History of Shetland on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The History of Shetland concerns the

Due to building in stone on virtually treeless islands—a practice dating to at least the early

Due to building in stone on virtually treeless islands—a practice dating to at least the early  The same site provides dates for early Neolithic activity, and finds at Scourd of Brouster in

The same site provides dates for early Neolithic activity, and finds at Scourd of Brouster in

By the end of the 9th century the

By the end of the 9th century the

When

When

In the 14th century Norway still treated Orkney and Shetland as a Norwegian province, but Scottish influence was growing, and in 1379 the Scottish earl Henry Sinclair took control of Orkney on behalf of the Norwegian king Håkon VI Magnusson. In 1384 Norway was severely weakened by the

In the 14th century Norway still treated Orkney and Shetland as a Norwegian province, but Scottish influence was growing, and in 1379 the Scottish earl Henry Sinclair took control of Orkney on behalf of the Norwegian king Håkon VI Magnusson. In 1384 Norway was severely weakened by the

/ref> With the passing of the Several attempts were made during the 17th and 18th centuries to redeem the islands, without success. Following a legal dispute with William, Earl of Morton, who held the estates of Orkney and Shetland, Charles II ratified the pawning document by a Scottish

Several attempts were made during the 17th and 18th centuries to redeem the islands, without success. Following a legal dispute with William, Earl of Morton, who held the estates of Orkney and Shetland, Charles II ratified the pawning document by a Scottish

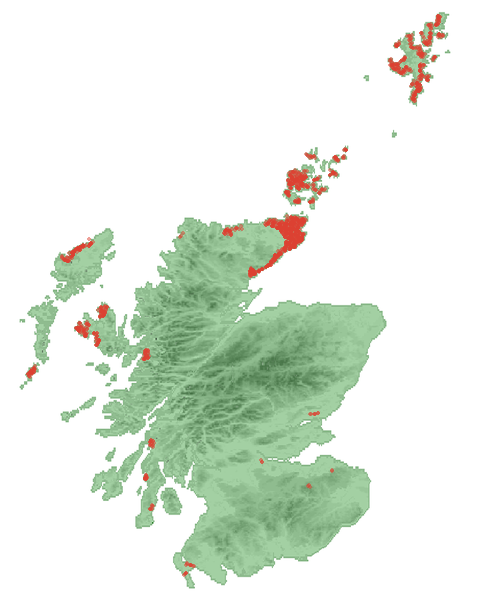

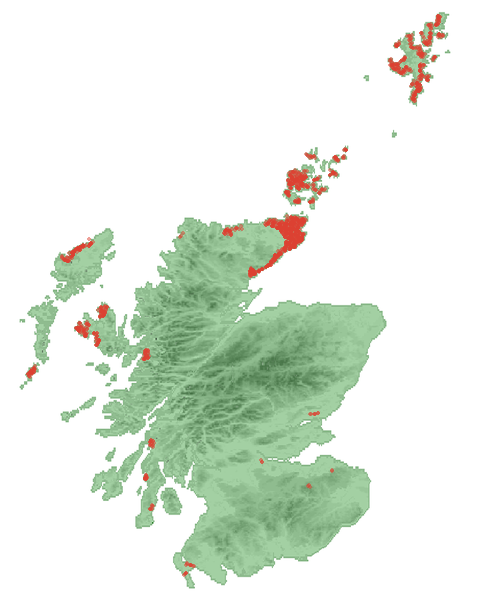

Historical, archaeological, place-name and linguistic evidence indicates Norse cultural dominance of Shetland during the Viking period. A few place names might have Pictish origin, but this is disputed. Several genetic studies have been conducted investigating the genetic makeup of the islands' population today in order to establish its origin. Shetlanders are less than half Scandinavian in origin. They have almost identical proportions of Scandinavian matrilineal and patrilineal ancestry (ca 44%), suggesting that the islands were settled by both men and women, as seems to have been the case in Orkney and the northern and western coastline of Scotland, but areas of the British Isles further away from Scandinavia show signs of being colonised primarily by males who found local wives.

Historical, archaeological, place-name and linguistic evidence indicates Norse cultural dominance of Shetland during the Viking period. A few place names might have Pictish origin, but this is disputed. Several genetic studies have been conducted investigating the genetic makeup of the islands' population today in order to establish its origin. Shetlanders are less than half Scandinavian in origin. They have almost identical proportions of Scandinavian matrilineal and patrilineal ancestry (ca 44%), suggesting that the islands were settled by both men and women, as seems to have been the case in Orkney and the northern and western coastline of Scotland, but areas of the British Isles further away from Scandinavia show signs of being colonised primarily by males who found local wives.Article: Genetic evidence for a family-based Scandinavian settlement of Shetland and Orkney during the Viking periods

/ref> After the islands were transferred to Scotland thousands of Scots families emigrated to Shetland in the 16th and 17th centuries. Contacts with Germany and the Netherlands through the fishing trade brought smaller numbers of immigrants from those countries.

subarctic

The subarctic zone is a region in the Northern Hemisphere immediately south of the true Arctic, north of humid continental regions and covering much of Alaska, Canada, Iceland, the north of Scandinavia, Siberia, and the Cairngorms. Generally, ...

archipelago

An archipelago ( ), sometimes called an island group or island chain, is a chain, cluster, or collection of islands, or sometimes a sea containing a small number of scattered islands.

