Hirohito on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

, and Emperor Fushimi">Fushimi have ''senso'' and ''sokui'' in the same year until the reign of Emperor Go-Murakami">Go-Murakami;] Ponsonby-Fane, p. 350. The Taishō period, Taishō era's end and the Shōwa period, Shōwa era's beginning (Enlightened Peace) were proclaimed. The deceased Emperor was posthumously renamed Emperor Taishō within days. Following Japanese custom, the new Emperor was never referred to by his given name but rather was referred to simply as "His Majesty the Emperor" which may be shortened to "His Majesty." In writing, the Emperor was also referred to formally as "The Reigning Emperor."

In November 1928, the Emperor's ascension was confirmed in

Emperor , commonly known in English-speaking countries by his personal name , was the 124th

Hirohito was born in Tokyo's Aoyama Palace (during the reign of his grandfather,

Hirohito was born in Tokyo's Aoyama Palace (during the reign of his grandfather,

From 3 March to 3 September 1921 (Taisho 10), the Crown Prince made official visits to the

From 3 March to 3 September 1921 (Taisho 10), the Crown Prince made official visits to the  The departure of Prince Hirohito was widely reported in newspapers. The Japanese battleship ''Katori'' was used and departed from

The departure of Prince Hirohito was widely reported in newspapers. The Japanese battleship ''Katori'' was used and departed from

After returning to Japan, Hirohito became

After returning to Japan, Hirohito became

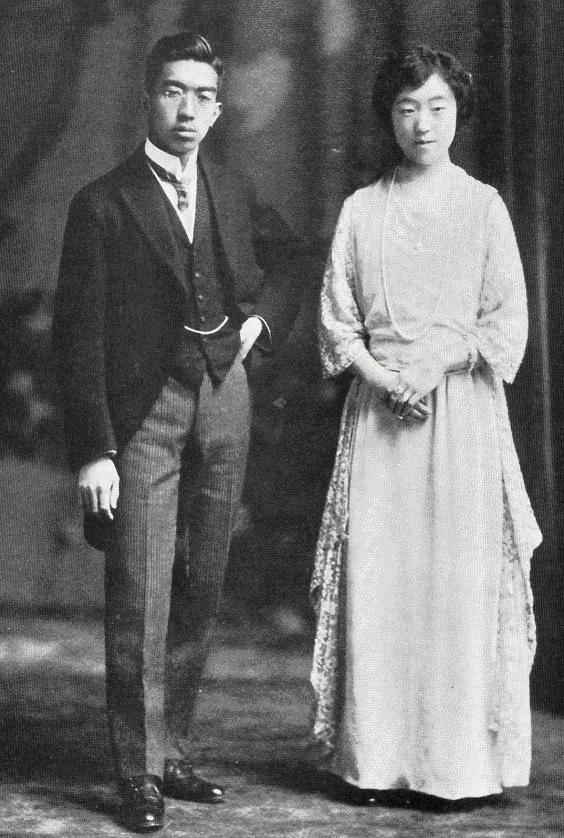

Prince Hirohito married his distant cousin Princess Nagako Kuni, the eldest daughter of

Prince Hirohito married his distant cousin Princess Nagako Kuni, the eldest daughter of

On 25 December 1926, Hirohito assumed the throne upon the death of his father, Yoshihito. The Crown Prince was said to have received the succession (''senso'').Varley, H. Paul, ed. (1980). '' Jinnō Shōtōki ("A Chronicle of Gods and Sovereigns: Jinnō Shōtōki of Kitabatake Chikafusa" translated by H. Paul Varley)'', p. 44. _distinct_act_of_''senso''_is_unrecognized_prior_to_Emperor_Tenji;_and_all_sovereigns_except_ _distinct_act_of_''senso''_is_unrecognized_prior_to_Emperor_Tenji;_and_all_sovereigns_except_Empress_Jitō">Jitō,_

On 25 December 1926, Hirohito assumed the throne upon the death of his father, Yoshihito. The Crown Prince was said to have received the succession (''senso'').Varley, H. Paul, ed. (1980). '' Jinnō Shōtōki ("A Chronicle of Gods and Sovereigns: Jinnō Shōtōki of Kitabatake Chikafusa" translated by H. Paul Varley)'', p. 44. _distinct_act_of_''senso''_is_unrecognized_prior_to_Emperor_Tenji;_and_all_sovereigns_except_ _distinct_act_of_''senso''_is_unrecognized_prior_to_Emperor_Tenji;_and_all_sovereigns_except_Empress_Jitō">Jitō,__

_was_the_82nd_emperor_of_Japan,_according_to_the_traditional_order_of_succession._His_reign_spanned_the_years_from_1183_through_1198.

This_12th-century_sovereign_was_named_after_Emperor_Toba,_and_''go-''_(後),_translates_literally_as_"later";_an_...

,_and_Emperor_Fushimi">Fushimi_have_''senso''_and_''sokui''_in_the_same_year_until_the_reign_of_Emperor_Go-Murakami.html" ;"title="Emperor_Fushimi.html" ;"title="Emperor_Yōzei">Yōzei,_Emperor_Go-Toba.html" "title="Emperor_Yōzei.html" ;"title="Empress_Jitō.html" ;"title="Emperor_Tenji.html" ;"title=" distinct act of ''senso'' is unrecognized prior to Emperor Tenji"> distinct act of ''senso'' is unrecognized prior to Emperor Tenji; and all sovereigns except Empress Jitō">Jitō, Emperor Yōzei">Yōzei, Emperor Go-Toba">Go-Toba

was the 82nd emperor of Japan, according to the traditional order of succession. His reign spanned the years from 1183 through 1198.

This 12th-century sovereign was named after Emperor Toba, and ''go-'' (後), translates literally as "later"; an ...emperor of Japan

The Emperor of Japan is the monarch and the head of the Imperial Family of Japan. Under the Constitution of Japan, he is defined as the symbol of the Japanese state and the unity of the Japanese people, and his position is derived from "the ...

, ruling from 25 December 1926 until his death in 1989. Hirohito and his wife, Empress Kōjun, had two sons and five daughters; he was succeeded by his fifth child and eldest son, Akihito

is a member of the Imperial House of Japan who reigned as the 125th emperor of Japan from 7 January 1989 until his abdication on 30 April 2019. He presided over the Heisei era, ''Heisei'' being an expression of achieving peace worldwide.

B ...

. By 1979, Hirohito was the only monarch in the world with the title "emperor". He was the longest-reigning historical Japanese emperor and one of the longest-reigning monarchs in the world.

Hirohito was the head of state

A head of state (or chief of state) is the public persona who officially embodies a state Foakes, pp. 110–11 " he head of statebeing an embodiment of the State itself or representatitve of its international persona." in its unity and ...

under the Meiji Constitution during Japan's imperial expansion, militarization

Militarization, or militarisation, is the process by which a society organizes itself for military conflict and violence. It is related to militarism, which is an ideology that reflects the level of militarization of a state. The process of milit ...

, and involvement in World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

. Japan waged a war across Asia in the 1930s and 40s in the name of Hirohito, who was revered as a god. After Japan's surrender, he was not prosecuted for war crimes, as General Douglas MacArthur thought that an ostensibly cooperative emperor would help establish a peaceful Allied occupation, and help the U.S. achieve their postwar objectives. His role during the war remains controversial. On 1 January 1946, under pressure from the Allies, the Emperor formally renounced his divinity.

The Constitution of Japan

The Constitution of Japan (Shinjitai: , Kyūjitai: , Hepburn romanization, Hepburn: ) is the constitution of Japan and the supreme law in the state. Written primarily by American civilian officials working under the Allied occupation of Japa ...

of 1947 declared the Emperor to be a mere "symbol of the State ... deriving his position from the will of the people in whom resides sovereign power."

In Japan, reigning emperors are known only as "the Emperor". Hirohito is now referred to in Japanese by his posthumous name

A posthumous name is an honorary name given mostly to the notable dead in East Asian culture. It is predominantly practiced in East Asian countries such as China, Korea, Vietnam, Japan, and Thailand. Reflecting on the person's accomplishm ...

, Shōwa, which is the name of the era coinciding with his reign.

