Hibbertopterus on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Hibbertopterus'' is a genus of

Discerning the Diets of Sweep-Feeding Eurypterids Through Analyses of Mesh-Modified Appendage Armature

. ''Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports''. 3890. The features of fossils associated with these genera suggest that the sweep-feeding strategy of ''Hibbertopterus'' changed significantly over the course of its life, from simpler raking organs present in younger specimens to specialised comb-like organs capable of trapping prey (rather than simply pushing it towards the mouth) in adults.

Like other known hibbertopterid

Like other known hibbertopterid  The forward-facing appendages (limbs) of ''Hibbertopterus'' (pairs 2, 3 and 4) were specialised for gathering food. The distal podomeres (leg segments) of these three pairs of limbs were covered with long spines, and the end of each limb was covered with sensory organs. These adaptations suggest that ''Hibbertopterus'', like other hibbertopterids, would have fed by a method referred to as sweep-feeding, using its limbs to sweep through the substrate of its environment in search for food. The fourth pair of appendages, though used in feeding like the second and third pairs, was also used for locomotion and the two final pairs of legs (pairs five and six overall) were solely locomotory. As such, ''Hibbertopterus'' would have used a

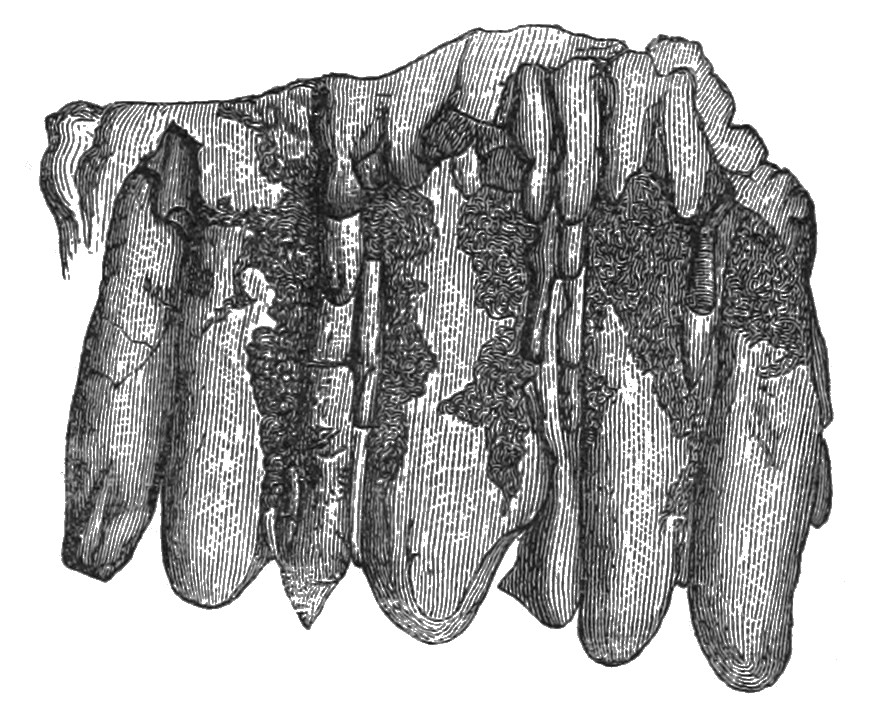

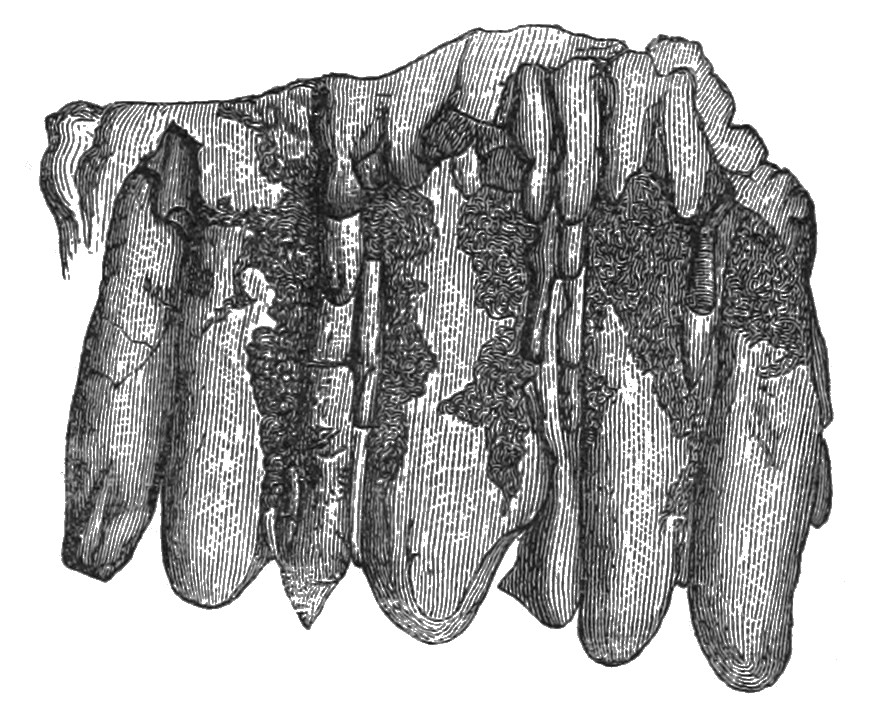

The forward-facing appendages (limbs) of ''Hibbertopterus'' (pairs 2, 3 and 4) were specialised for gathering food. The distal podomeres (leg segments) of these three pairs of limbs were covered with long spines, and the end of each limb was covered with sensory organs. These adaptations suggest that ''Hibbertopterus'', like other hibbertopterids, would have fed by a method referred to as sweep-feeding, using its limbs to sweep through the substrate of its environment in search for food. The fourth pair of appendages, though used in feeding like the second and third pairs, was also used for locomotion and the two final pairs of legs (pairs five and six overall) were solely locomotory. As such, ''Hibbertopterus'' would have used a

"Eurypterids from the Viséan of East Kirkton, West Lothian, Scotland"

''Earth and Environmental Science Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh''. 84 (3-4): 301–308. doi: 10.1017/S0263593300006118.

A summary list of fossil spiders and their relatives

In World Spider Catalog. Natural History Museum Bern by German paleontologists Jason A. Dunlop and Denise Jekel and British paleontologist David Penney and size- and temporal ranges follow a 2009 study by American paleontologists James Lamsdell and Simon J. Braddy unless otherwise noted. The distinguishing features of ''H. caledonicus'', ''H. dewalquei'', ''H. ostraviensis'' and ''H. peachi'' follow the 1968 description of these species. The descriptors, Norwegian paleontologist Leif Størmer and British paleontologist Charles D. Waterston, did not consider these species to represent eurypterids, though any emended diagnosis of them is yet to be published.