Examples of archipelagos include: the Indonesian Archi ...

of Shetland

Shetland, also called the Shetland Islands and formerly Zetland, is a subarctic archipelago in Scotland lying between Orkney, the Faroe Islands and Norway. It is the northernmost region of the United Kingdom.

The islands lie about to the no ...

in Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to the ...

. The early history of the islands is dominated by the influence of the Viking

Vikings ; non, víkingr is the modern name given to seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded and se ...

s. From the 14th century, it was incorporated into the Kingdom of Scotland

The Kingdom of Scotland (; , ) was a sovereign state in northwest Europe traditionally said to have been founded in 843. Its territories expanded and shrank, but it came to occupy the northern third of the island of Great Britain, sharing a la ...

, and later into the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

.

Prehistory

Due to building in stone on virtually treeless islands—a practice dating to at least the early

Due to building in stone on virtually treeless islands—a practice dating to at least the early Neolithic

The Neolithic period, or New Stone Age, is an Old World archaeological period and the final division of the Stone Age. It saw the Neolithic Revolution, a wide-ranging set of developments that appear to have arisen independently in several parts ...

Period—Shetland is extremely rich in physical remains of the prehistoric era, and there are over 5,000 archaeological sites. A midden

A midden (also kitchen midden or shell heap) is an old dump for domestic waste which may consist of animal bone, human excrement, botanical material, mollusc shells, potsherds, lithics (especially debitage), and other artifacts and ecofact ...

site at West Voe on the south coast of Mainland, dated to 4320–4030 BC, has provided the first evidence of Mesolithic human activity in Shetland.

The same site provides dates for early Neolithic activity, and finds at Scourd of Brouster in

The same site provides dates for early Neolithic activity, and finds at Scourd of Brouster in Walls

Walls may refer to:

*The plural of wall, a structure

* Walls (surname), a list of notable people with the surname

Places

* Walls, Louisiana, United States

*Walls, Mississippi, United States

* Walls, Ontario, neighborhood in Perry, Ontario, C ...

have been dated to 3400 BC. "Shetland knives" are stone tools that date from this period made from felsite

Felsite is a very fine-grained volcanic rock that may or may not contain larger crystals. Felsite is a field term for a light-colored rock that typically requires petrographic examination or chemical analysis for more precise definition. Color i ...

from Northmavine

Northmavine or Northmaven ( non, Norðan Mæfeið, meaning ‘the land north of the Mavis Grind’) is a peninsula in northwest Mainland Shetland in Scotland. The peninsula has historically formed the civil parish Northmavine. The modern Northmav ...

.Schei (2006) p. 10

Brochs were built in Shetland until 150-200 AD: in the case of Old Scatness

Old Scatness is an archeological site on the Ness of Burgi, near the village of Scatness, parish of Dunrossness in the south end of Mainland, Shetland, near Sumburgh Airport and consists of medieval, Viking, Pictish, and Iron Age remains. It h ...

in Shetland (near Jarlshof

Jarlshof ( ) is the best-known prehistoric archaeological site in Shetland, Scotland. It lies in Sumburgh, Mainland, Shetland and has been described as "one of the most remarkable archaeological sites ever excavated in the British Isles". It con ...

), brochs were sometimes located close to arable land

Arable land (from the la, arabilis, "able to be ploughed") is any land capable of being ploughed and used to grow crops.''Oxford English Dictionary'', "arable, ''adj''. and ''n.''" Oxford University Press (Oxford), 2013. Alternatively, for the ...

and a source of water (some have wells or natural springs rising within their central space). Sometimes, on the other hand, they were sited in wilderness areas (e.g. Levenwick

Levenwick is a small village about south of Lerwick, on the east side of the South Mainland of Shetland, Scotland. It is part of the parish of Dunrossness and the Levenwick Health Centre provides medical support for the Dunrossness area.It con ...

and Culswick

The Broch of Culswick (also Culswick Broch) is an unexcavated coastal broch in the Shetland Islands of Scotland (). It has good views all around, including Foula and Vaila isles, and Fitful Head and Fair Isle in the south. The broch stands ...

in main Shetland). Brochs are often built beside the sea and sometimes they are on islands in lochs

''Loch'' () is the Scottish Gaelic, Scots and Irish word for a lake or sea inlet. It is cognate with the Manx lough, Cornish logh, and one of the Welsh words for lake, llwch.

In English English and Hiberno-English, the anglicised spelling ...

(e.g. Clickimin

The Broch of Clickimin (also Clickimin or Clickhimin Broch) is a large, well-preserved but restored broch in Lerwick in Shetland, Scotland (). Originally built on an island in Clickimin Loch, it was approached by a stone causeway. The broch i ...

in Shetland).

The Romans

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

* Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lette ...

were aware of (and probably circumnavigated, seeing in the distance Thule

Thule ( grc-gre, Θούλη, Thoúlē; la, Thūlē) is the most northerly location mentioned in ancient Greek literature, ancient Greek and Latin literature, Roman literature and cartography. Modern interpretations have included Orkney, Shet ...

according to Tacitus

Publius Cornelius Tacitus, known simply as Tacitus ( , ; – ), was a Roman historian and politician. Tacitus is widely regarded as one of the greatest Roman historiography, Roman historians by modern scholars.

