The

U.S. state of

Kansas

Kansas () is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern United States. Its Capital city, capital is Topeka, Kansas, Topeka, and its largest city is Wichita, Kansas, Wichita. Kansas is a landlocked state bordered by Nebras ...

, located on the eastern edge of the

Great Plains

The Great Plains (french: Grandes Plaines), sometimes simply "the Plains", is a broad expanse of flatland in North America. It is located west of the Mississippi River and east of the Rocky Mountains, much of it covered in prairie, steppe, a ...

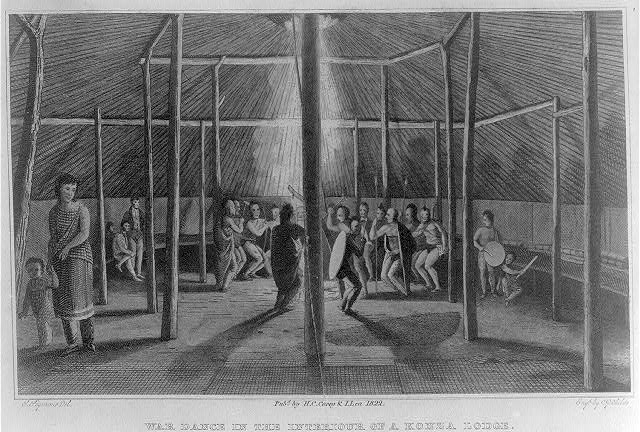

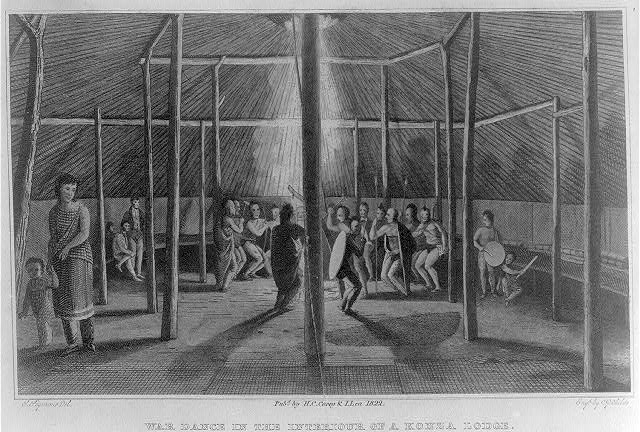

, was the home of nomadic

Native American tribes who hunted the vast herds of

bison (often called "buffalo"). In around 1450 AD, the Wichita People founded the great city of

Etzanoa. The city of Etzanoa was abandoned in around 1700 AD. The region was explored by Spanish

conquistador

Conquistadors (, ) or conquistadores (, ; meaning 'conquerors') were the explorer-soldiers of the Spanish and Portuguese Empires of the 15th and 16th centuries. During the Age of Discovery, conquistadors sailed beyond Europe to the Americas, ...

es in the 16th century. It was later explored by French

fur trappers who traded with the Native Americans. Most of Kansas became permanently part of the United States in the

Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase (french: Vente de la Louisiane, translation=Sale of Louisiana) was the acquisition of the territory of Louisiana by the United States from the French First Republic in 1803. In return for fifteen million dollars, or ap ...

of 1803. When the area was opened to settlement by the

Kansas–Nebraska Act

The Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854 () was a territorial organic act that created the territories of Kansas and Nebraska. It was drafted by Democratic Senator Stephen A. Douglas, passed by the 33rd United States Congress, and signed into law ...

of 1854 it became a battlefield that helped cause the

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

. Settlers from North and South came in order to vote slavery down or up. The free state element prevailed.

After the war, Kansas was home to

frontier towns; their railroads were destinations for cattle drives from Texas. With the railroads came heavy immigration from the East, from Germany as well as some

freedmen

A freedman or freedwoman is a formerly enslaved person who has been released from slavery, usually by legal means. Historically, enslaved people were freed by manumission (granted freedom by their captor-owners), emancipation (granted freedom ...

called "

Exodusters

Exodusters was a name given to African Americans who migrated from states along the Mississippi River to Kansas in the late nineteenth century, as part of the Exoduster Movement or Exodus of 1879. It was the first general migration of black pe ...

". Farmers first tried to replicate Eastern patterns and grow corn and raise pigs, but they failed because of shortages of rainfall. The solution, as

James Malin showed, was to switch to soft spring wheat and later to hard winter wheat. The wheat was exported to Europe and was subject to wide variations in price. Many frustrated farmers joined the Populist movement around 1890, but conservative townspeople finally prevailed politically. They supported the progressive movement down to about 1940, but isolationism in foreign affairs combined with prosperity for the farmers and townsfolk made the state a center of conservative support for the Republican Party since 1940. Since 1945 the farm population has sharply declined and manufacturing has become more important, typified by the aircraft industry of

Wichita.

Prehistory

The Paleo-Indians and Archaic peoples

Around 7000 BC, paleolithic descendants of Asian immigrants into North America reached Kansas. Once in Kansas, the indigenous ancestors never abandoned Kansas. They were later augmented by other indigenous peoples migrating from other parts of the continent. These bands of newcomers encountered

mammoth

A mammoth is any species of the extinct elephantid genus ''Mammuthus'', one of the many genera that make up the order of trunked mammals called proboscideans. The various species of mammoth were commonly equipped with long, curved tusks an ...

s, camels,

ground sloths, and horses. The sophisticated

big-game hunters did not keep a balance, resulting in the "Pleistocene overkill", the rapid and systematic destruction of nearly all the species of large ice-age mammals in North America by 8000 BC. The hunters who pursued the mammoths may have represented the first of north Great Plains cycles of boom and bust, relentlessly exploiting the resource until it has been depleted or destroyed.

[Frank H. Gille, ed. ''Encyclopedia of Kansas Indians Tribes, Nations and People of the Plains'' (1999)]

After the disappearance of big-game hunters, some archaic groups survived by becoming generalists rather than specialists, foraging in seasonal movements across the plains. The groups did not abandon hunting altogether, but also consumed wild plant foods and small game. Their tools became more varied, with grinding and chopping implements becoming more common, a sign that seeds, fruits, and greens constituted a greater proportion of their diet. Also, pottery-making societies emerged.

Introduction of agriculture

For most of the Archaic period, people did not transform their natural environment in any fundamental way. The groups outside the region, particularly in

Mesoamerica

Mesoamerica is a historical region and cultural area in southern North America and most of Central America. It extends from approximately central Mexico through Belize, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, and northern Costa Rica. Wit ...

, introduced major innovations, such as maize cultivation. Other groups in North America independently developed maize cultivation as well. Some archaic groups transferred from food gatherers to food producers around 3,000 years ago. They also possessed many of the cultural features that accompany semi-sedentary agricultural life: storage facilities, more permanent dwellings, larger settlements, and cemeteries or burial grounds.

El Cuartelejo was the northernmost Indian

pueblo. This settlement is the only pueblo in Kansas from which archaeological evidence has been recovered.

Despite the early advent of farming, late Archaic groups still exercised little control over their natural environment. Wild food resources remained important components of their diet even after the invention of pottery and the development of irrigation. The introduction of agriculture never resulted in the complete abandonment of hunting and foraging, even in the largest of Archaic societies.

Etzanoa

Etzanoa is an ancient city, that was founded by the

Wichita people in about 1450. Etzanoa is located in present-day

Arkansas City, Kansas, near the

Arkansas River

The Arkansas River is a major tributary of the Mississippi River. It generally flows to the east and southeast as it traverses the U.S. states of Colorado, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Arkansas. The river's source basin lies in the western United ...

.

In 1601, Juan de Oñate visited the city of Etzanoa. Oñate and the other explorers who accompanied him called the city "the Great Settlement". Etzanoa may have been home to about 20,000 people at the time Oñate and his expedition found and explored the city.

Early European exploration and local tribes

In 1541,

Francisco Vázquez de Coronado, the Spanish conquistador, visited Kansas, allegedly turning back near "

Coronado Heights" in present-day Lindsborg. Near the Great Bend of the

Arkansas River

The Arkansas River is a major tributary of the Mississippi River. It generally flows to the east and southeast as it traverses the U.S. states of Colorado, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Arkansas. The river's source basin lies in the western United ...

, in a place he called ''

Quivira'', he met the ancestors of the

Wichita people. Near the Smoky Hill River, he met the ''Harahey,'' who were probably the ancestors of the

Pawnee. This was the first time that the

Plains Indians

Plains Indians or Indigenous peoples of the Great Plains and Canadian Prairies are the Native American tribes and First Nation band governments who have historically lived on the Interior Plains (the Great Plains and Canadian Prairies) of ...

had seen horses. Later, they acquired horses from the Spanish, and rapidly radically altered their lifestyle and range.