Early life

Hirohito was born in Tokyo's Aoyama Palace (during the reign of his grandfather,

Hirohito was born in Tokyo's Aoyama Palace (during the reign of his grandfather, Emperor Meiji

, also called or , was the 122nd emperor of Japan according to the traditional order of succession. Reigning from 13 February 1867 to his death, he was the first monarch of the Empire of Japan and presided over the Meiji era. He was the figur ...

) on 29 April 1901, the first son of 21-year-old Crown Prince

A crown prince or hereditary prince is the heir apparent to the throne in a royal or imperial monarchy. The female form of the title is crown princess, which may refer either to an heiress apparent or, especially in earlier times, to the w ...

Yoshihito (the future Emperor Taishō) and 17-year-old Crown Princess Sadako (the future Empress Teimei). He was the grandson of Emperor Meiji and Yanagihara Naruko

Yanagiwara Naruko (Japanese: 柳原愛子), also known as Sawarabi no Tsubone (26 June 1859 – 16 October 1943), was a Japanese lady-in-waiting of the Imperial House of Japan. A concubine of Emperor Meiji, she was the mother of Emperor Taishō ...

. His childhood title was Prince Michi.

Ten weeks after he was born, Hirohito was removed from the court and placed in the care of Count Kawamura Sumiyoshi, who raised him as his grandchild. At the age of 3, Hirohito and his brother Yasuhito were returned to court when Kawamura died – first to the imperial mansion in Numazu, Shizuoka, then back to the Aoyama Palace.

In 1908 he began elementary studies at the Gakushūin (Peers School). During 1912, at age 11, Hirohito was commissioned into the Imperial Japanese Army

The was the official ground-based armed force of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945. It was controlled by the Imperial Japanese Army General Staff Office and the Ministry of the Army, both of which were nominally subordinate to the Emper ...

as a Second Lieutenant and in the Imperial Japanese Navy

The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN; Kyūjitai: Shinjitai: ' 'Navy of the Greater Japanese Empire', or ''Nippon Kaigun'', 'Japanese Navy') was the navy of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945, when it was dissolved following Japan's surrender ...

as an Ensign. He was also bestowed with the Grand Cordon of the Order of the Chrysanthemum. When his grandfather, Emperor Meiji

, also called or , was the 122nd emperor of Japan according to the traditional order of succession. Reigning from 13 February 1867 to his death, he was the first monarch of the Empire of Japan and presided over the Meiji era. He was the figur ...

, died on 30 July 1912, Hirohito's father, Yoshihito, assumed the throne.

Crown Prince era

On 2 November 1916, Hirohito was formally proclaimed Crown Prince andheir apparent

An heir apparent, often shortened to heir, is a person who is first in an order of succession and cannot be displaced from inheriting by the birth of another person; a person who is first in the order of succession but can be displaced by the b ...

. An investiture ceremony was not required to confirm this status.

Overseas travel

From 3 March to 3 September 1921 (Taisho 10), the Crown Prince made official visits to the

From 3 March to 3 September 1921 (Taisho 10), the Crown Prince made official visits to the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and ...

, France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, the Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

, Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to ...

, Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

and Vatican City

Vatican City (), officially the Vatican City State ( it, Stato della Città del Vaticano; la, Status Civitatis Vaticanae),—'

* german: Vatikanstadt, cf. '—' (in Austria: ')

* pl, Miasto Watykańskie, cf. '—'

* pt, Cidade do Vati ...

. This was the first visit to Western Europe by the Crown Prince. Despite strong opposition in Japan, this was realized by the efforts of elder Japanese statesmen ( Genrō) such as Yamagata Aritomo and Saionji Kinmochi

Prince was a Japanese politician and statesman who served as Prime Minister of Japan from 1906 to 1908 and from 1911 to 1912. He was elevated from marquis to prince in 1920. As the last surviving member of Japan's '' genrō,'' he was the most ...

.

The departure of Prince Hirohito was widely reported in newspapers. The Japanese battleship ''Katori'' was used and departed from

The departure of Prince Hirohito was widely reported in newspapers. The Japanese battleship ''Katori'' was used and departed from Yokohama

is the second-largest city in Japan by population and the most populous municipality of Japan. It is the capital city and the most populous city in Kanagawa Prefecture, with a 2020 population of 3.8 million. It lies on Tokyo Bay, south of T ...

, sailed to Naha, Hong Kong

Hong Kong ( (US) or (UK); , ), officially the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China (abbr. Hong Kong SAR or HKSAR), is a List of cities in China, city and Special administrative regions of China, special ...

, Singapore

Singapore (), officially the Republic of Singapore, is a sovereign island country and city-state in maritime Southeast Asia. It lies about one degree of latitude () north of the equator, off the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula, bor ...

, Colombo

Colombo ( ; si, කොළඹ, translit=Koḷam̆ba, ; ta, கொழும்பு, translit=Koḻumpu, ) is the executive and judicial capital and largest city of Sri Lanka by population. According to the Brookings Institution, Colombo me ...

, Suez, Cairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the largest urban agglomeration in Africa, the Arab world and the Middle East: The Greater Cairo metr ...

, and Gibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = "Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gibr ...

. It arrived in Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port and city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a unitary authority since 1 April 1997 and is administered by Portsmouth City Council.

Portsmouth is the most d ...

two months later on 9 May, and on the same day they reached the British capital London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

. He was welcomed in the UK as a partner of the Anglo-Japanese Alliance and met with King George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until his death in 1936.

Born during the reign of his grandmother Qu ...

and Prime Minister David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor, (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. He was a Liberal Party (United Kingdom), Liberal Party politician from Wales, known for lea ...

. That evening, a banquet was held at Buckingham Palace and a meeting with George V and Prince Arthur of Connaught. George V said that he treated his father like Hirohito, who was nervous in an unfamiliar foreign country, and that relieved his tension. The next day, he met Prince Edward (the future Edward VIII) at Windsor Castle

Windsor Castle is a royal residence at Windsor in the English county of Berkshire. It is strongly associated with the English and succeeding British royal family, and embodies almost a millennium of architectural history.

The original c ...

, and a banquet was held every day thereafter. In London, he toured the British Museum

The British Museum is a public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is among the largest and most comprehensive in existence. It docum ...

, Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, which is sep ...

, Bank of England

The Bank of England is the central bank of the United Kingdom and the model on which most modern central banks have been based. Established in 1694 to act as the English Government's banker, and still one of the bankers for the Government o ...

, Lloyd's Marine Insurance, Oxford University

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

, Army University, and Naval War College. He also enjoyed theater at the New Oxford Theatre

Oxford Music Hall was a music hall located in Westminster, London at the corner of Oxford Street and Tottenham Court Road. It was established on the site of a former public house, the Boar and Castle, by Charles Morton, in 1861. In 1917 the music ...

and the Delhi Theatre. At Cambridge University

, mottoeng = Literal: From here, light and sacred draughts.

Non literal: From this place, we gain enlightenment and precious knowledge.

, established =

, other_name = The Chancellor, Masters and Schola ...

, he listened to Professor Tanner's lecture on "Relationship between the British Royal Family and its People" and was awarded an honorary doctorate

An honorary degree is an academic degree for which a university (or other degree-awarding institution) has waived all of the usual requirements. It is also known by the Latin phrases ''honoris causa'' ("for the sake of the honour") or ''ad hono ...

degree. He visited Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

, Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to ...

, from the 19th to the 20th, and was also awarded an Honorary Doctor of Laws at the University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh ( sco, University o Edinburgh, gd, Oilthigh Dhùn Èideann; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in post-nominals) is a public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Granted a royal charter by King James VI in 1 ...

. He stayed at the residence of John Stewart-Murray, 8th Duke of Atholl, for three days. On his stay with Stuart-Murray, the prince was quoted as saying, "The rise of Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

won't happen if you live a simple life like Duke Athol."

In Italy, he met with King Vittorio Emanuele III and others, attended official banquets in various countries, and visited places such as the fierce battlefields of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

.

Regency

After returning to Japan, Hirohito became

After returning to Japan, Hirohito became Regent

A regent (from Latin : ruling, governing) is a person appointed to govern a state '' pro tempore'' (Latin: 'for the time being') because the monarch is a minor, absent, incapacitated or unable to discharge the powers and duties of the monarchy ...

of Japan ( Sesshō) on 25 November 1921, in place of his ailing father, who was affected by mental illness. In 1923 he was promoted to the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel in the army and Commander in the navy, and army Colonel and Navy Captain in 1925.

