History of Mahdist Sudan on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Mahdist State, also known as Mahdist Sudan or the Sudanese Mahdiyya, was a state based on a religious and political movement launched in 1881 by Muhammad Ahmad bin Abdullah (later Muhammad

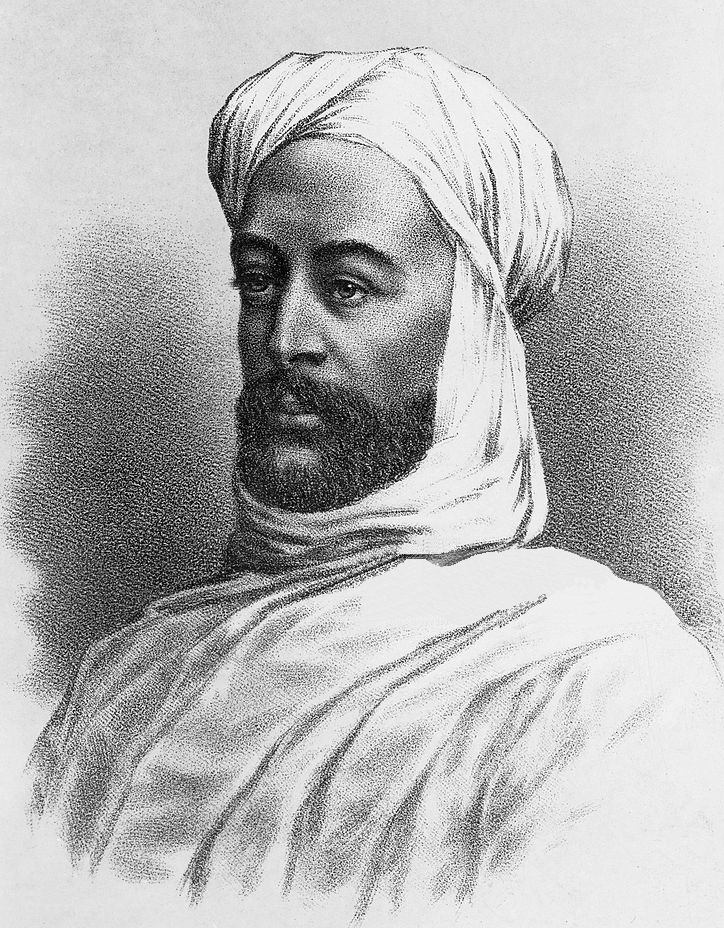

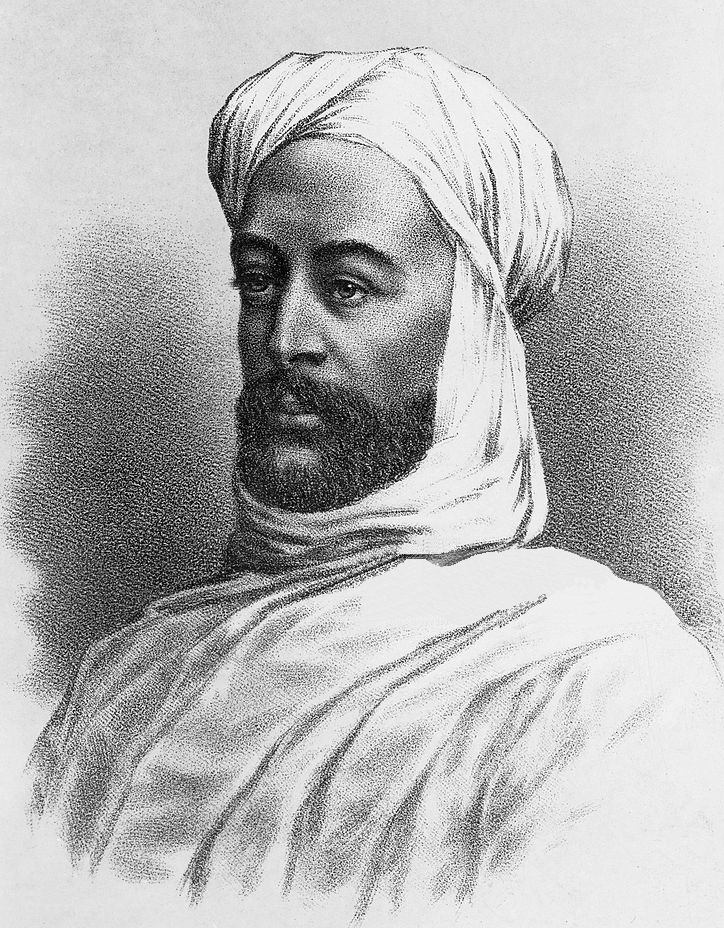

In this troubled atmosphere, Muhammad Ahmad ibn as Sayyid Abd Allah, who combined personal charisma with a religious and political mission, emerged, determined to expel the

In this troubled atmosphere, Muhammad Ahmad ibn as Sayyid Abd Allah, who combined personal charisma with a religious and political mission, emerged, determined to expel the  In 1881, Muhammad Ahmad proclaimed himself the Mahdi ("expected one"). Some of his most dedicated followers regarded him as directly inspired by Allah. He wanted Muslims to reclaim the Quran and hadith as the foundational sources of Islam, creating a just society. Specifically relating to Sudan, he claimed its poverty was a virtue and denounced worldly wealth and luxury. For Muhammad Ahmad, Egypt was an example of wealth leading to impious behavior. Muhammad Ahmad's calls for an uprising found great appeal among the poorest communities along the Nile, as it combined a nationalist, anti-Egyptian agenda with fundamentalist religious certainty.

Even after the Mahdi proclaimed a jihad, or holy war, against the Egyptians,

In 1881, Muhammad Ahmad proclaimed himself the Mahdi ("expected one"). Some of his most dedicated followers regarded him as directly inspired by Allah. He wanted Muslims to reclaim the Quran and hadith as the foundational sources of Islam, creating a just society. Specifically relating to Sudan, he claimed its poverty was a virtue and denounced worldly wealth and luxury. For Muhammad Ahmad, Egypt was an example of wealth leading to impious behavior. Muhammad Ahmad's calls for an uprising found great appeal among the poorest communities along the Nile, as it combined a nationalist, anti-Egyptian agenda with fundamentalist religious certainty.

Even after the Mahdi proclaimed a jihad, or holy war, against the Egyptians,

After reaching Khartoum in February 1884, Gordon soon realized that he could not extricate the garrisons. As a result, he called for reinforcements from Egypt to relieve Khartoum. Gordon also recommended that

After reaching Khartoum in February 1884, Gordon soon realized that he could not extricate the garrisons. As a result, he called for reinforcements from Egypt to relieve Khartoum. Gordon also recommended that

Six months after the capture of Khartoum, the Mahdi died, probably of

Six months after the capture of Khartoum, the Mahdi died, probably of

The Anglo-Egyptian Sudan: A Compendium Prepared by Officers of the Sudan Government

', Vol. 1, p. 99. Harrison & Sons (London), 1905. Accessed 13 Feb 2014. The next year, the British then constructed a new rail line directly across the desert from Wadi Halfa to Abu Hamad,Sudan Railway Corporation.

