Great American Biotic Interchange on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Great American Biotic Interchange (commonly abbreviated as GABI), also known as the Great American Interchange and the Great American Faunal Interchange, was an important late

The Great American Biotic Interchange (commonly abbreviated as GABI), also known as the Great American Interchange and the Great American Faunal Interchange, was an important late

After the late

After the late

Marsupials appear to have traveled via Gondwanan land connections from South America through Antarctica to Australia in the late

Marsupials appear to have traveled via Gondwanan land connections from South America through Antarctica to Australia in the late  Xenarthrans are a curious group of mammals that developed morphological adaptations for specialized diets very early in their history. In addition to those extant today (

Xenarthrans are a curious group of mammals that developed morphological adaptations for specialized diets very early in their history. In addition to those extant today ( The notoungulates and litopterns had many strange forms, such as '' Macrauchenia'', a camel-like litoptern with a small

The notoungulates and litopterns had many strange forms, such as '' Macrauchenia'', a camel-like litoptern with a small

The invasions of South America started about 40 Ma ago (middle

The invasions of South America started about 40 Ma ago (middle

Cenozoic

The Cenozoic ( ; ) is Earth's current geological era, representing the last 66million years of Earth's history. It is characterised by the dominance of mammals, birds and flowering plants, a cooling and drying climate, and the current configu ...

paleozoogeographic biotic interchange event in which land and freshwater fauna

Fauna is all of the animal life present in a particular region or time. The corresponding term for plants is '' flora'', and for fungi, it is '' funga''. Flora, fauna, funga and other forms of life are collectively referred to as '' biota''. ...

migrated from North America via Central America to South America and vice versa, as the volcanic Isthmus of Panama

The Isthmus of Panama ( es, Istmo de Panamá), also historically known as the Isthmus of Darien (), is the narrow strip of land that lies between the Caribbean Sea and the Pacific Ocean, linking North and South America. It contains the country ...

rose up from the sea floor and bridged the formerly separated continent

A continent is any of several large landmasses. Generally identified by convention rather than any strict criteria, up to seven geographical regions are commonly regarded as continents. Ordered from largest in area to smallest, these seven ...

s. Although earlier dispersals had occurred, probably over water, the migration accelerated dramatically about 2.7 million years ( Ma) ago during the Piacenzian

The Piacenzian is in the international geologic time scale the upper stage or latest age of the Pliocene. It spans the time between 3.6 ± 0.005 Ma and 2.588 ± 0.005 Ma (million years ago). The Piacenzian is after the Zanclean and is followed ...

age. It resulted in the joining of the Neotropic

The Neotropical realm is one of the eight biogeographic realms constituting Earth's land surface. Physically, it includes the tropical terrestrial ecoregions of the Americas and the entire South American temperate zone.

Definition

In ...

(roughly South American) and Nearctic

The Nearctic realm is one of the eight biogeographic realms constituting the Earth's land surface.

The Nearctic realm covers most of North America, including Greenland, Central Florida, and the highlands of Mexico. The parts of North America ...

(roughly North American) biogeographic realm

A biogeographic realm or ecozone is the broadest biogeographic division of Earth's land surface, based on distributional patterns of terrestrial organisms. They are subdivided into bioregions, which are further subdivided into ecoregions. ...

s definitively to form the Americas

The Americas, which are sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North America, North and South America. The Americas make up most of the land in Earth's Western Hemisphere and comprise the New World. ...

. The interchange is visible from observation of both biostratigraphy

Biostratigraphy is the branch of stratigraphy which focuses on correlating and assigning relative ages of rock strata by using the fossil assemblages contained within them.Hine, Robert. “Biostratigraphy.” ''Oxford Reference: Dictionary of ...

and nature (neontology

Neontology is a part of biology that, in contrast to paleontology, deals with living (or, more generally, ''recent'') organisms. It is the study of extant taxa (singular: extant taxon): taxa (such as species, genera and families) with members st ...

). Its most dramatic effect is on the zoogeography

Zoogeography is the branch of the science of biogeography that is concerned with geographic distribution (present and past) of animal species.

As a multifaceted field of study, zoogeography incorporates methods of molecular biology, genetics, mor ...

of mammal

Mammals () are a group of vertebrate animals constituting the class Mammalia (), characterized by the presence of mammary glands which in females produce milk for feeding (nursing) their young, a neocortex (a region of the brain), fur ...

s, but it also gave an opportunity for reptile

Reptiles, as most commonly defined are the animals in the class Reptilia ( ), a paraphyletic grouping comprising all sauropsids except birds. Living reptiles comprise turtles, crocodilians, squamates ( lizards and snakes) and rhynchocephalia ...

s, amphibian

Amphibians are four-limbed and ectothermic vertebrates of the class Amphibia. All living amphibians belong to the group Lissamphibia. They inhabit a wide variety of habitats, with most species living within terrestrial, fossorial, arbo ...

s, arthropod

Arthropods (, (gen. ποδός)) are invertebrate animals with an exoskeleton, a segmented body, and paired jointed appendages. Arthropods form the phylum Arthropoda. They are distinguished by their jointed limbs and cuticle made of chiti ...

s, weak-flying or flightless bird

Flightless birds are birds that through evolution lost the ability to fly. There are over 60 extant species, including the well known ratites (ostriches, emu, cassowaries, rheas, and kiwi) and penguins. The smallest flightless bird is the ...

s, and even freshwater fish

Freshwater fish are those that spend some or all of their lives in fresh water, such as rivers and lakes, with a salinity of less than 1.05%. These environments differ from marine conditions in many ways, especially the difference in levels o ...

to migrate. Coastal and marine biota, however, was affected in the opposite manner; the formation of the Central American Isthmus caused what has been termed the Great American Schism, with significant diversification and extinction occurring as a result of the isolation of the Caribbean from the Pacific.

The occurrence of the interchange was first discussed in 1876 by the "father of biogeography

Biogeography is the study of the distribution of species and ecosystems in geographic space and through geological time. Organisms and biological communities often vary in a regular fashion along geographic gradients of latitude, elevation, ...

", Alfred Russel Wallace

Alfred Russel Wallace (8 January 1823 – 7 November 1913) was a British natural history, naturalist, explorer, geographer, anthropologist, biologist and illustrator. He is best known for independently conceiving the theory of evolution thro ...

. Wallace had spent five years exploring and collecting specimens in the Amazon basin

The Amazon basin is the part of South America drained by the Amazon River and its tributaries. The Amazon drainage basin covers an area of about , or about 35.5 percent of the South American continent. It is located in the countries of Boli ...

. Others who made significant contributions to understanding the event in the century that followed include Florentino Ameghino, W. D. Matthew, W. B. Scott, Bryan Patterson

Bryan Patterson (born 10 March 1909 in London; died 1 December 1979 in Chicago) was an American paleontologist at the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago.

Life and career

Bryan Patterson was the son of the soldier, engineer and aut ...

, George Gaylord Simpson

George Gaylord Simpson (June 16, 1902 – October 6, 1984) was an American paleontologist. Simpson was perhaps the most influential paleontologist of the twentieth century, and a major participant in the modern synthesis, contributing '' Tempo ...

and S. David Webb. The Pliocene timing of the formation of the connection between North and South America was discussed in 1910 by Henry Fairfield Osborn

Henry Fairfield Osborn, Sr. (August 8, 1857 – November 6, 1935) was an American paleontologist, geologist and eugenics advocate. He was the president of the American Museum of Natural History for 25 years and a cofounder of the American Euge ...

.

Analogous interchanges occurred earlier in the Cenozoic, when the formerly isolated land masses of India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area, the List of countries and dependencies by population, second-most populous ...

and Africa made contact with Eurasia

Eurasia (, ) is the largest continental area on Earth, comprising all of Europe and Asia. Primarily in the Northern and Eastern Hemispheres, it spans from the British Isles and the Iberian Peninsula in the west to the Japanese archipelag ...

about 56 and 30 Ma ago, respectively.

Before the interchange

Isolation of South America

After the late

After the late Mesozoic

The Mesozoic Era ( ), also called the Age of Reptiles, the Age of Conifers, and colloquially as the Age of the Dinosaurs is the second-to-last era of Earth's geological history, lasting from about , comprising the Triassic, Jurassic and Cretace ...

breakup of Gondwana

Gondwana () was a large landmass, often referred to as a supercontinent, that formed during the late Neoproterozoic (about 550 million years ago) and began to break up during the Jurassic period (about 180 million years ago). The final sta ...

