrazar

The Treasure of Guarrazar, Guadamur, Province of Toledo, Castile-La Mancha, Spain, is an archeological find composed of twenty-six votive crowns and gold crosses that had originally been offered to the Roman Catholic Church by the Kings ...

. This

archeological

Archaeology or archeology is the scientific study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of artifacts, architecture, biofacts or ecofacts, sites, and cultural landsca ...

find is composed of twenty-six

votive crown

A votive crown is a votive offering in the form of a crown, normally in precious metals and often adorned with jewels. Especially in the Early Middle Ages, they are of a special form, designed to be suspended by chains at an altar, shrine or im ...

s and gold

cross

A cross is a geometrical figure consisting of two intersecting lines or bars, usually perpendicular to each other. The lines usually run vertically and horizontally. A cross of oblique lines, in the shape of the Latin letter X, is termed a s ...

es from the royal workshop in Toledo, with signs of Byzantine influence.

* Two important votive crowns are those of

Recceswinth and of

Suintila

Suintila, or ''Suinthila'', ''Swinthila'', ''Svinthila''; (ca. 588 – 633/635) was Visigothic King of Hispania, Septimania and Galicia from 621 to 631. He was a son of Reccared I and his wife Bado, and a brother of the general Geila. Under S ...

, displayed in the National Archaeological Museum of Madrid; both are made of gold, encrusted with sapphires, pearls, and other precious stones. Suintila's crown was stolen in 1921 and never recovered. There are several other small crowns and many votive crosses in the treasure.

* The aquiliform (eagle-shaped)

fibulae

The fibula or calf bone is a leg bone on the lateral side of the tibia, to which it is connected above and below. It is the smaller of the two bones and, in proportion to its length, the most slender of all the long bones. Its upper extremity i ...

that have been discovered in

necropolis

A necropolis (plural necropolises, necropoles, necropoleis, necropoli) is a large, designed cemetery with elaborate tomb monuments. The name stems from the Ancient Greek ''nekropolis'', literally meaning "city of the dead".

The term usually im ...

es such as

Duraton,

Madrona or Castiltierra (cities of

Segovia. These fibulae were used individually or in pairs, as clasps or pins in gold, bronze and glass to join clothes.

* The Visigothic belt buckles, a symbol of rank and status characteristic of Visigothic women's clothing, are also notable as works of goldsmithery. Some pieces contain exceptional

Byzantine-style lapis lazuli

Lapis lazuli (; ), or lapis for short, is a deep-blue metamorphic rock used as a semi-precious stone that has been prized since antiquity for its intense color.

As early as the 7th millennium BC, lapis lazuli was mined in the Sar-i Sang mine ...

inlays and are generally rectangular in shape, with copper alloy, garnets and glass.

The architecture of Visigothic Hispania

* During their governance of Hispania, the Visigoths built several churches in the

basilica

In Ancient Roman architecture, a basilica is a large public building with multiple functions, typically built alongside the town's forum. The basilica was in the Latin West equivalent to a stoa in the Greek East. The building gave its nam ...

l or

cruciform

Cruciform is a term for physical manifestations resembling a common cross or Christian cross. The label can be extended to architectural shapes, biology, art, and design.

Cruciform architectural plan

Christian churches are commonly describe ...

style that survive, including the churches of

San Pedro de la Nave in El Campillo,

Santa María de Melque in

San Martín de Montalbán, Santa Lucía del Trampal in Alcuéscar, Santa Comba in Bande, and

Santa María de Lara in Quintanilla de las Viñas. The Visigothic

crypt

A crypt (from Latin '' crypta'' " vault") is a stone chamber beneath the floor of a church or other building. It typically contains coffins, sarcophagi, or religious relics.

Originally, crypts were typically found below the main apse of a c ...

(the Crypt of San Antolín) in the

Palencia Cathedral is a Visigothic chapel from the mid 7th century, built during the reign of

Wamba to preserve the remains of the martyr

Saint Antoninus of Pamiers

Saint Antoninus of Pamiers (french: Saint Antonin, oc, Sant Antoní, and es, San Antolín) was an early Christian missionary and martyr, called the "Apostle of the Rouergue". His life is dated to the first, second, fourth, and fifth century by ...

, a Visigothic-Gallic nobleman brought from Narbonne to Visigothic Hispania in 672 or 673 by Wamba himself. These are the only remains of the Visigothic cathedral of Palencia.

