Goudi coup on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Goudi coup ( el, κίνημα στο Γουδί) was a military

The Goudi coup ( el, κίνημα στο Γουδί) was a military

Macedonia was a region disputed between Greece, the Ottoman Empire and

Macedonia was a region disputed between Greece, the Ottoman Empire and

Greece had been in economic crisis for decades. Public debt (owed above all to the Great Powers) dating back to the

Greece had been in economic crisis for decades. Public debt (owed above all to the Great Powers) dating back to the

The arrest of League officers precipitated events: either the League would act now, or it would be dissolved by a government. The League searched for support among the senior officers, and Colonel Nikolaos Zorbas was chosen as its figurehead. On 14 August, Pangalos liberated two of the arrested officers, thereby provoking Rallis into ordering a clampdown and the arrest of all league members.

On the same night, the League set in motion its bloodless coup. The League members were gathered in the

The arrest of League officers precipitated events: either the League would act now, or it would be dissolved by a government. The League searched for support among the senior officers, and Colonel Nikolaos Zorbas was chosen as its figurehead. On 14 August, Pangalos liberated two of the arrested officers, thereby provoking Rallis into ordering a clampdown and the arrest of all league members.

On the same night, the League set in motion its bloodless coup. The League members were gathered in the

Some of the officers went to Crete, which they knew well, either from having participated in the earlier events or in the formation of its civil guard during the period of autonomy. There, they had also been able to see the political talents of the man who had been Prime Minister of Crete since 9 May 1909: Eleftherios Venizelos. When Prince George of Greece was High Commissioner of Crete, he had found himself in opposition to Venizelos. This gave the latter an anti-dynastic aura that attracted the Goudi insurgents; he was also seen as free from association with the mainland oligarchy's chaos, corruption and incompetence. Starting in October 1909 they had sent him an emissary to sound out his intentions,M. Terrades, pp. 238–239. also suggesting to him that he take the office of Prime Minister of Greece. However, Venizelos did not wish to appear as the soldiers' man, either in Greece or abroad. Neither did he wish to clash head-on with King George I and the "old" political parties. He thus advised them to proceed with legislative elections and entrust implementation of the reform programme to the new assembly.A. Vacalopoulos, p. 212. He went to Athens on and was greeted in Piraeus harbour by eager officers. In January, a Crown Council gathered together the main leaders of the political movements, under the aegis of the King and of Venizelos. The latter played the role of mediator between the forces present: the King, the government, the parliament, the troops and the people. The solutions proposed by the Cretan prime minister were adopted: the convocation of an assembly tasked with constitutional revision; and the resignation of the Mavromichalis government, to be replaced with a transitional government that would organise legislative elections. Leadership of the transitional government was given to

Some of the officers went to Crete, which they knew well, either from having participated in the earlier events or in the formation of its civil guard during the period of autonomy. There, they had also been able to see the political talents of the man who had been Prime Minister of Crete since 9 May 1909: Eleftherios Venizelos. When Prince George of Greece was High Commissioner of Crete, he had found himself in opposition to Venizelos. This gave the latter an anti-dynastic aura that attracted the Goudi insurgents; he was also seen as free from association with the mainland oligarchy's chaos, corruption and incompetence. Starting in October 1909 they had sent him an emissary to sound out his intentions,M. Terrades, pp. 238–239. also suggesting to him that he take the office of Prime Minister of Greece. However, Venizelos did not wish to appear as the soldiers' man, either in Greece or abroad. Neither did he wish to clash head-on with King George I and the "old" political parties. He thus advised them to proceed with legislative elections and entrust implementation of the reform programme to the new assembly.A. Vacalopoulos, p. 212. He went to Athens on and was greeted in Piraeus harbour by eager officers. In January, a Crown Council gathered together the main leaders of the political movements, under the aegis of the King and of Venizelos. The latter played the role of mediator between the forces present: the King, the government, the parliament, the troops and the people. The solutions proposed by the Cretan prime minister were adopted: the convocation of an assembly tasked with constitutional revision; and the resignation of the Mavromichalis government, to be replaced with a transitional government that would organise legislative elections. Leadership of the transitional government was given to

The Goudi coup ( el, κίνημα στο Γουδί) was a military

The Goudi coup ( el, κίνημα στο Γουδί) was a military coup d'état

A coup d'état (; French for 'stroke of state'), also known as a coup or overthrow, is a seizure and removal of a government and its powers. Typically, it is an illegal seizure of power by a political faction, politician, cult, rebel group, m ...

that took place in Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders ...

on the night of , starting at the barracks in Goudi

Goudi (, since 2006; formerly Γουδί ) is a residential neighbourhood of Athens, Greece, on the eastern part of town and on the foothills of Mount Hymettus.

History

The name of the area derives from the 19th century Goudi (Γουδή) famil ...

, a neighborhood on the eastern outskirts of Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates ...

. The coup was a pivotal event in modern Greek history, as it led to the arrival of Eleftherios Venizelos in Greece and his eventual appointment as Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister i ...

. At one stroke, this put an end to the old political system, and ushered in a new period. Henceforth and for several decades, Greek political life would be dominated by two opposing forces: liberal, republican Venizelism

Venizelism ( el, Βενιζελισμός) was one of the major political movements in Greece from the 1900s until the mid-1970s.

Main ideas

Named after Eleftherios Venizelos, the key characteristics of Venizelism were:

*Greek irredentism: T ...

and conservative, monarchist anti-Venizelism.

The coup itself was the result of simmering tensions in Greek society, which reeled under the effects of the disastrous Greco-Turkish War of 1897

The Greco-Turkish War of 1897 or the Ottoman-Greek War of 1897 ( or ), also called the Thirty Days' War and known in Greece as the Black '97 (, ''Mauro '97'') or the Unfortunate War ( el, Ατυχής πόλεμος, Atychis polemos), was a w ...

