Henry Villard on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Henry Villard (April 10, 1835 – November 12, 1900) was an

He was born in

He was born in

After attending

After attending

Villard had also had a hand in the large electric power business founded by

Villard had also had a hand in the large electric power business founded by

In January 1866, he married

In January 1866, he married

Reviewed here

'

online

deals largely with Villard. * *Kobrak, Christopher

"A Reputation for Cross-Cultural Business: Henry Villard and German Investment in the United States ."

In ''Immigrant Entrepreneurship: German-American Business Biographies, 1720 to the Present'', vol. 2, edited by William J. Hausman. German Historical Institute. Last modified September 30, 2015. * *

a more detailed biography

Henry Villard Business Papers at Baker Library Historical Collections, Harvard Business School

{{DEFAULTSORT:Villard, Henry 1835 births 1900 deaths 19th-century American railroad executives 19th-century American newspaper publishers (people) Bavarian emigrants to the United States American financiers History of transportation in Oregon New York Post people Northern Pacific Railway people People from Speyer People from the Palatinate (region) People from Belleville, Illinois Writers from Peoria, Illinois Businesspeople from Chicago Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich alumni University of Würzburg alumni Philanthropists from New York (state) American war correspondents American people of German descent Burials at Sleepy Hollow Cemetery New York (state) Republicans People from Dobbs Ferry, New York 19th-century American journalists Writers from Chicago The Nation (U.S. magazine) people American male journalists 19th-century American male writers Journalists from Illinois Philanthropists from Illinois 19th-century American philanthropists

American

American(s) may refer to:

* American, something of, from, or related to the United States of America, commonly known as the "United States" or "America"

** Americans, citizens and nationals of the United States of America

** American ancestry, pe ...

journalist

A journalist is an individual that collects/gathers information in form of text, audio, or pictures, processes them into a news-worthy form, and disseminates it to the public. The act or process mainly done by the journalist is called journalis ...

and financier who was an early president of the Northern Pacific Railway

The Northern Pacific Railway was a transcontinental railroad that operated across the northern tier of the western United States, from Minnesota to the Pacific Northwest. It was approved by Congress in 1864 and given nearly of land grants, wh ...

.

Born and raised by Ferdinand Heinrich Gustav Hilgard in the Rhenish Palatinate of the Kingdom of Bavaria

The Kingdom of Bavaria (german: Königreich Bayern; ; spelled ''Baiern'' until 1825) was a German state that succeeded the former Electorate of Bavaria in 1805 and continued to exist until 1918. With the unification of Germany into the German ...

, Villard clashed with his more conservative father over politics, and was sent to a semi-military academy in northeastern France. As a teenager, he emigrated to the United States without his parents' knowledge. He changed his name to avoid being sent back to Europe, and began making his way west, briefly studying law as he developed a career in journalism. He supported John C. Frémont

John Charles Frémont or Fremont (January 21, 1813July 13, 1890) was an American explorer, military officer, and politician. He was a U.S. Senator from California and was the first Republican nominee for president of the United States in 1856 ...

of the newly established Republican Party

Republican Party is a name used by many political parties around the world, though the term most commonly refers to the United States' Republican Party.

Republican Party may also refer to:

Africa

* Republican Party (Liberia)

*Republican Party ...

in his presidential campaign in 1856, and later followed Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation throu ...

's 1860 campaign.

Villard became a war correspondent, first covering the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

, and later being sent by the ''Chicago Tribune

The ''Chicago Tribune'' is a daily newspaper based in Chicago, Illinois, United States, owned by Tribune Publishing. Founded in 1847, and formerly self-styled as the "World's Greatest Newspaper" (a slogan for which WGN radio and television ar ...

'' to cover the Austro-Prussian War

The Austro-Prussian War, also by many variant names such as Seven Weeks' War, German Civil War, Brothers War or Fraternal War, known in Germany as ("German War"), (; "German war of brothers") and by a variety of other names, was fought in 186 ...

. He became a pacifist as a result of his experiences covering the Civil War. In the late 1860s he married women's suffrage

Women's suffrage is the right of women to vote in elections. Beginning in the start of the 18th century, some people sought to change voting laws to allow women to vote. Liberal political parties would go on to grant women the right to vot ...

advocate Helen Frances Garrison, and returned to the U.S., only to go back to Germany for his health in 1870.

While in Germany, Villard became involved in investments in American railroads, and returned to the U.S. in 1874 to oversee German investments in the Oregon and California Railroad. He visited Oregon that summer, and being impressed with the region's natural resources, began acquiring various transportation interests in the region. During the ensuing decade he acquired several rail and steamship companies, and pursued a rail line from Portland to the Pacific Ocean; he was successful, but the line cost more than anticipated, causing financial turmoil. Villard returned to Europe, helping German investors acquire stakes in the transportation network, and returned to New York in 1886.

Also in the 1880s, Villard acquired the '' New York Evening Post'' and ''The Nation

''The Nation'' is an American liberal biweekly magazine that covers political and cultural news, opinion, and analysis. It was founded on July 6, 1865, as a successor to William Lloyd Garrison's '' The Liberator'', an abolitionist newspaper t ...

'', and established the predecessor of General Electric

General Electric Company (GE) is an American multinational conglomerate founded in 1892, and incorporated in New York state and headquartered in Boston. The company operated in sectors including healthcare, aviation, power, renewable ene ...

