Heroism on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A hero (feminine: heroine) is a real person or a main fictional character who, in the face of danger, combats adversity through feats of ingenuity, courage, or strength. Like other formerly gender-specific terms (like ''actor''), ''hero'' is often used to refer to any gender, though ''heroine'' only refers to women. The original hero type of classical epics did such things for the sake of glory and

A hero (feminine: heroine) is a real person or a main fictional character who, in the face of danger, combats adversity through feats of ingenuity, courage, or strength. Like other formerly gender-specific terms (like ''actor''), ''hero'' is often used to refer to any gender, though ''heroine'' only refers to women. The original hero type of classical epics did such things for the sake of glory and

The word ''hero'' comes from the Greek ἥρως (''hērōs''), "hero" (literally "protector" or "defender"), particularly one such as Heracles with divine ancestry or later given divine honors. Before the decipherment of Linear B the original form of the word was assumed to be *, ''hērōw-'', but the Mycenaean compound ''ti-ri-se-ro-e'' demonstrates the absence of -w-. Hero as a name appears in pre-Homeric Greek mythology, wherein Hero and Leander, Hero was a priestess of the goddess Aphrodite, in a myth that has been referred to often in literature.

According to ''The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language'', the Proto-Indo-European language, Proto-Indo-European root is ''*ser'' meaning "to protect". According to Eric Partridge in ''Origins'', the Greek word ''hērōs'' "is akin to" the Latin ''seruāre'', meaning ''to safeguard''. Partridge concludes, "The basic sense of both Hera and hero would therefore be 'protector'." Robert S. P. Beekes, R. S. P. Beekes rejects an Indo-European derivation and asserts that the word has a Pre-Greek substrate, Pre-Greek origin. Hera was a Greek goddess with many attributes, including protection and her worship appears to have similar proto-Indo-European origins.

The word ''hero'' comes from the Greek ἥρως (''hērōs''), "hero" (literally "protector" or "defender"), particularly one such as Heracles with divine ancestry or later given divine honors. Before the decipherment of Linear B the original form of the word was assumed to be *, ''hērōw-'', but the Mycenaean compound ''ti-ri-se-ro-e'' demonstrates the absence of -w-. Hero as a name appears in pre-Homeric Greek mythology, wherein Hero and Leander, Hero was a priestess of the goddess Aphrodite, in a myth that has been referred to often in literature.

According to ''The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language'', the Proto-Indo-European language, Proto-Indo-European root is ''*ser'' meaning "to protect". According to Eric Partridge in ''Origins'', the Greek word ''hērōs'' "is akin to" the Latin ''seruāre'', meaning ''to safeguard''. Partridge concludes, "The basic sense of both Hera and hero would therefore be 'protector'." Robert S. P. Beekes, R. S. P. Beekes rejects an Indo-European derivation and asserts that the word has a Pre-Greek substrate, Pre-Greek origin. Hera was a Greek goddess with many attributes, including protection and her worship appears to have similar proto-Indo-European origins.

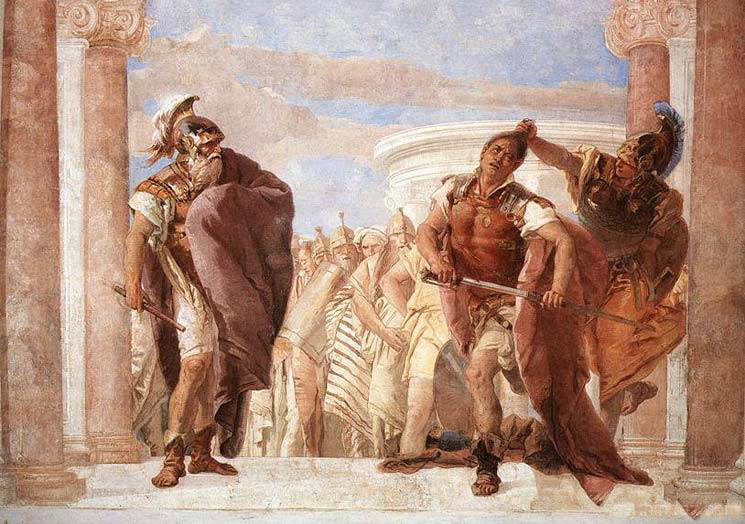

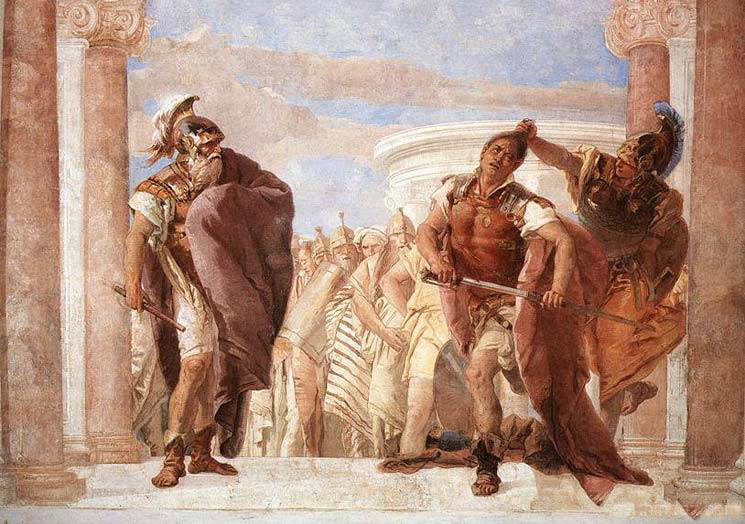

A classical hero is considered to be a "warrior who lives and dies in the pursuit of honor" and asserts their greatness by "the brilliancy and efficiency with which they kill". Each classical hero's life focuses on fighting, which occurs in war or during an epic quest. Classical heroes are commonly semi-divine and extraordinarily gifted, such as Achilles, evolving into heroic characters through their perilous circumstances. While these heroes are incredibly resourceful and skilled, they are often foolhardy, court disaster, risk their followers' lives for trivial matters, and behave arrogantly in a childlike manner. During classical times, people regarded heroes with the highest esteem and utmost importance, explaining their prominence within epic literature. The appearance of these mortal figures marks a revolution of audiences and writers turning away from Twelve Olympians, immortal gods to mortal mankind, whose heroic moments of glory survive in the memory of their descendants, extending their legacy.

Hector was a Troy, Trojan prince and the greatest fighter for Troy in the Trojan War, which is known primarily through Homer's ''Iliad''. Hector acted as leader of the Trojans and their allies in the defense of Troy, "killing 31,000 Greek fighters," offers Hyginus. Hector was known not only for his courage, but also for his noble and courtly nature. Indeed, Homer places Hector as peace-loving, thoughtful, as well as bold, a good son, husband and father, and without darker motives. However, his familial values conflict greatly with his heroic aspirations in the ''Iliad,'' as he cannot be both the protector of Troy and a father to his child. Hector is ultimately betrayed by the deities when Athena appears disguised as his ally Deiphobus and convinces him challenge Achilles, leading to his death at the hands of a superior warrior.Homer. ''The Iliad.'' Trans. Robert Fagles (1990). NY: Penguin Books. Chapter 14

A classical hero is considered to be a "warrior who lives and dies in the pursuit of honor" and asserts their greatness by "the brilliancy and efficiency with which they kill". Each classical hero's life focuses on fighting, which occurs in war or during an epic quest. Classical heroes are commonly semi-divine and extraordinarily gifted, such as Achilles, evolving into heroic characters through their perilous circumstances. While these heroes are incredibly resourceful and skilled, they are often foolhardy, court disaster, risk their followers' lives for trivial matters, and behave arrogantly in a childlike manner. During classical times, people regarded heroes with the highest esteem and utmost importance, explaining their prominence within epic literature. The appearance of these mortal figures marks a revolution of audiences and writers turning away from Twelve Olympians, immortal gods to mortal mankind, whose heroic moments of glory survive in the memory of their descendants, extending their legacy.

