Half-Breed (politics) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The "Half-Breeds" were a

The Senatorial Career of William P. Frye

p. 5–6. ''The University of Maine''. Retrieved February 3, 2022. a notion affirmed by the writings of Richard E. Welch Jr. In spite of the faction's broad advocacy of civil service reform in their decries of corruption, several members were known to have engaged in illicit practices for personal or partisan benefits. Congressman and Senator

During the

During the

Although the Half-Breeds had no rigid organization as a congressional bloc and were viewed as merely a group of disgruntled Blaine supporters promoting factionalism, their influence proved to be highly significant.Welch, Robert E. Jr. (1971)

Although the Half-Breeds had no rigid organization as a congressional bloc and were viewed as merely a group of disgruntled Blaine supporters promoting factionalism, their influence proved to be highly significant.Welch, Robert E. Jr. (1971)

George Frisbie Hoar and the Half-Breed Republicans

pp. 2–3. ''Harvard University Press''. They viewed the term attributed negatively to them as either badges of honor or an identifying mark, a parallel to the Democratic Party's embracing of the donkey as their symbol after

''United States Senate''. Retrieved February 12, 2022. expanding markets abroad, and a business-friendly currency system on the national level. According to Professor Richard E. Welch Jr., the Half-Breeds were "party regulars" who "damned" bolters, were not uniformly independent in political nature nor advocates of the spoils system, and more intelligent than personal in comparison to the Stalwarts.

James A. Garfield and Chester A. Arthur

''Encyclopedia.com''. Retrieved February 12, 2022. and opposed questionable policies pushed by President Hayes. He emerged as one of its main members largely due to sheer contempt for Stalwart

''United States Senate''. Retrieved February 12, 2022. attempting to draw support from upper-class old Southern Whigs who eventually joined the Democratic Party when the Whig Party collapsed.

''Rutherford B. Hayes Presidential Library & Museums''. Retrieved February 12, 2022. all but ensuring a Jim Crow Democrat takeover of the region. President Hayes also pushed for civil service reform,Conkling, Roscoe

''Encyclopedia.com''. Retrieved February 12, 2022. aligning himself with the Half-Breeds. Seeking to curb the powers of Conkling and the latter's powerful

''National Park Service''. Retrieved February 12, 2022. Hayes vainly attempted to wrest control of appointments to the position from the Conkling machine to no avail, twice failing to appoint a like-minded political figure due to the successful congressional blockade initiated by the Stalwarts. Soon afterwards, Conkling appointed close ally and future president Chester A. Arthur to the post of Collector. Arthur proved to be corrupt, giving away jobs only on the basis of party affiliation with no regard for competence and qualifications. Hayes then investigated the Customs House, and along with John Sherman (the

''University of Central Florida''. Retrieved February 12, 2022. Any remaining hopes of a party renomination for Hayes in the 1880 presidential election depended on support from potential Blaine supporters. With this needed bolstering evaporating, he faced no chance of becoming the Republican nominee for the race. The Blaine organization instead turned to advocate a nomination of their leader, Senator Blaine. During the Hayes years, Blaine frequently joined Stalwarts in voting against the president's nominees, including

Blaine was chosen as Garfield's Secretary of State, and carried heavy influence over the political appointments Garfield issued for congressional approval. After Garfield was assassinated by Charles J. Guiteau, a self-professed Stalwart, who proclaimed, "I am a Stalwart of the Stalwarts and Arthur will be President," the new Stalwart president Chester A. Arthur surprised those in his own faction by promoting civil service reform and issuing government jobs based on a merit system.

The Half-Breeds put through Congress the

Blaine was chosen as Garfield's Secretary of State, and carried heavy influence over the political appointments Garfield issued for congressional approval. After Garfield was assassinated by Charles J. Guiteau, a self-professed Stalwart, who proclaimed, "I am a Stalwart of the Stalwarts and Arthur will be President," the new Stalwart president Chester A. Arthur surprised those in his own faction by promoting civil service reform and issuing government jobs based on a merit system.

The Half-Breeds put through Congress the

The Republican National Convention ultimately nominated Half-Breed Blaine and former Stalwart John A. Logan of

The Republican National Convention ultimately nominated Half-Breed Blaine and former Stalwart John A. Logan of

''John A. Logan: Stalwart Republican from Illinois''

p. 186. Due to both Blaine and Logan having a record of favoring the spoils system over civil service reform, "reformers" in the

in JSTOR

Republican Party (United States) terminology * Civil service reform in the United States Assassination of James A. Garfield Factions in the Republican Party (United States) Classical liberalism Centrism in the United States

political faction

A political faction is a group of individuals that share a common political purpose but differs in some respect to the rest of the entity. A faction within a group or political party may include fragmented sub-factions, "parties within a party," ...

of the United States Republican Party

The Republican Party, also referred to as the GOP ("Grand Old Party"), is one of the Two-party system, two Major party, major contemporary political parties in the United States. The GOP was founded in 1854 by Abolitionism in the United Stat ...

in the late 19th century.

The Half-Breeds were a comparably moderate group, and were the opponents of the Stalwarts

The Stalwarts were a faction of the Republican Party that existed briefly in the United States during and after Reconstruction and the Gilded Age during the 1870s and 1880s. Led by U.S. Senator Roscoe Conkling—also known as "Lord Roscoe"— ...

, the other main faction of the Republican Party. The main issue that divided the Stalwarts and the Half-Breeds was political patronage

Patronage is the support, encouragement, privilege, or financial aid that an organization or individual bestows on another. In the history of art, arts patronage refers to the support that kings, popes, and the wealthy have provided to artists su ...