The surviving portions of his t ...

) the Orkney & Shetland Islands, which they called "Orcades", where they discovered the brochs. A "king of the Orcades" was one of the 11 rulers said to have paid tribute to Claudius

Tiberius Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus (; 1 August 10 BC – 13 October AD 54) was the fourth Roman emperor, ruling from AD 41 to 54. A member of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, Claudius was born to Nero Claudius Drusus, Drusu ...

following his invasion of Britain in AD 43. Indeed 4th and 5th century sources include these islands in a Roman province

The Roman provinces (Latin: ''provincia'', pl. ''provinciae'') were the administrative regions of Ancient Rome outside Roman Italy that were controlled by the Romans under the Roman Republic and later the Roman Empire. Each province was rule ...

.

Archaeological evidence suggests that the Romans only traded with the inhabitants, perhaps through intermediaries, no signs of clear occupation have been found. But, according to scholars like Montesanti, "Orkney and Shetland might have been one of those areas that suggest direct administration by Imperial Roman procurators, at least for a very short span of time".

Evidence for the language spoken in Shetland immediately before Norse colonization (c. 800 AD) is limited. Katherine Forsyth

Katherine S. Forsyth is a Scottish historian who specializes in the history and culture of Celtic-speaking peoples during the 1st millennium AD, in particular the Picts. She is currently a professor iCeltic and Gaelicat the University of Glasgo ...

(2020) suggests that such evidence, including the island name ''Yell

A yell is a loud vocalization; see screaming.

Yell may also refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* Yell, Shetland, one of the North Isles of the Shetland archipelago, Scotland

* Yell Sound, Shetland, Scotland

United States

* Yell, Tennessee, an unin ...

'' and a number of names and words found on inscriptions such those at Lunnasting

Vidlin (from Old Norse: ''Vaðill'' meaning a ford) is a small village located on Mainland, Shetland, Scotland. The settlement is within the parish of Nesting.

History

It is at the head of Vidlin Voe, and is the modern heart of the old parish ...

and St Ninian's Isle, indicates the presence of a Celtic language of the Brittonic

Brittonic or Brythonic may refer to:

*Common Brittonic, or Brythonic, the Celtic language anciently spoken in Great Britain

*Brittonic languages, a branch of the Celtic languages descended from Common Brittonic

*Britons (Celtic people)

The Br ...

branch.Forsyth, Katherine - Protecting a Pict?: Further thoughts on the inscribed silver chape from St Ninian’s Isle, Shetland. Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland (2020) p. 11

Viking expansion

By the end of the 9th century the

By the end of the 9th century the Scandinavians

Scandinavia; Sámi languages: /. ( ) is a subregion in Northern Europe, with strong historical, cultural, and linguistic ties between its constituent peoples. In English usage, ''Scandinavia'' most commonly refers to Denmark, Norway, and Swede ...

shifted their attention from plundering

Looting is the act of stealing, or the taking of goods by force, typically in the midst of a military, political, or other social crisis, such as war, natural disasters (where law and civil enforcement are temporarily ineffective), or rioting. ...

to invasion

An invasion is a military offensive in which large numbers of combatants of one geopolitical entity aggressively enter territory owned by another such entity, generally with the objective of either: conquering; liberating or re-establishing con ...

, mainly due to the overpopulation of Scandinavia

Scandinavia; Sámi languages: /. ( ) is a subregion#Europe, subregion in Northern Europe, with strong historical, cultural, and linguistic ties between its constituent peoples. In English usage, ''Scandinavia'' most commonly refers to Denmark, ...

in comparison to resources and arable land

Arable land (from the la, arabilis, "able to be ploughed") is any land capable of being ploughed and used to grow crops.''Oxford English Dictionary'', "arable, ''adj''. and ''n.''" Oxford University Press (Oxford), 2013. Alternatively, for the ...

available there.

Shetland was colonised by Norsemen in the 9th century, the fate of the existing indigenous population being uncertain. The colonists gave it that name and established their laws and language. That language evolved into the West Nordic language Norn

Norn may refer to:

*Norn language, an extinct North Germanic language that was spoken in Northern Isles of Scotland

*Norns, beings from Norse mythology

*Norn Iron, the local pronunciation of Northern Ireland

*Norn iron works, an old industrial co ...

, which survived into the 19th century.