During Hirohito's regency, many important events occurred:

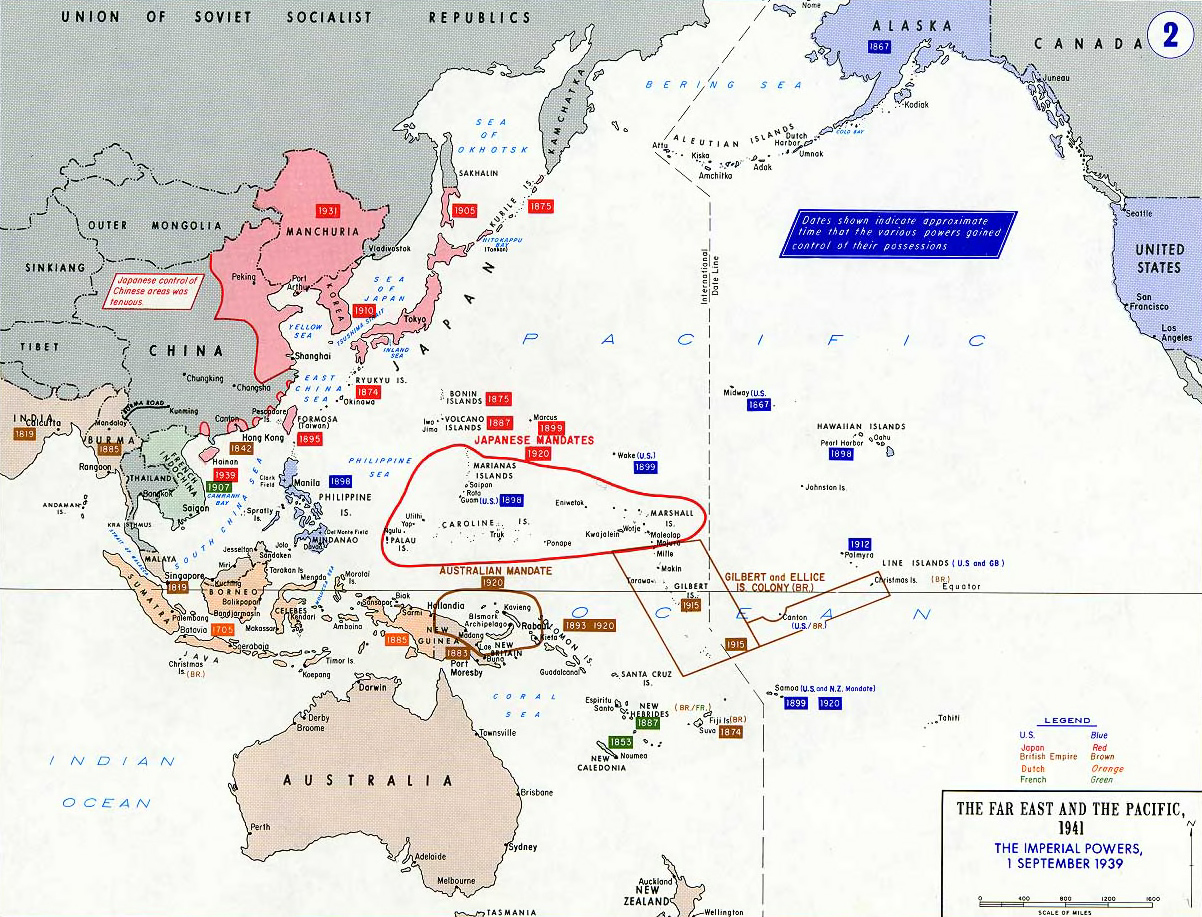

In the Four-Power Treaty on Insular Possessions signed on 13 December 1921, Japan, the United States, Britain, and France agreed to recognize the status quo in the Pacific. Japan and Britain agreed to end the Anglo-Japanese Alliance. The Washington Naval Treaty limiting warship numbers was signed on 6 February 1922. Japan withdrew troops from the Siberian Intervention

The Siberian intervention or Siberian expedition of 1918–1922 was the dispatch of troops of the Entente powers to the Russian Maritime Provinces as part of a larger effort by the western powers, Japan, and China to support White Russian fo ...

on 28 August 1922. The Great Kantō earthquake devastated Tokyo on 1 September 1923. On 27 December 1923, Daisuke Namba

was a Japanese student who tried to assassinate the Crown Prince Regent Hirohito in the Toranomon Incident on December 27, 1923.

Family and early life

Daisuke Nanba was born to a distinguished family. His grandfather was decorated by the Emper ...

attempted to assassinate Hirohito in the Toranomon Incident, but his attempt failed. During interrogation, he claimed to be a communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, ...

and was executed.

Marriage

Prince Kuniyoshi Kuni

was a member of the Japanese imperial family and a field marshal in the Imperial Japanese Army during the Meiji and Taishō periods. He was the father of Empress Kōjun (who in turn was the consort of the Emperor Shōwa), and therefore, the mate ...

, on 26 January 1924. They had two sons and five daughters (see Issue).

The daughters who lived to adulthood left the imperial family as a result of the American reforms of the Japanese imperial household in October 1947 (in the case of Princess Shigeko) or under the terms of the Imperial Household Law at the moment of their subsequent marriages (in the cases of Princesses Kazuko, Atsuko, and Takako).

Ascension

_distinct_act_of_''senso''_is_unrecognized_prior_to_Emperor_Tenji;_and_all_sovereigns_except_Empress_Jitō">Jitō,_ Yōzei,_Emperor_Go-Toba.html"__"title="Emperor_Yōzei.html"_;"title="Empress_Jitō.html"_;"title="Emperor_Tenji.html"_;"title="_distinct_act_of_''senso''_is_unrecognized_prior_to_Emperor_Tenji">_distinct_act_of_''senso''_is_unrecognized_prior_to_Emperor_Tenji;_and_all_sovereigns_except_Empress_Jitō">Jitō,_Emperor_Yōzei">Yōzei,_Emperor_Go-Toba">Go-Toba_

_was_the_82nd_emperor_of_Japan,_according_to_the_traditional_order_of_succession._His_reign_spanned_the_years_from_1183_through_1198.

This_12th-century_sovereign_was_named_after_Emperor_Toba,_and_''go-''_(後),_translates_literally_as_"later";_an_...

,_and_ Yōzei,_Emperor_Go-Toba.html"__"title="Emperor_Yōzei.html"_;"title="Empress_Jitō.html"_;"title="Emperor_Tenji.html"_;"title="_distinct_act_of_''senso''_is_unrecognized_prior_to_Emperor_Tenji">_distinct_act_of_''senso''_is_unrecognized_prior_to_Emperor_Tenji;_and_all_sovereigns_except_Empress_Jitō">Jitō,_Emperor_Yōzei">Yōzei,_Emperor_Go-Toba">Go-Tobaceremonies

A ceremony (, ) is a unified ritualistic event with a purpose, usually consisting of a number of artistic components, performed on a special occasion.

The word may be of Etruscan origin, via the Latin '' caerimonia''.

Church and civil (secula ...

(''sokui'') which are conventionally identified as "enthronement" and "coronation" (''Shōwa no tairei-shiki''); but this formal event would have been more accurately described as a public confirmation that his Imperial Majesty possesses the Japanese Imperial Regalia

The Imperial Regalia, also called Imperial Insignia (in German ''Reichskleinodien'', ''Reichsinsignien'' or ''Reichsschatz''), are regalia of the Holy Roman Emperor. The most important parts are the Crown, the Imperial orb, the Imperial s ...

, also called the Three Sacred Treasures, which have been handed down through the centuries.

Early reign

The first part of Hirohito's reign took place against a background of financial crisis and increasing military power within the government through both legal and extralegal means. The

The first part of Hirohito's reign took place against a background of financial crisis and increasing military power within the government through both legal and extralegal means. The Imperial Japanese Army

The was the official ground-based armed force of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945. It was controlled by the Imperial Japanese Army General Staff Office and the Ministry of the Army, both of which were nominally subordinate to the Emper ...

and Imperial Japanese Navy

The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN; Kyūjitai: Shinjitai: ' 'Navy of the Greater Japanese Empire', or ''Nippon Kaigun'', 'Japanese Navy') was the navy of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945, when it was dissolved following Japan's surrender ...

held veto

A veto is a legal power to unilaterally stop an official action. In the most typical case, a president or monarch vetoes a bill to stop it from becoming law. In many countries, veto powers are established in the country's constitution. Veto ...

power over the formation of cabinets since 1900. Between 1921 and 1944, there were 64 separate incidents of political violence.

