HMS Illustrious (87) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

HMS ''Illustrious'' was the

The Royal Navy's 1936 Naval Programme authorised the construction of two aircraft carriers.

The Royal Navy's 1936 Naval Programme authorised the construction of two aircraft carriers.

''Illustrious'', the fourth ship of her name, was ordered as part of the 1936 Naval Programme from

''Illustrious'', the fourth ship of her name, was ordered as part of the 1936 Naval Programme from

Upon his arrival in the Mediterranean, Lyster proposed a carrier airstrike on the Italian fleet at its base in

Upon his arrival in the Mediterranean, Lyster proposed a carrier airstrike on the Italian fleet at its base in  Now augmented by reinforcements from the UK, the Mediterranean Fleet detached ''Illustrious'', four cruisers, and four destroyers to a point south-east of Taranto. The first wave of a dozen aircraft, all that the ship could launch at one time, flew off by 20:40 and the second wave of nine by 21:34. Six aircraft in each airstrike were armed with torpedoes and the remainder with bombs or flares or both to supplement the three-quarter moon. The

Now augmented by reinforcements from the UK, the Mediterranean Fleet detached ''Illustrious'', four cruisers, and four destroyers to a point south-east of Taranto. The first wave of a dozen aircraft, all that the ship could launch at one time, flew off by 20:40 and the second wave of nine by 21:34. Six aircraft in each airstrike were armed with torpedoes and the remainder with bombs or flares or both to supplement the three-quarter moon. The

On 7 January 1941, ''Illustrious'' set sail to provide air cover for convoys to

On 7 January 1941, ''Illustrious'' set sail to provide air cover for convoys to  While her steering was being repaired in Malta, the ''Illustrious'' was bombed again on 16 January by 17

While her steering was being repaired in Malta, the ''Illustrious'' was bombed again on 16 January by 17

The conquest of British Malaya and the

The conquest of British Malaya and the  She was then formally assigned to the Eastern Fleet and, after a short refit in Durban, sailed to

She was then formally assigned to the Eastern Fleet and, after a short refit in Durban, sailed to

After a farewell visit from the Eastern Fleet commander, Admiral Sir

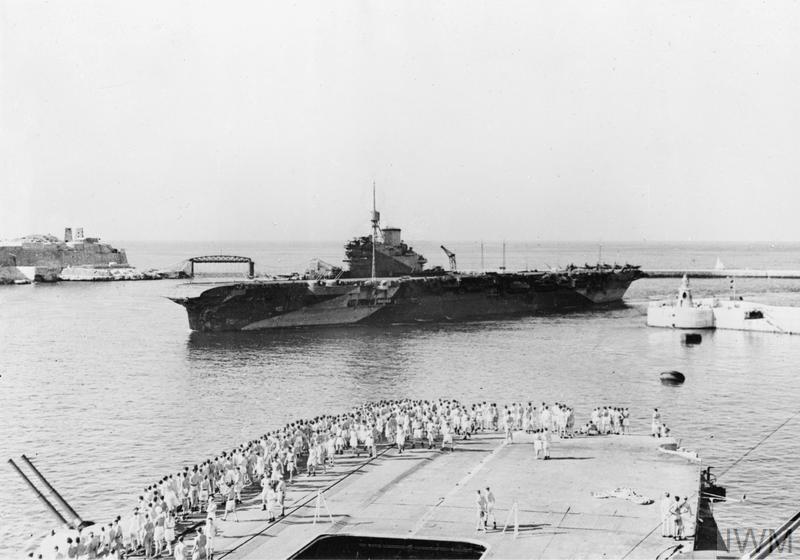

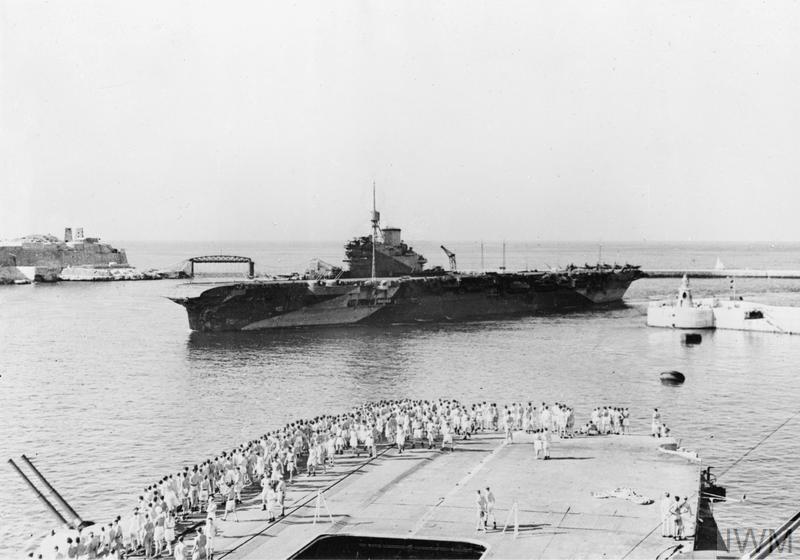

After a farewell visit from the Eastern Fleet commander, Admiral Sir  Together with the ''Unicorn'', she sailed for the Mediterranean on 13 August to prepare for the landings at Salerno (Operation Avalanche), reaching Malta a week later. Her air group was reinforced at this time by four more Martlets each for 878 and 890 Squadrons. She was assigned to

Together with the ''Unicorn'', she sailed for the Mediterranean on 13 August to prepare for the landings at Salerno (Operation Avalanche), reaching Malta a week later. Her air group was reinforced at this time by four more Martlets each for 878 and 890 Squadrons. She was assigned to

''Illustrious'' departed Britain on 30 December and arrived in

''Illustrious'' departed Britain on 30 December and arrived in

She arrived on 10 February and repairs began when she entered the Captain Cook Dock in the Garden Island Dockyard the next day, well before it was officially opened by the

She arrived on 10 February and repairs began when she entered the Captain Cook Dock in the Garden Island Dockyard the next day, well before it was officially opened by the

lead ship

The lead ship, name ship, or class leader is the first of a series or class of ships all constructed according to the same general design. The term is applicable to naval ships and large civilian vessels.

Large ships are very complex and may ...

of her class of aircraft carrier

An aircraft carrier is a warship that serves as a seagoing airbase, equipped with a full-length flight deck and facilities for carrying, arming, deploying, and recovering aircraft. Typically, it is the capital ship of a fleet, as it allows a ...

s built for the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against Fr ...

before World War II. Her first assignment after completion and working up was with the Mediterranean Fleet

The British Mediterranean Fleet, also known as the Mediterranean Station, was a formation of the Royal Navy. The Fleet was one of the most prestigious commands in the navy for the majority of its history, defending the vital sea link between t ...

, in which her aircraft's most notable achievement was sinking one Italian battleship

A battleship is a large armour, armored warship with a main artillery battery, battery consisting of large caliber guns. It dominated naval warfare in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The term ''battleship'' came into use in the late 1 ...

and badly damaging two others during the Battle of Taranto

The Battle of Taranto took place on the night of 11–12 November 1940 during the Second World War between British naval forces, under Admiral Andrew Cunningham, and Italian naval forces, under Admiral Inigo Campioni. The Royal Navy launched ...

in late 1940. Two months later the carrier was crippled by German dive bomber

A dive bomber is a bomber aircraft that dives directly at its targets in order to provide greater accuracy for the bomb it drops. Diving towards the target simplifies the bomb's trajectory and allows the pilot to keep visual contact through ...

s and was repaired in the United States. After sustaining damage on the voyage home in late 1941 by a collision with her sister ship

A sister ship is a ship of the same class or of virtually identical design to another ship. Such vessels share a nearly identical hull and superstructure layout, similar size, and roughly comparable features and equipment. They often share a ...

, ''Illustrious'' was sent to the Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, covering or ~19.8% of the water on Earth's surface. It is bounded by Asia to the north, Africa to the west and Australia to the east. To the south it is bounded by ...

in early 1942 to support the invasion of Vichy French

Vichy France (french: Régime de Vichy; 10 July 1940 – 9 August 1944), officially the French State ('), was the fascist French state headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain during World War II. Officially independent, but with half of its ter ...

Madagascar (Operation Ironclad

The Battle of Madagascar (5 May – 6 November 1942) was a British campaign to capture the Vichy French-controlled island Madagascar during World War II. The seizure of the island by the British was to deny Madagascar's ports to the Imperial ...

). After returning home in early 1943, the ship was given a lengthy refit and briefly assigned to the Home Fleet

The Home Fleet was a fleet of the Royal Navy that operated from the United Kingdom's territorial waters from 1902 with intervals until 1967. In 1967, it was merged with the Mediterranean Fleet creating the new Western Fleet.

