Hellenistic-era warships on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

From the 4th century BC on, new types of oared warships appeared in the

From the 4th century BC on, new types of oared warships appeared in the

Far less is known with certainty about the construction and appearance of these ships than about the trireme. Literary evidence is fragmentary and highly selective, and pictorial evidence unclear. The fact that the trireme had three levels of oars (''trikrotos naus'') led medieval historians, long after the specifics of their construction had been lost, to speculate that the design of the "four", the "five" and the other later ships would proceed logically, i.e. that the quadrireme would have four rows of oars, the quinquereme five, etc. However, the eventual appearance of bigger polyremes ("sixes" and later "sevens", "eights", "nines", "tens", and even a massive " forty"), made this theory implausible. Consequently, during the

Far less is known with certainty about the construction and appearance of these ships than about the trireme. Literary evidence is fragmentary and highly selective, and pictorial evidence unclear. The fact that the trireme had three levels of oars (''trikrotos naus'') led medieval historians, long after the specifics of their construction had been lost, to speculate that the design of the "four", the "five" and the other later ships would proceed logically, i.e. that the quadrireme would have four rows of oars, the quinquereme five, etc. However, the eventual appearance of bigger polyremes ("sixes" and later "sevens", "eights", "nines", "tens", and even a massive " forty"), made this theory implausible. Consequently, during the

There were two chief design traditions in the Mediterranean, the Greek and the Punic ( Phoenician/Carthaginian) one, which was later copied by the Romans. As exemplified in the trireme, the Greeks used to project the upper level of oars through an

There were two chief design traditions in the Mediterranean, the Greek and the Punic ( Phoenician/Carthaginian) one, which was later copied by the Romans. As exemplified in the trireme, the Greeks used to project the upper level of oars through an

Perhaps the most famous of the Hellenistic-era warships, because of its extensive use by the Carthaginians and Romans, the quinquereme (Latin: ; el, πεντήρης, ''pentērēs'') was invented by the tyrant of

Perhaps the most famous of the Hellenistic-era warships, because of its extensive use by the Carthaginians and Romans, the quinquereme (Latin: ; el, πεντήρης, ''pentērēs'') was invented by the tyrant of

Very little is known about the octeres ( el, , ''oktērēs''). At least two of their type were in the fleet of

Very little is known about the octeres ( el, , ''oktērēs''). At least two of their type were in the fleet of

The tendency to build ever bigger ships that appeared in the last decades of the 4th century did not stop at the "ten".

The tendency to build ever bigger ships that appeared in the last decades of the 4th century did not stop at the "ten".

The ''trihemiolia'' ( el, ) first appears in accounts of the Siege of Rhodes by Demetrius Poliorcetes in 304 BC, where a squadron of ''trihemioliai'' was sent out as commerce raiders. The type was one of the chief vessels of the Rhodian navy, and it is very likely that it was also invented there, as a counter to the pirates' swift ''hemioliai''.Meijer (1986), p. 142 So great was the attachment of the Rhodians to this type of vessel, that for a century after their navy was abolished by

The ''trihemiolia'' ( el, ) first appears in accounts of the Siege of Rhodes by Demetrius Poliorcetes in 304 BC, where a squadron of ''trihemioliai'' was sent out as commerce raiders. The type was one of the chief vessels of the Rhodian navy, and it is very likely that it was also invented there, as a counter to the pirates' swift ''hemioliai''.Meijer (1986), p. 142 So great was the attachment of the Rhodians to this type of vessel, that for a century after their navy was abolished by

Le 'navire invaincu à neuf rangées de rameurs' de Pausanias (I, 29.1) et le 'Monument des Taureaux', à Delos

, in TROPIS III, ed. H. Tzalas, Athens. * * * * * * * * * J. S. Morrison and R. T. Williams, ''Greek Oared Ships: 900–322 BC'', Cambridge University Press, 1968. * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Hellenistic-Era Warships Galleys Military history of the Mediterranean

Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on ...

, superseding the trireme

A trireme( ; derived from Latin: ''trirēmis'' "with three banks of oars"; cf. Greek ''triērēs'', literally "three-rower") was an ancient navies and vessels, ancient vessel and a type of galley that was used by the ancient maritime civilizat ...

and transforming naval warfare

Naval warfare is combat in and on the sea, the ocean, or any other battlespace involving a major body of water such as a large lake or wide river. Mankind has fought battles on the sea for more than 3,000 years. Even in the interior of large la ...

. Ships became increasingly large and heavy, including some of the largest wooden ships hitherto constructed. These developments were spearheaded in the Hellenistic

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in ...

Near East

The ''Near East''; he, המזרח הקרוב; arc, ܕܢܚܐ ܩܪܒ; fa, خاور نزدیک, Xāvar-e nazdik; tr, Yakın Doğu is a geographical term which roughly encompasses a transcontinental region in Western Asia, that was once the hist ...

, but also to a large extent shared by the naval powers of the Western Mediterranean, specifically Carthage

Carthage was the capital city of Ancient Carthage, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the classi ...

and the Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( la, Res publica Romana ) was a form of government of Rome and the era of the classical Roman civilization when it was run through public representation of the Roman people. Beginning with the overthrow of the Roman Ki ...

. While the wealthy successor kingdoms in the East built huge warships ("polyremes"), Carthage and Rome, in the intense naval antagonism during the Punic Wars

The Punic Wars were a series of wars between 264 and 146BC fought between Rome and Carthage. Three conflicts between these states took place on both land and sea across the western Mediterranean region and involved a total of forty-three ye ...

, relied mostly on medium-sized vessels. At the same time, smaller naval powers employed an array of small and fast craft, which were also used by the ubiquitous pirates. Following the establishment of complete Roman hegemony in the Mediterranean after the Battle of Actium

The Battle of Actium was a naval battle fought between a maritime fleet of Octavian led by Marcus Agrippa and the combined fleets of both Mark Antony and Cleopatra VII Philopator. The battle took place on 2 September 31 BC in the Ionian Sea, ...