Hector was a Troy, Trojan prince and the greatest fighter for Troy in the Trojan War, which is known primarily through Homer's ''Iliad''. Hector acted as leader of the Trojans and their allies in the defense of Troy, "killing 31,000 Greek fighters," offers Hyginus. Hector was known not only for his courage, but also for his noble and courtly nature. Indeed, Homer places Hector as peace-loving, thoughtful, as well as bold, a good son, husband and father, and without darker motives. However, his familial values conflict greatly with his heroic aspirations in the ''Iliad,'' as he cannot be both the protector of Troy and a father to his child. Hector is ultimately betrayed by the deities when Athena appears disguised as his ally Deiphobus and convinces him challenge Achilles, leading to his death at the hands of a superior warrior.Homer. ''The Iliad.'' Trans. Robert Fagles (1990). NY: Penguin Books. Chapter 14 Achilles was a Greek hero who was considered the most formidable military fighter in the entire Trojan War and the central character of the ''Iliad''. He was the child of Thetis and Peleus, making him a Demigod, demi-god. He wielded superhuman strength on the battlefield and was blessed with a close relationship to the List of Greek mythological figures#Immortals, deities. Achilles famously refused to fight after his dishonoring at the hands of Agamemnon, and only returned to the war due to unadulterated rage after Hector killed his beloved companion Patroclus. Achilles was known for uncontrollable rage that defined many of his bloodthirsty actions, such as defiling Hector's corpse by dragging it around the city of Troy. Achilles plays a tragic role in the ''Iliad'' brought about by constan

Achilles was a Greek hero who was considered the most formidable military fighter in the entire Trojan War and the central character of the ''Iliad''. He was the child of Thetis and Peleus, making him a Demigod, demi-god. He wielded superhuman strength on the battlefield and was blessed with a close relationship to the List of Greek mythological figures#Immortals, deities. Achilles famously refused to fight after his dishonoring at the hands of Agamemnon, and only returned to the war due to unadulterated rage after Hector killed his beloved companion Patroclus. Achilles was known for uncontrollable rage that defined many of his bloodthirsty actions, such as defiling Hector's corpse by dragging it around the city of Troy. Achilles plays a tragic role in the ''Iliad'' brought about by constan

de-humanization

throughout the epic, having his ''menis'' (wrath) overpower his ''philos'' (love). Heroes in myth often had close, but conflicted relationships with the deities. Thus Heracles's name means "the glory of Hera", even though he was tormented all his life by Hera, the Queen of the Greek deities. Perhaps the most striking example is the Athenian king Erechtheus, whom Poseidon killed for choosing Athena rather than him as the city's patron deity. When the Athenians worshiped Erechtheus on the Acropolis of Athens, Acropolis, they invoked him as ''Poseidon Erechtheus''. Destiny, Fate, or destiny, plays a massive role in the stories of classical heroes. The classical hero's heroic significance stems from battlefield conquests, an inherently dangerous action. The deities in Greek mythology, when interacting with the heroes, often foreshadow the hero's eventual death on the battlefield. Countless heroes and deities go to great lengths to alter their pre-destined fates, but with no success, as none, neither human or immortal can change their prescribed outcomes by the three powerful Fates. The most characteristic example of this is found in ''Oedipus Rex.'' After learning that his son, Oedipus, will end up killing him, the King of Thebes, Laius, takes huge steps to assure his son's death by removing him from the kingdom. When Oedipus encounters his father when his father was unknown to him in a dispute on the road many years later, Oedipus slays him without an afterthought. The lack of recognition enabled Oedipus to slay his father, ironically further binding his father to his fate. Stories of heroism may serve as moral examples. However, classical heroes often didn't embody the Christian notion of an upstanding, perfectly moral hero. For example, Achilles's character-issues of hateful rage lead to merciless slaughter and his overwhelming pride lead to him only joining the Trojan War because he didn't want his soldiers to win all of the glory. Classical heroes, regardless of their morality, were placed in religion. In classical antiquity, cults that venerated deified heroes such as Heracles, Perseus, and Achilles played an important role in Ancient Greek religion.Graf, Fritz. (2006) "Hero Cult".

Brills New Pauly

'. These ancient Greek hero cults worshipped heroes from oral Epic Cycle, epic tradition, with these heroes often bestowing blessings, especially healing ones, on individuals.

The concept of the "Mythic Hero Archetype" was first developed by FitzRoy Somerset, 4th Baron Raglan, Lord Raglan in his 1936 book, ''The Hero, A Study in Tradition, Myth and Drama''. It is a set of 22 common traits that he said were shared by many heroes in various cultures, myths, and religions throughout history and around the world. Raglan argued that the higher the score, the more likely the figure is mythical.

The concept of a story archetype of the standard Hero's journey, monomythical "hero's quest" that was reputed to be pervasive across all cultures, is somewhat controversial. Expounded mainly by Joseph Campbell in his 1949 work ''The Hero with a Thousand Faces'', it illustrates several uniting themes of hero stories that hold similar ideas of what a hero represents, despite vastly different cultures and beliefs. The monomyth or Hero's Journey consists of three separate stages including the Departure, Initiation, and Return. Within these stages there are several archetypes that the hero of either gender may follow, including the call to adventure (which they may initially refuse), supernatural aid, proceeding down a road of trials, achieving a realization about themselves (or an apotheosis), and attaining the freedom to live through their quest or journey. Campbell offered examples of stories with similar themes such as Krishna, Gautama Buddha, Buddha, Apollonius of Tyana, and Jesus.Joseph Campbell in ''The Hero With a Thousand Faces'' Princeton University Press, 2004 [1949], 140, One of the themes he explores is the androgynous hero, who combines male and female traits, such as Bodhisattva: "The first wonder to be noted here is the androgynous character of the Bodhisattva: masculine Avalokiteshvara, feminine Kwan Yin." In his 1968 book, ''The Masks of God: Occidental Mythology'', Campbell writes, "It is clear that, whether accurate or not as to biographical detail, the moving legend of the Crucified and Risen Christ was fit to bring a new warmth, immediacy, and humanity, to the old motifs of the beloved Dumuzid, Tammuz, Adonis, and Osiris cycles."

The concept of the "Mythic Hero Archetype" was first developed by FitzRoy Somerset, 4th Baron Raglan, Lord Raglan in his 1936 book, ''The Hero, A Study in Tradition, Myth and Drama''. It is a set of 22 common traits that he said were shared by many heroes in various cultures, myths, and religions throughout history and around the world. Raglan argued that the higher the score, the more likely the figure is mythical.