Historical Background

". 2008. Accessed 13 Feb 2014. which they captured in the

The Mahdist State had a large military which became increasingly professional as time went on. From an early point, the Mahdist armies recruited defectors from the Egyptian Army and organized professional soldiers in the form of the ''jihadiya'', mostly Black Sudanese. These were supported by tribal spearmen and swordsmen as well as cavalry. The ''jihadiya'' and some tribal units lived in military barracks, while the rest were more akin to militia. The Mahdist armies also possessed limited artillery, including mountain guns and even machine guns. However, these were few in numbers, and thus only used as defenses for important towns and to the river steamers that acted as the state's navy. In general, the Mahdist armies were highly motivated by their belief system. Exploiting this, the Mahdist commanders used their riflemen to screen charges by their melee infantry and cavalry. Such attacks often proved effective, but also led to extremely high losses when employed "unimaginatively". The Europeans generally called the Mahdist soldiers "dervishes".

Muhammad Ahmad's early insurgent force which was mostly recruited among the poor Arab communities living at the Nile. The later armies of the Mahdiyah were recruited among various groups, including mostly autonomous groups such as the

The Mahdist State had a large military which became increasingly professional as time went on. From an early point, the Mahdist armies recruited defectors from the Egyptian Army and organized professional soldiers in the form of the ''jihadiya'', mostly Black Sudanese. These were supported by tribal spearmen and swordsmen as well as cavalry. The ''jihadiya'' and some tribal units lived in military barracks, while the rest were more akin to militia. The Mahdist armies also possessed limited artillery, including mountain guns and even machine guns. However, these were few in numbers, and thus only used as defenses for important towns and to the river steamers that acted as the state's navy. In general, the Mahdist armies were highly motivated by their belief system. Exploiting this, the Mahdist commanders used their riflemen to screen charges by their melee infantry and cavalry. Such attacks often proved effective, but also led to extremely high losses when employed "unimaginatively". The Europeans generally called the Mahdist soldiers "dervishes".

Muhammad Ahmad's early insurgent force which was mostly recruited among the poor Arab communities living at the Nile. The later armies of the Mahdiyah were recruited among various groups, including mostly autonomous groups such as the

The Mahdist navy emerged during the early rebellion, as the insurgents took control of boats operating on the Nile. In May 1884, the Mahdists captured the steamboats ''Fasher'' and ''Musselemieh'', followed by the ''Muhammed Ali'' and ''Ismailiah''. In addition, several armed steamboats which had been supposed to aid Charles Gordon's besieged force were wrecked and abandoned in 1885. At least two of these, the ''Bordein'' and ''Safia'', were salvaged by the Mahdists. The captured steamboats were armed with light artillery pieces, and crewed by Egyptians as well as Sudanese. The Mahdist navy also used supply ships.

In October 1898, parts of the Mahdist navy were sent up the White Nile to assist the expedition against Emin Pasha's forces. The ''Ismailiah'' was sunk on 17 August 1898 as it was placing

The Mahdist navy emerged during the early rebellion, as the insurgents took control of boats operating on the Nile. In May 1884, the Mahdists captured the steamboats ''Fasher'' and ''Musselemieh'', followed by the ''Muhammed Ali'' and ''Ismailiah''. In addition, several armed steamboats which had been supposed to aid Charles Gordon's besieged force were wrecked and abandoned in 1885. At least two of these, the ''Bordein'' and ''Safia'', were salvaged by the Mahdists. The captured steamboats were armed with light artillery pieces, and crewed by Egyptians as well as Sudanese. The Mahdist navy also used supply ships.

In October 1898, parts of the Mahdist navy were sent up the White Nile to assist the expedition against Emin Pasha's forces. The ''Ismailiah'' was sunk on 17 August 1898 as it was placing

al-Mahdi

Abū ʿAbd Allāh Muḥammad ibn ʿAbd Allāh al-Manṣūr ( ar, أبو عبد الله محمد بن عبد الله المنصور; 744 or 745 – 785), better known by his regnal name Al-Mahdī (, "He who is guided by God"), was the third Abb ...

) against the Khedivate of Egypt

The Khedivate of Egypt ( or , ; ota, خدیویت مصر ') was an autonomous tributary state of the Ottoman Empire, established and ruled by the Muhammad Ali Dynasty following the defeat and expulsion of Napoleon Bonaparte's forces which br ...

, which had ruled the Sudan since 1821. After four years of struggle, the Mahdist rebels overthrew the Ottoman-Egyptian administration and established their own "Islamic and national" government with its capital in Omdurman. Thus, from 1885 the Mahdist government maintained sovereignty and control over the Sudanese territories until its existence was terminated by the Anglo-Egyptian forces in 1898.

Mohammed Ahmed al-Mahdi enlisted the people of Sudan in what he declared a jihad against the administration that was based in Khartoum

Khartoum or Khartum ( ; ar, الخرطوم, Al-Khurṭūm, din, Kaartuɔ̈m) is the capital of Sudan. With a population of 5,274,321, its metropolitan area is the largest in Sudan. It is located at the confluence of the White Nile, flowing n ...

, which was dominated by Egyptians and Turks. The Khartoum government initially dismissed the Mahdi's revolution; he defeated two expeditions sent to capture him in the course of a year. The Mahdi's power increased, and his call spread throughout the Sudan, with his movement becoming known as the Ansar. During the same period, the 'Urabi revolution broke out in Egypt, with the British occupying the country in 1882. Britain appointed Charles Gordon as General-Governor of Sudan. Months after his arrival in Khartoum and after several battles with the Mahdi rebels, Mahdist forces captured Khartoum, and Gordon was killed in his palace. The Mahdi did not live long after this victory, and his successor Abdallahi ibn Muhammad

Abdullah Ibn-Mohammed Al-Khalifa or Abdullah al-Khalifa or Abdallahi al-Khalifa, also known as "The Khalifa" ( ar, c. عبدالله بن سيد محمد الخليفة; 184625 November 1899) was a Sudanese Ansar ruler who was one of the principa ...

consolidated the new state, with administrative and judiciary systems based on their interpretation of Islamic law

Sharia (; ar, شريعة, sharīʿa ) is a body of religious law that forms a part of the Islamic tradition. It is derived from the religious precepts of Islam and is based on the sacred scriptures of Islam, particularly the Quran and the ...

.

Sudan's economy was destroyed during the Mahdist War and famine, war and disease reduced the population by half.Jok Madut Jok, ''War and Slavery in Sudan'' (2001) p.75Edward Spiers, Sudan: The Reconquest Reappraised (1998) p.12Henry Cecil Jackson, ''Osman Digna'' (1926) p.185 Muhammad Ahmad al-Mahdi declared all people who did not accept him as the awaited Mahdi to be infidels (kafir

Kafir ( ar, كافر '; plural ', ' or '; feminine '; feminine plural ' or ') is an Arabic and Islamic term which, in the Islamic tradition, refers to a person who disbelieves in God as per Islam, or denies his authority, or reject ...

), ordered their killing and took their women and property.

The British reconquered the Sudan in 1898, ruling it after that in theory as a condominium with Egypt but in practice as a colony. However, remnants of the Mahdist State held out in Darfur until 1909.

History

Background

From the early 19th century, Egypt had begun to conquer the Sudan and transformed it into its colony. This period became locally known as the Turkiyya, i.e. the "Turkish" rule by the Eyalet and laterKhedivate of Egypt

The Khedivate of Egypt ( or , ; ota, خدیویت مصر ') was an autonomous tributary state of the Ottoman Empire, established and ruled by the Muhammad Ali Dynasty following the defeat and expulsion of Napoleon Bonaparte's forces which br ...

