HM Bark Endeavour on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

HMS ''Endeavour'' was a British

On 27 May 1768, Cook took command of ''Earl of Pembroke'', valued in March at £2,307. 5s. 6d. but ultimately purchased for £2,840. 10s. 11d. and assigned for use in the Society's expedition. She was refitted at

On 27 May 1768, Cook took command of ''Earl of Pembroke'', valued in March at £2,307. 5s. 6d. but ultimately purchased for £2,840. 10s. 11d. and assigned for use in the Society's expedition. She was refitted at

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against Fr ...

research vessel that Lieutenant James Cook

James Cook (7 November 1728 Old Style date: 27 October – 14 February 1779) was a British explorer, navigator, cartographer, and captain in the British Royal Navy, famous for his three voyages between 1768 and 1779 in the Pacific Ocean and ...

commanded to Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands. With an area of , Australia is the largest country by ...

and New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island coun ...

on his first voyage of discovery from 1768 to 1771.

She was launched in 1764 as the collier ''Earl of Pembroke'', with the Navy purchasing her in 1768 for a scientific mission to the Pacific Ocean and to explore the seas for the surmised '' Terra Australis Incognita'' or "unknown southern land". Commissioned as His Majesty's Bark

Bark may refer to:

* Bark (botany), an outer layer of a woody plant such as a tree or stick

* Bark (sound), a vocalization of some animals (which is commonly the dog)

Places

* Bark, Germany

* Bark, Warmian-Masurian Voivodeship, Poland

Arts, e ...

''Endeavour'', she departed Plymouth

Plymouth () is a port city status in the United Kingdom, city and unitary authority in South West England. It is located on the south coast of Devon, approximately south-west of Exeter and south-west of London. It is bordered by Cornwall to ...

in August 1768, rounded Cape Horn

Cape Horn ( es, Cabo de Hornos, ) is the southernmost headland of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago of southern Chile, and is located on the small Hornos Island. Although not the most southerly point of South America (which are the Diego Ramí ...

and reached Tahiti

Tahiti (; Tahitian ; ; previously also known as Otaheite) is the largest island of the Windward group of the Society Islands in French Polynesia. It is located in the central part of the Pacific Ocean and the nearest major landmass is Austra ...

in time to observe the 1769 transit of Venus

frameless, upright=0.5

A transit of Venus across the Sun takes place when the planet Venus passes directly between the Sun and a superior planet, becoming visible against (and hence obscuring a small portion of) the solar disk. During a tr ...

across the Sun. She then set sail into the largely uncharted ocean to the south, stopping at the islands of Huahine

Huahine is an island located among the Society Islands, in French Polynesia, an overseas territory of France in the Pacific Ocean. It is part of the Leeward Islands group ''(Îles sous le Vent).'' At the 2017 census it had a population of 6,075. ...

, Bora Bora

Bora Bora (French: ''Bora-Bora''; Tahitian: ''Pora Pora'') is an island group in the Leeward Islands. The Leeward Islands comprise the western part of the Society Islands of French Polynesia, which is an overseas collectivity of the French R ...

, and Raiatea

Raiatea or Ra'iatea ( Tahitian: ''Ra‘iātea'') is the second largest of the Society Islands, after Tahiti, in French Polynesia. The island is widely regarded as the "centre" of the eastern islands in ancient Polynesia and it is likely that th ...

west of Tahiti to allow Cook to claim them for Great Britain. In September 1769, she anchored off New Zealand, becoming the first European vessel to reach the islands since Abel Tasman

Abel Janszoon Tasman (; 160310 October 1659) was a Dutch seafarer, explorer, and merchant, best known for his voyages of 1642 and 1644 in the service of the Dutch East India Company (VOC). He was the first known European explorer to reach New ...

's ''Heemskerck'' 127 years earlier.

In April 1770, ''Endeavour'' became the first European ship to reach the east coast of Australia, with Cook going ashore at what is now known as Botany Bay

Botany Bay ( Dharawal: ''Kamay''), an open oceanic embayment, is located in Sydney, New South Wales, Australia, south of the Sydney central business district. Its source is the confluence of the Georges River at Taren Point and the Cook ...

. ''Endeavour'' then sailed north along the Australian coast. She narrowly avoided disaster after running aground on the Great Barrier Reef

The Great Barrier Reef is the world's largest coral reef system composed of over 2,900 individual reefs and 900 islands stretching for over over an area of approximately . The reef is located in the Coral Sea, off the coast of Queensland, A ...

, and Cook had to throw her guns overboard to lighten her. ''Endeavour'' was beached on the Australian mainland for seven weeks to permit rudimentary repairs to her hull. Resuming her voyage, she limped into port in Batavia in October 1770, her crew sworn to secrecy about the lands that they had visited. From Batavia ''Endeavour'' continued westward, rounded the Cape of Good Hope

The Cape of Good Hope ( af, Kaap die Goeie Hoop ) ;''Kaap'' in isolation: pt, Cabo da Boa Esperança is a rocky headland on the Atlantic coast of the Cape Peninsula in South Africa.

A common misconception is that the Cape of Good Hope is ...

on 13 March 1771 and reached the English port of Dover

Dover () is a town and major ferry port in Kent, South East England. It faces France across the Strait of Dover, the narrowest part of the English Channel at from Cap Gris Nez in France. It lies south-east of Canterbury and east of Maids ...

on 12 July, having been at sea for nearly three years.

The ship was largely forgotten after her Pacific voyage, spending the next three years hauling troops and cargo to and from the Falkland Islands

The Falkland Islands (; es, Islas Malvinas, link=no ) is an archipelago in the South Atlantic Ocean on the Patagonian Shelf. The principal islands are about east of South America's southern Patagonian coast and about from Cape Dubouze ...

. She was renamed in 1775 after being sold into private hands, and used to transport timber from the Baltic. Rehired as a British troop transport during the American War of Independence

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

, she was finally scuttled

Scuttling is the deliberate sinking of a ship. Scuttling may be performed to dispose of an abandoned, old, or captured vessel; to prevent the vessel from becoming a navigation hazard; as an act of self-destruction to prevent the ship from being ...

in a blockade of Narragansett Bay

Narragansett Bay is a bay and estuary on the north side of Rhode Island Sound covering , of which is in Rhode Island. The bay forms New England's largest estuary, which functions as an expansive natural harbor and includes a small archipelago. Sm ...

, Rhode Island

Rhode Island (, like ''road'') is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is the List of U.S. states by area, smallest U.S. state by area and the List of states and territories of the United States ...

in 1778. Historical evidence indicates the ship was sunk just north of Goat Island Goat Island (or Goat Islands) may refer to:

Arts

* Goat Island (performance group), a Chicago-based company

* ''Goat Island'' (play), ''Delitto all'isola delle capre'', by Ugo Betti

Places

Australia

* Goat Island (Port Jackson) in Sydney Harbou ...

in Newport Harbor, along with four other British transports.

Relics from ''Endeavour'' are displayed at maritime museums worldwide, including an anchor and six of her cannon. A replica of ''Endeavour'' was launched in 1994 and is berthed alongside the Australian National Maritime Museum in Sydney Harbour. The NASA

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agency of the US federal government responsible for the civil space program, aeronautics research, and space research.

NASA was established in 1958, succeedin ...

Space Shuttle ''Endeavour'' was named after this ship, as was the command module of Apollo 15

Apollo 15 (July 26August 7, 1971) was the ninth crewed mission in the United States' Apollo program and the fourth to land on the Moon. It was the first J mission, with a longer stay on the Moon and a greater focus on science than ear ...

, which took a small piece of wood from Cook's ship into space, and the SpaceX

Space Exploration Technologies Corp. (SpaceX) is an American spacecraft manufacturer, launcher, and a satellite communications corporation headquartered in Hawthorne, California. It was founded in 2002 by Elon Musk with the stated goal o ...

Crew Dragon

Dragon 2 is a class of partially reusable spacecraft developed and manufactured by American aerospace manufacturer SpaceX, primarily for flights to the International Space Station (ISS). SpaceX has also launched private missions such as Ins ...

capsule C206 was christened ''Endeavour'' during Demo-2. The ship is also depicted on the New Zealand fifty-cent coin.