, financial troubles, a lack of necessary reforms and disillusionment with the established political system. Emulating the Young Turks, several junior Army officers founded a secret society, the Military League. With Colonel Nikolaos Zorbas as their figurehead, on the night of 15 August, the Military League, having gathered together its troops in the Goudi barracks, issued a pronunciamiento to the government demanding an immediate turnaround for the country and its armed forces.

King George I George I or 1 may refer to:

People

* Patriarch George I of Alexandria (fl. 621–631)

* George I of Constantinople (d. 686)

* George I of Antioch (d. 790)

* George I of Abkhazia (ruled 872/3–878/9)

* George I of Georgia (d. 1027)

* Yuri Dolgor ...

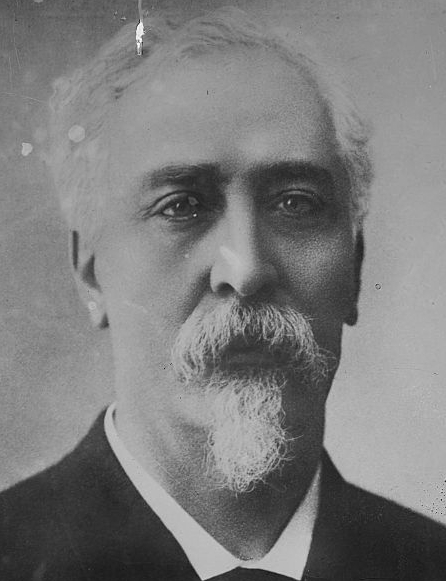

gave in and replaced Prime Minister Dimitrios Rallis

Dimitrios Rallis (Greek: Δημήτριος Ράλλης; 1844–1921) was a Greek politician.

He was born in Athens in 1844. He was descended from an old Greek political family. Before Greek independence, his grandfather, Alexander Rallis, ...

with Kyriakoulis Mavromichalis

Kyriakoulis Petrou Mavromichalis (, 1850–1916) was a Greek politician of the late 19th and early 20th centuries who briefly served as the 30th Prime Minister of Greece.

Mavromichalis was born in Athens in 1850 into the renowned Mavromichalis ...

, without however satisfying the insurgents, who resorted to a large public demonstration the following month. When a stalemate was reached, the coup leaders appealed to a new and providential figure, the Cretan Eleftherios Venizelos, who respected democratic norms in calling for new elections. After his allies' twin victories in the Hellenic Parliament in August

August is the eighth month of the year in the Julian and Gregorian calendars, and the fifth of seven months to have a length of 31 days. Its zodiac sign is Leo and was originally named ''Sextilis'' in Latin because it was the 6th month in ...

and November 1910, Venizelos became Prime Minister and proceeded with the reforms demanded by the coup's instigators.

Greece at the beginning of the 20th century

TheCongress of Berlin

The Congress of Berlin (13 June – 13 July 1878) was a diplomatic conference to reorganise the states in the Balkan Peninsula after the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–78, which had been won by Russia against the Ottoman Empire. Represented at th ...

in 1878 and the 1881 Convention of Constantinople

The Convention of Constantinople is a treaty concerning the use of the Suez Canal in Egypt. It was signed on 29 October 1888 by the United Kingdom, Germany, Austria-Hungary, Spain, France, Italy, the Netherlands, the Russian Empire, and the Ott ...

had been successes for Greek diplomacy. There, the country had won Thessaly

Thessaly ( el, Θεσσαλία, translit=Thessalía, ; ancient Thessalian: , ) is a traditional geographic and modern administrative region of Greece, comprising most of the ancient region of the same name. Before the Greek Dark Ages, The ...

and part of Epirus

sq, Epiri rup, Epiru

, native_name_lang =

, settlement_type = Historical region

, image_map = Epirus antiquus tabula.jpg

, map_alt =

, map_caption = Map of ancient Epirus by Heinri ...

. In order to continue achieving the Megali Idea

The Megali Idea ( el, Μεγάλη Ιδέα, Megáli Idéa, Great Idea) is a nationalist and irredentist concept that expresses the goal of reviving the Byzantine Empire, by establishing a Greek state, which would include the large Greek popu ...

, Greece then turned to Macedonia and Crete

Crete ( el, Κρήτη, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cyprus, ...

, but met with severe setbacks.

Military humiliations

From 1895, following the Hamidian massacres ofArmenians

Armenians ( hy, հայեր, '' hayer'' ) are an ethnic group native to the Armenian highlands of Western Asia. Armenians constitute the main population of Armenia and the ''de facto'' independent Artsakh. There is a wide-ranging diasp ...

in the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

; Cretan Christians, then under Ottoman domination, demanded self-government on their island under the protection of the great powers. Massacres of Christians by Muslims led Greece to intervene, first by accepting the departure of volunteers from its shores, then by more and more directly sending part of its fleet, followed by troops at the beginning of 1897 just when Cretans themselves declared '' enosis'' (union with Greece). The intervention of the European powers (France, Great Britain, Italy, Russia, Austria-Hungary and Germany) forced Greece to back down. The opposition criticised the feebleness and indecisiveness of the government, which declared war on the Ottomans at the beginning of April. Fighting lasted a month, which gave its name to the conflict (the Thirty Days' War); the Greek defeat was thorough. Although Greece lost only small amounts territory on its northern border, it was forced to pay huge war reparations of 4 million Ottoman pounds to the victor. Coming on the heels of the public insolvency

In accounting, insolvency is the state of being unable to pay the debts, by a person or company ( debtor), at maturity; those in a state of insolvency are said to be ''insolvent''. There are two forms: cash-flow insolvency and balance-sheet ...

declared in 1893, it meant that Greece had to accept an International Financial Control commission (Διεθνής Οικονομικός Έλεγχος), which in effect diverted the Greek state's main income sources (state monopolies and port customs tariffs) to the repayment of Greece's public loans. Crete however became an autonomous state

An autonomous administrative division (also referred to as an autonomous area, entity, unit, region, subdivision, or territory) is a subnational administrative division or internal territory of a sovereign state that has a degree of autonomy— ...

under international supervision, while remaining under the Sultan's suzerainty.

