High treason in the United Kingdom on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Under the law of the

First, it was high treason to "compass or imagine the death of our Lord the King, of our Lady his Queen, or of their eldest son and heir." The terms "compass or imagine" indicate the premeditation of a murder; it would not be high treason to accidentally kill the sovereign or any other member of the Royal Family (though someone could be charged with

First, it was high treason to "compass or imagine the death of our Lord the King, of our Lady his Queen, or of their eldest son and heir." The terms "compass or imagine" indicate the premeditation of a murder; it would not be high treason to accidentally kill the sovereign or any other member of the Royal Family (though someone could be charged with

at legislation.org.uk (retrieved 30 March 2015) which amended the line of succession to the throne to give women the same right to succeed to the throne as their brothers. In consequence of this, the Treason Act 1351 was amended in two ways. Whereas it had been treason to encompass the death of the monarch's eldest ''son'' and heir, this was amended to cover an heir of either sex. It had also been treason to "violate" the wife of the monarch's eldest son, but the 2013 Act restricted this to cases where the eldest son is also the heir to the throne.

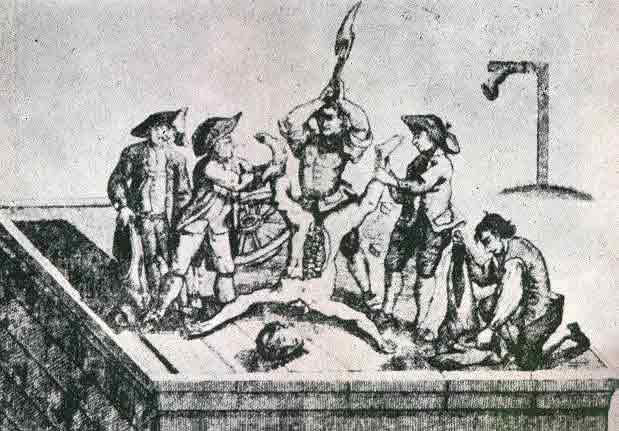

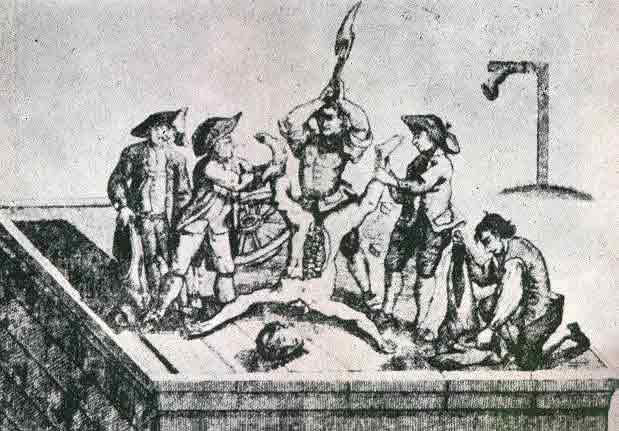

The condemned could not walk or be carried to the place of execution; the sentence required that they were to be drawn: they might be dragged along the ground, but were normally tied onto a hurdle which was drawn to the place of execution by a horse. A man would then be

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and ...

, high treason is the crime of disloyalty to the Crown

The Crown is the state in all its aspects within the jurisprudence of the Commonwealth realms and their subdivisions (such as the Crown Dependencies, overseas territories, provinces, or states). Legally ill-defined, the term has differ ...

. Offences constituting high treason include plotting the murder of the sovereign; committing adultery with the sovereign's consort, with the sovereign's eldest unmarried daughter, or with the wife of the heir to the throne; levying war against the sovereign and adhering to the sovereign's enemies, giving them aid or comfort; and attempting to undermine the lawfully established line of succession. Several other crimes have historically been categorised as high treason, including counterfeit

To counterfeit means to imitate something authentic, with the intent to steal, destroy, or replace the original, for use in illegal transactions, or otherwise to deceive individuals into believing that the fake is of equal or greater value tha ...

ing money and being a Catholic priest. Jesuits, etc. Act 1584

High treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

was generally distinguished from petty treason, a treason committed against a subject of the sovereign, the scope of which was limited by statute to the murder of a legal superior. Petty treason comprised the murder of a master by his servant, of a husband by his wife, or of a bishop by a clergyman. Petty treason ceased to be a distinct offence from murder in 1828, and consequently high treason is today often referred to simply as treason.

Considered to be the most serious of offences (more than murder or other felonies), high treason was often met with extraordinary punishment, because it threatened the safety of the state. Hanging, drawing and quartering

To be hanged, drawn and quartered became a statutory penalty for men convicted of high treason in the Kingdom of England from 1352 under King Edward III (1327–1377), although similar rituals are recorded during the reign of King Henry III ...

was the usual punishment until the 19th century. The last treason trial was that of William Joyce, " Lord Haw-Haw", who was executed by hanging in 1946.

Since the Crime and Disorder Act 1998

The Crime and Disorder Act 1998 (c.37) is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. The Act was published on 2 December 1997 and received Royal Assent in July 1998. Its key areas were the introduction of Anti-Social Behaviour Orders, Sex ...

became law, the maximum sentence for treason in the UK has been life imprisonment

Life imprisonment is any sentence of imprisonment for a crime under which convicted people are to remain in prison for the rest of their natural lives or indefinitely until pardoned, paroled, or otherwise commuted to a fixed term. Crimes fo ...

.

Offences

High treason today consists of: * Treason Act 1351 (as amended – last amended by theSuccession to the Crown Act 2013

The Succession to the Crown Act 2013 (c. 20) is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that altered the laws of succession to the British throne in accordance with the 2011 Perth Agreement. The Act replaced male-preference primogenit ...

):

**compassing the death of the sovereign, or of the king's wife (but not a ruling queen's husband), or the sovereign's eldest child and heir

**violating the king's wife, or the sovereign's eldest unmarried daughter, or the sovereign's eldest son's wife (only if the eldest son is also heir to the throne)

**levying war against the sovereign in the realm

**adhering to the sovereign's enemies, giving them aid and comfort, in the realm or elsewhere

**killing the King's Chancellor

Chancellor ( la, cancellarius) is a title of various official positions in the governments of many nations. The original chancellors were the of Roman courts of justice—ushers, who sat at the or lattice work screens of a basilica or law cou ...

, Treasurer

A treasurer is the person responsible for running the treasury of an organization. The significant core functions of a corporate treasurer include cash and liquidity management, risk management, and corporate finance.

Government

The treasury ...

(an office long in commission) or Justices

* Treason Act 1702

The Treason Act 1702 (1 Anne Stat. 2 c. 21Some volumes cite it as c.17) is an Act of the Parliament of England, passed to enforce the line of succession to the English throne (today the British throne), previously established by the Bill of Righ ...

and Treason Act (Ireland) 1703:

**attempting to hinder the succession to the throne

In inheritance, a hereditary successor is a person who inherits an indivisible title or office after the death of the previous title holder. The hereditary line of succession may be limited to heirs of the body, or may pass also to collateral l ...

under the Bill of Rights 1689 and the Act of Settlement 1701

The Act of Settlement is an Act of the Parliament of England that settled the succession to the English and Irish crowns to only Protestants, which passed in 1701. More specifically, anyone who became a Roman Catholic, or who married one, be ...

* Treason Act 1708:

**killing the Lords of Session or Lords of Justiciary in Scotland

**(in Scots law

Scots law () is the legal system of Scotland. It is a hybrid or mixed legal system containing civil law and common law elements, that traces its roots to a number of different historical sources. Together with English law and Northern Ireland ...

only) counterfeiting the Great Seal of Scotland

''See the English History section below for detail about the offences created by the 1351 Act.''

