Hanging gardens on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Hanging Gardens of Babylon were one of the

The Hanging Gardens of Babylon were one of the

It is unclear whether the Hanging Gardens were an actual construction or a poetic creation, owing to the lack of documentation in contemporaneous Babylonian sources. There is also no mention of Nebuchadnezzar's wife Amyitis (or any other wives), although a political marriage to a Median or Persian would not have been unusual. Many records exist of Nebuchadnezzar's works, yet his long and complete inscriptions do not mention any garden. However, the gardens were said to still exist at the time that later writers described them, and some of these accounts are regarded as deriving from people who had visited Babylon.

It is unclear whether the Hanging Gardens were an actual construction or a poetic creation, owing to the lack of documentation in contemporaneous Babylonian sources. There is also no mention of Nebuchadnezzar's wife Amyitis (or any other wives), although a political marriage to a Median or Persian would not have been unusual. Many records exist of Nebuchadnezzar's works, yet his long and complete inscriptions do not mention any garden. However, the gardens were said to still exist at the time that later writers described them, and some of these accounts are regarded as deriving from people who had visited Babylon.

Of Sennacherib's palace, he mentions the massive

Of Sennacherib's palace, he mentions the massive

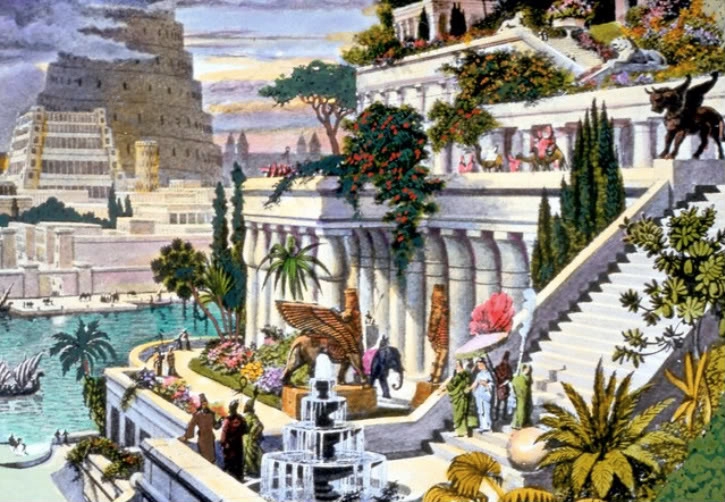

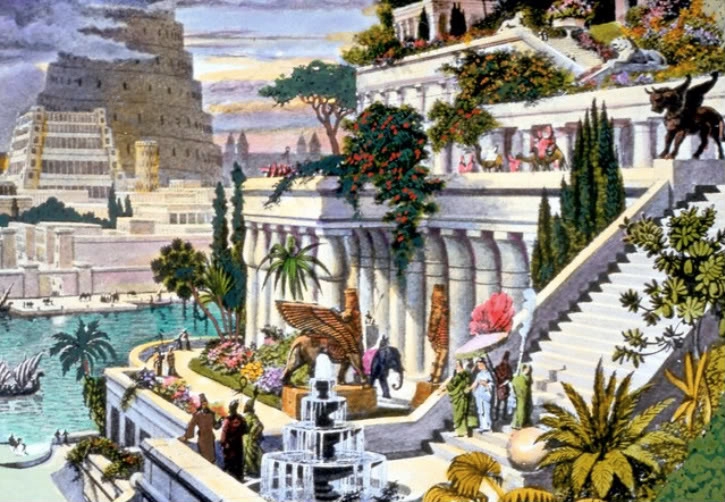

The gardens, as depicted in artworks, featured blossoming flowers, ripe fruit, burbling waterfalls and terraces exuberant with rich foliage. Based on Babylonian literature, tradition, and the environmental characteristics of the area, some of the following plants may have been found in the gardens:

*

The gardens, as depicted in artworks, featured blossoming flowers, ripe fruit, burbling waterfalls and terraces exuberant with rich foliage. Based on Babylonian literature, tradition, and the environmental characteristics of the area, some of the following plants may have been found in the gardens:

*

How the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World Work: The Hanging Gardens of Babylon

Plants in the Hanging Gardens of Babylon

Artistic Renditions of the Hanging Gardens and the city of Babylon

The Lost Gardens of Babylon

Documentary produced by the

3D model of the hanging-gardens-babylon - The Only Progress is Human

{{DEFAULTSORT:Hanging Gardens Of Babylon Babylon Babylonian art and architecture Buildings and structures demolished in the 1st century Gardens in Iraq Hanging gardens Garden design history Nebuchadnezzar II Sennacherib Seven Wonders of the Ancient World Terraced gardens Former buildings and structures in Iraq Lost buildings and structures Semiramis

The Hanging Gardens of Babylon were one of the

The Hanging Gardens of Babylon were one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World

The Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, also known as the Seven Wonders of the World or simply the Seven Wonders, is a list of seven notable structures present during classical antiquity. The first known list of seven wonders dates back to the 2 ...

listed by Hellenic culture. They were described as a remarkable feat of engineering with an ascending series of tiered gardens containing a wide variety of trees, shrubs, and vines, resembling a large green mountain constructed of mud bricks. It was said to have been built in the ancient city of Babylon

''Bābili(m)''

* sux, 𒆍𒀭𒊏𒆠

* arc, 𐡁𐡁𐡋 ''Bāḇel''

* syc, ܒܒܠ ''Bāḇel''

* grc-gre, Βαβυλών ''Babylṓn''

* he, בָּבֶל ''Bāvel''

* peo, 𐎲𐎠𐎲𐎡𐎽𐎢 ''Bābiru''

* elx, 𒀸𒁀𒉿𒇷 ''Babi ...

