History of Portland, Oregon on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of the city of Portland, Oregon, began in 1843 when business partners William Overton and

The history of the city of Portland, Oregon, began in 1843 when business partners William Overton and

The site of the future city of

The site of the future city of  On March 30, 1849, Lownsdale split the Portland claim with

On March 30, 1849, Lownsdale split the Portland claim with

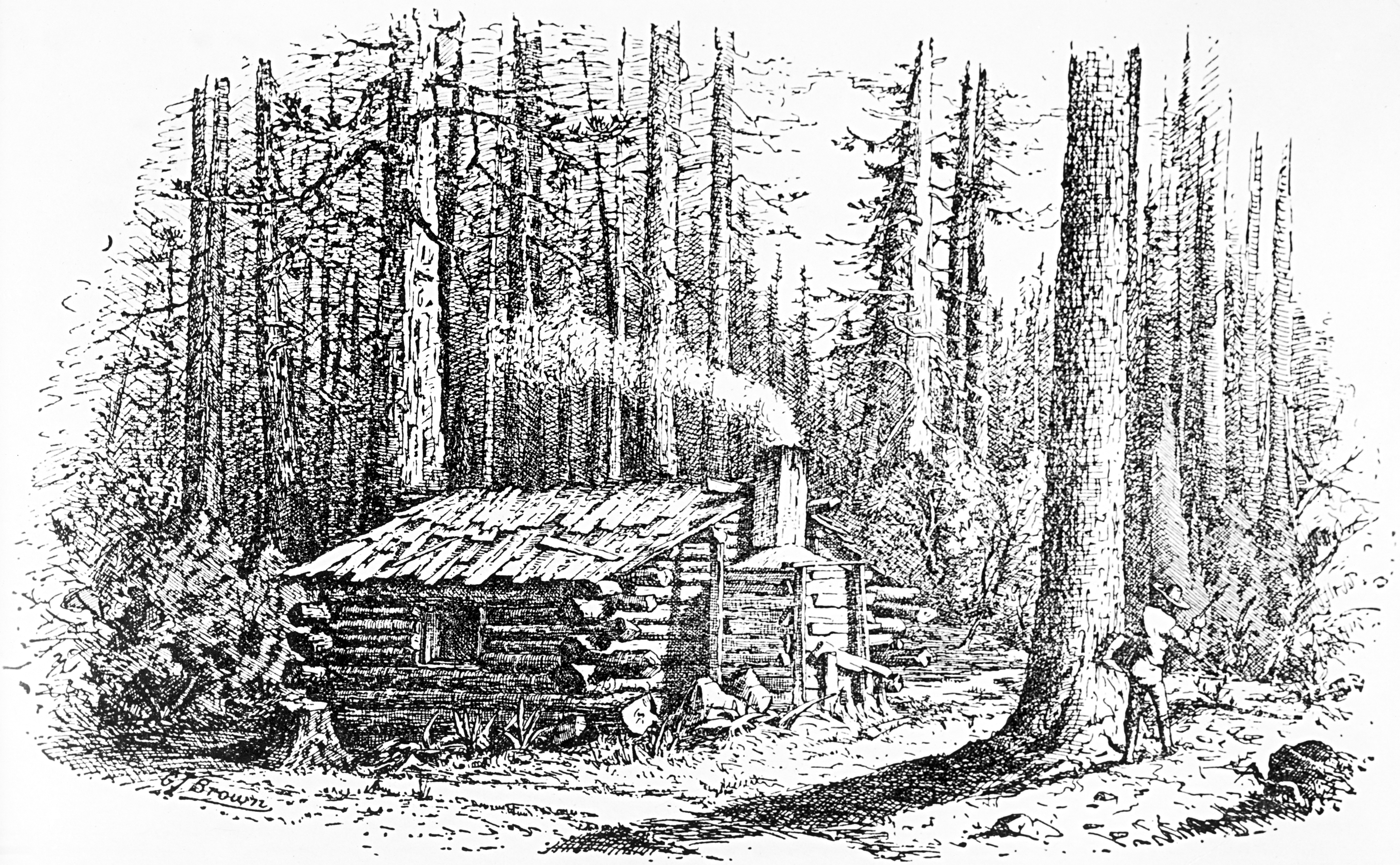

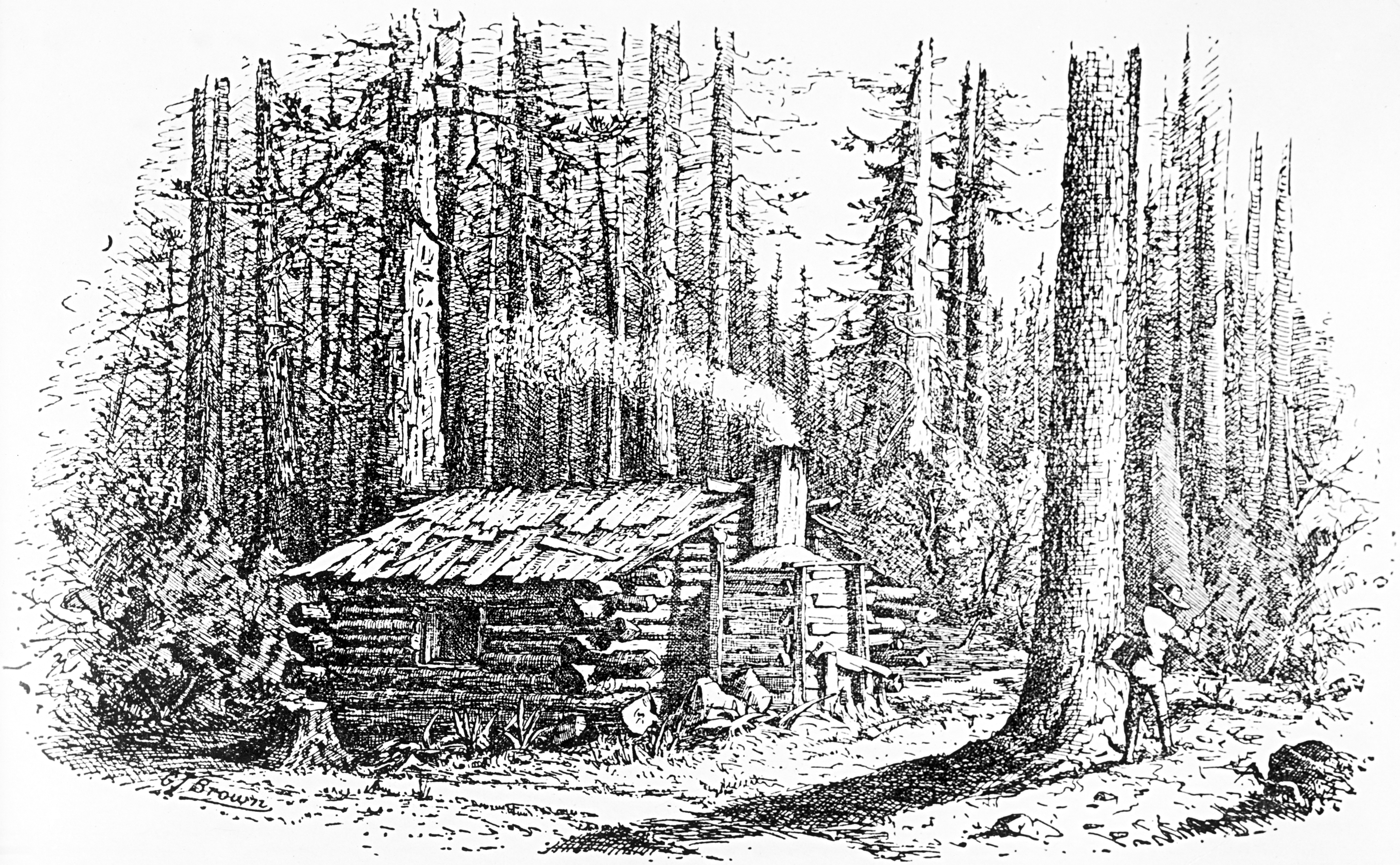

Portland as depicted in Frances Fuller Victor's ''Atlantis Arisen'' (1891).

A major fire swept through downtown in August 1873, destroying 20 blocks along the west side of the Willamette between Yamhill and Morrison. The fire caused $1.3 million in damage. In 1889, ''

Portland as depicted in Frances Fuller Victor's ''Atlantis Arisen'' (1891).

A major fire swept through downtown in August 1873, destroying 20 blocks along the west side of the Willamette between Yamhill and Morrison. The fire caused $1.3 million in damage. In 1889, ''

/ref> This merger was followed by the annexation of the neighboring city of Sellwood in 1893.

In 1905, Portland was the host city of the

In 1905, Portland was the host city of the  On June 9, 1934, approximately 1,400 members of the

On June 9, 1934, approximately 1,400 members of the

abstract

/ref> Several arts

full text online

* Abbott, Carl. ''Portland in Three Centuries: The Place and the People'' (Oregon State University Press; 2011) 192 pages; scholarly histor

online

* Abbott, Carl. ''Portland : gateway to the Northwest'' (1985

online

* In Three Volumes

Volume 1

Volume 2

Volume 3

* Johnston, Robert D. ''The Radical Middle Class: Populist Democracy and the Question of Capitalism in Progressive Era Portland, Oregon'' (2003) * * Leeson, Fred. ''Rose City Justice: A Legal History of Portland, Oregon'' (Portland: Oregon Historical Society Press, 1998) * *