Northern Ireland

In addition to the Acts of 1351 and 1703, two additional Acts passed by the oldParliament of Ireland

The Parliament of Ireland ( ga, Parlaimint na hÉireann) was the legislature of the Lordship of Ireland, and later the Kingdom of Ireland, from 1297 until 1800. It was modelled on the Parliament of England and from 1537 comprised two ch ...

apply to Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ga, Tuaisceart Éireann ; sco, label=Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots, Norlin Airlann) is a part of the United Kingdom, situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, that is #Descriptions, variously described as ...

alone. The following is also treason:

* Treason Act (Ireland) 1537:

**attempting bodily harm to the king, queen, or their heirs apparent

An heir apparent, often shortened to heir, is a person who is first in an order of succession and cannot be displaced from inheriting by the birth of another person; a person who is first in the order of succession but can be displaced by the b ...

**attempting to deprive them of their title

**publishing that the sovereign is a heretic

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, in particular the accepted beliefs of a church or religious organization. The term is usually used in reference to violations of important relig ...

, tyrant, infidel or usurper of the Crown

**rebelliously withholding from the sovereign his fortresses, ships, artillery etc.

* Crown of Ireland Act 1542

The Crown of Ireland Act 1542 is an Act passed by the Parliament of Ireland (33 Hen. 8 c. 1) on 18 June 1542, which created the title of King of Ireland for King Henry VIII of England and his successors, who previously ruled the island as Lor ...

:

**doing anything to endanger the sovereign's person

**doing anything which might disturb or interrupt the sovereign's possession of the Crown

Although the Act of Supremacy (Ireland) 1560 is still in force, it is no longer treason to contravene it.)

Treason felony

In addition to the crime of treason, the Treason Felony Act 1848 (still in force today) created a new offence known as ''treason felony'', with a maximum sentence of life imprisonment instead ofdeath

Death is the irreversible cessation of all biological functions that sustain an organism. For organisms with a brain, death can also be defined as the irreversible cessation of functioning of the whole brain, including brainstem, and brain ...

(but today, due to the abolition of the death penalty, the maximum penalty both for high treason and treason felony is the same—life imprisonment). Under the traditional categorisation of offences into treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

, felonies

A felony is traditionally considered a crime of high seriousness, whereas a misdemeanor is regarded as less serious. The term "felony" originated from English common law (from the French medieval word "félonie") to describe an offense that resu ...

, and misdemeanour

A misdemeanor (American English, spelled misdemeanour elsewhere) is any "lesser" criminal act in some common law legal systems. Misdemeanors are generally punished less severely than more serious felonies, but theoretically more so than admi ...

s, treason felony was merely another form of felony. Several categories of treason which had been introduced by the Sedition Act 1661 were reduced to felonies. While the common law offences of misprision

Misprision (from fro, mesprendre, modern french: se méprendre, "to misunderstand") in English law describes certain kinds of offence. Writers on criminal law usually divide misprision into two kinds: negative and positive.

It survives in the la ...

and compounding

In the field of pharmacy, compounding (performed in compounding pharmacies) is preparation of a custom formulation of a medication to fit a unique need of a patient that cannot be met with commercially available products. This may be done for me ...

were abolished in respect of felonies (including treason felony) by the Criminal Law Act 1967, which abolished the distinction between misdemeanour and felony, misprision of treason

Misprision of treason is an offence found in many common law jurisdictions around the world, having been inherited from English law. It is committed by someone who knows a treason is being or is about to be committed but does not report it to a p ...

and compounding treason

Compounding treason is an offence under the common law of England. It is committed by anyone who agrees for consideration to abstain from prosecuting the offender who has committed treason.

It is still an offence in England and Wales, and in Nort ...

are still offences under the common law.

It is treason felony to "compass, imagine, invent, devise, or intend":

* to deprive the sovereign of the Crown,

* to levy war against the sovereign "in order by force or constraint to compel her to change her measures or counsels, or in order to put any force or constraint upon or in order to intimidate or overawe both Houses or either House of Parliament", or

* to "move or stir" any foreigner to invade the United Kingdom or any other country belonging to the sovereign.

History: England and Wales

In England, there was no clearcommon law

In law, common law (also known as judicial precedent, judge-made law, or case law) is the body of law created by judges and similar quasi-judicial tribunals by virtue of being stated in written opinions."The common law is not a brooding omniprese ...

definition of treason; it was for the king and his judges to determine if an offence constituted treason. Thus, the process became open to abuse, and decisions were often arbitrary. For instance, during the reign of Edward III

Edward III (13 November 1312 – 21 June 1377), also known as Edward of Windsor before his accession, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from January 1327 until his death in 1377. He is noted for his military success and for restoring r ...

, a knight was convicted of treason because he assaulted one of the king's subjects and held him for a ransom of £90. It was only in 1351 that Parliament passed legislation on the subject of treason. Under the Treason Act 1351, or "Statute of Treasons", which distinguished between high and petty treason, several distinct offences constitute high treason; most of them continue to do so, while those relating to forgery

Forgery is a white-collar crime that generally refers to the false making or material alteration of a legal instrument with the specific intent to defraud anyone (other than themself). Tampering with a certain legal instrument may be forb ...

have been relegated to ordinary offences.

First, it was high treason to "compass or imagine the death of our Lord the King, of our Lady his Queen, or of their eldest son and heir." The terms "compass or imagine" indicate the premeditation of a murder; it would not be high treason to accidentally kill the sovereign or any other member of the Royal Family (though someone could be charged with

First, it was high treason to "compass or imagine the death of our Lord the King, of our Lady his Queen, or of their eldest son and heir." The terms "compass or imagine" indicate the premeditation of a murder; it would not be high treason to accidentally kill the sovereign or any other member of the Royal Family (though someone could be charged with manslaughter

Manslaughter is a common law legal term for homicide considered by law as less culpable than murder. The distinction between murder and manslaughter is sometimes said to have first been made by the ancient Athenian lawmaker Draco in the 7th ce ...

or negligent homicide). However it has also been held to include rebelling against or trying to overthrow the monarch, as experience has shown that this normally involves the monarch's death. The terms of this provision have been held to include both male and female sovereigns, but only the spouses of male Sovereigns. It is not sufficient to merely allege that an individual is guilty of high treason because of his thoughts or imaginations; there must be an overt act indicating the plot.

A second form of high treason defined by the Treason Act 1351 was having sexual intercourse

Sexual intercourse (or coitus or copulation) is a sexual activity typically involving the insertion and thrusting of the penis into the vagina for sexual pleasure or reproduction.Sexual intercourse most commonly means penile–vaginal pene ...

with "the King's companion, or the King's eldest daughter unmarried, or the wife of the King's eldest son and heir." If the intercourse is not consensual, only the rapist is liable, but if it is consensual, then both parties are liable. Anne Boleyn

Anne Boleyn (; 1501 or 1507 – 19 May 1536) was Queen of England from 1533 to 1536, as the second wife of King Henry VIII. The circumstances of her marriage and of her execution by beheading for treason and other charges made her a key f ...

and Catherine Howard

Catherine Howard ( – 13 February 1542), also spelled Katheryn Howard, was Queen of England from 1540 until 1542 as the fifth wife of Henry VIII. She was the daughter of Lord Edmund Howard and Joyce Culpeper, a cousin to Anne Boleyn (the se ...

, wives of Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is best known for his six marriages, and for his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disa ...

, were found guilty of treason for this reason. The jurist Sir William Blackstone

Sir William Blackstone (10 July 1723 – 14 February 1780) was an English jurist, judge and Tory politician of the eighteenth century. He is most noted for writing the ''Commentaries on the Laws of England''. Born into a middle-class family in ...

writes that "the plain intention of this law is to guard the Blood Royal from any suspicion of bastardy, whereby the succession to the Crown might be rendered dubious." Thus, only women are covered in the statute; it is not, for example, high treason to rape a Queen-Regnant's husband. Similarly, it is not high treason to rape a widow of the sovereign or of the heir-apparent.