. He was the first benefactor of the University of Oregon

The University of Oregon (UO, U of O or Oregon) is a public research university in Eugene, Oregon. Founded in 1876, the institution is well known for its strong ties to the sports apparel and marketing firm Nike, Inc

Nike, Inc. ( or ) is a ...

, and contributed to other universities, churches, hospitals, and orphanages. He died of a stroke at his country home in New York in 1900.

Early life and education

He was born in

He was born in Speyer

Speyer (, older spelling ''Speier'', French: ''Spire,'' historical English: ''Spires''; pfl, Schbaija) is a city in Rhineland-Palatinate in Germany with approximately 50,000 inhabitants. Located on the left bank of the river Rhine, Speyer lie ...

, Palatinate, Kingdom of Bavaria

The Kingdom of Bavaria (german: Königreich Bayern; ; spelled ''Baiern'' until 1825) was a German state that succeeded the former Electorate of Bavaria in 1805 and continued to exist until 1918. With the unification of Germany into the German ...

. His parents moved to Zweibrücken

Zweibrücken (; french: Deux-Ponts, ; Palatinate German: ''Zweebrigge'', ; literally translated as "Two Bridges") is a town in Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany, on the Schwarzbach river.

Name

The name ''Zweibrücken'' means 'two bridges'; old ...

in 1839, and in 1856 his father, Gustav Leonhard Hilgard (who died in 1867), became a justice of the Supreme Court of Bavaria, at Munich. He belonged to the Reformed Church. His mother, Katharina Antonia Elisabeth (Lisette) Pfeiffer, was Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

. While he had aristocratic tendencies, he shared the republican interests of much of the Hilgard clan. His granduncle Theodore Erasmus Hilgard Theodore Erasmus Hilgard (7 July 1790, Marnheim – 14 February 1873, Heidelberg) was a lawyer, viticulturalist and Latin farmer.

Europe

He grew up during the Napoleonic Wars in a family very sympathetic to the principles of the French revolu ...

had emigrated to the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

during a clan move of 1833-1835 to Belleville, Illinois; the granduncle had resigned a judgeship so his children could be raised as "freemen." Villard was also a distant relative of the physician and botanist George Engelmann

George Engelmann, also known as Georg Engelmann, (2 February 1809 – 4 February 1884) was a German-American botanist. He was instrumental in describing the flora of the west of North America, then very poorly known to Europeans; he was particul ...

who resided in St. Louis, Missouri.

Villard entered a '' Gymnasium'' (equivalent of a United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

high school

A secondary school describes an institution that provides secondary education and also usually includes the building where this takes place. Some secondary schools provide both '' lower secondary education'' (ages 11 to 14) and ''upper seconda ...

) in Zweibrücken in 1848, which he had to leave because he sympathized with the revolutions of 1848 in Germany

In political science, a revolution (Latin: ''revolutio'', "a turn around") is a fundamental and relatively sudden change in political power and political organization which occurs when the population revolts against the government, typically due ...

. He had broken up a class by refusing to mention the King of Bavaria in a prayer, justifying his omission by citing his loyalty to the provisional government. Another time, after watching a session of the Frankfurt Parliament, he came home in a Hecker hat with a red feather in it. Two of his uncles were strongly in sympathy with the revolution, but his father was a conservative, and disciplined him by sending the boy to continue his education at the French semi-military academy in Phalsbourg (1849–50).

Originally his punishment was to be apprenticed, but his father compromised on the military school. Villard showed up for classes a month early so he could be tutored in the French language

French ( or ) is a Romance language of the Indo-European family. It descended from the Vulgar Latin of the Roman Empire, as did all Romance languages. French evolved from Gallo-Romance, the Latin spoken in Gaul, and more specifically in N ...

beforehand by the novelist Alexandre Chatrian.

Career

Journalism

On emigrating to America, he adopted the name Villard, the surname of a French schoolmate at Phalsbourg, to conceal his identity from anyone intent on making him return to Germany. Making his way westward in 1854, he lived in turn atCincinnati

Cincinnati ( ) is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Hamilton County. Settled in 1788, the city is located at the northern side of the confluence of the Licking and Ohio rivers, the latter of which marks the state line w ...

; Belleville, Illinois, and Peoria, Illinois

Peoria ( ) is the county seat of Peoria County, Illinois, United States, and the largest city on the Illinois River. As of the 2020 census, the city had a population of 113,150. It is the principal city of the Peoria Metropolitan Area in Ce ...

, where he studied law for a time; and Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = List of sovereign states, Count ...

where he wrote for newspaper

A newspaper is a periodical publication containing written information about current events and is often typed in black ink with a white or gray background.

Newspapers can cover a wide variety of fields such as politics, business, spor ...

s. Along with newspaper reporting and various jobs, in 1856 he attempted unsuccessfully to establish a colony of " free soil" Germans in Kansas

Kansas () is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern United States. Its Capital city, capital is Topeka, Kansas, Topeka, and its largest city is Wichita, Kansas, Wichita. Kansas is a landlocked state bordered by Nebras ...