Macedonia

Macedonia was a region disputed between Greece, the Ottoman Empire and

Macedonia was a region disputed between Greece, the Ottoman Empire and Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedo ...

(created at the Congress of Berlin). On , the feast day of the Prophet Elijah

Elijah ( ; he, אֵלִיָּהוּ, ʾĒlīyyāhū, meaning "My El (deity), God is Yahweh/YHWH"; Greek form: Elias, ''Elías''; syr, ܐܸܠܝܼܵܐ, ''Elyāe''; Arabic language, Arabic: إلياس or إليا, ''Ilyās'' or ''Ilyā''. ) w ...

(Bulg. ''Ilinden''), the Ilinden–Preobrazhenie Uprising

The Ilinden–Preobrazhenie Uprising, or simply the Ilinden Uprising of August–October 1903 ( bg, Илинденско-Преображенско въстание, Ilindensko-Preobrazhensko vastanie; mk, Илинденско востание, ...

, sponsored by the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization

The Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO; bg, Вътрешна Македонска Революционна Организация (ВМРО), translit=Vatrešna Makedonska Revoljucionna Organizacija (VMRO); mk, Внатр� ...

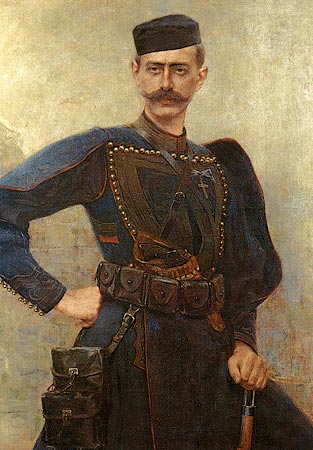

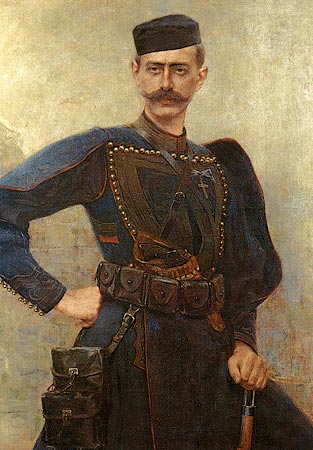

, began. The uprising failed, and Turkish reprisals were severe, with 2,000 killed and villages and homes razed. Following these events, many Greeks became concerned with the level of Bulgarian activity in Macedonia. The '' Ethniki Etairia'' (National Society) was set up, which sent armed bands of Greeks (''makedonomakhoi''), tacitly aided by the government in Athens, which provided financial support through its consular agents such as Ion Dragoumis and training from military advisers such as Pavlos Melas

Pavlos Melas ( el, Παύλος Μελάς, ''Pávlos Melás''; March 29, 1870 – October 13, 1904) was a Greek revolutionary and artillery officer of the Hellenic Army. He participated in the Greco-Turkish War of 1897 and was amongst the first ...

. This began what is known in Greece as the "Macedonian Struggle

The Macedonian Struggle ( bg, Македонска борба; el, Μακεδονικός Αγώνας; mk, Борба за Македонија; sr, Борба за Македонију; tr, Makedonya Mücadelesi) was a series of social, po ...

", where Greeks clashed with Bulgarian ''komitadjis'', while both sides clashed with the Ottoman army and gendarmerie. Reprisals took many forms, including pillage, arson and assassination. Deeply concerned, the Western powers decided to intervene. The eventual plan was for an administrative reorganisation of the region that would allow for an ethnic-based partition. Thus, each of the ethnic groups concerned sought to strengthen its position so as to gain a maximum of territory when the potential partition came. The successes and sacrifices of young officers such as Melas restored the image of part of the army. In turn, the meddling of the European powers in internal Ottoman affairs contributed to the outbreak of the Young Turk Revolution

The Young Turk Revolution (July 1908) was a constitutionalist revolution in the Ottoman Empire. The Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), an organization of the Young Turks movement, forced Sultan Abdul Hamid II to restore the Ottoman Consti ...

of July 1908, which put an end to the Greek-Bulgarian clashes in Macedonia.

Consequences of the Young Turk Revolution

Greece at the time was still embroiled in the Cretan question. In 1905, Eleftherios Venizelos had led theTheriso revolt

The Theriso revolt ( el, Επανάσταση του Θερίσου) was an insurrection that broke out in March 1905 against the government of Crete, then an autonomous state under Ottoman suzerainty. The revolt was led by the Cretan politicia ...

against High Commissioner George of Greece, who had been appointed by the European powers, and demanded ''enosis''. In 1906, the Prince resigned, and a new Commissioner, the former Greek Prime Minister Alexandros Zaimis

Alexandros Zaimis ( el, Αλέξανδρος Ζαΐμης; 9 November 1855 – 15 September 1936) was a Greek politician who served as Greece's Prime Minister, Minister of the Interior, Minister of Justice, and High Commissioner of Crete. He serv ...

, was installed. The Young Turk Revolution pushed the Cretans to unilaterally proclaim definitive ''enosis'', taking advantage of the absence of the new High Commissioner.A. Vacalopoulos, p. 206.