online full text

also se

online review

* * MacColl, E. Kimbark, and Harry H. Stein. "The Economic Power of Portland's Early Merchants, 1851-1861." ''Oregon Historical Quarterly'' 89.2 (1988): 117-156. * Elma MacGibbons reminiscences of her travels in the United States starting in 1898, which were mainly in Oregon and Washington. Includes chapter "Portland, the western hub." * Merriam, Paul Gilman. "Portland, Oregon, 1840–1890: A Social and Economic History". Ph.D. dissertation. University of Oregon, Department of History, 1971. * Mullins, William H. ''The Depression and the Urban West Coast, 1929-1933: Los Angeles, San Francisco, Seattle, and Portland'' (2000) * * * Scott, H. W. ed. ''History of Portland, Oregon, with Illustrations and Biographical Sketches of Prominent Citizens and Pioneers'' (D. Mason & Company, 1890) 792p

full text online

PdxHistory.comHistorical Timeline

at Portland City Auditor's Office

Wartime Portland

at Oregon Historical Society *Portland page a

Oregon History Project

(Oregon Historical Society)

at ''Willamette Week''

Transportation history

Portland Bureau of Transportation

A pictorial history of the Portland Waterfront

* {{Oregon Brief History Willamette Valley

The history of the city of Portland, Oregon, began in 1843 when business partners William Overton and

The history of the city of Portland, Oregon, began in 1843 when business partners William Overton and Asa Lovejoy

Asa Lawrence Lovejoy (March 14, 1808 – September 10, 1882) was an American pioneer and politician in the region that would become the U.S. state of Oregon. He is best remembered as a founder of the city of Portland, Oregon. He was an attorney ...

filed to claim land on the west bank of the Willamette River

The Willamette River ( ) is a major tributary of the Columbia River, accounting for 12 to 15 percent of the Columbia's flow. The Willamette's main stem is long, lying entirely in northwestern Oregon in the United States. Flowing northward b ...

in Oregon Country

Oregon Country was a large region of the Pacific Northwest of North America that was subject to a long dispute between the United Kingdom and the United States in the early 19th century. The area, which had been created by the Treaty of 1818, co ...

. In 1845 the name of Portland was chosen for this community by coin toss. February 8, 1851, the city was incorporated. Portland has continued to grow in size and population, with the 2010 Census showing 583,776 residents in the city.

Early history

The land today occupied byMultnomah County, Oregon

Multnomah County is one of the 36 counties in the U.S. state of Oregon. As of the 2020 census, the county's population was 815,428. Multnomah County is part of the Portland– Vancouver– Hillsboro, OR–WA Metropolitan Statistical Area. T ...

, was inhabited for centuries by two bands of Upper Chinook Indians. The Multnomah people settled on and around Sauvie Island

Sauvie Island, in the U.S. state of Oregon, originally Wapato Island or Wappatoo Island, is the largest island along the Columbia River, at , and one of the largest river islands in the United States. It lies approximately ten miles northwest o ...

and the Cascades Indians settled along the Columbia Gorge

The Columbia River Gorge is a canyon of the Columbia River in the Pacific Northwest of the United States. Up to deep, the canyon stretches for over as the river winds westward through the Cascade Range, forming the boundary between the state ...

. These groups fished and traded along the river and gathered berries, wapato and other root vegetables. The nearby Tualatin Plains provided prime hunting grounds. Eventually, contact with Europeans resulted in the decimation of native tribes by smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

and malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other animals. Malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, tiredness, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or death. ...

.

Founding

The site of the future city of

The site of the future city of Portland, Oregon

Portland (, ) is a port city in the Pacific Northwest and the largest city in the U.S. state of Oregon. Situated at the confluence of the Willamette and Columbia rivers, Portland is the county seat of Multnomah County, the most populous ...

, was known to American, Canadian, and British traders, trappers and settlers of the 1830s and early 1840s as "The Clearing," a small stopping place along the west bank of the Willamette River

The Willamette River ( ) is a major tributary of the Columbia River, accounting for 12 to 15 percent of the Columbia's flow. The Willamette's main stem is long, lying entirely in northwestern Oregon in the United States. Flowing northward b ...

used by travelers ''en route'' between Oregon City

)

, image_skyline = McLoughlin House.jpg

, imagesize =

, image_caption = The McLoughlin House, est. 1845

, image_flag =

, image_seal = Oregon City seal.png

, image_map ...

and Fort Vancouver

Fort Vancouver was a 19th century fur trading post that was the headquarters of the Hudson's Bay Company's Columbia Department, located in the Pacific Northwest. Named for Captain George Vancouver, the fort was located on the northern bank of ...

