History of Dalmatia on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The History of

The province of

The province of  In 468 Flavius Julius Nepos became the ruler of the Province of Dalmatia. Four years later, in the spring of 472, the Western Emperor Anthemius was murdered by his Germanic general Ricimer; the appointment of his successor legally fell to Emperor

In 468 Flavius Julius Nepos became the ruler of the Province of Dalmatia. Four years later, in the spring of 472, the Western Emperor Anthemius was murdered by his Germanic general Ricimer; the appointment of his successor legally fell to Emperor

The area of Southern Dalmatia was divided among four small principalities called Pagania,

The area of Southern Dalmatia was divided among four small principalities called Pagania,

As the Dalmatian city states gradually lost all protection by Byzantium, being unable to unite in a defensive league hindered by their internal dissensions, they had to turn to either

As the Dalmatian city states gradually lost all protection by Byzantium, being unable to unite in a defensive league hindered by their internal dissensions, they had to turn to either  The rule of Venice on most of Dalmatia will last nearly four centuries (1420 - 1797).

The rule of Venice on most of Dalmatia will last nearly four centuries (1420 - 1797).

Other languages influenced Dalmatian, but without erasing its Latin roots (superstrates): the Slavs, then the

Other languages influenced Dalmatian, but without erasing its Latin roots (superstrates): the Slavs, then the

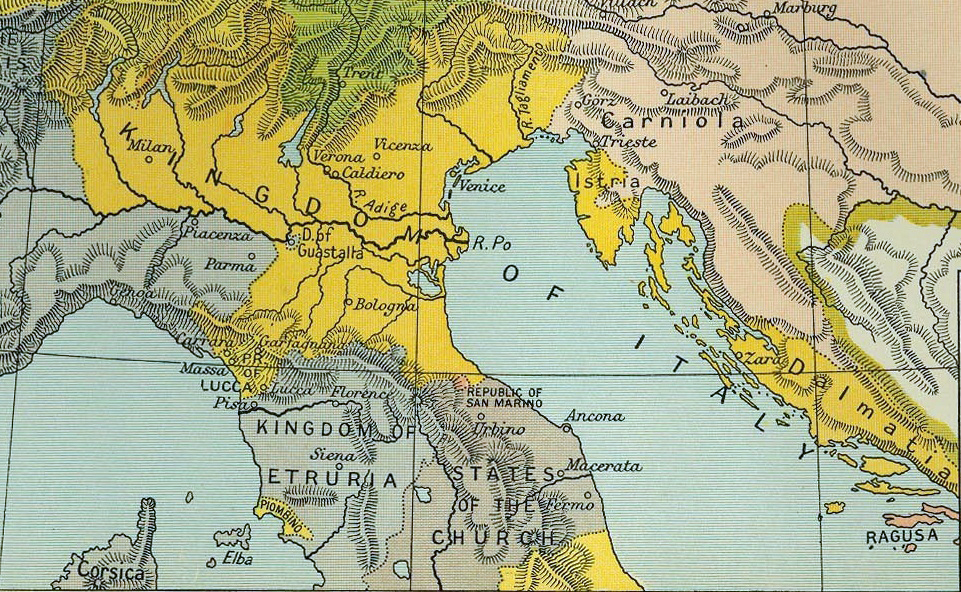

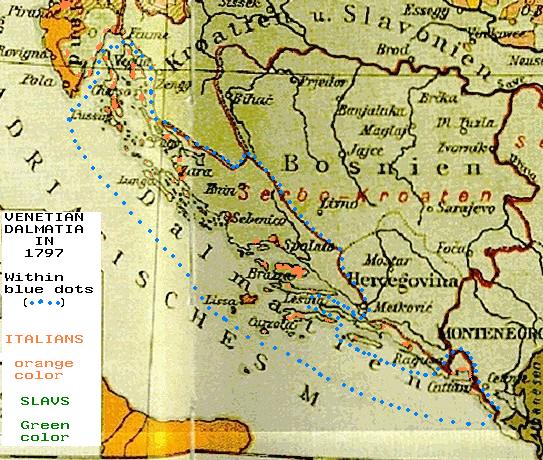

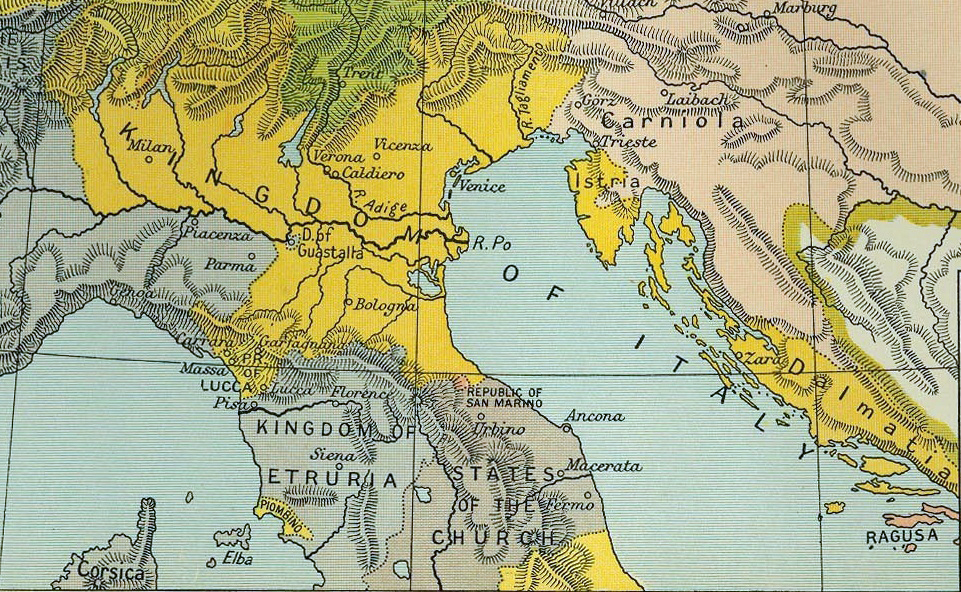

The Venetian rule in Dalmatia lasted from 1420 to 1797.

An interval of peace ensued, but meanwhile the Ottoman advance continued.

Hungary was itself assailed by the Turks, and could no longer afford to try to control Dalmatia. Christian kingdoms and regions in the east fell one by one,

The Venetian rule in Dalmatia lasted from 1420 to 1797.

An interval of peace ensued, but meanwhile the Ottoman advance continued.

Hungary was itself assailed by the Turks, and could no longer afford to try to control Dalmatia. Christian kingdoms and regions in the east fell one by one,

Later in 1797, in the

Later in 1797, in the

Many Dalmatian Italians looked with sympathy towards the

Many Dalmatian Italians looked with sympathy towards the

"Capitolo 1980-1918"

, Capodistria, 2000 During the meeting of the Council of Ministers of 12 November 1866, Emperor

When the Croatian Banate was in 1939 formed, the biggest part of Dalmatia was in it.

In April 1941, during

When the Croatian Banate was in 1939 formed, the biggest part of Dalmatia was in it.