The concept of a story archetype of the standard Hero's journey, monomythical "hero's quest" that was reputed to be pervasive across all cultures, is somewhat controversial. Expounded mainly by Joseph Campbell in his 1949 work ''The Hero with a Thousand Faces'', it illustrates several uniting themes of hero stories that hold similar ideas of what a hero represents, despite vastly different cultures and beliefs. The monomyth or Hero's Journey consists of three separate stages including the Departure, Initiation, and Return. Within these stages there are several archetypes that the hero of either gender may follow, including the call to adventure (which they may initially refuse), supernatural aid, proceeding down a road of trials, achieving a realization about themselves (or an apotheosis), and attaining the freedom to live through their quest or journey. Campbell offered examples of stories with similar themes such as Krishna, Gautama Buddha, Buddha, Apollonius of Tyana, and Jesus.Joseph Campbell in ''The Hero With a Thousand Faces'' Princeton University Press, 2004 [1949], 140, One of the themes he explores is the androgynous hero, who combines male and female traits, such as Bodhisattva: "The first wonder to be noted here is the androgynous character of the Bodhisattva: masculine Avalokiteshvara, feminine Kwan Yin." In his 1968 book, ''The Masks of God: Occidental Mythology'', Campbell writes, "It is clear that, whether accurate or not as to biographical detail, the moving legend of the Crucified and Risen Christ was fit to bring a new warmth, immediacy, and humanity, to the old motifs of the beloved Dumuzid, Tammuz, Adonis, and Osiris cycles."

Vladimir Propp, in his analysis of Russian fairy tales, concluded that a fairy tale had only eight ''dramatis personæ'', of which one was the hero,Vladimir Propp, ''Morphology of the Folk Tale'', and his analysis has been widely applied to non-Russian folklore. The actions that fall into such a hero's sphere include:

# Departure on a quest

# Reacting to the test of a Donor (fairy tale), donor

# Marrying a princess (or similar figure)

Propp distinguished between ''seekers'' and ''victim-heroes''. A

Vladimir Propp, in his analysis of Russian fairy tales, concluded that a fairy tale had only eight ''dramatis personæ'', of which one was the hero,Vladimir Propp, ''Morphology of the Folk Tale'', and his analysis has been widely applied to non-Russian folklore. The actions that fall into such a hero's sphere include:

# Departure on a quest

# Reacting to the test of a Donor (fairy tale), donor

# Marrying a princess (or similar figure)

Propp distinguished between ''seekers'' and ''victim-heroes''. A

No history can be written without consideration of the lengthy list of List of medals for bravery, recipients of national medals for bravery, populated by firefighters, policemen and policewomen, ambulance medics, and ordinary have-a-go heroes. These persons risked their lives to try to save or protect the lives of others: for example, the Canadian Cross of Valour (Canada), Cross of Valour (C.V.) "recognizes acts of the most conspicuous courage in circumstances of extreme peril"; examples of recipients are Mary Dohey and David Gordon Cheverie.

The philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Hegel gave a central role to the "hero", personalized by Napoleon, as the incarnation of a particular culture's ''Geist#Volksgeist, Volksgeist'', and thus of the general ''Zeitgeist''. Thomas Carlyle's 1841 work, ''On Heroes, Hero-Worship, & the Heroic in History'', also accorded a key function to heroes and great men in history. Carlyle centered history on the biography, biographies of individuals, as in ''Oliver Cromwell's Letters and Speeches'' and ''History of Frederick the Great''. His heroes were not only political and military figures, the founders or topplers of states, but also religious figures, poets, authors, and captains of industry.

Explicit defenses of Carlyle's position were rare in the second part of the 20th century. Most in the philosophy of history school contend that the motive forces in history may best be described only with a wider lens than the one that Carlyle used for his portraits. For example, Karl Marx argued that history was determined by the massive social forces at play in "Class conflict, class struggles", not by the individuals by whom these forces are played out. After Marx, Herbert Spencer wrote at the end of the 19th century: "You must admit that the genesis of the great man depends on the long series of complex influences which has produced the race in which he appears, and the social state into which that race has slowly grown...[b]efore he can remake his society, his society must make him."Spencer, Herbert.

No history can be written without consideration of the lengthy list of List of medals for bravery, recipients of national medals for bravery, populated by firefighters, policemen and policewomen, ambulance medics, and ordinary have-a-go heroes. These persons risked their lives to try to save or protect the lives of others: for example, the Canadian Cross of Valour (Canada), Cross of Valour (C.V.) "recognizes acts of the most conspicuous courage in circumstances of extreme peril"; examples of recipients are Mary Dohey and David Gordon Cheverie.

The philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Hegel gave a central role to the "hero", personalized by Napoleon, as the incarnation of a particular culture's ''Geist#Volksgeist, Volksgeist'', and thus of the general ''Zeitgeist''. Thomas Carlyle's 1841 work, ''On Heroes, Hero-Worship, & the Heroic in History'', also accorded a key function to heroes and great men in history. Carlyle centered history on the biography, biographies of individuals, as in ''Oliver Cromwell's Letters and Speeches'' and ''History of Frederick the Great''. His heroes were not only political and military figures, the founders or topplers of states, but also religious figures, poets, authors, and captains of industry.

Explicit defenses of Carlyle's position were rare in the second part of the 20th century. Most in the philosophy of history school contend that the motive forces in history may best be described only with a wider lens than the one that Carlyle used for his portraits. For example, Karl Marx argued that history was determined by the massive social forces at play in "Class conflict, class struggles", not by the individuals by whom these forces are played out. After Marx, Herbert Spencer wrote at the end of the 19th century: "You must admit that the genesis of the great man depends on the long series of complex influences which has produced the race in which he appears, and the social state into which that race has slowly grown...[b]efore he can remake his society, his society must make him."Spencer, Herbert.

The Study of Sociology

', Appleton, 1896, p. 34. Michel Foucault argued in Philosophy of history#Michel Foucault's analysis of historical and political discourse, his analysis of societal communication and debate that history was mainly the "science of the Sovereignty, sovereign", until its inversion by the "historical and political popular discourse".

Modern examples of the typical hero are, Minnie Vautrin, Norman Bethune, Alan Turing, Raoul Wallenberg, Chiune Sugihara, Martin Luther King Jr., Mother Teresa, Nelson Mandela, Oswaldo Payá, Óscar Elías Biscet, and Aung San Suu Kyi.

The Annales school, led by Lucien Febvre, Marc Bloch, and Fernand Braudel, would contest the exaggeration of the role of Subject (philosophy), individual subjects in history. Indeed, Braudel distinguished various time scales, one accorded to the life of an individual, another accorded to the life of a few human generations, and the last one to civilizations, in which geography, economics, and demography play a role considerably more decisive than that of individual subjects.

Among noticeable events in the studies of the role of the hero and Great man theory, great man in history one should mention Sidney Hook's book (1943) ''Sidney Hook#Hero in History, The Hero in History''. In the second half of the twentieth century such male-focused theory has been contested, among others by feminists writers such as Judith Fetterley in ''The Resisting Reader'' (1977) and literary theorist Nancy K. Miller, ''The Heroine's Text: Readings in the French and English Novel, 1722–1782''.