After Harald Finehair

Harald Fairhair no, Harald hårfagre Modern Icelandic: ( – ) was a Norwegian king. According to traditions current in Norway and Iceland in the eleventh and twelfth centuries, he reigned from 872 to 930 and was the first King of Nor ...

took control of all Norway, many of his opponents fled, some to Orkney

Orkney (; sco, Orkney; on, Orkneyjar; nrn, Orknøjar), also known as the Orkney Islands, is an archipelago in the Northern Isles of Scotland, situated off the north coast of the island of Great Britain. Orkney is 10 miles (16 km) north ...

and Shetland. From the Northern Isles

The Northern Isles ( sco, Northren Isles; gd, Na h-Eileanan a Tuath; non, Norðreyjar; nrn, Nordøjar) are a pair of archipelagos off the north coast of mainland Scotland, comprising Orkney and Shetland. They are part of Scotland, as are th ...

they continued to raid Scotland and Norway, prompting Harald Hårfagre to raise a large fleet which he sailed to the islands. In about 875 he and his forces took control of Shetland and Orkney. Ragnvald, Earl of Møre received Orkney and Shetland as an earldom

Earl () is a rank of the nobility in the United Kingdom. The title originates in the Old English word ''eorl'', meaning "a man of noble birth or rank". The word is cognate with the Scandinavian form ''jarl'', and meant "chieftain", particular ...

from the king as reparation for his son's being killed in battle in Scotland. Ragnvald gave the earldom to his brother Sigurd the Mighty.

Shetland was Christianised

Christianization ( or Christianisation) is to make Christian; to imbue with Christian principles; to become Christian. It can apply to the conversion of an individual, a practice, a place or a whole society. It began in the Roman Empire, conti ...

in the 10th century.

Conflict with Norway

In 1194 when kingSverre Sigurdsson

Sverre Sigurdsson ( non, Sverrir Sigurðarson) (c. 1145/1151 – 9 March 1202) was the king of Norway from 1184 to 1202.

Many consider him one of the most important rulers in Norwegian history. He assumed power as the leader of the rebel party ...

(ca 1145–1202) ruled Norway and Harald Maddadsson

Harald Maddadsson (Old Norse: ''Haraldr Maddaðarson'', Gaelic: ''Aralt mac Mataid'') (c. 1134 – 1206) was Earl of Orkney and Mormaer of Caithness from 1139 until 1206. He was the son of Matad, Mormaer of Atholl, and Margaret, daughter ...

was Earl of Orkney and Shetland, the Lendmann Hallkjell Jonsson and the Earl's brother-in-law Olav raised an army called the '' eyjarskeggjar'' on Orkney and sailed for Norway. Their pretender king was Olav's young foster son Sigurd

Sigurd ( non, Sigurðr ) or Siegfried (Middle High German: ''Sîvrit'') is a legendary hero of Germanic heroic legend, who killed a dragon and was later murdered. It is possible he was inspired by one or more figures from the Frankish Meroving ...

, son of king Magnus Erlingsson

Magnus Erlingsson ( non, Magnús Erlingsson, 1156 – 15 June 1184) was a king of Norway (being Magnus V) during the civil war era in Norway. He was the first known Scandinavian monarch to be crowned in Scandinavia. He helped to establish primoge ...

. The ''eyjarskeggjar'' were beaten in the Battle of Florvåg near Bergen

Bergen (), historically Bjørgvin, is a city and municipality in Vestland county on the west coast of Norway. , its population is roughly 285,900. Bergen is the second-largest city in Norway. The municipality covers and is on the peninsula of ...

. The body of Sigurd Magnusson was displayed for the king in Bergen in order for him to be sure of the death of his enemy, but he also demanded that Harald Maddadsson (Harald jarl) answer for his part in the uprising. In 1195 the earl sailed to Norway to reconcile with King Sverre. As a punishment the king placed the earldom of Shetland under the direct rule of the king, from which it was probably never returned.

Growing Scottish interest

Alexander III of Scotland

Alexander III (Medieval ; Modern Gaelic: ; 4 September 1241 – 19 March 1286) was King of Scots from 1249 until his death. He concluded the Treaty of Perth, by which Scotland acquired sovereignty over the Western Isles and the Isle of Man. His ...

turned twenty-one in 1262 and became of age, he declared his intention of continuing the aggressive policy his father had begun towards the western and northern isles. This had been put on hold when his father had died thirteen years earlier. Alexander sent a formal demand to the Norwegian King Håkon Håkonsson

Haakon IV Haakonsson ( – 16 December 1263; Old Norse: ''Hákon Hákonarson'' ; Norwegian: ''Håkon Håkonsson''), sometimes called Haakon the Old in contrast to his namesake son, was King of Norway from 1217 to 1263. His reign lasted for 46 y ...

.

After decades of civil war, Norway had achieved stability and grown to be a substantial nation with influence in Europe and the potential to be a powerful force in war. With this as a background, King Håkon rejected all demands from the Scots. The Norwegians regarded all the islands in the North Sea as part of the Norwegian realm. To add weight to his answer, King Håkon activated the ''leidang The institution known as ''leiðangr'' (Old Norse), ''leidang'' (Norwegian), ''leding'' (Danish), ''ledung'' (Swedish), ''expeditio'' (Latin) or sometimes lething (English), was a form of conscription ( mass levy) to organize coastal fleets for seas ...

'' and set off from Norway in a fleet which is said to have been the largest ever assembled in Norway. The fleet met up in ''Breideyarsund'' in Shetland (probably today's Bressay

Bressay ( sco, Bressa) is a populated island in the Shetland archipelago of Scotland.

Geography and geology

Bressay lies due south of Whalsay, west of the Isle of Noss, and north of Mousa. With an area of , it is the fifth-largest island in Shet ...