, near present-day Hillah

Hillah ( ar, ٱلْحِلَّة ''al-Ḥillah''), also spelled Hilla, is a city in central Iraq on the Hilla branch of the Euphrates River, south of Baghdad. The population is estimated at 364,700 in 1998. It is the capital of Babylon Province a ...

, Babil

''Bābili(m)''

* sux, 𒆍𒀭𒊏𒆠

* arc, 𐡁𐡁𐡋 ''Bāḇel''

* syc, ܒܒܠ ''Bāḇel''

* grc-gre, Βαβυλών ''Babylṓn''

* he, בָּבֶל ''Bāvel''

* peo, 𐎲𐎠𐎲𐎡𐎽𐎢 ''Bābiru''

* elx, 𒀸𒁀𒉿𒇷 ''Babi ...

province, in Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq ...

. The Hanging Gardens' name is derived from the Greek word (, ), which has a broader meaning than the modern English word "hanging" and refers to trees being planted on a raised structure such as a terrace

Terrace may refer to:

Landforms and construction

* Fluvial terrace, a natural, flat surface that borders and lies above the floodplain of a stream or river

* Terrace, a street suffix

* Terrace, the portion of a lot between the public sidewalk a ...

.

According to one legend, the Hanging Gardens were built alongside a grand palace known as ''The Marvel of Mankind'', by the Neo-Babylonian

The Neo-Babylonian Empire or Second Babylonian Empire, historically known as the Chaldean Empire, was the last polity ruled by monarchs native to Mesopotamia. Beginning with the coronation of Nabopolassar as the King of Babylon in 626 BC and bein ...

King Nebuchadnezzar II

Nebuchadnezzar II (Babylonian cuneiform: ''Nabû-kudurri-uṣur'', meaning "Nabu, watch over my heir"; Biblical Hebrew: ''Nəḇūḵaḏneʾṣṣar''), also spelled Nebuchadrezzar II, was the second king of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, ruling ...

(who ruled between 605 and 562 BC), for his Median

In statistics and probability theory, the median is the value separating the higher half from the lower half of a data sample, a population, or a probability distribution. For a data set, it may be thought of as "the middle" value. The basic fe ...

wife, Queen Amytis, because she missed the green hills and valleys of her homeland. This was attested to by the Babylonian priest Berossus

Berossus () or Berosus (; grc, Βηρωσσος, Bērōssos; possibly derived from akk, , romanized: , " Bel is his shepherd") was a Hellenistic-era Babylonian writer, a priest of Bel Marduk and astronomer who wrote in the Koine Greek langu ...

, writing in about 290 BC, a description that was later quoted by Josephus

Flavius Josephus (; grc-gre, Ἰώσηπος, ; 37 – 100) was a first-century Romano-Jewish historian and military leader, best known for ''The Jewish War'', who was born in Jerusalem—then part of Roman Judea—to a father of priestly d ...

. The construction of the Hanging Gardens has also been attributed to the legendary queen Semiramis

''Samīrāmīs'', hy, Շամիրամ ''Šamiram'') was the semi-legendary Lydian- Babylonian wife of Onnes and Ninus, who succeeded the latter to the throne of Assyria, according to Movses Khorenatsi. Legends narrated by Diodorus Siculus, who dre ...

and they have been called the ''Hanging Gardens of Semiramis'' as an alternative name.

The Hanging Gardens are the only one of the Seven Wonders for which the location has not been definitively established. There are no extant Babylonian texts that mention the gardens, and no definitive archaeological evidence has been found in Babylon. Three theories have been suggested to account for this: firstly, that they were purely mythical, and the descriptions found in ancient Greek and Roman writings (including those of Strabo

Strabo''Strabo'' (meaning "squinty", as in strabismus) was a term employed by the Romans for anyone whose eyes were distorted or deformed. The father of Pompey was called "Pompeius Strabo". A native of Sicily so clear-sighted that he could see ...

, Diodorus Siculus

Diodorus Siculus, or Diodorus of Sicily ( grc-gre, Διόδωρος ; 1st century BC), was an ancient Greek historian. He is known for writing the monumental universal history ''Bibliotheca historica'', in forty books, fifteen of which su ...

and Quintus Curtius Rufus

Quintus Curtius Rufus () was a Roman historian, probably of the 1st century, author of his only known and only surviving work, ''Historiae Alexandri Magni'', "Histories of Alexander the Great", or more fully ''Historiarum Alexandri Magni Macedon ...