, South America spent most of the Cenozoic era as an island continent whose "splendid isolation" allowed its fauna to evolve into many forms found nowhere else on Earth, most of which are now extinct

Extinction is the termination of a kind of organism or of a group of kinds (taxon), usually a species. The moment of extinction is generally considered to be the death of the last individual of the species, although the capacity to breed and ...

. Its endemic

Endemism is the state of a species being found in a single defined geographic location, such as an island, state, nation, country or other defined zone; organisms that are indigenous to a place are not endemic to it if they are also found else ...

mammals initially consisted primarily of metatheria

Metatheria is a mammalian clade that includes all mammals more closely related to marsupials than to placentals. First proposed by Thomas Henry Huxley in 1880, it is a more inclusive group than the marsupials; it contains all marsupials as w ...

ns (marsupial

Marsupials are any members of the mammalian infraclass Marsupialia. All extant marsupials are endemic to Australasia, Wallacea and the Americas. A distinctive characteristic common to most of these species is that the young are carried in ...

s and sparassodonts), xenarthra

Xenarthra (; from Ancient Greek ξένος, xénos, "foreign, alien" + ἄρθρον, árthron, "joint") is a major clade of placental mammals native to the Americas. There are 31 living species: the anteaters, tree sloths, and armadillos. ...

ns, and a diverse group of native ungulates

Ungulates ( ) are members of the diverse clade Ungulata which primarily consists of large mammals with hooves. These include odd-toed ungulates such as horses, rhinoceroses, and tapirs; and even-toed ungulates such as cattle, pigs, giraffes, ca ...

known as the Meridiungulata: notoungulates (the "southern ungulates"), litopterns, astrapotheres, pyrotheres and xenungulates. A few non-theria

Theria (; Greek: , wild beast) is a subclass of mammals amongst the Theriiformes. Theria includes the eutherians (including the placental mammals) and the metatherians (including the marsupials) but excludes the egg-laying monotremes.

...

n mammals – monotreme

Monotremes () are prototherian mammals of the order Monotremata. They are one of the three groups of living mammals, along with placentals ( Eutheria), and marsupials (Metatheria). Monotremes are typified by structural differences in their brai ...

s, gondwanatheres, dryolestids and possibly cimolodont

Cimolodonta is a taxon of extinct mammals that lived from the Cretaceous to the Eocene. They were some of the more derived members of the extinct order Multituberculata. They probably lived something of a rodent-like existence until their ecolo ...

multituberculates – were also present in the Paleocene

The Paleocene, ( ) or Palaeocene, is a geological epoch that lasted from about 66 to 56 million years ago (mya). It is the first epoch of the Paleogene Period in the modern Cenozoic Era. The name is a combination of the Ancient Greek ''pala ...

; while none of these diversified significantly and most lineages did not survive long, forms like '' Necrolestes'' and ''Patagonia

Patagonia () refers to a geographical region that encompasses the southern end of South America, governed by Argentina and Chile. The region comprises the southern section of the Andes Mountains with lakes, fjords, temperate rainforests, and g ...

'' remained as recently as the Miocene

The Miocene ( ) is the first geological epoch of the Neogene Period and extends from about (Ma). The Miocene was named by Scottish geologist Charles Lyell; the name comes from the Greek words (', "less") and (', "new") and means "less recen ...

.

Marsupials appear to have traveled via Gondwanan land connections from South America through Antarctica to Australia in the late

Marsupials appear to have traveled via Gondwanan land connections from South America through Antarctica to Australia in the late Cretaceous

The Cretaceous ( ) is a geological period that lasted from about 145 to 66 million years ago (Mya). It is the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era, as well as the longest. At around 79 million years, it is the longest geological period of ...

or early Tertiary

Tertiary ( ) is a widely used but obsolete term for the geologic period from 66 million to 2.6 million years ago.

The period began with the demise of the non-avian dinosaurs in the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event, at the start ...

. One living South American marsupial, the monito del monte

The monito del monte or colocolo opossum, ''Dromiciops gliroides'', also called ''chumaihuén'' in Mapudungun, is a diminutive marsupial native only to southwestern South America (Argentina and Chile). It is the only extant species in the ancient ...

, has been shown to be more closely related to Australian marsupials than to other South American marsupials ( Ameridelphia); however, it is the most basal australidelphian, meaning that this superorder arose in South America and then dispersed to Australia after the monito del monte split off. '' Monotrematum'', a 61-Ma-old platypus-like monotreme fossil from Patagonia

Patagonia () refers to a geographical region that encompasses the southern end of South America, governed by Argentina and Chile. The region comprises the southern section of the Andes Mountains with lakes, fjords, temperate rainforests, and g ...

, may represent an Australian immigrant. Paleognath birds (ratite

A ratite () is any of a diverse group of flightless, large, long-necked, and long-legged birds of the infraclass Palaeognathae. Kiwi, the exception, are much smaller and shorter-legged and are the only nocturnal extant ratites.

The systematics ...

s and South American tinamou

Tinamous () form an order of birds called Tinamiformes (), comprising a single family called Tinamidae (), divided into two distinct subfamilies, containing 46 species found in Mexico, Central America, and South America. The word "tinamou" co ...

s) may have made a similar migration around the same time to Australia and New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island coun ...

. Other taxa that may have dispersed by the same route (if not by flying or oceanic dispersal

Oceanic dispersal is a type of biological dispersal that occurs when terrestrial organisms transfer from one land mass to another by way of a sea crossing. Island hopping is the crossing of an ocean by a series of shorter journeys between isla ...

) are parrot

Parrots, also known as psittacines (), are birds of the roughly 398 species in 92 genera comprising the order Psittaciformes (), found mostly in tropical and subtropical regions. The order is subdivided into three superfamilies: the Psittacoide ...

s, chelid

Chelidae is one of three living families of the turtle suborder Pleurodira, and are commonly called Austro-South American side-neck turtles. The family is distributed in Australia, New Guinea, parts of Indonesia, and throughout most of South A ...

turtles, and the extinct meiolaniid turtles.

Marsupials remaining in South America included didelphimorphs (opossum

Opossums () are members of the marsupial order Didelphimorphia () endemic to the Americas. The largest order of marsupials in the Western Hemisphere, it comprises 93 species in 18 genera. Opossums originated in South America and entered No ...

s), paucituberculatans ( shrew opossums) and microbiotheres (monitos del monte). Larger predatory relatives of these also existed, such as the borhyaenids and the saber-toothed ''Thylacosmilus

''Thylacosmilus'' is an extinct genus of saber-toothed metatherian mammals that inhabited South America from the Late Miocene to Pliocene epochs. Though ''Thylacosmilus'' looks similar to the " saber-toothed cats", it was not a felid, like the ...

''; these were sparassodont metatherians, which are no longer considered to be true marsupials. As the large carnivorous metatherians declined, and before the arrival of most types of carnivora

Carnivora is a Clade, monophyletic order of Placentalia, placental mammals consisting of the most recent common ancestor of all felidae, cat-like and canidae, dog-like animals, and all descendants of that ancestor. Members of this group are f ...

ns, predatory opossums such as ''Thylophorops

''Thylophorops'' is an extinct genus of didelphine opossums from the Pliocene of South America. Compared to their close didelphine cousins like the living '' Philander'' and ''Didelphis'' (and like the still living '' Lutreolina'') opossums, '' ...

'' temporarily attained larger size (about 7 kg).

Metatherians and a few xenarthran armadillos, such as ''Macroeuphractus

''Macroeuphractus'' is a genus of extinct armadillos from the Late Miocene to Late Pliocene of South America. The genus is noted for its large size, with ''Macroeuphractus outesi'' being the largest non- pampathere or glyptodont armadillo discov ...

'', were the only South American mammals to specialize as carnivore

A carnivore , or meat-eater (Latin, ''caro'', genitive ''carnis'', meaning meat or "flesh" and ''vorare'' meaning "to devour"), is an animal or plant whose food and energy requirements derive from animal tissues (mainly muscle, fat and other s ...

s; their relative inefficiency created openings for nonmammalian predators to play more prominent roles than usual (similar to the situation in Australia). Sparassodonts and giant opossums shared the ecological niche

In ecology, a niche is the match of a species to a specific environmental condition.

Three variants of ecological niche are described by

It describes how an organism or population responds to the distribution of resources and competitors (for ...

s for large predators with fearsome flightless "terror birds" ( phorusrhacids), whose closest living relatives are the seriemas. North America also had large terrestrial predatory birds during the early Cenozoic (the related bathornithids), but they died out before the GABI in the Early Miocene

The Early Miocene (also known as Lower Miocene) is a sub-epoch of the Miocene epoch (geology), Epoch made up of two faunal stage, stages: the Aquitanian age, Aquitanian and Burdigalian stages.