In 1994, the book ''Princess in Love'' by Anna Pasternak, for which James Hewitt

James Lifford Hewitt (born 30 April 1958) is a British former cavalry officer in the British Army. He came to public attention in the mid-1990s after he disclosed an affair with Diana, Princess of Wales, while she was still married to then-Pri ...

was a major source, alleged that Hewitt had a five-year affair with Diana, Princess of Wales

Diana, Princess of Wales (born Diana Frances Spencer; 1 July 1961 – 31 August 1997) was a member of the British royal family. She was the first wife of King Charles III (then Prince of Wales) and mother of Princes William and Harry. Her ac ...

from 1986 to 1991. Diana confirmed the affair in her 1995 ''Panorama'' interview. As she was then the wife of the Prince of Wales

Prince of Wales ( cy, Tywysog Cymru, ; la, Princeps Cambriae/Walliae) is a title traditionally given to the heir apparent to the English and later British throne. Prior to the conquest by Edward I in the 13th century, it was used by the rule ...

, heir to the throne, this fitted the definition of high treason, and a national newspaper briefly attempted to have Hewitt prosecuted for what was then still a capital offence.

It is high treason "if a man do levy war against our Lord the King in his realm" or "if a man be adherent to the King's enemies in his realm, giving to them aid and comfort in the realm or elsewhere." Conspiracy to levy war or aid the sovereign's enemies do not amount to this kind of treason, though it may be encompassing the Sovereign's death. In modern times only these kinds of treason have actually been prosecuted (during the World Wars

A world war is an international conflict which involves all or most of the world's major powers. Conventionally, the term is reserved for two major international conflicts that occurred during the first half of the 20th century, World WarI (1914 ...

and the Easter Rising

The Easter Rising ( ga, Éirí Amach na Cásca), also known as the Easter Rebellion, was an armed insurrection in Ireland during Easter Week in April 1916. The Rising was launched by Irish republicans against British rule in Ireland with t ...

).

The Treason Act 1351 made it high treason to "slay the Chancellor

Chancellor ( la, cancellarius) is a title of various official positions in the governments of many nations. The original chancellors were the of Roman courts of justice—ushers, who sat at the or lattice work screens of a basilica or law cou ...

, Treasurer

A treasurer is the person responsible for running the treasury of an organization. The significant core functions of a corporate treasurer include cash and liquidity management, risk management, and corporate finance.

Government

The treasury ...

, or the King's justices of the one bench or the other, justices in eyre, or justices of assize

The courts of assize, or assizes (), were periodic courts held around England and Wales until 1972, when together with the quarter sessions they were abolished by the Courts Act 1971 and replaced by a single permanent Crown Court. The assizes e ...

, and all other justices assigned to hear and determine, being in their places doing their offices."

The last types of high treason defined by the Treason Act 1351 were the forgery of the Great Seal or Privy Seal

A privy seal refers to the personal seal of a reigning monarch, used for the purpose of authenticating official documents of a much more personal nature. This is in contrast with that of a great seal, which is used for documents of greater impor ...

, the counterfeiting

To counterfeit means to imitate something authentic, with the intent to steal, destroy, or replace the original, for use in illegal transactions, or otherwise to deceive individuals into believing that the fake is of equal or greater value tha ...

of English (later British) money and the importing of money known to be counterfeit. These offences, however, were reduced to felonies

A felony is traditionally considered a crime of high seriousness, whereas a misdemeanor is regarded as less serious. The term "felony" originated from English common law (from the French medieval word "félonie") to describe an offense that resu ...

rather than high treasons in 1861 and 1832 respectively.

Finally, the Treason Act 1351 specified that the listing of offences was meant to be exhaustive. Only Parliament, not the courts, could add to the list. It provided that if "other like cases of treason may happen in time to come, which cannot be thought of nor declared at present", the court may refer the matter to the King and Parliament, which could then determine the matter by passage of an Act. ''(See constructive treason Constructive treason is the judicial extension of the statutory definition of the crime of treason. For example, the English Treason Act 1351 declares it to be treason "When a Man doth compass or imagine the Death of our Lord the King". This was su ...

.)''

After the passage of the Treason Act 1351, several other offences were deemed to comprise high treason by Act of Parliament. Parliament seemed especially unrestrained during the reign of Edward III's successor, Richard II

Richard II (6 January 1367 – ), also known as Richard of Bordeaux, was King of England from 1377 until he was deposed in 1399. He was the son of Edward the Black Prince, Prince of Wales, and Joan, Countess of Kent. Richard's father ...

. Numerous new offences—including intending to kill the Sovereign (even without an overt act demonstrating such intent) and killing an ambassador—were declared treasonable. Richard II, however, was deposed; his successor, Henry IV, rescinded the legislation and restored the standard of Edward III.

In 1495 Poynings' Law extended English law to cover Ireland.

From the reign of Henry IV onwards, several new offences were made treasons; most legislation on the subject was passed during the reign of Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is best known for his six marriages, and for his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disa ...

. It became high treason to deface money; to escape from prison whilst detained for committing treason, or to aid in an escape of a person detained for treason; to commit arson

Arson is the crime of willfully and deliberately setting fire to or charring property. Although the act of arson typically involves buildings, the term can also refer to the intentional burning of other things, such as motor vehicles, wate ...

to extort money; to refer to the Sovereign offensively in public writing; to counterfeit the Sovereign's sign manual

The royal sign-manual is the signature of the sovereign, by the affixing of which the monarch expresses his or her pleasure either by order, commission, or warrant. A sign-manual warrant may be either an executive act (for example, an appointmen ...

, signet

Signet may refer to:

*Signet, Kenya, A subsidiary of the Kenyan Broadcasting Corporation (KBC), specifically set up to broadcast and distribute the DTT signals

* Signet ring, a ring with a seal set into it, typically by leaving an impression in sea ...

or privy seal

A privy seal refers to the personal seal of a reigning monarch, used for the purpose of authenticating official documents of a much more personal nature. This is in contrast with that of a great seal, which is used for documents of greater impor ...

; to refuse to abjure the authority of the Pope

The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

; to marry any of the Sovereign's children, sisters, aunts, nephews or nieces without royal permission; to marry the Sovereign without disclosing prior sexual relationships; attempting to enter into a sexual relationship (out of marriage) with the Queen or a Princess; denying the Sovereign's official styles and titles; and refusing to acknowledge the Sovereign as the Supreme Head of the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Brit ...

. Some offences, whose complexion was entirely different from traitorous actions, were nevertheless made treasons; thus, it was high treason for a Welshman to steal cattle

Cattle (''Bos taurus'') are large, domesticated, cloven-hooved, herbivores. They are a prominent modern member of the subfamily Bovinae and the most widespread species of the genus '' Bos''. Adult females are referred to as cows and adult ...

, to commit murder by poisoning ( 1531), or for an assembly of twelve or more rioters to refuse to disperse when so commanded.

All new forms of high treason introduced since the Treason Act 1351, except those to do with forgery and counterfeiting, were abrogated by the Treason Act 1547

The Treason Act 1547 (1 Ed. 6 c.12) was an Act of the Parliament of England. It is mainly notable for being the first instance of the rule that two witnesses are needed to prove a charge of treason, a rule which still exists today in the United S ...

, which was passed at the beginning of the reign of Edward VI

Edward VI (12 October 1537 – 6 July 1553) was King of England and Ireland from 28 January 1547 until his death in 1553. He was crowned on 20 February 1547 at the age of nine. Edward was the son of Henry VIII and Jane Seymour and the first E ...

. The Act created new kinds of treason however, including denying that the King was the Supreme Head of the Church, and attempting to interrupt the succession to the throne as determined by the Act of Succession 1543.