) represented a romantic ideal of an eastern garden; secondly, that they existed in Babylon, but were destroyed sometime around the first century AD; and thirdly, that the legend refers to a well-documented garden that the Assyria

Assyria (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , romanized: ''māt Aššur''; syc, ܐܬܘܪ, ʾāthor) was a major ancient Mesopotamian civilization which existed as a city-state at times controlling regional territories in the indigenous lands of the A ...

n King Sennacherib

Sennacherib (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: or , meaning " Sîn has replaced the brothers") was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from the death of his father Sargon II in 705BC to his own death in 681BC. The second king of the Sargonid dynast ...

(704–681 BC) built in his capital city of Nineveh

Nineveh (; akk, ; Biblical Hebrew: '; ar, نَيْنَوَىٰ '; syr, ܢܝܼܢܘܹܐ, Nīnwē) was an ancient Assyrian city of Upper Mesopotamia, located in the modern-day city of Mosul in northern Iraq. It is located on the eastern ban ...

on the River Tigris

The Tigris () is the easternmost of the two great rivers that define Mesopotamia, the other being the Euphrates. The river flows south from the mountains of the Armenian Highlands through the Syrian and Arabian Deserts, and empties into the ...

, near the modern city of Mosul

Mosul ( ar, الموصل, al-Mawṣil, ku, مووسڵ, translit=Mûsil, Turkish: ''Musul'', syr, ܡܘܨܠ, Māwṣil) is a major city in northern Iraq, serving as the capital of Nineveh Governorate. The city is considered the second large ...

.

Descriptions in classical literature

There are five principal writers whose descriptions of Babylon exist in some form today. These writers concern themselves with the size of the Hanging Gardens, their overall design and means ofirrigation

Irrigation (also referred to as watering) is the practice of applying controlled amounts of water to land to help grow Crop, crops, Landscape plant, landscape plants, and Lawn, lawns. Irrigation has been a key aspect of agriculture for over 5,00 ...

, and why they were built.

Josephus

Flavius Josephus (; grc-gre, Ἰώσηπος, ; 37 – 100) was a first-century Romano-Jewish historian and military leader, best known for ''The Jewish War'', who was born in Jerusalem—then part of Roman Judea—to a father of priestly d ...

() quotes a description of the gardens by Berossus

Berossus () or Berosus (; grc, Βηρωσσος, Bērōssos; possibly derived from akk, , romanized: , " Bel is his shepherd") was a Hellenistic-era Babylonian writer, a priest of Bel Marduk and astronomer who wrote in the Koine Greek langu ...

, a Babylonian priest of Marduk

Marduk (Cuneiform: dAMAR.UTU; Sumerian: ''amar utu.k'' "calf of the sun; solar calf"; ) was a god from ancient Mesopotamia and patron deity of the city of Babylon. When Babylon became the political center of the Euphrates valley in the time of ...

,Finkel (1988) p. 41. whose writing is the earliest known mention of the gardens. Berossus described the reign of Nebuchadnezzar II and is the only source to credit that king with the construction of the Hanging Gardens.

Diodorus Siculus

Diodorus Siculus, or Diodorus of Sicily ( grc-gre, Διόδωρος ; 1st century BC), was an ancient Greek historian. He is known for writing the monumental universal history ''Bibliotheca historica'', in forty books, fifteen of which su ...

(active ) seems to have consulted the 4th century BC texts of both Cleitarchus

Cleitarchus or Clitarchus ( el, Κλείταρχος) was one of the historians of Alexander the Great. Son of the historian Dinon of Colophon, he spent a considerable time at the court of Ptolemy Lagus. He was active in the mid to late 4th centu ...

(a historian of Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, wikt:Ἀλέξανδρος, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Maced ...

) and Ctesias of Cnidus

Ctesias (; grc-gre, Κτησίας; fl. fifth century BC), also known as Ctesias of Cnidus, was a Greek physician and historian from the town of Cnidus in Caria, then part of the Achaemenid Empire.

Historical events

Ctesias, who lived in the fi ...

. Diodorus ascribes the construction to a Syrian

Syrians ( ar, سُورِيُّون, ''Sūriyyīn'') are an Eastern Mediterranean ethnic group indigenous to the Levant. They share common Levantine Semitic roots. The cultural and linguistic heritage of the Syrian people is a blend of both indi ...

king. He states that the garden was in the shape of a square, with each side approximately four plethra

Plethron ( grc-gre, , plural ''plethra'') is an ancient unit of Greek measurement equal to 97 to 100 Greek feet (ποῦς, ''pous''; c. 30 meters), although the measures for plethra may have varied from polis to polis. This was roughly the widt ...

long. The garden was tiered, with the uppermost gallery being 50 cubit

The cubit is an ancient unit of length based on the distance from the elbow to the tip of the middle finger. It was primarily associated with the Sumerians, Egyptians, and Israelites. The term ''cubit'' is found in the Bible regarding No ...

s high. The walls, 22 feet thick, were made of brick. The bases of the tiered sections were sufficiently deep to provide root growth for the largest trees, and the gardens were irrigated from the nearby Euphrates

The Euphrates () is the longest and one of the most historically important rivers of Western Asia. Tigris–Euphrates river system, Together with the Tigris, it is one of the two defining rivers of Mesopotamia ( ''the land between the rivers'') ...

.