In 1831, Scottish naturalist John Scouler described the remains, consisting of a massive and unusual

In 1831, Scottish naturalist John Scouler described the remains, consisting of a massive and unusual  Though only represented by two small, jointed and vaguely cylindrical fossil fragments (both discovered in the Portage sandstones of

Though only represented by two small, jointed and vaguely cylindrical fossil fragments (both discovered in the Portage sandstones of

''Hibbertopterus'' is classified as part of the family Hibbertopteridae, which it also lends its name to, a family of eurypterids within the superfamily Mycteropoidea, alongside the genera ''Campylocephalus'' and ''Vernonopterus''. The hibbertopterids are united as a group by being large mycteropoids with broad prosomas, a hastate telson similar to that of ''Hibbertopterus'', ornamentation consisting of scales or other similar structures on the exoskeleton, the fourth pair of appendages possessing spines, the more posterior tergites of the abdomen possessing tongue-shaped scales near their edges and there being lobes positioned poterolaterally (posteriorly on both sides) on the prosoma. Historically, the morphology of ''Hibbertopterus'' and the other hibbertopterids has been seen as so unusual that they have been thought to be an order separate from

''Hibbertopterus'' is classified as part of the family Hibbertopteridae, which it also lends its name to, a family of eurypterids within the superfamily Mycteropoidea, alongside the genera ''Campylocephalus'' and ''Vernonopterus''. The hibbertopterids are united as a group by being large mycteropoids with broad prosomas, a hastate telson similar to that of ''Hibbertopterus'', ornamentation consisting of scales or other similar structures on the exoskeleton, the fourth pair of appendages possessing spines, the more posterior tergites of the abdomen possessing tongue-shaped scales near their edges and there being lobes positioned poterolaterally (posteriorly on both sides) on the prosoma. Historically, the morphology of ''Hibbertopterus'' and the other hibbertopterids has been seen as so unusual that they have been thought to be an order separate from

Many analyses and overviews treat the ten species assigned to ''Hibbertopterus'' as composing three separate, but closely related, hibbertopterid genera. In these arrangements, ''Hibbertopterus'' is typically restricted to the species ''H. scouleri'' and ''H. hibernicus'', with the species ''H. stevensoni'' being the type and only species of the genus ''Dunsopterus'' and the species ''H. caledonicus'', ''H. dewalquei'', ''H. dicki'', ''H. ostraviensis'', ''H. peachi'' and ''H. wittebergensis'' being referred to the genus ''Cyrtoctenus'' (where ''H. peachi'' is the type species).

The idea that ''Dunsopterus'' and ''Cyrtoctenus'' were congeneric (e.g. synonymous) was first suggested by British geologist Charles D. Waterston in 1985. ''Dunsopterus'' is known from very fragmentary material, mainly

Many analyses and overviews treat the ten species assigned to ''Hibbertopterus'' as composing three separate, but closely related, hibbertopterid genera. In these arrangements, ''Hibbertopterus'' is typically restricted to the species ''H. scouleri'' and ''H. hibernicus'', with the species ''H. stevensoni'' being the type and only species of the genus ''Dunsopterus'' and the species ''H. caledonicus'', ''H. dewalquei'', ''H. dicki'', ''H. ostraviensis'', ''H. peachi'' and ''H. wittebergensis'' being referred to the genus ''Cyrtoctenus'' (where ''H. peachi'' is the type species).

The idea that ''Dunsopterus'' and ''Cyrtoctenus'' were congeneric (e.g. synonymous) was first suggested by British geologist Charles D. Waterston in 1985. ''Dunsopterus'' is known from very fragmentary material, mainly  Fossil specimens of ''Hibbertopterus'' frequently occur together with fragments referred to ''Cyrtoctenus'', ''Dunsopterus'' and ''Vernonopterus''. The three fragmentary genera were suggested to by synonyms of each other by American paleontologist James Lamsdell in 2010, which would have meant the oldest name, ''Dunsopterus'', taking priority and subsuming both ''Cyrtoctenus'' and ''Vernonopterus'' as junior synonyms. Following studies on the ontogeny of '' Drepanopterus'', a more primitid mycteropoid eurypterid, large-scale changes in the developments of the appendages over the course of the life of a single animal have been proven to have happened in some eurypterids. One of the key features distinguishing ''Cyrtoctenus'' from ''Hibbertopterus'' is the presence of grooves on its podomeres, which studies on ''Drepanopterus'' suggest might have been a feature which appeared late in an animal's life cycle. Differences in the positions of the eyes in specimens of ''Hibbertopterus'' and ''Cyrtoctenus'' is not surprising as movements of the eyes through ontogeny has been described in other eurypterid genera. Lamsdell considered it almost certain that ''Dunsopterus'' was a junior synonym of ''Hibbertopterus'' and that ''Cyrtoctenus'' and ''Vernonopterus'' in turn represented junior synonyms of ''Dunsopterus'', which would subsume all three into ''Hibbertopterus''. Synonymizing ''Hibbertopterus'' with ''Cyrtoctenus'' and ''Dunsopterus'' would also explain why smaller ''Hibbertopterus'' specimens are more complete than the known fossil remains of ''Cyrtoctenus'', often fragmentary. The majority of ''Hibbertopterus'' specimens would then represent exuviae whilst ''Cyrtoctenus'' specimens represent the actual mortalities, susceptible to scavengers.

In a 2019 graduate thesis, American geologist Emily Hughes suggested the synonymization of ''Hibbertopterus'' and ''Dunsopterus'' due to the "strong morphological similarities" between them, and as ''Dunsopterus'' was found to be paraphyletic in regards to ''Cyrtoctenus'', all three were subsumed into just ''Hibbertopterus''. In particular, she noted that though the feeding appendages were different, the ornamentation and form of the raking tools seen in ''Hibbertopterus'' were probably the precursors of the more moveable finger-like organs present in ''Cyrtoctenus''. Hughes suggested that ''Vernonopterus'', due to its distinct ornamentation, represented a genus distinct from ''Hibbertopterus''. The same conclusions and suggestions were also published in a later 2020 conference abstract, co-authored by Hughes and James Lamsdell.

Fossil specimens of ''Hibbertopterus'' frequently occur together with fragments referred to ''Cyrtoctenus'', ''Dunsopterus'' and ''Vernonopterus''. The three fragmentary genera were suggested to by synonyms of each other by American paleontologist James Lamsdell in 2010, which would have meant the oldest name, ''Dunsopterus'', taking priority and subsuming both ''Cyrtoctenus'' and ''Vernonopterus'' as junior synonyms. Following studies on the ontogeny of '' Drepanopterus'', a more primitid mycteropoid eurypterid, large-scale changes in the developments of the appendages over the course of the life of a single animal have been proven to have happened in some eurypterids. One of the key features distinguishing ''Cyrtoctenus'' from ''Hibbertopterus'' is the presence of grooves on its podomeres, which studies on ''Drepanopterus'' suggest might have been a feature which appeared late in an animal's life cycle. Differences in the positions of the eyes in specimens of ''Hibbertopterus'' and ''Cyrtoctenus'' is not surprising as movements of the eyes through ontogeny has been described in other eurypterid genera. Lamsdell considered it almost certain that ''Dunsopterus'' was a junior synonym of ''Hibbertopterus'' and that ''Cyrtoctenus'' and ''Vernonopterus'' in turn represented junior synonyms of ''Dunsopterus'', which would subsume all three into ''Hibbertopterus''. Synonymizing ''Hibbertopterus'' with ''Cyrtoctenus'' and ''Dunsopterus'' would also explain why smaller ''Hibbertopterus'' specimens are more complete than the known fossil remains of ''Cyrtoctenus'', often fragmentary. The majority of ''Hibbertopterus'' specimens would then represent exuviae whilst ''Cyrtoctenus'' specimens represent the actual mortalities, susceptible to scavengers.

