Henry M. Mathews on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

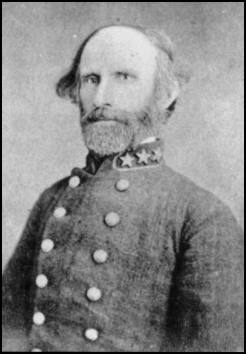

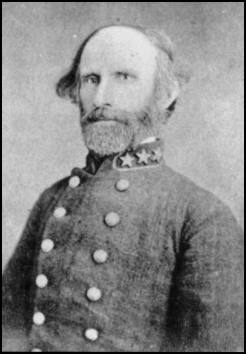

Henry Mason Mathews (March 29, 1834April 28, 1884) was an American military officer, lawyer, and politician in the

Mathews chose to follow his home state of Virginia on its joining of the

Mathews chose to follow his home state of Virginia on its joining of the

At the conclusion of his term as attorney general, Mathews defeated

At the conclusion of his term as attorney general, Mathews defeated

From 1863, when West Virginia was formed, through 1875, the capital of West Virginia had alternated between Wheeling and Charleston, with its location largely dependent on political party control of the state, with Republicans favoring Wheeling and Democrats favoring Charleston. Early in Mathews' administration, a vote was held to determine a permanent location for the capital, which was currently located in Wheeling. Three options of Charleston, Clarksburg, and Martinsurg were presented (Wheeling was not listed as a voting option). During the campaigning, state Democrats employed a young

From 1863, when West Virginia was formed, through 1875, the capital of West Virginia had alternated between Wheeling and Charleston, with its location largely dependent on political party control of the state, with Republicans favoring Wheeling and Democrats favoring Charleston. Early in Mathews' administration, a vote was held to determine a permanent location for the capital, which was currently located in Wheeling. Three options of Charleston, Clarksburg, and Martinsurg were presented (Wheeling was not listed as a voting option). During the campaigning, state Democrats employed a young

Mathews retired from politics in 1881, at which point he returned to his law practice. He additionally served as president of the White Sulfur Springs Company (now

Mathews retired from politics in 1881, at which point he returned to his law practice. He additionally served as president of the White Sulfur Springs Company (now

Biography of Henry M. Mathews

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Mathews, Henry M. 1830s births 1884 deaths Military personnel from West Virginia Beta Theta Pi Burials in West Virginia Confederate States Army officers Educators from West Virginia Democratic Party governors of West Virginia Mathews family of Virginia and West Virginia People from Lewisburg, West Virginia People of Virginia in the American Civil War People of West Virginia in the American Civil War University of Virginia alumni University of Virginia School of Law alumni Washington and Lee University School of Law alumni Virginia lawyers West Virginia Attorneys General West Virginia lawyers People from Greenbrier County, West Virginia 19th-century American lawyers 19th-century American politicians The Greenbrier people Bourbon Democrats

U.S. State

In the United States, a state is a constituent political entity, of which there are 50. Bound together in a political union, each state holds governmental jurisdiction over a separate and defined geographic territory where it shares its sover ...

of West Virginia

West Virginia is a state in the Appalachian, Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States.The Census Bureau and the Association of American Geographers classify West Virginia as part of the Southern United States while the Bur ...

. Mathews served as 7th Attorney General of West Virginia

Attorney may refer to:

* Lawyer

** Attorney at law, in some jurisdictions

* Attorney, one who has power of attorney

* ''The Attorney'', a 2013 South Korean film

See also

* Attorney general, the principal legal officer of (or advisor to) a gove ...

(1873–1877) and 5th Governor of West Virginia

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political r ...

(1877–1881), being the first former Confederate

Confederacy or confederate may refer to:

States or communities

* Confederate state or confederation, a union of sovereign groups or communities

* Confederate States of America, a confederation of secessionist American states that existed between 1 ...

elected to the governorship in the state. Born into a Virginia political family

A political family (also referred to as political dynasty) is a family in which multiple members are involved in politics — particularly electoral politics. Members may be related by blood or marriage; often several generations or multiple sibli ...

, Mathews attended the University of Virginia

The University of Virginia (UVA) is a Public university#United States, public research university in Charlottesville, Virginia. Founded in 1819 by Thomas Jefferson, the university is ranked among the top academic institutions in the United S ...

and afterward practiced law before the outbreak of the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

. When Virginia seceded from the United States, in 1861, he volunteered for the Confederate States Army

The Confederate States Army, also called the Confederate Army or the Southern Army, was the military land force of the Confederate States of America (commonly referred to as the Confederacy) during the American Civil War (1861–1865), fighting ...

and served in the western theater as a major of artillery. Following the war, Mathews was elected to the West Virginia Senate

The West Virginia Senate is the upper house of the West Virginia Legislature.

There are seventeen senatorial districts. Each district has two senators who serve staggered four-year terms. Although the Democratic Party held a supermajority in t ...

, but was denied the seat due to state restrictions on former Confederates. Mathews participated in the 1872 state constitutional convention that overturned these restrictions, and in that same year was elected attorney general of West Virginia. After one term, he was elected governor of West Virginia.

