History of Harvard University on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

With some 17,000

With some 17,000

The Making of American Liberal Theology: Imagining Progressive Religion, 1805–1900, Volume 1

. Westminster John Knox Press, 2001 When the

During this period, Harvard experienced unparalleled growth that securely placed it financially in a league of its own among American colleges. Ronald Story notes that in 1850, Harvard's total assets were "five times that of Amherst and Williams combined, and three times that of Yale". Story also notes that "all the evidence... points to the four decades from 1815 to 1855 as the era when parents, in Henry Adams's words, began 'sending their children to Harvard College for the sake of its social advantages'". Under President Eliot's tenure, Harvard earned a reputation for being more liberal and democratic than either

During this period, Harvard experienced unparalleled growth that securely placed it financially in a league of its own among American colleges. Ronald Story notes that in 1850, Harvard's total assets were "five times that of Amherst and Williams combined, and three times that of Yale". Story also notes that "all the evidence... points to the four decades from 1815 to 1855 as the era when parents, in Henry Adams's words, began 'sending their children to Harvard College for the sake of its social advantages'". Under President Eliot's tenure, Harvard earned a reputation for being more liberal and democratic than either  The annual undergraduate tuition was $300 in the 1930s and $400 in the 1940s, doubling to $800 in 1953. It reached $2,600 in 1970 and $22,700 in 2000.

The annual undergraduate tuition was $300 in the 1930s and $400 in the 1940s, doubling to $800 in 1953. It reached $2,600 in 1970 and $22,700 in 2000.

Harvard Restrictions Could Reshape Exclusive Student Clubs

, The New York Times, May 6, 2016 After the Supreme Court ruled in

Though Harvard ended required chapel in the mid-1880s, the school remained culturally Protestant and fears of dilution grew as enrollment of immigrants, Catholics and Jews surged at the turn of the 20th century. By 1908, Catholics made up nine percent of the freshman class and between 1906 and 1922 Jewish enrollment at Harvard increased from six to 25%. President A. Lawrence Lowell tried to impose a 12% quota on Jews, but the faculty rejected it even though he managed to cut the numbers in half anyway. By the end of World War II, the quotas and most of the latent antisemitism had faded away.

Policies of exclusion were not limited to religious minorities. In 1920, "Harvard University maliciously persecuted and harassed" those it believed to be gay via a " Secret Court" led by President Lowell. Summoned at the behest of a wealthy alumnus, the inquisitions and expulsions carried out by this tribunal, in conjunction with the "vindictive tenacity of the university in ensuring that the stigmatization of the expelled students would persist throughout their productive lives" led to two suicides. Harvard President

Though Harvard ended required chapel in the mid-1880s, the school remained culturally Protestant and fears of dilution grew as enrollment of immigrants, Catholics and Jews surged at the turn of the 20th century. By 1908, Catholics made up nine percent of the freshman class and between 1906 and 1922 Jewish enrollment at Harvard increased from six to 25%. President A. Lawrence Lowell tried to impose a 12% quota on Jews, but the faculty rejected it even though he managed to cut the numbers in half anyway. By the end of World War II, the quotas and most of the latent antisemitism had faded away.

Policies of exclusion were not limited to religious minorities. In 1920, "Harvard University maliciously persecuted and harassed" those it believed to be gay via a " Secret Court" led by President Lowell. Summoned at the behest of a wealthy alumnus, the inquisitions and expulsions carried out by this tribunal, in conjunction with the "vindictive tenacity of the university in ensuring that the stigmatization of the expelled students would persist throughout their productive lives" led to two suicides. Harvard President

Getting In

.

online edition

* Hawkins, Hugh. ''Between Harvard and America: The Educational Leadership of Charles W. Eliot'' (1972). 404 pp. * Hay, Ida. ''Science in the Pleasure Ground: A History of the Arnold Arboretum'' (1995). 349 pp. * Hoerr, John, ''We Can't Eat Prestige: The Women Who Organized Harvard;''

online edition

* Keller, Morton, and Phyllis Keller. ''Making Harvard Modern: The Rise of America's University'' (2001), major history covers 1933 to 200

online edition

* King, Moses

''Harvard and its surroundings''

Cambridge, Massachusetts : Moses King, 1884 * Kuklick, Bruce. ''The Rise of American Philosophy: Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1860–1930'' (1977). 674 pp. * LaPiana, William P. ''Logic and Experience: The Origin of Modern American Legal Education'', (1994). 254 pp. on reforms by

Harvard College

Harvard College is the undergraduate college of Harvard University, an Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636, Harvard College is the original school of Harvard University, the oldest institution of higher ...

, around which Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of highe ...

eventually grew, was founded in 1636 in Cambridge, Massachusetts

Cambridge ( ) is a city in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, United States. As part of the Boston metropolitan area, the cities population of the 2020 U.S. census was 118,403, making it the fourth most populous city in the state, behind Boston, ...

, making it the oldest institution of higher learning in the United States.

For centuries, its graduates dominated Massachusetts' clerical and civil ranks and beginning in the 19th century its stature became national, then international, as a dozen graduate and professional schools were formed alongside the nucleus undergraduate College. Historically influential in national roles are the schools of medicine

Medicine is the science and practice of caring for a patient, managing the diagnosis, prognosis, prevention, treatment, palliation of their injury or disease, and promoting their health. Medicine encompasses a variety of health care pr ...

(1782), law

Law is a set of rules that are created and are enforceable by social or governmental institutions to regulate behavior,Robertson, ''Crimes against humanity'', 90. with its precise definition a matter of longstanding debate. It has been vario ...

(1817) and business

Business is the practice of making one's living or making money by producing or buying and selling products (such as goods and services). It is also "any activity or enterprise entered into for profit."

Having a business name does not separ ...

(1908) as well as the Harvard Graduate School of Arts and Sciences

The Graduate School of Arts and Sciences (GSAS) is the largest of the twelve graduate schools of Harvard University. Formed in 1872, GSAS is responsible for most of Harvard's graduate degree programs in the humanities, social sciences, and natural ...

(1890).

Since the late 19th century Harvard has been one of the most prestigious schools in the world, its library system and financial endowment larger than those of any other.