The sub-epoch lasted from 23.03 ± 0.05 annum, Ma to ...

, about 20 million years ago. Through the skies over late Miocene South America (6 Ma ago) soared one of the largest flying birds known, ''Argentavis'', a teratorn

Teratornithidae is an extinct family of very large birds of prey that lived in North and South America from the Late Oligocene to the Late Pleistocene. They include some of the largest known flying birds.

Taxonomy

Teratornithidae are relate ...

that had a wing span of 6 m or more, and which may have subsisted in part on the leftovers of ''Thylacosmilus'' kills. Terrestrial sebecid

Sebecidae is an extinct family of prehistoric terrestrial sebecosuchian crocodylomorphs. The oldest known member of the group is ''Ogresuchus furatus'' known from the Upper Cretaceous (Maastrichtian) Tremp Formation (Spain). Sebecids were divers ...

( metasuchian) crocodyliform

Crocodyliformes is a clade of crurotarsan archosaurs, the group often traditionally referred to as "crocodilians". They are the first members of Crocodylomorpha to possess many of the features that define later relatives. They are the only pseu ...

s with ziphodont teeth were also present at least through the middle Miocene and maybe to the Miocene-Pliocene boundary. Some of South America's aquatic crocodilians, such as ''Gryposuchus

''Gryposuchus'' is an extinct genus of gavialid crocodilian. Fossils have been found from Argentina, Colombia, Venezuela, Brazil and the Peruvian Amazon. The genus existed during the Miocene epoch (Colhuehuapian to Huayquerian). One recently des ...

'', '' Mourasuchus'' and '' Purussaurus'', reached monstrous sizes, with lengths up to 12 m (comparable to the largest Mesozoic crocodyliforms). They shared their habitat with one of the largest turtles of all time, the 3.3 m (11 ft) '' Stupendemys''.

armadillo

Armadillos (meaning "little armored ones" in Spanish) are New World placental mammals in the order Cingulata. The Chlamyphoridae and Dasypodidae are the only surviving families in the order, which is part of the superorder Xenarthra, alo ...

s, anteater

Anteater is a common name for the four extant mammal species of the suborder Vermilingua (meaning "worm tongue") commonly known for eating ants and termites. The individual species have other names in English and other languages. Together wit ...

s, and tree sloth

Sloths are a group of Neotropical xenarthran mammals constituting the suborder Folivora, including the extant arboreal tree sloths and extinct terrestrial ground sloths. Noted for their slowness of movement, tree sloths spend most of their l ...

s), a great diversity of larger types was present, including pampatheres, the ankylosaur

Ankylosauria is a group of herbivorous dinosaurs of the order Ornithischia. It includes the great majority of dinosaurs with armor in the form of bony osteoderms, similar to turtles. Ankylosaurs were bulky quadrupeds, with short, powerful limbs. ...

-like glyptodont

Glyptodonts are an extinct subfamily of large, heavily armoured armadillos. They arose in South America around 48 million years ago and spread to southern North America after the continents became connected several million years ago. The best-k ...

s, predatory euphractine

Euphractinae is an armadillo subfamily in the family Chlamyphoridae.

Euphractinae are known for having a well developed osteoderm that has large cavities filled with adipose tissue, and more hair follicles with well developed sebaceous glands i ...

s, various ground sloth

Ground sloths are a diverse group of extinct sloths in the mammalian superorder Xenarthra. The term is used to refer to all extinct sloths because of the large size of the earliest forms discovered, compared to existing tree sloths. The Caribb ...

s, some of which reached the size of elephants (e.g. '' Megatherium''), and even semiaquatic to aquatic marine sloths.

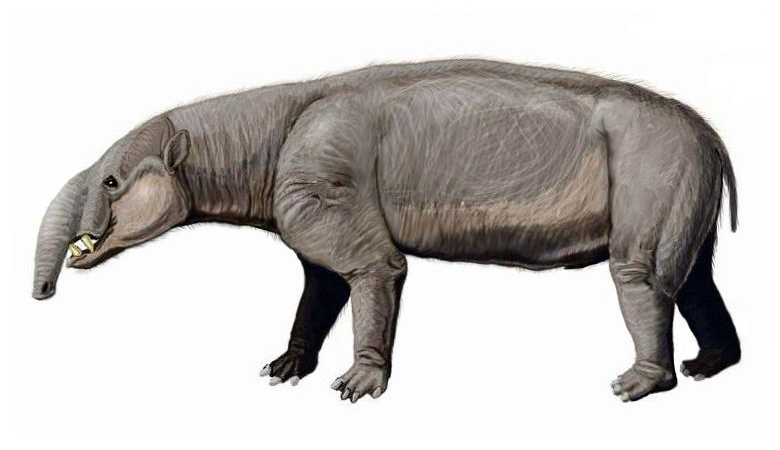

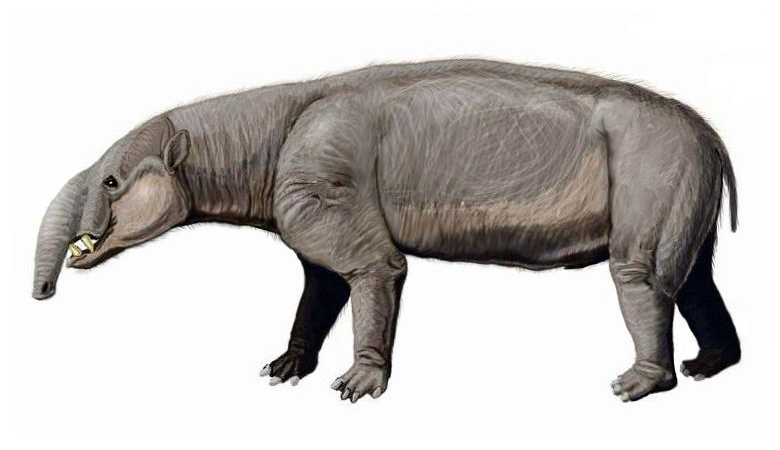

The notoungulates and litopterns had many strange forms, such as '' Macrauchenia'', a camel-like litoptern with a small

The notoungulates and litopterns had many strange forms, such as '' Macrauchenia'', a camel-like litoptern with a small proboscis

A proboscis () is an elongated appendage from the head of an animal, either a vertebrate or an invertebrate. In invertebrates, the term usually refers to tubular mouthparts used for feeding and sucking. In vertebrates, a proboscis is an elong ...

. They also produced a number of familiar-looking body types that represent examples of parallel

Parallel is a geometric term of location which may refer to:

Computing

* Parallel algorithm

* Parallel computing

* Parallel metaheuristic

* Parallel (software), a UNIX utility for running programs in parallel

* Parallel Sysplex, a cluster o ...

or convergent evolution

Convergent evolution is the independent evolution of similar features in species of different periods or epochs in time. Convergent evolution creates analogous structures that have similar form or function but were not present in the last com ...

: one-toed '' Thoatherium'' had legs like those of a horse, '' Pachyrukhos'' resembled a rabbit, '' Homalodotherium'' was a semibipedal, clawed browser like a chalicothere

Chalicotheres (from Greek '' chalix'', "gravel" and '' therion'', "beast") are an extinct clade of herbivorous, odd-toed ungulate (perissodactyl) mammals that lived in North America, Eurasia, and Africa from the Middle Eocene until the Early Ple ...

, and horned '' Trigodon'' looked like a rhinoceros

A rhinoceros (; ; ), commonly abbreviated to rhino, is a member of any of the five extant species (or numerous extinct species) of odd-toed ungulates in the family Rhinocerotidae. (It can also refer to a member of any of the extinct specie ...

. Both groups started evolving in the Lower Paleocene, possibly from condylarth stock, diversified, dwindled before the great interchange, and went extinct at the end of the Pleistocene. The pyrotheres and astrapotheres were also strange, but were less diverse and disappeared earlier, well before the interchange.

The North American fauna was a typical boreoeutheria

Boreoeutheria (, "northern true beasts") is a magnorder of placental mammals that groups together superorders Euarchontoglires and Laurasiatheria. With a few exceptionsExceptional clades whose males lack the usual boreoeutherian scrotum are mo ...

n one, supplemented with Afrotheria

Afrotheria ( from Latin ''Afro-'' "of Africa" + ''theria'' "wild beast") is a clade of mammals, the living members of which belong to groups that are either currently living in Africa or of African origin: golden moles, elephant shrews (also k ...

n proboscids.