. The Stalwarts were in favor of political machine

In the politics of representative democracies, a political machine is a party organization that recruits its members by the use of tangible incentives (such as money or political jobs) and that is characterized by a high degree of leadership co ...

s and spoils system

In politics and government, a spoils system (also known as a patronage system) is a practice in which a political party, after winning an election, gives government jobs to its supporters, friends (cronyism), and relatives (nepotism) as a reward ...

-style patronage, while the Half-Breeds, later led by Maine

Maine () is a state in the New England and Northeastern regions of the United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick and Quebec to the northeast and nor ...

senator

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

James G. Blaine

James Gillespie Blaine (January 31, 1830January 27, 1893) was an American statesman and Republican politician who represented Maine in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1863 to 1876, serving as Speaker of the U.S. House of Representati ...

, were in favor of civil service

The civil service is a collective term for a sector of government composed mainly of career civil servants hired on professional merit rather than appointed or elected, whose institutional tenure typically survives transitions of political leaders ...

reform and a merit system The merit system is the process of promoting and hiring government employees based on their ability to perform a job, rather than on their political connections. It is the opposite of the spoils system.

History

The earliest known example of a me ...

. The epithet "Half-Breed" was invented in derision by the Stalwarts to denote those whom they perceived as being "only half Republican."

The Blaine faction in the context of the Hayes era is commonly attributed as the congressional Half-Breeds, although this is erroneous. Blaine's political organization during this time formed an informal coalition with the Stalwarts in opposition towards aspects of the Hayes administration,Banks, Ronald F. (June 1958)The Senatorial Career of William P. Frye