. In 1856-57 he was editor, and for part of the time was proprietor of the Racine

Jean-Baptiste Racine ( , ) (; 22 December 163921 April 1699) was a French dramatist, one of the three great playwrights of 17th-century France, along with Molière and Corneille as well as an important literary figure in the Western traditi ...

''Volksblatt'', in which he advocated the election of presidential candidate John C. Frémont

John Charles Frémont or Fremont (January 21, 1813July 13, 1890) was an American explorer, military officer, and politician. He was a U.S. Senator from California and was the first Republican nominee for president of the United States in 1856 ...

of the newly founded Republican Party

Republican Party is a name used by many political parties around the world, though the term most commonly refers to the United States' Republican Party.

Republican Party may also refer to:

Africa

* Republican Party (Liberia)

*Republican Party ...

.

Thereafter he was associated with the '' New Yorker Staats-Zeitung'', for which he covered the Lincoln-Douglas debates; '' Frank Leslie's''; the ''New York Tribune

The ''New-York Tribune'' was an American newspaper founded in 1841 by editor Horace Greeley. It bore the moniker ''New-York Daily Tribune'' from 1842 to 1866 before returning to its original name. From the 1840s through the 1860s it was the domi ...

''; and with the ''Cincinnati Commercial Gazette''. In 1859, as correspondent of the ''Commercial'', he visited the newly discovered gold region of Colorado

Colorado (, other variants) is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It encompasses most of the Southern Rocky Mountains, as well as the northeastern portion of the Colorado Plateau and the western edge of the ...

. On his return in 1860, he published ''The Pike's Peak Gold Regions''. He also sent statistics to the New York ''Herald'' that were intended to influence the location of a Pacific railroad

Rail transport (also known as train transport) is a means of transport that transfers passengers and goods on wheeled vehicles running on rails, which are incorporated in tracks. In contrast to road transport, where the vehicles run on a prep ...

route. He followed Lincoln throughout the 1860 presidential campaign, and was on the presidential train to Washington in 1861. He was correspondent of the ''New York Herald

The ''New York Herald'' was a large-distribution newspaper based in New York City that existed between 1835 and 1924. At that point it was acquired by its smaller rival the '' New-York Tribune'' to form the '' New York Herald Tribune''.

Hi ...

'' in 1861.

During the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polici ...

, he was correspondent for the ''New York Tribune'' (with the Army of the Potomac

The Army of the Potomac was the principal Union Army in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was created in July 1861 shortly after the First Battle of Bull Run and was disbanded in June 1865 following the surrender of the Confede ...

, 1862–63) and was at the front as the representative of a news agency established by him in that year at Washington

Washington commonly refers to:

* Washington (state), United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A metonym for the federal government of the United States

** Washington metropolitan area, the metropolitan area centered o ...

(1864). Out of his experiences reporting the Civil War, he became a confirmed pacifist. In 1865, when Horace White became managing editor of the ''Chicago Tribune

The ''Chicago Tribune'' is a daily newspaper based in Chicago, Illinois, United States, owned by Tribune Publishing. Founded in 1847, and formerly self-styled as the "World's Greatest Newspaper" (a slogan for which WGN radio and television ar ...

'', Villard became its Washington correspondent. In 1866, he was the correspondent of that paper in the Prusso-Austrian War. He stayed on in Europe in 1867 to report on the Paris Exposition.

At the close of the Civil War, he married Helen Frances Garrison, the daughter of the anti-slavery campaigner William Lloyd Garrison

William Lloyd Garrison (December , 1805 – May 24, 1879) was a prominent American Christian, abolitionist, journalist, suffragist, and social reformer. He is best known for his widely read antislavery newspaper '' The Liberator'', which he fo ...

, on January 3, 1866.

He returned to the United States from his correspondent duties in Europe in June 1868, and shortly afterward was elected secretary of the American Social Science Association In 1865, at Boston, Massachusetts, a society for the study of social questions was organized and given the name American Social Science Association. The group grew to where its membership totaled about 1,000 persons. About 30 corresponding members ...

, to which he devoted his labors until 1870, when he went to Germany for his health.

Transportation

In Germany, while living atWiesbaden

Wiesbaden () is a city in central western Germany and the capital of the state of Hesse. , it had 290,955 inhabitants, plus approximately 21,000 United States citizens (mostly associated with the United States Army). The Wiesbaden urban area ...

, he engaged in the negotiation of American railroad securities. After the Panic of 1873, when many railroad companies defaulted in the payment of interest, he joined several committees of German bond holders, doing the major part of the committee work, and in April 1874 he returned to the United States to represent his constituents, and especially to execute an arrangement with the Oregon and California Railroad Company.

Villard first visited Portland, Oregon

Portland (, ) is a port city in the Pacific Northwest and the largest city in the U.S. state of Oregon. Situated at the confluence of the Willamette and Columbia rivers, Portland is the county seat of Multnomah County, the most populous ...

, in July 1874. On visiting Oregon, he was impressed with the natural wealth of the region, and conceived the plan of gaining control of its few transportation routes. His clients, who were also large creditors also of the Oregon Steamship Company, approved his scheme, and in 1875 Villard became president of both the steamship company and the Oregon and California Railroad. In 1876, he was appointed a receiver of the Kansas Pacific Railway

The Kansas Pacific Railway (KP) was a historic railroad company that operated in the western United States in the late 19th century. It was a federally chartered railroad, backed with government land grants. At a time when the first transcontin ...

as the representative of European creditors. He was removed in 1878, but continued the contest he had begun with Jay Gould and finally obtained better terms for the bond holders than they had agreed to accept.