Pre-interchange oceanic dispersals

The invasions of South America started about 40 Ma ago (middle

The invasions of South America started about 40 Ma ago (middle Eocene

The Eocene ( ) Epoch is a geological epoch that lasted from about 56 to 33.9 million years ago (mya). It is the second epoch of the Paleogene Period in the modern Cenozoic Era. The name ''Eocene'' comes from the Ancient Greek (''ēṓs'', ...

), when caviomorph

Caviomorpha is the rodent infraorder or parvorder that unites all New World hystricognaths. It is supported by both fossil and molecular evidence. The Caviomorpha was for a time considered to be a separate order outside the Rodentia, but is ...

rodents arrived in South America. Their subsequent vigorous diversification displaced some of South America's small marsupials and gave rise to – among others – capybara

The capybaraAlso called capivara (in Brazil), capiguara (in Bolivia), chigüire, chigüiro, or fercho (in Colombia and Venezuela), carpincho (in Argentina, Paraguay and Uruguay) and ronsoco (in Peru). or greater capybara (''Hydrochoerus hydro ...

s, chinchilla

Chinchillas are either of two species (''Chinchilla chinchilla'' and ''Chinchilla lanigera'') of crepuscular rodents of the parvorder Caviomorpha. They are slightly larger and more robust than ground squirrels, and are native to the Andes mounta ...

s, viscachas, and New World porcupines. The independent development of spines by New and Old World porcupines is another example of parallel evolution. This invasion most likely came from Africa. The crossing from West Africa to the northeast corner of Brazil was much shorter then, due to continental drift

Continental drift is the hypothesis that the Earth's continents have moved over geologic time relative to each other, thus appearing to have "drifted" across the ocean bed. The idea of continental drift has been subsumed into the science of pl ...

, and may have been aided by island hopping (e.g. via St. Paul's Rocks, if they were an inhabitable island at the time) and westward oceanic currents. Crossings of the ocean were accomplished when at least one fertilised female (more commonly a group of animals) accidentally floated over on driftwood

__NOTOC__

Driftwood is wood that has been washed onto a shore or beach of a sea, lake, or river by the action of winds, tides or waves.

In some waterfront areas, driftwood is a major nuisance. However, the driftwood provides shelter and fo ...

or mangrove

A mangrove is a shrub or tree that grows in coastal saline or brackish water. The term is also used for tropical coastal vegetation consisting of such species. Mangroves are taxonomically diverse, as a result of convergent evolution in severa ...

rafts. Hutias (Capromyidae) would subsequently colonize the West Indies

The West Indies is a subregion of North America, surrounded by the North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea that includes 13 independent island countries and 18 dependencies and other territories in three major archipelagos: the Greate ...

as far as the Bahamas

The Bahamas (), officially the Commonwealth of The Bahamas, is an island country within the Lucayan Archipelago of the West Indies in the North Atlantic. It takes up 97% of the Lucayan Archipelago's land area and is home to 88% of the a ...

, reaching the Greater Antilles by the early Oligocene. Over time, some caviomorph rodents evolved into larger forms that competed with some of the native South American ungulates, which may have contributed to the gradual loss of diversity suffered by the latter after the early Oligocene. By the Pliocene, some caviomorphs (e.g., ''Josephoartigasia monesi

''Josephoartigasia'' is an extinct genus of enormous dinomyid rodent from the Early Pliocene to Early Pleistocene of Uruguay. The only living member of Dinomyidae is the pacarana. ''Josephoartigasia'' is named after Uruguayan national hero Jos ...

'') attained sizes on the order of or larger.

*

Later (by 36 Ma ago), primate

Primates are a diverse order of mammals. They are divided into the strepsirrhines, which include the lemurs, galagos, and lorisids, and the haplorhines, which include the tarsiers and the simians ( monkeys and apes, the latter includin ...

s followed, again from Africa in a fashion similar to that of the rodents. Primates capable of migrating had to be small. Like caviomorph rodents, South American monkeys are believed to be a clade

A clade (), also known as a monophyletic group or natural group, is a group of organisms that are monophyletic – that is, composed of a common ancestor and all its lineal descendants – on a phylogenetic tree. Rather than the English ter ...

(i.e., monophyletic

In cladistics for a group of organisms, monophyly is the condition of being a clade—that is, a group of taxa composed only of a common ancestor (or more precisely an ancestral population) and all of its lineal descendants. Monophyletic gr ...

). However, although they would have had little effective competition, all extant New World monkey

New World monkeys are the five families of primates that are found in the tropical regions of Mexico, Central and South America: Callitrichidae, Cebidae, Aotidae, Pitheciidae, and Atelidae. The five families are ranked together as the Ceboidea ...

s appear to derive from a radiation that occurred long afterwards, in the Early Miocene

The Early Miocene (also known as Lower Miocene) is a sub-epoch of the Miocene epoch (geology), Epoch made up of two faunal stage, stages: the Aquitanian age, Aquitanian and Burdigalian stages.

The sub-epoch lasted from 23.03 ± 0.05 annum, Ma to ...

about 18 Ma ago. Subsequent to this, monkeys apparently most closely related to titis island-hopped to Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribb ...

, Hispaniola

Hispaniola (, also ; es, La Española; Latin and french: Hispaniola; ht, Ispayola; tnq, Ayiti or Quisqueya) is an island in the Caribbean that is part of the Greater Antilles. Hispaniola is the most populous island in the West Indies, and th ...

, and Jamaica

Jamaica (; ) is an island country situated in the Caribbean Sea. Spanning in area, it is the third-largest island of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean (after Cuba and Hispaniola). Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, and west of Hispa ...

. Additionally, a find of seven 21-Ma-old apparent cebid teeth in Panama suggests that South American monkeys had dispersed across the seaway separating Central and South America by that early date. However, all extant Central American monkeys are believed to be descended from much later migrants, and there is as yet no evidence that these early Central American cebids established an extensive or long-lasting population, perhaps due to a shortage of suitable rainforest habitat at the time.

Fossil evidence presented in 2020 indicates a second lineage of African monkeys also rafted to and at least briefly colonized South America. '' Ucayalipithecus'' remains dating from the Early Oligocene of Amazonian Peru are, by morphological analysis, deeply nested within the family Parapithecidae of the Afro-Arabian radiation of parapithecoid simian

The simians, anthropoids, or higher primates are an infraorder (Simiiformes ) of primates containing all animals traditionally called monkeys and apes. More precisely, they consist of the parvorders New World monkeys (Platyrrhini) and Cat ...

s, with dental features markedly different from those of platyrrhines. The Old World members of this group are thought to have become extinct by the Late Oligocene. '' Qatrania wingi'' of lower Oligocene Fayum deposits is considered the closest known relative of ''Ucayalipithecus''.

Remarkably, the descendants of those few bedraggled "waif

A waif (from the Old French ''guaif'', "stray beast")Dictionary.com Unabridged (v 1.1). Random House, Inc. http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/waif (accessed: June 02, 2008) is a person removed, by hardship, loss or other helpless circumstance ...

s" that crawled ashore from their rafts of African flotsam in the Eocene now constitute more than twice as many of South America's species as the descendants of all the flightless mammals previously resident on the continent ( 372 caviomorph and monkey species versus 136 marsupial and xenarthran species).

Many of South America's bats may have arrived from Africa during roughly the same period, possibly with the aid of intervening islands, although by flying rather than floating. Noctilionoid bats ancestral to those in the neotropical families Furipteridae

Furipteridae is family of bats, allying two genera of single species, '' Amorphochilus schnablii'' (smoky bat) and the type '' Furipterus horrens'' (thumbless bat). They are found in Central and South America and are closely related to the bats ...

, Mormoopidae

The family Mormoopidae contains bats known generally as mustached bats, ghost-faced bats, and naked-backed bats. They are found in the Americas from the Southwestern United States to Southeastern Brazil.

They are distinguished by the presenc ...

, Noctilionidae, Phyllostomidae, and Thyropteridae are thought to have reached South America from Africa in the Eocene, possibly via Antarctica. Similarly, free-tailed bat

The Molossidae, or free-tailed bats, are a family of bats within the order Chiroptera.

