History of Penkridge on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The village of Penkridge in its current location dates back at least to the early

The village of Penkridge in its current location dates back at least to the early

The church was the most notable feature of Penkridge from late Anglo-Saxon times. By the 13th century, it had reached a distinctive form.

:* It was a chapel royal - a place set aside by the monarchs for their own use. This made it independent of the local

The church was the most notable feature of Penkridge from late Anglo-Saxon times. By the 13th century, it had reached a distinctive form.

:* It was a chapel royal - a place set aside by the monarchs for their own use. This made it independent of the local

File:Penkridge St Michael - West window exterior.jpg, Exterior view of the western end of the church, showing large Perpendicular window.

File:Penkridge St Michael - West tower 01.jpg, View of the tower, modified in late Perpendicular style in the 16th century.

File:Penkridge St Michael - East window exterior.jpg, East window. Perpendicular in style, it formerly contained much more tracery.

File:Penkridge St Michael - Chancel gates and organ.jpg, The

Penkridge church several times had to make a stand to preserve its independence against both the diocese of Coventry and Lichfield and the wider Province of Canterbury. In 1259 the Archdeacon of Stafford tried to carry out a canonical visitation, a tour of inspection, on behalf of the diocese. Henry III wrote personally to him, ordering him to desist. The

Economic and social life in medieval Penkridge were enacted within the manor, the basic territorial unit of feudal society, which regulated the economic and social relationships of its members and enforced the law on them. The manor was sometimes co-extensive with the village, but not always. Penkridge was initially a royal manor, a situation that still had real meaning in 1086, when Domesday found that the king had land and a mill at Penkridge being directly worked for him by a small team. The situation changed, probably in the 12th century, when one of the kings gave it as a

Economic and social life in medieval Penkridge were enacted within the manor, the basic territorial unit of feudal society, which regulated the economic and social relationships of its members and enforced the law on them. The manor was sometimes co-extensive with the village, but not always. Penkridge was initially a royal manor, a situation that still had real meaning in 1086, when Domesday found that the king had land and a mill at Penkridge being directly worked for him by a small team. The situation changed, probably in the 12th century, when one of the kings gave it as a  :* Congreve, which was originally a part or "member" of Penkridge manor. As late as the 19th century, the lords of Congreve paid a tiny rent, £1 1s., to the lords of Penkridge. In the 13th century the Teveray family became established at Congreve, although not without protracted disputes, and by 1302 it was being described as a manor. In the 14th century, the Dumbleton family acquired all the rights from the disputing parties and were soon being addressed as ''de Congreve''. The same Congreve family held the manor until modern times, residing at Congreve Manor House.

:* Congreve Prebendal Manor, which belonged to St. Michael's College, and was centred on Congreve House, about 250m. from the Manor House.

:* Drayton, also originally a part of Penkridge manor. The overlordship was held by the de Staffords from the 12th century and the Barons Stafford claimed it for centuries after. However, Hervey Bagot, who had married Millicent de Stafford, got into protracted and complex legal difficulties over the tenure of Drayton. These were ultimately resolved by all parties agreeing to give the manor to the

:* Congreve, which was originally a part or "member" of Penkridge manor. As late as the 19th century, the lords of Congreve paid a tiny rent, £1 1s., to the lords of Penkridge. In the 13th century the Teveray family became established at Congreve, although not without protracted disputes, and by 1302 it was being described as a manor. In the 14th century, the Dumbleton family acquired all the rights from the disputing parties and were soon being addressed as ''de Congreve''. The same Congreve family held the manor until modern times, residing at Congreve Manor House.

:* Congreve Prebendal Manor, which belonged to St. Michael's College, and was centred on Congreve House, about 250m. from the Manor House.

:* Drayton, also originally a part of Penkridge manor. The overlordship was held by the de Staffords from the 12th century and the Barons Stafford claimed it for centuries after. However, Hervey Bagot, who had married Millicent de Stafford, got into protracted and complex legal difficulties over the tenure of Drayton. These were ultimately resolved by all parties agreeing to give the manor to the  :* Whiston, which came under the overlordship of Burton Abbey from 1004. One of the tenants, a John de Whiston, fought as a

:* Whiston, which came under the overlordship of Burton Abbey from 1004. One of the tenants, a John de Whiston, fought as a

From the 14th century, the feudal system in Penkridge, as elsewhere, began to break down. Edward I's law

From the 14th century, the feudal system in Penkridge, as elsewhere, began to break down. Edward I's law

File:Penkridge St Michael - Edward Littleton 1558.jpg, Tomb of Sir

Shortly before his acquisition of the College lands, Dudley had also come by the manor of Penkridge. This was the result of a deal made by

Shortly before his acquisition of the College lands, Dudley had also come by the manor of Penkridge. This was the result of a deal made by

Greville's focus of interest lay in Warwickshire, around

Greville's focus of interest lay in Warwickshire, around  Despite apparent Puritan sympathies, the Littletons found themselves on the Royalist side. Sir Edward Littleton had been made a baronet by Charles I on 28 June 1627, albeit in exchange for a large sum of money acquired through marriage to Hester Courten, daughter of Sir

Despite apparent Puritan sympathies, the Littletons found themselves on the Royalist side. Sir Edward Littleton had been made a baronet by Charles I on 28 June 1627, albeit in exchange for a large sum of money acquired through marriage to Hester Courten, daughter of Sir

Throughout the 16th and 17th centuries

Throughout the 16th and 17th centuries

The 18th and 19th centuries brought vast changes to agriculture and industry, both locally and nationally. After prospering throughout the

The 18th and 19th centuries brought vast changes to agriculture and industry, both locally and nationally. After prospering throughout the

VCH: Staffordshire: Volume 5:16.s.1.

/ref> Penkridge has remained a substantial commercial and shopping centre. The major supermarket chains have not been allowed to open stores in the town and its only large store is a Co-operative supermarket. Independent shops, cafés, inns and services occupy the area between the old market place to the east and Stone Cross on the A449 to the west. The area between Pinfold Lane and the river, long the site of livestock sales, has emerged as a new market place, attracting large numbers of visitors to Penkridge on market days.

St Michael and All Angels church, Penkridge

* {{coord, 52.723, N, 2.113, W, display=title Penkridge Penkridge, History of

Penkridge

Penkridge ( ) is a village and civil parish in South Staffordshire District in Staffordshire, England. It is to the south of Stafford, north of Wolverhampton, west of Cannock and east of Telford. The nearby town of Brewood is also not far awa ...

is a village and parish

A parish is a territorial entity in many Christian denominations, constituting a division within a diocese. A parish is under the pastoral care and clerical jurisdiction of a priest, often termed a parish priest, who might be assisted by one o ...

in Staffordshire with a history stretching back to the Anglo-Saxon period. A religious as well as a commercial centre, it was originally centred on the Collegiate Church In Christianity, a collegiate church is a church where the daily office of worship is maintained by a college of canons: a non-monastic or "secular" community of clergy, organised as a self-governing corporate body, which may be presided over by ...

of St. Michael and All Angels, a chapel royal and royal peculiar

A royal peculiar is a Church of England parish or church exempt from the jurisdiction of the diocese and the province in which it lies, and subject to the direct jurisdiction of the monarch, or in Cornwall by the duke.

Definition

The church par ...

that maintained its independence until the Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...