In April 1941, during

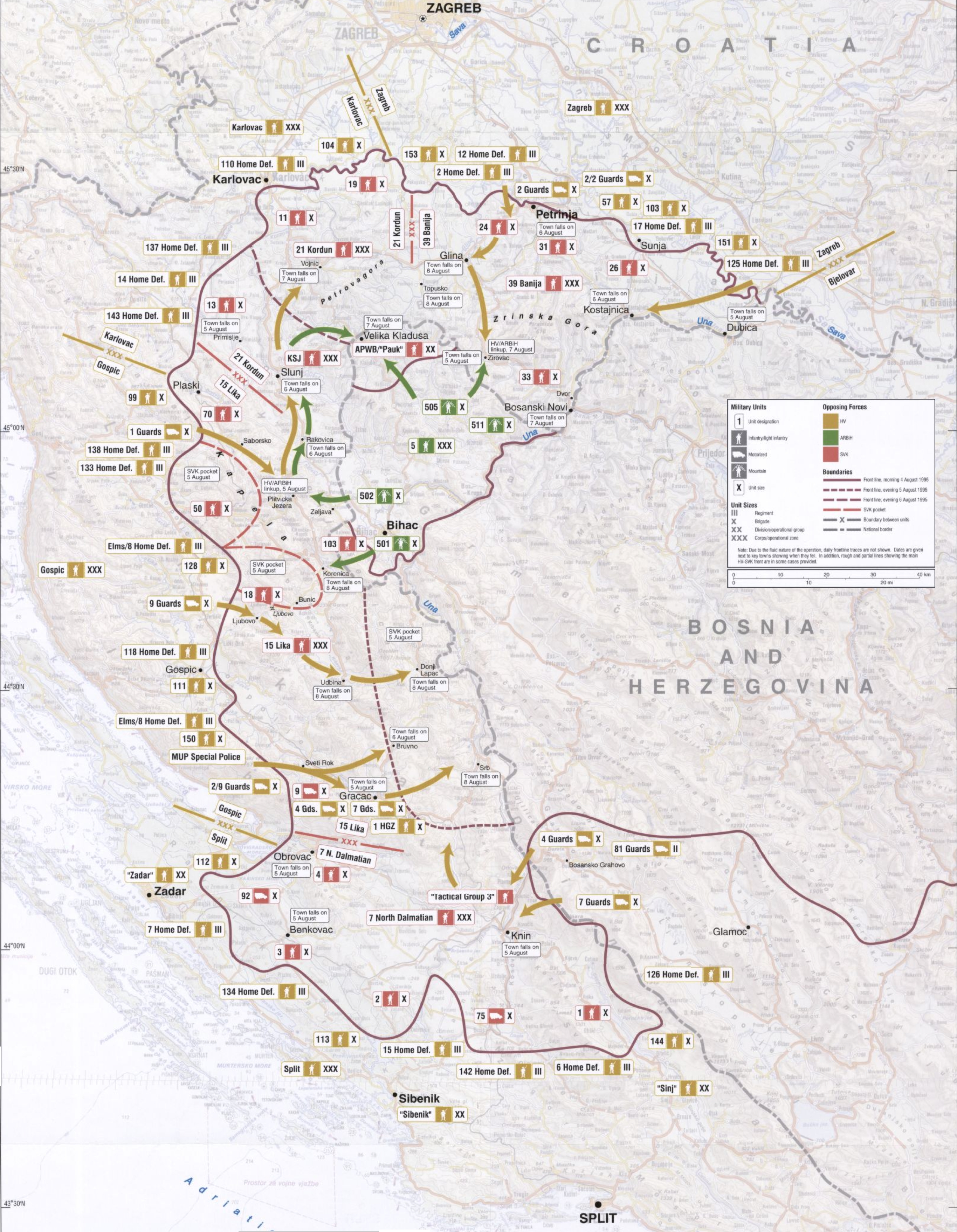

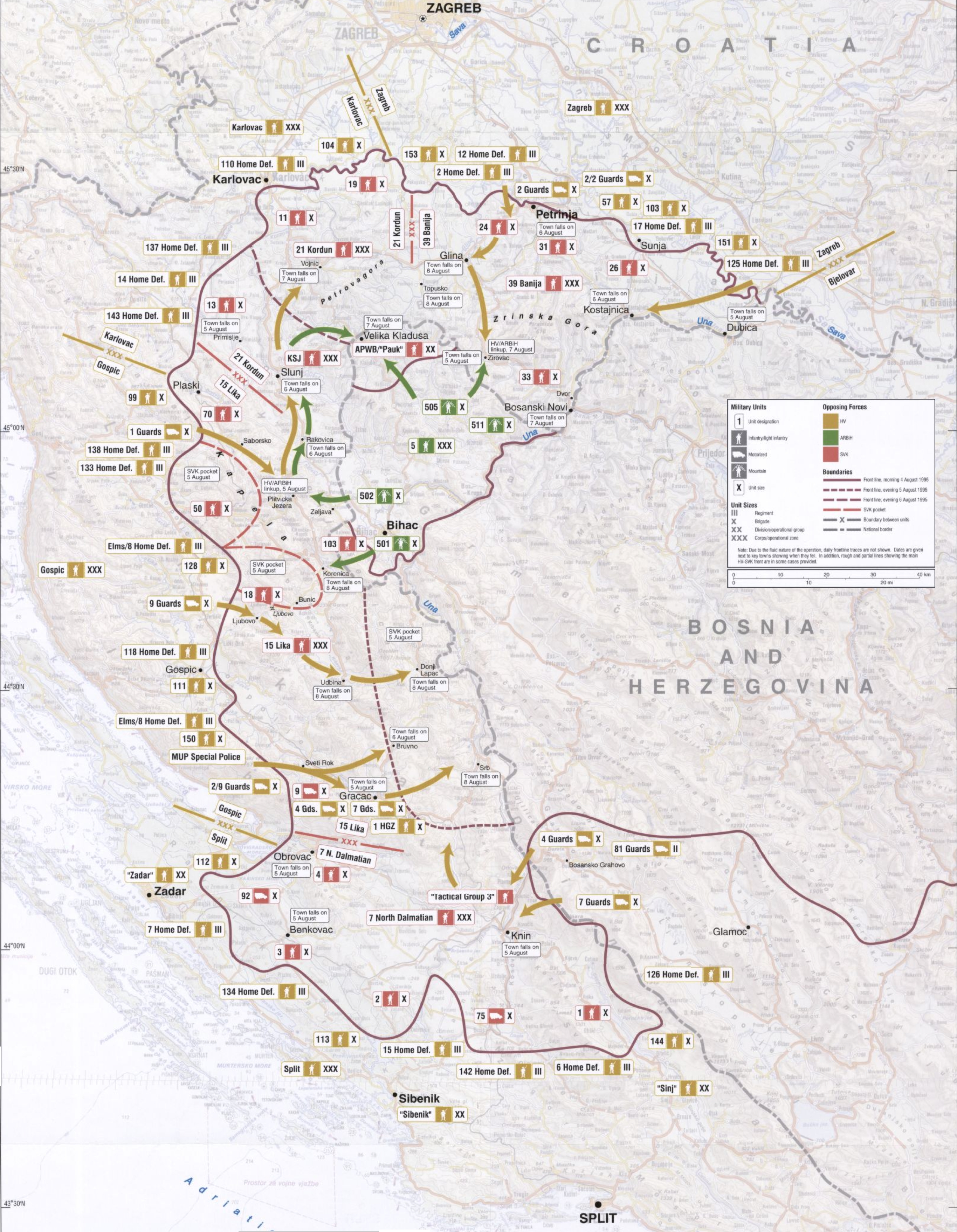

The Croatian government gradually restored control over all of Dalmatia, in the following military operations:

* September 1991: '' September War for Šibenik'' - successful defence of

The Croatian government gradually restored control over all of Dalmatia, in the following military operations:

* September 1991: '' September War for Šibenik'' - successful defence of

Google Books

*

WHKMLA History of Dalmatia

*The 1908 Catholic Encyclopedia articles on Dalmatia

{{DEFAULTSORT:History Of Dalmatia

Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; hr, Dalmacija ; it, Dalmazia; see names in other languages) is one of the four historical regions of Croatia, alongside Croatia proper, Slavonia, and Istria. Dalmatia is a narrow belt of the east shore of the Adriatic Sea, str ...

concerns the history of the area that covers eastern coast of the Adriatic Sea

The Adriatic Sea () is a body of water separating the Italian Peninsula from the Balkan Peninsula. The Adriatic is the northernmost arm of the Mediterranean Sea, extending from the Strait of Otranto (where it connects to the Ionian Sea) to th ...

and its inland regions, from the 2nd century BC up to the present day.

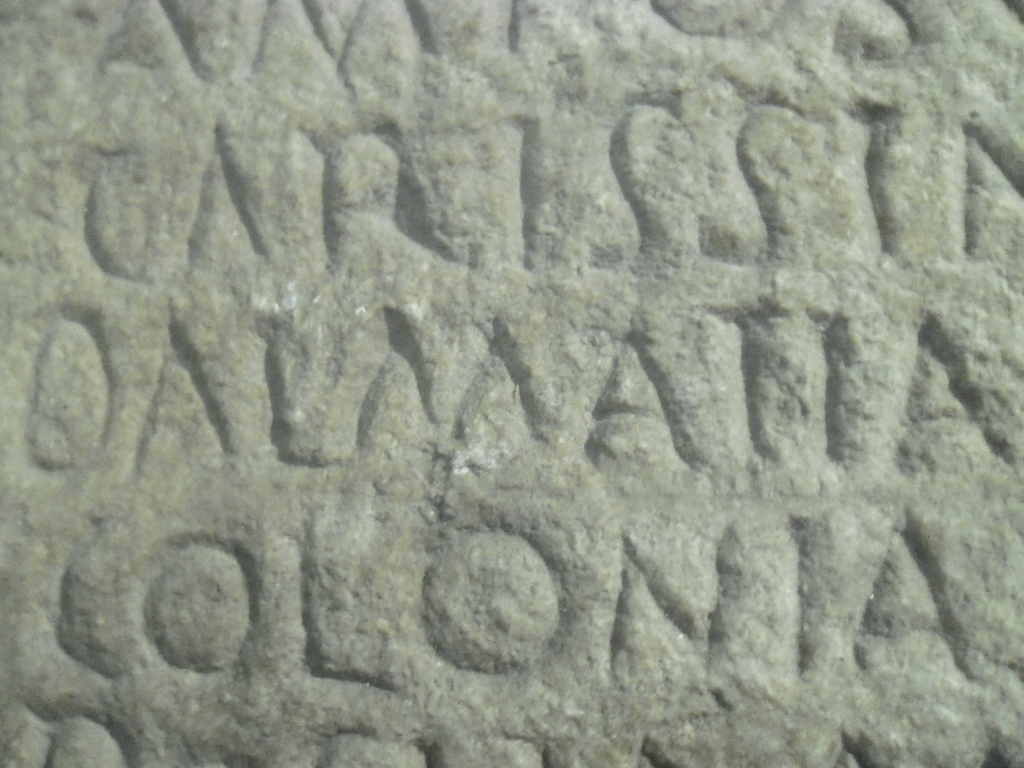

The earliest mention of Dalmatia as a province came after its establishment as part of the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Roman Republic, Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings aro ...

. Dalmatia was ravaged by barbaric tribes in the beginning of the 4th century. Slavs settled in the area in the 6th century, the White Croats

White Croats ( hr, Bijeli Hrvati; pl, Biali Chorwaci; cz, Bílí Chorvati; uk, Білі хорвати, Bili khorvaty), or simply known as Croats, were a group of Early Slavic tribes who lived among other West and East Slavic tribes in the ar ...

settled Dalmatia the following century. In 1527 the Kingdom of Croatia Kingdom of Croatia may refer to:

* Kingdom of Croatia (925–1102), an independent medieval kingdom

* Croatia in personal union with Hungary (1102–1526), a kingdom in personal union with the Kingdom of Hungary

* Kingdom of Croatia (Habsburg) (152 ...

became a Habsburg

The House of Habsburg (), alternatively spelled Hapsburg in Englishgerman: Haus Habsburg, ; es, Casa de Habsburgo; hu, Habsburg család, it, Casa di Asburgo, nl, Huis van Habsburg, pl, dom Habsburgów, pt, Casa de Habsburgo, la, Domus Hab ...

crown land, and in 1812 the Kingdom of Dalmatia

The Kingdom of Dalmatia ( hr, Kraljevina Dalmacija; german: Königreich Dalmatien; it, Regno di Dalmazia) was a crown land of the Austrian Empire (1815–1867) and the Cisleithanian half of Austria-Hungary (1867–1918). It encompassed the entire ...

was formed. In 1918, Dalmatia was a part of the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs

The State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs ( sh, Država Slovenaca, Hrvata i Srba / ; sl, Država Slovencev, Hrvatov in Srbov) was a political entity that was constituted in October 1918, at the end of World War I, by Slovenes, Croats and Serbs ( ...

, then the Kingdom of Yugoslavia

The Kingdom of Yugoslavia ( sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Kraljevina Jugoslavija, Краљевина Југославија; sl, Kraljevina Jugoslavija) was a state in Southeast and Central Europe that existed from 1918 until 1941. From 191 ...

. After World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; hr, Dalmacija ; it, Dalmazia; see names in other languages) is one of the four historical regions of Croatia, alongside Croatia proper, Slavonia, and Istria. Dalmatia is a narrow belt of the east shore of the Adriatic Sea, str ...

became part of Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia

The Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, commonly referred to as SFR Yugoslavia or simply as Yugoslavia, was a country in Central and Southeast Europe. It emerged in 1945, following World War II, and lasted until 1992, with the breakup of Yu ...

in SR Croatia

The Socialist Republic of Croatia ( sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Socijalistička Republika Hrvatska, Социјалистичка Република Хрватска), or SR Croatia, was a constituent republic and federated state of the Sociali ...

.

