Prior to the 17th century China and Russia were on opposite ends of

Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a part ...

, which was populated by independent nomads. By about 1640

Russian settlers had traversed most of Siberia and founded settlements in the

Amur River

The Amur (russian: река́ Аму́р, ), or Heilong Jiang (, "Black Dragon River", ), is the world's tenth longest river, forming the border between the Russian Far East and Northeastern China (Inner Manchuria). The Amur proper is long ...

basin. From 1652 to 1689, China's armies

drove the Russian settlers out, but after 1689, China and Russia made peace and established trade agreements.

By the mid-19th century, China's economy and military lagged far behind the colonial powers. It signed

unequal treaties

Unequal treaty is the name given by the Chinese to a series of treaties signed during the 19th and early 20th centuries, between China (mostly referring to the Qing dynasty) and various Western powers (specifically the British Empire, France, the ...

with Western countries and Russia, through which Russia annexed the Amur basin and

Vladivostok

Vladivostok ( rus, Владивосто́к, a=Владивосток.ogg, p=vɫədʲɪvɐˈstok) is the largest city and the administrative center of Primorsky Krai, Russia. The city is located around the Golden Horn Bay on the Sea of Japan, ...

. The

Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War ...

and Western powers exacted many other concessions from China, such as indemnities for anti-Western riots, control over China's tariffs, and

extraterritorial

In international law, extraterritoriality is the state of being exempted from the jurisdiction of local law, usually as the result of diplomatic negotiations.

Historically, this primarily applied to individuals, as jurisdiction was usually cl ...

agreements including legal immunity for foreigners and foreign businesses.

Meanwhile, Russian culture and society, especially the elite, were westernized. The ruler of Russia officially was no longer called tsar but emperor, an import from Western Europe.

Issues that affected only Russia and China were mainly the Russian-Chinese border since Russia, unlike the

Western countries

The Western world, also known as the West, primarily refers to the various nations and states in the regions of Europe, North America, and Oceania. , bordered China. Many Chinese people felt humiliated by China's submission to foreign interests, which contributed to widespread hostility towards the emperor of China.

In 1911, the

Xinhai Revolution

The 1911 Revolution, also known as the Xinhai Revolution or Hsinhai Revolution, ended China's last imperial dynasty, the Manchu-led Qing dynasty, and led to the establishment of the Republic of China. The revolution was the culmination of ...

broke out and led to the establishment of the

Republic of China

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the northeas ...

. However, China's new regime, known as the

Beiyang government

The Beiyang government (), officially the Republic of China (), sometimes spelled Peiyang Government, refers to the government of the Republic of China which sat in its capital Peking (Beijing) between 1912 and 1928. It was internationally ...

, was forced to sign more unequal treaties with Western countries and with Russia. In recent years, Russia and China signed a border agreement.

In late 1917,

Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 million ...

and

Petrograd

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

were taken over by a

communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, ...

group, the

Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

, during the

October Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key mom ...

, which caused the

Russian Civil War

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Russian Civil War

, partof = the Russian Revolution and the aftermath of World War I

, image =

, caption = Clockwise from top left:

{{flatlist,

*Soldiers ...

between the Bolshevik

Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian language, Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist R ...

and the anticommunist

White

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no hue). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully reflect and scatter all the visible wavelengths of light. White ...

forces. China's Beiyang government sided with the Whites and, along with most of the West,

sent troops to fight against the Reds. In 1922, the Reds won the civil war and established a new country: the

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

. In 1923, the Soviets provided aid and support to the

Kuomintang

The Kuomintang (KMT), also referred to as the Guomindang (GMD), the Nationalist Party of China (NPC) or the Chinese Nationalist Party (CNP), is a major political party in the Republic of China, initially on the Chinese mainland and in Ta ...

, a Chinese faction that had been opposed to the Beiyang government. In alliance with the small

Chinese Communist Party (CCP), the Kuomintang

seized power in 1928, and both countries established diplomatic ties.

Sino–Soviet relations remained fractious, and both countries

fought two wars for the

next ten years. Nevertheless, the Soviets, under

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet Union, Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as Ge ...

, helped

Chiang Kai-shek

Chiang Kai-shek (31 October 1887 – 5 April 1975), also known as Chiang Chung-cheng and Jiang Jieshi, was a Chinese Nationalist politician, revolutionary, and military leader who served as the leader of the Republic of China (ROC) from 1928 ...

's Kuomintang government against

Imperial Japan

The also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was a historical nation-state and great power that existed from the Meiji Restoration in 1868 until the enactment of the post-World War II 1947 constitution and subsequent forma ...

. Stalin told the Communists' leader,

Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong pronounced ; also Romanization of Chinese, romanised traditionally as Mao Tse-tung. (26 December 1893 – 9 September 1976), also known as Chairman Mao, was a Chinese communist revolutionary who was the List of national founde ...

, to co-operate with China's Kuomintang regime, but once in power, the Kuomintang orchestrated a violent mass purge of Communists, referred to as the

Shanghai Massacre

The Shanghai massacre of 12 April 1927, the April 12 Purge or the April 12 Incident as it is commonly known in China, was the violent suppression of Chinese Communist Party (CCP) organizations and leftist elements in Shanghai by forces supportin ...

.

In 1937, the Kuomintang and the communists formed a new alliance to oppose the

Japanese invasion of China

The Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945) or War of Resistance (Chinese term) was a military conflict that was primarily waged between the Republic of China and the Empire of Japan. The war made up the Chinese theater of the wider Pacific The ...

, but they resumed fighting each other in 1942. After Japan had been defeated in 1945, both Chinese factions signed a

truce

A ceasefire (also known as a truce or armistice), also spelled cease fire (the antonym of 'open fire'), is a temporary stoppage of a war in which each side agrees with the other to suspend aggressive actions. Ceasefires may be between state ac ...

, but the

Chinese Civil War

The Chinese Civil War was fought between the Kuomintang-led government of the Republic of China and forces of the Chinese Communist Party, continuing intermittently since 1 August 1927 until 7 December 1949 with a Communist victory on main ...

soon erupted again between them.

In 1949, with Soviet support, the communists won the

Chinese Civil War

The Chinese Civil War was fought between the Kuomintang-led government of the Republic of China and forces of the Chinese Communist Party, continuing intermittently since 1 August 1927 until 7 December 1949 with a Communist victory on main ...

and established the

People's Republic of China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, most populous country, with a Population of China, population exceeding 1.4 billion, slig ...

, which made an

alliance

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

with the Soviets. Mao became the first leader of Communist China. Mao's most radical supporters, who became known as the "

Gang of Four

The Gang of Four () was a Maoist political faction composed of four Chinese Communist Party (CCP) officials. They came to prominence during the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976) and were later charged with a series of treasonous crimes. The gang ...

," gradually eliminated most of his rivals throughout his 27 years in power.

Ideological tension between the two countries emerged after Stalin's death in 1953.

Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and chairman of the country's Council of Ministers from 1958 to 1964. During his rule, Khrushchev s ...

denounced Stalin's crimes in 1956, and both regimes started to criticise each other. At first, the criticism was indirect and muted, but in 1961, Mao accused the Soviet leadership of

revisionism, and the alliance openly ended. Both countries competed for control over foreign communist states and political movements, and many countries had two rival communist parties that concentrated their fire on each other.

In 1969, a

brief border war between the two countries occurred. Khrushchev had been replaced by

Leonid Brezhnev

Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev; uk, links= no, Леонід Ілліч Брежнєв, . (19 December 1906– 10 November 1982) was a Soviet politician who served as General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union between 1964 and 1 ...

in 1964, who abandoned many Soviet reforms criticized by Mao. However, China's anti-Soviet rhetoric intensified under the influence of Mao's closest supporters, the Gang of Four. Mao died in 1976, and the Gang of Four lost power in 1978.

After a period of instability,

Deng Xiaoping

Deng Xiaoping (22 August 1904 – 19 February 1997) was a Chinese revolutionary leader, military commander and statesman who served as the paramount leader of the China, People's Republic of China (PRC) from December 1978 to November 1989. Aft ...

became the new leader of China. The philosophical difference between both countries lessened somewhat since China's new leadership abandoned

anti-revisionism

Anti-revisionism is a position within Marxism–Leninism which emerged in the 1950s in opposition to the reforms of Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev. Where Khrushchev pursued an interpretation that differed from his predecessor Joseph Stalin, ...

.

China's internal reforms did not bring an immediate end to conflict with the Soviet Union. In 1979,

China invaded Vietnam, which was a Soviet ally. China also sent aid to the mujahedin against the

Soviet invasion of Afghanistan

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nation ...

. In 1982, Brezhnev made a speech offering reconciliation with China, and Deng agreed to restore diplomatic relations.

In 1985,

Mikhail Gorbachev

Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev (2 March 1931 – 30 August 2022) was a Soviet politician who served as the 8th and final leader of the Soviet Union from 1985 to the country's dissolution in 1991. He served as General Secretary of the Com ...

became

General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

A general officer is an officer of high rank in the armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colonel."general, adj. and n.". OED ...