The Pacific Northwest

The Pacific Northwest (sometimes Cascadia, or simply abbreviated as PNW) is a geographic region in western North America bounded by its coastal waters of the Pacific Ocean to the west and, loosely, by the Rocky Mountains to the east. Thou ...

was the booming sector of American expansion. European investors in the Oregon and San Francisco Steamship Line, after building new vessels, became discouraged, and in 1879 Villard formed an American syndicate and purchased the property. He also acquired that of the Oregon Steam Navigation Company, which operated fleets of steamers and portage railroads on the Columbia River

The Columbia River ( Upper Chinook: ' or '; Sahaptin: ''Nch’i-Wàna'' or ''Nchi wana''; Sinixt dialect'' '') is the largest river in the Pacific Northwest region of North America. The river rises in the Rocky Mountains of British Columbia ...

. The three companies that he controlled were amalgamated under the name of the Oregon Railroad and Navigation Company.

He began the construction of a railroad up Columbia River. On failing in his effort to obtain a permanent agreement with the Northern Pacific Railway

The Northern Pacific Railway was a transcontinental railroad that operated across the northern tier of the western United States, from Minnesota to the Pacific Northwest. It was approved by Congress in 1864 and given nearly of land grants, wh ...

, which had begun its extension into the Washington Territory, Villard used his Columbia River steamship line as his railroad's outlet to the Pacific Ocean. He then succeeded in obtaining a controlling interest in the Northern Pacific property, and organized a new corporation that was named the Oregon and Transcontinental Company. This acquisition was achieved with the aid of a syndicate, called by the press a "blind pool," composed of friends who had loaned him $20 million without knowing his intentions. After some contention with the old managers of the Northern Pacific road, Villard was elected president of a reorganized board of directors on 15 September 1881.