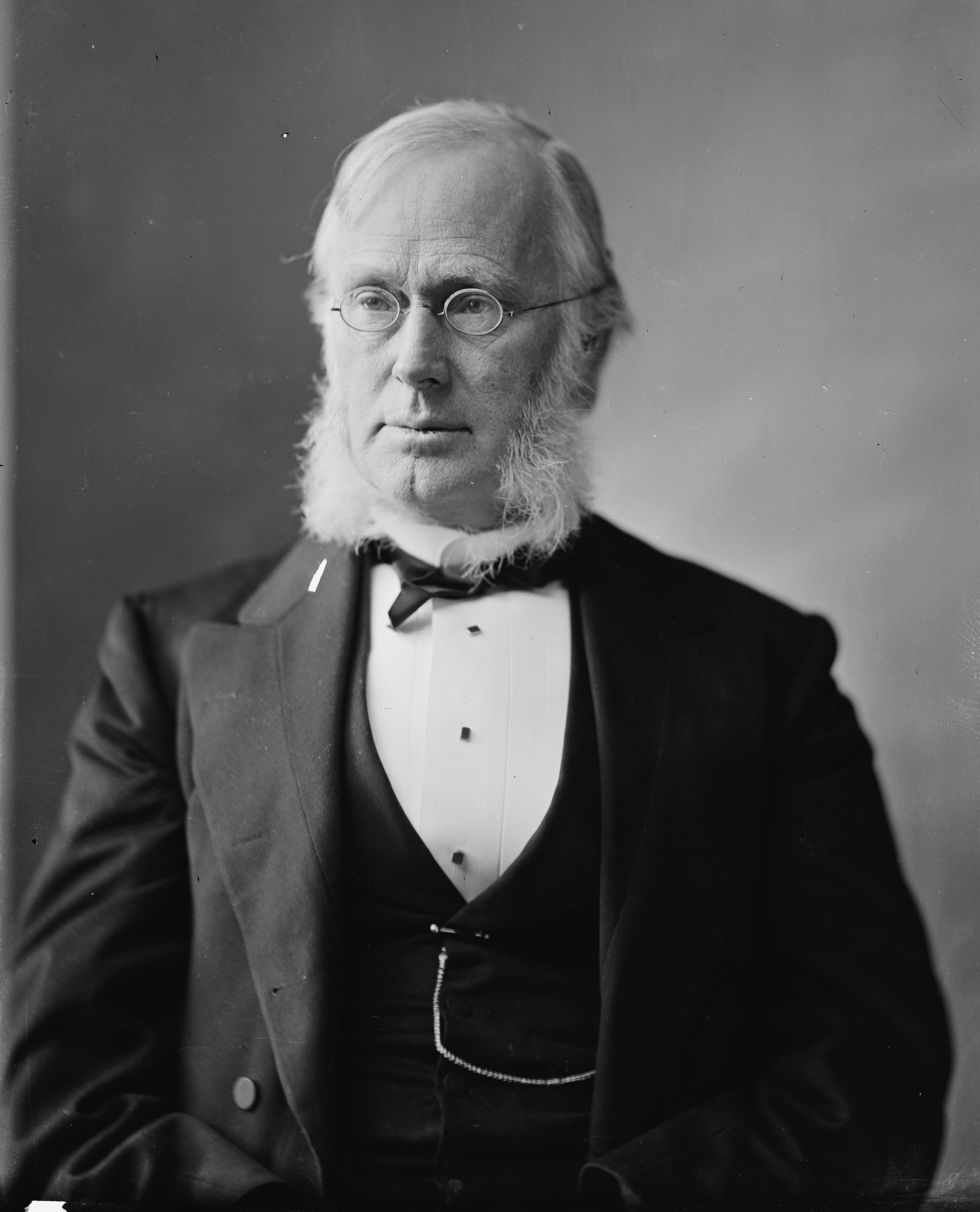

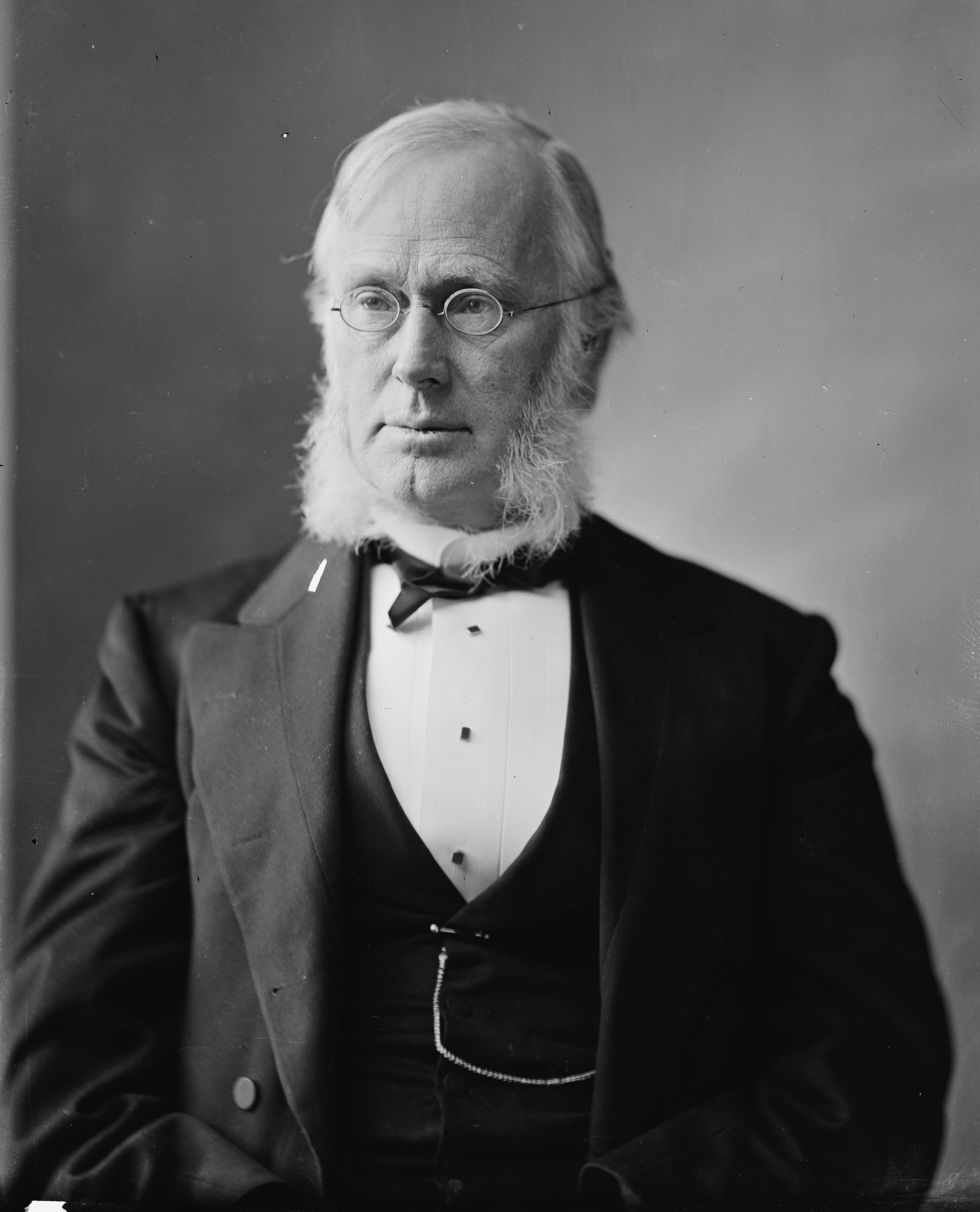

p. 5–6. ''The University of Maine''. Retrieved February 3, 2022. a notion affirmed by the writings of Richard E. Welch Jr. In spite of the faction's broad advocacy of civil service reform in their decries of corruption, several members were known to have engaged in illicit practices for personal or partisan benefits. Congressman and Senator

Henry L. Dawes

Henry Laurens Dawes (October 30, 1816February 5, 1903) was an attorney and politician, a Republican United States Senator and United States Representative from Massachusetts. He is notable for the Dawes Act (1887), which was intended to stimul ...

was revealed as a stockholder for Crédit Mobilier amidst the scandal

A scandal can be broadly defined as the strong social reactions of outrage, anger, or surprise, when accusations or rumours circulate or appear for some reason, regarding a person or persons who are perceived to have transgressed in some way. Th ...

; George F. Edmunds of Vermont was later suspected by Richard F. Pettigrew of being "distinctly dishonest" and a "senatorial bribe-taker."

Background

During the

During the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

, President Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation throu ...

's policies pertaining to the Union Army were criticized by Radical Republicans

The Radical Republicans (later also known as "Stalwarts") were a faction within the Republican Party, originating from the party's founding in 1854, some 6 years before the Civil War, until the Compromise of 1877, which effectively ended Recons ...

as too lenient against the South. This powerful GOP bloc which included Henry Winter Davis, Benjamin Wade

Benjamin Franklin "Bluff" Wade (October 27, 1800March 2, 1878) was an American lawyer and politician who served as a United States Senator for Ohio from 1851 to 1869. He is known for his leading role among the Radical Republicans.

, Thaddeus Stevens

Thaddeus Stevens (April 4, 1792August 11, 1868) was a member of the United States House of Representatives from Pennsylvania, one of the leaders of the Radical Republican faction of the Republican Party during the 1860s. A fierce opponent of sla ...

, and Charles Sumner

Charles Sumner (January 6, 1811March 11, 1874) was an American statesman and United States Senator from Massachusetts. As an academic lawyer and a powerful orator, Sumner was the leader of the anti-slavery forces in the state and a leader of th ...

continuously criticized Lincoln for failing to advance as efficiently as possible, and the president's more staunch supporters were the Moderate Republicans."Moderate" in this specific context refers to the degree of eagerness in war policy without regard to overall political ideology; Lincoln in this sense was "moderate" in terms of leading the Union during the Civil War even though he was quite conservative on other issues such as economics.