In the epoch of globalization an individual may change the development of the country and of the whole world, so this gives reasons to some scholars to suggest returning to the problem of the role of the hero in history from the viewpoint of modern historical knowledge and using up-to-date methods of historical analysis.

Within the frameworks of developing counterfactual history, attempts are made to examine some hypothetical scenarios of historical development. The hero attracts much attention because most of those scenarios are based on the suppositions: what would have happened if this or that historical individual had or had not been alive.

Modern examples of the typical hero are, Minnie Vautrin, Norman Bethune, Alan Turing, Raoul Wallenberg, Chiune Sugihara, Martin Luther King Jr., Mother Teresa, Nelson Mandela, Oswaldo Payá, Óscar Elías Biscet, and Aung San Suu Kyi.

The Annales school, led by Lucien Febvre, Marc Bloch, and Fernand Braudel, would contest the exaggeration of the role of Subject (philosophy), individual subjects in history. Indeed, Braudel distinguished various time scales, one accorded to the life of an individual, another accorded to the life of a few human generations, and the last one to civilizations, in which geography, economics, and demography play a role considerably more decisive than that of individual subjects.

Among noticeable events in the studies of the role of the hero and Great man theory, great man in history one should mention Sidney Hook's book (1943) ''Sidney Hook#Hero in History, The Hero in History''. In the second half of the twentieth century such male-focused theory has been contested, among others by feminists writers such as Judith Fetterley in ''The Resisting Reader'' (1977) and literary theorist Nancy K. Miller, ''The Heroine's Text: Readings in the French and English Novel, 1722–1782''.

In the epoch of globalization an individual may change the development of the country and of the whole world, so this gives reasons to some scholars to suggest returning to the problem of the role of the hero in history from the viewpoint of modern historical knowledge and using up-to-date methods of historical analysis.

Within the frameworks of developing counterfactual history, attempts are made to examine some hypothetical scenarios of historical development. The hero attracts much attention because most of those scenarios are based on the suppositions: what would have happened if this or that historical individual had or had not been alive.

The word "hero" (or "heroine" in modern times), is sometimes used to describe the protagonist or the List of stock characters, romantic interest of a story, a usage which may conflict with the superhuman expectations of heroism. A good example is Anna Karenina, the lead character in the novel of the same title by Leo Tolstoy. In modern literature the hero is more and more a problematic concept. In 1848, for example, William Makepeace Thackeray gave ''Vanity Fair (novel), Vanity Fair'' the subtitle, ''A Novel without a Hero'', and imagined a world in which no sympathetic character was to be found. ''Vanity Fair'' is a satirical representation of the absence of truly moral heroes in the modern world. The story focuses on the characters, Emmy Sedley and Becky Sharpe (the latter as the clearly defined anti-hero), with the plot focused on the eventual marriage of these two characters to rich men, revealing character flaws as the story progresses. Even the most sympathetic characters, such as Captain Dobbin, are susceptible to weakness, as he is often narcissistic and melancholic.

The larger-than-life hero is a more common feature of fantasy (particularly in comic books and High fantasy, epic fantasy) than more realist works.L. Sprague de Camp, ''Literary Swordsmen and Sorcerers: The Makers of Heroic Fantasy'', p. 5 However, these larger-than life figures remain prevalent in society. The superhero genre is a multibillion-dollar industry that includes comic books, movies, toys, and video games. Superheroes usually possess extraordinary talents and powers that no living human could ever possess. The superhero stories often pit a Supervillain, super villain against the hero, with the hero fighting the crime caused by the super villain. Examples of long-running superheroes include Superman, Wonder Woman, Batman, and Spider-Man.

Research indicates that male writers are more likely to make heroines superhuman, whereas female writers tend to make heroines ordinary humans, as well as making their male heroes more powerful than their heroines, possibly due to sex differences in valued traits.

The word "hero" (or "heroine" in modern times), is sometimes used to describe the protagonist or the List of stock characters, romantic interest of a story, a usage which may conflict with the superhuman expectations of heroism. A good example is Anna Karenina, the lead character in the novel of the same title by Leo Tolstoy. In modern literature the hero is more and more a problematic concept. In 1848, for example, William Makepeace Thackeray gave ''Vanity Fair (novel), Vanity Fair'' the subtitle, ''A Novel without a Hero'', and imagined a world in which no sympathetic character was to be found. ''Vanity Fair'' is a satirical representation of the absence of truly moral heroes in the modern world. The story focuses on the characters, Emmy Sedley and Becky Sharpe (the latter as the clearly defined anti-hero), with the plot focused on the eventual marriage of these two characters to rich men, revealing character flaws as the story progresses. Even the most sympathetic characters, such as Captain Dobbin, are susceptible to weakness, as he is often narcissistic and melancholic.

The larger-than-life hero is a more common feature of fantasy (particularly in comic books and High fantasy, epic fantasy) than more realist works.L. Sprague de Camp, ''Literary Swordsmen and Sorcerers: The Makers of Heroic Fantasy'', p. 5 However, these larger-than life figures remain prevalent in society. The superhero genre is a multibillion-dollar industry that includes comic books, movies, toys, and video games. Superheroes usually possess extraordinary talents and powers that no living human could ever possess. The superhero stories often pit a Supervillain, super villain against the hero, with the hero fighting the crime caused by the super villain. Examples of long-running superheroes include Superman, Wonder Woman, Batman, and Spider-Man.

Research indicates that male writers are more likely to make heroines superhuman, whereas female writers tend to make heroines ordinary humans, as well as making their male heroes more powerful than their heroines, possibly due to sex differences in valued traits.

On Heroes, Hero Worship and the Heroic in History

' * Craig, David, ''Back Home'', Life Magazine-Special Issue, Volume 8, Number 6, 85–94. * * * * * Hook, Sydney (1943) ''The Hero in History: A Study in Limitation and Possibility'' * * * Henry Liddell, Lidell, Henry and Robert Scott (philologist), Robert Scott. ''A Greek–English Lexicon.''

link

* * * (Republished 2003) * *

nbsp;— online exhibition from screenonline, a website of the British Film Institute, looking at British heroes of film and television.

Listen to BBC Radio 4's ''In Our Time'' programme on Heroism"The Role of Heroes in Children's Lives"

by Marilyn Price-Mitchell, PhD *

10% — What Makes A Hero

' directed by Yoav Shamir {{Authority control Heroes, Epic poetry Good and evil Fantasy tropes Jungian archetypes Literary archetypes Mythological archetypes Mythological characters Protagonists by role

A hero (feminine: heroine) is a real person or a main fictional character who, in the face of danger, combats adversity through feats of ingenuity, courage, or strength. Like other formerly gender-specific terms (like ''actor''), ''hero'' is often used to refer to any gender, though ''heroine'' only refers to women. The original hero type of classical epics did such things for the sake of glory and

A hero (feminine: heroine) is a real person or a main fictional character who, in the face of danger, combats adversity through feats of ingenuity, courage, or strength. Like other formerly gender-specific terms (like ''actor''), ''hero'' is often used to refer to any gender, though ''heroine'' only refers to women. The original hero type of classical epics did such things for the sake of glory and honor

Honour (British English) or honor (American English; see spelling differences) is the idea of a bond between an individual and a society as a quality of a person that is both of social teaching and of personal ethos, that manifests itself as a ...