, reduced the Soviet garrisons at the Sino–Soviet border and in Mongolia, resumed trade, and dropped the border issue that had caused open war 16 years earlier. In 1989, he withdrew Soviet support from the communist government of Afghanistan. Rapprochement accelerated after the Soviet Union fell and was replaced by the

Russian Federation

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-eig ...

in 1991.

Sino–Russian relations since 1991 are currently close and cordial. Both countries maintain a strong

geopolitical

Geopolitics (from Greek γῆ ''gê'' "earth, land" and πολιτική ''politikḗ'' "politics") is the study of the effects of Earth's geography (human and physical) on politics and international relations. While geopolitics usually refers to ...

and

regional

In geography, regions, otherwise referred to as zones, lands or territories, are areas that are broadly divided by physical characteristics (physical geography), human impact characteristics (human geography), and the interaction of humanity and t ...

alliance and significant levels of

trade

Trade involves the transfer of goods and services from one person or entity to another, often in exchange for money. Economists refer to a system or network that allows trade as a market.

An early form of trade, barter, saw the direct exc ...

.

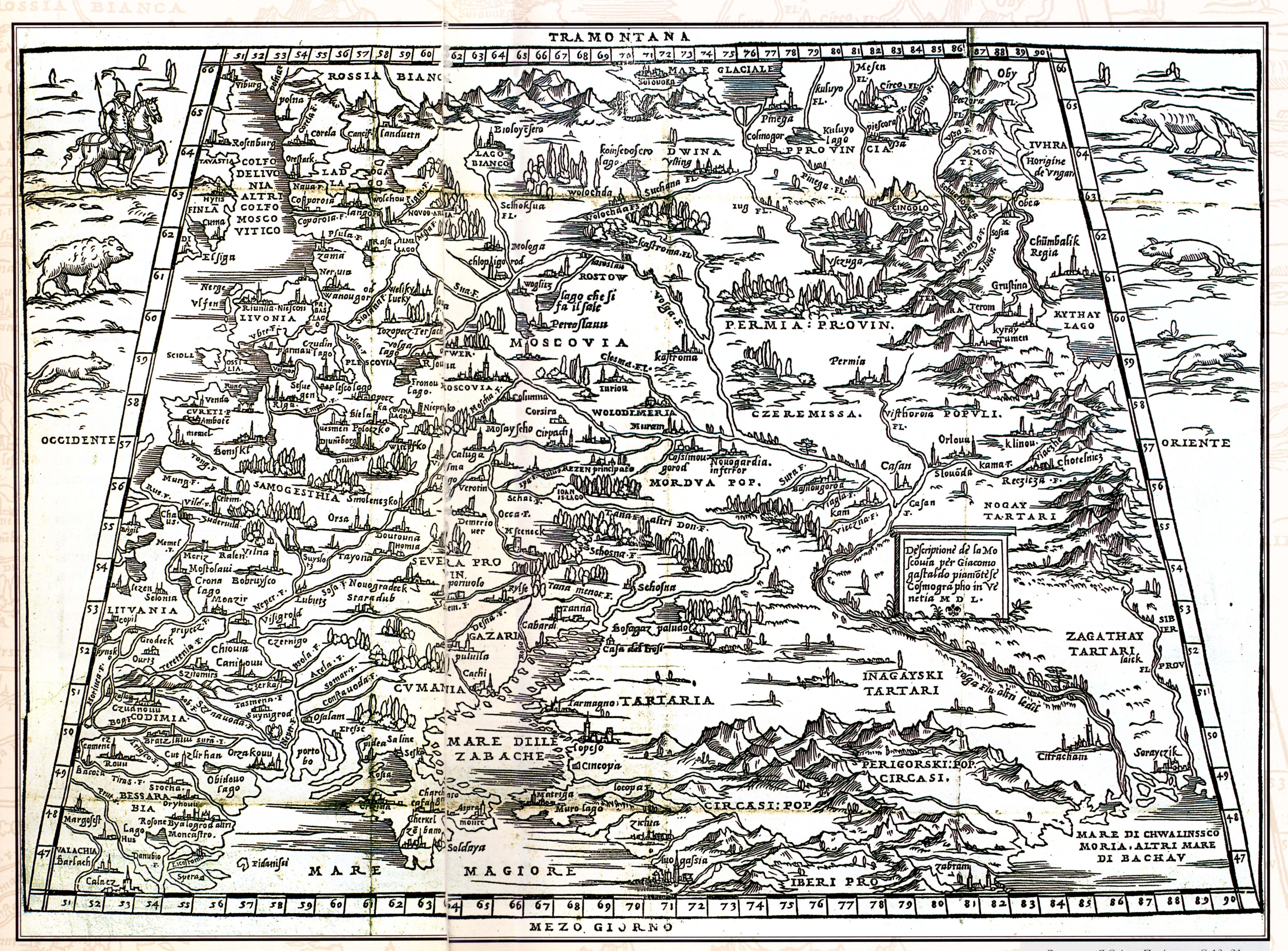

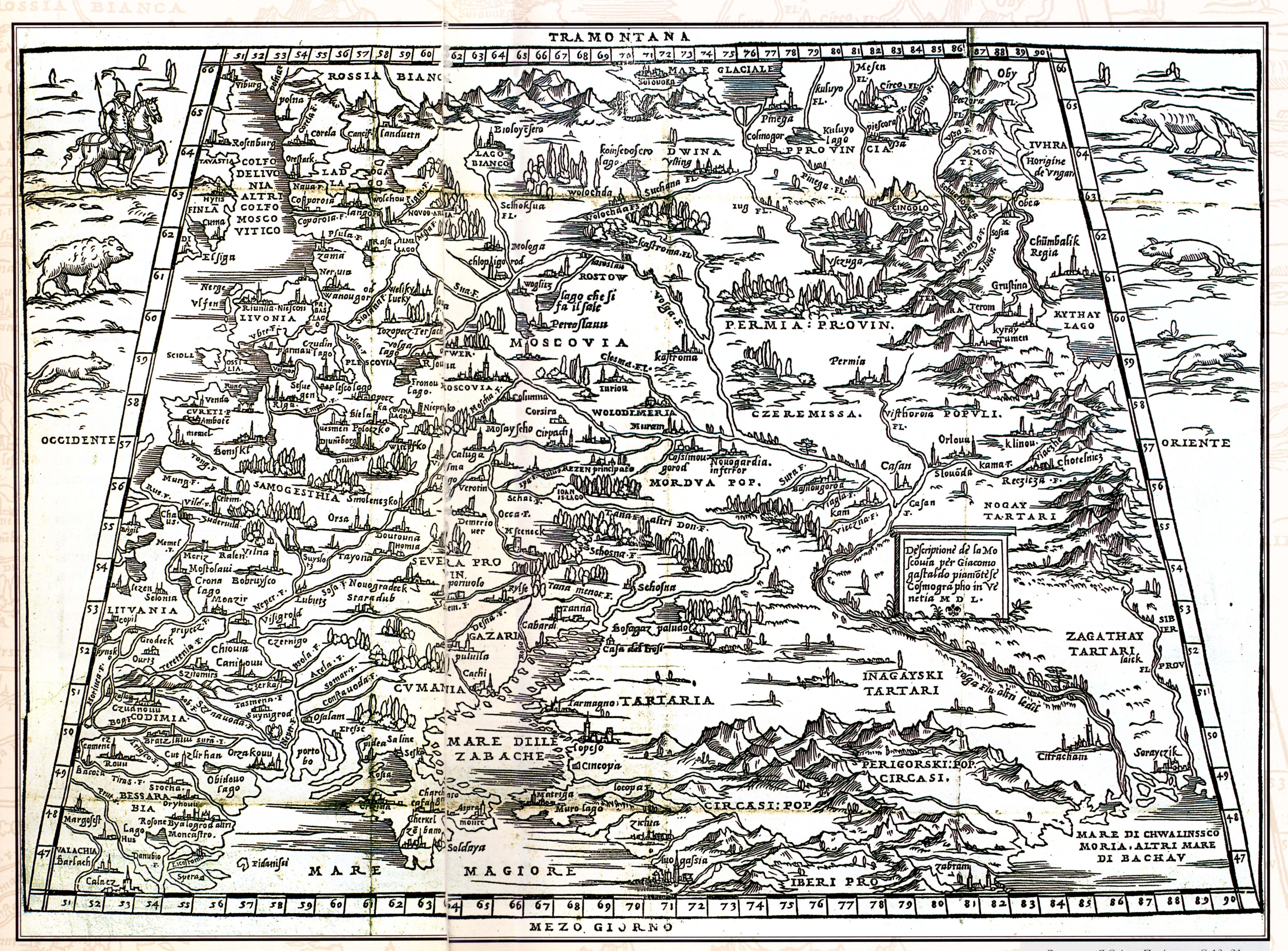

Imperial period

Lying at opposite ends of Eurasia, the two countries had little contact before about 1640. Both had to deal with the steppe nomads, Russia from the south and China from the northwest. Russia became a northern neighbor of China when in 1582–1643 Russian adventurers

made themselves masters of the Siberian forests. There were three points of contact: 1) south to the Amur River basin (early), 2) east along the southern edge of Siberia toward Peking (the main axis) and 3) in Turkestan (late).

