Henri Breuil on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Henri Édouard Prosper Breuil (28 February 1877 – 14 August 1961), often referred to as Abbé Breuil, was a French

Jill Cook, bradshawfoundation.com, accessed 2 August 2010 He assumed a post as lecturer at the

In 1929, when already a recognised authority on North African and European

In 1929, when already a recognised authority on North African and European

Présentation du livre

* Straus, L.G. "L'Abbé Henri Breuil: Archaeologist", '' Bulletin of the History of Archaeology''. Vol. 2, No. 2. (1992), pp. 5–9. * Straus, L.G. "L'Abbé Henri Breuil: Pope of Paleolithic Prehistory", ''Homenaje al Dr. Joaquín González Echegaray''. Madrid: Museo y Centro de Investigación de Altamira, 1994, pp. 189–198.

BibNum

Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

priest

A priest is a religious leader authorized to perform the sacred rituals of a religion, especially as a mediatory agent between humans and one or more deities. They also have the authority or power to administer religious rites; in partic ...

, archaeologist

Archaeology or archeology is the scientific study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of artifacts, architecture, biofacts or ecofacts, sites, and cultural landsca ...

, anthropologist

An anthropologist is a person engaged in the practice of anthropology. Anthropology is the study of aspects of humans within past and present societies. Social anthropology, cultural anthropology and philosophical anthropology study the norms an ...

, ethnologist

Ethnology (from the grc-gre, ἔθνος, meaning 'nation') is an academic field that compares and analyzes the characteristics of different peoples and the relationships between them (compare cultural, social, or sociocultural anthropolog ...

and geologist

A geologist is a scientist who studies the solid, liquid, and gaseous matter that constitutes Earth and other terrestrial planets, as well as the processes that shape them. Geologists usually study geology, earth science, or geophysics, althou ...

. He is noted for his studies of cave art in the Somme __NOTOC__

Somme or The Somme may refer to: Places

*Somme (department), a department of France

*Somme, Queensland, Australia

*Canal de la Somme, a canal in France

*Somme (river), a river in France

Arts, entertainment, and media

* ''Somme'' (book), a ...

and Dordogne

Dordogne ( , or ; ; oc, Dordonha ) is a large rural department in Southwestern France, with its prefecture in Périgueux. Located in the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region roughly half-way between the Loire Valley and the Pyrenees, it is named ...

valleys as well as in Spain, Portugal, Italy, Ireland, China with Teilhard de Chardin

Pierre Teilhard de Chardin ( (); 1 May 1881 – 10 April 1955) was a French Jesuit priest, scientist, paleontologist, theologian, philosopher and teacher. He was Darwinian in outlook and the author of several influential theological and philo ...

, Ethiopia

Ethiopia, , om, Itiyoophiyaa, so, Itoobiya, ti, ኢትዮጵያ, Ítiyop'iya, aa, Itiyoppiya officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country in the Horn of Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the ...

, British Somali Coast Protectorate, and especially Southern Africa.

Life

Breuil was born at Mortain,Manche

Manche (, ) is a coastal French département in Normandy, on the English Channel, which is known as ''La Manche'', literally "the sleeve", in French. It had a population of 495,045 in 2019.France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, and was the son of Albert Breuil, magistrate, and Lucie Morio De L'Isle.

He received his education at the Seminary of St. Sulpice and the Sorbonne

Sorbonne may refer to:

* Sorbonne (building), historic building in Paris, which housed the University of Paris and is now shared among multiple universities.

*the University of Paris (c. 1150 – 1970)

*one of its components or linked institution, ...

and was ordained in 1900, and was also given permission to pursue his research interests. He was a man of deep religious faith and learning. In 1904 Breuil had recognised that a pair of 13,000-year-old carvings of reindeer at the British Museum

The British Museum is a public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is among the largest and most comprehensive in existence. It docum ...

were in fact one composition.The swimming reindeer; a masterpiece of Ice Age artJill Cook, bradshawfoundation.com, accessed 2 August 2010 He assumed a post as lecturer at the

University of Fribourg

The University of Fribourg (french: Université de Fribourg; german: Universität Freiburg) is a public university located in Fribourg, Switzerland.