Before the Firs ...

. She was transferred to Force H

Force H was a British naval formation during the Second World War. It was formed in 1940, to replace French naval power in the western Mediterranean removed by the French armistice with Nazi Germany. The force occupied an odd place within the ...

for the Battle of Salerno

Operation Avalanche was the codename for the Allied landings near the port of Salerno, executed on 9 September 1943, part of the Allied invasion of Italy during World War II. The Italians withdrew from the war the day before the invasion, bu ...

in mid-1943 and then rejoined the Eastern Fleet

Eastern may refer to:

Transportation

*China Eastern Airlines, a current Chinese airline based in Shanghai

*Eastern Air, former name of Zambia Skyways

* Eastern Air Lines, a defunct American airline that operated from 1926 to 1991

*Eastern Air L ...

in the Indian Ocean at the beginning of 1944. Her aircraft attacked several targets in the Japanese-occupied Dutch East Indies over the following year before ''Illustrious'' was transferred to the newly formed British Pacific Fleet

The British Pacific Fleet (BPF) was a Royal Navy formation that saw action against Japan during the Second World War. The fleet was composed of empire naval vessels. The BPF formally came into being on 22 November 1944 from the remaining ships o ...

(BPF). The carrier participated in the early stages of the Battle of Okinawa

The , codenamed Operation Iceberg, was a major battle of the Pacific War fought on the island of Okinawa by United States Army (USA) and United States Marine Corps (USMC) forces against the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA). The initial invasion of ...

until mechanical defects arising from accumulated battle damage became so severe she was ordered home early for repairs in May 1945.

The war ended while she was in the dockyard and the Admiralty

Admiralty most often refers to:

*Admiralty, Hong Kong

*Admiralty (United Kingdom), military department in command of the Royal Navy from 1707 to 1964

*The rank of admiral

*Admiralty law

Admiralty can also refer to:

Buildings

* Admiralty, Traf ...

decided to modify her for use as the Home Fleet's trials and training carrier. In this role she conducted the deck-landing trials for most of the British post-war naval aircraft in the early 1950s. She was occasionally used to ferry troops and aircraft to and from foreign deployments as well as participating in exercises. In 1951, she helped to transport troops to quell rioting in Cyprus

Cyprus ; tr, Kıbrıs (), officially the Republic of Cyprus,, , lit: Republic of Cyprus is an island country located south of the Anatolian Peninsula in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Its continental position is disputed; while it is ...

after the collapse of the Anglo-Egyptian treaty of 1936. She was paid off in early 1955 and sold for scrap

Scrap consists of recyclable materials, usually metals, left over from product manufacturing and consumption, such as parts of vehicles, building supplies, and surplus materials. Unlike waste, scrap has monetary value, especially recovered m ...

in late 1956.

Background and description

The Royal Navy's 1936 Naval Programme authorised the construction of two aircraft carriers.

The Royal Navy's 1936 Naval Programme authorised the construction of two aircraft carriers. Admiral

Admiral is one of the highest ranks in some navies. In the Commonwealth nations and the United States, a "full" admiral is equivalent to a "full" general in the army or the air force, and is above vice admiral and below admiral of the fleet ...

Sir Reginald Henderson

Admiral Sir Reginald Guy Hannam Henderson, GCB (1 September 1881 – 2 May 1939) was a Royal Navy officer who went on to be Third Sea Lord and Controller of the Navy.

Early life and education

Henderson was born into a naval family in Falmout ...

, Third Sea Lord and Controller of the Navy, was determined not to simply modify the previous unarmoured design. He believed that carriers could not be successfully defended by their own aircraft without some form of early-warning system. Lacking that, there was nothing to prevent land-based aircraft from attacking them, especially in confined waters like the North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Norway, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium. An epeiric sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian ...

and Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on ...

. This meant that the ship had to be capable of remaining in action after sustaining damage and that her fragile aircraft had to be protected entirely from damage. The only way to do this was to completely armour the hangar

A hangar is a building or structure designed to hold aircraft or spacecraft. Hangars are built of metal, wood, or concrete. The word ''hangar'' comes from Middle French ''hanghart'' ("enclosure near a house"), of Germanic origin, from Frankish ...

in which the aircraft would shelter, but putting so much weight high in the ship allowed only a single-storey hangar due to stability concerns. This halved the aircraft capacity compared with the older unarmoured carriers, exchanging offensive potential for defensive survivability.

''Illustrious'' was in length overall

__NOTOC__

Length overall (LOA, o/a, o.a. or oa) is the maximum length of a vessel's hull measured parallel to the waterline. This length is important while docking the ship. It is the most commonly used way of expressing the size of a ship, and ...

and at the waterline

The waterline is the line where the hull of a ship meets the surface of the water. Specifically, it is also the name of a special marking, also known as an international load line, Plimsoll line and water line (positioned amidships), that indi ...

. Her beam was at the waterline and she had a draught of at deep load

The displacement or displacement tonnage of a ship is its weight. As the term indicates, it is measured indirectly, using Archimedes' principle, by first calculating the volume of water displaced by the ship, then converting that value into we ...

. She displaced at standard load as completed.Friedman, p. 366 Her complement was approximately 1,299 officers and enlisted men upon completion in 1940.Hobbs 2013, p. 89 By 1944, she was severely overcrowded with a total crew of 1,997. After post-war modifications to convert her into a trials

In law, a trial is a coming together of parties to a dispute, to present information (in the form of evidence) in a tribunal, a formal setting with the authority to adjudicate claims or disputes. One form of tribunal is a court. The tribun ...

carrier, her complement was reduced to 1,090 officers and enlisted men.Lyon, p. 233

The ship had three Parsons

Parsons may refer to:

Places

In the United States:

* Parsons, Kansas, a city

* Parsons, Missouri, an unincorporated community

* Parsons, Tennessee, a city

* Parsons, West Virginia, a town

* Camp Parsons, a Boy Scout camp in the state of Washingt ...

geared steam turbine

A steam turbine is a machine that extracts thermal energy from pressurized steam and uses it to do mechanical work on a rotating output shaft. Its modern manifestation was invented by Charles Parsons in 1884. Fabrication of a modern steam tu ...

s, each driving one shaft, using steam supplied by six Admiralty 3-drum boiler

Three-drum boilers are a class of water-tube boiler used to generate steam, typically to power ships. They are compact and of high evaporative power, factors that encourage this use. Other boiler designs may be more efficient, although bulkier, an ...

s. The turbines were designed to produce a total of , enough to give a maximum speed of at deep load. On 24 May 1940 ''Illustrious'' ran her sea trials and her engines reached . Her exact speeds were not recorded as she had her paravanes streamed, but it was estimated that she could have made about under full power.Lyon, p. 235 She carried a maximum of of fuel oil

Fuel oil is any of various fractions obtained from the distillation of petroleum (crude oil). Such oils include distillates (the lighter fractions) and residues (the heavier fractions). Fuel oils include heavy fuel oil, marine fuel oil (MFO), b ...

which gave her a range of at or at or at .

The armoured flight deck

The flight deck of an aircraft carrier is the surface from which its aircraft take off and land, essentially a miniature airfield at sea. On smaller naval ships which do not have aviation as a primary mission, the landing area for helicopte ...

had a usable length of , due to prominent "round-downs" at each end designed to reduce the effects of air turbulence caused by the carrier's structure on aircraft taking-off and landing, and a maximum width of . A single hydraulic aircraft catapult

An aircraft catapult is a device used to allow aircraft to take off from a very limited amount of space, such as the deck of a vessel, but can also be installed on land-based runways in rare cases. It is now most commonly used on aircraft carrier ...

was fitted on the forward part of the flight deck. The ship was equipped with two unarmoured lifts on the centreline, each of which measured . The hangar was long and had a maximum width of . It had a height of which allowed storage of Lend-Lease

Lend-Lease, formally the Lend-Lease Act and introduced as An Act to Promote the Defense of the United States (), was a policy under which the United States supplied the United Kingdom, the Soviet Union and other Allied nations with food, oil, ...

Vought F4U Corsair

The Vought F4U Corsair is an American fighter aircraft which saw service primarily in World War II and the Korean War. Designed and initially manufactured by Chance Vought, the Corsair was soon in great demand; additional production contract ...

fighters once their wingtips were clipped. The hangar was designed to accommodate 36 aircraft, for which of aviation spirit was provided.

Armament, electronics and protection

The main armament of the ''Illustrious'' class consisted of sixteen quick-firing (QF)dual-purpose gun

A dual-purpose gun is a naval artillery mounting designed to engage both surface and air targets.