. As early as 1840, Massachusetts sea captain John Couch logged an encouraging assessment of the river’s depth adjacent to The Clearing, noting its promise of accommodating large ocean-going vessels, which could not ordinarily travel up-river as far as Oregon City, the largest Oregon settlement at the time. In 1843, Tennessee

Tennessee ( , ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. Tennessee is the List of U.S. states and territories by area, 36th-largest by ...

pioneer William Overton and Boston, Massachusetts lawyer Asa Lovejoy filed a land claim with Oregon's provisional government that encompassed The Clearing and nearby waterfront and timber land. Legend has it that Overton had prior rights to the land but lacked funds, so he agreed to split the claim with Lovejoy, who paid the 25-cent filing fee.

Bored with clearing trees and building roads, Overton sold his half of the claim to Francis W. Pettygrove

Francis William Pettygrove (1812 – October 5, 1887) was a pioneer and one of the founders of the cities of Portland, Oregon, and Port Townsend, Washington. Born in Maine, he re-located to the Oregon Country in 1843 to establish a store in O ...

of Portland, Maine

Portland is the largest city in the U.S. state of Maine and the seat of Cumberland County. Portland's population was 68,408 in April 2020. The Greater Portland metropolitan area is home to over half a million people, the 104th-largest metropo ...

, in 1845. When it came time to name their new town, Pettygrove and Lovejoy both had the same idea: to name it after his home town. They flipped a coin to decide, and Pettygrove won. On November 1, 1846, Lovejoy sold his half of the land claim to Benjamin Stark

Benjamin Stark (June 26, 1820October 10, 1898) was an American merchant and politician in Oregon. A native of Louisiana, he purchased some of the original tracts of land for the city of Portland. He later served in the Oregon House of Representat ...

, as well as his half-interest in a herd of cattle for $1,215.

Three years later, Pettygrove had lost interest in Portland and become enamored with the California Gold Rush

The California Gold Rush (1848–1855) was a gold rush that began on January 24, 1848, when gold was found by James W. Marshall at Sutter's Mill in Coloma, California. The news of gold brought approximately 300,000 people to California f ...

. On September 22, 1848, he sold the entire townsite, save only for 64 sold lots and two blocks each for himself and Stark, to Daniel H. Lownsdale, a tanner. Although Stark owned fully half of the townsite, Pettygrove "largely ignor dStark's interest", in part because Stark was on the east coast with no immediate plans to return to Oregon. Lownsdale paid for the site with $5,000 in leather, which Pettygrove presumably resold in San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish for " Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the fourth most populous in California and 17t ...

for a large profit.

On March 30, 1849, Lownsdale split the Portland claim with

On March 30, 1849, Lownsdale split the Portland claim with Stephen Coffin

Stephen Coffin (1807 – 1882) was an investor, promoter, builder, and militia officer in mid-19th century Portland in the U.S. state of Oregon. Born in Maine, he moved to Oregon City in 1847, and in 1849 he bought a half-interest in the original ...

, who paid $6,000 for his half. By August 1849, Captain John Couch and Stark were pressuring Lownsdale and Coffin for Stark's half of the claim; Stark had been absent, but was using the claim as equity in an East Coast-California shipping business with the Sherman Brothers of New York.

In December 1849, William W. Chapman bought what he believed was a third of the overall claim for $26,666, plus his provision of free legal services for the partnership. In January 1850, Lownsdale had to travel to San Francisco to negotiate on the land claim with Stark, leaving Chapman with power of attorney

A power of attorney (POA) or letter of attorney is a written authorization to represent or act on another's behalf in private affairs (which may be financial or regarding health and welfare), business, or some other legal matter. The person auth ...

. Stark and Lownsdale came to an agreement on March 1, 1850, which gave to Stark the land north of Stark Street and about $3,000 from land already sold in this area. This settlement reduced the size of Chapman's claim by approximately 10%. Lownsdale returned to Portland in April 1850, where the terms were presented to an unwilling Chapman and Coffin, but who agreed after negotiations with Couch. While Lownsdale was gone, Chapman had given himself block 81 on the waterfront and sold all of the lots on it, and this block was included in the Stark settlement area. Couch's negotiations excluded this property from Stark's claim, allowing Chapman to retain the profits on the lot.

Portland existed in the shadow of Oregon City, the territorial capital upstream at Willamette Falls

The Willamette Falls is a natural waterfall on the Willamette River between Oregon City, Oregon, Oregon City and West Linn, Oregon, in the United States. It is the largest waterfall in the Northwestern United States by volume, and the seventeen ...

. However, Portland's location at the Willamette's confluence with the Columbia River

The Columbia River ( Upper Chinook: ' or '; Sahaptin: ''Nch’i-Wàna'' or ''Nchi wana''; Sinixt dialect'' '') is the largest river in the Pacific Northwest region of North America. The river rises in the Rocky Mountains of British Columbia ...