__TOC__

Founding and Colonial era

With some 17,000

With some 17,000 Puritans

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become more Protestant. ...

migrating to New England by 1636, Harvard was founded in anticipation of the need for training clergy for the new commonwealth, a "church in the wilderness". Harvard was established in 1636 by vote of the Great and General Court of the Massachusetts Bay Colony

The Massachusetts Bay Colony (1630–1691), more formally the Colony of Massachusetts Bay, was an English settlement on the east coast of North America around the Massachusetts Bay, the northernmost of the several colonies later reorganized as th ...

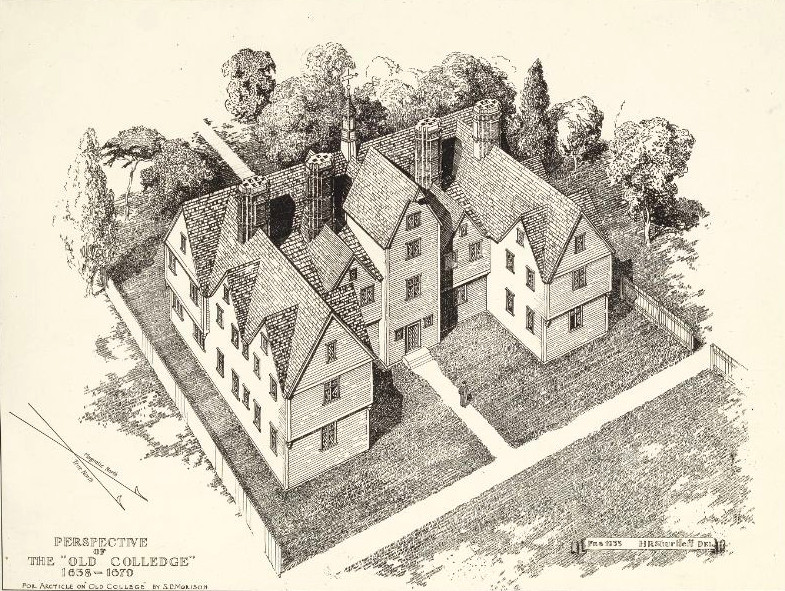

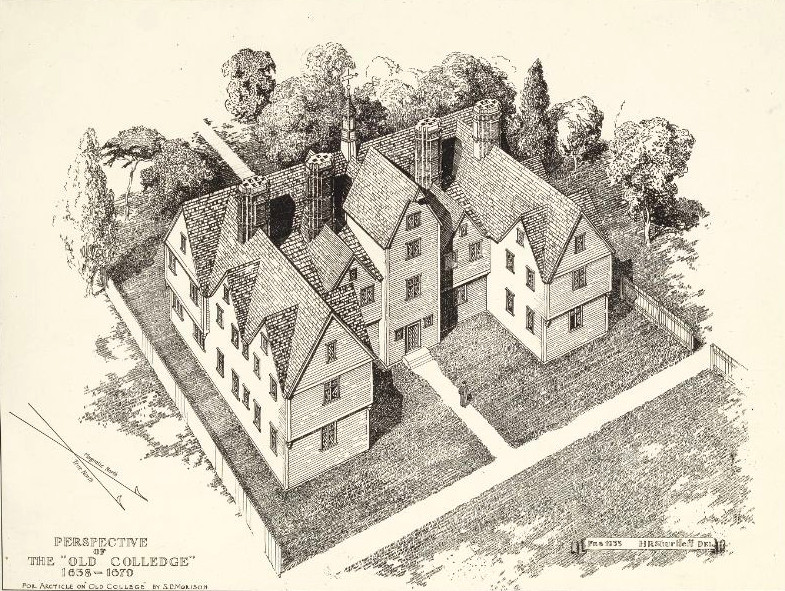

. In 1638, the school received a printing pressthe only press at the time in what is now the United States, until Harvard acquired a second in 1659.

On March 13, 1639, the college was renamed Harvard College after clergyman John Harvard, a University of Cambridge

, mottoeng = Literal: From here, light and sacred draughts.

Non literal: From this place, we gain enlightenment and precious knowledge.

, established =

, other_name = The Chancellor, Masters and Schola ...

alumnus who had willed the new school £779 pounds sterling

Sterling (abbreviation: stg; Other spelling styles, such as STG and Stg, are also seen. ISO code: GBP) is the currency of the United Kingdom and nine of its associated territories. The pound ( sign: £) is the main unit of sterling, and ...

and his library of some 400 books.

In the 1640s, Harvard College established the Harvard Indian College

The Indian College was an institution established in the 1640s in order to educate Native American students at Harvard College in the town of Cambridge, in the Massachusetts Bay Colony. The Indian College's building, located in Harvard Yard, wa ...

, which educated Native American students. It was only attended by a handful of students, only one of whom graduated.

The colony charter creating the Harvard Corporation

The President and Fellows of Harvard College (also called the Harvard Corporation or just the Corporation) is the smaller and more powerful of Harvard University's two governing boards, and is now the oldest corporation in America. Together with ...

was granted in 1650 at the beginning of the English Interregnum

The Interregnum was the period between the execution of Charles I on 30 January 1649 and the arrival of his son Charles II in London on 29 May 1660 which marked the start of the Restoration. During the Interregnum, England was under various for ...

. When the college's first president Henry Dunster

Henry Dunster (November 26, 1609 (baptized) – February 27, 1658/59) was an Anglo-American Puritan clergyman and the first president of Harvard College. Brackney says Dunster was "an important precursor" of the Baptist denomination in America ...

abandoned Puritanism in favor of the English Baptist

Baptists form a major branch of Protestantism distinguished by baptizing professing Christian believers only ( believer's baptism), and doing so by complete immersion. Baptist churches also generally subscribe to the doctrines of soul c ...

faith in 1654, he provoked a controversy that highlighted two distinct approaches to dealing with dissent in the Massachusetts Bay Colony

The Massachusetts Bay Colony (1630–1691), more formally the Colony of Massachusetts Bay, was an English settlement on the east coast of North America around the Massachusetts Bay, the northernmost of the several colonies later reorganized as th ...

. The colony's Puritan leaders, whose own religion was born of dissent from mainstream Church of England, generally worked for reconciliation with members who questioned matters of Puritan theology, but responded much more harshly to outright rejection of Puritanism.