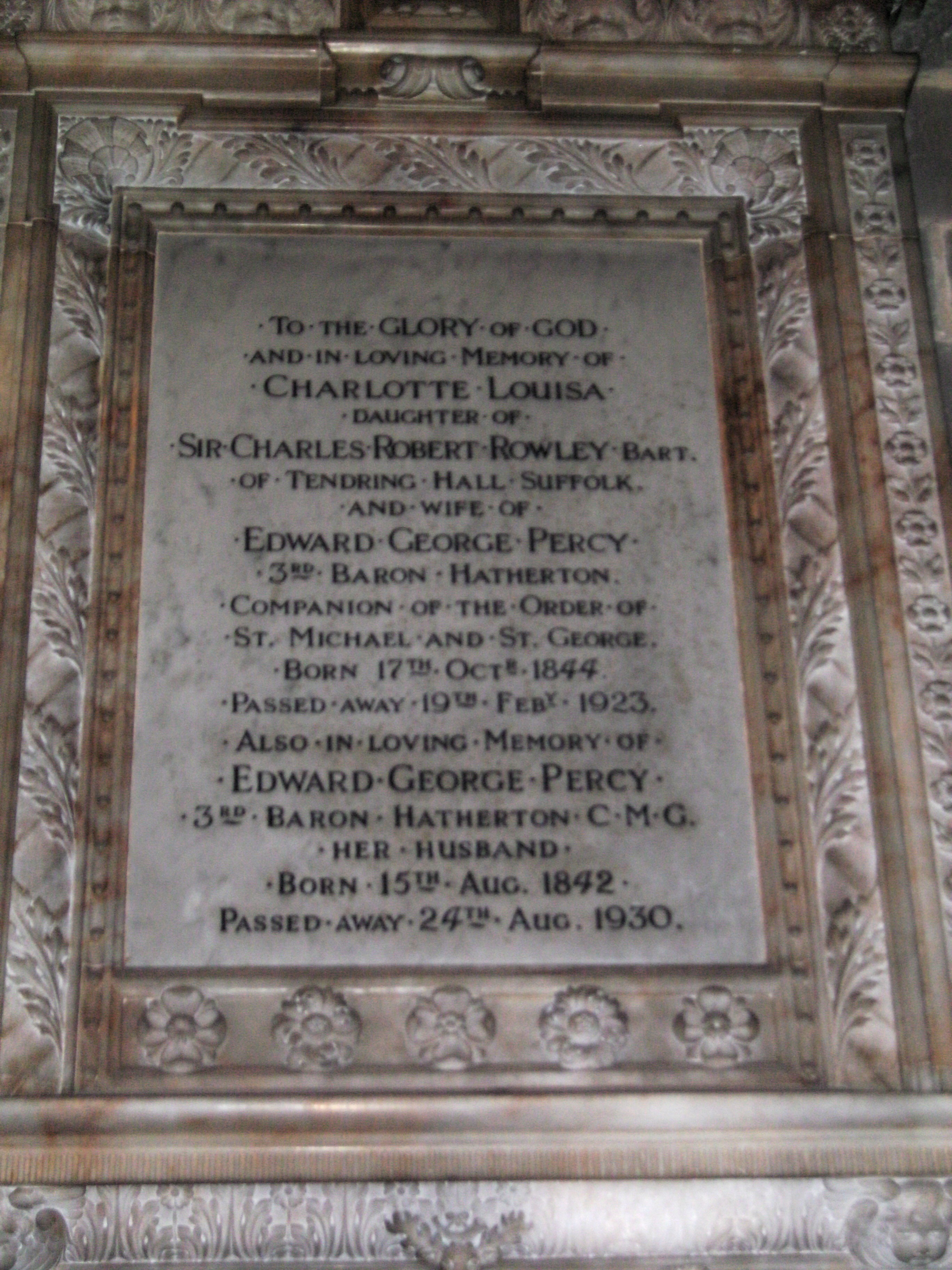

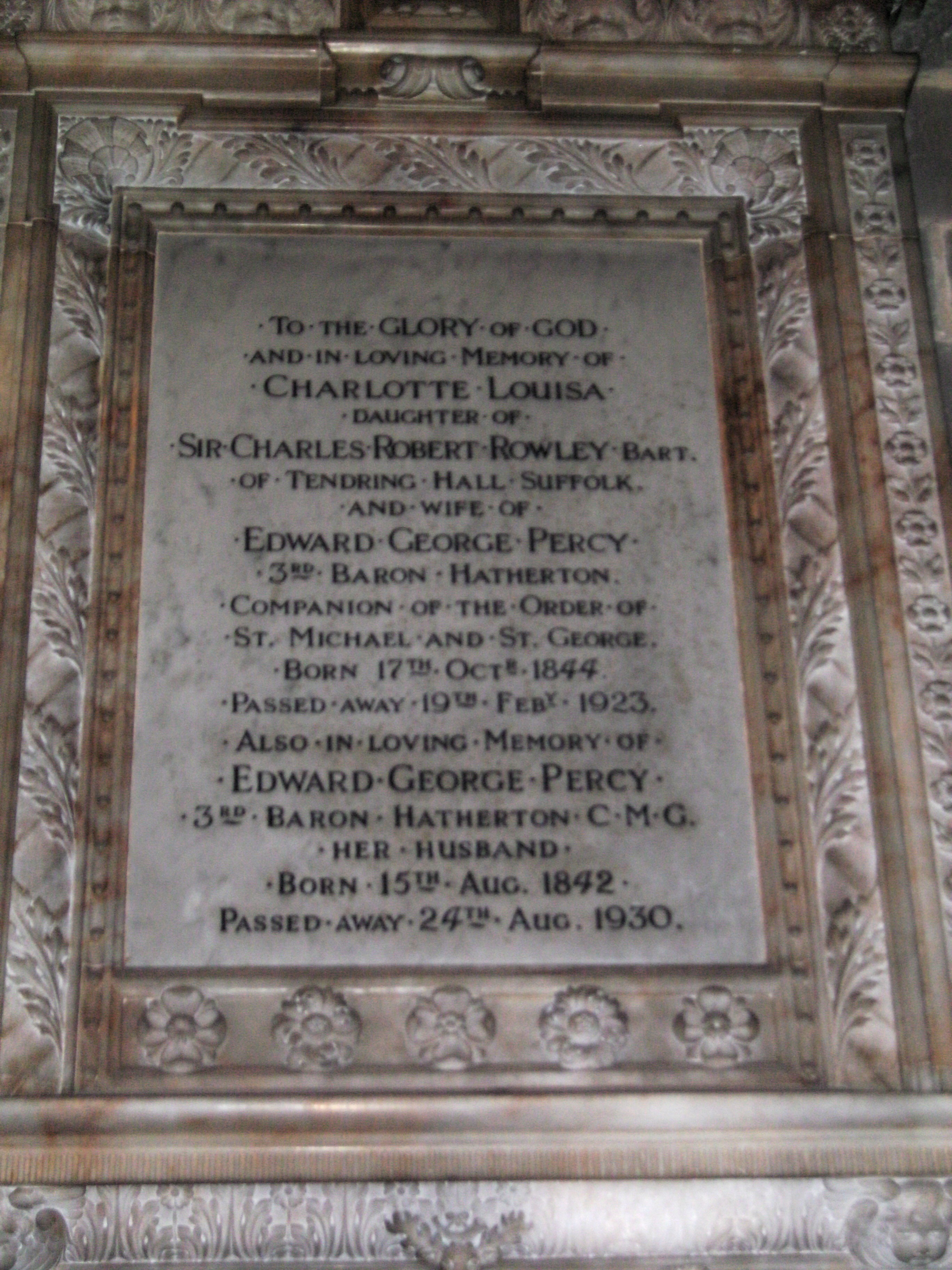

. Mentioned in Domesday, Penkridge underwent a period of growth from the 13th century, as the Forest Law was loosened, and evolved into a patchwork of manors of greatly varying size and importance, heavily dependent on agriculture. From the 16th century it was increasingly dominated by a single landed gentry family, the Littletons, who ultimately attained the Peerage of the United Kingdom as the Barons Hatherton, and who helped modernise its agriculture and education system. The Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going f ...

inaugurated a steady improvement in transport and communications that helped shape the modern village. In the second half of the 20th century, Penkridge grew rapidly, evolving into a mainly residential area

A residential area is a land used in which housing predominates, as opposed to industrial and commercial areas.

Housing may vary significantly between, and through, residential areas. These include single-family housing, multi-family resi ...

, while retaining its commercial centre, its links with the countryside and its fine church.

Early settlement

Early human occupation of the immediate area around Penkridge has been confirmed by the presence of a Bronze orIron Age

The Iron Age is the final epoch of the three-age division of the prehistory and protohistory of humanity. It was preceded by the Stone Age ( Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic) and the Bronze Age ( Chalcolithic). The concept has been mostl ...

barrow at nearby Rowley Hill. A significant settlement in this vicinity has existed since pre-Roman times, with its original location being at the intersection of the River Penk

The River Penk is a small river flowing through Staffordshire, England. Its course is mainly within South Staffordshire, and it drains most of the northern part of that district, together with some adjoining areas of Cannock Chase, Stafford, Wo ...

and what became the Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lette ...

military road known as Watling Street

Watling Street is a historic route in England that crosses the River Thames at London and which was used in Classical Antiquity, Late Antiquity, and throughout the Middle Ages. It was used by the ancient Britons and paved as one of the main ...

(today's A5 trunk road). This would place it between Water Eaton and Gailey, about SSW of the modern town.

Anglo-Saxon origins

The village of Penkridge in its current location dates back at least to the early

The village of Penkridge in its current location dates back at least to the early Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

, when the area was part of Mercia

la, Merciorum regnum

, conventional_long_name=Kingdom of Mercia

, common_name=Mercia

, status=Kingdom

, status_text=Independent kingdom (527–879) Client state of Wessex ()

, life_span=527–918

, era= Heptarchy

, event_start=

, date_start=

, ...

, and it held an important place in local society, trade, and religious observance.

The first clear reference to the settlement of ''Pencric'' comes from the reign of Edgar the Peaceful

Edgar ( ang, Ēadgār ; 8 July 975), known as the Peaceful or the Peaceable, was King of the English from 959 until his death in 975. The younger son of King Edmund I and Ælfgifu of Shaftesbury, he came to the throne as a teenager followin ...

(959-975), who issued a royal charter

A royal charter is a formal grant issued by a monarch under royal prerogative as letters patent. Historically, they have been used to promulgate public laws, the most famous example being the English Magna Carta (great charter) of 1215, but s ...

from it in 958, describing it as a "famous place". Around 1000, Wulfgeat, a Shropshire landowner, left bullocks to the church at Penkridge, which means that the church must date from at least the 10th century. In the 16th century, John Alen

John Alen (1476 – 28 July 1534) was an English priest and canon lawyer, whose later years were spent in Ireland. He held office as Archbishop of Dublin and Lord Chancellor of Ireland, and was a member of the Privy Council of Ireland. In the lat ...