Construction

''Endeavour'' was originally the merchant collier ''Earl of Pembroke'', built by Thomas Fishburn for Thomas Millner, launched in June 1764 from the coal and whaling port ofWhitby

Whitby is a seaside town, port and civil parish in the Scarborough borough of North Yorkshire, England. Situated on the east coast of Yorkshire at the mouth of the River Esk, Whitby has a maritime, mineral and tourist heritage. Its East Cl ...

in the North Riding of Yorkshire

The North Riding of Yorkshire is a subdivision of Yorkshire, England, alongside York, the East Riding and West Riding. The riding's highest point is at Mickle Fell with 2,585 ft (788 metres).

From the Restoration it was used ...

. She was a type known locally as the 'Whitby Cat'. She was ship-rigged

A full-rigged ship or fully rigged ship is a sailing vessel's sail plan with three or more masts, all of them square-rigged. A full-rigged ship is said to have a ship rig or be ship-rigged. Such vessels also have each mast stepped in three seg ...

and sturdily built with a broad, flat bow, a square stern

The stern is the back or aft-most part of a ship or boat, technically defined as the area built up over the sternpost, extending upwards from the counter rail to the taffrail. The stern lies opposite the bow, the foremost part of a ship. Or ...

, and a long box-like body with a deep hold

Hold may refer to:

Physical spaces

* Hold (ship), interior cargo space

* Baggage hold, cargo space on an airplane

* Stronghold, a castle or other fortified place

Arts, entertainment, and media

* Hold (musical term), a pause, also called a Ferma ...

.Hosty and Hundley 2003, p. 41

A flat-bottomed design made her well-suited to sailing in shallow waters and allowed her to be beached for loading and unloading of cargo and for basic repairs without requiring a dry dock

A dry dock (sometimes drydock or dry-dock) is a narrow basin or vessel that can be flooded to allow a load to be floated in, then drained to allow that load to come to rest on a dry platform. Dry docks are used for the construction, maintenance, ...

. Her hull

Hull may refer to:

Structures

* Chassis, of an armored fighting vehicle

* Fuselage, of an aircraft

* Hull (botany), the outer covering of seeds

* Hull (watercraft), the body or frame of a ship

* Submarine hull

Mathematics

* Affine hull, in affi ...

, internal floors, and futtocks were built from traditional white oak

The genus ''Quercus'' contains about 500 species, some of which are listed here. The genus, as is the case with many large genera, is divided into subgenera and sections. Traditionally, the genus ''Quercus'' was divided into the two subgenera ''C ...

, her keel

The keel is the bottom-most longitudinal structural element on a vessel. On some sailboats, it may have a hydrodynamic and counterbalancing purpose, as well. As the laying down of the keel is the initial step in the construction of a ship, in Br ...

and stern post from elm, and her masts from pine

A pine is any conifer tree or shrub in the genus ''Pinus'' () of the family (biology), family Pinaceae. ''Pinus'' is the sole genus in the subfamily Pinoideae. The World Flora Online created by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew and Missouri Botanic ...

and fir. Plans of the ship also show a double keelson

The keelson or kelson is a reinforcing structural member on top of the keel in the hull of a wooden vessel.

In part V of “Song of Myself”, American poet Walt Whitman

Walter Whitman (; May 31, 1819 – March 26, 1892) was an Ame ...

to lock the keel, floors and frames in place.

There is uncertainty about the height of her standing masts, as surviving diagrams of ''Endeavour'' depict the body of the vessel only, and not the mast plan. While her main and foremast standing spars were standard for her shipyard and era, an annotation on one surviving ship plan in the National Maritime Museum

The National Maritime Museum (NMM) is a maritime museum in Greenwich, London. It is part of Royal Museums Greenwich, a network of museums in the Maritime Greenwich World Heritage Site. Like other publicly funded national museums in the Unite ...

in Greenwich has the mizzen as "16 yards 29 inches" ( m). If correct, this would produce an oddly truncated mast a full shorter than the naval standards of the day. Late twentieth-century research suggests the annotation may be a transcription error with "19 yards 29 inches" ( m) being the true reading. If so, this would more closely conform with both naval standards and the lengths of the other masts.Marquardt 1995, pp. 19–20.

Purchase and refit by the Admiralty

On 16 February 1768, theRoyal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

petitioned King George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of the two kingdoms on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great B ...

to finance a scientific expedition to the Pacific to study and observe the 1769 transit of Venus

frameless, upright=0.5

A transit of Venus across the Sun takes place when the planet Venus passes directly between the Sun and a superior planet, becoming visible against (and hence obscuring a small portion of) the solar disk. During a tr ...

across the sun. Royal approval was granted for the expedition, and the Admiralty

Admiralty most often refers to:

*Admiralty, Hong Kong

*Admiralty (United Kingdom), military department in command of the Royal Navy from 1707 to 1964

*The rank of admiral

*Admiralty law

Admiralty can also refer to:

Buildings

* Admiralty, Traf ...

elected to combine the scientific voyage with a confidential mission to search the south Pacific for signs of the postulated continent ''Terra Australis Incognita'' (or "unknown southern land").

The Royal Society suggested command be given to Scottish geographer Alexander Dalrymple

Alexander Dalrymple FRS (24 July 1737 – 19 June 1808) was a Scottish geographer and the first Hydrographer of the British Admiralty. He was the main proponent of the theory that there existed a vast undiscovered continent in the South P ...

, whose acceptance was conditional on a brevet commission as a captain in the Royal Navy. First Lord of the Admiralty

The First Lord of the Admiralty, or formally the Office of the First Lord of the Admiralty, was the political head of the English and later British Royal Navy. He was the government's senior adviser on all naval affairs, responsible for the di ...

Edward Hawke

Edward Hawke, 1st Baron Hawke, KB, PC (21 February 1705 – 17 October 1781), of Scarthingwell Hall in the parish of Towton, near Tadcaster, Yorkshire, was a Royal Navy officer. As captain of the third-rate , he took part in the Battle of T ...

refused, going so far as to say he would rather cut off his right hand than give command of a navy vessel to someone not educated as a seaman., editor Robert Kerr's introduction footnote 3 In refusing Dalrymple's command, Hawke was influenced by previous insubordination aboard the sloop in 1698, when naval officers had refused to take orders from civilian commander Dr. Edmond Halley

Edmond (or Edmund) Halley (; – ) was an English astronomer, mathematician and physicist. He was the second Astronomer Royal in Britain, succeeding John Flamsteed in 1720.

From an observatory he constructed on Saint Helena in 1676–77, H ...

. The impasse was broken when the Admiralty proposed James Cook

James Cook (7 November 1728 Old Style date: 27 October – 14 February 1779) was a British explorer, navigator, cartographer, and captain in the British Royal Navy, famous for his three voyages between 1768 and 1779 in the Pacific Ocean and ...

, a naval officer with a background in mathematics and cartography

Cartography (; from grc, χάρτης , "papyrus, sheet of paper, map"; and , "write") is the study and practice of making and using maps. Combining science, aesthetics and technique, cartography builds on the premise that reality (or an i ...

. Acceptable to both parties, Cook was promoted to Lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations.

The meaning of lieutenant differs in different militaries (see comparative military ranks), but it is often ...

and named as commander of the expedition.

On 27 May 1768, Cook took command of ''Earl of Pembroke'', valued in March at £2,307. 5s. 6d. but ultimately purchased for £2,840. 10s. 11d. and assigned for use in the Society's expedition. She was refitted at

On 27 May 1768, Cook took command of ''Earl of Pembroke'', valued in March at £2,307. 5s. 6d. but ultimately purchased for £2,840. 10s. 11d. and assigned for use in the Society's expedition. She was refitted at Deptford

Deptford is an area on the south bank of the River Thames in southeast London, within the London Borough of Lewisham. It is named after a Ford (crossing), ford of the River Ravensbourne. From the mid 16th century to the late 19th it was home ...

by the dock's master shipwright Adam Hayes

Adam Hayes (1710–1785) was an 18th century shipbuilder to the Royal Navy. A great number of his models survive.

He was responsible for the selection of the ship the "Earl of Pembroke" and was the wright who converted it into HMS Endeavour ...

on the River Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the The Isis, River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the Longest rivers of the United Kingdom, se ...

for the sum of £2,294, almost the price of the ship itself. The hull was sheathed and caulked to protect against shipworm

The shipworms are marine bivalve molluscs in the family Teredinidae: a group of saltwater clams with long, soft, naked bodies. They are notorious for boring into (and commonly eventually destroying) wood that is immersed in sea water, including ...

