Hesiodus on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Hesiod (; grc-gre, Ἡσίοδος ''Hēsíodos'') was an ancient Greek poet generally thought to have been active between 750 and 650 BC, around the same time as

Some scholars have seen Perses as a literary creation, a foil for the moralizing that Hesiod develops in ''Works and Days'', but there are also arguments against that theory. For example, it is quite common for works of moral instruction to have an imaginative setting, as a means of getting the audience's attention,Jasper Griffin, 'Greek Myth and Hesiod' in ''The Oxford History of the Classical World'', Oxford University Press (1986), cites for example the Book of Ecclesiastes, a Sumerian text in the form of a father's remonstrance with a prodigal son, and Egyptian wisdom texts spoken by viziers, etc. Hesiod was certainly open to oriental influences, as is clear in the myths presented by him in ''Theogony''. but it could be difficult to see how Hesiod could have travelled around the countryside entertaining people with a narrative about himself if the account was known to be fictitious.

Some scholars have seen Perses as a literary creation, a foil for the moralizing that Hesiod develops in ''Works and Days'', but there are also arguments against that theory. For example, it is quite common for works of moral instruction to have an imaginative setting, as a means of getting the audience's attention,Jasper Griffin, 'Greek Myth and Hesiod' in ''The Oxford History of the Classical World'', Oxford University Press (1986), cites for example the Book of Ecclesiastes, a Sumerian text in the form of a father's remonstrance with a prodigal son, and Egyptian wisdom texts spoken by viziers, etc. Hesiod was certainly open to oriental influences, as is clear in the myths presented by him in ''Theogony''. but it could be difficult to see how Hesiod could have travelled around the countryside entertaining people with a narrative about himself if the account was known to be fictitious.  The personality behind the poems is unsuited to the kind of "aristocratic withdrawal" typical of a rhapsode but is instead "argumentative, suspicious, ironically humorous, frugal, fond of proverbs, wary of women." He was in fact a "misogynist" of the same calibre as the later poet

The personality behind the poems is unsuited to the kind of "aristocratic withdrawal" typical of a rhapsode but is instead "argumentative, suspicious, ironically humorous, frugal, fond of proverbs, wary of women." He was in fact a "misogynist" of the same calibre as the later poet

Greeks in the late 5th and early 4th centuries BC considered their oldest poets to be

Greeks in the late 5th and early 4th centuries BC considered their oldest poets to be

The ''Works and Days'' is a poem of over 800 lines which revolves around two general truths: labour is the universal lot of Man, but he who is willing to work will get by. Scholars have interpreted this work against a background of agrarian crisis in mainland

The ''Works and Days'' is a poem of over 800 lines which revolves around two general truths: labour is the universal lot of Man, but he who is willing to work will get by. Scholars have interpreted this work against a background of agrarian crisis in mainland

*The lyric poet

*The lyric poet

Hesiod employed the conventional dialect of epic verse, which was Ionian. Comparisons with Homer, a native Ionian, can be unflattering. Hesiod's handling of the dactylic hexameter was not as masterful or fluent as Homer's and one modern scholar refers to his "hobnailed hexameters". His use of language and meter in ''Works and Days'' and ''Theogony'' distinguishes him also from the author of the ''Shield of Heracles''. All three poets, for example, employed

Hesiod employed the conventional dialect of epic verse, which was Ionian. Comparisons with Homer, a native Ionian, can be unflattering. Hesiod's handling of the dactylic hexameter was not as masterful or fluent as Homer's and one modern scholar refers to his "hobnailed hexameters". His use of language and meter in ''Works and Days'' and ''Theogony'' distinguishes him also from the author of the ''Shield of Heracles''. All three poets, for example, employed

''Theatre of the Greeks''

* . * . * Evelyn-White, Hugh G. (1964), ''Hesiod, the Homeric Hymns and Homerica'' (= Loeb Classical Library, vol. 57), Harvard University Press, pp. xliii–xlvii. * Lamberton, Robert (1988)

''Hesiod''

New Haven:

''Works and Days Book 1''

Translated from the Greek by Mr. Cooke (London, 1728). A youthful exercise in Augustan heroic couplets by Thomas Cooke (1703–1756), employing the Roman names for all the gods. * Web texts taken from ''Hesiod, the Homeric Hymns and Homerica'', edited and translated by Hugh G. Evelyn-White, published as Loeb Classical Library No. 57, 1914, :

Scanned text at the Internet Archive

in Portable Document Format, PDF and DjVu format *

Perseus Classics Collection: Greek and Roman Materials: Text: Hesiod

(Greek texts and English translations for ''Works and Days'', ''

Project Gutenberg plain text

**

The Medieval and Classical Literature Library: Hesiod

**

(''Theogony'' and ''Works and Days'' only) *

Hesiod Poems and Fragments

including Ps-Hesiod works ''Astronomy'' and ''Catalogue of Women'' a

demonax.info

{{Authority control Hesiod, 8th-century BC births 8th-century BC Greek people 8th-century BC poets Ancient Boeotian poets Ancient Greek didactic poets Ancient Greek poets Ancient Greek economists Year of death unknown 8th-century BC religious leaders 7th-century BC religious leaders

Homer

Homer (; grc, Ὅμηρος , ''Hómēros'') (born ) was a Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Homer is considered one of the ...

. He is generally regarded by western authors as 'the first written poet in the Western tradition to regard himself as an individual persona with an active role to play in his subject.' Ancient authors credited Hesiod and Homer with establishing Greek religious customs. Modern scholars refer to him as a major source on Greek mythology

A major branch of classical mythology, Greek mythology is the body of myths originally told by the ancient Greeks, and a genre of Ancient Greek folklore. These stories concern the origin and nature of the world, the lives and activities ...

, farming techniques, early economic thought, archaic Greek astronomy

Astronomy () is a natural science that studies celestial objects and phenomena. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and evolution. Objects of interest include planets, moons, stars, nebulae, g ...

and ancient time-keeping.

Life

The dating of Hesiod's life is a contested issue in scholarly circles (''see § Dating below''). Epic narrative allowed poets likeHomer

Homer (; grc, Ὅμηρος , ''Hómēros'') (born ) was a Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Homer is considered one of the ...

no opportunity for personal revelations. However, Hesiod's extant work comprises several didactic poem

Didacticism is a philosophy that emphasizes instructional and informative qualities in literature, art, and design. In art, design, architecture, and landscape, didacticism is an emerging conceptual approach that is driven by the urgent need t ...

s in which he went out of his way to let his audience in on a few details of his life. There are three explicit references in ''Works and Days

''Works and Days'' ( grc, Ἔργα καὶ Ἡμέραι, Érga kaì Hēmérai)The ''Works and Days'' is sometimes called by the Latin translation of the title, ''Opera et Dies''. Common abbreviations are ''WD'' and ''Op''. for ''Opera''. is a ...

'', as well as some passages in his ''Theogony

The ''Theogony'' (, , , i.e. "the genealogy or birth of the gods") is a poem by Hesiod (8th–7th century BC) describing the origins and genealogies of the Greek gods, composed . It is written in the Epic dialect of Ancient Greek and contain ...

'', that support inferences made by scholars. The former poem says that his father came from Cyme in Aeolis

Aeolis (; grc, Αἰολίς, Aiolís), or Aeolia (; grc, Αἰολία, Aiolía, link=no), was an area that comprised the west and northwestern region of Asia Minor (modern-day Turkey), mostly along the coast, and also several offshore islan ...

(on the coast of Asia Minor

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

, a little south of the island Lesbos

Lesbos or Lesvos ( el, Λέσβος, Lésvos ) is a Greek island located in the northeastern Aegean Sea. It has an area of with approximately of coastline, making it the third largest island in Greece. It is separated from Asia Minor by the nar ...

) and crossed the sea to settle at a hamlet, near Thespiae

Thespiae ( ; grc, Θεσπιαί, Thespiaí) was an ancient Greek city (''polis'') in Boeotia. It stood on level ground commanded by the low range of hills which run eastward from the foot of Mount Helicon to Thebes, near modern Thespies.