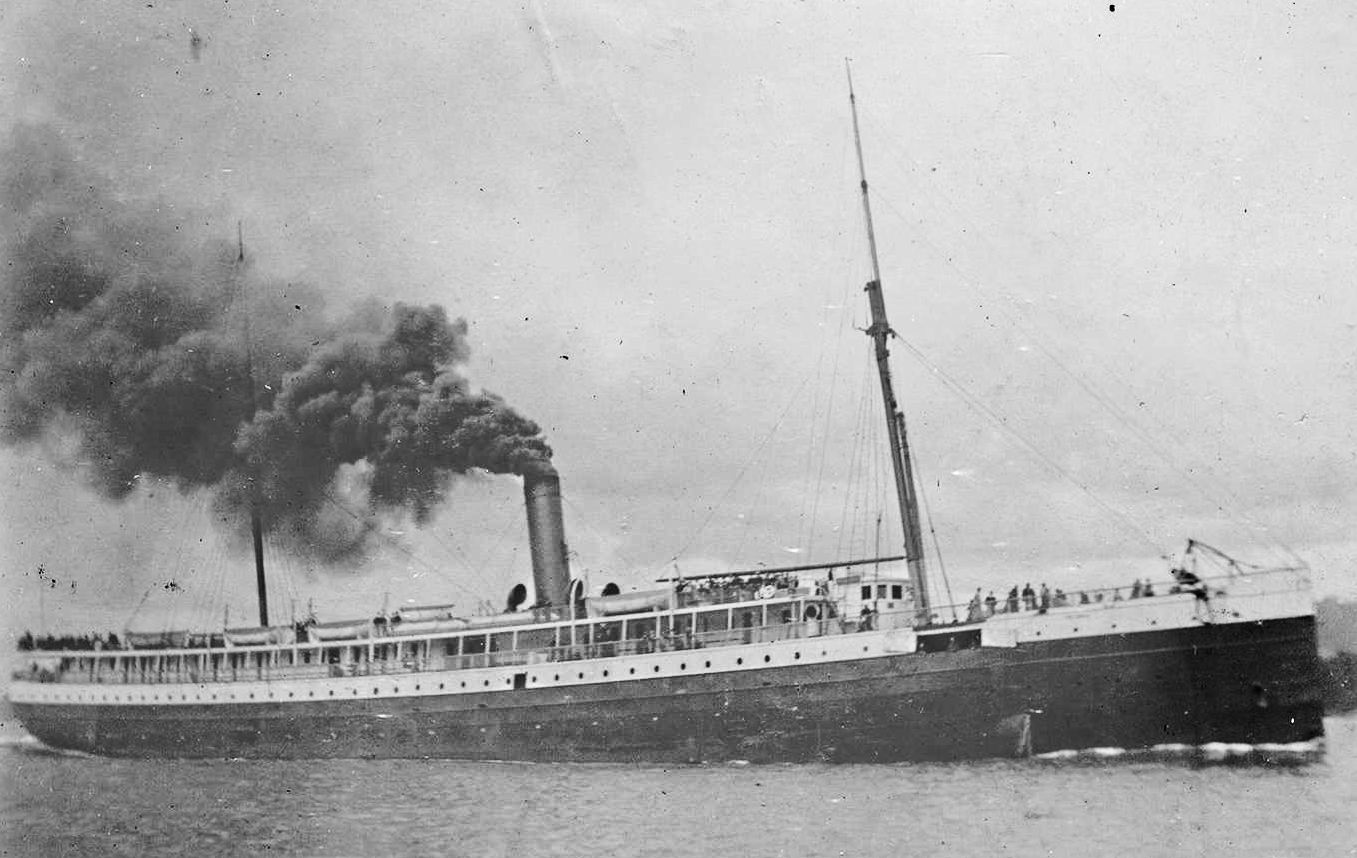

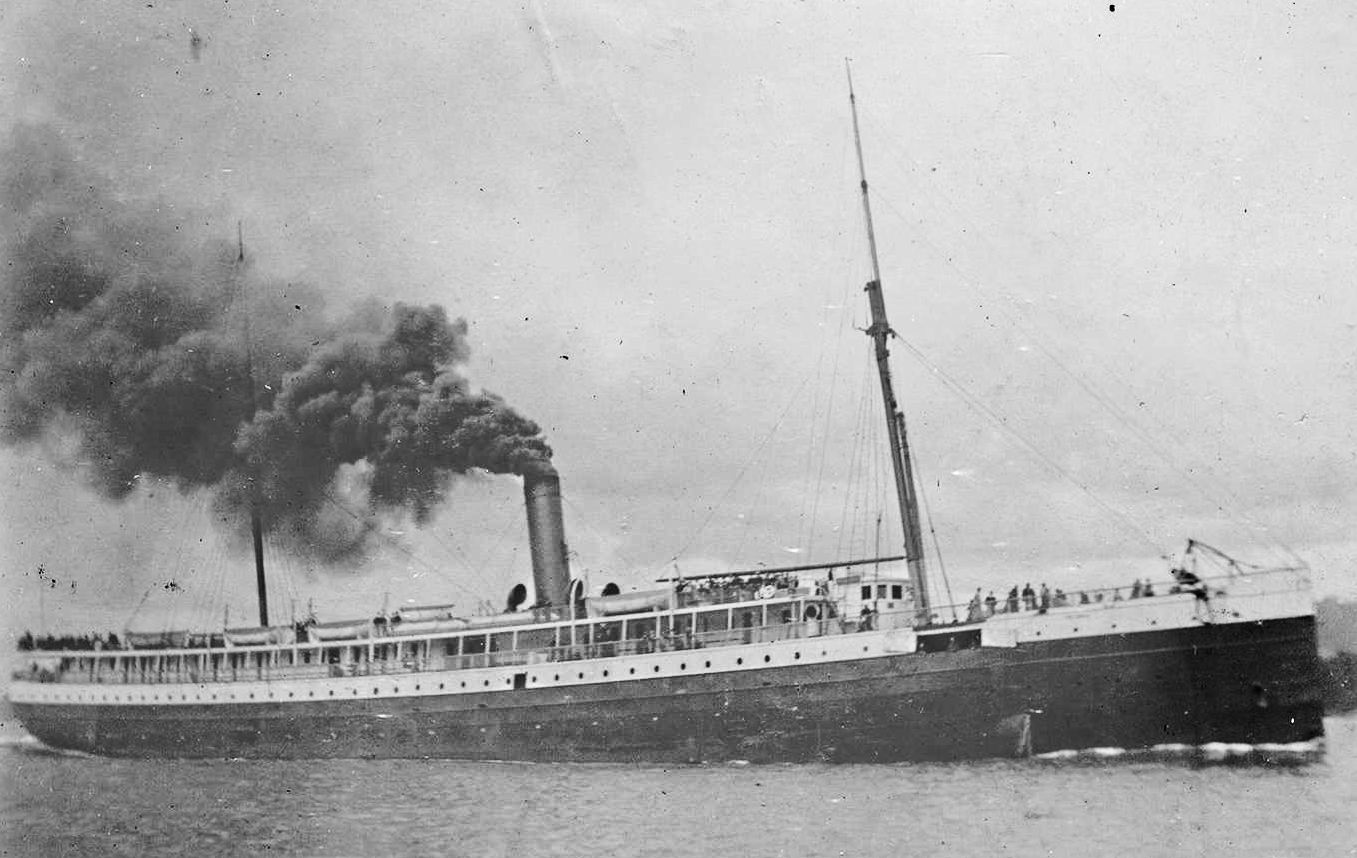

After attending

After attending Thomas Edison

Thomas Alva Edison (February 11, 1847October 18, 1931) was an American inventor and businessman. He developed many devices in fields such as electric power generation, mass communication, sound recording, and motion pictures. These inventi ...

's 1879 Menlo Park, New Jersey, New Year's Eve demonstration of his incandescent light bulb

An incandescent light bulb, incandescent lamp or incandescent light globe is an electric light with a wire filament heated until it glows. The filament is enclosed in a glass bulb with a vacuum or inert gas to protect the filament from oxi ...

, Villard requested that Edison install one of his lighting systems onboard Oregon Railroad and Navigation's new steamship, the ''Columbia''. Although hesitant at first, Edison eventually agreed to Villard's request. After being mostly completed at the John Roach & Sons

John Roach & Sons was a major 19th-century American shipbuilding and manufacturing firm founded in 1864 by Irish-American immigrant John Roach. Between 1871 and 1885, the company was the largest shipbuilding firm in the United States, building ...

shipyard in Chester, Pennsylvania

Chester is a city in Delaware County, Pennsylvania, United States. Located within the Philadelphia Metropolitan Area, it is the only city in Delaware County and had a population of 32,605 as of the 2020 census.