The "moderate" Republicans Lincoln led were at odds with the Radicals and favored more conciliatory Reconstruction policies. Their ranks would later be joined during the Johnson presidency by some former Radical Republicans who were "reformers," including Sumner, Carl Schurz

Carl Schurz (; March 2, 1829 – May 14, 1906) was a German revolutionary and an American statesman, journalist, and reformer. He immigrated to the United States after the German revolutions of 1848–1849 and became a prominent member of the new ...

, Horace Greeley

Horace Greeley (February 3, 1811 – November 29, 1872) was an American newspaper editor and publisher who was the founder and editor of the '' New-York Tribune''. Long active in politics, he served briefly as a congressman from New York ...

, and Lyman Trumbull

Lyman Trumbull (October 12, 1813 – June 25, 1896) was a lawyer, judge, and United States Senator from Illinois and the co-author of the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

Born in Colchester, Connecticut, Trumbull es ...

.

Republican congressman Thomas A. Jenckes

Thomas Allen Jenckes I (November 2, 1818 – November 4, 1875) was a United States representative from Rhode Island. Jenckes was best known for introducing a bill that created the United States Department of Justice. President Ulysses S. Grant th ...

of Rhode Island

Rhode Island (, like ''road'') is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is the List of U.S. states by area, smallest U.S. state by area and the List of states and territories of the United States ...

during the presidency of Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union A ...

introduced legislation pushing for mild civil service reform, which was enacted. Jenckes, who disregarded the plight of Southern blacks facing danger from Democratic white supremacist

White supremacy or white supremacism is the belief that white people are superior to those of other races and thus should dominate them. The belief favors the maintenance and defense of any power and privilege held by white people. White s ...

terrorist

Terrorism, in its broadest sense, is the use of criminal violence to provoke a state of terror or fear, mostly with the intention to achieve political or religious aims. The term is used in this regard primarily to refer to intentional violen ...

s such as the Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to the KKK or the Klan, is an American white supremacist, right-wing terrorist, and hate group whose primary targets are African Americans, Jews, Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and Cat ...

, left office before the congressional "Half-Breeds" obtained its reputation as a functioning bloc, though can be viewed as a forerunner to the faction.

Ideology and leadership

Although the Half-Breeds had no rigid organization as a congressional bloc and were viewed as merely a group of disgruntled Blaine supporters promoting factionalism, their influence proved to be highly significant.Welch, Robert E. Jr. (1971)

Although the Half-Breeds had no rigid organization as a congressional bloc and were viewed as merely a group of disgruntled Blaine supporters promoting factionalism, their influence proved to be highly significant.Welch, Robert E. Jr. (1971)George Frisbie Hoar and the Half-Breed Republicans

pp. 2–3. ''Harvard University Press''. They viewed the term attributed negatively to them as either badges of honor or an identifying mark, a parallel to the Democratic Party's embracing of the donkey as their symbol after

Jacksonian Democrats

Jacksonian democracy was a 19th-century political philosophy in the United States that expanded suffrage to most white men over the age of 21, and restructured a number of federal institutions. Originating with the seventh U.S. president, And ...

were dubbed "jackasses."

When accused of lacking sufficient political loyalty to the Republican Party, Half-Breeds would often accuse Stalwarts of holding excessive allegiance to their associated political machines and patronage. Among the group's ambitions aside from moderate civil service reform included advocating industrial strength, railroad

Rail transport (also known as train transport) is a means of transport that transfers passengers and goods on wheeled vehicles running on rails, which are incorporated in tracks. In contrast to road transport, where the vehicles run on a prep ...

interests, higher protective tariffs,About the Vice President , Levi Parsons Morton, 22nd Vice President (1889-1893)''United States Senate''. Retrieved February 12, 2022. expanding markets abroad, and a business-friendly currency system on the national level. According to Professor Richard E. Welch Jr., the Half-Breeds were "party regulars" who "damned" bolters, were not uniformly independent in political nature nor advocates of the spoils system, and more intelligent than personal in comparison to the Stalwarts.

James G. Blaine

James Gillespie Blaine (January 31, 1830January 27, 1893) was an American statesman and Republican politician who represented Maine in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1863 to 1876, serving as Speaker of the U.S. House of Representati ...

, who led the faction in 1880, was personally opposed to civil service reformWeisberger, Bernard AJames A. Garfield and Chester A. Arthur