Histo ...

in Boeotia

Boeotia ( ), sometimes Latinized as Boiotia or Beotia ( el, Βοιωτία; modern: ; ancient: ), formerly known as Cadmeis, is one of the regional units of Greece. It is part of the region of Central Greece. Its capital is Livadeia, and its ...

, named Ascra

Ascra or Askre ( grc, Ἄσκρη, Áskrē) was a town in ancient Boeotia which is best known today as the home of the poet Hesiod.W. Hazlitt (1858) ''The Classical Gazetteer'' (London)p. 54, s.v. Ascra It was located upon Mount Helicon, five miles ...

, "a cursed place, cruel in winter, hard in summer, never pleasant" (''Works'' 640). Hesiod's patrimony there, a small piece of ground at the foot of Mount Helicon

Mount Helicon ( grc, Ἑλικών; ell, Ελικώνας) is a mountain in the region of Thespiai in Boeotia, Greece, celebrated in Greek mythology. With an altitude of , it is located approximately from the north coast of the Gulf of Corint ...

, occasioned lawsuits

-

A lawsuit is a proceeding by a party or parties against another in the civil court of law. The archaic term "suit in law" is found in only a small number of laws still in effect today. The term "lawsuit" is used in reference to a civil acti ...

with his brother Perses, who seems, at first, to have cheated him of his rightful share thanks to corrupt authorities or "kings" but later became impoverished and ended up scrounging from the thrifty poet (''Works'' 35, 396).

Unlike his father, Hesiod was averse to sea travel, but he once crossed the narrow strait between the Greek mainland and Euboea

Evia (, ; el, Εύβοια ; grc, Εὔβοια ) or Euboia (, ) is the second-largest Greek island in area and population, after Crete. It is separated from Boeotia in mainland Greece by the narrow Euripus Strait (only at its narrowest poin ...

to participate in funeral celebrations for one Athamas of Chalcis, and there won a tripod

A tripod is a portable three-legged frame or stand, used as a platform for supporting the weight and maintaining the stability of some other object. The three-legged (triangular stance) design provides good stability against gravitational loads ...

in a singing competition. He also describes a meeting between himself and the Muses on Mount Helicon

Mount Helicon ( grc, Ἑλικών; ell, Ελικώνας) is a mountain in the region of Thespiai in Boeotia, Greece, celebrated in Greek mythology. With an altitude of , it is located approximately from the north coast of the Gulf of Corint ...

, where he had been pasturing sheep when the goddesses presented him with a laurel

Laurel may refer to:

Plants

* Lauraceae, the laurel family

* Laurel (plant), including a list of trees and plants known as laurel

People

* Laurel (given name), people with the given name

* Laurel (surname), people with the surname

* Laurel (mus ...

staff, a symbol of poetic authority (''Theogony'' 22–35). Fanciful though the story might seem, the account has led ancient and modern scholars to infer that he was not a professionally trained rhapsode

A rhapsode ( el, ῥαψῳδός, "rhapsōidos") or, in modern usage, rhapsodist, refers to a classical Greek professional performer of epic poetry in the fifth and fourth centuries BC (and perhaps earlier). Rhapsodes notably performed the epic ...

, or he would have been presented with a lyre instead.See discussion by M. L. West, ''Hesiod: Theogony'', Oxford University Press (1966), p. 163 f., note 30, citing for example Pausanias Pausanias ( el, Παυσανίας) may refer to:

*Pausanias of Athens, lover of the poet Agathon and a character in Plato's ''Symposium''

*Pausanias the Regent, Spartan general and regent of the 5th century BC

* Pausanias of Sicily, physician of t ...

IX, 30.3. Rhapsodes in post-Homeric times are often shown carrying either a laurel staff or a lyre but in Hesiod's earlier time, the staff seems to indicate that he was not a rhapsode, a professional minstrel

A minstrel was an entertainer, initially in medieval Europe. It originally described any type of entertainer such as a musician, juggler, acrobat, singer or fool; later, from the sixteenth century, it came to mean a specialist entertainer ...

. Meetings between poets and the Muses became part of poetic folklore: compare, for example, Archilochus' account of his meeting the Muses while leading home a cow, and the legend of Cædmon

Cædmon (; ''fl. c.'' 657 – 684) is the earliest English poet whose name is known. A Northumbrian cowherd who cared for the animals at the double monastery of Streonæshalch (now known as Whitby Abbey) during the abbacy of St. Hilda, he wa ...

.

Some scholars have seen Perses as a literary creation, a foil for the moralizing that Hesiod develops in ''Works and Days'', but there are also arguments against that theory. For example, it is quite common for works of moral instruction to have an imaginative setting, as a means of getting the audience's attention,Jasper Griffin, 'Greek Myth and Hesiod' in ''The Oxford History of the Classical World'', Oxford University Press (1986), cites for example the Book of Ecclesiastes, a Sumerian text in the form of a father's remonstrance with a prodigal son, and Egyptian wisdom texts spoken by viziers, etc. Hesiod was certainly open to oriental influences, as is clear in the myths presented by him in ''Theogony''. but it could be difficult to see how Hesiod could have travelled around the countryside entertaining people with a narrative about himself if the account was known to be fictitious.

Some scholars have seen Perses as a literary creation, a foil for the moralizing that Hesiod develops in ''Works and Days'', but there are also arguments against that theory. For example, it is quite common for works of moral instruction to have an imaginative setting, as a means of getting the audience's attention,Jasper Griffin, 'Greek Myth and Hesiod' in ''The Oxford History of the Classical World'', Oxford University Press (1986), cites for example the Book of Ecclesiastes, a Sumerian text in the form of a father's remonstrance with a prodigal son, and Egyptian wisdom texts spoken by viziers, etc. Hesiod was certainly open to oriental influences, as is clear in the myths presented by him in ''Theogony''. but it could be difficult to see how Hesiod could have travelled around the countryside entertaining people with a narrative about himself if the account was known to be fictitious. Gregory Nagy

Gregory Nagy ( hu, Nagy Gergely, ; born October 22, 1942 in Budapest)"CV: Gregory Nagy"

''gr ...

, on the other hand, sees both ''Pérsēs'' ("the destroyer" from , ''pérthō'') and ''Hēsíodos'' ("he who emits the voice" from , ''híēmi'' and , ''audḗ'') as fictitious names for poetical ''gr ...

persona

A persona (plural personae or personas), depending on the context, is the public image of one's personality, the social role that one adopts, or simply a fictional character. The word derives from Latin, where it originally referred to a theatr ...

e.

It might seem unusual that Hesiod's father migrated from Asia Minor westwards to mainland Greece, the opposite direction to most colonial movements at the time, and Hesiod himself gives no explanation for it. However around 750 BC or a little later, there was a migration of seagoing merchants from his original home in Cyme in Asia Minor to Cumae

Cumae ( grc, Κύμη, (Kumē) or or ; it, Cuma) was the first ancient Greek colony on the mainland of Italy, founded by settlers from Euboea in the 8th century BC and soon becoming one of the strongest colonies. It later became a rich Ro ...

in Campania (a colony they shared with the Euboeans), and possibly his move west had something to do with that, since Euboea

Evia (, ; el, Εύβοια ; grc, Εὔβοια ) or Euboia (, ) is the second-largest Greek island in area and population, after Crete. It is separated from Boeotia in mainland Greece by the narrow Euripus Strait (only at its narrowest poin ...

is not far from Boeotia, where he eventually established himself and his family. The family association with Aeolian Cyme might explain his familiarity with eastern myths, evident in his poems, though the Greek world might have already developed its own versions of them.A. R. Burn, ''The Pelican History of Greece'', Penguin (1966), p. 77.