Quintus Curtius Rufus

Quintus Curtius Rufus () was a Roman historian, probably of the 1st century, author of his only known and only surviving work, ''Historiae Alexandri Magni'', "Histories of Alexander the Great", or more fully ''Historiarum Alexandri Magni Macedon ...

(fl. 1st century AD) probably drew on the same sources as Diodorus. He states that the gardens were located on top of a citadel

A citadel is the core fortified area of a town or city. It may be a castle, fortress, or fortified center. The term is a diminutive of "city", meaning "little city", because it is a smaller part of the city of which it is the defensive core.

In ...

, which was 20 stadia

Stadia may refer to:

* One of the plurals of stadium, along with "stadiums"

* The plural of stadion, an ancient Greek unit of distance, which equals to 600 Greek feet (''podes'').

* Stadia (Caria), a town of ancient Caria, now in Turkey

* Stadi ...

in circumference. He attributes the building of the gardens to a Syrian king, again for the reason that his queen missed her homeland.

The account of Strabo

Strabo''Strabo'' (meaning "squinty", as in strabismus) was a term employed by the Romans for anyone whose eyes were distorted or deformed. The father of Pompey was called "Pompeius Strabo". A native of Sicily so clear-sighted that he could see ...

() possibly based his description on the lost account of Onesicritus

Onesicritus ( el, Ὀνησίκριτος; c. 360 BC – c. 290 BC), a Greek historical writer and Cynic philosopher, who accompanied Alexander the Great on his campaigns in Asia. He claimed to have been the commander of Alexander's fleet but w ...

from the 4th century BC. He states that the gardens were watered by means of an Archimedes' screw

The Archimedes screw, also known as the Archimedean screw, hydrodynamic screw, water screw or Egyptian screw, is one of the earliest hydraulic machines. Using Archimedes screws as water pumps (Archimedes screw pump (ASP) or screw pump) dates back ...

leading to the gardens from the Euphrates river.

The last of the classical sources thought to be independent of the others is ''A Handbook to the Seven Wonders of the World'' by the paradoxographer Philo of Byzantium, writing in the 4th to 5th century AD. The method of raising water by screw matches that described by Strabo. Philo praises the engineering and ingenuity of building vast areas of deep soil, which had a tremendous mass, so far above the natural grade of the surrounding land, as well as the irrigation techniques.

Historical existence

It is unclear whether the Hanging Gardens were an actual construction or a poetic creation, owing to the lack of documentation in contemporaneous Babylonian sources. There is also no mention of Nebuchadnezzar's wife Amyitis (or any other wives), although a political marriage to a Median or Persian would not have been unusual. Many records exist of Nebuchadnezzar's works, yet his long and complete inscriptions do not mention any garden. However, the gardens were said to still exist at the time that later writers described them, and some of these accounts are regarded as deriving from people who had visited Babylon.

It is unclear whether the Hanging Gardens were an actual construction or a poetic creation, owing to the lack of documentation in contemporaneous Babylonian sources. There is also no mention of Nebuchadnezzar's wife Amyitis (or any other wives), although a political marriage to a Median or Persian would not have been unusual. Many records exist of Nebuchadnezzar's works, yet his long and complete inscriptions do not mention any garden. However, the gardens were said to still exist at the time that later writers described them, and some of these accounts are regarded as deriving from people who had visited Babylon. Herodotus

Herodotus ( ; grc, , }; BC) was an ancient Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus, part of the Persian Empire (now Bodrum, Turkey) and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria ( Italy). He is known f ...

, who describes Babylon in his '' Histories'', does not mention the Hanging Gardens, although it could be that the gardens were not yet well known to the Greeks at the time of his visit.

To date, no archaeological evidence has been found at Babylon for the Hanging Gardens. It is possible that evidence exists beneath the Euphrates, which cannot be excavated safely at present. The river flowed east of its current position during the time of Nebuchadnezzar II, and little is known about the western portion of Babylon. Rollinger has suggested that Berossus attributed the Gardens to Nebuchadnezzar for political reasons, and that he had adopted the legend from elsewhere.

Identification with Sennacherib's gardens at Nineveh

Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

scholar Stephanie Dalley

Stephanie Mary Dalley FSA (''née'' Page; March 1943) is a British Assyriologist and scholar of the Ancient Near East. She has retired as a teaching Fellow from the Oriental Institute, Oxford. She is known for her publications of cuneiform te ...

has proposed that the Hanging Gardens of Babylon were actually the well-documented gardens constructed by the Assyria

Assyria (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , romanized: ''māt Aššur''; syc, ܐܬܘܪ, ʾāthor) was a major ancient Mesopotamian civilization which existed as a city-state at times controlling regional territories in the indigenous lands of the A ...

n king Sennacherib

Sennacherib (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: or , meaning " Sîn has replaced the brothers") was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from the death of his father Sargon II in 705BC to his own death in 681BC. The second king of the Sargonid dynast ...

(reigned 704 – 681 BC) for his palace at Nineveh

Nineveh (; akk, ; Biblical Hebrew: '; ar, نَيْنَوَىٰ '; syr, ܢܝܼܢܘܹܐ, Nīnwē) was an ancient Assyrian city of Upper Mesopotamia, located in the modern-day city of Mosul in northern Iraq. It is located on the eastern ban ...