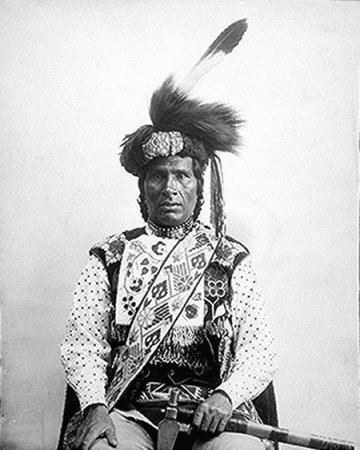

Following this transformation, the

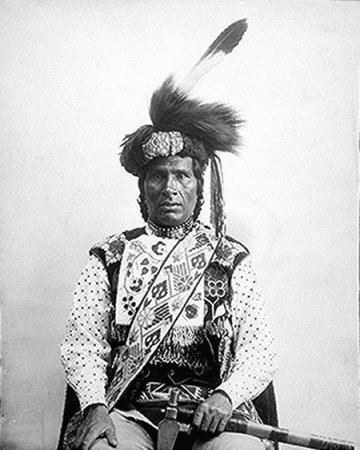

Kansa (sometimes Kaw) and

Osage Nation (originally Ouasash) arrived in Kansas in the 17th century. (The Kansa claimed that they occupied the territory since 1673.) By the end of the 18th century, these two tribes were dominant in the eastern part of the future state: the Kansa on the

Kansas River to the North and the Osage on the

Arkansas River

The Arkansas River is a major tributary of the Mississippi River. It generally flows to the east and southeast as it traverses the U.S. states of Colorado, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Arkansas. The river's source basin lies in the western United ...

to the South. At the same time, the

Pawnee (sometimes Paneassa) were dominant on the plains to the west and north of the Kansa and Osage nations, in regions home to massive herds of bison. Europeans visited the Northern Pawnee in 1719. In 1720, the Spanish military's

Villasur expedition

The Villasur expedition of 1720 was a Spanish military expedition intended to check New France's growing influence on the North American Great Plains, led by Lieutenant-General Pedro de Villasur. Pawnee and Otoe Indians attacked the expedition ...

was wiped out by

Pawnee and

Otoe warriors near present-day

Columbus, Nebraska, effectively ending Spanish expedition into the region. The French commander at

Fort Orleans

Fort Orleans (sometimes referred to Fort D'Orleans) was a French fort in colonial North America, the first fort built by any European forces on the Missouri River. It was built near the mouth of the Grand River near present-day Brunswick. Inte ...

,

Étienne de Bourgmont, visited the

Kansas River in 1724 and established a trading post there, near the main Kansa village at the mouth of the river. Around the same time, the

Otoe tribe

The Otoe (Chiwere: Jiwére) are a Native American people of the Midwestern United States. The Otoe language, Chiwere, is part of the Siouan family and closely related to that of the related Iowa, Missouria, and Ho-Chunk tribes.

Historically, t ...

of the

Sioux also inhabited various areas around the northeast corner of Kansas.

Louisiana Purchase

Apart from brief explorations, neither France nor Spain had any settlement or military or other activity in Kansas. In 1763, following the

Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (1754 ...

in which Great Britain defeated France, Spain acquired the French claims west of the Mississippi River. It returned this territory to France in 1803, keeping title to about .

In the

Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase (french: Vente de la Louisiane, translation=Sale of Louisiana) was the acquisition of the territory of Louisiana by the United States from the French First Republic in 1803. In return for fifteen million dollars, or ap ...

of 1803, the United States (US) acquired all of the French claims west of the Mississippi River; the area of Kansas was

unorganized territory. In 1819 the United States confirmed Spanish rights to the as part of the

Adams–Onís Treaty

The Adams–Onís Treaty () of 1819, also known as the Transcontinental Treaty, the Florida Purchase Treaty, or the Florida Treaty,Weeks, p.168. was a treaty between the United States and Spain in 1819 that ceded Florida to the U.S. and define ...

with Spain. That area became part of Mexico, which also ignored it. After the

Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the ...

and the US victory, the United States took over that part in 1848.

The

Lewis and Clark Expedition

The Lewis and Clark Expedition, also known as the Corps of Discovery Expedition, was the United States expedition to cross the newly acquired western portion of the country after the Louisiana Purchase. The Corps of Discovery was a select gr ...

left

St. Louis on a mission to explore the Louisiana Purchase all the way to the Pacific Ocean. In 1804, Lewis and Clark camped for three days at the

confluence

In geography, a confluence (also: ''conflux'') occurs where two or more flowing bodies of water join to form a single channel. A confluence can occur in several configurations: at the point where a tributary joins a larger river (main stem); o ...

of the Kansas and Missouri rivers in what is today

Kansas City, Kansas (today commemorated at the

Kaw Point Riverfront Park). They met French fur traders and mapped the area. In 1806,

Zebulon Pike

Zebulon Montgomery Pike (January 5, 1779 – April 27, 1813) was an American brigadier general and explorer for whom Pikes Peak in Colorado was named. As a U.S. Army officer he led two expeditions under authority of President Thomas Jefferson ...

passed through Kansas and labeled it "the

Great American Desert" on his maps. This view of Kansas would help form U.S. policy for the next 40 years, prompting the government to set it aside as land reserved for Native American resettlement.

From June 4, 1812 until August 10, 1821 the area that would become

Kansas Territory 33 years later was part of the

Missouri Territory. When Missouri was granted statehood in 1821 the area became unorganized territory and contained few if any permanent white settlers, except

Fort Leavenworth

Fort Leavenworth () is a United States Army installation located in Leavenworth County, Kansas, in the city of Leavenworth. Built in 1827, it is the second oldest active United States Army post west of Washington, D.C., and the oldest perma ...

. The Fort was established in 1827 by

Henry Leavenworth with the

3rd U.S Infantry from

St. Louis, Missouri; it is the first permanent European settlement in Kansas. The fort was established as the westernmost outpost of the American military to protect trade along the

Santa Fe Trail

The Santa Fe Trail was a 19th-century route through central North America that connected Franklin, Missouri, with Santa Fe, New Mexico. Pioneered in 1821 by William Becknell, who departed from the Boonslick region along the Missouri River, ...

from

Native Americans. The trade came from the East, by land using the

Boone's Lick Road, or by water via the

Missouri River. This area, called the

Boonslick, was located due east in west-central Missouri and was settled by Upland Southerners from Virginia, Kentucky, and Tennessee as early as 1812. Its slave-owning population would contrast with settlers from New England who would eventually arrive in the 1850s.

A section of the

Santa Fe Trail

The Santa Fe Trail was a 19th-century route through central North America that connected Franklin, Missouri, with Santa Fe, New Mexico. Pioneered in 1821 by William Becknell, who departed from the Boonslick region along the Missouri River, ...

through Kansas was used by emigrants on the

Oregon Trail

The Oregon Trail was a east–west, large-wheeled wagon route and emigrant trail in the United States that connected the Missouri River to valleys in Oregon. The eastern part of the Oregon Trail spanned part of what is now the state of Kans ...

, which opened in 1841. The westward trails served as vital commercial and military highways until the railroad took over this role in the 1860s. To travelers en route to

Utah

Utah ( , ) is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. Utah is a landlocked U.S. state bordered to its east by Colorado, to its northeast by Wyoming, to its north by Idaho, to its south by Arizona, and to its ...

, California, or

Oregon

Oregon () is a U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. The Columbia River delineates much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington (state), Washington, while the Snake River delineates much of it ...

, Kansas was an essential way stop and outfitting location.

Wagon Bed Spring (also Lower Spring or Lower Cimarron Spring) was an important watering spot on the

Cimarron Cutoff

The Santa Fe Trail was a 19th-century route through central North America that connected Franklin, Missouri, with Santa Fe, New Mexico. Pioneered in 1821 by William Becknell, who departed from the Boonslick region along the Missouri River, th ...

of the Santa Fe Trail. Other important locations along the trail were the

Point of Rocks

Point or points may refer to:

Places

* Point, Lewis, a peninsula in the Outer Hebrides, Scotland

* Point, Texas, a city in Rains County, Texas, United States

* Point, the NE tip and a ferry terminal of Lismore, Inner Hebrides, Scotland

* Point ...

and

Pawnee Rock

Pawnee Rock, one of the most famous and beautiful landmarks on the Santa Fe Trail, is located in Pawnee Rock State Park, just north of Pawnee Rock, Kansas, United States. Originally over tall, railroad construction stripped it of some 15 to in ...

.

1820s–1840s: Indian territory

Beginning in the 1820s, the area that would become Kansas was set aside as

Indian Territory

The Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the United States Government for the relocation of Native Americans who held aboriginal title to their land as a sovereign ...

by the U.S. government, and was closed to settlement by whites. The government resettled to

Indian Territory

The Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the United States Government for the relocation of Native Americans who held aboriginal title to their land as a sovereign ...

(now part of

Oklahoma) those Native American tribes based in eastern Kansas, principally the

Kansa and

Osage, opening land to move eastern tribes into the area. By treaty dated June 3, 1825, 20 million acres (81000 km

2) of land was ceded by the Kansa Nation to the United States, and the Kansa tribe was limited to a specific reservation in northeast Kansas. In the same month, the Osage Nation was limited to a reservation in southeast Kansas.

The Missouri

Shawano (or

Shawnee

The Shawnee are an Algonquian-speaking indigenous people of the Northeastern Woodlands. In the 17th century they lived in Pennsylvania, and in the 18th century they were in Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana and Illinois, with some bands in Kentucky a ...

) were the first Native Americans removed to the territory. By treaty made at St. Louis on November 7, 1825, the United States agreed to provide:

: "''the Shawanoe tribe of Indians within the State of Missouri, for themselves, and for those of the same nation now residing in

Ohio

Ohio () is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Of the List of states and territories of the United States, fifty U.S. states, it is the List of U.S. states and territories by area, 34th-l ...

who may hereafter immigrate to the west of the Mississippi, a tract of land equal to fifty miles

0 kmsquare, situated west of the State of Missouri, and within the purchase lately made from the Osage''."

The

Delaware

Delaware ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States, bordering Maryland to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and New Jersey and the Atlantic Ocean to its east. The state takes its name from the adjacent ...

came to Kansas from Ohio and other eastern areas by the treaty of September 24, 1829. The treaty described:

: "''the country in the fork of the Kansas and Missouri Rivers, extending up the Kansas River to the Kansas (Indian's) line, and up the Missouri River to Camp Leavenworth, and thence by a line drawn westerly, leaving a space ten miles (16 km) wide, north of the Kansas boundary line, for an outlet''."