In spite of Hesiod's complaints about poverty, life on his father's farm could not have been too uncomfortable if ''Works and Days'' is anything to judge by, since he describes the routines of prosperous yeoman

Yeoman is a noun originally referring either to one who owns and cultivates land or to the middle ranks of servants in an English royal or noble household. The term was first documented in mid-14th-century England. The 14th century also witn ...

ry rather than peasants. His farmer employs a friend (''Works and Days'' 370) as well as servants (502, 573, 597, 608, 766), an energetic and responsible ploughman of mature years (469 ff.), a slave boy to cover the seed (441–6), a female servant to keep house (405, 602) and working teams of oxen and mules (405, 607f.). One modern scholar surmises that Hesiod may have learned about world geography, especially the catalogue of rivers in ''Theogony'' (337–45), listening to his father's accounts of his own sea voyages as a merchant. The father probably spoke in the Aeolian dialect

In linguistics, Aeolic Greek (), also known as Aeolian (), Lesbian or Lesbic dialect, is the set of dialects of Ancient Greek spoken mainly in Boeotia; in Thessaly; in the Aegean island of Lesbos; and in the Greek colonies of Aeolis in Anatol ...

of Cyme but Hesiod probably grew up speaking the local Boeotian, belonging to the same dialect group. However, while his poetry features some Aeolisms there are no words that are certainly Boeotian. His basic language was the main literary dialect of the time, Homer's Ionian.

It is probable that Hesiod wrote his poems down, or dictated them, rather than passed them on orally, as rhapsode

A rhapsode ( el, ῥαψῳδός, "rhapsōidos") or, in modern usage, rhapsodist, refers to a classical Greek professional performer of epic poetry in the fifth and fourth centuries BC (and perhaps earlier). Rhapsodes notably performed the epic ...

s did—otherwise the pronounced personality that now emerges from the poems would surely have been diluted through oral transmission from one rhapsode to another. Pausanias Pausanias ( el, Παυσανίας) may refer to:

*Pausanias of Athens, lover of the poet Agathon and a character in Plato's ''Symposium''

*Pausanias the Regent, Spartan general and regent of the 5th century BC

* Pausanias of Sicily, physician of t ...

asserted that Boeotia

Boeotia ( ), sometimes Latinized as Boiotia or Beotia ( el, Βοιωτία; modern: ; ancient: ), formerly known as Cadmeis, is one of the regional units of Greece. It is part of the region of Central Greece. Its capital is Livadeia, and its ...

ns showed him an old tablet made of lead on which the ''Works'' were engraved. If he did write or dictate, it was perhaps as an aid to memory or because he lacked confidence in his ability to produce poems extempore, as trained rhapsodes could do. It certainly wasn't in a quest for immortal fame since poets in his era had probably no such notions for themselves. However, some scholars suspect the presence of large-scale changes in the text and attribute this to oral transmission. Possibly he composed his verses during idle times on the farm, in the spring before the May harvest or the dead of winter.

Semonides

Semonides of Amorgos (; grc-gre, Σημωνίδης ὁ Ἀμοργῖνος, variantly ; fl. 7th century BC) was a Greek iambic and elegiac poet who is believed to have lived during the seventh century BC. Fragments of his poetry survive as quo ...

. He resembles Solon

Solon ( grc-gre, Σόλων; BC) was an Athenian statesman, constitutional lawmaker and poet. He is remembered particularly for his efforts to legislate against political, economic and moral decline in Archaic Athens.Aristotle ''Politics'' ...

in his preoccupation with issues of good versus evil and "how a just and all-powerful god can allow the unjust to flourish in this life". He recalls Aristophanes

Aristophanes (; grc, Ἀριστοφάνης, ; c. 446 – c. 386 BC), son of Philippus, of the deme Kydathenaion ( la, Cydathenaeum), was a comic playwright or comedy-writer of ancient Athens and a poet of Old Attic Comedy. Eleven of his for ...

in his rejection of the idealised hero of epic literature in favour of an idealised view of the farmer. Yet the fact that he could eulogise kings in ''Theogony'' (80 ff., 430, 434) and denounce them as corrupt in ''Works and Days'' suggests that he could resemble whichever audience he composed for.

Various legends accumulated about Hesiod and they are recorded in several sources:

*the story about the '' Contest of Homer and Hesiod'';

*a '' vita'' of Hesiod by the Byzantine grammarian John Tzetzes;

*the entry for Hesiod in the '' Suda'';

*two passages and some scattered remarks in Pausanias Pausanias ( el, Παυσανίας) may refer to:

*Pausanias of Athens, lover of the poet Agathon and a character in Plato's ''Symposium''

*Pausanias the Regent, Spartan general and regent of the 5th century BC

* Pausanias of Sicily, physician of t ...

(IX, 31.3–6 and 38.3 f.);

*a passage in Plutarch

Plutarch (; grc-gre, Πλούταρχος, ''Ploútarchos''; ; – after AD 119) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for hi ...

''Moralia'' (162b).

Death

Two different—yet early—traditions record the site of Hesiod's grave. One, as early asThucydides

Thucydides (; grc, , }; BC) was an Athenian historian and general. His '' History of the Peloponnesian War'' recounts the fifth-century BC war between Sparta and Athens until the year 411 BC. Thucydides has been dubbed the father of " scienti ...

, reported in Plutarch, the '' Suda'' and John Tzetzes, states that the Delphic oracle warned Hesiod that he would die in Nemea, and so he fled to Locris

Locris (; el, label=Modern Greek, Λοκρίδα, Lokrída; grc, Λοκρίς, Lokrís) was a region of ancient Greece, the homeland of the Locrians, made up of three distinct districts.

Locrian tribe

The city of Locri in Calabria (Italy), ...

, where he was killed at the local temple to Nemean Zeus, and buried there. This tradition follows a familiar ironic

Irony (), in its broadest sense, is the juxtaposition of what on the surface appears to be the case and what is actually the case or to be expected; it is an important rhetorical device and literary technique.

Irony can be categorized into ...

convention: the oracle predicts accurately after all. The other tradition, first mentioned in an epigram by Chersias of Orchomenus written in the 7th century BC (within a century or so of Hesiod's death) claims that Hesiod lies buried at Orchomenus, a town in Boeotia. According to Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ph ...

's ''Constitution of Orchomenus,'' when the Thespians ravaged Ascra, the villagers sought refuge at Orchomenus, where, following the advice of an oracle, they collected the ashes of Hesiod and set them in a place of honour in their '' agora'', next to the tomb of Minyas, their eponymous founder. Eventually they came to regard Hesiod too as their "hearth-founder" (, ''oikistēs''). Later writers attempted to harmonize these two accounts. Yet another account taken from classical sources, cited by author Charles Abraham Elton in his ''The Remains of Hesiod the Ascræan, Including the Shield of Hercules by Hesiod'' depicts Hesiod as being falsely accused of rape by a girl's brothers and murdered in reprisal despite his advanced age while the true culprit (his Milesian fellow-traveler) managed to escape.

Dating

Orpheus

Orpheus (; Ancient Greek: Ὀρφεύς, classical pronunciation: ; french: Orphée) is a Thracian bard, legendary musician and prophet in ancient Greek religion. He was also a renowned poet and, according to the legend, travelled with J ...

, Musaeus Musaeus, Musaios ( grc, Μουσαῖος) or Musäus may refer to:

Greek poets

* Musaeus of Athens, legendary polymath, considered by the Greeks to be one of their earliest poets (mentioned by Socrates in Plato's Apology)

* Musaeus of Ephesus, liv ...

, Hesiod and Homer

Homer (; grc, Ὅμηρος , ''Hómēros'') (born ) was a Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Homer is considered one of the ...

—in that order. Thereafter, Greek writers began to consider Homer earlier than Hesiod. Devotees of Orpheus and Musaeus were probably responsible for precedence being given to their two cult heroes and maybe the Homeridae

The Homeridae ( grc, Ὁμηρίδαι) were a family, clan or professional lineage on the island of Chios claiming descent from the Greek epic poet Homer.

The origin of the name seems obvious: in classical Greek the word should mean "children o ...

were responsible in later antiquity for promoting Homer at Hesiod's expense.

The first known writers to locate Homer earlier than Hesiod were Xenophanes

Xenophanes of Colophon (; grc, Ξενοφάνης ὁ Κολοφώνιος ; c. 570 – c. 478 BC) was a Greek philosopher, theologian, poet, and critic of Homer from Ionia who travelled throughout the Greek-speaking world in early Classical ...

and Heraclides Ponticus, though Aristarchus of Samothrace

Aristarchus of Samothrace ( grc-gre, Ἀρίσταρχος ὁ Σαμόθραξ ''Aristarchos o Samothrax''; c. 220 – c. 143 BC) was an ancient Greek grammarian, noted as the most influential of all scholars of Homeric poetry. He was the h ...

was the first actually to argue the case. Ephorus

Ephorus of Cyme (; grc-gre, Ἔφορος ὁ Κυμαῖος, ''Ephoros ho Kymaios''; c. 400330 BC) was an ancient Greek historian known for his universal history.