. Post-classical

In world history, post-classical history refers to the period from about 500 AD to 1500, roughly corresponding to the European Middle Ages. The period is characterized by the expansion of civilizations geographically and development of trade ...

and modern heroes, on the other hand, perform great deeds or selfless acts for the common good instead of the classical goal of wealth, pride, and fame. The antonym of ''hero'' is ''villain

A villain (also known as a " black hat" or "bad guy"; the feminine form is villainess) is a stock character, whether based on a historical narrative or one of literary fiction. ''Random House Unabridged Dictionary'' defines such a character ...

''. Other terms associated with the concept of ''hero'' may include ''good guy'' or ''white hat

White hat, white hats, or white-hat may refer to:

Art, entertainment, and media

* White hat, a way of thinking in Edward de Bono's book ''Six Thinking Hats''

* White hat, part of black and white hat symbolism in film

Other uses

* White hat (compu ...

''.

In classical literature, the hero is the main or revered character in heroic epic poetry celebrated through ancient legend

A legend is a genre of folklore that consists of a narrative featuring human actions, believed or perceived, both by teller and listeners, to have taken place in human history. Narratives in this genre may demonstrate human values, and possess ...

s of a people, often striving for military conquest and living by a continually flawed personal honor code. The definition of a hero has changed throughout time. Merriam Webster dictionary defines a hero as "a person who is admired for great or brave acts or fine qualities". Examples of heroes range from mythological figures, such as Gilgamesh

sux, , label=none

, image = Hero lion Dur-Sharrukin Louvre AO19862.jpg

, alt =

, caption = Possible representation of Gilgamesh as Master of Animals, grasping a lion in his left arm and snake in his right hand, in an Assy ...

, Achilles and Iphigenia, to historical and modern figures, such as Joan of Arc, Giuseppe Garibaldi, Sophie Scholl, Alvin York, Audie Murphy, and Chuck Yeager, and fictional "superheroes", including Superman, Spider-Man, Batman, and Captain America.

Etymology

The word ''hero'' comes from the Greek ἥρως (''hērōs''), "hero" (literally "protector" or "defender"), particularly one such as Heracles with divine ancestry or later given divine honors. Before the decipherment of Linear B the original form of the word was assumed to be *, ''hērōw-'', but the Mycenaean compound ''ti-ri-se-ro-e'' demonstrates the absence of -w-. Hero as a name appears in pre-Homeric Greek mythology, wherein Hero and Leander, Hero was a priestess of the goddess Aphrodite, in a myth that has been referred to often in literature.

According to ''The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language'', the Proto-Indo-European language, Proto-Indo-European root is ''*ser'' meaning "to protect". According to Eric Partridge in ''Origins'', the Greek word ''hērōs'' "is akin to" the Latin ''seruāre'', meaning ''to safeguard''. Partridge concludes, "The basic sense of both Hera and hero would therefore be 'protector'." Robert S. P. Beekes, R. S. P. Beekes rejects an Indo-European derivation and asserts that the word has a Pre-Greek substrate, Pre-Greek origin. Hera was a Greek goddess with many attributes, including protection and her worship appears to have similar proto-Indo-European origins.

The word ''hero'' comes from the Greek ἥρως (''hērōs''), "hero" (literally "protector" or "defender"), particularly one such as Heracles with divine ancestry or later given divine honors. Before the decipherment of Linear B the original form of the word was assumed to be *, ''hērōw-'', but the Mycenaean compound ''ti-ri-se-ro-e'' demonstrates the absence of -w-. Hero as a name appears in pre-Homeric Greek mythology, wherein Hero and Leander, Hero was a priestess of the goddess Aphrodite, in a myth that has been referred to often in literature.

According to ''The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language'', the Proto-Indo-European language, Proto-Indo-European root is ''*ser'' meaning "to protect". According to Eric Partridge in ''Origins'', the Greek word ''hērōs'' "is akin to" the Latin ''seruāre'', meaning ''to safeguard''. Partridge concludes, "The basic sense of both Hera and hero would therefore be 'protector'." Robert S. P. Beekes, R. S. P. Beekes rejects an Indo-European derivation and asserts that the word has a Pre-Greek substrate, Pre-Greek origin. Hera was a Greek goddess with many attributes, including protection and her worship appears to have similar proto-Indo-European origins.

Antiquity

A classical hero is considered to be a "warrior who lives and dies in the pursuit of honor" and asserts their greatness by "the brilliancy and efficiency with which they kill". Each classical hero's life focuses on fighting, which occurs in war or during an epic quest. Classical heroes are commonly semi-divine and extraordinarily gifted, such as Achilles, evolving into heroic characters through their perilous circumstances. While these heroes are incredibly resourceful and skilled, they are often foolhardy, court disaster, risk their followers' lives for trivial matters, and behave arrogantly in a childlike manner. During classical times, people regarded heroes with the highest esteem and utmost importance, explaining their prominence within epic literature. The appearance of these mortal figures marks a revolution of audiences and writers turning away from Twelve Olympians, immortal gods to mortal mankind, whose heroic moments of glory survive in the memory of their descendants, extending their legacy.

Hector was a Troy, Trojan prince and the greatest fighter for Troy in the Trojan War, which is known primarily through Homer's ''Iliad''. Hector acted as leader of the Trojans and their allies in the defense of Troy, "killing 31,000 Greek fighters," offers Hyginus. Hector was known not only for his courage, but also for his noble and courtly nature. Indeed, Homer places Hector as peace-loving, thoughtful, as well as bold, a good son, husband and father, and without darker motives. However, his familial values conflict greatly with his heroic aspirations in the ''Iliad,'' as he cannot be both the protector of Troy and a father to his child. Hector is ultimately betrayed by the deities when Athena appears disguised as his ally Deiphobus and convinces him challenge Achilles, leading to his death at the hands of a superior warrior.Homer. ''The Iliad.'' Trans. Robert Fagles (1990). NY: Penguin Books. Chapter 14

A classical hero is considered to be a "warrior who lives and dies in the pursuit of honor" and asserts their greatness by "the brilliancy and efficiency with which they kill". Each classical hero's life focuses on fighting, which occurs in war or during an epic quest. Classical heroes are commonly semi-divine and extraordinarily gifted, such as Achilles, evolving into heroic characters through their perilous circumstances. While these heroes are incredibly resourceful and skilled, they are often foolhardy, court disaster, risk their followers' lives for trivial matters, and behave arrogantly in a childlike manner. During classical times, people regarded heroes with the highest esteem and utmost importance, explaining their prominence within epic literature. The appearance of these mortal figures marks a revolution of audiences and writers turning away from Twelve Olympians, immortal gods to mortal mankind, whose heroic moments of glory survive in the memory of their descendants, extending their legacy.

