[a terrible beast in nearby ]Tarascon

Tarascon (; ), sometimes referred to as Tarascon-sur-Rhône, is a commune situated at the extreme west of the Bouches-du-Rhône department of France in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region. Inhabitants are referred to as Tarasconnais or Taras ...

. Pilgrims visited their tombs at the abbey of Vézelay

Vézelay () is a commune in the department of Yonne in the north-central French region of Bourgogne-Franche-Comté. It is a defensible hill town famous for Vézelay Abbey. The town and its 11th-century Romanesque Basilica of St Magdalene ar ...

in Burgundy

Burgundy (; french: link=no, Bourgogne ) is a historical territory and former administrative region and province of east-central France. The province was once home to the Dukes of Burgundy from the early 11th until the late 15th century. The ...

. In the Abbey of the Trinity at Vendôme

Vendôme (, ) is a subprefecture of the department of Loir-et-Cher, France. It is also the department's third-biggest commune with 15,856 inhabitants (2019).

It is one of the main towns along the river Loir. The river divides itself at the ...

, a phylactery was said to contain a tear shed by Jesus at the tomb of Lazarus. The cathedral of Autun

Autun () is a subprefecture of the Saône-et-Loire department in the Bourgogne-Franche-Comté region of central-eastern France. It was founded during the Principate era of the early Roman Empire by Emperor Augustus as Augustodunum to give a Ro ...

, not far away, is dedicated to Lazarus as ''Saint Lazaire''.

History

The first written records of Christians in France date from the 2nd century when Irenaeus

Irenaeus (; grc-gre, Εἰρηναῖος ''Eirēnaios''; c. 130 – c. 202 AD) was a Greek bishop noted for his role in guiding and expanding Christian communities in the southern regions of present-day France and, more widely, for the de ...

detailed the deaths of ninety-year-old bishop Pothinus of Lugdunum

Lugdunum (also spelled Lugudunum, ; modern Lyon, France) was an important Roman city in Gaul, established on the current site of Lyon. The Roman city was founded in 43 BC by Lucius Munatius Plancus, but continued an existing Gallic settle ...

(Lyon

Lyon,, ; Occitan: ''Lion'', hist. ''Lionés'' also spelled in English as Lyons, is the third-largest city and second-largest metropolitan area of France. It is located at the confluence of the rivers Rhône and Saône, to the northwest of ...

) and other martyrs of the 177 persecution in Lyon

The persecution in Lyon in AD 177 was a legendary persecution of Christians in Lugdunum, Roman Gaul (present-day Lyon, France), during the reign of Marcus Aurelius (161–180). As there is no coeval account of this persecution the earliest so ...

.

In 496 Remigius baptized Clovis I

Clovis ( la, Chlodovechus; reconstructed Frankish: ; – 27 November 511) was the first king of the Franks to unite all of the Frankish tribes under one ruler, changing the form of leadership from a group of petty kings to rule by a single ki ...

, who was converted from paganism to Catholicism. Clovis I, considered the founder of France, made himself the ally and protector of the papacy and of his predominantly Catholic subjects.

Foundation of Christendom in France

On Christmas Day 800, Pope Leo III

Pope Leo III (died 12 June 816) was bishop of Rome and ruler of the Papal States from 26 December 795 to his death. Protected by Charlemagne from the supporters of his predecessor, Adrian I, Leo subsequently strengthened Charlemagne's position ...

crowned Charlemagne

Charlemagne ( , ) or Charles the Great ( la, Carolus Magnus; german: Karl der Große; 2 April 747 – 28 January 814), a member of the Carolingian dynasty, was King of the Franks from 768, King of the Lombards from 774, and the first E ...

Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a political entity in Western, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its dissolution in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars.

From the accession of Otto I in 962 unt ...

, forming the political and religious foundations of Christendom

Christendom historically refers to the Christian states, Christian-majority countries and the countries in which Christianity dominates, prevails,SeMerriam-Webster.com : dictionary, "Christendom"/ref> or is culturally or historically intertwin ...

and establishing in earnest the French government's longstanding historical association with the Roman Catholic Church.

The Treaty of Verdun

The Treaty of Verdun (), agreed in , divided the Frankish Empire into three kingdoms among the surviving sons of the emperor Louis I, the son and successor of Charlemagne. The treaty was concluded following almost three years of civil war and ...

(843) provided for the partition of Charlemagne's empire into 3 independent kingdoms, and one of these was France. A great churchman, Hincmar, Archbishop of Rheims (806-82), was the deviser of the new arrangement. He strongly supported the kingship of Charles the Bald, under whose scepter he would have placed Lorraine also. To Hincmar, the dream of a united Christendom did not appear under the guise of an empire, however ideal, but under the concrete form of a number of unit States, each being a member of one mighty body, the great Republic of Christendom. He would replace the empire by a Europe of which France was one member. Under Charles the Fat (880-88) it looked for a moment as though Charlemagne's empire was about to come to life again; but the illusion was temporary, and in its stead were quickly formed seven kingdoms: France, Navarre, Provence, Burgundy beyond the Jura, Lorraine, Germany, and Italy.

Feudalism was the seething-pot, and the imperial edifice was crumbling to dust. Towards the close of the 10th century, in the Frankish kingdom alone there were twenty-nine provinces or fragments of provinces, under the sway of dukes, counts, or viscounts, constituted veritable sovereignties, and at the end of the 11th century there were as many as fifty-five of these minor states, of greater or lesser importance. As early as the 10th century one of the feudal families had begun to take the lead, that of the Dukes of Francia, descendants of Robert the Strong, and lords of all the country between the Seine and the Loire. From 887 to 987 they successfully defended French soil against the invading Northmen: the Eudes, or Odo, Duke of Francia (887-98), Robert his brother (922-23), and Raoul or Rudolph, Robert's son-in-law (923-36), occupied the throne for a brief interval. The weakness of the later Carolingian kings was evident to all, and in 987, on the death of Louis V, Adalberon, archbishop of Rheims, at a meeting of the chief men held at Senlis, contrasted the incapacity of the Carolingian Charles of Lorraine, the heir to the throne, with the merits of Hugh, Duke of Francia. Gerbert, who afterwards became

Feudalism was the seething-pot, and the imperial edifice was crumbling to dust. Towards the close of the 10th century, in the Frankish kingdom alone there were twenty-nine provinces or fragments of provinces, under the sway of dukes, counts, or viscounts, constituted veritable sovereignties, and at the end of the 11th century there were as many as fifty-five of these minor states, of greater or lesser importance. As early as the 10th century one of the feudal families had begun to take the lead, that of the Dukes of Francia, descendants of Robert the Strong, and lords of all the country between the Seine and the Loire. From 887 to 987 they successfully defended French soil against the invading Northmen: the Eudes, or Odo, Duke of Francia (887-98), Robert his brother (922-23), and Raoul or Rudolph, Robert's son-in-law (923-36), occupied the throne for a brief interval. The weakness of the later Carolingian kings was evident to all, and in 987, on the death of Louis V, Adalberon, archbishop of Rheims, at a meeting of the chief men held at Senlis, contrasted the incapacity of the Carolingian Charles of Lorraine, the heir to the throne, with the merits of Hugh, Duke of Francia. Gerbert, who afterwards became Pope Sylvester II

Pope Sylvester II ( – 12 May 1003), originally known as Gerbert of Aurillac, was a French-born scholar and teacher who served as the bishop of Rome and ruled the Papal States from 999 to his death. He endorsed and promoted study of Arab and Gre ...

, adviser and secretary to Adalberon, and Arnulf, bishop of Orléans, also spoke in support of Hugh, with the result that he was proclaimed king.

Thus the Capetian dynasty had its rise in the person of Hugh Capet

Hugh Capet (; french: Hugues Capet ; c. 939 – 14 October 996) was the King of the Franks from 987 to 996. He is the founder and first king from the House of Capet. The son of the powerful duke Hugh the Great and his wife Hedwige of Saxony, ...

. It was the work of the Church, brought to pass by the influence of the See of Reims, renowned throughout France since the episcopate of Hincmar, renowned since the days of Clovis for the privilege of anointing the Frankish kings conferred on its titular, and renowned so opportunely at this time for the learning of its episcopal school presided over by Gerbert himself.

The Church, which had set up the new dynasty, exercised a very salutary influence over French social life. It has been recently proven by the literary efforts of M. Bédier that the origin and growth of the ''"Chansons de geste"'', i.e., of early epic literature, are closely bound up with the famous pilgrim shrines, whither the piety of the people resorted. And military courage and physical heroism were schooled and blessed by the Church, which in the early part of the 11th century transformed chivalry

Chivalry, or the chivalric code, is an informal and varying code of conduct developed in Europe between 1170 and 1220. It was associated with the medieval Christian institution of knighthood; knights' and gentlemen's behaviours were governed b ...

from a lay institution of German origin into a religious one by placing among its liturgical rites the ceremony of knighthood, in which the candidate promised to defend truth, justice, and the oppressed. Founded in 910, the Congregation of Cluny

Cluny () is a commune in the eastern French department of Saône-et-Loire, in the region of Bourgogne-Franche-Comté. It is northwest of Mâcon.