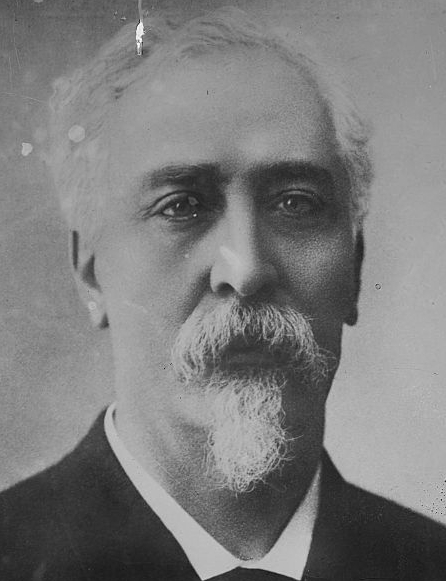

Anti-Greek demonstrations took place in Turkey, where the press launched a similar campaign. The European powers displayed hostility toward Greece, while Georgios Theotokis

Georgios Theotokis ( el, Γεώργιος Θεοτόκης, 1844 in Corfu – 12 January 1916 in Athens) was a Greek politician and Prime Minister of Greece, serving the post four times. He represented the Modernist Party or ''Neoteristikon Ko ...

’ government was subject to increasing criticism. His replacement with Rallis had little effect. The new prime minister hastened to show signs of goodwill toward the Turkish ambassador and the Western powers. Wishing to avoid a new Greco-Turkish war, he criticised the "Cretan revolutionaries" and declared his willingness to abide by the Great Powers' decisions. Indignation toward the government's weaknesses and timorous attitude mounted, among the populace as well as in the army, above all among the young officers who had fought in Macedonia. The idea of imitating the Young Turk officers began to spread.

Economic and social situation

Greece had been in economic crisis for decades. Public debt (owed above all to the Great Powers) dating back to the

Greece had been in economic crisis for decades. Public debt (owed above all to the Great Powers) dating back to the War of Independence

This is a list of wars of independence (also called liberation wars). These wars may or may not have been successful in achieving a goal of independence.

List

See also

* Lists of active separatist movements

* List of civil wars

* List o ...

reached new heights in the 1890s. At that point the government of Charilaos Trikoupis

Charilaos Trikoupis ( el, Χαρίλαος Τρικούπης; 11 July 1832 – 30 March 1896) was a Greek politician who served as a Prime Minister of Greece seven times from 1875 until 1895.

He is best remembered for introducing the vote of c ...

recognised that the country was bankrupt by deciding to lower the public debt to 30% of its value, which angered the creditors, particularly the European powers. At the same time, export of the Zante currant

Zante currants, Corinth raisins, Corinthian raisins or outside the United States simply currants, are raisins of the small, sweet, seedless grape cultivar Black Corinth (''Vitis vinifera''). The name comes from the Anglo-French phrase "raisins ...

entered a crisis. A new phenomenon then began: emigration of the working population. The number of emigrants (especially to the United States) went from 1,108 in 1890 to 39,135 in 1910 (of 2.8 million inhabitants); significantly, remittances from America and Egypt fell amid economic slowdown in 1908. Economic growth was too slow for the workers and farmers who left to seek work elsewhere. Until that time, only highlanders and landless island dwellers had left. However, this economic growth did lead to the creation, as elsewhere in Europe in the same period, of a middle class born out of industrial development, of growth in the number of bureaucrats (linked to political clientelism) and to an urban explosion. In the mid-1900s, this middle class could not understand why the country was prosperous while the state's finances were in such poor shape. Politicians, also dissatisfied with government policy, reacted as well. In 1906, a group of youngish radicals nicknamed the " Japanese Group" (Ομάς Ιαπώνων), in reference to the dynamism of the Meiji period

The is an era of Japanese history that extended from October 23, 1868 to July 30, 1912.

The Meiji era was the first half of the Empire of Japan, when the Japanese people moved from being an isolated feudal society at risk of colonization ...

