Gladius Dei on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

With the start of the Cold War he was increasingly frustrated by rising McCarthyism. As a 'suspected communist', he was required to testify to the House Un-American Activities Committee, where he was termed "one of the world's foremost apologists for Stalin and company." He was listed by HUAC as being "affiliated with various peace organizations or Communist fronts." Being in his own words a non-communist rather than an anti-communist, Mann openly opposed the allegations: "As an American citizen of German birth I finally testify that I am painfully familiar with certain political trends. Spiritual intolerance, political inquisitions, and declining legal security, and all this in the name of an alleged 'state of emergency.' ... That is how it started in Germany." As Mann joined protests against the jailing of the

With the start of the Cold War he was increasingly frustrated by rising McCarthyism. As a 'suspected communist', he was required to testify to the House Un-American Activities Committee, where he was termed "one of the world's foremost apologists for Stalin and company." He was listed by HUAC as being "affiliated with various peace organizations or Communist fronts." Being in his own words a non-communist rather than an anti-communist, Mann openly opposed the allegations: "As an American citizen of German birth I finally testify that I am painfully familiar with certain political trends. Spiritual intolerance, political inquisitions, and declining legal security, and all this in the name of an alleged 'state of emergency.' ... That is how it started in Germany." As Mann joined protests against the jailing of the

Mann's diaries reveal his struggles with his homosexuality, which found reflection in his works, most prominently through the obsession of the elderly Aschenbach for the 14-year-old Polish boy Tadzio in the novella ''

Mann's diaries reveal his struggles with his homosexuality, which found reflection in his works, most prominently through the obsession of the elderly Aschenbach for the 14-year-old Polish boy Tadzio in the novella '' Mann was a friend of the violinist and painter Paul Ehrenberg, for whom he had feelings as a young man (at least until around 1903 when there is evidence that those feelings had cooled). The attraction that he felt for Ehrenberg, which is corroborated by notebook entries, caused Mann difficulty and discomfort and may have been an obstacle to his marrying an English woman, Mary Smith, whom he met in 1901. In 1950, Mann met the 19-year-old waiter Franz Westermeier, confiding to his diary "Once again this, once again love".. In 1975, when Mann's diaries were published, creating a national sensation in Germany, the retired Westermeier was tracked down in the United States: he was flattered to learn he had been the object of Mann's obsession, but also shocked at its depth.

Although Mann had always denied his novels had autobiographical components, the unsealing of his diaries revealing how consumed his life had been with unrequited and sublimated passion resulted in a reappraisal of his work. Thomas's son

Mann was a friend of the violinist and painter Paul Ehrenberg, for whom he had feelings as a young man (at least until around 1903 when there is evidence that those feelings had cooled). The attraction that he felt for Ehrenberg, which is corroborated by notebook entries, caused Mann difficulty and discomfort and may have been an obstacle to his marrying an English woman, Mary Smith, whom he met in 1901. In 1950, Mann met the 19-year-old waiter Franz Westermeier, confiding to his diary "Once again this, once again love".. In 1975, when Mann's diaries were published, creating a national sensation in Germany, the retired Westermeier was tracked down in the United States: he was flattered to learn he had been the object of Mann's obsession, but also shocked at its depth.

Although Mann had always denied his novels had autobiographical components, the unsealing of his diaries revealing how consumed his life had been with unrequited and sublimated passion resulted in a reappraisal of his work. Thomas's son

During World War I, Mann supported

During World War I, Mann supported

''Stories of Three Decades''

(24 stories written from 1896 to 1922, trans. H. T. Lowe-Porter) *1988: ''Death in Venice and Other Stories'' (trans. David Luke). Includes: "Little Herr Friedemann"; "The Joker"; "The Road to the Churchyard"; "Gladius Dei"; "Tristan"; "Tonio Kroger"; "Death in Venice". *1997: ''Six Early Stories'' (trans. Peter Constantine). Includes: "A Vision: Prose Sketch"; "Fallen"; The Will to Happiness"; "Death"; "Avenged: Study for a Novella"; "Anecdote". *1998: ''Death in Venice and Other Tales'' (trans. Joachim Neugroschel). Includes: "The Will for Happiness"; "Little Herr Friedemann"; "Tobias Mindernickel"; "Little Lizzy"; "Gladius Dei"; "Tristan"; "The Starvelings: A Study"; "Tonio Kröger"; "The Wunderkind"; "Harsh Hour"; "The Blood of the Walsungs"; "Death in Venice". *1999: ''Death in Venice and Other Stories'' (trans. Jefferson Chase). Includes: "Tobias Mindernickel"; "Tristan"; "Tonio Kröger"; "The Child Prodigy"; "Hour of Hardship"; "Death in Venice"; "Man and Dog".