Classical antiquity

The history of Dalmatia began in 180 BC when the tribe from which the country derives its name declared itself independent ofGentius

Gentius ( grc, Γένθιος, "Génthios"; 181168 BC) was an Illyrian king who belonged to the Labeatan dynasty. He ruled in 181–168 BC, being the last attested Illyrian king. He was the son of Pleuratus III, a king who kept positive relati ...

, the Illyrian king, and established a republic. Its capital was Delminium

Delminium was an Illyrian city and the capital of the Dalmatia which was located somewhere near today's Tomislavgrad, Bosnia and Herzegovina, under which name it also was the seat of a Latin bishopric (also known as ''Delminium'').

Name

The to ...

(current name Tomislavgrad); its territory stretched northwards from the river Neretva

The Neretva ( sr-cyrl, Неретва, ), also known as Narenta, is one of the largest rivers of the eastern part of the Adriatic basin. Four HE power-plants with large dams (higher than 150,5 metres) provide flood protection, power and water s ...

to the river Cetina, and later to the Krka, where it met the confines of Liburnia.

Roman domination

The Roman Empire began its occupation of Illyria in the year 168 BC, forming theRoman province

The Roman provinces (Latin: ''provincia'', pl. ''provinciae'') were the administrative regions of Ancient Rome outside Roman Italy that were controlled by the Romans under the Roman Republic and later the Roman Empire. Each province was rule ...

of Illyricum. In 156 BC the Dalmatians were for the first time attacked by a Roman army and compelled to pay tribute. In AD 10, during the reign of Augustus

Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian, was the first Roman emperor; he reigned from 27 BC until his death in AD 14. He is known for being the founder of the Roman Pr ...

, Illyricum was split into Pannonia

Pannonia (, ) was a province of the Roman Empire bounded on the north and east by the Danube, coterminous westward with Noricum and upper Italy, and southward with Dalmatia and upper Moesia. Pannonia was located in the territory that is now west ...

in the north and Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; hr, Dalmacija ; it, Dalmazia; see names in other languages) is one of the four historical regions of Croatia, alongside Croatia proper, Slavonia, and Istria. Dalmatia is a narrow belt of the east shore of the Adriatic Sea, str ...

in the south, after the last of many uprisings known collectively as the Great Illyrian Revolt

The (Latin for 'War of the Batos') was a military conflict fought in the Roman province of Illyricum in the 1st century AD, in which an alliance of native peoples of the two regions of Illyricum, Dalmatia and Pannonia, revolted against the Roma ...

had been crushed by Tiberius

Tiberius Julius Caesar Augustus (; 16 November 42 BC – 16 March AD 37) was the second Roman emperor. He reigned from AD 14 until 37, succeeding his stepfather, the first Roman emperor Augustus. Tiberius was born in Rome in 42 BC. His father ...

in AD 9. Following the end of the revolt, there was general acceptance of the Latin civilisation throughout Illyria

In classical antiquity, Illyria (; grc, Ἰλλυρία, ''Illyría'' or , ''Illyrís''; la, Illyria, ''Illyricum'') was a region in the western part of the Balkan Peninsula inhabited by numerous tribes of people collectively known as the Illyr ...

and submission to the Roman Empire.

Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; hr, Dalmacija ; it, Dalmazia; see names in other languages) is one of the four historical regions of Croatia, alongside Croatia proper, Slavonia, and Istria. Dalmatia is a narrow belt of the east shore of the Adriatic Sea, str ...

spread inland to cover all of the Dinaric Alps

The Dinaric Alps (), also Dinarides, are a mountain range in Southern and Southcentral Europe, separating the continental Balkan Peninsula from the Adriatic Sea. They stretch from Italy in the northwest through Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herz ...

and most of the eastern Adriatic coast. Its capital was the city of Salona

Salona ( grc, Σάλωνα) was an ancient city and the capital of the Roman province of Dalmatia. Salona is located in the modern town of Solin, next to Split, in Croatia.

Salona was founded in the 3rd century BC and was mostly destroyed in ...

(Solin). Emperor Diocletian

Diocletian (; la, Gaius Aurelius Valerius Diocletianus, grc, Διοκλητιανός, Diokletianós; c. 242/245 – 311/312), nicknamed ''Iovius'', was Roman emperor from 284 until his abdication in 305. He was born Gaius Valerius Diocles ...

made Dalmatia famous by building a palace for himself a few kilometers south of Salona

Salona ( grc, Σάλωνα) was an ancient city and the capital of the Roman province of Dalmatia. Salona is located in the modern town of Solin, next to Split, in Croatia.

Salona was founded in the 3rd century BC and was mostly destroyed in ...

, in Aspalathos/ Spalatum. Other Dalmatian cities at the time were: Tarsatica

Trsat ( it, Tersatto, la, Tarsatica) is part of the city of Rijeka, Croatia, with a historic castle or fortress in a strategic location and several historic churches, in one of which the Croatian noble Prince Vuk Krsto Frankopan is buried. Trs ...

, Senia, Vegium, Aenona, Iader, Scardona, Tragurium

Trogir (; historically known as Traù (from Dalmatian, Venetian and Italian: ); la, Tragurium; Ancient Greek: Τραγύριον, ''Tragyrion'' or Τραγούριον, ''Tragourion'') is a historic town and harbour on the Adriatic coast in ...

, Aequum

Aequum was a Roman colony located near modern-day Čitluk, a village near Sinj, Croatia.

Location

The valley of the middle part of the Cetina river and its surrounding area, known as the District of Cetina, represent the backbone of the entire ...

, Oneum, Issa, Pharus, Bona, Corcyra Nigra, Narona

Narona ( grc, Ναρῶνα) was an Ancient Greek trading post on the Illyrian coast and later Roman city and bishopric, located in the Neretva valley in present-day Croatia, which remains a Latin Catholic titular see.

History

It was founded ...

, Epidaurus

Epidaurus ( gr, Ἐπίδαυρος) was a small city ('' polis'') in ancient Greece, on the Argolid Peninsula at the Saronic Gulf. Two modern towns bear the name Epidavros: '' Palaia Epidavros'' and '' Nea Epidavros''. Since 2010 they belong t ...

, Rhizinium Rhizon ( grc, Ῥίζων; la, Risinium) was a city in classical and Roman antiquity. Rhizon is the oldest settlement in the Bay of Kotor and the modern town of Risan (modern Montenegro) stands near the old city. Originally it was an Illyrian sett ...

, Acruvium

Kotor (Montenegrin Cyrillic: Котор, ), historically known as Cattaro (from Italian: ), is a coastal town in Montenegro. It is located in a secluded part of the Bay of Kotor. The city has a population of 13,510 and is the administrative c ...

, Olcinium

Ulcinj ( cyrl, Улцињ, ; ) is a town on the southern coast of Montenegro and the capital of Ulcinj Municipality. It has an urban population of 10,707 (2011), the majority being Albanians.

As one of the oldest settlements in the Adriatic coast ...

, Scodra, Epidamnus/ Dyrrachium.

The Roman Emperor Diocletian

Diocletian (; la, Gaius Aurelius Valerius Diocletianus, grc, Διοκλητιανός, Diokletianós; c. 242/245 – 311/312), nicknamed ''Iovius'', was Roman emperor from 284 until his abdication in 305. He was born Gaius Valerius Diocles ...

(ruled AD 284 to 305) reformed the government in the late Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Roman Republic, Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings aro ...

and established the Tetrarchy

The Tetrarchy was the system instituted by Roman emperor Diocletian in 293 AD to govern the ancient Roman Empire by dividing it between two emperors, the ''augusti'', and their juniors colleagues and designated successors, the '' caesares'' ...

. This new system for the first time divided rule of the empire into the Western and Eastern courts, each headed by a person with the title of Augustus

Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian, was the first Roman emperor; he reigned from 27 BC until his death in AD 14. He is known for being the founder of the Roman Pr ...

. Each of the two Augusti also had an appointed successor, a Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, an ...

, who administered about half the district belonging to his own Augustus (and was subordinate to him). In Diocletian's division, Dalmatia fell under the rule of the Eastern Court, headed by Diocletian, but was administered by his Caesar and appointed successor Galerius

Gaius Galerius Valerius Maximianus (; 258 – May 311) was Roman emperor from 305 to 311. During his reign he campaigned, aided by Diocletian, against the Sasanian Empire, sacking their capital Ctesiphon in 299. He also campaigned across th ...

, who had his seat in the city of Sirmium

Sirmium was a city in the Roman province of Pannonia, located on the Sava river, on the site of modern Sremska Mitrovica in the Vojvodina autonomous provice of Serbia. First mentioned in the 4th century BC and originally inhabited by Illyria ...

. In AD 395, the Emperor Theodosius I

Theodosius I ( grc-gre, Θεοδόσιος ; 11 January 347 – 17 January 395), also called Theodosius the Great, was Roman emperor from 379 to 395. During his reign, he succeeded in a crucial war against the Goths, as well as in two ...

permanently divided Imperial rule by granting his two sons the position of Augusti separately in the West and the East. This time, however, Spalatum and Dalmatia fell under the Western Court of Honorius, not the Eastern Court.

In 468 Flavius Julius Nepos became the ruler of the Province of Dalmatia. Four years later, in the spring of 472, the Western Emperor Anthemius was murdered by his Germanic general Ricimer; the appointment of his successor legally fell to Emperor

In 468 Flavius Julius Nepos became the ruler of the Province of Dalmatia. Four years later, in the spring of 472, the Western Emperor Anthemius was murdered by his Germanic general Ricimer; the appointment of his successor legally fell to Emperor Leo I the Thracian

Leo I (; 401 – 18 January 474), also known as "the Thracian" ( la, Thrax; grc-gre, ο Θραξ),; grc-gre, Μακέλλης), referencing the murder of Aspar and his son. was Eastern Roman emperor from 457 to 474. He was a native of Dacia ...

of the Eastern Court. Leo however tarried in his appointment. Ricimer, along with his nephew Gundobad

Gundobad ( la, Flavius Gundobadus; french: Gondebaud, Gondovald; 452 – 516 AD) was King of the Burgundians (473 – 516), succeeding his father Gundioc of Burgundy. Previous to this, he had been a patrician of the moribund Western Roman Em ...

, appointed Olybrius and then Glycerius as their puppet emperors in the West. This was not recognized by Leo I and the Eastern Court, who considered them usurpers. In 473 Leo appointed Flavius Julius Nepos, the ruler of Dalmatia, as the legal Western Emperor. In June 474, Nepos sailed across the Adriatic, entered Ravenna

Ravenna ( , , also ; rgn, Ravèna) is the capital city of the Province of Ravenna, in the Emilia-Romagna region of Northern Italy. It was the capital city of the Western Roman Empire from 408 until its collapse in 476. It then served as the c ...