Biography

Information on his biography is limited. He was born in Cyme, A ...

made Homer a younger cousin of Hesiod, the 5th century BC historian Herodotus

Herodotus ( ; grc, , }; BC) was an ancient Greek historian and geographer

A geographer is a physical scientist, social scientist or humanist whose area of study is geography, the study of Earth's natural environment and human society ...

(''Histories'' II, 53) evidently considered them near-contemporaries, and the 4th century BC sophist

A sophist ( el, σοφιστής, sophistes) was a teacher in ancient Greece in the fifth and fourth centuries BC. Sophists specialized in one or more subject areas, such as philosophy, rhetoric, music, athletics, and mathematics. They taught ' ...

Alcidamas in his work ''Mouseion'' even brought them together for an imagined poetic '' ágōn'' (), which survives today as the '' Contest of Homer and Hesiod''. Most scholars today agree with Homer's priority but there are good arguments on either side.

Hesiod certainly predates the lyric and elegiac The adjective ''elegiac'' has two possible meanings. First, it can refer to something of, relating to, or involving, an elegy or something that expresses similar mournfulness or sorrow. Second, it can refer more specifically to poetry composed in ...

poets whose work has come down to the modern era. Imitations of his work have been observed in Alcaeus, Epimenides

Epimenides of Cnossos (or Epimenides of Crete) (; grc-gre, Ἐπιμενίδης) was a semi-mythical 7th or 6th century BC Greek seer and philosopher-poet, from Knossos or Phaistos.

Life

While tending his father's sheep, Epimenides is said ...

, Mimnermus

Mimnermus ( grc-gre, Μίμνερμος ''Mímnermos'') was a Greek elegiac poet from either Colophon or Smyrna in Ionia, who flourished about 632–629 BC (i.e. in the 37th Olympiad, according to Suda). He was strongly influenced by the examp ...

, Semonides

Semonides of Amorgos (; grc-gre, Σημωνίδης ὁ Ἀμοργῖνος, variantly ; fl. 7th century BC) was a Greek iambic and elegiac poet who is believed to have lived during the seventh century BC. Fragments of his poetry survive as quo ...

, Tyrtaeus

Tyrtaeus (; grc-gre, Τυρταῖος ''Tyrtaios''; fl. mid-7th century BC) was a Greek elegiac poet from Sparta. He wrote at a time of two crises affecting the city: a civic unrest threatening the authority of kings and elders, later recalled i ...

and Archilochus, from which it has been inferred that the latest possible date for him is about 650 BC.

An upper limit of 750 BC is indicated by a number of considerations, such as the probability that his work was written down, the fact that he mentions a sanctuary at Delphi that was of little national significance before c. 750 BC (''Theogony'' 499), and that he lists rivers that flow into the Euxine

The Black Sea is a marginal mediterranean sea of the Atlantic Ocean lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bounded by Bulgaria, Georgia, Rom ...

, a region explored and developed by Greek colonists beginning in the 8th century BC. (''Theogony'' 337–45).

Hesiod mentions a poetry contest at Chalcis in Euboea

Evia (, ; el, Εύβοια ; grc, Εὔβοια ) or Euboia (, ) is the second-largest Greek island in area and population, after Crete. It is separated from Boeotia in mainland Greece by the narrow Euripus Strait (only at its narrowest poin ...

where the sons of one Amphidamas

Amphidamas (; Ancient Greek: Ἀμφιδάμας) was the name of multiple people in Greek mythology:

*Amphidamas, father of Pelagon, king of Phocis, who gave Cadmus the cow that was to guide him to Boeotia.

*Amphidamas or Amphidamantes, fath ...

awarded him a tripod (''Works and Days'' 654–662). Plutarch

Plutarch (; grc-gre, Πλούταρχος, ''Ploútarchos''; ; – after AD 119) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for hi ...

identified this Amphidamas with the hero of the Lelantine War

The Lelantine War was a military conflict between the two ancient Greek city states Chalcis and Eretria in Euboea which took place in the early Archaic period, between c. 710 and 650 BC. The reason for war was, according to tradition, the struggl ...

between Chalcis and Eretria

Eretria (; el, Ερέτρια, , grc, Ἐρέτρια, , literally 'city of the rowers') is a town in Euboea, Greece, facing the coast of Attica across the narrow South Euboean Gulf. It was an important Greek polis in the 6th and 5th centur ...

and he concluded that the passage must be an interpolation into Hesiod's original work, assuming that the Lelantine War was too late for Hesiod. Modern scholars have accepted his identification of Amphidamas but disagreed with his conclusion. The date of the war is not known precisely but estimates placing it around 730–705 BC fit the estimated chronology for Hesiod. In that case, the tripod that Hesiod won might have been awarded for his rendition of ''Theogony'', a poem that seems to presuppose the kind of aristocratic audience he would have met at Chalcis.

Works

Three works have survived which were attributed to Hesiod by ancient commentators: ''Works and Days

''Works and Days'' ( grc, Ἔργα καὶ Ἡμέραι, Érga kaì Hēmérai)The ''Works and Days'' is sometimes called by the Latin translation of the title, ''Opera et Dies''. Common abbreviations are ''WD'' and ''Op''. for ''Opera''. is a ...

'', ''Theogony

The ''Theogony'' (, , , i.e. "the genealogy or birth of the gods") is a poem by Hesiod (8th–7th century BC) describing the origins and genealogies of the Greek gods, composed . It is written in the Epic dialect of Ancient Greek and contain ...

'', and ''Shield of Heracles

The ''Shield of Heracles'' ( grc, Ἀσπὶς Ἡρακλέους, ''Aspis Hērakleous'') is an archaic Greek epic poem that was attributed to Hesiod during antiquity. The subject of the poem is the expedition of Heracles and Iolaus against ...

''. Only fragments exist of other works attributed to him. The surviving works and fragments were all written in the conventional metre and language of epic. However, the ''Shield of Heracles'' is now known to be spurious and probably was written in the sixth century BC. Many ancient critics also rejected ''Theogony'' (e.g., Pausanias Pausanias ( el, Παυσανίας) may refer to:

*Pausanias of Athens, lover of the poet Agathon and a character in Plato's ''Symposium''

*Pausanias the Regent, Spartan general and regent of the 5th century BC

* Pausanias of Sicily, physician of t ...

9.31.3), even though Hesiod mentions himself by name in that poem. ''Theogony'' and ''Works and Days'' might be very different in subject matter, but they share a distinctive language, metre, and prosody that subtly distinguish them from Homer's work and from the ''Shield of Heracles'' (see Hesiod's Greek below). Moreover, they both refer to the same version of the Prometheus myth. Yet even these authentic poems may include interpolations. For example, the first ten verses of the ''Works and Days'' may have been borrowed from an Orphic hymn to Zeus (they were recognised as not the work of Hesiod by critics as ancient as Pausanias).

Some scholars have detected a proto-historical perspective in Hesiod, a view rejected by Paul Cartledge

Paul Anthony Cartledge (born 24 March 1947)"CARTLEDGE, Prof. Paul Anthony", ''Who's Who 2010'', A & C Black, 2010online edition/ref> is a British ancient historian and academic. From 2008 to 2014 he was the A. G. Leventis Professor of Greek C ...

, for example, on the grounds that Hesiod advocates a not-forgetting without any attempt at verification. Hesiod has also been considered the father of gnomic verse

: ''For the map projection see Gnomonic projection; for the game, see Nomic; for the mythological being, see Gnome.''

Gnomic poetry consists of meaningful sayings put into verse to aid the memory. They were known by the Greeks as gnomes (c.f. th ...