Description

Second World War-era capital ships had four classes of artillery: the heavy main battery, intended to engage opposing battleships and ...

s in eight twin-gun turret

A gun turret (or simply turret) is a mounting platform from which weapons can be fired that affords protection, visibility and ability to turn and aim. A modern gun turret is generally a rotatable weapon mount that houses the crew or mechanis ...

s, four in sponson

Sponsons are projections extending from the sides of land vehicles, aircraft or watercraft to provide protection, stability, storage locations, mounting points for weapons or other devices, or equipment housing.

Watercraft

On watercraft, a spon ...

s on each side of the hull. The roofs of the gun turrets protruded above the level of the flight deck to allow them to fire across the deck at high elevations. Her light antiaircraft defences included six octuple mounts for QF 2-pounder ("pom-pom") antiaircraft gun

Anti-aircraft warfare, counter-air or air defence forces is the battlespace response to aerial warfare, defined by NATO as "all measures designed to nullify or reduce the effectiveness of hostile air action".AAP-6 It includes surface based, ...

s, two each fore and aft of her island, and two in sponsons on the port side of the hull.Hobbs 2013, p. 85

The completion of ''Illustrious'' was delayed two months to fit her with a Type 79Z early-warning radar

An early-warning radar is any radar system used primarily for the long-range detection of its targets, i.e., allowing defences to be alerted as ''early'' as possible before the intruder reaches its target, giving the air defences the maximum t ...

; she was the first aircraft carrier in the world to be fitted with radar before completion. This version of the radar had separate transmitting and receiving antennas which required a new mainmast

The mast of a sailing vessel is a tall spar, or arrangement of spars, erected more or less vertically on the centre-line of a ship or boat. Its purposes include carrying sails, spars, and derricks, and giving necessary height to a navigation lig ...

to be added to the aft end of the island to mount the transmitter.

The ''Illustrious''-class ships had a flight deck protected by of armour and the internal sides and ends of the hangars were thick. The hangar deck itself was thick and extended the full width of the ship to meet the top of the 4.5-inch waterline armour belt

Belt armor is a layer of heavy metal armor plated onto or within the outer hulls of warships, typically on battleships, battlecruisers and cruisers, and aircraft carriers.

The belt armor is designed to prevent projectiles from penetrating to ...

. The underwater defence system was a layered system of liquid- and air-filled compartments backed by a splinter bulkhead.

Wartime modifications

While under repair in 1941, ''Illustrious''s rear "round-down" was flattened to increase the usable length of the flight deck to .Friedman, p. 147 This increased her aircraft complement to 47 aircraft by use of a permanent deck park of 6 aircraft. Her light AA armament was also augmented by the addition of 10Oerlikon 20 mm

The Oerlikon 20 mm cannon is a series of autocannons, based on an original German Becker Type M2 20 mm cannon design that appeared very early in World War I. It was widely produced by Oerlikon Contraves and others, with various models empl ...

autocannon

An autocannon, automatic cannon or machine cannon is a fully automatic gun that is capable of rapid-firing large-caliber ( or more) armour-piercing, explosive or incendiary shells, as opposed to the smaller-caliber kinetic projectiles (bul ...

in single mounts. In addition the two steel fire curtains in the hangar were replaced by asbestos ones. After her return to the UK later that year, her Type 79Z radar was replaced by a Type 281 system and a Type 285 gunnery radar was mounted on one of the main fire-control directors. The additional crewmen, maintenance personnel and facilities needed to support these aircraft, weapons and sensors increased her complement to 1,326.

During her 1943 refits, the flight deck was modified to extend its usable length to , and "outriggers" were probably added at this time. These were 'U'-shaped beams that extended from the side of the flight deck into which aircraft tailwheels were placed. The aircraft were pushed back until the main wheels were near the edge of the flight deck to allow more aircraft to be stored on the deck. Twin Oerlikon mounts replaced most of the single mounts. Other twin mounts were added so that by May she had a total of eighteen twin and two single mounts. The Type 281 radar was replaced by an upgraded Type 281M, and a single-antenna Type 79M was added. Type 282 gunnery radars were added for each of the "pom-pom" directors, and the rest of the main directors were fitted with Type 285 radars. A Type 272 target-indicator radar was mounted above her bridge

A bridge is a structure built to span a physical obstacle (such as a body of water, valley, road, or rail) without blocking the way underneath. It is constructed for the purpose of providing passage over the obstacle, which is usually someth ...

. These changes increased her aircraft capacity to 57Hobbs 2013, p. 91 and caused her crew to grow to 1,831.

A year later, in preparation for her service against the Japanese in the Pacific, one starboard octuple "pom-pom" mount, directly abaft the island, was replaced by two 40 mm Bofors Bofors 40 mm gun is a name or designation given to two models of 40 mm calibre anti-aircraft guns designed and developed by the Swedish company Bofors:

*Bofors 40 mm L/60 gun - developed in the 1930s, widely used in World War II and into the 1990s

...

AA guns.Friedman, p. 148 Two more twin Oerlikon mounts were added, and her boilers were retubed. At this time her complement was 1,997 officers and enlisted men. By 1945, accumulated wear-and-tear as well as undiagnosed shock damage to ''Illustrious''s machinery caused severe vibrations in her centre propeller shaft at high speeds. In an effort to cure the problem, the propeller was removed, and the shaft was locked in place in February; these radical measures succeeded in reducing, but not eliminating, the vibrations and reduced the ship's speed to about .

Post-war modifications

''Illustrious'' had been badly damaged underwater by a bomb in April 1945, and was ordered home for repairs the following month. She began permanent repairs in June that were scheduled to last four months. The RN planned to fit her out as a flagship, remove her aft 4.5-inch guns in exchange for increased accommodation, and replace some of her Oerlikons with single two-pounder AA guns, but the end of the war in August caused the RN to reassess its needs. In September, it decided that the ''Illustrious'' would become the trials and training carrier for the Home Fleet and her repairs were changed into a lengthy refit that lasted until June 1946. Her complement was sharply reduced by her change in role and she retained her aft 4.5-inch guns. Her light AA armament now consisted of six octuple "pom-pom" mountings, eighteen single Oerlikons, and seventeen single and two twin Bofors mounts. The flight deck was extended forward, which increased her overall length to . The high-angle director atop the island was replaced with an American SM-1 fighter-direction radar, a Type 293M target-indication system was added, and the Type 281M was replaced with a prototype Type 960 early-warning radar. The sum total of the changes since her commissioning increased her full-load displacement by .Lyon, p. 221 In 1947 she carried five 8-barrel pom-poms, 17 Bofors and 16 Oerlikons. A five-bladed propeller was installed on her centre shaft although the increasing wear on her outer shafts later partially negated the reduction in vibration. While running trials in 1948, after another refit, she reached a maximum speed of from . Two years later, she made 29.2 knots from . At some point after 1948, the ship's light AA armament was reduced to two twin and nineteen single 40 mm guns and six Oerlikons.Construction and service

''Illustrious'', the fourth ship of her name, was ordered as part of the 1936 Naval Programme from

''Illustrious'', the fourth ship of her name, was ordered as part of the 1936 Naval Programme from Vickers-Armstrongs

Vickers-Armstrongs Limited was a British engineering conglomerate formed by the merger of the assets of Vickers Limited and Sir W G Armstrong Whitworth & Company in 1927. The majority of the company was nationalised in the 1960s and 1970s, w ...

on 13 April 1937.Hobbs 2013, p. 84 Construction was delayed by slow deliveries of her armour plates because the industry had been crippled by a lack of orders over the last 15 years as a result of the Washington Naval Treaty

The Washington Naval Treaty, also known as the Five-Power Treaty, was a treaty signed during 1922 among the major Allies of World War I, which agreed to prevent an arms race by limiting naval construction. It was negotiated at the Washington Nav ...

. As a consequence, her flight-deck armour had to be ordered from Vítkovice Mining and Iron Corporation in Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

. She was laid down

Laying the keel or laying down is the formal recognition of the start of a ship's construction. It is often marked with a ceremony attended by dignitaries from the shipbuilding company and the ultimate owners of the ship.