(the seat of the Western court), forced Glycerius to abdicate, and secured the throne. However, next year his ''Magister militum

(Latin for "master of soldiers", plural ) was a top-level military command used in the later Roman Empire, dating from the reign of Constantine the Great. The term referred to the senior military officer (equivalent to a war theatre commander, ...

'' Orestes

In Greek mythology, Orestes or Orestis (; grc-gre, Ὀρέστης ) was the son of Clytemnestra and Agamemnon, and the brother of Electra. He is the subject of several Ancient Greek plays and of various myths connected with his madness an ...

forced Nepos to flee back to Salona (on 28 August 475). Romulus Augustulus

Romulus Augustus ( 465 – after 511), nicknamed Augustulus, was Roman emperor of the West from 31 October 475 until 4 September 476. Romulus was placed on the imperial throne by his father, the ''magister militum'' Orestes, and, at that time ...

, the son of Orestes, was proclaimed Emperor within a few months, but was deposed the following year after the execution of his father. Odoacer

Odoacer ( ; – 15 March 493 AD), also spelled Odovacer or Odovacar, was a soldier and statesman of barbarian background, who deposed the child emperor Romulus Augustulus and became Rex/Dux (476–493). Odoacer's overthrow of Romulus August ...

, the general who deposed Romulus Augustulus, did not appoint a puppet emperor, but instead, for his part, abolished the Western court altogether. Julius Nepos, however, continued to rule in Dalmatia until 480 as the sole legal Emperor of the West (Dalmatia still being ''de jure'' a part of the Western court's administration).

After the death of Julius Nepos in AD 480, the Empire was formally reunited under the rule of a single throne, under Emperor Zeno

Zeno ( grc, Ζήνων) may refer to:

People

* Zeno (name), including a list of people and characters with the name

Philosophers

* Zeno of Elea (), philosopher, follower of Parmenides, known for his paradoxes

* Zeno of Citium (333 – 264 BC), ...

in Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

. Dalmatia continued as a Roman possession, ruled from Constantinople, and was thus part of the state referred to in historiography as the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

(although historically it continued to be known as the "Roman Empire" throughout its existence). The collapse of the Western Empire left this region subject to Gothic

Gothic or Gothics may refer to:

People and languages

*Goths or Gothic people, the ethnonym of a group of East Germanic tribes

**Gothic language, an extinct East Germanic language spoken by the Goths

**Crimean Gothic, the Gothic language spoken b ...

rulers, Odoacer

Odoacer ( ; – 15 March 493 AD), also spelled Odovacer or Odovacar, was a soldier and statesman of barbarian background, who deposed the child emperor Romulus Augustulus and became Rex/Dux (476–493). Odoacer's overthrow of Romulus August ...

and Theodoric the Great

Theodoric (or Theoderic) the Great (454 – 30 August 526), also called Theodoric the Amal ( got, , *Þiudareiks; Greek: , romanized: ; Latin: ), was king of the Ostrogoths (471–526), and ruler of the independent Ostrogothic Kingdom of Italy ...

, from 480 to 535, when it was added by Justinian I

Justinian I (; la, Iustinianus, ; grc-gre, Ἰουστινιανός ; 48214 November 565), also known as Justinian the Great, was the Byzantine emperor from 527 to 565.

His reign is marked by the ambitious but only partly realized '' renov ...

to the Eastern (Byzantine) Empire.

Around AD 639 the hinterland of Dalmatia fell after the invasion of Avars and Slavs

Slavs are the largest European ethnolinguistic group. They speak the various Slavic languages, belonging to the larger Balto-Slavic branch of the Indo-European languages. Slavs are geographically distributed throughout northern Eurasia, main ...

, and the city of Salona was sacked. The majority of the displaced citizens fled by sea to the nearby Adriatic islands. Following the return of Byzantine rule to the area, the Roman population returned to the mainland under the leadership of the nobleman known as Severus the Great. They chose to inhabit Diocletian's Palace

Diocletian's Palace ( hr, Dioklecijanova palača, ) is an ancient palace built for the Roman emperor Diocletian at the turn of the fourth century AD, which today forms about half the old town of Split, Croatia. While it is referred to as a "pala ...

in Spalatum, because of its strong fortifications and defendable setting. The palace had been long-deserted by this time, and the interior was converted into a city by the Salona refugees, rendering Spalatum the effective capital of the Province.

Throughout the following centuries, effectively until the early 13th century and the Fourth Crusade

The Fourth Crusade (1202–1204) was a Latin Christian armed expedition called by Pope Innocent III. The stated intent of the expedition was to recapture the Muslim-controlled city of Jerusalem, by first defeating the powerful Egyptian Ayyubid S ...

, Spalatum would remain a possession of the Byzantine emperors

This is a list of the Byzantine emperors from the foundation of Constantinople in 330 AD, which marks the conventional start of the Eastern Roman Empire, to its fall to the Ottoman Empire in 1453 AD. Only the emperors who were recognized as ...

, even though its hinterland would seldom be under Byzantine control, and ''de facto'' suzerainty

Suzerainty () is the rights and obligations of a person, state or other polity who controls the foreign policy and relations of a tributary state, while allowing the tributary state to have internal autonomy. While the subordinate party is ca ...

over the city would often be exercised by Croatian, Venetian

Venetian often means from or related to:

* Venice, a city in Italy

* Veneto, a region of Italy

* Republic of Venice (697–1797), a historical nation in that area

Venetian and the like may also refer to:

* Venetian language, a Romance language s ...

, or Hungarian rulers. Overall, the city enjoyed significant autonomy during this time, due to the periodic weakness and/or preoccupation of the Byzantine Imperial administration.

Middle Ages

Following the great Slavic migration intoIllyria

In classical antiquity, Illyria (; grc, Ἰλλυρία, ''Illyría'' or , ''Illyrís''; la, Illyria, ''Illyricum'') was a region in the western part of the Balkan Peninsula inhabited by numerous tribes of people collectively known as the Illyr ...

in the first half of the 6th century, Dalmatia became distinctly divided between two different communities:

* The hinterland populated by Slavic tribes

This is a list of Slavic peoples and Slavic tribes reported in Late Antiquity and in the Middle Ages, that is, before the year AD 1500.

Ancestors

*Proto-Indo-Europeans (Proto-Indo-European speakers)

** Proto-Balto-Slavs (common ancestors of Ba ...

- which were roughly Croats

The Croats (; hr, Hrvati ) are a South Slavic ethnic group who share a common Croatian ancestry, culture, history and language. They are also a recognized minority in a number of neighboring countries, namely Austria, the Czech Republic ...

. There were also the Romanized Illyrian natives, and Celts in the north.

* The Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

enclaves populated by the native Romance-speaking descendants of Romans and Illyrians (speaking Dalmatian), who lived safely in Ragusa, Iadera, Tragurium

Trogir (; historically known as Traù (from Dalmatian, Venetian and Italian: ); la, Tragurium; Ancient Greek: Τραγύριον, ''Tragyrion'' or Τραγούριον, ''Tragourion'') is a historic town and harbour on the Adriatic coast in ...

, Spalatum and some other coastal towns, like Cattaro (Kotor).

Croatian Dalmatia

The Slavs that migrated soon formed their own realm, the Principality of Littoral Croatia, ruled by Slavic princes. A separate tribe calledGuduscani

The Guduscani or Goduscani ( hr, Guduščani, Gačani) were a tribe whose location and origin on the territory of early medieval Croatia remains a matter of dispute. According to one hypothesis they were located around present-day Gacka (Lika), be ...

lived in the northwestern part of Roman Dalmatia. Borna of Croatia (803–821) was one of the earliest recorded rulers of the Principality of Littoral Croatia. In 806 the Principality of Dalmatia was temporarily added to the Frankish Empire

Francia, also called the Kingdom of the Franks ( la, Regnum Francorum), Frankish Kingdom, Frankland or Frankish Empire ( la, Imperium Francorum), was the largest post-Roman barbarian kingdom in Western Europe. It was ruled by the Franks dur ...

, but the cities were restored to Byzantium

Byzantium () or Byzantion ( grc, Βυζάντιον) was an ancient Greek city in classical antiquity that became known as Constantinople in late antiquity and Istanbul today. The Greek name ''Byzantion'' and its Latinization ''Byzantium' ...

by the Treaty of Aachen in 812. The treaty had also slightly expanded the Principality of Dalmatia eastwards.

The establishment of cordial relations between the cities and the Croatia

, image_flag = Flag of Croatia.svg

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Croatia.svg

, anthem = " Lijepa naša domovino"("Our Beautiful Homeland")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capi ...

n dukedom began with the reign of Duke

Duke is a male title either of a monarch ruling over a duchy, or of a member of royalty, or nobility. As rulers, dukes are ranked below emperors, kings, grand princes, grand dukes, and sovereign princes. As royalty or nobility, they are r ...

Mislav (835), who signed an official peace treaty with Pietro

Pietro is an Italian masculine given name. Notable people with the name include:

People

* Pietro I Candiano (c. 842–887), briefly the 16th Doge of Venice

* Pietro Tribuno (died 912), 17th Doge of Venice, from 887 to his death

* Pietro II ...

, doge of Venice

The Doge of Venice ( ; vec, Doxe de Venexia ; it, Doge di Venezia ; all derived from Latin ', "military leader"), sometimes translated as Duke (compare the Italian '), was the chief magistrate and leader of the Republic of Venice between 726 ...

in 840 and who also started giving land donations to the churches from the cities.

Dalmatia's Croatian Duke Trpimir (ruled 845–864), founder of the House of Trpimir, greatly expanded the new Duchy to include territories all the way to the river of Drina

The Drina ( sr-Cyrl, Дрина, ) is a long Balkans river, which forms a large portion of the border between Bosnia and Herzegovina and Serbia. It is the longest tributary of the Sava River and the longest karst river in the Dinaric Alps whi ...

, thereby covering the entirety of Bosnia

Bosnia and Herzegovina ( sh, / , ), abbreviated BiH () or B&H, sometimes called Bosnia–Herzegovina and Pars pro toto#Geography, often known informally as Bosnia, is a country at the crossroads of Southern Europe, south and southeast Euro ...

in his wars against the Bulgar Khans and their Serbian subjects.

The Saracens

upright 1.5, Late 15th-century German woodcut depicting Saracens

Saracen ( ) was a term used in the early centuries, both in Greek and Latin writings, to refer to the people who lived in and near what was designated by the Romans as Arabia ...

had raided the southernmost cities in 840 and 842, but this threat was eliminated by a common Frankish-Byzantine campaign of 871.