After this point, the

Indian Removal Act of 1830 expedited the process. By treaty dated August 30, 1831, the

Ottawa

Ottawa (, ; Canadian French: ) is the capital city of Canada. It is located at the confluence of the Ottawa River and the Rideau River in the southern portion of the province of Ontario. Ottawa borders Gatineau, Quebec, and forms the c ...

ceded land to the United States and moved to a small reservation on the Kansas River and its branches. The treaty was ratified April 6, 1832. On October 24, 1832, the U.S. government moved the

Kickapoos to a reservation in Kansas. On October 29, 1832, the

Piankeshaw and

Wea agreed to occupy 250 sections of land, bounded on the north by the Shawanoe; east by the western boundary line of Missouri; and west by the

Kaskaskia and

Peoria peoples. By treaty made with the United States on September 21, 1833, the

Otoe tribe

The Otoe (Chiwere: Jiwére) are a Native American people of the Midwestern United States. The Otoe language, Chiwere, is part of the Siouan family and closely related to that of the related Iowa, Missouria, and Ho-Chunk tribes.

Historically, t ...

ceded their country south of the

Little Nemaha River

Little is a synonym for small size and may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* ''Little'' (album), 1990 debut album of Vic Chesnutt

* ''Little'' (film), 2019 American comedy film

*The Littles, a series of children's novels by American author John P ...

.

By September 17, 1836 the confederacy of the

Sac and

Fox, by treaty with the United States, moved north of Kickapoo. By treaty of February 11, 1837, the United States agreed to convey to the

Pottawatomi an area on the

Osage River, southwest of the

Missouri River. The tract selected was in the southwest part of what is now

Miami County.

In 1842, after a treaty between the United States and the

Wyandots, the Wyandot moved to the junction of the Kansas and Missouri Rivers (on land that was shared with the

Delaware

Delaware ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States, bordering Maryland to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and New Jersey and the Atlantic Ocean to its east. The state takes its name from the adjacent ...

until 1843). In an unusual provision, 35 Wyandot were given "

floats" in the 1842 treaty – ownership of sections of land that could be located anywhere west of the Missouri River. In 1847, the Pottawatomi were moved again, to an area containing 576,000 acres (2,330 km

2), being the eastern part of the lands ceded to the United States by the Kansa tribe in 1846. This tract comprised a part of the present counties of

Pottawatomie

The Potawatomi , also spelled Pottawatomi and Pottawatomie (among many variations), are a Native American people of the western Great Lakes region, upper Mississippi River and Great Plains. They traditionally speak the Potawatomi language, a ...

,

Wabaunsee,

Jackson and

Shawnee

The Shawnee are an Algonquian-speaking indigenous people of the Northeastern Woodlands. In the 17th century they lived in Pennsylvania, and in the 18th century they were in Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana and Illinois, with some bands in Kentucky a ...

.

Early 1850s and the territory organization

Despite the treaties establishing Native American ownership of parts of Kansas, by 1850 European Americans were illegally

squatting

Squatting is the action of occupying an abandoned or unoccupied area of land or a building, usually residential, that the squatter does not own, rent or otherwise have lawful permission to use. The United Nations estimated in 2003 that there ...

on their land and clamoring for the entire area to be opened for settlement. Presaging events that were soon to come, several U.S. Army forts, including

Fort Riley, were soon established deep in Indian Territory to guard travelers on the various Western trails.

Although the

Cheyenne

The Cheyenne ( ) are an Indigenous people of the Great Plains. Their Cheyenne language belongs to the Algonquian language family. Today, the Cheyenne people are split into two federally recognized nations: the Southern Cheyenne, who are enr ...

and

Arapahoes tribes were still negotiating with the United States for land in western Kansas (the current state of Colorado) – they signed a treaty on September 17, 1851 – momentum was already building to settle the land.

Kansas–Nebraska Act

Congress began the process of creating Kansas Territory in 1852. That year, petitions were presented at the first session of the

Thirty-second Congress

The 32nd United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, consisting of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, D.C. from March 4, 1851 ...

for a territorial organization of the region lying west of Missouri and

Iowa

Iowa () is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States, bordered by the Mississippi River to the east and the Missouri River and Big Sioux River to the west. It is bordered by six states: Wiscon ...

. No action was taken at that time. However, during the next session, on December 13, 1852, a Representative from Missouri submitted to the House a bill organizing the

Territory of Platte: all the tract lying west of Iowa and Missouri, and extending west to the

Rocky Mountains

The Rocky Mountains, also known as the Rockies, are a major mountain range and the largest mountain system in North America. The Rocky Mountains stretch in straight-line distance from the northernmost part of western Canada, to New Mexico ...

. The bill was referred to the

United States House Committee on Territories, and passed by the full

U.S. House of Representatives on February 10, 1853. However, Southern Senators stalled the progression of the bill in the Senate, while the implications of the bill on slavery and the

Missouri Compromise

The Missouri Compromise was a federal legislation of the United States that balanced desires of northern states to prevent expansion of slavery in the country with those of southern states to expand it. It admitted Missouri as a Slave states an ...

were debated. Heated debate over the bill and other competing proposals would continue for a year, before eventually resulting in the

Kansas–Nebraska Act

The Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854 () was a territorial organic act that created the territories of Kansas and Nebraska. It was drafted by Democratic Senator Stephen A. Douglas, passed by the 33rd United States Congress, and signed into law ...

, which became law on May 30, 1854, establishing the

Nebraska Territory and

Kansas Territory.

Native American territory ceded

Meanwhile, by the summer of 1853, it was clear that eastern Kansas would soon be opened to American settlers. The Commissioner of the

Bureau of Indian Affairs

The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), also known as Indian Affairs (IA), is a United States federal agency within the Department of the Interior. It is responsible for implementing federal laws and policies related to American Indians and A ...

negotiated new treaties that would assign new reservations with annual federal subsidies for the Indians. Nearly all the tribes in the eastern part of the Territory ceded the greater part of their lands prior to the passage of the Kansas territorial act in 1854, and were eventually moved south to the future state of Oklahoma.

In the three months immediately preceding the passage of the bill, treaties were quietly made at Washington with the

Delaware

Delaware ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States, bordering Maryland to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and New Jersey and the Atlantic Ocean to its east. The state takes its name from the adjacent ...

,

Otoe,

Kickapoo,

Kaskaskia,

Shawnee

The Shawnee are an Algonquian-speaking indigenous people of the Northeastern Woodlands. In the 17th century they lived in Pennsylvania, and in the 18th century they were in Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana and Illinois, with some bands in Kentucky a ...

,

Sac,

Fox and other tribes, whereby the greater part of eastern Kansas, lying within one or two hundred miles of the Missouri border, was suddenly opened to white settlement. (The

Kansa reservation had already been reduced by treaty in 1846.) On March 15, 1854, Otoe and Missouri Indians ceded to the United States all their lands west of the Mississippi, except a small strip on the

Big Blue River. On May 6 and May 10, 1854, the

Shawnee

The Shawnee are an Algonquian-speaking indigenous people of the Northeastern Woodlands. In the 17th century they lived in Pennsylvania, and in the 18th century they were in Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana and Illinois, with some bands in Kentucky a ...

s ceded , reserving only for homes. Also on May 6, 1854, the Delaware ceded all their lands to the United States, except a reservation defined in the treaty. On May 17, the Iowa similarly ceded their lands, retaining only a small reservation. On May 18, 1854, the

Kickapoo too ceded their lands, except in the western part of the Territory. In 1854 lands were also ceded by the

Kaskaskia,

Peoria,

Piankeshaw and

Wea and by the Sac and Fox.

The final step in Americanizing the Indians was taking land from tribal control and assigning it to individual Indian households, to buy and sell as European Americans would. For example, in 1854, the

Chippewa (Swan Creek and Black River bands) inhabited in

Franklin County, but in 1859 the tract was transferred to individual Chippewa families.

Kansas Territory

Upon the passage of the Kansas–Nebraska Act on May 30, 1854, the borders of Kansas Territory were set from the Missouri border to the summit of the

Rocky Mountain

The Rocky Mountains, also known as the Rockies, are a major mountain range and the largest mountain system in North America. The Rocky Mountains stretch in straight-line distance from the northernmost part of western Canada, to New Mexico in ...

range (now in central Colorado); the southern boundary was the

37th parallel north

The 37th parallel north is a circle of latitude that is 37 degrees north of the Earth's equatorial plane. It crosses Europe, the Mediterranean Sea, Africa, Asia, the Pacific Ocean, North America, and the Atlantic Ocean.

At this latitude the ...

, the northern was the

40th parallel north. North of the 40th parallel was Nebraska Territory. When Congress set the southern border of the Kansas Territory as the 37th parallel, it was thought that the Osage southern border was also the 37th parallel. The Cherokees immediately complained, saying that it was not the true boundary and that the border of Kansas should be moved north to accommodate the actual border of the Cherokee land. This became known as the

Cherokee Strip controversy.

An invitation to violence

The most controversial provision in the Kansas–Nebraska Act was the stipulation that settlers in Kansas Territory would vote on whether to allow slavery within its borders. This provision repealed the

Missouri Compromise

The Missouri Compromise was a federal legislation of the United States that balanced desires of northern states to prevent expansion of slavery in the country with those of southern states to expand it. It admitted Missouri as a Slave states an ...

of 1820, which had prohibited slavery in any new states created north of

latitude 36°30'. Predictably, violence resulted between the Northerners and Southerners who rushed to settle there in order to control the vote.

Within a few days after the passage of the Act, hundreds of

pro-slavery Missourians crossed into the adjacent territory, selected an area of land, and then united with other Missourians in a meeting or meetings, intending to establish a pro-slavery

preemption upon the entire region. As early as June 10, 1854, the Missourians held a meeting at Salt Creek Valley, a trading post three miles (5 km) west of Fort Leavenworth, at which a "Squatter's Claim Association" was organized. They said they were in favor of making Kansas a

slave state

In the United States before 1865, a slave state was a state in which slavery and the internal or domestic slave trade were legal, while a free state was one in which they were not. Between 1812 and 1850, it was considered by the slave states ...

, if it should require half the citizens of Missouri, musket in hand, to emigrate there, and even to sacrifice their lives in accomplishing this end.