Keel laying is one o ...

at their Barrow-in-Furness

Barrow-in-Furness is a port town in Cumbria, England. Historically in Lancashire, it was incorporated as a municipal borough in 1867 and merged with Dalton-in-Furness Urban District in 1974 to form the Borough of Barrow-in-Furness. In 2023 t ...

shipyard two weeks later as yard number 732 and launched on 5 April 1939. She was christened by Lady Henderson, wife of the recently retired Third Sea Lord.Hobbs 2013, p. 90 ''Illustrious'' was then towed to Buccleuch Dock

Buccleuch Dock is one of the four docks which make up the Port of Barrow in Barrow-in-Furness, England. It was constructed between 1863 and 1872 to the same specification as the attached Devonshire Dock - the docks having been separated by a br ...

for fitting out

Fitting out, or outfitting, is the process in shipbuilding that follows the float-out/launching of a vessel and precedes sea trials. It is the period when all the remaining construction of the ship is completed and readied for delivery to her o ...

and Captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

Denis Boyd

Admiral Sir Denis William Boyd, (6 March 1891 – 21 January 1965) was a Royal Navy officer who served as Fifth Sea Lord from 1943 to 1945, and as Commander-in-Chief, Far East Fleet from 1946 to 1949.

Naval career Early career

Boyd joined the ...

was appointed to command her on 29 January 1940. She was commissioned on 16 April 1940 and, excluding her armament, she cost £2,295,000 to build.

While ''Illustrious'' was being moved in preparation for her acceptance trials on 24 April, the tugboat

A tugboat or tug is a marine vessel that manoeuvres other vessels by pushing or pulling them, with direct contact or a tow line. These boats typically tug ships in circumstances where they cannot or should not move under their own power, su ...

''Poolgarth'' capsized with the loss of three crewmen. The carrier conducted preliminary flying trials in the Firth of Clyde

The Firth of Clyde is the mouth of the River Clyde. It is located on the west coast of Scotland and constitutes the deepest coastal waters in the British Isles (it is 164 metres deep at its deepest). The firth is sheltered from the Atlantic ...

with six Fairey Swordfish

The Fairey Swordfish is a biplane torpedo bomber, designed by the Fairey Aviation Company. Originating in the early 1930s, the Swordfish, nicknamed "Stringbag", was principally operated by the Fleet Air Arm of the Royal Navy. It was also us ...

torpedo bomber

A torpedo bomber is a military aircraft designed primarily to attack ships with aerial torpedoes. Torpedo bombers came into existence just before the First World War almost as soon as aircraft were built that were capable of carrying the weight ...

s that had been craned aboard earlier. In early June, she loaded the personnel from 806, 815

__NOTOC__

Year 815 ( DCCCXV) was a common year starting on Monday (link will display the full calendar) of the Julian calendar.

Events

By place Byzantine Empire

* Byzantine–Bulgarian Treaty: Emperor Leo V the Armenian signs a 30-yea ...

, and 819 Squadrons at Devonport Royal Dockyard; 806 Squadron was equipped with Blackburn Skua

The Blackburn B-24 Skua was a carrier-based low-wing, two-seater, single- radial engine aircraft by the British aviation company Blackburn Aircraft. It was the first Royal Navy carrier-borne all-metal cantilever monoplane aircraft, as well as t ...

dive bomber

A dive bomber is a bomber aircraft that dives directly at its targets in order to provide greater accuracy for the bomb it drops. Diving towards the target simplifies the bomb's trajectory and allows the pilot to keep visual contact through ...

s and Fairey Fulmar

The Fairey Fulmar is a British carrier-borne reconnaissance aircraft/fighter aircraft which was developed and manufactured by aircraft company Fairey Aviation. It was named after the northern fulmar, a seabird native to the British Isles. The F ...

fighters, and the latter two squadrons were equipped with Swordfish. She began working up off Plymouth

Plymouth () is a port city status in the United Kingdom, city and unitary authority in South West England. It is located on the south coast of Devon, approximately south-west of Exeter and south-west of London. It is bordered by Cornwall to ...

, but the German conquest of France made this too risky, and ''Illustrious'' sailed for Bermuda later in the month to continue working up. This was complete by 23 July, when she arrived in the Clyde and flew off her aircraft. The ship was docked in Clydeside

Greater Glasgow is an urban settlement in Scotland consisting of all localities which are physically attached to the city of Glasgow, forming with it a single contiguous urban area (or conurbation). It does not relate to municipal government ...

for a minor refit the following day; she arrived in Scapa Flow

Scapa Flow viewed from its eastern end in June 2009

Scapa Flow (; ) is a body of water in the Orkney Islands, Scotland, sheltered by the islands of Mainland, Graemsay, Burray,S. C. George, ''Jutland to Junkyard'', 1973. South Ronaldsay a ...

on 15 August, and became the flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically the ...

of Rear Admiral

Rear admiral is a senior naval flag officer rank, equivalent to a major general and air vice marshal and above that of a commodore and captain, but below that of a vice admiral. It is regarded as a two star " admiral" rank. It is often rega ...

Lumley Lyster

Vice-Admiral Sir Arthur Lumley St George Lyster, (27 April 1888 – 4 August 1957) was a Royal Navy officer during the Second World War.

Naval career

After leaving Berkhamsted School, in 1902 Lyster joined HMS ''Britannia'' to train for a nav ...

. Her squadrons flew back aboard, and she sailed for the Mediterranean on 22 August with 15 Fulmars and 18 Swordfish aboard.

After refuelling in Gibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = "Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gibr ...

, ''Illustrious'' and the battleship

A battleship is a large armour, armored warship with a main artillery battery, battery consisting of large caliber guns. It dominated naval warfare in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The term ''battleship'' came into use in the late 1 ...

were escorted into the Mediterranean by Force H as part of Operation Hats, during which her Fulmars shot down five Italian bombers and her AA guns shot down two more. Now escorted by the bulk of the Mediterranean Fleet, eight of her Swordfish, together with some from the carrier , attacked the Italian seaplane

A seaplane is a powered fixed-wing aircraft capable of taking off and landing (alighting) on water.Gunston, "The Cambridge Aerospace Dictionary", 2009. Seaplanes are usually divided into two categories based on their technological characteri ...

base at Rhodes

Rhodes (; el, Ρόδος , translit=Ródos ) is the largest and the historical capital of the Dodecanese islands of Greece. Administratively, the island forms a separate municipality within the Rhodes regional unit, which is part of the S ...

on the morning of 3 September.McCart, p. 14 A few days after the Italian invasion of Egypt

The Italian invasion of Egypt () was an offensive in the Second World War, against British, Commonwealth and Free French forces in the Kingdom of Egypt. The invasion by the Italian 10th Army () ended border skirmishing on the frontier and ...

, ''Illustrious'' flew off 15 Swordfish during the moonlit night of 16/17 September to attack the port of Benghazi

Benghazi () , ; it, Bengasi; tr, Bingazi; ber, Bernîk, script=Latn; also: ''Bengasi'', ''Benghasi'', ''Banghāzī'', ''Binghāzī'', ''Bengazi''; grc, Βερενίκη ('' Berenice'') and ''Hesperides''., group=note (''lit. Son of he Ghaz ...

. Aircraft from 819 Squadron laid six mines in the harbour entrance while those from 815 Squadron sank the destroyer

In naval terminology, a destroyer is a fast, manoeuvrable, long-endurance warship intended to escort

larger vessels in a fleet, convoy or battle group and defend them against powerful short range attackers. They were originally developed ...

and two freighters totalling . The destroyer later struck one of the mines and sank. During the return voyage to Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandri ...

, the made an unsuccessful attack on the British ships. While escorting a convoy to Malta on 29 September, the carrier's Fulmars broke up attacks by Italian high-level and torpedo bombers, shooting down one for the loss of one fighter. While returning from another convoy escort mission, the Swordfish of ''Illustrious'' and ''Eagle'' attacked the Italian airfield on the island of Leros on the evening of 13/14 October.

Battle of Taranto

Upon his arrival in the Mediterranean, Lyster proposed a carrier airstrike on the Italian fleet at its base in

Upon his arrival in the Mediterranean, Lyster proposed a carrier airstrike on the Italian fleet at its base in Taranto

Taranto (, also ; ; nap, label=Tarantino, Tarde; Latin: Tarentum; Old Italian: ''Tarento''; Ancient Greek: Τάρᾱς) is a coastal city in Apulia, Southern Italy. It is the capital of the Province of Taranto, serving as an important comme ...