, the nascent Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Roman Republic, Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings aro ...

faced no major naval threats. In the 1st century AD, the larger warships were retained only as flagships and were gradually supplanted by the light liburnians

The Liburnians or Liburni ( grc, Λιβυρνοὶ) were an ancient tribe inhabiting the district called Liburnia, a coastal region of the northeastern Adriatic between the rivers ''Arsia'' ( Raša) and ''Titius'' ( Krka) in what is now Croati ...

until, by Late Antiquity

Late antiquity is the time of transition from classical antiquity to the Middle Ages, generally spanning the 3rd–7th century in Europe and adjacent areas bordering the Mediterranean Basin. The popularization of this periodization in English h ...

, the knowledge of their construction had been lost.

Terminology

Most of the warships of the era were distinguished by their names, which were compounds of a number and a suffix. Thus the English term quinquereme derives fromLatin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

and has the Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

equivalent (). Both are compounds featuring a prefix meaning "five": Latin , ancient Greek (). The Roman suffix is from , "oar": hence "five-oar". As the vessel cannot have had only five oars, the word must be a figure of speech meaning something else. There are a number of possibilities. The -ηρης occurs only in suffix form, deriving from (), "(I) row". As "rower" is () and "oar" is (), ''-ērēs'' does not mean either of those but, being based on the verb, must mean "rowing". This meaning is no clearer than the Latin. Whatever the "five-oar" or the "five-row" originally meant was lost with knowledge of the construction, and is, from the 5th century on, a hotly debated issue. For the history of the interpretation efforts and current scholarly consensus, see below

Below may refer to:

*Earth

* Ground (disambiguation)

*Soil

*Floor

* Bottom (disambiguation)

*Less than

*Temperatures below freezing

*Hell or underworld

People with the surname

*Ernst von Below (1863–1955), German World War I general

*Fred Below ...

.

Evolution of design

In the great wars of the 5th century BC, such as thePersian Wars

The Greco-Persian Wars (also often called the Persian Wars) were a series of conflicts between the Achaemenid Empire and Greek city-states that started in 499 BC and lasted until 449 BC. The collision between the fractious political world of the ...

and the Peloponnesian War

The Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC) was an ancient Greek war fought between Athens and Sparta and their respective allies for the hegemony of the Greek world. The war remained undecided for a long time until the decisive intervention of ...

, the trireme

A trireme( ; derived from Latin: ''trirēmis'' "with three banks of oars"; cf. Greek ''triērēs'', literally "three-rower") was an ancient navies and vessels, ancient vessel and a type of galley that was used by the ancient maritime civilizat ...

was the heaviest type of warship used by the Mediterranean navies. The trireme (Greek: (), "three-oared") was propelled by three banks of oars, with one oarsman each. During the early 4th century BC, however, variants of the trireme design began to appear: invention of the quinquereme (Gk.: (), "five-oared") and the hexareme (Gk. ''hexērēs'', "six-oared") is credited by the historian Diodorus Siculus

Diodorus Siculus, or Diodorus of Sicily ( grc-gre, Διόδωρος ; 1st century BC), was an ancient Greek historian. He is known for writing the monumental universal history '' Bibliotheca historica'', in forty books, fifteen of which ...

to the tyrant Dionysius I of Syracuse

Dionysius I or Dionysius the Elder ( 432 – 367 BC) was a Greek tyrant of Syracuse, in Sicily. He conquered several cities in Sicily and southern Italy, opposed Carthage's influence in Sicily and made Syracuse the most powerful of the Western Gre ...

, while the quadrireme (Gk. ''tetrērēs'', "four-oared") was credited by Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ...

to the Carthaginians

The Punic people, or western Phoenicians, were a Semitic people in the Western Mediterranean who migrated from Tyre, Phoenicia to North Africa during the Early Iron Age. In modern scholarship, the term ''Punic'' – the Latin equivalent of the ...

.

Oar system

Far less is known with certainty about the construction and appearance of these ships than about the trireme. Literary evidence is fragmentary and highly selective, and pictorial evidence unclear. The fact that the trireme had three levels of oars (''trikrotos naus'') led medieval historians, long after the specifics of their construction had been lost, to speculate that the design of the "four", the "five" and the other later ships would proceed logically, i.e. that the quadrireme would have four rows of oars, the quinquereme five, etc. However, the eventual appearance of bigger polyremes ("sixes" and later "sevens", "eights", "nines", "tens", and even a massive " forty"), made this theory implausible. Consequently, during the

Far less is known with certainty about the construction and appearance of these ships than about the trireme. Literary evidence is fragmentary and highly selective, and pictorial evidence unclear. The fact that the trireme had three levels of oars (''trikrotos naus'') led medieval historians, long after the specifics of their construction had been lost, to speculate that the design of the "four", the "five" and the other later ships would proceed logically, i.e. that the quadrireme would have four rows of oars, the quinquereme five, etc. However, the eventual appearance of bigger polyremes ("sixes" and later "sevens", "eights", "nines", "tens", and even a massive " forty"), made this theory implausible. Consequently, during the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ide ...

and until the 19th century, it came to be believed that the rowing system of the trireme and its descendants was similar to the ''alla sensile'' system of the contemporary galleys, comprising multiple oars on each level, rowed by one oarsman each. 20th-century scholarship disproved that theory, and established that the ancient warships were rowed at different levels, with three providing the maximum practical limit. The higher numbers of the "fours", "fives", etc. were therefore interpreted as reflecting the number of files of oarsmen on each side of the ship, and not an increased number of rows of oars.