Dunster's conflict with the colony's magistrates began when he failed to have his infant son baptized, believing as an adherent of the Believers baptism of English Baptists and/or Anabaptists

Anabaptism (from Neo-Latin , from the Greek : 're-' and 'baptism', german: Täufer, earlier also )Since the middle of the 20th century, the German-speaking world no longer uses the term (translation: "Re-baptizers"), considering it biased. ...

that only adults should be baptized. Efforts to restore Dunster to Puritan orthodoxy failed and his apostasy proved untenable to colony leaders who had entrusted him in his job as Harvard's president to uphold the colony's religious mission, thus he represented a threat to the stability of society. Dunster exiled himself in 1654 and moved to nearby Plymouth Colony

Plymouth Colony (sometimes Plimouth) was, from 1620 to 1691, the first permanent English colony in New England and the second permanent English colony in North America, after the Jamestown Colony. It was first settled by the passengers on the ...

, where he died in 1658. Because it had been illegal for the colony to establish a college, Charles II rescinded the Massachusetts Bay Colony charter in 1684 by writ of scire facias

In English law, a writ of ''scire facias'' (Latin, meaning literally "make known") was a writ founded upon some judicial record directing the sheriff to make the record known to a specified party, and requiring the defendant to show cause why th ...

.

In 1692, the leading Puritan divine Increase Mather

Increase Mather (; June 21, 1639 Old Style – August 23, 1723 Old Style) was a New England Puritan clergyman in the Massachusetts Bay Colony and president of Harvard College for twenty years (1681–1701). He was influential in the admini ...

became president of Harvard. One of his acts was replacing pagan classics with books by Christian authors in ethics classes and maintaining a high standard of discipline. The Harvard "Lawes" of 1642 and the "Harvard College Laws of 1700" testify to its original high level of discipline. Students were required to observe rules of pious decorum inconceivable in the 19th century and ultimately to prove their fitness for the bachelor's degree by showing that they could "read the original of the Old and New Testament into the Latin tongue, and resolve them logically". Harvard's leadership and alumni (including Increase Mather and his son Cotton Mather) played a central role in the Salem Witch Trials

The Salem witch trials were a series of hearings and prosecutions of people accused of witchcraft in colonial Massachusetts between February 1692 and May 1693. More than 200 people were accused. Thirty people were found guilty, 19 of whom w ...

16921693.

The town of Dedham was founded in 1636, the same year as the college. The first minister of the First Church and Parish in Dedham

First or 1st is the ordinal form of the number 1 (number), one (#1).

First or 1st may also refer to:

*World record, specifically the first instance of a particular achievement

Arts and media Music

* 1$T, American rapper, singer-songwriter, D ...

, John Allen, served as an overseer, and every minister through 1861 was connected to the university. Given its population and modest means, the support the community provided to the college was generous. Allen donated two cows, presumably to provide milk for the president and tutors.

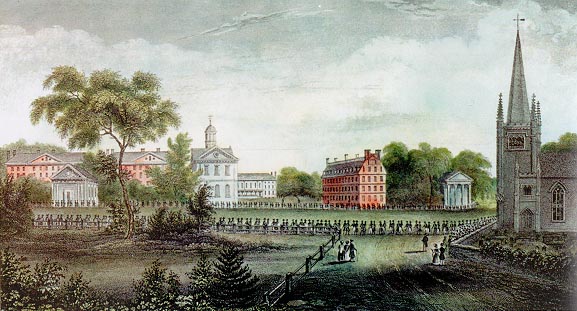

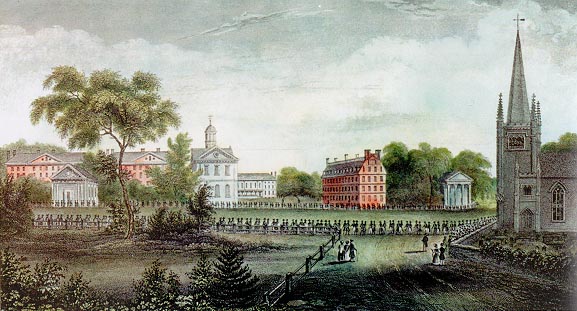

During Harvard's early years, the town of Cambridge maintained order on campus and provided economic support, as the local Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become more Protestant. ...

minister had direct oversight of Harvard and ensured the orthodoxy of its leadership. By 1700, Harvard was strong enough to regulate and discipline its own people and to a large extent the direction in which support and assistance flowed was reversed, Harvard now providing financial support for local economic expansion, improvements to public health and construction of local roads, meetinghouses and schools.

18th century

The early motto of Harvard was ''Veritas Christo et Ecclesiae'', meaning "Truth for Christ and the Church". In the early classes, half the graduates became ministers (though by the 1760s the proportion was down to 15%) and ten of Harvard's first twelve presidents were ministers. Systematic theological instruction was inaugurated in 1721 and by 1827 Harvard became a nucleus of theological teaching in New England. The end of Mather's presidency in 1701 marked the start of a long struggle between orthodoxy and liberalism. Harvard's first secular president was John Leverett, who began his term in 1708. Leverett left the curriculum largely intact and sought to keep the college independent of the overwhelming influence of any single sect. During the American Revolution,Loyalist

Loyalism, in the United Kingdom, its overseas territories and its former colonies, refers to the allegiance to the British crown or the United Kingdom. In North America, the most common usage of the term refers to loyalty to the British C ...

alumni were outnumbered seven to one by Patriots—seven alumni died in the fighting.

19th century

Unitarians

Throughout the 18th century, Enlightenment ideas of the power of reason and free will became widespread amongCongregational

Congregational churches (also Congregationalist churches or Congregationalism) are Protestant churches in the Calvinist tradition practising congregationalist church governance, in which each congregation independently and autonomously runs its ...

ministers, putting those ministers and their congregations in tension with more traditionalist, Calvinist

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John C ...

parties.Gary J. DorrienThe Making of American Liberal Theology: Imagining Progressive Religion, 1805–1900, Volume 1

. Westminster John Knox Press, 2001 When the

Hollis Professor of Divinity The Hollis Chair of Divinity is an endowed chair at Harvard Divinity School. It was established in 1721 by Thomas Hollis, a wealthy English merchant and benefactor of the university, at a salary of £80 per year. It is the oldest endowed chair in ...

David Tappan

David Tappan (1752–1803) was an American theologian. He occupied the Hollis Chair at Harvard Divinity School until his death in 1803. He was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

The American Academy of Arts and Sci ...

died in 1803 and the president of Harvard Joseph Willard died a year later, in 1804 a struggle broke out over their replacements. Henry Ware was elected to the chair in 1805 and the liberal Samuel Webber

Samuel Webber (1759 – July 17, 1810) was an American Congregational clergyman, mathematician, academic, and president of Harvard University from 1806 until his death in 1810.