The Molossidae is the fourth-largest family of bats, containing about 110 species as of 2012. They are generally quite robust, and consist of many strong-flyi ...

s (Molossidae) may have reached South America from Africa in as many as five dispersals, starting in the Eocene. Emballonurids may have also reached South America from Africa about 30 Ma ago, based on molecular evidence. Vespertilionids may have arrived in five dispersals from North America and one from Africa. Natalids are thought to have arrived during the Pliocene

The Pliocene ( ; also Pleiocene) is the epoch in the geologic time scale that extends from 5.333 million to 2.58

Tortoises also arrived in South America in the Oligocene. They were long thought to have come from North America, but a recent comparative genetic analysis concludes that the South American genus '' Chelonoidis'' (formerly part of ''

Tortoises also arrived in South America in the Oligocene. They were long thought to have come from North America, but a recent comparative genetic analysis concludes that the South American genus '' Chelonoidis'' (formerly part of '' The earliest traditionally recognized mammalian arrival from North America was a

The earliest traditionally recognized mammalian arrival from North America was a

In general, the initial net migration was symmetrical. Later on, however, the Neotropic species proved far less successful than the Nearctic. This difference in fortunes was manifested in several ways. Northwardly migrating animals often were not able to compete for resources as well as the North American species already occupying the same ecological niches; those that did become established were not able to diversify much, and in some cases did not survive for long. Southwardly migrating Nearctic species established themselves in larger numbers and diversified considerably more, and are thought to have caused the extinction of a large proportion of the South American fauna. (No extinctions in North America are plainly linked to South American immigrants.) Native South American ungulates did poorly, with only a handful of genera withstanding the northern onslaught. (Several of the largest forms, macraucheniids and toxodontids, have long been recognized to have survived to the end of the Pleistocene. Recent fossil finds indicate that one species of the horse-like proterotheriid litopterns did, as well. The notoungulate mesotheriids and hegetotheriids also managed to hold on at least part way through the Pleistocene.) South America's small marsupials, though, survived in large numbers, while the primitive-looking

In general, the initial net migration was symmetrical. Later on, however, the Neotropic species proved far less successful than the Nearctic. This difference in fortunes was manifested in several ways. Northwardly migrating animals often were not able to compete for resources as well as the North American species already occupying the same ecological niches; those that did become established were not able to diversify much, and in some cases did not survive for long. Southwardly migrating Nearctic species established themselves in larger numbers and diversified considerably more, and are thought to have caused the extinction of a large proportion of the South American fauna. (No extinctions in North America are plainly linked to South American immigrants.) Native South American ungulates did poorly, with only a handful of genera withstanding the northern onslaught. (Several of the largest forms, macraucheniids and toxodontids, have long been recognized to have survived to the end of the Pleistocene. Recent fossil finds indicate that one species of the horse-like proterotheriid litopterns did, as well. The notoungulate mesotheriids and hegetotheriids also managed to hold on at least part way through the Pleistocene.) South America's small marsupials, though, survived in large numbers, while the primitive-looking  Armadillos, opossums and porcupines are present in North America today because of the Great American Interchange. Opossums and porcupines were among the most successful northward migrants, reaching as far as Canada and

Armadillos, opossums and porcupines are present in North America today because of the Great American Interchange. Opossums and porcupines were among the most successful northward migrants, reaching as far as Canada and

During the last 7 Ma, South America's terrestrial predator

During the last 7 Ma, South America's terrestrial predator

The eventual triumph of the Nearctic migrants was ultimately based on geography, which played into the hands of the northern invaders in two crucial respects. The first was a matter of

The eventual triumph of the Nearctic migrants was ultimately based on geography, which played into the hands of the northern invaders in two crucial respects. The first was a matter of  The second and more important advantage geography gave to the northerners is related to the land area in which their ancestors evolved. During the Cenozoic, North America was periodically connected to Eurasia via

The second and more important advantage geography gave to the northerners is related to the land area in which their ancestors evolved. During the Cenozoic, North America was periodically connected to Eurasia via

At the end of the Pleistocene epoch, about 12,000 years ago, three dramatic developments occurred in the Americas at roughly the same time (geologically speaking). Paleoindians invaded and occupied the

At the end of the Pleistocene epoch, about 12,000 years ago, three dramatic developments occurred in the Americas at roughly the same time (geologically speaking). Paleoindians invaded and occupied the

The near-simultaneity of the megafaunal extinctions with the glacial retreat and the

The near-simultaneity of the megafaunal extinctions with the glacial retreat and the

File:Green-Treefrog-North-American-Gray-Species-5.JPG, Gray tree frog, ''Hyla versicolor''

File:Nine-banded Armadillo.jpg, Nine-banded armadillo, ''Dasypus novemcinctus''

File:Gyptodon Cosmo Caixa.JPG, The

File:Oophaga pumilio (Strawberry poision frog) (2532163201).jpg, Strawberry poison dart frog, poison-dart frog, ''Strawberry poison-dart frog, Oophaga pumilio''

File:Caiman crocodilus llanos.JPG, Spectacled caiman, ''Caiman crocodilus''

File:Choloepus hoffmanni (Puerto Viejo, CR) crop.jpg, The two-toed sloth ''Choloepus hoffmanni''

File:Dasyprocta punctata (8973160761).jpg, Central American agouti, ''Dasyprocta punctata''

File:Capuchin Costa Rica.jpg, White-headed capuchin, ''Cebus capucinus''

File:Great Tinamou.jpg, Great

Perusing Talara: Overview of the Late Pleistocene fossils from the tar seeps of Peru

. Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County Science Series, 42: 97-109 and the latter set of remains were initially identified as being from jaguars * Bats (Chiroptera) ** Natalidae, Natalid bats (''Chilonatalus micropus'', ''Natalus espiritosantensis'', ''Natalus tumidirostris, N. tumidirostris'') ** Vespertilionidae, Vespertilionid bats

File:Cobra-papagaio - Bothrops bilineatus - Ilhéus - Bahia.jpg, Amazonian palm viper, ''Bothrops bilineatus''

File:Drymoreomys albimaculatus 002.jpg, ''Drymoreomys albimaculatus'', a Sigmodontinae, sigmodontine rodent

File:Guanacos, Parque Nacional Torres del Paine, Chile3.jpg, The

Tortoises also arrived in South America in the Oligocene. They were long thought to have come from North America, but a recent comparative genetic analysis concludes that the South American genus '' Chelonoidis'' (formerly part of ''

Tortoises also arrived in South America in the Oligocene. They were long thought to have come from North America, but a recent comparative genetic analysis concludes that the South American genus '' Chelonoidis'' (formerly part of ''Geochelone

''Geochelone'' is a genus of tortoises.

''Geochelone'' tortoises, which are also known as typical tortoises or terrestrial turtles, can be found in southern Asia. They primarily eat plants. Species

The genus consists of two extant species:

A n ...

'') is actually most closely related to African hingeback tortoises. Tortoises are aided in oceanic dispersal by their ability to float with their heads up, and to survive up to six months without food or water. South American tortoises then went on to colonize the West Indies and Galápagos Islands (the Galápagos tortoise

The Galápagos tortoise or Galápagos giant tortoise (''Chelonoidis niger'') is a species of very large tortoise in the genus ''Chelonoidis'' (which also contains three smaller species from mainland South America). It comprises 15 subspecies ...

). A number of clades of American gecko

Geckos are small, mostly carnivorous lizards that have a wide distribution, found on every continent except Antarctica. Belonging to the infraorder Gekkota, geckos are found in warm climates throughout the world. They range from .

Geckos a ...

s seem to have rafted over from Africa during both the Paleogene and Neogene. Skinks of the related genera ''Mabuya

''Mabuya'' is a genus of long-tailed skinks restricted to species from various Caribbean islands. They are primarily carnivorous, though many are omnivorous. The genus is viviparous, having a highly evolved placenta that resembles that of eutheri ...

'' and ''Trachylepis

''Trachylepis'' is a skink genus in the subfamily Mabuyinae found mainly in Africa. Its members were formerly included in the " wastebin taxon" ''Mabuya'', and for some time in ''Euprepis''. As defined today, ''Trachylepis'' contains the clade ...

'' apparently dispersed across the Atlantic from Africa to South America and Fernando de Noronha

Fernando de Noronha () is an archipelago in the Atlantic Ocean, part of the State of Pernambuco, Brazil, and located off the Brazilian coast. It consists of 21 islands and islets, extending over an area of . Only the eponymous main island is in ...