, dean of Penkridge and Archbishop of Dublin, claimed that the founder of the collegiate church of St. Michael at Penkridge was King Eadred

Eadred (c. 923 – 23 November 955) was King of the English from 26 May 946 until his death. He was the younger son of Edward the Elder and his third wife Eadgifu, and a grandson of Alfred the Great. His elder brother, Edmund, was killed try ...

(946-55), Edgar's uncle, which seems plausible. The origins of the settlement may go back much earlier in the Anglo-Saxon period, but the known dates suggest that it achieved considerable importance in the mid-10th century and that the village's significance was in large part dependent on its important church.

A local legend claims that King Edgar made Penkridge his capital for three years whilst he was reconquering the Danelaw

The Danelaw (, also known as the Danelagh; ang, Dena lagu; da, Danelagen) was the part of England in which the laws of the Danes held sway and dominated those of the Anglo-Saxons. The Danelaw contrasts with the West Saxon law and the Mercian ...

. However most historical sources see the reign of Edgar as an uneventful one, as his cognomen suggests, and there is no record of any internal strife between English and Danes during his reign, making this claim doubtful. At Domesday, more than a century later, Penkridge was still a royal manor, and St. Michael's was a chapel royal. This makes it likely that Edgar stayed here simply because it was one of his homes: medieval rulers were itinerant, moving with their retinue to consume their resources ''in situ'', rather than having them transported to a capital.

In about 1086, Domesday not only recorded the then situation at Penkridge, but gave considerable insight into changes and continuities since the Anglo-Saxon period. Penkridge was still held by the king, William the Conqueror

William I; ang, WillelmI (Bates ''William the Conqueror'' p. 33– 9 September 1087), usually known as William the Conqueror and sometimes William the Bastard, was the first House of Normandy, Norman List of English monarchs#House of Norman ...

, directly, not simply as overlord of another magnate - just as Edward the Confessor held it before the Norman Conquest

The Norman Conquest (or the Conquest) was the 11th-century invasion and occupation of England by an army made up of thousands of Norman, Breton, Flemish, and French troops, all led by the Duke of Normandy, later styled William the Con ...

. The king had a mill and a substantial area of woodland. The numbers working on the king's land are, however, very small: just two slaves, two villeins and two smallholders, although the land at Penkridge was worth 40 shillings annually. Then there were the subsidiary parts of the manor: Wolgarston, Drayton, Congreve, Dunston, Cowley and Beffcote, which had almost 30 workers and had increased in value from 65s. to 100s. since the Conquest – unusual in the Midlands or North at that time.

At Penkridge itself a substantial part of the agricultural land was held from the king by nine clerics, who had a hide of land, worked by six slaves and seven villein

A villein, otherwise known as ''cottar'' or '' crofter'', is a serf tied to the land in the feudal system. Villeins had more rights and social status than those in slavery, but were under a number of legal restrictions which differentiated them ...

s. These clerics had a further 2¾ hides at Gnosall

Gnosall is a village and civil parish in the Borough of Stafford, Staffordshire, England, with a population of 4,736 across 2,048 households (2011 census). It lies on the A518, approximately halfway between the towns of Newport (in Shropshir ...

, to the north, with twelve workers. Both these holdings had risen greatly in value since the Conquest. In Henry I's time, there was a dispute between the Abbey of Saint-Remi

An abbey is a type of monastery used by members of a religious order under the governance of an abbot or abbess. Abbeys provide a complex of buildings and land for religious activities, work, and housing of Christian monks and nuns.

The conc ...

or Saint-Rémy at Reims in Northern France, which claimed the church at Lapley, next to its daughter house, Lapley Priory, and a royal chaplain. It is believed the clerk in question was a canon of Penkridge, trying to vindicate an ancient claim to Lapley. A 13th-century source confirms that Lapley once belonged to Penkridge. The court found in favour of Saint-Rémy and Lapley was confirmed as a small independent parish in the advowson

Advowson () or patronage is the right in English law of a patron (avowee) to present to the diocesan bishop (or in some cases the ordinary if not the same person) a nominee for appointment to a vacant ecclesiastical benefice or church living ...

of Saint-Rémy. However, this was not a result of the Norman Conquest directly, but was intended as confirmation of a grant to the French abbey by Ælfgar, Earl of Mercia

Ælfgar (died ) was the son of Leofric, Earl of Mercia, by his famous mother Godgifu (Lady Godiva). He succeeded to his father's title and responsibilities on the latter's death in 1057. He gained the additional title of Earl of East Anglia, but a ...

, in the closing years of the Anglo-Saxon monarchy.

Penkridge seems to have passed through the Conquest not only unscathed but enhanced in wealth and status: a royal manor, with a sizeable royal demesne and a substantial church, staffed by a community of clerics. However, it was clearly not, in the modern sense, a village. Penkridge itself would have been a small village on the southern bank of the River Penk

The River Penk is a small river flowing through Staffordshire, England. Its course is mainly within South Staffordshire, and it drains most of the northern part of that district, together with some adjoining areas of Cannock Chase, Stafford, Wo ...

, with the homes of the laity grouped to the east of the church, along the Stafford-Worcester road, and with a scattering of hamlets in the surrounding area.

Medieval Penkridge

St. Michael's Collegiate Church

The church was the most notable feature of Penkridge from late Anglo-Saxon times. By the 13th century, it had reached a distinctive form.

:* It was a chapel royal - a place set aside by the monarchs for their own use. This made it independent of the local

The church was the most notable feature of Penkridge from late Anglo-Saxon times. By the 13th century, it had reached a distinctive form.

:* It was a chapel royal - a place set aside by the monarchs for their own use. This made it independent of the local Bishop of Lichfield

The Bishop of Lichfield is the ordinary of the Church of England Diocese of Lichfield in the Province of Canterbury. The diocese covers 4,516 km2 (1,744 sq. mi.) of the counties of Powys, Staffordshire, Shropshire, Warwickshire and Wes ...

- an institution called a Royal Peculiar

A royal peculiar is a Church of England parish or church exempt from the jurisdiction of the diocese and the province in which it lies, and subject to the direct jurisdiction of the monarch, or in Cornwall by the duke.

Definition

The church par ...

.

:* It was a collegiate church In Christianity, a collegiate church is a church where the daily office of worship is maintained by a college of canons: a non-monastic or "secular" community of clergy, organised as a self-governing corporate body, which may be presided over by ...

, staffed by a college

A college (Latin: ''collegium'') is an educational institution or a constituent part of one. A college may be a degree-awarding tertiary educational institution, a part of a collegiate or federal university, an institution offerin ...

of priests, who formed its chapter.

:* It was organised like a cathedral chapter.

:* It was headed by the Archbishop of Dublin.

The college was already a well-established institution by the Norman Conquest. The nine clerics mentioned in Domesday were far too many for a small village and served a wide area of Staffordshire from their base in Penkridge. The priests who belonged the college were often called canons, the usual term for permanent staff attached to a cathedral or large church. As a body, they were also known as a chapter. The chapter survived the Norman Conquest in much the same form as in Anglo-Saxon times. Throughout its existence, it was made up of secular clergy, not monks.

In all this, St. Michael's, Penridge, was similar to its nearby namesake, St. Michael's Collegiate Church at Tettenhall

Tettenhall is an historic village within the City of Wolverhampton, England. Tettenhall became part of Wolverhampton in 1966, along with Bilston, Wednesfield and parts of Willenhall, Coseley and Sedgley.

History

Tettenhall's name derives fr ...

, to St. Peter's Collegiate Church, Wolverhampton

St Peter's Collegiate Church is located in central Wolverhampton, England. For many centuries it was a chapel royal and from 1480 a royal peculiar, independent of the Diocese of Lichfield and even the Province of Canterbury. The collegiate chu ...

, and to St Mary's College at Stafford. All were chapels royal, similarly organised and zealously guarding their independence. They formed an indigestible block within the borders of the diocese of Lichfield

The Diocese of Lichfield is a Church of England diocese in the Province of Canterbury, England. The bishop's seat is located in the Cathedral Church of the Blessed Virgin Mary and Saint Chad in the city of Lichfield. The diocese covers of seve ...

, whose bishop was the ordinary - the officer responsible for carrying out the laws of the Church and maintaining proper order in the region. Sometimes it seems that they acted in concert, forming a united front against determined bishops. This was in stark contrast to the relative malleability of the small, local parish churches.

The church and college lost their independence only during the Anarchy of King Stephen's reign. Keen to consolidate the support of the church for his coup against Empress Matilda, Stephen gave the churches of Penkridge and Stafford to Roger de Clinton

Roger de Clinton (died 1148) was a medieval Bishop of Coventry and Lichfield. He was responsible for organising a new grid street plan for the town of Lichfield in the 12th century which survives to this day.