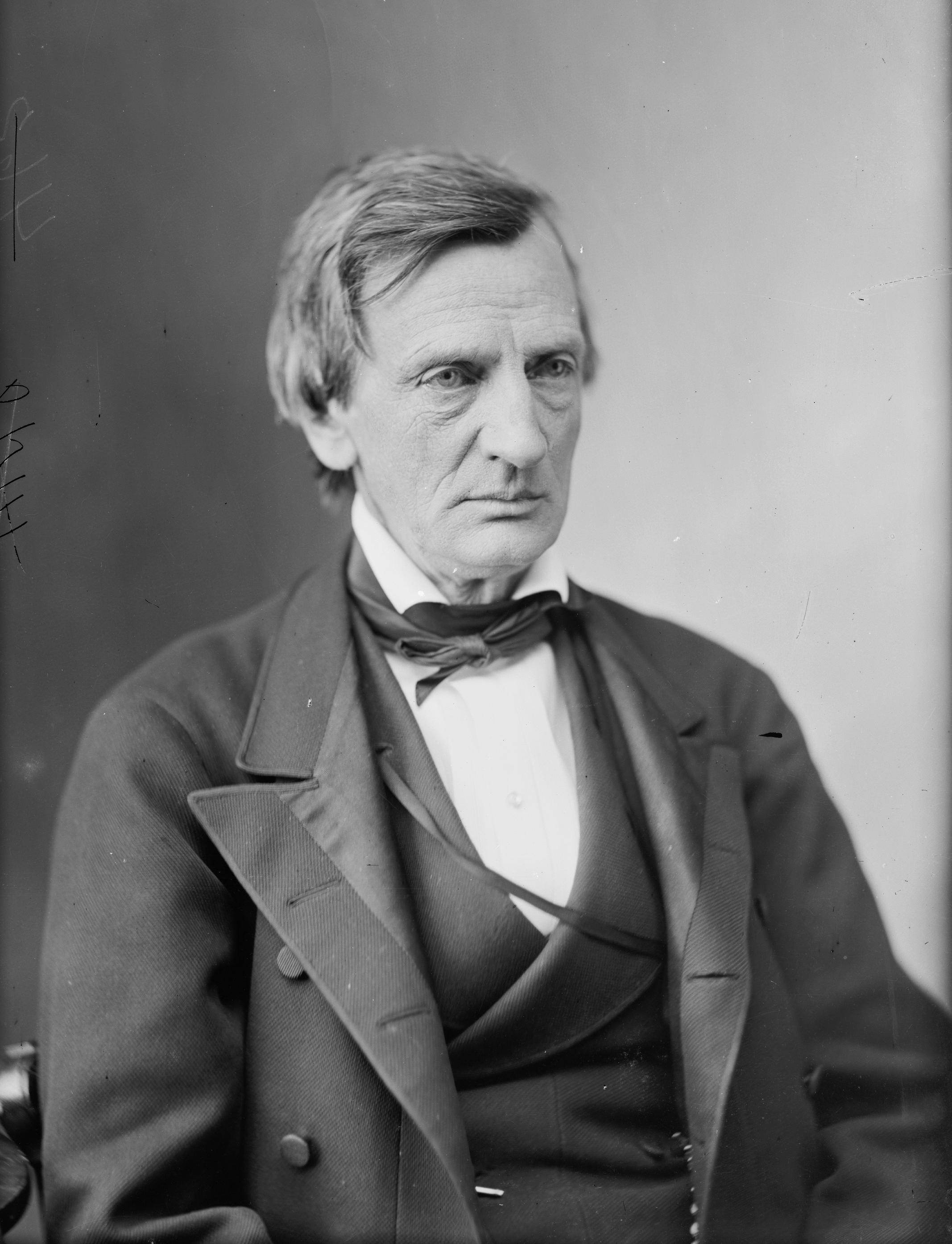

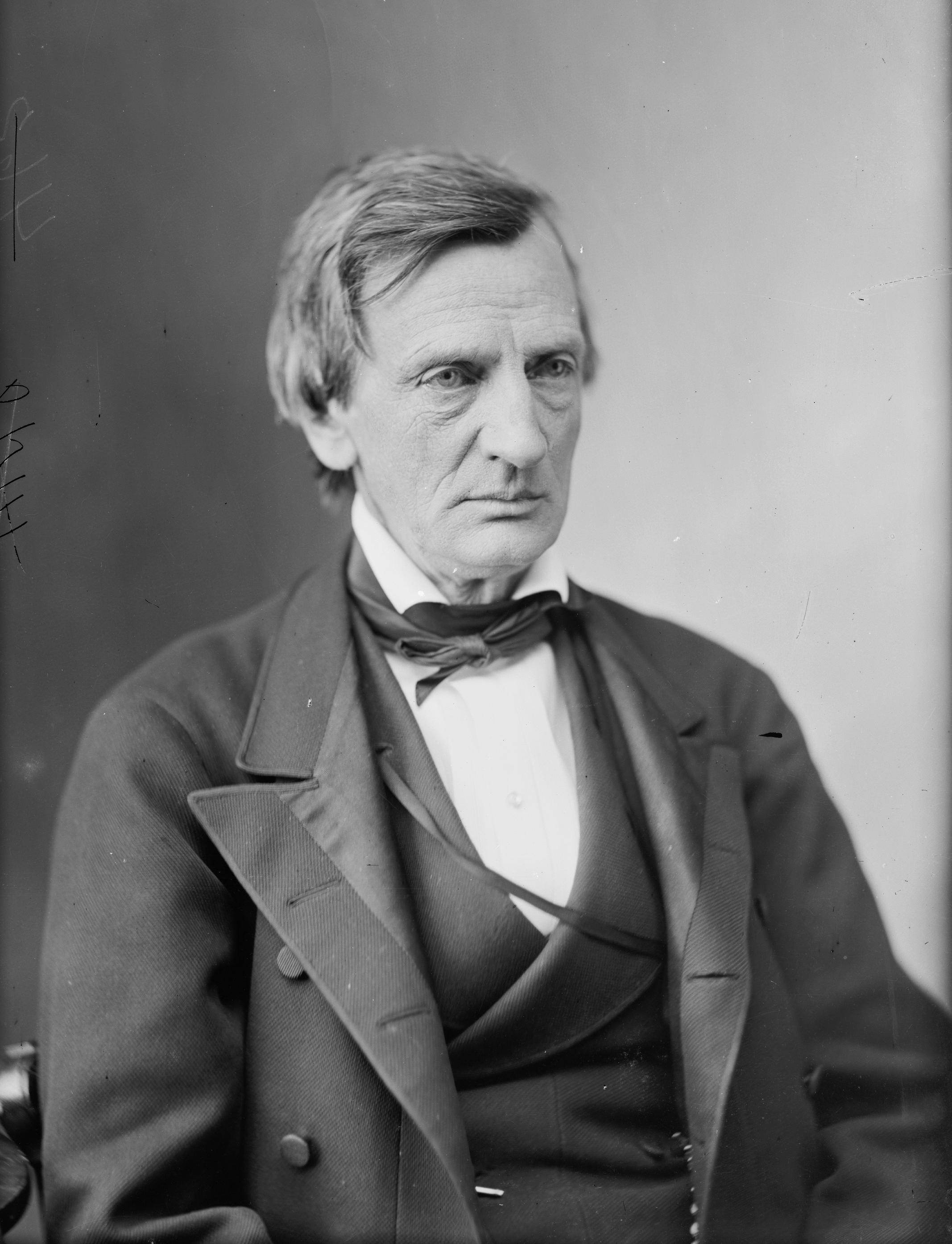

''Encyclopedia.com''. Retrieved February 12, 2022. and opposed questionable policies pushed by President Hayes. He emerged as one of its main members largely due to sheer contempt for Stalwart

Roscoe Conkling

Roscoe Conkling (October 30, 1829April 18, 1888) was an American lawyer and Republican politician who represented New York in the United States House of Representatives and the United States Senate. He is remembered today as the leader of the ...