The

Oirats

Oirats ( mn, Ойрад, ''Oirad'', or , Oird; xal-RU, Өөрд; zh, 瓦剌; in the past, also Eleuths) are the westernmost group of the Mongols whose ancestral home is in the Altai region of Siberia, Xinjiang and western Mongolia.

Histor ...

transmitted some garbled and incorrect descriptions of China to the Russians in 1614, the name "Taibykankan" was used to refer to the

Wanli Emperor

The Wanli Emperor (; 4 September 1563 – 18 August 1620), personal name Zhu Yijun (), was the 14th Emperor of the Ming dynasty, reigned from 1572 to 1620. "Wanli", the era name of his reign, literally means "ten thousand calendars". He was th ...

by the Oirats.

South to the Amur (1640–1689)

About 1640 Siberian cossacks spilled over the

Stanovoy Mountains

The Stanovoy Range (russian: Станово́й хребе́т, ''Stanovoy khrebet''; sah, Сир кура; ), is a mountain range located in the Sakha Republic and Amur Oblast, Far Eastern Federal District. It is also known as Sükebayatur a ...

to the

Amur River

The Amur (russian: река́ Аму́р, ), or Heilong Jiang (, "Black Dragon River", ), is the world's tenth longest river, forming the border between the Russian Far East and Northeastern China (Inner Manchuria). The Amur proper is long ...

basin. This land was claimed by the

Manchus

The Manchus (; ) are a Tungusic East Asian ethnic group native to Manchuria in Northeast Asia. They are an officially recognized ethnic minority in China and the people from whom Manchuria derives its name. The Later Jin (1616–1636) and ...

who at this time were just beginning their conquest of China (

Qing dynasty

The Qing dynasty ( ), officially the Great Qing,, was a Manchu-led imperial dynasty of China and the last orthodox dynasty in Chinese history. It emerged from the Later Jin dynasty founded by the Jianzhou Jurchens, a Tungusic-speak ...

). By 1689 the Russians were driven back over the mountains and the Stanovoy Mountains remained the Russo-Chinese frontier from the

Treaty of Nerchinsk

The Treaty of Nerchinsk () of 1689 was the first treaty between the Tsardom of Russia and the Qing dynasty of China. The Russians gave up the area north of the Amur River as far as the Stanovoy Range and kept the area between the Argun River ...

(1689) to the

Treaty of Aigun

The Treaty of Aigun (Russian: Айгунский договор; ) was an 1858 treaty between the Russian Empire and the Qing dynasty that established much of the modern border between the Russian Far East and China by ceding much of Manchur ...

in 1859. For a full account see

Sino–Russian border conflicts.

Russian expansion eastward along the southern edge of Siberia

Russian expansion in Siberia was confined to the forested area because the Cossacks were skilled in forest travel and were seeking furs while the forest natives were weak and the steppe nomads warlike. In the west, Siberia borders on the

Kazakh Steppe. North of what is now Mongolia, there are mountains,

Lake Baikal

Lake Baikal (, russian: Oзеро Байкал, Ozero Baykal ); mn, Байгал нуур, Baigal nuur) is a rift lake in Russia. It is situated in southern Siberia, between the federal subjects of Irkutsk Oblast to the northwest and the ...

and more mountains until the

Argun River separates

Trans-Baikal

Transbaikal, Trans-Baikal, Transbaikalia ( rus, Забайка́лье, r=Zabaykalye, p=zəbɐjˈkalʲjɪ), or Dauria (, ''Dauriya'') is a mountainous region to the east of or "beyond" (trans-) Lake Baikal in Far Eastern Russia.

The steppe and ...

ia from

Manchuria

Manchuria is an exonym (derived from the endo demonym " Manchu") for a historical and geographic region in Northeast Asia encompassing the entirety of present-day Northeast China (Inner Manchuria) and parts of the Russian Far East (Outer M ...

. West of Siberia, Russia slowly expanded down the Volga, around the southern Urals and out into the Kazakh steppe.

Early contacts

From the time of

Kievan Rus'

Kievan Rusʹ, also known as Kyivan Rusʹ ( orv, , Rusĭ, or , , ; Old Norse: ''Garðaríki''), was a state in Eastern and Northern Europe from the late 9th to the mid-13th century.John Channon & Robert Hudson, ''Penguin Historical Atlas o ...

there was trade (fur, slaves) down the Volga to the Caspian Sea and Persia. Later trade extended southeast to the main Asian trade routes at

Bukhara

Bukhara ( Uzbek: /, ; tg, Бухоро, ) is the seventh-largest city in Uzbekistan, with a population of 280,187 , and the capital of Bukhara Region.

People have inhabited the region around Bukhara for at least five millennia, and the city ...

. Under the Mongol Yoke, Russian princes would regularly travel to

Sarai for investiture. When Marco Polo returned from China he mentioned Russia as an obscure country in the far north. In 1466/73

Afanasy Nikitin Afanasy Nikitin (russian: Афана́сий Ники́тин; died 1472) was a Russian merchant from Tver and one of the first Europeans (after Niccolò de' Conti) to travel to and document his visit to India. He described his trip in a narrat ...

made a journey southeast to India and left an interesting account. After the English

reached

''Reached'' is a 2012 young adult dystopian novel by Allyson Braithwaite Condie and is the final novel in the ''Matched Trilogy,'' preceded by '' Matched'' and '' Crossed''. The novel was published on November 13, 2012, by Dutton Juvenile and wa ...

the White Sea,

Anthony Jenkinson

Anthony Jenkinson (1529 – 1610/1611) was born at Market Harborough, Leicestershire. He was one of the first Englishmen to explore Muscovy and present-day Russia. Jenkinson was a traveller and explorer on behalf of the Muscovy Company ...

travelled through Muscovy to

Bukhara

Bukhara ( Uzbek: /, ; tg, Бухоро, ) is the seventh-largest city in Uzbekistan, with a population of 280,187 , and the capital of Bukhara Region.

People have inhabited the region around Bukhara for at least five millennia, and the city ...

. In 1608 the Voivode of

Tomsk

Tomsk ( rus, Томск, p=tomsk, sty, Түң-тора) is a city and the administrative center of Tomsk Oblast in Russia, located on the Tom River. Population:

Founded in 1604, Tomsk is one of the oldest cities in Siberia. The city is a n ...

tried and failed to reach China via the

Altan Khan

Altan Khan of the Tümed (1507–1582; mn, ᠠᠯᠲᠠᠨ ᠬᠠᠨ, Алтан хан; Chinese: 阿勒坦汗), whose given name was Anda ( Mongolian: ; Chinese: 俺答), was the leader of the Tümed Mongols and de facto ruler of the Right Win ...

in western Mongolia. In 1616 a second attempt got as far as the Khan (Vasilly Tyumenets and Ivan Petrov). The first Russian to reach Peking was probably

Ivan Petlin

Ivan Petlin (russian: Иван Петлин; 17th-century diminutive form, russian: Ивашко Петлин, Ivashko (Evashko) Petlin), a Siberian Cossack, was the first Russian to have reached China on an official mission (1618-1619). His expe ...

in 1618/19.

After the Russians reached

Trans-Baikal

Transbaikal, Trans-Baikal, Transbaikalia ( rus, Забайка́лье, r=Zabaykalye, p=zəbɐjˈkalʲjɪ), or Dauria (, ''Dauriya'') is a mountainous region to the east of or "beyond" (trans-) Lake Baikal in Far Eastern Russia.

The steppe and ...

ia in the 1640s, some trade developed, but it is poorly documented. At this point there were three routes: 1)

Irtysh River

The Irtysh ( otk, 𐰼𐱅𐰾:𐰇𐰏𐰕𐰏, Ertis ügüzüg, mn, Эрчис мөрөн, ''Erchis mörön'', "erchleh", "twirl"; russian: Иртыш; kk, Ертіс, Ertis, ; Chinese: 额尔齐斯河, pinyin: ''É'ěrqísī hé'', Xiao'e ...

and east across Dzungaria and Mongolia, 2) Lake Baikal,

Selenga River

The Selenga or Selenge ( ; bua, Сэлэнгэ гол / Сэлэнгэ мүрэн, translit=Selenge gol / Selenge müren; russian: Селенга́, ) is a major river in Mongolia and Buryatia, Russia. Originating from its headwater tributaries ...

and southeast (the shortest) and 3) Lake Baikal, east to

Nerchinsk

Nerchinsk ( rus, Не́рчинск; bua, Нэршүү, ''Nershüü''; mn, Нэрчүү, ''Nerchüü''; mnc, m=, v=Nibcu, a=Nibqu; zh, t=涅尔琴斯克(尼布楚), p=Niè'ěrqínsīkè (Níbùchǔ)) is a town and the administrative ce ...

, and south (slow but safe).

Early Russo-Chinese relations were difficult for three reasons: mutual ignorance, lack of a common language and the Chinese wish to treat the Russians as tributary barbarians, something that the Russians would not accept and did not fully understand. The language problem was solved when the Russians started sending Latin-speaking westerners who could speak to the

Jesuit missionaries

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders ...

in

Beijing

}

Beijing ( ; ; ), Chinese postal romanization, alternatively romanized as Peking ( ), is the Capital city, capital of the China, People's Republic of China. It is the center of power and development of the country. Beijing is the world's Li ...