The town grew up around the Benedictine Abbey of Cluny, founded by Duke William I of Aquitaine in ...

, which made rapid progress in the 11th century, prepared France to play an important part in the reformation of the Church undertaken in the second half of the 11th century by a monk of Cluny, Gregory VII, and gave the Church two other popes after him, Urban II

Pope Urban II ( la, Urbanus II; – 29 July 1099), otherwise known as Odo of Châtillon or Otho de Lagery, was the head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 12 March 1088 to his death. He is best known for convening th ...

and Pascal II. It was a Frenchman, Urban II, who at the Council of Claremont (1095) initiated the Crusades

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and sometimes directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The best known of these Crusades are those to the Holy Land in the period between 1095 and 1291 that were ...

which spread widely throughout Christendom.

Time of the Crusades

"The reign of Louis VI (1108-37) is of note in the history of the Church, and in that of France; in the one because the solemn adhesion of Louis VI to

"The reign of Louis VI (1108-37) is of note in the history of the Church, and in that of France; in the one because the solemn adhesion of Louis VI to Innocent II

Pope Innocent II ( la, Innocentius II; died 24 September 1143), born Gregorio Papareschi, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 14 February 1130 to his death in 1143. His election as pope was controversial and the fi ...

assured the unity of the Church, which at the time was seriously menaced by the Antipope Antecletus; in the other because for the first time Capetian kings took a stand as champions of law and order against the feudal system and as the protectors of public rights.

A churchman, Suger, abbot of St-Denis, a friend of Louis VI and minister of Louis VII

Louis VII (1120 – 18 September 1180), called the Younger, or the Young (french: link=no, le Jeune), was King of the Franks from 1137 to 1180. He was the son and successor of King Louis VI (hence the epithet "the Young") and married Duchess ...

(1137-80), developed and realized this ideal of kingly duty. Louis VI, seconded by Suger and counting on the support of the towns – the "communes" they were called when they had obliged the feudal lords to grant them charters of freedom – fulfilled to the letter the rôle of prince as it was conceived by the theology of the Middle Ages. "Kings have long arms," wrote Suger, "and it is their duty to repress with all their might, and by right of their office, the daring of those who rend the State by endless war, who rejoice in pillage, and who destroy homesteads and churches." Another French Churchman, St. Bernard, won Louis VII for the Crusades; and it was not his fault that Palestine, where the first crusade had set up a Latin kingdom, did not remain a French colony in the service of the Church. The divorce of Louis VII and Eleanor of Aquitaine

Eleanor ( – 1 April 1204; french: Aliénor d'Aquitaine, ) was Queen of France from 1137 to 1152 as the wife of King Louis VII, List of English royal consorts, Queen of England from 1154 to 1189 as the wife of Henry II of England, King Henry I ...

(1152) marred the ascendancy of French influence by paving the way for the growth of Anglo-Norman pretensions on the soil of France from the Channel to the Pyrenees. Soon, however, by virtue of feudal laws the French king, Philip Augustus

Philip II (21 August 1165 – 14 July 1223), byname Philip Augustus (french: Philippe Auguste), was King of France from 1180 to 1223. His predecessors had been known as kings of the Franks, but from 1190 onward, Philip became the first French m ...

(1180–1223), proclaimed himself suzerain over Richard Coeur de Lion and John Lackland, and the victory of Bouvines which he gained over the Emperor Otto IV, backed by a coalition of feudal nobles (1214), was the first ever in French history which called forth a movement of national solidarity around a French king. The war against the Albigensians

Catharism (; from the grc, καθαροί, katharoi, "the pure ones") was a Christian dualist or Gnostic movement between the 12th and 14th centuries which thrived in Southern Europe, particularly in northern Italy and southern France. Foll ...

under Louis VIII (1223–26) brought in its train the establishment of the influence and authority of the French monarchy in the south of France.

St. Louis IX

Louis IX (25 April 1214 – 25 August 1270), commonly known as Saint Louis or Louis the Saint, was King of France from 1226 to 1270, and the most illustrious of the House of Capet, Direct Capetians. He was Coronation of the French monarch, c ...

(1226–1270), "''ruisselant de piété, et enflammé de charité''", as a contemporary describes him, made kings so beloved that from that time dates the royal cult, so to speak, which was one of the moral forces in olden France, and which existed in no other country of Europe to the same degree. Piety had been for the kings of France, set on their thrones by the Church of God, as it were a duty belonging to their charge or office; but in the piety of St. Louis there was a note all his own, the note of sanctity. With him ended the Crusades, but not their spirit. During the 13th and 14th centuries, project after project attempting to set on foot a crusade was made, showing that the spirit of a militant apostolate continued to ferment in the soul of France. The project of Charles Valois (1308–09), the French expedition under Peter I of Cyprus against Alexandria and the Armenian coasts (1365–67), sung of by the French trouvère

''Trouvère'' (, ), sometimes spelled ''trouveur'' (, ), is the Northern French ('' langue d'oïl'') form of the '' langue d'oc'' (Occitan) word ''trobador'', the precursor of the modern French word ''troubadour''. ''Trouvère'' refers to poet ...

, Guillaume Machault, the crusade of John of Nevers, which ended in the bloody battle of Nicopolis (1396) – in all these enterprises, the spirit of St. Louis lived, just as in the heart of the Christians of the East, whom France was thus trying to protect, there has survived a lasting gratitude toward the nation of St. Louis. In the days of St. Louis the influence of the French epic literature in Europe was supreme. Brunetto Latini, as early as the middle of the 13th century, wrote that, "of all speech 'parlures''that of the French was the most charming, and the most in favour with everyone." French held sway in England until the middle of the 14th century; it was fluently spoken at the Court of Constantinople at the time of the Fourth Crusade; and in Greece in the dukedoms, principalities, and baronies founded there by the House of Burgundy and Champagne. And it was in French that Rusticiano of Pisa, about 1300, wrote the record of Marco Polo

Marco Polo (, , ; 8 January 1324) was a Venetian merchant, explorer and writer who travelled through Asia along the Silk Road between 1271 and 1295. His travels are recorded in '' The Travels of Marco Polo'' (also known as ''Book of the Marv ...

's travels. The University of Paris

, image_name = Coat of arms of the University of Paris.svg

, image_size = 150px

, caption = Coat of Arms

, latin_name = Universitas magistrorum et scholarium Parisiensis

, motto = ''Hic et ubique terrarum'' (Latin)

, mottoeng = Here and a ...

was saved from a spirit of exclusiveness by the happy intervention of Alexander IV, who obliged it to open its chairs to the mendicant friars. Among its professors were Duns Scotus; the Italians, St. Thomas and St. Bonaventure; Albert the Great, a German; Alexander of Hales, an Englishman. Among its pupils it counted Roger Bacon

Roger Bacon (; la, Rogerus or ', also '' Rogerus''; ), also known by the scholastic accolade ''Doctor Mirabilis'', was a medieval English philosopher and Franciscan friar who placed considerable emphasis on the study of nature through emp ...

, Dante, Raimundus Lullus, Popes Gregory IX

Pope Gregory IX ( la, Gregorius IX; born Ugolino di Conti; c. 1145 or before 1170 – 22 August 1241) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 19 March 1227 until his death in 1241. He is known for issuing the '' Decre ...

, Urban IV, Clement IV, and Boniface VIII

Pope Boniface VIII ( la, Bonifatius PP. VIII; born Benedetto Caetani, c. 1230 – 11 October 1303) was the head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 24 December 1294 to his death in 1303. The Caetani family was of baronial ...

.

Advent of Gothic art and the Hundred Years' War

France was the birthplace of Gothic art

Gothic art was a style of medieval art that developed in Northern France out of Romanesque art in the 12th century AD, led by the concurrent development of Gothic architecture. It spread to all of Western Europe, and much of Northern, Southern and ...

, which was carried by French architects into Germany. The method employed in the building of many Gothic cathedrals

A cathedral is a church that contains the ''cathedra'' () of a bishop, thus serving as the central church of a diocese, conference, or episcopate. Churches with the function of "cathedral" are usually specific to those Christian denominations ...

– i.e., by the actual assistance of the faithful – bears witness to the fact that at this period the lives of the French people were deeply penetrated with faith. An architectural wonder such as the cathedral of Chartres

Chartres Cathedral, also known as the Cathedral of Our Lady of Chartres (french: Cathédrale Notre-Dame de Chartres), is a Roman Catholic church in Chartres, France, about southwest of Paris, and is the seat of the Bishop of Chartres. Mostly co ...

was in reality the work of popular art born of the faith of the people who worshipped there.