, pertaining to a rivalry dating back to the 1860s.

Many sources published in the contemporary era tend to attribute the leader of the Half-Breeds to Blaine and sometimes even suggest that he himself was a supporter of civil service reform, which is misleading and erroneous. Per the writings of Professor Welch:''George Frisbie Hoar and the Half-Breed Republicans'', p. 91.

Viewpoints on civil rights varied among members of the Half-Breed faction. Some such as Hayes, Evarts, McCrary and Wheeler were willing to entirely abandon Reconstruction efforts and surrender the South to the Redeemers

The Redeemers were a political coalition in the Southern United States during the Reconstruction Era that followed the Civil War. Redeemers were the Southern wing of the Democratic Party. They sought to regain their political power and enforce ...

, while the more pro-civil rights Hoar and Blair favored an alternative to military Reconstruction in the form of increased public education funding to alleviate a large percentage of Southern blacks from illiteracy.

Timeline

GOP campaign, 1876

During the 1876 presidential election, the Republican National Convention nominatedRutherford Hayes Rutherford may refer to:

Places Australia

* Rutherford, New South Wales, a suburb of Maitland

* Rutherford (Parish), New South Wales, a civil parish of Yungnulgra County

Canada

* Mount Rutherford, Jasper National Park

* Rutherford, Edmont ...

and William Wheeler to head the party ticket for the general election. Both Hayes and Wheeler sought to peel away Democrat support from the South by voicing conciliatory tones,About the Vice President , William A. Wheeler, 19th Vice President (1877-1881)''United States Senate''. Retrieved February 12, 2022. attempting to draw support from upper-class old Southern Whigs who eventually joined the Democratic Party when the Whig Party collapsed.

Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, February 1817 or 1818 – February 20, 1895) was an American social reformer, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. After escaping from slavery in Maryland, he became ...

asked at the party convention whether delegates would continue to uphold the constitutional rights of blacks, or if they intended to "get along without the vote of the black man in the South." Hayes and Wheeler chose the latter.

Hayes presidency

TheCompromise of 1877

The Compromise of 1877, also known as the Wormley Agreement or the Bargain of 1877, was an unwritten deal, informally arranged among members of the United States Congress, to settle the intensely disputed 1876 presidential election between Ruth ...

that resolved the controversies and disputes of the 1876 presidential election

The 1876 United States presidential election was the 23rd quadrennial presidential election, held on Tuesday, November 7, 1876, in which Republican nominee Rutherford B. Hayes faced Democrat Samuel J. Tilden. It was one of the most contentious ...

gave the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. president since John Adams in ...

to Hayes over Bourbon Democrat

Bourbon Democrat was a term used in the United States in the later 19th century (1872–1904) to refer to members of the Democratic Party who were ideologically aligned with fiscal conservatism or classical liberalism, especially those who su ...

opponent Samuel J. Tilden. Soon after taking office, Hayes abandoned his past Radical Republican

The Radical Republicans (later also known as "Stalwarts") were a faction within the Republican Party, originating from the party's founding in 1854, some 6 years before the Civil War, until the Compromise of 1877, which effectively ended Recon ...

ism and along with Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

George W. McCrary

George Washington McCrary (August 29, 1835 – June 23, 1890) was a United States representative from Iowa, the 33rd United States Secretary of War and a United States circuit judge of the United States Circuit Courts for the Eighth Circuit.

Ed ...

pulled federal troops from the Southern states of South Carolina

)''Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

and Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is bord ...

,MCCRARY, GEORGE W.''Rutherford B. Hayes Presidential Library & Museums''. Retrieved February 12, 2022. all but ensuring a Jim Crow Democrat takeover of the region. President Hayes also pushed for civil service reform,Conkling, Roscoe

''Encyclopedia.com''. Retrieved February 12, 2022. aligning himself with the Half-Breeds. Seeking to curb the powers of Conkling and the latter's powerful

New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

political machine, Hayes removed a number of the senator's allies from the state's patronage

Patronage is the support, encouragement, privilege, or financial aid that an organization or individual bestows on another. In the history of art, arts patronage refers to the support that kings, popes, and the wealthy have provided to artists su ...

system.

Setback and rebuke

TheCollector of the Port of New York

The Collector of Customs at the Port of New York, most often referred to as Collector of the Port of New York, was a federal officer who was in charge of the collection of import duties on foreign goods that entered the United States by ship at t ...

was a highly prized position, as the port functioned as a center of international trade between the United States and other countries.Stalwarts, Half Breeds, and Political Assassination''National Park Service''. Retrieved February 12, 2022. Hayes vainly attempted to wrest control of appointments to the position from the Conkling machine to no avail, twice failing to appoint a like-minded political figure due to the successful congressional blockade initiated by the Stalwarts. Soon afterwards, Conkling appointed close ally and future president Chester A. Arthur to the post of Collector. Arthur proved to be corrupt, giving away jobs only on the basis of party affiliation with no regard for competence and qualifications. Hayes then investigated the Customs House, and along with John Sherman (the

Secretary of the Treasury

The United States secretary of the treasury is the head of the United States Department of the Treasury, and is the chief financial officer of the federal government of the United States. The secretary of the treasury serves as the principal a ...