Hirohito narrowly escaped assassination by a hand grenade

A grenade is an explosive weapon typically thrown by hand (also called hand grenade), but can also refer to a shell (explosive projectile) shot from the muzzle of a rifle (as a rifle grenade) or a grenade launcher. A modern hand grenade ...

thrown by a Korean independence

The Korean independence movement was a military and diplomatic campaign to achieve the independence of Korea from Japan. After the Japanese annexation of Korea in 1910, Korea's domestic resistance peaked in the March 1st Movement of 1919, whic ...

activist, Lee Bong-chang, in Tokyo on 9 January 1932, in the Sakuradamon Incident.

Another notable case was the assassination of moderate Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is ...

Inukai Tsuyoshi in 1932, marking the end of civilian control of the military. The February 26 incident, an attempted military coup, followed in February 1936. It was carried out by junior Army officers of the ''Kōdōha

The ''Kōdōha'' or was a political faction in the Imperial Japanese Army active in the 1920s and 1930s. The ''Kōdōha'' sought to establish a military government that promoted totalitarian, militaristic and aggressive expansionistic ideal ...

'' faction who had the sympathy of many high-ranking officers including Prince Chichibu (Yasuhito), one of the Emperor's brothers. This revolt was occasioned by a loss of political support by the militarist faction in Diet elections. The coup resulted in the murders of several high government and Army officials.

When Chief Aide-de-camp Shigeru Honjō informed him of the revolt, the Emperor immediately ordered that it be put down and referred to the officers as "rebels" (''bōto''). Shortly thereafter, he ordered Army Minister Yoshiyuki Kawashima

was a general in the Imperial Japanese Army and Army Minister in the 1930s.

Biography

Kawashima was a native of Ehime prefecture. He graduated from the 10th class of the Imperial Japanese Army Academy in 1898 (where one of his classmates was Sa ...

to suppress the rebellion within the hour. He asked for reports from Honjō every 30 minutes. The next day, when told by Honjō that the high command had made little progress in quashing the rebels, the Emperor told him "I Myself, will lead the Konoe Division and subdue them." The rebellion was suppressed following his orders on 29 February.

Second Sino-Japanese War

Starting from the

Starting from the Mukden Incident

The Mukden Incident, or Manchurian Incident, known in Chinese as the 9.18 Incident (九・一八), was a false flag event staged by Japanese military personnel as a pretext for the 1931 Japanese invasion of Manchuria.

On September 18, 1931, ...

in 1931 in which Japan staged a False flag operation and made a false accusation against Chinese dissidents as a pretext to invade Manchuria, Japan occupied Chinese territories and established puppet governments. Such aggression was recommended to Hirohito by his chiefs of staff and prime minister Fumimaro Konoe

Prince was a Japanese politician and prime minister. During his tenure, he presided over the Japanese invasion of China in 1937 and the breakdown in relations with the United States, which ultimately culminated in Japan's entry into World W ...

and Hirohito did not voice objection to the invasion of China. A diary by chamberlain Kuraji Ogura says that he was reluctant to start war against China in 1937 because they had underestimated China's military strength and Japan should be cautious in its strategy. In this regard, Ogura writes Hirohito said that "once you start (a war), it cannot easily be stopped in the middle ... What's important is when to end the war" and "one should be cautious in starting a war, but once begun, it should be carried out thoroughly." Nonetheless, his main concern seems to have been the possibility of an attack by the Soviet Union in the north. His questions to his chief of staff, Prince Kan'in Kotohito, and minister of the army, Hajime Sugiyama, were mostly about the time it could take to crush Chinese resistance.

According to Akira Fujiwara, Hirohito endorsed the policy of qualifying the invasion of China as an "incident" instead of a "war"; therefore, he did not issue any notice to observe international law in this conflict (unlike what his predecessors did in previous conflicts officially recognized by Japan as wars), and the Deputy Minister of the Japanese Army instructed the chief of staff of Japanese China Garrison Army on 5 August not to use the term "prisoners of war" for Chinese captives. This instruction led to the removal of the constraints of international law on the treatment of Chinese prisoners. The works of Yoshiaki Yoshimi and Seiya Matsuno show that the Emperor also authorized, by specific orders (''rinsanmei''), the use of chemical weapons against the Chinese. During the invasion of Wuhan, from August to October 1938, the Emperor authorized the use of toxic gas on 375 separate occasions, despite the resolution adopted by the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference th ...

on 14 May condemning Japanese use of toxic gas.

World War II

Preparations

In July 1939, the Emperor quarrelled with his brother, Prince Chichibu, over whether to support the Anti-Comintern Pact, and reprimanded the army minister, Seishirō Itagaki. But after the success of theWehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the ''Heer'' (army), the '' Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmacht''" replaced the previo ...

in Europe, the Emperor consented to the alliance. On 27 September 1940, ostensibly under Hirohito's leadership, Japan became a contracting partner of the Tripartite Pact

The Tripartite Pact, also known as the Berlin Pact, was an agreement between Germany, Italy, and Japan signed in Berlin on 27 September 1940 by, respectively, Joachim von Ribbentrop, Galeazzo Ciano and Saburō Kurusu. It was a defensive milit ...

with Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwee ...

and Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

forming the Axis Powers

The Axis powers, ; it, Potenze dell'Asse ; ja, 枢軸国 ''Sūjikukoku'', group=nb originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis, was a military coalition that initiated World War II and fought against the Allies. Its principal members were ...

.

The objectives to be obtained were clearly defined: a free hand to continue with the conquest of China and Southeast Asia, no increase in US or British military forces in the region, and cooperation by the West "in the acquisition of goods needed by our Empire."

On 5 September, Prime Minister Konoe informally submitted a draft of the decision to the Emperor, just one day in advance of the Imperial Conference at which it would be formally implemented. On this evening, the Emperor had a meeting with the chief of staff of the army, Sugiyama, chief of staff of the navy, Osami Nagano

was a Marshal Admiral of the Imperial Japanese Navy and one of the leaders of Japan's military during most of the Second World War. In April 1941, he became Chief of the Imperial Japanese Navy General Staff. In this capacity, he served as the ...

, and Prime Minister Konoe. The Emperor questioned Sugiyama about the chances of success of an open war with the Occident. As Sugiyama answered positively, the Emperor scolded him:

Chief of Naval General Staff Admiral Nagano, a former Navy Minister and vastly experienced, later told a trusted colleague, "I have never seen the Emperor reprimand us in such a manner, his face turning red and raising his voice."

Nevertheless, all speakers at the Imperial Conference were united in favor of war rather than diplomacy. Baron

Nevertheless, all speakers at the Imperial Conference were united in favor of war rather than diplomacy. Baron Yoshimichi Hara

Yoshimichi Hara (原嘉道) (February 18, 1867 – August 7, 1944) was a Japanese statesman and the president of the Japanese privy council during World War II, from June 1940 until his death.

Hara was always reluctant to use military force. In p ...

, President of the Imperial Council and the Emperor's representative, then questioned them closely, producing replies to the effect that war would be considered only as a last resort from some, and silence from others.

On 8 October, Sugiyama signed a 47-page report to the Emperor (sōjōan) outlining in minute detail plans for the advance into Southeast Asia. During the third week of October, Sugiyama gave the Emperor a 51-page document, "Materials in Reply to the Throne," about the operational outlook for the war.

As war preparations continued, Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is ...

Fumimaro Konoe

Prince was a Japanese politician and prime minister. During his tenure, he presided over the Japanese invasion of China in 1937 and the breakdown in relations with the United States, which ultimately culminated in Japan's entry into World W ...

found himself increasingly isolated, and he resigned on 16 October. He justified himself to his chief cabinet secretary, Kenji Tomita, by stating:

The army and the navy recommended the appointment of Prince Naruhiko Higashikuni

General was a Japanese imperial prince, a career officer in the Imperial Japanese Army and the 30th Prime Minister of Japan from 17 August 1945 to 9 October 1945, a period of 54 days. An uncle-in-law of Emperor Hirohito twice over, Prince Hi ...

