Haiti indemnity controversy on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Haiti indemnity controversy involves an 1825 agreement between

The Haiti indemnity controversy involves an 1825 agreement between

Haiti's legacy of debt began shortly after a widespread

Haiti's legacy of debt began shortly after a widespread

Haiti: Her History and Her Detractors

'. The Neale Publishing Co.: New York & Washington. 1907. Accessed 19 February 2011. In 1823, the United Kingdom recognized the independence of

From 1880 to 1881, Haiti granted a currency issuance concession to create the National Bank of Haiti (BNH), headquartered in Paris by CIC which was simultaneously funding the construction of the

From 1880 to 1881, Haiti granted a currency issuance concession to create the National Bank of Haiti (BNH), headquartered in Paris by CIC which was simultaneously funding the construction of the

In 1903, Haitian authorities began to accuse the BNH of fraud and by 1908, Haitian

In 1903, Haitian authorities began to accuse the BNH of fraud and by 1908, Haitian

File:Ordinace original screenshot.png, Image of the First Page of the Original Handwritten Ordinance.

File:Ordenanza de emancipación de Haití.png, Printed copy of the Ordinance.

File:Ordenanza de emancipacion.png, Photograph of the Ordinance in the French Law Bulletin, the Official Gazette of the French government (Law Bulletin, Volume No. 58 – Law No. 1798 – April 17, 1825)

File:Jean Boyer firma la ordenanza de 1825.png, Engraving showing Haitian President Jean Pierre Boyer with an Inkwell, Quill, and Scroll in his right hand, ready to sign the ordinance. To the left of him, in the background, French sailors can be seen on the Port-au-Prince dock, making sure that the ordinance is signed.

File:Grabado de Carlos X de Francia danddole la independencia a Haití.jpg, Engraving titledː

"His Majesty, Charles X, The Beloved, recognizing

the Independence '' of Saint-Domingue''

France Urged to Pay $40 Billion to Haiti in Reparations for "Independence Debt"

– video report by ''

The Haiti indemnity controversy involves an 1825 agreement between

The Haiti indemnity controversy involves an 1825 agreement between Haiti

Haiti (; ht, Ayiti ; French: ), officially the Republic of Haiti (); ) and formerly known as Hayti, is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean Sea, east of Cuba and Jamaica, and ...

and France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

that included France demanding a 150 million franc

The franc is any of various units of currency. One franc is typically divided into 100 centimes. The name is said to derive from the Latin inscription ''francorum rex'' (Style of the French sovereign, King of the Franks) used on early France, ...

indemnity

In contract law, an indemnity is a contractual obligation of one party (the ''indemnitor'') to compensate the loss incurred by another party (the ''indemnitee'') due to the relevant acts of the indemnitor or any other party. The duty to indemni ...

to be paid by Haiti in claims over property – including Haitian slaves

Haitian may refer to:

Relating to Haiti

* ''Haitian'', an adjective referring to something of, from, or related to Haiti

** Haitian Creole, a French-Creole based

** Haitian French, variant of the French language

** Haitians, an ethnic group

* ...

– that was lost through the Haitian Revolution

The Haitian Revolution (french: révolution haïtienne ; ht, revolisyon ayisyen) was a successful insurrection by slave revolt, self-liberated slaves against French colonial rule in Saint-Domingue, now the sovereign state of Haiti. The revolt ...

in return for diplomatic recognition, with the debt removing $21 billion from the Haitian economy. The payment was later reduced to 90 million francs in 1838, comparable to US$21 billion as of 2004, with Haiti paying about 112 million francs in total. Over the 122 years between 1825 and 1947, the debt severely hampered Haitian economic development as payments of interest and downpayments totaled a significant share of Haitian GDP

Gross domestic product (GDP) is a monetary measure of the market value of all the final goods and services produced and sold (not resold) in a specific time period by countries. Due to its complex and subjective nature this measure is ofte ...

, constraining the use of domestic financial funds for infrastructure and public services.

France's demand of payments in exchange for recognizing Haiti's independence was delivered to the country by several French warships in 1825, twenty-one years after Haiti's declaration of independence in 1804. Due to the unrealistic demands pushed by France, Haiti was forced to take large loans from French bank Crédit Industriel et Commercial

The Crédit Industriel et Commercial (CIC, "Industrial and Commercial Credit Company") is a bank and financial services group in France, founded in 1859. It has been majority owned by Crédit Mutuel, one of the country's top five banking groups, ...

, enriching the bank's shareholders. Though France received its last indemnity payment in 1888, the government of the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

funded the acquisition of Haiti's treasury in 1911 in order to receive interest payments related to the indemnity.Douglas, Paul H. from ''Occupied Haiti,'' ed. Emily Greene Balch (New York, 1972), 15–52 reprinted in: ''Money Doctors, Foreign Debts, and Economic Reforms in Latin America

Latin America or

* french: Amérique Latine, link=no

* ht, Amerik Latin, link=no

* pt, América Latina, link=no, name=a, sometimes referred to as LatAm is a large cultural region in the Americas where Romance languages — languages derived f ...