, and a third internal deck installed to provide cabins, a powder magazine and storerooms.Hosty and Hundley 2003, p. 61 The new cabins provided around of floorspace apiece being allocated to Cook and the Royal Society representatives: naturalist Joseph Banks

Sir Joseph Banks, 1st Baronet, (19 June 1820) was an English naturalist, botanist, and patron of the natural sciences.

Banks made his name on the 1766 natural-history expedition to Newfoundland and Labrador. He took part in Captain James ...

, Banks' assistants Daniel Solander

Daniel Carlsson Solander or Daniel Charles Solander (19 February 1733 – 13 May 1782) was a Swedish naturalist and an apostle of Carl Linnaeus.

Solander was the first university-educated scientist to set foot on Australian soil.

Biography ...

and Herman Spöring

Herman may refer to:

People

* Herman (name), list of people with this name

* Saint Herman (disambiguation)

* Peter Noone (born 1947), known by the mononym Herman

Places in the United States

* Herman, Arkansas

* Herman, Michigan

* Herman, Minnes ...

, astronomer Charles Green, and artists Sydney Parkinson and Alexander Buchan.Marquardt 1995, p. 18 These cabins encircled the officer's mess. The Great Cabin at the rear of the deck was designed as a workroom for Cook and the Royal Society. On the rear lower deck, cabins facing on to the mate's mess were assigned to Lieutenants Zachary Hickes and John Gore, ship's surgeon William Monkhouse, the gunner Stephen Forwood, ship's master Robert Molyneux, and the captain's clerk Richard Orton. The adjoining open mess deck provided sleeping and living quarters for the marines and crew, and additional storage space.

A longboat

A longboat is a type of ship's boat that was in use from ''circa'' 1500 or before. Though the Royal Navy replaced longboats with launches from 1780, examples can be found in merchant ships after that date. The longboat was usually the largest boa ...

, pinnace

Pinnace may refer to:

* Pinnace (ship's boat), a small vessel used as a tender to larger vessels among other things

* Full-rigged pinnace

The full-rigged pinnace was the larger of two types of vessel called a pinnace in use from the sixteenth ...

and yawl

A yawl is a type of boat. The term has several meanings. It can apply to the rig (or sailplan), to the hull type or to the use which the vessel is put.

As a rig, a yawl is a two masted, fore and aft rigged sailing vessel with the mizzen mast p ...

were provided as ship's boats, though the longboat was rotten having to be rebuilt and painted with white lead

White lead is the basic lead carbonate 2PbCO3·Pb(OH)2. It is a complex salt, containing both carbonate and hydroxide ions. White lead occurs naturally as a mineral, in which context it is known as hydrocerussite, a hydrate of cerussite. It was ...

before it could be brought aboard.Hough 1994, p. 56. These were accompanied by two privately owned skiffs, one belonging to the boatswain

A boatswain ( , ), bo's'n, bos'n, or bosun, also known as a deck boss, or a qualified member of the deck department, is the most senior rate of the deck department and is responsible for the components of a ship's hull. The boatswain supervis ...

John Gathrey, and the other to Banks. The ship was also equipped with a set of sweeps to allow her to be rowed forward if becalmed or demasted. The refitted vessel was commissioned as His Majesty's Bark

Bark may refer to:

* Bark (botany), an outer layer of a woody plant such as a tree or stick

* Bark (sound), a vocalization of some animals (which is commonly the dog)

Places

* Bark, Germany

* Bark, Warmian-Masurian Voivodeship, Poland

Arts, e ...

''the Endeavour'', to distinguish her from the 4-gun cutter .

On 21 July 1768, ''Endeavour'' sailed to Gallion's Reach to take on armaments to protect her against potentially hostile Pacific island natives. Ten 4-pounder cannon were brought aboard, six of which were mounted on the upper deck with the remainder stowed in the hold. Twelve swivel guns were also supplied, and fixed to posts along the quarterdeck, sides and bow. The ship departed for Plymouth

Plymouth () is a port city status in the United Kingdom, city and unitary authority in South West England. It is located on the south coast of Devon, approximately south-west of Exeter and south-west of London. It is bordered by Cornwall to ...

on 30 July, for provisioning and crew boarding of 85, including 12 Royal Marines

The Corps of Royal Marines (RM), also known as the Royal Marines Commandos, are the UK's special operations capable commando force, amphibious warfare, amphibious light infantry and also one of the :Fighting Arms of the Royal Navy, five fighti ...

. Cook also ordered that twelve tons of pig iron

Pig iron, also known as crude iron, is an intermediate product of the iron industry in the production of steel which is obtained by smelting iron ore in a blast furnace. Pig iron has a high carbon content, typically 3.8–4.7%, along with ...

be brought on board as sailing ballast

Ballast is used in ships to provide moment to resist the lateral forces on the hull. Insufficiently ballasted boats tend to tip or heel excessively in high winds. Too much heel may result in the vessel capsizing. If a sailing vessel needs to vo ...

.

Service history

Voyage of discovery

Outward voyage

''Endeavour'' departed Plymouth on 26 August 1768, carrying 18 months of provisions for 94 people. Livestock on board included pigs, poultry, two greyhounds and a milking goat. The first port of call wasFunchal

Funchal () is the largest city, the municipal seat and the capital of Portugal's Autonomous Region of Madeira, bordered by the Atlantic Ocean. The city has a population of 105,795, making it the sixth largest city in Portugal. Because of its hig ...

in the Madeira Islands

)

, anthem = ( en, "Anthem of the Autonomous Region of Madeira")

, song_type = Regional anthem

, image_map=EU-Portugal_with_Madeira_circled.svg

, map_alt=Location of Madeira

, map_caption=Location of Madeira

, subdivision_type=Sovereign st ...

, which ''Endeavour'' reached on 12 September. The ship was recaulked and painted, and fresh vegetables, beef and water were brought aboard for the next leg of the voyage.Hough 1994, pp. 75–76 While in port, an accident cost the life of master's mate Robert Weir, who became entangled in the anchor cable and was dragged overboard when the anchor was released. To replace him, Cook pressed a sailor from an American sloop anchored nearby.

''Endeavour'' then continued south along the coast of Africa and across the Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe ...

to South America, arriving in Rio de Janeiro

Rio de Janeiro ( , , ; literally 'River of January'), or simply Rio, is the capital of the state of the same name, Brazil's third-most populous state, and the second-most populous city in Brazil, after São Paulo. Listed by the GaWC as a b ...

on 13 November 1768. Fresh food and water were brought aboard and the ship departed for Cape Horn

Cape Horn ( es, Cabo de Hornos, ) is the southernmost headland of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago of southern Chile, and is located on the small Hornos Island. Although not the most southerly point of South America (which are the Diego Ramí ...

, which she reached during stormy weather on 13 January 1769. Attempts to round the Cape over the next two days were unsuccessful, and ''Endeavour'' was repeatedly driven back by wind, rain and contrary tides. Cook noted that the seas off the Cape were large enough to regularly submerge the bow of the ship as she rode down from the crests of waves. At last, on 16 January the wind eased and the ship was able to pass the Cape and anchor in the Bay of Good Success on the Pacific coast.Beaglehole 1968, pp. 41–44 The crew were sent to collect wood and water, while Banks and his team gathered hundreds of plant specimens from along the icy shore. On 17 January two of Banks' servants died from cold while attempting to return to the ship during a heavy snowstorm.

''Endeavour'' resumed her voyage on 21 January 1769, heading west-northwest into warmer weather. She reached Tahiti

Tahiti (; Tahitian ; ; previously also known as Otaheite) is the largest island of the Windward group of the Society Islands in French Polynesia. It is located in the central part of the Pacific Ocean and the nearest major landmass is Austra ...

on 10 April, where she remained for the next three months. The transit of Venus across the Sun occurred on 3 June, and was observed and recorded by astronomer Charles Green from ''Endeavour'' deck.

Pacific exploration

The transit observed, ''Endeavour'' departed Tahiti on 13 July and headed northwest to allow Cook to survey and name theSociety Islands

The Society Islands (french: Îles de la Société, officially ''Archipel de la Société;'' ty, Tōtaiete mā) are an archipelago located in the South Pacific Ocean. Politically, they are part of French Polynesia, an overseas country of the F ...