, as the Royal Navy had been planning since the Abyssinia Crisis

The Abyssinia Crisis (; ) was an international crisis in 1935 that originated in what was called the Walwal incident during the ongoing conflict between the Kingdom of Italy and the Empire of Ethiopia (then commonly known as "Abyssinia"). The Le ...

of 1935, and Admiral Andrew Cunningham, commander of the Mediterranean Fleet, approved the idea by 22 September 1940. The attack, with both available carriers, was originally planned for 21 October, the anniversary of the Battle of Trafalgar, but a hangar fire aboard ''Illustrious'' on 18 October forced its postponement until 11 November when the next favourable phase of the moon occurred. The fire destroyed three Swordfish and heavily damaged two others, but they were replaced by aircraft from ''Eagle'', whose contaminated fuel tanks prevented her from participating in the attack.McCart, p. 15

Repairs were completed before the end of the month, and she escorted a convoy to Greece, during which her Fulmars shot down one shadowing CANT Z.506

The CANT Z.506 ''Airone'' ( Italian: Heron) was a trimotor floatplane produced by CANT from 1935. It served as a transport and postal aircraft with the Italian airline "Ala Littoria". It established 10 world records in 1936 and another 10 in 193 ...

B floatplane

A floatplane is a type of seaplane with one or more slender floats mounted under the fuselage to provide buoyancy. By contrast, a flying boat uses its fuselage for buoyancy. Either type of seaplane may also have landing gear suitable for land, m ...

. She sailed from Alexandria on 6 November, escorted by the battleships , , and ''Valiant'', two light cruiser

A light cruiser is a type of small or medium-sized warship. The term is a shortening of the phrase "light armored cruiser", describing a small ship that carried armor in the same way as an armored cruiser: a protective belt and deck. Prior to th ...

s, and 13 destroyers, to provide air cover for another convoy to Malta. At this time her air group was reinforced by several of ''Eagle''s Gloster Sea Gladiators supplementing the fighters of 806 Squadron as well as torpedo bombers from 813 and 824 Squadrons.Brown, J. D., p. 45 The former aircraft were carried "...as a permanent deck park..."Brown 1971, p. 244 and they shot down a CANT Z.501

The CANT Z.501 ''Gabbiano'' (Italian: '' Gull'')

was a high-wing central-hull flying boat, with two outboard floats. It was powered by a single engine installed in the middle of the main-planeAngelucci and Matricardi 1978, p. 186. and had a crew ...

seaplane two days later. Later that day seven Savoia-Marchetti SM.79

The Savoia-Marchetti SM.79 ''Sparviero'' (Italian for sparrowhawk) was a three-engined Italian medium bomber developed and manufactured by aviation company Savoia-Marchetti. It may be the best-known Italian aeroplane of the Second World War. ...

medium bombers were intercepted by three Fulmars, which claimed to have shot down one bomber and damaged another. In reality, they heavily damaged three of the Italian aircraft. A Z.501 searching for the fleet was shot down on 10 November by a Fulmar and another on the 11th. A flight of nine SM.79s was intercepted later that day and the Fulmars claimed to have damaged one of the bombers, although it actually failed to return to base. Three additional Fulmars had been flown aboard from ''Ark Royal'' a few days earlier, when both carriers were near Malta; that brought its strength up to 15 Fulmars, 24 Swordfish, and two to four Sea Gladiators. Three Swordfish crashed shortly after take-off on 10 and 11 November, probably due to fuel contamination, and the maintenance crewmen spent all day laboriously draining all the fuel tanks and refilling them with clean petrol. This left only 21 aircraft available for the attack.

Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) an ...

(RAF) had positioned a Short Sunderland

The Short S.25 Sunderland is a British flying boat patrol bomber, developed and constructed by Short Brothers for the Royal Air Force (RAF). The aircraft took its service name from the town (latterly, city) and port of Sunderland in North Ea ...

flying boat

A flying boat is a type of fixed-winged seaplane with a hull, allowing it to land on water. It differs from a floatplane in that a flying boat's fuselage is purpose-designed for floatation and contains a hull, while floatplanes rely on fuselag ...

off the harbour to search for any movement to or from the port and this was detected at 17:55 by acoustic locators and again at 20:40, alerting the defenders. The noise of the on-coming first airstrike was heard at 22:25 and the anti-aircraft guns defending the port opened fire shortly afterwards, as did those on the ships in the harbour. The torpedo-carrying aircraft of the first wave scored one hit on the battleship and two on the recently completed battleship while the two flare droppers bombed the oil storage depot with little effect. The four aircraft loaded with bombs set one hangar in the seaplane base on fire and hit the destroyer with one bomb that failed to detonate. The destroyer , or ''Conte di Cavour'', shot down the aircraft that put a torpedo into the latter ship, but the remaining aircraft returned to ''Illustrious''.

One torpedo-carrying aircraft of the second wave was forced to return when its long-range external fuel tank fell off, but the others hit the ''Littorio'' once more and the was hit once when they attacked beginning at 23:55. The two flare droppers also bombed the oil storage depot with minimal effect, and one bomb penetrated through the hull of the heavy cruiser

The heavy cruiser was a type of cruiser, a naval warship designed for long range and high speed, armed generally with naval guns of roughly 203 mm (8 inches) in caliber, whose design parameters were dictated by the Washington Naval T ...

without detonating. One torpedo bomber was shot down, but the other aircraft returned. A follow on airstrike was planned for the next night based on the pessimistic assessments of the aircrews, but it was cancelled due to bad weather. Reconnaissance photos taken by the R.A.F.

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and ...

showed three battleships with their decks awash and surrounded by pools of oil. The two airstrikes had changed the balance of power in the Mediterranean by rendering the ''Conte di Cavour'' unavailable for the rest of the war, and badly damaging the ''Littorio'' and the ''Duilio''.

Subsequent operations in the Mediterranean

While en route to Alexandria the ship's Fulmars engaged four CANT Z.506Bs, claiming three shot down and the fourth damaged, although Italian records indicate the loss of only two aircraft on 12 November. Two weeks later, 15 Swordfish attacked Italian positions on Leros, losing one Swordfish. While off Malta two days later, six of the carrier's fighters engaged an equal number ofFiat CR.42 Falco

The Fiat CR.42 ''Falco'' ("Falcon", plural: ''Falchi'') is a single-seat sesquiplane fighter developed and produced by Italian aircraft manufacturer Fiat Aviazione. It served primarily in the Italian in the 1930s and during the Second World Wa ...

biplane

A biplane is a fixed-wing aircraft with two main wings stacked one above the other. The first powered, controlled aeroplane to fly, the Wright Flyer, used a biplane wing arrangement, as did many aircraft in the early years of aviation. While a ...

fighters, shooting down one and damaging two others. One Fulmar was lightly damaged during the battle. On the night of 16/17 December, 11 Swordfish bombed Rhodes and the island of Stampalia with little effect. Four days later ''Illustrious''s aircraft attacked two convoys near the Kerkennah Islands

Kerkennah Islands ( aeb, قرقنة '; Ancient Greek: ''Κέρκιννα Cercinna''; Spanish:''Querquenes'') are a group of islands lying off the east coast of Tunisia in the Gulf of Gabès, at . The Islands are low-lying, being no more than abo ...

and sank two merchant ships totalling . On the morning of 22 December, 13 Swordfish attacked Tripoli harbour, starting fires and hitting warehouses multiple times. The ship arrived back at Alexandria two days later.

On 7 January 1941, ''Illustrious'' set sail to provide air cover for convoys to

On 7 January 1941, ''Illustrious'' set sail to provide air cover for convoys to Piraeus

Piraeus ( ; el, Πειραιάς ; grc, Πειραιεύς ) is a port city within the Athens urban area ("Greater Athens"), in the Attica region of Greece. It is located southwest of Athens' city centre, along the east coast of the Saro ...

, Greece and Malta as part of Operation Excess

Operation Excess was a series of British supply convoys to Malta, Alexandria and Greece in January 1941. The operation encountered the first presence of ''Luftwaffe'' anti-shipping aircraft in the Mediterranean Sea. All the convoyed freighters rea ...

. For this operation, her fighters were reinforced by a detachment of three Fulmars from 805 Squadron. During the morning of 10 January, her Swordfish attacked an Italian convoy without significant effect. Later that morning three of the five Fulmars on Combat Air Patrol

Combat air patrol (CAP) is a type of flying mission for fighter aircraft. A combat air patrol is an aircraft patrol provided over an objective area, over the force protected, over the critical area of a combat zone, or over an air defense area, ...