Mathews was identified as a Redeemer, the southern wing of the conservative, pro-business Bourbon Bourbon may refer to:

Food and drink

* Bourbon whiskey, an American whiskey made using a corn-based mash

* Bourbon barrel aged beer, a type of beer aged in bourbon barrels

* Bourbon biscuit, a chocolate sandwich biscuit

* A beer produced by Bras ...

faction of the Democratic Party Democratic Party most often refers to:

*Democratic Party (United States)

Democratic Party and similar terms may also refer to:

Active parties Africa

*Botswana Democratic Party

*Democratic Party of Equatorial Guinea

*Gabonese Democratic Party

*Demo ...

that sought to oust the Radical Republican

The Radical Republicans (later also known as " Stalwarts") were a faction within the Republican Party, originating from the party's founding in 1854, some 6 years before the Civil War, until the Compromise of 1877, which effectively ended Reco ...

s who had come to power across the postwar South. However, Mathews took the uncommon practice of appointing members from both parties to important positions, causing his administration to be characterized as "an era of good feelings." He sought to attract industry to the state, and courted immigration. His administration faced challenges related to the Long Depression

The Long Depression was a worldwide price and economic recession, beginning in 1873 and running either through March 1879, or 1896, depending on the metrics used. It was most severe in Europe and the United States, which had been experiencing st ...

, most notably the outbreak of the Great Railroad Strike of 1877

The Great Railroad Strike of 1877, sometimes referred to as the Great Upheaval, began on July 14 in Martinsburg, West Virginia, after the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O) cut wages for the third time in a year. This strike finally ended 52 day ...

in Martinsburg, West Virginia

Martinsburg is a city in and the seat of Berkeley County, West Virginia, in the tip of the state's Eastern Panhandle region in the lower Shenandoah Valley. Its population was 18,835 in the 2021 census estimate, making it the largest city in the E ...

, as a labor protest to wage cuts. After several failed attempts to quell the strike with state militia, Mathews called on President Rutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford Birchard Hayes (; October 4, 1822 – January 17, 1893) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 19th president of the United States from 1877 to 1881, after serving in the U.S. House of Representatives and as governor ...

for federal assistance, which brought national attention to the strike that spread to other states in what would be the first national labor strike in United States history. Mathews' handling of the strike, and his portrayal of the strikers, was criticized by labor activists at the time, and his calling for Federal assistance was questioned, though the involvement of the federal government in breaking up the strike has come to be seen as inevitable by modern historians. In later life, Mathews served as president of the White Sulfur Springs Company (now the Greenbrier Resort

The Greenbrier is a luxury resort located in the Allegheny Mountains near White Sulphur Springs in Greenbrier County, West Virginia, in the United States.

Since 1778, visitors have traveled to this part of the state to "take the waters" of the ...

).

Early life

Henry Mason Mathews was born on March 29, 1834 in Frankford, Virginia, U.S., (located in modern-dayWest Virginia

West Virginia is a state in the Appalachian, Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States.The Census Bureau and the Association of American Geographers classify West Virginia as part of the Southern United States while the Bur ...

) to Eliza Shore (née Reynolds) and Mason Mathews

Mason Mathews (December 15, 1803 – September 16, 1878) was an American merchant and politician in the U.S. State of Virginia (present-day West Virginia). He served in the Virginia House of Delegates, representing Greenbrier County, West Virgin ...

.White

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no hue). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully reflect and scatter all the visible wavelengths of light. White on ...

, p. 431 Addkinson-Simmons His family had been politically prominent in western Virginia for several generations, and his father was a merchant and politician who served in the Virginia House of Delegates

The Virginia House of Delegates is one of the two parts of the Virginia General Assembly, the other being the Senate of Virginia. It has 100 members elected for terms of two years; unlike most states, these elections take place during odd-numbe ...

. His ancestry was Scotch-Irish and/or Welsh

Welsh may refer to:

Related to Wales

* Welsh, referring or related to Wales

* Welsh language, a Brittonic Celtic language spoken in Wales

* Welsh people

People

* Welsh (surname)

* Sometimes used as a synonym for the ancient Britons (Celtic peop ...

.

Mathews received a primary education at the local Lewisburg Academy, and afterward attended the University of Virginia

The University of Virginia (UVA) is a Public university#United States, public research university in Charlottesville, Virginia. Founded in 1819 by Thomas Jefferson, the university is ranked among the top academic institutions in the United S ...

, earning a Bachelor of Arts

Bachelor of arts (BA or AB; from the Latin ', ', or ') is a bachelor's degree awarded for an undergraduate program in the arts, or, in some cases, other disciplines. A Bachelor of Arts degree course is generally completed in three or four years ...

in 1855 and a Master of Arts

A Master of Arts ( la, Magister Artium or ''Artium Magister''; abbreviated MA, M.A., AM, or A.M.) is the holder of a master's degree awarded by universities in many countries. The degree is usually contrasted with that of Master of Science. Tho ...

in 1856. He was a member of the Beta Theta Pi

Beta Theta Pi (), commonly known as Beta, is a North American social fraternity that was founded in 1839 at Miami University in Oxford, Ohio. One of North America's oldest fraternities, as of 2022 it consists of 144 active chapters in the Unite ...

fraternity. In his Masters Thesis

Master or masters may refer to:

Ranks or titles

* Ascended master, a term used in the Theosophical religious tradition to refer to spiritually enlightened beings who in past incarnations were ordinary humans

* Grandmaster (chess), National Maste ...