.'' Wilmington, Delaware

Wilmington ( Lenape: ''Paxahakink /'' ''Pakehakink)'' is the largest city in the U.S. state of Delaware. The city was built on the site of Fort Christina, the first Swedish settlement in North America. It lies at the confluence of the Christina ...

: Edited by Paul W. Drake, 1994. In 1922, the rest of Haiti's debt to France was moved to be paid to American investors. It took until 1947 – about 122 years – for Haiti to finally pay off all the associated interest to the National City Bank of New York (now Citibank

Citibank, N. A. (N. A. stands for " National Association") is the primary U.S. banking subsidiary of financial services multinational Citigroup. Citibank was founded in 1812 as the City Bank of New York, and later became First National City ...

). In 2016, the Parliament of France

The French Parliament (french: Parlement français) is the bicameral legislature of the French Republic, consisting of the Senate () and the National Assembly (). Each assembly conducts legislative sessions at separate locations in Paris: ...

repealed the 1825 ordinance of Charles X, though no reparations

Reparation(s) may refer to:

Christianity

* Restitution (theology), the Christian doctrine calling for reparation

* Acts of reparation, prayers for repairing the damages of sin

History

*War reparations

**World War I reparations, made from G ...

have been offered by France. These debts are denounced as the root of modern Haiti's poverty and a case of odious debt

In international law, odious debt, also known as illegitimate debt, is a legal theory that says that the national debt incurred by a despotic regime should not be enforceable. Such debts are, thus, considered by this doctrine to be personal debts ...

, debts forced upon a populations by abusive force. In 2022, The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

published a dedicated investigative series on the topic.

History

Saint-Domingue colony

Saint-Domingue

Saint-Domingue () was a French colony in the western portion of the Caribbean island of Hispaniola, in the area of modern-day Haiti, from 1659 to 1804. The name derives from the Spanish main city in the island, Santo Domingo, which came to refer ...

, now Haiti, was the richest and most productive European colony in the world going into the 1800s. France acquired much of its wealth by using slaves, with the slave population of Saint-Domingue accounting for one third of the entire Atlantic slave trade

The Atlantic slave trade, transatlantic slave trade, or Euro-American slave trade involved the transportation by slave traders of enslaved African people, mainly to the Americas. The slave trade regularly used the triangular trade route and i ...

. Between the years of 1697 and 1804, French colonists brought 800,000 West Africa

West Africa or Western Africa is the westernmost region of Africa. The United Nations defines Western Africa as the 16 countries of Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Mali, Maurit ...

n slaves to what was then known as Saint-Domingue to work on the vast plantations. The Saint-Domingue population reached 520,000 in 1790, and of those 425,000 were slaves. The mortality rate among slaves was high, with the French often working slaves to death and transporting more to the colony instead of providing necessities as it was cheaper. At the time, goods from Haiti comprised thirty percent of French trade while its sugar represented forty percent of the Atlantic market. About sixty percent of the coffee consumed in European markets was also produced in the colony.

Independent Haiti

Haiti's legacy of debt began shortly after a widespread

Haiti's legacy of debt began shortly after a widespread slave revolt

A slave rebellion is an armed uprising by enslaved people, as a way of fighting for their freedom. Rebellions of enslaved people have occurred in nearly all societies that practice slavery or have practiced slavery in the past. A desire for freed ...

against the French, with Haitians gaining their independence from France in 1804. President Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

– fearing that slaves gaining their independence would spread to the United States – ceased the aid that was initiated by his predecessor John Adams

John Adams (October 30, 1735 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, attorney, diplomat, writer, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the second president of the United States from 1797 to 1801. Befor ...

and sought the international isolation of Haiti during his tenure. Haiti had hoped that the United Kingdom would support their recognition due to the kingdom's strained history with France, even providing British merchants lower import duties

A tariff is a tax imposed by the government of a country or by a supranational union on imports or exports of goods. Besides being a source of revenue for the government, import duties can also be a form of regulation of foreign trade and pol ...

, though during the Congress of Vienna

The Congress of Vienna (, ) of 1814–1815 was a series of international diplomatic meetings to discuss and agree upon a possible new layout of the European political and constitutional order after the downfall of the French Emperor Napoleon B ...

in 1815 the British government

ga, Rialtas a Shoilse gd, Riaghaltas a Mhòrachd

, image = HM Government logo.svg

, image_size = 220px

, image2 = Royal Coat of Arms of the United Kingdom (HM Government).svg

, image_size2 = 180px

, caption = Royal Arms

, date_es ...

agreed not to prevent France's actions by "whatever means possible, including that of arms, to recover Saint-Domingue and to subdue the inhabitants of that colony".Leger, J.N. Haiti: Her History and Her Detractors

'. The Neale Publishing Co.: New York & Washington. 1907. Accessed 19 February 2011. In 1823, the United Kingdom recognized the independence of

Colombia

Colombia (, ; ), officially the Republic of Colombia, is a country in South America with insular regions in North America—near Nicaragua's Caribbean coast—as well as in the Pacific Ocean. The Colombian mainland is bordered by the Car ...