. The Egyptians were never able to fully subjugate the region, but their dominion and high taxes made them very unpopular. As discontent in the Sudan grew, Egypt itself began to slip into crisis. This was the result of economic and political changes which involved European powers, most importantly the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

. In 1869, the Suez Canal opened and quickly became Britain's economic lifeline to India and the Far East. To defend this waterway, Britain sought a greater role in Egyptian affairs. In 1873, the British government therefore supported a programme whereby an Anglo-French debt commission assumed responsibility for managing Egypt's fiscal affairs. This commission eventually forced Khedive Ismail

Ishmael ''Ismaḗl''; Classical/Qur'anic Arabic: إِسْمَٰعِيْل; Modern Standard Arabic: إِسْمَاعِيْل ''ʾIsmāʿīl''; la, Ismael was the first son of Abraham, the common patriarch of the Abrahamic religions; and is cons ...

to abdicate in favour of his more politically acceptable son, Tawfiq (1877–1892).

After the removal of Ismail in 1877, who had appointed him to the post, Charles George Gordon

Major-General Charles George Gordon CB (28 January 1833 – 26 January 1885), also known as Chinese Gordon, Gordon Pasha, and Gordon of Khartoum, was a British Army officer and administrator. He saw action in the Crimean War as an officer in ...

resigned as governor general of Sudan in 1880. His successors lacked direction from Cairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the Capital city, capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the List of urban agglomerations in Africa, largest urban agglomeration in Africa, List of ...

and feared the political turmoil that had engulfed Egypt. As a result, they failed to continue the policies Gordon had put in place. The illegal slave trade

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

revived, although not enough to satisfy the merchants whom Gordon had put out of business. The Sudanese army suffered from a lack of resources, and unemployed soldiers from disbanded units troubled garrison towns. Tax collectors arbitrarily increased taxation.

Muhammad Ahmad

In this troubled atmosphere, Muhammad Ahmad ibn as Sayyid Abd Allah, who combined personal charisma with a religious and political mission, emerged, determined to expel the

In this troubled atmosphere, Muhammad Ahmad ibn as Sayyid Abd Allah, who combined personal charisma with a religious and political mission, emerged, determined to expel the Turks

Turk or Turks may refer to:

Communities and ethnic groups

* Turkic peoples, a collection of ethnic groups who speak Turkic languages

* Turkish people, or the Turks, a Turkic ethnic group and nation

* Turkish citizen, a citizen of the Republic ...

and restore Islam to its original purity. The son of a Dongola

Dongola ( ar, دنقلا, Dunqulā), also spelled ''Dunqulah'', is the capital of the state of Northern Sudan, on the banks of the Nile, and a former Latin Catholic bishopric (14th century). It should not be confused with Old Dongola, an ancien ...

boatbuilder, Muhammad Ahmad had become the disciple of Muhammad ash Sharif, the head of the Sammaniyah Sufi order. Later, as a sheikh of the order, Muhammad Ahmad spent several years in seclusion and gained a reputation as a mystic and teacher.

In 1881, Muhammad Ahmad proclaimed himself the Mahdi ("expected one"). Some of his most dedicated followers regarded him as directly inspired by Allah. He wanted Muslims to reclaim the Quran and hadith as the foundational sources of Islam, creating a just society. Specifically relating to Sudan, he claimed its poverty was a virtue and denounced worldly wealth and luxury. For Muhammad Ahmad, Egypt was an example of wealth leading to impious behavior. Muhammad Ahmad's calls for an uprising found great appeal among the poorest communities along the Nile, as it combined a nationalist, anti-Egyptian agenda with fundamentalist religious certainty.

Even after the Mahdi proclaimed a jihad, or holy war, against the Egyptians,

In 1881, Muhammad Ahmad proclaimed himself the Mahdi ("expected one"). Some of his most dedicated followers regarded him as directly inspired by Allah. He wanted Muslims to reclaim the Quran and hadith as the foundational sources of Islam, creating a just society. Specifically relating to Sudan, he claimed its poverty was a virtue and denounced worldly wealth and luxury. For Muhammad Ahmad, Egypt was an example of wealth leading to impious behavior. Muhammad Ahmad's calls for an uprising found great appeal among the poorest communities along the Nile, as it combined a nationalist, anti-Egyptian agenda with fundamentalist religious certainty.

Even after the Mahdi proclaimed a jihad, or holy war, against the Egyptians, Khartoum

Khartoum or Khartum ( ; ar, الخرطوم, Al-Khurṭūm, din, Kaartuɔ̈m) is the capital of Sudan. With a population of 5,274,321, its metropolitan area is the largest in Sudan. It is located at the confluence of the White Nile, flowing n ...

dismissed him as a religious fanatic. The Egyptian government paid more attention when his religious zeal turned to denunciation of tax collectors. To avoid arrest, the Mahdi and a party of his followers, the Ansar, made a long march to Kurdufan

Kordofan ( ar, كردفان ') is a former province of central Sudan. In 1994 it was divided into three new federal states: North Kordofan, South Kordofan and West Kordofan. In August 2005, West Kordofan State was abolished and its territory ...

, where he gained a large number of recruits, especially from the Baggara

The Baggāra ( ar, البَقَّارَة "heifer herder") or Chadian Arabs are a nomadic confederation of people of mixed Arab and Arabized indigenous African ancestry, inhabiting a portion of the Sahel mainly between Lake Chad and the Nile ri ...

. From a refuge in the area, he wrote appeals to the sheikhs of the religious orders and won active support or assurances of neutrality from all except the pro-Egyptian Khatmiyyah

The Khatmiyya is a Sufi order or tariqa founded by Sayyid Mohammed Uthman al-Mirghani al-Khatim.

The Khatmiyya is the largest Sufi order in Sudan, Eritrea and Ethiopia. It also has followers in Egypt, Chad, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, Uganda, Y ...

. Merchants and Arab tribes that had depended on the slave trade responded as well, along with the Hadendoa

Hadendoa (or Hadendowa) is the name of a nomadic subdivision of the Beja people, known for their support of the Mahdiyyah rebellion during the 1880s to 1890s. The area historically inhabited by the Hadendoa lies today in parts of Sudan, Egypt a ...

Beja, who were rallied to the Mahdi by an Ansar captain, Osman Digna

Osman Digna ( ar, عثمان دقنة) (c.1840 – 1926) was a follower of Muhammad Ahmad, the self-proclaimed Mahdi, in Sudan, who became his best known military commander during the Mahdist War. He was claimed to be a descendant from the A ...

.

Advancing attacks

Early in 1882, the Ansar, armed with spears and swords, overwhelmed a British-led 7,000-man Egyptian force not far from Al Ubayyid and seized their rifles, field guns and ammunition. The Mahdi followed up this victory by laying siege to Al Ubayyid and starving it into submission after four months. The Ansar, 30,000 men strong, then defeated an 8,000-man Egyptian relief force at Sheikan. To the west, the Mahdist uprising was able to count on existing resistance movements. The Turkish rule of Darfur had been resented by locals, and several rebels had already begun revolts. Baggara rebels underRizeigat

The Rizeigat, or Rizigat, or Rezeigat (Standard Arabic Rizayqat) are a Muslim and Arab tribe of the nomadic Bedouin Baggara (Standard Arabic Baqqara) people in Sudan's Darfur region. The Rizeigat belong to the greater Baggara Arabs fraternity of ...

chief Madibo pledged themselves to the Mahdi and besieged Darfur's Governor-General Rudolf Carl von Slatin

Major-General Rudolf Anton Carl Freiherr von Slatin, Geh. Rat, (7 June 1857, in Ober Sankt Veit, Hietzing, Vienna – 4 October 1932, in Vienna) was an Anglo-Austrian soldier and administrator in the Sudan.