, "Poetry in America," Mathews advocated the study of fine arts

In European academic traditions, fine art is developed primarily for aesthetics or creative expression, distinguishing it from decorative art or applied art, which also has to serve some practical function, such as pottery or most metalwork ...

and reconciled their apparent decline in the face of industrialism

Industrialisation ( alternatively spelled industrialization) is the period of social and economic change that transforms a human group from an agrarian society into an industrial society. This involves an extensive re-organisation of an econom ...

with the potential for societal advancement such industry implied. On the completion of his graduate degree, Mathews entered Lexington Law School and studied under John W. Brockenbrough

John White Brockenbrough (December 23, 1806 – February 20, 1877) was a Virginia attorney, law professor, U.S. District Judge of the United States District Court for the Western District of Virginia, and Confederate States congressman and distr ...

, graduating in 1857 with a degree of Bachelor of Laws

Bachelor of Laws ( la, Legum Baccalaureus; LL.B.) is an undergraduate law degree in the United Kingdom and most common law jurisdictions. Bachelor of Laws is also the name of the law degree awarded by universities in the People's Republic of Chi ...

. He was admitted to the bar and began practicing in the fall of that year. Soon afterward he accepted the professorship of Language and Literature

''Language and Literature'' is a peer-reviewed academic journal that publishes articles in the field of stylistics. The journal's editor is Dan McIntyre (University of Huddersfield). It has been published since 1992, first by Longman and then by ...

at Alleghany College, Blue Sulphur Springs, retaining the privilege to practicing law in the courts. In November 1857, at age 22, Mathews married Lucy Fry Mathews, daughter of Judge Joseph L. Fry. They would go on to have 5 children: Lucile "Josephine", Mason, William Gordon, Henry Edgar, and Laura Herne.

Mathews became active in local politics in the years proceeding the outbreak of the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

, organizing for Democratic presidential candidate John C. Breckinridge

John Cabell Breckinridge (January 16, 1821 – May 17, 1875) was an American lawyer, politician, and soldier. He represented Kentucky in both houses of Congress and became the 14th and youngest-ever vice president of the United States. Serving ...

during the 1860 presidential campaign.Rice

Rice is the seed of the grass species ''Oryza sativa'' (Asian rice) or less commonly ''Oryza glaberrima

''Oryza glaberrima'', commonly known as African rice, is one of the two domesticated rice species. It was first domesticated and grown i ...

, p. 251 Breckinridge lost the national vote to Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

, who did not receive a single vote in Mathews' home county of Greenbrier. Nevertheless, Greenbrier was generally opposed to secession in the United States

In the context of the United States, secession primarily refers to the voluntary withdrawal of one or more states from the Union that constitutes the United States; but may loosely refer to leaving a state or territory to form a separate ter ...

and voted against it in the Virginia Secession Convention of 1861

The Virginia Secession Convention of 1861 was called in Richmond to determine whether Virginia would secede from the United States, to govern the state during a state of emergency, and to write a new Constitution for Virginia, which was subsequent ...

.

Military service

Mathews chose to follow his home state of Virginia on its joining of the

Mathews chose to follow his home state of Virginia on its joining of the Confederate States of America

The Confederate States of America (CSA), commonly referred to as the Confederate States or the Confederacy was an unrecognized breakaway republic in the Southern United States that existed from February 8, 1861, to May 9, 1865. The Confeder ...

. Along with his two brothers, he volunteered for the Confederate States Army

The Confederate States Army, also called the Confederate Army or the Southern Army, was the military land force of the Confederate States of America (commonly referred to as the Confederacy) during the American Civil War (1861–1865), fighting ...

(CSA) in 1861 at the rank of private

Private or privates may refer to:

Music

* " In Private", by Dusty Springfield from the 1990 album ''Reputation''

* Private (band), a Denmark-based band

* "Private" (Ryōko Hirosue song), from the 1999 album ''Private'', written and also recorde ...

. Early in the war he was assigned to recruiting and enlisting duties Virginia. In 1863, he was moved to the staff of his uncle, Brigadier General Alexander W. Reynolds, in Major General Carter L. Stevenson

Carter Littlepage Stevenson, Jr. (September 21, 1817 – August 15, 1888) was a career military officer, serving in the United States Army in several antebellum wars and then in the Confederate States Army as a general in the Western Theater ...

's division of Lieutenant General John C. Pemberton

John Clifford Pemberton (August 10, 1814 – July 13, 1881) was a career United States Army officer who fought in the Seminole Wars and with distinction during the Mexican–American War. He resigned his commission to serve as a Confederate Stat ...

's army. He was promoted to major of artillery and served the Vicksburg Campaign

The Vicksburg campaign was a series of maneuvers and battles in the Western Theater of the American Civil War directed against Vicksburg, Mississippi, a fortress city that dominated the last Confederate-controlled section of the Mississippi Riv ...

. Rickard, p. i When general Stevenson's division advanced to Baker's Creek for the Battle of Champion Hill

The Battle of Champion Hill of May 16, 1863, was the pivotal battle in the Vicksburg Campaign of the American Civil War (1861–1865). Union Army commander Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant and the Army of the Tennessee pursued the retreating Confe ...