) removed Arthur from the position.

Blaine supporters temporarily join Stalwarts against Hayes

Hayes' decision to remove Arthur from the New York Customs House angered not only Stalwarts but even elicited the criticism of the Blaine faction, who questioned the wisdom of the action and had earlier stood side-by-side with the president.The Key Political Issues: Patronage, Tariffs, and Gold''University of Central Florida''. Retrieved February 12, 2022. Any remaining hopes of a party renomination for Hayes in the 1880 presidential election depended on support from potential Blaine supporters. With this needed bolstering evaporating, he faced no chance of becoming the Republican nominee for the race. The Blaine organization instead turned to advocate a nomination of their leader, Senator Blaine. During the Hayes years, Blaine frequently joined Stalwarts in voting against the president's nominees, including

Theodore Roosevelt Sr.

Theodore Roosevelt Sr. (September 22, 1831 – February 9, 1878) was an American businessman and philanthropist from the Roosevelt family. Roosevelt was also the father of President Theodore Roosevelt and the paternal grandfather of First Lady E ...

, Edwin Atkins Merritt, and Silas W. Burt. The nomination of Roosevelt Sr. was supported by Democrats and several Half-Breed leaders such as Hoar, but were defeated by the majority of Republicans under the leadership of Conkling.

1880 United States presidential election

In the1880 Republican National Convention

The 1880 Republican National Convention convened from June 2 to June 8, 1880, at the Interstate Exposition Building in Chicago, Illinois, United States. Delegates nominated James A. Garfield of Ohio and Chester A. Arthur of New York (state), N ...

, the Stalwart candidate, former president Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union A ...

, was pitted against James G. Blaine

James Gillespie Blaine (January 31, 1830January 27, 1893) was an American statesman and Republican politician who represented Maine in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1863 to 1876, serving as Speaker of the U.S. House of Representati ...

for the party nomination. Grant's campaign was led by Stalwart leaders John A. Logan of Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolitan areas include, Peoria and Rock ...

, Simon Cameron

Simon Cameron (March 8, 1799June 26, 1889) was an American businessman and politician who represented Pennsylvania in the United States Senate and served as United States Secretary of War under President Abraham Lincoln at the start of the Americ ...

and his son J. Donald Cameron of Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

, and Roscoe Conkling

Roscoe Conkling (October 30, 1829April 18, 1888) was an American lawyer and Republican politician who represented New York in the United States House of Representatives and the United States Senate. He is remembered today as the leader of the ...

of New York, the state with the deepest split between Stalwarts and Half-Breeds. Despite Conkling's attempts at imposing a unit-rule in the Republican National Convention by which a state's votes would be grouped together for only one candidate, a number of Stalwarts went against him by vocalizing their support for the Blaine. Half-Breeds and the Blaine faction united to defeat the unit-rule in a vote, and elected Half-Breed George Frisbie Hoar

George Frisbie Hoar (August 29, 1826 – September 30, 1904) was an American attorney and politician who represented Massachusetts in the United States Senate from 1877 to 1904. He belonged to an extended family that became politically prominen ...

to the position as temporary chairman of the convention.

Both sides knew there was no chance of victory for either candidate, and the Half-Breeds chose James Garfield

James Abram Garfield (November 19, 1831 – September 19, 1881) was the 20th president of the United States, serving from March 4, 1881 until his death six months latertwo months after he was shot by an assassin. A lawyer and Civil War gene ...

as a compromise candidate. Garfield won the party's nomination on the thirty-sixth ballot, and subsequently emerged victorious in the general election

A general election is a political voting election where generally all or most members of a given political body are chosen. These are usually held for a nation, state, or territory's primary legislative body, and are different from by-elections ( ...

narrowly.

Garfield Administrations, assassination, aftermath

Blaine was chosen as Garfield's Secretary of State, and carried heavy influence over the political appointments Garfield issued for congressional approval. After Garfield was assassinated by Charles J. Guiteau, a self-professed Stalwart, who proclaimed, "I am a Stalwart of the Stalwarts and Arthur will be President," the new Stalwart president Chester A. Arthur surprised those in his own faction by promoting civil service reform and issuing government jobs based on a merit system.

The Half-Breeds put through Congress the

Blaine was chosen as Garfield's Secretary of State, and carried heavy influence over the political appointments Garfield issued for congressional approval. After Garfield was assassinated by Charles J. Guiteau, a self-professed Stalwart, who proclaimed, "I am a Stalwart of the Stalwarts and Arthur will be President," the new Stalwart president Chester A. Arthur surprised those in his own faction by promoting civil service reform and issuing government jobs based on a merit system.

The Half-Breeds put through Congress the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act

The Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act is a United States federal law passed by the 47th United States Congress and signed into law by President Chester A. Arthur on January 16, 1883. The act mandates that most positions within the federal govern ...

(authored by Democrat George H. Pendleton), and Arthur signed the bill into law on January 16, 1883. The act put an end to the spoils system

In politics and government, a spoils system (also known as a patronage system) is a practice in which a political party, after winning an election, gives government jobs to its supporters, friends (cronyism), and relatives (nepotism) as a reward ...

, at least symbolically, placing a significant number of federal employees under the merit system and putting the government on the road to true reform. The act also set up the United States Civil Service Commission

The United States Civil Service Commission was a government agency of the federal government of the United States and was created to select employees of federal government on merit rather than relationships. In 1979, it was dissolved as part of t ...

, banished political tests, denied jobs to alcoholics and created competitive measures for some federal positions.