Early life

Rudolf Carl Slatin was ...

, an Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

n in the khedive's service, at Dara. Slatin was captured in 1883, and more Darfuri tribes consequently joined the revolutionaries. Mahdist forces soon took control of most of Darfur. At first, the regime change was very popular in Darfur.

The advance of the Ansar and the Hadendowa rising in the east imperiled communications with Egypt and threatened to cut off garrisons at Khartoum, Kassala, Sennar

Sennar ( ar, سنار ') is a city on the Blue Nile in Sudan and possibly the capital of the state of Sennar. It remains publicly unclear whether Sennar or Singa is the capital of Sennar State. For several centuries it was the capital of the F ...

, and Suakin

Suakin or Sawakin ( ar, سواكن, Sawákin, Beja: ''Oosook'') is a port city in northeastern Sudan, on the west coast of the Red Sea. It was formerly the region's chief port, but is now secondary to Port Sudan, about north.

Suakin used to b ...

and in the south. To avoid being drawn into a costly military intervention, the British government ordered an Egyptian withdrawal from Sudan. Gordon, who had received a reappointment as governor general, arranged to supervise the evacuation of Egyptian troops and officials and all foreigners from Sudan.

British response

After reaching Khartoum in February 1884, Gordon soon realized that he could not extricate the garrisons. As a result, he called for reinforcements from Egypt to relieve Khartoum. Gordon also recommended that

After reaching Khartoum in February 1884, Gordon soon realized that he could not extricate the garrisons. As a result, he called for reinforcements from Egypt to relieve Khartoum. Gordon also recommended that Zubayr

Az Zubayr ( ar, الزبير) is a city in and the capital of Al-Zubair District, part of the Basra Governorate of Iraq. The city is just south of Basra. The name can also refer to the old Emirate of Zubair.

The name is also sometimes written Al ...

, an old enemy whom he recognized as an excellent military commander, be named to succeed him to give disaffected Sudanese a leader other than the Mahdi to rally behind. London rejected this plan. As the situation deteriorated, Gordon argued that Sudan was essential to Egypt's security and that to allow the Ansar a victory there would invite the movement to spread elsewhere.

Increasing British popular support for Gordon eventually forced Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister i ...

William Gladstone to mobilize a relief force under the command of Lord Garnet Joseph Wolseley. A "flying column

A flying column is a small, independent, military land unit capable of rapid mobility and usually composed of all arms. It is often an ''ad hoc'' unit, formed during the course of operations.

The term is usually, though not necessarily, appli ...

" sent overland from Wadi Halfa across the Bayuda Desert

The Bayuda Desert, located at , is in the eastern region of the Sahara Desert, spanning approximately 100,000 km2 of northeast Sudan north of Omdurman and south of Korti, embraced by the great bend of the Nile in the north, east and south ...

bogged down at Abu Tulayh (commonly called Abu Klea), where the Hadendowa broke the British line. An advance unit that had gone ahead by river when the column reached Al Matammah arrived at Khartoum on 28 January 1885, to find the town had fallen two days earlier. The Ansar had waited for the Nile

The Nile, , Bohairic , lg, Kiira , Nobiin: Áman Dawū is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa and has historically been considered the longest ...

flood to recede before attacking the poorly defended river approach to Khartoum in boats, slaughtering the garrison, killing Gordon, and delivering his head to the Mahdi's tent. Kassala and Sennar fell soon after, and by the end of 1885, the Ansar had begun to move into the southern region. In all Sudan, only Sawakin

Suakin or Sawakin ( ar, سواكن, Sawákin, Beja: ''Oosook'') is a port city in northeastern Sudan, on the west coast of the Red Sea. It was formerly the region's chief port, but is now secondary to Port Sudan, about north.

Suakin used to b ...

, reinforced by Indian army troops, and Wadi Halfa on the northern frontier remained in Anglo-Egyptian hands.

The Mahdists destroyed Khartoum, the city that was built by the Ottomans. All buildings were demolished and ransacked. The women were raped and forced to divorce their "kafir" husbands. It was only after the British came back after about 15 years that the city was rebuilt. By this time no historical buildings, Ottoman style mosques and architecture remained.