.Rigby and van der Merwe 2002, p. 34 Landfall was made at Huahine, Raiatea and Borabora, providing opportunities for Cook to claim each of them as British territories. An attempt to land the pinnace on the Austral Island of Rurutu

Rūrutu is the northernmost island in the Austral archipelago of French Polynesia, and the name of a commune consisting solely of that island. It is situated south of Tahiti. Its land area is .

In October 1769, ''Endeavour'' reached the coastline of New Zealand, becoming the first European vessel to do so since

For the next four months, Cook charted the coast of Australia, heading generally northward. Just before 11 pm on 11 June 1770, the ship struck a reef,Beaglehole 1968, pp. 343–345 today called Endeavour Reef, within the

For the next four months, Cook charted the coast of Australia, heading generally northward. Just before 11 pm on 11 June 1770, the ship struck a reef,Beaglehole 1968, pp. 343–345 today called Endeavour Reef, within the  ''Endeavour'' then resumed her course northward and parallel to the reef, the crew looking for a safe harbour in which to make repairs. On 13 June, the ship came to a broad watercourse that Cook named the

''Endeavour'' then resumed her course northward and parallel to the reef, the crew looking for a safe harbour in which to make repairs. On 13 June, the ship came to a broad watercourse that Cook named the

''Endeavour'' then resumed her voyage westward along the coast, picking a path through intermittent shoals and reefs with the help of the pinnace, which was rowed ahead to test the water depth. By 26 August she was out of sight of land, and had entered the open waters of the

''Endeavour'' then resumed her voyage westward along the coast, picking a path through intermittent shoals and reefs with the help of the pinnace, which was rowed ahead to test the water depth. By 26 August she was out of sight of land, and had entered the open waters of the

The surrender of British General

The surrender of British General

In January 1988, to commemorate the

In January 1988, to commemorate the

In today's terms, this equates to a valuation for ''Endeavour'' of approximately £265,000 and a purchase price of £326,400.

Provisions loaded at the outset of the voyage included 6,000 pieces of pork and 4,000 of beef, nine tons of bread, five tons of flour, three tons of sauerkraut, one ton of raisins and sundry quantities of cheese, salt, peas, oil, sugar and oatmeal. Alcohol supplies consisted of 250 barrels of beer, 44 barrels of brandy and 17 barrels of rum.

The pressed man was John Thurman, born in New York but a British subject and therefore eligible for involuntary impressment aboard a Royal Navy vessel. Thurman journeyed with ''Endeavour'' to Tahiti where he was promoted to the position of sailmaker's assistant, and then to New Zealand and Australia. He died of disease on 3 February 1771, during the voyage between Batavia and Cape Town.

Some of ''Endeavour''s crew also contracted an unspecified lung infection. Cook noted that disease of various kinds had broken out aboard every ship berthed in Batavia at the time, and that "this seems to have been a year of General sickness over most parts of India" and in England.Beaglehole 1968, p. 441

A number of British vessels were sunk in local waters in the days leading up to the 29–30 August 1778, Battle of Rhode Island. These were the four Royal Navy frigates on 5 August along the coast of Aquidneck Island north of Newport: ''Juno'' 32, ''

The abbreviation "HMS" was not in use at the time, but "His/Her Majesty's Ship" was, and this is a valid if less precise way to refer to the ''Endeavour''. "HMS" is commonly used retroactively in modern sources. James Cook in his own documentation of the voyage referred to it as "His Britannick Majesty's Bark" but occasionally as "His Britannick Majesty's Ship".

A table of the crew of Cook's Three Voyages 1768-1779

CaptainCookSociety.com

Flyer from the ''Australian National Maritime Museum'' about the HMB ''Endeavour'' replica

(PDF)

''Endeavour'' runs aground

, Pictures and information about the discovery of ''Endeavours ballast and cannon on the ocean floor off Queensland, Australia, in 1969,

Abel Tasman

Abel Janszoon Tasman (; 160310 October 1659) was a Dutch seafarer, explorer, and merchant, best known for his voyages of 1642 and 1644 in the service of the Dutch East India Company (VOC). He was the first known European explorer to reach New ...

's ''Heemskerck'' in 1642. Unfamiliar with such ships, the Māori people

The Māori (, ) are the indigenous Polynesian people of mainland New Zealand (). Māori originated with settlers from East Polynesia, who arrived in New Zealand in several waves of canoe voyages between roughly 1320 and 1350. Over severa ...

at Cook's first landing point in Poverty Bay

Poverty Bay (Māori: ''Tūranganui-a-Kiwa'') is the largest of several small bays on the east coast of New Zealand's North Island to the north of Hawke Bay. It stretches for from Young Nick's Head in the southwest to Tuaheni Point in the nor ...

thought the ship was a floating island, or a gigantic bird from their mythical homeland of Hawaiki

In Polynesian mythology, (also rendered as in Cook Islands Māori, in Samoan, in Tahitian, in Hawaiian) is the original home of the Polynesians, before dispersal across Polynesia. It also features as the underworld in many Māori stories. ...

. ''Endeavour'' spent the next six months sailing close to shore, while Cook mapped the coastline and concluded that New Zealand comprised two large islands and was not the hoped-for ''Terra Australis''. In March 1770, the longboat from ''Endeavour'' carried Cook ashore to allow him to formally proclaim British sovereignty over New Zealand. On his return, ''Endeavour'' resumed her voyage westward, her crew sighting the east coast of Australia on 19 April. On 29 April, she became the first European vessel to make landfall on the east coast of Australia, when Cook landed one of the ship's boats on the southern shore of what is now known as Botany Bay

Botany Bay ( Dharawal: ''Kamay''), an open oceanic embayment, is located in Sydney, New South Wales, Australia, south of the Sydney central business district. Its source is the confluence of the Georges River at Taren Point and the Cook ...

, New South Wales

)

, nickname =

, image_map = New South Wales in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of New South Wales in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, es ...

.

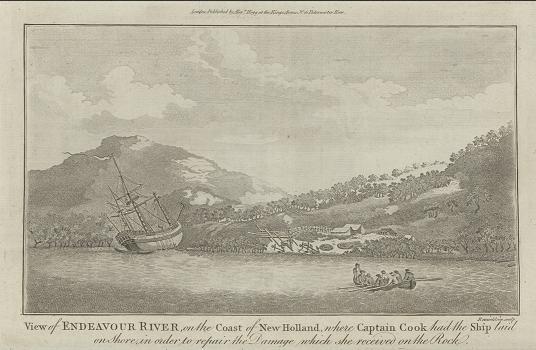

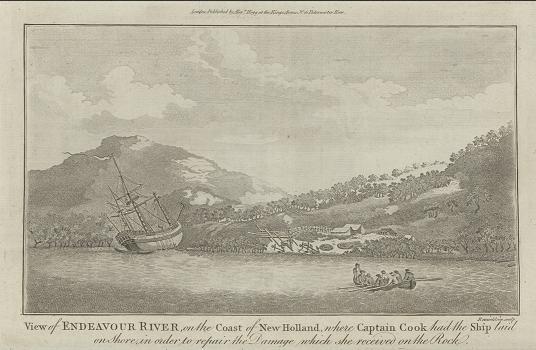

Shipwreck

For the next four months, Cook charted the coast of Australia, heading generally northward. Just before 11 pm on 11 June 1770, the ship struck a reef,Beaglehole 1968, pp. 343–345 today called Endeavour Reef, within the

For the next four months, Cook charted the coast of Australia, heading generally northward. Just before 11 pm on 11 June 1770, the ship struck a reef,Beaglehole 1968, pp. 343–345 today called Endeavour Reef, within the Great Barrier Reef

The Great Barrier Reef is the world's largest coral reef system composed of over 2,900 individual reefs and 900 islands stretching for over over an area of approximately . The reef is located in the Coral Sea, off the coast of Queensland, A ...

system. The sails were immediately taken down, a kedging anchor set and an unsuccessful attempt was made to drag the ship back to open water. The reef ''Endeavour'' had struck rose so steeply from the seabed that although the ship was hard aground, Cook measured depths up to less than one ship's length away.

Cook then ordered that the ship be lightened to help her float off the reef. Iron and stone ballast, spoiled stores and all but four of the ship's guns were thrown overboard, and the ship's drinking water pumped out. The crew attached buoy

A buoy () is a floating device that can have many purposes. It can be anchored (stationary) or allowed to drift with ocean currents.