The most common theory on the arrangement of oarsmen in the new ship types is that of "double-banking", i.e., that the quadrireme was derived from a bireme

A bireme (, ) is an ancient oared warship (galley) with two superimposed rows of oars on each side. Biremes were long vessels built for military purposes and could achieve relatively high speed. They were invented well before the 6th century BC a ...

(warship with two rows of oars) by placing two oarsmen on each oar, the quinquereme from a trireme by placing two oarsmen on the two uppermost levels (the ''thranitai'' and ''zygitai'', according to Greek terminology), and the later hexareme by placing two rowers on every level. Other interpretations of the quinquereme include a bireme warship with three and two oarsmen on the upper and lower oar banks, or even a monoreme (warship with a single level of oars) with five oarsmen. The "double-banking" theory is supported by the fact that the 4th-century quinqueremes were housed in the same ship sheds as the triremes, and must therefore have had similar width (), which fits with the idea of an evolutionary progression from the one type to the other.

The reasons for the evolution of the polyremes are not very clear. The most often forwarded argument is one of lack of skilled manpower: the trireme was essentially a ship built for ramming

In warfare, ramming is a technique used in air, sea, and land combat. The term originated from battering ram, a siege weapon used to bring down fortifications by hitting it with the force of the ram's momentum, and ultimately from male sheep. Thus, ...

, and successful ramming tactics depended chiefly on the constant maintenance of a highly trained oar crew, something which few states aside from Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates a ...

with its radical democracy

Radical democracy is a type of democracy that advocates the radical extension of equality and liberty. Radical democracy is concerned with a radical extension of equality and freedom, following the idea that democracy is an unfinished, inclusive, ...

had the funds or the social structure to do. Using multiple oarsmen reduced the number of such highly trained men needed in each crew: only the rower at the tip of the oar had to be sufficiently trained, and he could then lead the others, who simply provided additional motive power. This system was also in use in Renaissance galleys, but jars with the evidence of ancient crews continuing to be thoroughly trained by their commanders. The increased number of oarsmen also required a broader hull, which on the one hand reduced the ships' speed, but on the other offered several advantages: larger vessels could be strengthened to better withstand ramming, while the wider hull increased their carrying capacity, allowing more marines

Marines, or naval infantry, are typically a military force trained to operate in littoral zones in support of naval operations. Historically, tasks undertaken by marines have included helping maintain discipline and order aboard the ship (refl ...

, and eventually catapults, to be carried along. The decks of these ships were also higher above the waterline, while their increased beam afforded them extra stability, making them superior missile platforms. This was an important fact in an age where naval engagements were increasingly decided not by ramming but by less technically demanding boarding actions. It has even been suggested by Lionel Casson that the quinqueremes used by the Romans in the Punic Wars of the 3rd century were of the monoreme design (i.e., with one level and five rowers on each oar), being thus able to carry the large contingent of 120 marines attested for the Battle of Ecnomus.

An evolution to larger ships was also desirable because they were better able to survive a bow-on-bow ramming engagement, which allowed for increased tactical flexibility over the older, smaller ships which were limited to broad-side ramming. Once bigger ships had become common, they proved their usefulness in siege operations against coastal cities, such as the siege of Tyre by Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip II to ...

, as well as numerous siege operations carried out by his successors, such as the siege of Rhodes by Demetrius Poliorcetes

Demetrius I (; grc, Δημήτριος; 337–283 BC), also called Poliorcetes (; el, Πολιορκητής, "The Besieger"), was a Macedonian nobleman, military leader, and king of Macedon (294–288 BC). He belonged to the Antigonid dynasty ...

.

Construction

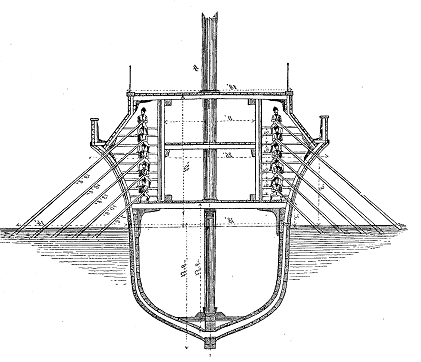

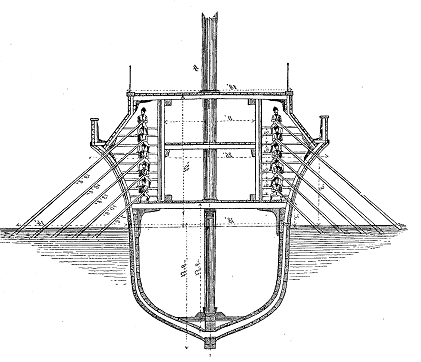

There were two chief design traditions in the Mediterranean, the Greek and the Punic ( Phoenician/Carthaginian) one, which was later copied by the Romans. As exemplified in the trireme, the Greeks used to project the upper level of oars through an

There were two chief design traditions in the Mediterranean, the Greek and the Punic ( Phoenician/Carthaginian) one, which was later copied by the Romans. As exemplified in the trireme, the Greeks used to project the upper level of oars through an outrigger

An outrigger is a projecting structure on a boat, with specific meaning depending on types of vessel. Outriggers may also refer to legs on a wheeled vehicle that are folded out when it needs stabilization, for example on a crane that lifts ...

(''parexeiresia''), while the later Punic tradition heightened the ship, and had all three tiers of oars projecting directly from the side hull.