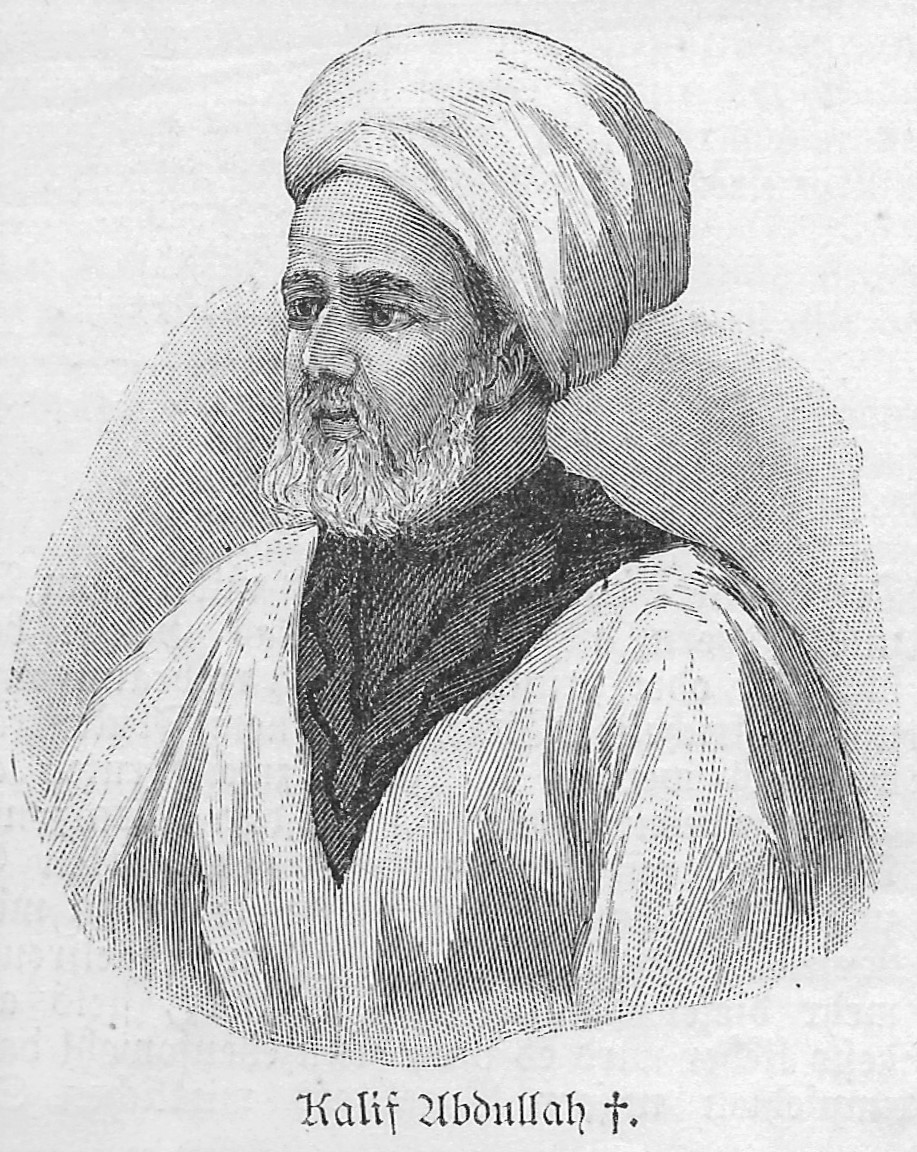

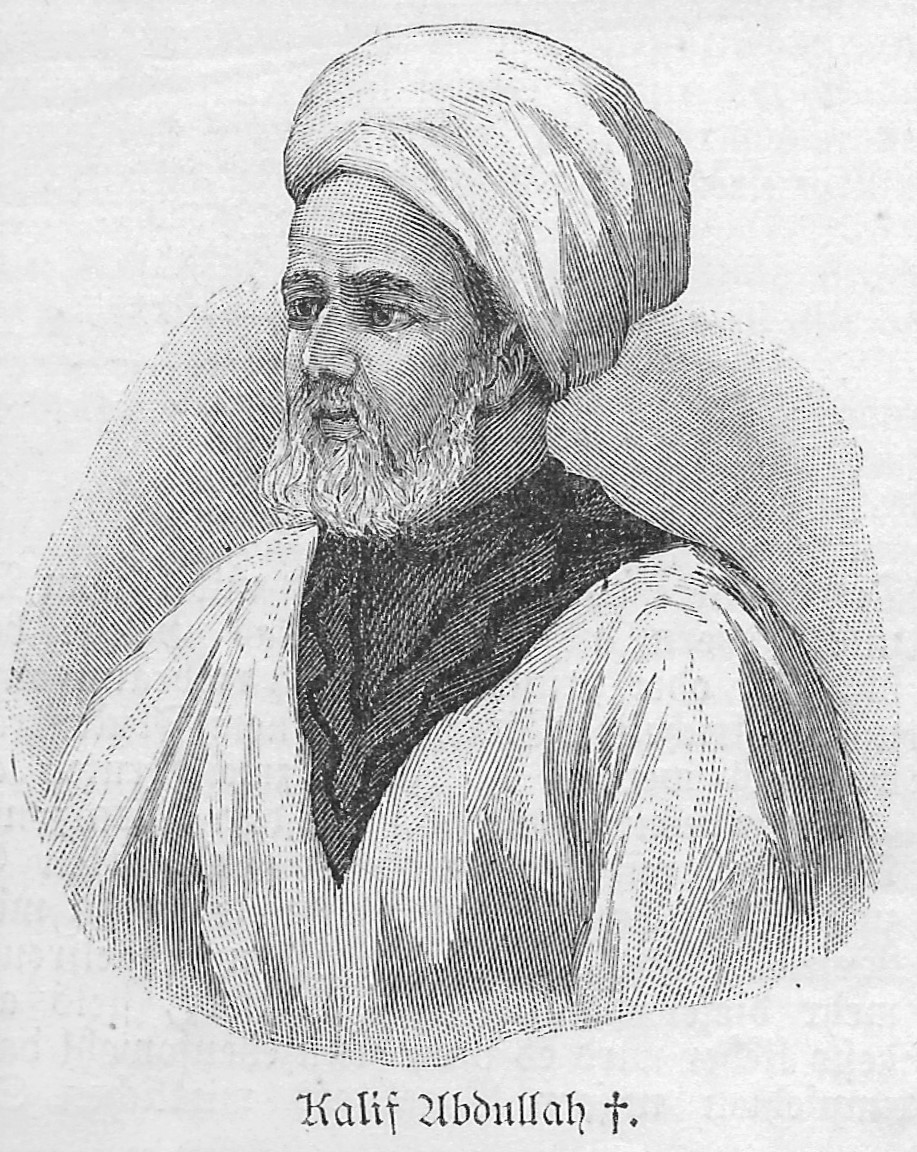

Abdallahi ibn Muhammad

Six months after the capture of Khartoum, the Mahdi died, probably of

Six months after the capture of Khartoum, the Mahdi died, probably of typhus

Typhus, also known as typhus fever, is a group of infectious diseases that include epidemic typhus, scrub typhus, and murine typhus. Common symptoms include fever, headache, and a rash. Typically these begin one to two weeks after exposure. ...

(22 June 1885). The task of establishing and maintaining a government fell to his deputies—three caliphs chosen by the Mahdi in emulation of the Islamic prophet Muhammad

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet divinely inspired to preach and confirm the mo ...

. Rivalry among the three, each supported by people of his native region, continued until 1891, when Abdallahi ibn Muhammad

Abdullah Ibn-Mohammed Al-Khalifa or Abdullah al-Khalifa or Abdallahi al-Khalifa, also known as "The Khalifa" ( ar, c. عبدالله بن سيد محمد الخليفة; 184625 November 1899) was a Sudanese Ansar ruler who was one of the principa ...

, with the help primarily of the Baqqara Arabs, overcame the opposition of the others and emerged as unchallenged leader of the Mahdiyah. Abdallahi—called the Khalifa

Khalifa or Khalifah (Arabic: خليفة) is a name or title which means "successor", "ruler" or "leader". It most commonly refers to the leader of a Caliphate, but is also used as a title among various Islamic religious groups and others. Khalif ...

(successor)—purged the Mahdiyah of members of the Mahdi's family and many of his early religious disciples.

Originally, the Mahdiyah functioned as a jihad state, run like a military camp. Sharia courts enforced Islamic law and the Mahdi's precepts, which had the force of law. After consolidating his power, the Khalifa instituted an administration and appointed Ansar (who were usually Baqqara) as amirs over each of the several provinces. The Khalifa also ruled over rich Al Jazirah. Although he failed to restore this region's commercial wellbeing, the Khalifa organized workshops to manufacture ammunition and to maintain river steamboats.

Regional relations remained tense throughout much of the Mahdiyah period, largely because of the Khalifa's commitment to using jihad to extend his version of Islam throughout the world. For example, the Khalifa rejected an offer of an alliance against the Europeans by Emperor

An emperor (from la, imperator, via fro, empereor) is a monarch, and usually the sovereignty, sovereign ruler of an empire or another type of imperial realm. Empress, the female equivalent, may indicate an emperor's wife (empress consort), ...

Yohannes IV of Ethiopia

''girmāwī''His Imperial Majesty, spoken= am , ጃንሆይ ''djānhoi''Your Imperial Majesty(lit. "O steemedroyal"), alternative= am , ጌቶቹ ''getochu''Our Lord (familiar)(lit. "Our master" (pl.)) yohanes

Yohannes IV (Tigrinya: ዮሓ� ...

(reigned 1871–1889). In 1887, a 60,000-man Ansar army invaded Ethiopia, penetrated as far as Gondar

Gondar, also spelled Gonder (Amharic: ጎንደር, ''Gonder'' or ''Gondär''; formerly , ''Gʷandar'' or ''Gʷender''), is a city and woreda in Ethiopia. Located in the North Gondar Zone of the Amhara Region, Gondar is north of Lake Tana on t ...