To counter this action, the

Massachusetts Emigrant Aid Company

The New England Emigrant Aid Company (originally the Massachusetts Emigrant Aid Company) was a transportation company founded in Boston, Massachusetts by activist Eli Thayer in the wake of the Kansas–Nebraska Act, which allowed the population of ...

(and other smaller organizations) quickly arranged to send anti-slavery settlers (known as "

Free-Staters") into Kansas in 1854 and 1855. The principal towns founded by the

New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York to the west and by the Canadian provinces ...

ers were

Topeka,

Manhattan

Manhattan (), known regionally as the City, is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the five boroughs of New York City. The borough is also coextensive with New York County, one of the original counties of the U.S. state ...

, and

Lawrence. Several Free-State men also came to Kansas Territory from Ohio, Iowa, Illinois and other Midwestern states.

Bleeding Kansas

Despite the proximity and opposite aims of the settlers, the lid was largely kept on the violence until the election of the Kansas Territorial legislature on March 30, 1855. On that date, Missourians who had streamed across the border (known as "

Border Ruffians") filled the ballot boxes in favor of pro-slavery candidates. As a result, pro-slavery candidates prevailed at every polling district except one (the future

Riley County

Riley County (standard abbreviation: RL) is a county located in the U.S. state of Kansas. As of the 2020 census, the population was 71,959. The largest city and county seat is Manhattan.

Riley County is home to two of Kansas's largest employ ...

), and the first official legislature was overwhelmingly composed of pro-slavery delegates.

From 1855 to 1858, Kansas Territory experienced extensive violence and some open battles. This period, known as "Bleeding Kansas" or "the Border Wars", directly presaged the

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

. The major incidents of Bleeding Kansas include the

Wakarusa War, the

Sacking of Lawrence, the

Pottawatomie massacre, the

Battle of Black Jack

The Battle of Black Jack took place on June 2, 1856, when antislavery forces, led by the noted abolitionist John Brown, attacked the encampment of Henry C. Pate near Baldwin City, Kansas. The battle is cited as one incident of "Bleeding Kans ...

, the

Battle of Osawatomie, and the

Marais des Cygnes massacre.

=Wakarusa War

=

On December 1, 1855, a small army of Missourians, acting under the command of

Douglas County, Kansas Sheriff Samuel J. Jones laid siege to the Free-State stronghold of Lawrence in what would later become known as "The Wakarusa War". A treaty of peace negotiation was announced amid much disorder and cries for the reading of the treaty shortly afterwards. It quelled the disorder and its provisions were generally accepted.

=Sacking of Lawrence

=

On May 21, 1856, pro-slavery forces led by Sheriff Jones attacked Lawrence, burning the Free-State Hotel to the ground, destroying two printing presses, and robbing homes.

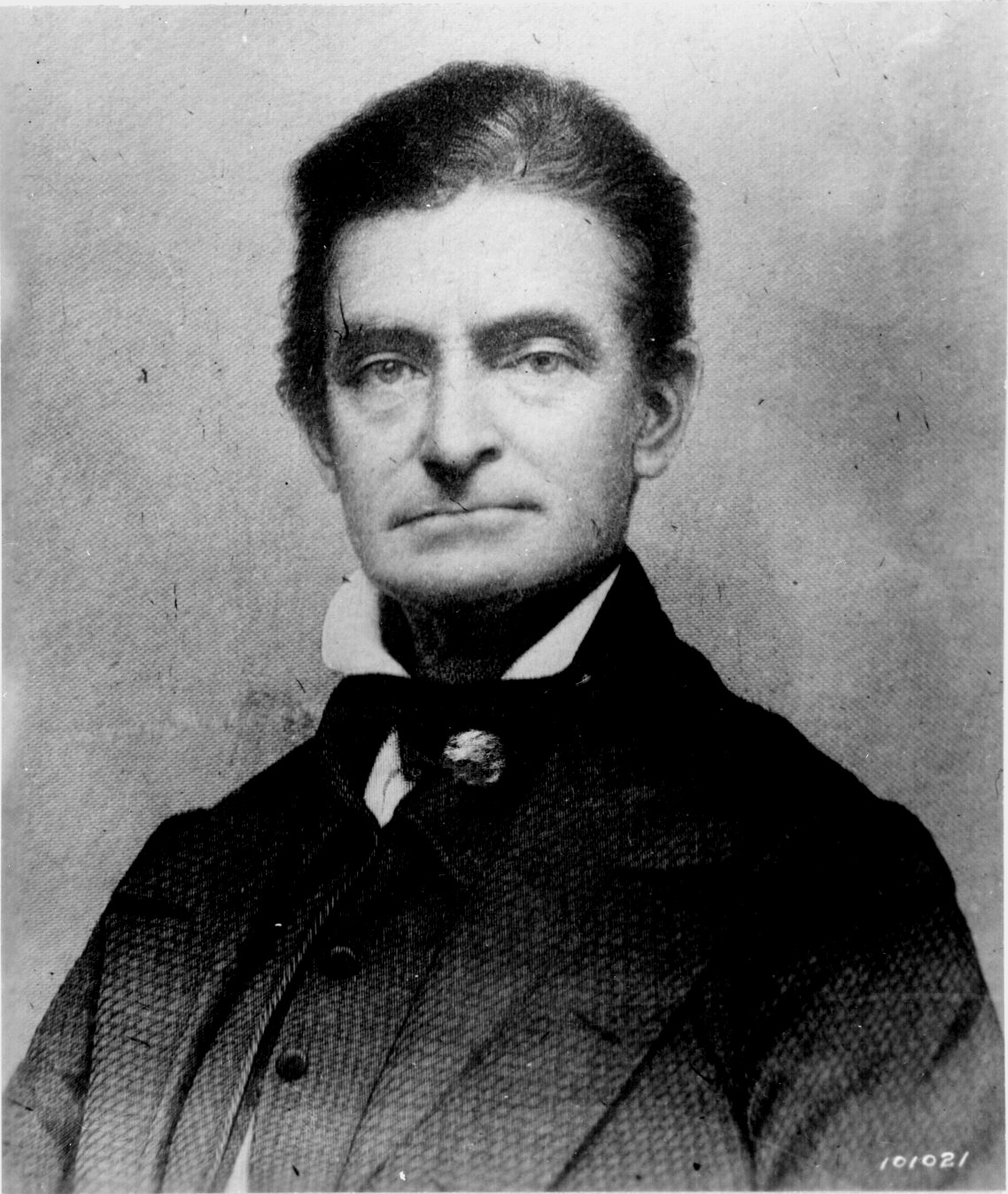

=Pottawatomie massacre

=

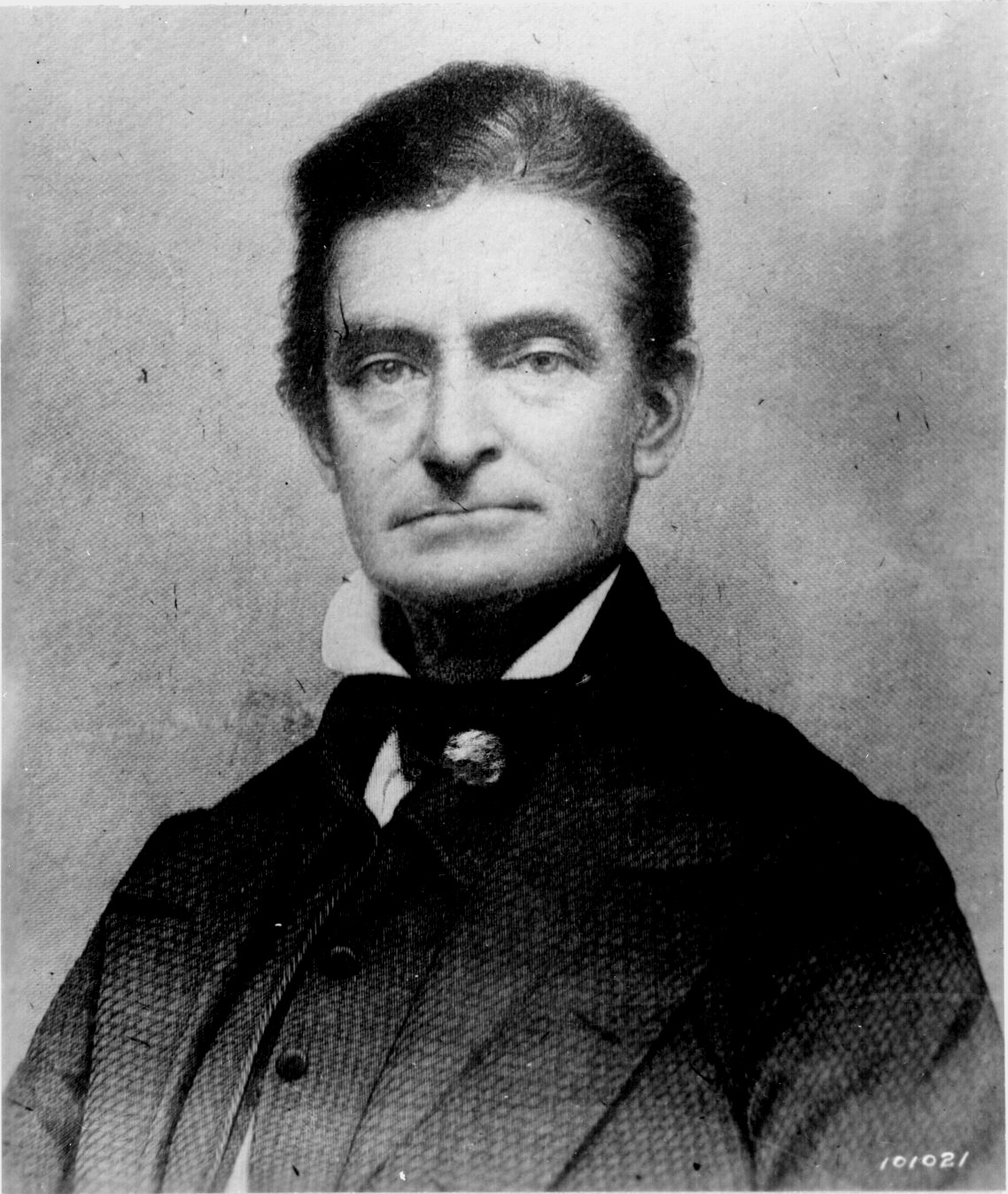

The Pottawatomie massacre occurred during the night of May 24 to the morning of May 25, 1856. In what appears to be a reaction to the

Sacking of Lawrence,

John Brown and a band of

abolitionists

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The Britis ...