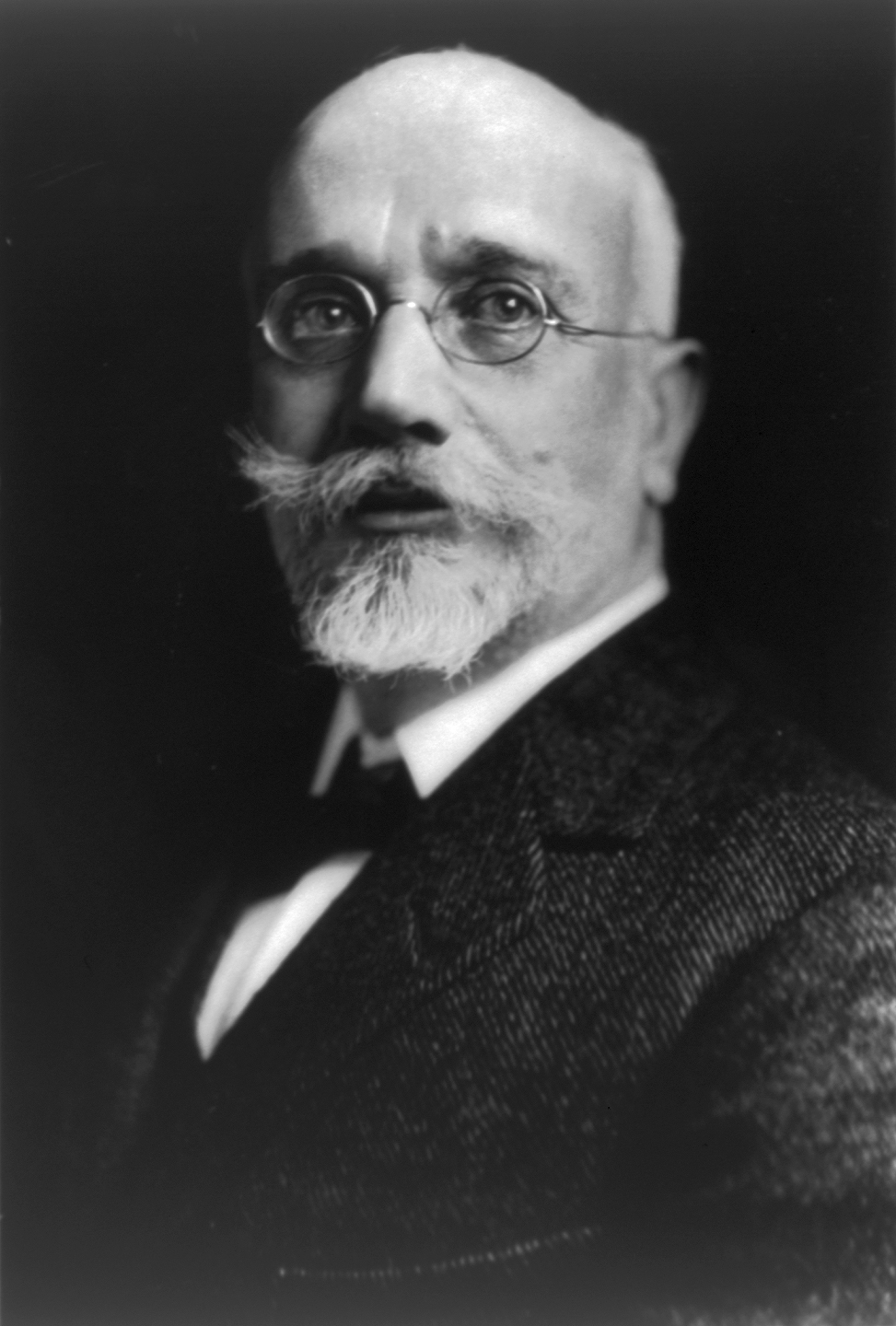

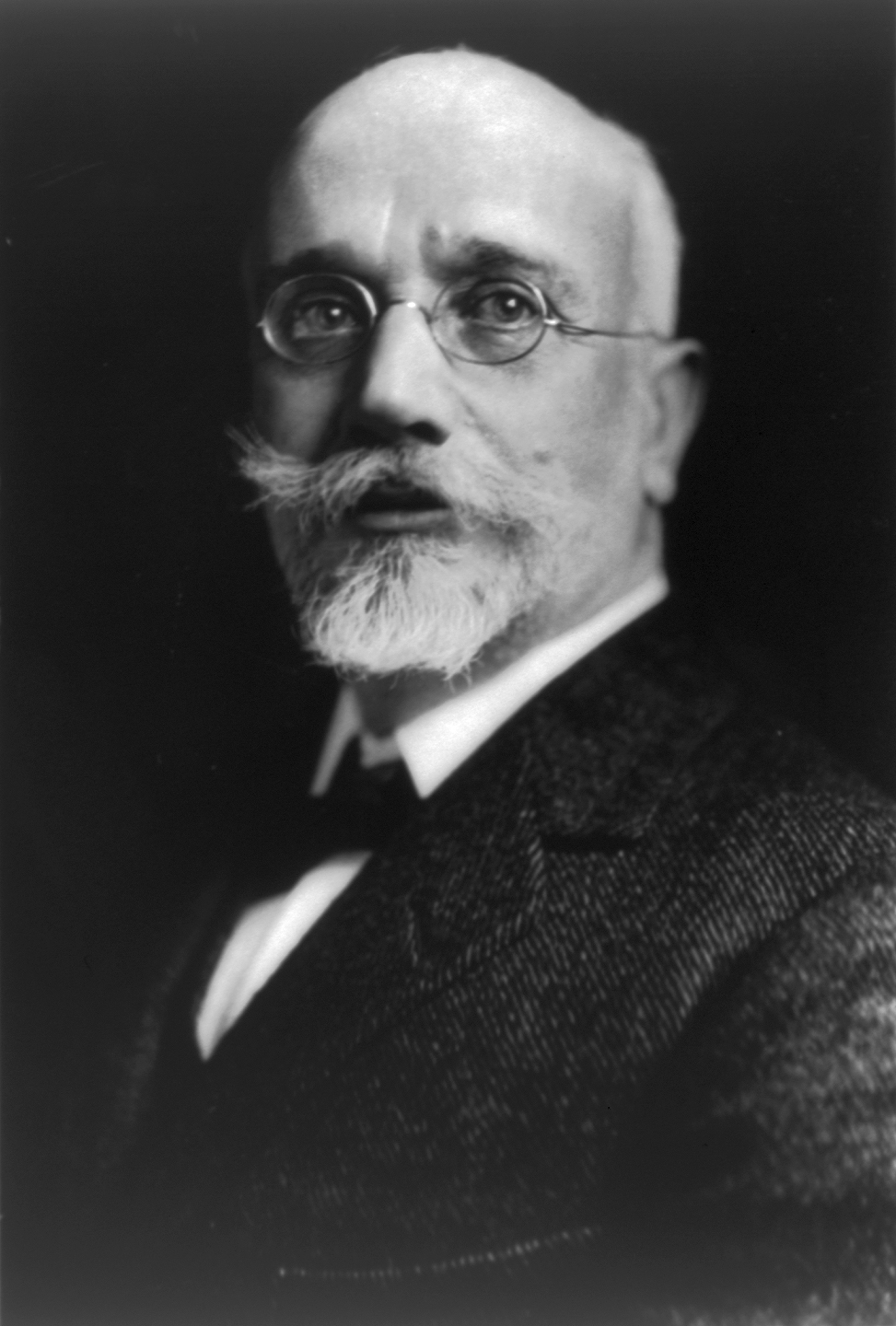

, formed around the titular leadership of Stephanos Dragoumis

Stefanos Dragoumis ( el, Στέφανος Δραγούμης; 1842September 17, 1923) was a judge, writer and the Prime Minister of Greece from January to October 1910. He was the father of Ion Dragoumis.

Early years

Dragoumis was born in Athen ...

