HMS Temeraire (1876) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

HMS ''Temeraire'' was an ironclad battleship of the Victorian

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against Fr ...

which was unique in that she carried her main armament partly in the traditional broadside battery, and partly in barbette

Barbettes are several types of gun emplacement in terrestrial fortifications or on naval ships.

In recent naval usage, a barbette is a protective circular armour support for a heavy gun turret. This evolved from earlier forms of gun protectio ...

s on the upper deck.

Design and construction

Propulsion

''Temeraire'' was equipped with two Humpreys & Tennant 2-cyl. steam engines, each driving one shaft and developing a total of 7,697 hp (5,661 kW), with which she reached a top speed of 14.65 knots (16.86 mph). Steam was supplied by twelve boilers. The ship could carry a maximum of 629 t. coal. ''Temeraire'' was rigged as a two-mastedbarque

A barque, barc, or bark is a type of sailing vessel with three or more masts having the fore- and mainmasts rigged square and only the mizzen (the aftmost mast) rigged fore and aft. Sometimes, the mizzen is only partly fore-and-aft rigged, b ...

and had a sail area of 25,000 sq ft. The ship's crew consisted of 580 officers and ratings.Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1860-1905 p 18.

Armament

Her armament was partly conventional, being deployed on the broadside, and partly experimental; she was the first British ship to be equipped with guns inbarbette

Barbettes are several types of gun emplacement in terrestrial fortifications or on naval ships.

In recent naval usage, a barbette is a protective circular armour support for a heavy gun turret. This evolved from earlier forms of gun protectio ...