. He had "a passion for systematizing and explaining things". Ancient Greek poetry

Ancient Greek literature is literature written in the Ancient Greek language from the earliest texts until the time of the Byzantine Empire. The earliest surviving works of ancient Greek literature, dating back to the early Archaic period, ar ...

in general had strong philosophical tendencies and Hesiod, like Homer, demonstrates a deep interest in a wide range of 'philosophical' issues, from the nature of divine justice to the beginnings of human society. Aristotle (''Metaphysics

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that studies the fundamental nature of reality, the first principles of being, identity and change, space and time, causality, necessity, and possibility. It includes questions about the nature of conscio ...

'' 983b–987a) believed that the question of first causes may even have started with Hesiod (''Theogony'' 116–53) and Homer (''Iliad'' 14.201, 246).

He viewed the world from outside the charmed circle of aristocratic rulers, protesting against their injustices in a tone of voice that has been described as having a "grumpy quality redeemed by a gaunt dignity" but, as stated in the biography section, he could also change to suit the audience. This ambivalence appears to underlie his presentation of human history in ''Works and Days'', where he depicts a golden period when life was easy and good, followed by a steady decline in behaviour and happiness through the silver, bronze, and Iron Ages – except that he inserts a heroic age between the last two, representing its warlike men as better than their bronze predecessors. He seems in this case to be catering to two different world-views, one epic and aristocratic, the other unsympathetic to the heroic traditions of the aristocracy.

''Theogony''

The ''Theogony'' is commonly considered Hesiod's earliest work. Despite the different subject matter between this poem and the ''Works and Days'', most scholars, with some notable exceptions, believe that the two works were written by the same man. As M. L. West writes, "Both bear the marks of a distinct personality: a surly, conservative countryman, given to reflection, no lover of women or life, who felt the gods' presence heavy about him." An example:The ''Theogony'' concerns the origins of the world ( cosmogony) and of the gods (Hateful strife bore painful Toil, Neglect, Starvation, and tearful Pain, Battles, Combats...

theogony

The ''Theogony'' (, , , i.e. "the genealogy or birth of the gods") is a poem by Hesiod (8th–7th century BC) describing the origins and genealogies of the Greek gods, composed . It is written in the Epic dialect of Ancient Greek and contain ...

), beginning with Chaos

Chaos or CHAOS may refer to:

Arts, entertainment and media Fictional elements

* Chaos (''Kinnikuman'')

* Chaos (''Sailor Moon'')

* Chaos (''Sesame Park'')

* Chaos (''Warhammer'')

* Chaos, in ''Fabula Nova Crystallis Final Fantasy''

* Cha ...

, Gaia, Tartarus

In Greek mythology, Tartarus (; grc, , }) is the deep abyss that is used as a dungeon of torment and suffering for the wicked and as the prison for the Titans. Tartarus is the place where, according to Plato's ''Gorgias'' (), souls are judg ...

and Eros

In Greek mythology, Eros (, ; grc, Ἔρως, Érōs, Love, Desire) is the Greek god of love and sex. His Roman counterpart was Cupid ("desire").''Larousse Desk Reference Encyclopedia'', The Book People, Haydock, 1995, p. 215. In the ear ...

, and shows a special interest in genealogy

Genealogy () is the study of families, family history, and the tracing of their lineages. Genealogists use oral interviews, historical records, genetic analysis, and other records to obtain information about a family and to demonstrate kin ...

. Embedded in Greek myth

A major branch of classical mythology, Greek mythology is the body of myths originally told by the ancient Greeks, and a genre of Ancient Greek folklore. These stories concern the origin and nature of the world, the lives and activities of d ...

, there remain fragments of quite variant tales, hinting at the rich variety of myth that once existed, city by city; but Hesiod's retelling of the old stories became, according to Herodotus

Herodotus ( ; grc, , }; BC) was an ancient Greek historian and geographer

A geographer is a physical scientist, social scientist or humanist whose area of study is geography, the study of Earth's natural environment and human society ...

, the accepted version that linked all Hellenes

The Greeks or Hellenes (; el, Έλληνες, ''Éllines'' ) are an ethnic group and nation indigenous to the Eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea regions, namely Greece, Cyprus, Albania, Italy, Turkey, Egypt, and, to a lesser extent, other ...

. It's the earliest known source for the myths of Pandora, Prometheus

In Greek mythology, Prometheus (; , , possibly meaning " forethought")Smith"Prometheus". is a Titan god of fire. Prometheus is best known for defying the gods by stealing fire from them and giving it to humanity in the form of technology, kn ...

and the Golden Age

The term Golden Age comes from Greek mythology, particularly the '' Works and Days'' of Hesiod, and is part of the description of temporal decline of the state of peoples through five Ages, Gold being the first and the one during which the G ...

.

The creation myth in Hesiod has long been held to have Eastern influences, such as the Hittite Song of Kumarbi

Kumarbi was an important god of the Hurrians, regarded as "the father of gods." He was also a member of the Hittite pantheon. According to Hurrian myths, he was a son of Alalu, and one of the parents of the storm-god Teshub, the other being Anu ...

and the Babylonian Enuma Elis. This cultural crossover may have occurred in the eighth- and ninth-century Greek trading colonies such as Al Mina in North Syria. (For more discussion, read Robin Lane Fox's ''Travelling Heroes'' and Walcot's ''Hesiod and the Near East''.)

''Works and Days''

The ''Works and Days'' is a poem of over 800 lines which revolves around two general truths: labour is the universal lot of Man, but he who is willing to work will get by. Scholars have interpreted this work against a background of agrarian crisis in mainland

The ''Works and Days'' is a poem of over 800 lines which revolves around two general truths: labour is the universal lot of Man, but he who is willing to work will get by. Scholars have interpreted this work against a background of agrarian crisis in mainland Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders ...

, which inspired a wave of documented colonisation

Colonization, or colonisation, constitutes large-scale population movements wherein migrants maintain strong links with their, or their ancestors', former country – by such links, gain advantage over other inhabitants of the territory. When ...

s in search of new land.

''Work and Days'' may have been influenced by an established tradition of didactic poetry based on Sumerian, Hebrew, Babylonian and Egyptian wisdom literature.

This work lays out the five Ages of Man

The Ages of Man are the historical stages of human existence according to Greek mythology and its subsequent Roman interpretation.

Both Hesiod and Ovid offered accounts of the successive ages of humanity, which tend to progress from an orig ...

, as well as containing advice and wisdom, prescribing a life of honest labour and attacking idleness and unjust judges (like those who decided in favour of Perses) as well as the practice of usury. It describes immortals who roam the earth watching over justice and injustice. The poem regards labor as the source of all good, in that both gods and men hate the idle, who resemble drones in a hive. In the horror of the triumph of violence over hard work and honor, verses describing the "Golden Age" present the social character and practice of nonviolent diet through agriculture and fruit-culture as a higher path of living sufficiently.

Hesiodic corpus

In addition to the ''Theogony'' and ''Works and Days'', numerous other poems were ascribed to Hesiod during antiquity. Modern scholarship has doubted their authenticity, and these works are generally referred to as forming part of the "Hesiodic corpus" whether or not their authorship is accepted. The situation is summed up in this formulation by Glenn Most: Of these works forming the extended Hesiodic corpus, only the ''Shield of Heracles

The ''Shield of Heracles'' ( grc, Ἀσπὶς Ἡρακλέους, ''Aspis Hērakleous'') is an archaic Greek epic poem that was attributed to Hesiod during antiquity. The subject of the poem is the expedition of Heracles and Iolaus against ...

'' (, ''Aspis Hērakleous'') is transmitted intact via a medieval manuscript tradition.

Classical authors also attributed to Hesiod a lengthy genealogical poem known as ''Catalogue of Women

The ''Catalogue of Women'' ( grc, Γυναικῶν Κατάλογος, Gunaikôn Katálogos)—also known as the ''Ehoiai '' ( grc, Ἠοῖαι, Ēoîai, )The Latin transliterations ''Eoeae'' and ''Ehoeae'' are also used (e.g. , ); see Title ...

'' or ''Ehoiai'' (because sections began with the Greek words ''ē hoiē,'' "Or like the one who ..."). It was a mythological catalogue of the mortal women who had mated with gods, and of the offspring and descendants of these unions.