When Mary I

Mary I (18 February 1516 – 17 November 1558), also known as Mary Tudor, and as "Bloody Mary" by her Protestant opponents, was Queen of England and Ireland from July 1553 and Queen of Spain from January 1556 until her death in 1558. She ...

became queen in 1553, she passed an Act abolishing all treasons whatsoever which had been created since 1351. Later that year, however, the offence of forging the Sovereign's sign manual or signet once again became high treason. Furthermore, the anti-counterfeiting laws were extended so as to include foreign money deemed legal tender in England. Thus, it became high treason to counterfeit such foreign money, or to import counterfeit foreign money and actually attempt to use it to make a payment. (But importing any counterfeit English money remained high treason, even if no attempt were made to use it in payment.) Mary also made it high treason to kill Philip II of Spain

Philip II) in Spain, while in Portugal and his Italian kingdoms he ruled as Philip I ( pt, Filipe I). (21 May 152713 September 1598), also known as Philip the Prudent ( es, Felipe el Prudente), was King of Spain from 1556, King of Portugal from ...

, her king consort, or to try to deprive him of his title.

William III made it high treason to manufacture, buy, sell or possess instruments whose sole purpose is to coin money. He also made adding any inscription normally found on a coin to any piece of metal that may resemble a coin high treason. George II made it high treason to mark or colour a silver coin so as to make it resemble a gold one.

Aside from laws relating to counterfeiting and succession, very few acts concerning the definition of high treason were passed. Under laws passed during the reign of Elizabeth I, it was high treason for an individual to attempt to defend the jurisdiction of the Pope

The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

over the English Church for a third time (a first offence being a misdemeanour and a second offence a felony), or for a Roman Catholic priest to enter the realm and refuse to conform to the English Church, or to purport to release a subject of his allegiance to the Crown or the Church of England and to reconcile him or her with a foreign power. Charles II's Sedition Act 1661 made it treason to imprison, restrain or wound the king. Although this law was abolished in the United Kingdom in 1998, it still continues to apply in some Commonwealth

A commonwealth is a traditional English term for a political community founded for the common good. Historically, it has been synonymous with "republic". The noun "commonwealth", meaning "public welfare, general good or advantage", dates from the ...

countries. Under laws passed after James II was deposed, it became treasonable to correspond with the Jacobite claimants ''( main article)'', or to hinder succession to the Throne under the Act of Settlement 1701

The Act of Settlement is an Act of the Parliament of England that settled the succession to the English and Irish crowns to only Protestants, which passed in 1701. More specifically, anyone who became a Roman Catholic, or who married one, be ...

, or to publish that anyone other than the individual specified by the Act of Settlement had the right to inherit the Crown.

History: after union with Scotland

In 1708, following theUnion of England and Scotland

The Acts of Union ( gd, Achd an Aonaidh) were two Acts of Parliament: the Union with Scotland Act 1706 passed by the Parliament of England, and the Union with England Act 1707 passed by the Parliament of Scotland. They put into effect the te ...

in the previous year, Queen Anne signed the Treason Act 1708, which harmonised the treason laws of both former kingdoms (effective from 1 July 1709). The English offences of high treason and misprision of treason

Misprision of treason is an offence found in many common law jurisdictions around the world, having been inherited from English law. It is committed by someone who knows a treason is being or is about to be committed but does not report it to a p ...

(but not petty treason) were extended to Scotland, and the treasonable offences then existing in Scotland were abolished. These were: "theft in Landed Men", murder in breach of trust, fire-raising, "firing coalheughs" and assassination. The Act also made it treason to counterfeit the Great Seal of Scotland, or to slay the Lords of Session or Lords of Justiciary "sitting in Judgment in the Exercise of their Office within Scotland".

In general, treason law in Scotland remained the same as in England, except that when in England the offence of counterfeiting the Great Seal of the United Kingdom ''etc.'' (an offence under other legislation) was reduced from treason to felony

A felony is traditionally considered a crime of high seriousness, whereas a misdemeanor is regarded as less serious. The term "felony" originated from English common law (from the French medieval word "félonie") to describe an offense that res ...

by the Forgery Act 1861, that Act did not apply to Scotland, and though in England since 1861 it has not been treason to forge the Scottish Great Seal, in Scotland this remains treason today. When the Scottish Parliament

The Scottish Parliament ( gd, Pàrlamaid na h-Alba ; sco, Scots Pairlament) is the devolved, unicameral legislature of Scotland. Located in the Holyrood area of the capital city, Edinburgh, it is frequently referred to by the metonym Holyr ...

was set up in 1998, treason and treason felony were among the " reserved matters" it was prohibited from legislating about, ensuring that the law of treason remains uniform throughout Great Britain.

Between 1817 and 1820 it was treason to kill the Prince Regent. In 1832 counterfeiting money ceased to be treason and became a felony. In Ireland, counterfeiting seals ceased to be treason in 1861, in line with England and Wales.

First World War

A notable treason trial occurred at the Old Bailey in 1916 when Roger Casement was convicted of collusion with Germany for his role in theEaster Rising

The Easter Rising ( ga, Éirí Amach na Cásca), also known as the Easter Rebellion, was an armed insurrection in Ireland during Easter Week in April 1916. The Rising was launched by Irish republicans against British rule in Ireland with t ...

in Ireland. The charges against him were conspiracy to incite mutiny among Prisoners of War held captive by Germany, collusion with an enemy power in times of war, arms trafficking, and levying war against the King. Casement notably did not deny any of the charges brought against him and simply refused to acknowledge that the Treason Act 1351 even applied to him leaving his defence counsel with few options beyond arguing about legal technicalities around the precise wording of the Act. The prosecution countered that as Casement had worked as a diplomat for the British Government

ga, Rialtas a Shoilse gd, Riaghaltas a Mhòrachd

, image = HM Government logo.svg

, image_size = 220px

, image2 = Royal Coat of Arms of the United Kingdom (HM Government).svg

, image_size2 = 180px

, caption = Royal Arms

, date_est ...

for almost all of his adult life and had accepted a knighthood and a pension from the Crown on retirement in 1911 he owed personal loyalty to the King when he committed the acts for which he was brought to trial. The jury agreed with the prosecution and found Casement guilty. He was hanged at Pentonville Prison

HM Prison Pentonville (informally "The Ville") is an English Category B men's prison, operated by His Majesty's Prison Service. Pentonville Prison is not in Pentonville, but is located further north, on the Caledonian Road in the Barnsbury ar ...

on 3 August 1916.

The Titles Deprivation Act 1917

The Titles Deprivation Act 1917 is an Act of Parliament of the United Kingdom which authorised enemies of the United Kingdom during the First World War to be deprived of their British peerages and royal titles.

Background

The British royal famil ...

authorised the king to deprive peers of their peerage if they had assisted the enemy during the war, or voluntarily resided in enemy territory. This was mainly in response to the closeness of the British royal family with some German thrones, leading to the loss of British titles from the dukes of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha

Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (german: Sachsen-Coburg und Gotha), or Saxe-Coburg-Gotha (german: Sachsen-Coburg-Gotha, links=no ), was an Ernestine, Thuringian duchy ruled by a branch of the House of Wettin, consisting of territories in the present ...

and Brunswick, the Crown Prince of Hanover, and the Viscount Taaffe. Whilst the act allowed for their descendants to petition for the restoration of these titles, no descendant has done so.

Second World War

John Amery

John Amery (14 March 1912 – 19 December 1945) was a British fascist and Nazi collaborator during World War II. He was the originator of the British Free Corps, a volunteer Waffen-SS unit composed of former British and Dominion prisone ...

was executed in 1945 after pleading guilty to eight charges of treason for efforts to recruit British prisoners of war into the British Free Corps and for making propaganda

Propaganda is communication that is primarily used to influence or persuade an audience to further an agenda, which may not be objective and may be selectively presenting facts to encourage a particular synthesis or perception, or using loaded ...

broadcasts for Nazi Germany.