"Divine right" and the weakening of the influence of the papacy in Christendom

"Under Philip IV, the Fair (1285–1314), the royal house of France became very powerful. By means of alliances he extended his prestige as far as the Orient. His brother Charles of Valois married Catherine de Courtney, an heiress of the Latin Empire of Constantinople. The Kings of England and Minorca were his vassals, the King of Scotland his ally, the Kings of Naples and Hungary connections by marriage. He aimed at a sort of supremacy over the body politic of Europe. Pierre Dubois, his jurisconsult, dreamed that the pope would hand over all his domains to Philip and receive in exchange an annual income, while Philip would thus have the spiritual head of Christendom under his influence. Philip IV laboured to increase the royal prerogative and thereby the national unity of France. By sending magistrates into feudal territories and by defining certain cases (''cas royaux'') as reserved to the king's competency, he dealt a heavy blow to the feudalism of the Middle Ages. But on the other hand, under his rule many anti-Christian maxims began to creep into law and politics.

"Under Philip IV, the Fair (1285–1314), the royal house of France became very powerful. By means of alliances he extended his prestige as far as the Orient. His brother Charles of Valois married Catherine de Courtney, an heiress of the Latin Empire of Constantinople. The Kings of England and Minorca were his vassals, the King of Scotland his ally, the Kings of Naples and Hungary connections by marriage. He aimed at a sort of supremacy over the body politic of Europe. Pierre Dubois, his jurisconsult, dreamed that the pope would hand over all his domains to Philip and receive in exchange an annual income, while Philip would thus have the spiritual head of Christendom under his influence. Philip IV laboured to increase the royal prerogative and thereby the national unity of France. By sending magistrates into feudal territories and by defining certain cases (''cas royaux'') as reserved to the king's competency, he dealt a heavy blow to the feudalism of the Middle Ages. But on the other hand, under his rule many anti-Christian maxims began to creep into law and politics. Roman law

Roman law is the legal system of ancient Rome, including the legal developments spanning over a thousand years of jurisprudence, from the Twelve Tables (c. 449 BC), to the '' Corpus Juris Civilis'' (AD 529) ordered by Eastern Roman emperor J ...

was slowly re-introduced into social organization, and gradually the idea of a united Christendom disappeared from the national policy. Philip the Fair, pretending to rule by Divine right, gave it to be understood that he rendered an account of his kingship to no one under heaven. He denied the pope's right to represent, as the papacy had always done in the past, the claims of morality and justice where kings were concerned. Hence arose in 1294-1303 his struggle with Pope Boniface VIII

Pope Boniface VIII ( la, Bonifatius PP. VIII; born Benedetto Caetani, c. 1230 – 11 October 1303) was the head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 24 December 1294 to his death in 1303. The Caetani family was of baronial ...

, but in that struggle he was cunning enough to secure the support of the States-General, which represented public opinion in France. In later times, after centuries of monarchical government, this same public opinion rose against the abuse of power committed by its kings in the name of their pretended divine right, and thus made an implicit ''amende'' honorable to what the Church had taught concerning the origin, the limits, and the responsibility of all power, which had been forgotten or misinterpreted by the lawyers of Philip IV when they set up their independent State as the absolute source of power. The election of Pope Clement V

Pope Clement V ( la, Clemens Quintus; c. 1264 – 20 April 1314), born Raymond Bertrand de Got (also occasionally spelled ''de Guoth'' and ''de Goth''), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 5 June 1305 to his de ...

(1305) under Philip's influence, the removal of the papacy to Avignon

Avignon (, ; ; oc, Avinhon, label= Provençal or , ; la, Avenio) is the prefecture of the Vaucluse department in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region of Southeastern France. Located on the left bank of the river Rhône, the commune had ...

, the nomination of seven French popes in succession, weakened the influence of the papacy in Christendom, though it has recently come to light that the Avignon popes did not always allow the independence of the Holy See to waver or disappear in the game of politics. Philip IV and his successors may have had the illusion that they were taking the place of the German emperors in European affairs. The papacy was imprisoned on their territory; the German empire was passing through a crisis, was, in fact, decaying, and the kings of France might well imagine themselves temporal vicars of God, side by side with, or even in opposition to, the spiritual vicar who lived at Avignon."

Hundred Years' War, Joan of Arc and the ''Rex Christianissimus''

But at this juncture the Hundred Years' War broke out, and the French kingdom, which aspired to be the arbiter of Christendom, was menaced in its very existence by England. English kings aimed at the French crown, and the two nations fought for the possession of Guienne. Twice during the war was the independence of France imperilled. Defeated on the Ecluse (1340), at Crécy (1346), at

But at this juncture the Hundred Years' War broke out, and the French kingdom, which aspired to be the arbiter of Christendom, was menaced in its very existence by England. English kings aimed at the French crown, and the two nations fought for the possession of Guienne. Twice during the war was the independence of France imperilled. Defeated on the Ecluse (1340), at Crécy (1346), at Poitiers

Poitiers (, , , ; Poitevin: ''Poetàe'') is a city on the River Clain in west-central France. It is a commune and the capital of the Vienne department and the historical centre of Poitou. In 2017 it had a population of 88,291. Its agglome ...

(1356), France was saved by Charles V Charles V may refer to:

* Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor (1500–1558)

* Charles V of Naples (1661–1700), better known as Charles II of Spain

* Charles V of France (1338–1380), called the Wise

* Charles V, Duke of Lorraine (1643–1690)

* Infa ...

(1364-80) and by Duguesclin, only to suffer French defeat under Charles VI at Agincourt (1415) and to be ceded by the Treaty of Troyes to Henry V, King of England. At this darkest hour of the monarchy, the nation itself was stirred. The revolutionary attempt by Etienne Marcel (1358) and the revolt which gave rise to the Ordonnace Cabochienne (1418) were the earliest signs of popular impatience at the absolutism of the French kings; but internal dissensions hindered an effective patriotic defence of the country. When Charles VII came to the throne, France had almost ceased to be French. The king and court lived beyond the Loire, and Paris was the seat of an English government. Saint Joan of Arc

Joan of Arc (french: link=yes, Jeanne d'Arc, translit= �an daʁk} ; 1412 – 30 May 1431) is a patron saint of France, honored as a defender of the French nation for her role in the siege of Orléans and her insistence on the coronat ...

was the saviour of French nationality as well as French royalty, and at the end of Charles' reign (1422-61) Calais was the only spot in France in the hands of the English.

The ideal of a united Christendom continued to haunt the soul of France in spite of the predominating influence gradually assumed in French politics by purely national aspirations. From the reign of Charles VI, or even the last years of Charles V, dates the custom of giving to French kings the exclusive title of ''Rex Christianissimus''. Pepin the Short and Charlemagne had been proclaimed "Most Christian" by the popes of their day: Alexander III had conferred the same title on Louis VII; but from Charles VI onwards the title comes into constant use as the special prerogative of the kings of France. Philippe de Mézières, a contemporary of Charles VI, wrote: "Because of the vigour with which Charlemagne, St. Louis, and other brave French kings, more than the other kings of Christendom, have upheld the Catholic Faith, the kings of France are known among the kings of Christendom as 'Most Christian'."

In later times, the Emperor Frederick III, addressing Charles VII, wrote: "Your ancestors have won for your name the title Most Christian, as a heritage not to be separated from it." From the pontificate of Paul II (1464), the popes, in addressing bulls to the kings of France, always use the style and title ''Rex Christianissimus''. Furthermore, European public opinion always looked upon St. Joan of Arc, who saved the French monarchy, as the heroine of Christendom, and believed that the Maid of Orléans meant to lead the king of France on another crusade when she had secured him in the peaceful possession of his own country. France's national heroine was thus heralded by the fancy of her contemporaries, by Christine de Pizan

Christine de Pizan or Pisan (), born Cristina da Pizzano (September 1364 – c. 1430), was an Italian poet and court writer for King Charles VI of France and several French dukes.

Christine de Pizan served as a court writer in medieval France ...

, and by that Venetian merchant whose letters have been preserved for us in the Morosini Chronicle, as a heroine whose aims were as wide as Christianity itself.

Rise of "gallicanism"

The 15th century, during which France was growing in national spirit, and while men's minds were still conscious of the claims of Christendom on their country, was also the century during which, on the morrow of the Great Schism and of the Councils of Basle

, french: link=no, Bâlois(e), it, Basilese

, neighboring_municipalities= Allschwil (BL), Hégenheim (FR-68), Binningen (BL), Birsfelden (BL), Bottmingen (BL), Huningue (FR-68), Münchenstein (BL), Muttenz (BL), Reinach (BL), Riehen (BS), ...

and of Constance, there began a movement among the powerful feudal bishops against pope and king, and which aimed at the emancipation of the Gallican Church. The propositions upheld by Gerson, and forced by him, as representing the University of Paris

, image_name = Coat of arms of the University of Paris.svg

, image_size = 150px

, caption = Coat of Arms

, latin_name = Universitas magistrorum et scholarium Parisiensis

, motto = ''Hic et ubique terrarum'' (Latin)

, mottoeng = Here and a ...

, on the Council of Constance, would have set up in the Church an aristocratic regime analogous to what the feudal lords, profiting by the weakness of Charles VI, had dreamed of establishing in the State. A royal proclamation in 1418, issued after the election of Martin V

Pope Martin V ( la, Martinus V; it, Martino V; January/February 1369 – 20 February 1431), born Otto (or Oddone) Colonna, was the head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 11 November 1417 to his death in February 1431. Hi ...