In a 2019 graduate thesis, American geologist Emily Hughes suggested the synonymization of ''Hibbertopterus'' and ''Dunsopterus'' due to the "strong morphological similarities" between them, and as ''Dunsopterus'' was found to be paraphyletic in regards to ''Cyrtoctenus'', all three were subsumed into just ''Hibbertopterus''. In particular, she noted that though the feeding appendages were different, the ornamentation and form of the raking tools seen in ''Hibbertopterus'' were probably the precursors of the more moveable finger-like organs present in ''Cyrtoctenus''. Hughes suggested that ''Vernonopterus'', due to its distinct ornamentation, represented a genus distinct from ''Hibbertopterus''. The same conclusions and suggestions were also published in a later 2020 conference abstract, co-authored by Hughes and James Lamsdell.

eurypterid

Eurypterids, often informally called sea scorpions, are a group of extinct arthropods that form the order Eurypterida. The earliest known eurypterids date to the Darriwilian stage of the Ordovician period 467.3 million years ago. The group is l ...

, a group of extinct aquatic arthropod

Arthropods (, (gen. ποδός)) are invertebrate animals with an exoskeleton, a segmented body, and paired jointed appendages. Arthropods form the phylum Arthropoda. They are distinguished by their jointed limbs and cuticle made of chiti ...

s. Fossils of ''Hibbertopterus'' have been discovered in deposits ranging from the Devonian period in Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to th ...

, Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a Anglo-Scottish border, border with England to the southeast ...

and the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

to the Carboniferous period in Scotland, Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

, the Czech Republic

The Czech Republic, or simply Czechia, is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Historically known as Bohemia, it is bordered by Austria to the south, Germany to the west, Poland to the northeast, and Slovakia to the southeast. The ...

and South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the Southern Africa, southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the Atlantic Ocean, South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the ...

. The type species, ''H. scouleri'', was first named as a species of the significantly different ''Eurypterus

''Eurypterus'' ( ) is an extinct genus of eurypterid, a group of organisms commonly called "sea scorpions". The genus lived during the Silurian period, from around 432 to 418 million years ago. ''Eurypterus'' is by far the most well-studied and ...

'' by Samuel Hibbert in 1836. The generic name ''Hibbertopterus'', coined more than a century later, combines his name and the Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

word πτερόν (''pteron'') meaning "wing".

''Hibbertopterus'' was the largest eurypterid within the stylonurine suborder, with the largest fossil specimens suggesting that ''H. scouleri'' could reach lengths around 180–200 centimetres (5.9–6.6 ft). Though this is significantly smaller than the largest eurypterid overall, ''Jaekelopterus

''Jaekelopterus'' is a genus of predatory eurypterid, a group of extinct aquatic arthropods. Fossils of ''Jaekelopterus'' have been discovered in deposits of Early Devonian age, from the Pragian and Emsian stages. There are two known species: th ...

'', which could reach lengths of around , ''Hibbertopterus'' is likely to have been the heaviest due to its broad and compact body. Furthermore, trackway evidence indicates that the South African species ''H. wittebergensis'' might have reached lengths similar to ''Jaekelopterus''.

Like many other stylonurine eurypterids, ''Hibbertopterus'' fed through a method called sweep-feeding. It used its specialised forward-facing appendages (limbs), equipped with several spines, to rake through the substrate of the environments in which it lived in search for small invertebrates to eat, which it could then push towards its mouth. Though long hypothesised, the fact that eurypterids were capable of terrestrial locomotion was definitely proven through the discovery of a fossil trackway made by ''Hibbertopterus'' in Scotland. The trackway showed that an animal measuring around had slowly lumbered across a stretch of land, dragging its telson

The telson () is the posterior-most division of the body of an arthropod. Depending on the definition, the telson is either considered to be the final segment of the arthropod body, or an additional division that is not a true segment on accou ...

(the posteriormost division of its body) across the ground after it. How ''Hibbertopterus'' could survive on land, however briefly, is unknown but it might have been possible through either its gills being able to function in air as long as they were wet or by the animal possessing a dual respiratory system

The respiratory system (also respiratory apparatus, ventilatory system) is a biological system consisting of specific organs and structures used for gas exchange in animals and plants. The anatomy and physiology that make this happen varies ...

, theorised to have been present in at least some eurypterids.

Though sometimes, and often historically, treated as distinct genera, the hibbertopterid eurypterids ''Cyrtoctenus'' and ''Dunsopterus'' have been suggested to represent adult ontogenetic stages of ''Hibbertopterus''.Hughes, Emily Samantha (2019),Discerning the Diets of Sweep-Feeding Eurypterids Through Analyses of Mesh-Modified Appendage Armature

. ''Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports''. 3890. The features of fossils associated with these genera suggest that the sweep-feeding strategy of ''Hibbertopterus'' changed significantly over the course of its life, from simpler raking organs present in younger specimens to specialised comb-like organs capable of trapping prey (rather than simply pushing it towards the mouth) in adults.

Description

Like other known hibbertopterid

Like other known hibbertopterid eurypterid

Eurypterids, often informally called sea scorpions, are a group of extinct arthropods that form the order Eurypterida. The earliest known eurypterids date to the Darriwilian stage of the Ordovician period 467.3 million years ago. The group is l ...

s, ''Hibbertopterus'' was a large, broad-bodied and heavy animal. It was the largest known eurypterid of the suborder Stylonurina

Stylonurina is one of two suborders of eurypterids, a group of extinct arthropods commonly known as "sea scorpions". Members of the suborder are collectively and informally known as "stylonurine eurypterids" or "stylonurines". They are known from ...

, composed of those eurypterids that lacked swimming paddles. A carapace (the part of the exoskeleton

An exoskeleton (from Greek ''éxō'' "outer" and ''skeletós'' "skeleton") is an external skeleton that supports and protects an animal's body, in contrast to an internal skeleton (endoskeleton) in for example, a human. In usage, some of the ...

which covered the head) referred to the species ''H. scouleri'', from Carboniferous Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a Anglo-Scottish border, border with England to the southeast ...