Sound) before the king and his men sailed for Scotland and made landfall on Arran. The aim was to conduct negotiations with the army as a backup.

Alexander III drew out the negotiations while he patiently waited for the autumn storms to set in. Finally, after tiresome diplomatic talks, King Håkon lost his patience and decided to attack. At the same time a large storm set in which destroyed several of his ships and kept others from making landfall. The Battle of Largs

The Battle of Largs (2 October 1263) was a battle between the kingdoms of Norway and Scotland, on the Firth of Clyde near Largs, Scotland. Through it, Scotland achieved the end of 500 years of Norse Viking depredations and invasions despite bei ...

in October 1263 was not decisive and both parties claimed victory, but King Håkon Håkonsson's position was hopeless. On 5 October, he returned to Orkney with a discontented army, and there he died of a fever on 17 December 1263. His death halted any further Norwegian expansion in Scotland.

King Magnus Lagabøte

Magnus Haakonsson ( non, Magnús Hákonarson, no, Magnus Håkonsson, label=Modern Norwegian; 1 (or 3) May 1238 – 9 May 1280) was King of Norway (as Magnus VI) from 1263 to 1280 (junior king from 1257). One of his greatest achievements was the m ...

broke with his father's expansion policy and started negotiations with Alexander III. In the Treaty of Perth

The Treaty of Perth, signed 2 July 1266, ended military conflict between Magnus VI of Norway and Alexander III of Scotland over possession of the Hebrides and the Isle of Man. The text of the treaty.

The Hebrides and the Isle of Man had become ...

of 1266 he surrendered his furthest Norwegian possessions including Man

A man is an adult male human. Prior to adulthood, a male human is referred to as a boy (a male child or adolescent). Like most other male mammals, a man's genome usually inherits an X chromosome from the mother and a Y chromo ...

and the Sudreyar (Hebrides

The Hebrides (; gd, Innse Gall, ; non, Suðreyjar, "southern isles") are an archipelago off the west coast of the Scottish mainland. The islands fall into two main groups, based on their proximity to the mainland: the Inner and Outer Hebrid ...

) to Scotland in return for 4,000 marks

Marks may refer to:

Business

* Mark's, a Canadian retail chain

* Marks & Spencer, a British retail chain

* Collective trade marks, trademarks owned by an organisation for the benefit of its members

* Marks & Co, the inspiration for the novel ...

sterling and an annuity of 100 marks. The Scots also recognised Norwegian sovereignty over Orkney and Shetland.

One of the main reasons behind the Norwegian desire for peace with Scotland was that trade with England was suffering from the constant state of war. In the new trade agreement between England and Norway in 1223 the English demanded Norway make peace with Scotland. In 1269, this agreement was expanded to include mutual free trade.

Pawned to Scotland

In the 14th century Norway still treated Orkney and Shetland as a Norwegian province, but Scottish influence was growing, and in 1379 the Scottish earl Henry Sinclair took control of Orkney on behalf of the Norwegian king Håkon VI Magnusson. In 1384 Norway was severely weakened by the

In the 14th century Norway still treated Orkney and Shetland as a Norwegian province, but Scottish influence was growing, and in 1379 the Scottish earl Henry Sinclair took control of Orkney on behalf of the Norwegian king Håkon VI Magnusson. In 1384 Norway was severely weakened by the Black Plague

The Black Death (also known as the Pestilence, the Great Mortality or the Plague) was a bubonic plague pandemic occurring in Western Eurasia and North Africa from 1346 to 1353. It is the most fatal pandemic recorded in human history, causi ...

and in 1397 it entered the Kalmar Union

The Kalmar Union (Danish language, Danish, Norwegian language, Norwegian, and sv, Kalmarunionen; fi, Kalmarin unioni; la, Unio Calmariensis) was a personal union in Scandinavia, agreed at Kalmar in Sweden, that from 1397 to 1523 joined under ...

. With time Norway came increasingly under Danish

Danish may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to the country of Denmark

People

* A national or citizen of Denmark, also called a "Dane," see Demographics of Denmark

* Culture of Denmark

* Danish people or Danes, people with a Danish a ...

control. King Christian I

Christian I (February 1426 – 21 May 1481) was a Scandinavian monarch under the Kalmar Union. He was king of Denmark (1448–1481), Norway (1450–1481) and Sweden (1457–1464). From 1460 to 1481, he was also duke of Schleswig (within ...

of Denmark and Norway was in financial trouble and, when his daughter Margaret

Margaret is a female first name, derived via French () and Latin () from grc, μαργαρίτης () meaning "pearl". The Greek is borrowed from Persian.

Margaret has been an English name since the 11th century, and remained popular througho ...

became engaged to James III of Scotland

James III (10 July 1451/May 1452 – 11 June 1488) was King of Scots from 1460 until his death at the Battle of Sauchieburn in 1488. He inherited the throne as a child following the death of his father, King James II, at the siege of Roxburgh Ca ...

in 1468, he needed money to pay her dowry

A dowry is a payment, such as property or money, paid by the bride's family to the groom or his family at the time of marriage. Dowry contrasts with the related concepts of bride price and dower. While bride price or bride service is a payment b ...