, with Dimitrios Gounaris

Dimitrios Gounaris (; 5 January 1867 – 28 November 1922) was a Greek politician who served as the Prime Minister of Greece from 25 February to 10 August 1915 and 26 March 1921 to 3 May 1922. Leader of the People's Party, he was the main ri ...

its moving spirit. It criticised the old oligarchy that was ruining the country and demanded radical reforms. The group of “Sociologists

This is a list of sociologists. It is intended to cover those who have made substantive contributions to social theory and research, including any sociological subfield. Scientists in other fields and philosophers are not included, unless at least ...

” (Κοινωνιολόγοι), especially influenced by Marxism

Marxism is a left-wing to far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand class relations and social conflict and a dialectical ...

, also called for modernisation of the state apparatus and the economy.

Coup

Military League

The Military League (Στρατιωτικός Σύνδεσμος) was formed in October 1908 out of two groups: one of Army NCOs (with members including future generals Nikolaos Plastiras and Georgios Kondylis) and one of junior officers around Theodoros Pangalos. They were motivated by a variety of reasons: a desire for reforms that was prevalent in wide parts of society was combined with frustration at the slow rate of promotions and the absence of meritocracy, especially among graduates of theMilitary Academy

A military academy or service academy is an educational institution which prepares candidates for service in the officer corps. It normally provides education in a military environment, the exact definition depending on the country concerned. ...

. Other officers from the Army, the Navy and the gendarmerie joined up later, and by June 1909, had spread out over the Greek military.

At that time the Military League's demands were limited to an increased military budget, its reorganisation and modernisation, as well as the dismissal of the Princes from the Army. Although the Theotokis government had increased supplies of arms and munitions, he had also reinstated Crown Prince Constantine

Constantine most often refers to:

* Constantine the Great, Roman emperor from 306 to 337, also known as Constantine I

*Constantine, Algeria, a city in Algeria

Constantine may also refer to:

People

* Constantine (name), a masculine given name ...

, who had led the Army in the 1897 war, as Chief Inspector of the Army. Also, despite demands, he had authorised only a few officers to pursue further studies in France and Germany.M. Terrades, pp. 235–236.

Army action

The Military League, now numbering about 1,300, began by engaging in a form of lobbying by putting pressure on those in power. It had already scored a success with the July 1909 resignation of Theotokis, its ''bête noire'' and a symbol of the parliamentary clientelism it hated. But his successor Dimitrios Rallis immediately alienated the League by paying tribute to Constantine's major role in the war of 1897, by recalling all officers present in Macedonia, by demanding Great Power intervention in Crete and by arresting over a dozen of the League's members for insubordination on 12 August. The arrest of League officers precipitated events: either the League would act now, or it would be dissolved by a government. The League searched for support among the senior officers, and Colonel Nikolaos Zorbas was chosen as its figurehead. On 14 August, Pangalos liberated two of the arrested officers, thereby provoking Rallis into ordering a clampdown and the arrest of all league members.

On the same night, the League set in motion its bloodless coup. The League members were gathered in the

The arrest of League officers precipitated events: either the League would act now, or it would be dissolved by a government. The League searched for support among the senior officers, and Colonel Nikolaos Zorbas was chosen as its figurehead. On 14 August, Pangalos liberated two of the arrested officers, thereby provoking Rallis into ordering a clampdown and the arrest of all league members.

On the same night, the League set in motion its bloodless coup. The League members were gathered in the Goudi

Goudi (, since 2006; formerly Γουδί ) is a residential neighbourhood of Athens, Greece, on the eastern part of town and on the foothills of Mount Hymettus.

History

The name of the area derives from the 19th century Goudi (Γουδή) famil ...

barracks: several hundred junior officers, non-commissioned officers, simple soldiers, gendarmes and civilians threatened to march on Athens if their demands were not met. The armed forces, in particular the young officers, sent Rallis' government a pronunciamento containing their demands (the previous day, Rallis had declined to receive a deputation seeking to hand over the manifesto). Part of it was purely internal in nature: for instance, the soldiers challenged the promotion system, with its limited prospects for advancement. Another part was political and demanded profound reforms in the country: in its political functioning, as well as social, economic and military. The troops called for naval and land rearmament, and asked that the Navy and War ministers belong to the military. The insurgents did not call for the King's abdication or the abolition of the monarchy, remaining loyal subjects. Neither did they announce a military dictatorship or even wish to change the government. They respected the institutions of parliamentary government. However, the officers did demand that the royal princes, chiefly the Crown Prince Constantine, on whom they blamed the defeat of 1897, be relieved of their posts and expelled from the army. Finally, the League called for a lowering of tax burdens.C. Personnaz, p. 76.

The prime minister opened ''pro forma'' negotiations with the revolutionaries who, in order to speed them up, resorted to the people of Athens.A. Vacalopoulos, p. 211.

Popular demands

A large popular demonstration, organised and supervised by the soldiers, took place in the streets of Athens on 14 September 1909. The demonstrators, who had come from Athens and thePiraeus

Piraeus ( ; el, Πειραιάς ; grc, Πειραιεύς ) is a port city within the Athens urban area ("Greater Athens"), in the Attica region of Greece. It is located southwest of Athens' city centre, along the east coast of the Saron ...

, demanded the imposition of a revenue tax, protectionism

Protectionism, sometimes referred to as trade protectionism, is the economic policy of restricting imports from other countries through methods such as tariffs on imported goods, import quotas, and a variety of other government regulatio ...

, the granting of tenure to bureaucrats (so they would no longer depend on politicians for their jobs), better working conditions and the condemnation of usury. King George I, unwilling to follow in the footsteps of his predecessor Otto, who had been forced from the throne under similar circumstances in 1862,M. Terrades, p. 237. pushed Prime Minister Rallis to resign and replaced him with Kyriakoulis Mavromichalis

Kyriakoulis Petrou Mavromichalis (, 1850–1916) was a Greek politician of the late 19th and early 20th centuries who briefly served as the 30th Prime Minister of Greece.

Mavromichalis was born in Athens in 1850 into the renowned Mavromichalis ...