, accessible to deep-draft vessels, gave it a key advantage over the older peer. It also triumphed over early rivals such as Milwaukie

Milwaukie is a city mostly in Clackamas County, Oregon, United States; a very small portion of the city extends into Multnomah County. The population was 20,291 at the 2010 census. Founded in 1847 on the banks of the Willamette River, the c ...

and Linnton. In its first census in 1850, the city's population was 821 and, like many frontier towns, was predominantly male, with 653 male whites, 164 female whites and four "free colored" individuals. It was already the largest settlement in the Pacific Northwest, and while it could boast about its trading houses, hotels and even a newspaper—the ''Weekly Oregonian''—it was still very much a frontier village, derided by outsiders as "Stumptown" and "Mudtown." It was a place where "stumps from fallen firs lay scattered dangerously about Front and First Streets … humans and animals, carts and wagons slogged through a sludge of mud and water … sidewalks often disappeared during spring floods."

The first firefighting

Firefighting is the act of extinguishing or preventing the spread of unwanted fires from threatening human lives and destroying property and the environment. A person who engages in firefighting is known as a firefighter.

Firefighters typically ...

service was established in the early 1850s, with the volunteer Pioneer Fire Engine Company. In 1854, the city council voted to form the Portland Fire Department, and following an 1857 reorganization it encompassed three engine companies and 157 volunteer firemen.

Late 19th century

Portland as depicted in Frances Fuller Victor's ''Atlantis Arisen'' (1891).

A major fire swept through downtown in August 1873, destroying 20 blocks along the west side of the Willamette between Yamhill and Morrison. The fire caused $1.3 million in damage. In 1889, ''

Portland as depicted in Frances Fuller Victor's ''Atlantis Arisen'' (1891).

A major fire swept through downtown in August 1873, destroying 20 blocks along the west side of the Willamette between Yamhill and Morrison. The fire caused $1.3 million in damage. In 1889, ''The Oregonian

''The Oregonian'' is a daily newspaper based in Portland, Oregon, United States, owned by Advance Publications. It is the oldest continuously published newspaper on the U.S. west coast, founded as a weekly by Thomas J. Dryer on December 4, 18 ...

'' called Portland "the most filthy city in the Northern States", due to the unsanitary sewers and gutters. The ''West Shore'' reported "The new sidewalks put down this year are a disgrace to a Russian village."

The first Morrison Street Bridge opened in 1887 and was the first bridge across the Willamette River in Portland.

Portland was the major port in the Pacific Northwest

The Pacific Northwest (sometimes Cascadia, or simply abbreviated as PNW) is a geographic region in western North America bounded by its coastal waters of the Pacific Ocean to the west and, loosely, by the Rocky Mountains to the east. Thou ...

for much of the 19th century, until the 1890s, when direct railroad access between the deepwater harbor in Seattle

Seattle ( ) is a seaport city on the West Coast of the United States. It is the seat of King County, Washington. With a 2020 population of 737,015, it is the largest city in both the state of Washington and the Pacific Northwest region o ...

and points east, by way of Stampede Pass, was built. Goods could then be transported from the northwest coast to inland cities without the need to navigate the dangerous bar at the mouth of the Columbia River

The Columbia River ( Upper Chinook: ' or '; Sahaptin: ''Nch’i-Wàna'' or ''Nchi wana''; Sinixt dialect'' '') is the largest river in the Pacific Northwest region of North America. The river rises in the Rocky Mountains of British Columbia ...

.

The city merged with Albina and East Portland

East Portland was a city in the U.S. state of Oregon that was consolidated into Portland in 1891. In modern usage, the term generally refers to the portion of present-day Portland that lies east of 82nd Avenue, most of which the City of Portland ...

in 1891. This made Portland the 41st largest city in the country, with approximately 70,000 residents.Portland Timeline: 1843 to 1901, City of Portland Auditor's Office/ref> This merger was followed by the annexation of the neighboring city of Sellwood in 1893.

Early 20th century

In 1905, Portland was the host city of the

In 1905, Portland was the host city of the Lewis and Clark Centennial Exposition

The Lewis and Clark Centennial Exposition, commonly also known as the Lewis and Clark Exposition, and officially known as the Lewis and Clark Centennial and American Pacific Exposition and Oriental Fair, was a worldwide exposition held in Portlan ...

, a world's fair

A world's fair, also known as a universal exhibition or an expo, is a large international exhibition designed to showcase the achievements of nations. These exhibitions vary in character and are held in different parts of the world at a specif ...

. This event increased recognition of the city, which contributed to a doubling of the population of Portland, from 90,426 in 1900 to 207,214 in 1910.

In 1912 the city's 52 distinctive bronze temperance fountains known locally as " Benson bubblers" were installed around the downtown area by logging magnate Simon Benson

Simon Benson (September 9, 1851 – August 5, 1942) was a noted Norwegian-born American businessman and philanthropist who made his mark in the city of Portland, Oregon.