; Dalley posits that during the intervening centuries the two sites became confused, and the extensive gardens at Sennacherib's palace were attributed to Nebuchadnezzar II's Babylon. Archaeological excavations have found traces of a vast system of aqueducts attributed to Sennacherib by an inscription on its remains, which Dalley proposes were part of an series of canals, dams, and aqueducts used to carry water to Nineveh with water-raising screws used to raise it to the upper levels of the gardens.

Dalley bases her arguments on recent developments in the analysis of contemporary Akkadian Akkadian or Accadian may refer to:

* Akkadians, inhabitants of the Akkadian Empire

* Akkadian language, an extinct Eastern Semitic language

* Akkadian literature, literature in this language

* Akkadian cuneiform

Cuneiform is a logo- syllabi ...

inscriptions. Her main points are:

* The name ''Babylon'', meaning "Gate of the Gods", was the name given to several Mesopotamian

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the F ...

cities. Sennacherib renamed the city gates of Nineveh

Nineveh (; akk, ; Biblical Hebrew: '; ar, نَيْنَوَىٰ '; syr, ܢܝܼܢܘܹܐ, Nīnwē) was an ancient Assyrian city of Upper Mesopotamia, located in the modern-day city of Mosul in northern Iraq. It is located on the eastern ban ...

after gods, which suggests that he wished his city to be considered "a Babylon".

* Only Josephus names Nebuchadnezzar as the king who built the gardens; although Nebuchadnezzar left many inscriptions, none mentions any garden or engineering works. Diodorus Siculus

Diodorus Siculus, or Diodorus of Sicily ( grc-gre, Διόδωρος ; 1st century BC), was an ancient Greek historian. He is known for writing the monumental universal history ''Bibliotheca historica'', in forty books, fifteen of which su ...

and Quintus Curtius Rufus

Quintus Curtius Rufus () was a Roman historian, probably of the 1st century, author of his only known and only surviving work, ''Historiae Alexandri Magni'', "Histories of Alexander the Great", or more fully ''Historiarum Alexandri Magni Macedon ...

specify a "Syrian" king. By contrast, Sennacherib left written descriptions, and there is archaeological evidence of his water engineering. His grandson Assurbanipal

Ashurbanipal (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , meaning " Ashur is the creator of the heir") was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 669 BCE to his death in 631. He is generally remembered as the last great king of Assyria. Inheriting the throne as ...