Based on iconographic evidence from coins, Morrison and Coates have determined that the Punic triremes in the 5th and early 4th centuries BC were largely similar to their Greek counterparts, most likely including an outrigger. From the mid-4th century, however, at about the time the quinquereme was introduced in Phoenicia, there is evidence of ships without outriggers. This would have necessitated a different oar arrangement, with the middle level placed more inwards, as well as a different construction of the hull, with side-decks attached to it. From the middle of the 3rd century BC onwards, Carthaginian "fives" display a separate "oar box" that contained the rowers and that was attached to the main hull. This development of the earlier model entailed further modifications, meaning that the rowers would be located above deck, and essentially on the same level. This would allow the hull to be strengthened, and have increased carrying capacity in consumable supplies, as well as improve the ventilation conditions of the rowers, an especially important factor in maintaining their stamina, and thereby improving the ship's maintainable speed. It is unclear however whether this design was applied to heavier warships, and although the Romans copied the Punic model for their quinqueremes, there is ample iconographic evidence of outrigger-equipped warships used until the late imperial period.

In the Athenian Sicilian Expedition

The Sicilian Expedition was an Athenian military expedition to Sicily, which took place from 415–413 BC during the Peloponnesian War between Athens on one side and Sparta, Syracuse and Corinth on the other. The expedition ended in a de ...

of 415–413 BC, it became apparent that the topmost tier of rowers, the ''thranitai'', of the "aphract" (un-decked and unarmoured) Athenian triremes were vulnerable to attack by arrows and catapults. Given the prominence of close-quarters boarding actions in later years, vessels were built as "cataphract" ships, with a closed hull to protect the rowers, and a full deck able to carry marines and catapults.

Heavy warships

Quadrireme

Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/2479), called Pliny the Elder (), was a Roman author, naturalist and natural philosopher, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the emperor Vespasian. He wrote the encyclopedic ' ...

reports that Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ...

ascribed the invention of the quadrireme ( la, quadriremis; el, τετρήρης, ''tetrērēs'') to the Carthaginians

The Punic people, or western Phoenicians, were a Semitic people in the Western Mediterranean who migrated from Tyre, Phoenicia to North Africa during the Early Iron Age. In modern scholarship, the term ''Punic'' – the Latin equivalent of the ...

. Although the exact date is unknown, it is most likely the type was developed in the latter half of the 4th century BC. Their first attested appearance is at the Siege of Tyre by Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip II to ...

in 332 BC, and a few years later, they appear in the surviving naval lists of Athens. In the period after Alexander's death (323 BC), the quadrireme proved very popular: the Athenians made plans to build 200 of these ships, and 90 out of 240 ships of the fleet of Antigonus I Monophthalmus

Antigonus I Monophthalmus ( grc-gre, Ἀντίγονος Μονόφθαλμος , 'the One-Eyed'; 382 – 301 BC), son of Philip from Elimeia, was a Macedonian Greek nobleman, general, satrap, and king. During the first half of his life he serv ...

(r. 306–301 BC) were "fours". Subsequently, the quadrireme was favoured as the main warship of the Rhodian navy, the sole professional naval force in the Eastern Mediterranean. In the Battle of Naulochus in 36 BC, "fours" were the most common ship type fielded by the fleet of Sextus Pompeius, and several ships of this kind are recorded in the two praetorian fleets of the Imperial Roman navy.

It is known from references from both the Second Punic War

The Second Punic War (218 to 201 BC) was the second of three wars fought between Carthage and Rome, the two main powers of the western Mediterranean in the 3rd century BC. For 17 years the two states struggled for supremacy, primarily in Ital ...

and the Battle of Mylae

The Battle of Mylae took place in 260 BC during the First Punic War and was the first real naval battle between Carthage and the Roman Republic. This battle was key in the Roman victory of Mylae (present-day Milazzo) as well as Sicily itself. It ...

that the quadrireme had two levels of oarsmen, and was therefore lower than the quinquereme, while being of about the same width (). Its displacement must have been around 60 tonnes, and its carrying capacity at marines. It was especially valued for its great speed and manoeuvrability, while its relatively shallow draught made it ideal for coastal operations. The "four" was classed as a "major ship" (''maioris formae'') by the Romans, but as a light craft, serving alongside triremes, in the navies of the major Hellenistic kingdoms like Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning the North Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via a land bridg ...

.

Quinquereme

Perhaps the most famous of the Hellenistic-era warships, because of its extensive use by the Carthaginians and Romans, the quinquereme (Latin: ; el, πεντήρης, ''pentērēs'') was invented by the tyrant of

Perhaps the most famous of the Hellenistic-era warships, because of its extensive use by the Carthaginians and Romans, the quinquereme (Latin: ; el, πεντήρης, ''pentērēs'') was invented by the tyrant of Syracuse

Syracuse may refer to:

Places Italy

* Syracuse, Sicily, or spelled as ''Siracusa''

* Province of Syracuse

United States

*Syracuse, New York

**East Syracuse, New York

** North Syracuse, New York

* Syracuse, Indiana

*Syracuse, Kansas

*Syracuse, M ...

, Dionysius I (r. 405–367 BC) in 399 BC, as part of a major naval armament program directed against the Carthaginians. During most of the 4th century, the "fives" were the heaviest type of warship, and often used as flagships of fleets composed of triremes and quadriremes. Sidon

Sidon ( ; he, צִידוֹן, ''Ṣīḏōn'') known locally as Sayda or Saida ( ar, صيدا ''Ṣaydā''), is the third-largest city in Lebanon. It is located in the South Governorate, of which it is the capital, on the Mediterranean coast. ...

had them by 351, and Athens fielded some in 324.

In the eastern Mediterranean, they were superseded as the heaviest ships by the massive polyremes that began appearing in the last two decades of the 4th century, but in the West, they remained the mainstay of the Carthaginian navy. When the Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( la, Res publica Romana ) was a form of government of Rome and the era of the classical Roman civilization when it was run through public representation of the Roman people. Beginning with the overthrow of the Roman Ki ...