The roots of the university can be traced back to 1580, when the notable Jesuit Peter Canisi ...

in 1905, and in 1910 became professor of prehistoric ethnology in Paris and at the Collège de France

The Collège de France (), formerly known as the ''Collège Royal'' or as the ''Collège impérial'' founded in 1530 by François I, is a higher education and research establishment ('' grand établissement'') in France. It is located in Paris n ...

from 1925.

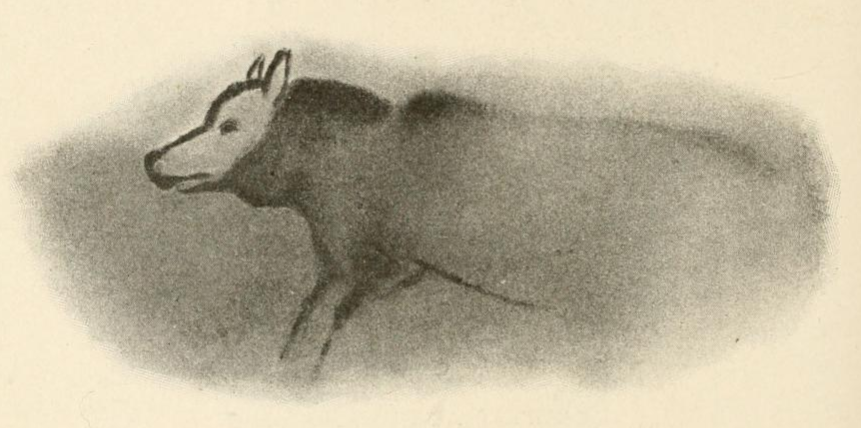

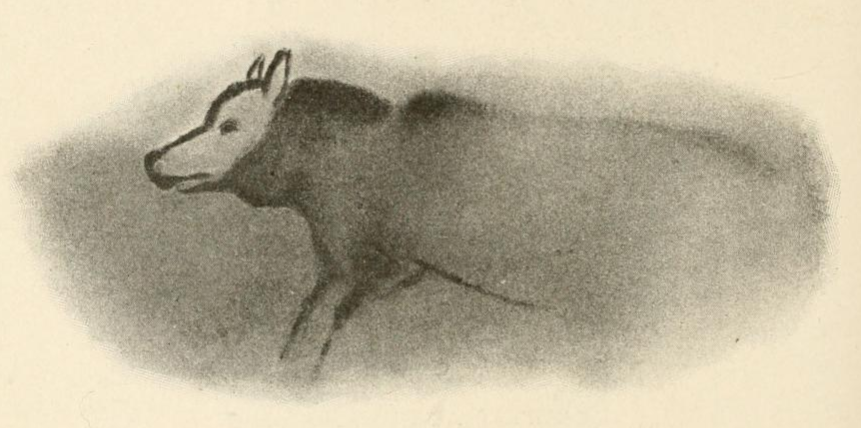

Cave paintings

Breuil was a competent draughtsman, faithfully reproducing the cave paintings he encountered. In 1924 he was awarded theDaniel Giraud Elliot Medal

The Daniel Giraud Elliot Medal is awarded by the U.S. National Academy of Sciences "for meritorious work in zoology or paleontology study published in a three- to five-year period." Named after Daniel Giraud Elliot, it was first awarded in 1917.

L ...

from the National Academy of Sciences

The National Academy of Sciences (NAS) is a United States nonprofit, non-governmental organization. NAS is part of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, along with the National Academy of Engineering (NAE) and the Nat ...