Biography

Samuel Webber was born in Byfield, Massachusetts in 1759. ...

was appointed to the presidency of Harvard two years later, which signaled the changing of the tide from the dominance of traditional ideas at Harvard to the dominance of liberal, Arminian

Arminianism is a branch of Protestantism based on the theological ideas of the Dutch Reformed theologian Jacobus Arminius (1560–1609) and his historic supporters known as Remonstrants. Dutch Arminianism was originally articulated in the '' ...

ideas (defined by traditionalists as Unitarian ideas).

Science

In 1846, the natural history lectures ofLouis Agassiz

Jean Louis Rodolphe Agassiz ( ; ) FRS (For) FRSE (May 28, 1807 – December 14, 1873) was a Swiss-born American biologist and geologist who is recognized as a scholar of Earth's natural history.

Spending his early life in Switzerland, he rec ...

were acclaimed both in New York and on his campus at Harvard College. Agassiz's approach was distinctly idealist and posited Americans' "participation in the Divine Nature" and the possibility of understanding "intellectual existences". Agassiz's perspective on science combined observation with intuition and the assumption that one can grasp the "divine plan" in all phenomena. When it came to explaining life-forms, Agassiz resorted to matters of shape based on a presumed archetype for his evidence. This dual view of knowledge was in concert with the teachings of Common Sense Realism derived from Scottish philosophers Thomas Reid

Thomas Reid (; 7 May ( O.S. 26 April) 1710 – 7 October 1796) was a religiously trained Scottish philosopher. He was the founder of the Scottish School of Common Sense and played an integral role in the Scottish Enlightenment. In 1783 he wa ...

and Dugald Stewart

Dugald Stewart (; 22 November 175311 June 1828) was a Scottish philosopher and mathematician. Today regarded as one of the most important figures of the later Scottish Enlightenment, he was renowned as a populariser of the work of Francis Hut ...

, whose works were part of the Harvard curriculum at the time. The popularity of Agassiz's efforts to "soar with Plato" probably also derived from other writings to which Harvard students were exposed, including Platonic treatises by Ralph Cudworth, John Norris and in a Romantic vein Samuel Coleridge

Samuel Taylor Coleridge (; 21 October 177225 July 1834) was an English poet, literary critic, philosopher, and theologian who, with his friend William Wordsworth, was a founder of the Romantic Movement in England and a member of the Lake P ...

. The library records at Harvard reveal that the writings of Plato and his early modern and Romantic followers were almost as regularly read during the 19th century as those of the "official philosophy" of the more empirical and more deistic Scottish school.

Elitism

Between 1830 and 1870, Harvard became "privatized". While the Federalists controlled state government, Harvard had prospered and the 1824 defeat of the Federalist Party in Massachusetts allowed the renascentDemocratic-Republicans

The Democratic-Republican Party, known at the time as the Republican Party and also referred to as the Jeffersonian Republican Party among other names, was an American political party founded by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison in the ear ...

to block state funding of private universities. By 1870, the politicians and ministers that heretofore had made up the university's board of overseers had been replaced by Harvard alumni drawn from Boston's upper-class business and professional community and funded by private endowment.

During this period, Harvard experienced unparalleled growth that securely placed it financially in a league of its own among American colleges. Ronald Story notes that in 1850, Harvard's total assets were "five times that of Amherst and Williams combined, and three times that of Yale". Story also notes that "all the evidence... points to the four decades from 1815 to 1855 as the era when parents, in Henry Adams's words, began 'sending their children to Harvard College for the sake of its social advantages'". Under President Eliot's tenure, Harvard earned a reputation for being more liberal and democratic than either

During this period, Harvard experienced unparalleled growth that securely placed it financially in a league of its own among American colleges. Ronald Story notes that in 1850, Harvard's total assets were "five times that of Amherst and Williams combined, and three times that of Yale". Story also notes that "all the evidence... points to the four decades from 1815 to 1855 as the era when parents, in Henry Adams's words, began 'sending their children to Harvard College for the sake of its social advantages'". Under President Eliot's tenure, Harvard earned a reputation for being more liberal and democratic than either Princeton

Princeton University is a private research university in Princeton, New Jersey. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and one of the nin ...

or Yale

Yale University is a private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and among the most prestigious in the wor ...

in regard to bigotry against Jews and other ethnic minorities. In 1870, one year into Eliot's term, Richard Theodore Greener

Richard Theodore Greener (1844–1922) was a pioneering African Americans, African-American scholar, excelling in elocution, philosophy, law and classics in the Reconstruction era. He broke ground as Harvard College's first Black graduate in 18 ...

became the first African-American to graduate from Harvard College. Seven years later, Louis Brandeis

Louis Dembitz Brandeis (; November 13, 1856 – October 5, 1941) was an American lawyer and associate justice on the Supreme Court of the United States from 1916 to 1939.

Starting in 1890, he helped develop the " right to privacy" concep ...

, the first Jewish justice on the Supreme Court

A supreme court is the highest court within the hierarchy of courts in most legal jurisdictions. Other descriptions for such courts include court of last resort, apex court, and high (or final) court of appeal. Broadly speaking, the decisions of ...

, graduated from Harvard Law School. Nevertheless, Harvard became the bastion of a distinctly Protestant élite – the so-called Boston Brahmin

The Boston Brahmins or Boston elite are members of Boston's traditional upper class. They are often associated with Harvard University; Anglicanism; and traditional Anglo-American customs and clothing. Descendants of the earliest English coloni ...

class – and continued to be so well into the 20th century.

The annual undergraduate tuition was $300 in the 1930s and $400 in the 1940s, doubling to $800 in 1953. It reached $2,600 in 1970 and $22,700 in 2000.

The annual undergraduate tuition was $300 in the 1930s and $400 in the 1940s, doubling to $800 in 1953. It reached $2,600 in 1970 and $22,700 in 2000.