(some of them members of the

Pottawatomie Rifles

The Pottawatomie Rifles was a group of about one hundred abolitionist (or free state) settlers of Franklin and Anderson County, Kansas, both of which are along Pottawatomie Creek. The band was formed in the fall of 1855, during the Bleeding Kan ...

) killed five settlers, thought to be pro-slavery, north of Pottawatomie Creek in

Franklin County, Kansas

Franklin County (county code FR) is a county located in the eastern portion of the U.S. state of Kansas. As of the 2020 census, the county population was 25,996. Its county seat and most populous city is Ottawa. The county is predominantly ru ...

. Brown later said that he had not participated in the killings during the Pottawatomie massacre, but that he did approve of them. He went into hiding after the killings, and two of his sons, John Jr. and Jason, were arrested. During their confinement, they were allegedly mistreated, which left John Jr. mentally scarred. On June 2, Brown led a successful attack on a band of Missourians led by Captain

Henry Pate in the

Battle of Black Jack

The Battle of Black Jack took place on June 2, 1856, when antislavery forces, led by the noted abolitionist John Brown, attacked the encampment of Henry C. Pate near Baldwin City, Kansas. The battle is cited as one incident of "Bleeding Kans ...

. Pate and his men had entered Kansas to capture Brown and others. That autumn, Brown went back into hiding and engaged in other

guerrilla warfare activities.

Territorial constitutions

The violently feuding pro-slavery and anti-slavery factions tried to defeat the opposition by pushing through their own version of a state constitution, that would either endorse or condemn slavery. Congress had the final say.

=Topeka Constitution

=

The

Topeka Constitution was adopted on November 11, 1855, in Topeka by delegates elected from across the Kansas Territory. This Free State document was in response to the fraudulent takeover of the Territorial government by pro slavery forces seven months earlier. The Topeka Constitution's Bill of Rights proposed "There shall be no slavery in this state." It was ratified by the people of the Territory on December 15, 1855 and presented in Congress in March 1856. It passed in the U.S. House of Representatives but was prevented from a vote in the Senate by pro-slavery southern senators.

=Lecompton Constitution

=

The

Lecompton Constitution was adopted by a Convention convened by the official pro-slavery government on November 7, 1857. The constitution would have allowed slavery in Kansas as drafted, but the slavery provision was put to a vote. After a series of votes on the provision and the constitution were boycotted alternatively by pro-slavery settlers and Free-State settlers, the Lecompton Constitution was eventually presented to the U.S. Congress for approval. In the end, because it was never clear if the constitution represented the will of the people, it was rejected.

=Leavenworth Constitution

=

While the

Lecompton Constitution was being debated, a new Free-State legislature was elected and seated in Kansas Territory. The new legislature convened a new convention, which framed the

Leavenworth Constitution The Leavenworth Constitution was one of four Kansas state constitutions proposed during the era of Bleeding Kansas. It was never adopted. The Leavenworth Constitution was drafted by a convention of Free-Staters, and was the most progressive of the ...

. This constitution was the most radically progressive of the four proposed, outlawing slavery and providing a framework for women's rights. The constitution was adopted by the convention at Leavenworth on April 3, 1858, and by the people at an election held May 18, 1858 (all while the Lecompton Constitution was still under consideration).

President Buchanan sent the Lecompton Constitution to Congress for approval. The Senate approved the admission of Kansas as a state under the Lecompton Constitution, despite the opposition of Senator Douglas, who believed that the Kansas referendum on the Constitution, by failing to offer the alternative of prohibiting slavery, was unfair. The measure was subsequently blocked in the House of Representatives, where northern congressmen refused to admit Kansas as a slave state. Senator

James Hammond of South Carolina characterized this resolution as the expulsion of the state, asking, "If Kansas is driven out of the Union for being a slave state, can any Southern state remain within it with honor?"

=Wyandotte Constitution

=

Following the failure of the Lecompton and Leavenworth charters, a fourth constitution was drafted; the

Wyandotte Constitution was adopted by the convention which framed it on July 29, 1859. It was adopted by the people at an election held October 4, 1859. It outlawed slavery but was far less progressive than the Leavenworth Constitution. Kansas was admitted into the Union as a

free state under this constitution on January 29, 1861.

[Gary L. Cheatham]

Slavery All the Time or Not At All': The Wyandotte Constitution Debate, 1859–1861"

''Kansas History '' 21 (Autumn 1998): 168–187.

End of hostilities

By the time the Wyandotte Constitution was adopted in October 1859, it was clear that the pro-slavery forces had lost control of Kansas. With this dawning realization and the departure of John Brown from the state, Bleeding Kansas violence virtually ended. The new issue was

John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry, a national event, later that month.

Statehood

Kansas became the 34th state admitted to the Union on January 29, 1861.

The 1860s saw several important developments in the history of Kansas, including participation in the Civil War, the beginning of the cattle drives, the roots of Prohibition in Kansas (which would fully take hold in the 1880s), and the start of the

Indian Wars on the western plains.

James Lane was elected to the Senate from the state of Kansas in 1861, and reelected in 1865.

Civil War

After years of small-scale civil war, Kansas was admitted into the Union as a free state under the "Wyandotte Constitution" on January 29, 1861. Most people gave strong support for the Union cause. However, guerrilla warfare and raids from pro-slavery forces, many spilling over from Missouri, occurred during the Civil War.

At the start of the war in April 1861, the Kansas government had no well-organized militia, no arms, accoutrements or supplies, nothing with which to meet the demands, except the united will of officials and citizens. During the years 1859 to 1860, the military organizations had fallen into disuse or been entirely broken up. The first Kansas regiment was called on June 3, 1861, and the seventeenth, the last raised during the Civil War, July 28, 1864. The entire quota assigned to the Kansas was 16,654, and the number raised was 20,097, leaving a surplus of 3,443 to the credit of Kansas. Statistics indicated that losses of Kansas regiments in killed in battle and from disease are greater per thousand than those of any other State.

Apart from small formal battles, there were 29 Confederate raids into Kansas during the war. The most serious episode came when

Lawrence, Kansas came under attack on August 21, 1863, by guerrillas led by

William Clarke Quantrill. It was in part retaliation for "Jayhawker" raids against pro-Confederate settlements in Missouri.

Lawrence Massacre

After Union Brigadier General

Thomas Ewing Jr. ordered the imprisonment of women who had provided aid to Confederate guerrillas, tragically the jail's roof collapsed, killing five. These deaths enraged guerrillas in Missouri. On August 21, 1863,

William Quantrill led Quantrill's Raid into

Lawrence, burned much of the city and killed over 150 unarmed men and boys. In addition to the jail collapse, Quantrill also rationalized the attack on this citadel of abolition would bring revenge for any wrongs, real or imagined that the Southerners had suffered at the hands of

jayhawkers

Jayhawkers and red legs are terms that came to prominence in Kansas Territory during the Bleeding Kansas period of the 1850s; they were adopted by militant bands affiliated with the free-state cause during the American Civil War. These gangs ...

.

Baxter Springs

The

Battle of Baxter Springs

The Battle of Baxter Springs, more commonly known as the Baxter Springs Massacre, was a minor battle of the American Civil War fought on 6 October 1863, near the present-day town of Baxter Springs, Kansas.

In late 1863, Quantrill's Raiders, a ...

, sometimes called the Baxter Springs Massacre, was a minor battle in the War, fought on October 6, 1863, near the modern-day town of

Baxter Springs, Kansas. The

Battle of Mine Creek, also known as the Battle of the Osage was a

cavalry

Historically, cavalry (from the French word ''cavalerie'', itself derived from "cheval" meaning "horse") are soldiers or warriors who fight mounted on horseback. Cavalry were the most mobile of the combat arms, operating as light cavalry in ...

battle that occurred in Kansas during the war.

Marais des Cygnes

On October 25, 1864, the

Battle of Marais des Cygnes

The Battle of Marais des Cygnes () took place on October 25, 1864, in Linn County, Kansas, during Price's Missouri Raid in the American Civil War. It is also known as the Battle of Trading Post. In late 1864, Confederate Major General Sterlin ...

occurred in

Linn County, Kansas. This Battle of Trading Post was between Major General

Sterling Price and Union forces under Major General

Alfred Pleasonton. Price, after fleeing south after a defeat at Kansas City, was pushed out by Union forces.

Indian Wars in Kansas

Fort Larned

Fort Larned National Historic Site preserves Fort Larned which operated from 1859 to 1878. It is approximately west of Larned, Kansas, United States.

History

The Camp on Pawnee Fork was established on October 22, 1859 to protect traffic al ...

(central Kansas) was established in 1859 as a base of military operations against hostile Indians of the

Central Plains, to protect traffic along the

Santa Fe Trail

The Santa Fe Trail was a 19th-century route through central North America that connected Franklin, Missouri, with Santa Fe, New Mexico. Pioneered in 1821 by William Becknell, who departed from the Boonslick region along the Missouri River, ...

and after 1861 became an agency for the administration of the Central Plains Indians by the

Bureau of Indian Affairs

The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), also known as Indian Affairs (IA), is a United States federal agency within the Department of the Interior. It is responsible for implementing federal laws and policies related to American Indians and A ...

under the terms of the

Fort Wise Treaty of 1861.