, Mexico

Mexico (Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a country in the southern portion of North America. It is bordered to the north by the United States; to the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; to the southeast by Guatema ...

and other nations in the Americas

The Americas, which are sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North and South America. The Americas make up most of the land in Earth's Western Hemisphere and comprise the New World.

Along with th ...

while refraining from extending recognition to Haiti, further disillusioning Haitians seeking recognition.

Until France recognized Haiti's independence, the fear of reconquest and continued isolation would persist among Haitians. Haiti was also financially strained after purchasing equipment to defend itself from invasion. Knowing that improvements could not happen until Haiti received international recognition, President of Haiti

The president of Haiti ( ht, Prezidan peyi Ayiti, french: Président d'Haïti), officially called the president of the Republic of Haiti (french: link=no, Président de la République d'Haïti, ht, link=no, Prezidan Repiblik Ayiti), is the head ...

Jean-Pierre Boyer

Jean-Pierre Boyer (15 February 1776 – 9 July 1850) was one of the leaders of the Haitian Revolution, and President of Haiti from 1818 to 1843. He reunited the north and south of the country into the Republic of Haiti in 1820 and also annexed ...

sent envoys to negotiate terms with France. At one meeting in Brussels

Brussels (french: Bruxelles or ; nl, Brussel ), officially the Brussels-Capital Region (All text and all but one graphic show the English name as Brussels-Capital Region.) (french: link=no, Région de Bruxelles-Capitale; nl, link=no, Bruss ...

on 16 August 1823, Haiti proposed waiving all import duties for five years on French products and then duties would be halved at the end of the period; France refused the offer outright. By 1824, President Boyer began to prepare Haiti for a defensive war, moving armaments inland to provide increased protection. After being summoned by France, two Haitian envoys travelled to Paris. At the meetings held between June and August 1824, Haiti offered to pay indemnity to France, though negotiations ended after France said it would only recognize their former territory on the west half of Hispaniola

Hispaniola (, also ; es, La Española; Latin and french: Hispaniola; ht, Ispayola; tnq, Ayiti or Quisqueya) is an island in the Caribbean that is part of the Greater Antilles. Hispaniola is the most populous island in the West Indies, and th ...

and that it sought to maintain control of Haiti's foreign relations.

Ordinance of Charles X

As ashow of force

A show of force is a military operation intended to warn (such as a warning shot) or to intimidate an opponent by showcasing a capability or will to act if one is provoked. Shows of force may also be executed by police forces and other armed, non ...

, captain Ange René Armand, baron de Mackau

Ange René Armand, Baron de Mackau (17 February 1788 – 13 May 1855) was a French naval officer and politician. In 1825, he led 14 brigs of war to Haiti in one of the earliest instances of gunboat diplomacy, forcing the recently emancipated peopl ...

, in the ship ''La Circe'', along with two men-of-war

The man-of-war (also man-o'-war, or simply man) was a Royal Navy expression for a powerful warship or frigate from the 16th to the 19th century. Although the term never acquired a specific meaning, it was usually reserved for a ship armed w ...

, arrived at Port-au-Prince

Port-au-Prince ( , ; ht, Pòtoprens ) is the capital and most populous city of Haiti. The city's population was estimated at 987,311 in 2015 with the metropolitan area estimated at a population of 2,618,894. The metropolitan area is define ...

on 3 July 1825. Soon after, more warships led by admirals Pierre Roch Jurien de La Gravière

Pierre Roch Jurien de La Gravière (5 November 1772 – 14 January 1849) was a French naval officer.

Biography

Born at Gannat in Allier, La Gravière entered the service under the name Jurien Desvarennes as a novice pilot on the corvet ...

and Grivel arrived at Haiti. A total of fourteen French warships equipped with 528 cannons presented demands that Haiti compensate France for its loss of slaves and the 1804 Haiti massacre.

The following ordinance of Charles X

Charles X (born Charles Philippe, Count of Artois; 9 October 1757 – 6 November 1836) was King of France from 16 September 1824 until 2 August 1830. An uncle of the uncrowned Louis XVII and younger brother to reigning kings Louis XVI and Lou ...

, King of France

France was ruled by monarchs from the establishment of the Kingdom of West Francia in 843 until the end of the Second French Empire in 1870, with several interruptions.