Incorporated in 1682, Chester i ...

, the ''Columbia'' was sent to New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

, where Edison and his personnel installed its lighting system. This made ''Columbia'' the first commercial application of Edison's light bulb. ''Columbia'' would later sink on 20 July 1907 following a collision with the steam schooner ''San Pedro'' off Shelter Cove, California

Shelter Cove is a census-designated place in Humboldt County, California. It lies at an elevation of 138 feet (42 m). Shelter Cove is on California's Lost Coast where the King Range meets the Pacific Ocean. A nine-hole golf course surrounds t ...

, killing 88 people.

With the aid of the Oregon and Transcontinental Company, his railroad line to the Pacific Ocean was completed, and it was opened to traffic with festivities in September 1883. The project had cost more than expected, and some months later these companies experienced a financial collapse. Villard's financial embarrassment caused the collapse of the stock exchange firm of Decker, Howell, & Co., and Villard's attorney, William Nelson Cromwell, used $1,000,000 to promptly settle with creditors. On 4 January 1884, Villard resigned the presidency of the Northern Pacific. After spending the intervening time in Europe, he returned to New York City in 1886, and purchased for German capitalists large amounts of the securities of the transportation system that he was instrumental in creating, becoming again director of the Northern Pacific, and on 21 June 1888, again president of the Oregon and Transcontinental Company.

More acquisitions and mergers

In 1881, he acquired the '' New York Evening Post'' and ''The Nation

''The Nation'' is an American liberal biweekly magazine that covers political and cultural news, opinion, and analysis. It was founded on July 6, 1865, as a successor to William Lloyd Garrison's '' The Liberator'', an abolitionist newspaper t ...

''. These publications were then edited by his friend Horace White in conjunction with Edwin L. Godkin and Carl Schurz

Carl Schurz (; March 2, 1829 – May 14, 1906) was a German revolutionary and an American statesman, journalist, and reformer. He immigrated to the United States after the German revolutions of 1848–1849 and became a prominent member of the new ...

. This marked White's re-entry into journalism. He also helped manage Villard's railroad and steamship interests 1876-1891. They had met as newspaper reporters during the Civil War.

Villard had also had a hand in the large electric power business founded by

Villard had also had a hand in the large electric power business founded by Thomas Edison

Thomas Alva Edison (February 11, 1847October 18, 1931) was an American inventor and businessman. He developed many devices in fields such as electric power generation, mass communication, sound recording, and motion pictures. These inventi ...

, merging the Edison Electric Light Company, Edison Lamp Company of Newark, New Jersey

Newark ( , ) is the List of municipalities in New Jersey, most populous City (New Jersey), city in the U.S. state of New Jersey and the county seat, seat of Essex County, New Jersey, Essex County and the second largest city within the New Yo ...

, and the Edison Machine Works at Schenectady, New York

Schenectady () is a city in Schenectady County, New York, United States, of which it is the county seat. As of the 2020 census, the city's population of 67,047 made it the state's ninth-largest city by population. The city is in eastern New Yo ...

, to form the Edison General Electric Company. Villard was the president of this concern until 1892 when he was forced out after financier J. P. Morgan engineered a merger with the Thomson-Houston Electric Company that put that company's board in control of the new enterprise, renamed General Electric

General Electric Company (GE) is an American multinational conglomerate founded in 1892, and incorporated in New York state and headquartered in Boston. The company operated in sectors including healthcare, aviation, power, renewable ene ...

.

Philanthropy

In 1883, he paid the debt of theUniversity of Oregon

The University of Oregon (UO, U of O or Oregon) is a public research university in Eugene, Oregon. Founded in 1876, the institution is well known for its strong ties to the sports apparel and marketing firm Nike, Inc

Nike, Inc. ( or ) is a ...

, and gave the institution $50,000. As the University of Oregon

The University of Oregon (UO, U of O or Oregon) is a public research university in Eugene, Oregon. Founded in 1876, the institution is well known for its strong ties to the sports apparel and marketing firm Nike, Inc

Nike, Inc. ( or ) is a ...

's first benefactor, he had Villard Hall, the second building on campus, named after him.

He liberally aided the University of Washington Territory. He also aided Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of highe ...

, Columbia University

Columbia University (also known as Columbia, and officially as Columbia University in the City of New York) is a private research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Church in Manhatt ...

, the Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Metropolitan Museum of Art of New York City, colloquially "the Met", is the largest art museum in the Americas. Its permanent collection contains over two million works, divided among 17 curatorial departments. The main building at 1000 ...

and the American Museum of Natural History

The American Museum of Natural History (abbreviated as AMNH) is a natural history museum on the Upper West Side of Manhattan in New York City. In Theodore Roosevelt Park, across the street from Central Park, the museum complex comprises 26 int ...

.

In Speyer he was a main benefactor for the construction of the Memorial Church and a new hospital. There he is still known as Heinrich Hilgard, and a street is named after him (Hilgardstrasse). He has been honoured with the freedom of the city

The Freedom of the City (or Borough in some parts of the UK) is an honour bestowed by a municipality upon a valued member of the community, or upon a visiting celebrity or dignitary. Arising from the medieval practice of granting respected ...