*

Reccopolis, located near the tiny modern village of

Zorita de los Canes

Zorita de los Canes is a municipality located in the province of Guadalajara, Castile-La Mancha, Spain. According to the 2004 census (INE), the municipality has a population of 98 inhabitants. There is a castle

A castle is a type of fort ...

in the

province of Guadalajara, Castile-La Mancha, Spain, is an archaeological site of one of at least four cities founded in

Hispania

Hispania ( la, Hispānia , ; nearly identically pronounced in Spanish, Portuguese, Catalan, and Italian) was the Roman name for the Iberian Peninsula and its provinces. Under the Roman Republic, Hispania was divided into two provinces: Hi ...

by the Visigoths. It is the only city in Western Europe to have been founded between the fifth and eighth centuries. The city's construction was ordered by the Visigothic king

Liuvigild

Liuvigild, Leuvigild, Leovigild, or ''Leovigildo'' ( Spanish and Portuguese), ( 519 – 586) was a Visigothic King of Hispania and Septimania from 568 to 586. Known for his Codex Revisus or Code of Leovigild, a law allowing equal rights between ...

to honor his son

Reccared and to serve as Reccared's seat as co-king in the Visigothic province of

Celtiberia, to the west of

Carpetania, where the main capital, Toledo, lay.

Religion

At the beginning of the

Visigothic Kingdom

The Visigothic Kingdom, officially the Kingdom of the Goths ( la, Regnum Gothorum), was a kingdom that occupied what is now southwestern France and the Iberian Peninsula from the 5th to the 8th centuries. One of the Germanic successor states to ...

,

Arianism

Arianism ( grc-x-koine, Ἀρειανισμός, ) is a Christological doctrine first attributed to Arius (), a Christian presbyter from Alexandria, Egypt. Arian theology holds that Jesus Christ is the Son of God, who was begotten by God ...

was the official religion in Hispania, but only for a brief time, according to historian Rhea Marsh Smith (1905–1991). In 587,

Reccared, the Visigothic king at Toledo, converted to Catholicism and launched a movement to unify the various religious doctrines that existed in the Iberian Peninsula. The

Councils of Toledo

From the 5th century to the 7th century AD, about thirty synods, variously counted, were held at Toledo (''Concilia toletana'') in what would come to be part of Spain. The earliest, directed against Priscillianism, assembled in 400. The "thir ...

debated the creed and liturgy of orthodox

Catholicism

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

, and the Council of Lerida in 546 constrained the clergy and extended the power of law over them with the approval of the pope.

While the Visigoths clung to their Arian faith, the

Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

were well-tolerated. Previous Roman and Byzantine law determined their status, and already sharply discriminated against them. Historian Jane Gerber relates that some of the Jews "held ranking posts in the government or the army; others were recruited and organized for garrison service; still others continued to hold senatorial rank". In general, then, they were well-respected and well-treated by the Visigothic kings, that is, until their transition from Arianism to Catholicism. Conversion to Catholicism across Visigothic society reduced the friction between the Visigoths and the Hispano-Roman population. However, the Visigothic conversion negatively impacted the Jews, who came under scrutiny for their religious practices.

Islamic ''al-Andalus'' and the Christian ''Reconquest'' (8th–15th centuries)

The

Arab Islamic conquest dominated most of North Africa by 710 AD. In 711 an Islamic

Berber

Berber or Berbers may refer to:

Ethnic group

* Berbers, an ethnic group native to Northern Africa

* Berber languages, a family of Afro-Asiatic languages

Places

* Berber, Sudan, a town on the Nile

People with the surname

* Ady Berber (1913–19 ...

conquering party, led by

Tariq ibn Ziyad, was sent to Hispania to intervene in a civil war in the

Visigothic Kingdom

The Visigothic Kingdom, officially the Kingdom of the Goths ( la, Regnum Gothorum), was a kingdom that occupied what is now southwestern France and the Iberian Peninsula from the 5th to the 8th centuries. One of the Germanic successor states to ...

. Tariq's army contained about 7,000 Berber horsemen, and

Musa bin Nusayr is said to have sent an additional 5,000 reinforcements after the conquest. Crossing the

Strait of Gibraltar

The Strait of Gibraltar ( ar, مضيق جبل طارق, Maḍīq Jabal Ṭāriq; es, Estrecho de Gibraltar, Archaic: Pillars of Hercules), also known as the Straits of Gibraltar, is a narrow strait that connects the Atlantic Ocean to the Medi ...

, they won a decisive victory in the summer of 711 when the Visigothic King

Roderic

Roderic (also spelled Ruderic, Roderik, Roderich, or Roderick; Spanish and pt, Rodrigo, ar, translit=Ludharīq, لذريق; died 711) was the Visigothic king in Hispania between 710 and 711. He is well-known as "the last king of the Goths". H ...

was defeated and killed on July 19 at the

Battle of Guadalete

The Battle of Guadalete was the first major battle of the Umayyad conquest of Hispania, fought in 711 at an unidentified location in what is now southern Spain between the Christian Visigoths under their king, Roderic, and the invading forces of ...