Eliot

Charles W. Eliot, president 1869–1909, eliminated the favored position of Christianity from the curriculum while opening it to student self-direction. While Eliot was the most crucial figure in the secularization of American higher education, he was motivated not by a desire to secularize education, but by transcendentalist Unitarian convictions. Derived fromWilliam Ellery Channing

William Ellery Channing (April 7, 1780 – October 2, 1842) was the foremost Unitarian preacher in the United States in the early nineteenth century and, along with Andrews Norton (1786–1853), one of Unitarianism's leading theologians. Channi ...

and Ralph Waldo Emerson

Ralph Waldo Emerson (May 25, 1803April 27, 1882), who went by his middle name Waldo, was an American essayist, lecturer, philosopher, abolitionist, and poet who led the transcendentalist movement of the mid-19th century. He was seen as a cham ...

, these convictions were focused on the dignity and worth of human nature, the right and ability of each person to perceive truth and the indwelling God in each person.

Sports

Football, originally organized by students as an extracurricular activity, was banned twice by the university for being a brutal and dangerous sport. However, by the 1880s football became a dominant force at the college as the alumni became more involved in the sport. In 1882, the faculty formed a three-member athletic committee to oversee all intercollegiate athletics, but due to increasing student and alumni pressure the committee was expanded in 1885 to include three student and three alumni members. The alumni's role in the rise and commercialization of football, the leading moneymaker for athletics by the 1880s, was evident in the fundraising for the first steel-reinforced concrete stadium. The class of 1879 donated $100,000 – nearly one-third of the cost – to the construction of the 35,000-seat stadium, which was completed in 1903, with the remainder to be collected from future ticket sales.Language Studies

Programs in the study ofFrench

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

and Spanish

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

**Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many Latin American countries

**Spanish cuisine

Other places

* Spanish, Ontario, Can ...

languages began in 1816 with George Ticknor

George Ticknor (August 1, 1791 – January 26, 1871) was an American academician and Hispanist, specializing in the subject areas of languages and literature. He is known for his scholarly work on the history and criticism of Spanish literature.

...

as its first professor.

Graduate schools

Medical School

The school, the third-oldest medical school in the United States, was founded in 1782 as Massachusetts Medical College by John Warren,Benjamin Waterhouse

Benjamin Waterhouse (March 4, 1754, Newport, Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations – October 2, 1846, Cambridge, Massachusetts) was a physician, co-founder and professor of Harvard Medical School. He is most well known for being ...

and Aaron Dexter. It relocated from Cambridge across the river to Boston in 1810. The medical school was tied to the rest of the university "only by the tenuous thread of degrees", but its strong faculty gave it a national reputation by the early 19th century.

The medical school moved to its current location on Longwood Avenue in 1906, where the "Great White Quadrangle" or HMS Quad with its five white marble buildings was established.

The reputation continued to grow into the 20th century, especially in terms of scientific research and support from regional and national elites. Fifteen scientists won the Nobel Prize for work done at the Medical School. Its four major flagship teaching hospitals are Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center

Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) in Boston, Massachusetts is a teaching hospital of Harvard Medical School. It was formed out of the 1996 merger of Beth Israel Hospital (founded in 1916) and New England Deaconess Hospital (founde ...

, Brigham and Women's Hospital

Brigham and Women's Hospital (BWH) is the second largest teaching hospital of Harvard Medical School and the largest hospital in the Longwood Medical Area in Boston, Massachusetts. Along with Massachusetts General Hospital, it is one of the two ...

, Boston Children's Hospital

Boston Children's Hospital formerly known as Children's Hospital Boston until 2012 is a nationally ranked, freestanding acute care children's hospital located in Boston, Massachusetts, adjacent both to its teaching affiliate, Harvard Medical Scho ...

and Massachusetts General Hospital

Massachusetts General Hospital (Mass General or MGH) is the original and largest teaching hospital of Harvard Medical School located in the West End neighborhood of Boston, Massachusetts. It is the third oldest general hospital in the United Stat ...

.

Law School

The establishment of Harvard Law School in 1817 was made possible by a 1779 bequest from Isaac Royall Jr.; it is the oldest continuously operating law school in the nation. It was a small operation and grew slowly. By 1827, it was down to one faculty member.Nathan Dane

Nathan Dane (December 29, 1752 – February 15, 1835) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented Massachusetts in the Continental Congress from 1785 through 1788. Dane helped formulate the Northwest Ordinance while in Congress, and ...

, a prominent alumnus, endowed the Dane Professorship of Law and insisting that it be given to then Supreme Court Justice Joseph Story

Joseph Story (September 18, 1779 – September 10, 1845) was an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, serving from 1812 to 1845. He is most remembered for his opinions in ''Martin v. Hunter's Lessee'' and '' United States ...

. For a while, the school was called Dane Law School. Story's belief in the need for an elite law school based on merit and dedicated to public service helped build the school's reputation at the time. Enrollment remained low as academic legal education was considered to be of little added benefit to apprenticeships in legal practice.

Radical reform came in the 1870s, under Dean Christopher Columbus Langdell

Christopher Columbus Langdell (May 22, 1826 – July 6, 1906) was an American jurist and legal academic who was Dean of Harvard Law School from 1870 to 1895.

Dean Langdell's legacy lies in the educational and administrative reforms he made to Ha ...

(1826–1906). Its new curriculum set the national standard and was copied widely in the United States. Langdell developed the case method The case method is a teaching approach that uses decision-forcing cases to put students in the role of people who were faced with difficult decisions at some point in the past. It developed during the course of the twentieth-century from its origin ...

of teaching law, based on his belief that law could be studied as a "science" gave university legal education a reason for being distinct from vocational preparation. The school introduced a first-year curriculum that was widely imitated, based on classes in contracts

A contract is a legally enforceable agreement between two or more parties that creates, defines, and governs mutual rights and obligations between them. A contract typically involves the transfer of goods, services, money, or a promise to tr ...

, property

Property is a system of rights that gives people legal control of valuable things, and also refers to the valuable things themselves. Depending on the nature of the property, an owner of property may have the right to consume, alter, share, r ...

, torts

A tort is a civil wrong that causes a claimant to suffer loss or harm, resulting in legal liability for the person who commits the tortious act. Tort law can be contrasted with criminal law, which deals with criminal wrongs that are punishab ...

, criminal law

Criminal law is the body of law that relates to crime. It prescribes conduct perceived as threatening, harmful, or otherwise endangering to the property, health, safety, and moral welfare of people inclusive of one's self. Most criminal law ...

and civil procedure

Civil procedure is the body of law that sets out the rules and standards that courts follow when adjudicating civil lawsuits (as opposed to procedures in criminal law matters). These rules govern how a lawsuit or case may be commenced; what kin ...

.