Types

Navigational buoys

* Race course marker buoys are used for buoy racing, the most prevalent form of y ...

s to the discarded guns with the intention of retrieving them later,Parkin 2003, p. 317 but this proved impractical. Every man on board took turns on the pumps, including Cook and Banks.

When, by Cook's reckoning, about of equipment had been thrown overboard, on the next high tide a second unsuccessful attempt was made to pull the ship free. In the afternoon of 12 June, the longboat carried out two large bower anchors, and block and tackle were rigged to the anchor chains to allow another attempt on the evening high tide. The ship had started to take on water through a hole in her hull. Although the leak would certainly increase once off the reef, Cook decided to risk the attempt and at 10:20 pm the ship was floated on the tide and successfully drawn off.Beaglehole 1968, pp. 345–346 The anchors were retrieved, except for one which could not be freed from the seabed and had to be abandoned.

As expected the leak increased once the ship was off the reef, and all three working pumps had to be continually manned. A mistake occurred in sounding the depth of water in the hold, when a new man measured the length of a sounding line from the outside plank of the hull where his predecessor had used the top of the cross-beams. The mistake suggested the water depth had increased by about between soundings, sending a wave of fear through the ship. As soon as the mistake was realised, redoubled efforts kept the pumps ahead of the leak.

The prospects if the ship sank were grim. The vessel was from shore and the three ship's boats could not carry the entire crew. Despite this, Joseph Banks noted in his journal the calm efficiency of the crew in the face of danger, contrary to stories he had heard of seamen panicking or refusing orders in such circumstances.

Midshipman Jonathon Monkhouse proposed fothering the ship, as he had previously been on a merchant ship which used the technique successfully. He was entrusted with supervising the task, sewing bits of oakum

Oakum is a preparation of tarred fibre used to seal gaps. Its main traditional applications were in shipbuilding, for caulking or packing the joints of timbers in wooden vessels and the deck planking of iron and steel ships; in plumbing, for ...

and wool into an old sail, which was then drawn under the ship to allow water pressure to force it into the hole in the hull. The effort succeeded and soon very little water was entering, allowing the crew to stop two of the three pumps.

''Endeavour'' then resumed her course northward and parallel to the reef, the crew looking for a safe harbour in which to make repairs. On 13 June, the ship came to a broad watercourse that Cook named the

''Endeavour'' then resumed her course northward and parallel to the reef, the crew looking for a safe harbour in which to make repairs. On 13 June, the ship came to a broad watercourse that Cook named the Endeavour River

The Endeavour River ( Guugu Yimithirr: ''Wabalumbaal''), inclusive of the Endeavour River Right Branch, the Endeavour River South Branch, and the Endeavour River North Branch, is a river system located on Cape York Peninsula in Far North Queens ...

. Cook attempted to enter the river mouth, but strong winds and rain prevented ''Endeavour'' from crossing the bar

Bar or BAR may refer to:

Food and drink

* Bar (establishment), selling alcoholic beverages

* Candy bar

* Chocolate bar

Science and technology

* Bar (river morphology), a deposit of sediment

* Bar (tropical cyclone), a layer of cloud

* Bar ( ...

until the morning of 17 June. She grounded briefly on a sand spit but was refloated an hour later and warped into the river proper by early afternoon. The ship was promptly beached on the southern bank and careened to make repairs to the hull. Torn sails and rigging were also replaced and the hull scraped free of barnacles.

An examination of the hull showed that a piece of coral the size of a man's fist had sliced clean through the timbers and then broken off. Surrounded by pieces of oakum from the fother, this coral fragment had helped plug the hole in the hull and preserved the ship from sinking on the reef.Parkin 2003, pp. 335–336

Northward to Batavia

After waiting for the wind, ''Endeavour'' resumed her voyage on the afternoon of 5 August 1770, reaching the northernmost point ofCape York Peninsula

Cape York Peninsula is a large peninsula located in Far North Queensland, Australia. It is the largest unspoiled wilderness in northern Australia.Mittermeier, R.E. et al. (2002). Wilderness: Earth’s last wild places. Mexico City: Agrupación ...

fifteen days later. On 22 August, Cook was rowed ashore to a small coastal island to proclaim British sovereignty over the eastern Australian mainland. Cook christened his landing place Possession Island, and ceremonial volleys of gunfire from the shore and ''Endeavour''s deck marked the occasion.

''Endeavour'' then resumed her voyage westward along the coast, picking a path through intermittent shoals and reefs with the help of the pinnace, which was rowed ahead to test the water depth. By 26 August she was out of sight of land, and had entered the open waters of the

''Endeavour'' then resumed her voyage westward along the coast, picking a path through intermittent shoals and reefs with the help of the pinnace, which was rowed ahead to test the water depth. By 26 August she was out of sight of land, and had entered the open waters of the Torres Strait

The Torres Strait (), also known as Zenadh Kes, is a strait between Australia and the Melanesian island of New Guinea. It is wide at its narrowest extent. To the south is Cape York Peninsula, the northernmost extremity of the Australian mai ...

between Australia and New Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu: ''Niu Gini''; id, Papua, or , historically ) is the world's second-largest island with an area of . Located in Oceania in the southwestern Pacific Ocean, the island is separated from Australia by the wide Torres ...

, earlier navigated by Luis Váez de Torres

Luis is a given name. It is the Spanish form of the originally Germanic name or . Other Iberian Romance languages have comparable forms: (with an accent mark on the i) in Portuguese and Galician, in Aragonese and Catalan, while is archa ...

in 1606. To keep ''Endeavour''s voyages and discoveries secret, Cook confiscated the log books and journals of all on board and ordered them to remain silent about where they had been.

After a three-day layover off the island of Savu

Savu ( id, Sawu, also known as Sabu, Havu, and Hawu) is the largest of a group of three islands, situated midway between Sumba and Rote, west of Timor, in Indonesia's eastern province, East Nusa Tenggara. Ferries connect the islands to Waingapu ...

, ''Endeavour'' sailed on to Batavia, the capital of the Dutch East Indies

The Dutch East Indies, also known as the Netherlands East Indies ( nl, Nederlands(ch)-Indië; ), was a Dutch colony consisting of what is now Indonesia. It was formed from the nationalised trading posts of the Dutch East India Company, whic ...

, on 10 October. A day later lightning during a sudden tropical storm struck the ship, but the rudimentary "electric chain" or lightning rod that Cook had ordered rigged to ''Endeavour''s mast saved her from serious damage.

The ship remained in very poor condition following her grounding on the Great Barrier Reef in June. The ship's carpenter, John Seetterly, observed that she was "very leaky – makes from twelve to six inches an hour, occasioned by her main keel being wounded in many places, false keel gone from beyond the midships. Wounded on her larbord side where the greatest leak is but I could not come at it for the water." An inspection of the hull revealed that some unrepaired planks were cut through to within inch (3 mm). Cook noted it was a "surprise to every one who saw her bottom how we had kept her above water" for the previous three-month voyage across open seas.

After riding at anchor for two weeks, ''Endeavour'' was heaved out of the water on 9 November and laid on her side for repairs. Some damaged timbers were found to be infested with shipworm

The shipworms are marine bivalve molluscs in the family Teredinidae: a group of saltwater clams with long, soft, naked bodies. They are notorious for boring into (and commonly eventually destroying) wood that is immersed in sea water, including ...

s, which required careful removal to ensure they did not spread throughout the hull.Hosty and Hundley 2003, pp. 55–58 Broken timbers were replaced and the hull recaulked, scraped of shellfish and marine flora, and repainted. Finally, the rigging and pumps were renewed and fresh stores brought aboard for the return journey to England. Repairs and replenishment were completed by Christmas Day 1770, and the next day ''Endeavour'' weighed anchor and set sail westward towards the Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, covering or ~19.8% of the water on Earth's surface. It is bounded by Asia to the north, Africa to the west and Australia to the east. To the south it is bounded by ...

.

Return voyage

Though ''Endeavour'' was now in good condition, her crew were not. During the ship's stay in Batavia, all but 10 of the 94 people aboard had been taken ill withmalaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other animals. Malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, tiredness, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or death. ...

and dysentery

Dysentery (UK pronunciation: , US: ), historically known as the bloody flux, is a type of gastroenteritis that results in bloody diarrhea. Other symptoms may include fever, abdominal pain, and a feeling of incomplete defecation. Complications ...