, and there is a bust of him on the compound of the Speyer Diakonissen Hospital.

In Zweibrücken he built an orphanage in 1891. He has also financed a school for nurses. He devoted large sums to the Industrial Art School of Rhenish Bavaria

The Palatinate (german: Pfalz; Palatine German: ''Palz'') is a region of Germany. In the Middle Ages it was known as the Rhenish Palatinate (''Rheinpfalz'') and Lower Palatinate (''Unterpfalz''), which strictly speaking designated only the w ...

, and to the foundation of fifteen scholarships for the youth of that province.

He supported Bandelier in his research on South American history and archaeology.

Personal life

women's suffrage

Women's suffrage is the right of women to vote in elections. Beginning in the start of the 18th century, some people sought to change voting laws to allow women to vote. Liberal political parties would go on to grant women the right to vot ...

advocate Helen Frances Garrison (1844–1928), the only daughter of abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison

William Lloyd Garrison (December , 1805 – May 24, 1879) was a prominent American Christian, abolitionist, journalist, suffragist, and social reformer. He is best known for his widely read antislavery newspaper '' The Liberator'', which he fo ...

. Together, they were the parents of:

* Helen Elise Villard (1868–1917), who married Dr. James William Bell, an English physician, in 1897, and was a semi-invalid most of her life due to a childhood fall down an elevator shaft at the Westmoreland House.

* Harold Garrison Villard (1869–1952), who married Mariquita Serrano (1864–1936), sister of Vincent Serrano

Vincent Serrano (February 17, 1866 – January 11, 1935) was an American actor in plays and silent films.

Biography

Serrano's best-known role was as Lieutenant Denton in the Augustus Thomas play '' Arizona'', which had its New York opening in S ...

, in 1897.

* Oswald Garrison Villard

Oswald Garrison Villard (March 13, 1872 – October 1, 1949) was an American journalist and editor of the ''New York Evening Post.'' He was a civil rights activist, and along with his mother, Fanny Villard, a founding member of the NAACP. ...

(1872–1949), who married Julia Breckenridge Sanford (1876–1962)

* Henry Hilgard Villard (1883–1890), who died young.

Henry Villard died of a stroke at his country home, Thorwood Park, in Dobbs Ferry, New York

Dobbs Ferry is a village in Westchester County, New York, United States. The population was 10,875 according to the 2010 United States Census. In 2019, its population rose to an estimated 11,027. The village of Dobbs Ferry is located in, and is a ...

. He was interred in the Sleepy Hollow Cemetery

Sleepy Hollow Cemetery in Sleepy Hollow, New York, is the final resting place of numerous famous figures, including Washington Irving, whose 1820 short story " The Legend of Sleepy Hollow" is set in the adjacent burying ground at the Old Dutch ...

in Sleepy Hollow, New York

Sleepy Hollow is a village in the town of Mount Pleasant, New York, Mount Pleasant, in Westchester County, New York, United States. The village is located on the east bank of the Hudson River, about north of New York City, and is served by the ...

. His autobiography was published posthumously, in 1904. The monument

A monument is a type of structure that was explicitly created to commemorate a person or event, or which has become relevant to a social group as a part of their remembrance of historic times or cultural heritage, due to its artistic, hist ...

at his grave site was executed by Karl Bitter.''Karl Bitter: Architectural Sculptor 1867-1915'', University of Wisconsin Press, Madison, 1967 pp. 94-96.

After his death, his daughter brought a suit against the executors and trustees of his will. She claimed that Villard was of unsound mind when he made the will and was the result of fraudulent influence exercised over him by his wife and his two sons. In the will, she was only left $25,000 due to the fact the she married against her father's wishes. She contended that there was no mention of the $200,000 worth of securities she said her father claimed to have left her. His daughter lost her suit as the Judge ruled that her delay had forfeited the right to attack the will.

Descendants

Through his son Harold, he was the grandfather of Henry Serrano Villard (1900–1996), theforeign service officer

A Foreign Service Officer (FSO) is a commissioned member of the United States Foreign Service. Foreign Service Officers formulate and implement the foreign policy of the United States. FSOs spend most of their careers overseas as members of U ...

and ambassador

An ambassador is an official envoy, especially a high-ranking diplomat who represents a state and is usually accredited to another sovereign state or to an international organization as the resident representative of their own government or s ...

, and Vincent Serrano Villard, and Mariquita Villard Platov.

Through his son Oswald, he was the grandfather of Dorothea Marshall Villard Hammond (1907–1994), a member of the American University in Cairo

The American University in Cairo (AUC; ar, الجامعة الأمريكية بالقاهرة, Al-Jāmi‘a al-’Amrīkiyya bi-l-Qāhira) is a private research university in Cairo, Egypt. The university offers American-style learning progra ...