Classical French historiography usually regards Clovis I () as the first ...

, was presented:

The Haitians wanted the French to recognize the Spanish part of the island as part of Haitian territory. However, the French flatly ignored this request. France returned the Spanish part of the island to Spain in the Treaty of Paris of 1814, which annulled the Treaty of Basel of 1795.

Under Charles X's ordinance, France demanded an indemnity payment of 150 million francs in exchange for recognizing Haiti's independence. In addition to the payment, Charles ordered that Haiti provide a fifty percent discount on French import duties, making payment to France more difficult. On 11 July 1825, the senate of Haiti signed the agreement of paying indemnity to France.

Indemnity payment

The payments were designed by France to be so large that it would effectively create a "double debt"; France would receive a direct annual payment and Haiti would pay French bankers interest on the loans required to meet France's annual demands. France viewed Haiti's debt as the "principal interest in Haiti, the question that dominated everything else for us", according to a French minister. Much of the debt would be paid directly to the French state-owned Caisse des dépôts et consignations. France ordered Haiti to pay the 150 million francs over a period of five years, with the first annual payment of 30 million francs being six times larger than Haiti's yearly revenue, requiring Haiti to take out a loan from the French bank Ternaux Gandolphe et Cie to make the payment. The first 30 million francs required a 24 million franc loan from Ternaux Gandolphe et Cie that resulted in highinterest

In finance and economics, interest is payment from a borrower or deposit-taking financial institution to a lender or depositor of an amount above repayment of the principal sum (that is, the amount borrowed), at a particular rate. It is distinct ...

and Haiti's treasury was completely emptied, with a French ship transporting locked shipments of money to Paris. The story of the first payment – 24,000,000 gold francs – being transported across Paris, from the vaults of Ternaux Gandolphe et Cie to the coffers of the French Treasury was recorded in detail.

Haiti would continue to acquire loans from France and the United States in order to fulfill payments. Such large payments became impossible for Haiti and defaults occurring immediately, with Haiti's late payments often raising tensions with France. Ternaux Gandolphe et Cie seized assets of the Haitian government for failing to pay on its loan, though the Tribunal de la Seine overturned these actions on 2 May 1828. On 12 February 1838, France finally agreed to reduce the debt to 90 million francs to be paid over a period of 30 years to compensate former plantation owners who had lost their property; the 2004 equivalent of US$21 billion. President Boyer, who agreed to make the payments, was forced from Haiti in 1843 by citizens who demanded lower taxes and more rights.

By the late-1800s, eighty percent of Haiti's wealth was being used to pay foreign debt; France was the highest collector, followed by Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

and the United States. Henri Durrieu, head of the French bank Crédit Industriel et Commercial (CIC), was inspired to increase revenue for the bank by following the example of state-run banks acquiring capital from other distant French colonies such as Martinique

Martinique ( , ; gcf, label=Martinican Creole, Matinik or ; Kalinago: or ) is an island and an overseas department/region and single territorial collectivity of France. An integral part of the French Republic, Martinique is located in th ...

and Senegal

Senegal,; Wolof: ''Senegaal''; Pulaar: 𞤅𞤫𞤲𞤫𞤺𞤢𞥄𞤤𞤭 (Senegaali); Arabic: السنغال ''As-Sinighal'') officially the Republic of Senegal,; Wolof: ''Réewum Senegaal''; Pulaar : 𞤈𞤫𞤲𞤣𞤢𞥄𞤲𞤣𞤭 � ...

. In 1874 and 1875 Haiti took out two large loans from CIC, greatly increasing the nation's debt. French banks charged Haiti 40% of the loaned funds just for commissions and other fees and CIC would go on to acquire "much of Haiti's financial future", according to ''The New York Times''. Thomas Piketty

Thomas Piketty (; born 7 May 1971) is a French economist who is Professor of Economics at the School for Advanced Studies in the Social Sciences, Associate Chair at the Paris School of Economics and Centennial Professor of Economics in the I ...

described the loans as an early example of "neocolonialism

Neocolonialism is the continuation or reimposition of imperialist rule by a state (usually, a former colonial power) over another nominally independent state (usually, a former colony). Neocolonialism takes the form of economic imperialism, ...

through debt".

From 1880 to 1881, Haiti granted a currency issuance concession to create the National Bank of Haiti (BNH), headquartered in Paris by CIC which was simultaneously funding the construction of the

From 1880 to 1881, Haiti granted a currency issuance concession to create the National Bank of Haiti (BNH), headquartered in Paris by CIC which was simultaneously funding the construction of the Eiffel Tower

The Eiffel Tower ( ; french: links=yes, tour Eiffel ) is a wrought-iron lattice tower on the Champ de Mars in Paris, France. It is named after the engineer Gustave Eiffel, whose company designed and built the tower.

Locally nicknamed "'' ...