, measures wide. Since ''Hibbertopterus'' was unusually wide relative to its length for a eurypterid, the animal in question would probably have measured around 180–200 centimetres (5.9–6.6 ft) in length. Even though there were eurypterids of greater length (such as ''Jaekelopterus

''Jaekelopterus'' is a genus of predatory eurypterid, a group of extinct aquatic arthropods. Fossils of ''Jaekelopterus'' have been discovered in deposits of Early Devonian age, from the Pragian and Emsian stages. There are two known species: th ...

'' and '' Carcinosoma''), ''Hibbertopterus'' was very deep-bodied and compact in comparison to other eurypterids and the mass of the specimen in question would likely have rivalled that of other giant eurypterids (and other giant arthropods), if not surpassed them. In addition to fossil finds of large specimens, fossil trackways attributed to the species ''H. wittebergensis'' from South Africa indicates an animal around in length (the same size attributed to the largest known eurypterid, ''Jaekelopterus''), though the largest known fossil specimens of the species only appear to have reached lengths of .

hexapoda

The subphylum Hexapoda (from Greek for 'six legs') comprises most species of arthropods and includes the insects as well as three much smaller groups of wingless arthropods: Collembola, Protura, and Diplura (all of these were once considered ins ...

l (six-legged) gait.

Although not enough fossil material is known of the other hibbertopterid eurypterids to discuss the differences between them with full confidence, ''Hibbertopterus'' is defined based on a collection of definite characteristics. The telson

The telson () is the posterior-most division of the body of an arthropod. Depending on the definition, the telson is either considered to be the final segment of the arthropod body, or an additional division that is not a true segment on accou ...

(the posteriormost division of the body) was hastate (e.g. shaped like a ''gladius

''Gladius'' () is a Latin word meaning "sword" (of any type), but in its narrow sense it refers to the sword of ancient Roman foot soldiers. Early ancient Roman swords were similar to those of the Greeks, called '' xiphe'' (plural; singular ''xi ...

'', a Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lette ...

sword) and had a keel running down the middle, with in turn had a small indentation in its own centre. The walking legs of ''Hibbertopterus'' had extensions at their base and lacked longitudinal posterior grooves in all of its podomeres (leg segments).Jeram, Andrew J.; Selden, Paul A. (1993)"Eurypterids from the Viséan of East Kirkton, West Lothian, Scotland"

''Earth and Environmental Science Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh''. 84 (3-4): 301–308. doi: 10.1017/S0263593300006118.

ISSN

An International Standard Serial Number (ISSN) is an eight-digit serial number used to uniquely identify a serial publication, such as a magazine. The ISSN is especially helpful in distinguishing between serials with the same title. ISSNs ...

1755-6929. Some of these characteristics, in particular the shape of the telson, are thought to have been shared by other hibbertopterids, which are much less well preserved than ''Hibbertopterus'' itself.

Table of species

The status of the 10 species listed below follow a 2018 surveyDunlop, J. A., Penney, D. & Jekel, D. 2018A summary list of fossil spiders and their relatives

In World Spider Catalog. Natural History Museum Bern by German paleontologists Jason A. Dunlop and Denise Jekel and British paleontologist David Penney and size- and temporal ranges follow a 2009 study by American paleontologists James Lamsdell and Simon J. Braddy unless otherwise noted. The distinguishing features of ''H. caledonicus'', ''H. dewalquei'', ''H. ostraviensis'' and ''H. peachi'' follow the 1968 description of these species. The descriptors, Norwegian paleontologist Leif Størmer and British paleontologist Charles D. Waterston, did not consider these species to represent eurypterids, though any emended diagnosis of them is yet to be published.

History of research

In 1831, Scottish naturalist John Scouler described the remains, consisting of a massive and unusual

In 1831, Scottish naturalist John Scouler described the remains, consisting of a massive and unusual prosoma

The cephalothorax, also called prosoma in some groups, is a tagma of various arthropods, comprising the head and the thorax fused together, as distinct from the abdomen behind. (The terms ''prosoma'' and ''opisthosoma'' are equivalent to ''cepha ...

(head) and several tergites

A ''tergum'' (Latin for "the back"; plural ''terga'', associated adjective tergal) is the dorsal ('upper') portion of an arthropod segment other than the head. The anterior edge is called the 'base' and posterior edge is called the 'apex' or 'mar ...

(segments from the back of the animal), of a large and strange arthropod discovered in deposits in Scotland of Lower Carboniferous age, but did not assign a name to the fossils. Through Scouler's examination, the fossils represent the second eurypterid to be scientifically studied, just six years after the 1825 description of ''Eurypterus

''Eurypterus'' ( ) is an extinct genus of eurypterid, a group of organisms commonly called "sea scorpions". The genus lived during the Silurian period, from around 432 to 418 million years ago. ''Eurypterus'' is by far the most well-studied and ...

'' itself. Five years later, in 1836, British geologist Samuel Hibbert redescribed the same fossil specimens, giving them the name ''Eurypterus scouleri''.

The eurypterid genus ''Glyptoscorpius'' was named by British geologist Ben Peach

Benjamin Neeve Peach (6 September 1842 – 29 January 1926) was a British geologist.

Life

Peach was born at Gorran Haven in Cornwall on 6 September 1842 to Jemima Mabson and Charles William Peach, an amateur British naturalist and geologist ...

, who also named the species ''G. perornatus'' (treated as the type species of ''Glyptoscorpius'' by later researchers although it had not originally been designated as such) in 1882. The genus was based on ''G. perornatus'' and the fragmentary species ''G. caledonicus'', previously described as the plant ''Cycadites caledonicus'' by English paleontologist John William Salter in 1863. This designation was reinforced with more fossil fragments discovered in the Coomsdon Burn, which Peach referred to ''Glyptoscorpius caledonicus''. In 1887 Peach described ''G. minutisculptus'' from Mount Vernon

Mount Vernon is an American landmark and former plantation of Founding Father, commander of the Continental Army in the Revolutionary War, and the first president of the United States George Washington and his wife, Martha. The estate is on ...

, Glasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated popul ...

, and ''G. kidstoni'' from Radstock

Radstock is a town and civil parish on the northern slope of the Mendip Hills in Somerset, England, about south-west of Bath and north-west of Frome. It is within the area of the unitary authority of Bath and North East Somerset. The Radstoc ...

in Somerset

( en, All The People of Somerset)

, locator_map =

, coordinates =

, region = South West England

, established_date = Ancient

, established_by =

, preceded_by =

, origin =

, lord_lieutenant_office =Lord Lieutenant of Somerset

, lord_ ...

. Peach's ''Glyptoscorpius'' is highly problematic; some of the diagnostic characteristics used when describing it are either questionable or outright meaningless. For instance, the original description had been based on ''G. caledonicus'' and ''G. perornatus'' but since the parts of the body preserved in the fossils described don't completely overlap it is impossible to say if Peach's diagnostic characteristics actually apply to the two original species.