, respectively, during the last 9 Ma. Surprisingly, South America's burrowing amphisbaenia

Amphisbaenia (called amphisbaenians or worm lizards) is a group of usually legless squamates, comprising over 200 extant species. Amphisbaenians are characterized by their long bodies, the reduction or loss of the limbs, and rudimentary eyes. As ...

ns and blind snake

The Scolecophidia, commonly known as blind snakes or thread snakes, are an infraorder of snakes. They range in length from . All are fossorial (adapted for burrowing). Five families and 39 genera are recognized. The Scolecophidia infraorder is mos ...

s also appear to have rafted from Africa, as does the hoatzin

The hoatzin ( ) or hoactzin ( ), (''Opisthocomus hoazin''), is the only species in the order Opisthocomiformes. It is a species of tropical bird found in swamps, riparian forests, and mangroves of the Amazon and the Orinoco basins in South Ameri ...

, a weak-flying bird of South American rainforests.

The earliest traditionally recognized mammalian arrival from North America was a

The earliest traditionally recognized mammalian arrival from North America was a procyonid

Procyonidae is a New World family of the order Carnivora. It comprises the raccoons, ringtails, cacomistles, coatis, kinkajous, olingos, and olinguitos. Procyonids inhabit a wide range of environments and are generally omnivorous.

Characteri ...

that island-hopped from Central America before the Isthmus of Panama land bridge

In biogeography, a land bridge is an isthmus or wider land connection between otherwise separate areas, over which animals and plants are able to cross and colonize new lands. A land bridge can be created by marine regression, in which sea leve ...

formed, around 7.3 Ma ago. This was South America's first eutheria

Eutheria (; from Greek , 'good, right' and , 'beast'; ) is the clade consisting of all therian mammals that are more closely related to placentals than to marsupials.

Eutherians are distinguished from noneutherians by various phenotypic tra ...

n carnivore. South American procyonids then diversified into forms now extinct (e.g. the "dog-coati" '' Cyonasua'', which evolved into the bear-like ''Chapalmalania

''Chapalmalania'' is an extinct genus of procyonid from the Pliocene (Chapadmalalan to Uquian) of Argentina and Colombia ( Ware Formation, Cocinetas Basin, La Guajira).

Description

Though related to raccoons and coatis, ''Chapalmalania'' w ...

''). However, all extant procyonid genera appear to have originated in North America. The first South American procyonids may have contributed to the extinction of sebecid crocodilians by eating their eggs, but this view has not been universally viewed as plausible. The procyonids were followed to South America by rafting or island-hopping hog-nosed skunks and sigmodontine rodents. The oryzomyine

Oryzomyini is a tribe of rodents in the subfamily Sigmodontinae of the family Cricetidae. It includes about 120 species in about thirty genera,Weksler et al., 2006, table 1 distributed from the eastern United States to the southernmost parts of ...

tribe of sigmodontine rodents went on to colonize

Colonization, or colonisation, constitutes large-scale population movements wherein migrants maintain strong links with their, or their ancestors', former country – by such links, gain advantage over other inhabitants of the territory. When ...

the Lesser Antilles

The Lesser Antilles ( es, link=no, Antillas Menores; french: link=no, Petites Antilles; pap, Antias Menor; nl, Kleine Antillen) are a group of islands in the Caribbean Sea. Most of them are part of a long, partially volcanic island arc be ...

to Anguilla

Anguilla ( ) is a British Overseas Territory in the Caribbean. It is one of the most northerly of the Leeward Islands in the Lesser Antilles, lying east of Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands and directly north of Saint Martin. The terr ...

.

One group has proposed that a number of large Neartic herbivores actually reached South America as early as 9–10 Ma ago, in the late Miocene, via an early incomplete land bridge. These claims, based on fossils recovered from rivers in southwestern Peru, have been viewed with caution by other investigators, due to the lack of corroborating finds from other sites and the fact that almost all of the specimens in question have been collected as float in rivers without little to no stratigraphic control. These taxa are a gomphothere

Gomphotheres are any members of the diverse, extinct taxonomic family Gomphotheriidae. Gomphotheres were elephant-like proboscideans, but do not belong to the family Elephantidae. They were widespread across Afro-Eurasia and North America dur ...

('' Amahuacatherium''), peccaries ('' Sylvochoerus'' and '' Waldochoerus''), tapir

Tapirs ( ) are large, herbivorous mammals belonging to the family Tapiridae. They are similar in shape to a pig, with a short, prehensile nose trunk. Tapirs inhabit jungle and forest regions of South and Central America, with one species inh ...

s and ''Surameryx

''Surameryx'' is an extinct genus of herbivorous even-toed ungulates originally described as belonging to the extinct family Palaeomerycidae. A single species, ''S. acrensis,'' was described from the Late Miocene (between the Mayoan and Huayqu ...

'', a palaeomerycid (from a family probably ancestral to cervids). The identification of ''Amahuacatherium'' and the dating of its site is controversial; it is regarded by a number of investigators as a misinterpreted fossil of a different gomphothere, ''Notiomastodon

''Notiomastodon'' is an extinct proboscidean genus of gomphotheres (a distant relative to modern elephants) endemic to South America from the Pleistocene to the beginning of the Holocene. ''Notiomastodon'' specimens reached a size similar to th ...

'', and biostratigraphy dates the site to the Pleistocene. The early date proposed for ''Surameryx'' has also been met with skepticism.

Megalonychid and mylodontid ground sloth

Ground sloths are a diverse group of extinct sloths in the mammalian superorder Xenarthra. The term is used to refer to all extinct sloths because of the large size of the earliest forms discovered, compared to existing tree sloths. The Caribb ...

s island-hopped to North America by 9 Ma ago. A basal group of sloths had colonized the Antilles

The Antilles (; gcf, label=Antillean Creole, Antiy; es, Antillas; french: Antilles; nl, Antillen; ht, Antiy; pap, Antias; Jamaican Patois: ''Antiliiz'') is an archipelago bordered by the Caribbean Sea to the south and west, the Gulf of Mex ...

previously, by the early Miocene

The Miocene ( ) is the first geological epoch of the Neogene Period and extends from about (Ma). The Miocene was named by Scottish geologist Charles Lyell; the name comes from the Greek words (', "less") and (', "new") and means "less recen ...

. In contrast, megatheriid and nothrotheriid ground sloths did not migrate north until the formation of the isthmus. Terror birds may have also island-hopped to North America as early as 5 Ma ago.

The Caribbean Islands were populated primarily by species from South America, due to the prevailing direction of oceanic currents, rather than to a competition between North and South American forms. Except in the case of Jamaica, oryzomyine rodents of North American origin were able to enter the region only after invading South America.

Effects and aftermath

The formation of the Isthmus of Panama led to the last and most conspicuous wave, the Great American Biotic Interchange (GABI), starting around 2.7 Ma ago. This included the immigration into South America of North Americanungulates

Ungulates ( ) are members of the diverse clade Ungulata which primarily consists of large mammals with hooves. These include odd-toed ungulates such as horses, rhinoceroses, and tapirs; and even-toed ungulates such as cattle, pigs, giraffes, ca ...

(including camelid

Camelids are members of the biological family Camelidae, the only currently living family in the suborder Tylopoda. The seven extant members of this group are: dromedary camels, Bactrian camels, wild Bactrian camels, llamas, alpacas, vicuñas, ...

s, tapir

Tapirs ( ) are large, herbivorous mammals belonging to the family Tapiridae. They are similar in shape to a pig, with a short, prehensile nose trunk. Tapirs inhabit jungle and forest regions of South and Central America, with one species inh ...

s, deer

Deer or true deer are hoofed ruminant mammals forming the family Cervidae. The two main groups of deer are the Cervinae, including the muntjac, the elk (wapiti), the red deer, and the fallow deer; and the Capreolinae, including the re ...

and horse

The horse (''Equus ferus caballus'') is a domesticated, one-toed, hoofed mammal. It belongs to the taxonomic family Equidae and is one of two extant subspecies of ''Equus ferus''. The horse has evolved over the past 45 to 55 million yea ...

s), proboscids (gomphothere

Gomphotheres are any members of the diverse, extinct taxonomic family Gomphotheriidae. Gomphotheres were elephant-like proboscideans, but do not belong to the family Elephantidae. They were widespread across Afro-Eurasia and North America dur ...

s), carnivora

Carnivora is a Clade, monophyletic order of Placentalia, placental mammals consisting of the most recent common ancestor of all felidae, cat-like and canidae, dog-like animals, and all descendants of that ancestor. Members of this group are f ...

ns (including felid

Felidae () is the family of mammals in the order Carnivora colloquially referred to as cats, and constitutes a clade. A member of this family is also called a felid (). The term "cat" refers both to felids in general and specifically to the dom ...

s such as cougar

The cougar (''Puma concolor'') is a large cat native to the Americas. Its range spans from the Canadian Yukon to the southern Andes in South America and is the most widespread of any large wild terrestrial mammal in the Western Hemisphere. ...

s, jaguar

The jaguar (''Panthera onca'') is a large cat species and the only living member of the genus ''Panthera'' native to the Americas. With a body length of up to and a weight of up to , it is the largest cat species in the Americas and the th ...

s and saber-toothed cats, canid

Canidae (; from Latin, '' canis'', " dog") is a biological family of dog-like carnivorans, colloquially referred to as dogs, and constitutes a clade. A member of this family is also called a canid (). There are three subfamilies found withi ...

s, mustelids, procyonids

Procyonidae is a New World family of the order Carnivora. It comprises the raccoons, ringtails, cacomistles, coatis, kinkajous, olingos, and olinguitos. Procyonids inhabit a wide range of environments and are generally omnivorous.