, one of the Emperor's uncles, as prime minister. According to the Shōwa "Monologue", written after the war, the Emperor then said that if the war were to begin while a member of the imperial house was prime minister, the imperial house would have to carry the responsibility and he was opposed to this.

Instead, the Emperor chose the hard-line General Hideki Tōjō, who was known for his devotion to the imperial institution, and asked him to make a policy review of what had been sanctioned by the Imperial Conferences. On 2 November Tōjō, Sugiyama, and Nagano reported to the Emperor that the review of eleven points had been in vain. Emperor Hirohito gave his consent to the war and then asked: "Are you going to provide justification for the war?" The decision for war against the United States was presented for approval to Hirohito by General Tōjō, Naval Minister Admiral

Instead, the Emperor chose the hard-line General Hideki Tōjō, who was known for his devotion to the imperial institution, and asked him to make a policy review of what had been sanctioned by the Imperial Conferences. On 2 November Tōjō, Sugiyama, and Nagano reported to the Emperor that the review of eleven points had been in vain. Emperor Hirohito gave his consent to the war and then asked: "Are you going to provide justification for the war?" The decision for war against the United States was presented for approval to Hirohito by General Tōjō, Naval Minister Admiral Shigetarō Shimada

was an admiral in the Imperial Japanese Navy during World War II. He also served as Minister of the Navy. He was convicted of war crimes and sentenced to life imprisonment.

Early life and education

A native of Tokyo, Shimada graduated from ...

, and Japanese Foreign Minister Shigenori Tōgō.

On 3 November, Nagano explained in detail the plan of the attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service upon the United States against the naval base at Pearl Harbor in Honolulu, Territory of Hawaii ...

to the Emperor. On 5 November Emperor Hirohito approved in imperial conference the operations plan for a war against the Occident and had many meetings with the military and Tōjō until the end of the month. On 25 November Henry L. Stimson

Henry Lewis Stimson (September 21, 1867 – October 20, 1950) was an American statesman, lawyer, and Republican Party politician. Over his long career, he emerged as a leading figure in U.S. foreign policy by serving in both Republican and ...

, United States Secretary of War, noted in his diary that he had discussed with US President Franklin D. Roosevelt the severe likelihood that Japan was about to launch a surprise attack and that the question had been "how we should maneuver them he Japaneseinto the position of firing the first shot without allowing too much danger to ourselves."

On the following day, 26 November 1941, US Secretary of State Cordell Hull presented the Japanese ambassador with the Hull note

The Hull note, officially the Outline of Proposed Basis for Agreement Between the United States and Japan, was the final proposal delivered to the Empire of Japan by the United States of America before the attack on Pearl Harbor (December 7, 1 ...

, which as one of its conditions demanded the complete withdrawal of all Japanese troops from French Indochina

French Indochina (previously spelled as French Indo-China),; vi, Đông Dương thuộc Pháp, , lit. 'East Ocean under French Control; km, ឥណ្ឌូចិនបារាំង, ; th, อินโดจีนฝรั่งเศส, ...

and China. Japanese Prime Minister Hideki Tojo said to his cabinet, "This is an ultimatum." On 1 December an Imperial Conference sanctioned the "War against the United States, United Kingdom and the Kingdom of the Netherlands."

War: advance and retreat

On 8 December (7 December in Hawaii), 1941, in simultaneous attacks, Japanese forces struck at the Hong Kong Garrison, the US Fleet inPearl Harbor

Pearl Harbor is an American lagoon harbor on the island of Oahu, Hawaii, west of Honolulu. It was often visited by the Naval fleet of the United States, before it was acquired from the Hawaiian Kingdom by the U.S. with the signing of the ...

and in the Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

, and began the invasion of Malaya

The Malayan campaign, referred to by Japanese sources as the , was a military campaign fought by Allied and Axis forces in Malaya, from 8 December 1941 – 15 February 1942 during the Second World War. It was dominated by land battles between ...

.

With the nation fully committed to the war, the Emperor took a keen interest in military progress and sought to boost morale. According to Akira Yamada and Akira Fujiwara, the Emperor made major interventions in some military operations. For example, he pressed Sugiyama four times, on 13 and 21 January and 9 and 26 February, to increase troop strength and launch an attack on Bataan

Bataan (), officially the Province of Bataan ( fil, Lalawigan ng Bataan ), is a province in the Central Luzon region of the Philippines. Its capital is the city of Balanga while Mariveles is the largest town in the province. Occupying the enti ...

. On 9 February 19 March, and 29 May, the Emperor ordered the Army Chief of staff to examine the possibilities for an attack on Chungking in China, which led to Operation Gogo.

As the tide of war began to turn against Japan (around late 1942 and early 1943), the flow of information to the palace gradually began to bear less and less relation to reality, while others suggest that the Emperor worked closely with Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is ...

Hideki Tojo

Hideki Tojo (, ', December 30, 1884 – December 23, 1948) was a Japanese politician, general of the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA), and convicted war criminal who served as prime minister of Japan and president of the Imperial Rule Assistan ...

, continued to be well and accurately briefed by the military, and knew Japan's military position precisely right up to the point of surrender. The chief of staff of the General Affairs section of the Prime Minister's office, Shuichi Inada, remarked to Tōjō's private secretary, Sadao Akamatsu:

In the first six months of war, all the major engagements had been victories. Japanese advances were stopped in the summer of 1942 with the

In the first six months of war, all the major engagements had been victories. Japanese advances were stopped in the summer of 1942 with the battle of Midway

The Battle of Midway was a major naval battle in the Pacific Theater of World War II that took place on 4–7 June 1942, six months after Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor and one month after the Battle of the Coral Sea. The U.S. Navy under ...

and the landing of the American forces on Guadalcanal

Guadalcanal (; indigenous name: ''Isatabu'') is the principal island in Guadalcanal Province of Solomon Islands, located in the south-western Pacific, northeast of Australia. It is the largest island in the Solomon Islands by area, and the se ...

and Tulagi

Tulagi, less commonly known as Tulaghi, is a small island——in Solomon Islands, just off the south coast of Ngella Sule. The town of the same name on the island (pop. 1,750) was the capital of the British Solomon Islands Protectorate from 1 ...

in August. The emperor played an increasingly influential role in the war; in eleven major episodes he was deeply involved in supervising the actual conduct of war operations. Hirohito pressured the High Command to order an early attack on the Philippines in 1941–42, including the fortified Bataan

Bataan (), officially the Province of Bataan ( fil, Lalawigan ng Bataan ), is a province in the Central Luzon region of the Philippines. Its capital is the city of Balanga while Mariveles is the largest town in the province. Occupying the enti ...

peninsula. He secured the deployment of army air power in the Guadalcanal

Guadalcanal (; indigenous name: ''Isatabu'') is the principal island in Guadalcanal Province of Solomon Islands, located in the south-western Pacific, northeast of Australia. It is the largest island in the Solomon Islands by area, and the se ...

campaign. Following Japan's withdrawal from Guadalcanal he demanded a new offensive in New Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu: ''Niu Gini''; id, Papua, or , historically ) is the world's second-largest island with an area of . Located in Oceania in the southwestern Pacific Ocean, the island is separated from Australia by the wide Torres ...

, which was duly carried out but failed badly. Unhappy with the navy's conduct of the war, he criticized its withdrawal from the central Solomon Islands

Solomon Islands is an island country consisting of six major islands and over 900 smaller islands in Oceania, to the east of Papua New Guinea and north-west of Vanuatu. It has a land area of , and a population of approx. 700,000. Its capit ...

and demanded naval battles against the Americans for the losses they had inflicted in the Aleutians. The battles were disasters. Finally, it was at his insistence that plans were drafted for the recapture of Saipan

Saipan ( ch, Sa’ipan, cal, Seipél, formerly in es, Saipán, and in ja, 彩帆島, Saipan-tō) is the largest island of the Northern Mariana Islands, a Commonwealth (U.S. insular area), commonwealth of the United States in the western Pa ...

and, later, for an offensive in the Battle of Okinawa

The , codenamed Operation Iceberg, was a major battle of the Pacific War fought on the island of Okinawa by United States Army (USA) and United States Marine Corps (USMC) forces against the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA). The initial invasion of ...

. With the Army and Navy bitterly feuding, he settled disputes over the allocation of resources. He helped plan military offenses.