Hector was a Troy, Trojan prince and the greatest fighter for Troy in the Trojan War, which is known primarily through Homer's ''Iliad''. Hector acted as leader of the Trojans and their allies in the defense of Troy, "killing 31,000 Greek fighters," offers Hyginus. Hector was known not only for his courage, but also for his noble and courtly nature. Indeed, Homer places Hector as peace-loving, thoughtful, as well as bold, a good son, husband and father, and without darker motives. However, his familial values conflict greatly with his heroic aspirations in the ''Iliad,'' as he cannot be both the protector of Troy and a father to his child. Hector is ultimately betrayed by the deities when Athena appears disguised as his ally Deiphobus and convinces him challenge Achilles, leading to his death at the hands of a superior warrior.Homer. ''The Iliad.'' Trans. Robert Fagles (1990). NY: Penguin Books. Chapter 14 Achilles was a Greek hero who was considered the most formidable military fighter in the entire Trojan War and the central character of the ''Iliad''. He was the child of Thetis and Peleus, making him a Demigod, demi-god. He wielded superhuman strength on the battlefield and was blessed with a close relationship to the List of Greek mythological figures#Immortals, deities. Achilles famously refused to fight after his dishonoring at the hands of Agamemnon, and only returned to the war due to unadulterated rage after Hector killed his beloved companion Patroclus. Achilles was known for uncontrollable rage that defined many of his bloodthirsty actions, such as defiling Hector's corpse by dragging it around the city of Troy. Achilles plays a tragic role in the ''Iliad'' brought about by constan

Achilles was a Greek hero who was considered the most formidable military fighter in the entire Trojan War and the central character of the ''Iliad''. He was the child of Thetis and Peleus, making him a Demigod, demi-god. He wielded superhuman strength on the battlefield and was blessed with a close relationship to the List of Greek mythological figures#Immortals, deities. Achilles famously refused to fight after his dishonoring at the hands of Agamemnon, and only returned to the war due to unadulterated rage after Hector killed his beloved companion Patroclus. Achilles was known for uncontrollable rage that defined many of his bloodthirsty actions, such as defiling Hector's corpse by dragging it around the city of Troy. Achilles plays a tragic role in the ''Iliad'' brought about by constande-humanization

throughout the epic, having his ''menis'' (wrath) overpower his ''philos'' (love). Heroes in myth often had close, but conflicted relationships with the deities. Thus Heracles's name means "the glory of Hera", even though he was tormented all his life by Hera, the Queen of the Greek deities. Perhaps the most striking example is the Athenian king Erechtheus, whom Poseidon killed for choosing Athena rather than him as the city's patron deity. When the Athenians worshiped Erechtheus on the Acropolis of Athens, Acropolis, they invoked him as ''Poseidon Erechtheus''. Destiny, Fate, or destiny, plays a massive role in the stories of classical heroes. The classical hero's heroic significance stems from battlefield conquests, an inherently dangerous action. The deities in Greek mythology, when interacting with the heroes, often foreshadow the hero's eventual death on the battlefield. Countless heroes and deities go to great lengths to alter their pre-destined fates, but with no success, as none, neither human or immortal can change their prescribed outcomes by the three powerful Fates. The most characteristic example of this is found in ''Oedipus Rex.'' After learning that his son, Oedipus, will end up killing him, the King of Thebes, Laius, takes huge steps to assure his son's death by removing him from the kingdom. When Oedipus encounters his father when his father was unknown to him in a dispute on the road many years later, Oedipus slays him without an afterthought. The lack of recognition enabled Oedipus to slay his father, ironically further binding his father to his fate. Stories of heroism may serve as moral examples. However, classical heroes often didn't embody the Christian notion of an upstanding, perfectly moral hero. For example, Achilles's character-issues of hateful rage lead to merciless slaughter and his overwhelming pride lead to him only joining the Trojan War because he didn't want his soldiers to win all of the glory. Classical heroes, regardless of their morality, were placed in religion. In classical antiquity, cults that venerated deified heroes such as Heracles, Perseus, and Achilles played an important role in Ancient Greek religion.Graf, Fritz. (2006) "Hero Cult".

Brills New Pauly

'. These ancient Greek hero cults worshipped heroes from oral Epic Cycle, epic tradition, with these heroes often bestowing blessings, especially healing ones, on individuals.

Myth and monomyth

The concept of the "Mythic Hero Archetype" was first developed by FitzRoy Somerset, 4th Baron Raglan, Lord Raglan in his 1936 book, ''The Hero, A Study in Tradition, Myth and Drama''. It is a set of 22 common traits that he said were shared by many heroes in various cultures, myths, and religions throughout history and around the world. Raglan argued that the higher the score, the more likely the figure is mythical.

The concept of a story archetype of the standard Hero's journey, monomythical "hero's quest" that was reputed to be pervasive across all cultures, is somewhat controversial. Expounded mainly by Joseph Campbell in his 1949 work ''The Hero with a Thousand Faces'', it illustrates several uniting themes of hero stories that hold similar ideas of what a hero represents, despite vastly different cultures and beliefs. The monomyth or Hero's Journey consists of three separate stages including the Departure, Initiation, and Return. Within these stages there are several archetypes that the hero of either gender may follow, including the call to adventure (which they may initially refuse), supernatural aid, proceeding down a road of trials, achieving a realization about themselves (or an apotheosis), and attaining the freedom to live through their quest or journey. Campbell offered examples of stories with similar themes such as Krishna, Gautama Buddha, Buddha, Apollonius of Tyana, and Jesus.Joseph Campbell in ''The Hero With a Thousand Faces'' Princeton University Press, 2004 [1949], 140, One of the themes he explores is the androgynous hero, who combines male and female traits, such as Bodhisattva: "The first wonder to be noted here is the androgynous character of the Bodhisattva: masculine Avalokiteshvara, feminine Kwan Yin." In his 1968 book, ''The Masks of God: Occidental Mythology'', Campbell writes, "It is clear that, whether accurate or not as to biographical detail, the moving legend of the Crucified and Risen Christ was fit to bring a new warmth, immediacy, and humanity, to the old motifs of the beloved Dumuzid, Tammuz, Adonis, and Osiris cycles."

The concept of the "Mythic Hero Archetype" was first developed by FitzRoy Somerset, 4th Baron Raglan, Lord Raglan in his 1936 book, ''The Hero, A Study in Tradition, Myth and Drama''. It is a set of 22 common traits that he said were shared by many heroes in various cultures, myths, and religions throughout history and around the world. Raglan argued that the higher the score, the more likely the figure is mythical.