, which hitherto lacked a significant navy, was embroiled in the First Punic War

The First Punic War (264–241 BC) was the first of Punic Wars, three wars fought between Roman Republic, Rome and Ancient Carthage, Carthage, the two main powers of the western Mediterranean in the early 3rd century BC. For 23 years ...

with Carthage, the Roman Senate

The Roman Senate ( la, Senātus Rōmānus) was a governing and advisory assembly in ancient Rome. It was one of the most enduring institutions in Roman history, being established in the first days of the city of Rome (traditionally founded in ...

set out to construct a fleet of 100 quinqueremes and 20 triremes. According to Polybius

Polybius (; grc-gre, Πολύβιος, ; ) was a Greek historian of the Hellenistic period. He is noted for his work , which covered the period of 264–146 BC and the Punic Wars in detail.

Polybius is important for his analysis of the mixed ...

, the Romans seized a shipwrecked Carthaginian quinquereme and used it as a blueprint for their own ships, but it is stated that the Roman copies were heavier than the Carthaginian vessels, which were better built. The quinquereme provided the workhorse of the Roman and Carthaginian fleets throughout their conflicts, although "fours" and "threes" are also mentioned. Indeed, so ubiquitous was the type that Polybius uses it as a shorthand for "warship" in general.

According to Polybius, at the Battle of Cape Ecnomus, the Roman quinqueremes carried a total crew of 420, 300 of whom were rowers, and the rest marines. Leaving aside a deck crew of men, and accepting the 2–2–1 pattern of oarsmen, the quinquereme would have 90 oars in each side, and 30-strong files of oarsmen. The fully decked quinquereme could also carry a marine detachment of 70 to 120, giving a total complement of about 400. A "five" would be long, displace around 100 tonnes, be some 5 m wide at water level, and have its deck standing above the sea. Polybius said the quinquereme was superior to the old trireme, which was retained in service in significant numbers by many smaller navies. Accounts by Livy

Titus Livius (; 59 BC – AD 17), known in English as Livy ( ), was a Roman historian. He wrote a monumental history of Rome and the Roman people, titled , covering the period from the earliest legends of Rome before the traditional founding in ...

and Diodorus Siculus

Diodorus Siculus, or Diodorus of Sicily ( grc-gre, Διόδωρος ; 1st century BC), was an ancient Greek historian. He is known for writing the monumental universal history '' Bibliotheca historica'', in forty books, fifteen of which ...

also show that the "five", being heavier, performed better than the triremes in bad weather.

The Republic of Venice

The Republic of Venice ( vec, Repùblega de Venèsia) or Venetian Republic ( vec, Repùblega Vèneta, links=no), traditionally known as La Serenissima ( en, Most Serene Republic of Venice, italics=yes; vec, Serenìsima Repùblega de Venèsia ...

in the 1520s built what was called a quinquereme based on the design of Vettor Fausto, who based it off of his readings of classical texts.

Hexareme

The hexareme or sexireme ( la, hexēris; el, , ''hexērēs'') is affirmed by the ancient historians Pliny the Elder and Aelian to have been invented in Syracuse. "Sixes" were certainly present in the fleet ofDionysius II of Syracuse

Dionysius the Younger ( el, Διονύσιος ὁ Νεώτερος, 343 BC), or Dionysius II, was a Greek politician who ruled Syracuse, Sicily from 367 BC to 357 BC and again from 346 BC to 344 BC.

Biography

Dionysius II of Syracuse was the s ...

(r. 367–357 and 346–344 BC), but they may well have been invented in the last years of his father, Dionysius I. "Sixes" were rarer than smaller vessels, and appear in the sources chiefly as flagships: at the Battle of Ecnomus, the two Roman consul

A consul held the highest elected political office of the Roman Republic ( to 27 BC), and ancient Romans considered the consulship the second-highest level of the ''cursus honorum'' (an ascending sequence of public offices to which politic ...

s each had a hexareme, Ptolemy XII

Ptolemy XII Neos Dionysus Philopator Philadelphus ( grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος Νέος Διόνυσος Φιλοπάτωρ Φιλάδελφος, Ptolemaios Neos Dionysos Philopatōr Philadelphos; – 51 BC) was a pharaoh of the Ptolemaic ...

(r. 80–58 and 55–51 BC) had one as his personal flagship, as did Sextus Pompeius. At the Battle of Actium

The Battle of Actium was a naval battle fought between a maritime fleet of Octavian led by Marcus Agrippa and the combined fleets of both Mark Antony and Cleopatra VII Philopator. The battle took place on 2 September 31 BC in the Ionian Sea, ...

, hexaremes were present in both fleets, but with a notable difference: while in the fleet of Octavian

Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian, was the first Roman emperor; he reigned from 27 BC until his death in AD 14. He is known for being the founder of the Roman Pr ...

they were the heaviest type of vessel, in the fleet of Mark Antony

Marcus Antonius (14 January 1 August 30 BC), commonly known in English as Mark Antony, was a Roman politician and general who played a critical role in the transformation of the Roman Republic from a constitutional republic into the au ...

they were the second smallest, after the quinqueremes. A single hexareme, the ''Ops'', is later recorded as the heaviest ship serving in the praetorian Fleet of Misenum.

The exact arrangement of the hexareme's oars is unclear. If it evolved naturally from the earlier designs, it would be a trireme with two rowers per oar; the less likely alternative is that it had two levels with three oarsmen at each. Reports about "sixes" used during the 1st-century BC Roman civil wars indicate that they were of a similar height to the quinqueremes, and record the presence of towers on the deck of a "six" serving as flagship to Marcus Junius Brutus

Marcus Junius Brutus (; ; 85 BC – 23 October 42 BC), often referred to simply as Brutus, was a Roman politician, orator, and the most famous of the assassins of Julius Caesar. After being adopted by a relative, he used the name Quintus Ser ...

.