Thomas Mann's Profile on FamousAuthors.org

*

First prints of Thomas Mann. Collection Dr. Haack, Leipzig (Germany)

References to Thomas Mann in European historic newspapers

*

List of Works

* * Thomas Mann Collection. Yale Collection of German Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

TMI Research

b

Thomas Mann International

Cross-house research in the archive and library holdings of the network partners in Lübeck, Munich, Zurich and Los Angeles

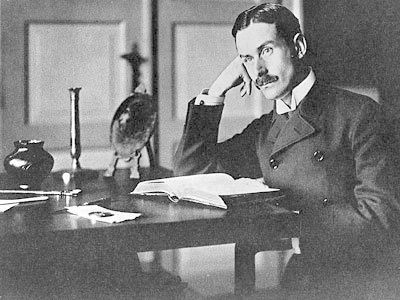

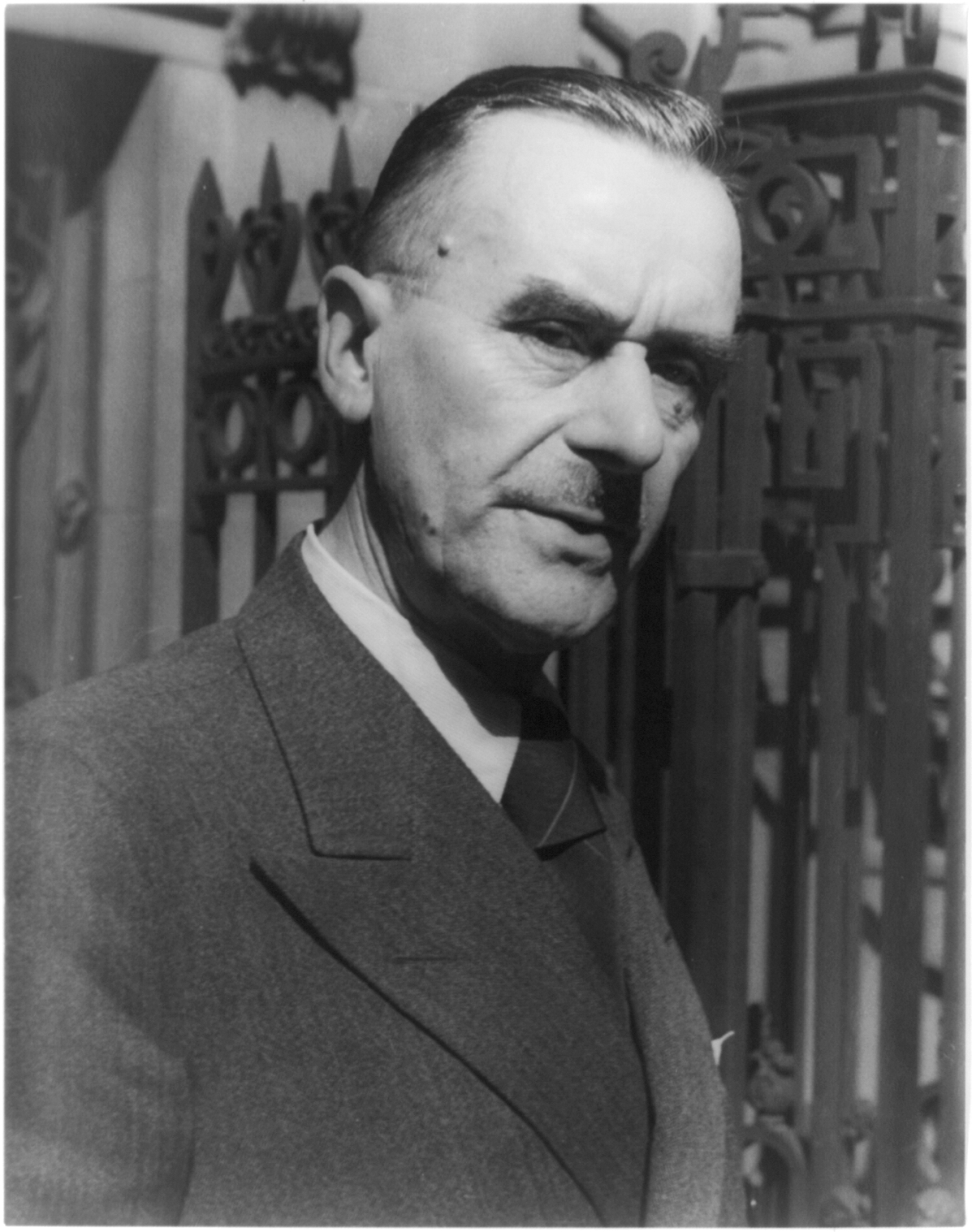

Paul Thomas Mann ( , ; ; 6 June 1875 – 12 August 1955) was a German novelist, short story writer, social critic, philanthropist, essayist, and the 1929 Nobel Prize in Literature laureate. His highly symbolic and ironic epic novels and novellas are noted for their insight into the psychology of the artist and the intellectual. His analysis and critique of the European and German soul used modernized versions of German and Biblical stories, as well as the ideas of

Paul Thomas Mann was born to a bourgeois family in

Paul Thomas Mann was born to a bourgeois family in

In 1912, he and his wife moved to a

In 1912, he and his wife moved to a

Salka Viertel , Jewish Women's Archive

Retrieved 19 November 2016. On 23 June 1944 Thomas Mann was naturalized as a citizen of the United States. The Manns lived in Los Angeles until 1952.

. In October 1940 he began monthly broadcasts, recorded in the U.S. and flown to London, where the BBC broadcast them to Germany on the Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (28 August 1749 – 22 March 1832) was a German poet, playwright, novelist, scientist, statesman, theatre director, and critic. His works include plays, poetry, literature, and aesthetic criticism, as well as t ...

, Friedrich Nietzsche

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (; or ; 15 October 1844 – 25 August 1900) was a German philosopher, prose poet, cultural critic, philologist, and composer whose work has exerted a profound influence on contemporary philosophy. He began his ...