, Mathews was left in Vicksburg as the chief of his department.

Throughout the war, Mathews frequently ran into difficulties with the Confederate military. He contemplated leaving the army in 1863, and also in that year applied for a transfer from his uncle's brigade to Richmond, Virginia

(Thus do we reach the stars)

, image_map =

, mapsize = 250 px

, map_caption = Location within Virginia

, pushpin_map = Virginia#USA

, pushpin_label = Richmond

, pushpin_m ...

, though the results of this request are unclear. In the fall of 1864, he was arrested by orders of General Robert E. Lee due to a misunderstanding of a courier's message regarding ordnance movement. Lee dismissed the charges on receipt of Mathews' explanation. Rickard, p. i By the end of 1864, Mathews had finally lost all enthusiasm for the war and was relieved from active duty at his request.Combs

Combs may refer to:

Places

France

* Combs-la-Ville, a commune in the southeastern suburbs of Paris

United Kingdom

*Combs, Derbyshire, England

*Combs, Suffolk, England

United States

*Combs, Arkansas, a community

*Combs, Kentucky, a com ...

, p. 39

Political career

Political rise

While at war Mathews' reputation as a leader had spread at home. In a post-war state dominated by the Republican party, Mathews, a Democrat, was elected to theWest Virginia Senate

The West Virginia Senate is the upper house of the West Virginia Legislature.

There are seventeen senatorial districts. Each district has two senators who serve staggered four-year terms. Although the Democratic Party held a supermajority in t ...

in 1865 but was denied the seat due to the restriction that prohibited former Confederates from holding public office. As in-state Democratic support increased in subsequent years, Republicans amended the West Virginia State Constitution to return state rights to former Confederates in an attempt to appeal to voters. The effort backfired as this enabled the Democratic party to regained control of the legislature.

Mathews was sent as a Democratic delegate to the Constitutional Convention of 1872 to overhaul the 1863 Republican-drafted state constitution. The drafting of this new constitution enabled Mathews' rise in the politics of the state. The following year, 1873, he was elected attorney general

In most common law jurisdictions, the attorney general or attorney-general (sometimes abbreviated AG or Atty.-Gen) is the main legal advisor to the government. The plural is attorneys general.

In some jurisdictions, attorneys general also have exec ...

of the state under Governor John J. Jacobs, succeeding Joseph Sprigg, and served one term in which his popularity within his party rose.

At the conclusion of his term as attorney general, Mathews defeated

At the conclusion of his term as attorney general, Mathews defeated Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

Nathan Goff

Nathan Goff Jr. (February 9, 1843 – April 23, 1920) was a United States representative from West Virginia, a Union Army officer, the 28th United States Secretary of the Navy during President Rutherford B. Hayes administration, a United States ...

by 15,000 votes in the most one-sided race for governor in state history at that time. Thus, on March 4, 1877, Mathews became fifth governor of West Virginia, and the first Confederate veteran to be elected to the state governorship. Mathews' conservative, pro-business platform aligned with the Bourbon Democrat

Bourbon Democrat was a term used in the United States in the later 19th century (1872–1904) to refer to members of the Democratic Party who were ideologically aligned with fiscal conservatism or classical liberalism, especially those who suppo ...

ic movement sweeping the South. Mathews was the first of the Bourbons to ascend to a governorship, though many would follow all over the South in the 1880s.

Governor of West Virginia

In his inaugural address, Mathews emphasized unity and progress in the wake of war, promising:The legitimate results of the war have been accepted in good faith, and political parties are no longer aligned upon the dead issues of the past. We have ceased to look back mournfully, and have said "Let the dead past bury its dead," and with reorganized forces have moved up to the living issues of the present.Mathews' address was well-received across the state. The Republican ''Morgantown Post'' praised the "broad, manly, and liberal address, which possesses, to our mind, an honesty of purpose, and a freedom from disguise, that is truly refreshing." Fast, p. 184 His inaugural celebration, which included "flowers and flags and banners and music, feasting and revelry," had been a more elaborate affair than previous gubernatorial inaugurations in the state, setting a precedent that has continued to the present. On assembling his

cabinet

Cabinet or The Cabinet may refer to:

Furniture

* Cabinetry, a box-shaped piece of furniture with doors and/or drawers

* Display cabinet, a piece of furniture with one or more transparent glass sheets or transparent polycarbonate sheets

* Filing ...

, Mathews sought to reduce post-war political tension. Fast, p. 185 He appointed both Republican and Democratic party members to his cabinet, a move that was uncommon in the post-war political climate.