Life

Clinton was the nephew of Geo ...

, bishop of Coventry and Lichfield. At some time after the first Plantagenet

The House of Plantagenet () was a royal house which originated from the lands of Anjou in France. The family held the English throne from 1154 (with the accession of Henry II at the end of the Anarchy) to 1485, when Richard III died in ...

ruler, Henry II, took over in 1154, Penkridge escaped episcopal control. Certainly by 1180 it was again the possession of the king. In the meantime, it had been reorganised to a template derived from the chapter of Lichfield Cathedral

Lichfield Cathedral is an Anglican cathedral in Lichfield, Staffordshire, England, one of only three cathedrals in the United Kingdom with three spires (together with Truro Cathedral and St Mary's Cathedral in Edinburgh), and the only medie ...

, which was established on the same lines in the mid-12th century. Like a cathedral, the college was now headed by a dean

Dean may refer to:

People

* Dean (given name)

* Dean (surname), a surname of Anglo-Saxon English origin

* Dean (South Korean singer), a stage name for singer Kwon Hyuk

* Dean Delannoit, a Belgian singer most known by the mononym Dean

Titles

* ...

. The first dean was called Robert but little else is known of him. The canons were now prebendaries

A prebendary is a member of the Roman Catholic or Anglican clergy, a form of canon with a role in the administration of a cathedral or collegiate church. When attending services, prebendaries sit in particular seats, usually at the back of the ...

, meaning that each was supported by revenue from a fixed group of estates and rights that constituted his prebend, and which was technically attached to his choir stall

A choir, also sometimes called quire, is the area of a church or cathedral that provides seating for the clergy and church choir. It is in the western part of the chancel, between the nave and the sanctuary, which houses the altar and Church tab ...

, not to him personally. There were prebends of Coppenhall, Stretton, Shareshill, Dunston, Penkridge, Congreve, and Longridge. It is possible that the prebend of Penkridge absorbed the lands held by the nine priests of the Domesday survey. In addition, two prebends were later created for the two chantries

A chantry is an ecclesiastical term that may have either of two related meanings:

# a chantry service, a Christian liturgy of prayers for the dead, which historically was an obiit, or

# a chantry chapel, a building on private land, or an area i ...

. For many decades Cannock

Cannock () is a town in the Cannock Chase district in the county of Staffordshire, England. It had a population of 29,018. Cannock is not far from the nearby towns of Walsall, Burntwood, Stafford and Telford. The cities of Lichfield and Wolv ...

was also a prebend of Penkridge, although it was strongly disputed by the chapter of Lichfield, and seems to have slipped out of Penkridge's grasp permanently in the mid-14th century.

In 1215, the year of Magna Carta, King John conferred the advowson

Advowson () or patronage is the right in English law of a patron (avowee) to present to the diocesan bishop (or in some cases the ordinary if not the same person) a nominee for appointment to a vacant ecclesiastical benefice or church living ...

of the deanery - or right to appoint a dean - on Henry de Loundres

Henry de Loundres (died 1228) was an Anglo-Norman churchman who was Archbishop of Dublin, from 1213 to 1228. He was an influential figure in the reign of John of England, an administrator and loyalist to the king, and is mentioned in the text o ...

, or Henry of London, a devoted servant of the Crown who had once been Archdeacon of Stafford, and had recently been consecrated Archbishop of Dublin. John was under enormous pressure from the barons

Baron is a rank of nobility or title of honour, often hereditary, in various European countries, either current or historical. The female equivalent is baroness. Typically, the title denotes an aristocrat who ranks higher than a lord or knigh ...

, so he was keen to consolidate his supporters. The Hose or Hussey family had been granted the manor of Penkridge some time previously, but in 1215 Hugh Hose, the putative successor to the manor, was a ward

Ward may refer to:

Division or unit

* Hospital ward, a hospital division, floor, or room set aside for a particular class or group of patients, for example the psychiatric ward

* Prison ward, a division of a penal institution such as a pris ...

of King John. John induced him to convey the manor to the archbishop, along with Congreve, Wolgarston, Cowley, Beffcote, and Little Onn (in Church Eaton

Church Eaton is a village and Civil parishes in England, civil parish in Staffordshire some southwest of Stafford, northwest of Penkridge and from the county boundary with Shropshire. It is in rolling dairy farming countryside. The hamlet of W ...

), all of which were considered "members" or constituent parts of Penkridge manor.

The archbishop used the opportunity to enrich both his family and his diocese. He divided the manor permanently into two unequal parts. Two-thirds he gave to his nephew, Andrew de Blund. The remaining third Henry gave to the church: it became known as the ''deanery manor''. The de Blund family, later rendered as Blount, held the manor of Penkridge for about 140 years, finally selling it to other lay lords. Along with the prebends and various other holdings, the Deanery Manor was to finance the college of St. Michael for more than 300 years. When the newly enriched deanery fell vacant in 1226, Henry seized the opportunity to appoint himself to the post. Although John's son, Henry III challenged this by appointing a dean of his own, the relevant charter was recovered and the principle established that the deanery of Penkridge was to be held by the archbishops of Dublin, as it was from this point until the Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...

. This was an arrangement unique to Penkridge.

wrought iron

Wrought iron is an iron alloy with a very low carbon content (less than 0.08%) in contrast to that of cast iron (2.1% to 4%). It is a semi-fused mass of iron with fibrous slag inclusions (up to 2% by weight), which give it a wood-like "grain" ...

chancel gates of Dutch origin, dated 1778. The organ, formerly in the tower arch, was moved to present position in 1881.

File:Penkridge St Michael - Lavabo 01.jpg, Lavabo

A lavabo is a device used to provide water for the washing of hands. It consists normally of a ewer or container of some kind to pour water, and a bowl to catch the water as it falls off the hands. In ecclesiastical usage it refers to all of: the b ...

in wall of south chancel aisle

File:Penkridge St Michael - Pulpit 1890 01.jpg, Stone pulpit, 1890, part of a substantial restoration and refurbishment which began in 1881.

File:Penkridge St Michael - Richard Littleton and Alice Wynnesbury tomb alcove.jpg, The early-16th-century tomb alcove of Richard Littleton and Alice Wynnesbury in the south nave aisle, now used for votive candle

A votive candle or prayer candle is a small candle, typically white or beeswax yellow, intended to be burnt as a votive offering in an act of Christian prayer, especially within the Anglican, Lutheran, and Roman Catholic Christian denominations, ...

s. Originally this part of the church was a Littleton family chapel.

Second Council of Lyons

:''The First Council of Lyon, the Thirteenth Ecumenical Council, took place in 1245.''

The Second Council of Lyon was the fourteenth ecumenical council of the Roman Catholic Church, convoked on 31 March 1272 and convened in Lyon, Kingdom of Arl ...

in 1274 denounced a number of abuses for which the prebendaries of the chapels royal were notorious, including non-residence and pluralism. In 1280 the Archbishop of Canterbury, John Peckham

John Peckham (c. 1230 – 8 December 1292) was Archbishop of Canterbury in the years 1279–1292. He was a native of Sussex who was educated at Lewes Priory and became a Friar Minor about 1250. He studied at the University of Paris under ...

, fired with righteous indignation by the council's strictures, tried to carry out a visitation of all the royal chapels that lay within the Coventry and Lichfield diocese. The Penkridge College denied him access to the church, as did those of Wolverhampton, Tettenhall and Stafford, although the latter had to be ordered to resist by a letter from the king, Edward I. The canons of Penkridge appealed to the Pope

The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

, while Peckham pronounced excommunication

Excommunication is an institutional act of religious censure used to end or at least regulate the communion of a member of a congregation with other members of the religious institution who are in normal communion with each other. The purpose ...

upon them. However, he took care to exclude from his sentence John de Derlington

John de Derlington (John of Darlington) (died 1284) was an English Dominican, Archbishop of Dublin and theologian.

Life

Derlington became a Dominican friar, and it has been inferred that he studied at Paris at the Dominican priory of St Jacques ...

, dean of Penkridge and Archbishop of Dublin, and thus his peer. After more than a year of threats and negotiations, pressure from the king compelled Peckham to drop the issue quietly. There were similar wrangles throughout the 14th century about whether the pope

The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

could appoint canons to prebends at the church. After lengthy and complex manoeuvres, the Crown emerged victorious around 1380, under Richard II, who was able to profit from the schism in the Papacy. The only major lapse came in 1401, when Henry IV, having seized the throne from Richard, was heavily dependent on the support Thomas Arundel

Thomas Arundel (1353 – 19 February 1414) was an English clergyman who served as Lord Chancellor and Archbishop of York during the reign of Richard II, as well as Archbishop of Canterbury in 1397 and from 1399 until his death, an outspoken op ...

, then Archbishop of Canterbury. Arundel used the opportunity to force through a visitation of all the chapels royal in Staffordshire, Penkridge included. Every member of the chapter or deputy was subjected to secret interrogation by two of Arundel's commissioners, and some parishioners were also brought in for questioning, although there were no great consequences for the college.