.

In 1654

Fyodor Baykov Fyodor Isakovich Baykov (russian: Фёдор Исакович Байков, c. 1612 – c. 1663) was the first Russian envoy to China (1658). For background see History of Sino-Russian relations. Like many later Russian ambassadors to China ( Ni ...

was sent as the first ambassador, but his mission failed because he was unwilling to comply with the rules of Chinese diplomacy.

Setkul Ablin, a Central Asian in the Russian service travelled to Peking in 1655,1658 and 1668. It was apparently on his third trip that the Manchus realized that these people from the west were the same as those who were raiding the Amur. In 1670 the Nerchinsk voyvode sent Ignatiy Milovanov to Beijing (he was probably the first Russian to cross Manchuria). The next ambassador,

Nicholae Milescu

Nikolai Spathari (russian: Николай Гаврилович Спафарий, Nikolai Gavrilovich Spathari; 1636–1708), also known as Nicolae Milescu and Nicolae Milescu Spătaru (, first name also ''Neculai'', signing in Latin as Nicolaus ...

(1675–78) was also unsuccessful. After months of fruitless arguments, he was given a blunt lecture about the proper behavior of tributary barbarians and sent home. After the capture of

Albazin

Albazino (russian: Албазино́; ) is a village ('' selo'') in Skovorodinsky District of Amur Oblast, Russia, noted as the site of Albazin (), the first Russian settlement on the Amur River.

Before the arrival of Russians, Albazino belo ...

in 1685, a few Russians, commonly referred to as

Albazinians, settled in Beijing where they founded the

Chinese Orthodox Church

The Chinese Orthodox Church () is an autonomous Eastern Orthodox church in China. It was granted autonomy by its mother church, the Russian Orthodox Church, in 1957.

Earlier forms of Eastern Christianity

Christianity is said to have entered ...

.

Treaty of Nerchinsk (1689)

After their first victory at

Albazin

Albazino (russian: Албазино́; ) is a village ('' selo'') in Skovorodinsky District of Amur Oblast, Russia, noted as the site of Albazin (), the first Russian settlement on the Amur River.

Before the arrival of Russians, Albazino belo ...

in 1685, the Manchus sent two letters to the Tsar (in Latin) suggesting peace and demanding that Russian freebooters leave the Amur. The resulting negotiations led the

Treaty of Nerchinsk

The Treaty of Nerchinsk () of 1689 was the first treaty between the Tsardom of Russia and the Qing dynasty of China. The Russians gave up the area north of the Amur River as far as the Stanovoy Range and kept the area between the Argun River ...

. The Russians gave up the Amur valley but kept the land between Lake Baikal and the

Argun River. The treaty said nothing about what is now Mongolia since that area was then controlled by the

Oirat Zunghar Khanate.

After Nerchinsk regular caravans started running from Nerchinsk south to Peking. Some of the traders were Central Asians. The round trip took from ten to twelve months. The trade was apparently profitable to the Russians but less so to the Chinese. The Chinese were also disenchanted by the drunken brawls of the traders. In 1690 the Qing defeated the Oirats at the Great Wall and gained complete control over the Khalka Mongols in

Inner Mongolia

Inner Mongolia, officially the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, is an autonomous region of the People's Republic of China. Its border includes most of the length of China's border with the country of Mongolia. Inner Mongolia also accounts for a ...

. In 1696 the Oirats were defeated and driven back to the Altai Mountains (Kangxi Emperor in person with 80,000 troops in a battle near

Ulan Bator

Ulaanbaatar (; mn, Улаанбаатар, , "Red Hero"), previously anglicized as Ulan Bator, is the capital and most populous city of Mongolia. It is the coldest capital city in the world, on average. The municipality is located in north ce ...

). This opened the possibility of trade from Baikal southeastward and raised the problem of the northern border of Outer Mongolia. In March 1692

Eberhard Isbrand Ides Eberhard Isbrand Ides or Evert Ysbrants (Ysbrandszoon) Ides (1657–1708) was a Danish merchant, traveller and diplomat. Biography

Eberhard Isbrand Ides was from Holstein-Glückstadt.

By 1687, he settled in the German Quarter (''Nemetskaya slo ...

, a Dane in the Russian service, was sent from Nerchinsk as ambassador. The Manchus raised the question of the border west of the Argun. Ides returned to Moscow January 1695. From this time it was decided that the China trade would be a state monopoly. Four state caravans travelled from Moscow to Peking between 1697 and 1702. The fourth returned via

Selenginsk

Selenginsk (russian: Селенги́нск; bua, Сэлэнгын, ''Selengyn'', mn, Сэлэнгэ, ''Selenge'') is an urban locality (an urban-type settlement) in Kabansky District of the Republic of Buryatia, Russia, located at the head ...

(near Lake Baikal) in 90 days and bore a letter from the

Li-Fan Yuan suggesting that future trade use this route.

In 1712

Tulishen became the first Manchu or Chinese official to visit Russia (not counting earlier visits to Nerchinsk). He was mainly interested in the

Kalmyks

The Kalmyks ( Kalmyk: Хальмгуд, ''Xaľmgud'', Mongolian: Халимагууд, ''Halimaguud''; russian: Калмыки, translit=Kalmyki, archaically anglicised as ''Calmucks'') are a Mongolic ethnic group living mainly in Russia, w ...

along the Caspian Sea and how they might be used to deal with their cousins, the

Oirats

Oirats ( mn, Ойрад, ''Oirad'', or , Oird; xal-RU, Өөрд; zh, 瓦剌; in the past, also Eleuths) are the westernmost group of the Mongols whose ancestral home is in the Altai region of Siberia, Xinjiang and western Mongolia.

Histor ...

. He left Peking in June 1712 and reached Tobolsk in August 1713. Here he learned that he could not see the Tsar because of the Swedish wars. He went to Saratov and down the Volga to visit

Ayuka Khan of the Kalmyks. He returned to Peking in April 1715. His report, '

Yiyilu' of 'Record of Strange Regions' was long the main source of Chinese knowledge of Russia.

About this time the Kangxi Emperor began to put pressure on Saint Petersburg to delineate the Mongolian border west of the Argun, and several Russian caravans were held up. In July 1719 Lev Izmailov was sent as ambassador to Peking where he dealt with Tulishen, but the Chinese would not deal with the trade problem until the border was dealt with. Izmailov returned to Moscow in January 1722.

Lorents Lange was left as consul in Peking, but was expelled in July 1722. He returned to Selenginsk and sent reports to Petersburg.

Treaty of Kyakhta (1729)

Just before his death, Peter the Great decided to deal with the border problem. The result was the

Treaty of Kyakhta

The Treaty of Kyakhta (or Kiakhta),, ; , Xiao'erjing: بُلِيًاصِٿِ\ٿِاكْتُ تِيَوْيُؤ; mn, Хиагтын гэрээ, Hiagtiin geree, along with the Treaty of Nerchinsk (1689), regulated the relations between Imperial ...

. This defined the northern border of what is now Mongolia (except for

Tuva

Tuva (; russian: Тува́) or Tyva ( tyv, Тыва), officially the Republic of Tuva (russian: Респу́блика Тыва́, r=Respublika Tyva, p=rʲɪˈspublʲɪkə tɨˈva; tyv, Тыва Республика, translit=Tyva Respublika ...

) and opened up the

Kyakhta

Kyakhta (russian: Кя́хта, ; bua, Хяагта, Khiaagta, ; mn, Хиагт, Hiagt, ) is a town and the administrative center of Kyakhtinsky District in the Republic of Buryatia, Russia, located on the Kyakhta River near the Mongolia–Rus ...

caravan

Caravan or caravans may refer to:

Transport and travel

*Caravan (travellers), a group of travellers journeying together

**Caravanserai, a place where a caravan could stop

*Camel train, a convoy using camels as pack animals

*Convoy, a group of veh ...

trade southeast to Peking.

The needs for communication between the Russian and Chinese traders at Kyakhta and elsewhere resulted in the development of a pidgin, known to linguists as

Kyakhta Russian-Chinese Pidgin.

The treaties of Nerchinsk and Kyakhta were the basis of Russo-Chinese relations until the

Treaty of Aigun

The Treaty of Aigun (Russian: Айгунский договор; ) was an 1858 treaty between the Russian Empire and the Qing dynasty that established much of the modern border between the Russian Far East and China by ceding much of Manchur ...

in 1858. The fixed border helped the Chinese to gain full control of

Outer Mongolia

Outer Mongolia was the name of a territory in the Manchu people, Manchu-led Qing dynasty of China from 1691 to 1911. It corresponds to the modern-day independent state of Mongolia and the Russian republic of Tuva. The historical region gain ...

and annex

Xinjiang

Xinjiang, SASM/GNC: ''Xinjang''; zh, c=, p=Xīnjiāng; formerly romanized as Sinkiang (, ), officially the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (XUAR), is an autonomous region of the People's Republic of China (PRC), located in the northwes ...

by about 1755. Russo-Chinese trade shifted from Nerchinsk to Kyakhta and the Nerchensk trade died out by about 1750. (Local trade in this area shifted east to a border town called Tsurukhaitu on the Argun River).