Though only represented by two small, jointed and vaguely cylindrical fossil fragments (both discovered in the Portage sandstones of

Though only represented by two small, jointed and vaguely cylindrical fossil fragments (both discovered in the Portage sandstones of Italy, New York

Italy is a town located in Yates County, New York, United States. As of the 2010 census, the town had a total population of 1,141. The town takes its name from the country of Italy.

The Town of Italy is in the southwestern part of the county and ...

), the species today recognised as ''H. wrightianus'' has had a complicated taxonomic history. Originally described in 1881 as a species of plant, the fragmentary fossil referred to as "'' Equisetides wrightiana''" was noted to represent the fossil remains of a eurypterid by American paleontologist James Hall in 1884, three years later. Though Hall assigned the species to ''Stylonurus'', that same year British paleontologists Henry Woodward and Thomas Rupert Jones assigned the fossil to the genus '' Echinocaris'', believing the fossils represented a phyllocarid

Phyllocarida is a subclass of crustacean

Crustaceans (Crustacea, ) form a large, diverse arthropod taxon which includes such animals as decapoda, decapods, ostracoda, seed shrimp, branchiopoda, branchiopods, argulidae, fish lice, krill, remipe ...

crustacean

Crustaceans (Crustacea, ) form a large, diverse arthropod taxon which includes such animals as decapods, seed shrimp, branchiopods, fish lice, krill, remipedes, isopods, barnacles, copepods, amphipods and mantis shrimp. The crustacean group can ...

. The assignment to ''Echinocaris'' was probably based on the slightly spinose surface of the fossils, but in 1888 Hall and American paleontologist John Mason Clarke pointed out that no described ''Echinocaris'' actually had spines similar to what Woodward and Jones suggested and as such, reassigned the species back to ''Stylonurus'', interpreting the fossils as fragments of the long walking legs. An assignment to ''Stylonurus'' was affirmed by Clarke and American paleontologist Rudolf Ruedemann in their influential ''The Eurypterida of New York'' in 1912, though no distinguishing features of the fossils were given due to their fragmentary nature.

Though no specification was given as to why, ''Pterygotus hibernicus'' (a species described from Ireland by British paleontologist William Hellier Baily

William Hellier Baily (7 July 18196 August 1888) was an English palaeontologist. His uncle was E.H. Baily, a sculptor. William Hellier Baily was born at Bristol on 7 July 1819.

From 1837 to 1844 he was Assistant Curator in the Bristol Muse ...

in 1872) was reassigned to ''Hibbertopterus'' by American paleontologist Erik N. Kjellesvig-Waering in 1964 as part of a greater re-examination of the various species assigned to the family Pterygotidae. Kjellesvig-Waering retained ''P. dicki'' as part of ''Pterygotus''. Scottish paleontologists Lyall I. Anderson and Nigel H. Trewin and German paleontologist Jason A. Dunlop noted in 2000 that Kjellesvig-Waerings acception of the original designation for ''Pterygotus dicki'' was "burdensome" as it is based on highly fragmentary material. They noted that like many other pterygotid species, ''P. dicki'' represented yet another name applied to some scattered segments, a practice they deemed "taxonomically unsound". Though they suggested that further research was required to determine whether or not the taxon was valid at all, they did note that the presence of a fringe to the segments formed by their ornamentation was absent in all other species of ''Pterygotus'', but "strikingly similar" to what was present in ''Cyrtoctenus''. Subsequent research treated ''P. dicki'' as a species of ''Cyrtoctenus''.

When Kjellesvig-Waering designated the genus ''Hibbertopterus'' in 1959, ''Eurypterus scouleri'' had already been referred to (considered a species of) the related '' Campylocephalus'' for some time. Kjellesvig-Waering recognised ''Campylocephalus scouleri'' as distinct from the type species of that genus, ''C. oculatus'', in that the prosoma of ''Campylocephalus'' was more narrow, had a subelliptical (almost elliptical) shape and had its widest point in the middle rather than at the base. Further differences were noted in the position and shape of the animal's compound eyes, which in ''Hibbertopterus'' are surrounded by a ring-like shape of hardened integument (absent in ''Campylocephalus''). The eyes of ''Hibbertopterus'' are also located near the center of the head whereas those of ''Campylocephalus'' are located further back. The generic name ''Hibbertopterus'' was selected to honor the original descriptor of ''H. scouleri'', Samuel Hibbert.The fact that ''Glyptoscorpius'' was questionable at best and that its type species, ''G. perornatus'', (and other species, such as ''G. kidstoni'') had recently been referred to the genus ''Adelophthalmus

''Adelophthalmus'' is a genus of eurypterid, an extinct group of aquatic arthropods. Fossils of ''Adelophthalmus'' have been discovered in deposits ranging in age from the Early Devonian to the Early Permian, which makes it the longest lived of ...

'' prompted Norwegian paleontologist Leif Størmer and British paleontologist Charles D. Waterston to in 1968 re-examine the various species that had been referred to it. Because ''G. perornatus'' was the type species of ''Glyptoscorpius'', the genus itself became synonymous with ''Adelophthalmus''. That same year, the species ''G. minutisculptus'' had been designated the type species of a distinct eurypterid genus, '' Vernonopterus''. Størmer and Waterston concluded that the ''Glyptoscorpius'' species ''G. caledonicus'' was to be part of a new genus, which they named ''Cyrtoctenus'' (the name deriving from the Greek ''Cyrtoctenos'', a curved comb) and they named a new species, ''C. peachi'' (named in honour of Ben Peach), as its type. Both of these species were based on fragmentary fossil remains. Furthermore, the species ''G. stevensoni'', named in 1936, was referred to the new genus ''Dunsopterus''. The key diagnostic feature of ''Cyrtoctenus'' was its comb-like first appendages. Waterston remarked in another 1968 paper that the "controversial" ''Stylonurus wrightianus'' was similar to the unusual and massive prosomal appendage of ''Dunsopterus'' and as such reassigned ''S. wrightianus'' to ''Dunsopterus'', creating ''Dunsopterus wrightianus''.

Other than ''C. peachi'' and ''C. caledonicus'', further species were added to ''Cyrtoctenus'' by Størmer and Waterston; ''Eurypterus dewalquei'', described in 1889, and '' Ctenopterus ostraviensis'', described in 1951, became ''Cyrtoctenus dewalquei'' and ''C. ostraviensis'', respectively. Despite noting the presence of eurypterid-type tergites, Størmer and Waterston thought that the ''Cyrtoctenus'' fossils represented remains of a new order of aquatic arthropods which they dubbed "Cyrtoctenida". The species ''C. dewalquei'' had originally been described as the fragmentary remains of a eurypterid in 1889 was assigned to ''Cyrtoctenus'' on the basis of the perceived filaments present on its appendages, similar to those of ''C. peachi''. Størmer and Waterston disregarded specimens referred to ''C. caledonicus'' other than the unique fragmentary type specimen, which at this point had been plastically preserved in sandstone. Like ''C. caledonicus'', ''C. ostraviensis'' was also known only from a single specimen, a fragment of an appendage described in 1951. No distinguishing features were given for the species, and the authors noted that it was possibly synonymous with ''C. peachi'', but they chose to maintain it as distinct due to the very limited fossil material.