Biography

Background

Simon Benson was born Simen Bergersen Klæve in th ...

.

In 1915, the city merged with Linnton and St. Johns.

July 1913 saw a free speech fight when, during a strike by women workers at the Oregon Packing Company, Mayor Henry Albee declared street speaking illegal, with an exception made for religious speech. This declaration was intended to stop public speeches by the Industrial Workers of the World

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), members of which are commonly termed "Wobblies", is an international labor union that was founded in Chicago in 1905. The origin of the nickname "Wobblies" is uncertain. IWW ideology combines general ...

in support of the strikers.

On June 9, 1934, approximately 1,400 members of the

On June 9, 1934, approximately 1,400 members of the International Longshoremen's Association

The International Longshoremen's Association (ILA) is a North American labor union representing longshore workers along the East Coast of the United States and Canada, the Gulf Coast, the Great Lakes, Puerto Rico, and inland waterways. The ILA h ...

(ILA) participated in the West Coast waterfront strike, which shut down shipping in every port along the West Coast.''Dock Strike: History of the 1934 Waterfront Strike in Portland, Oregon'' by Roger Buchanan (1975) The demands of the ILA were: recognition of the union; wage increases from 85 cents to $1.00 per hour straight time and from $1.25 to $1.50 per hour overtime; a six-hour workday and 30-hour work week; and a closed shop with the union in control of hiring. They were also frustrated that shipping subsidies from the government, in place since industry distress in the 1920s, were leading to larger profits for the shipping companies that weren't passed down to the workers. There were numerous incidents of violence between strikers and police, including strikers storming the ''Admiral Evans'', which was being used as a hotel for strikebreakers; police shooting four strikers at Terminal 4 in St. Johns; and special police shooting at Senator Robert Wagner

Robert John Wagner Jr. (born February 10, 1930) is an American actor of stage, screen, and television. He is known for starring in the television shows '' It Takes a Thief'' (1968–1970), ''Switch'' (1975–1978), and '' Hart to Hart'' (1979� ...

of New York as he inspected the site of the previous shooting. The longshoremen resumed work on July 31, 1934, after voting to arbitrate

Arbitration is a form of alternative dispute resolution (ADR) that resolves disputes outside the judiciary courts. The dispute will be decided by one or more persons (the 'arbitrators', 'arbiters' or 'arbitral tribunal'), which renders the ' ...

. The arbitration decision was handed down on October 12, 1934, awarding the strikers with recognition of the ILA; higher pay of 95 cents per hour straight time and $1.40 per hour overtime, retroactive to the return to work on July 31; six-hour workdays and 30-hour workweeks, and a union hiring hall

In organized labor, a hiring hall is an organization, usually under the auspices of a labor union, which has the responsibility of furnishing new recruits for employers who have a collective bargaining agreement with the union. It may also refer t ...

managed jointly by the union and management – though the union selected the dispatcher – in every port along the entire West Coast.

World War II

In 1940, Portland was on the brink of an economic and population boom, fueled by over $2 billion spent by the U.S. Congress on expanding theBonneville Power Administration

The Bonneville Power Administration (BPA) is an American federal agency operating in the Pacific Northwest. BPA was created by an act of Congress in 1937 to market electric power from the Bonneville Dam located on the Columbia River and to cons ...

, the need to produce materiel

Materiel (; ) refers to supplies, equipment, and weapons in military supply-chain management, and typically supplies and equipment in a commercial supply chain context.

In a military context, the term ''materiel'' refers either to the spec ...

for Great Britain's increased preparations for war, as well as to meet the needs of the U.S. home front and the rapidly expanding American Navy.

The growth was led by Henry J. Kaiser, whose company had been the prime contractor in the construction of two Columbia River dams. In 1941, Kaiser Shipyards

The Kaiser Shipyards were seven major shipbuilding yards located on the United States west coast during World War II. Kaiser ranked 20th among U.S. corporations in the value of wartime production contracts. The shipyards were owned by the Kaise ...

received federal contracts to build Liberty ship

Liberty ships were a class of cargo ship built in the United States during World War II under the Emergency Shipbuilding Program. Though British in concept, the design was adopted by the United States for its simple, low-cost construction. Ma ...

s and aircraft carrier escorts; he chose Portland as one of the sites, and built two shipyards along the Willamette River, and a third in nearby Vancouver

Vancouver ( ) is a major city in western Canada, located in the Lower Mainland region of British Columbia. As the most populous city in the province, the 2021 Canadian census recorded 662,248 people in the city, up from 631,486 in 2016. ...

; the 150,000 workers he recruited to staff these shipyards play a major role in the growth of Portland, which added 160,000 residents during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

.

By war's end, Portland had a population of 359,000, and an additional 100,000 people lived and/or worked in nearby cities such as Vanport, Oregon City

)

, image_skyline = McLoughlin House.jpg

, imagesize =

, image_caption = The McLoughlin House, est. 1845

, image_flag =

, image_seal = Oregon City seal.png

, image_map ...