, and Arthur Schopenhauer.

Mann was a member of the Hanseatic

The Hanseatic League (; gml, Hanse, , ; german: label=German language, Modern German, Deutsche Hanse) was a Middle Ages, medieval commercial and defensive confederation of merchant guilds and market towns in Central Europe, Central and Norther ...

Mann family

The Mann family ( , ; ) is the most famous German novelists' dynasty.

History

Originally the Manns were merchants, allegedly already in the 16th century in Nuremberg, documented since 1611 in Parchim, since 1713 in Rostock and since 1775 in ...

and portrayed his family and class in his first novel, ''Buddenbrooks

''Buddenbrooks'' () is a 1901 novel by Thomas Mann, chronicling the decline of a wealthy north German merchant family over the course of four generations, incidentally portraying the manner of life and mores of the Hanseatic bourgeoisie in th ...

''. His older brother was the radical writer Heinrich Mann

Luiz Heinrich Mann (; 27 March 1871 – 11 March 1950), best known as simply Heinrich Mann, was a German author known for his socio-political novels. From 1930 until 1933, he was president of the fine poetry division of the Prussian Academy ...

and three of Mann's six children – Erika Mann

Erika Julia Hedwig Mann (9 November 1905 – 27 August 1969) was a German actress and writer, daughter of the novelist Thomas Mann.

Erika lived a bohemian lifestyle in Berlin and became a critic of National Socialism. After Hitler came to power ...

, Klaus Mann

Klaus Heinrich Thomas Mann (18 November 1906 – 21 May 1949) was a German writer and dissident. He was the son of Thomas Mann, a nephew of Heinrich Mann and brother of Erika Mann, with whom he maintained a lifelong close relationship, and Golo ...

and Golo Mann

Golo Mann (born Angelus Gottfried Thomas Mann; 27 March 1909 – 7 April 1994) was a popular German historian and essayist. Having completed a doctorate in philosophy under Karl Jaspers at Heidelberg, in 1933 he fled Hitler's Germany. He followe ...