Septireme

Pliny the Elder attributes the creation of the septireme ( la, septiremis; el, , ''heptērēs'') to Alexander the Great.Pliny, ''Natural History'', VII.206 Curtius corroborates this, and reports that the king gave orders for wood for 700 septiremes to be cut inMount Lebanon

Mount Lebanon ( ar, جَبَل لُبْنَان, ''jabal lubnān'', ; syr, ܛܘܪ ܠܒ݂ܢܢ, ', , ''ṭūr lewnōn'' french: Mont Liban) is a mountain range in Lebanon. It averages above in elevation, with its peak at .

Geography

The Mount Le ...

, to be used in his projected circumnavigations of the Arabian peninsula

The Arabian Peninsula, (; ar, شِبْهُ الْجَزِيرَةِ الْعَرَبِيَّة, , "Arabian Peninsula" or , , "Island of the Arabs") or Arabia, is a peninsula of Western Asia, situated northeast of Africa on the Arabian Plat ...

and Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

. For Salamis, Demetrius Poliorcetes

Demetrius I (; grc, Δημήτριος; 337–283 BC), also called Poliorcetes (; el, Πολιορκητής, "The Besieger"), was a Macedonian nobleman, military leader, and king of Macedon (294–288 BC). He belonged to the Antigonid dynasty ...

had seven such ships built in Phoenicia and, later, Ptolemy II

; egy, Userkanaenre Meryamun Clayton (2006) p. 208

, predecessor = Ptolemy I

, successor = Ptolemy III

, horus = ''ḥwnw-ḳni'Khunuqeni''The brave youth

, nebty = ''wr-pḥtj'Urpekhti''Great of strength

, gold ...

(r. 283–246 BC) had 36 septiremes constructed. Pyrrhus of Epirus

Pyrrhus (; grc-gre, Πύρρος ; 319/318–272 BC) was a Greek king and statesman of the Hellenistic period.Plutarch. '' Parallel Lives'',Pyrrhus... He was king of the Greek tribe of Molossians, of the royal Aeacid house, and later he be ...

(r. 306–302 and 297–272 BC) also apparently had at least one "seven", which was captured by the Carthaginians and eventually lost at Mylae.

Presumably, the septireme was derived by adding a standing rower to the lower level of the hexareme.

Octeres

Very little is known about the octeres ( el, , ''oktērēs''). At least two of their type were in the fleet of

Very little is known about the octeres ( el, , ''oktērēs''). At least two of their type were in the fleet of Philip V of Macedon

Philip V ( grc-gre, Φίλιππος ; 238–179 BC) was king ( Basileus) of Macedonia from 221 to 179 BC. Philip's reign was principally marked by an unsuccessful struggle with the emerging power of the Roman Republic. He would lead Macedon a ...

(r. 221–179 BC) at the Battle of Chios in 201 BC, where they were rammed in their prows. Their last appearance was at Actium, where Mark Antony is said by Plutarch

Plutarch (; grc-gre, Πλούταρχος, ''Ploútarchos''; ; – after AD 119) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for hi ...

to have had many "eights". Based on the comments of Orosius

Paulus Orosius (; born 375/385 – 420 AD), less often Paul Orosius in English, was a Roman priest, historian and theologian, and a student of Augustine of Hippo. It is possible that he was born in ''Bracara Augusta'' (now Braga, Portugal), t ...

that the larger ships in Antony's fleet were only as high as the quinqueremes (their deck standing at above water), it is presumed that "eights", as well as the "nines" and "tens", were rowed at two levels.

An exceptionally large "eight", the Leontophoros, is recorded by Memnon of Heraclea Memnon of Heraclea (; grc-gre, Mέμνων, ''gen''.: Μέμνονος; fl. c. 1st century) was a Greek historical writer, probably a native of Heraclea Pontica. He described the history of that city in a large work, known only through the ''Exce ...

to have been built by Lysimachus

Lysimachus (; Greek: Λυσίμαχος, ''Lysimachos''; c. 360 BC – 281 BC) was a Thessalian officer and successor of Alexander the Great, who in 306 BC, became King of Thrace, Asia Minor and Macedon.

Early life and career

Lysimachus wa ...

(r. 306–281 BC), one of the Diadochi

The Diadochi (; singular: Diadochus; from grc-gre, Διάδοχοι, Diádochoi, Successors, ) were the rival generals, families, and friends of Alexander the Great who fought for control over his empire after his death in 323 BC. The War ...

. It was richly decorated, required 1,600 rowers (8 files of 100 per side) and could support 1,200 marines. Remarkably for a ship of its size, its performance at sea was reportedly very good the Roman’s used them as troop carriers and flagships .

Enneres

The enneres ( el, ) is first recorded in 315 BC, when three of their type were included in the fleet of Antigonus Monophthalmus. The presence of "nines" in Antony's fleet at Actium is recorded by Florus andCassius Dio

Lucius Cassius Dio (), also known as Dio Cassius ( ), was a Roman historian and senator of maternal Greek origin. He published 80 volumes of the history on ancient Rome, beginning with the arrival of Aeneas in Italy. The volumes documented the ...

, although Plutarch makes explicit mention only of "eights" and "tens". The oaring system may have been a modification of the quadrireme, with two teams of five and four oarsmen.