. Tariq's commander, Musa, quickly crossed with Arab reinforcements, and by 718 the

Muslim

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

s were in control of nearly the whole

Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula (),

**

* Aragonese and Occitan: ''Peninsula Iberica''

**

**

* french: Péninsule Ibérique

* mwl, Península Eibérica

* eu, Iberiar penintsula also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in southwestern Europe, def ...

. The advance into

Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's countries and territories vary depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the ancient Mediterranean ...

was only stopped in what is now north-central France by the

West Germanic Franks

The Franks ( la, Franci or ) were a group of Germanic peoples whose name was first mentioned in 3rd-century Roman sources, and associated with tribes between the Lower Rhine and the Ems River, on the edge of the Roman Empire.H. Schutz: Tools ...

under

Charles Martel

Charles Martel ( – 22 October 741) was a Frankish political and military leader who, as Duke and Prince of the Franks and Mayor of the Palace, was the de facto ruler of Francia from 718 until his death. He was a son of the Frankish statesm ...

at the

Battle of Tours in 732.

The Muslim conquerors (also known as "Moors") were

Arabs

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Western Asia, ...

and

Berbers

, image = File:Berber_flag.svg

, caption = The Berber ethnic flag

, population = 36 million

, region1 = Morocco

, pop1 = 14 million to 18 million

, region2 = Algeria

, pop2 ...

; following the conquest, conversion and arabization of the Hispano-Roman population took place, (''muwalladum'' or ''

Muwallad'').

After a long process, spurred on in the 9th and 10th centuries, the majority of the population in Al-Andalus eventually converted to Islam. The Muslim population was divided per ethnicity (Arabs, Berbers, Muwallad), and the supremacy of Arabs over the rest of group was a recurrent causal for strife, rivalry and hatred, particularly between Arabs and Berbers. Arab elites could be further divided in the Yemenites (first wave) and the Syrians (second wave). Male Muslim rulers were often the offspring of female Christian slaves.

Christians and Jews were allowed to live as subordinate groups of a stratified society under the

''dhimmah'' system, although Jews became very important in certain fields. Some Christians migrated to the Northern Christian kingdoms, while those who stayed in Al-Andalus progressively arabised and became known as ''musta'arab'' (

mozarab

The Mozarabs ( es, mozárabes ; pt, moçárabes ; ca, mossàrabs ; from ar, مستعرب, musta‘rab, lit=Arabized) is a modern historical term for the Iberian Christians, including Christianized Iberian Jews, who lived under Muslim rule in A ...

s). Besides slaves of Iberian origin,

the slave population also comprised the ''

Ṣaqāliba'' (literally meaning "slavs", although they were slaves of generic European origin) as well as

Sudanese slaves. The frequent raids in Christian lands provided Al-Andalus with continuous slave stock, including women who often became part of the harems of the Muslim elite.

Slaves were also shipped from Spain to elsewhere in the

Ummah

' (; ar, أمة ) is an Arabic word meaning "community". It is distinguished from ' ( ), which means a nation with common ancestry or geography. Thus, it can be said to be a supra-national community with a common history.

It is a synonym for ' ...

.

In what should not have amounted to much more than a skirmish (later magnified by

Spanish nationalism), a Muslim force sent to put down the Christian rebels in the northern mountains was defeated by a force reportedly led by the legendary

Pelagius

Pelagius (; c. 354–418) was a British theologian known for promoting a system of doctrines (termed Pelagianism by his opponents) which emphasized human choice in salvation and denied original sin. Pelagius and his followers abhorred the moral ...

, this is known as the

Battle of Covadonga

The Battle of Covadonga took place in 718 or 722 between the army of Pelagius the Visigoth and the army of the Umayyad Caliphate. Fought near Covadonga in the Picos de Europa, either in 718 or 722, it resulted in a victory for the forces of Pel ...

. The figure of Pelagius, a by-product of the Asturian chronicles of

Alfonso III (written more than a century after the alleged battle), has been later reconstructed in conflicting historiographical theories, most notably that of a refuged Visigoth noble or an autochthonous

Astur

The Astures or Asturs, also named Astyrs, were the Hispano-Celtic inhabitants of the northwest area of Hispania that now comprises almost the entire modern autonomous community of Principality of Asturias, the modern province of León, and the ...

chieftain. The consolidation of a Christian polity that came to be known as the

Kingdom of Asturias

The Kingdom of Asturias ( la, Asturum Regnum; ast, Reinu d'Asturies) was a kingdom in the Iberian Peninsula founded by the Visigothic nobleman Pelagius. It was the first Christian political entity established after the Umayyad conquest of ...

ensued later. At the end of Visigothic rule, the assimilation of Hispano-Romans and Visigoths was occurring at a fast pace. An unknown number of them fled and took refuge in Asturias or Septimania. In Asturias they supported Pelagius's uprising, and joining with the indigenous leaders, formed a new aristocracy. The population of the mountain region consisted of native

Astures,

Galicians,

Cantabri,

Basques

The Basques ( or ; eu, euskaldunak ; es, vascos ; french: basques ) are a Southwestern European ethnic group, characterised by the Basque language, a common culture and shared genetic ancestry to the ancient Vascones and Aquitanians. Ba ...

and other groups unassimilated into Hispano-Gothic society.