Critics bemoaned abandonment of the more traditional lecture method, because of its efficiency and the lower workloads it placed on faculty and students. Advocates of the case method had a sounder theoretical basis in scientific research and the inductive method. Langdell's graduates became leading professors at other law schools where they introduced the case method. From its founding in 1900, the Association of American Law Schools promoted the case method in law schools that sought accreditation.

Graduate school

As the college modernized in the late 19th century, the faculty was organized into departments and began to add graduate programs, especially the PhD.Charles William Eliot

Charles William Eliot (March 20, 1834 – August 22, 1926) was an American academic who was president of Harvard University from 1869 to 1909the longest term of any Harvard president. A member of the prominent Eliot family of Boston, he transfor ...

, president from 1869 to 1909, was a chemist who had spent two years in Germany studying their universities. Thousands of Americans, mostly Harvard and Yale alumni, had attended German universities, especially Berlin and Göttingen. Eliot used the German model to set up graduate programs at Harvard and he formed a graduate department in 1872, which granted its first Ph.D. degrees in 1873 to William Byerly in mathematics and Charles Whitney in history. Eliot set up the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences with its own dean and budget in 1890, which dealt with graduate students and funded research programs.

By 2004, there were 3,200 graduate students in 53 separate programs and forty former or current professors had won a Nobel Prize, most of them scientists or economists based in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences.

Business school

From its beginning in 1908, the Harvard Business School had a close relationship with the corporate world. Within a few years of its founding many business leaders were its alumni and were hiring other alumni for starting positions in their firms. The School used Rockefeller funding in the 1920s to launch a major research program underElton Mayo

George Elton Mayo (26 December 1880 – 7 September 1949) was an Australian born psychologist, industrial researcher, and organizational theorist.Cullen, David O'Donald. ''A new way of statecraft: The career of Elton Mayo and the development ...

(1926–1947) for his "Harvard human relations group". Its findings revolutionized human relations in business and raised the reputation of the Business School from its initial "low status as a trainer of money grabbers into a high prestige educator of socially-conscientious administrators". Starting in 1935, the school began weekend and short-term leadership training workshops for executives of major corporations that further expanded its national role.

By 1949, almost half of all the holders of the MBA degree in the U.S. were alumni of the Business School and it was "the most influential graduate school of business".

Harvard Kennedy School

In 1936, Harvard University founded the Harvard Graduate School of Public Administration, later renamedHarvard Kennedy School

The Harvard Kennedy School (HKS), officially the John F. Kennedy School of Government, is the school of public policy and government of Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The school offers master's degrees in public policy, publi ...

in honor of former U.S. President and 1940 Harvard College

Harvard College is the undergraduate college of Harvard University, an Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636, Harvard College is the original school of Harvard University, the oldest institution of higher ...

alumnus John F. Kennedy.

The Kennedy School has an endowment of $1.7 billion as of 2021 and is routinely ranked at the top of the world's graduate schools in public policy, social policy, international affairs, and government.

Its alumni include 17 heads of state

A head of state (or chief of state) is the public persona who officially embodies a state Foakes, pp. 110–11 " he head of statebeing an embodiment of the State itself or representatitve of its international persona." in its unity and ...

or government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive, and judiciary. Government i ...

.

20th century

During the 20th century, Harvard's international reputation for scholarship grew as a burgeoning endowment and prominent professors expanded the university's scope. Explosive growth in the student population continued with the addition of new graduate schools and the expansion of the undergraduate program. It built the largest and finest academic library in the world and built up the labs and clinics needed to establish the reputation of its science departments and theMedical School

A medical school is a tertiary educational institution, or part of such an institution, that teaches medicine, and awards a professional degree for physicians. Such medical degrees include the Bachelor of Medicine, Bachelor of Surgery (MBBS, ...

. The Law School

A law school (also known as a law centre or college of law) is an institution specializing in legal education, usually involved as part of a process for becoming a lawyer within a given jurisdiction.

Law degrees Argentina

In Argentina, ...

vied with Yale Law for preeminence, while the Business School

A business school is a university-level institution that confers degrees in business administration or management. A business school may also be referred to as school of management, management school, school of business administration, or ...

combined a large-scale research program with a special appeal to entrepreneurs rather than accountants. The different schools maintain their separate endowments, which are very large in the case of the college/Faculty of Arts and Sciences, and the Business, Law and Medical Schools, but quite modest for the Divinity and Education schools.

Radcliffe College

Radcliffe College was a women's liberal arts college in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and functioned as the female coordinate institution for the all-male Harvard College. Considered founded in 1879, it was one of the Seven Sisters colleges and h ...

, established in 1879 as sister school of Harvard College, became one of the most prominent schools for women in the United States. In the 1920s Edward Harkness

Edward Stephen Harkness (January 22, 1874 – January 29, 1940) was an American philanthropist. Given privately and through his family's Commonwealth Fund, Harkness' gifts to private hospitals, art museums, and educational institutions in the Nort ...

(1874–1940), a Yale man with oil wealth, was ignored by his alma mater and so gave $12,000,000 to Harvard to establish a house system like that of Oxford University. Yale later took his money and set up a similar system.

In addition to the usual department, specialized research centers proliferated, especially to enable interdisciplinary research projects that could not be handled at the department level. However, the departments kept jealous control of the awarding of tenure; typically tenured professorships went to outsiders, and not as promotions to assistant professors. Older research centers include the East Asian Research Center, the Center for International Affairs, the Center for Eastern Studies, the Russian Research Center, the Charles Warren Center for Studies in American History and the Joint Center for Urban Studies (with MIT

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) is a private land-grant research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Established in 1861, MIT has played a key role in the development of modern technology and science, and is one of the m ...

). The Centers raised their own money, sometimes from endowments, but most often from federal and foundation grants, making them increasingly independent entities.

During World War II, Harvard was one of 131 colleges and universities nationally that took part in the V-12 Navy College Training Program

The V-12 Navy College Training Program was designed to supplement the force of commissioned officers in the United States Navy during World War II. Between July 1, 1943, and June 30, 1946, more than 125,000 participants were enrolled in 131 colleg ...

which offered students a path to a Navy commission.

The annual undergraduate tuition was $300 in the 1920s and $400 in the 1930s, doubling to $800 in 1953. It reached $2,600 in 1970 and $22,700 in 2000.