Turkestan

After the Russians reached

Tobolsk

Tobolsk (russian: Тобо́льск) is a town in Tyumen Oblast, Russia, located at the confluence of the Tobol and Irtysh rivers. Founded in 1590, Tobolsk is the second-oldest Russian settlement east of the Ural Mountains in Asian Russia, ...

in 1585, it was natural to continue up the

Irtysh River

The Irtysh ( otk, 𐰼𐱅𐰾:𐰇𐰏𐰕𐰏, Ertis ügüzüg, mn, Эрчис мөрөн, ''Erchis mörön'', "erchleh", "twirl"; russian: Иртыш; kk, Ертіс, Ertis, ; Chinese: 额尔齐斯河, pinyin: ''É'ěrqísī hé'', Xiao'e ...

to the Kazakh steppes north of

Lake Balkhash to

Dzungaria

Dzungaria (; from the Mongolian words , meaning 'left hand') is a geographical subregion in Northwest China that corresponds to the northern half of Xinjiang. It is thus also known as Beijiang, which means "Northern Xinjiang". Bounded by the ...

and western Mongolia, which was the route used by Fyodor Baykov to reach China. In 1714,

Peter the Great

Peter I ( – ), most commonly known as Peter the Great,) or Pyotr Alekséyevich ( rus, Пётр Алексе́евич, p=ˈpʲɵtr ɐlʲɪˈksʲejɪvʲɪtɕ, , group=pron was a Russian monarch who ruled the Tsardom of Russia from t ...

sent Ivan Bukholts with 1,500 troops, including Swedish miners who were prisoners of war, up the Irtysh to

Lake Zaysan to search for gold. The next year, he ascended the river again with 3,000 workers to build a fort.

Tsewang Rabtan

Tsewang Rabtan (from ''Tsewang Rapten''; ; ; 1643–1727) was a Choros (Oirats) prince and the Khong Tayiji of the Dzungar Khanate from 1697 (following the death of his uncle and rival Galdan Boshugtu Khan) until his death in 1727. He was mar ...

(or Tseren-Donduk) of the

Zunghar Khanate attacked them and drove them back to Omsk. In 1720, an expedition, under Ivan Likharev, ascended the river and founded a permanent settlement at

Ust-Kamenogorsk

Oskemen ( kk, Өскемен, translit=Öskemen ), or Ust-Kamenogorsk (russian: Усть-Каменого́рск), is the administrative center of East Kazakhstan Region of Kazakhstan. Population:

Name

The city has two official names. In th ...

just west of the lake. Meanwhile, the Zunghars were severely defeated by the Manchus and driven out of Tibet. In 1721 to 1723, Peter sent Ivan Unkovsky to attempt to discuss an alliance. A major reason for the failure was that Lorents Lange at Selenginsk had turned over a number of Mongol refugees to the Manchus as part of the buildup to the Treaty of Kyakhta. In 1755, the Qing destroyed the remnants of the Zunghar Khanate, creating a Russo-Chinese border in

Xinjiang

Xinjiang, SASM/GNC: ''Xinjang''; zh, c=, p=Xīnjiāng; formerly romanized as Sinkiang (, ), officially the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (XUAR), is an autonomous region of the People's Republic of China (PRC), located in the northwes ...

. The area did not become active again until the

Russian conquest of Turkestan

The partially successful conquest of Central Asia by the Russian Empire took place in the second half of the nineteenth century. The land that became Russian Turkestan and later Soviet Central Asia is now divided between Kazakhstan in the north ...

.

1755–1917

Meeting in Central Asia

As the Chinese Empire

established its control over

Xinjiang

Xinjiang, SASM/GNC: ''Xinjang''; zh, c=, p=Xīnjiāng; formerly romanized as Sinkiang (, ), officially the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (XUAR), is an autonomous region of the People's Republic of China (PRC), located in the northwes ...

in the 1750s, and the Russian Empire expanded into

Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan, officially the Republic of Kazakhstan, is a transcontinental country located mainly in Central Asia and partly in Eastern Europe. It borders Russia to the north and west, China to the east, Kyrgyzstan to the southeast, Uzbeki ...

at the beginning and in the middle of the 19th century, the two empires' areas of control met in what is today eastern Kazakhstan and Western Xinjiang. The 1851

Treaty of Kulja

The Treaty of Kulja (also spelled Kuldja) () was an unequal treaty between Qing China and the Russian Empire, signed in 1851, opening Kulja ( Huiyuan and later Ningyuan) and Chuguchak to Sino-Russian trade. Prepared by the first Russian consul to ...

legalized trade between both countries in the region.

Russian encroachment

In 1858, during the

Second Opium War

The Second Opium War (), also known as the Second Anglo-Sino War, the Second China War, the Arrow War, or the Anglo-French expedition to China, was a colonial war lasting from 1856 to 1860, which pitted the British Empire#Britain's imperial ...

, China grew increasingly weaker as the "

Sick man of Asia" while Russia

strengthened and eventually annexed the north bank of the Amur River and the coast down to the Korean border in the "

Unequal Treaties

Unequal treaty is the name given by the Chinese to a series of treaties signed during the 19th and early 20th centuries, between China (mostly referring to the Qing dynasty) and various Western powers (specifically the British Empire, France, the ...

" of

Treaty of Aigun

The Treaty of Aigun (Russian: Айгунский договор; ) was an 1858 treaty between the Russian Empire and the Qing dynasty that established much of the modern border between the Russian Far East and China by ceding much of Manchur ...

(1858) and the

Convention of Peking

The Convention of Peking or First Convention of Peking is an agreement comprising three distinct treaties concluded between the Qing dynasty of China and Great Britain, France, and the Russian Empire in 1860. In China, they are regarded as amo ...

(1860). Russia and Japan gained control of

Sakhalin

Sakhalin ( rus, Сахали́н, r=Sakhalín, p=səxɐˈlʲin; ja, 樺太 ''Karafuto''; zh, c=, p=Kùyèdǎo, s=库页岛, t=庫頁島; Manchu: ᠰᠠᡥᠠᠯᡳᠶᠠᠨ, ''Sahaliyan''; Orok: Бугата на̄, ''Bugata nā''; Nivkh ...

Island.

The Manza War (1868) was the first attempt by Russia to expel the Chinese from the territory that it controlled. Hostilities broke out around

Peter the Great Gulf

The Peter the Great Gulf (Russian: Залив Петра Великого) is a gulf on the southern coast of Primorsky Krai, Russia, and the largest gulf of the Sea of Japan. The gulf extends for from the Russian-North Korean border at the mo ...

,

Vladivostok

Vladivostok ( rus, Владивосто́к, a=Владивосток.ogg, p=vɫədʲɪvɐˈstok) is the largest city and the administrative center of Primorsky Krai, Russia. The city is located around the Golden Horn Bay on the Sea of Japan, ...

, when the Russians tried to shut off gold mining operations and to expel Chinese workers there. The Chinese resisted a Russian attempt to take Askold Island and in response, two Russian military stations and three Russian towns were attacked by the Chinese, and the Russians failed to oust the Chinese.

Russia's special status

Unlike other Western countries, who deal with the Qing court on a monarch to monarch basis, Sino–Russian relations were governed by administrative bodies, the Qing's Board of Foreign Affairs (Lifan Yuan) and the Russian Senate (Senat). Unlike the Netherlands and Portugal in the 18th century, who were considered part of the tribute system, Russia was able to trade directly with Beijing, and their relations were under the jurisdiction of Mongolian and Manchu border officials. Russia established an Orthodox mission in Beijing in the early 18th century, and was able to escape the anti Christian persecutions of the Qing dynasty.

The Great Game and the 1870s Xinjiang border Dispute

A British observer, Demetrius Charles de Kavanagh Boulger, suggested a British-Chinese alliance to check Russian expansion in

Central Asia

Central Asia, also known as Middle Asia, is a region of Asia that stretches from the Caspian Sea in the west to western China and Mongolia in the east, and from Afghanistan and Iran in the south to Russia in the north. It includes the fo ...

.

During the Ili crisis, when Qing China threatened to go to war against Russia over the Russian occupation of Ili, a British officer,

Charles George Gordon

Major-General Charles George Gordon CB (28 January 1833 – 26 January 1885), also known as Chinese Gordon, Gordon Pasha, and Gordon of Khartoum, was a British Army officer and administrator. He saw action in the Crimean War as an officer in ...

, was sent to China by Britain to advise China on its military options against Russia in a potential war between China and Russia.

The Russians occupied the city of Kuldja, in Xinjiang, during the

Dungan revolt (1862–1877)

The Dungan Revolt (1862–1877) or Tongzhi Hui Revolt (, Xiao'erjing: تُجِ خُوِ لُوًا, dng, Тунҗы Хуэй Луан) or Hui (Muslim) Minorities War was a war fought in 19th-century western China, mostly during the reig ...

. After General Zuo Zongtang and his

Xiang Army crushed the rebels, they demanded for Russia to return the occupied regions.