Characteri ...

and bear

Bears are carnivoran mammals of the family Ursidae. They are classified as caniforms, or doglike carnivorans. Although only eight species of bears are extant, they are widespread, appearing in a wide variety of habitats throughout the No ...

s) and a number of types of rodent

Rodents (from Latin , 'to gnaw') are mammals of the order Rodentia (), which are characterized by a single pair of continuously growing incisors in each of the upper and lower jaws. About 40% of all mammal species are rodents. They are n ...

s. The larger members of the reverse migration, besides ground sloths and terror birds, were glyptodont

Glyptodonts are an extinct subfamily of large, heavily armoured armadillos. They arose in South America around 48 million years ago and spread to southern North America after the continents became connected several million years ago. The best-k ...

s, pampathere

Pampatheriidae (" Pampas beasts") is an extinct family of large plantigrade armored armadillos related to extant armadillos in the order Cingulata. However, pampatheriids have existed as a separate lineage since at least the middle Eocene Muster ...

s, capybaras, and the notoungulate ''Mixotoxodon

''Mixotoxodon'' ("mixture ''Toxodon''") is an extinct genus of notoungulate of the family Toxodontidae inhabiting South America, Central America and parts of southern North America during the Pleistocene epoch, from 1,800,000—12,000 years a ...

'' (the only South American ungulate known to have invaded Central America).

In general, the initial net migration was symmetrical. Later on, however, the Neotropic species proved far less successful than the Nearctic. This difference in fortunes was manifested in several ways. Northwardly migrating animals often were not able to compete for resources as well as the North American species already occupying the same ecological niches; those that did become established were not able to diversify much, and in some cases did not survive for long. Southwardly migrating Nearctic species established themselves in larger numbers and diversified considerably more, and are thought to have caused the extinction of a large proportion of the South American fauna. (No extinctions in North America are plainly linked to South American immigrants.) Native South American ungulates did poorly, with only a handful of genera withstanding the northern onslaught. (Several of the largest forms, macraucheniids and toxodontids, have long been recognized to have survived to the end of the Pleistocene. Recent fossil finds indicate that one species of the horse-like proterotheriid litopterns did, as well. The notoungulate mesotheriids and hegetotheriids also managed to hold on at least part way through the Pleistocene.) South America's small marsupials, though, survived in large numbers, while the primitive-looking

In general, the initial net migration was symmetrical. Later on, however, the Neotropic species proved far less successful than the Nearctic. This difference in fortunes was manifested in several ways. Northwardly migrating animals often were not able to compete for resources as well as the North American species already occupying the same ecological niches; those that did become established were not able to diversify much, and in some cases did not survive for long. Southwardly migrating Nearctic species established themselves in larger numbers and diversified considerably more, and are thought to have caused the extinction of a large proportion of the South American fauna. (No extinctions in North America are plainly linked to South American immigrants.) Native South American ungulates did poorly, with only a handful of genera withstanding the northern onslaught. (Several of the largest forms, macraucheniids and toxodontids, have long been recognized to have survived to the end of the Pleistocene. Recent fossil finds indicate that one species of the horse-like proterotheriid litopterns did, as well. The notoungulate mesotheriids and hegetotheriids also managed to hold on at least part way through the Pleistocene.) South America's small marsupials, though, survived in large numbers, while the primitive-looking xenarthra

Xenarthra (; from Ancient Greek ξένος, xénos, "foreign, alien" + ἄρθρον, árthron, "joint") is a major clade of placental mammals native to the Americas. There are 31 living species: the anteaters, tree sloths, and armadillos. ...

ns proved to be surprisingly competitive and became the most successful invaders of North America. The African immigrants, the caviomorph rodents and platyrrhine monkeys, were less impacted by the interchange than most of South America's 'old-timers', although the caviomorphs suffered a significant loss of diversity, including the elimination of the largest forms (e.g. the dinomyids). With the exception of the North American porcupine

The North American porcupine (''Erethizon dorsatum''), also known as the Canadian porcupine, is a large quill-covered rodent in the New World porcupine family. It is the second largest rodent in North America, after the North American beaver ('' ...

and several extinct porcupines and capybaras, however, they did not migrate past Central America.

Due in large part to the continued success of the xenarthrans, one area of South American ecospace

Ecology () is the study of the relationships between living organisms, including humans, and their physical environment. Ecology considers organisms at the individual, population, community, ecosystem, and biosphere level. Ecology overl ...

the Nearctic invaders were unable to dominate was the niches for megaherbivores. Before 12,000 years ago, South America was home to about 25 species of herbivores weighing more than 1000 kg, consisting of Neotropic ground sloths, glyptodonts, and toxodontids, as well as gomphotheres and camelids of Nearctic origin. Native South American forms made up about 75% of these species. However, none of these megaherbivores has survived.

Armadillos, opossums and porcupines are present in North America today because of the Great American Interchange. Opossums and porcupines were among the most successful northward migrants, reaching as far as Canada and

Armadillos, opossums and porcupines are present in North America today because of the Great American Interchange. Opossums and porcupines were among the most successful northward migrants, reaching as far as Canada and Alaska

Alaska ( ; russian: Аляска, Alyaska; ale, Alax̂sxax̂; ; ems, Alas'kaaq; Yup'ik: ''Alaskaq''; tli, Anáaski) is a state located in the Western United States on the northwest extremity of North America. A semi-exclave of the U ...

, respectively. Most major groups of xenarthrans were present in North America until the end-Pleistocene Quaternary extinction event

The Quaternary period (from 2.588 ± 0.005 million years ago to the present) has seen the extinctions of numerous predominantly megafaunal species, which have resulted in a collapse in faunal density and diversity and the extinction of key ecolog ...

(as a result of at least eight successful invasions of temperate North America, and at least six more invasions of Central America only). Among the megafauna

In terrestrial zoology, the megafauna (from Greek μέγας ''megas'' "large" and New Latin ''fauna'' "animal life") comprises the large or giant animals of an area, habitat, or geological period, extinct and/or extant. The most common thresho ...

, ground sloths were notably successful emigrants; four different lineages invaded North America. A megalonychid representative, ''Megalonyx

''Megalonyx'' ( Greek, "large claw") is an extinct genus of ground sloths of the family Megalonychidae, native to North America during the Pliocene and Pleistocene epochs. It became extinct during the Quaternary extinction event at the end ...

'', spread as far north as the Yukon

Yukon (; ; formerly called Yukon Territory and also referred to as the Yukon) is the smallest and westernmost of Canada's three territories. It also is the second-least populated province or territory in Canada, with a population of 43,964 as ...

and Alaska, and might well have invaded Eurasia had a suitable habitat corridor across Beringia been present.

Generally speaking, however, the dispersal and subsequent explosive adaptive radiation

In evolutionary biology, adaptive radiation is a process in which organisms diversify rapidly from an ancestral species into a multitude of new forms, particularly when a change in the environment makes new resources available, alters biotic in ...

of sigmodontine rodents throughout South America (leading to over 80 currently recognized genera) was vastly more successful (both spatially and by number of species) than any northward migration of South American mammals. Other examples of North American mammal groups that diversified conspicuously in South America include canids and cervids, both of which currently have three or four genera in North America, two or three in Central America, and six in South America. Although members of ''Canis

''Canis'' is a genus of the Caninae which includes multiple extant species, such as wolves, dogs, coyotes, and golden jackals. Species of this genus are distinguished by their moderate to large size, their massive, well-developed skulls and de ...

'' (specifically, coyote

The coyote (''Canis latrans'') is a species of canine native to North America. It is smaller than its close relative, the wolf, and slightly smaller than the closely related eastern wolf and red wolf. It fills much of the same ecological nich ...

s) currently range only as far south as Panama, South America still has more extant genera of canids than any other continent.