Deceres

Like the septireme, the ( el, , ''dekērēs'') is attributed by Pliny to Alexander the Great, and they are present alongside "nines" in the fleet of Antigonus Monophthalmus in 315 BC. Indeed, it is most likely that the "ten" was derived from adding another oarsman to the "nine". A "ten" is mentioned as Philip V's flagship at Chios in 201 BC, and their last appearance was at Actium, where they constituted Antony's heaviest ships.Larger polyremes

Demetrius Poliorcetes

Demetrius I (; grc, Δημήτριος; 337–283 BC), also called Poliorcetes (; el, Πολιορκητής, "The Besieger"), was a Macedonian nobleman, military leader, and king of Macedon (294–288 BC). He belonged to the Antigonid dynasty ...

built "elevens", "thirteens", "fourteens", "fifteens" and "sixteens", and his son, Antigonus II Gonatas

Antigonus II Gonatas ( grc-gre, Ἀντίγονος Γονατᾶς, ; – 239 BC) was a Macedonian ruler who solidified the position of the Antigonid dynasty in Macedon after a long period defined by anarchy and chaos and acquired fame for hi ...

had an "eighteen", while Ptolemy II's navy fielded 14 "elevens", 2 "twelves", 4 "thirteens", and even one "twenty" and two "thirties". Eventually, Ptolemy IV

egy, Iwaennetjerwymenkhwy Setepptah Userkare Sekhemankhamun Clayton (2006) p. 208.

, predecessor = Ptolemy III

, successor = Ptolemy V

, horus = ''ḥnw-ḳni sḫꜤi.n-sw-it.f'Khunuqeni sekhaensuitef'' The strong youth whose f ...

built a "forty" ('' tessarakonteres'') that was 130m long, required 4,000 rowers and 400 other crew, and could support a force of 2,850 marines on its decks. However, "tens" seem to be the largest to have been used in battle.

The larger polyremes were possibly double-hulled catamaran

A Formula 16 beachable catamaran

Powered catamaran passenger ferry at Salem, Massachusetts, United States

A catamaran () (informally, a "cat") is a multi-hulled watercraft featuring two parallel hulls of equal size. It is a geometry-sta ...

s. It has been suggested that, with the exception of the "forty", these ships must have been rowed at two levels.

Light warships

Several types of fast vessels were used during this period, the successors of the 6th and 5th-century BC triacontors (τριακόντοροι, ''triakontoroi'', "thirty-oars") and pentecontors (πεντηκόντοροι, ''pentēkontoroi'', "fifty-oars"). Their primary use was in piracy and scouting, but they also found their place in the battle line.

Lembos

The term ''lembos'' (from el, λέμβος, "skiff", inLatin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

''lembus'') is used generically for boats or light vessels, and more specifically for a light warship, most commonly associated with the vessels used by the Illyrian tribes, chiefly for piracy, in the area of Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; hr, Dalmacija ; it, Dalmazia; see names in other languages) is one of the four historical regions of Croatia, alongside Croatia proper, Slavonia, and Istria. Dalmatia is a narrow belt of the east shore of the Adriatic Sea, str ...

. This type of craft was also adopted by Philip V of Macedon, and soon after by the Seleucids

The Seleucid Empire (; grc, Βασιλεία τῶν Σελευκιδῶν, ''Basileía tōn Seleukidōn'') was a Greek state in West Asia that existed during the Hellenistic period from 312 BC to 63 BC. The Seleucid Empire was founded by the M ...

, Rome, and even the Sparta

Sparta ( Doric Greek: Σπάρτα, ''Spártā''; Attic Greek: Σπάρτη, ''Spártē'') was a prominent city-state in Laconia, in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (, ), while the name Sparta referr ...

n king Nabis

Nabis ( grc-gre, Νάβις) was the last king of independent Sparta. He was probably a member of the Heracleidae, and he ruled from 207 BC to 192 BC, during the years of the First and Second Macedonian Wars and the eponymous " War against Nab ...

in his attempt to rebuild the Spartan navy.

In contemporary writings, the name was associated with a class rather than a specific type of vessels, as considerable variation is evident in the sources: the number of oars ranged from 16 to 50, they could be one- or double-banked, and some types did not have a ram, presumably being used as couriers and fast cargo vessels.

Hemiolia

The ''hemiolia'' or ''hemiolos'' ( el, or ) was a light and fast warship that appeared in the early 4th century BC. It was particularly favoured by pirates in the eastern Mediterranean, but also used by Alexander the Great as far as the riversIndus

The Indus ( ) is a transboundary river of Asia and a trans-Himalayan river of South and Central Asia. The river rises in mountain springs northeast of Mount Kailash in Western Tibet, flows northwest through the disputed region of Kashmir, ...

and Hydaspes, and by the Romans as a troop transport. It is likely that the type was invented by pirates, probably in Caria

Caria (; from Greek: Καρία, ''Karia''; tr, Karya) was a region of western Anatolia extending along the coast from mid- Ionia (Mycale) south to Lycia and east to Phrygia. The Ionian and Dorian Greeks colonized the west of it and joine ...

.

Little is known of their characteristics, but Arrian

Arrian of Nicomedia (; Greek: ''Arrianos''; la, Lucius Flavius Arrianus; )

was a Greek historian, public servant, military commander and philosopher of the Roman period.

''The Anabasis of Alexander'' by Arrian is considered the best ...

, based on Ptolemy I

Ptolemy I Soter (; gr, Πτολεμαῖος Σωτήρ, ''Ptolemaîos Sōtḗr'' "Ptolemy the Savior"; c. 367 BC – January 282 BC) was a Macedonian Greek general, historian and companion of Alexander the Great from the Kingdom of Macedo ...

(r. 323–283 BC), includes them amongst the triacontors. According to one view, it was manned by half the number of oarsmen to make room for the fighters. According to another, there were one and a half files of oarsmen on each side, with the additional half file placed amidships, where the hull was wide enough to accommodate them. In this view, they could have had 15 oars on each side, with a full file of ten and a half file of five or instead the middle oars may have been double-manned. Given their lighter hulls, greater length and generally slimmer profile, the hemiolia would have had an advantage in speed even over other light warships like the liburnian.