General

Zuo Zongtang

Zuo Zongtang, Marquis Kejing ( also spelled Tso Tsung-t'ang; ; November 10, 1812 – September 5, 1885), sometimes referred to as General Tso, was a Chinese statesman and military leader of the late Qing dynasty.

Born in Xiangyin County, ...

was outspoken in calling for war against Russia and hoped to settle the matter by attacking Russian forces in Xinjiang with his Xiang army. In 1878, tension increased in Xinjiang, and Zuo massed Chinese troops toward Russian-occupied Kuldja. Chinese forces also fired on Russian expeditionary forces originating from Yart Vernaic, expelled them, and caused a Russian retreat.

The Russians observed that the Chinese building up their arsenal of modern weapons during the Ili crisis since they had bought thousands of rifles from Germany. In 1880, massive amounts of military equipment and rifles were shipped via boats to China from Antwerp as China purchased torpedoes, artillery, and 260,260 modern rifles from Europe.

A Russian military observer, D. V. Putiatia, visited China in 1888 and found that in

Northeastern China

Northeast China or Northeastern China () is a geographical region of China, which is often referred to as "Manchuria" or "Inner Manchuria" by surrounding countries and the West. It usually corresponds specifically to the three provinces east of ...

(Manchuria), along the Chinese-Russian border, the Chinese soldiers could become adept at "European tactics" under certain circumstances and were armed with modern weapons, like Krupp artillery, Winchester carbines, and Mauser rifles.

Compared to the Russian-controlled areas, more benefits were given to the Muslim Kirghiz in the Chinese-controlled areas. Russian settlers fought against the Muslim nomadic Kirghiz, which led the Russians to believe that the Kirghiz would be a liability in any conflict against China. The Muslim Kirghiz were sure that a war would have China defeat Russia.

The Qing dynasty forced Russia to hand over disputed territory in the

Treaty of Saint Petersburg (1881)

The Treaty of Saint Petersburg (1881) (), also known as Treaty of Ili (), was a treaty between the Russian Empire and the Qing dynasty that was signed in Saint Petersburg, Russia, on . It provided for the return to China of the eastern part of ...

in what was widely seen by the west as a diplomatic victory for the Qing. Russia acknowledged that China could pose a serious military threat.

Mass media in the West portrayed China as a rising military power because of its modernization programs and as a major threat to the West. They even invoked fears that China would manage to conquer western colonies like

Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands. With an area of , Australia is the largest country by ...

.

Russian sinologists, the Russian media, the threat of internal rebellion, the pariah status inflicted by the

Congress of Berlin

The Congress of Berlin (13 June – 13 July 1878) was a diplomatic conference to reorganise the states in the Balkan Peninsula after the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–78, which had been won by Russia against the Ottoman Empire. Represented at th ...

, and the negative state of the

Russian economy

The economy of Russia has gradually transformed from a planned economy into a mixed market-oriented economy.

—Rosefielde, Steven, and Natalia Vennikova. “Fiscal Federalism in Russia: A Critique of the OECD Proposals.” Cambridge Journa ...

all led Russia to concede and negotiate with China in Saint Petersburg and to return most of Ili to China.

Historians have judged the Qing dynasty's vulnerability and weakness to foreign imperialism in the 19th century to be based mainly on its maritime naval weakness although it achieved military success against Westerners on land. Historian Edward L. Dreyer stated, "China's nineteenth-century humiliations were strongly related to her weakness and failure at sea. At the start of the Opium War, China had no unified navy and no sense of how vulnerable she was to attack from the sea; British forces sailed and steamed wherever they wanted to go.... In the Arrow War (1856–60), the Chinese had no way to prevent the Anglo-French expedition of 1860 from sailing into the Gulf of Zhili and landing as near as possible to Beijing. Meanwhile, new but not exactly modern Chinese armies suppressed the midcentury rebellions,

bluffed Russia into a peaceful settlement of disputed frontiers in Central Asia, and

defeated the French forces on land in the Sino–French War (1884–85). But the defeat of the fleet, and the resulting threat to steamship traffic to Taiwan, forced China to conclude peace on unfavorable terms."

According to Henry Hugh Peter Deasy in 1901 on the people of

Xinjiang

Xinjiang, SASM/GNC: ''Xinjang''; zh, c=, p=Xīnjiāng; formerly romanized as Sinkiang (, ), officially the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (XUAR), is an autonomous region of the People's Republic of China (PRC), located in the northwes ...

: "insurrection is about the last course to which the natives would of their own accord resort. Any riots and disturbances which occur are got up by the officials for the purpose of inflicting injury on foreigners. The population have no fighting courage, no arms, no leaders, are totally incapable of combined action, and, so far as the government of their own country is concerned. may be regarded as of no account. They have been squeezed to the utmost, but would prefer to remain under the dominion of China. If they are questioned, they say 'The Chinese plunder us, but they do not drive and hustle us, and we can do as we please.' This opinion agrees with that of the Andijanis, or natives of Russian Turkestan, who assert that Russian rule is much disliked among them, owing to the harassing administration to which they are subjected."

1890s alliance

Russian Finance Minister

Sergei Witte

Count Sergei Yulyevich Witte (; ), also known as Sergius Witte, was a Russian statesman who served as the first prime minister of the Russian Empire, replacing the tsar as head of the government. Neither a liberal nor a conservative, he attract ...

controlled East Asian policy in the 1890s. His goal was the peaceful expansion of trade and the increase of Russian influence over China. Japan's greatly-expanded and -modernized military easily defeated the antiquated Chinese forces in the

First Sino–Japanese War (1894–1895). Russia now faced the choice of working with Japan, which had fairly good relations for some years, or acting as protector of China against Japan. Witte chose the latter policy, and in 1894 Russia joined Britain and France in forcing Japan to soften the peace terms that it had imposed on China. Japan was forced to return the

Liaodong Peninsula

The Liaodong Peninsula (also Liaotung Peninsula, ) is a peninsula in southern Liaoning province in Northeast China, and makes up the southwestern coastal half of the Liaodong region. It is located between the mouths of the Daliao River ...

and

Port Arthur (both territories in southeastern Manchuria, a Chinese province) to China. The new Russian role angered Tokyo, which decided that Russia was the main enemy in its quest to control Manchuria, Korea, and China. Witte underestimated Japan's growing economic and military power and exaggerated Russia's military prowess.

Russia concluded an alliance with China in 1896 by the

Li–Lobanov Treaty, with China a junior partner and practically a protectorate. It led in 1898 to an occupation and administration by Russian personnel and police of the entire Liaodong Peninsula and to a fortification of the ice-free Port Arthur. Since Russia was receiving large-loans from France, Witte used some of the funds to establish the

Russo-Chinese Bank, which provided 100 million rubles for China to fund the reparations that it owed to Japan. Along with the International Commercial Bank of St-Petersburg, it became the conduit through which Russian capital was funneled into East Asia. Furthermore, the Russo-Chinese Bank bankrolled the Russian government's policies towards Manchuria and Korea. That enormous leverage allowed Russia to make strategic leases of key military ports and defense stations. The Chinese government ceded its concession rights for building and owning the new

Chinese Eastern Railway

The Chinese Eastern Railway or CER (, russian: Китайско-Восточная железная дорога, or , ''Kitaysko-Vostochnaya Zheleznaya Doroga'' or ''KVZhD''), is the historical name for a railway system in Northeast China (als ...

, which was to cross northern Manchuria from the west to the east, to link Siberia with Vladivostok, and strengthen the military capabilities of the Russian forces in the Far East greatly. It was built in 1898 to 1903 and operated by the Russo-Chinese Bank and allowed Russia to become economically dominant in Manchuria, which was still nominally controlled by Peking.

In 1899, the

Boxer Rebellion

The Boxer Rebellion, also known as the Boxer Uprising, the Boxer Insurrection, or the Yihetuan Movement, was an Xenophobia, anti-foreign, anti-colonialism, anti-colonial, and Persecution of Christians#China, anti-Christian uprising in China ...

broke out with Chinese nativist attacks on all foreigners. A large coalition of eleven major Western powers, led by Russia and Japan, sent an army to relieve their diplomatic missions in

Peking

}

Beijing ( ; ; ), alternatively romanized as Peking ( ), is the capital of the People's Republic of China. It is the center of power and development of the country. Beijing is the world's most populous national capital city, with over 21 ...

and to take control of the Chinese capital. The Russian government used it as an opportunity to bring a substantial

army into Manchuria, which became a fully-incorporated outpost of Russia in 1900. Japan started to prepare for a war with Russia over Korea and Manchuria.

Russo-Japanese War

Chinese

Honghuzi bandits were nomads who came from China, roamed the area around Manchuria and the Russo-Chinese border, and raided Russian settlers in the Far East from 1870 to 1920.

Revolutions

Both countries saw their monarchies abolished during the 1910s, the Chinese Qing dynasty in 1912, following the

Xinhai Revolution

The 1911 Revolution, also known as the Xinhai Revolution or Hsinhai Revolution, ended China's last imperial dynasty, the Manchu-led Qing dynasty, and led to the establishment of the Republic of China. The revolution was the culmination of ...