(CAP) engaged three SM.79s at low altitude, claiming one shot down. One Fulmar was damaged and forced to return to the carrier, while the other two exhausted their ammunition and fuel during the combat and landed at Hal Far

HAL may refer to:

Aviation

* Halali Airport (IATA airport code: HAL) Halali, Oshikoto, Namibia

* Hawaiian Airlines (ICAO airline code: HAL)

* HAL Airport, Bangalore, India

* Hindustan Aeronautics Limited an Indian aerospace manufacturer of fig ...

airfield on Malta. The remaining pair engaged a pair of torpedo-carrying SM.79s, damaging one badly enough that it crashed upon landing. They were low on ammunition and out of position, as they chased the Italian aircraft over from ''Illustrious''. The carrier launched four replacements at 12:35, just when 24–36 Junkers Ju 87 Stuka

The Junkers Ju 87 or Stuka (from ''Sturzkampfflugzeug'', "dive bomber") was a German dive bomber and ground-attack aircraft. Designed by Hermann Pohlmann, it first flew in 1935. The Ju 87 made its combat debut in 1937 with the Luftwaffe's Cond ...

dive bombers of the First Group/Dive Bomber Wing 1 (I. Gruppe/ Sturzkampfgeschwader (StG) 1) and the Second Group/Dive Bomber Wing 2 (II. Gruppe/StG 2

''Sturzkampfgeschwader'' 2 (StG 2) ''Immelmann'' was a Luftwaffe dive bomber-wing of World War II. It was named after the World War I aviator Max Immelmann. It served until its dissolution in October 1943. The wing operated the Junkers Ju 87 ...

) began their attack, led by Paul-Werner Hozzel. Another pair were attempting to take off when the first bomb struck just forward of the aft lift, destroying the Fulmar whose engine had failed to start and detonating high in the lift well; the other aircraft took off and engaged the Stukas as they pulled out of their dive.

The ship was hit five more times in this attack, one of which penetrated the un-armoured aft lift and detonated beneath it, destroying it and the surrounding structure. One bomb struck and destroyed the starboard forward "pom-pom" mount closest to the island, while another passed through the forwardmost port "pom-pom" mount and failed to detonate, although it did start a fire. One bomb penetrated the outer edge of the forward port flight deck and detonated about above the water, riddling the adjacent hull structure with holes which caused flooding in some compartments and starting a fire. The most damaging hit was a large bomb that penetrated through the deck armour forward of the aft lift and detonated 10 feet above the hangar deck. The explosion started a severe fire, destroyed the rear fire sprinkler system, bent the forward lift like a hoop and shredded the fire curtains into lethal splinters. It also blew a hole in the hangar deck, damaging areas three decks below. The Stukas also near-missed ''Illustrious'' with two bombs, which caused minor damage and flooding. The multiple hits at the aft end of the carrier knocked out her steering gear, although it was soon repaired.

Another attack by 13 Ju 87s at 13:20 hit the ship once more in the aft lift well, which again knocked out her steering and reduced her speed to . This attack was intercepted by six of the ship's Fulmars which had rearmed and refuelled ashore after they had dropped their bombs, but only two of the dive bombers were damaged before the Fulmars ran out of ammunition. The carrier, steering only by using her engines, was attacked several more times before she entered Grand Harbour

The Grand Harbour ( mt, il-Port il-Kbir; it, Porto Grande), also known as the Port of Valletta, is a natural harbour on the island of Malta. It has been substantially modified over the years with extensive docks ( Malta Dockyard), wharves, a ...

's breakwater

Breakwater may refer to:

* Breakwater (structure), a structure for protecting a beach or harbour

Places

* Breakwater, Victoria, a suburb of Geelong, Victoria, Australia

* Breakwater Island, Antarctica

* Breakwater Islands, Nunavut, Canada

* Br ...

at 21:04, still on fire. The attacks killed 126 officers and men and wounded 91. Nine Swordfish and five Fulmars were destroyed during the attack. One additional Swordfish, piloted by Lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations.

The meaning of lieutenant differs in different militaries (see comparative military ranks), but it is often ...

Charles Lamb

Charles Lamb (10 February 1775 – 27 December 1834) was an English essayist, poet, and antiquarian, best known for his '' Essays of Elia'' and for the children's book '' Tales from Shakespeare'', co-authored with his sister, Mary Lamb (1764� ...

, was attempting to land when the bombs began to strike and was forced to ditch

A ditch is a small to moderate divot created to channel water. A ditch can be used for drainage, to drain water from low-lying areas, alongside roadways or fields, or to channel water from a more distant source for plant irrigation. Ditches ar ...

when it ran out of fuel; the crew was rescued by the destroyer . The British fighters claimed to have shot down five Ju 87s, with the fleet's anti-aircraft fire claiming three others. Germans records show the loss of three Stukas, with another forced to make an emergency landing.Brown 1971, p. 246; Brown, J. D., p. 48; Friedman, p. 147; Hobbs 2013, p. 90; McCart, pp. 17, 19; Shores, Cull & Malizia 1987b, pp. 110–111, 114–115

While her steering was being repaired in Malta, the ''Illustrious'' was bombed again on 16 January by 17

While her steering was being repaired in Malta, the ''Illustrious'' was bombed again on 16 January by 17 Junkers Ju 88

The Junkers Ju 88 is a German World War II ''Luftwaffe'' twin-engined multirole combat aircraft. Junkers Aircraft and Motor Works (JFM) designed the plane in the mid-1930s as a so-called '' Schnellbomber'' ("fast bomber") that would be too fast ...

medium bombers and 44 Stukas. The pilots of 806 Squadron claimed to have shot down two of the former and possibly damaged another pair, but a 500 kg bomb penetrated her flight deck aft of the rear lift and detonated in the captain's day cabin; several other bombs nearly hit the ship but only caused minor damage. Two days later, one of three Fulmars that intercepted an Axis air raid on the Maltese airfields was shot down with no survivors. Only one Fulmar was serviceable on 19 January, when the carrier was attacked several times and it was shot down. ''Illustrious'' was not struck during these attacks but was near-missed several times and the resulting shock waves from their detonations dislodged enough hull plating to cause an immediate 5-degree list

A ''list'' is any set of items in a row. List or lists may also refer to:

People

* List (surname)

Organizations

* List College, an undergraduate division of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America

* SC Germania List, German rugby unio ...

, cracked the cast-iron foundations of her port turbine, and damaged other machinery. The naval historian J. D. Brown noted that "There is no doubt that the armoured deck saved her from destruction; no other carrier took anything like this level of punishment and survived."

Without aircraft aboard, she sailed to Alexandria on 23 January escorted by four destroyers, for temporary repairs that lasted until 10 March. Boyd was promoted to rear admiral on 18 February and relieved Lyster as Rear Admiral Aircraft Carriers. He transferred his flag to ''Formidable'' when she arrived at Alexandria on 10 March, just before ''Illustrious'' sailed for Port Said

Port Said ( ar, بورسعيد, Būrsaʿīd, ; grc, Πηλούσιον, Pēlousion) is a city that lies in northeast Egypt extending about along the coast of the Mediterranean Sea, north of the Suez Canal. With an approximate population of 6 ...

to begin her transit of the Suez Canal

The Suez Canal ( arz, قَنَاةُ ٱلسُّوَيْسِ, ') is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea through the Isthmus of Suez and dividing Africa and Asia. The long canal is a popula ...

. The Germans had laid mines in the canal earlier. Clearing the mines and the ships sunk by them was a slow process and ''Illustrious'' did not reach Suez Bay until 20 March. The ship then sailed for Durban

Durban ( ) ( zu, eThekwini, from meaning 'the port' also called zu, eZibubulungwini for the mountain range that terminates in the area), nicknamed ''Durbs'',Ishani ChettyCity nicknames in SA and across the worldArticle on ''news24.com'' from ...

, South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring coun ...

, to have the extent of her underwater damage assessed in the drydock there. She reached Durban on 4 April and remained there for two weeks. The ship ultimately arrived at the Norfolk Navy Yard

The Norfolk Naval Shipyard, often called the Norfolk Navy Yard and abbreviated as NNSY, is a U.S. Navy facility in Portsmouth, Virginia, for building, remodeling and repairing the Navy's ships. It is the oldest and largest industrial facility t ...

in the United States on 12 May for permanent repairs.

Some important modifications were made to her flight deck arrangements, including the installation of a new aft lift and modification of the catapult for use by American-built aircraft. Her light antiaircraft armament was also augmented during the refit. Captain Lord Louis Mountbatten

Louis Francis Albert Victor Nicholas Mountbatten, 1st Earl Mountbatten of Burma (25 June 1900 – 27 August 1979) was a British naval officer, colonial administrator and close relative of the British royal family. Mountbatten, who was of German ...

relieved her acting captain on 12 August, although he did not arrive aboard her until 28 August. He was almost immediately sent on a speaking tour to influence American public opinion, until he was recalled home in October and relieved by Captain A. G. Talbot on 1 October. The work was completed in November and ''Illustrious'' departed on 25 October, for trials off Jamaica

Jamaica (; ) is an island country situated in the Caribbean Sea. Spanning in area, it is the third-largest island of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean (after Cuba and Hispaniola). Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, and west of Hispa ...

and to load the dozen Swordfish of 810 and 829 Squadrons. She returned to Norfolk on 9 December, to rendezvous with ''Formidable'', which had also been repaired there, and the carriers sailed for home three days later. On the night of 15/16 December, ''Illustrious'' collided with ''Formidable'' in a moderate storm. Neither ship was seriously damaged, but ''Illustrious'' had to reduce speed to shore up sprung bulkheads in the bow and conduct temporary repairs to the forward flight deck. She arrived at Greenock

Greenock (; sco, Greenock; gd, Grianaig, ) is a town and administrative centre in the Inverclyde council area in Scotland, United Kingdom and a former burgh within the historic county of Renfrewshire, located in the west central Lowland ...

on 21 December and permanent repairs were made from 30 December to late February 1942 at Cammell Laird

Cammell Laird is a British shipbuilding company. It was formed from the merger of Laird Brothers of Birkenhead and Johnson Cammell & Co of Sheffield at the turn of the twentieth century. The company also built railway rolling stock until 1929, ...