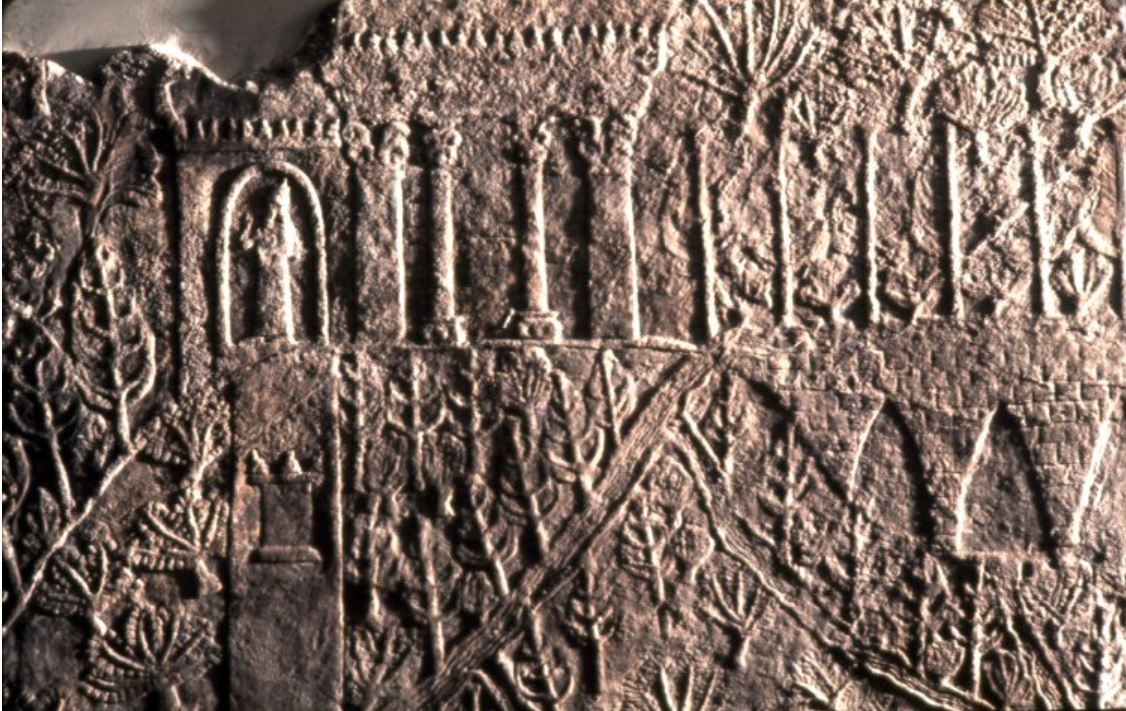

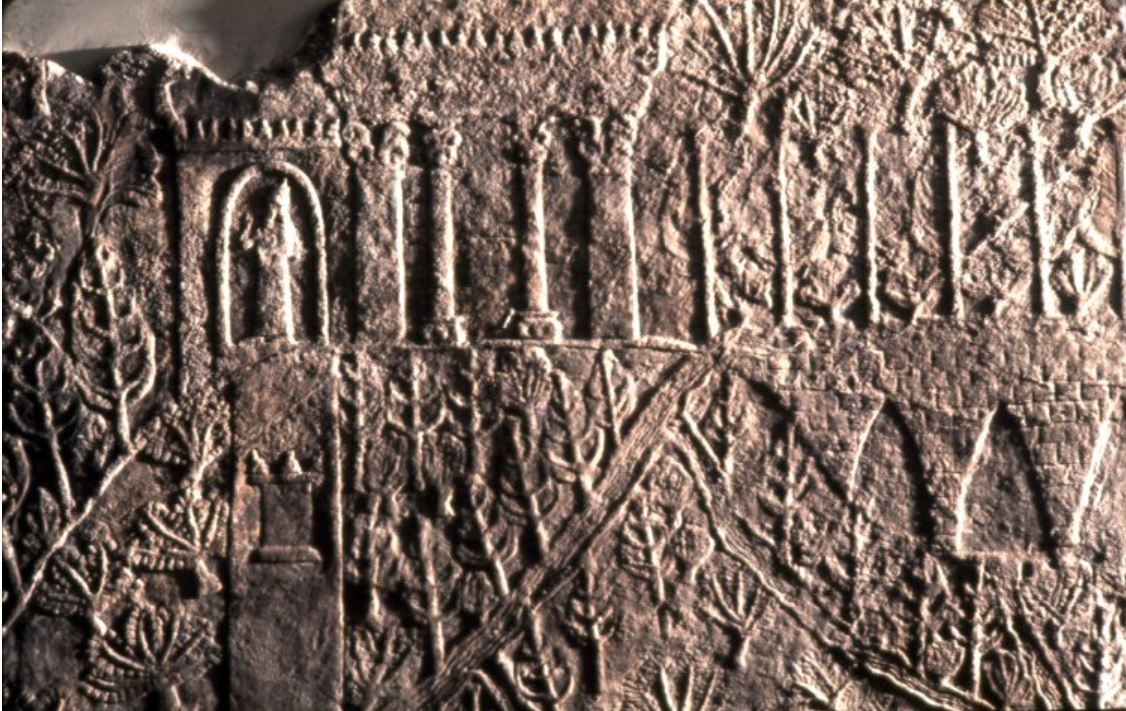

pictured the mature garden on a sculptured wall panel in his palace.

* Sennacherib called his new palace and garden "a wonder for all peoples". He describes the making and operation of screws to raise water in his garden.

* The descriptions of the classical authors fit closely to these contemporary records. Before the Battle of Gaugamela

The Battle of Gaugamela (; grc, Γαυγάμηλα, translit=Gaugámela), also called the Battle of Arbela ( grc, Ἄρβηλα, translit=Árbela), took place in 331 BC between the forces of the Army of Macedon under Alexander the Great a ...

in 331 BC Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, wikt:Ἀλέξανδρος, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Maced ...

camped for four days near the aqueduct at Jerwan

Jerwan is a locality north of Mosul in the Nineveh Province of Iraq. The site is clear of vegetation and is sparsely settled.

The site is famous for the ruins of an enormous aqueduct crossing the Khenis River, constructed of more than two mill ...

. The historians who travelled with him would have had ample time to investigate the enormous works around them, recording them in Greek. These first-hand accounts have not survived into modern times, but were quoted by later Greek writers.

King Sennacherib's garden was well-known not just for its beautya year-round oasis of lush green in a dusty summer landscapebut also for the marvelous feats of water engineering that maintained the garden. The quotations in this section are the translations of the author and are reproduced with the permission of OUP. There was a tradition of Assyrian royal garden building. King Ashurnasirpal II

Ashur-nasir-pal II (transliteration: ''Aššur-nāṣir-apli'', meaning " Ashur is guardian of the heir") was king of Assyria from 883 to 859 BC.

Ashurnasirpal II succeeded his father, Tukulti-Ninurta II, in 883 BC. During his reign he embarked ...

(883–859 BC) had created a canal, which cut through the mountains. Fruit tree orchards were planted. Also mentioned were pines, cypresses and junipers; almond trees, date trees, ebony, rosewood, olive, oak, tamarisk, walnut, terebinth, ash, fir, pomegranate, pear, quince, fig, and grapes. A sculptured wall panel of Assurbanipal shows the garden in its maturity. One original panel and the drawing of another are held by the British Museum

The British Museum is a public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is among the largest and most comprehensive in existence. It docum ...

, although neither is on public display. Several features mentioned by the classical authors are discernible on these contemporary images.