The media, under tight government control, repeatedly portrayed him as lifting the popular morale even as the Japanese cities came under heavy air attack in 1944–45 and food and housing shortages mounted. Japanese retreats and defeats were celebrated by the media as successes that portended "Certain Victory." Only gradually did it become apparent to the Japanese people that the situation was very grim due to growing shortages of food, medicine, and fuel as U.S submarines began wiping out Japanese shipping. Starting in mid 1944, American raids on the major cities of Japan made a mockery of the unending tales of victory. Later that year, with the downfall of Tojo's government, two other prime ministers were appointed to continue the war effort, Kuniaki Koiso and Kantarō Suzuki—each with the formal approval of the Emperor. Both were unsuccessful and Japan was nearing disaster.

Surrender

In early 1945, in the wake of the losses in the Battle of Leyte, Emperor Hirohito began a series of individual meetings with senior government officials to consider the progress of the war. All but ex-Prime Minister Fumimaro Konoe advised continuing the war. Konoe feared a communist revolution even more than defeat in war and urged a negotiated surrender. In February 1945, during the first private audience with the Emperor he had been allowed in three years, Konoe advised Hirohito to begin negotiations to end the war. According to Grand Chamberlain

In early 1945, in the wake of the losses in the Battle of Leyte, Emperor Hirohito began a series of individual meetings with senior government officials to consider the progress of the war. All but ex-Prime Minister Fumimaro Konoe advised continuing the war. Konoe feared a communist revolution even more than defeat in war and urged a negotiated surrender. In February 1945, during the first private audience with the Emperor he had been allowed in three years, Konoe advised Hirohito to begin negotiations to end the war. According to Grand Chamberlain Hisanori Fujita

was a Japanese admiral in the Imperial Japanese Navy, court official and Shinto priest. After retiring from active service, he served as Chief Priest of Meiji Shrine and the Grand Chamberlain to Emperor Shōwa during World War II.

Biography

...

, the Emperor, still looking for a ''tennozan'' (a great victory) in order to provide a stronger bargaining position, firmly rejected Konoe's recommendation.

With each passing week victory became less likely. In April, the Soviet Union issued notice that it would not renew its neutrality agreement. Japan's ally Germany surrendered in early May 1945. In June, the cabinet reassessed the war strategy, only to decide more firmly than ever on a fight to the last man. This strategy was officially affirmed at a brief Imperial Council meeting, at which, as was normal, the Emperor did not speak.

The following day, Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal Kōichi Kido prepared a draft document which summarized the hopeless military situation and proposed a negotiated settlement. Extremists in Japan were also calling for a death-before-dishonor mass suicide, modeled on the "47 Ronin

47, 47 or forty-seven may refer to:

*47 (number)

*47 BC

* AD 47

*1947

* 2047

* '47 (brand), an American clothing brand

* ''47'' (magazine), an American publication

* 47 (song), a song by Sidhu Moose Wala

*47, a song by New Found Glory from the al ...

" incident. By mid-June 1945, the cabinet had agreed to approach the Soviet Union to act as a mediator for a negotiated surrender but not before Japan's bargaining position had been improved by repulse of the anticipated Allied invasion of mainland Japan.

On 22 June, the Emperor met with his ministers saying, "I desire that concrete plans to end the war, unhampered by existing policy, be speedily studied and that efforts be made to implement them." The attempt to negotiate a peace via the Soviet Union came to nothing. There was always the threat that extremists would carry out a coup or foment other violence. On 26 July 1945, the Allies issued the Potsdam Declaration demanding unconditional surrender. The Japanese government council, the Big Six, considered that option and recommended to the Emperor that it be accepted only if one to four conditions were agreed upon, including a guarantee of the Emperor's continued position in Japanese society. The Emperor decided not to surrender.

That changed after the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the Soviet declaration of war. On 9 August, Emperor Hirohito told Kōichi Kido: "The Soviet Union has declared war and today began hostilities against us." On 10 August, the cabinet drafted an " Imperial Rescript ending the War" following the Emperor's indications that the declaration did not compromise any demand which prejudiced his prerogatives as a sovereign ruler.

On 12 August 1945, the Emperor informed the imperial family of his decision to surrender. One of his uncles, Prince Yasuhiko Asaka

General was the founder of a collateral branch of the Japanese imperial family and a general in the Imperial Japanese Army during the Japanese invasion of China and the Second World War. Son-in-law of Emperor Meiji and uncle by marriage o ...

, asked whether the war would be continued if the '' kokutai'' (national polity) could not be preserved. The Emperor simply replied "Of course." On 14 August the Suzuki government notified the Allies that it had accepted the Potsdam Declaration.

On 15 August, a recording of the Emperor's surrender speech ( ''"Gyokuon-hōsō"'', literally ''"broadcast in the Emperor's voice"'') was broadcast over the radio (the first time the Emperor was heard on the radio by the Japanese people) announcing Japan's acceptance of the Potsdam Declaration. During the historic broadcast the Emperor stated: "Moreover, the enemy has begun to employ a new and most cruel bomb, the power of which to do damage is, indeed, incalculable, taking the toll of many innocent lives. Should we continue to fight, not only would it result in an ultimate collapse and obliteration of the Japanese nation, but also it would lead to the total extinction of human civilization." The speech also noted that "the war situation has developed not necessarily to Japan's advantage" and ordered the Japanese to "endure the unendurable." The speech, using formal, archaic Japanese, was not readily understood by many commoners. According to historian Richard Storry

Richard is a male given name. It originates, via Old French, from Old Frankish and is a compound of the words descending from Proto-Germanic ''*rīk-'' 'ruler, leader, king' and ''*hardu-'' 'strong, brave, hardy', and it therefore means 'stron ...

in ''A History of Modern Japan'', the Emperor typically used "a form of language familiar only to the well-educated" and to the more traditional samurai

were the hereditary military nobility and officer caste of medieval and early-modern Japan from the late 12th century until their abolition in 1876. They were the well-paid retainers of the '' daimyo'' (the great feudal landholders). They ...

families.

A faction of the army opposed to the surrender attempted a coup d'état

A coup d'état (; French for 'stroke of state'), also known as a coup or overthrow, is a seizure and removal of a government and its powers. Typically, it is an illegal seizure of power by a political faction, politician, cult, rebel group, m ...

on the evening of 14 August, prior to the broadcast. They seized the Imperial Palace (the Kyūjō incident), but the physical recording of the emperor's speech was hidden and preserved overnight. The coup failed, and the speech was broadcast the next morning.

In his first ever press conference given in Tokyo in 1975, when he was asked what he thought of the bombing of Hiroshima, the Emperor answered: "It's very regrettable that nuclear bombs were dropped and I feel sorry for the citizens of Hiroshima but it couldn't be helped because that happened in wartime" (''shikata ga nai

, , is a Japanese language phrase meaning "it cannot be helped" or "nothing can be done about it". , is an alternative.

Cultural associations

The phrase has been used by many western writers to describe the ability of the Japanese people to mai ...

'', meaning "it cannot be helped").

After the Japanese surrender in August 1945, there was a large amount of pressure that came from both Allied countries and Japanese leftists that demanded the emperor step down and be indicted as a war criminal., pp. 125–126 The Australian government listed Hirohito as a war criminal, and intended to put him on trial. General Douglas MacArthur did not like the idea, as he thought that an ostensibly cooperating emperor would help establish a peaceful allied occupation regime in Japan. As a result, any possible evidence that would incriminate the emperor and his family were excluded from the International Military Tribunal for the Far East

The International Military Tribunal for the Far East (IMTFE), also known as the Tokyo Trial or the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal, was a military trial convened on April 29, 1946 to try leaders of the Empire of Japan for crimes against peace, conv ...

. MacArthur created a plan that separated the emperor from the militarists, retained the emperor as a constitutional monarch but only as a figurehead, and used the emperor to retain control over Japan and help achieve American postwar objectives in Japan.

Accountability for Japanese war crimes

The issue of Emperor Hirohito's war responsibility is contested. During the war, theAllies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

frequently depicted Hirohito to equate with Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

and Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until Fall of the Fascist re ...

as the three Axis dictators., edited by Peter B. Lane and Ronald E. Marcello, pp. 94–96 After the war, since the U.S. thought that the retention of the emperor would help establish a peaceful allied occupation regime in Japan, and help the U.S. achieve their postwar objectives, they depicted Hirohito as a "powerless figurehead" without any implication in wartime policies. This was the dominant postwar narrative until his death in 1989. After Hirohito's death, historians argued that Hirohito wielded more power than previously believed, and he was actively involved in the decision to launch the war as well as in other political and military decisions before. Over the years, as new evidence surfaced, historians were able to arrive at the conclusion that he was culpable for the war, and was reflecting on his wartime role. Some evidence shows that Hirohito had some involvement, but his power was limited by cabinet members, ministers and other people of the military oligarchy.