, and the Russian

Romanov dynasty

The House of Romanov (also transcribed Romanoff; rus, Романовы, Románovy, rɐˈmanəvɨ) was the reigning imperial house of Russia from 1613 to 1917. They achieved prominence after the Tsarina, Anastasia Romanova, was married to ...

in 1917, following the

February Revolution

The February Revolution ( rus, Февра́льская револю́ция, r=Fevral'skaya revolyutsiya, p=fʲɪvˈralʲskəjə rʲɪvɐˈlʲutsɨjə), known in Soviet historiography as the February Bourgeois Democratic Revolution and some ...

.

Soviet Union, Republic of China, People's Republic of China

Russian Civil War and Mongolia

The

Beiyang government

The Beiyang government (), officially the Republic of China (), sometimes spelled Peiyang Government, refers to the government of the Republic of China which sat in its capital Peking (Beijing) between 1912 and 1928. It was internationally ...

, in

Northern China

Northern China () and Southern China () are two approximate regions within China. The exact boundary between these two regions is not precisely defined and only serve to depict where there appears to be regional differences between the climate ...

, joined the

Allied intervention in the Russian Civil War

Allied intervention in the Russian Civil War or Allied Powers intervention in the Russian Civil War consisted of a series of multi-national military expeditions which began in 1918. The Allies first had the goal of helping the Czechoslovak Leg ...

. It sent 2,300 troops in

Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a part ...

and

North Russia

Russian North (russian: Русский Север) is an ethnocultural region situated in the northwestern part of Russia. It spans the regions of Arkhangelsk Oblast, the Republic of Karelia, Komi Republic, Vologda Oblast and Nenets Autonomous O ...

in 1918 after the request by the Chinese community in the area.

Mongolia

Mongolia; Mongolian script: , , ; lit. "Mongol Nation" or "State of Mongolia" () is a landlocked country in East Asia, bordered by Russia to the north and China to the south. It covers an area of , with a population of just 3.3 million ...

and

Tuva

Tuva (; russian: Тува́) or Tyva ( tyv, Тыва), officially the Republic of Tuva (russian: Респу́блика Тыва́, r=Respublika Tyva, p=rʲɪˈspublʲɪkə tɨˈva; tyv, Тыва Республика, translit=Tyva Respublika ...

became contested territories. After being

occupied

' ( Norwegian: ') is a Norwegian political thriller TV series that premiered on TV2 on 5 October 2015. Based on an original idea by Jo Nesbø, the series is co-created with Karianne Lund and Erik Skjoldbjærg. Season 2 premiered on 10 Octobe ...

by Chinese General

Xu Shuzheng in 1919 and then by the

Russian White

general turned independent warlord,

Ungern von Sternberg

Nikolai Robert Maximilian Freiherr von Ungern-Sternberg (russian: link=no, Роман Фёдорович фон Унгерн-Штернберг, translit=Roman Fedorovich fon Ungern-Shternberg; 10 January 1886 – 15 September 1921), often refer ...

, in 1920,

Soviet troops, with the support of

Mongolian guerrillas

Guerrilla warfare is a form of irregular warfare in which small groups of combatants, such as paramilitary personnel, armed civilians, or irregulars, use military tactics including ambushes, sabotage, raids, petty warfare, hit-and-run tacti ...

, led by

Damdin Sükhbaatar, defeated the White warlord and established a new pro-Soviet Mongolian

client state

A client state, in international relations, is a state that is economically, politically, and/or militarily subordinate to another more powerful state (called the "controlling state"). A client state may variously be described as satellite sta ...

. By 1924, it had become the

Mongolian People's Republic

The Mongolian People's Republic ( mn, Бүгд Найрамдах Монгол Ард Улс, БНМАУ; , ''BNMAU''; ) was a socialist state which existed from 1924 to 1992, located in the historical region of Outer Mongolia in East Asia. It w ...

.

KMT, CCP, and the Chinese Civil War

Soviet Foreign Minister

Georgy Chicherin

Georgy Vasilyevich Chicherin (24 November 1872 – 7 July 1936), also spelled Tchitcherin, was a Russian Marxist revolutionary and a Soviet politician who served as the first People's Commissar for Foreign Affairs in the Soviet government from ...

played a major role in establishing formal relations with China in 1924, and in designing the Kremlin's China policy. He focused on the Chinese Eastern Railway, Manchuria, and the Mongolian issue. In 1921, the Soviet Union began supporting the

Kuomintang

The Kuomintang (KMT), also referred to as the Guomindang (GMD), the Nationalist Party of China (NPC) or the Chinese Nationalist Party (CNP), is a major political party in the Republic of China, initially on the Chinese mainland and in Ta ...

, and in 1923, the

Comintern

The Communist International (Comintern), also known as the Third International, was a Soviet-controlled international organization founded in 1919 that advocated world communism. The Comintern resolved at its Second Congress to "struggle by ...

instructed the CCP to sign a military treaty with the KMT. But in 1926, KMT leader,

Chiang Kai-shek

Chiang Kai-shek (31 October 1887 – 5 April 1975), also known as Chiang Chung-cheng and Jiang Jieshi, was a Chinese Nationalist politician, revolutionary, and military leader who served as the leader of the Republic of China (ROC) from 1928 ...

abruptly dismissed his Soviet advisers, and imposed restrictions on CCP participation in the government. By 1927, when the

Northern Expedition

The Northern Expedition was a military campaign launched by the National Revolutionary Army (NRA) of the Kuomintang (KMT), also known as the "Chinese Nationalist Party", against the Beiyang government and other regional warlords in 1926. The ...

was nearly concluded, Chiang purged the CCP from the KMT-CCP alliance, resulting in the

Chinese Civil War

The Chinese Civil War was fought between the Kuomintang-led government of the Republic of China and forces of the Chinese Communist Party, continuing intermittently since 1 August 1927 until 7 December 1949 with a Communist victory on main ...

which was to last until 1950, a few months after the

People's Republic of China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, most populous country, with a Population of China, population exceeding 1.4 billion, slig ...

, led by

Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong pronounced ; also Romanization of Chinese, romanised traditionally as Mao Tse-tung. (26 December 1893 – 9 September 1976), also known as Chairman Mao, was a Chinese communist revolutionary who was the List of national founde ...

, was proclaimed. During the war, some Soviet support was given to the CCP, who in 1934 were dealt a crushing blow when the KMT brought an end to the

Chinese Soviet Republic

The Chinese Soviet Republic (CSR) was an East Asian proto-state in China, proclaimed on 7 November 1931 by Chinese communist leaders Mao Zedong and Zhu De in the early stages of the Chinese Civil War. The discontiguous territories of t ...

, beginning the CCP's

Long March

The Long March (, lit. ''Long Expedition'') was a military retreat undertaken by the Red Army of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), the forerunner of the People's Liberation Army, to evade the pursuit of the National Army of the Chinese ...

to

Shaanxi

Shaanxi (alternatively Shensi, see § Name) is a landlocked province of China. Officially part of Northwest China, it borders the province-level divisions of Shanxi (NE, E), Henan (E), Hubei (SE), Chongqing (S), Sichuan (SW), Gansu (W), N ...

.

Second Sino–Japanese War and World War II

In 1931, the

Empire of Japan

The also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was a historical nation-state and great power that existed from the Meiji Restoration in 1868 until the enactment of the post-World War II 1947 constitution and subsequent form ...

invaded

Manchuria

Manchuria is an exonym (derived from the endo demonym " Manchu") for a historical and geographic region in Northeast Asia encompassing the entirety of present-day Northeast China (Inner Manchuria) and parts of the Russian Far East (Outer M ...

and created the

puppet state

A puppet state, puppet régime, puppet government or dummy government, is a state that is ''de jure'' independent but ''de facto'' completely dependent upon an outside power and subject to its orders.Compare: Puppet states have nominal sove ...

of

Manchukuo

Manchukuo, officially the State of Manchuria prior to 1934 and the Empire of (Great) Manchuria after 1934, was a puppet state of the Empire of Japan in Manchuria from 1932 until 1945. It was founded as a republic in 1932 after the Japanese ...

(1932), which signalled the beginning of the

Second Sino–Japanese War. In 1937, a month after the

Marco Polo Bridge Incident

The Marco Polo Bridge Incident, also known as the Lugou Bridge Incident () or the July 7 Incident (), was a July 1937 battle between China's National Revolutionary Army and the Imperial Japanese Army.

Since the Japanese invasion of Manchuri ...

, the Soviet Union established a

non-aggression pact

A non-aggression pact or neutrality pact is a treaty between two or more states/countries that includes a promise by the signatories not to engage in military action against each other. Such treaties may be described by other names, such as a tr ...

with the Republic of China. During the

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

-period, the two countries suffered more losses than any other country, with China (in the

Second Sino–Japanese war) losing over 35 million and the Soviet Union 27 million people.

Joint-victory over Imperial Japan

On August 8, 1945, three months after

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

surrendered, and on the week of the

American

American(s) may refer to:

* American, something of, from, or related to the United States of America, commonly known as the "United States" or "America"

** Americans, citizens and nationals of the United States of America

** American ancestry, pe ...

atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

The United States detonated two atomic bombs over the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on 6 and 9 August 1945, respectively. The two bombings killed between 129,000 and 226,000 people, most of whom were civilians, and remain the onl ...