Meritocracy

James Bryant Conant

James Bryant Conant (March 26, 1893 – February 11, 1978) was an American chemist, a transformative President of Harvard University, and the first U.S. Ambassador to West Germany. Conant obtained a Ph.D. in Chemistry from Harvard in 1916 ...

(president, 1933–1953) pledged to reinvigorate creative scholarship at Harvard and reestablish its preeminence among research institutions. Viewing higher education as a vehicle of opportunity for the talented rather than an entitlement for the wealthy, Conant devised programs to identify, recruit, and support talented youth. In 1943, Conant decided that Harvard's undergraduate curriculum needed to be revised so as to place more emphasis on general education and called on the faculty make a definitive statement about what general education ought to be at the secondary as well as the college level. The resulting ''Report'', published in 1945, was one of the most influential manifestos in the history of American education in the 20th century.

In the decades immediately after 1945, Harvard reformed its admissions policies as it sought students from a more diverse applicant pool. Whereas Harvard undergraduates had almost exclusively been upper-class alumni of select New England "feeder schools" such as Exeter

Exeter () is a city in Devon, South West England. It is situated on the River Exe, approximately northeast of Plymouth and southwest of Bristol.

In Roman Britain, Exeter was established as the base of Legio II Augusta under the personal comm ...

, Hotchkiss

Hotchkiss may refer to:

Places Canada

* Hotchkiss, Alberta

* Hotchkiss, Calgary

United States

* Hotchkiss, Colorado

* Hotchkiss, Virginia

* Hotchkiss, West Virginia

Business and industry

* Hotchkiss (car), a French automobile manufacturer ...

, Choate Rosemary Hall

Choate Rosemary Hall (often known as Choate; ) is a private, co-educational, college-preparatory boarding school in Wallingford, Connecticut, United States. Choate is currently ranked as the second best boarding school and third best private hig ...

and Milton Academy

Milton Academy (also known as Milton) is a highly selective, coeducational, independent preparatory, boarding and day school in Milton, Massachusetts consisting of a grade 9–12 Upper School and a grade K–8 Lower School. Boarding is offered ...

, increasing numbers of international, minority and working-class students had by the late 1960s altered the ethnic and socio-economic makeup of the college.

Not just undergraduates, but the faculty became more diverse, especially in its willingness to hire Jews, Catholics and foreign scholars. The History Department was among the first to hire Jews and how it contributed to the university trend toward professionalism from 1920 to 1950. Oscar Handlin

Oscar Handlin (1915–2011) was an American historian. As a professor of history at Harvard University for over 50 years, he directed 80 PhD dissertations and helped promote social and ethnic history, virtually inventing the field of immigrat ...

became one of the most influential professors, training hundreds of graduate students and later serving as head of the University Library.

During the 20th century, Harvard's international reputation grew as a burgeoning endowment and prominent professors expanded the university's scope. Explosive growth in the student population continued with the addition of new graduate schools and the expansion of the undergraduate program.

Women

In 1945,Harvard Medical School

Harvard Medical School (HMS) is the graduate medical school of Harvard University and is located in the Longwood Medical Area of Boston, Massachusetts. Founded in 1782, HMS is one of the oldest medical schools in the United States and is cons ...

admitted its first class of women after a special committee concluded that male students would benefit from learning to view women as equals, that the lower-paid specialties typically shunned by men would benefit from the talents of women doctors and that the weakest third of each entering class of men could be replaced by a superior group of women.

For its first fifty years the undergraduate Radcliffe College

Radcliffe College was a women's liberal arts college in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and functioned as the female coordinate institution for the all-male Harvard College. Considered founded in 1879, it was one of the Seven Sisters colleges and h ...

, established in 1879 as the "Harvard Annex for Women", paid Harvard faculty to repeat their lectures for a female audience. During World War II, male and female undergraduates attended classes together for the first time, though it was many decades before the population of Radcliffe College reached parity with that of Harvard. In the 1970s, two agreements between Harvard and Radcliffe made Harvard responsible for essentially all undergraduate matters for women – including admissions, advising, instruction, housing, student life and athletics – though women were still formally admitted to and graduated from Radcliffe until a final merger in 1979 made Radcliffe a part of Harvard, at the same time creating the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study

The Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard University—also known as the Harvard Radcliffe Institute—is a part of Harvard University that fosters interdisciplinary research across the humanities, sciences, social sciences, arts, a ...

.

In 2006, Lawrence Summers

Lawrence Henry Summers (born November 30, 1954) is an American economist who served as the 71st United States secretary of the treasury from 1999 to 2001 and as director of the National Economic Council from 2009 to 2010. He also served as pres ...

resigned his presidency after suggesting that women's underrepresentation in top science positions could be due to differences in "intrinsic aptitude".

In 1984, Harvard severed ties with undergraduate " final clubs" because of their refusal to admit women. As of 2016, Harvard bars members of single-sex organizations (such as final clubs, fraternities and sororities) from campus leadership positions such as team captaincies and from receiving recommendation letters from Harvard requisite for scholarships and fellowships such as the Marshall Scholarship

The Marshall Scholarship is a postgraduate scholarship for "intellectually distinguished young Americans ndtheir country's future leaders" to study at any university in the United Kingdom. It is widely considered one of the most prestigious sc ...

and Rhodes Scholarship

The Rhodes Scholarship is an international postgraduate award for students to study at the University of Oxford, in the United Kingdom.

Established in 1902, it is the oldest graduate scholarship in the world. It is considered among the world' ...

.Stephanie Saul. (2016Harvard Restrictions Could Reshape Exclusive Student Clubs

, The New York Times, May 6, 2016 After the Supreme Court ruled in

Bostock v. Clayton County

''Bostock v. Clayton County'', , is a landmark United States Supreme Court civil rights case in which the Court held that Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 protects employees against discrimination because they are gay or transgender.

...

in June 2020, Harvard independently reversed the sanctions policy.

Minorities

Lawrence Summers

Lawrence Henry Summers (born November 30, 1954) is an American economist who served as the 71st United States secretary of the treasury from 1999 to 2001 and as director of the National Economic Council from 2009 to 2010. He also served as pres ...

characterized the 1920 episode as "part of a past that we have rightly left behind" and "abhorrent and an affront to the values of our university". As late as the 1950s, Wilbur Bender, then the dean of admissions for Harvard College, was seeking better ways to "detect homosexual tendencies and serious psychiatric problems" in prospective students.Malcolm Gladwell. (2005)Getting In

.