's shipyard in Birkenhead

Birkenhead (; cy, Penbedw) is a town in the Metropolitan Borough of Wirral, Merseyside, England; historically, it was part of Cheshire until 1974. The town is on the Wirral Peninsula, along the south bank of the River Mersey, opposite Liv ...

. While working up her air group in March, reinforced by the Grumman Martlet

The Grumman F4F Wildcat is an American carrier-based fighter aircraft that entered service in 1940 with the United States Navy, and the British Royal Navy where it was initially known as the Martlet. First used by the British in the North Atlant ...

fighters (the British name of the F4F Wildcat) of 881

__NOTOC__

Year 881 ( DCCCLXXXI) was a common year starting on Sunday of the Julian calendar.

Events

By place Europe

* February 12 – King Charles the Fat, the third son of the late Louis the German, is crowned as Holy Roman Emper ...

and 882 Squadrons, she conducted trials of a "hooked" Supermarine Spitfire

The Supermarine Spitfire is a British single-seat fighter aircraft used by the Royal Air Force and other Allied countries before, during, and after World War II. Many variants of the Spitfire were built, from the Mk 1 to the Rolls-Royce Gri ...

fighter, the prototype of the Seafire

''SeaFire'', first published in 1994, was the fourteenth novel by John Gardner featuring Ian Fleming's secret agent, James Bond (including Gardner's novelization of ''Licence to Kill''). Carrying the Glidrose Publications copyright, it was f ...

.

In the Indian Ocean

The conquest of British Malaya and the

The conquest of British Malaya and the Dutch East Indies

The Dutch East Indies, also known as the Netherlands East Indies ( nl, Nederlands(ch)-Indië; ), was a Dutch colony consisting of what is now Indonesia. It was formed from the nationalised trading posts of the Dutch East India Company, whic ...

in early 1942 opened the door for Japanese advances into the Indian Ocean. The Vichy French-controlled island of Madagascar

Madagascar (; mg, Madagasikara, ), officially the Republic of Madagascar ( mg, Repoblikan'i Madagasikara, links=no, ; french: République de Madagascar), is an island country in the Indian Ocean, approximately off the coast of East Afric ...

stood astride the line of communication between India and the UK and the British were worried that the French would accede to occupation of the island as they had to the Japanese occupation of French Indochina

In the European summer of 1940 Germany rapidly defeated the French Third Republic, and colonial administration of French Indochina (modern-day Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia) passed to the French State (Vichy France). Many concessions were granted t ...

in 1940. Preventing this required a preemptive invasion of Diego Suarez scheduled for May 1942. ''Illustrious'' had her work up cut short on 19 March to prepare to join the Eastern Fleet in the Indian Ocean and participate in the attack. She sailed four days later, having embarked twenty-one Swordfish, nine Martlet IIs of 881 Squadron and six Martlet Is of 882 Squadron,Jones, p. 108 and two Fulmar fighters prior to escorting a troop convoy carrying some of the men allocated for the assault. A hangar fire broke out on 2 April that destroyed 11 aircraft and killed one crewman, but failed to cause any serious damage to the ship. Repairs were made in Freetown

Freetown is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Sierra Leone. It is a major port city on the Atlantic Ocean and is located in the Western Area of the country. Freetown is Sierra Leone's major urban, economic, financial, cultural, educ ...

, Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone,)]. officially the Republic of Sierra Leone, is a country on the southwest coast of West Africa. It is bordered by Liberia to the southeast and Guinea surrounds the northern half of the nation. Covering a total area of , Sierr ...

, where her destroyed aircraft were replaced and augmented by twelve additional Martlet II fighters from HMS Archer (D78), HMS ''Archer'', while two Martlet I aircraft were, in turn, transferred to ''Archer'', bringing ''Illustrious''s total aircraft complement to 47.Jones, pp. 106–110 After her stay at Freetown, ''Illustrious'' proceeded to Durban; during the voyage her staff also fitted ASV radar to the replacement Swordfish. One Martlet I was fitted with folding wings.

''Illustrious''s aircraft were tasked to attack French naval units and shipping and to defend the invasion fleet, while her half-sister provided air support for the ground forces. For the operation the carrier's air group numbered 25 Martlets, 1 night-fighting Fulmar and 21 Swordfish, and was consequently was forced to have a permanent deck park of 5 Martlets and one Swordfish. Before dawn on 5 May, she launched 18 Swordfish together with 8 Martlets. The first flight of 6 Swordfish, carrying torpedoes, unsuccessfully attacked the aviso

An ''aviso'' was originally a kind of dispatch boat or "advice boat", carrying orders before the development of effective remote communication.

The term, derived from the Portuguese and Spanish word for "advice", "notice" or "warning", an ...

, but sank the armed merchant cruiser

An armed merchantman is a merchant ship equipped with guns, usually for defensive purposes, either by design or after the fact. In the days of sail, piracy and privateers, many merchantmen would be routinely armed, especially those engaging in lo ...

. The second flight, carrying depth charge

A depth charge is an anti-submarine warfare (ASW) weapon. It is intended to destroy a submarine by being dropped into the water nearby and detonating, subjecting the target to a powerful and destructive hydraulic shock. Most depth charges use h ...

s, sank the submarine while the third flight dropped leaflets over the defenders before attacking an artillery battery

In military organizations, an artillery battery is a unit or multiple systems of artillery, mortar systems, rocket artillery, multiple rocket launchers, surface-to-surface missiles, ballistic missiles, cruise missiles, etc., so grouped to f ...

and ''D'Entrecasteaux''. One aircraft of the third flight was forced to make an emergency landing and its crew was captured by the French. Later in the day, ''D'Entrecasteaux'' attempted to put to sea, but she was successfully bombed by an 829 Squadron Swordfish and deliberately run aground to avoid sinking. Three other Swordfish completed her destruction. The next morning, Martlets from 881 Squadron intercepted three Potez 63.11 reconnaissance bombers, shooting down two and forcing the other to retreat, while Swordfish dropped dummy parachutists as a diversion. One patrolling Swordfish sank the submarine and another spotted for ships bombarding French defences. On the morning of 7 May, Martlets from 881 Squadron intercepted three Morane-Saulnier M.S.406 fighters on a reconnaissance mission. All three were shot down for the loss of one Martlet. In addition to the other losses enumerated, 882 Squadron's Fulmar was shot down while providing ground support. ''Illustrious aircraft flew 209 sorties and suffered six deck landing crashes, including four by Martlets.

She was then formally assigned to the Eastern Fleet and, after a short refit in Durban, sailed to

She was then formally assigned to the Eastern Fleet and, after a short refit in Durban, sailed to Colombo

Colombo ( ; si, කොළඹ, translit=Koḷam̆ba, ; ta, கொழும்பு, translit=Koḻumpu, ) is the executive and judicial capital and largest city of Sri Lanka by population. According to the Brookings Institution, Colombo me ...

, Ceylon

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

, and became the flagship of the Rear Admiral Aircraft Carriers, Eastern Fleet, Denis Boyd, her former captain. At the beginning of August, the ship participated in Operation Stab, a decoy invasion of the Andaman Islands

The Andaman Islands () are an archipelago in the northeastern Indian Ocean about southwest off the coasts of Myanmar's Ayeyarwady Region. Together with the Nicobar Islands to their south, the Andamans serve as a maritime boundary between t ...

to distract the Japanese when the Americans were invading the island of Guadalcanal in the South Pacific. Captain Robert Cunliffe relieved Talbott on 22 August. On 10 September the carrier covered the amphibious landing that opened Operation Streamline Jane, the occupation of the remainder of Madagascar, and the landing at Tamatave

Toamasina (), meaning "like salt" or "salty", unofficially and in French Tamatave, is the capital of the Atsinanana region on the east coast of Madagascar on the Indian Ocean. The city is the chief seaport of the country, situated northeast of it ...

eight days later, but no significant resistance was encountered and her aircraft were not needed. For this operation she had aboard six Fulmars of 806 Squadron, 23 Martlets of 881 Squadron and 18 Swordfish of 810 and 829 Squadrons.