The last execution for treason in the United Kingdom was held in 1946. William Joyce (also known as Lord Haw Haw

Lord Haw-Haw was a nickname applied to William Joyce, who broadcast Nazi propaganda to the UK from Germany during the Second World War. The broadcasts opened with "Germany calling, Germany calling", spoken in an affected upper-class English ac ...

) stood accused of levying war against King George VI

George VI (Albert Frederick Arthur George; 14 December 1895 – 6 February 1952) was King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Commonwealth from 11 December 1936 until his death in 1952. He was also the last Emperor of I ...

by travelling to Germany in the early months of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

and taking up employment as a broadcaster of pro-Nazi propaganda to British radio audiences. He was awarded a personal commendation by Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 and the ...

in 1944 for his contribution to the German war effort. On his capture at the end of the war, Parliament rushed through the Treason Act 1945

The Treason Act 1945 (8 & 9 Geo.6 c.44) was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom.

It was introduced into the House of Lords as a purely procedural statute, whose sole purpose was to abolish the old and highly technical procedure in ca ...

to facilitate a trial that would have the same procedure as a trial for murder. Before the Act, a trial for treason short of regicide

Regicide is the purposeful killing of a monarch or sovereign of a polity and is often associated with the usurpation of power. A regicide can also be the person responsible for the killing. The word comes from the Latin roots of ''regis'' ...

involved an elaborate and lengthy medieval procedure. Although Joyce was born in the United States to an Irish father and an English mother, he had moved to Britain in his teens and applied for a British passport in 1933 which was still valid when he defected to Germany and so under the law he owed allegiance to Britain. He appealed against his conviction to the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by appointment, heredity or official function. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminst ...

on the grounds he had lied about his country of birth on the passport application and did not owe allegiance to any country at the beginning of the war. The appeal was not upheld and he was executed at Wandsworth Prison

HM Prison Wandsworth is a Category B men's prison at Wandsworth in the London Borough of Wandsworth, South West London, England. It is operated by His Majesty's Prison Service and is one of the largest prisons in the UK.

History

The prison was ...

on 3 January 1946.

It is thought the strength of public feeling against Joyce as a perceived traitor was the driving force behind his prosecution. The only evidence offered at his trial that he had begun broadcasting from Germany while his British passport was valid was the testimony of a London police inspector who had questioned him before the war while he was an active member of the British Union of Fascists

The British Union of Fascists (BUF) was a British fascist political party formed in 1932 by Oswald Mosley. Mosley changed its name to the British Union of Fascists and National Socialists in 1936 and, in 1937, to the British Union. In 1939, f ...

and claimed to have recognised his voice on a propaganda broadcast in the early weeks of the war (he already had previous convictions for assault

An assault is the act of committing physical harm or unwanted physical contact upon a person or, in some specific legal definitions, a threat or attempt to commit such an action. It is both a crime and a tort and, therefore, may result in cr ...

and riotous assembly as a result of street fights with communists and anarchists).

Treachery Act 1940

Until 1945 treason had its own rules of evidence and procedure which made it difficult to prosecute accused traitors, such as the need for two witnesses to the same offence. Consequently, in the Second World War it was perceived that there was a need for a new offence with which to deal with traitors more expediently. The Treachery Act 1940 was passed creating afelony

A felony is traditionally considered a crime of high seriousness, whereas a misdemeanor is regarded as less serious. The term "felony" originated from English common law (from the French medieval word "félonie") to describe an offense that res ...

called treachery, to punish disloyalty and espionage. It was a capital offence. Seventeen people were sentenced to be shot or hanged for this offence instead of for treason (one death sentence was commuted). Theodore Schurch was the last person to be put to death for treachery, in 1946. He was also the last person to be executed for a crime other than murder. Josef Jakobs

Josef Jakobs (30 June 1898 – 15 August 1941) was a German spy and the last person to be executed at the Tower of London. He was captured shortly after parachuting into the United Kingdom during the Second World War. Convicted of espionage unde ...

, a German spy executed for treachery, was the last person to be executed in the Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, which is sep ...

.

The Treachery Act 1940 was suspended in February 1946, and was repealed in 1967.

1945 to 2015

In June 1945 theTreason Act 1945

The Treason Act 1945 (8 & 9 Geo.6 c.44) was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom.

It was introduced into the House of Lords as a purely procedural statute, whose sole purpose was to abolish the old and highly technical procedure in ca ...

abolished the special rules of evidence and procedure formerly used in treason trials, and replaced them with the rules applicable to murder trials, to simplify the law. As discussed above, the last treason prosecutions occurred later that year.

From 1945, treason consisted of the offences which are treason today ( see above), plus two other kinds. The Succession to the Crown Act 1707

The Succession to the Crown Act 1707 (6 Ann c 41) is an Act of Parliament of the Parliament of Great Britain. It is still partly in force in Great Britain.

The Act was passed at a time when Parliament was anxious to ensure the succession of a Pr ...

made it treason to affirm that any person has a right to succeed to the Crown otherwise than according to the Act of Settlement and Acts of Union, or that the Crown and Parliament cannot legislate for the limitation of the succession to the Crown. This was abolished in 1967. The Treason Act 1795 made it treason to "compass, imagine, invent, devise or intend death or destruction, or any bodily harm tending to death or destruction, maim or wounding, imprisonment or restraint, of the person of ... the King." This was abolished in 1998, when the death penalty was also abolished.

On 26 March 2015 the Succession to the Crown Act 2013

The Succession to the Crown Act 2013 (c. 20) is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that altered the laws of succession to the British throne in accordance with the 2011 Perth Agreement. The Act replaced male-preference primogenit ...

came into effect,Succession to the Crown Act 2013 (Commencement) Order 2015at legislation.org.uk (retrieved 30 March 2015) which amended the line of succession to the throne to give women the same right to succeed to the throne as their brothers. In consequence of this, the Treason Act 1351 was amended in two ways. Whereas it had been treason to encompass the death of the monarch's eldest ''son'' and heir, this was amended to cover an heir of either sex. It had also been treason to "violate" the wife of the monarch's eldest son, but the 2013 Act restricted this to cases where the eldest son is also the heir to the throne.

Liability

As a general rule, no British criminal court has jurisdiction over the Sovereign, from whom they derive their authority. As SirWilliam Blackstone

Sir William Blackstone (10 July 1723 – 14 February 1780) was an English jurist, judge and Tory politician of the eighteenth century. He is most noted for writing the ''Commentaries on the Laws of England''. Born into a middle-class family ...

writes, "the law supposes an incapacity of doing wrong from the excellence and perfection ... of the King." Furthermore, to charge the sovereign with high treason would be inconsistent, as it would constitute accusing him of disloyalty to himself. After the English Civil War

The English Civil War (1642–1651) was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Parliamentarians (" Roundheads") and Royalists led by Charles I (" Cavaliers"), mainly over the manner of England's governance and issues of r ...

, however, Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

was tried for treason against the people of England. His trial and execution were irregular; they were more accurately products of a revolution, rather than a legal precedent, and those responsible were themselves tried for treason after the monarchy was restored ''(see List of regicides of Charles I

Following the trial of Charles I in January 1649, 59 commissioners (judges) signed his death warrant. They, along with several key associates and numerous court officials, were the subject of punishment following the restoration of the monarch ...

)''. However, a person who attempts to become the Sovereign without a valid claim can be held guilty of treason. Consequently, Lady Jane Grey

Lady Jane Grey ( 1537 – 12 February 1554), later known as Lady Jane Dudley (after her marriage) and as the "Nine Days' Queen", was an English noblewoman who claimed the throne of England and Ireland from 10 July until 19 July 1553.