Once the deanery became fixed on the archbishops of Dublin, the deans were almost always absentees. It seems that most of the canons too were usually absent. This was not unusual in the collegiate churches: the record at Wolverhampton was much worse. There was an inevitable tension between the status of St. Michael's as a chapel royal and its role as a village church. The primary use to which kings put their chapels was as chantries

A chantry is an ecclesiastical term that may have either of two related meanings:

# a chantry service, a Christian liturgy of prayers for the dead, which historically was an obiit, or

# a chantry chapel, a building on private land, or an area i ...

- institutions in which daily prayers and masses were said for the souls of the monarchs and royal family. This would have been the case from the foundation of the church, but by the mid-14th century there were two priests specifically responsible for this function, one for the Chantry of the King, the other for the Chantry of the Virgin Mary

Mary; arc, ܡܪܝܡ, translit=Mariam; ar, مريم, translit=Maryam; grc, Μαρία, translit=María; la, Maria; cop, Ⲙⲁⲣⲓⲁ, translit=Maria was a first-century Jewish woman of Nazareth, the wife of Joseph and the mother of ...

. This focus on the dead was only one issue distancing the church from the concerns of the local community. Essentially it was a national rather than a local institution. Its primary purpose was to serve the monarchy and one of the ways it did this was by providing an avenue for preferment. Appointment to the chapter of a wealthy cathedral or chapel was a means of enriching key royal ministers or supporters, so such appointments were not made with the needs of the community in mind, and they were often held in combination with many similar posts. The regular worship was conducted by vicars and other priests, usually paid by the prebendaries or from special funds set up for the purpose. Occasionally abuses and corruption surfaced. Royal inquisitions in 1261 and 1321 found that those canons who were resident tended to make free with the property of the college, at the expense of the absentees, and the 1321 inquiry also implicated the chantry priests in wasting resources. By the late Middle Ages, the expectations of ordinary people were beginning to rise and there was a demand for more participation in worship by the laity. Consequently, by the 16th century, the people of Penkridge were paying for their own morrow-mass priest, who ensured there was a daily mass for the people to attend.

In 1837, the church was separated from its vicarage by the building of the Grand Junction Railway

The Grand Junction Railway (GJR) was an early railway company in the United Kingdom, which existed between 1833 and 1846 when it was amalgamated with other railways to form the London and North Western Railway. The line built by the company w ...

; a foot tunnel under the line was provided to allow the curate to move between the two, and the vicarage, "a house of considerable size, with an Italian roof", was expanded and improved at the railway company's expense, in compensation.

Magnates and manors

Economic and social life in medieval Penkridge were enacted within the manor, the basic territorial unit of feudal society, which regulated the economic and social relationships of its members and enforced the law on them. The manor was sometimes co-extensive with the village, but not always. Penkridge was initially a royal manor, a situation that still had real meaning in 1086, when Domesday found that the king had land and a mill at Penkridge being directly worked for him by a small team. The situation changed, probably in the 12th century, when one of the kings gave it as a

Economic and social life in medieval Penkridge were enacted within the manor, the basic territorial unit of feudal society, which regulated the economic and social relationships of its members and enforced the law on them. The manor was sometimes co-extensive with the village, but not always. Penkridge was initially a royal manor, a situation that still had real meaning in 1086, when Domesday found that the king had land and a mill at Penkridge being directly worked for him by a small team. The situation changed, probably in the 12th century, when one of the kings gave it as a fief

A fief (; la, feudum) was a central element in medieval contracts based on feudal law. It consisted of a form of property holding or other rights granted by an overlord to a vassal, who held it in fealty or "in fee" in return for a form ...

to the Hose or Hussey family, paving the way for its subsequent grant to Archbishop Henry de Loundres, who divided it into lay and deanery manors for his family and ecclesiastical successors respectively. This did not go unchallenged, and the Husseys raised claims to Penkridge occasionally until the 16th century - a lingering dispute typical of feudal land tenure - although their actual possessions shrank to a couple of small holdings at Wolgarston. Penkridge manor and the Deanery Manor were by no means the only manors within Penkridge parish. In fact, there were many, of various sizes and tenures. A list of the different medieval manors and estates would include:

:* Penkridge Manor. This passed through the Blund or Blount family until, in 1363, John Blount conveyed it to John de Beverley. This sale was contested by John's mother, Joyce, who claimed a third back as part of her dowry

A dowry is a payment, such as property or money, paid by the bride's family to the groom or his family at the time of marriage. Dowry contrasts with the related concepts of bride price and dower. While bride price or bride service is a payment ...

. Ultimately the manor was conveyed whole to John de Beverley and, on his death in 1480, to his widow, Amice, who survived until 1416. Amice held the manor in her own name in chief, i.e. directly from the king, by knight service, i.e. in return for supplying military assistance to the king. Amice leased half the manor to Sir Humphrey Stafford of Hook, in Dorset and her heirs sold this land to him. The exact history of the other half is unclear, but Humphrey's grandson, also called Humphrey, seems to have reunited the manor under his control and was known as "Lord of Penkridge" in his later years. These Humphrey Staffords were distant relatives of the local de Staffords. The younger Humphrey died in 1461 and Penkridge passed, via his heirs, into the hands of Robert Willoughby, 2nd Baron Willoughby de Broke

Robert Willoughby, 2nd Baron Willoughby de Broke and ''de jure'' 10th Baron Latimer, (1472 – 10 November 1521) was an English nobleman and soldier.

Robert Willoughby was born about 1470–1472 (aged 30 in 1502, 36 in 1506), the son of Sir ...

, a distinguished soldier and courtier of Henry VIII.

:* Penkridge Deanery Manor, held by successive Archbishops of Dublin from the 1220s.

:* Congreve, which was originally a part or "member" of Penkridge manor. As late as the 19th century, the lords of Congreve paid a tiny rent, £1 1s., to the lords of Penkridge. In the 13th century the Teveray family became established at Congreve, although not without protracted disputes, and by 1302 it was being described as a manor. In the 14th century, the Dumbleton family acquired all the rights from the disputing parties and were soon being addressed as ''de Congreve''. The same Congreve family held the manor until modern times, residing at Congreve Manor House.

:* Congreve Prebendal Manor, which belonged to St. Michael's College, and was centred on Congreve House, about 250m. from the Manor House.

:* Drayton, also originally a part of Penkridge manor. The overlordship was held by the de Staffords from the 12th century and the Barons Stafford claimed it for centuries after. However, Hervey Bagot, who had married Millicent de Stafford, got into protracted and complex legal difficulties over the tenure of Drayton. These were ultimately resolved by all parties agreeing to give the manor to the

:* Congreve, which was originally a part or "member" of Penkridge manor. As late as the 19th century, the lords of Congreve paid a tiny rent, £1 1s., to the lords of Penkridge. In the 13th century the Teveray family became established at Congreve, although not without protracted disputes, and by 1302 it was being described as a manor. In the 14th century, the Dumbleton family acquired all the rights from the disputing parties and were soon being addressed as ''de Congreve''. The same Congreve family held the manor until modern times, residing at Congreve Manor House.

:* Congreve Prebendal Manor, which belonged to St. Michael's College, and was centred on Congreve House, about 250m. from the Manor House.

:* Drayton, also originally a part of Penkridge manor. The overlordship was held by the de Staffords from the 12th century and the Barons Stafford claimed it for centuries after. However, Hervey Bagot, who had married Millicent de Stafford, got into protracted and complex legal difficulties over the tenure of Drayton. These were ultimately resolved by all parties agreeing to give the manor to the Augustinian Augustinian may refer to:

*Augustinians, members of religious orders following the Rule of St Augustine

*Augustinianism, the teachings of Augustine of Hippo and his intellectual heirs

*Someone who follows Augustine of Hippo

* Canons Regular of Sain ...

priory

A priory is a monastery of men or women under religious vows that is headed by a prior or prioress. Priories may be houses of mendicant friars or nuns (such as the Dominicans, Augustinians, Franciscans, and Carmelites), or monasteries of ...

of St. Thomas near Stafford.

:* Gailey, which had once been granted to Burton Abbey

Burton Abbey at Burton upon Trent in Staffordshire, England, was founded in the 7th or 9th century by St Modwen or Modwenna. It was refounded in 1003 as a Benedictine abbey by the thegn Wulfric Spott. He was known to have been buried in the abbey ...

by Wulfric Spot

Wulfric (died ''circa'' 1004), called Wulfric Spot or Spott, was an Anglo-Saxon nobleman. His will is an important document from the reign of King Æthelred the Unready. Wulfric was a patron of the Burton Abbey, around which the modern town of ...

. By the 12th century the de Staffords were overlords and granted it as a fief

A fief (; la, feudum) was a central element in medieval contracts based on feudal law. It consisted of a form of property holding or other rights granted by an overlord to a vassal, who held it in fealty or "in fee" in return for a form ...

to one Rennerius, who in turn gave it to the nuns of Blithbury priory. It then passed quickly to Black Ladies Priory, Brewood, before being acquired by the king around 1189, to become a hay or division of the royal forest

A royal forest, occasionally known as a kingswood (), is an area of land with different definitions in England, Wales, Scotland and Ireland. The term ''forest'' in the ordinary modern understanding refers to an area of wooded land; however, the ...

of Cannock or Cannock Chase

Cannock Chase (), often referred to locally as The Chase, is a mixed area of countryside in the county of Staffordshire, England. The area has been designated as the Cannock Chase Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty and is managed by Forestry E ...