Duke of Croats Tomislav

Tomislav (, ) is a masculine given name of Slavic origin, that is widespread amongst the South Slavs.

The meaning of the name ''Tomislav'' is thought to have derived from the Old Slavonic verb "'' tomiti''" or "'' tomit" meaning to "''languish ...

had created the Kingdom of Croatia Kingdom of Croatia may refer to:

* Kingdom of Croatia (925–1102), an independent medieval kingdom

* Croatia in personal union with Hungary (1102–1526), a kingdom in personal union with the Kingdom of Hungary

* Kingdom of Croatia (Habsburg) (152 ...

in 924 or 925, and was crowned in Tomislavgrad after defending and annexing the Principality of Pannonia. His powerful realm extended influence further southwards to Duklja

Duklja ( sh-Cyrl, Дукља; el, Διόκλεια, Diokleia; la, Dioclea) was a medieval South Slavic state which roughly encompassed the territories of modern-day southeastern Montenegro, from the Bay of Kotor in the west to the Bojana Riv ...

.

As the Littoral Croatian Duchy became a Kingdom after 925, its capitals were in Dalmatia: Biaći, Nin, Split

Split(s) or The Split may refer to:

Places

* Split, Croatia, the largest coastal city in Croatia

* Split Island, Canada, an island in the Hudson Bay

* Split Island, Falkland Islands

* Split Island, Fiji, better known as Hạfliua

Arts, entertai ...

, Knin

Knin (, sr, link=no, Книн, it, link=no, Tenin) is a city in the Šibenik-Knin County of Croatia, located in the Dalmatian hinterland near the source of the river Krka, an important traffic junction on the rail and road routes between Zagr ...

, Solin and elsewhere. Also, the Croatia

, image_flag = Flag of Croatia.svg

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Croatia.svg

, anthem = " Lijepa naša domovino"("Our Beautiful Homeland")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capi ...

n noble tribes, who had a right to choose Croatian duke (later the king), were from Dalmatia: Karinjani and Lapčani, Polečići, Tugomirići, Kukari, Snačići, Gusići, Šubići (from which later developed very powerful noble family Zrinski

Zrinski () was a Croatian- Hungarian noble family, a cadet branch of the Croatian noble tribe of Šubić, influential during the period in history marked by the Ottoman wars in Europe in the Kingdom of Croatia's union with the Kingdom of Hun ...

), Mogorovići, Lačničići, Jamometići and Kačić. Within the borders of ancient Roman Dalmatia, the Croatian nobles of Krk, or Krčki (from which later developed very powerful noble family Frankopan

The House of Frankopan ( hr, Frankopani, Frankapani, it, Frangipani, hu, Frangepán, la, Frangepanus, Francopanus), was a Croatian noble family, whose members were among the great landowner magnates and high officers of the Kingdom of Croat ...

) were from Dalmatia as well.

Meanwhile, the Croatian kings exacted tribute from the Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

cities, Tragurium

Trogir (; historically known as Traù (from Dalmatian, Venetian and Italian: ); la, Tragurium; Ancient Greek: Τραγύριον, ''Tragyrion'' or Τραγούριον, ''Tragourion'') is a historic town and harbour on the Adriatic coast in ...

, Iadera and others, and consolidated their own power in the purely Croatian-settled towns such as Nin, Biograd and Šibenik

Šibenik () is a historic city in Croatia, located in central Dalmatia, where the river Krka flows into the Adriatic Sea. Šibenik is a political, educational, transport, industrial and tourist center of Šibenik-Knin County, and is also the ...

. The city of Šibenik was founded by Croatian kings. They also ascertained control over the bordering southern duchies. Rulers of the medieval Croatian state who had control over the Dalmatian littoral and the cities were the dukes Trpimir, Domagoj, Branimir, and the kings Tomislav

Tomislav (, ) is a masculine given name of Slavic origin, that is widespread amongst the South Slavs.

The meaning of the name ''Tomislav'' is thought to have derived from the Old Slavonic verb "'' tomiti''" or "'' tomit" meaning to "''languish ...

, Trpimir II, Krešimir I, Stjepan Držislav, Petar Krešimir IV and Dmitar Zvonimir.

Southern Dalmatia

The area of Southern Dalmatia was divided among four small principalities called Pagania,

The area of Southern Dalmatia was divided among four small principalities called Pagania, Zahumlje

Zachlumia or Zachumlia ( sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Zahumlje, Захумље, ), also Hum, was a medieval principality located in the modern-day regions of Herzegovina and southern Dalmatia (today parts of Bosnia and Herzegovina and Croatia ...

, Travunia and Duklja

Duklja ( sh-Cyrl, Дукља; el, Διόκλεια, Diokleia; la, Dioclea) was a medieval South Slavic state which roughly encompassed the territories of modern-day southeastern Montenegro, from the Bay of Kotor in the west to the Bojana Riv ...

. Pagania was a minor duchy between Cetina and Neretva

The Neretva ( sr-cyrl, Неретва, ), also known as Narenta, is one of the largest rivers of the eastern part of the Adriatic basin. Four HE power-plants with large dams (higher than 150,5 metres) provide flood protection, power and water s ...

. The territories of Zahumlje and Travunia spread much further inland than the current borders of Dalmatia. Duklja (the Roman Doclea) began south of Dubrovnik and spread down to the Skadar Lake.

Pagania

Pagania was given its name because of the paganism of its inhabitants, when neighbouring tribes were Christian. Thepirate

Piracy is an act of robbery or criminal violence by ship or boat-borne attackers upon another ship or a coastal area, typically with the goal of stealing cargo and other valuable goods. Those who conduct acts of piracy are called pirates, v ...

-like people of Pagania/Narenta (named after river Narenta

The Neretva ( sr-cyrl, Неретва, ), also known as Narenta, is one of the largest rivers of the eastern part of the Adriatic basin. Four HE power-plants with large dams (higher than 150,5 metres) provide flood protection, power and water s ...

) expressed their buccaneering capabilities by pirateering the Venetian-controlled Adriatic between 827 and 828, while the Venetian fleet was further afield, in the Sicilian waters. As soon as the fleet of the Venetian Republic

The Republic of Venice ( vec, Repùblega de Venèsia) or Venetian Republic ( vec, Repùblega Vèneta, links=no), traditionally known as La Serenissima ( en, Most Serene Republic of Venice, italics=yes; vec, Serenìsima Repùblega de Venèsia ...

returned, the Neretvians fell back; when the Venetians left, the Neretvians would immediately embark on new raids. In 834 and 835, they caught and killed several Venetian traders returning from Benevent

Benevento (, , ; la, Beneventum) is a city and ''comune'' of Campania, Italy, capital of the province of Benevento, northeast of Naples. It is situated on a hill above sea level at the confluence of the Calore Irpino (or Beneventano) and the S ...

. To punish the Neretvians, the Venetian Doge

A doge ( , ; plural dogi or doges) was an elected lord and head of state in several Italian city-states, notably Venice and Genoa, during the medieval and renaissance periods. Such states are referred to as " crowned republics".

Etymology

The ...

launched a military expedition against them in 839. The war continued with the inclusion of the Dalmatian Croats, but a truce was quickly signed, although, only with the Dalmatian Croats and some of the Pagan tribes. In 840, the Venetians launched an expedition against the Neretvian Prince ''Ljudislav'', but without success. In 846, a new operation was launched that raided the Slavic land of Pagania, destroying one of her most important cities (''Kaorle). '' This did not end the Neretvian resistance, as they continued to raid and steal from the Venetian occupators.

It was not until 998 that the Venetians gained the upper hand. Doge Peter II Orseolo finally crushed the Neretvians and assumed the title duke of the Dalmatians (''Dux Dalmatianorum''), though without conflicting Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

suzerainty. In 1050, the Neretvians where part of Kingdom of Croatia Kingdom of Croatia may refer to:

* Kingdom of Croatia (925–1102), an independent medieval kingdom

* Croatia in personal union with Hungary (1102–1526), a kingdom in personal union with the Kingdom of Hungary

* Kingdom of Croatia (Habsburg) (152 ...

under King Stjepan I.

Zahumlje

Zahumlje got its name from the mountain of '' Hum'' near Bona, where the river of Buna flowed. It included two old cities: ''Bona'' and ''Hum''. Zahumlje included parts of modern-day regions of Herzegovina and southern Dalmatia. Zahumlje's first known ruler was Michael of Zahumlje, he was mentioned together withTomislav of Croatia

Tomislav (, la, Tamisclaus) was the first king of Croatia. He became Duke of Croatia and was crowned king in 925, reigning until 928. During Tomislav's rule, Croatia forged an alliance with the Byzantine Empire against Bulgaria. Croatia's strug ...

in Pope John X

Pope John X ( la, Ioannes X; died 28 May 928) was the bishop of Rome and nominal ruler of the Papal States from March 914 to his death. A candidate of the counts of Tusculum, he attempted to unify Italy under the leadership of Berengar of Friuli, ...

's letter of 925. In that same year, he participated in the first church councils in Split

Split(s) or The Split may refer to:

Places

* Split, Croatia, the largest coastal city in Croatia

* Split Island, Canada, an island in the Hudson Bay

* Split Island, Falkland Islands

* Split Island, Fiji, better known as Hạfliua

Arts, entertai ...

. Michael, with grand titles of the Byzantine court as ''anthypatos ''Anthypatos'' ( gr, ἀνθύπατος) is the translation in Greek of the Latin '' proconsul''. In the Greek-speaking East, it was used to denote this office in Roman and early Byzantine times, surviving as an administrative office until the 9th ...

'' and patrician (''patrikios

The patricians (from la, patricius, Greek: πατρίκιος) were originally a group of ruling class families in ancient Rome. The distinction was highly significant in the Roman Kingdom, and the early Republic, but its relevance waned aft ...

''), remained ruler of Zahumlje through the 940s, while maintaining good relations with the Pope

The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

.

Travunia

Travunia was initially a town, present-day Trebinje, that was promoted to a fief during the rule ofVlastimir of Serbia

Vlastimir ( sr-cyrl, Властимир, ; c. 805 – 851) was the Serbian prince from c. 830 until c. 851. Little is known of his reign. He held Serbia during the growing threat posed by the neighbouring, hitherto peaceful, First Bulgarian Empi ...

, when he married his daughter to nobleman Krajina Belojević

Krajina Belojević ( sr, Крајина, gr, Κράινα) was the Serbian ''župan'' of Travunia, an administrative unit of the Principality of Serbia, in the 9th century. In 847/848, not long after the three-year Bulgarian–Serbian War (839� ...