. BNH was described as an entity of "pure extraction" by Paris School of Economics

The Paris School of Economics (PSE; French: ''École d'économie de Paris'') is a French research institute in the field of economics. It offers MPhil, MSc, and PhD level programmes in various fields of theoretical and applied economics, in ...

economic historian Éric Monnet. On the board of the BNH was Édouard Delessert, the great-grandson of French slave trader and owner Jean-Joseph de Laborde

Jean-Joseph, marquis de Laborde (29 January 1724 – 18 April 1794) was a French businessman, '' fermier général'' and banker to the king, who turned politician. A liberal, he was guillotined in the French Revolution.

Biography

Laborde was b ...

who established himself when France controlled Haiti. Haitian Charles Laforestrie, who mainly lived in France and successfully pushed for Haiti to accept the 1875 loan with the CIC, later retired from his positions in Haiti amid corruption allegations, joining the BNH board in Paris after its founding. CIC would go on to take $136 million in 2022 US dollars from Haiti and distribute those funds among shareholders, who made 15% annual returns on average, not returning any of the earnings to Haiti. These funds distributed among shareholders would ultimately cost Haiti at least $1.7 billion of development. Under the French-controlled BNH, Haitian funds were overseen by France and all transitions resulted with a commission fee, with CIC shareholders profits often being larger than the entire budget for Haiti's public works. The French government finally acknowledged the payment of 90 million francs in 1888 and over a period of about seventy years, Haiti paid 112 million francs to France, about $560 million in 2022.

United States occupation of Haiti

In 1903, Haitian authorities began to accuse the BNH of fraud and by 1908, Haitian

In 1903, Haitian authorities began to accuse the BNH of fraud and by 1908, Haitian Minister of Finance

A finance minister is an executive or cabinet position in charge of one or more of government finances, economic policy and financial regulation.

A finance minister's portfolio has a large variety of names around the world, such as "treasury", " ...

Frédéric Marcelin

Frédéric Marcelin (1848–1917) was a Haitian writer and politician. Born in Port-au-Prince, Marcelin was best known for the three novels ''Marilisse'' (1903), ''La Vengeance de Mama'' (1902), and ''Thémistocle Epaminondas Labasterre'' (1901). ...

pushed for the BNH to work on the behalf of Haitians, though French officials began to devise plans to reorganize their financial interests. French envoy to Haiti Pierre Carteron wrote following Marcelin's objections that "It is of the highest importance that we study how to set up a new French credit establishment in Port-au-Prince ... Without any close link to the Haitian government." Businesses from the United States had pursued the control of Haiti for years and from 1910 to 1911, the United States Department of State

The United States Department of State (DOS), or State Department, is an executive department of the U.S. federal government responsible for the country's foreign policy and relations. Equivalent to the ministry of foreign affairs of other n ...

backed a consortium of American investors – headed by the National City Bank of New York

Citibank, N. A. (N. A. stands for " National Association") is the primary U.S. banking subsidiary of financial services multinational Citigroup. Citibank was founded in 1812 as the City Bank of New York, and later became First National City ...

– to acquire control of the National Bank of Haiti to create the Bank of the Republic of Haiti (BNRH), with the new bank often holding payments from the Haitian government, leading to unrest.