, maintained in opposition to the pope "all the privileges and franchises of the kingdom", put an end to the custom of annates

Annates ( or ; la, annatae, from ', "year") were a payment from the recipient of an ecclesiastical benefice to the ordaining authorities. Eventually, they consisted of half or the whole of the first year's profits of a benefice; after the appropr ...

, limited the rights of the Roman court in collecting benefices, and forbade the sending to Rome of articles of gold or silver. This proposition was assented to by the young King Charles VII in 1423, but at the same time he sent Pope Martin V an embassy asking to be absolved from the oath he had taken to uphold the principles of the Gallican Church and seeking to arrange a concordat

A concordat is a convention between the Holy See and a sovereign state that defines the relationship between the Catholic Church and the state in matters that concern both,René Metz, ''What is Canon Law?'' (New York: Hawthorn Books, 1960 st Edi ...

which would give the French king a right of patronage over 500 benefices in his kingdom. This was the beginning of the practice adopted by French kings of arranging the government of the Church directly with the popes over the heads of the bishops. Charles VII, whose struggle with England had left his authority still very precarious, was constrained, in 1438, during the Council of Basle, in order to appease the powerful prelates of the Assembly of Bourges, to promulgate the Pragmatic Sanction, thereby asserting in France those maxims of the Council of Basle which Pope Eugene had condemned. But straightway he bethought him of a concordat, and overtures in this sense were made to Eugene IV

Pope Eugene IV ( la, Eugenius IV; it, Eugenio IV; 1383 – 23 February 1447), born Gabriele Condulmer, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 3 March 1431 to his death in February 1447. Condulmer was a Venetian, and ...

. Eugene replied that he well knew that the Pragmatic Sanction – "that odious act" – was not the king's own free doing and a concordat was discussed between them. Louis XI (1461–83), whose domestic policy aimed at ending or weakening the new feudalism which had grown up during two centuries through the custom of presenting appanage

An appanage, or apanage (; french: apanage ), is the grant of an estate, title, office or other thing of value to a younger child of a sovereign, who would otherwise have no inheritance under the system of primogeniture. It was common in much o ...

s to the brothers of the king, extended to the feudal bishops the ill will he professed toward the feudal lords. He detested the Pragmatic Sanction as an act that strengthened ecclesiastical feudalism, and on 27 November 1461 he announced to the pope its suppression. At the same time he pleaded, as the demand of his Parliament, that for the future the pope should permit the collation

Collation is the assembly of written information into a standard order. Many systems of collation are based on numerical order or alphabetical order, or extensions and combinations thereof. Collation is a fundamental element of most office filin ...

of ecclesiastical benefices to be made either wholly or in part through the civil power. The Concordat of 1472 obtained from Rome very material concessions in this respect. At this time, besides "episcopal Gallicanism", against which pope and king were working together, we may trace, in the writings of the lawyers of the closing years of the 15th century, the beginnings of a "royal Gallicanism

Gallicanism is the belief that popular civil authority—often represented by the monarch's or the state's authority—over the Catholic Church is comparable to that of the Pope. Gallicanism is a rejection of ultramontanism; it has so ...

" which taught that in France the State should govern the Church.

Renaissance

Rivalry with "warrior popes"

"The Italian wars undertaken by Charles VIII (1493–98) and continued by Louis XII

Louis XII (27 June 14621 January 1515), was King of France from 1498 to 1515 and King of Naples from 1501 to 1504. The son of Charles, Duke of Orléans, and Maria of Cleves, he succeeded his 2nd cousin once removed and brother in law at the tim ...

(1498–1515), aided by an excellent corps of artillery and all the resources of French furia, to assert certain French claims over Naples and Milan, did not quite fulfill the dreams of the French kings. They had, however, a threefold result in the worlds of politics, religion, and art:

* politically, they led foreign powers to believe that France was a menace to the balance of power, and hence aroused alliances to maintain that balance, such, for instance, as the League of Venice (1495), and the Holy League (1511–12);

* from the point of view of art, they carried a breath of the Renaissance across the Alps;

* in the religious world they furnished France an opportunity on Italian soil of asserting for the first time the principles of royal Gallicanism

Gallicanism is the belief that popular civil authority—often represented by the monarch's or the state's authority—over the Catholic Church is comparable to that of the Pope. Gallicanism is a rejection of ultramontanism; it has so ...

.

Louis XII, and the emperor Maximilian, supported by the opponents of Pope

Louis XII, and the emperor Maximilian, supported by the opponents of Pope Julius II

Pope Julius II ( la, Iulius II; it, Giulio II; born Giuliano della Rovere; 5 December 144321 February 1513) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 1503 to his death in February 1513. Nicknamed the Warrior Pope or the ...

, convened in Pisa a council that threatened the rights of the Holy See

The Holy See ( lat, Sancta Sedes, ; it, Santa Sede ), also called the See of Rome, Petrine See or Apostolic See, is the jurisdiction of the Pope in his role as the bishop of Rome. It includes the apostolic episcopal see of the Diocese of R ...

. Matters looked very serious. The understanding between the pope and the French kings hung in the balance. Leo X

Pope Leo X ( it, Leone X; born Giovanni di Lorenzo de' Medici, 11 December 14751 December 1521) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 9 March 1513 to his death in December 1521.

Born into the prominent political an ...

understood the danger when the battle of Marignano

The Battle of Marignano was the last major engagement of the War of the League of Cambrai and took place on 13–14 September 1515, near the town now called Melegnano, 16 km southeast of Milan. It pitted the French army, composed of the b ...

opened to Francis I Francis I or Francis the First may refer to:

* Francesco I Gonzaga (1366–1407)

* Francis I, Duke of Brittany (1414–1450), reigned 1442–1450

* Francis I of France (1494–1547), King of France, reigned 1515–1547

* Francis I, Duke of Saxe-Lau ...

the road to Rome. The pope in alarm retired to Bologna, and the Concordat of 1516, negotiated between the cardinals and Duprat, the chancellor, and afterwards approved of by the Ecumenical Council of the Lateran, recognized the right of the King of France to nominate not only to 500 ecclesiastical benefices, as Charles VII had requested, but to all the benefices in his kingdom. It was a fair gift indeed. But if in matters temporal the bishops were thus in the king's hands, their institution in matters spiritual was reserved to the pope. Pope and king by common agreement thus put an end to an episcopal aristocracy such as the Gallicans of the great councils had dreamed of. The concordat between Leo X and Francis I was tantamount to a solemn repudiation of all the anti-Roman work of the great councils of the 15th century. The conclusion of this concordat was one of the reasons why France escaped the Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...

. From the moment that the disposal of church property, as laid down by the concordat, belonged to the civil power, royalty had nothing to gain from the Reformation. Whereas the kings of England and the German princelings saw in the reformation a chance to gain possession of ecclesiastical property, the kings of France, thanks to the concordat, were already in legal possession of those much-envied goods."

Struggle with the House of Austria

"When Charles V became King of Spain (1516) and emperor (1519), thus uniting in his person the hereditary possessions of the House of Austria and German as well as the old domains of the

"When Charles V became King of Spain (1516) and emperor (1519), thus uniting in his person the hereditary possessions of the House of Austria and German as well as the old domains of the House of Burgundy

The House of Burgundy () was a cadet branch of the Capetian dynasty, descending from Robert I, Duke of Burgundy, a younger son of King Robert II of France. The House ruled the Duchy of Burgundy from 1032–1361 and achieved the recognized title ...

– uniting moreover the Spanish monarchy with Naples, Sicily, Sardinia, the northern part of Africa, and certain lands in America, Francis I inaugurated a struggle between France and the House of Austria

The House of Habsburg (), alternatively spelled Hapsburg in Englishgerman: Haus Habsburg, ; es, Casa de Habsburgo; hu, Habsburg család, it, Casa di Asburgo, nl, Huis van Habsburg, pl, dom Habsburgów, pt, Casa de Habsburgo, la, Domus Hab ...

. After forty-four years of war, from the victory of Marignano to the treaty of Cateau-Cambrésis

A treaty is a formal, legally binding written agreement between actors in international law. It is usually made by and between sovereign states, but can include international organizations, individuals, business entities, and other legal pe ...

(1515-59), France relinquished hopes of retaining possession of Italy, but wrested the Bishoprics of Metz, Toul, and Verdun from the empire and had won back possession of Calais. The Spaniards were left in possession of Naples and the country around Milan, and their influence predominated throughout the Italian Peninsula. But the dream which Charles V had for a brief moment entertained of a worldwide empire had been shattered.

During this struggle against the House of Austria, France, for motives of political and military exigency, had been obliged to lean towards the Lutherans

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Catholic Church launched ...

of Germany, and even on the sultan. The foreign policy of France since the time of Francis I had been to seek exclusively the good of the nation and no longer to be guided by the interests of Catholicism

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

at large. The France of the Crusades even became the ally of the sultan

Sultan (; ar, سلطان ', ) is a position with several historical meanings. Originally, it was an Arabic abstract noun meaning "strength", "authority", "rulership", derived from the verbal noun ', meaning "authority" or "power". Later, it c ...