The New Yorker

''The New Yorker'' is an American weekly magazine featuring journalism, commentary, criticism, essays, fiction, satire, cartoons, and poetry. Founded as a weekly in 1925, the magazine is published 47 times annually, with five of these issues ...

, October 10, 2005

See also

*History and traditions of Harvard commencements

What was originally called '

(around which Harvard University eventually grew) held its first Commencement in September 1642, when nine degrees were conferred.

Today some 1700 undergraduate degrees, and 5000 advanced degrees from the universit ...

* Harvard University and the Vietnam War

References

Works cited

*Further reading

* Abelmann, Walter H., ed. ''The Harvard-MIT Division of Health Sciences and Technology: The First 25 Years, 1970–1995'' (2004). 346 pp. * Bailyn, Bernard, et al. ''Glimpses of the Harvard Past'' (1986). 149 pp. * Beecher, Henry K. and Altschule, Mark D. ''Medicine at Harvard: The First 300 Years'' (1977). 569 pp. * Bentinck-Smith, William, ed. ''The Harvard Book: Selections from Three Centuries'' (2d ed.1982). 499 pp. * Bentinck-Smith, William. ''Building a Great Library: The Coolidge Years at Harvard'' (1976). 218 pp. * * Bethell, John T. ''Harvard Observed: An Illustrated History of the University in the Twentieth Century'', Harvard University Press, 1998, * Bunting, Bainbridge. ''Harvard: An Architectural History'' (1985). 350 pp. * Carpenter, Kenneth E. ''The First 350 Years of the Harvard University Library: Description of an Exhibition'' (1986). 216 pp. * Cruikshank, Jeffrey L. ''A Delicate Experiment: The Harvard Business School. 1908–1945'' (1987). 303 pp. * Cuno, James et al. ''Harvard's Art Museums: 100 Years of Collecting'' (1996). 364 pp. * Elliott, Clark A. and Rossiter, Margaret W., eds. ''Science at Harvard University: Historical Perspectives'' (1992). 380 pp. * Hall, Max. ''Harvard University Press: A History'' (1986). 257 pp. * Harvard U. ''Education, Bricks and Mortar: Harvard Buildings and Their Contribution to the Advancement of Learning'' (1949online edition

* Hawkins, Hugh. ''Between Harvard and America: The Educational Leadership of Charles W. Eliot'' (1972). 404 pp. * Hay, Ida. ''Science in the Pleasure Ground: A History of the Arnold Arboretum'' (1995). 349 pp. * Hoerr, John, ''We Can't Eat Prestige: The Women Who Organized Harvard;''

Temple University Press

Temple University Press is a university press founded in 1969 that is part of Temple University (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania). It is one of thirteen publishers to participate in the Knowledge Unlatched pilot, a global library consortium approach ...

, 1997,

* Howells, Dorothy Elia. ''A Century to Celebrate: Radcliffe College, 1879–1979'' (1978). 152 pp.

* James, Henry. ''Charles W. Eliot: President of Harvard University, 1869–1909'' (1930online edition

* Keller, Morton, and Phyllis Keller. ''Making Harvard Modern: The Rise of America's University'' (2001), major history covers 1933 to 200

online edition

* King, Moses

''Harvard and its surroundings''

Cambridge, Massachusetts : Moses King, 1884 * Kuklick, Bruce. ''The Rise of American Philosophy: Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1860–1930'' (1977). 674 pp. * LaPiana, William P. ''Logic and Experience: The Origin of Modern American Legal Education'', (1994). 254 pp. on reforms by

Christopher Columbus Langdell

Christopher Columbus Langdell (May 22, 1826 – July 6, 1906) was an American jurist and legal academic who was Dean of Harvard Law School from 1870 to 1895.

Dean Langdell's legacy lies in the educational and administrative reforms he made to Ha ...

, at the law school

* Lawless, Greg. ''The Harvard Crimson Anthology: 100 Years at Harvard'' (1980).

* Lewis, Harry R. '' Excellence Without a Soul: How a Great University Forgot Education'' (2006)

* Lipset, Seymour Martin and Riesman, David. ''Education and Politics at Harvard'' (1975). 440 pp.

*

* Powell, Arthur G. ''The Uncertain Profession: Harvard and the Search for Educational Authority'' (1980). 341 pp.

* Reid, Robert. ''Year One: An Intimate Look inside Harvard Business School'' (1994). 331 pp.

* Rosenblatt, Roger. ''Coming Apart: A Memoir of the Harvard Wars of 1969'' (1997). 234 pp. student unrest

* Rosovsky, Nitza. ''The Jewish Experience at Harvard and Radcliffe'' (1986). 108 pp.

* Seligman, Joel. ''The High Citadel: The Influence of Harvard Law School'' (1978). 262 pp.

* Shipton, Clifford K. ''Sibley's Harvard Graduates: Biographical Sketches of Those Who Attended Harvard College.'' (1999) 19 vol to the class of 1774

* Sollors, Werner; Titcomb, Caldwell; and Underwood, Thomas A., eds. ''Blacks at Harvard: A Documentary History of African-American Experience at Harvard and Radcliffe'' (1993). 548 pp.

* Story, R. ''The Forging of an Aristocracy: Harvard and the Boston Upper Class, 1800–1870'', Middletown, Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press

Wesleyan University Press is a university press that is part of Wesleyan University in Middletown, Connecticut. The press is currently directed by Suzanna Tamminen, a published poet and essayist.

History and overview

Founded (in its present form ...

, 1981

* Townsend, Kim. ''Manhood at Harvard: William James and Others'' (1996). 318 pp.

* Trumpbour, John, ed., ''How Harvard Rules. Reason in the Service of Empire'', Boston: South End Press, 1989,

* Ulrich, Laurel Thatcher, ed. ''Yards and Gates: Gender in Harvard and Radcliffe History'' (2004). 337 pp.

* Whitehead, John S. ''The Separation of College and State: Columbia, Dartmouth, Harvard, and Yale, 1776–1876'' (1973). 262 pp.

* Winsor, Mary P. ''Reading the Shape of Nature: Comparative Zoology at the Agassiz Museum'' (1991). 324 pp.

* Wright, Conrad Edick. ''Revolutionary Generation: Harvard Men and the Consequences of Independence'' (2005). 298 pp.

{{DEFAULTSORT:History Of Harvard University

harvard

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher le ...