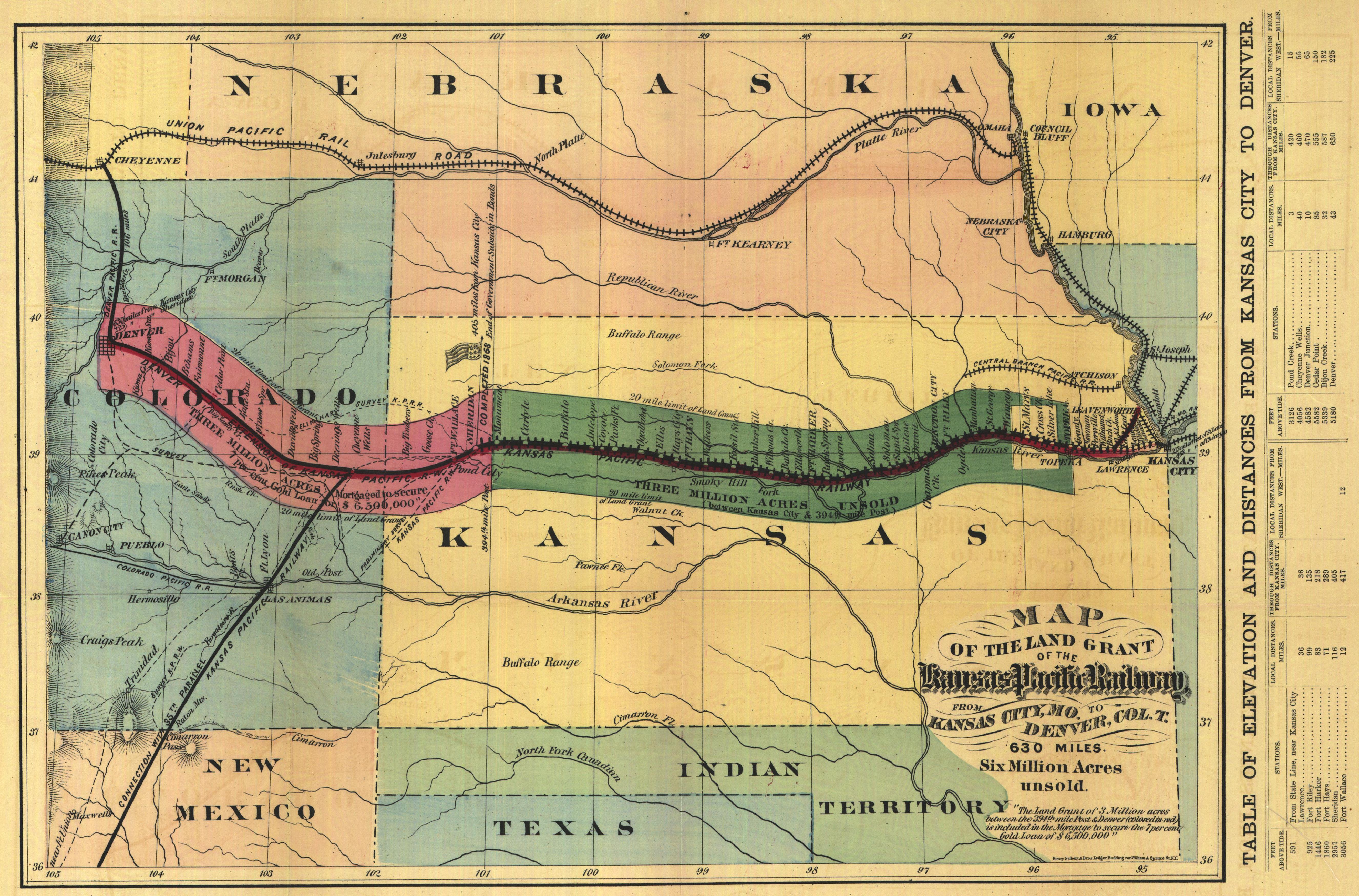

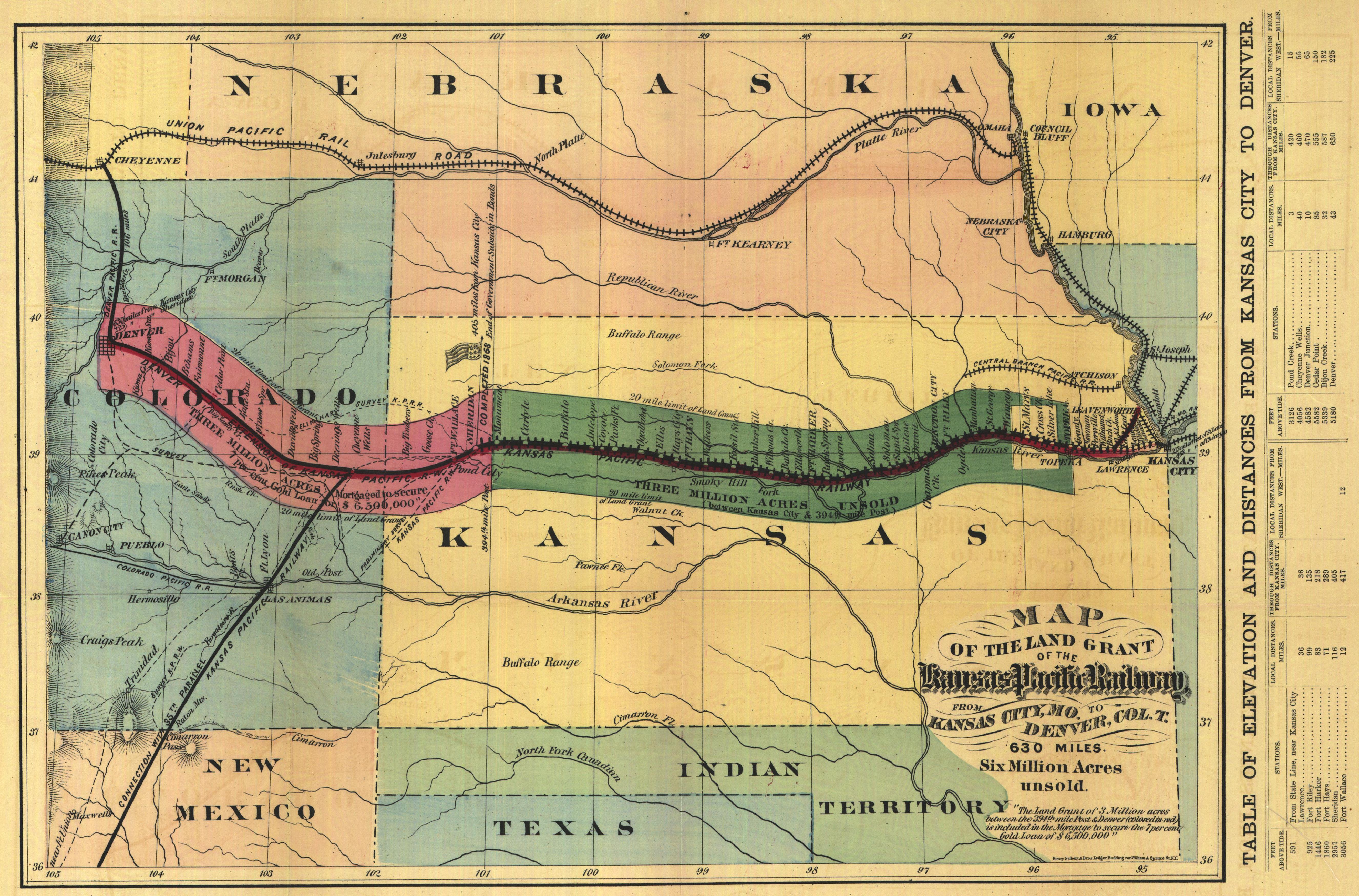

Kansas Pacific railroad

In 1863, the Union Pacific Eastern Division (renamed the

Kansas Pacific in 1869) was authorized by the

United States Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is Bicameralism, bicameral, composed of a lower body, the United States House of Representatives, House of Representatives, and an upper body, ...

's

Pacific Railway Act to create the southerly branch of the

transcontinental railroad alongside the Union Pacific. Pacific Railway Act also authorized large

land grant

A land grant is a gift of real estate—land or its use privileges—made by a government or other authority as an incentive, means of enabling works, or as a reward for services to an individual, especially in return for military service. Grants ...

s to the railroad along its mainline. The company began construction on its main line westward from Kansas City in September 1863.

In the postwar era, many railroads were planned, but not all were actually built. The nationwide

Panic of 1873 dried up funding. Land speculators and local boosters identified many potential towns, and those reached by the railroad had a chance, while the others became ghost towns. In Kansas, nearly 5000 towns were mapped out, but by 1970 only 617 were actually operating. In the mid-20th century, closeness to an interstate exchange determined whether town would flourish or struggle for business.

Cattle towns

After the Civil War, the railroads did not reach Texas, so the herdsman brought their cattle to Kansas rail heads. In 1867,

Joseph G. McCoy built stockyards in

Abilene, Kansas

Abilene (pronounced ) is a city in, and the county seat of, Dickinson County, Kansas, United States. As of the 2020 census, the population of the city was 6,460. It is home of The Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library and Museum and the ...

and helped develop the

Chisholm Trail, encouraging Texas cattlemen to undertake cattle drives to his stockyards from 1867 to 1887. The stockyards became the largest west of

Kansas City. Once the cattle was drove north, they were shipped eastward from the railhead of the

Kansas Pacific Railway.

In 1871,

Wild Bill Hickok became marshal of

Abilene, Kansas

Abilene (pronounced ) is a city in, and the county seat of, Dickinson County, Kansas, United States. As of the 2020 census, the population of the city was 6,460. It is home of The Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library and Museum and the ...

. His encounter there with John Wesley Hardin resulted in the latter fleeing the town after Wild Bill managed to disarm him. Hickok was also a deputy marshal at

Fort Riley and a marshal at

Hays in the

Wild West. In the 1880s at

Greensburg, Kansas, the

Big Well was built to provide water for the Santa Fe and Rock Island railroads. At deep and in diameter it is the world's largest hand-dug well.