.

:* Levedale, which also had the de Staffords as overlords. At Domesday the tenants were Brien and Drew and, for centuries after, the mesne lord

A mesne lord () was a lord in the feudal system who had vassals who held land from him, but who was himself the vassal of a higher lord. Owing to '' Quia Emptores'', the concept of a mesne lordship technically still exists today: the partitioni ...

s, or intermediate tenants were descendants of Brien, the de Standon family. In the mid-12th century, the terre tenant, the actual resident lord of the manor, was Engenulf de Gresley, who had no sons but divided the manor among his three daughters. This unleashed a series of family disputes, legal wrangles and displays of petty greed that went on for centuries. For example, around 1272, Amice, widow of Henery of Verdun, a deceased lord of Levedale, abducted her own son from the custody of the overlord, Robert de Standon. Robert took Amice to court, where she was forced to admit to the facts of the case, and was ordered to return young Henry to Robert.

:* Longridge, which seems to have belonged to the prebend of Coppenhall, and so formed part of the estates of St. Michael's College. However, a number of small landowners held a considerable part of it, apparently as tenants of the prebend.

:* Lyne Hill or Linhull, apparently belonging to the deanery, but mainly in the hands of a family who are called variously de Linhill, de Lynhull, Lynell or Lynehill.

:* Mitton, which had the de Staffords as overlords and the de Standons as mesne lords, like Levedale. By the mid-11th century, it was in the hands of a family known as de Mutton. Isabel de Mutton inherited the estate while still an infant around 1241 and was taken into the custody of Robert de Stafford. Custody was contested by the de Standons, who claimed the de Muttons were their direct tenants at Mitton, and that they were 40s. out of pocket because of Robert's high-handed actions. Robert claimed, on the contrary, that the de Mittons held two other properties directly of himself. The de Standons argued that theirs was a prior claim. After a long wrangle, Robert de Stafford agreed to hand over the heiress to the de Standons. Later Isabel married Philip de Chetwynd of Ingestre

Ingestre is a village and civil parish in the Stafford district, in the county of Staffordshire, England. The population of the civil parish taken at the 2011 census was 194. It is four miles to the north-east of the county town of Stafford.

Ing ...

. He almost lost Mitton during the Second Barons' War

The Second Barons' War (1264–1267) was a civil war in England between the forces of a number of barons led by Simon de Montfort against the royalist forces of King Henry III, led initially by the king himself and later by his son, the fu ...

. He was accused of helping Ralph Basset of Drayton Bassett

Drayton Bassett is a village and civil parish since 1974 in Lichfield District in Staffordshire, England.

The village is on the Heart of England Way, a footpath. Much of the housing is clustered together but more than half is 20th century in t ...

to seize Stafford and hold it against a royalist army. His estates were forfeit but under the Dictum of Kenilworth

The Dictum of Kenilworth, issued on 31 October 1266, was a pronouncement designed to reconcile the rebels of the Second Barons' War with the royal government of England. After the baronial victory at the Battle of Lewes in 1264, Simon de Montfor ...

he was allowed to redeem them from Robert Blundel, who had been given the redemption by the King. He stoutly maintained his innocence of all charges throughout. Mitton passed into the estates of the Chetwynd family of Ingestre through the son of Isabel and Philip, also called Philip. During her second marriage, to Roger de Thornton, Isabel energetically harried tenants whom she accused of cutting down trees and taking fish from her pools.

:* La More (later Moor Hall), a small manor to just west of Penkridge. Its overlord was the church of St. Michael, to which it returned whenever there was an interregnum among the tenants, the de la More family. The chief of these occurred from 1293, when William de la More was hanged for a felony.

:* Otherton, another small manor, but old enough to be mentioned in Domesday. In late Anglo-Saxon times it was held by Ailric, but by 1886 it was part of the de Stafford barony, although held by Clodoan. In the 13th century the overlordship passed to the de Loges family of Great Wyrley

Great Wyrley is a large village and civil parish in Staffordshire, England. It is coterminous with the villages of Landywood and Cheslyn Hay in the South Staffordshire district. It lies 5.5 miles north of Walsall, West Midlands. It had a po ...

and in the 14th to the lords of Rodbaston, the de Haughton family. The manor was actually held by a local family who took their surname from it, the de Othertons, until it passed to the Wynnesbury family of Pillaton in the 15th century.

:* Pillaton, a small manor east of Penkridge. The overlord was Burton Abbey

Burton Abbey at Burton upon Trent in Staffordshire, England, was founded in the 7th or 9th century by St Modwen or Modwenna. It was refounded in 1003 as a Benedictine abbey by the thegn Wulfric Spott. He was known to have been buried in the abbey ...

, which had received the land from Wulfric Spot

Wulfric (died ''circa'' 1004), called Wulfric Spot or Spott, was an Anglo-Saxon nobleman. His will is an important document from the reign of King Æthelred the Unready. Wulfric was a patron of the Burton Abbey, around which the modern town of ...

in 1044. It was held from the abbey by a succession of families and became part of the Wynnesbury lands in the 15th century.

:* Preston, which belonged to the College of St. Michael after it was made part of the prebend of Penkridge by the gift of a woman called Avice in the mid-13th century. The canons let it to a succession of tenants, who paid a tithe to the prebend.

:* Rodbaston, which also existed before the Norman Conquest, and was held by an Anglo-Saxon free man called Alli in 1066. After belonging for some centuries to the lords of Great Wyrley, it was united with Penkridge manor in the hands of John de Beverley around 1372.

:* Water Eaton, another pre-Conquest manor that came under de Stafford overlordship. They let it to the de Stretton family, who subsequently became overlords and let it to sub-tenants. These were the de Beysin family, who became embroiled in a protract disputes with the Crown over encroachments on the estate by the royal forest. In 1315 they went so far as to petition Parliament for an enquiry into the matter. Ultimately the de Beysins rented out the land and ceased to live locally.

:* Whiston, which came under the overlordship of Burton Abbey from 1004. One of the tenants, a John de Whiston, fought as a

:* Whiston, which came under the overlordship of Burton Abbey from 1004. One of the tenants, a John de Whiston, fought as a knight

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of knighthood by a head of state (including the Pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church or the country, especially in a military capacity. Knighthood finds origins in the Gr ...

at the Battle of Crécy

The Battle of Crécy took place on 26 August 1346 in northern France between a French army commanded by King PhilipVI and an English army led by King EdwardIII. The French attacked the English while they were traversing northern France du ...

in 1346. Subsequently the manor fell into a slough of litigation when a succession of short-lived lords of the manor (probably the result of the Black Death, left their heirs intractable problems of tenure.

:* Coppenhall or Copehale, now a separate parish from Penkridge, although part of it in the middle ages. It was a manor in Anglo-Saxon times and at Domesday the overlords were the de Staffords, although the tenant was a man called Bueret. His sone, Ulpher de Coppenhall, divided the manor in two, introducing the Bagot family, whose half was called the Hyde. The Bagots seem to have been prone to particularly vicious family disputes. The Staffordshire Plea rolls

Plea rolls are parchment rolls recording details of legal suits or actions in a court of law in England.

Courts began recording their proceedings in plea rolls and filing writs from their foundation at the end of the 12th century. Most files were ...

for 1250 record that Ascira, the widow of Robert Bagot, sued William Bagot, presumably her stepson, for a third of various properties at Coppenhall and the Hyde, and elsewhere, as her dower

Dower is a provision accorded traditionally by a husband or his family, to a wife for her support should she become widowed. It was settled on the bride (being gifted into trust) by agreement at the time of the wedding, or as provided by law. ...

. William replied that Ascira had never been lawfully married to his father, and the case was referred to the Bishop of Worcester. The Bagots maintained a presence at the Hyde until the 14th century, when the line died out and the land reverted to the de Staffords. Edmund Stafford, 5th Earl of Stafford

Edmund Stafford, 5th Earl of Stafford and 1st Baron Audley, KG, KB (2 March 1377 – 21 July 1403) was the son of Hugh de Stafford, 2nd Earl of Stafford, and his wife Philippa de Beauchamp.

He inherited the earldom at the age of 18, the third ...

, died fighting for Henry IV at the Battle of Shrewsbury

The Battle of Shrewsbury was a battle fought on 21 July 1403, waged between an army led by the Lancastrian King Henry IV and a rebel army led by Henry "Harry Hotspur" Percy from Northumberland. The battle, the first in which English archers ...

. The infant heir became the king's ward and Henry used the opportunity to grant part of Coppenhall to his new wife, Joan of Navarre Joan of Navarre may refer to:

*Joan I of Navarre (1273–1305), daughter of Henry I of Navarre

*Joan II of Navarre (1312–1349), daughter of Louis I of Navarre

* Joan of Navarre (nun) (1326–1387), daughter of Joan II of Navarre and Philip III of ...