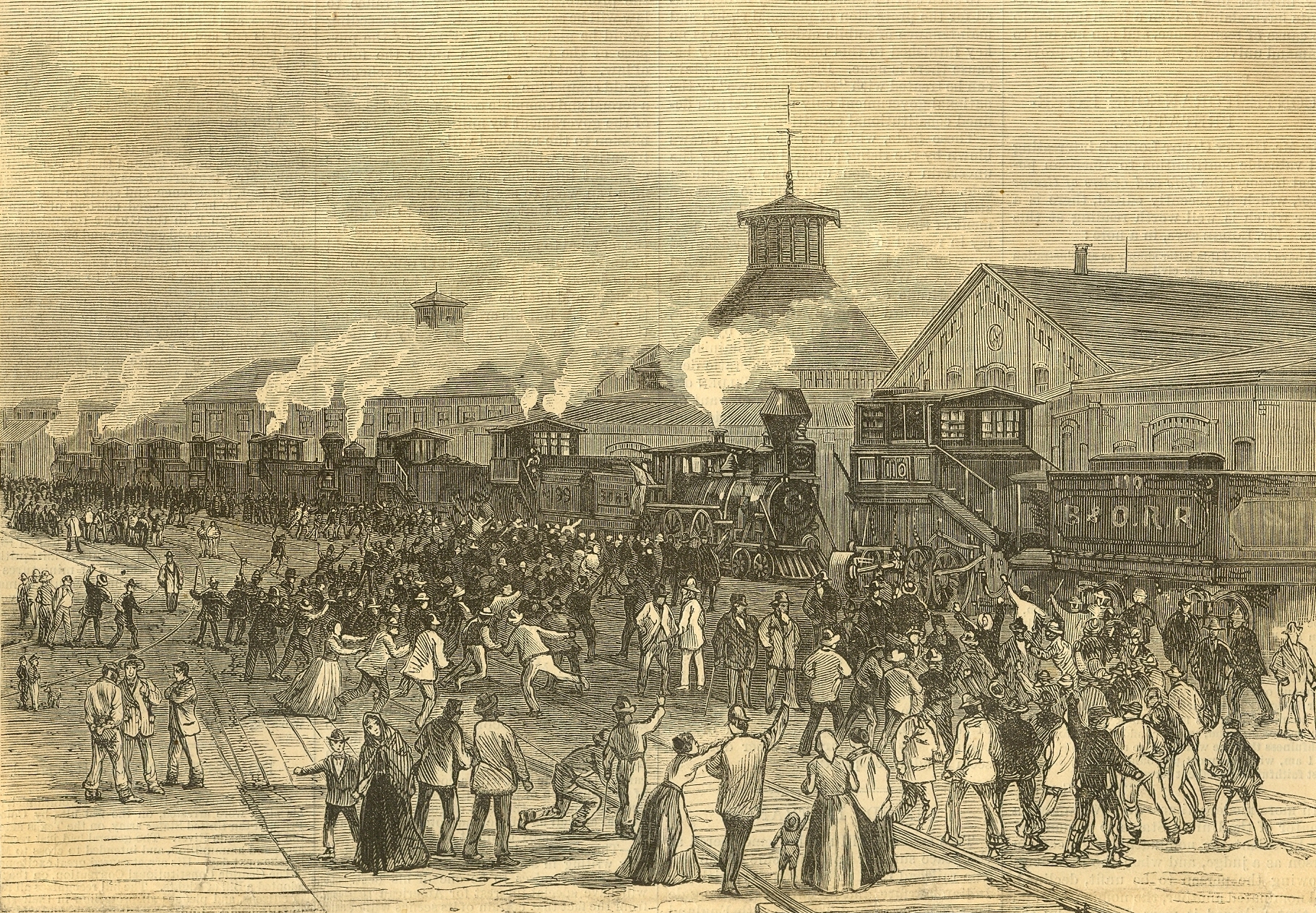

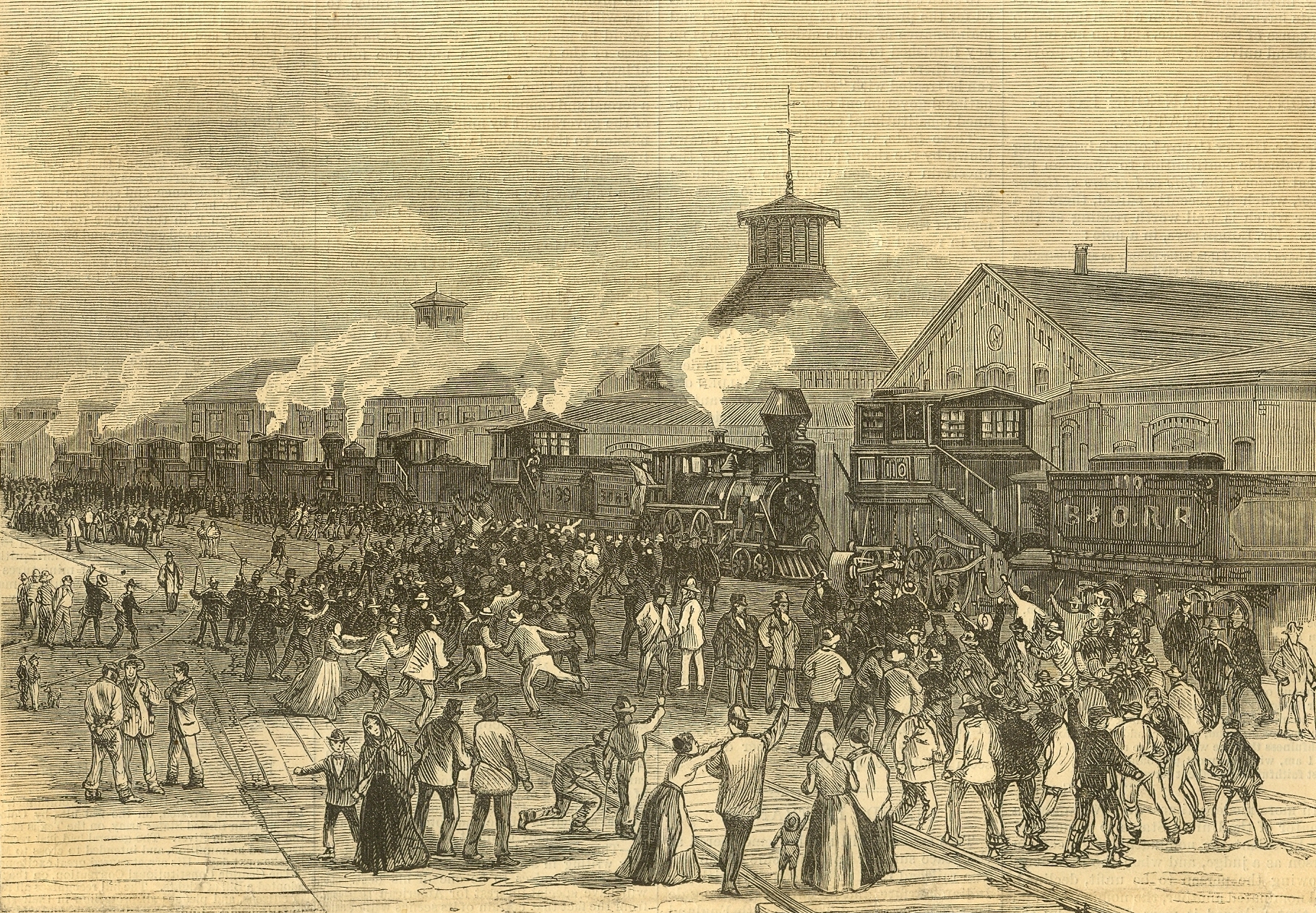

Great Railroad Strike

Awaiting Mathews in office were economic woes associated with thePanic of 1873

The Panic of 1873 was a financial crisis that triggered an economic depression in Europe and North America that lasted from 1873 to 1877 or 1879 in France and in Britain. In Britain, the Panic started two decades of stagnation known as the "Lon ...

and the subsequent Long Depression

The Long Depression was a worldwide price and economic recession, beginning in 1873 and running either through March 1879, or 1896, depending on the metrics used. It was most severe in Europe and the United States, which had been experiencing st ...

. In July 1877, four months into his term, he was alerted that Baltimore and Ohio Railroad

The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad was the first common carrier railroad and the oldest railroad in the United States, with its first section opening in 1830. Merchants from Baltimore, which had benefited to some extent from the construction of ...

(B&O) workers in Martinsburg, West Virginia

Martinsburg is a city in and the seat of Berkeley County, West Virginia, in the tip of the state's Eastern Panhandle region in the lower Shenandoah Valley. Its population was 18,835 in the 2021 census estimate, making it the largest city in the E ...

, had been stopping trains to protest wage cuts. Mathews called out local militia under Colonel Charles J. Faulkner to disperse the protest, but unbeknownst to Mathews, several in the company were rail workers themselves, and many others were sympathetic to the strike. The militia acted indecisively on arrival, and in the confusion a striker named William Vandergriff fired on the militia and was mortally wounded by return fire. Local papers blamed Mathews for the death and deemed Vandergriff a "martyr." The militia officially conveyed to Mathews that they would thereon refuse his orders.

Mathews responded by sending another militia company—this time with no rail workers were among them—to address the growing strike, but he was informed that this company too would not act against the strikers.Bellesiles