. By the time ''Endeavour'' set sail on 26 December, seven crew members had died and another forty were too sick to attend their duties. Over the following twelve weeks, a further 23 died from disease and were buried at sea, including Spöring, Green, Parkinson, and the ship's surgeon William Monkhouse.

Cook attributed the sickness to polluted drinking water, and ordered that it be purified with lime juice, but this had little effect. Jonathan Monkhouse, who had proposed fothering the ship to save her from sinking on the reef, died on 6 February, followed six days later by ship's carpenter John Seetterly, whose skilled repair work in Batavia had allowed ''Endeavour'' to resume her voyage. The health of the surviving crew members then slowly improved as the month progressed, with the last deaths from disease being three ordinary seamen on 27 February.

On 13 March 1771, ''Endeavour'' rounded the Cape of Good Hope and made port in Cape Town

Cape Town ( af, Kaapstad; , xh, iKapa) is one of South Africa's three capital cities, serving as the seat of the Parliament of South Africa. It is the legislative capital of the country, the oldest city in the country, and the second largest ...

two days later. Those still sick were taken ashore for treatment. The ship remained in port for four weeks awaiting the recovery of the crew and undergoing minor repairs to her masts. On 15 April, the sick were brought back on board along with ten recruits from Cape Town, and ''Endeavour'' resumed her homeward voyage. The English mainland was sighted on 10 July and ''Endeavour'' entered the port of Dover

Dover () is a town and major ferry port in Kent, South East England. It faces France across the Strait of Dover, the narrowest part of the English Channel at from Cap Gris Nez in France. It lies south-east of Canterbury and east of Maids ...

two days later.

Approximately one month after his return, Cook was promoted to the rank of Commander

Commander (commonly abbreviated as Cmdr.) is a common naval officer rank. Commander is also used as a rank or title in other formal organizations, including several police forces. In several countries this naval rank is termed frigate captain. ...

, and by November 1771 was in receipt of Admiralty Orders for a second expedition, this time aboard HMS ''Resolution''. During his third voyage (second on ''Resolution''), Cook was killed during his attempted kidnapping of the ruling chief of Hawaii at Kealakekua Bay

Kealakekua Bay is located on the Kona coast of the island of Hawaii about south of Kailua-Kona.

Settled over a thousand years ago, the surrounding area contains many archeological and historical sites such as religious temples (heiaus) and al ...

on 14 February 1779.

Later service

While Cook was fêted for his successful voyage, ''Endeavour'' was largely forgotten. Within a week of her return to England, she was directed toWoolwich Dockyard

Woolwich Dockyard (formally H.M. Dockyard, Woolwich, also known as The King's Yard, Woolwich) was an English naval dockyard along the river Thames at Woolwich in north-west Kent, where many ships were built from the early 16th century until ...

for refitting as a naval transport.Hough 1994, p. 215 Under the command of Lieutenant James Gordon she then made three return voyages to the Falkland Islands

The Falkland Islands (; es, Islas Malvinas, link=no ) is an archipelago in the South Atlantic Ocean on the Patagonian Shelf. The principal islands are about east of South America's southern Patagonian coast and about from Cape Dubouze ...

.

The first, under the command of sailing master John Dykes, was to deliver "sufficient provisions to serve 350 men to the end of the year 1772"; she sailed from Portsmouth on 8 November 1771, but due to terrible weather did not arrive at Port Egmont (the British base in the Falkland Islands) until 1 March. ''Endeavour'' sailed from Port Egmont on 4 May in a three-month non-stop voyage until she anchored at Portsmouth.

The second voyage was to reduce the garrison and replace HM Sloop ''Hound'', John Burr Commander, with a smaller vessel, namely the 36-ton shallop

Shallop is a name used for several types of boats and small ships (French ''chaloupe'') used for coastal navigation from the seventeenth century. Originally smaller boats based on the chalupa, the watercraft named this ranged from small boats a li ...

''Penguin'', commander Samuel Clayton. She was a collapsible vessel and was no sooner built than taken apart, and the pieces were stowed in ''Endeavour''. ''Endeavour'' sailed in November with Hugh Kirkland as the sailing master, and additionally the crew of ''Penguin'', and four ship's carpenters whose job was to reassemble ''Penguin'' on arrival, which was 28 January 1773. On 17 April ''Endeavour'' and ''Hound'' sailed for England with their crew. One of ''Penguin'' crew was Bernard Penrose who wrote an account.Penrose 1775 Samuel Clayton also wrote an account.

The third voyage sailed in January 1774 with her purpose to evacuate the Falklands entirely as Britain was faced with political difficulties from the American Colonies, the French and the Spanish. The government assessed that if British ships and troops were engaged in America, Spain might seize the Falklands, capturing the small garrison at Port Egmont with maybe loss of life – this, it was feared, would trigger an outcry which might topple the government. ''Endeavour'' left England in January 1774, sailing from the Falklands with all the British inhabitants on 23 April, leaving a flag and plaque confirming Britain's sovereignty.

''Endeavour'' was paid off in September 1774, being sold in March 1775 by the Royal Navy to shipping magnate J. Mather for £645. Mather returned her to sea for at least one commercial voyage to Archangel

Archangels () are the second lowest rank of angel in the hierarchy of angels. The word ''archangel'' itself is usually associated with the Abrahamic religions, but beings that are very similar to archangels are found in a number of other relig ...

in Russia.

Once the American War of Independence

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

had commenced, the British government needed ships to carry troops and materiel across the Atlantic. In 1775 Mather submitted ''Endeavour'' as a transport ship, being rejected. Thinking that renaming her would fool Deptford Yard, Mather resubmitted ''Endeavour'' under the name ''Lord Sandwich''.Abbass, D. K. ''Rhode Island in the Revolution: Big Happenings in the Smallest Colony''. 2007. Part IV, p. 406. As ''Lord Sandwich'' it was rejected in no uncertain terms: "Unfit for service. She was sold out Service Called ''Endeavour'' Bark refused before". Repairs were made, with acceptance in her third submission, under the name ''Lord Sandwich 2'' as there was already a transport ship called ''Lord Sandwich''.

''Lord Sandwich 2,'' master William Author, sailed on 6 May 1776 from Portsmouth in a fleet of 100 vessels, 68 of which were transports, which was under orders to support Howe's campaign to capture New York. ''Lord Sandwich 2'' carried 206 men mainly from the Hessian du Corps regiment of Hessian mercenaries

Hessians ( or ) were German soldiers who served as auxiliaries to the British Army during the American Revolutionary War. The term is an American synecdoche for all Germans who fought on the British side, since 65% came from the German states o ...

. The crossing was stormy, with two Hessians who were in the same fleet making accounts of the voyage. The scattered fleet assembled at Halifax then sailed to Sandy Hook where other ships and troops assembled. On 15 August 1776 ''Lord Sandwich 2'' was anchored at Sandy Hook; also assembled there was ''Adventure'', which had sailed with ''Resolution'' on Cook's second voyage, now a storeship, captained by John Hallum. Another ship there at that time was HMS ''Siren'', captained by Tobias Furneaux, who had commanded ''Adventure'' on Cook's second voyage.

New York was eventually captured, but Newport, Rhode Island

Newport is an American seaside city on Aquidneck Island in Newport County, Rhode Island. It is located in Narragansett Bay, approximately southeast of Providence, south of Fall River, Massachusetts, south of Boston, and northeast of New Yor ...

, remained in the hands of the Americans and posed a threat as a base for recapturing New York, so in November 1776 a fleet, which included ''Lord Sandwich 2'' carrying Hessian troops, set out to take Rhode Island

Rhode Island (, like ''road'') is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is the List of U.S. states by area, smallest U.S. state by area and the List of states and territories of the United States ...

. The island was taken but not subdued, and ''Lord Sandwich 2'' was needed as a prison ship

A prison ship, often more accurately described as a prison hulk, is a current or former seagoing vessel that has been modified to become a place of substantive detention for convicts, prisoners of war or civilian internees. While many nat ...

.

Final resting place

John Burgoyne

General John Burgoyne (24 February 1722 – 4 August 1792) was a British general, dramatist and politician who sat in the House of Commons from 1761 to 1792. He first saw action during the Seven Years' War when he participated in several bat ...