. The remainder stayed with the Barons Stafford and they granted it to their relatives, the de Staffords of Hooke, Dorset

Hooke is a small village and civil parish in the county of Dorset in southern England, situated about northeast of the town of Bridport. It is sited in the valley of the short River Hooke, a tributary of the River Frome, amongst the chalk hills ...

. After further disputes and complications, it ended in the hands of Robert Willoughby, 1st Baron Willoughby de Broke

Robert Willoughby, 1st Baron Willoughby de Broke, ''de jure'' 9th Baron Latimer (c. 1452 – 23 August 1502), KG, of Brook, Westbury, Wiltshire, was one of the chief commanders of the royal forces of King Henry VII against the Cornish Rebe ...

.

:* Dunston, originally a member of Penkridge manor. By 1166, Robert de Stafford was recognised as overlord and Hervey de Stretton was his tenant at Dunston, although the de Staffords themselves retained land at Dunston at least until the 16th century. The lordship and the bulk of the land descended in the de Stretton family for several generations but, by 1285, they were renting most of their land to the Pickstock family, and in 1316 John Pickstock was named as lord of Dunston. The Pickstocks's were burgesses of the county town of Stafford and remained lords of the manor for several generations until John Pickstock granted most of his lands to members of the Derrington family in 1437.

:* Stretton, also now outside Penkridge parish. Before the Norman Conquest it had been held by three thegns, but Domesday found it held by Hervey de Stretton under the overlordship of Robert de Stafford

Robert de Stafford ( 1039 – c. 1100) (''alias'' Robert de Tosny/Toeni, etc.) was an Anglo-Norman nobleman, the first feudal baron of Stafford in Staffordshire in England, where he built as his seat Stafford Castle. His many landholdings are l ...

. By the 14th century the Congreve family owned the manor.

The complexity of land tenure in feudal Penkridge is obvious. The actual cultivators, mainly villein

A villein, otherwise known as ''cottar'' or '' crofter'', is a serf tied to the land in the feudal system. Villeins had more rights and social status than those in slavery, but were under a number of legal restrictions which differentiated them ...

s and other lowly labourers, were at the bottom of a social pyramid that could have four or five layers under the king at its apex. This was due to the practice of subinfeudation, by which estates were constantly granted and re-granted, often sub-divided, in return for feudal dues - typically military service. Low life expectancy, especially during times of war and plague, created constant succession disputes. A common complaint was that of the widow, often neglected by children or step-children, who then launched legal action to regain life interest in part of the estate - usually a third. Infant heirs fell into the clutches of the overlord, sometimes the king, who was in a position to exploit the estate unmercifully during the minority and to extort a hefty feudal relief Feudal relief was a one-off "fine" or form of taxation payable to an overlord by the heir of a feudal tenant to license him to take possession of his fief, i.e. an estate-in-land, by inheritance. It is comparable to a death duty or inheritance ta ...

on succession, as did John and Henry IV. Lack of a male heir often led to temporary or permanent division of an estate among daughters, giving ample opportunity for further family dispute. It was this sort of dispute finally exasperated Hervey Bagot and his rivals and induced them to give Drayton to the Church.

The Staffords were a powerful family with many branches, and with great influence in regional and national affairs, stemming from a grant of large estates to Robert de Stafford

Robert de Stafford ( 1039 – c. 1100) (''alias'' Robert de Tosny/Toeni, etc.) was an Anglo-Norman nobleman, the first feudal baron of Stafford in Staffordshire in England, where he built as his seat Stafford Castle. His many landholdings are l ...

by William the Conqueror

William I; ang, WillelmI (Bates ''William the Conqueror'' p. 33– 9 September 1087), usually known as William the Conqueror and sometimes William the Bastard, was the first House of Normandy, Norman List of English monarchs#House of Norman ...

. They were important as both overlords and as actual working landowners in the region around Stafford, including Penkridge parish. Beneath them came a class of middling landowners, who often had many holdings at different levels in the feudal pyramid. A good example was Hugh de Loges, a mid-13th-century baron, who was lord of Great Wyrley

Great Wyrley is a large village and civil parish in Staffordshire, England. It is coterminous with the villages of Landywood and Cheslyn Hay in the South Staffordshire district. It lies 5.5 miles north of Walsall, West Midlands. It had a po ...

in Cannock; lord of Lyne Hill in Penkridge, which he probably held of the Penkridge deanery manor; lord of Otherton, where he owed fealty to the de Staffords; and lord of Rodbaston, which he held by serjeanty in Cannock Chase. The Church was a major landowner in Penkridge and the extent of church holdings was to have important consequences during the Reformation, as church property was seized by the Crown. However, many estates were very small, with petty manorial lords struggling to meet their dues and debts.

Even the most minor lord of the manors had great power over his tenants, especially the villeins and others bound to the estate. Typical of the rights enjoyed by a small manorial lord would be those claimed by St. Michael's at La More in 1293:

:* View of frankpledge

Frankpledge was a system of joint suretyship common in England throughout the Early Middle Ages and High Middle Ages. The essential characteristic was the compulsory sharing of responsibility among persons connected in tithings. This unit, under ...

- holding tenants collectively responsible for lawbreaking

:* Assize of Bread and Ale - regulating the price and quality of foodstuffs and imposing fines on offenders

:* Infangthief - pursuit and punishment of offenders within the manor.

A more important landowner, like John de Beverley, in 1372 acquired the rights of:

:* Outfangthief - transferring offenders caught outside the manor to his own court for summary justice

:* Gallows

A gallows (or scaffold) is a frame or elevated beam, typically wooden, from which objects can be suspended (i.e., hung) or "weighed". Gallows were thus widely used to suspend public weighing scales for large and heavy objects such as sacks ...

- capital punishment of offenders

:* Waif and stray

Waif and stray was a legal privilege commonly granted by the Crown to landowners under Anglo-Norman law. It usually appeared as part of a standard formula in charters granting privileges to estate-holders, along the lines of "with sac and soc, toll ...

- confiscating any animal found wandering or lost.

From the 14th century, the feudal system in Penkridge, as elsewhere, began to break down. Edward I's law

From the 14th century, the feudal system in Penkridge, as elsewhere, began to break down. Edward I's law Quia Emptores

''Quia Emptores'' is a statute passed by the Parliament of England in 1290 during the reign of Edward I that prevented tenants from alienating their lands to others by subinfeudation, instead requiring all tenants who wished to alienate the ...

of 1290 changed the legal framework radically by banning subinfeudation. The Black Death and population collapse of the 14th century made labour expensive and land relatively cheap, encouraging landowners to look for money from rents, with which they paid for labour. In the 15th century, a new regime of cash, commodities, wages, rents and leases took shape, and with it came great changes in land tenure.

The most important beneficiaries were to be the Littleton family. Richard Littleton was the second son of Thomas de Littleton

Sir Thomas de Littleton or de Lyttleton KB ( 140723 August 1481) was an English judge, undersheriff, Lord of Tixall Manor, and legal writer from the Lyttelton family. He was also made a Knight of the Bath by King Edward IV.

Family

Thomas ...

, a prominent jurist from Frankley

Frankley is a village and civil parish in Worcestershire. The modern Frankley estate is part of the New Frankley civil parish in Birmingham, and has been part of the city since 1995. The parish has a population of 122.

History

Frankley is li ...

, Worcestershire. Thomas had direct connections to the area, as he had married Joan Burley, widow of the fifth Philip Chetwynd, lord of Mitton. Richard first appears as a tenant and perhaps steward of William Wynnesbury, who held Pillaton and Otherton in the late 15th century. Richard married Alice, his landlord's daughter, who inherited the estates When William died in 1502. Alice passed them on her death to her son, Sir Edward Littleton. Pillaton Hall

Pillaton Hall was an historic house located in Pillaton, Staffordshire, near Penkridge, England. For more than two centuries it was the seat of the Littleton family, a family of local landowners and politicians. The 15th century gatehouse is the ...

, which they rebuilt, was to be the seat of the Littletons for two and a half centuries, and from it they built a property empire, using leases as the key. Land leases - typically of twenty years - gave them effective management of larger and larger estates. When the opportunity to buy appeared, they were in the best position to do so, as an extant lease deterred other buyers. Richard died in 1518, although Alice survived him by eleven years. They were buried in a table tomb in a new family chapel in St. Michael's church.

The traditional economy

Medieval Penkridge was clearly a place of ecclesiastical and commercial importance, but most of its population was at least partly dependent on agriculture for a living.Agricultural expansion

Agricultural expansion describes the growth of agricultural land (arable land, pastures, etc.) especially in the 20th and 21st centuries.

The agricultural expansion is often explained as a direct consequence of the global increase in food and en ...

was greatly impeded by the Forest Law imposed after the Norman Conquest

The Norman Conquest (or the Conquest) was the 11th-century invasion and occupation of England by an army made up of thousands of Norman, Breton, Flemish, and French troops, all led by the Duke of Normandy, later styled William the Con ...