. But, by a strange anomaly, this new political grouping allowed France to continue its protection to the Christians of the East. In the Middle Ages it protected them by force of arms; but since the 16th century by treaties called capitulations, the first of which was drawn up in 1535. The spirit of French policy has changed, but it was always on France that the Christian communities of the East rely, and this protectorate continued to exist under the Third Republic, and later with the protectorates of the Middle East."

Wars of Religion

Appearance of Lutheranism and Calvinism

"The early part of the 16th century was marked by the growth of Protestantism in France, under the forms of

"The early part of the 16th century was marked by the growth of Protestantism in France, under the forms of Lutheranism

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and Protestant Reformers, reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Cathol ...

and of Calvinism

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John C ...

. Lutheranism was the first to make its entry. The minds of some in France were already prepared to receive it. Six years before Luther's time, the archbishop Lefebvre of Etaples (Faber Stapulensis), a protégé of Louis XII and of Francis I, had preached the necessity of reading the scriptures and of "bringing back religion to its primitive purity". A certain number of tradesmen, some of whom, for business reasons, had travelled in Germany, and a few priests, were infatuated with Lutheran ideas. Until 1534, Francis I was almost favorable to the Lutherans, and he even proposed to make Melanchthon President of the Collège de France

The Collège de France (), formerly known as the ''Collège Royal'' or as the ''Collège impérial'' founded in 1530 by François I, is a higher education and research establishment ('' grand établissement'') in France. It is located in Paris n ...

."

Beginning of the persecutions

However, "on learning, in 1534, that violent placards against the Church of Rome had been posted on the same day in many of the large towns, and even near the king's own room in the Château d'Amboise, he feared a Lutheran plot; an inquiry was ordered, and seven Lutherans were condemned to death and burned at the stake in Paris. Eminent ecclesiastics like du Bellay, Archbishop of Paris, and Sadolet, Bishop of Carpentras, deplored these executions and the Valdois massacre

A massacre is the killing of a large number of people or animals, especially those who are not involved in any fighting or have no way of defending themselves. A massacre is generally considered to be morally unacceptable, especially when per ...

ordered by d'Oppède, President of the Parliament of Aix, in 1545. Laymen, on the other hand, who ill understood the Christian gentleness of these prelates, reproached them with being slow and remiss in putting down heresy; and when, under Henry II, Calvinism crept in from Geneva, a policy of persecution was inaugurated. From 1547 to 1550, in less than three years, the ''chambre ardente'', a committee of the Parliament of Paris, condemned more than 500 persons to retract their beliefs, to imprisonment, or to death at the stake. Notwithstanding this, the Calvinists, in 1555, were able to organize themselves into Churches on the plan of that at Geneva; and, in order to bind these Churches more closely together, they held a synod in Paris in 1559. There were in France at that time seventy-two Reformed Churches; two years later, in 1561, the number had increased to 2000. The methods, too, of the Calvinist propaganda had changed. The earlier Calvinists, like the Lutherans, had been artists and workingmen, but in the course of time, in the South and in the West, a number of princes and noblemen joined their ranks. Among these were two princes of the blood, descendants of St. Louis: Anthony of Bourbon, who became King of Navarre through his marriage with Jeanne d'Albret, and his brother the Prince de Condé. Another name of note is that of Admiral de Coligny, nephew of that duke of Montmorency who was the Premier Baron of Christendom. Thus it came to pass that in France Calvinism was not longer a religious force, but had become a political and military cabal."

Massacre of St. Bartholomew

"Such was the beginning of the Wars of Religion. They had for their starting-point the conspiracy of Amboise (1560) by which the Protestant leaders aimed at seizing the person of Francis II, in order to remove him from the influence of Francis of Guise. During the reigns of Francis II, Charles IX, and Henry III, a powerful influence was exercised by the queen-mother, who made use of the conflicts between the opposing religious factions to establish more securely the power of her sons. In 1561,

"Such was the beginning of the Wars of Religion. They had for their starting-point the conspiracy of Amboise (1560) by which the Protestant leaders aimed at seizing the person of Francis II, in order to remove him from the influence of Francis of Guise. During the reigns of Francis II, Charles IX, and Henry III, a powerful influence was exercised by the queen-mother, who made use of the conflicts between the opposing religious factions to establish more securely the power of her sons. In 1561, Catherine de' Medici

Catherine de' Medici ( it, Caterina de' Medici, ; french: Catherine de Médicis, ; 13 April 1519 – 5 January 1589) was an Florentine noblewoman born into the Medici family. She was Queen of France from 1547 to 1559 by marriage to King ...

arranged for the Poissy discussion to try and bring about an understanding between the two creeds, but during the Wars of religion she ever maintained an equivocal attitude between both parties, favouring now the one and now the other, until the time came when, fearing that Charles IX would shake himself free of her influence, she took a large share of responsibility in the odious massacre of St. Bartholomew. There were eight of these wars in the space of thirty years. The first was started by a massacre of Calvinists at Vassy by the troopers of Guise (1 March 1562), and straightway both parties appealed for foreign aid. Catharine, who was at this time working in the Catholic cause, turned to Spain; Coligny and Condé turned to Elizabeth of England and turned over to her the port of Havre. Thus from the beginning were foreshadowed the lines which the Wars of religion would follow. They opened up France to the interference of such foreign princes as Elizabeth and Philip II, and to the plunder of foreign soldiers, such as those of the Duke of Alba and the German troopers (Reiter) called in by the Protestants. One after another, these wars ended in weak provisional treaties which did not last. Under the banners of the Reformation party or those of the League organized by the House of Guise to defend Catholicism, political opinions ranged themselves, and during these thirty years of civil disorder monarchical centralization was often in trouble of overthrow. Had the Guise party prevailed, the trend of policy adopted by the French monarchy towards Catholicism after the Concordat of Francis I would have been assuredly less Gallican. That concordat had placed the Church of France and its episcopate in the hands of the king. The old episcopal Gallicanism which held that the authority of the pope was not above that of the Church assembled in council and the royal Gallicanism which held that the king had no superior on the earth, not even the pope, were now allied against the papal monarchy strengthened by the Council of Trent. The consequence of all this was that the French kings refused to allow the decisions of that council to be published in France, and this refusal has never been withdrawn.

Edict of Nantes and the defeat of Protestantism

"At the end of the 16th century it seemed for an instant as though the home party of France was to shake off the yoke of Gallican opinions. Feudalism had been broken; the people were eager for liberty; the Catholics, disheartened by the corruption of the Valois court, contemplated elevating to the throne, in succession to Henry II who was childless, a member of the powerful House of Guise. In fact, the League had asked the Holy See to grant the wish of the people, and give France a Guise as king. Henry of Navarre, the heir presumptive to the throne, was a Protestant; Sixtus V had given him the choice of remaining a Protestant, and never reigning in France, or of abjuring his heresy, receiving absolution from the pope himself, and, together with it, the throne of France. But there was third solution possible, and the French episcopate foresaw it, namely that the abjuration should be made not to the pope but to the French bishops. Gallican susceptibilities would thus be satisfied, dogmatic orthodoxy would be maintained on the French throne, and moreover it would do away with the danger to which the unity of France was exposed by the proneness of a certain number of Leaguers to encourage the intervention of Spanish armies and the ambitions of the Spanish king, Philip II, who cherished the idea of setting his own daughter in the throne of France.

The abjuration of Henry IV made to the French bishops (25 July 1593) was a victory of Catholicism over Protestantism, but nonetheless it was the victory of episcopal Gallicanism over the spirit of the League. Canonically, the absolution given by the bishops to Henry IV was unavailing, since the pope alone could lawfully give it; but politically that absolution was bound to have a decisive effect. From the day that Henry IV became a Catholic, the League was beaten. Two French prelates went to Rome to crave absolution for Henry. Philip Neri

Philip Romolo Neri ( ; it, italics=no, Filippo Romolo Neri, ; 22 July 151526 May 1595), known as the "Second Apostle of Rome", after Saint Peter, was an Italian priest noted for founding a society of secular clergy called the Congregation of ...

ordered Baronius

Cesare Baronio (as an author also known as Caesar Baronius; 30 August 1538 – 30 June 1607) was an Italian cardinal and historian of the Catholic Church. His best-known works are his ''Annales Ecclesiastici'' ("Ecclesiastical Annals"), whi ...

smiling, no doubt, as he did so, to tell the pope, whose confessor he, Baronius was, that he himself could not have absolution until he had absolved the King of France. And on 17 September 1595, the Holy See solemnly absolved Henry IV, thereby sealing the reconciliation between the French monarchy and the Church of Rome.