Coronado, Kansas

Coronado is an unincorporated community in Wichita County, Kansas, United States. It is located a couple of miles east of Leoti.

History

Platted in 1885, Coronado was involved in one of the bloodiest county seat fight in the history of the Ame ...

, was established in 1885. It was involved in one of the bloodiest

county seat fights in the history of the

American West

The Western United States (also called the American West, the Far West, and the West) is the region comprising the westernmost states of the United States. As American settlement in the U.S. expanded westward, the meaning of the term ''the Wes ...

. The shoot-out on February 27, 1887, with boosters – some would say hired gunmen – from nearby Leoti left several people dead and wounded.

Exodusters

In 1879, after the end of Reconstruction in the South, thousands of Freedmen moved from Southern states to Kansas. Known as the

Exodusters

Exodusters was a name given to African Americans who migrated from states along the Mississippi River to Kansas in the late nineteenth century, as part of the Exoduster Movement or Exodus of 1879. It was the first general migration of black pe ...

, they were lured by the prospect of good, cheap land and better treatment. The all-black town of

Nicodemus, Kansas, which was founded in 1877, was an organized settlement that predates the Exodusters but is often associated with them.

Prohibition

On February 19, 1881, Kansas became the first state to amend its constitution to

prohibit all alcoholic beverages. This action was spawned by the

temperance movement, and was enforced by the ax-toting

Carrie A. Nation beginning in 1888. After 1890 prohibition was joined with progressivism to create a reform movement that elected four successive governors between 1905 and 1919; they favored extreme prohibition enforcement policies, and claimed Kansas was truly dry. Kansas did not repeal prohibition until 1948, and even then it continued to prohibit public bars, a restriction which was not lifted until 1987. Kansas did not allow retail liquor sales on Sundays until 2005, and most localities still prohibit Sunday liquor sales. By the

Alcohol laws of Kansas today 29 counties are

dry counties.

Religion

The city of

Topeka played a notable role in the history of American Christianity around the beginning of the 20th century.

Charles Sheldon

Charles Monroe Sheldon (February 26, 1857 – February 24, 1946) was an American Congregationalist minister and a leader of the Social Gospel movement. His novel ''In His Steps'' introduced the principle "What would Jesus do?", which articu ...

, a leader in the

Social Gospel movement who first used the phrase

What would Jesus do?

The phrase "What would Jesus do?", often abbreviated to WWJD, became popular particularly in the United States in the early 1900s after the widely read book by Charles Sheldon entitled, '' In His Steps: What Would Jesus Do''. The phrase had a r ...

, preached in Topeka. Topeka was also the home to the church of

Charles Fox Parham, whom many historians associate with the beginning of the modern

Pentecostalism

Pentecostalism or classical Pentecostalism is a Protestant Charismatic Christian movement movement.

Farming

Environment

Early settlers discovered that Kansas was not the "Great American Desert", but they also found that the very harsh climate—with tornadoes, blizzards, drought, hail, floods and grasshoppers—made for the high risk of a ruined crop. Many early settlers were financially ruined, and especially in the early 1890s, either protested through the Populist movement or went back east. In the 20th century, crop insurance, new conservation techniques, and large-scale federal aid have lowered the risk. Immigrants, especially Germans and their children, comprised the largest element of settlers after 1860; they were attracted by the good soil, low priced lands from the railroad companies, and (if they were American citizens) the chance to homestead and receive title to the land at no cost from the federal government.

The problem of blowing dust came not because farmers grew too much wheat, but because the rainfall was too little to grow enough wheat to keep the topsoil from blowing away. In the 1930s techniques and technologies of soil conservation, most of which had been available but ignored before the Dust Bowl conditions began, were promoted by the Soil Conservation Service (SCS) of the US Department of Agriculture, so that, with cooperation from the weather, soil condition was much improved by 1940.

Farm life

On the

Great Plains

The Great Plains (french: Grandes Plaines), sometimes simply "the Plains", is a broad expanse of flatland in North America. It is located west of the Mississippi River and east of the Rocky Mountains, much of it covered in prairie, steppe, a ...

very few single men attempted to operate a farm or ranch; farmers clearly understood the need for a hard-working wife, and numerous children, to handle the many chores, including child-rearing, feeding and clothing the family, managing the housework, feeding the hired hands, and, especially after the 1930s, handling the paperwork and financial details. During the early years of settlement in the late 19th century, farm women played an integral role in assuring family survival by working outdoors. After a generation or so, women increasingly left the fields, thus redefining their roles within the family. New conveniences such as sewing and washing machines encouraged women to turn to domestic roles. The scientific housekeeping movement was promoted across the land by the media and government extension agents, as well as county fairs which featured achievements in home cookery and canning, advice columns for women in the farm papers, and home economics courses in the schools.

Although the eastern image of farm life on the prairies emphasizes the isolation of the lonely farmer and farm life, in reality rural folk created a rich social life for themselves. They often sponsored activities that combined work, food, and entertainment such as

barn raisings, corn huskings, quilting bees, Grange meeting, church activities, and school functions. The womenfolk organized shared meals and potluck events, as well as extended visits between families.

Agriculture manufacturing

In 1947,

Lyle Yost founded Hesston Manufacturing Company. It specialized in farm equipment, including self-propelled windrowers and the StakHand hay harvester. In 1974, Hesston Company commissioned its first belt buckles, which became popular on the

rodeo circuit and with collectors. In 1991, the American-based equipment manufacturer

AGCO Corporation purchased

Hesston Corporation and farm equipment is still manufactured in the city.

1890s

In 1896

William Allen White, editor of the ''Emporia Gazette'' attracted national attention with a scathing attack on

William Jennings Bryan

William Jennings Bryan (March 19, 1860 – July 26, 1925) was an American lawyer, orator and politician. Beginning in 1896, he emerged as a dominant force in the History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, running ...

, the Democrats, and the Populists titled "What's the Matter With Kansas?" White sharply ridiculed Populist leaders for letting Kansas slip into economic stagnation and not keeping up economically with neighboring states because their anti-business policies frightened away economic capital from the state. The Republicans sent out hundreds of thousands of copies of the editorial in support of

William McKinley

William McKinley (January 29, 1843September 14, 1901) was the 25th president of the United States, serving from 1897 until his assassination in 1901. As a politician he led a realignment that made his Republican Party largely dominant in t ...

during the

1896 United States presidential election. While McKinley carried the small towns and cities of the state, Bryan swept the wheat farms and won the electoral vote, even as McKinley won the national vote.

20th century

Progressive era

Kansas was a center of the

progressive movement, with enthusiastic support from the middle classes. Much of the leadership was provided by Republican newspaper editors, such as

William Allen White of the ''Emporia Gazette'',

Joseph L. Bristow of Salina, and Edward Hoch, of the ''Marion Record''. Religion and gender played a role. Methodists and crusaders from the

Woman's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) demanded the end of the liquor business. WCTU activists also became supporters of woman suffrage. White called for a direct primary because Republicans attended the Democratic caucus in order to nominate the weakest candidate; Democrats did the same and thus the weakest men get nominated and elected. A direct primary would let the Republicans voters select the best candidate for their party and likewise the Democrats. White never ran for office but Bristow was elected senator in 1908 and Hoch governor in 1904 and 1906. Hoch denounced the conservative wing of his party:

it grows out of unwise leadership; of unfair standards of republicanism; of factional intolerance; of the multiplicity of useless offices; of extravagance in public expenditures; of enormous increase in burdens of taxation.

According to Craig Miner, the main issues of progressive era Kansas (in chronological order), were the flood of 1903, conservation, the battle to control Standard Oil in 1905, regulation of railroads and trusts, capital punishment, women's rights, public health, urban reform, the Progressive Party campaign of 1912, and isolationism in foreign policy. In addition there was a long debate on the state purchase of school textbooks. The state wrote, printed and sold its school books until 1937. Supervision was lax and the textbooks were poorly done--filled with typos, grammatical errors, garbled passages and poor artwork. However, the state did save some money.

According to Gene Clanton, Populism and progressivism in Kansas had similarities but different bases of support. Both opposed corruption and trusts. Populism emerged earlier and came out of the farm community. It was radically egalitarian in favor of the disadvantaged classes; it was weak in the towns and cities except in labor unions. Progressivism, on the other hand, was a later movement. It emerged after the 1890s from the urban business and professional communities. Most of its activists had opposed populism. It was elitist, and emphasized education and expertise. Its goals were to enhance efficiency, reduce waste, and enlarge the opportunities for upward social mobility. However, some former Populists changed their emphasis after 1900 and supported progressive reforms.ref> Gene Clanton, "Populism, Progressivism, and Equality: The Kansas Paradigm" ''Agricultural History'' (1977) 51#3 pp.559-581.

The new

city manager

A city manager is an official appointed as the administrative manager of a city, in a "Mayor–council government" council–manager form of city government. Local officials serving in this position are sometimes referred to as the chief exec ...

system was designed by progressives to increase efficiency and reduce partisanship and avoid the bribery of elected local officials. It was promoted in the press, led by Henry J. Allen of the ''Wichita Beacon,'' and pushed through by Governor

Arthur Capper

Arthur Capper (July 14, 1865 – December 19, 1951) was an American politician from Kansas. He was the 20th governor of Kansas (the first born in the state) from 1915 to 1919 and a United States senator from 1919 to 1949. He also owned a radi ...

. By the 1980s 52 Kansas cities used the system.

1910s

In 1915, the El Dorado Oil Field, around the city of

El Dorado

El Dorado (, ; Spanish for "the golden"), originally ''El Hombre Dorado'' ("The Golden Man") or ''El Rey Dorado'' ("The Golden King"), was the term used by the Spanish in the 16th century to describe a mythical tribal chief (''zipa'') or king ...