.

Stalemate

The negotiations dragged on, and Colonel Zorbas lacked the political skills to keep up with the seasoned veterans on the government side. Mavromichalis, in securing passage of a large number of mildly reformist bills, implemented part of the programme demanded by the Military League, this time under threat of an actual military takeover. Thus, the general staff was reorganised and those close to Constantine (such asIoannis Metaxas

Ioannis Metaxas (; el, Ιωάννης Μεταξάς; 12th April 187129th January 1941) was a Greek military officer and politician who served as the Prime Minister of Greece from 1936 until his death in 1941. He governed constitutionally for t ...

) were removed while budget cuts were made in order to finance army modernisation. But his government clearly showed that the old system endured: only Finance Minister Athanasios Eftaxias had reformist ideas. With the revolution running out of steam, the League began to crumble. It was not a real political movement: its ideology and programme lacked coherence; its leaders were popular but unskilled. They were above all soldiers ill at ease outside their barracks. The League had known how to link its corporatist demands to public discontent by using populist and nationalist slogans, but it unsettled the bourgeoisie. Although it saw the necessity of modernising the country, the middle classes feared the drift towards a military dictatorship, considered deleterious to the normal progress of affairs.

Appeal to Venizelos

Some of the officers went to Crete, which they knew well, either from having participated in the earlier events or in the formation of its civil guard during the period of autonomy. There, they had also been able to see the political talents of the man who had been Prime Minister of Crete since 9 May 1909: Eleftherios Venizelos. When Prince George of Greece was High Commissioner of Crete, he had found himself in opposition to Venizelos. This gave the latter an anti-dynastic aura that attracted the Goudi insurgents; he was also seen as free from association with the mainland oligarchy's chaos, corruption and incompetence. Starting in October 1909 they had sent him an emissary to sound out his intentions,M. Terrades, pp. 238–239. also suggesting to him that he take the office of Prime Minister of Greece. However, Venizelos did not wish to appear as the soldiers' man, either in Greece or abroad. Neither did he wish to clash head-on with King George I and the "old" political parties. He thus advised them to proceed with legislative elections and entrust implementation of the reform programme to the new assembly.A. Vacalopoulos, p. 212. He went to Athens on and was greeted in Piraeus harbour by eager officers. In January, a Crown Council gathered together the main leaders of the political movements, under the aegis of the King and of Venizelos. The latter played the role of mediator between the forces present: the King, the government, the parliament, the troops and the people. The solutions proposed by the Cretan prime minister were adopted: the convocation of an assembly tasked with constitutional revision; and the resignation of the Mavromichalis government, to be replaced with a transitional government that would organise legislative elections. Leadership of the transitional government was given to

Some of the officers went to Crete, which they knew well, either from having participated in the earlier events or in the formation of its civil guard during the period of autonomy. There, they had also been able to see the political talents of the man who had been Prime Minister of Crete since 9 May 1909: Eleftherios Venizelos. When Prince George of Greece was High Commissioner of Crete, he had found himself in opposition to Venizelos. This gave the latter an anti-dynastic aura that attracted the Goudi insurgents; he was also seen as free from association with the mainland oligarchy's chaos, corruption and incompetence. Starting in October 1909 they had sent him an emissary to sound out his intentions,M. Terrades, pp. 238–239. also suggesting to him that he take the office of Prime Minister of Greece. However, Venizelos did not wish to appear as the soldiers' man, either in Greece or abroad. Neither did he wish to clash head-on with King George I and the "old" political parties. He thus advised them to proceed with legislative elections and entrust implementation of the reform programme to the new assembly.A. Vacalopoulos, p. 212. He went to Athens on and was greeted in Piraeus harbour by eager officers. In January, a Crown Council gathered together the main leaders of the political movements, under the aegis of the King and of Venizelos. The latter played the role of mediator between the forces present: the King, the government, the parliament, the troops and the people. The solutions proposed by the Cretan prime minister were adopted: the convocation of an assembly tasked with constitutional revision; and the resignation of the Mavromichalis government, to be replaced with a transitional government that would organise legislative elections. Leadership of the transitional government was given to Stephanos Dragoumis

Stefanos Dragoumis ( el, Στέφανος Δραγούμης; 1842September 17, 1923) was a judge, writer and the Prime Minister of Greece from January to October 1910. He was the father of Ion Dragoumis.

Early years

Dragoumis was born in Athen ...

, considered an "independent". Nikolaos Zorbas was made Minister of Land Forces. In exchange, Venizelos managed to convince the Military League to dissolve itself so as not to hinder the political process. In March 1910, an initially reluctant sovereign called new elections; three days later, the League announced its dissolution. Venizelos went back to Crete.

Using his Cretan citizenship as a pretext (the island had declared union with Greece but Greece had yet to recognise this), Venizelos did not take part in the elections, held in August 1910. His allies nominated him for a seat in Atticoboeotia but he stayed away from the electoral campaign. He was on a diplomatic tour of Western Europe when he learned that he had been elected and that deputies allied to him had obtained a relative majority with 146 of 362 seats. He thus returned to Athens amid rapturous public acclaim; the Dragoumis government resigned and Venizelos became prime minister in October 1910. He surrounded himself with collaborators bent on reform policies and began to apply the programme of the Goudi revolutionaries, strongly backed by public opinion. The Austrian ambassador observed on 28 October 1910: "Venizelos is a sort of popular tribune and almost the dictator of Greece. The enthusiasm of the people, who acclaim him everywhere, is striking". He decided to call immediate new elections in order to strengthen his majority: the assembly elected in August continued to be dominated by the old politicians. These took place on . Venizelos was careful to present himself as an adversary of the "old" parties (which boycotted the elections), but also as free from influence by the Military League that had sought him out after the Goudi coup. Thus he did not hesitate to take as an aide-de-camp Ioannis Metaxas

Ioannis Metaxas (; el, Ιωάννης Μεταξάς; 12th April 187129th January 1941) was a Greek military officer and politician who served as the Prime Minister of Greece from 1936 until his death in 1941. He governed constitutionally for t ...