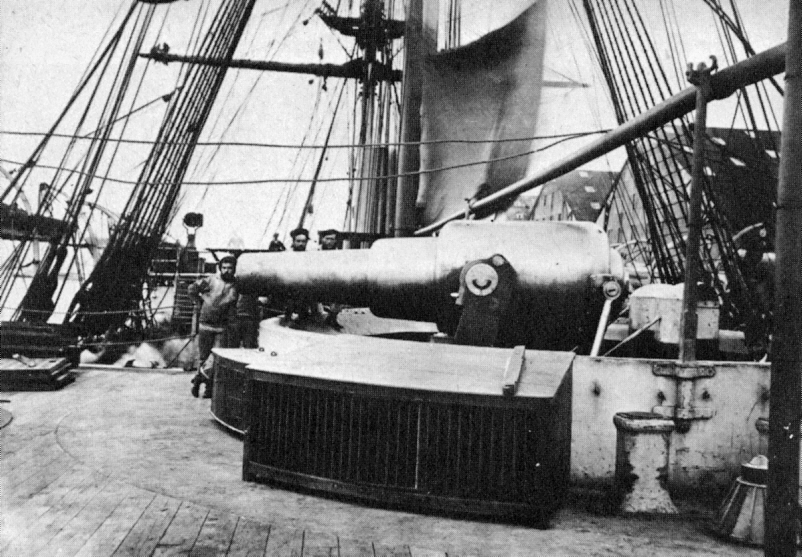

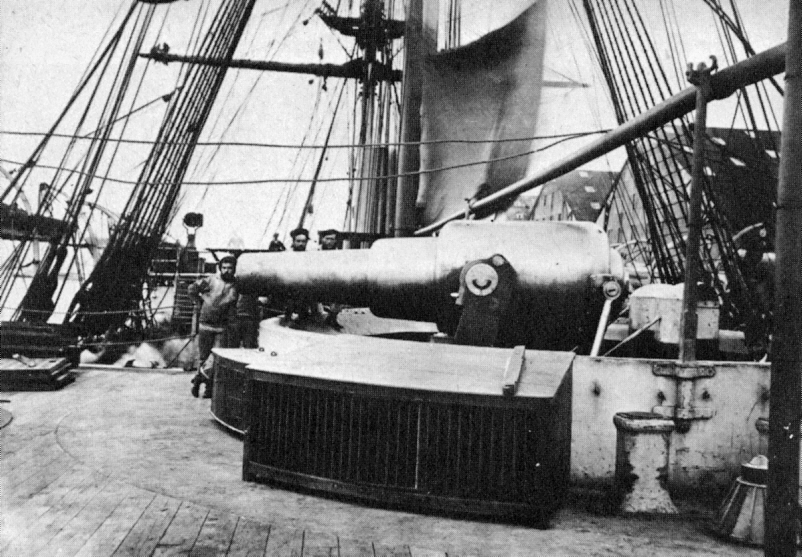

s located on the midline on the upper deck. Indeed, she was the first British ship with barbettes of any kind.The armament consisted of four 11-inch muzzle-loading guns, one each on the forecastle and stern, and one each at the forward corners of the central battery to port and starboard. The 11-inch guns were installed on a Moncrieff mount, which had a mechanism for raising and lowering the gun. The mount was on a massive turntable that provided enough space for the hydraulic ramrod. The loading and lifting process, as well as the rotation of the mount, were operated by a disguised stand with four control levers. When the gun was extended and aimed at the target, it was adjusted to elevation graduated in degrees by a rod linkage on each side of the breech. A full gun crew consisted of six men, but the guns could be operated by three in an emergency. In addition, four 10in muzzle-loading guns were located in the rear of the central battery, two on each broadside. To protect against attack by boats armed with torpedoes, the ship received four 20-pounder breech-loading guns. ''Temeraire'' was also fitted with two launchers for spar torpedo

A spar torpedo is a weapon consisting of a bomb placed at the end of a long pole, or spar, and attached to a boat. The weapon is used by running the end of the spar into the enemy ship. Spar torpedoes were often equipped with a barbed spear at ...

es. In 1884, the 20-pounders were replaced by four 25-pounder breech-loading guns, and four 3-pounder Hotchkiss and ten 3-pounder Nordenfelt QF guns were also added to the ship.Ballard (1980) pp 205-209

Armour

The armoured belt extended along the entire length of the ship. It was 11in thick amidships and had a total height of 18.8in, of which 10in was above and 8.9in below the waterline. Towards the bow and stern it tapered to 5in and 5.5in respectively. The central battery was protected by 8in sides and 5in transverse bulkheads. The oval barbettes were protected by 10in forward and 8in aft. This shape was necessary to make room not only for the guns to be lowered, but also for a hydraulic ramrod, which was opposite the gun muzzle and almost as long as the barrel itself. The wider end was open at the top to allow the gun to rise and fire, and the narrower end with the ramrod was covered with iron plates. Its distinctive feature was a complete and continuous armour by aparapet

A parapet is a barrier that is an extension of the wall at the edge of a roof, terrace, balcony, walkway or other structure. The word comes ultimately from the Italian ''parapetto'' (''parare'' 'to cover/defend' and ''petto'' 'chest/breast'). ...

that rose 36in above the deck surrounding it, protecting the gun crew and the gun itself when loaded or not in use.

Service history

The ''Temeraire'' named after the French ship of the line Téméraire captured in 1759, was laid down at Chatham on 18 August 1873, launched on 9 May, and commissioned in 1877 for service in theMediterranean fleet

The British Mediterranean Fleet, also known as the Mediterranean Station, was a formation of the Royal Navy. The Fleet was one of the most prestigious commands in the navy for the majority of its history, defending the vital sea link between t ...

under Captain Michael Culme-Seymour. She remained there for the next fourteen years except for the winter of 1887-88 when she was part of the Channel Squadron. Upon her arrival in Besika Bay, she became Admiral

Admiral is one of the highest ranks in some navies. In the Commonwealth nations and the United States, a "full" admiral is equivalent to a "full" general in the army or the air force, and is above vice admiral and below admiral of the fleet ...

Hornby's flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically the ...

. In 1878 she was ordered to the Dardanelles

The Dardanelles (; tr, Çanakkale Boğazı, lit=Strait of Çanakkale, el, Δαρδανέλλια, translit=Dardanéllia), also known as the Strait of Gallipoli from the Gallipoli peninsula or from Classical Antiquity as the Hellespont (; ...

to observe the progress of the Russo-Turkish War

The Russo-Turkish wars (or Ottoman–Russian wars) were a series of twelve wars fought between the Russian Empire and the Ottoman Empire between the 16th and 20th centuries. It was one of the longest series of military conflicts in European histo ...

. She remained near Istanbul

)

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code = 34000 to 34990

, area_code = +90 212 (European side) +90 216 (Asian side)

, registration_plate = 34

, blank_name_sec2 = GeoTLD

, blank_i ...

(then Constantinople) until 1879 to represent a strong British position during the protracted international negotiations that led to the Congress of Berlin

The Congress of Berlin (13 June – 13 July 1878) was a diplomatic conference to reorganise the states in the Balkan Peninsula after the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–78, which had been won by Russia against the Ottoman Empire. Represented at th ...

.

She then took part in the reconquest of Ottoman-occupied Cyprus

Cyprus ; tr, Kıbrıs (), officially the Republic of Cyprus,, , lit: Republic of Cyprus is an island country located south of the Anatolian Peninsula in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Its continental position is disputed; while it is ...