Trihemiolia

The ''trihemiolia'' ( el, ) first appears in accounts of the Siege of Rhodes by Demetrius Poliorcetes in 304 BC, where a squadron of ''trihemioliai'' was sent out as commerce raiders. The type was one of the chief vessels of the Rhodian navy, and it is very likely that it was also invented there, as a counter to the pirates' swift ''hemioliai''.Meijer (1986), p. 142 So great was the attachment of the Rhodians to this type of vessel, that for a century after their navy was abolished by

The ''trihemiolia'' ( el, ) first appears in accounts of the Siege of Rhodes by Demetrius Poliorcetes in 304 BC, where a squadron of ''trihemioliai'' was sent out as commerce raiders. The type was one of the chief vessels of the Rhodian navy, and it is very likely that it was also invented there, as a counter to the pirates' swift ''hemioliai''.Meijer (1986), p. 142 So great was the attachment of the Rhodians to this type of vessel, that for a century after their navy was abolished by Gaius Cassius Longinus

Gaius Cassius Longinus (c. 86 BC – 3 October 42 BC) was a Roman senator and general best known as a leading instigator of the plot to assassinate Julius Caesar on 15 March 44 BC. He was the brother-in-law of Brutus, another leader of the co ...

in 46 BC, they kept a few as ceremonial vessels.

The type was classed with the trireme, and had two and a half files of oarsmen on each side. Judging from the Lindos relief and the famous Nike of Samothrace, both of which are thought to represent ''trihemioliai'', the two upper files would have been accommodated in an oarbox, with the half-file located beneath them in the classic ''thalamitai'' position of the trireme. The Lindos relief also includes a list of the crews of two ''trihemioliai'', allowing us to deduce that each was crewed by 144 men, 120 of whom were rowers (hence a full file numbered 24). Reconstruction based on the above sculptures shows that the ship was relatively low, with a boxed-in superstructure, a displacement of tonnes, and capable of reaching speeds comparable with those of a full trireme. The ''trihemiolia'' was a very successful design, and was adopted by the navies of Ptolemaic Egypt and Athens among others. Despite being classed as lighter warships, they were sometimes employed in a first-line role, for instance at the Battle of Chios.

Liburnians

Theliburnian

The Liburnians or Liburni ( grc, Λιβυρνοὶ) were an ancient tribe inhabiting the district called Liburnia, a coastal region of the northeastern Adriatic between the rivers ''Arsia'' ( Raša) and ''Titius'' ( Krka) in what is now Croati ...

( la, liburna, el, λιβυρνίς, ''libyrnis'') was a variant of ''lembos'' invented by the tribe of the Liburnians

The Liburnians or Liburni ( grc, Λιβυρνοὶ) were an ancient tribe inhabiting the district called Liburnia, a coastal region of the northeastern Adriatic between the rivers ''Arsia'' ( Raša) and ''Titius'' ( Krka) in what is now Croati ...

. Initially used for piracy and scouting, this light and swift vessel was adopted by the Romans during the Illyrian Wars

The Illyro-Roman Wars were a series of wars fought between the Roman Republic and the Ardiaei kingdom. In the ''First Illyrian War'', which lasted from 229 BC to 228 BC, Rome's concern was that the trade across the Adriatic Sea increased after the ...

, and eventually became the mainstay of the fleets of the Roman Empire following Actium, displacing the heavier vessels. Especially the provincial Roman fleets were composed almost exclusively of liburnians. Livy, Lucan

Marcus Annaeus Lucanus (3 November 39 AD – 30 April 65 AD), better known in English as Lucan (), was a Roman poet, born in Corduba (modern-day Córdoba), in Hispania Baetica. He is regarded as one of the outstanding figures of the Imperial ...

and Appian

Appian of Alexandria (; grc-gre, Ἀππιανὸς Ἀλεξανδρεύς ''Appianòs Alexandreús''; la, Appianus Alexandrinus; ) was a Greek historian with Roman citizenship who flourished during the reigns of Emperors of Rome Trajan, Ha ...

all describe the liburnian as bireme; they were fully decked (cataphract) ships, with a sharply pointed prow, providing a more streamlined shape designed for greater speed. In terms of speed, the liburnian was probably considerably slower than a trireme, but on a par with a "five".

Armament and tactics

A change in the technology of conflict had taken place to allow these juggernauts of the seas to be created, as the development of catapults had neutralised the power of the ram, and speed and maneuverability were no longer as important as they had been. It was easy to mount catapults on galleys; Alexander the Great had used them to considerable effect when he besieged Tyre from the sea in 332 BC. The catapults did not aim to sink the enemy galleys, but rather to injure or kill the rowers (as a significant number of rowers out of place on either side would ruin the performance of the entire ship and prevent its ram from being effective). Now combat at sea returned to the boarding and fighting that it had been before the development of the ram, and larger galleys could carry more soldiers. Some of the later galleys were monstrous in size, with oars as long as 17 metres each pulled by as many as eight banks of rowers. With so many rowers, if one of them was killed by a catapult shot, the rest could continue and not interrupt the stroke. The innermost oarsman on such a galley had to step forward and back a few paces with each stroke.References

Sources

*Lucien Basch (1989)Le 'navire invaincu à neuf rangées de rameurs' de Pausanias (I, 29.1) et le 'Monument des Taureaux', à Delos

, in TROPIS III, ed. H. Tzalas, Athens. * * * * * * * * * J. S. Morrison and R. T. Williams, ''Greek Oared Ships: 900–322 BC'', Cambridge University Press, 1968. * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Hellenistic-Era Warships Galleys Military history of the Mediterranean

Warships

A warship or combatant ship is a naval ship that is built and primarily intended for naval warfare. Usually they belong to the armed forces of a state. As well as being armed, warships are designed to withstand damage and are usually faster an ...

Navy of ancient Rome

Warships

Naval warfare of antiquity