The effect of formation of the isthmus on the marine biota of the area was the inverse of its effect on terrestrial organisms, a development that has been termed the "Great American Schism". The connection between the east Pacific Ocean and the Caribbean (the Central American Seaway

The Central American Seaway (also known as the Panamanic Seaway, Inter-American Seaway and Proto-Caribbean Seaway) was a body of water that once separated North America from South America. It formed during the Jurassic (200–154 Ma) during the ...

) was severed, setting now-separated populations on divergent evolutionary paths. Caribbean species also had to adapt to an environment of lower productivity after the inflow of nutrient-rich water of deep Pacific origin was blocked. The Pacific coast of South America cooled as the input of warm water from the Caribbean was cut off. This trend is thought to have caused the extinction of the marine sloths of the area.

Disappearance of native South American predators

During the last 7 Ma, South America's terrestrial predator

During the last 7 Ma, South America's terrestrial predator guild

A guild ( ) is an association of artisans and merchants who oversee the practice of their craft/trade in a particular area. The earliest types of guild formed as organizations of tradesmen belonging to a professional association. They sometim ...

has changed from one composed almost entirely of nonplacental mammals ( metatherians), birds

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the laying of hard-shelled eggs, a high metabolic rate, a four-chambered heart, and a strong yet lightweigh ...

, and reptiles to one dominated by immigrant placental

Placental mammals (infraclass Placentalia ) are one of the three extant subdivisions of the class Mammalia, the other two being Monotremata and Marsupialia. Placentalia contains the vast majority of extant mammals, which are partly distinguishe ...

carnivorans (with a few small marsupial and avian predators like didelphine opossums

Opossums () are members of the marsupial order Didelphimorphia () endemic to the Americas. The largest order of marsupials in the Western Hemisphere, it comprises 93 species in 18 genera. Opossums originated in South America and entered North A ...

and seriemas

The seriemas are the sole living members of the small bird family Cariamidae, which is also the only surviving lineage of the order Cariamiformes. Once believed to be related to cranes, they have been placed near the falcons, parrots and pass ...

). It was originally thought that the native South American predator

Predation is a biological interaction where one organism, the predator, kills and eats another organism, its prey. It is one of a family of common feeding behaviours that includes parasitism and micropredation (which usually do not kill t ...

guild

A guild ( ) is an association of artisans and merchants who oversee the practice of their craft/trade in a particular area. The earliest types of guild formed as organizations of tradesmen belonging to a professional association. They sometim ...

, including sparassodonts, carnivorous

A carnivore , or meat-eater (Latin, ''caro'', genitive ''carnis'', meaning meat or "flesh" and ''vorare'' meaning "to devour"), is an animal or plant whose food and energy requirements derive from animal tissues (mainly muscle, fat and other ...

opossum

Opossums () are members of the marsupial order Didelphimorphia () endemic to the Americas. The largest order of marsupials in the Western Hemisphere, it comprises 93 species in 18 genera. Opossums originated in South America and entered No ...

s like ''Thylophorops

''Thylophorops'' is an extinct genus of didelphine opossums from the Pliocene of South America. Compared to their close didelphine cousins like the living '' Philander'' and ''Didelphis'' (and like the still living '' Lutreolina'') opossums, '' ...

'' and '' Hyperdidelphys'', armadillo

Armadillos (meaning "little armored ones" in Spanish) are New World placental mammals in the order Cingulata. The Chlamyphoridae and Dasypodidae are the only surviving families in the order, which is part of the superorder Xenarthra, alo ...

s such as ''Macroeuphractus

''Macroeuphractus'' is a genus of extinct armadillos from the Late Miocene to Late Pliocene of South America. The genus is noted for its large size, with ''Macroeuphractus outesi'' being the largest non- pampathere or glyptodont armadillo discov ...

'', terror birds, and teratorns

Teratornithidae is an extinct family of very large birds of prey that lived in North and South America from the Late Oligocene to the Late Pleistocene. They include some of the largest known flying birds.

Taxonomy

Teratornithidae are related t ...

, as well as early-arriving immigrant '' Cyonasua''-group procyonids

Procyonidae is a New World family of the order Carnivora. It comprises the raccoons, ringtails, cacomistles, coatis, kinkajous, olingos, and olinguitos. Procyonids inhabit a wide range of environments and are generally omnivorous.

Characteri ...

, were driven to extinction during the GABI by competitive exclusion from immigrating placental carnivorans, and that this turnover was abrupt. However, the turnover of South America's predator guild was more complex, with competition

Competition is a rivalry where two or more parties strive for a common goal which cannot be shared: where one's gain is the other's loss (an example of which is a zero-sum game). Competition can arise between entities such as organisms, ind ...

only playing a limited role.

In the case of sparassodonts and carnivorans, which has been the most heavily studied, little evidence shows that sparassodonts even encountered their hypothesized placental competitors. Many supposed Pliocene records of South American carnivorans have turned out to be misidentified or misdated. Sparassodonts appear to have been declining in diversity since the middle Miocene

The Miocene ( ) is the first geological epoch of the Neogene Period and extends from about (Ma). The Miocene was named by Scottish geologist Charles Lyell; the name comes from the Greek words (', "less") and (', "new") and means "less recen ...

, with many of the niches once occupied by small sparassodonts being increasingly occupied by carnivorous opossums, which reached sizes of up to roughly 8 kg (~17 lbs). Whether sparassodonts competed with carnivorous opossums or whether opossums began occupying sparassodont niches through passive replacement is still debated. Borhyaenids last occur in the late Miocene

The Miocene ( ) is the first geological epoch of the Neogene Period and extends from about (Ma). The Miocene was named by Scottish geologist Charles Lyell; the name comes from the Greek words (', "less") and (', "new") and means "less recen ...

, about 4 Ma before the first appearance of canids or felids in South America. Thylacosmilid

Thylacosmilidae is an extinct family of metatherian predators, related to the modern marsupials, which lived in South America between the Miocene and Pliocene epochs. Like other South American mammalian predators that lived prior to the Great A ...

s last occur about 3 Ma ago and appear to be rarer at pre-GABI Pliocene sites than Miocene ones.

In general, sparassodonts appear to have been mostly or entirely extinct by the time most nonprocyonid carnivorans arrived, with little overlap between the groups. Purported ecological counterparts between pairs of analogous groups (thylacosmilids and saber-toothed cats, borhyaenids and felids, hathliacynids and weasel

Weasels are mammals of the genus ''Mustela'' of the family Mustelidae. The genus ''Mustela'' includes the least weasels, polecats, stoats, ferrets and European mink. Members of this genus are small, active predators, with long and slend ...

s) neither overlap in time nor abruptly replace one another in the fossil record. Procyonids

Procyonidae is a New World family of the order Carnivora. It comprises the raccoons, ringtails, cacomistles, coatis, kinkajous, olingos, and olinguitos. Procyonids inhabit a wide range of environments and are generally omnivorous.

Characteri ...

dispersed to South America by at least 7 Ma ago, and had achieved a modest endemic

Endemism is the state of a species being found in a single defined geographic location, such as an island, state, nation, country or other defined zone; organisms that are indigenous to a place are not endemic to it if they are also found else ...

radiation

In physics, radiation is the emission or transmission of energy in the form of waves or particles through space or through a material medium. This includes:

* ''electromagnetic radiation'', such as radio waves, microwaves, infrared, visi ...

by the time other carnivorans arrived ('' Cyonasua''-group procyonids

Procyonidae is a New World family of the order Carnivora. It comprises the raccoons, ringtails, cacomistles, coatis, kinkajous, olingos, and olinguitos. Procyonids inhabit a wide range of environments and are generally omnivorous.

Characteri ...

). However, procyonids do not appear to have competed with sparassodonts, the procyonids being large omnivore

An omnivore () is an animal that has the ability to eat and survive on both plant and animal matter. Obtaining energy and nutrients from plant and animal matter, omnivores digest carbohydrates, protein, fat, and fiber, and metabolize the nu ...

s and sparassodonts being primarily hypercarnivorous. Other groups of carnivorans did not arrive in South America until much later. Dogs and weasel

Weasels are mammals of the genus ''Mustela'' of the family Mustelidae. The genus ''Mustela'' includes the least weasels, polecats, stoats, ferrets and European mink. Members of this genus are small, active predators, with long and slend ...

s appear in South America about 2.9 Ma ago, but do not become abundant or diverse until the early Pleistocene. Bear