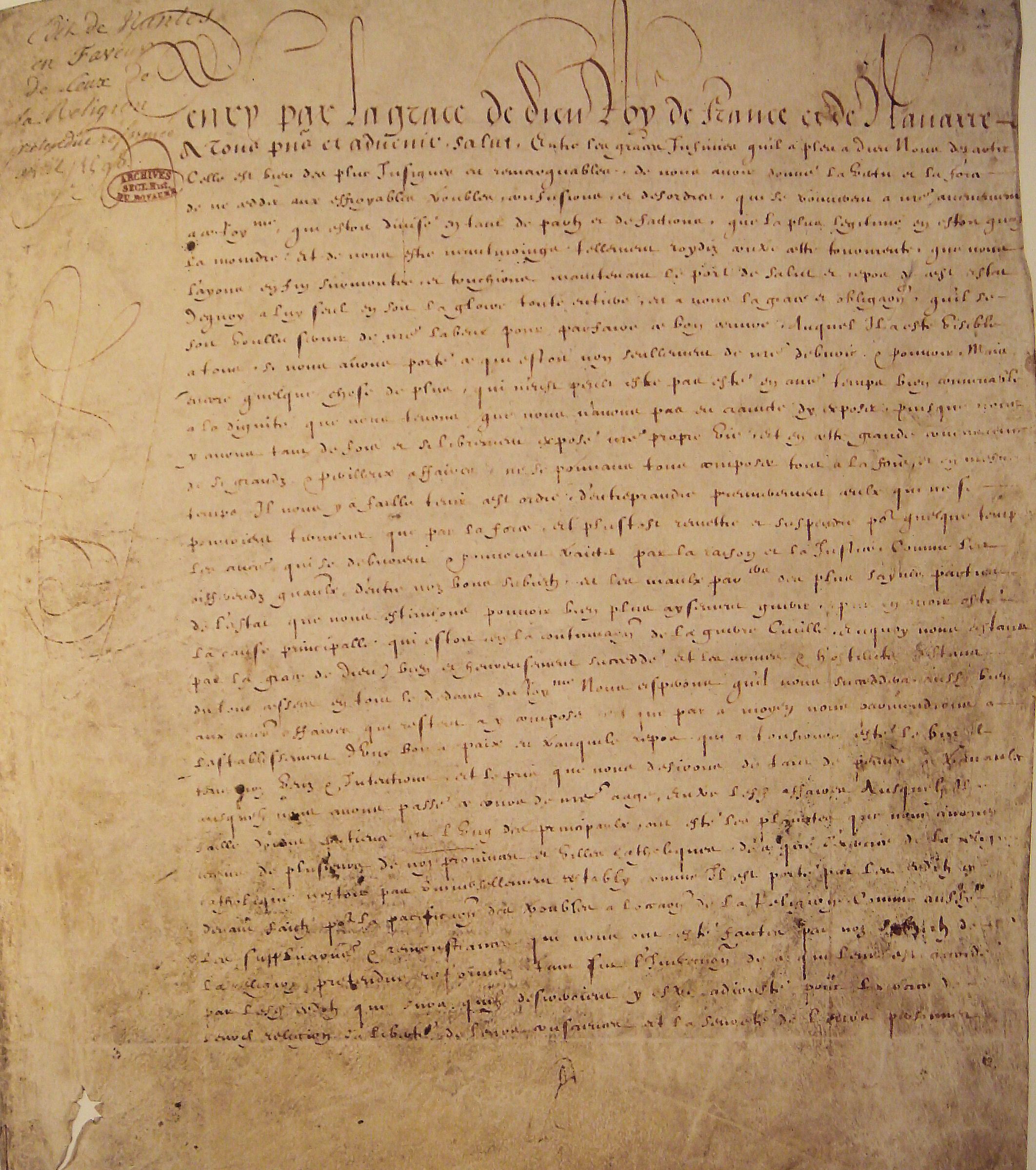

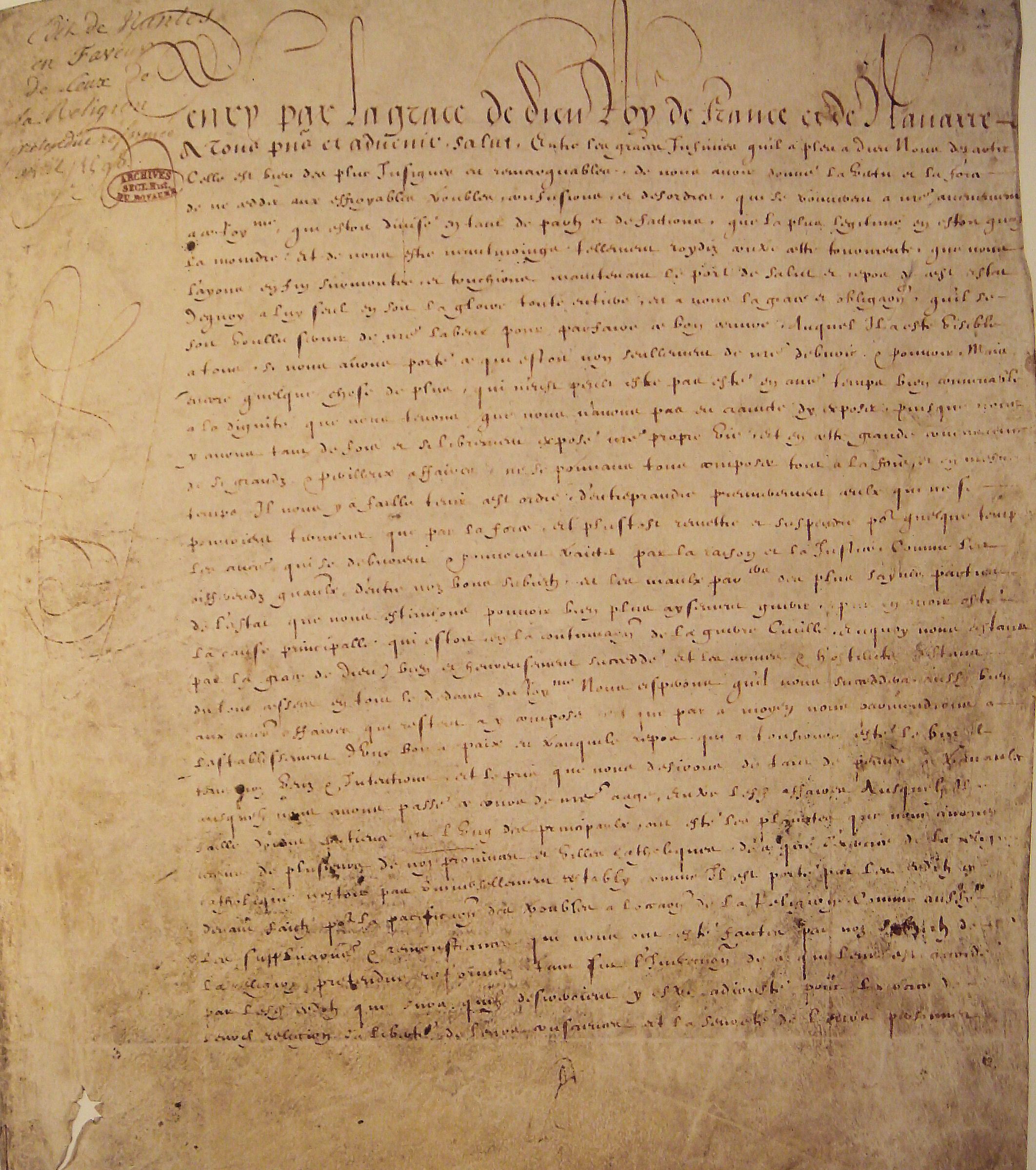

The accession of the Bourbon royal family was a defeat for Protestantism, but at the same time half a victory for Gallicanism. Ever since the year 1598 the dealings of the Bourbons with Protestantism were regulated by the

The accession of the Bourbon royal family was a defeat for Protestantism, but at the same time half a victory for Gallicanism. Ever since the year 1598 the dealings of the Bourbons with Protestantism were regulated by the Edict of Nantes

The Edict of Nantes () was signed in April 1598 by King Henry IV and granted the Calvinist Protestants of France, also known as Huguenots, substantial rights in the nation, which was in essence completely Catholic. In the edict, Henry aimed pr ...

. This instrument not only accorded the Protestants the liberty of practicing their religion in their own homes, in the towns and villages where it had been established before 1597, and in two localities in each bailliage, but also opened to them all employments and created mixed tribunals in which judges were chosen equally from among Catholics and Calvinists; it furthermore made them a political power by recognizing them for eight years as master of about one hundred towns which were known as "places of surety" (''places de sûreté'').

Under favour of the political causes of the Edict Protestants rapidly became an ''imperium in imperio'', and in 1627, at La Rochelle, they formed an alliance with England to defend, against the government of Louis XIII (1610–43), the privileges of which Cardinal Richelieu

Armand Jean du Plessis, Duke of Richelieu (; 9 September 1585 – 4 December 1642), known as Cardinal Richelieu, was a French clergyman and statesman. He was also known as ''l'Éminence rouge'', or "the Red Eminence", a term derived from the ...