All Senate Republicans present voted for the Pendleton Act, in addition to all but seven House Republicans. The primary opposition thus came from Democrats who likely voted against it due to the party's Jacksonian roots.The spoils system was originally a principle of the Jacksonian Democrats. The legislation passed both houses of Congress and was signed into law by President Arthur.

The Pendleton Act notably did not elicit enthusiastic support from Half-Breed Blaine, who continued his personal antipathy towards civil service reform.

1884: Mugwumps replace Half-Breeds as role of "reformer"

In the 1884 presidential election, President Arthur found insufficient support for his re-election campaign, and faced a formidable challenge from Blaine. Reformers, including future presidentTheodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

, pushed again to nominate Edmunds. However, the Vermont senator had no intention of seeking the presidency, stating to Hoar in a conversation at some point:''The Downfall of George F. Edmunds'', p. 130.

The Republican National Convention ultimately nominated Half-Breed Blaine and former Stalwart John A. Logan of

The Republican National Convention ultimately nominated Half-Breed Blaine and former Stalwart John A. Logan of Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolitan areas include, Peoria and Rock ...

to head the party ticket. With both factions appeased, the majority of Republicans on both sides actively organized the GOP campaign.Jones, James Pickett (1982)''John A. Logan: Stalwart Republican from Illinois''

p. 186. Due to both Blaine and Logan having a record of favoring the spoils system over civil service reform, "reformers" in the

Mugwump

The Mugwumps were Republican political activists in the United States who were intensely opposed to political corruption. They were never formally organized. Typically they switched parties from the Republican Party by supporting Democratic ...

faction such as political cartoon

A political cartoon, a form of editorial cartoon, is a cartoon graphic with caricatures of public figures, expressing the artist's opinion. An artist who writes and draws such images is known as an editorial cartoonist. They typically combin ...

ist Thomas Nast

Thomas Nast (; ; September 26, 1840December 7, 1902) was a German-born American caricaturist and editorial cartoonist often considered to be the "Father of the American Cartoon".

He was a critic of Democratic Representative "Boss" Tweed and ...

of ''Harper's Weekly

''Harper's Weekly, A Journal of Civilization'' was an American political magazine based in New York City. Published by Harper & Brothers from 1857 until 1916, it featured foreign and domestic news, fiction, essays on many subjects, and humor, ...

'' opposed the party ticket and instead supported the pro-civil service reform Bourbon Democrat

Bourbon Democrat was a term used in the United States in the later 19th century (1872–1904) to refer to members of the Democratic Party who were ideologically aligned with fiscal conservatism or classical liberalism, especially those who su ...

nominee, Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 22nd and 24th president of the United States from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. Cleveland is the only president in American ...

. Former Liberal Republican Party figure Lyman Trumbull

Lyman Trumbull (October 12, 1813 – June 25, 1896) was a lawyer, judge, and United States Senator from Illinois and the co-author of the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

Born in Colchester, Connecticut, Trumbull es ...

, known in part for previously voting against convicting Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. He assumed the presidency as he was vice president at the time of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a De ...

, denounced the Blaine/Logan ticket and stated that their potential victory would lead to "partisanship, abuses, and corruption." The Mugwumps in effect replaced the role of the Half-Breeds as advocates of reform who broke from party traditions.

Logan's presence on the party ticket helped draw enthusiastic support from blacks due to his record of staunchly advocating for civil rights.''John A. Logan: Stalwart Republican from Illinois'', p. 187–88. This included the backing of abolitionist and renowned black leader Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, February 1817 or 1818 – February 20, 1895) was an American social reformer, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. After escaping from slavery in Maryland, he became ...

. Most Half-Breeds were skeptical of Logan, though supported the ticket out of party unity; this included Rutherford Hayes, who called the nomination a "blunder and misfortune" though viewed a Democrat victory as a "serious calamity." Half-Breed John Sherman

John Sherman (May 10, 1823October 22, 1900) was an American politician from Ohio throughout the Civil War and into the late nineteenth century. A member of the Republican Party, he served in both houses of the U.S. Congress. He also served as ...

expressed similar sentiment, calling Logan "coarse, suspicious, revengeful" yet voicing support for the GOP ticket.

Not all Half-Breeds supported the ticket; Sen. George F. Edmunds, who believed a true Half-Breed must support civil service reform and thus distrusted Blaine, declined to give the pair any support throughout the campaign. He viewed his Maine colleague as a mere selfish opportunist and refused to support the pair, writing:

Stalwart leader Conkling, who by this time retired from political life, still maintained his personal disdain for Blaine to such an extent that even Logan's presence on the ticket did not prompt him to campaign for the pair. When asked to bolster Blaine, he bluntly responded:

In the general election, the Blaine/Logan ticket lost to Cleveland, particularly failing to carry the state of New York due to Samuel D. Burchard, a Protestant minister associated with Blaine who attacked the Democrats as the party of "rum, Romanism, and rebellion."Rum was a reference to saloon keepers, "Romanism" meant Catholicism, and "rebellion" referred to the Confederacy. The remark was seized by Democrats, who riled up Irish Catholics to turn out against the Republicans. Following the results, Grand Army of the Republic leader Mortimer D. Leggett stated:''John A. Logan: Stalwart Republican from Illinois'', p. 195.

The Half-Breed and Stalwart factions both dissolved towards the end of the 1880s.

See also

* Republican In Name Only, a contemporary designation for Republican Party members deemed insufficiently loyal to the Party or insufficiently conservative in their views.References

Notes

{{reflist, group=noteFurther reading

* Peskin, Allan. "Who were the Stalwarts? Who were their rivals? Republican factions in the Gilded Age." ''Political Science Quarterly'' 99#4 (1984): 703-716in JSTOR

Republican Party (United States) terminology * Civil service reform in the United States Assassination of James A. Garfield Factions in the Republican Party (United States) Classical liberalism Centrism in the United States