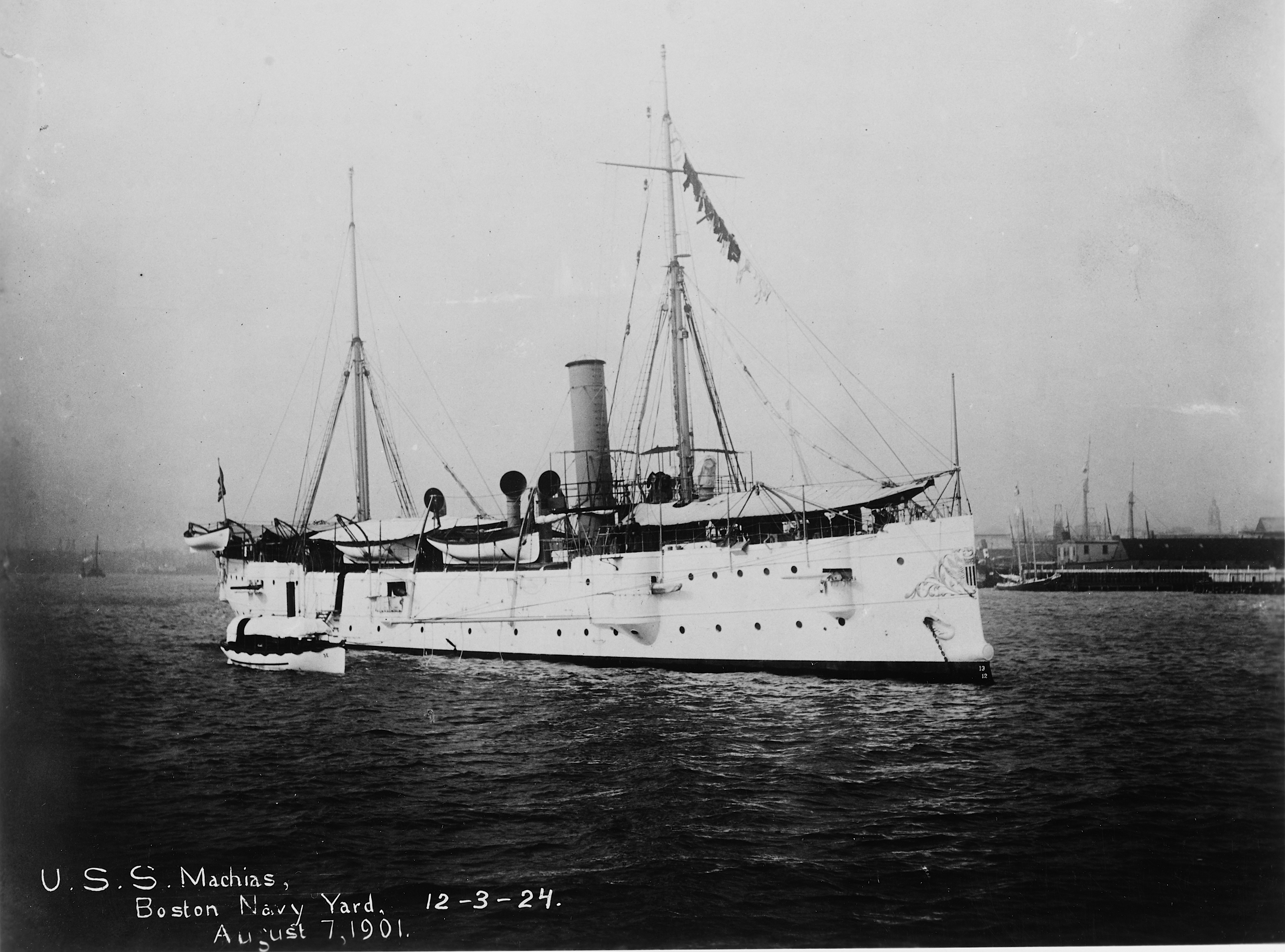

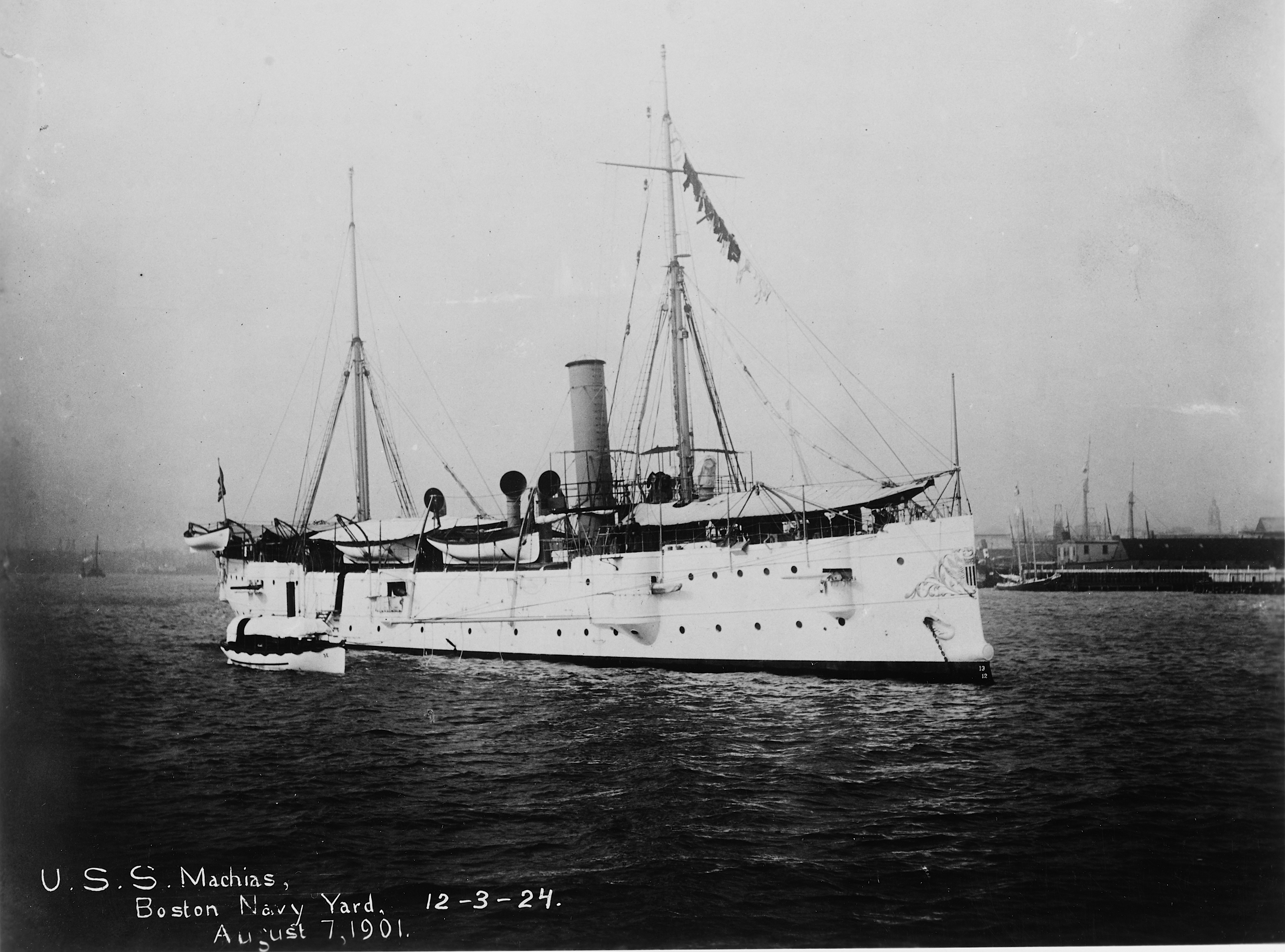

France would still keep a stake in the BNRH, though CIC was excluded. Following the overthrow of Haitian president Michel Oreste in 1914, the National City Bank and the BNRH demanded the United States Marines to take custody of Haiti's gold reserve of about US$500,000 – – in December 1914; the gold was transported aboard the USS ''Machias'' (PG-5) in wooden boxes and place into the National City Bank's New York City vault days later. The overthrow of Haiti's president Vilbrun Guillaume Sam

Jean Vilbrun Guillaume Sam (4 March 1859 – 28 July 1915) was President of Haiti from 4 March to 27 July 1915, when he was assassinated. He was a cousin of Tirésias Simon Sam, Haiti's president from 1896 to 1902.

Early life and education

Ca ...

and subsequent unrest resulted in President of the United States Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

ordering the invasion of Haiti to protect American business interests on 28 July 1915. Six weeks later, the United States seized control of Haiti's customs

Customs is an authority or agency in a country responsible for collecting tariffs and for controlling the flow of goods, including animals, transports, personal effects, and hazardous items, into and out of a country. Traditionally, customs ...

houses, administrative institutions, banks and the national treasury, with the United States using a total of forty percent of Haiti's national income to repay debts to American and French banks for the next nineteen years until 1934. Weinstein, Segal 1984, p. 29. In 1922, BNRH was completely acquired by National City Bank, its headquarters was moved to New York City and Haiti's debt to France was moved to be paid to American investors. Under U.S. government control, a total of forty percent of Haiti's national income was designated to repay debts to American and French banks. Haiti would pay its final indemnity remittance to National City Bank in 1947, with the United Nations reporting that at that time, Haitians were "often close to the starvation level".