''Arming America: The Origins of a National Gun Culture'' is a discredited 2000 book by historian Michael A. Bellesiles about American gun culture, an expansion of a 1996 article he published in the ''Journal of American History''. Bellesiles, t ...

, p.149 Mathews finally complied with the urging of his administration to request Federal troops from newly elected President Rutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford Birchard Hayes (; October 4, 1822 – January 17, 1893) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 19th president of the United States from 1877 to 1881, after serving in the U.S. House of Representatives and as governor ...

. Mathews' decision to call for federal support garnered significant national notice to the strikes. Local newspapers were highly critical of the governor's characterization of the strikes to Hayes as an "insurrection" rather than an act of desperation, with one notable paper recorded a striking worker's perspective that, " ehad might as well die by the bullet as to starve to death by inches." Caplinger Mathews' decision to call for federal assistance has been vindicated by historians, who have come to view federal involvement as inevitable.

Hayes had vowed not to involve the Federal government in domestic matters during his candidacy several months prior, and he sought to solve the matter diplomatically. After failed negotiations with leaders of the railway "insurrection," he reluctantly dispatched Federal troops to Martinsburg. However, by this time the strike, by then referred to as the Great Railroad Strike of 1877

The Great Railroad Strike of 1877, sometimes referred to as the Great Upheaval, began on July 14 in Martinsburg, West Virginia, after the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O) cut wages for the third time in a year. This strike finally ended 52 day ...

, had reverted to peaceful protest in Martinsburg while violence spread to Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware and the Atlantic Ocean to ...

, Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

, Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolita ...