. Under Norse udal law

Udal law is a Norse-derived legal system, found in Shetland and Orkney in Scotland, and in Manx law in the Isle of Man. It is closely related to Odelsrett; both terms are from Proto-Germanic *''Ōþalan'', meaning "heritage; inheritance".

Hi ...

, the king had no overall ownership of the land in the realm as in the Scottish feudal system. He was king of his people, rather than king of the land. What the king did not personally own was owned absolutely by others. The King's lands represented only a small part of Shetland. Apparently without the knowledge of the Norwegian Riksråd

Riksrådet (in Norwegian and Swedish), Rigsrådet (in Danish) or (English: the Council of the Realm and the Council of the State – sometimes translated as the "Privy Council") is the name of the councils of the Scandinavian countries that rule ...

(Council of the Realm) he entered into a commercial contract on 8 September 1468 with the King of Scots in which he pawned his personal interests in Orkney for 50,000 Rhenish guilder

Guilder is the English translation of the Dutch and German ''gulden'', originally shortened from Middle High German ''guldin pfenninc'' "gold penny". This was the term that became current in the southern and western parts of the Holy Roman Empir ...

s. On 28 May the next year he also pawned his Shetland interests for 8,000 Rhenish guilders. He secured a clause in the contract which gave Christian or his successors the right to redeem the islands for a fixed sum of of gold or of silver. There was an obligation to retain the language and laws of Norway, which was not only implicit in the pawning document, but is acknowledged in later correspondence between James III and King Christian's son John (Hans). In 1470 William Sinclair, 1st Earl of Caithness

William Sinclair (1410–1480), 1st Earl of Caithness (1455–1476), last Earl (Jarl) of Orkney (1434–1470 de facto, –1472 de jure), 2nd Lord Sinclair and 11th Baron of Roslin was a Norwegian and Scottish nobleman and the buil ...

ceded his title to James III and on 20 February 1472, the Northern Isles were directly annexed to the Crown of Scotland.

James and his successors fended off all attempts by the Danes to redeem them (by formal letter or by special embassies were made in 1549, 1550, 1558, 1560, 1585, 1589, 1640, 1660 and other intermediate years) not by contesting the validity of the claim, but by simply avoiding the issue.

Hansa era

From the early 15th century on the Shetlanders sold their goods through theHanseatic League

The Hanseatic League (; gml, Hanse, , ; german: label=Modern German, Deutsche Hanse) was a medieval commercial and defensive confederation of merchant guilds and market towns in Central and Northern Europe. Growing from a few North German to ...

of German merchantmen. The Hansa would buy shiploads of salted fish, wool and butter and import salt

Salt is a mineral composed primarily of sodium chloride (NaCl), a chemical compound belonging to the larger class of salts; salt in the form of a natural crystalline mineral is known as rock salt or halite. Salt is present in vast quantitie ...

, cloth

Textile is an umbrella term that includes various fiber-based materials, including fibers, yarns, filaments, threads, different fabric types, etc. At first, the word "textiles" only referred to woven fabrics. However, weaving is not the ...

, beer

Beer is one of the oldest and the most widely consumed type of alcoholic drink in the world, and the third most popular drink overall after water and tea. It is produced by the brewing and fermentation of starches, mainly derived from ce ...

and other goods. The late 16th century and early 17th century was dominated by the influence of the despotic Robert Stewart, Earl of Orkney, who was granted the islands by his half-sister Mary Queen of Scots

Mary, Queen of Scots (8 December 1542 – 8 February 1587), also known as Mary Stuart or Mary I of Scotland, was Queen of Scotland from 14 December 1542 until her forced abdication in 1567.

The only surviving legitimate child of James V of Scot ...

, and his son Patrick Patrick may refer to:

* Patrick (given name), list of people and fictional characters with this name

* Patrick (surname), list of people with this name

People

* Saint Patrick (c. 385–c. 461), Christian saint

*Gilla Pátraic (died 1084), Patrick ...

. The latter commenced the building of Scalloway Castle

Scalloway Castle is a tower house in Scalloway, on the Shetland Mainland, the largest island in the Shetland Islands of Scotland. The tower was built in 1600 by Patrick Stewart, 2nd Earl of Orkney, during his brief period as de facto ruler of S ...

, but after his execution in 1609 the Crown annexed Orkney and Shetland again until 1643 when Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

granted them to William Douglas, 7th Earl of Morton

William Douglas, 7th Earl of Morton (1582 – 7 August 1648) was a grandson of the 6th Earl of Morton. He was Treasurer of Scotland, and a zealous Royalist.

Life

He was the son of Robert Douglas, Master of Morton, and Jean Lyon, daughter of ...

. These rights were held on and off by the Mortons until 1766, when they were sold by James Douglas, 14th Earl of Morton

James Douglas, 14th Earl of Morton, KT, PRS (1702 – 12 October 1768) was a Scottish astronomer and representative peer who was president of the Philosophical Society of Edinburgh from its foundation in 1737 until his death. He also became ...

to Sir Laurence Dundas.