– also became significant German writers. When Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

came to power in 1933, Mann fled to Switzerland. When World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

broke out in 1939, he moved to the United States, then returned to Switzerland in 1952. Mann is one of the best-known exponents of the so-called ''Exilliteratur

German ''Exilliteratur'' (, ''exile literature'') is the name for works of German literature written in the German diaspora by refugee authors who fled from Nazi Germany, Nazi Austria, and the occupied territories between 1933 and 1945. These dis ...

'', German literature written in exile by those who opposed the Hitler regime.

Life

Paul Thomas Mann was born to a bourgeois family in

Paul Thomas Mann was born to a bourgeois family in Lübeck

Lübeck (; Low German also ), officially the Hanseatic City of Lübeck (german: Hansestadt Lübeck), is a city in Northern Germany. With around 217,000 inhabitants, Lübeck is the second-largest city on the German Baltic coast and in the state ...

, the second son of Thomas Johann Heinrich Mann (a senator and a grain merchant

The grain trade refers to the local and international trade in cereals and other food grains such as wheat, barley, maize, and rice. Grain is an important trade item because it is easily stored and transported with limited spoilage, unlike other ...

) and his wife Júlia da Silva Bruhns

Júlia da Silva Bruhns (August 14, 1851March 11, 1923) was a German-Brazilian writer. She was the wife of the Lübeck senator and grain merchant Johann Heinrich Mann, and also mother of writers Thomas Mann and Heinrich Mann.

Biography

Júlia ...

, a Brazilian woman of German and Portuguese ancestry, who emigrated to Germany with her family when she was seven years old. His mother was Roman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

* Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

* Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a let ...

but Mann was baptised into his father's Lutheran

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and Protestant Reformers, reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Cathol ...

religion. Mann's father died in 1891, and after that his trading firm was liquidated. The family subsequently moved to Munich

Munich ( ; german: München ; bar, Minga ) is the capital and most populous city of the German state of Bavaria. With a population of 1,558,395 inhabitants as of 31 July 2020, it is the third-largest city in Germany, after Berlin and Ha ...

. Mann first studied science at a Lübeck '' Gymnasium'' (secondary school), then attended the Ludwig Maximillians University of Munich as well as the Technical University of Munich

The Technical University of Munich (TUM or TU Munich; german: Technische Universität München) is a public research university in Munich, Germany. It specializes in engineering, technology, medicine, and applied and natural sciences.

Establis ...

, where, in preparation for a journalism career, he studied history, economics, art history and literature.

Mann lived in Munich from 1891 until 1933, with the exception of a year spent in Palestrina

Palestrina (ancient ''Praeneste''; grc, Πραίνεστος, ''Prainestos'') is a modern Italian city and ''comune'' (municipality) with a population of about 22,000, in Lazio, about east of Rome. It is connected to the latter by the Via Pre ...

, Italy, with his elder brother, the novelist Heinrich Heinrich may refer to:

People

* Heinrich (given name), a given name (including a list of people with the name)

* Heinrich (surname), a surname (including a list of people with the name)

*Hetty (given name), a given name (including a list of peo ...

. Thomas worked at the South German Fire Insurance Company in 1894–95. His career as a writer began when he wrote for the magazine ''Simplicissimus

:''Simplicissimus is also a name for the 1668 novel Simplicius Simplicissimus and its protagonist.''

''Simplicissimus'' () was a satirical German weekly magazine, headquartered in Munich, and founded by Albert Langen in April 1896. It continue ...

''. Mann's first short story, "Little Mr Friedemann" (''Der Kleine Herr Friedemann''), was published in 1898.

In 1905, Mann married Katia Pringsheim, who came from a wealthy, secular Jewish industrialist family. She later joined the Lutheran

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and Protestant Reformers, reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Cathol ...

church. The couple had six children.