Known from a single specimen described in 1985, ''H. wittebergensis'' (described as ''Cyrtoctenus wittebergensis'') is the only species of ''Hibbertopterus'' known from reasonably complete remains other than the type species itself. The fossil, discovered in the Waaipoort Formation near Klaarstroom, Cape Province

The Province of the Cape of Good Hope ( af, Provinsie Kaap die Goeie Hoop), commonly referred to as the Cape Province ( af, Kaapprovinsie) and colloquially as The Cape ( af, Die Kaap), was a province in the Union of South Africa and subsequen ...

, South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the Southern Africa, southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the Atlantic Ocean, South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the ...

, is remarkably complete, preserving not only the prosoma, the telson and several tergites, but also coxae and even part of the digestive system. The discovery was also important for eurypterid research in general, since it represents one of the few eurypterids known from the southern hemisphere, where eurypterid finds are rare and usually fragmentary. The presence of the gut in the fossil proves that the specimen represents a dead individual, and not only exuviae

In biology, exuviae are the remains of an exoskeleton and related structures that are left after ecdysozoans (including insects, crustaceans and arachnids) have moulted. The exuviae of an animal can be important to biologists as they can often b ...

, and scientists examining it could conclude that it had been preserved as lying on its back. The description of ''H. wittebergensis'' affirmed that the "cyrtoctenids" were definitely ''Hibbertopterus''-type eurypterids, not representatives of a new order of arthropods.

Classification

''Hibbertopterus'' is classified as part of the family Hibbertopteridae, which it also lends its name to, a family of eurypterids within the superfamily Mycteropoidea, alongside the genera ''Campylocephalus'' and ''Vernonopterus''. The hibbertopterids are united as a group by being large mycteropoids with broad prosomas, a hastate telson similar to that of ''Hibbertopterus'', ornamentation consisting of scales or other similar structures on the exoskeleton, the fourth pair of appendages possessing spines, the more posterior tergites of the abdomen possessing tongue-shaped scales near their edges and there being lobes positioned poterolaterally (posteriorly on both sides) on the prosoma. Historically, the morphology of ''Hibbertopterus'' and the other hibbertopterids has been seen as so unusual that they have been thought to be an order separate from

''Hibbertopterus'' is classified as part of the family Hibbertopteridae, which it also lends its name to, a family of eurypterids within the superfamily Mycteropoidea, alongside the genera ''Campylocephalus'' and ''Vernonopterus''. The hibbertopterids are united as a group by being large mycteropoids with broad prosomas, a hastate telson similar to that of ''Hibbertopterus'', ornamentation consisting of scales or other similar structures on the exoskeleton, the fourth pair of appendages possessing spines, the more posterior tergites of the abdomen possessing tongue-shaped scales near their edges and there being lobes positioned poterolaterally (posteriorly on both sides) on the prosoma. Historically, the morphology of ''Hibbertopterus'' and the other hibbertopterids has been seen as so unusual that they have been thought to be an order separate from Eurypterida

Eurypterids, often informally called sea scorpions, are a group of extinct arthropods that form the order Eurypterida. The earliest known eurypterids date to the Darriwilian stage of the Ordovician period 467.3 million years ago. The group is l ...

.

The features of ''Campylocephalus'' and ''Vernonopterus'' makes it clear that both genera represent hibbertopterid eurypterids, but the incomplete nature of all fossil specimens referred to them make any further study of the precise phylogenetic

In biology, phylogenetics (; from Greek φυλή/ φῦλον [] "tribe, clan, race", and wikt:γενετικός, γενετικός [] "origin, source, birth") is the study of the evolutionary history and relationships among or within groups o ...

relationships within the Hibbertopteridae difficult. Both genera could even represent synonyms of ''Hibbertopterus'' itself, though the highly incomplete nature of their remains again makes that hypothesis impossible to confirm.

The cladogram below is adapted from Lamsdell (2012), collapsed to only show the superfamily Mycteropoidea.

''Cyrtoctenus'' and ''Dunsopterus''

Many analyses and overviews treat the ten species assigned to ''Hibbertopterus'' as composing three separate, but closely related, hibbertopterid genera. In these arrangements, ''Hibbertopterus'' is typically restricted to the species ''H. scouleri'' and ''H. hibernicus'', with the species ''H. stevensoni'' being the type and only species of the genus ''Dunsopterus'' and the species ''H. caledonicus'', ''H. dewalquei'', ''H. dicki'', ''H. ostraviensis'', ''H. peachi'' and ''H. wittebergensis'' being referred to the genus ''Cyrtoctenus'' (where ''H. peachi'' is the type species).

The idea that ''Dunsopterus'' and ''Cyrtoctenus'' were congeneric (e.g. synonymous) was first suggested by British geologist Charles D. Waterston in 1985. ''Dunsopterus'' is known from very fragmentary material, mainly

Many analyses and overviews treat the ten species assigned to ''Hibbertopterus'' as composing three separate, but closely related, hibbertopterid genera. In these arrangements, ''Hibbertopterus'' is typically restricted to the species ''H. scouleri'' and ''H. hibernicus'', with the species ''H. stevensoni'' being the type and only species of the genus ''Dunsopterus'' and the species ''H. caledonicus'', ''H. dewalquei'', ''H. dicki'', ''H. ostraviensis'', ''H. peachi'' and ''H. wittebergensis'' being referred to the genus ''Cyrtoctenus'' (where ''H. peachi'' is the type species).

The idea that ''Dunsopterus'' and ''Cyrtoctenus'' were congeneric (e.g. synonymous) was first suggested by British geologist Charles D. Waterston in 1985. ''Dunsopterus'' is known from very fragmentary material, mainly sclerite

A sclerite (Greek , ', meaning " hard") is a hardened body part. In various branches of biology the term is applied to various structures, but not as a rule to vertebrate anatomical features such as bones and teeth. Instead it refers most commonly ...

s (various hardened body parts) which have little diagnostic potential and are poorly known in fossils attributed to ''Cyrtoctenus''. The morphology of fossils attributed to ''Dunsopterus'' and ''Cyrtoctenus'' does suggest that they were more specialised than ''H. scouleri'', particularly in their adaptations to sweep-feeding. If valid, ''Cyrtoctenus'' would have had further adaptations towards sweep-feeding than any other hibbertopterid, with its blades modified into comb-like rachis that could entrap smaller prey or other organic food particles.