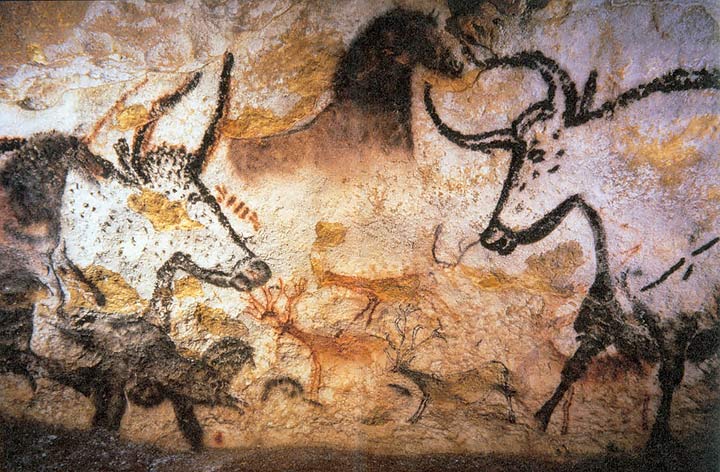

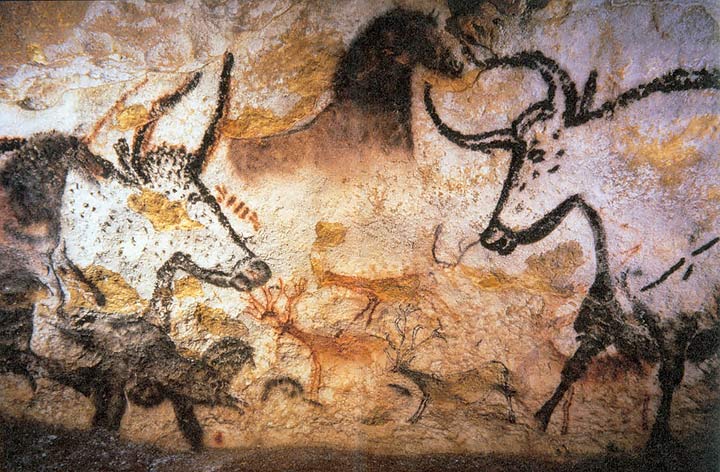

. He published many books and monographs, introducing the caves of Lascaux

Lascaux ( , ; french: Grotte de Lascaux , "Lascaux Cave") is a network of caves near the village of Montignac, in the department of Dordogne in southwestern France. Over 600 parietal wall paintings cover the interior walls and ceilings of t ...

and Altamira

Altamira may refer to:

People

*Altamira (surname)

Places

* Cave of Altamira, a cave in Cantabria, Spain famous for its paintings and carving

*Altamira, Pará, a city in the Brazilian state of Pará

* Altamira, Huila, a town and municipality in ...

to the general public and becoming a member of the Institut de France

The (; ) is a French learned society, grouping five , including the Académie Française. It was established in 1795 at the direction of the National Convention. Located on the Quai de Conti in the 6th arrondissement of Paris, the institut ...

in 1938.

Breuil visited the Peking Man

Peking Man (''Homo erectus pekinensis'') is a subspecies of '' H. erectus'' which inhabited the Zhoukoudian Cave of northern China during the Middle Pleistocene. The first fossil, a tooth, was discovered in 1921, and the Zhoukoudian Cave has s ...

excavations at Zhoukoudian

Zhoukoudian Area () is a town and an area located on the east Fangshan District, Beijing, China. It borders Nanjiao and Fozizhuang Townships to its north, Xiangyang, Chengguan and Yingfeng Subdistricts to its east, Shilou and Hangcunhe Towns t ...

, China in 1931 and confirmed the presence of stone tools at the site.