Jane was ...

was executed for treason for usurping the throne in 1553.

An alien resident in the United Kingdom owes allegiance

An allegiance is a duty of fidelity said to be owed, or freely committed, by the people, subjects or citizens to their state or sovereign.

Etymology

From Middle English ''ligeaunce'' (see medieval Latin ''ligeantia'', "a liegance"). The ''al ...

to the Crown, and may be prosecuted for high treason. The only exception is an enemy lawful combatant in wartime, e.g. a uniformed enemy soldier on British territory.

A British subject resident abroad also continues to owe allegiance to the Crown. If he or she becomes a citizen of another state before a war during which he bears arms against the Crown, he or she is not guilty of high treason. On the other hand, becoming a citizen of an enemy state during wartime is high treason, as it constitutes adhering to the sovereign's enemies.

Insane

Insanity, madness, lunacy, and craziness are behaviors performed by certain abnormal mental or behavioral patterns. Insanity can be manifest as violations of societal norms, including a person or persons becoming a danger to themselves or to ...

individuals are not punished for their crimes. During the reign of Henry VIII, however, it was enacted that in the cases of high treason, an idiot could be tried in his absence as if he were perfectly sane. In the reign of Mary I, this statute was repealed. Today there are powers to send insane defendants to a mental hospital.

The Treason Act 1495

The Treason Act 1495, formally referred as the Act 11 Hen 7 c 1 and informally as the statute, is an Act of the Parliament of England which was passed in the reign of Henry VII of England.

Background

After the defeat of Richard III in the ...

provides that in a civil war between two claimants to the throne, those who fight for the losing side cannot be held guilty of a crime merely for fighting against the winner.

Duress and marital coercion

Duress is not available as a defence to treason involving the death of the sovereign. In England and Wales and in Northern Ireland, the former defence ofmarital coercion

Marital coercion was a defence to most crimes under English criminal law and under the criminal law of Northern Ireland. It is similar to duress. It was abolished in England and Wales by section 177 of the Anti-social Behaviour, Crime and Policing ...

was not available to a wife charged with treason.

Trial

Peers and their wives and widows were formerly entitled to be tried for treason and for felonies in theHouse of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by appointment, heredity or official function. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminst ...

or the Court of the Lord High Steward, the former being used in every case except when Parliament was not in session. In the House of Lords, the Lord High Steward presided, but the entire House acted as both judge and jury. In the Lord High Steward's Court, the Lord High Steward was a judge, and a panel of "Lords Triers" served as a jury. There was no right of peremptory challenge in either body. Trial by either body ceased in 1948, since when peers have been tried in the same courts as commoner

A commoner, also known as the ''common man'', ''commoners'', the ''common people'' or the ''masses'', was in earlier use an ordinary person in a community or nation who did not have any significant social status, especially a member of neither ...

s.

Commoners, and now peers and their wives and widows, are entitled to be tried for high treason, and also for lesser crimes, by jury

A jury is a sworn body of people (jurors) convened to hear evidence and render an impartial verdict (a finding of fact on a question) officially submitted to them by a court, or to set a penalty or judgment.

Juries developed in England d ...

. Formerly, commoners were entitled to thirty-five peremptory challenges in cases of treason, but only twenty in cases of felony and none in cases of misdemeanours; all peremptory challenges, however, were abolished in 1988.

Another mode of trial for treason, and also for other crimes, is in the House of Lords following impeachment

Impeachment is the process by which a legislative body or other legally constituted tribunal initiates charges against a public official for misconduct. It may be understood as a unique process involving both political and legal elements.

In ...

by the House of Commons (which has not occurred since 1806). Normally, the Lord Chancellor

The lord chancellor, formally the lord high chancellor of Great Britain, is the highest-ranking traditional minister among the Great Officers of State in Scotland and England in the United Kingdom, nominally outranking the prime minister. Th ...

presided during trials; when a peer is accused of high treason, however, the Lord High Steward

The Lord High Steward is the first of the Great Officers of State in England, nominally ranking above the Lord Chancellor.

The office has generally remained vacant since 1421, and is now an ''ad hoc'' office that is primarily ceremonial and ...

must preside. By convention, however, the Lord Chancellor would be appointed Lord High Steward for the duration of the trial—the post of Lord High Steward ceased to be regularly filled in 1421, being revived only for trials of peers and for coronation

A coronation is the act of placement or bestowal of a crown upon a monarch's head. The term also generally refers not only to the physical crowning but to the whole ceremony wherein the act of crowning occurs, along with the presentation of o ...

s.

Finally, it was possible for Parliament to pass an Act of attainder, which pronounces guilt without a trial. Historically, Acts of attainder have been used against political opponents when speedy executions were desired. In 1661, Parliament passed acts posthumously attainting Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English politician and military officer who is widely regarded as one of the most important statesmen in English history. He came to prominence during the 1639 to 1651 Wars of the Three ...

, Henry Ireton

Henry Ireton ((baptised) 3 November 1611 – 26 November 1651) was an English general in the Parliamentarian army during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, and the son-in-law of Oliver Cromwell. He died of disease outside Limerick in November 16 ...

and John Bradshaw—who were previously involved in Charles I's trial—of treason. These three individuals were posthumously executed, the only people to suffer this fate under English treason laws. (In 1540, a Scottish court summoned Robert Leslie, who was deceased, for a trial for treason. The Estates-General declared the summons lawful; Leslie's body was exhumed, and his bones were presented at the bar of the court. This procedure was never used in England.)

Procedure and evidence

Before 1945

Certain special rules procedures have historically applied to high treason cases. The privilege of the peerage andparliamentary privilege

Parliamentary privilege is a legal immunity enjoyed by members of certain legislatures, in which legislators are granted protection against civil or criminal liability for actions done or statements made in the course of their legislative duties ...

preclude the arrest of certain individuals (including peers, wives and widows of peers and members of Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: representing the electorate, making laws, and overseeing the government via hearings and inquiries. Th ...

) in many cases, but treason was not included (nor were felony or breach of the peace). Similarly, an individual could not claim sanctuary

A sanctuary, in its original meaning, is a sacred place, such as a shrine. By the use of such places as a haven, by extension the term has come to be used for any place of safety. This secondary use can be categorized into human sanctuary, a sa ...

when charged with high treason; this distinction between treasons and felonies was lost as sanctuary laws were repealed in the late 17th and early 19th century. The defendant, furthermore, could not claim the benefit of clergy

In English law, the benefit of clergy (Law Latin: ''privilegium clericale'') was originally a provision by which clergymen accused of a crime could claim that they were outside the jurisdiction of the secular courts and be tried instead in an ec ...

in treason cases; but the benefit of the clergy, as well, was abolished during the 19th century.

Formerly, if an individual stood mute and refused to plead guilty or not guilty for a felony, he would be tortured until he enter a plea; if he died in the course of the torture, his lands would not be seized to the Crown, and his heirs would be allowed to succeed to them. In cases of high treason, however, an individual could not save his lands by refusing to enter a plea; instead, a refusal would be punished by immediate forfeiture of all estates. This distinction between treasons and felonies ended in 1772, when the court was permitted to enter a plea on a defendant's behalf.

Formerly, an individual was not entitled to assistance of counsel in any capital case, including treason; the rule, however, was abolished in treason cases by the Treason Act 1695

The Treason Act 1695 (7 & 8 Will 3 c 3) is an Act of the Parliament of England which laid down rules of evidence and procedure in high treason trials. It was passed by the English Parliament but was extended to cover Scotland in 1708 and Irel ...

. The same Act extended a rule from 1661 which had made it necessary to produce at least two witnesses to prove each alleged offence of high treason. Nearly one hundred years later a stricter version of this rule was incorporated into the Constitution of the United States

The Constitution of the United States is the supreme law of the United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, in 1789. Originally comprising seven articles, it delineates the nati ...