Evidence for wartime culpability

Some historians contend that Hirohito was directly responsible for the atrocities committed by the imperial forces in the Second Sino-Japanese War and in World War II. They argued that he and some members of the imperial family, such as his brother Prince Chichibu, his cousins the princes Takeda and Fushimi, and his uncles the princes Kan'in, Asaka, and Higashikuni, should have been tried for war crimes.Bix. In a study published in 1996, historian Mitsuyoshi Himeta claims that the Three Alls Policy (''Sankō Sakusen''), a Japanesescorched earth

A scorched-earth policy is a military strategy that aims to destroy anything that might be useful to the enemy. Any assets that could be used by the enemy may be targeted, which usually includes obvious weapons, transport vehicles, commun ...

policy adopted in China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, most populous country, with a Population of China, population exceeding 1.4 billion, slig ...

and sanctioned by Emperor Hirohito himself, was both directly and indirectly responsible for the deaths of "more than 2.7 million" Chinese civilians. His works and those of Akira Fujiwara about the details of the operation were commented by Herbert P. Bix in his ''Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan'', who wrote that the ''Sankō Sakusen'' far surpassed Nanking Massacre

The Nanjing Massacre (, ja, 南京大虐殺, Nankin Daigyakusatsu) or the Rape of Nanjing (formerly romanized as ''Nanking'') was the mass murder of Chinese civilians in Nanjing, the capital of the Republic of China, immediately after the ...

not only in terms of numbers, but in brutality as well as "These military operations caused death and suffering on a scale incomparably greater than the totally unplanned orgy of killing in Nanking, which later came to symbolize the war". While the Nanking Massacre was unplanned, Bix said "Hirohito knew of and approved annihilation campaigns in China that included burning villages thought to harbor guerrillas."

The debate over Hirohito's responsibility for war crimes concerns how much real control the Emperor had over the Japanese military during the two wars. Officially, the imperial constitution, adopted under Emperor Meiji

, also called or , was the 122nd emperor of Japan according to the traditional order of succession. Reigning from 13 February 1867 to his death, he was the first monarch of the Empire of Japan and presided over the Meiji era. He was the figur ...

, gave full power to the Emperor. Article 4 prescribed that, "The Emperor is the head of the Empire, combining in Himself the rights of sovereignty, and exercises them, according to the provisions of the present Constitution." Likewise, according to article 6, "The Emperor gives sanction to laws and orders them to be promulgated and executed," and article 11, "The Emperor has the supreme command of the Army and the Navy." The Emperor was thus the leader of the Imperial General Headquarters

The was part of the Supreme War Council and was established in 1893 to coordinate efforts between the Imperial Japanese Army and Imperial Japanese Navy during wartime. In terms of function, it was approximately equivalent to the United States ...

.

Poison gas weapons, such as phosgene

Phosgene is the organic chemical compound with the formula COCl2. It is a toxic, colorless gas; in low concentrations, its musty odor resembles that of freshly cut hay or grass. Phosgene is a valued and important industrial building block, esp ...

, were produced by Unit 731 and authorized by specific orders given by Hirohito himself, transmitted by the chief of staff of the army. For example, Hirohito authorized the use of toxic gas 375 times during the Battle of Wuhan

The Battle of Wuhan (武漢之戰), popularly known to the Chinese as the Defense of Wuhan, and to the Japanese as the Capture of Wuhan, was a large-scale battle of the Second Sino-Japanese War. Engagements took place across vast areas of Anhui ...

from August to October 1938.

Historians such as Herbert Bix

Herbert P. Bix (born 1938) is an American historian. He wrote ''Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan'', an account of the Japanese Emperor and the events which shaped modern Japanese imperialism, which won the Pulitzer Prize for General Nonfict ...

, Akira Fujiwara

was a Japanese historian. His academic speciality was modern Japanese history and he was a professor emeritus at Hitotsubashi University. In 1980 he became a member of the Science Council of Japan and was a former chairman of the Historical Scienc ...

, Peter Wetzler, and Akira Yamada

was a Japanese scholar and philosopher of the West European Medieval philosophy. Member of the Japan Academy since 1998.

Yamada graduated from the Kyoto Imperial University, Philosophy section of the Department of Literature in 1944.

* 1951, In ...

assert that post-war arguments favoring the view that Hirohito was a mere figurehead overlook the importance of numerous "behind the chrysanthemum curtain" meetings where the real decisions were made between the Emperor, his chiefs of staff, and the cabinet. Using primary sources and the monumental work of Shirō Hara as a basis, Fujiwara and Wetzler have produced evidence suggesting that the Emperor worked through intermediaries to exercise a great deal of control over the military and was neither bellicose nor a pacifist but an opportunist who governed in a pluralistic decision-making process. American historian Herbert P. Bix goes so far as to argue that Emperor Hirohito might have been the prime mover behind most of Japan's military aggression during the Shōwa Era.

The view promoted by the Imperial Palace and American occupation forces immediately after World War II portrayed Emperor Hirohito as a purely ceremonial figure who behaved strictly according to protocol while remaining at a distance from the decision-making processes. This view was endorsed by Prime Minister Noboru Takeshita in a speech on the day of Hirohito's death in which Takeshita asserted that the war "had broken out against irohito'swishes." Takeshita's statement provoked outrage in nations in East Asia and Commonwealth nations such as the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. According to historian Fujiwara, "The thesis that the Emperor, as an organ of responsibility, could not reverse cabinet decision is a myth

Myth is a folklore genre consisting of narratives that play a fundamental role in a society, such as foundational tales or origin myths. Since "myth" is widely used to imply that a story is not objectively true, the identification of a narrat ...

fabricated after the war."

According to Yinan He, associate professor of international relations at Lehigh University, in the aftermath of the war, conservative Japanese elites created self-whitewashing, self-glorifying national myths that minimized the scope of Japan's war responsibility, which included presenting the emperor as a peace-seeking diplomat and a narrative that separated him from the militarists, whom they described as people who hijacked the Japanese government and led the country into war, shifting the responsibility from the ruling class to only a few military leaders. This narrative also narrowly focuses on the U.S.–Japan conflict, completely ignores the wars Japan waged in Asia, and disregards the atrocities committed by Japanese troops during the war. Japanese elites created the narrative in an attempt to avoid tarnishing the national image and regain the international acceptance of the country.

argues that post-war Japanese public opinion supporting protection of the Emperor was influenced by U.S. propaganda promoting the view that the Emperor together with the Japanese people had been fooled by the military.

In the years immediately after Hirohito's death, scholars who spoke out against the emperor were threatened and attacked by right-wing extremists. Susan Chira reported, "Scholars who have spoken out against the late Emperor have received threatening phone calls from Japan's extremist right wing." One example of actual violence occurred in 1990 when the mayor of Nagasaki, Hitoshi Motoshima

was a Japanese politician. He served four terms as mayor of Nagasaki from 1979 to 1995. He publicly made controversial statements about the responsibility of Japan and its then-reigning Emperor for World War II, and survived a retaliatory as ...

, was shot and critically wounded by a member of the ultranationalist group, Seikijuku. A year before, in 1989, Motoshima had broken what was characterized as "one of apan'smost sensitive taboos" by asserting that Emperor Hirohito bore responsibility for World War II.

Regarding Hirohito's exemption from trial before the International Military Tribunal of the Far East

The International Military Tribunal for the Far East (IMTFE), also known as the Tokyo Trial or the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal, was a military trial convened on April 29, 1946 to try leaders of the Empire of Japan for crimes against peace, conve ...

, opinions were not unanimous. Sir William Webb, the president of the tribunal, declared: "This immunity of the Emperor is contrasted with the part he played in launching the war in the Pacific, is, I think, a matter which the tribunal should take into consideration in imposing the sentences." Likewise, the French judge, Henri Bernard, wrote about Hirohito's accountability that the declaration of war by Japan "had a principal author who escaped all prosecution and of whom in any case the present defendants could only be considered accomplices."