, and captured prisoners and booty. The Khalifa then refused to conclude peace with Ethiopia. In March 1889, an Ethiopian force, commanded by the emperor, marched on Metemma

Metemma ( Amharic: መተማ), also known as Metemma Yohannes is a town in northwestern Ethiopia, on the border with Sudan. Located in the Semien Gondar Zone of the Amhara Region, Metemma has a latitude and longitude of with an elevation of 68 ...

; however, after Yohannes fell in the ensuing Battle of Gallabat, the Ethiopians withdrew. Overall, the war with Ethiopia mostly wasted the Mahdists' resources. Abd ar Rahman an Nujumi, the Khalifa's best general, invaded Egypt in 1889, but British-led Egyptian troops defeated the Ansar at Tushkah. The failure of the Egyptian invasion ended the myth of the Ansars' invincibility. The Belgian

Belgian may refer to:

* Something of, or related to, Belgium

* Belgians, people from Belgium or of Belgian descent

* Languages of Belgium, languages spoken in Belgium, such as Dutch, French, and German

*Ancient Belgian language, an extinct languag ...

s prevented the Mahdi's men from conquering Equatoria, and in 1893, the Italians repulsed an Ansar attack at Akordat (in Eritrea) and forced the Ansar to withdraw from Ethiopia.

As the Mahdist government became more stable and well-organized, it began to implement taxes and implement its policies throughout its territories. This negatively impacted its popularity in much of Sudan, as many locals had joined the Mahdists to gain autonomy while removing a centralist and oppressive government. In Darfur, rebellions against Abdallahi ibn Muhammad's rule broke out because he was ordering Darfurians to migrate north to better defend the Mahdist State, while favoring the Baggara over other Darfurian ethnicities in regards to government positions. The main resistance was led by religious leader Abu Jimeiza of the Tama tribe in western Darfur. The opposition to the Mahdist government was also fuelled by many Mahdists behaving arrogantly and abusive towards the locals. Several states bordering the Mahdist State to the west began to provide the Darfurian rebels with troops and other support. Faced with a growing number of rebels, the Mahdist rule in Darfur gradually collapsed. The Mahdist era became known as the ''umkowakia'' in Darfur — the "period of chaos and anarchy".

Anglo-Egyptian reconquest of Sudan

Charging Mahdist army In 1892,Herbert Kitchener

Horatio Herbert Kitchener, 1st Earl Kitchener, (; 24 June 1850 – 5 June 1916) was a senior British Army officer and colonial administrator. Kitchener came to prominence for his imperial campaigns, his scorched earth policy against the Boers, h ...

(later Lord Kitchener) became sirdar

The rank of Sirdar ( ar, سردار) – a variant of Sardar – was assigned to the British Commander-in-Chief of the British-controlled Egyptian Army in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The Sirdar resided at the Sirdaria, a three-blo ...

, or commander, of the Egyptian army and started preparations for the reconquest of Sudan. The British thought they needed to occupy Sudan in part because of international developments. By the early 1890s, British, French, and Belgian claims had converged at the Nile headwaters. Britain feared that the other colonial powers would take advantage of Sudan's instability to acquire territory previously annexed to Egypt. Apart from these political considerations, Britain wanted to establish control over the Nile to safeguard a planned irrigation dam at Aswan.

In 1895, the British government authorized Kitchener to launch a campaign to reconquer Sudan. Britain provided men and matériel while Egypt financed the expedition. The Anglo-Egyptian Nile Expeditionary Force included 25,800 men, 8,600 of whom were British. The remainder were troops belonging to Egyptian units that included six battalions recruited in southern Sudan. An armed river flotilla escorted the force, which also had artillery support. In preparation for the attack, the British established an army headquarters at the former rail head Wadi Halfa and extended and reinforced the perimeter defenses around Sawakin. In March 1896, the campaign started as the Dongola Expedition

The Mahdist War ( ar, الثورة المهدية, ath-Thawra al-Mahdiyya; 1881–1899) was a war between the Mahdist Sudanese of the religious leader Muhammad Ahmad bin Abd Allah, who had proclaimed himself the "Mahdi" of Islam (the "Guided O ...

. Despite taking the time to reconstruct Ishma'il Pasha's former gauge railway south along the east bank of the Nile, Kitchener captured the former capital of Nubia

Nubia () (Nobiin: Nobīn, ) is a region along the Nile river encompassing the area between the first cataract of the Nile (just south of Aswan in southern Egypt) and the confluence of the Blue and White Niles (in Khartoum in central Sudan), or ...

by September.Gleichen, Edward ed. The Anglo-Egyptian Sudan: A Compendium Prepared by Officers of the Sudan Government

', Vol. 1, p. 99. Harrison & Sons (London), 1905. Accessed 13 Feb 2014. The next year, the British then constructed a new rail line directly across the desert from Wadi Halfa to Abu Hamad,Sudan Railway Corporation.

Historical Background

". 2008. Accessed 13 Feb 2014. which they captured in the

Battle of Abu Hamed

The Battle of Abu Hamed occurred on 7 August 1897 between a flying column of Anglo-Egyptian soldiers under Major-General Sir Archibald Hunter and a garrison of Mahdist rebels led by Mohammed Zain. The battle was a victory for the Anglo-Egypti ...

on 7 August 1897. (The gauge, hastily adopted to make use of available rolling stock, meant supplies from the Egyptian network required transshipment via steamer from Asyut

AsyutAlso spelled ''Assiout'' or ''Assiut'' ( ar, أسيوط ' , from ' ) is the capital of the modern Asyut Governorate in Egypt. It was built close to the ancient city of the same name, which is situated nearby. The modern city is located at ...

to Wadi Halfa. The Sudanese system retains the incompatible gauge to this day.) Anglo-Egyptian units fought a sharp action at Abu Hamad, but there was little other significant resistance until Kitchener reached Atbarah and defeated the Ansar. After this engagement, Kitchener's soldiers marched and sailed toward Omdurman, where the Khalifa made his last stand.

On 2 September 1898, the Khalifa committed his 52,000-man army to a frontal assault against the Anglo-Egyptian force, which was massed on the plain outside Omdurman. The outcome was never in doubt, largely because of superior British firepower. During the five-hour battle, about 11,000 Mahdists died, whereas Anglo-Egyptian losses amounted to 48 dead and fewer than 400 wounded.

Mopping-up operations required several years, but organized resistance ended when the Khalifa, who had escaped to Kordufan, died in fighting at Umm Diwaykarat in November 1899. Although the Khalifa had retained considerable support until his death, many areas welcomed the downfall of his regime. Sudan's economy had been all but destroyed during his reign and the population had declined by approximately one-half because of famine, disease, persecution, and warfare. Millions had died in Sudan from the foundation of the Mahdist state to its fall. Moreover, none of the country's traditional institutions or loyalties remained intact. Tribes had been divided in their attitudes toward Mahdism, religious brotherhoods had been weakened, and orthodox religious leaders had vanished.

Holdouts

Even though the Mahdist State factually ceased to exist after Umm Diwaykarat, some Mahdist holdouts continued to persist. One officer,Osman Digna

Osman Digna ( ar, عثمان دقنة) (c.1840 – 1926) was a follower of Muhammad Ahmad, the self-proclaimed Mahdi, in Sudan, who became his best known military commander during the Mahdist War. He was claimed to be a descendant from the A ...