. It was ruled by this family until the next century, when Boleslav Petrović, the son of Predimir ruled Serbia. At this time it had the following Župania: ''Libomir, Vetanica, Rudina, Crusceviza, Vrmo, Rissena, Draceviza, Canali, Gernoviza''. It is annexed during the rule of Pavle Branović

Pavle Branovic ( sr, Павле Брановић, gr, Παῦλος; 870–921) was the Prince of the Serbs from 917 to 921. He was put on the throne by the Bulgarian Tsar Symeon I of Bulgaria, who had imprisoned the previous prince, Petar af ...

.

Dragomir Hvalimirović restores the title of Travunia, but is murdered in the 1010s, and the maritime lands are annexed by the Byzantines, and then Serbia. Grdeša

Grdeša ( sr-cyr, Грдеша, lat, Gerdessa, Gurdeses; 1150–51) or Grd, was the ''župan'' (count) of Travunija, mentioned in 1150–51 as serving Grand Prince Uroš II of Serbia.

It is believed that Grdeša was born around 1120. In 1150 h ...

, of unknown genealogy, is given the rule of Travunia under Uroš II Prvoslav __NOTOC__

Uroš ( sr-Cyrl, Урош) is a South Slavic given or last name primarily spread amongst Serbs, and Slovenians (mostly of Serbian descent). This noun has been interpreted as "lords", because it usually appears in conjunction with ''velmõ ...

. It is part of Serbia until 1377, when Bosnian Ban Tvrtko takes the area.

Republic of Venice and the Kingdom of Hungary

As the Dalmatian city states gradually lost all protection by Byzantium, being unable to unite in a defensive league hindered by their internal dissensions, they had to turn to either

As the Dalmatian city states gradually lost all protection by Byzantium, being unable to unite in a defensive league hindered by their internal dissensions, they had to turn to either Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 ...

or Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Cr ...

for support. Each of the two political factions had support within the Dalmatian city states, based mostly on economic reasons.

The Venetians, to whom the Dalmatians were already bound by language and culture, could afford to concede liberal terms as its main goal was to prevent the development of any dangerous political or commercial competitor on the eastern Adriatic.

The seafaring community in Dalmatia looked to Venice as mistress of the Adriatic. In return for protection, the cities often furnished a contingent to the army or navy of their suzerain, and sometimes paid tribute either in money or in kind. Arbe (Rab), for example, annually paid ten pounds of silk or five pounds of gold to Venice.

Hungary, on the other hand, defeated the last Croat king in 1097 and laid claim on all lands of the Croatian noblemen since the treaty 1102. King Coloman proceeded to conquer Dalmatia in 1102–1105.

The farmers and the merchants who traded in the interior favoured Hungary as their most powerful neighbour on land that affirmed their municipal privileges.

Subject to the royal assent they might elect their own chief magistrate, bishop and judges. Their Roman law remained valid. They were even permitted to conclude separate alliances. No alien, not even a Hungarian, could reside in a city where he was unwelcome; and the man who disliked Hungarian dominion could emigrate with all his household and property. In lieu of tribute, the revenue from customs was in some cases shared equally by the king, chief magistrate, bishop and municipality.

These rights and the analogous privileges granted by Venice were, however, too frequently infringed. Hungarian garrisons were being quartered on unwilling towns, while Venice interfered with trade, the appointment of bishops, or the tenure of communal domains. Consequently, the Dalmatians remained loyal only while it suited their interests, and insurrections frequently occurred. Even in Zara four outbreaks are recorded between 1180 and 1345, although Zadar was treated with special consideration by its Venetian masters, who regarded its possession as essential to their maritime ascendancy.

The once rival Romanic and Slavic population eventually started contributing to a common civilization, and Ragusa (Dubrovnik) was the primary example of this. By the 13th century, the councilmen from ragusan names were mixed, and in the 15th century the ragusan literature was even written in the Slavic language (from which Croatian is directly descended), and the city was often called by its Slavic name, Dubrovnik. Only in 1918 Ragusa was called officially "Dubrovnik", with the creation of Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia (; sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Jugoslavija, Југославија ; sl, Jugoslavija ; mk, Југославија ;; rup, Iugoslavia; hu, Jugoszlávia; rue, label= Pannonian Rusyn, Югославия, translit=Juhoslavij ...

.

The doubtful allegiance of the Dalmatians tended to protract the struggle between Venice and Hungary, which was further complicated by internal discord due largely to the spread of the Bogomil heresy, and by many outside influences.

The cities of Zara (Zadar), Spalato (Split), Trau (Trogir) and Ragusa (Dubrovnik) and the surrounding territories each changed hands several times between Venice, Hungary and the Byzantium during the 12th century.

In 1202, the armies of the Fourth Crusade

The Fourth Crusade (1202–1204) was a Latin Christian armed expedition called by Pope Innocent III. The stated intent of the expedition was to recapture the Muslim-controlled city of Jerusalem, by first defeating the powerful Egyptian Ayyubid S ...

rendered assistance to Venice by occupying Zadar for it. In 1204 the same army conquered Byzantium and finally eliminated the Eastern Empire from the list of contenders on Dalmatian territory.

The early 13th century was marked by a decline in external hostilities. The Dalmatian cities started accepting foreign sovereignty (mainly of the Republic of Venice

The Republic of Venice ( vec, Repùblega de Venèsia) or Venetian Republic ( vec, Repùblega Vèneta, links=no), traditionally known as La Serenissima ( en, Most Serene Republic of Venice, italics=yes; vec, Serenìsima Repùblega de Venèsia ...

) but eventually they reverted to their previous desire for independence. The Mongol

The Mongols ( mn, Монголчууд, , , ; ; russian: Монголы) are an East Asian ethnic group native to Mongolia, Inner Mongolia in China and the Buryatia Republic of the Russian Federation. The Mongols are the principal member ...

invasion severely impaired Hungary, so much that in 1241, the king Bela IV had to take refuge in Dalmatia (in the Klis fortress). The Mongols attacked the Dalmatian cities for the next few years but eventually withdrew.

The Croats were no longer regarded by the city folk as a hostile people, in fact the power of certain Croatian magnates, notably the counts Šubić of Bribir, was from time to time supreme in the northern districts (in the period between 1295 and 1328).

In 1346, Dalmatia was struck by the Black Death

The Black Death (also known as the Pestilence, the Great Mortality or the Plague) was a bubonic plague pandemic occurring in Western Eurasia and North Africa from 1346 to 1353. It is the most fatal pandemic recorded in human history, causi ...

. The economic situation was also poor, and the cities became more and more dependent on Venice.

Stephen Tvrtko, the founder of the Bosnia

Bosnia and Herzegovina ( sh, / , ), abbreviated BiH () or B&H, sometimes called Bosnia–Herzegovina and Pars pro toto#Geography, often known informally as Bosnia, is a country at the crossroads of Southern Europe, south and southeast Euro ...

n kingdom, was able in 1389 to annex the Adriatic littoral between Kotor

Kotor ( Montenegrin Cyrillic: Котор, ), historically known as Cattaro (from Italian: ), is a coastal town in Montenegro. It is located in a secluded part of the Bay of Kotor. The city has a population of 13,510 and is the administrative ...

(Cattaro) and Šibenik, and even claimed control over the northern coast up to Fiume (Rijeka

Rijeka ( , , ; also known as Fiume hu, Fiume, it, Fiume ; local Chakavian: ''Reka''; german: Sankt Veit am Flaum; sl, Reka) is the principal seaport and the third-largest city in Croatia (after Zagreb and Split). It is located in Prim ...

) except for the Venetian-ruled Zara (Zadar), and his own independent ally, Ragusa (Dubrovnik). This was only temporary, as the Hungarians and the Venetians continued their struggle over Dalmatia as soon as Tvrtko died in 1391.

An internal struggle of Hungary, between king Sigismund and the Neapolitan house of Anjou Anjou may refer to:

Geography and titles France

*County of Anjou, a historical county in France and predecessor of the Duchy of Anjou

**Count of Anjou, title of nobility

*Duchy of Anjou, a historical duchy and later a province of France

**Duke ...

, also reflected on Dalmatia: in the early 15th century, all Dalmatian cities welcomed the Neapolitan fleet except for Dubrovnik (Ragusa). The Bosnian duke Hrvoje controlled Dalmatia for the Angevins, but later switched loyalty to Sigismund.

Over the period of twenty years, this struggle weakened the Hungarian influence. In 1409, Ladislaus of Naples sold his ''rights'' over Dalmatia to Venice for 100,000 Ducat

The ducat () coin was used as a trade coin in Europe from the later Middle Ages from the 13th to 19th centuries. Its most familiar version, the gold ducat or sequin containing around of 98.6% fine gold, originated in Venice in 1284 and gained ...

s. Venice gradually took over most of Dalmatia by 1420. In 1437, Sigismund recognized Venetian rule over Dalmatia in return for 100,000 Ducats. The city of Omiš

Omiš (, Latin and it, Almissa) is a town and port in the Dalmatia region of Croatia, and is a municipality in the Split-Dalmatia County. The town is situated approximately south-east of Croatia's second largest city, Split. Its location is w ...

yielded to Venice in 1444, and only Ragusa (Dubrovnik) preserved temporarily its freedom.

The rule of Venice on most of Dalmatia will last nearly four centuries (1420 - 1797).

The rule of Venice on most of Dalmatia will last nearly four centuries (1420 - 1797).

Early modern period

The Republic of Venice (1420–1796) and Dalmatian

After the fall of theWestern Roman Empire

The Western Roman Empire comprised the western provinces of the Roman Empire at any time during which they were administered by a separate independent Imperial court; in particular, this term is used in historiography to describe the period ...

, Illyrian towns on the Dalmatian coast continued to speak Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

and their language evolved relatively independent from other Romance languages

The Romance languages, sometimes referred to as Latin languages or Neo-Latin languages, are the various modern languages that evolved from Vulgar Latin. They are the only extant subgroup of the Italic languages in the Indo-European language ...

, progressing towards a regional variant and finally to a distinct neo-Latin language called Dalmatian (today extinct). The earliest reference on the language dates from the 10th century and it is estimated that about 50,000 people spoke it at that time along the eastern Adriatic in the Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; hr, Dalmacija ; it, Dalmazia; see names in other languages) is one of the four historical regions of Croatia, alongside Croatia proper, Slavonia, and Istria. Dalmatia is a narrow belt of the east shore of the Adriatic Sea, str ...

n coast from Fiume (Rijeka) as far south as Kotor

Kotor ( Montenegrin Cyrillic: Котор, ), historically known as Cattaro (from Italian: ), is a coastal town in Montenegro. It is located in a secluded part of the Bay of Kotor. The city has a population of 13,510 and is the administrative ...