. The 1695 Act also provided for a three-year time limit on bringing prosecutions for treason (except for assassinating the king) and misprision of treason

Misprision of treason is an offence found in many common law jurisdictions around the world, having been inherited from English law. It is committed by someone who knows a treason is being or is about to be committed but does not report it to a p ...

, another rule which has been imitated in some common law countries.

These rules made it difficult to prosecute charges of treason, and the rule was relaxed by the Treason Act 1800 to make attempts on the life of the King subject to the same rules of procedure and evidence as existed in murder trials (which did not require two witnesses). This change was extended to all assaults on the Sovereign by the Treason Act 1842

The Treason Act 1842 (5 & 6 Vict. c.51) is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It was passed early in the reign of Queen Victoria. The last person to be convicted under the Act was Marcus Sarjeant in 198 ...

. Finally the special rules for treason were abolished by the Treason Act 1945

The Treason Act 1945 (8 & 9 Geo.6 c.44) was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom.

It was introduced into the House of Lords as a purely procedural statute, whose sole purpose was to abolish the old and highly technical procedure in ca ...

when the rules of evidence and procedure in all cases of treason were made the same as for murder. However, the original three-year time limit stated above survived into the present day. This meant that when James Hewitt

James Lifford Hewitt (born 30 April 1958) is a British former cavalry officer in the British Army. He came to public attention in the mid-1990s after he disclosed an affair with Diana, Princess of Wales, while she was still married to then-Pri ...

was accused of treason by the tabloid press in 1996 because of his affair with the Princess of Wales

Princess of Wales (Welsh: ''Tywysoges Cymru'') is a courtesy title used since the 14th century by the wife of the heir apparent to the English and later British throne. The current title-holder is Catherine (née Middleton).

The title was fi ...

, he could not have been prosecuted because it could not be proved that he had done it within the foregoing three-year period.

Modern procedure

The procedure in trials for treason is the same as that in trials for murder. It is therefore an indictable-only offence.Alternative verdict

England and Wales On the trial of an indictment for treason, the jury cannot return analternative verdict

In criminal law, a lesser included offense is a crime for which all of the elements necessary to impose liability are also elements found in a more serious crime. It is also used in non-criminal violations of law, such as certain classes of tr ...

to the offence charged in that indictment under section 6(3) of the Criminal Law Act 1967. For example, the jury cannot give an alternative verdict of manslaughter

Manslaughter is a common law legal term for homicide considered by law as less culpable than murder. The distinction between murder and manslaughter is sometimes said to have first been made by the ancient Athenian lawmaker Draco in the 7th ce ...

in cases of the assassination of the monarch. The Homicide Act 1957 does not apply. However, under the common law the jury may return a verdict of guilty of misprision of treason

Misprision of treason is an offence found in many common law jurisdictions around the world, having been inherited from English law. It is committed by someone who knows a treason is being or is about to be committed but does not report it to a p ...

instead of treason.

Northern Ireland

On the trial of an indictment for treason, the jury cannot return an alternative verdict to the offence charged in that indictment under section 6(2) of the Criminal Law Act (Northern Ireland) 1967. For this purpose each count is considered to be a separate indictment (s.6(7)).

Limitation

A person may not be indicted for treason committed within the United Kingdom (subject to the following exception) unless the indictment is preferred within three years of the commission of that offence. This limitation does not apply to treason which consists of designing, endeavouring or attempting to assassinate the sovereign. There is no time limit on the prosecution of treason committed outside of the United Kingdom. The same time limit applies to attempting or conspiring to commit treason.Bail

In England and Wales, a person charged with treason may not be grantedbail

Bail is a set of pre-trial restrictions that are imposed on a suspect to ensure that they will not hamper the judicial process. Bail is the conditional release of a defendant with the promise to appear in court when required.

In some countrie ...

except by order of a High Court judge or of the Secretary of State. The same rule applies in Northern Ireland.

In Scotland, all crimes and offences which are treason are bailable.

Punishment

Before 1998

The form of execution once suffered by traitors was often (though not invariably) torturous. For men the statutory penalty (in England) was to be ''hanged, drawn and quartered

To be hanged, drawn and quartered became a statutory penalty for men convicted of high treason in the Kingdom of England from 1352 under King Edward III (1327–1377), although similar rituals are recorded during the reign of King Henry III ...

''. The condemned could not walk or be carried to the place of execution; the sentence required that they were to be drawn: they might be dragged along the ground, but were normally tied onto a hurdle which was drawn to the place of execution by a horse. A man would then be

hanged

Hanging is the suspension of a person by a noose or ligature around the neck.Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd ed. Hanging as method of execution is unknown, as method of suicide from 1325. The '' Oxford English Dictionary'' states that hanging ...

by a noose around the neck until almost dead. Whilst still alive, he would be cut down and allowed to drop to the ground, stripped of his clothes, his genitals cut off, his viscera

In biology, an organ is a collection of tissues joined in a structural unit to serve a common function. In the hierarchy of life, an organ lies between tissue and an organ system. Tissues are formed from same type cells to act together in a f ...

pulled out and burnt before his own eyes, and other organs would be torn out of his body. The body would be decapitated, and cut into four-quarters. The body parts would be at the disposal of the Sovereign, and generally they would be gibbet

A gibbet is any instrument of public execution (including guillotine, executioner's block, impalement stake, hanging gallows, or related scaffold). Gibbeting is the use of a gallows-type structure from which the dead or dying bodies of cri ...

ed or publicly displayed as a warning. The body parts would be parboiled in salt and cumin

Cumin ( or , or Article title

) (''Cuminum cyminum'') is a

) (''Cuminum cyminum'') is a

in 1814 so that the offender would hang until dead; the disembowelling, beheading and quartering were to be carried out posthumously.

Women were excluded from this type of punishment and instead were drawn and then

See also the

"Treason"

at the ''

"On Treason"

by

BAILII

*''Halsbury's Laws of England'', 4th Edition, 2006 reissue, Volume 11(1), paragraphs 363, 364 and 366 {{DEFAULTSORT:High Treason In The United Kingdom Law of the United Kingdom Treason in the United Kingdom English criminal law Scottish criminal law Statutory law

burned at the stake

Death by burning (also known as immolation) is an execution and murder method involving combustion or exposure to extreme heat. It has a long history as a form of public capital punishment, and many societies have employed it as a punishment f ...

, until this was replaced with hanging by the Treason Act 1790 and the Treason by Women Act (Ireland) 1796

The Treason by Women Act (Ireland) 1796 (36 Geo 3 c 31 (I)) was an Act of the Parliament of the Kingdom of Ireland which reduced the penalty for women convicted of high treason and petty treason from death by burning to death by hanging. It was ...

.

The penalty for high treason by counterfeiting or clipping coins was the same as the penalty for petty treason (which for men was drawing and hanging without the torture and quartering, and for women was burning or hanging.)

Individuals of noble birth were beheaded without being subjected to either form of torture. Commoners' sentences were sometimes commuted to beheading—a sentence not formally removed from British law until 1973.

In addition to being tortured and executed, a traitor was also deemed "attainted

In English criminal law, attainder or attinctura was the metaphorical "stain" or "corruption of blood" which arose from being condemned for a serious capital crime (felony or treason). It entailed losing not only one's life, property and heredit ...

". The first consequence of attainder was forfeiture; all lands and estates of a traitor were forever forfeit to the Crown. A second consequence was corruption of blood; the attainted person could neither inherit property, nor transmit it to his or her descendants. This may have been open to abuse, either by avaricious monarchs or by parliament when little (if any) evidence was available to secure a conviction. There was a complex and ceremonial procedure used to try treason cases, with a strict requirement for a minimum of two witnesses to the crime.