British era

The trade with the North German towns lasted until the 1707 Act of Union prohibited the German merchants from trading with Shetland. Shetland then went into an economic depression as the Scottish and local traders were not as skilled in trading with salted fish. However, some local merchant-lairds took up where the German merchants had left off, and fitted out their own ships to export fish from Shetland to the Continent. For the independent farmers of Shetland this had negative consequences, as they now had to fish for these merchant-lairds.Visit.Shetland.org history page/ref> With the passing of the

Crofters' Holdings (Scotland) Act 1886

The Crofters Holdings (Scotland) Act 1886 ( gd, Achd na Croitearachd 1886) is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that created legal definitions of ''crofting parish'' and ''crofter'', granted security of land tenure to crofters and ...

the Liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

prime minister William Ewart Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone ( ; 29 December 1809 – 19 May 1898) was a British statesman and Liberal politician. In a career lasting over 60 years, he served for 12 years as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, spread over four non-conse ...

emancipated crofters from the rule of the landlords. The Act enabled those who had effectively been landowners' serfs to become owner-occupiers of their own small farms.

During the 200 years after the pawning, the islands were passed back and forth fourteen times between the Crown and courtiers as a means of extracting income. Laws were changed, weights and measures altered and the language suppressed, a process historians now call "feudalisation" as a means by which Shetland became incorporated into Scotland, particularly during the 17th century. The term is a nonsense because a feudal charter requires ownership by the Crown – ownership it has never had and has never openly claimed to have had. As late as the 20th century the courts declared that no land in Shetland was under feudal tenure.

The Crown might have thought that by prescription (the passage of time) it gave them ownership necessary to give out feudal charters, grants, or licences. It certainly behaved that way. Nevertheless, this was proved wrong by the Treaty of Breda (1667)

The Peace of Breda, or Treaty of Breda was signed in the Dutch city of Breda, on 31 July 1667. It consisted of three separate treaties between England and each of its opponents in the Second Anglo-Dutch War: the Dutch Republic, France, and Denma ...

. Its direct concern was the redistribution of colonial lands throughout the world after the second Anglo-Dutch war. It was signed by ‘the plenipotentiaries of Europe’ - delegations having full government power.

The Danish delegation tried to have a clause inserted to have the islands returned without delay. Because the overall treaty was too important to Charles II he eventually conceded that the original marriage document still stood, that his and previous monarchs’ actions in granting out the islands under feudal charters were illegal.

In 1669 Charles passed his 1669 Act for annexation of Orkney and Shetland to the Crown, restoring the situation much as it had been in 1469. He abolished the office of Sheriff and "erected Shetland into a Stewartry", having "a direct dependence upon His Majesty and his officers" (what today we would today call a Crown Dependency). Charles II also provided that, in the event of a "general dissolution of his majesty’s properties" by which he clearly meant the Act of Union, Shetland was not to be included. Shetland could not be incorporated into the realm of Scotland or the proposed new union with England. The terms of the marriage document also meant that any Acts of Parliament before or after the pawning could have had no relevance to Shetland.

With the consent of Parliament, Charles was taking the exclusive rights to the islands back to the Crown for all time coming. Furthermore, he was specifically excluding Shetland from the coming Act of Union, even going so far as to say that the Act of Union itself would be null and void if Shetland were to be included.

Several attempts were made during the 17th and 18th centuries to redeem the islands, without success. Following a legal dispute with William, Earl of Morton, who held the estates of Orkney and Shetland, Charles II ratified the pawning document by a Scottish

Several attempts were made during the 17th and 18th centuries to redeem the islands, without success. Following a legal dispute with William, Earl of Morton, who held the estates of Orkney and Shetland, Charles II ratified the pawning document by a Scottish Act of Parliament

Acts of Parliament, sometimes referred to as primary legislation, are texts of law passed by the Legislature, legislative body of a jurisdiction (often a parliament or council). In most countries with a parliamentary system of government, acts of ...

on 27 December 1669 which officially made the islands a Crown dependency and exempt from any "dissolution of His Majesty’s lands". In 1742 a further Act of Parliament returned the estates to a later Earl of Morton, although the original Act of Parliament specifically ruled that any future act regarding the islands status would be "considered null, void and of no effect".

Nonetheless, Shetland's connection with Norway has proven to be enduring. When the union between Norway and Sweden ended in 1906 the Shetland authorities sent a letter to King Haakon VII

Haakon VII (; born Prince Carl of Denmark; 3 August 187221 September 1957) was the King of Norway from November 1905 until his death in September 1957.

Originally a Danish prince, he was born in Copenhagen as the son of the future Frederick VI ...

in which they stated: "Today no 'foreign' flag is more familiar or more welcome in our voes and havens than that of Norway, and Shetlanders continue to look upon Norway as their mother-land, and recall with pride and affection the time when their forefathers were under the rule of the Kings of Norway."Schei (2006) p. 13

Napoleonic wars

Some 3000 Shetlanders served in theRoyal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

during the Napoleonic wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

from 1800 to 1815.

World War II

DuringWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

a Norwegian naval unit nicknamed the "Shetland Bus

The Shetland Bus (Norwegian Bokmål: ''Shetlandsbussene'', def. pl.) was the nickname of a clandestine special operations group that made a permanent link between Mainland Shetland in Scotland and German-occupied Norway from 1941 until the su ...