An account from the Vice Interior Minister in 1941, Michio Yuzawa, asserts that Hirohito was "at ease" with the attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service upon the United States against the naval base at Pearl Harbor in Honolulu, Territory of Hawaii ...

"once he had made a decision."

In Japan, debate over the Emperor's responsibility was taboo while he was alive. After his death, however, debate began to surface over the extent of his involvement and thus his culpability. Since his death in 1989, historians have discovered evidence that prove Hirohito's culpability for the war, and that he was not a passive figurehead manipulated by those around him.

Michiji Tajima's notes in 1952

According to notebooks by Michiji Tajima, a top Imperial Household Agency official who took office after the war, Emperor Hirohito privately expressed regret about the atrocities that were committed by Japanese troops during theNanjing Massacre

The Nanjing Massacre (, ja, 南京大虐殺, Nankin Daigyakusatsu) or the Rape of Nanjing (formerly romanized as ''Nanking'') was the mass murder of Chinese civilians in Nanjing, the capital of the Republic of China, immediately after the ...

. In addition to feeling remorseful about his own role in the war, he "fell short by allowing radical elements of the military to drive the conduct of the war."

Vice Interior Minister Yuzawa's account on Hirohito's role in Pearl Harbor raid

In late July 2018, the bookseller Takeo Hatano, an acquaintance of the descendants ofMichio Yuzawa

was a bureaucrat and cabinet minister in early Shōwa period Japan.

Biography

Yuzawa was born in Kamitsuga District, Tochigi in what is now part of the city of Kanuma as the son of a '' kannushi'' ( Shinto priest)]. After his graduation in ...

(Japanese Vice Interior Minister in 1941), released to Japan's ''Yomiuri Shimbun

The (lit. ''Reading-selling Newspaper'' or ''Selling by Reading Newspaper'') is a Japanese newspaper published in Tokyo, Osaka, Fukuoka, and other major Japanese cities. It is one of the five major newspapers in Japan; the other four are ...

'' newspaper a memo by Yuzawa that Hatano had kept for nine years since he received it from Yuzawa's family. The bookseller said: "It took me nine years to come forward, as I was afraid of a backlash. But now I hope the memo would help us figure out what really happened during the war, in which 3.1 million people were killed."

Takahisa Furukawa, expert on wartime history from Nihon University, confirmed the authenticity of the memo, calling it "the first look at the thinking of Emperor Hirohito and Prime Minister Hideki Tojo

Hideki Tojo (, ', December 30, 1884 – December 23, 1948) was a Japanese politician, general of the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA), and convicted war criminal who served as prime minister of Japan and president of the Imperial Rule Assistan ...

on the eve of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor."

In this document, Yuzawa details a conversation he had with Tojo a few hours before the attack. The Vice Minister quotes Tojo saying:

Historian Furukawa concluded from Yuzawa's memo:

Shinobu Kobayashi's diary

Shinobu Kobayashi was the Emperor's chamberlain from April 1974 until June 2000. Kobayashi kept a diary with near-daily remarks of Hirohito for 26 years. It was made public on Wednesday 22 August 2018. According to Takahisa Furukawa, a professor of modern Japanese history at Nihon University, the diary reveals that the emperor “gravely took responsibility for the war for a long time, and as he got older, that feeling became stronger.” Jennifer Lind, associate professor of government atDartmouth College

Dartmouth College (; ) is a private research university in Hanover, New Hampshire. Established in 1769 by Eleazar Wheelock, it is one of the nine colonial colleges chartered before the American Revolution. Although founded to educate Native ...

and a specialist in Japanese war memory said:

An entry dated 27 May 1980 said the Emperor wanted to express his regret about the Sino-Japanese war to former Chinese Premier Hua Guofeng

Hua Guofeng (; born Su Zhu; 16 February 1921 – 20 August 2008), alternatively spelled as Hua Kuo-feng, was a Chinese politician who served as Chairman of the Chinese Communist Party and Premier of the People's Republic of China. The desig ...

who visited at the time, but was stopped by senior members of the Imperial Household Agency

The (IHA) is an agency of the government of Japan in charge of state matters concerning the Imperial Family, and also the keeping of the Privy Seal and State Seal of Japan. From around the 8th century AD, up until the Second World War, it ...

due to fear of backlash from far right groups.

An entry dated 7 April 1987 said the Emperor was haunted by discussions of his wartime responsibility and, as a result, was losing his will to live.

Hirohito's preparations for war described in Saburō Hyakutake's diary

In September 2021, 25 diaries, pocket notebooks and memos by Saburō Hyakutake (Emperor Hirohito's Grand Chamberlain from 1936 to 1944) deposited by his relatives to the library of the University of Tokyo's graduate schools for law and politics became available to the public. Hyakutake's diary quotes some Hirohito's ministers and advisers worried that the Emperor was getting ahead of them in terms of battle preparations. Thus, Hyakutake quotes Tsuneo Matsudaira, the Imperial Household Minister, saying: Likewise, Koichi Kido, Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal, is quoted as saying: Seiichi Chadani, professor of modern Japanese history with Shigakukan University who has studied Hirohito's actions before and during the war said on the discovery of Hyakutake's diary:Documents that suggest limited wartime responsibility

The declassified January 1989 British government assessment of Hirohito describes him as "too weak to alter the course of events" and Hirohito was "powerless" and comparisons with Hitler are "ridiculously wide off the mark." Hirohito's power was limited by ministers and the military and if he asserted his views too much he would have been replaced by another member of the royal family.Indian

Indian or Indians may refer to:

Peoples South Asia

* Indian people, people of Indian nationality, or people who have an Indian ancestor

** Non-resident Indian, a citizen of India who has temporarily emigrated to another country

* South Asia ...

jurist

A jurist is a person with expert knowledge of law; someone who analyses and comments on law. This person is usually a specialist legal scholar, mostly (but not always) with a formal qualification in law and often a legal practitioner. In the U ...

Radhabinod Pal opposed the International Military Tribunal and made a 1,235-page judgment. He found the entire prosecution case to be weak regarding the conspiracy to commit an act of aggressive war with brutalization and subjugation of conquered nations. Pal said there is "no evidence, testimonial or circumstantial, concomitant, prospectant, restrospectant, that would in any way lead to the inference that the government in any way permitted the commission of such offenses"."The Tokyo Judgment and the Rape of Nanking", by Timothy Brook, ''The Journal of Asian Studies'', August 2001. He added that conspiracy to wage aggressive war was not illegal in 1937, or at any point since. Pal supported the acquittal of all of the defendants. He considered the Japanese military operations as justified, because Chiang Kai-shek supported the boycott of trade operations by the Western Powers, particularly the United States boycott of oil exports to Japan. Pal argued the attacks on neighboring territories were justified to protect the Japanese Empire from an aggressive environment, especially the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

. He considered that to be self-defense operations which are not criminal. Pal said "the real culprits are not before us" and concluded that "only a lost war is an international crime".

=The Emperor's own statements

= ;8 September 1975 TV interview with NBC, USA : Reporter: "How far has your Majesty been involved in Japan's decision to end the war in 1945? What was the motivation for your launch?" : Emperor: "Originally, this should be done by the Cabinet. I heard the results, but at the last meeting I asked for a decision. I decided to end the war on my own. (...) I thought that the continuation of the war would only bring more misery to the people." ;Interview with ''Newsweek

''Newsweek'' is an American weekly online news magazine co-owned 50 percent each by Dev Pragad, its president and CEO, and Johnathan Davis (businessman), Johnathan Davis, who has no operational role at ''Newsweek''. Founded as a weekly print m ...

'', USA, 20 September 1975

: Reporter: "(Abbreviation) How do you answer those who claim that your Majesty was also involved in the decision-making process that led Japan to start the war?"

: Emperor: "(Omission) At the start of the war, a cabinet decision was made, and I could not reverse that decision. We believe this is consistent with the provisions of the Imperial Constitution."

;22 September 1975 – Press conference with Foreign Correspondents

: Reporter: "How long before the attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service upon the United States against the naval base at Pearl Harbor in Honolulu, Territory of Hawaii ...

did your Majesty know about the attack plan? And did you approve the plan?"

: Emperor: "It is true that I had received information on military operations in advance. However, I only received those reports after the military commanders made detailed decisions. Regarding issues of political character and military command, I believe that I acted in accordance with the provisions of the Constitution."