, and Missouri

Missouri is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking List of U.S. states and territories by area, 21st in land area, it is bordered by eight states (tied for the most with Tennessee ...

. The strike gained considerable support in other states across the country.

In 1880, Mathews was again required to dispatch the militia, this time to Hawks Nest, West Virginia

Hawk's Nest, the site of Hawks Nest State Park, is a peak on Gauley Mountain in Ansted, West Virginia, United States, USA. The cliffs at this point rise 585 ft (178 m) above the New River (West Virginia), New River. Located on the James R ...

to stop the state's first major coal strike, as miners from Hawks Nest were being threatened with violence to cease productivity by a rival constituent.

Relocating the capitol

From 1863, when West Virginia was formed, through 1875, the capital of West Virginia had alternated between Wheeling and Charleston, with its location largely dependent on political party control of the state, with Republicans favoring Wheeling and Democrats favoring Charleston. Early in Mathews' administration, a vote was held to determine a permanent location for the capital, which was currently located in Wheeling. Three options of Charleston, Clarksburg, and Martinsurg were presented (Wheeling was not listed as a voting option). During the campaigning, state Democrats employed a young

From 1863, when West Virginia was formed, through 1875, the capital of West Virginia had alternated between Wheeling and Charleston, with its location largely dependent on political party control of the state, with Republicans favoring Wheeling and Democrats favoring Charleston. Early in Mathews' administration, a vote was held to determine a permanent location for the capital, which was currently located in Wheeling. Three options of Charleston, Clarksburg, and Martinsurg were presented (Wheeling was not listed as a voting option). During the campaigning, state Democrats employed a young Booker T. Washington

Booker Taliaferro Washington (April 5, 1856November 14, 1915) was an American educator, author, orator, and adviser to several presidents of the United States. Between 1890 and 1915, Washington was the dominant leader in the African-American c ...

to engage in a speaking tour to consolidate Black opinion in favor of Charleston. Charleston won the vote, and has remained the state capital since.

State debt and treasury

Questions of debt owed by West Virginia to Virginia persisted throughout Mathews' term in office. The question arose quickly when in 1863 West Virginia was created from the northwestern Virginia region. While both states recognized that a debt existed, determining the value of the debt proved difficult. Virginia authorities had determined that West Virginia should assume approximately one-third of the state debt as of January 1, 1861 — the year Virginia was seceded from the United States, determining West Virginia's total to be $953,360.32. Mathews' advisers countered with the figure of $525,000. Another figure given to him by the Virginians was $7,000,000, owed by West Virginia to its eastern counterpart. Unable to determine the accuracy of these reports, and recognizing that the question had taken on political meaning, Mathews pursued policy intended to suspend a resolution until the specifics had become clear. His successor, Jacob B. Jackson, inherited the same problem and further suspended the resolution of the matter. The argument dragged on throughout the 1800s and the debt was not retired until 1939. During Mathews' administration, Attorney General Robert White secured a decision by the United States Supreme Court in favor of levying taxes against the burgeoning railroad industry, which to that point had not paid any taxes to the State of West Virginia. This decision resulted in an influx of thousands of dollars into the State treasury.Race issues

Before the Civil War, western Virginia had a relatively low slave population compared to the eastern part of the state, or the South as a whole (4% in western Virginia as compared to about 30% in the South). Mathews was raised in one such slaveholding western Virginia household. Mathews' precise views on race and slavery are unclear, though he was a member of several local political conventions that issued statements and resolutions opposingracial equality

Racial equality is a situation in which people of all races and ethnicities are treated in an egalitarian/equal manner. Racial equality occurs when institutions give individuals legal, moral, and political rights. In present-day Western society, ...

, both before and after the Civil War. He was also a delegate to the state convention that drafted the 1872 West Virginia Constitution

The Constitution of the State of West Virginia West Virginia State Constitution is the supreme law of the U.S. state of West Virginia. It expresses the rights of the state's citizens and provides the framework for the organization of law and gover ...

which codified policies of segregation in the state. During Mathews' political career he was identified as a Redeemer – the Southern faction of the Bourbon Democrats

Bourbon Democrat was a term used in the United States in the later 19th century (1872–1904) to refer to members of the Democratic Party who were ideologically aligned with fiscal conservatism or classical liberalism, especially those who suppo ...

. Redeemers dominated Southern politics in most areas from the 1870s to 1910 and were generally led by wealthy former planters, businessmen, and professionals who sought to expel the freedmen

A freedman or freedwoman is a formerly enslaved person who has been released from slavery, usually by legal means. Historically, enslaved people were freed by manumission (granted freedom by their captor-owners), abolitionism, emancipation (gra ...

, carpetbagger

In the history of the United States, carpetbagger is a largely historical term used by Southerners to describe opportunistic Northerners who came to the Southern states after the American Civil War, who were perceived to be exploiting the lo ...

s, and scalawag

In United States history, the term scalawag (sometimes spelled scallawag or scallywag) referred to white Southerners who supported Reconstruction policies and efforts after the conclusion of the American Civil War.