In 739, a rebellion in Galicia, assisted by the Asturians, drove out Muslim forces and it joined the Asturian kingdom. In the northern Christian kingdoms, lords and religious organizations often owned Muslim slaves who were employed as day laborers and household servants.

Caliph

A caliphate or khilāfah ( ar, خِلَافَة, ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with the title of caliph (; ar, خَلِيفَة , ), a person considered a political-religious successor to th ...

Al-Walid I

Al-Walid ibn Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan ( ar, الوليد بن عبد الملك بن مروان, al-Walīd ibn ʿAbd al-Malik ibn Marwān; ), commonly known as al-Walid I ( ar, الوليد الأول), was the sixth Umayyad caliph, ruling from O ...

had paid great attention to the expansion of an organized military, building the strongest navy in the

Umayyad Caliphate

The Umayyad Caliphate (661–750 CE; , ; ar, ٱلْخِلَافَة ٱلْأُمَوِيَّة, al-Khilāfah al-ʾUmawīyah) was the second of the four major caliphates established after the death of Muhammad. The caliphate was ruled by th ...

era (the second major Arab dynasty after Mohammad and the first Arab dynasty of

Al-Andalus

Al-Andalus translit. ; an, al-Andalus; ast, al-Ándalus; eu, al-Andalus; ber, ⴰⵏⴷⴰⵍⵓⵙ, label= Berber, translit=Andalus; ca, al-Àndalus; gl, al-Andalus; oc, Al Andalús; pt, al-Ândalus; es, al-Ándalus () was the M ...

). It was this tactic that supported the ultimate expansion to Hispania. Islamic power in Spain specifically climaxed in the 10th century under

Abd-ar-Rahman III

ʿAbd al-Rahmān ibn Muḥammad ibn ʿAbd Allāh ibn Muḥammad ibn ʿAbd al-Raḥmān ibn al-Ḥakam al-Rabdī ibn Hishām ibn ʿAbd al-Raḥmān al-Dākhil () or ʿAbd al-Rahmān III (890 - 961), was the Umayyad Emir of Córdoba from 912 to 9 ...

. The rulers of

Al-Andalus

Al-Andalus translit. ; an, al-Andalus; ast, al-Ándalus; eu, al-Andalus; ber, ⴰⵏⴷⴰⵍⵓⵙ, label= Berber, translit=Andalus; ca, al-Àndalus; gl, al-Andalus; oc, Al Andalús; pt, al-Ândalus; es, al-Ándalus () was the M ...

were granted the rank of

Emir

Emir (; ar, أمير ' ), sometimes transliterated amir, amier, or ameer, is a word of Arabic origin that can refer to a male monarch, aristocrat, holder of high-ranking military or political office, or other person possessing actual or cer ...

by the Umayyad Caliph Al-Walid I in

Damascus

)), is an adjective which means "spacious".

, motto =

, image_flag = Flag of Damascus.svg

, image_seal = Emblem of Damascus.svg

, seal_type = Seal

, map_caption =

, ...

. When the

Abbasids

The Abbasid Caliphate ( or ; ar, الْخِلَافَةُ الْعَبَّاسِيَّة, ') was the third caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abdul-Muttalib ...

overthrew the Umayyad Caliphate,

Abd al-Rahman I managed to escape to al-Andalus. Once arrived, he declared al-Andalus independent. It is not clear if Abd al-Rahman considered himself to be a rival caliph, perpetuating the Umayyad Caliphate, or merely an independent Emir. The state founded by him is known as the

Emirate of Cordoba. Al-Andalus was rife with internal conflict between the Islamic Umayyad rulers and people and the Christian Visigoth-Roman leaders and people.

The Vikings invaded Galicia in 844, but were heavily defeated by

Ramiro I at

A Coruña

A Coruña (; es, La Coruña ; historical English: Corunna or The Groyne) is a city and municipality of Galicia, Spain. A Coruña is the most populated city in Galicia and the second most populated municipality in the autonomous community and ...

.

[ Many of the Vikings' casualties were caused by the Galicians' ballistas – powerful torsion-powered projectile weapons that looked rather like giant crossbows.][ 70 Viking ships were captured and burned.]Abd-ar-Rahman III