Of Sennacherib's palace, he mentions the massive

Of Sennacherib's palace, he mentions the massive limestone block

Limestone ( calcium carbonate ) is a type of carbonate sedimentary rock which is the main source of the material lime. It is composed mostly of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different crystal forms of . Limestone forms when t ...

s that reinforce the flood defences. Parts of the palace were excavated by Austin Henry Layard

Sir Austen Henry Layard (; 5 March 18175 July 1894) was an English Assyriologist, traveller, cuneiformist, art historian, draughtsman, collector, politician and diplomat. He was born to a mostly English family in Paris and largely raised in It ...

in the mid-19th century. His citadel plan shows contours which would be consistent with Sennacherib's garden, but its position has not been confirmed. The area has been used as a military base in recent times, making it difficult to investigate further.

The irrigation of such a garden demanded an upgraded water supply to the city of Nineveh. The canals stretched over into the mountains. Sennacherib was proud of the technologies he had employed and describes them in some detail on his inscriptions. At the headwater of Bavian (Khinnis

Khinnis is an Assyrian people, Assyrian archaeological site, also known as Bavian, its neighbouring village) in Dohuk Governorate, Duhok Governorate in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq. It is notable for its rock reliefs, built by king Sennacherib ar ...

) his inscription mentions automatic sluice gates. An enormous aqueduct crossing the valley at Jerwan

Jerwan is a locality north of Mosul in the Nineveh Province of Iraq. The site is clear of vegetation and is sparsely settled.

The site is famous for the ruins of an enormous aqueduct crossing the Khenis River, constructed of more than two mill ...

was constructed of over two million dressed stones. It used stone arches

An arch is a vertical curved structure that spans an elevated space and may or may not support the weight above it, or in case of a horizontal arch like an arch dam, the hydrostatic pressure against it.

Arches may be synonymous with vault ...

and waterproof cement. On it is written:

Sennacherib claimed that he had built a "Wonder for all Peoples", and said he was the first to deploy a new casting technique in place of the "lost-wax" process for his monumental (30 tonne) bronze castings. He was able to bring the water into his garden at a high level because it was sourced from further up in the mountains, and he then raised the water even higher by deploying his new water screws. This meant he could build a garden that towered above the landscape with large trees on the top of the terracesa stunning artistic effect that surpassed those of his predecessors.

Plants

The gardens, as depicted in artworks, featured blossoming flowers, ripe fruit, burbling waterfalls and terraces exuberant with rich foliage. Based on Babylonian literature, tradition, and the environmental characteristics of the area, some of the following plants may have been found in the gardens:

*

The gardens, as depicted in artworks, featured blossoming flowers, ripe fruit, burbling waterfalls and terraces exuberant with rich foliage. Based on Babylonian literature, tradition, and the environmental characteristics of the area, some of the following plants may have been found in the gardens:

*Olive

The olive, botanical name ''Olea europaea'', meaning 'European olive' in Latin, is a species of small tree or shrub in the family Oleaceae, found traditionally in the Mediterranean Basin. When in shrub form, it is known as ''Olea europaea'' ...

(''Olea europaea'')

*Quince

The quince (; ''Cydonia oblonga'') is the sole member of the genus ''Cydonia'' in the Malinae subtribe (which also contains apples and pears, among other fruits) of the Rosaceae family (biology), family. It is a deciduous tree that bears hard ...

(''Cydonia oblonga'')

*Common pear

''Pyrus communis'', the common pear, is a species of pear native to central and eastern Europe, and western Asia.

It is one of the most important fruits of temperate regions, being the species from which most orchard pear cultivars grown in Euro ...

(''Pyrus communis'')

*Fig

The fig is the edible fruit of ''Ficus carica'', a species of small tree in the flowering plant family Moraceae. Native to the Mediterranean and western Asia, it has been cultivated since ancient times and is now widely grown throughout the world ...

(''Ficus carica'')

*Almond

The almond (''Prunus amygdalus'', syn. ''Prunus dulcis'') is a species of tree native to Iran and surrounding countries, including the Levant. The almond is also the name of the edible and widely cultivated seed of this tree. Within the genus ...

(''Prunus dulcis'')

* Common grape vine (''Vitis vinifera'')

*Date palm

''Phoenix dactylifera'', commonly known as date or date palm, is a flowering plant species in the palm family, Arecaceae, cultivated for its edible sweet fruit called dates. The species is widely cultivated across northern Africa, the Middle Eas ...

(''Phoenix dactylifera'')

* Athel tamarisk (''Tamarix aphylla'')

* Mt. Atlas mastic tree (''Pistacia atlantica'')

Imported

An import is the receiving country in an export from the sending country. Importation and exportation are the defining financial transactions of international trade.

In international trade, the importation and exportation of goods are limited ...

plant varieties that may have been present in the gardens include the cedar

Cedar may refer to:

Trees and plants

*''Cedrus'', common English name cedar, an Old-World genus of coniferous trees in the plant family Pinaceae

*Cedar (plant), a list of trees and plants known as cedar

Places United States

* Cedar, Arizona

* ...

, cypress

Cypress is a common name for various coniferous trees or shrubs of northern temperate regions that belong to the family Cupressaceae. The word ''cypress'' is derived from Old French ''cipres'', which was imported from Latin ''cypressus'', the ...