, and Troutdale.

The war jobs attracted large numbers of African-Americans into the small existing community—the numbers quadrupled. The newcomers became permanent residents, building up black political influence, strengthening civil rights organizations

such as the NAACP calling for antidiscrimination legislation. On the negative side, racial tensions increased, both black and white residential areas deteriorated from overcrowding, and inside the black community there were angry words between "old settlers" and recent arrivals vying for leadership in the black communities.

Postwar

TheVanport Flood

The 1948 Columbia River flood (or Vanport Flood) was a regional flood that occurred in the Pacific Northwest of the United States and Canada. Large portions of the Columbia River watershed where impacted, including the Portland area, Eastern Was ...

of 1948.

The 1940s and 1950s also saw an extensive network of organized crime

Organized crime (or organised crime) is a category of transnational, national, or local groupings of highly centralized enterprises run by criminals to engage in illegal activity, most commonly for profit. While organized crime is generally th ...

, largely dominated by Jim Elkins. The McClellan Commission determined in the late 1950s that Portland not only had a local crime problem, but also a situation that had serious national ramifications. In 1956 ''Oregonian'' reporters determined that corrupt Teamsters

The International Brotherhood of Teamsters (IBT), also known as the Teamsters Union, is a labor union in the United States and Canada. Formed in 1903 by the merger of The Team Drivers International Union and The Teamsters National Union, the ...

officials were plotting to take over the city's vice rackets.

Public transportation in Portland transitioned from private to public ownership in 1969–70, as the private companies found it increasingly difficult to make a profit and were on the verge of bankruptcy. A new regional government agency, the Tri-County Metropolitan Transportation District (Tri-Met), replaced Rose City Transit in 1969 and the "Blue Bus" lines—connecting Portland with its suburbs—in 1970.

Freeway, Displacement, and Urban Renewal

Late 20th century

During the dot-com boom of the mid-to-late 1990s, Portland saw an influx of people in their 20s and 30s, drawn by the promise of a city with abundant nature, urban growth boundaries, cheaper rents, and opportunities to work in thegraphic design

Graphic design is a profession, academic discipline and applied art whose activity consists in projecting visual communications intended to transmit specific messages to social groups, with specific objectives. Graphic design is an interdiscip ...

and Internet

The Internet (or internet) is the global system of interconnected computer networks that uses the Internet protocol suite (TCP/IP) to communicate between networks and devices. It is a '' network of networks'' that consists of private, p ...

industries, as well as for companies like Doc Martens

Dr. Martens, also commonly known as Doc Martens, Docs or DMs, is a German-founded British footwear and clothing brand, headquartered in Wollaston in the Wellingborough district of Northamptonshire, England. Although famous for its footwear, D ...

, Nike

Nike often refers to:

* Nike (mythology), a Greek goddess who personifies victory

* Nike, Inc., a major American producer of athletic shoes, apparel, and sports equipment

Nike may also refer to:

People

* Nike (name), a surname and feminine give ...

, Adidas

Adidas AG (; stylized as adidas since 1949) is a German multinational corporation, founded and headquartered in Herzogenaurach, Bavaria, that designs and manufactures shoes, clothing and accessories. It is the largest sportswear manufacture ...

, and Wieden+Kennedy

Wieden+Kennedy (W+K; earlier styled ''Wieden & Kennedy'') is an American independent global advertising agency best known for its work for Nike. Founded by Dan Wieden and David Kennedy, and headquartered in Portland, Oregon, it is one of the ...

. When this economic bubble

An economic bubble (also called a speculative bubble or a financial bubble) is a period when current asset prices greatly exceed their intrinsic valuation, being the valuation that the underlying long-term fundamentals justify. Bubbles can be c ...

burst, the city was left with a large creative population. Also, when the bubble burst in Seattle

Seattle ( ) is a seaport city on the West Coast of the United States. It is the seat of King County, Washington. With a 2020 population of 737,015, it is the largest city in both the state of Washington and the Pacific Northwest region o ...

and San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish for " Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the fourth most populous in California and 17t ...

, even more artists streamed into Portland, drawn in part by its relatively low cost of living, for a West Coast city. In 2000, the U.S. census indicated there were over 10,000 artists in Portland.