, which preserved the wildlife and ecology of the area for the king's enjoyment through a savage penal code. Large areas surrounding Penkridge were incorporated into the Royal Forest of Cannock or Cannock Chase

Cannock Chase (), often referred to locally as The Chase, is a mixed area of countryside in the county of Staffordshire, England. The area has been designated as the Cannock Chase Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty and is managed by Forestry E ...

, forming the divisions of the forest known as Gailey Hay and Teddesley Hay. The forest extended in a broad arc across Staffordshire, with Cannock Chase bordering Brewood Forest at the River Penk, and the latter stretching to meet Kinver Forest to the south. The First Barons' War

The First Barons' War (1215–1217) was a civil war in the Kingdom of England in which a group of rebellious major landowners (commonly referred to as barons) led by Robert Fitzwalter waged war against King John of England. The conflict resulte ...

of the 13th century initiated a process of gradual relaxation of the laws, starting with the first issue of the Forest Charter in 1217. So it was in Henry III's reign that Penkridge began to grow economically and probably in population. Local people were quick to seize any chance that presented itself. In the mid-13th century there were complaints about assarting

Assarting is the act of clearing forested lands for use in agriculture or other purposes. In English land law, it was illegal to assart any part of a royal forest without permission. This was the greatest trespass that could be committed in a ...

, clearing of trees and scrub to create fields, by the residents of Otherton and Pillaton. However, the struggle against the forests was not over. At times the kings' servants tried to push forward the boundaries of the forest, particularly from Gailey Hay along the southern edge of the parish.

Much of the area was cultivated under the open field system

The open-field system was the prevalent agricultural system in much of Europe during the Middle Ages and lasted into the 20th century in Russia, Iran, and Turkey. Each manor or village had two or three large fields, usually several hundred acr ...

. The names of the open fields and common meadows in Penkridge were recorded for the first time just as they were about to be enclosed

Enclosure or Inclosure is a term, used in English landownership, that refers to the appropriation of "waste" or "common land" enclosing it and by doing so depriving commoners of their rights of access and privilege. Agreements to enclose land ...

, in the 16th and 17th centuries, although they must have existed throughout the Middle Ages. In Penkridge manor in the early 16th century, the open fields were Clay Field, Prince Field, Manstonshill, Mill Field, Wood Field, and Lowtherne or Lantern Field. In the 17th century there were mentions of Fyland, Old Field, and Whotcroft. Stretton Meadow and Hay Meadow seem to have been common grazing, the latter on the right bank of the Penk, between the Cuttlestone and Bull Bridges. The Deanery Manor had at least two open fields, called Longfurlong and Clay Field, the latter perhaps adjoining the land of the same name in Penkridge manor. In most of the smaller manors, too, open fields are known to have existed. For example, Rodbaston had Low Field, Overhighfield and Netherfield. Initially the cultivators were mainly unfree, villein

A villein, otherwise known as ''cottar'' or '' crofter'', is a serf tied to the land in the feudal system. Villeins had more rights and social status than those in slavery, but were under a number of legal restrictions which differentiated them ...

s or even slaves, forced to work on the lord's land in return for their strips in the open fields. However, this pattern would have collapsed from the mid-14th century, as the Black Death drastically reduced the labour supply and, with it, the value of land. In 1535, as the Priory of St. Thomas faced dissolution, its manor of Drayton was worth £9 4s. 8d. annually, and the lion's share, £5 18s. 2d., came from rents. This pattern of commuting labour service for rent was more or less complete by this time and landlords used the money to buy in labour when required.

There are no detailed records of what was grown in medieval Penkridge. In 1801, when the first record was made, nearly half was under wheat

Wheat is a grass widely cultivated for its seed, a cereal grain that is a worldwide staple food. The many species of wheat together make up the genus ''Triticum'' ; the most widely grown is common wheat (''T. aestivum''). The archaeologi ...

, with barley

Barley (''Hordeum vulgare''), a member of the grass family, is a major cereal grain grown in temperate climates globally. It was one of the first cultivated grains, particularly in Eurasia as early as 10,000 years ago. Globally 70% of barley p ...

, oats

The oat (''Avena sativa''), sometimes called the common oat, is a species of cereal grain grown for its seed, which is known by the same name (usually in the plural, unlike other cereals and pseudocereals). While oats are suitable for human co ...

, peas, beans, and brassicas

''Brassica'' () is a genus of plants in the cabbage and mustard family (Brassicaceae). The members of the genus are informally known as cruciferous vegetables, cabbages, or mustard plants. Crops from this genus are sometimes called ''cole cro ...

the other major crops - probably similar to the medieval pattern: farmers grew wheat wherever the land in their scattered strips supported it, and other crops elsewhere, with cattle on the riverside meadows and sheep on the heath.

Markets and mills

Markets were potentially very lucrative for manorial lords but it was necessary to obtain a royal charter before one could be instituted. Hugh Hose's grant of Penkridge manor to the Archbishop of Dublin in 1215 included the right to hold an annual fair, although it is not known whether Hugh had actually obtained the right to hold one. Nevertheless, Edward I recognised Hugh le Blund's right to a fair in 1278 and the grant was confirmed to Hugh and his heirs by Edward II in 1312. John de Beverley, got confirmation of the fair in 1364, and it passed down with the manor until at least 1617. The precise date varied considerably, but in the Middle Ages it fell around the end of September and lasted for seven or eight days. Although it was initially a general fair, it gradually grew into ahorse fair A horse fair is a (typically annual) fair where people buy and sell horses.

In the United Kingdom there are many fairs which are traditionally attended by Romani people and travellers who converge at the fairs to buy and sell horses, meet with fr ...

.

Henry III granted Andrew le Blund a weekly market in 1244 and John de Beverley gained recognition for this also in 1364. When Amice, his widow remarried, the market was challenged as unfair competition to the burgesses of Stafford – an accusation they frequently made against markets in the area, including also that at Brewood

Brewood is an ancient market town in the civil parish of Brewood and Coven, in the South Staffordshire district, in the county of Staffordshire, England. Located around , Brewood lies near the River Penk, eight miles north of Wolverhampton c ...

. Presumably Amice vindicated her right to a market because she was able to pass it on to her successors at her death in 1416. For centuries the market was held every Tuesday. The marketplace was situated at the eastern end of the town, the opposite end from the church. It is still so-named, although it is no longer used for the purpose. After 1500 the market declined and faded out. It was revived several times, also changing days. The modern market is an entirely new institution on a different site.

Water power was plentiful in the Penkridge area, with the River Penk and a number of tributary brooks able to drive mills. Mills are regularly mentioned in land records and wills because they were such a source of profit to the owner. For the same reason, they were a major cause of grievance among tenants, who were compelled to use the lord's mill and to pay for the service, usually in kind. Domesday records a mill at Penkridge itself and another at Water Eaton. A century later there were two mills at Penkridge, one of them later named as the ''broc'' mill – presumably on one of the brooks that flow into the Penk. One of the Penkridge mills was given to William Houghton, Archbishop of Dublin, by the de la More family in 1298, but it appears that the same family continued to operate the mill, as a later archbishop granted them mill pond at an annual rent of 1d. in 1342. There was a mill at Drayton by 1194 and Hervey Bagot gave it to St. Thomas's Priory, along with the manor. Mills are recorded at Congreve, Pillaton, and Rodbaston in the 13th century, at Whiston in the 14th, and at Mitton in the 15th. These were all primarily corn mills, but water power was harnessed to many other purposes even in the Middle Ages: in 1345 we hear of a fulling mill

Fulling, also known as felting, tucking or walking ( Scots: ''waukin'', hence often spelled waulking in Scottish English), is a step in woollen clothmaking which involves the cleansing of woven or knitted cloth (particularly wool) to elimin ...

at Water Eaton, as well as the corn mill.

Edward Littleton (died 1558)

Edward Littleton or Edwarde Lyttelton (by 1489–1558) was a Staffordshire landowner from the extended Littleton/Lyttelton family. He also served as soldier and Member of Parliament for Staffordshire in the House of Commons of England, th ...

and his wives, Helen Swynnerton and Isabel Wood. Attributed to the Royley workshop in Burton on Trent.

File:Penkridge St Michael - Edward Littleton 1558 02.jpg, Helen Swynnerton's gable hood

A gable hood, English hood or gable headdress is an English woman's headdress of , so-called because its pointed shape resembles the gable of a house. The contemporary French hood was rounded in outline and unlike the gable hood, less conservativ ...

clearly places her in an earlier, pre-Reformation, age.

File:Penkridge St Michael - Edward Littleton 1574.jpg, Tomb of Sir Edward Littleton (died 1574) and his wife, Alice Cockayne. The high ruffs for both are characteristic of the period. Attributed to the Royley workshop in Burton on Trent.

File:Penkridge St Michael - Edward Littleton 1574 02.jpg, Alice Cockayne. The Royleys once again show intricate details of dress and fashion, while the modelling of faces is highly stereotypical.