Aftermath

According to ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'', the payments cost Haiti much of its development potential, removing about $21 to 115 billion of growth from Haiti – or about one to eight times the nation's total economy – over two centuries according to calculations conducted by fifteen prominent economists. The history of Haiti's indemnity is not taught as part of education in France

Education in France is organized in a highly centralized manner, with many subdivisions. It is divided into the three stages of primary education (''enseignement primaire''), secondary education (''enseignement secondaire''), and higher educatio ...

. Aristocratic French families have also forgotten that their families profited from the debt payments of Haiti. President of France

The president of France, officially the president of the French Republic (french: Président de la République française), is the executive head of state of France, and the commander-in-chief of the French Armed Forces. As the presidency i ...

François Hollande

François Gérard Georges Nicolas Hollande (; born 12 August 1954) is a French politician who served as President of France from 2012 to 2017. He previously was First Secretary of the Socialist Party (PS) from 1997 to 2008, Mayor of Tulle from ...

would eventually describe the money paid by Haiti to France as "the ransom of independence" and in 2016, the Parliament of France

The French Parliament (french: Parlement français) is the bicameral legislature of the French Republic, consisting of the Senate () and the National Assembly (). Each assembly conducts legislative sessions at separate locations in Paris: ...

repealed the 1825 ordinance in a symbolic gesture.

Reparation requests

Aristide government

In 2003,President of Haiti

The president of Haiti ( ht, Prezidan peyi Ayiti, french: Président d'Haïti), officially called the president of the Republic of Haiti (french: link=no, Président de la République d'Haïti, ht, link=no, Prezidan Repiblik Ayiti), is the head ...