In 1929, when already a recognised authority on North African and European

In 1929, when already a recognised authority on North African and European Stone Age

The Stone Age was a broad prehistoric period during which stone was widely used to make tools with an edge, a point, or a percussion surface. The period lasted for roughly 3.4 million years, and ended between 4,000 BC and 2,000 BC, with ...

art, he attended a congress on prehistory in South Africa. At the invitation of prime minister Jan Smuts

Field Marshal Jan Christian Smuts, (24 May 1870 11 September 1950) was a South African statesman, military leader and philosopher. In addition to holding various military and cabinet posts, he served as prime minister of the Union of South Af ...

he returned there in 1942 and took up a chair at Witwatersrand University

The University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg (), is a multi-campus South African Public university, public research university situated in the northern areas of central Johannesburg. It is more commonly known as Wits University or Wits ( o ...

from 1944 to 1951. During his South African stay he studied rock art in Lesotho

Lesotho ( ), officially the Kingdom of Lesotho, is a country landlocked as an enclave in South Africa. It is situated in the Maloti Mountains and contains the highest mountains in Southern Africa. It has an area of over and has a population ...

, the eastern Free State and in the Natal Drakensberg

The Drakensberg (Afrikaans: Drakensberge, Zulu: uKhahlambha, Sotho: Maluti) is the eastern portion of the Great Escarpment, which encloses the central Southern African plateau. The Great Escarpment reaches its greatest elevation – within t ...

. He undertook three expeditions to South West Africa

South West Africa ( af, Suidwes-Afrika; german: Südwestafrika; nl, Zuidwest-Afrika) was a territory under South African administration from 1915 to 1990, after which it became modern-day Namibia. It bordered Angola (Portuguese colony before 1 ...

and Rhodesia

Rhodesia (, ), officially from 1970 the Republic of Rhodesia, was an unrecognised state in Southern Africa from 1965 to 1979, equivalent in territory to modern Zimbabwe. Rhodesia was the ''de facto'' successor state to the British colony of So ...

between 1947 and 1950. He described this period as "the most thrilling years of my research life". He had excursions to South West Africa and Bechuanaland with a local Archeologist Kosie Marais

Jacobus Petrus (Kosie) Marais (22 June 1900 – 8 April 1963), was the son of Jacobus Petrus (Kowie) Marais and Catharina Elizabeth (Kitty) Eksteen. He was known for brandy-making.

Background

Marais grew up on the farm Wonderfontein close to ...

. In 1953 he announced his discovery of a painting about 6 000 years old, subsequently dubbed '' The White Lady'', under a rock overhang in the Brandberg Mountain

The Brandberg ( Damara: Dâures; hz, Omukuruvaro) is Namibia's highest mountain.

Location and extent

Brandberg Mountain is located in former Damaraland, now Erongo, in the northwestern Namib Desert, near the coast, and covers an area of a ...

.

Breuil returned to France in 1952 and produced a series of publications sponsored by the South African Government. Breuil's books contain valuable photographs and sketches of the art works at the sites he visited but are marred by official South African racism. Breuil developed elaborate scenarios to attribute "white" authorship to the paintings he studied. For example, he had a theory that the beautiful painting known as "The White Lady of the Brandberg" had been painted by Egyptians (or some other Mediterranean people), who had improbably made their way thousands of miles southwest into the wilds of Namibia, rather than accepting the logical and fairly obvious fact that the paintings were the product of (and clearly represent the lifestyle of) the Bushmen and other native peoples of Namibia and South Africa.

His contributions to European and African archaeology were considerable and recognised by the award of honorary doctorates from no fewer than six universities. He was President of the PanAfrican Archaeological Association

The PanAfrican Archaeological Association (PAA) is a pan-African professional organisation for archaeologists, geologists and palaeoanthropologists.

History

The association was founded by Louis Leakey and its first congress was held in Nairobi ...

from 1947 to 1955.

He died at L'Isle-Adam, Val-d'Oise

L'Isle-Adam () is a commune in the Val-d'Oise department in Île-de-France in northern France. The small town beside the river Oise has a long sandy beach and attracts visitors from Paris.

Geography

L'Isle-Adam is a commune and town in north ...

, France.