(August 6 and 9), the Soviet Union launched the

Soviet invasion of Manchuria

The Soviet invasion of Manchuria, formally known as the Manchurian strategic offensive operation (russian: Манчжурская стратегическая наступательная операция, Manchzhurskaya Strategicheskaya Nastu ...

, a massive military operation mobilizing 1.5 million soldiers against one million

Kwantung Army

''Kantō-gun''

, image = Kwantung Army Headquarters.JPG

, image_size = 300px

, caption = Kwantung Army headquarters in Hsinking, Manchukuo

, dates = April ...

troops, the last remaining

Japanese military

The Japan Self-Defense Forces ( ja, 自衛隊, Jieitai; abbreviated JSDF), also informally known as the Japanese Armed Forces, are the unified ''de facto''Since Article 9 of the Japanese Constitution outlaws the formation of armed forces, the ...

presence. Soviet forces won a decisive victory while the Kwantung suffered massive casualties, with 700,000 having surrendered. The Soviet Union distributed some of the weapons of the captured Kwantung Army to the CCP, who would go on to battle the KMT in the Chinese Civil War.

Independence of Mongolia

The

China, Soviet Union: Treaty of Friendship and Alliance was signed by the

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

and the

Republic of China

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the northeas ...

. It stated that possible

Mongolian independence was in exchange for the Soviets' failure to support the communists in China.

War of Liberation and the People's Republic of China

Between 1946 and 1950, the CCP was increasingly enjoying massive support from the Chinese people in the "War of Liberation" and effectively implemented a

people's war

People's war (Chinese: 人民战争), also called protracted people's war, is a Maoist military strategy. First developed by the Chinese communist revolutionary leader Mao Zedong (1893–1976), the basic concept behind people's war is to main ...

, but the KMT became increasingly isolated and only belatedly attempted to stem corruption and to introduce popular reforms. On October 1, 1949, the People's Republic of China was proclaimed by Mao Zedong, and by May 1950, the civil war was brought to an end by the

Battle of Kuningtou

The Battle of Kuningtou or Battle of Guningtou (), also known as the Battle of Kinmen (), was a battle fought over Kinmen in the Taiwan Strait during the Chinese Civil War in 1949. The failure of the Communists to take the island left it in the ...

, which saw the KMT expelled from

Mainland China

"Mainland China" is a geopolitical term defined as the territory governed by the China, People's Republic of China (including islands like Hainan or Chongming Island, Chongming), excluding dependent territories of the PRC, and other territorie ...

but remaining in control of

Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the no ...

. With the creation of the People's Republic of China, the supreme political authority in the two countries became centered in two communist parties, which both espoused revolutionary

Marxist-Leninist ideology: the CCP and the

Communist Party of the Soviet Union

" Hymn of the Bolshevik Party"

, headquarters = 4 Staraya Square, Moscow

, general_secretary = Vladimir Lenin (first) Mikhail Gorbachev (last)

, founded =

, banned =

, founder = Vladimir Lenin

, newspape ...

.

In 1951, Chinese Muslim General

Bai Chongxi

Bai Chongxi (18 March 1893 – 2 December 1966; , , Xiao'erjing: ) was a Chinese general in the National Revolutionary Army of the Republic of China (ROC) and a prominent Chinese Nationalist leader. He was of Hui ethnicity and of the Musli ...

made a speech in Taiwan to the entire

Muslim world

The terms Muslim world and Islamic world commonly refer to the Islamic community, which is also known as the Ummah. This consists of all those who adhere to the religious beliefs and laws of Islam or to societies in which Islam is practiced. I ...

that called for a war against the Soviets and the avoiding of Indian Prime Minister

Jawaharlal Nehru

Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru (; ; ; 14 November 1889 – 27 May 1964) was an Indian Anti-colonial nationalism, anti-colonial nationalist, secular humanist, social democrat—

*

*

*

* and author who was a central figure in India du ...

, who was accused of being blind to

Soviet imperialism.

From camaraderie to the Sino–Soviet Split

After the PRC was proclaimed, the

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

became its closest ally for several years. Soviet design, equipment, and skilled labour were sent out to help the

Industrialization

Industrialisation ( alternatively spelled industrialization) is the period of social and economic change that transforms a human group from an agrarian society into an industrial society. This involves an extensive re-organisation of an econo ...

and the

modernization

Modernization theory is used to explain the process of modernization within societies. The "classical" theories of modernization of the 1950s and 1960s drew on sociological analyses of Karl Marx, Emile Durkheim and a partial reading of Max Weber, ...

of the PRC. In the 1960s, relations became deeply strained by the

Sino–Soviet Split. In military terms, there was the low-level

Sino–Soviet border conflict.

The split was ideological and forced communist parties around the world to take sides. Many of them split, and the pro-Soviet communists were battling the pro-Chinese communists for local control of global communis. The split quickly made a dead letter of the 1950 alliance between Moscow and Beijing, destroyed the socialist camp's unity, and affected the world balance of power. Internally, it encouraged Mao to plunge China into the

Cultural Revolution

The Cultural Revolution, formally known as the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, was a sociopolitical movement in the People's Republic of China (PRC) launched by Mao Zedong in 1966, and lasting until his death in 1976. Its stated goa ...

to expunge traces of Soviet ways of thinking. The quarrel began in 1958, after several years of close relations. Mao was always loyal to Stalin, and

Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and chairman of the country's Council of Ministers from 1958 to 1964. During his rule, Khrushchev s ...

felt insulted. However, when the

Warsaw Pact

The Warsaw Pact (WP) or Treaty of Warsaw, formally the Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Mutual Assistance, was a collective defense treaty signed in Warsaw, Poland, between the Soviet Union and seven other Eastern Bloc socialist republi ...

crushed the dissident movements in

Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural, and socio-economic connotations. The vast majority of the region is covered by Russia, whi ...

in 1956, Beijing was pleased that Moscow had apparently realized the dangers of

de-Stalinization

De-Stalinization (russian: десталинизация, translit=destalinizatsiya) comprised a series of political reforms in the Soviet Union after the death of long-time leader Joseph Stalin in 1953, and the thaw brought about by ascension ...

and would no longer tolerate independence or encourage revisionism. Beijing was also pleased that the success of the Soviet Union in the space race (the original Sputniks) demonstrated that the international communist movement had caught up in high technology with the West. Mao argued that as far as all-out

nuclear war

Nuclear warfare, also known as atomic warfare, is a theoretical military conflict or prepared political strategy that deploys nuclear weaponry. Nuclear weapons are weapons of mass destruction; in contrast to conventional warfare, nuclear wa ...

was concerned, the human race would not be destroyed, but a brave new communist world would arise from the ashes of imperialism. That attitude troubled Moscow, which had a more realistic view of the utter disasters that would accompany a nuclear war. Three major issues suddenly became critical in dividing the two nations: Taiwan, India, and China's

Great Leap Forward

The Great Leap Forward (Second Five Year Plan) of the People's Republic of China (PRC) was an economic and social campaign led by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) from 1958 to 1962. CCP Chairman Mao Zedong launched the campaign to reconstr ...

. Although Moscow supported Beijing's position of Taiwan entirely belonging to China, it demanded to be forewarned of any invasion or serious threat that would bring an American intervention. Beijing refused, and the Chinese bombardment of the island of

Quemoy in August 1958 escalated the tensions. Moscow was cultivating India, both as a major purchaser of munitions and as a strategically-critical ally. However China escalated its threats to the northern fringes of India, especially from Tibet, and was building a militarily significant road system that would reach disputed areas along the border. Moscow clearly favored India, and Beijing felt betrayed as a result.

By far, the major ideological issue was the Great Leap Forward, which represented the Chinese rejection of the Soviet form of economic development. The Soviets were deeply resentful, especially since they had spent heavily to supply China with cutting-edge technology, even including some nuclear tech. The Soviets withdrew their vital technicians and economic and military aid. Khrushchev was increasingly crude and intemperate in ridiculing China and Mao to both communist and noncommunist audiences. China responded through its official propaganda network of rejecting Moscow's claim to Lenin's heritage. Beijing insisted that it was the true inheritor of the great Leninist tradition.

At one major meeting of communist parties, Khrushchev personally attacked Mao as an ultraleftist and a left revisionist and compared him to Stalin for dangerous egotism. The conflict was now out of control and was increasingly fought out in 81 communist parties around the world. The final split came in July 1963, after 50,000 refugees escaped from

Sinkiang

Xinjiang, SASM/GNC: ''Xinjang''; zh, c=, p=Xīnjiāng; formerly romanized as Sinkiang (, ), officially the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (XUAR), is an autonomous region of the People's Republic of China (PRC), located in the northwest ...

, in

Western China

Western China (, or rarely ) is the west of China. In the definition of the Chinese government, Western China covers one municipality ( Chongqing), six provinces (Sichuan, Guizhou, Yunnan, Shaanxi, Gansu, and Qinghai), and three autonomou ...

, to Soviet territory to escape persecution. China ridiculed the Soviet incompetence in the

Cuban Missile Crisis