The concept of a story archetype of the standard Hero's journey, monomythical "hero's quest" that was reputed to be pervasive across all cultures, is somewhat controversial. Expounded mainly by Joseph Campbell in his 1949 work ''The Hero with a Thousand Faces'', it illustrates several uniting themes of hero stories that hold similar ideas of what a hero represents, despite vastly different cultures and beliefs. The monomyth or Hero's Journey consists of three separate stages including the Departure, Initiation, and Return. Within these stages there are several archetypes that the hero of either gender may follow, including the call to adventure (which they may initially refuse), supernatural aid, proceeding down a road of trials, achieving a realization about themselves (or an apotheosis), and attaining the freedom to live through their quest or journey. Campbell offered examples of stories with similar themes such as Krishna, Gautama Buddha, Buddha, Apollonius of Tyana, and Jesus.Joseph Campbell in ''The Hero With a Thousand Faces'' Princeton University Press, 2004 [1949], 140, One of the themes he explores is the androgynous hero, who combines male and female traits, such as Bodhisattva: "The first wonder to be noted here is the androgynous character of the Bodhisattva: masculine Avalokiteshvara, feminine Kwan Yin." In his 1968 book, ''The Masks of God: Occidental Mythology'', Campbell writes, "It is clear that, whether accurate or not as to biographical detail, the moving legend of the Crucified and Risen Christ was fit to bring a new warmth, immediacy, and humanity, to the old motifs of the beloved Dumuzid, Tammuz, Adonis, and Osiris cycles."

Slavic fairy tales

Vladimir Propp, in his analysis of Russian fairy tales, concluded that a fairy tale had only eight ''dramatis personæ'', of which one was the hero,Vladimir Propp, ''Morphology of the Folk Tale'', and his analysis has been widely applied to non-Russian folklore. The actions that fall into such a hero's sphere include:

# Departure on a quest

# Reacting to the test of a Donor (fairy tale), donor

# Marrying a princess (or similar figure)

Propp distinguished between ''seekers'' and ''victim-heroes''. A

Vladimir Propp, in his analysis of Russian fairy tales, concluded that a fairy tale had only eight ''dramatis personæ'', of which one was the hero,Vladimir Propp, ''Morphology of the Folk Tale'', and his analysis has been widely applied to non-Russian folklore. The actions that fall into such a hero's sphere include:

# Departure on a quest

# Reacting to the test of a Donor (fairy tale), donor

# Marrying a princess (or similar figure)

Propp distinguished between ''seekers'' and ''victim-heroes''. A villain

A villain (also known as a " black hat" or "bad guy"; the feminine form is villainess) is a stock character, whether based on a historical narrative or one of literary fiction. ''Random House Unabridged Dictionary'' defines such a character ...

could initiate the issue by kidnapping the hero or driving him out; these were victim-heroes. On the other hand, an antagonist could rob the hero, or kidnap someone close to him, or, without the villain's intervention, the hero could realize that he lacked something and set out to find it; these heroes are seekers. Victims may appear in tales with seeker heroes, but the tale does not follow them both.

Historical studies

No history can be written without consideration of the lengthy list of List of medals for bravery, recipients of national medals for bravery, populated by firefighters, policemen and policewomen, ambulance medics, and ordinary have-a-go heroes. These persons risked their lives to try to save or protect the lives of others: for example, the Canadian Cross of Valour (Canada), Cross of Valour (C.V.) "recognizes acts of the most conspicuous courage in circumstances of extreme peril"; examples of recipients are Mary Dohey and David Gordon Cheverie.

The philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Hegel gave a central role to the "hero", personalized by Napoleon, as the incarnation of a particular culture's ''Geist#Volksgeist, Volksgeist'', and thus of the general ''Zeitgeist''. Thomas Carlyle's 1841 work, ''On Heroes, Hero-Worship, & the Heroic in History'', also accorded a key function to heroes and great men in history. Carlyle centered history on the biography, biographies of individuals, as in ''Oliver Cromwell's Letters and Speeches'' and ''History of Frederick the Great''. His heroes were not only political and military figures, the founders or topplers of states, but also religious figures, poets, authors, and captains of industry.

Explicit defenses of Carlyle's position were rare in the second part of the 20th century. Most in the philosophy of history school contend that the motive forces in history may best be described only with a wider lens than the one that Carlyle used for his portraits. For example, Karl Marx argued that history was determined by the massive social forces at play in "Class conflict, class struggles", not by the individuals by whom these forces are played out. After Marx, Herbert Spencer wrote at the end of the 19th century: "You must admit that the genesis of the great man depends on the long series of complex influences which has produced the race in which he appears, and the social state into which that race has slowly grown...[b]efore he can remake his society, his society must make him."Spencer, Herbert.

No history can be written without consideration of the lengthy list of List of medals for bravery, recipients of national medals for bravery, populated by firefighters, policemen and policewomen, ambulance medics, and ordinary have-a-go heroes. These persons risked their lives to try to save or protect the lives of others: for example, the Canadian Cross of Valour (Canada), Cross of Valour (C.V.) "recognizes acts of the most conspicuous courage in circumstances of extreme peril"; examples of recipients are Mary Dohey and David Gordon Cheverie.

The philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Hegel gave a central role to the "hero", personalized by Napoleon, as the incarnation of a particular culture's ''Geist#Volksgeist, Volksgeist'', and thus of the general ''Zeitgeist''. Thomas Carlyle's 1841 work, ''On Heroes, Hero-Worship, & the Heroic in History'', also accorded a key function to heroes and great men in history. Carlyle centered history on the biography, biographies of individuals, as in ''Oliver Cromwell's Letters and Speeches'' and ''History of Frederick the Great''. His heroes were not only political and military figures, the founders or topplers of states, but also religious figures, poets, authors, and captains of industry.

Explicit defenses of Carlyle's position were rare in the second part of the 20th century. Most in the philosophy of history school contend that the motive forces in history may best be described only with a wider lens than the one that Carlyle used for his portraits. For example, Karl Marx argued that history was determined by the massive social forces at play in "Class conflict, class struggles", not by the individuals by whom these forces are played out. After Marx, Herbert Spencer wrote at the end of the 19th century: "You must admit that the genesis of the great man depends on the long series of complex influences which has produced the race in which he appears, and the social state into which that race has slowly grown...[b]efore he can remake his society, his society must make him."Spencer, Herbert. The Study of Sociology

', Appleton, 1896, p. 34. Michel Foucault argued in Philosophy of history#Michel Foucault's analysis of historical and political discourse, his analysis of societal communication and debate that history was mainly the "science of the Sovereignty, sovereign", until its inversion by the "historical and political popular discourse".

Modern examples of the typical hero are, Minnie Vautrin, Norman Bethune, Alan Turing, Raoul Wallenberg, Chiune Sugihara, Martin Luther King Jr., Mother Teresa, Nelson Mandela, Oswaldo Payá, Óscar Elías Biscet, and Aung San Suu Kyi.

The Annales school, led by Lucien Febvre, Marc Bloch, and Fernand Braudel, would contest the exaggeration of the role of Subject (philosophy), individual subjects in history. Indeed, Braudel distinguished various time scales, one accorded to the life of an individual, another accorded to the life of a few human generations, and the last one to civilizations, in which geography, economics, and demography play a role considerably more decisive than that of individual subjects.

Among noticeable events in the studies of the role of the hero and Great man theory, great man in history one should mention Sidney Hook's book (1943) ''Sidney Hook#Hero in History, The Hero in History''. In the second half of the twentieth century such male-focused theory has been contested, among others by feminists writers such as Judith Fetterley in ''The Resisting Reader'' (1977) and literary theorist Nancy K. Miller, ''The Heroine's Text: Readings in the French and English Novel, 1722–1782''.