It was suggested as early as 1993 by American paleontologist Paul Selden and British paleontologist Andrew J. Jeram that these adaptations might not have been due to ''Dunsopterus'' and ''Cyrtoctenus'' representing more derived genera of hibbertopterids, but rather due to both genera perhaps representing adult forms of ''Hibbertopterus''. In this case, the development of the more specialized sweep-feeding method of ''Cyrtoctenus'' can directly be explained by the larger size of the specimens referred to ''Cyrtoctenus''. The method of ''Hibbertopterus'', which involves raking, would have become significantly less effective the larger the animal grew since a larger and larger portion of its prey would be small enough to pass between its sweep-feeding spines. Any specimen over the size of a metre (3.2 ft) which continued to feed on small invertebrates would need modified sweep-feeding appendages or would need to employ a different feeding method altogether. As such, it is more than possible that later ontogenetic stages of ''Hibbertopterus'' developed the structures seen in ''Cyrtoctenus'' to be able to continue to feed at larger body sizes.

Fossil specimens of ''Hibbertopterus'' frequently occur together with fragments referred to ''Cyrtoctenus'', ''Dunsopterus'' and ''Vernonopterus''. The three fragmentary genera were suggested to by synonyms of each other by American paleontologist James Lamsdell in 2010, which would have meant the oldest name, ''Dunsopterus'', taking priority and subsuming both ''Cyrtoctenus'' and ''Vernonopterus'' as junior synonyms. Following studies on the ontogeny of '' Drepanopterus'', a more primitid mycteropoid eurypterid, large-scale changes in the developments of the appendages over the course of the life of a single animal have been proven to have happened in some eurypterids. One of the key features distinguishing ''Cyrtoctenus'' from ''Hibbertopterus'' is the presence of grooves on its podomeres, which studies on ''Drepanopterus'' suggest might have been a feature which appeared late in an animal's life cycle. Differences in the positions of the eyes in specimens of ''Hibbertopterus'' and ''Cyrtoctenus'' is not surprising as movements of the eyes through ontogeny has been described in other eurypterid genera. Lamsdell considered it almost certain that ''Dunsopterus'' was a junior synonym of ''Hibbertopterus'' and that ''Cyrtoctenus'' and ''Vernonopterus'' in turn represented junior synonyms of ''Dunsopterus'', which would subsume all three into ''Hibbertopterus''. Synonymizing ''Hibbertopterus'' with ''Cyrtoctenus'' and ''Dunsopterus'' would also explain why smaller ''Hibbertopterus'' specimens are more complete than the known fossil remains of ''Cyrtoctenus'', often fragmentary. The majority of ''Hibbertopterus'' specimens would then represent exuviae whilst ''Cyrtoctenus'' specimens represent the actual mortalities, susceptible to scavengers.

In a 2019 graduate thesis, American geologist Emily Hughes suggested the synonymization of ''Hibbertopterus'' and ''Dunsopterus'' due to the "strong morphological similarities" between them, and as ''Dunsopterus'' was found to be paraphyletic in regards to ''Cyrtoctenus'', all three were subsumed into just ''Hibbertopterus''. In particular, she noted that though the feeding appendages were different, the ornamentation and form of the raking tools seen in ''Hibbertopterus'' were probably the precursors of the more moveable finger-like organs present in ''Cyrtoctenus''. Hughes suggested that ''Vernonopterus'', due to its distinct ornamentation, represented a genus distinct from ''Hibbertopterus''. The same conclusions and suggestions were also published in a later 2020 conference abstract, co-authored by Hughes and James Lamsdell.

Fossil specimens of ''Hibbertopterus'' frequently occur together with fragments referred to ''Cyrtoctenus'', ''Dunsopterus'' and ''Vernonopterus''. The three fragmentary genera were suggested to by synonyms of each other by American paleontologist James Lamsdell in 2010, which would have meant the oldest name, ''Dunsopterus'', taking priority and subsuming both ''Cyrtoctenus'' and ''Vernonopterus'' as junior synonyms. Following studies on the ontogeny of '' Drepanopterus'', a more primitid mycteropoid eurypterid, large-scale changes in the developments of the appendages over the course of the life of a single animal have been proven to have happened in some eurypterids. One of the key features distinguishing ''Cyrtoctenus'' from ''Hibbertopterus'' is the presence of grooves on its podomeres, which studies on ''Drepanopterus'' suggest might have been a feature which appeared late in an animal's life cycle. Differences in the positions of the eyes in specimens of ''Hibbertopterus'' and ''Cyrtoctenus'' is not surprising as movements of the eyes through ontogeny has been described in other eurypterid genera. Lamsdell considered it almost certain that ''Dunsopterus'' was a junior synonym of ''Hibbertopterus'' and that ''Cyrtoctenus'' and ''Vernonopterus'' in turn represented junior synonyms of ''Dunsopterus'', which would subsume all three into ''Hibbertopterus''. Synonymizing ''Hibbertopterus'' with ''Cyrtoctenus'' and ''Dunsopterus'' would also explain why smaller ''Hibbertopterus'' specimens are more complete than the known fossil remains of ''Cyrtoctenus'', often fragmentary. The majority of ''Hibbertopterus'' specimens would then represent exuviae whilst ''Cyrtoctenus'' specimens represent the actual mortalities, susceptible to scavengers.

In a 2019 graduate thesis, American geologist Emily Hughes suggested the synonymization of ''Hibbertopterus'' and ''Dunsopterus'' due to the "strong morphological similarities" between them, and as ''Dunsopterus'' was found to be paraphyletic in regards to ''Cyrtoctenus'', all three were subsumed into just ''Hibbertopterus''. In particular, she noted that though the feeding appendages were different, the ornamentation and form of the raking tools seen in ''Hibbertopterus'' were probably the precursors of the more moveable finger-like organs present in ''Cyrtoctenus''. Hughes suggested that ''Vernonopterus'', due to its distinct ornamentation, represented a genus distinct from ''Hibbertopterus''. The same conclusions and suggestions were also published in a later 2020 conference abstract, co-authored by Hughes and James Lamsdell.

Palaeoecology

Hibbertopterids such as ''Hibbertopterus'' were sweep-feeders, having modified spines on their forward-facing prosomal appendages that allowed them to rake through the substrate of their living environments. Though sweep-feeding was used as a strategy by many genera within the Stylonurina, it was most developed within the hibbertopterids, which possessed blades on the second, third and fourth pair of appendages. Inhabiting freshwater swamps and rivers, the diet of ''Hibbertopterus'' and other sweep-feeders was probably composed of what they could find raking through its living environment, likely primarily small invertebrates. This method of feeding is quite similar tofilter feeding

Filter feeders are a sub-group of suspension feeding animals that feed by straining suspended matter and food particles from water, typically by passing the water over a specialized filtering structure. Some animals that use this method of feedin ...

. This has led some researchers to suggest that ''Hibbertopterus'' would have been a pelagic

The pelagic zone consists of the water column of the open ocean, and can be further divided into regions by depth (as illustrated on the right). The word ''pelagic'' is derived . The pelagic zone can be thought of as an imaginary cylinder or w ...

animal, as modern filter feeding crustaceans, but the robust and massive nature of the genus (in contrast to modern filter feeding crustaceans which are typically very small) makes such a conclusion unlikely.