, the king's minister, wished to deprive them. The taking of La Rochelle by the king's troops (November 1628), after a siege of fourteen months, and the submission of the Protestant rebels in the Cévenes, resulted in a royal decision which Richelieu called the Grâce d'Alais: the Protestants lost all their political privileges and all their "places of surety" but on the other hand freedom of worship and absolute equality with Catholics were guaranteed them. Both Cardinal Richelieu, and his successor, Cardinal Mazarin

Cardinal Jules Mazarin (, also , , ; 14 July 1602 – 9 March 1661), born Giulio Raimondo Mazzarino () or Mazarini, was an Italian cardinal, diplomat and politician who served as the chief minister to the Kings of France Louis XIII and Louis X ...

, scrupulously observed this guarantee."

Louis XIV and the rule of Gallicanism

Louis was a pious and devout king who saw himself as the head and protector of the Gallican Church, Louis made his devotions daily regardless of where he was, following the liturgical calendar regularly. Towards the middle and the end of his reign, the centre for the King's religious observances was usually the Chapelle Royale at Versailles. Ostentation was a distinguishing feature of daily Mass, annual celebrations, such as those of

Louis was a pious and devout king who saw himself as the head and protector of the Gallican Church, Louis made his devotions daily regardless of where he was, following the liturgical calendar regularly. Towards the middle and the end of his reign, the centre for the King's religious observances was usually the Chapelle Royale at Versailles. Ostentation was a distinguishing feature of daily Mass, annual celebrations, such as those of Holy Week

Holy Week ( la, Hebdomada Sancta or , ; grc, Ἁγία καὶ Μεγάλη Ἑβδομάς, translit=Hagia kai Megale Hebdomas, lit=Holy and Great Week) is the most sacred week in the liturgical year in Christianity. In Eastern Churches, w ...

, and special ceremonies. Louis established the Paris Foreign Missions Society

The Society of Foreign Missions of Paris (french: Société des Missions Etrangères de Paris, short M.E.P.) is a Roman Catholic missionary organization. It is not a religious institute, but an organization of secular priests and lay persons de ...

, but his informal alliance

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

with the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University ...

was criticised by the British for undermining Christendom.

Revocation of the Edict of Nantes

"Under

"Under Louis XIV

Louis XIV (Louis Dieudonné; 5 September 16381 September 1715), also known as Louis the Great () or the Sun King (), was List of French monarchs, King of France from 14 May 1643 until his death in 1715. His reign of 72 years and 110 days is the Li ...

a new policy was inaugurated. For twenty-five years the king forbade the Protestants everything that the Edict of Nantes did not expressly guarantee them, and then, foolishly imagining that Protestantism was on the wane, and that there remained in France only a few hundred obstinate heretics

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, in particular the accepted beliefs of a church or religious organization. The term is usually used in reference to violations of important religi ...

, he revoked the Edict of Nantes (1685) and began an oppressive policy against Protestants, which provoked the rising of the Camisards in 1703-05, and which lasted with alternations of severity and kindness until 1784, when Louis XVI was obliged to give Protestants their civil rights once more. The very manner in which Louis XIV, who imagined himself the religious head of his kingdom, set about the Revocation, was only an application of the religious maxims of Gallicanism."

Imposition of Gallicanism on the Catholic Church

"In the person of Louis XIV, indeed, Gallicanism was on the throne. At the States-General in 1614, the Third Estate

The estates of the realm, or three estates, were the broad orders of social hierarchy used in Christendom (Christian Europe) from the Middle Ages to early modern Europe. Different systems for dividing society members into estates developed and ...

had endeavoured to make the assembly commit itself to certain decidedly Gallican declarations, but the clergy, thanks to Cardinal Duperron, had succeeded in shelving the question; then Richelieu, careful not to embroil himself with the pope, had taken up the mitigated and very reserved form of Gallicanism represented by the theologian Duval." The lack of universal adherence to his religion did not sit well with Louis XIV's vision of perfected autocracy

Autocracy is a system of government in which absolute power over a state is concentrated in the hands of one person, whose decisions are subject neither to external legal restraints nor to regularized mechanisms of popular control (except per ...

: "Bending all else to his will, Louis XIV resented the presence of heretics among his subjects."

"Hence the persecution of Protestants and of Jansenists

Jansenism was an Early modern period, early modern Christian theology, theological movement within Catholicism, primarily active in the Kingdom of France, that emphasized original sin, human Total depravity, depravity, the necessity of divine g ...

. But at the same time he would never allow a papal bull to be published in France until his Parliament decided whether it interfered with the "liberties" of the French Church or the authority of the king. And in 1682 he invited the clergy of France to proclaim the independence of the Gallican Church in a manifesto of four articles, at least two of which, relating to the respective powers of a pope and a council, broached questions which only an ecumenical council could decide. In consequence of this a crisis arose between the Holy See and Louis XIV which led to thirty-five sees being left vacant in 1689. The policy of Louis XIV in religious matters was adopted also by Louis XV

Louis XV (15 February 1710 – 10 May 1774), known as Louis the Beloved (french: le Bien-Aimé), was King of France from 1 September 1715 until his death in 1774. He succeeded his great-grandfather Louis XIV at the age of five. Until he reache ...

. His way of striking at the Jesuits

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders = ...

in 1763 was in principle the same as that taken by Louis XIV to impose Gallicanism on the Church, the royal power pretending to mastery over the Church.

The domestic policy of the 17th-century Bourbons, aided by Scully, Richelieu, Mazarin, and Louvois, completed the centralization of the kingly power. Abroad, the fundamental maxim of their policy was to keep up the struggle against the House of Austria. The result of the diplomacy of Richelieu (1624–42) and of Mazarin (1643–61) was a fresh defeat for the House of Austria; French arms were victorious at Rocroi, Fribourg, Nördlingen, Lens, Sommershausen (1643–48), and by the Peace of Westphalia (1648) and that of the Pyrenees (1659), Alsace, Artois, and Roussillion were annexed to French territory. In the struggle Richelieu and Mazarin had the support of the Lutheran prince of Germany and of Protestant countries such as the Sweden of Gustavus Adolphus. In fact it may be laid down that during the Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War was one of the longest and most destructive conflicts in European history, lasting from 1618 to 1648. Fought primarily in Central Europe, an estimated 4.5 to 8 million soldiers and civilians died as a result of batt ...

, France upheld Protestantism. Louis XIV, on the contrary, who for many years was arbiter of the destinies of Europe, was actuated by purely religious motives in some of his wars. Thus the war against the Dutch Republic

The United Provinces of the Netherlands, also known as the (Seven) United Provinces, officially as the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands ( Dutch: ''Republiek der Zeven Verenigde Nederlanden''), and commonly referred to in historiograph ...

, and that against the League of Augsburg

The Grand Alliance was the anti-French coalition formed on 20 December 1689 between the Dutch Republic, England and the Holy Roman Empire. It was signed by the two leading opponents of France: William III, Stadtholder of the Dutch Republic and ( ...

, and his intervention in the affairs of England were in some respects the result of religious policy and of a desire to uphold Catholicism in Europe. The expeditions in the Mediterranean against the pirates of Barbary have all the halo of the old ideals of Christendom – ideals which in the days of Louis XIII had haunted the mind of Father Joseph, the famous confidant of Richelieu, and had inspired him with the dream of crusades led by France, once the House of Austria should have been defeated."

Catholic awakening under Louis XIV

Impact of the Council of Trent

The 17th century in France was ''par excellence'' a century of Catholic awakening. A number of bishops set about reforming their diocese according to the rules laid down by the Council of Trent, though its decrees did not run officially in France. The example of Italy bore fruit all over the country. Cardinal de la Rochefoucauld, Bishop of Claremont and afterwards of Senlis, had made the acquaintance of St.

The 17th century in France was ''par excellence'' a century of Catholic awakening. A number of bishops set about reforming their diocese according to the rules laid down by the Council of Trent, though its decrees did not run officially in France. The example of Italy bore fruit all over the country. Cardinal de la Rochefoucauld, Bishop of Claremont and afterwards of Senlis, had made the acquaintance of St. Charles Borromeo

Charles Borromeo ( it, Carlo Borromeo; la, Carolus Borromeus; 2 October 1538 – 3 November 1584) was the Archbishop of Milan from 1564 to 1584 and a cardinal of the Catholic Church. He was a leading figure of the Counter-Reformation combat ...

. Francis Taurugi, a companion of St. Philip Neri

Philip Romolo Neri ( ; it, italics=no, Filippo Romolo Neri, ; 22 July 151526 May 1595), known as the "Second Apostle of Rome", after Saint Peter, was an Italian priest noted for founding a society of secular clergy called the Congregation of ...

, was archbishop of Avignon. St. Francis de Sales

Francis de Sales (french: François de Sales; it, Francesco di Sales; 21 August 156728 December 1622) was a Bishop of Geneva and is revered as a saint in the Catholic Church. He became noted for his deep faith and his gentle approach to ...

Christianized lay society by his ''Introduction to the Devout Life'', which he wrote at the request of Henry IV. Cardinal de Bérulle and his disciple de Condren founded the Oratory

The Oratory stands to the north of Liverpool Anglican Cathedral in Merseyside, England. It was originally the mortuary chapel to St James Cemetery, and houses a collection of 19th-century sculpture and important funeral monuments as part of th ...