Several additional hexameter poems were ascribed to Hesiod:

* ''Megalai Ehoiai The ''Megalai Ehoiai'' ( grc, Μεγάλαι Ἠοῖαι, ), or ''Great Ehoiai'', is a fragmentary Greek epic poem that was popularly, though not universally, attributed to Hesiod during antiquity. Like the more widely read Hesiodic ''Catalogue o ...

'', a poem similar to the ''Catalogue of Women'', but presumably longer.

* ''Wedding of Ceyx

The "Wedding of Ceyx" ( grc, Κήυκος γάμος, ''Kḗykos gámos'') is a Lost works, fragmentary Ancient Greek dactylic hexameter, hexameter poem that was attributed to Hesiod during antiquity. The poem did not only deal with the wedding of ...

'', a poem concerning Heracles' attendance at the wedding of a certain Ceyx—noted for its riddles.

* ''Melampodia __notoc__

The "Melampodia" ( grc, Μελαμποδία) is a now fragmentary Greek epic poem that was attributed to Hesiod during antiquity. Its title is derived from the name of the great seer Melampus but must have included myths concerning other ...

'', a genealogical poem that treats of the families of, and myths associated with, the great seers of mythology.

* '' Idaean Dactyls'', a work concerning mythological smelters, the Idaean Dactyls.

* '' Descent of Perithous'', about Theseus

Theseus (, ; grc-gre, Θησεύς ) was the mythical king and founder-hero of Athens. The myths surrounding Theseus his journeys, exploits, and friends have provided material for fiction throughout the ages.

Theseus is sometimes describ ...

and Perithous' trip to Hades.

* ''Precepts of Chiron

__NOTOC__

A lekythos taken to depict Peleus (left) entrusting his son Achilles (center) to the tutelage of Chiron (right), c. 500 BCE, National Archaeological Museum of Athens

The "Precepts of Chiron" ( grc, Χείρωνος ὑποθῆκαι, ...

'', a didactic work that presented the teaching of Chiron

In Greek mythology, Chiron ( ; also Cheiron or Kheiron; ) was held to be the superlative centaur amongst his brethren since he was called the "wisest and justest of all the centaurs".

Biography

Chiron was notable throughout Greek mythology ...

as delivered to the young Achilles

In Greek mythology, Achilles ( ) or Achilleus ( grc-gre, Ἀχιλλεύς) was a hero of the Trojan War, the greatest of all the Greek warriors, and the central character of Homer's '' Iliad''. He was the son of the Nereid Thetis and Pele ...

.

* '' Megala Erga'' or ''Great Works'', a poem similar to the ''Works and Days'', but presumably longer

* '' Astronomia'', an astronomical poem to which Callimachus (''Ep''. 27) apparently compared Aratus

Aratus (; grc-gre, Ἄρατος ὁ Σολεύς; c. 315 BC/310 BC240) was a Greek didactic poet. His major extant work is his hexameter poem ''Phenomena'' ( grc-gre, Φαινόμενα, ''Phainómena'', "Appearances"; la, Phaenomena), the ...

' ''Phaenomena''.

* ''Aegimius

Aegimius (Ancient Greek: Αἰγίμιος) was the Greek mythological ancestor of the Dorians, who is described as their king and lawgiver at the time when they were yet inhabiting the northern parts of Thessaly.

Mythology

Aegimius asked Her ...

'', a heroic epic concerning the Dorian Aegimius

Aegimius (Ancient Greek: Αἰγίμιος) was the Greek mythological ancestor of the Dorians, who is described as their king and lawgiver at the time when they were yet inhabiting the northern parts of Thessaly.

Mythology

Aegimius asked Her ...

(variously attributed to Hesiod or Cercops of Miletus

Aegimius (Ancient Greek: Αἰγίμιος) was the Greek mythological ancestor of the Dorians, who is described as their king and lawgiver at the time when they were yet inhabiting the northern parts of Thessaly.

Mythology

Aegimius asked Hera ...

).

* ''Kiln

A kiln is a thermally insulated chamber, a type of oven, that produces temperatures sufficient to complete some process, such as hardening, drying, or chemical changes. Kilns have been used for millennia to turn objects made from clay int ...

'' or ''Potters'', a brief poem asking Athena to aid potters if they pay the poet. Also attributed to Homer.

* ''Ornithomantia'', a work on bird omens that followed the ''Works and Days''.

In addition to these works, the ''Suda'' lists an otherwise unknown "dirge for Batrachus, esiod'sbeloved".

Reception

* Sappho's countryman and contemporary, the lyric poet Alcaeus, paraphrased a section of ''Works and Days'' (582–88), recasting it in lyric meter and Lesbian dialect. The paraphrase survives only as a fragment.Bacchylides

Bacchylides (; grc-gre, Βακχυλίδης; – ) was a Greek lyric poet. Later Greeks included him in the canonical list of Nine Lyric Poets, which included his uncle Simonides. The elegance and polished style of his lyrics have been noted ...

quoted or paraphrased Hesiod in a victory ode addressed to Hieron of Syracuse

Hieron I ( el, Ἱέρων Α΄; usually Latinized Hiero) was the son of Deinomenes, the brother of Gelon and tyrant of Syracuse in Sicily from 478 to 467 BC. In succeeding Gelon, he conspired against a third brother, Polyzelos.

Life

During his ...

, commemorating the tyrant's victory in the chariot race at the Pythian Games

The Pythian Games ( grc-gre, Πύθια;) were one of the four Panhellenic Games of Ancient Greece. They were held in honour of Apollo at his sanctuary at Delphi every four years, two years after the Olympic Games, and between each Nemean and ...

470 BC, the attribution made with these words: "A man of Boeotia, Hesiod, minister of the weetMuses, spoke thus: 'He whom the immortals honour is attended also by the good report of men.'" However, the quoted words are not found in Hesiod's extant work.The Bacchylidean victory ode is fr. 5 Loeb. Theognis of Megara

Theognis of Megara ( grc-gre, Θέογνις ὁ Μεγαρεύς, ''Théognis ho Megareús'') was a Greek lyric poet active in approximately the sixth century BC. The work attributed to him consists of gnomic poetry quite typical of the time, ...

(169) is the source of a similar sentiment ("Even the fault-finder praises one whom the gods honour") but without attribution. See also fr. 344 M.-W (D. Campbell, ''Greek Lyric Poetry'' IV, Loeb 1992, p. 153)

*Hesiod's ''Catalogue of Women'' created a vogue for catalogue poems in the Hellenistic period. Thus for example Theocritus

Theocritus (; grc-gre, Θεόκριτος, ''Theokritos''; born c. 300 BC, died after 260 BC) was a Greek poet from Sicily and the creator of Ancient Greek pastoral poetry.

Life

Little is known of Theocritus beyond what can be inferred from h ...

presents catalogues of heroines in two of his bucolic poems (3.40–51 and 20.34–41), where both passages are recited in character by lovelorn rustics.