, a ''bête noire'' of the League whom it had removed. Venizelos' Liberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world. The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left.

__TOC__ Active liberal parties

This is a li ...

won the elections with an overwhelming majority of 300 out of 362 deputies.

Reformist policies

The reforms of the Venizelos government were numerous, and allowed Greece to modernise and thus be better prepared for the Balkan Wars and World War I. The King supported them, seeing in his prime minister the best hope of stemming theanti-monarchism

Criticism of monarchy can be targeted against the general form of government—monarchy—or more specifically, to particular monarchical governments as controlled by hereditary royal families. In some cases, this criticism can be curtailed by l ...

that had surfaced in 1897 and gained renewed momentum in the 1908–1909 crisis.

To the people who wanted the assembly elected in 1910 to be a constituent assembly, Venizelos replied that he considered it more of a "revisionary assembly". The 50 constitutional amendments of 1911, prepared by a commission directed by Stephanos Dragoumis

Stefanos Dragoumis ( el, Στέφανος Δραγούμης; 1842September 17, 1923) was a judge, writer and the Prime Minister of Greece from January to October 1910. He was the father of Ion Dragoumis.

Early years

Dragoumis was born in Athen ...

, led to the frequently expressed opinion that after this date, Greece had an entirely new fundamental law, the Greek Constitution of 1911. This revision reformed the status of property by allowing for expropriation

Nationalization (nationalisation in British English) is the process of transforming privately-owned assets into public assets by bringing them under the public ownership of a national government or state. Nationalization usually refers to pri ...

in the national interest, opening up the possibility of land reform

Land reform is a form of agrarian reform involving the changing of laws, regulations, or customs regarding land ownership. Land reform may consist of a government-initiated or government-backed property redistribution, generally of agricultural ...

; were distributed to 4,000 farm families in Thessaly

Thessaly ( el, Θεσσαλία, translit=Thessalía, ; ancient Thessalian: , ) is a traditional geographic and modern administrative region of Greece, comprising most of the ancient region of the same name. Before the Greek Dark Ages, The ...

. Agricultural education was encouraged, as well as farming cooperatives, a Ministry of Agriculture was created and an agronomist named in each region. Bureaucrats were given greater security of tenure and hiring for civil service posts began to be done by public examination. Judges were protected by a Superior Magistracy Council. Social legislation ameliorated the condition of the working class: child labour was abolished, as was nighttime labour by women, and a minimum wage introduced for both; Sunday was made an obligatory day of rest; primary education was made free and compulsory; and a social insurance system was created. The right of labour union

A trade union (labor union in American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers intent on "maintaining or improving the conditions of their employment", ch. I such as attaining better wages and benefits (su ...

s to function was recognised. Stabilisation of the drachma

The drachma ( el, δραχμή , ; pl. ''drachmae'' or ''drachmas'') was the currency used in Greece during several periods in its history:

# An ancient Greek currency unit issued by many Greek city states during a period of ten centuries, fr ...

once again allowed for foreign borrowing. The state budget showed a surplus in 1911 and 1912 after many years of deficit, and tax evasion

Tax evasion is an illegal attempt to defeat the imposition of taxes by individuals, corporations, trusts, and others. Tax evasion often entails the deliberate misrepresentation of the taxpayer's affairs to the tax authorities to reduce the tax ...

was curbed. The tax on sugar was cut by 50% and a progressive income tax

A progressive tax is a tax in which the tax rate increases as the taxable amount increases.Sommerfeld, Ray M., Silvia A. Madeo, Kenneth E. Anderson, Betty R. Jackson (1992), ''Concepts of Taxation'', Dryden Press: Fort Worth, TX The term ''progre ...

introduced. Taken together, the reforms helped neutralise the development of strong socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the ...

and agrarian movements seen elsewhere in the Balkans in that period. The army and navy were reorganised with help from France, which sent a military mission led by General Eydoux (Germany had reformed the Turkish Army). The navy was reorganised by a British mission that Admiral Tufnell headed. However, Venizelos, anxious to show that he was no military puppet, excluded soldiers from political life, released officers arrested for attempting to thwart the Goudi coup, and restored to Crown Prince Constantine (given the new post of inspector-general of the army), along with his brothers, their army posts. This angered the members of the defunct Military League, who for a time thought of recreating it; indeed of carrying out another coup.M. Terrades, p. 241.

Notes

References

* ''An Index of Events in the Military History of the Greek Nation'', Hellenic Army General Staff, Army History Directorate, Athens, 1998. * Richard Clogg, ''A Concise History of Greece'', Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1992. * * S. Victor Papacosma, ''The Military in Greek Politics: The 1909 Coup D'état'', Kent State University Press, 1977. * Charles Personnaz, ''Venizélos. Le fondateur de la Grèce moderne.'', Bernard Giovanangeli Éditeur, 2008. * Nicolas Svoronos, ''Histoire de la Grèce moderne'', Que Sais-Je ?, PUF, 1964. * * Constantin Tsoucalas, ''La Grèce de l'indépendance aux colonels'',Maspero People with the name Maspero include:

*François Maspero (1932–2015), French author and journalist

*Gaston Maspero (1846–1916), French Egyptologist

*Georges Maspero (1872–1942), French sinologist, son of Gaston

*Henri Maspero (1882–1945), F ...

, Paris, 1970. (for the original English version). ()

* Apostolos Vacalopoulos, ''Histoire de la Grèce moderne'', Horvath, 1975.

{{DEFAULTSORT:Goudi Coup

Conflicts in 1909

1909 in Greece

1900s in Greek politics

Military coups in Greece

Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders ...

History of Greece (1909–1924)

History of Greece (1863–1909)

August 1909 events