, ebony

Ebony is a dense black/brown hardwood, coming from several species in the genus ''Diospyros'', which also contains the persimmons. Unlike most woods, ebony is dense enough to sink in water. It is finely textured and has a mirror finish when pol ...

, pomegranate

The pomegranate (''Punica granatum'') is a fruit-bearing deciduous shrub in the family Lythraceae, subfamily Punicoideae, that grows between tall.

The pomegranate was originally described throughout the Mediterranean Basin, Mediterranean re ...

, plum

A plum is a fruit of some species in ''Prunus'' subg. ''Prunus'.'' Dried plums are called prunes.

History

Plums may have been one of the first fruits domesticated by humans. Three of the most abundantly cultivated species are not found i ...

, rosewood

Rosewood refers to any of a number of richly hued timbers, often brownish with darker veining, but found in many different hues.

True rosewoods

All genuine rosewoods belong to the genus ''Dalbergia''. The pre-eminent rosewood appreciated in ...

, terebinth

''Pistacia terebinthus'' also called the terebinth and the turpentine tree, is a deciduous tree species of the genus ''Pistacia'', native to the Mediterranean region from the western regions of Morocco and Portugal to Greece and western and s ...

, juniper

Junipers are coniferous trees and shrubs in the genus ''Juniperus'' () of the cypress family Cupressaceae. Depending on the taxonomy, between 50 and 67 species of junipers are widely distributed throughout the Northern Hemisphere, from the Arcti ...

, oak

An oak is a tree or shrub in the genus ''Quercus'' (; Latin "oak tree") of the beech family, Fagaceae. There are approximately 500 extant species of oaks. The common name "oak" also appears in the names of species in related genera, notably ''L ...

, ash tree

''Fraxinus'' (), commonly called ash, is a genus of flowering plants in the olive and lilac family, Oleaceae. It contains 45–65 species of usually medium to large trees, mostly deciduous, though a number of subtropical species are evergree ...

, fir, myrrh

Myrrh (; from Semitic, but see '' § Etymology'') is a gum-resin extracted from a number of small, thorny tree species of the genus ''Commiphora''. Myrrh resin has been used throughout history as a perfume, incense and medicine. Myrrh mi ...

, walnut

A walnut is the edible seed of a drupe of any tree of the genus ''Juglans'' (family Juglandaceae), particularly the Persian or English walnut, '' Juglans regia''.

Although culinarily considered a "nut" and used as such, it is not a true ...

, and willow

Willows, also called sallows and osiers, from the genus ''Salix'', comprise around 400 speciesMabberley, D.J. 1997. The Plant Book, Cambridge University Press #2: Cambridge. of typically deciduous trees and shrubs, found primarily on moist s ...

. Some of these plants were suspended over the terraces and draped over its walls with arches underneath.

See also

*Folkewall

The Folkewall is a construction with the dual functions of growing plants and purifying greywater. It was designed by Folke Günther in Sweden.

Inspired by the "Sanitas wall" at Dr Gösta Nilsson's Sanitas farm project in Botswana, this technique ...

* Green wall

* Green roof

A green roof or living roof is a roof of a building that is partially or completely covered with vegetation and a growing medium, planted over a waterproofing membrane. It may also include additional layers such as a root barrier and drainage ...

* Historical hydroculture

This is a history of notable hydroculture phenomena. Ancient hydroculture proposed sites and modern revolutionary works are mentioned. Included in this history are all forms of aquatic and semi-aquatic based horticulture that focus on flora: aquat ...

* History of gardening

The early history of gardening is largely entangled with the history of agriculture, with gardens that were mainly ornamental generally the preserve of the elite until quite recent times. Smaller gardens generally had being a kitchen garden as th ...

References

Sources

* * *Further reading

* Dalley, Stephanie. 1994. "Nineveh, Babylon and the Hanging Gardens: Cuneiform and Classical Sources Reconciled." ''Iraq'' 56: 45–58. . * Norwich, John Julius. 2009. ''The Great Cities In History''. London: Thames & Hudson. * Reade, Julian. 2000. "Alexander the Great and the Hanging Gardens of Babylon." ''Iraq'' 62: 195–217. .External links

How the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World Work: The Hanging Gardens of Babylon

Plants in the Hanging Gardens of Babylon

Artistic Renditions of the Hanging Gardens and the city of Babylon

The Lost Gardens of Babylon

Documentary produced by the

PBS

The Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) is an American public broadcasting, public broadcaster and Non-commercial activity, non-commercial, Terrestrial television, free-to-air television network based in Arlington, Virginia. PBS is a publicly fu ...

Series Secrets of the Dead

''Secrets of the Dead'', produced by WNET 13 New York, is an ongoing PBS television series which began in 2000. The show generally follows an investigator or team of investigators exploring what modern science can tell us about some of the great m ...

3D model of the hanging-gardens-babylon - The Only Progress is Human

{{DEFAULTSORT:Hanging Gardens Of Babylon Babylon Babylonian art and architecture Buildings and structures demolished in the 1st century Gardens in Iraq Hanging gardens Garden design history Nebuchadnezzar II Sennacherib Seven Wonders of the Ancient World Terraced gardens Former buildings and structures in Iraq Lost buildings and structures Semiramis