(Cattaro) in Montenegro

)

, image_map = Europe-Montenegro.svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Podgorica

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, official_languages = ...

(according to the linguist Matteo Bartoli

Matteo Giulio Bartoli (22 November 1873 in Labin/Albona – 23 January 1946 in Turin) was an Italian linguist from Istria (then a part of Austria-Hungary, today part of modern Croatia).

He obtained a doctorate at the University of Vienna, wh ...

).

The Dalmatian speakers lived mainly in the coastal towns of Zadar

Zadar ( , ; historically known as Zara (from Venetian and Italian: ); see also other names), is the oldest continuously inhabited Croatian city. It is situated on the Adriatic Sea, at the northwestern part of Ravni Kotari region. Zadar ser ...

, Trogir

Trogir (; historically known as Traù (from Dalmatian language, Dalmatian, Venetian language, Venetian and Italian language, Italian: ); la, Tragurium; Greek language, Ancient Greek: Τραγύριον, ''Tragyrion'' or Τραγούριον, '' ...

, Split

Split(s) or The Split may refer to:

Places

* Split, Croatia, the largest coastal city in Croatia

* Split Island, Canada, an island in the Hudson Bay

* Split Island, Falkland Islands

* Split Island, Fiji, better known as Hạfliua

Arts, entertai ...

, Dubrovnik

Dubrovnik (), historically known as Ragusa (; see notes on naming), is a city on the Adriatic Sea in the region of Dalmatia, in the southeastern semi-exclave of Croatia. It is one of the most prominent tourist destinations in the Mediterranea ...

and Kotor

Kotor ( Montenegrin Cyrillic: Котор, ), historically known as Cattaro (from Italian: ), is a coastal town in Montenegro. It is located in a secluded part of the Bay of Kotor. The city has a population of 13,510 and is the administrative ...

(''Zara, Traù, Spalato, Ragusa'' and ''Cattaro'' in Italian and in Dalmatian), each of these cities having a local dialect, and also on the islands of Krk, Cres

Cres (; dlm, Crepsa, vec, Cherso, it, Cherso, la, Crepsa, Greek: Χέρσος, ''Chersos'') is an Adriatic island in Croatia. It is one of the northern islands in the Kvarner Gulf and can be reached via ferry from Rijeka, the island K ...

and Rab

Rab �âːb( dlm, Arba, la, Arba, it, Arbe, german: Arbey) is an island in the northern Dalmatia region in Croatia, located just off the northern Croatian coast in the Adriatic Sea.

The island is long, has an area of and 9,328 inhabitants (2 ...

(''Veglia, Cherso'' and ''Arbe'')

Almost every city developed its own dialect, but the most important dialects we have information on are the ''Vegliot'' a northern dialect, spoken on the island of Krk (''Veglia'' in Italian, ''Vikla'' in Dalmatian) and the ''Ragusan, a southern dialect, spoken at Dubrovnik (''Ragusa'' in both Italian and Dalmatian).

The dialect of Zara disappeared merging with Venetian

Venetian often means from or related to:

* Venice, a city in Italy

* Veneto, a region of Italy

* Republic of Venice (697–1797), a historical nation in that area

Venetian and the like may also refer to:

* Venetian language, a Romance language s ...

because of the strong and long lasting influence of Republic of Venice

The Republic of Venice ( vec, Repùblega de Venèsia) or Venetian Republic ( vec, Repùblega Vèneta, links=no), traditionally known as La Serenissima ( en, Most Serene Republic of Venice, italics=yes; vec, Serenìsima Repùblega de Venèsia ...

, as did the two other dialects even to the assimilation by Slavic speakers.

We know about the Dalmatian dialect of Ragusa from two letters, from 1325 and 1397, and many medieval texts, which show a language influenced heavily by Venetian

Venetian often means from or related to:

* Venice, a city in Italy

* Veneto, a region of Italy

* Republic of Venice (697–1797), a historical nation in that area

Venetian and the like may also refer to:

* Venetian language, a Romance language s ...

. The available sources include hardly 260 Ragusan words. Surviving words include ''pen'' (bread), ''teta'' (father), ''chesa'' (house) and ''fachir'' (to do), which were quoted by an Italian, Fillipo Diversi, the head of school of Ragusa in the 1430s.

The Republic of Ragusa

The Republic of Ragusa ( dlm, Republica de Ragusa; la, Respublica Ragusina; it, Repubblica di Ragusa; hr, Dubrovačka Republika; vec, Repùblega de Raguxa) was an aristocratic maritime republic centered on the city of Dubrovnik (''Ragusa'' ...

had at one time an important fleet, but its influence decreased. We know that the language was in trouble in the face of Croatian expansion, as the Ragusan Senate decided that all debates had to be held in ''Lingua veteri ragusea'' (ancient Romance Ragusan) and the use of the ''lingua sclava'' ( Croatian) was forbidden. Nevertheless, in the 17th century, Ragusan fell out of use and became extinct.

Other languages influenced Dalmatian, but without erasing its Latin roots (superstrates): the Slavs, then the

Other languages influenced Dalmatian, but without erasing its Latin roots (superstrates): the Slavs, then the Republic of Venice

The Republic of Venice ( vec, Repùblega de Venèsia) or Venetian Republic ( vec, Repùblega Vèneta, links=no), traditionally known as La Serenissima ( en, Most Serene Republic of Venice, italics=yes; vec, Serenìsima Repùblega de Venèsia ...

. Several cities of the regions have Italian names, and other mostly the romanized Illyrian ones (like Zara, Spalato, etc.)

The oldest preserved documents written in Dalmatian are some 13th century inventories, in the Ragusan dialect. A letter of the 14th century from Zara (Zadar) shows strong Venetian influence, which was also the cause of its extinction soon after.

The Christian schism was an important factor in the history of Dalmatia. While the Croatian-held branch of the Catholic Church in Nin was under Papal

The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

jurisdiction, they still used the Slavic liturgy

Liturgy is the customary public ritual of worship performed by a religious group. ''Liturgy'' can also be used to refer specifically to public worship by Christians. As a religious phenomenon, liturgy represents a communal response to and partic ...

. Both the Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

population of the cities and the Holy See

The Holy See ( lat, Sancta Sedes, ; it, Santa Sede ), also called the See of Rome, Petrine See or Apostolic See, is the jurisdiction of the Pope in his role as the bishop of Rome. It includes the apostolic episcopal see of the Diocese of R ...

preferred the Latin liturgy, which created tensions between different dioceses. The Croatian population preferred domestic priests, who were married and bearded, and held masses in Croatian, so they were understood.

The great schism between Eastern and Western Christianity 1054 further intensified the rift between the coastal cities and the hinterland, with many of the Slavs in the hinterland preferring the Eastern Orthodoxy

Eastern Orthodoxy, also known as Eastern Orthodox Christianity, is one of the three main branches of Chalcedonian Christianity, alongside Catholicism and Protestantism.

Like the Pentarchy of the first millennium, the mainstream (or " canonic ...

. Areas of today's Bosnia and Herzegovina

Bosnia and Herzegovina ( sh, / , ), abbreviated BiH () or B&H, sometimes called Bosnia–Herzegovina and often known informally as Bosnia, is a country at the crossroads of south and southeast Europe, located in the Balkans. Bosnia and ...

also had an indigenous Bosnian Church

The Bosnian Church ( sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=/, Crkva bosanska, Црква Босанска) was a Christian church in medieval Bosnia and Herzegovina that was independent of and considered heretical by both the Catholic and the Eastern Orthodo ...

which was often mistaken for Bogomils

Bogomilism ( Bulgarian and Macedonian: ; sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", bogumilstvo, богумилство) was a Christian neo-Gnostic or dualist sect founded in the First Bulgarian Empire by the priest Bogomil during the reign of Tsar P ...

.

The Latin influence in Dalmatia was increased and the Byzantine practices were further suppressed on the general synods 1059–1060, 1066, 1075–1076 and on other local synods, notably by demoting the bishopric of Nin, installing the archbishoprics of Spalatum (Split

Split(s) or The Split may refer to:

Places

* Split, Croatia, the largest coastal city in Croatia

* Split Island, Canada, an island in the Hudson Bay

* Split Island, Falkland Islands

* Split Island, Fiji, better known as Hạfliua

Arts, entertai ...

) and Dioclea (Montenegro

)

, image_map = Europe-Montenegro.svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Podgorica

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, official_languages = ...

), and explicitly forbidding use of any liturgy other than Greek or Latin.

In the period of the rise of the Serbian state of Rascia, the Nemanjić dynasty acquired the southern Dalmatian states by the end of the 12th century, where the population was mixed Catholic and Orthodox, and founded a Serbian Orthodox

The Serbian Orthodox Church ( sr-Cyrl, Српска православна црква, Srpska pravoslavna crkva) is one of the autocephalous ( ecclesiastically independent) Eastern Orthodox Christian churches.

The majority of the population ...

bishopric

In church governance, a diocese or bishopric is the ecclesiastical district under the jurisdiction of a bishop.

History

In the later organization of the Roman Empire, the increasingly subdivided provinces were administratively associate ...

of Zahumlje

Zachlumia or Zachumlia ( sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Zahumlje, Захумље, ), also Hum, was a medieval principality located in the modern-day regions of Herzegovina and southern Dalmatia (today parts of Bosnia and Herzegovina and Croatia ...

with see in Ston

Ston () is a settlement and a municipality in the Dubrovnik-Neretva County of Croatia, located at the south of isthmus of the Pelješac peninsula.

History

Because of its geopolitical and strategic position, Ston has had a rich history since ant ...

. The Nemanjić Serbia controlled several of the southern coastal cities, notably Kotor (Cattaro) and Bar (Antivari).

In the 13th century the Republic of Venice took definitive control of the Montenegro coast and created the ''Albania Veneta

Venetian Albania ( vec, Albania vèneta, it, Albania Veneta, Serbian and Montenegrin: Млетачка Албанија / ''Mletačka Albanija'', ) was the official term for several possessions of the Republic of Venice in the southeastern Adri ...

''.

Dalmatia never attained a political or racial unity and never formed as a nation, but it achieved a remarkable development of art, science and literature. Politically, the neolatin Dalmatian city-states were often isolated and compelled to either fall back on the Venetian Republic for support, or tried to make it on their own.