" was established by the Special Operations Executive

The Special Operations Executive (SOE) was a secret British World War II organisation. It was officially formed on 22 July 1940 under Minister of Economic Warfare Hugh Dalton, from the amalgamation of three existing secret organisations. Its pu ...

Norwegian Section in the autumn of 1940 with a base first at Lunna

Lunna (born June 30, 1960; born María Socorro García de la NocedaGarcia de la Noceda is her paternal surname) is a Puerto Rican singer of popular music and jazz who was the director of the television show ''Objetivo Fama'', the Latin version ...

and later in Scalloway

Scalloway ( non, Skálavágr, "bay with the large house(s)") is the largest settlement on the west coast of the Mainland, the largest island of the Shetland Islands, Scotland. The village had a population of roughly 900, at the 2011 census. No ...

in order to conduct operations on the coast of Norway. About 30 fishing vessels used by Norwegian refugees were gathered in Shetland. Many of these vessels were rented, and Norwegian fishermen were recruited as volunteers to operate them.

The Shetland Bus sailed in covert operations between Norway and Shetland, carrying men from Company Linge

Norwegian Independent Company 1 (NOR.I.C.1, pronounced ''Norisén'' (approx. "noor-ee-sehn") in Norwegian) was a British Special Operations Executive (SOE) group formed in March 1941 originally for the purpose of performing commando raids during ...

, intelligence agents, refugees, instructors for the resistance, and military supplies. Many people on the run from the Germans, and much important information on German activity in Norway, were brought back to the Allies this way. Some mines were laid and direct action against German ships was also taken. At the start the unit was under a British command, but later Norwegians joined in the command.

The fishing vessels made 80 trips across the sea. German attacks and bad weather caused the loss of 10 boats, 44 crewmen, and 60 refugees. Because of the high losses it was decided to procure faster vessels. The Americans gave the unit the use of three submarine chasers ( HNoMS ''Hessa'', HNoMS ''Hitra'' and HNoMS ''Vigra''). None of the trips with these vessels incurred loss of life or equipment.

The Shetland Bus made over 200 trips across the sea and the most famous of the men, Leif Andreas Larsen (Shetlands-Larsen) made 52 of them.

Cultural influences

Historical, archaeological, place-name and linguistic evidence indicates Norse cultural dominance of Shetland during the Viking period. A few place names might have Pictish origin, but this is disputed. Several genetic studies have been conducted investigating the genetic makeup of the islands' population today in order to establish its origin. Shetlanders are less than half Scandinavian in origin. They have almost identical proportions of Scandinavian matrilineal and patrilineal ancestry (ca 44%), suggesting that the islands were settled by both men and women, as seems to have been the case in Orkney and the northern and western coastline of Scotland, but areas of the British Isles further away from Scandinavia show signs of being colonised primarily by males who found local wives.

Historical, archaeological, place-name and linguistic evidence indicates Norse cultural dominance of Shetland during the Viking period. A few place names might have Pictish origin, but this is disputed. Several genetic studies have been conducted investigating the genetic makeup of the islands' population today in order to establish its origin. Shetlanders are less than half Scandinavian in origin. They have almost identical proportions of Scandinavian matrilineal and patrilineal ancestry (ca 44%), suggesting that the islands were settled by both men and women, as seems to have been the case in Orkney and the northern and western coastline of Scotland, but areas of the British Isles further away from Scandinavia show signs of being colonised primarily by males who found local wives./ref> After the islands were transferred to Scotland thousands of Scots families emigrated to Shetland in the 16th and 17th centuries. Contacts with Germany and the Netherlands through the fishing trade brought smaller numbers of immigrants from those countries.

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

and the oil industry have also brought about population growth through immigration.

Population development

The population development in Shetland has through history been affected by deaths at sea and epidemics.Smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

afflicted the islands in the 17th and 18th centuries, but as inoculations pioneered by those such as Johnnie Notions

John Williamson (), more commonly known by the nickname Johnnie Notions (, ) was a self-taught physician from Shetland, Scotland, who independently developed and administered an inoculation for smallpox to thousands of patients in Shetland du ...

came into widespread use the population was able to grow more quickly. By 1861 the population increased to 40,000. The population increase led to a lack of food, and many young men went away to serve in the British merchant fleet. By 100 years later the islands' population had been more than halved, mainly due to many Shetland men being lost at sea during the two world wars, and the waves of emigration in the 1920s and 1930s. Now more people of Shetland background live in Canada, Australia and New Zealand than in Shetland.

Timeline

References

;Notes ;FootnotesFurther reading

* Coull, James R. "A comparison of demographic trends in the Faroe and Shetland Islands." ''Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers'' (1967): 159–166. * Miller, James. ''The North Atlantic Front: Orkney, Shetland, Faroe and Iceland at War'' (2004) * Nicolson, James R. (1972) ''Shetland''. Newton Abbott. David & Charles. * Schei, Liv Kjørsvik (2006) ''The Shetland Isles''. Grantown-on-Spey. Colin Baxter Photography. * Withrington, Donald J. Shetland and the outside world, 1469–1969. Oxford Univ Pr, 1983. {{History of the British Isles, bar=yes