, was the first oil field that was found using science/geologic mapping, and part of the

Mid-Continent oil province. By 1918, the El Dorado Oil Field was the largest single field producer in the US, and was responsible for 12.8% of national oil production and 9% of the world production. It was deemed by some as "the oil field that won

World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

".

In World War I, 80,000 Kansans enlisted in the military after April, 1917 when the United States declared war on Germany. They were attached mostly to the 35th, the 42nd, the 89th, and the 92nd infantry divisions. The state's large

German element had favored neutrality and were under close watch. Often they were forced to buy war bonds or stop speaking German in public. German churches largely switched to English at this time. The intense nationalism of the war years undermined progressivism and led to conservative business dominance in the 1920s. However, the efficiency dimension persisted.

1920s

While urban Kansas prospered in the 1920s, the farm economy had overexpanded when wheat prices were high during the war, and had to cut back sharply. Many farmers took out large mortgages to buy out their neighbors in 1919, and now were hard pressed.

In 1922, suffragist

Ella Uphay Mowry

Ella Uphay (Herod) Mowry (July 1865 – August 2, 1923), also known as Mrs. W.D. Mowry, was an American educator, suffragist, and women's rights activist. A member of the Republican Party, she became the first female gubernatorial candidate in K ...

became the first female gubernatorial candidate in the state when she ran as "Mrs. W.D. Mowry." She later stated that, "Someone had to be the pioneer. I firmly believe that some day a woman will sit in the governor's chair in Kansas."

The

KKK

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to the KKK or the Klan, is an American white supremacist, right-wing terrorist, and hate group whose primary targets are African Americans, Jews, Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and Cath ...

(Ku Klux Klan) flourished briefly in the early 1920s. It faced several legal battles, and collapsed after 1925.

The

flag of Kansas

The flag of the state of Kansas was adopted in 1927. The elements of the state flag include the Kansas state seal and a sunflower. This original design was modified in 1961 to add the name of the state at the bottom of the flag.

Official descri ...

was designed in 1925. It was officially adopted by the Kansas State Legislature in 1927 and modified in 1961 (the word "Kansas" was added below the seal in gold block lettering). It was first flown at

Fort Riley by

Governor

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

Ben S. Paulen in 1927 for the troops at Fort Riley and for the

Kansas National Guard

The Kansas National Guard, is the component of the United States National Guard in the U.S. state of Kansas. It comprises both the Kansas Army National Guard and the Kansas Air National Guard. The Governor of Kansas is Commander-in-Chief of the Ka ...

.

William Allen White in his novels and short stories, developed his idea of the small town as a metaphor for understanding social change and for preaching the necessity of community. While he expressed his views in terms of his small Kansas city, he tailored his rhetoric to the needs and values of all of urban America. The cynicism of the post-World War I world stilled his imaginary literature, but for the remainder of his life he continued to propagate his vision of small-town community. He opposed chain stores and mail order firms as a threat to the business owner on Main Street. The

Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

shook his faith in a cooperative, selfless, middle-class America.

Great depression

The

Dust Bowl was a series of

dust storm

A dust storm, also called a sandstorm, is a meteorological phenomenon common in arid and semi-arid regions. Dust storms arise when a gust front or other strong wind blows loose sand and dirt from a dry surface. Fine particles are transp ...

s caused by a massive drought that began in 1930 and lasted until 1941. The effect of the drought was overshadowed by the plunging wheat prices and the financial crisis of the

Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

. Many local banks were forced to close. Some farmers left the land but even larger numbers of unemployed men left the cities to return to their family's farm.

The state became an eager participant in such major

New Deal

The New Deal was a series of programs, public work projects, financial reforms, and regulations enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1939. Major federal programs agencies included the Civilian Con ...

relief programs as the

Civil Works Administration, the

Federal Emergency Relief Administration, the

Civilian Conservation Corps

The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) was a voluntary government unemployment, work relief program that ran from 1933 to 1942 in the United States for unemployed, unmarried men ages 18–25 and eventually expanded to ages 17–28. The CCC was a ...

, the

Works Progress Administration

The Works Progress Administration (WPA; renamed in 1939 as the Work Projects Administration) was an American New Deal agency that employed millions of jobseekers (mostly men who were not formally educated) to carry out public works projects, i ...

, which put hundreds of thousands of Kansans—mostly men—to work at unskilled labor. Most important of all were the New Deal farm programs, which raised prices of wheat and other crops and allowed economic recovery by 1936. Republican Governor

Alf Landon also employed emergency measures, including a moratorium on mortgage foreclosures and a balanced budget initiative. The

Agricultural Adjustment Administration

The Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA) was a United States federal law of the New Deal era designed to boost agricultural prices by reducing surpluses. The government bought livestock for slaughter and paid farmers subsidies not to plant on part o ...

succeeded in raising wheat prices after 1933, thus alleviating the most serious distress.

World War II

The state's main contribution to the war effort, besides tens of thousands of servicemen and servicewomen, was the enormous increase in the output of grain production. Farmers nevertheless grumbled about price ceilings for their wheat, production quotas, the movement of hired hands to well-paid factory jobs, and the shortage of farm machinery; they lobbied the Congress to make sure that young farmers were deferred from the draft.

Wichita, which had long shown an interest in aviation, became a major manufacturing center for the aircraft industry during the war, attracting tens of thousands of underemployed workers from the farms and small towns of the state.

The Women's Land Army of America (WLA) was a wartime women's labor pool organized by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. It failed to attract many town or city women to do farm work, but it succeeded in training several hundred farm wives in machine handling, safety, proper clothing, time-saving methods, and nutrition.

Cold War era

Kansas state law permitted segregated public schools, which operated in Topeka and other cities. On May 17, 1954, the Supreme Court in ''

Brown v. Board of Education'' unanimously declared that separate educational facilities are inherently unequal and, as such, violate the 14th Amendment to the United States Constitution, which guarantees all citizens "equal protection of the laws." ''Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka'' explicitly outlawed ''

de jure

In law and government, ''de jure'' ( ; , "by law") describes practices that are legally recognized, regardless of whether the practice exists in reality. In contrast, ("in fact") describes situations that exist in reality, even if not legall ...

''

racial segregation

Racial segregation is the systematic separation of people into racial or other ethnic groups in daily life. Racial segregation can amount to the international crime of apartheid and a crime against humanity under the Statute of the Intern ...

of public education facilities (legal establishment of separate government-run schools for blacks and whites). The site consists of the Monroe Elementary School, one of the four segregated elementary schools for African American children in Topeka, Kansas (and the adjacent grounds).

During the 1950s and 1960s,

intercontinental ballistic missile

An intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) is a ballistic missile with a range greater than , primarily designed for nuclear weapons delivery (delivering one or more thermonuclear warheads). Conventional, chemical, and biological weapo ...

s (designed to carry a single nuclear warhead) were stationed throughout Kansas facilities. They were stored (to be launched from) hardened underground silos. The Kansas facilities were deactivated in the early 1980s.

On June 8, 1966,

Topeka, Kansas was struck by an ''F5'' rated

tornado

A tornado is a violently rotating column of air that is in contact with both the surface of the Earth and a cumulonimbus cloud or, in rare cases, the base of a cumulus cloud. It is often referred to as a twister, whirlwind or cyclone, alt ...

, according to the

Fujita scale. The "

1966 Topeka tornado" started on the southwest side of town, moving northeast, hitting various landmarks (including

Washburn University

Washburn University (WU) is a public university in Topeka, Kansas, United States. It offers undergraduate and graduate programs, as well as professional programs in law and business. Washburn has 550 faculty members, who teach more than 6,10 ...

). Total dollar cost was put at $100 million.

Recent personalities

Kansas was home to

President Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; ; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was an American military officer and statesman who served as the 34th president of the United States from 1953 to 1961. During World War I ...

of Abilene, presidential candidates

Bob Dole and

Alf Landon, and the aviator

Amelia Earhart. Famous athletes from Kansas include

Barry Sanders,

Gale Sayers

Gale Eugene Sayers (May 30, 1943September 23, 2020) was an American professional football player who was both a halfback and return specialist in the National Football League (NFL). In a relatively brief but highly productive NFL career, Say ...

,

Jim Ryun,

Walter Johnson,

Clint Bowyer,

Maurice Greene, and

Lynette Woodard.

Sports

The

Kansas Sports Hall of Fame chronicles the history of competitive athletics in the state.

College sports

:''See also

Timeline of college football in Kansas This timeline of college football in Kansas sets forth notable college football-related events that occurred in the state of Kansas.

Overview

College football in Kansas began in 1890 and has its roots in the formation of the Kansas Collegiate Ath ...

''

Kansas sports history includes several significant firsts. The first

college football

College football (french: Football universitaire) refers to gridiron football played by teams of student athletes. It was through college football play that American football in the United States, American football rules first gained populari ...

game played in Kansas was the

1890 Kansas vs. Baker football game played in

Baldwin City. Baker won 22–9.

The first

night football game west of the Mississippi was played in

Wichita, Kansas in

1905 between Cooper College (now called

Sterling College) and Fairmount College (now

Wichita State University). Later that year, Fairmount also played an

experimental game against the

Washburn Ichabods that was used to test new rules designed to make football safer.

In 1911, the

Kansas Jayhawks traveled to play the

Missouri Tigers for what is considered the

first homecoming game ever. The first college football

homecoming

Homecoming is the tradition of welcoming back alumni or other former members of an organization to celebrate the organization's existence. It is a tradition in many high schools, colleges, and churches in the United States, Canada and Liberia. ...

game

A game is a structured form of play, usually undertaken for entertainment or fun, and sometimes used as an educational tool. Many games are also considered to be work (such as professional players of spectator sports or games) or art (suc ...

ever televised was played in

Manhattan

Manhattan (), known regionally as the City, is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the five boroughs of New York City. The borough is also coextensive with New York County, one of the original counties of the U.S. state ...

between the

Kansas State Wildcats and the

Nebraska Cornhuskers