, Henry Hilgard Villard (1911–1983), the head of the economics department at the City College of New York

The City College of the City University of New York (also known as the City College of New York, or simply City College or CCNY) is a public university within the City University of New York (CUNY) system in New York City. Founded in 1847, Cit ...

and the first male president of Planned Parenthood

The Planned Parenthood Federation of America, Inc. (PPFA), or simply Planned Parenthood, is a nonprofit organization that provides reproductive health care in the United States and globally. It is a tax-exempt corporation under Internal Reve ...

of New York City, and Oswald Garrison Villard, Jr. (1916–2004), a professor of electrical engineering at Stanford University

Stanford University, officially Leland Stanford Junior University, is a private research university in Stanford, California. The campus occupies , among the largest in the United States, and enrolls over 17,000 students. Stanford is conside ...

.

Residences

In the late 1870s, Villard bought an old country estate known as "Thorwood Park" inDobbs Ferry, New York

Dobbs Ferry is a village in Westchester County, New York, United States. The population was 10,875 according to the 2010 United States Census. In 2019, its population rose to an estimated 11,027. The village of Dobbs Ferry is located in, and is a ...

. The home, which featured sweeping views of the Hudson River

The Hudson River is a river that flows from north to south primarily through eastern New York. It originates in the Adirondack Mountains of Upstate New York and flows southward through the Hudson Valley to the New York Harbor between Ne ...

, was redecorated by Charles Follen McKim of McKim, Mead and White in the early 1880s.

In 1884, Villard hired Joseph M. Wells of the architecture firm McKim, Mead and White to design and construct the Villard Houses, which appear as one building but in fact is six separate residences. The houses are located at 455 Madison Avenue

Madison Avenue is a north-south avenue in the borough of Manhattan in New York City, United States, that carries northbound one-way traffic. It runs from Madison Square (at 23rd Street) to meet the southbound Harlem River Drive at 142nd Str ...

between 50th and 51st Street in Manhattan

Manhattan (), known regionally as the City, is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the five boroughs of New York City. The borough is also coextensive with New York County, one of the original counties of the U.S. state ...

with four of the homes opening onto the courtyard facing Madison, while the other two had entrances on 51st Street. The homes are in the Romanesque Revival style with neo-Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ide ...

touches and feature elaborate interiors by prominent artists including John La Farge, Augustus Saint-Gaudens

Augustus Saint-Gaudens (; March 1, 1848 – August 3, 1907) was an American sculptor of the Beaux-Arts generation who embodied the ideals of the American Renaissance. From a French-Irish family, Saint-Gaudens was raised in New York City, he tra ...

, and Maitland Armstrong

David Maitland Armstrong (April 15, 1836Armstrong, Maitland. Margaret Armstrong (Ed.) (1920''Day before Yesterday: Reminiscences of a Varied Life''.New York: Scribner, p. 157.May 26, 1918)

was ''Charge d'Affaires'' to the Papal States (1869),

Am ...

.Lockhart, Mary (2014) ''Treasures of New York: Stanford White'' (TV) WLIW. Broadcast accessed:2014-01-05

After Villard's bankruptcy, the Villard House was purchased by Elisabeth Mills Reid (1857–1931), wife of Whitelaw Reid, a diplomat and the editor of the ''New York Tribune'', and the daughter of Darius Ogden Mills and the sister of Ogden Mills, bankers and financiers.

See also

* Elizabeth CaruthersReferences

;Notes ;Sources * * * ''Memoirs of Henry Villard'' (2 vols., Boston, 1904) ** Volume I atWikisource

Wikisource is an online digital library of free-content textual sources on a wiki, operated by the Wikimedia Foundation. Wikisource is the name of the project as a whole and the name for each instance of that project (each instance usually re ...

** Volume II at Wikisource

Wikisource is an online digital library of free-content textual sources on a wiki, operated by the Wikimedia Foundation. Wikisource is the name of the project as a whole and the name for each instance of that project (each instance usually re ...

* ''The Early History of Transportation in Oregon'' Edited by Oswald Garrison Villard (University of Oregon Press, 1944) Reviewed here

'

Further reading

* Buss, Dietrich G. ''Henry Villard: a study of transatlantic investments and interests, 1870-1895'' (Arno Press, 1978). * Cochran, Thomas C. (1949) "The Legend of the Robber Barons." ''Explorations in Economic History'' 1#5 (1949online

deals largely with Villard. * *Kobrak, Christopher

"A Reputation for Cross-Cultural Business: Henry Villard and German Investment in the United States ."

In ''Immigrant Entrepreneurship: German-American Business Biographies, 1720 to the Present'', vol. 2, edited by William J. Hausman. German Historical Institute. Last modified September 30, 2015. * *

External links

a more detailed biography

Henry Villard Business Papers at Baker Library Historical Collections, Harvard Business School

{{DEFAULTSORT:Villard, Henry 1835 births 1900 deaths 19th-century American railroad executives 19th-century American newspaper publishers (people) Bavarian emigrants to the United States American financiers History of transportation in Oregon New York Post people Northern Pacific Railway people People from Speyer People from the Palatinate (region) People from Belleville, Illinois Writers from Peoria, Illinois Businesspeople from Chicago Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich alumni University of Würzburg alumni Philanthropists from New York (state) American war correspondents American people of German descent Burials at Sleepy Hollow Cemetery New York (state) Republicans People from Dobbs Ferry, New York 19th-century American journalists Writers from Chicago The Nation (U.S. magazine) people American male journalists 19th-century American male writers Journalists from Illinois Philanthropists from Illinois 19th-century American philanthropists