The chelicerae (pincers) of ''Hibbertopterus'' were weak and they would not have been able to grasp any potential prey which means ''Hibbertopterus'' would probably have been incapable of preying on larger animals. The conclusion that ''Hibbertopterus'' wasn't preying on large animals is also supported by the complete lack of adaptations towards any organs used for trapping prey in younger specimens (though they are present on adult specimens once referred to ''Cyrtoctenus'') and a lack of swimming adaptations. Through sweep-feeding, ''Hibbertopterus'' could sweep up small animals from the soft sediments of shallow bodies of water, presumably small crustaceans and other arthropods, and could then sweep them into its mouth when it detected them. Through the different adaptations of juveniles and adults ("''Cyrtoctenus''"), individuals of different ages would possibly have preferred different types of prey, which would have reduced competition between members of the same genus.

A fossil trackway discovered near St Andrews in Fife, Scotland, reveals that ''Hibbertopterus'' was capable of at least limited terrestrial locomotion

Terrestrial locomotion has evolved as animals adapted from aquatic to terrestrial environments. Locomotion on land raises different problems than that in water, with reduced friction being replaced by the increased effects of gravity.

As viewe ...

. The trackway found was roughly long and wide, and suggests that the eurypterid responsible was long, consistent with other giant sizes attributed to ''Hibbertopterus''. The tracks indicate a lumbering, jerky and dragging movement. Scarps with crescent-shapes were left by the outer limbs, inner markings were made by the keeled belly and the telson carved a central groove. The slow progression and dragging of the tail indicate that the animal responsible was moving out of water. The presence of terrestrial tracks indicate that ''Hibbertopterus'' was able to survive on land at least briefly, possible due to the probability that their gills could function in air as long as they remained wet. Additionally, some studies suggest that eurypterids possessed a dual respiratory system

The respiratory system (also respiratory apparatus, ventilatory system) is a biological system consisting of specific organs and structures used for gas exchange in animals and plants. The anatomy and physiology that make this happen varies ...

, which would allow short periods of time in terrestrial environments.

In the Midland Valley of Scotland, 27 kilometres (16.8 miles) to the west of Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian on the southern shore of t ...

, East Kirkton Quarry contains deposits that were once a freshwater lake near a volcano. The locality has preserved a diverse fauna of the Viséan age of the Carboniferous (about 335 million years ago). Other than ''H. scouleri'', the fauna includes several terrestrial animals, such as anthracosaurs, aistopods, baphetids and temnospondyls

Temnospondyli (from Greek τέμνειν, ''temnein'' 'to cut' and σπόνδυλος, ''spondylos'' 'vertebra') is a diverse order of small to giant tetrapods—often considered primitive amphibians—that flourished worldwide during the Carbo ...

, representing some of the oldest known terrestrial tetrapod

Tetrapods (; ) are four-limbed vertebrate animals constituting the superclass Tetrapoda (). It includes extant and extinct amphibians, sauropsids ( reptiles, including dinosaurs and therefore birds) and synapsids ( pelycosaurs, extinct t ...

s. Several terrestrial invertebrates are also known from the location, including several species of millipede

Millipedes are a group of arthropods that are characterised by having two pairs of jointed legs on most body segments; they are known scientifically as the class Diplopoda, the name derived from this feature. Each double-legged segment is a resu ...

s, '' Gigantoscorpio'' (one of the earliest scorpion

Scorpions are predatory arachnids of the order Scorpiones. They have eight legs, and are easily recognized by a pair of grasping pincers and a narrow, segmented tail, often carried in a characteristic forward curve over the back and always en ...

s proven to have been terrestrial) and early representatives of the Opiliones

The Opiliones (formerly Phalangida) are an order of arachnids colloquially known as harvestmen, harvesters, harvest spiders, or daddy longlegs. , over 6,650 species of harvestmen have been discovered worldwide, although the total number of ext ...

. The site also preserves abundant plant life, including the genera ''Lepidodendron

''Lepidodendron'' is an extinct genus of primitive vascular plants belonging to the family Lepidodendraceae, part of a group of Lycopodiopsida known as scale trees or arborescent lycophytes, related to quillworts and lycopsids (club mosses). Th ...

'', '' Lepidophloios'', ''Stigmaria

''Stigmaria'' is a form taxon for common fossils found in Carboniferous rocks. They represent the underground rooting structures of coal forest lycopsid trees such as '' Sigillaria'' and '' Lepidodendron''. These swamp forest trees grew to ...

'' and ''Sphenopteris

''Sphenopteris'' is a genus of seed ferns containing the foliage of various extinct plants, ranging from the Devonian to Late Cretaceous. One species, ''S. höninghausi'', was transferred to the genus '' Crossotheca'' in 1911.

Biology

The fro ...

''. Locally, the strange fossil carapaces of ''H. scouleri'' have been given the common name "Scouler's heids" ("heid" being Scots for "head").

The Waaipoort Formation, where ''H. wittebergensis'' has been discovered, also preserves a diverse Carboniferous fauna and some species of plants. Interpreted as having been a large and open fresh to brackish water lake, with possibly occasional influences by storms and glacial processes, fossil remains recovered is most commonly that of various types of fish. Among these types are palaeoniscoids, shark

Sharks are a group of elasmobranch fish characterized by a cartilaginous skeleton, five to seven gill slits on the sides of the head, and pectoral fins that are not fused to the head. Modern sharks are classified within the clade Selachi ...

s and acanthodians. Though shark material is too fragmentary to be identifiable, at least some fossils might represent the remains of protacrodontoids. Among the acanthodians, at least three genera have been identified from fossil scales and spines, including the derived climatiiform ''Gyracanthides

''Gyracanthides'' is an extinct genus of acanthodian gnathostome, known from Devonian to Early Carboniferous.

Description

''Gyracanthides'' is large acanthodian, ''G. murrayi'' reached the length up to . The pectoral fin spines are large co ...

''. Among the palaeoniscoids, eight distinct genera have been identified. Severa of these palaeoniscoid genera also occur in deposits of similar age in Scotland. Other than ''H. wittebergensis'', the only known invertebrates are two rare species of bivalves, possibly representing unionids. Plant fossils in the Waaiport Formation are notably less diverse than those of preceding ages in the same location, possibly because of climate reasons. Among the genera present are the common '' Praeramunculus'' (possibly representing a progymnosperm

The progymnosperms are an extinct group of woody, spore-bearing plants that is presumed to have evolved from the trimerophytes, and eventually gave rise to the gymnosperms, ancestral to acrogymnosperms and angiosperms (flowering plants). They ...

) and '' Archaeosigillaria'' (a small type of lycopod

Lycopodiopsida is a class of vascular plants known as lycopods, lycophytes or other terms including the component lyco-. Members of the class are also called clubmosses, firmosses, spikemosses and quillworts. They have dichotomously branching s ...

).

See also

* List of eurypterid genera * Timeline of eurypterid researchReferences