, continued to resist the Anglo-Egyptian forces until captured in January 1900.

However, the most long-lasting Mahdist holdouts actually survived in Darfur, despite the fact that Mahdist rule had already been collapsing there before the Anglo-Egyptian reconquest. The holdouts were concentrated at Kabkabiya (led by Sanin Husain), Dar Taaisha (led by Arabi Dafalla), and Dar Masalit (led by Sultan Abuker Ismail). The reestablished Sultanate of Darfur

The Sultanate of Darfur was a pre-colonial state in present-day Sudan. It existed from 1603 to October 24, 1874, when it fell to the Sudanese warlord Rabih az-Zubayr and again from 1898 to 1916, when it was conquered by the British and integr ...

consequently had to crush the Mahdist loyalists in a series of lengthy wars. The Kabkabiya holdout under Sanin Husain persisted until 1909, when it was destroyed by the Sultanate of Darfur after a siege of 17 or 18 months.

The Mahdiyah

The Mahdiyah (Mahdist regime) imposed traditional ShariaIslamic law

Sharia (; ar, شريعة, sharīʿa ) is a body of religious law that forms a part of the Islamic tradition. It is derived from the religious precepts of Islam and is based on the sacred scriptures of Islam, particularly the Quran and the ...

s. The state's administration was first properly organized under Khalifa Abdallahi ibn Muhammad who attempted to use the Islamic law to unify the different peoples of Sudan.

Sudan's new ruler also authorized the burning of lists of pedigrees and books of law and theology because of their association with the old order and because he believed that the former accentuated tribalism at the expense of religious unity.

The Mahdiyah has become known as the first genuine Sudanese nationalist government. The Mahdi maintained that his movement was not a religious order that could be accepted or rejected at will, but that it was a universal regime, which challenged man to join or to be destroyed. The Mahdi modified Islam's five pillars to support the dogma that loyalty to him was essential to true belief. The Mahdi also added the declaration "and Muhammad Ahmad is the Mahdi of God and the representative of His Prophet" to the recitation of the creed, the shahada

The ''Shahada'' ( Arabic: ٱلشَّهَادَةُ , "the testimony"), also transliterated as ''Shahadah'', is an Islamic oath and creed, and one of the Five Pillars of Islam and part of the Adhan. It reads: "I bear witness that there i ...

. Moreover, service in the jihad replaced the hajj, or pilgrimage to Mecca

Mecca (; officially Makkah al-Mukarramah, commonly shortened to Makkah ()) is a city and administrative center of the Mecca Province of Saudi Arabia, and the holiest city in Islam. It is inland from Jeddah on the Red Sea, in a narrow ...

, as a duty incumbent on the faithful. Zakat

Zakat ( ar, زكاة; , "that which purifies", also Zakat al-mal , "zakat on wealth", or Zakah) is a form of almsgiving, often collected by the Muslim Ummah. It is considered in Islam as a religious obligation, and by Quranic ranking, is ...

(almsgiving) became the tax paid to the state. The Mahdi justified these and other innovations and reforms as responses to instructions conveyed to him by God in visions.

The Mahdist regime was also known for its severe persecution of Christians

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words '' Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρ ...

in Sudan, including Copts.Minority Rights Group International

Minority Rights Group International (MRG) is an international human rights organisation founded with the objective of working to secure rights for ethnic, national, religious, linguistic minorities and indigenous peoples around the world. Thei ...

, World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous Peoples - Sudan : Copts, 2008, available at: http://www.unhcr.org/refworld/docid/49749ca6c.html ccessed 21 December 2010/ref>

Military

Army

The Mahdist State had a large military which became increasingly professional as time went on. From an early point, the Mahdist armies recruited defectors from the Egyptian Army and organized professional soldiers in the form of the ''jihadiya'', mostly Black Sudanese. These were supported by tribal spearmen and swordsmen as well as cavalry. The ''jihadiya'' and some tribal units lived in military barracks, while the rest were more akin to militia. The Mahdist armies also possessed limited artillery, including mountain guns and even machine guns. However, these were few in numbers, and thus only used as defenses for important towns and to the river steamers that acted as the state's navy. In general, the Mahdist armies were highly motivated by their belief system. Exploiting this, the Mahdist commanders used their riflemen to screen charges by their melee infantry and cavalry. Such attacks often proved effective, but also led to extremely high losses when employed "unimaginatively". The Europeans generally called the Mahdist soldiers "dervishes".

Muhammad Ahmad's early insurgent force which was mostly recruited among the poor Arab communities living at the Nile. The later armies of the Mahdiyah were recruited among various groups, including mostly autonomous groups such as the

The Mahdist State had a large military which became increasingly professional as time went on. From an early point, the Mahdist armies recruited defectors from the Egyptian Army and organized professional soldiers in the form of the ''jihadiya'', mostly Black Sudanese. These were supported by tribal spearmen and swordsmen as well as cavalry. The ''jihadiya'' and some tribal units lived in military barracks, while the rest were more akin to militia. The Mahdist armies also possessed limited artillery, including mountain guns and even machine guns. However, these were few in numbers, and thus only used as defenses for important towns and to the river steamers that acted as the state's navy. In general, the Mahdist armies were highly motivated by their belief system. Exploiting this, the Mahdist commanders used their riflemen to screen charges by their melee infantry and cavalry. Such attacks often proved effective, but also led to extremely high losses when employed "unimaginatively". The Europeans generally called the Mahdist soldiers "dervishes".

Muhammad Ahmad's early insurgent force which was mostly recruited among the poor Arab communities living at the Nile. The later armies of the Mahdiyah were recruited among various groups, including mostly autonomous groups such as the Beja people

The Beja people ( ar, البجا, Beja: Oobja, tig, በጃ) are an ethnic group native to the Eastern Desert, inhabiting a coastal area from southeastern Egypt through eastern Sudan and into northwestern Eritrea. They are descended from pe ...

. The early forces of the Mahdi were termed the "ansar", and divided into three units led by a Khalifa. These units were termed ''raya'' ("flags") in accordance to their standards. The "Black Flag" was mostly recruited from western Sudanese, mainly Baggara, and commanded by Abdallahi ibn Muhammad. The "Red Flag" was led by Muhammad al-Sharif and mostly consisted of riverine recruits from the north. The "Green Flag" under Ali Hilu included troops drawn from the southern tribes living between the White and Blue Nile. After the Mahdi's death, the command of the "Black Flag" was passed to Abdallahi ibn Muhammad's brother Yaqub and became the state's main army, based at the capital Omdurman. As the Mahdist State expanded, provincial commanders raised new armies with separate standards which were modelled on the main armies. The most elite forces within the Mahdist armies were the ''Mulazimiyya'', Abdallahi ibn Muhammad's bodyguards. Commanded by Uthman Shaykh al-Din, these were based at the capital and 10,000 strong, most armed with rifles.

The "flags" were further divided into ''rubs'' ("quarters") consisting of 800 to 1200 fighters. In turn, ''rubs'' were split into four sections, one administrative, one ''jihadiya'', one sword- and spear-wielding infantry, and one cavalry. The ''jihadiya'' units were further split into "standards" of 100 led by officers known as ''ra's mi'a'', and into ''muqaddamiyya'' of 25 under ''muqaddam''.