Cultural history

Whilevisual arts

The visual arts are art forms such as painting, drawing, printmaking, sculpture, ceramics, photography, video, filmmaking, design, crafts and architecture. Many artistic disciplines such as performing arts, conceptual art, and textile art ...

had always been important in the Pacific Northwest, the mid-1990s saw a dramatic rise in the number of artists, independent galleries, site-specific shows and public discourse about the arts.Ann Markusen and Amanda Johnson, "Artists’ Centers: Evolution and Impact on Careers, Neighborhoods and Economies," (Project on Regional and Industrial Economics, Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs, University of Minnesota, 2006)abstract

/ref> Several arts

publications

To publish is to make content available to the general public.Berne Conve ...

were founded. The Portland millennial art renaissance has been described, written about and commented on in publications such as ARTnews

''ARTnews'' is an American visual-arts magazine, based in New York City. It covers art from ancient to contemporary times. ARTnews is the oldest and most widely distributed art magazine in the world. It has a readership of 180,000 in 124 countr ...

, Artpapers, Art in America

''Art in America'' is an illustrated monthly, international magazine concentrating on the contemporary art world in the United States, including profiles of artists and genres, updates about art movements, show reviews and event schedules. It is ...

, Modern Painters

''Modern Painters'' (1843–1860) is a five-volume work by the Victorian art critic, John Ruskin, begun when he was 24 years old based on material collected in Switzerland in 1842. Ruskin argues that recent painters emerging from the tradition o ...

and Artforum

''Artforum'' is an international monthly magazine specializing in contemporary art. The magazine is distinguished from other magazines by its unique 10½ x 10½ inch square format, with each cover often devoted to the work of an artist. Notably ...

and discussed on CNN.''Portland?'' by Aaron Brown (2004) http://edition.cnn.com/TRANSCRIPTS/0409/28/asb.00.html The Wall Street Journal

''The Wall Street Journal'' is an American business-focused, international daily newspaper based in New York City, with international editions also available in Chinese and Japanese. The ''Journal'', along with its Asian editions, is published ...

Peter Plagens noted the vibrancy of Portland's alternative art spaces.''Our Next Art Capital, Portland?'' by Peter Plagens (2012) http://www.online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052702303916904577378300036157294.html

See also

* James B. Stephens * James C. Hawthorne *A Day Called 'X'

''The Day Called 'X is a dramatized CBS documentary film set in Portland, Oregon, in which the entire city is evacuated in anticipation of a nuclear air raid, after Soviet bombers had been detected by radar stations to the north; it details the ...

*Columbus Day Storm of 1962

The Columbus Day Storm of 1962 (also known as the Big Blow, and originally, and in Canada as Typhoon Freda) was a Pacific Northwest windstorm that struck the West Coast of Canada and the Pacific Northwest coast of the United States on October 12, ...

*Mount Hood Freeway

The Mount Hood Freeway is a partially constructed but never to be completed freeway alignment of U.S. Route 26 and Interstate 80N (now Interstate 84), which would have run through southeast Portland, Oregon. Related projects would have cont ...

* Mayors of Portland

* Timeline of Portland, Oregon

* History of the Japanese in Portland, Oregon

References

Further reading

*full text online

* Abbott, Carl. ''Portland in Three Centuries: The Place and the People'' (Oregon State University Press; 2011) 192 pages; scholarly histor

online

* Abbott, Carl. ''Portland : gateway to the Northwest'' (1985

online

* In Three Volumes

Volume 1

Volume 2

Volume 3

* Johnston, Robert D. ''The Radical Middle Class: Populist Democracy and the Question of Capitalism in Progressive Era Portland, Oregon'' (2003) * * Leeson, Fred. ''Rose City Justice: A Legal History of Portland, Oregon'' (Portland: Oregon Historical Society Press, 1998) * *

online full text

also se

online review

* * MacColl, E. Kimbark, and Harry H. Stein. "The Economic Power of Portland's Early Merchants, 1851-1861." ''Oregon Historical Quarterly'' 89.2 (1988): 117-156. * Elma MacGibbons reminiscences of her travels in the United States starting in 1898, which were mainly in Oregon and Washington. Includes chapter "Portland, the western hub." * Merriam, Paul Gilman. "Portland, Oregon, 1840–1890: A Social and Economic History". Ph.D. dissertation. University of Oregon, Department of History, 1971. * Mullins, William H. ''The Depression and the Urban West Coast, 1929-1933: Los Angeles, San Francisco, Seattle, and Portland'' (2000) * * * Scott, H. W. ed. ''History of Portland, Oregon, with Illustrations and Biographical Sketches of Prominent Citizens and Pioneers'' (D. Mason & Company, 1890) 792p

full text online

External links

*Postcards and snaps from the past aPdxHistory.com

at Portland City Auditor's Office

Wartime Portland

at Oregon Historical Society *Portland page a

Oregon History Project

(Oregon Historical Society)

at ''Willamette Week''

Transportation history

Portland Bureau of Transportation

A pictorial history of the Portland Waterfront

* {{Oregon Brief History Willamette Valley

Portland, Oregon

Portland (, ) is a port city in the Pacific Northwest and the largest city in the U.S. state of Oregon. Situated at the confluence of the Willamette and Columbia rivers, Portland is the county seat of Multnomah County, the most populous ...