's army at Saratoga brought France into the war, and in the summer of 1778 a pincer Pincer may refer to:

* Pincers (tool)

*Pincer (biology), part of an animal

*Pincer ligand

In chemistry, a transition metal pincer complex is a type of coordination complex with a pincer ligand. Pincer ligands are chelating agents that binds tig ...

plan was agreed to recapture Newport: the Continental Army

The Continental Army was the army of the United Colonies (the Thirteen Colonies) in the Revolutionary-era United States. It was formed by the Second Continental Congress after the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War, and was establis ...

would approach overland, and a French fleet would sail into the harbour. To prevent the latter the British commander, Captain John Brisbane, determined to blockade the bay by sinking surplus vessels at its mouth. Between 3 and 6 August a fleet of Royal Navy and hired craft, including ''Lord Sandwich 2'', were scuttled at various locations in the Bay.Hosty and Hundley 2003, pp. 16–17 ''Lord Sandwich'' ''2'', previously ''Endeavour'', previously ''Earl of Pembroke'', was sunk on 4 August 1778.

The owners of the sunken vessels were compensated by the British government for the loss of their ships. The Admiralty valuation for 10 of the sunken vessels recorded that many had been built in Yorkshire, and the details of the ''Lord Sandwich'' transport matched those of the former ''Endeavour'' including construction in Whitby, a burthen

Burden or burthen may refer to:

People

* Burden (surname), people with the surname Burden

Places

* Burden, Kansas, United States

* Burden, Luxembourg

Arts, entertainment, and media Films

* ''Burden'' (2018 film), an American drama film

* '' ...

of tons, and re-entry into Navy service on 10 February 1776.

In 1834 a letter appeared in the ''Providence Journal

''The Providence Journal'', colloquially known as the ''ProJo'', is a daily newspaper serving the metropolitan area of Providence, Rhode Island, and is the largest newspaper in Rhode Island. The newspaper was first published in 1829. The newspape ...

'' of Rhode Island, drawing attention to the possible presence of the former ''Endeavour'' on the seabed of the bay. This was swiftly disputed by the British consul in Rhode Island, who wrote claiming that ''Endeavour'' had been bought from Mather by the French in 1790 and renamed ''Liberté''. The consul later admitted he had heard this not from the Admiralty, but as hearsay from the former owners of the French ship. It was later suggested ''Liberté'', which sank off Newport in 1793, was in fact another of Cook's ships, the former HMS ''Resolution'', or another ''Endeavour'', a naval schooner

A schooner () is a type of sailing vessel defined by its rig: fore-and-aft rigged on all of two or more masts and, in the case of a two-masted schooner, the foremast generally being shorter than the mainmast. A common variant, the topsail schoo ...

sold out of service in 1782. A further letter to the ''Providence Journal'' stated that a retired English sailor was conducting guided tours of a hulk

The Hulk is a superhero appearing in American comic books published by Marvel Comics. Created by writer Stan Lee and artist Jack Kirby, the character first appeared in the debut issue of ''The Incredible Hulk (comic book), The Incredible Hulk' ...

on the River Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the The Isis, River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the Longest rivers of the United Kingdom, se ...

as late as 1825, claiming that the ship had once been Cook's ''Endeavour.''

In 1991 the Rhode Island Marine Archaeology Project (RIMAP) began research into the identity of the thirteen transports sunk as part of the Newport blockade of 1778, including ''Lord Sandwich.'' In 1999 RIMAP discovered documents in the Public Record Office

The Public Record Office (abbreviated as PRO, pronounced as three letters and referred to as ''the'' PRO), Chancery Lane in the City of London, was the guardian of the national archives of the United Kingdom from 1838 until 2003, when it was ...

(now called the National Archives) in London confirming that ''Endeavour'' had been renamed ''Lord Sandwich'', had served as a troop transport to North America, and had been scuttled at Newport as part of the 1778 fleet of transports.

In 1999, a combined research team from RIMAP and the Australian National Maritime Museum examined some known wrecks in the harbourHosty and Hundley 2003, pp. 23–26 and in 2000, RIMAP and the ANMM examined a site that appears to be one of the blockade vessels, partly covered by a separate wreck of a 20th-century barge. The older remains were those of a wooden vessel of approximately the same size, and possibly a similar design and materials as ''Lord Sandwich'' ex ''Endeavour''. Confirmation that Cook's former ship had indeed been in Newport Harbor sparked public interest in locating her wreck. However, further mapping showed eight other 18th-century wrecks in Newport Harbor, some with features and conditions also consistent with ''Endeavour''. In 2006 RIMAP announced that the wrecks were unlikely to be raised. In 2016 RIMAP concluded that there was a probability of 80 to 100% that the wreck of ''Endeavour'' was still in Newport Harbor, probably one of a cluster of five wrecks on the seafloor, and planned to investigate the ships and their artifacts further. They were seeking funds to build facilities for handling and storing recovered objects.

In September 2018, Fairfax Media

Fairfax Media was a media company in Australia and New Zealand, with investments in newspaper, magazines, radio and digital properties. The company was founded by John Fairfax as John Fairfax and Sons, who purchased '' The Sydney Morning Hera ...

reported that archaeologists from the Rhode Island Marine Archaeology Project had pinpointed the final resting place of the vessel. The possible discovery was hailed as a "hugely significant moment" in Australian history, but researchers have warned they were yet to "definitively" confirm whether the wreck had been located.

On 3 February 2022, the Australian National Maritime Museum (ANMM) held an event attended by federal cabinet minister Paul Fletcher to announce that the wreck had been confirmed to be that of the ''Endeavour''. The RIMAP has called the announcement "premature" and a "breach of contract", which the ANMM denies. RIMAP's lead investigator stated that "there has been no indisputable data found to prove the site is that iconic vessel, and there are many unanswered questions that could overturn such an identification". Meanwhile, the wreck is being eaten by shipworms

The shipworms are marine bivalve molluscs in the family Teredinidae: a group of saltwater clams with long, soft, naked bodies. They are notorious for boring into (and commonly eventually destroying) wood that is immersed in sea water, including ...

.

''Endeavour'' relics and legacy

In addition to the search for the remains of the ship herself, there was substantial Australian interest in locating relics of the ship's south Pacific voyage. In 1886, the Working Men's Progress Association ofCooktown

Cooktown is a coastal town and locality in the Shire of Cook, Queensland, Australia. Cooktown is at the mouth of the Endeavour River, on Cape York Peninsula in Far North Queensland where James Cook beached his ship, the Endeavour, for re ...

sought to recover the six cannon thrown overboard when ''Endeavour'' grounded on the Great Barrier Reef. A £300 reward was offered for anyone who could locate and recover the guns, but searches that year and the next were fruitless and the money went unclaimed. Remains of equipment left at Endeavour River were discovered in around 1900, and in 1913 the crew of a merchant steamer erroneously claimed to have recovered an ''Endeavour'' cannon from shallow water near the Reef.

In 1937, a small part of ''Endeavour'' keel was given to the Australian Government

The Australian Government, also known as the Commonwealth Government, is the national government of Australia, a federal parliamentary constitutional monarchy. Like other Westminster-style systems of government, the Australian Governmen ...

by philanthropist Charles Wakefield in his capacity as president of the Admiral Arthur Phillip Memorial. Australian Prime Minister Joseph Lyons

Joseph Aloysius Lyons (15 September 1879 – 7 April 1939) was an Australian politician who served as the 10th Prime Minister of Australia, in office from 1932 until his death in 1939. He began his career in the Australian Labor Party (ALP), ...

described the section of keel as "intimately associated with the discovery and foundation of Australia".

Searches were resumed for the lost Endeavour Reef cannon, but expeditions in 1966, 1967, and 1968 were unsuccessful. They were finally recovered in 1969 by a research team from the American Academy of Natural Sciences

The Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University, formerly the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, is the oldest natural science research institution and museum in the Americas. It was founded in 1812, by many of the leading natura ...

, using a sophisticated magnetometer

A magnetometer is a device that measures magnetic field or magnetic dipole moment. Different types of magnetometers measure the direction, strength, or relative change of a magnetic field at a particular location. A compass is one such device, ...

to locate the cannon, a quantity of iron ballast and the abandoned bower anchor. Conservation work on the cannon was undertaken by the Australian National Maritime Museum, after which two of the cannon were displayed at its headquarters in Sydney's Darling Harbour

Darling Harbour is a harbour adjacent to the city centre of Sydney, New South Wales, Australia that is made up of a large recreational and pedestrian precinct that is situated on western outskirts of the Sydney central business district.