As with the term '' carpetb ...

s from Southern government and reestablished white supremacy

White supremacy or white supremacism is the belief that white people are superior to those of other races and thus should dominate them. The belief favors the maintenance and defense of any power and privilege held by white people. White su ...

in the South. However, West Virginia historian Otis K. Rice objects to this characterization of the West Virginia Redeemers:

This fails to do justice to the flexibility of West Virginia Bourbons. The West Virginia Democrats who followed the Republican founders of the state included Governors Mathews, Jackson, Wilson, Fleming, and MacCorkle. These men were ready to adjust to changing political conditions and to the 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments to the federal Constitution, which conferred freedom, citizenship, and the right to vote and hold office upon former slaves.From 1865 to 1957, West Virginia passed eleven

Jim Crow laws

The Jim Crow laws were state and local laws enforcing racial segregation in the Southern United States. Other areas of the United States were affected by formal and informal policies of segregation as well, but many states outside the Sout ...

under Democratic leadership. None of these were passed during Mathews' administration. In 1881, following the ruling of the ''Strauder v. West Virginia

''Strauder v. West Virginia'', 100 U.S. 303 (1880), was a landmark decision of the Supreme Court of the United States about racial discrimination and United States constitutional criminal procedure. ''Strauder'' was the first instance where t ...

'' Supreme Court case, Mathews reversed a 1873 state law that prohibited Black citizens from serving on juries. In his closing address to the West Virginia legislature in January 1881, Mathews urged his fellow statesmen to adopt a progressive attitude towards the divisive issues that precipitated the Civil War:

It is necessary . . . to fully realize that institutions under which some of us were reared and which have left an enduring impress on our character, -- which have influenced not only our habits of living, but also our opinions and habits of thought -- are now of the past and no longer factors of existing social or political problems; that while the fundamental principles of our republican institutions are forever true and sufficient for all time, yet they must be adapted to the changed conditions produced by the result of the civil war, an increasing population and an advancing civilization. West Virginia should be aligned with the most progressive of her sister States, between whose institutions and her own there is no longer any conflict . . .Fast notes that the "liberal-minded" spirit of Mathews' administration received a setback during the campaign of his predecessor, Jacob B. Jackson, under whom " e old sores of war were torn upon and bled afresh." Fast, p. 189–190

Later life

Mathews retired from politics in 1881, at which point he returned to his law practice. He additionally served as president of the White Sulfur Springs Company (now

Mathews retired from politics in 1881, at which point he returned to his law practice. He additionally served as president of the White Sulfur Springs Company (now The Greenbrier

The Greenbrier is a luxury resort located in the Allegheny Mountains near White Sulphur Springs in Greenbrier County, West Virginia, in the United States.

Since 1778, visitors have traveled to this part of the state to "take the waters" of the ...

resort) following its post-war reopening. The resort became a place for many Southerners and Northerners alike to vacation, and the setting for many famous post-war reconciliations, including the White Sulphur Manifesto, which was the only political position issued by Robert E. Lee after the Civil War, that advocated the merging of the two societies. The resort went on to become a center of regional post-war society.

Henry M. Mathews died unexpectedly on April 28, 1884 and is buried in the Old Stone Church cemetery in Lewisburg, West Virginia.

Legacy

As West Virginia governor Mathews established a state immigration bureau to attract new workers to the state, expanded the coal and oil industries, improved transportation, and funded a state geological survey. His administration at large has been characterized as "an era of good feeling," due to his appointing of Republicans to office during his Democratic tenure. Historian Mary L. Rickard, in the ''Calendar of the Henry Mason Mathews Letters and Papers in the State Department of Archives and History'' (1941), offered a critical analysis of his administration: "At this time there was less wealth per capita in West Virginia than in 1865, the result of which had a pronounced effect upon State politics. Those highest up in the social scale held the highest political positions and the entire organization became dangerously corrupt." However, West Virginia historian Richard Fast notes that no committee to investigate any alleged scandal or mismanagement was appointed during Mathews' term. Fellow West Virginia Governor William A. MacCorkle, in ''Recollections of Fifty Years of West Virginia'' (1928), said of him: "He was not a good come-and-take debater, but when he had prepared himself to make an oration on the issues of the day, he was splendid. His oratory was easy, smooth, perfectly balanced, his voice was splendidly modulated, his gestures were perfect, and he could make as fine an impression on a rather cultivated audience as any man in the state." Because Mathews was the first state governor to call on federal troops in response to the Great Railroad Strike of 1877, this action has been recognized as a catalyst that would help to transform the United StatesNational Guard

National Guard is the name used by a wide variety of current and historical uniformed organizations in different countries. The original National Guard was formed during the French Revolution around a cadre of defectors from the French Guards.

Nat ...

.

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * *External links

Biography of Henry M. Mathews

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Mathews, Henry M. 1830s births 1884 deaths Military personnel from West Virginia Beta Theta Pi Burials in West Virginia Confederate States Army officers Educators from West Virginia Democratic Party governors of West Virginia Mathews family of Virginia and West Virginia People from Lewisburg, West Virginia People of Virginia in the American Civil War People of West Virginia in the American Civil War University of Virginia alumni University of Virginia School of Law alumni Washington and Lee University School of Law alumni Virginia lawyers West Virginia Attorneys General West Virginia lawyers People from Greenbrier County, West Virginia 19th-century American lawyers 19th-century American politicians The Greenbrier people Bourbon Democrats