Navy

The Mahdist navy emerged during the early rebellion, as the insurgents took control of boats operating on the Nile. In May 1884, the Mahdists captured the steamboats ''Fasher'' and ''Musselemieh'', followed by the ''Muhammed Ali'' and ''Ismailiah''. In addition, several armed steamboats which had been supposed to aid Charles Gordon's besieged force were wrecked and abandoned in 1885. At least two of these, the ''Bordein'' and ''Safia'', were salvaged by the Mahdists. The captured steamboats were armed with light artillery pieces, and crewed by Egyptians as well as Sudanese. The Mahdist navy also used supply ships.

In October 1898, parts of the Mahdist navy were sent up the White Nile to assist the expedition against Emin Pasha's forces. The ''Ismailiah'' was sunk on 17 August 1898 as it was placing

The Mahdist navy emerged during the early rebellion, as the insurgents took control of boats operating on the Nile. In May 1884, the Mahdists captured the steamboats ''Fasher'' and ''Musselemieh'', followed by the ''Muhammed Ali'' and ''Ismailiah''. In addition, several armed steamboats which had been supposed to aid Charles Gordon's besieged force were wrecked and abandoned in 1885. At least two of these, the ''Bordein'' and ''Safia'', were salvaged by the Mahdists. The captured steamboats were armed with light artillery pieces, and crewed by Egyptians as well as Sudanese. The Mahdist navy also used supply ships.

In October 1898, parts of the Mahdist navy were sent up the White Nile to assist the expedition against Emin Pasha's forces. The ''Ismailiah'' was sunk on 17 August 1898 as it was placing naval mine

A naval mine is a self-contained explosive device placed in water to damage or destroy surface ships or submarines. Unlike depth charges, mines are deposited and left to wait until they are triggered by the approach of, or contact with, any ...

s on the Nile near Omdurman to block the advance of Anglo-British gunboats. One mine accidentally exploded, destroying the ship. The ''Safia'' and ''Tawfiqiyeh'', towing barges with 2,000 to 3,000 soldiers, were sent up the Blue Nile

The Blue Nile (; ) is a river originating at Lake Tana in Ethiopia. It travels for approximately through Ethiopia and Sudan. Along with the White Nile, it is one of the two major tributaries of the Nile and supplies about 85.6% of the water to ...

against French forces holding Fashoda

Kodok or Kothok ( ar, كودوك), formerly known as Fashoda, is a town in the north-eastern South Sudanese state of Upper Nile State. Kodok is the capital of Shilluk country, formally known as the Shilluk Kingdom. Shilluk had been an independ ...

on 25 August 1898. There, the two ships attacked the fort, but the ''Safia'' broke down and was exposed to heavy fire before being towed to safety by the ''Tawfiqiyeh''. The ''Tawfiqiyeh'' subsequently retreated to Omdurman, but encountered a large Anglo-Egyptian fleet on the way and surrendered. The Mahdist navy fought its last battle on 11 or 15 September 1898, when the Anglo-Egyptian gunboat ''Sultan'' encountered the ''Safia'' near Reng. The two ships fought a short battle, and the ''Safia'' was badly damaged before being boarded and captured. The ''Bordein'' was eventually captured when Omdurman fell to the Anglo-Egyptian forces.

Uniform

At the start of his insurgency, the Mahdi encouraged his followers to wear similar clothing in form of the ''jibba

The ''jibba'' or ''jibbah'' ( ar, جبة, romanized: ''jubbā''), originally referring to an outer garment, cloak or coat,) is a long coat worn by Muslim men. During the Mahdist State in Sudan at the end of the 19th century, it was the garment ...

''. As a result, the core army of the Mahdi and Abdallahi ibn Muhammad had a relatively regulated appearance from an early point. In contrast, other armies of supporters and allies initially did not adopt the ''jibba'' and maintained their traditional appearances. Riverine forces recruited from the Ja'alin tribe

The Ja'alin, Ja'aliya, Ja'aliyin or Ja'al ( ar, جعليون) are an Arab or Arabised Nubian tribe in Sudan. The Ja'alin constitute a large portion of the Sudanese Arabs and are one of the three prominent Sudanese Arab tribes in northern Sudan - ...

and the Danagla The Danagla (, "People of Dongola") are a tribe in northern Sudan of partial Arab

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Ar ...

mostly wore simple white robes (''tobe''). The Beja also did not adopt the ''jibba'' until 1885.

As time went on and the Mahdist State became better organized under Khalifa Abdallahi ibn Muhammad's leadership, its armies became more and more professional. By the 1890s factories in Omdurman and provincial centers were mass-producing ''jibba'' to provide the troops with clothing. Although the ''jibba'' still varied in their style, with certain tribes and armies favoring certain patterns and colors, the Mahdist forces became increasingly professional in appearance. The ''jibba'' also indicated a fighter's rank within the Mahdist armies. Lower-ranking commanders (''emirs'') wore more colorful and elaborate ''jibba''. The most senior military leadership preferred the most simple designs, however, to indicate their piety. The Khalifa wore plain white. Some Mahdist troops possessed mail armour, helmets, and quilted coats, although these were more often used in parades than in combat. One unit within the Mahdist armies, the ''Mulazimiyya'', adopted a full uniform, as all their members wore identical white-red-blue ''jibba''.

Flags

The Mahdist State and its armies had no uniform flags, but still used certain designs repeatedly. Most flags carried four lines of Arabic texts which signified allegiance to God, Muhammad, and the Mahdi. The flags were usually white with colored borders, and the text displayed in varying colors. Most military units had their own individual flags.See also

*History of Sudan

The history of Sudan refers to both the territory of the Republic of the Sudan, including what became in 2011 the independent state of South Sudan. The territory of Sudan is geographically part of a larger African region, also known by the te ...

* Mahdist War

*''In Desert and Wilderness

''In Desert and Wilderness'' ( pl, W pustyni i w puszczy) is a popular young adult novel by the Polish author and Nobel Prize-winning novelist Henryk Sienkiewicz, written in 1911. It is the author's only novel written for children/teenagers. It ...

'' (novel)

* Millennarianism in colonial societies

Notes

References

Works cited

* * * * * * *Further reading

*Fadlalla, Mohamed H. ''Short History of Sudan'', iUniverse, 30 April 2004, *Holt, P. M. "The Mahdia in the Sudan, 1881-1898" ''History Today'' (Mar 1958) 8#3 pp 187–195. * * * * * * * {{Authority controlMahdist Sudan

The Mahdist State, also known as Mahdist Sudan or the Sudanese Mahdiyya, was a state based on a religious and political movement launched in 1881 by Muhammad Ahmad bin Abdullah (later Muhammad al-Mahdi) against the Khedivate of Egypt, which had ...

Mahdist Sudan

The Mahdist State, also known as Mahdist Sudan or the Sudanese Mahdiyya, was a state based on a religious and political movement launched in 1881 by Muhammad Ahmad bin Abdullah (later Muhammad al-Mahdi) against the Khedivate of Egypt, which had ...

Mahdist

Islamic states

Mahdist War

1885 establishments in Africa

1899 disestablishments in Africa

States and territories established in 1885

States and territories disestablished in 1899

Former countries

Former theocracies

sw:Dola la Mahdi

pl:Powstanie Mahdiego w Sudanie