Published works

His works in English include: * ''Rock Paintings of Southern Andalusia: A Description of a Neolithic and Copper Age Art Group'' (with M.C. Burkitt and Montagu Pollock). Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1928. * ''The Cave of Altamira at Santillana del Mar, Spain'' (withHugo Obermaier

Hugo Obermaier (29 January 1877, in Regensburg – 12 November 1946, in Fribourg) was a distinguished Spanish-German prehistorian and anthropologist who taught at various European centres of learning. Although he was born in Germany, he was later ...

). Madrid, 1935.

* ''Four Hundred Centuries of Cave Art''. Montignac, Dordogne, 1952.

* ''The White Lady of the Brandberg'' (with Mary E. Boyle and E.R. Scherz). London: Faber and Faber; New York: Frederick A. Praeger, 1955.

* ''The Men of the Old Stone Age''. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1965.

* ''The Paintings of the Tsisab Ravine''

* ''The Rock Paintings of Southern Africa'' (with Mary E. Boyle)

See also

*Cave painting

In archaeology, Cave paintings are a type of parietal art (which category also includes petroglyphs, or engravings), found on the wall or ceilings of caves. The term usually implies prehistoric origin, and the oldest known are more than 40,000 ye ...

* Caves of Gargas

* Cave of the Trois Frères

* Cueva de La Pasiega

Cueva de La Pasiega, or Cave of La Pasiega, situated in the Spanish municipality of Puente Viesgo, is one of the most important monuments of Paleolithic art in Cantabria. It is included in the UNESCO World Heritage List since July 2008, as part ...

* Cave of Altamira

The Cave of Altamira (; es, Cueva de Altamira ) is a cave complex, located near the historic town of Santillana del Mar in Cantabria, Spain. It is renowned for prehistoric cave art featuring charcoal drawings and polychrome paintings of contem ...

* Pierre Teilhard de Chardin

Pierre Teilhard de Chardin ( (); 1 May 1881 – 10 April 1955) was a French Jesuit priest, scientist, paleontologist, theologian, philosopher and teacher. He was Darwinian in outlook and the author of several influential theological and philo ...

* List of Roman Catholic cleric–scientists

This is a list of Catholic clergy throughout history who have made contributions to science. These churchmen-scientists include Nicolaus Copernicus, Gregor Mendel, Georges Lemaître, Albertus Magnus, Roger Bacon, Pierre Gassendi, Roger Joseph B ...

* Les Combarelles

Les Combarelles is a cave in Les Eyzies-de-Tayac-Sireuil, Les Eyzies de Tayac, Dordogne, France, which was inhabited by Cro-Magnon people between approximately 13,000 to 11,000 years ago. Holding more than 600 prehistoric engravings of animals an ...

* Émile Cartailhac

References

Further reading

* Broderick, Alan Houghton. ''Father of Prehistory''. New York: William Morrow & Company, 1963 (published in Great Britain under the title ''The Abbé Breuil: Prehistorian''). * Arnaud Hurel, ''L'abbé Henri Breuil. Un préhistorien dans le siècle'', CNRS Éditions, 201Présentation du livre

* Straus, L.G. "L'Abbé Henri Breuil: Archaeologist", '' Bulletin of the History of Archaeology''. Vol. 2, No. 2. (1992), pp. 5–9. * Straus, L.G. "L'Abbé Henri Breuil: Pope of Paleolithic Prehistory", ''Homenaje al Dr. Joaquín González Echegaray''. Madrid: Museo y Centro de Investigación de Altamira, 1994, pp. 189–198.

External links

* "Les peintures préhistoriques de la grotte d'Altamira", Cartailhac and Breuil article (1903), online and analyzed oBibNum

lick 'à télécharger' for English version

Lick may refer to:

* Licking, the action of passing the tongue over a surface

Places

* Lick (crater), a crater on the Moon named after James Lick

* 1951 Lick, an asteroid named after James Lick

* Lick Township, Jackson County, Ohio, United Sta ...

/small>

{{DEFAULTSORT:Breuil, Henri

1877 births

1961 deaths

Catholic clergy scientists

French archaeologists

French Roman Catholic priests

Theistic evolutionists

Presidents of the South African Archaeological Society