Depictions

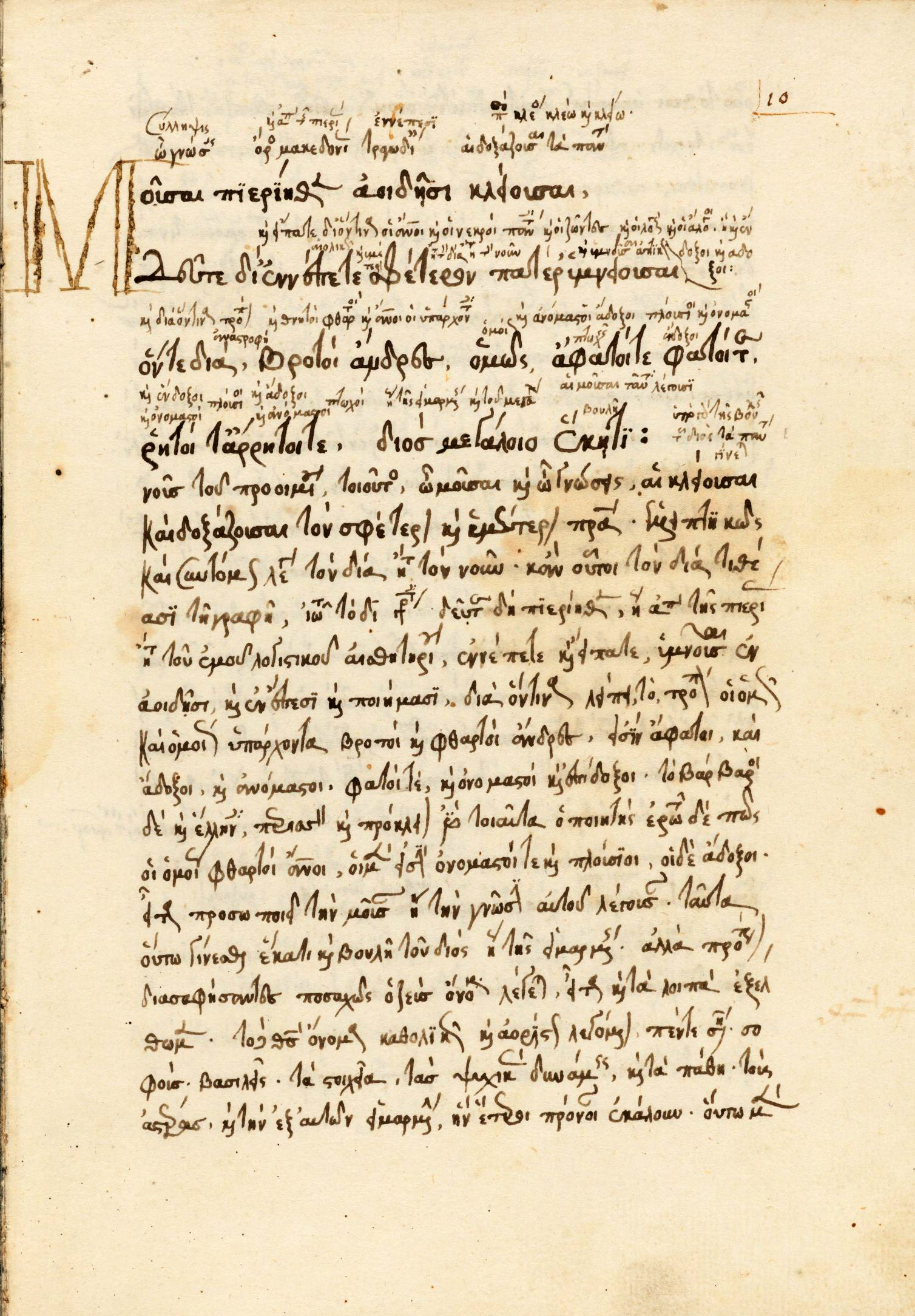

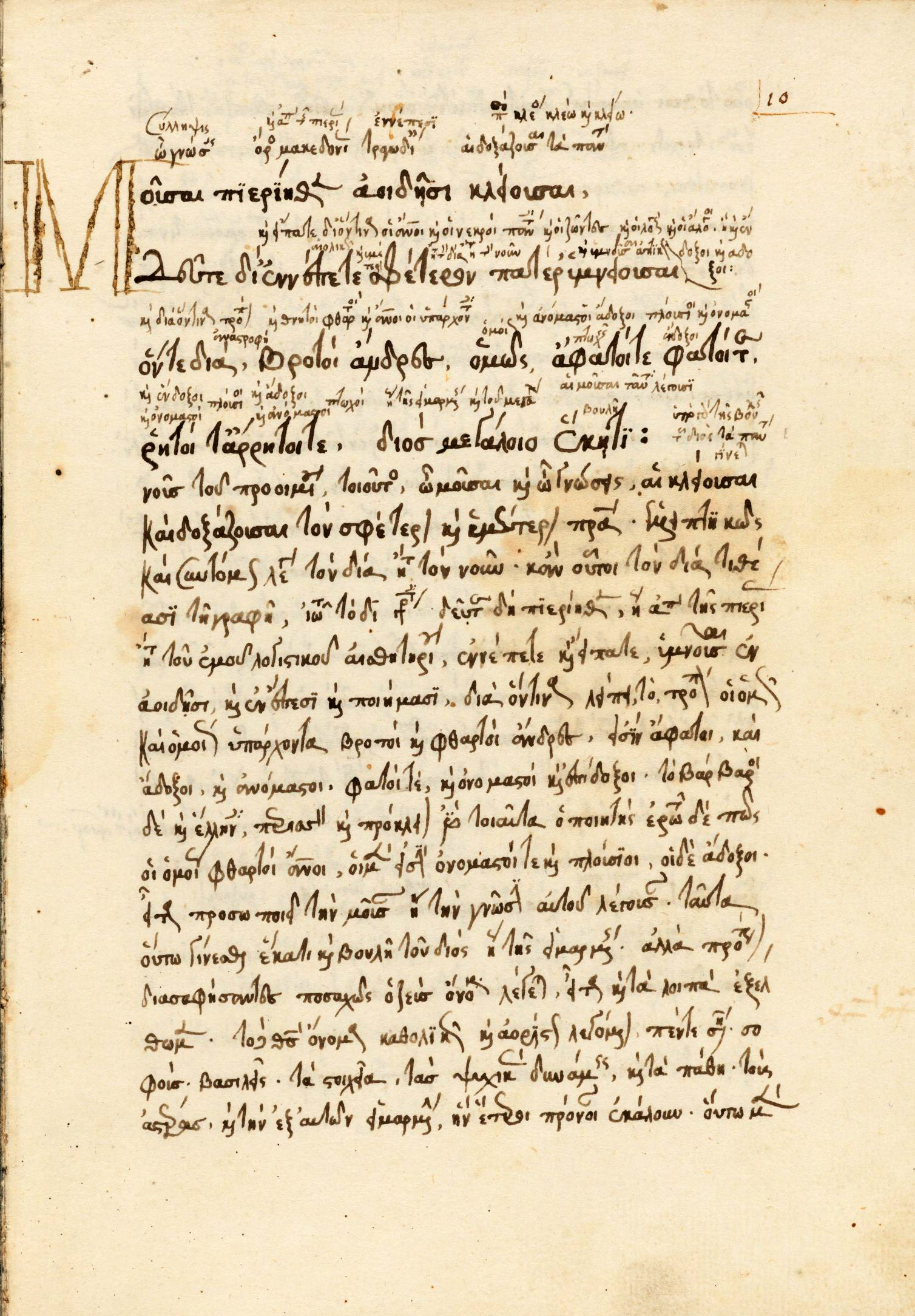

Monnus mosaic

Portrait of Hesiod from Augusta Treverorum (Trier

Trier ( , ; lb, Tréier ), formerly known in English as Trèves ( ;) and Triers (see also names in other languages), is a city on the banks of the Moselle in Germany. It lies in a valley between low vine-covered hills of red sandstone in the ...

), from the end of the 3rd century AD. The mosaic is signed in its central field by the maker, ‘MONNUS FECIT’ (‘Monnus made this’). The figure is identified by name: ‘ESIO-DVS’ ('Hesiod'). It is the only known authenticated portrait of Hesiod.

Portrait bust

The Roman bronze bust, the so-called '' Pseudo-Seneca,'' of the late first century BC found at Herculaneum is now thought not to be ofSeneca the Younger

Lucius Annaeus Seneca the Younger (; 65 AD), usually known mononymously as Seneca, was a Stoic philosopher of Ancient Rome, a statesman, dramatist, and, in one work, satirist, from the post-Augustan age of Latin literature.

Seneca was born in ...

. It has been identified by Gisela Richter

Gisela Marie Augusta Richter (14 or 15 August 1882 – 24 December 1972) was a classical archaeologist and art historian. She was a prominent figure and an authority in her field.

Early life

Gisela Richter was born in London, England, the daught ...

as an imagined portrait of Hesiod. In fact, it has been recognized since 1813 that the bust was not of Seneca, when an inscribed herma portrait of Seneca with quite different features was discovered. Most scholars now follow Richter's identification.Gisela Richter, ''The Portraits of the Greeks''. London: Phaidon (1965), I, p. 58 ff.; commentators agreeing with Richter include Wolfram Prinz, "The Four Philosophers by Rubens and the Pseudo-Seneca in Seventeenth-Century Painting" in ''The Art Bulletin'' 55.3 (September 1973), pp. 410–428. " ��one feels that it may just as well have been the Greek writer Hesiod �� and Martin Robertson, in his review of G. Richter, ''The Portraits of the Greeks'' for ''The Burlington Magazine'' 108.756 (March 1966), pp. 148–150. " ��with Miss Richter, I accept the identification as Hesiod."