. In 1881 she was paid off in Malta

Malta ( , , ), officially the Republic of Malta ( mt, Repubblika ta' Malta ), is an island country in the Mediterranean Sea. It consists of an archipelago, between Italy and Libya, and is often considered a part of Southern Europe. It lies ...

and given a new command. At the outbreak of the Anglo-Egyptian War

The British conquest of Egypt (1882), also known as Anglo-Egyptian War (), occurred in 1882 between Egyptian and Sudanese forces under Ahmed ‘Urabi and the United Kingdom. It ended a nationalist uprising against the Khedive Tewfik Pasha. It ...

in 1882, she was recommissioned and took part in the attack on the defensive positions on the coast of Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandri ...

. In 1884, she was again decommissioned and recommissioned the same year for service in the Mediterranean under Compton Edward Domvile. In 1887 she returned home and was paid off at Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port and city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a unitary authority since 1 April 1997 and is administered by Portsmouth City Council.

Portsmouth is the most d ...

. After being recommissioned for service in the Channel Squadron, she visited Vigo

Vigo ( , , , ) is a city and municipality in the province of Pontevedra, within the autonomous community of Galicia, Spain. Located in the northwest of the Iberian Peninsula, it sits on the southern shore of an inlet of the Atlantic Ocean, the ...

, Genoa

Genoa ( ; it, Genova ; lij, Zêna ). is the capital of the Italian region of Liguria and the sixth-largest city in Italy. In 2015, 594,733 people lived within the city's administrative limits. As of the 2011 Italian census, the Province of ...

, and Lisbon

Lisbon (; pt, Lisboa ) is the capital and largest city of Portugal, with an estimated population of 544,851 within its administrative limits in an area of 100.05 km2. Lisbon's urban area extends beyond the city's administrative limits w ...

. She then returned home, but the growing threat from the French fleet at Toulon

Toulon (, , ; oc, label= Provençal, Tolon , , ) is a city on the French Riviera and a large port on the Mediterranean coast, with a major naval base. Located in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region, and the Provence province, Toulon is th ...

made it necessary to increase British forces in the Mediterranean as well. Therefore, ''Temeraire'' was reassigned to the Mediterranean Fleet under the command of James Drummond.

During this time, an incident occurred that resulted in a near disaster with ''HMS Orion''. The squadron was in close formation, at sea with ''Temeraire'' as the last ship in the starboard column and ''Orion'' as the next-to-last ship in the port column, which, with two hawser

Hawser () is a nautical term for a thick cable or rope used in mooring or towing a ship.

A hawser passes through a hawsehole, also known as a cat hole, located on the hawse. The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, third editi ...

s between the columns, resulted in her being four points off port bow of the former in short manoeuvring distance. Both ships were signalled to change position. According to the instructions of the signal book used at the time, such movements had to comply with the traffic rules by moving from port to port. But due to the prevailing situation, the ''Orion''turret ship

Turret ships were a 19th-century type of warship, the earliest to have their guns mounted in a revolving gun turret, instead of a broadside arrangement.

Background

Before the development of large-calibre, long-range guns in the mid-19th century, ...

s at that time.

From 1890 she cruised in the Levant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is ...

and visited Souda Bay

Souda Bay is a bay and natural harbour near the town of Souda on the northwest coast of the Greek island of Crete. The bay is about 15 km long and only two to four km wide, and a deep natural harbour. It is formed between the Akrotiri p ...

in Crete

Crete ( el, Κρήτη, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cyprus, ...

. After wintering in Thessaloniki

Thessaloniki (; el, Θεσσαλονίκη, , also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece, with over one million inhabitants in its metropolitan area, and the capital of the geographic region of ...

, ''Temeraire'' was ordered to return home in the spring of 1891, where she was paid off in Plymouth

Plymouth () is a port city status in the United Kingdom, city and unitary authority in South West England. It is located on the south coast of Devon, approximately south-west of Exeter and south-west of London. It is bordered by Cornwall to ...

and assigned to the reserve. Plans for a possible modernization were developed but ultimately discarded due to excessive cost. In 1904 she was renamed ''Indus II'' and in 1915 ''Akbar''. She was finally sold to the Netherlands for scrapping in May 1921.Ballard (1980) pp. 210-213

References

Publications

* * * * Dittmar F. J. & Colledge J. J., ''British Warships 1914-1919'', (Ian Allan, London,1972) * * Oscar Parkes ''British Battleships'' * * Winfield, R.; Lyon, D. (2004). ''The Sail and Steam Navy List: All the Ships of the Royal Navy 1815–1889''. London: Chatham Publishing. . {{DEFAULTSORT:Temeraire (1876) Battleships of the Royal Navy Ships built in Chatham 1876 ships Victorian-era battleships of the United Kingdom Disappearing guns