Jean-Bertrand Aristide

Jean-Bertrand Aristide (born 15 July 1953) is a Haitian former Salesian priest and politician who became Haiti's first democratically elected president. A proponent of liberation theology, Aristide was appointed to a parish in Port-au-Prince in ...

demanded that France pay Haiti over 21 billion U.S. dollars, what he said was the equivalent in today's money of the 90 million gold francs Haiti was forced to pay Paris after winning its freedom from France. French and Haitian officials later claimed to ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'' that Aristide's calls for reparations led to French and Haitian officials collaborating with the United States on removing Aristide because France feared that discussions of reparations would set a precedent for other former colonies, such as Algeria

)

, image_map = Algeria (centered orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Algiers

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, relig ...

.

In February 2004, a coup d'état

A coup d'état (; French for 'stroke of state'), also known as a coup or overthrow, is a seizure and removal of a government and its powers. Typically, it is an illegal seizure of power by a political faction, politician, cult, rebel group, m ...

occurred against President Aristide. The United Nations Security Council

The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) is one of the Organs of the United Nations, six principal organs of the United Nations (UN) and is charged with ensuring international security, international peace and security, recommending the admi ...

, of which France is a permanent member, rejected a 26 February 2004, appeal from the Caribbean Community

The Caribbean Community (CARICOM or CC) is an intergovernmental organization that is a political and economic union of 15 member states (14 nation-states and one dependency) throughout the Caribbean. They have primary objectives to promote econom ...

(CARICOM) for international peacekeeping forces to be sent into its member state Haiti. However, the Security Council voted unanimously to send troops into Haiti three days later, just hours after Aristide's controversial resignation. The provisional prime minister Gerard Latortue

Gerard is a masculine forename of Proto-Germanic origin, variations of which exist in many Germanic and Romance languages. Like many other early Germanic names, it is dithematic, consisting of two meaningful constituents put together. In this ca ...

who assumed office after the coup would later rescind the reparations demand, calling it "foolish" and "illegal".

Myrtha Desulme, chairperson of the Haiti-Jamaica Exchange Committee, told IPS

IPS, ips, or iPS may refer to:

Science and technology Biology and medicine

* ''Ips'' (genus), a genus of bark beetle

* Induced pluripotent stem cell or iPS cells

* Intermittent photic stimulation, a neuroimaging technique

* Intraparietal sulcus, ...

, "I believe that he call for reparationscould have something to do with it, because they rance

Rance may refer to:

Places

* Rance (river), northwestern France

* Rancé, a commune in eastern France, near Lyon

* Ranče, a small settlement in Slovenia

* Rance, Wallonia, part of the municipality of Sivry-Rance

** Rouge de Rance, a Devonian ...

were definitely not happy about it, and made some very hostile comments... I believe that he did have grounds for that demand, because that is what started the downfall of Haiti."

2010 earthquake

Following the2010 Haiti earthquake

A disaster, catastrophic Moment magnitude scale, magnitude 7.0 Mw earthquake struck Haiti at 16:53 local time (21:53 UTC) on Tuesday, 12 January 2010. The epicenter was near the town of Léogâne, Ouest (department), Ouest department, a ...

, the French foreign ministry made a formal request to the Paris Club

The Paris Club (french: Club de Paris) is a group of officials from major creditor countries whose role is to find co-ordinated and sustainable solutions to the payment difficulties experienced by debtor countries. As debtor countries undertake ...

on 17 January 2010 to completely cancel Haiti's external debt. A number of commentators, for example The New York Times’ Matt Apuzzo, Selam Gebrekidan, Constant Méheut, and Catherine Porter, analyze how Haiti’s current troubles stem from its colonial past drawing references from the early 19th-century indemnity demand and how it had severely depleted the Haitian government's treasury and economic capabilities.

Gallery

Copies of the ordinance

Images Related to the Debt Story

"His Majesty, Charles X, The Beloved, recognizing

the Independence '' of Saint-Domingue''

See also

* Chilean independence debt *External debt of Haiti

The external debt of Haiti is a notable and controversial national debt which mostly stems from an outstanding 1825 compensation to former slavers of the French colonial empire and later 20th century's corruptions.

French Revolutionary and Napo ...

* France–Haiti relations

* Foreign relations of Haiti

Haiti was one of the original members of the League of Nations, and was one of the original members of the United Nations and several of its specialized and related agencies. It is also a founding member of the Organization of American States. ...

References

{{reflistExternal links

France Urged to Pay $40 Billion to Haiti in Reparations for "Independence Debt"

– video report by ''

Democracy Now!

''Democracy Now!'' is an hour-long American TV, radio, and Internet news program hosted by journalists Amy Goodman (who also acts as the show's executive producer), Juan González, and Nermeen Shaikh. The show, which airs live each weekday at ...

''

Economy of Haiti

History of Haiti

France–Haiti relations

Reparations for slavery

Third World debt cancellation activism