Hesiod's Greek

Hesiod employed the conventional dialect of epic verse, which was Ionian. Comparisons with Homer, a native Ionian, can be unflattering. Hesiod's handling of the dactylic hexameter was not as masterful or fluent as Homer's and one modern scholar refers to his "hobnailed hexameters". His use of language and meter in ''Works and Days'' and ''Theogony'' distinguishes him also from the author of the ''Shield of Heracles''. All three poets, for example, employed

Hesiod employed the conventional dialect of epic verse, which was Ionian. Comparisons with Homer, a native Ionian, can be unflattering. Hesiod's handling of the dactylic hexameter was not as masterful or fluent as Homer's and one modern scholar refers to his "hobnailed hexameters". His use of language and meter in ''Works and Days'' and ''Theogony'' distinguishes him also from the author of the ''Shield of Heracles''. All three poets, for example, employed digamma

Digamma or wau (uppercase: Ϝ, lowercase: ϝ, numeral: ϛ) is an archaic letter of the Greek alphabet. It originally stood for the sound but it has remained in use principally as a Greek numeral for 6. Whereas it was originally called ''waw' ...

inconsistently, sometimes allowing it to affect syllable length and meter, sometimes not. The ratio of observance/neglect of digamma varies between them. The extent of variation depends on how the evidence is collected and interpreted but there is a clear trend, revealed for example in the following set of statistics.

Hesiod does not observe digamma as often as the others do. That result is a bit counter-intuitive since digamma was still a feature of the Boeotian dialect that Hesiod probably spoke, whereas it had already vanished from the Ionic vernacular of Homer. This anomaly can be explained by the fact that Hesiod made a conscious effort to compose like an Ionian epic poet at a time when digamma was not heard in Ionian speech, while Homer tried to compose like an older generation of Ionian bards, when it was heard in Ionian speech. There is also a significant difference in the results for ''Theogony'' and ''Works and Days'', but that is merely due to the fact that the former includes a catalog of divinities and therefore it makes frequent use of the definite article associated with digamma, oἱ.

Though typical of epic, his vocabulary features some significant differences from Homer's. One scholar has counted 278 un-Homeric words in ''Works and Days'', 151 in ''Theogony'' and 95 in ''Shield of Heracles''. The disproportionate number of un-Homeric words in ''W & D'' is due to its un-Homeric subject matter.The count of un-Homeric words is by H.K. Fietkau, ''De carminum hesiodeorum atque hymnorum quattuor magnorum vocabulis non homericis'' (Königsberg, 1866), cited by M. L. West, ''Hesiod: Theogony'', p. 77. Hesiod's vocabulary also includes quite a lot of formulaic phrases that are not found in Homer, which indicates that he may have been writing within a different tradition.West, ''Hesiod: Theogony'', p. 78.

Notes

Citations

References

* Allen, T. W. and Arthur A. Rambaut, "The Date of Hesiod", ''The Journal of Hellenic Studies

''The Journal of Hellenic Studies'' is an annual peer-reviewed academic journal covering research in Hellenic studies. It also publishes reviews of recent books of importance to Hellenic studies. It was established in 1880 and is published by Camb ...

'', 35 (1915), pp. 85–99.

* .

* .

* Barron, J. P. and Easterling, P. E. (1985), "Hesiod", ''The Cambridge History of Classical Literature: Greek Literature'', Cambridge University Press.

* Buckham, Philip Wentworth (1827)''Theatre of the Greeks''

* . * . * Evelyn-White, Hugh G. (1964), ''Hesiod, the Homeric Hymns and Homerica'' (= Loeb Classical Library, vol. 57), Harvard University Press, pp. xliii–xlvii. * Lamberton, Robert (1988)

''Hesiod''

New Haven:

Yale University Press

Yale University Press is the university press of Yale University. It was founded in 1908 by George Parmly Day, and became an official department of Yale University in 1961, but it remains financially and operationally autonomous.

, Yale Universi ...

. .

* .

* .

* Murray, Gilbert (1897), ''A History of Ancient Greek Literature'', New York: D. Appleton and Company, pp. 53 ff.

* .

* Peabody, Berkley (1975), ''The Winged Word: A Study in the Technique of Ancient Greek Oral Composition as Seen Principally Through Hesiod's Works and Days'', State University of New York Press. .

* Pucci, Pietro (1977), ''Hesiod and the Language of Poetry'', Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins University Press. .

* .

* Erwin Rohde, Rohde, Erwin (1925), ''Psyche. The cult of the souls and belief in immortality among the Greeks'', London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co.

* John Addington Symonds, Symonds, John Addington (1873), ''Studies of the Greek Poets'', London: Smyth, Elder & Co.

* Thomas Taylor (neoplatonist), Taylor, Thomas (1891), ''A Dissertation on the Eleusinian and Bacchic Mysteries'', New York: J. W. Bouton.

*

Further reading

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Zeitlin, Froma (1996). 'Signifying difference: the case of Hesiod's Pandora', in Froma Zeitlin, ''Playing the Other: Gender and Society in Classical Greek Literature''. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 53–86.Selected translations

* George Chapman, ''The Works of Hesiod'', London, 1618, dedicated to Sir Francis Bacon. * Cooke, Hesiod, ''Works and Days'', Translated from the Greek, London, 1728 * Sinclair, Thomas Alan (translator), ''Hesiodou Erga kai hemerai'', London, Macmillan and co., 1932. * Martin Litchfield West, West, Martin Litchfield (translator), ''Hesiod Works & Days'', Oxford University Press, 1978, . Edited with Prolegomena and Commentary. * Apostolos Athanassakis, Athanassakis, Apostolos N., ''Theogony; Works and days; Shield / Hesiod; introduction, translation, and notes'', Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1983. * Frazer, R.M. (Richard McIlwaine), ''The Poems of Hesiod'', Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1983. * Tandy, David W., and Neale, Walter C. [translators], ''Works and Days: a translation and commentary for the social sciences'', Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996. * Schlegel, Catherine M., and Henry Weinfield, translators, ''Theogony and Works and Days'', Ann Arbor, Michigan, 2006 * . * .External links

* * * * Hesiod''Works and Days Book 1''

Translated from the Greek by Mr. Cooke (London, 1728). A youthful exercise in Augustan heroic couplets by Thomas Cooke (1703–1756), employing the Roman names for all the gods. * Web texts taken from ''Hesiod, the Homeric Hymns and Homerica'', edited and translated by Hugh G. Evelyn-White, published as Loeb Classical Library No. 57, 1914, :

Scanned text at the Internet Archive

in Portable Document Format, PDF and DjVu format *

Perseus Classics Collection: Greek and Roman Materials: Text: Hesiod

(Greek texts and English translations for ''Works and Days'', ''

Theogony

The ''Theogony'' (, , , i.e. "the genealogy or birth of the gods") is a poem by Hesiod (8th–7th century BC) describing the origins and genealogies of the Greek gods, composed . It is written in the Epic dialect of Ancient Greek and contain ...

'', and ''Shield of Heracles'' with additional notes and cross links.)

** Versions of the electronic edition of Evelyn-White's English translation edited by Douglas B. Killings, June 1995:

**Project Gutenberg plain text

**

The Medieval and Classical Literature Library: Hesiod

**

(''Theogony'' and ''Works and Days'' only) *

Hesiod Poems and Fragments

including Ps-Hesiod works ''Astronomy'' and ''Catalogue of Women'' a

demonax.info

{{Authority control Hesiod, 8th-century BC births 8th-century BC Greek people 8th-century BC poets Ancient Boeotian poets Ancient Greek didactic poets Ancient Greek poets Ancient Greek economists Year of death unknown 8th-century BC religious leaders 7th-century BC religious leaders