European waters

After a farewell visit from the Eastern Fleet commander, Admiral Sir

After a farewell visit from the Eastern Fleet commander, Admiral Sir James Somerville

Admiral of the Fleet Sir James Fownes Somerville, (17 July 1882 – 19 March 1949) was a Royal Navy officer. He served in the First World War as fleet wireless officer for the Mediterranean Fleet where he was involved in providing naval suppo ...

on 12 January 1943, ''Illustrious'' sailed for home the next day. She flew off her aircraft to Gibraltar on 31 January and continued on to the Clyde where she arrived five days later. She conducted deck-landing trials for prototypes of the Blackburn Firebrand and Fairey Firefly

The Fairey Firefly is a Second World War-era carrier-borne fighter aircraft and anti-submarine aircraft that was principally operated by the Fleet Air Arm (FAA). It was developed and built by the British aircraft manufacturer Fairey Avia ...

fighters, as well as the Fairey Barracuda

The Fairey Barracuda was a British carrier-borne torpedo and dive bomber designed by Fairey Aviation. It was the first aircraft of this type operated by the Royal Navy's Fleet Air Arm (FAA) to be fabricated entirely from metal.

The Barracuda ...

dive/torpedo bomber from 8 to 10 February. On 26 February she began a refit at Birkenhead that lasted until 7 June during which her flight deck was extended, new radar

Radar is a detection system that uses radio waves to determine the distance (''ranging''), angle, and radial velocity of objects relative to the site. It can be used to detect aircraft, Marine radar, ships, spacecraft, guided missiles, motor v ...

s were installed, her light anti-aircraft armament was augmented, and two new arrestor wire

An arresting gear, or arrestor gear, is a mechanical system used to rapidly decelerate an aircraft as it lands. Arresting gear on aircraft carriers is an essential component of naval aviation, and it is most commonly used on CATOBAR and STOBA ...

s were fitted aft of the rear lift which increased her effective landing area. While conducting her post-refit trials, she also conducted flying trials for Martlet Vs and Barracudas. Both sets of trials were completed by 18 July, by which time the ''Illustrious'' had joined the Home Fleet.

On 26 July, she sortied for the Norwegian Sea as part of Operation Governor, together with the battleship , the American battleship , and the light carrier , an attempt to fool the Germans into thinking that Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

was not the only objective for an Allied invasion. 810 Squadron was the only unit retained from her previous air group and it had been re-equipped with Barracudas during her refit. Her fighter complement was augmented by 878 and 890 Squadrons, each with 10 Martlet Vs, and 894 Squadron with 10 Seafire IICs. These latter aircraft lacked folding wings and could not fit on the lifts. The British ships were spotted by Blohm & Voss BV 138

The Blohm & Voss BV 138 ''Seedrache'' (Sea Dragon), but nicknamed ''Der Fliegende Holzschuh'' ("flying clog",Nowarra 1997, original German title of the Schiffer book. from the side-view shape of its fuselage, as well as a play on the title of th ...

flying boats and 890 Squadron shot down two of them before the fleet returned to Scapa Flow on 29 July. She transferred to Greenock at the end of the month and sailed on 5 August to provide air cover for the ocean liner

An ocean liner is a passenger ship primarily used as a form of transportation across seas or oceans. Ocean liners may also carry cargo or mail, and may sometimes be used for other purposes (such as for pleasure cruises or as hospital ships).

Ca ...

as she conveyed Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is ...

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

to the Quebec Conference. Once the convoy was out of range of German aircraft, the ''Illustrious'' left the convoy and arrived back at Greenock on 8 August.

Together with the ''Unicorn'', she sailed for the Mediterranean on 13 August to prepare for the landings at Salerno (Operation Avalanche), reaching Malta a week later. Her air group was reinforced at this time by four more Martlets each for 878 and 890 Squadrons. She was assigned to

Together with the ''Unicorn'', she sailed for the Mediterranean on 13 August to prepare for the landings at Salerno (Operation Avalanche), reaching Malta a week later. Her air group was reinforced at this time by four more Martlets each for 878 and 890 Squadrons. She was assigned to Force H

Force H was a British naval formation during the Second World War. It was formed in 1940, to replace French naval power in the western Mediterranean removed by the French armistice with Nazi Germany. The force occupied an odd place within the ...

for the operation which was tasked to protect the amphibious force from attack by the Italian Fleet and provide air cover for the carriers supporting the assault force. The Italians made no effort to attack the Allied forces, and the most noteworthy thing that any of her aircraft did was when one of 890 Squadron's Martlets escorted a surrendering Italian aircraft to Sicily. Before the ''Illustrious'' steamed for Malta she transferred six Seafires to the ''Unicorn'' to replace some of the latter's aircraft wrecked in deck-landing accidents. Four of these then flew ashore to conduct operations until they rejoined ''Illustrious'' on 14 September at Malta.

She then returned to Britain on 18 October for a quick refit at Birkenhead that included further improvements to the flight deck and the reinforcement of her light anti-aircraft armament. She embarked the Barracudas of 810 and 847 Squadrons of No. 21 Naval Torpedo-Bomber Reconnaissance Wing on 27 November before beginning her work up three days later. No. 15 Naval Fighter Wing with the Vought Corsairs of 1830

It is known in European history as a rather tumultuous year with the Revolutions of 1830 in France, Belgium, Poland, Switzerland and Italy.

Events January–March

* January 11 – LaGrange College (later the University of North Alabama) b ...

and 1833 Squadrons were still training ashore and flew aboard before the work up was finished on 27 December.

Return to the Indian Ocean

''Illustrious'' departed Britain on 30 December and arrived in

''Illustrious'' departed Britain on 30 December and arrived in Trincomalee

Trincomalee (; ta, திருகோணமலை, translit=Tirukōṇamalai; si, ත්රිකුණාමළය, translit= Trikuṇāmaḷaya), also known as Gokanna and Gokarna, is the administrative headquarters of the Trincomalee Dis ...

, Ceylon, on 28 January 1944. She spent most of the next several months training although she participated in several sorties with the Eastern Fleet searching for Japanese warships in the Bay of Bengal

The Bay of Bengal is the northeastern part of the Indian Ocean, bounded on the west and northwest by India, on the north by Bangladesh, and on the east by Myanmar and the Andaman and Nicobar Islands of India. Its southern limit is a line bet ...

and near the coast of Sumatra

Sumatra is one of the Sunda Islands of western Indonesia. It is the largest island that is fully within Indonesian territory, as well as the sixth-largest island in the world at 473,481 km2 (182,812 mi.2), not including adjacent i ...

. The fleet departed Trincomalee on 21 March to rendezvous with the American carrier in preparation for combined operations against the Japanese facilities in the Dutch East Indies and the Andaman Islands. The first operation carried out by both carriers was an airstrike on the small naval base at Sabang at the northern tip of Sumatra (Operation Cockpit

Operation Cockpit was an Allied attack against the Japanese-held island of Sabang on 19 April 1944. It was conducted by aircraft flying from British and American aircraft carriers and targeted Japanese shipping and airfields. A small number of ...

). The carrier's air group consisted of 21 Barracudas and 28 Corsairs for the operation; ''Illustrious'' launched 17 of the former escorted by 13 of the latter on the morning of 19 April. The American bombers attacked the shipping in the harbour while the British aircraft attacked the shore installations. The oil storage tanks were destroyed and the port facilities badly damaged by the Barracudas. There was no aerial opposition and the fighters claimed to have destroyed 24 aircraft on the ground. All British aircraft returned safely although one American fighter was forced to ditch during the return home.

The ''Saratoga'' was ordered to depart for home for a refit by 19 May and Somerville wanted to mount one more attack as she was leaving the Indian Ocean. He chose the naval base and oil refinery

An oil refinery or petroleum refinery is an industrial process plant where petroleum (crude oil) is transformed and refined into useful products such as gasoline (petrol), diesel fuel, asphalt base, fuel oils, heating oil, kerosene, liq ...

at Surabaya

Surabaya ( jv, ꦱꦸꦫꦧꦪ or jv, ꦯꦹꦫꦨꦪ; ; ) is the capital city of the Indonesian province of East Java and the second-largest city in Indonesia, after Jakarta. Located on the northeastern border of Java island, on the M ...

, Java