In 1832 the death penalty was abolished for treason by forging seals and the Royal sign manual.

In 1870, attainder was abolished. In the same year in England, and in 1949 in Scotland, posthumous drawing and quartering was abolished, and so the sole punishment was hanging.

Beheading was abolished in 1973, by which time it had long been obsolete, having last been used in 1747.

By 1965, capital punishment had been abolished for almost all crimes, but was still mandatory (unless the offender was pardoned or the sentence commuted) for high treason until 1998. By section 36 of the Crime and Disorder Act 1998

The Crime and Disorder Act 1998 (c.37) is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. The Act was published on 2 December 1997 and received Royal Assent in July 1998. Its key areas were the introduction of Anti-Social Behaviour Orders, Sex ...

the maximum punishment for high treason became life imprisonment. ''(See also Treason Act 1814.)''

Today

A person convicted of treason is liable to imprisonment for life or for any shorter term. A whole life tariff may be imposed for the gravest offences. (SeeLife imprisonment in England and Wales

In England and Wales, life imprisonment is a sentence that lasts until the death of the prisoner, although in most cases the prisoner will be eligible for early release after a minimum term set by the judge. In exceptional cases, however, a j ...

for more details).

Treason also entails disqualification from public office, and loss of suffrage

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply franchise, is the right to vote in public, political elections and referendums (although the term is sometimes used for any right to vote). In some languages, and occasionally in English, the right to v ...

(except in local elections). This rule does not apply in Scotland.

Scottish Parliament and Northern Ireland Assembly

Treason (includingconstructive treason Constructive treason is the judicial extension of the statutory definition of the crime of treason. For example, the English Treason Act 1351 declares it to be treason "When a Man doth compass or imagine the Death of our Lord the King". This was su ...

) is a reserved matter

In the United Kingdom, devolved matters are the areas of public policy where the Parliament of the United Kingdom has devolved its legislative power to the national assemblies of Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, while reserved matte ...

on which the Scottish Parliament

The Scottish Parliament ( gd, Pàrlamaid na h-Alba ; sco, Scots Pairlament) is the devolved, unicameral legislature of Scotland. Located in the Holyrood area of the capital city, Edinburgh, it is frequently referred to by the metonym Holyr ...

cannot legislate.

Treason (but not powers of arrest or criminal procedure) is an excepted matter on which the Northern Ireland Assembly

sco-ulster, Norlin Airlan Assemblie

, legislature = Seventh Assembly

, coa_pic = File:NI_Assembly.svg

, coa_res = 250px

, house_type = Unicameral

, house1 =

, leader1_type = S ...

cannot legislate.

Treason today

Almost all treason-related offences introduced since the Treason Act 1351 was passed have been abolished or relegated to lesser offences. The Treason Act 1351, on the other hand, has not been significantly amended; the main changes involve the removal of counterfeiting and forgery, as explained above. For the state of the law today, see the ''Offences'' section above. In Autumn 2001 following9/11

The September 11 attacks, commonly known as 9/11, were four coordinated suicide terrorist attacks carried out by al-Qaeda against the United States on Tuesday, September 11, 2001. That morning, nineteen terrorists hijacked four commerci ...

, the British government threatened British citizens who fought for the Taliban

The Taliban (; ps, طالبان, ṭālibān, lit=students or 'seekers'), which also refers to itself by its state (polity), state name, the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, is a Deobandi Islamic fundamentalism, Islamic fundamentalist, m ...

army in Afghanistan against Anglo-American troops with prosecution for treason, although no one was subsequently tried, at least not for treason.

On 8 August 2005, it was reported that the UK Government was considering bringing prosecutions for treason against a number of British Islamic clerics who have publicly spoken positively about acts of terrorism against civilians in Britain, or attacks on British soldiers abroad, including the 7 July London bombings and numerous attacks on troops serving in Iraq and Afghanistan. Following this threat one foreign cleric who the British government had failed to deport fled to Lebanon, only to request to be rescued by the British military during the 2006 Israeli-Lebanon War. However, later that year prosecutors indicted Abu Hamza al-Masri for inciting murder (he was convicted in February 2006), and it now seems unlikely that anyone will be charged with treason in the foreseeable future.

In 2008 the former attorney-general, Lord Goldsmith QC, published a report on his review of British citizenship. One of his recommendations was for a "thorough reform and rationalisation of the law" of treason.

In 2014 the Foreign Secretary

The secretary of state for foreign, Commonwealth and development affairs, known as the foreign secretary, is a Secretary of State (United Kingdom), minister of the Crown of the Government of the United Kingdom and head of the Foreign, Commonwe ...

Philip Hammond revealed that the British Government was considering high treason charges for Islamic extremists

Islamic extremism, Islamist extremism, or radical Islam, is used in reference to extremist beliefs and behaviors which are associated with the Islamic religion. These are controversial terms with varying definitions, ranging from academic und ...

in response to growing numbers of British Jihad fighters travelling to Syria and Iraq to join the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant

An Islamic state is a state that has a form of government based on Islamic law (sharia). As a term, it has been used to describe various historical polities and theories of governance in the Islamic world. As a translation of the Arabic ter ...

. However this did not come to pass.

On the 2 August 2022, Jaswant Singh Chail was charged with offences under section 2 of the Treason Act 1842

The Treason Act 1842 (5 & 6 Vict. c.51) is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It was passed early in the reign of Queen Victoria. The last person to be convicted under the Act was Marcus Sarjeant in 198 ...

. He had been arrested in the grounds of Windsor Castle

Windsor Castle is a royal residence at Windsor in the English county of Berkshire. It is strongly associated with the English and succeeding British royal family, and embodies almost a millennium of architectural history.

The original c ...

on 25 December, 2021 and was charged with "discharging or aiming firearms, or throwing or using any offensive matter or weapon, with intent to injure or alarm her Majesty" .Acts in force today

Acts containing substantive or procedural law * Treason Act 1351 (most forms of treason) *Treason Act 1495

The Treason Act 1495, formally referred as the Act 11 Hen 7 c 1 and informally as the statute, is an Act of the Parliament of England which was passed in the reign of Henry VII of England.

Background

After the defeat of Richard III in the ...

(special defence to treason)

* Treason Act (Ireland) 1537 (Northern Ireland only)

*Crown of Ireland Act 1542

The Crown of Ireland Act 1542 is an Act passed by the Parliament of Ireland (33 Hen. 8 c. 1) on 18 June 1542, which created the title of King of Ireland for King Henry VIII of England and his successors, who previously ruled the island as Lor ...

(Northern Ireland only)

*Treason Act 1695

The Treason Act 1695 (7 & 8 Will 3 c 3) is an Act of the Parliament of England which laid down rules of evidence and procedure in high treason trials. It was passed by the English Parliament but was extended to cover Scotland in 1708 and Irel ...

(limitation on prosecution)

*Treason Act 1702

The Treason Act 1702 (1 Anne Stat. 2 c. 21Some volumes cite it as c.17) is an Act of the Parliament of England, passed to enforce the line of succession to the English throne (today the British throne), previously established by the Bill of Righ ...

(a further form of treason)

* Treason Act (Ireland) 1703 (equivalent to Treason Act 1702)

* Treason Act 1708 (Scotland only)

* Treason Act 1814 and Forfeiture Act 1870 (the penalty for treason)

* Treason (Ireland) Act 1821 (extended provisions of the 1695 Act to Ireland and still applies today in Northern Ireland)

* Treason Felony Act 1848 (still-existing offences which used to be treason)

Acts creating similar offencesSee also the

Treason Act 1842

The Treason Act 1842 (5 & 6 Vict. c.51) is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It was passed early in the reign of Queen Victoria. The last person to be convicted under the Act was Marcus Sarjeant in 198 ...