Origin ...

, and eventually put on display at Botany Bay and the National Museum of Australia

The National Museum of Australia, in the national capital Canberra, preserves and interprets Australia's social history, exploring the key issues, people and events that have shaped the nation. It was formally established by the ''National Muse ...

in Canberra (with a replica remaining at the museum). A third cannon and the bower anchor were displayed at the James Cook Museum in Cooktown, with the remaining three at the National Maritime Museum

The National Maritime Museum (NMM) is a maritime museum in Greenwich, London. It is part of Royal Museums Greenwich, a network of museums in the Maritime Greenwich World Heritage Site. Like other publicly funded national museums in the Unite ...

in London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

, the Academy of Natural Sciences

The Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University, formerly the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, is the oldest natural science research institution and museum in the Americas. It was founded in 1812, by many of the leading natura ...

in Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Since ...

, and the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

The Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa is New Zealand's national museum and is located in Wellington. ''Te Papa Tongarewa'' translates literally to "container of treasures" or in full "container of treasured things and people that spring f ...

in Wellington

Wellington ( mi, Te Whanganui-a-Tara or ) is the capital city of New Zealand. It is located at the south-western tip of the North Island, between Cook Strait and the Remutaka Range. Wellington is the second-largest city in New Zealand by ...

.

''Endeavour''s Pacific voyage was further commemorated in the use of her image on the reverse of the New Zealand fifty-cent coin.

Apollo 15

Apollo 15 (July 26August 7, 1971) was the ninth crewed mission in the United States' Apollo program and the fourth to land on the Moon. It was the first J mission, with a longer stay on the Moon and a greater focus on science than ear ...

's command and service module

The Apollo command and service module (CSM) was one of two principal components of the United States Apollo spacecraft, used for the Apollo program, which landed astronauts on the Moon between 1969 and 1972. The CSM functioned as a mother sh ...

CSM-112 was given the call sign

In broadcasting and radio communications, a call sign (also known as a call name or call letters—and historically as a call signal—or abbreviated as a call) is a unique identifier for a transmitter station. A call sign can be formally ass ...

''Endeavour''; astronaut David Scott

David Randolph Scott (born June 6, 1932) is an American retired test pilot and NASA astronaut who was the seventh person to walk on the Moon. Selected as part of the third group of astronauts in 1963, Scott flew to space three times and ...

explained the choice of the name on the grounds that its captain, Cook, had commanded the first purely scientific sea voyage, and Apollo 15 was the first lunar landing mission on which there was a heavy emphasis on science. Apollo 15 took with it a small piece of wood claimed to be from Cook's ship. The ship was again commemorated in the naming of the Space Shuttle ''Endeavour'' in 1989. The shuttle's name in turn inspired the naming of the SpaceX

Space Exploration Technologies Corp. (SpaceX) is an American spacecraft manufacturer, launcher, and a satellite communications corporation headquartered in Hawthorne, California. It was founded in 2002 by Elon Musk with the stated goal o ...

Crew Dragon ''Endeavour'', the first such capsule to launch crew.

Replica vessels

In January 1988, to commemorate the

In January 1988, to commemorate the Australian Bicentenary

The bicentenary of Australia was celebrated in 1988. It marked 200 years since the arrival of the First Fleet of British convict ships at Sydney in 1788.

History

The bicentennial year marked Captain Arthur Phillip's arrival with the 11 ships ...

of European settlement in Australia, work began in Fremantle

Fremantle () () is a port city in Western Australia, located at the mouth of the Swan River in the metropolitan area of Perth, the state capital. Fremantle Harbour serves as the port of Perth. The Western Australian vernacular diminutive for ...

, Western Australia

Western Australia (commonly abbreviated as WA) is a state of Australia occupying the western percent of the land area of Australia excluding external territories. It is bounded by the Indian Ocean to the north and west, the Southern Ocean to t ...

, on a replica of ''Endeavour''. Financial difficulties delayed completion until December 1993, and the vessel was not commissioned until April 1994. The replica vessel commenced her maiden voyage in October of that year, sailing to Sydney Harbour and then following Cook's path from Botany Bay northward to Cooktown. From 1996 to 2002, the replica retraced Cook's ports of call around the world, arriving in the original ''Endeavour'' home port of Whitby in May 1997 and June 2002. Footage of waves shot while rounding Cape Horn on this voyage was later used in digitally composited scenes in the 2003 film '' Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World''.

The replica ''Endeavour'' visited various European ports before undertaking her final ocean voyage from Whitehaven to Sydney Harbour

Port Jackson, consisting of the waters of Sydney Harbour, Middle Harbour, North Harbour and the Lane Cove River, Lane Cove and Parramatta River, Parramatta Rivers, is the ria or harbor, natural harbour of Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. T ...

on 8 November 2004. Her arrival in Sydney was delayed when she ran aground in Botany Bay, a short distance from the point where Cook first set foot in Australia 235 years earlier. The replica ''Endeavour'' finally entered Sydney Harbour on 17 April 2005, having travelled , including twice around the world. Ownership of the replica was transferred to the Australian National Maritime Museum in 2005 for permanent service as a museum ship

A museum ship, also called a memorial ship, is a ship that has been preserved and converted into a museum open to the public for educational or memorial purposes. Some are also used for training and recruitment purposes, mostly for the small numb ...

in Sydney's Darling Harbour.

A second full-size replica of ''Endeavour'' was berthed on the River Tees

The River Tees (), in Northern England, rises on the eastern slope of Cross Fell in the North Pennines and flows eastwards for to reach the North Sea between Hartlepool and Redcar near Middlesbrough. The modern day history of the river has bee ...

in Stockton-on-Tees

Stockton-on-Tees, often simply referred to as Stockton, is a market town in the Borough of Stockton-on-Tees in County Durham, England. It is on the northern banks of the River Tees, part of the Teesside built-up area. The town had an estimat ...

before being moved to Whitby. While it reflects the external dimensions of Cook's vessel, this replica was constructed with a steel rather than a timber frame, has one less internal deck than the original, and is not designed to go to sea.

The Russell Museum, in the Bay of Islands

The Bay of Islands is an area on the east coast of the Far North District of the North Island of New Zealand. It is one of the most popular fishing, sailing and tourist destinations in the country, and has been renowned internationally for it ...

, New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island coun ...

, has a sailing one-fifth scale replica of ''Endeavour''. It was built in Auckland in 1969 and travelled by trailer throughout New Zealand and Australia before being presented to the museum in 1970.

At Whitby

Whitby is a seaside town, port and civil parish in the Scarborough borough of North Yorkshire, England. Situated on the east coast of Yorkshire at the mouth of the River Esk, Whitby has a maritime, mineral and tourist heritage. Its East Cl ...

the "Bark Endeavour Whitby" is a scaled-down replica of the original ship. It relies on engines for propulsion and is a little less than half the size of the original. Trips for tourists take them along the coast to Sandsend

Sandsend is a small fishing village, near to Whitby in the Scarborough district of North Yorkshire, England. It forms part of the civil parish of Lythe. It is the birthplace of fishing magnate George Pyman. Originally two villages, Sandsend ...

.

A replica of the ship is displayed in the Cleveland Centre

The Cleveland Centre, is a shopping centre in the town of Middlesbrough, North Yorkshire, England. It is owned by Middlesbrough Council, previous Waypoint New Frontier until 2022. It was renamed The Mall (after its previous owner The Mall F ...

, Middlesbrough

Middlesbrough ( ) is a town on the southern bank of the River Tees in North Yorkshire, England. It is near the North York Moors national park. It is the namesake and main town of its local borough council area.

Until the early 1800s, the ...

, England.

See also

* '' Blue Latitudes'', a travel book byTony Horwitz

Anthony Lander Horwitz (June 9, 1958 – May 27, 2019) was an American journalist and author who won the 1995 Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting.

His books include ''One for the Road: a Hitchhiker's Outback'', ''Baghdad Without a Map'', ' ...

* European and American voyages of scientific exploration

The era of European and American voyages of scientific exploration followed the Age of Discovery and were inspired by a new confidence in science and reason that arose in the Age of Enlightenment. Maritime expeditions in the Age of Discovery were ...

Notes

Footnotes