The geographical position of the Dalmatian city states suffices to explain the relatively small influence exercised by Byzantine culture throughout the six centuries (535-1102) during which Dalmatia was part of the Eastern empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

. Towards the close of this period Byzantine rule tended more and more to become merely nominal, while the influence of the Republic of Venice increased.

The medieval Dalmatia had still included much of the hinterland covered by the old Roman province of Dalmatia. However, the toponym of "Dalmatia" started to shift more towards including only the coastal, Adriatic areas, rather than the mountains inland. By the 15th century, the word "Herzegovina

Herzegovina ( or ; sh-Latn-Cyrl, Hercegovina, separator=" / ", Херцеговина, ) is the southern and smaller of two main geographical region of Bosnia and Herzegovina, the other being Bosnia. It has never had strictly defined geogra ...

" would be introduced, marking the shrink of the borders of Dalmatia to the narrow littoral area where Dalmatian was spoken (which was being assimilated into the Venetian

Venetian often means from or related to:

* Venice, a city in Italy

* Veneto, a region of Italy

* Republic of Venice (697–1797), a historical nation in that area

Venetian and the like may also refer to:

* Venetian language, a Romance language s ...

).

Ottoman and Venetian rule

Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

in 1453, Serbia

Serbia (, ; Serbian: , , ), officially the Republic of Serbia ( Serbian: , , ), is a landlocked country in Southeastern and Central Europe, situated at the crossroads of the Pannonian Basin and the Balkans. It shares land borders with Hu ...

in 1459, neighbouring Bosnia

Bosnia and Herzegovina ( sh, / , ), abbreviated BiH () or B&H, sometimes called Bosnia–Herzegovina and Pars pro toto#Geography, often known informally as Bosnia, is a country at the crossroads of Southern Europe, south and southeast Euro ...

in 1463, and Herzegovina

Herzegovina ( or ; sh-Latn-Cyrl, Hercegovina, separator=" / ", Херцеговина, ) is the southern and smaller of two main geographical region of Bosnia and Herzegovina, the other being Bosnia. It has never had strictly defined geogra ...

in 1483. Thus the Venetian and Ottoman frontiers met and border wars were incessant.

Dubrovnik sought safety in friendship with the invaders, and in one particular instance, actually sold two small strips of its territory ( Neum and Sutorina) to the Ottomans in order to prevent land access from the Venetian territory.

In 1508 the hostile League of Cambrai compelled Venice to withdraw its garrison for home service, and after the overthrow of Hungary in 1526 the Turks were able easily to conquer the greater part of Dalmatia by 1537, when the Siege of Klis

The siege of Klis or Battle of Klis ( hr, Opsada Klisa, Bitka kod Klisa, tr, Klise Kuşatması) was a siege of Klis Fortress in the Kingdom of Croatia within Habsburg monarchy. The siege of the fortress, which lasted for more than two decad ...

ended with the fall of the Klis Fortress to the Ottomans. The peace 1540 left only the maritime cities to Venice, the interior forming a Turkish province, governed from as the Sanjak of Klis

The Sanjak of Klis ( tr, Kilis Sancağı; sh, Kliški sandžak) was a sanjak of the Ottoman Empire which seat was in the Fortress of Klis in Klis (modern-day Croatia) till capture by Republic of Venice in 1648, latterly in Livno between 1648-18 ...

, part of the Eyalet of Bosnia

The Eyalet of Bosnia ( ota, ایالت بوسنه ,Eyālet-i Bōsnâ; By Gábor Ágoston, Bruce Alan Masters ; sh, Bosanski pašaluk), was an eyalet (administrative division, also known as a ''beylerbeylik'') of the Ottoman Empire, mostly based ...

.

Christian Croats from the neighbouring lands now thronged to the towns, outnumbering the Romanic population even more, and making their language the primary one. The pirate community of the "uskoks

The Uskoks ( hr, Uskoci, , singular: ; notes on naming) were irregular soldiers in Habsburg Croatia that inhabited areas on the eastern Adriatic coast and surrounding territories during the Ottoman wars in Europe. Bands of Uskoks fought a g ...

" had originally been a band of these fugitives, esp. near Senia; its exploits contributed to a renewal of war between Venice and Turkey (1571–1573). An extremely curious picture of contemporary manners is presented by the Venetian agents, whose reports on this war resemble some knightly chronicle of the Middle Ages, full of single combats, tournaments and other chivalrous adventures. They also show clearly that the Dalmatian levies far surpassed the Italian mercenaries in skill and courage. Many of these troops served abroad; at the Battle of Lepanto

The Battle of Lepanto was a naval engagement that took place on 7 October 1571 when a fleet of the Holy League, a coalition of Catholic states (comprising Spain and its Italian territories, several independent Italian states, and the Soverei ...

, for example, in 1571, a Dalmatian squadron assisted the allied fleets of Spain, Venice, Austria and the Papal States to crush the Turkish navy.

The Ottomans

The Ottoman Turks ( tr, Osmanlı Türkleri), were the Turkic founding and sociopolitically the most dominant ethnic group of the Ottoman Empire ( 1299/1302–1922).

Reliable information about the early history of Ottoman Turks remains scarce, ...

resettled Orthodox Serbs

The Serbs ( sr-Cyr, Срби, Srbi, ) are the most numerous South Slavs, South Slavic ethnic group native to the Balkans in Southeastern Europe, who share a common Serbian Cultural heritage, ancestry, Culture of Serbia, culture, History of ...

from Bosnia

Bosnia and Herzegovina ( sh, / , ), abbreviated BiH () or B&H, sometimes called Bosnia–Herzegovina and Pars pro toto#Geography, often known informally as Bosnia, is a country at the crossroads of Southern Europe, south and southeast Euro ...

into the desolated areas of the Kninska Krajina and Bukovica Bukovica may refer to:

Croatia

*Bukovica, Dalmatia, a geographical region in Croatia

* Bukovica, Sisak-Moslavina County, a village near Topusko

* Bukovica, Brod-Posavina County, a village near Rešetari

* Nova Bukovica, a village and municipality ...

, while Boka Kotorska

The Bay of Kotor ( Montenegrin and Serbian: , Italian: ), also known as the Boka, is a winding bay of the Adriatic Sea in southwestern Montenegro and the region of Montenegro concentrated around the bay. It is also the southernmost part of the hi ...

received constant Serb migrations from Herzegovina

Herzegovina ( or ; sh-Latn-Cyrl, Hercegovina, separator=" / ", Херцеговина, ) is the southern and smaller of two main geographical region of Bosnia and Herzegovina, the other being Bosnia. It has never had strictly defined geogra ...

and Montenegro

)

, image_map = Europe-Montenegro.svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Podgorica

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, official_languages = ...

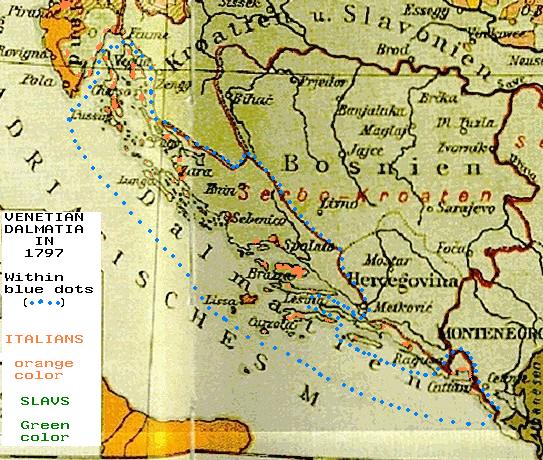

. The Serbs formed a significant part of the population of Dalmatia in the 16th century, with absolute majorities in the Kninska Krajina, Bukovica and Boka Kotorska. A great portion of this population fled to Venetian land and gladly fought against the Ottomans. The number of Serbs in Venetian Dalmatia rapidly increased during the War of Candia in 1645 - 1669 and the Great Turkish War

The Great Turkish War (german: Großer Türkenkrieg), also called the Wars of the Holy League ( tr, Kutsal İttifak Savaşları), was a series of conflicts between the Ottoman Empire and the Holy League consisting of the Holy Roman Empire, Pola ...

in 1683 - 1699, after which the peace of Karlowitz

The Treaty of Karlowitz was signed in Karlowitz, Military Frontier of Archduchy of Austria (present-day Sremski Karlovci, Serbia), on 26 January 1699, concluding the Great Turkish War of 1683–1697 in which the Ottoman Empire was defeated by ...

gave Venice the whole of Dalmatia as far south as Ston

Ston () is a settlement and a municipality in the Dubrovnik-Neretva County of Croatia, located at the south of isthmus of the Pelješac peninsula.

History

Because of its geopolitical and strategic position, Ston has had a rich history since ant ...

, as well as the region beyond Ragusa, from Sutorina to Boka kotorska

The Bay of Kotor ( Montenegrin and Serbian: , Italian: ), also known as the Boka, is a winding bay of the Adriatic Sea in southwestern Montenegro and the region of Montenegro concentrated around the bay. It is also the southernmost part of the hi ...

. After the Venetian-Turkish war 1714–1718, Venetian territorial gains were confirmed by the 1718 Treaty of Passarowitz.

The Venetian Republic promised the peasant population of the hinterland freedom from feudal

Feudalism, also known as the feudal system, was the combination of the legal, economic, military, cultural and political customs that flourished in medieval Europe between the 9th and 15th centuries. Broadly defined, it was a way of structur ...

bounds in return for their military service.

The Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

, as the religion of both the Venetians and the Croats, exerted the majority influence over the region. The Serbian Orthodox Church

The Serbian Orthodox Church ( sr-Cyrl, Српска православна црква, Srpska pravoslavna crkva) is one of the autocephalous (ecclesiastically independent) Eastern Orthodox Christian denomination, Christian churches.

The majori ...

in Dalmatia built several monasteries in the hinterland such as the early 14th-century Krupa, Krka and Dragović.

Dalmatia experienced a period of intense economic and cultural growth in the 18th century, given how trade routes with the hinterland were reestablished in peace.

Because the Venetians were able to reclaim some of the inland territories in the north during the Turkish wars, the toponym of Dalmatia was no longer restricted to the coastline and the islands. The border between the Dalmatian hinterland and the Ottoman Bosnia and Herzegovina

The Ottoman Empire era of rule in Bosnia and Herzegovina (first as a ''sanjak'', then as an ''eyalet'') and Herzegovina (also as a ''sanjak'', then ''eyalet'') lasted from 1463/1482 to 1878 ''de facto'', and until 1908 ''de jure''.

Ottoman ...

greatly fluctuated until the Morean War