. St. Vincent de Paul

Vincent de Paul, CM (24 April 1581 – 27 September 1660), commonly known as Saint Vincent de Paul, was a Occitan French Catholic priest who dedicated himself to serving the poor.

In 1622 Vincent was appointed a chaplain to the galleys. Afte ...

, in founding the Priests of the Mission, and M. Olier, in founding the Sulpicians, prepared the uplifting of the secular clergy and the development of the ''grands séminaires''.

First missionaries

It was the period, too, when France began to build up her

It was the period, too, when France began to build up her colonial empire

A colonial empire is a collective of territories (often called colonies), either contiguous with the imperial center or located overseas, settled by the population of a certain state and governed by that state.

Before the expansion of early mode ...

, when Samuel de Champlain

Samuel de Champlain (; Fichier OrigineFor a detailed analysis of his baptismal record, see RitchThe baptism act does not contain information about the age of Samuel, neither his birth date nor his place of birth. – 25 December 1635) was a Fr ...

was founding prosperous settlements in Acadia and Canada. At the suggestion of Père Coton, confessor to Henry IV, the Jesuits followed in the wake of the colonists; they made Quebec the capital of all that country, and gave it a Frenchman, Mgr. de Montmorency-Laval as its first bishop. The first apostles to the Iroquois were the French Jesuits, Lallemant and de Brébeuf; and it was the French missionaries

A missionary is a member of a religious group which is sent into an area in order to promote its faith or provide services to people, such as education, literacy, social justice, health care, and economic development.Thomas Hale 'On Being a Mi ...

, as much as the traders who opened postal communication over 500 leagues of countries between the French colonies in Louisiana and Canada. In China, the French Jesuits, by their scientific labours, gained a real influence at court and converted at least one Chinese prince. Lastly, from the beginning of this same 17th century, under the protection of Gontaut-Biron, Marquis de Salignac, Ambassador of France, dates the establishment of the Jesuits at Smyrna

Smyrna ( ; grc, Σμύρνη, Smýrnē, or , ) was a Greek city located at a strategic point on the Aegean coast of Anatolia. Due to its advantageous port conditions, its ease of defence, and its good inland connections, Smyrna rose to prom ...

, in the Archipelago, in Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

, and at Cairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the largest urban agglomeration in Africa, the Arab world and the Middle East: The Greater Cairo metr ...

. A Capuchin, Père Joseph du Tremblay, Richelieu's confessor, established many Capuchin foundations in the East. A pious Parisian lady, Madame Ricouard, gave a sum of money for the erection of a bishopric at Babylon, and its first bishop was a French Carmelite, Jean Duval. St. Vincent De Paul sent the Lazarists into the galleys and prisons of Barbary, and among the islands of Madagascar

Madagascar (; mg, Madagasikara, ), officially the Republic of Madagascar ( mg, Repoblikan'i Madagasikara, links=no, ; french: République de Madagascar), is an island country in the Indian Ocean, approximately off the coast of East Afric ...

, Bourbon, Mauritius

Mauritius ( ; french: Maurice, link=no ; mfe, label= Mauritian Creole, Moris ), officially the Republic of Mauritius, is an island nation in the Indian Ocean about off the southeast coast of the African continent, east of Madagascar. It ...

, and the Mascarenes, to take possession of them in the name of France. On the advice of Jesuit Father de Rhodes, Propaganda and France decided to erect bishoprics in Annam, and in 1660 and 1661 three French bishops, François Pallu, Pierre Lambert de Lamothe, and Cotrolendi, set out for the East. It was the activities of the French missionaries that paved the way for the visit of the Siamese envoys to the court of Louis XIV. In 1663 the Seminary for Foreign Missions was founded, and in 1700 the ''Société des Missions Etrangères

The Society of Foreign Missions of Paris (french: Société des Missions Etrangères de Paris, short M.E.P.) is a Roman Catholic missionary organization. It is not a religious institute, but an organization of secular priests and lay persons ...

'' received its approved constitution, which has never been altered."

Enlightenment and Revolution

"Religiously speaking, during the 18th century the alliance of parliamentary Gallicanism and Jansenism weakened the idea of religion in an atmosphere already threatened by philosophers, and although the monarchy continued to keep the style and title of "Most Christian", unbelief and libertinage were harboured, and at times defended, at the court of Louis XV (1715–74), in the salons, and among the aristocracy.

Wars with England

"Politically, the traditional strife between France and the House of Austria ended, about the middle of the 18th century, with the famous Renversement des Alliances. This century is filled with that struggle between France and England which may be called the second Hundred Years' War, during which England had for an ally Frederick II, King of Prussia, a country which was then rapidly rising in importance. The command of the sea was at stake. In spite of men like Dupliex, Lally-Tollendal, and Montcalm, France lightly abandoned its colonies by successive treaties, the most important of which was the Treaty of Paris (1763). The acquisition of Lorraine (1766), and the purchase of Corsica from the Genoese (1768), were poor compensations for these losses; and when, under Louis XVI

Louis XVI (''Louis-Auguste''; ; 23 August 175421 January 1793) was the last King of France before the fall of the monarchy during the French Revolution. He was referred to as ''Citizen Louis Capet'' during the four months just before he was ...

, the French navy once more raised its head, it helped in the revolt of the English colonies in America, and thus seconded the emancipation of the United States (1778-83)."

New ideas of the Enlightenment

"The movement of thought of which

"The movement of thought of which Montesquieu

Charles Louis de Secondat, Baron de La Brède et de Montesquieu (; ; 18 January 168910 February 1755), generally referred to as simply Montesquieu, was a French judge, man of letters, historian, and political philosopher.

He is the princi ...

, Voltaire

François-Marie Arouet (; 21 November 169430 May 1778) was a French Enlightenment writer, historian, and philosopher. Known by his '' nom de plume'' M. de Voltaire (; also ; ), he was famous for his wit, and his criticism of Christianity—e ...

, Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (, ; 28 June 1712 – 2 July 1778) was a Genevan philosopher, writer, and composer. His political philosophy influenced the progress of the Age of Enlightenment throughout Europe, as well as aspects of the French Revolu ...

, and Diderot

Denis Diderot (; ; 5 October 171331 July 1784) was a French philosopher, art critic, and writer, best known for serving as co-founder, chief editor, and contributor to the '' Encyclopédie'' along with Jean le Rond d'Alembert. He was a promi ...

, each in his own fashion, had been protagonists, an impatience provoked by the abuses incident to a too centralized monarchy, and the yearning for equality which was deeply agitating the French people, all prepared the explosion of the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are conside ...

. That upheaval has been too long regarded as a break in the history of France. The researches of Albert Sorel have proved that the diplomatic traditions of the old regime were perpetuated under the Revolution; the idea of the State's ascendancy over the Church, which had actuated the ministers of Louis XIV and the adherents of Parliament – the parliamentaires – in the days of Louis XV, reappears with the authors of the "Civil Constitution of the Clergy", even as the centralizing spirit of the old monarchy reappears with the administrative officials and the commissaries of the convention. It is easier to cut off a king's head than to change the mental constitution of a people."

Revolution

Rejection of the Catholic Church

"The Constituent Assembly (5 May 1789-30 September 1791) rejected the motion of the Abbé d'Eymar declaring the Catholic religion to be the religion of the State, but it did not thereby mean to place the Catholic religion on the same level as other religions. Voulland, addressing the Assembly on the seemliness of having one dominant religion, declared that the Catholic religion was founded on too pure a moral basis not to be given the first place. Article 10 of the Declarations of the rights of man (August 1789) proclaimed toleration, stipulating "that no one ought to be interfered with because of his opinions, even religious, provided that their manifestation does not disturb public order" (''pourvu que leur manifestation ne trouble pas l'ordre public établi par là''). It was by virtue of the suppression of feudal privileges, and in accordance with the ideas professed by the lawyers of the old regime where church property was in question, that the Constituent Assembly abolished tithes and confiscated the possessions of the Church, replacing them by an annuity grant from the treasury.

"The Constituent Assembly (5 May 1789-30 September 1791) rejected the motion of the Abbé d'Eymar declaring the Catholic religion to be the religion of the State, but it did not thereby mean to place the Catholic religion on the same level as other religions. Voulland, addressing the Assembly on the seemliness of having one dominant religion, declared that the Catholic religion was founded on too pure a moral basis not to be given the first place. Article 10 of the Declarations of the rights of man (August 1789) proclaimed toleration, stipulating "that no one ought to be interfered with because of his opinions, even religious, provided that their manifestation does not disturb public order" (''pourvu que leur manifestation ne trouble pas l'ordre public établi par là''). It was by virtue of the suppression of feudal privileges, and in accordance with the ideas professed by the lawyers of the old regime where church property was in question, that the Constituent Assembly abolished tithes and confiscated the possessions of the Church, replacing them by an annuity grant from the treasury.

Persecution of the priesthood