In the epoch of globalization an individual may change the development of the country and of the whole world, so this gives reasons to some scholars to suggest returning to the problem of the role of the hero in history from the viewpoint of modern historical knowledge and using up-to-date methods of historical analysis.

Within the frameworks of developing counterfactual history, attempts are made to examine some hypothetical scenarios of historical development. The hero attracts much attention because most of those scenarios are based on the suppositions: what would have happened if this or that historical individual had or had not been alive.

Modern examples of the typical hero are, Minnie Vautrin, Norman Bethune, Alan Turing, Raoul Wallenberg, Chiune Sugihara, Martin Luther King Jr., Mother Teresa, Nelson Mandela, Oswaldo Payá, Óscar Elías Biscet, and Aung San Suu Kyi.

The Annales school, led by Lucien Febvre, Marc Bloch, and Fernand Braudel, would contest the exaggeration of the role of Subject (philosophy), individual subjects in history. Indeed, Braudel distinguished various time scales, one accorded to the life of an individual, another accorded to the life of a few human generations, and the last one to civilizations, in which geography, economics, and demography play a role considerably more decisive than that of individual subjects.

Among noticeable events in the studies of the role of the hero and Great man theory, great man in history one should mention Sidney Hook's book (1943) ''Sidney Hook#Hero in History, The Hero in History''. In the second half of the twentieth century such male-focused theory has been contested, among others by feminists writers such as Judith Fetterley in ''The Resisting Reader'' (1977) and literary theorist Nancy K. Miller, ''The Heroine's Text: Readings in the French and English Novel, 1722–1782''.

In the epoch of globalization an individual may change the development of the country and of the whole world, so this gives reasons to some scholars to suggest returning to the problem of the role of the hero in history from the viewpoint of modern historical knowledge and using up-to-date methods of historical analysis.

Within the frameworks of developing counterfactual history, attempts are made to examine some hypothetical scenarios of historical development. The hero attracts much attention because most of those scenarios are based on the suppositions: what would have happened if this or that historical individual had or had not been alive.

Modern fiction

Psychology

Social psychology has begun paying attention to heroes and heroism. Zeno Franco and Philip Zimbardo point out differences between heroism and altruism, and they offer evidence that observer perceptions of unjustified risk play a role above and beyond risk type in determining the ascription of heroic status. Psychologists have also identified the traits of heroes. Elaine Kinsella and her colleagues have identified 12 central traits of heroism, which consist of brave, moral integrity, conviction, courageous, self-sacrifice, protecting, honest, selfless, determined, saves others, inspiring, and helpful. Scott Allison and George Goethals uncovered evidence for "the great eight traits" of heroes consisting of wise, strong, resilient, reliable, charismatic, caring, selfless, and inspiring. These researchers have also identified four primary functions of heroism. Heroes give us wisdom; they enhance us; they provide moral modeling; and they offer protection. An evolutionary psychology explanation for heroic risk-taking is that it is a Handicap principle, costly signal demonstrating the ability of the hero. It may be seen as one form of altruism for which there are several other evolutionary explanations as well.Pat Barcaly. The evolution of charitable behaviour and the power of reputation. In Hannes Rusch. High-cost altruistic helping. In Roma Chatterji has suggested that the hero or more generally protagonist is first and foremost a symbolic representation of the person who is experiencing the story while reading, listening, or watching; thus the relevance of the hero to the individual relies a great deal on how much similarity there is between them and the character. Chatterji suggested that one reason for the hero-as-self interpretation of stories and myths is the human inability to view the world from any perspective but a personal one. In the Pulitzer Prize-winning book, ''The Denial of Death'', Ernest Becker argues that human civilization is ultimately an elaborate, symbolic defense mechanism against the knowledge of our mortality, which in turn acts as the emotional and intellectual response to our basic Anti-predator adaptation, survival mechanism. Becker explains that a basic duality in human life exists between the physical world of objects and a symbolic world of human meaning. Thus, since humanity has a dualistic nature consisting of a physical self and a symbolic self, he asserts that humans are able to transcend the dilemma of mortality through heroism, by focusing attention mainly on the symbolic self. This symbolic self-focus takes the form of an individual's "immortality project" (or "''causa sui'' project"), which is essentially a symbolic belief-system that ensures that one is believed superior to physical reality. By successfully living under the terms of the immortality project, people feel they can become heroic and, henceforth, part of something eternal; something that will never die as compared to their physical body. This he asserts, in turn, gives people the feeling that their lives have meaning, a purpose, and are significant in the grand scheme of things. Another theme running throughout the book is that humanity's traditional "hero-systems", such as religion, are no longer convincing in the Age of Enlightenment, age of reason. Science attempts to serve as an immortality project, something that Becker believes it can never do, because it is unable to provide agreeable, absolute meanings to human life. The book states that we need new convincing "illusions" that enable people to feel heroic in ways that are agreeable. Becker, however, does not provide any definitive answer, mainly because he believes that there is no perfect solution. Instead, he hopes that gradual realization of humanity's innate motivations, namely death, may help to bring about a better world. Terror management theory, Terror Management Theory (TMT) has generated evidence supporting this perspective.Mental and physical integration

Examining the success of resistance fighters on Crete during the Axis occupation of Greece , Nazi occupation in WWII, author and endurance researcher Christopher McDougall , C. McDougall drew connections to the Ancient Greek heroes and a culture of integrated physical self-mastery, training, and mental conditioning that fostered confidence to take action, and made it possible for individuals to accomplish feats of great prowess, even under the harshest of conditions. The skills established an "...ability to unleash tremendous resources of strength, endurance, and agility that many people don’t realize they already have.” McDougall cites examples of heroic acts, including a ''scholium'' to Pindar’s Fifth Nemean Ode: “Much weaker in strength than the Minotaur, Theseus fought with it and won using ''pankration'', as he had no knife.” ''Pankration'' is an ancient Greek term meaning "total power and knowledge,” one "...associated with gods and heroes...who conquer by tapping every talent.”See also

* Action hero ** List of female action heroes and villains * Antihero * Byronic hero * Carnegie Hero Fund * Culture hero * Folk hero * Germanic hero * Hero and Leander * Hero of Socialist Labour * Heroic fantasy * List of genres * Randian hero * Reluctant hero * Romantic hero * Space opera * Tragic hero * YouxiaReferences

Further reading

* * * * * * * * Carlyle, Thomas (1840)On Heroes, Hero Worship and the Heroic in History

' * Craig, David, ''Back Home'', Life Magazine-Special Issue, Volume 8, Number 6, 85–94. * * * * * Hook, Sydney (1943) ''The Hero in History: A Study in Limitation and Possibility'' * * * Henry Liddell, Lidell, Henry and Robert Scott (philologist), Robert Scott. ''A Greek–English Lexicon.''

link

* * * (Republished 2003) * *

External links

nbsp;— online exhibition from screenonline, a website of the British Film Institute, looking at British heroes of film and television.

Listen to BBC Radio 4's ''In Our Time'' programme on Heroism

by Marilyn Price-Mitchell, PhD *

10% — What Makes A Hero

' directed by Yoav Shamir {{Authority control Heroes, Epic poetry Good and evil Fantasy tropes Jungian archetypes Literary archetypes Mythological archetypes Mythological characters Protagonists by role