Pre-war and Second World War period

In 1912, he and his wife moved to a

In 1912, he and his wife moved to a sanatorium

A sanatorium (from Latin '' sānāre'' 'to heal, make healthy'), also sanitarium or sanitorium, are antiquated names for specialised hospitals, for the treatment of specific diseases, related ailments and convalescence. Sanatoriums are often ...

in Davos, Switzerland, which was to inspire his 1924 novel ''The Magic Mountain

''The Magic Mountain'' (german: Der Zauberberg, links=no, ) is a novel by Thomas Mann, first published in German in November 1924. It is widely considered to be one of the most influential works of twentieth-century German literature.

Mann s ...

''. He was also appalled by the risk of international confrontation between Germany and France, following the Agadir Crisis

The Agadir Crisis, Agadir Incident, or Second Moroccan Crisis was a brief crisis sparked by the deployment of a substantial force of French troops in the interior of Morocco in April 1911 and the deployment of the German gunboat to Agadir, a ...

in Morocco, and later by the outbreak of the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

.

In 1929, Mann had a cottage built in the fishing village of Nidden, Memel Territory

Memel, a name derived from the Couronian-Latvian ''memelis, mimelis, mēms'' for "mute, silent", may refer to:

*Memel, East Prussia, Germany, now Klaipėda, Lithuania

**Memelburg, ( Klaipėda Castle), the ''Ordensburg'' in Memel, a castle built in ...

(now Nida Nida or NIDA may refer to:

People

* Nida Allam (born 1993), American politician

* Nida Fazli (1938–2016), Indian Hindi and Urdu poet and lyricist

* Nida Eliz Üstündağ (born 1996), Turkish female swimmer

* Eugene Nida (1914–2011), American l ...

, Lithuania) on the Curonian Spit

The Curonian (Courish) Spit ( lt, Kuršių nerija; russian: Ку́ршская коса́ (Kurshskaya kosa); german: Kurische Nehrung, ; lv, Kuršu kāpas) is a long, thin, curved sand-dune spit that separates the Curonian Lagoon from the Balti ...

, where there was a German art colony and where he spent the summers of 1930–1932 working on ''Joseph and His Brothers

''Joseph and His Brothers'' (''Joseph und seine Brüder'') is a four-part novel by Thomas Mann, written over the course of 16 years. Mann retells the familiar stories of Genesis, from Jacob to Joseph (chapters 27–50), setting it in the hi ...

''. Today the cottage is a cultural center dedicated to him, with a small memorial exhibition.

In 1933, while travelling in the South of France

Southern France, also known as the South of France or colloquially in French as , is a defined geographical area consisting of the regions of France that border the Atlantic Ocean south of the Marais Poitevin,Louis Papy, ''Le midi atlantique'', A ...

, Mann heard from his eldest children, Klaus and Erika in Munich, that it would not be safe for him to return to Germany. The family (except these two children) emigrated to Küsnacht

Küsnacht is a municipality in the district of Meilen in the canton of Zurich in Switzerland.

History

Küsnacht is first mentioned in 1188 as ''de Cussenacho''.

Earliest findings of settlement date back to the stone age. There are also finding ...

, near Zürich

, neighboring_municipalities = Adliswil, Dübendorf, Fällanden, Kilchberg, Maur, Oberengstringen, Opfikon, Regensdorf, Rümlang, Schlieren, Stallikon, Uitikon, Urdorf, Wallisellen, Zollikon

, twintowns = Kunming, San Francisco

Zürich ...

, Switzerland, but received Czechoslovak

Czechoslovak may refer to:

*A demonym or adjective pertaining to Czechoslovakia (1918–93)

**First Czechoslovak Republic (1918–38)

**Second Czechoslovak Republic (1938–39)

**Third Czechoslovak Republic (1948–60)

**Fourth Czechoslovak Repub ...

citizenship and a passport in 1936. In 1939, following the German occupation of Czechoslovakia, he emigrated to the United States. He moved to Princeton, New Jersey

Princeton is a municipality with a borough form of government in Mercer County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey. It was established on January 1, 2013, through the consolidation of the Borough of Princeton and Princeton Township, both of whi ...

, where he lived on 65 Stockton Street and began to teach at Princeton University

Princeton University is a private research university in Princeton, New Jersey. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and one of the ...

. In 1942, the Mann family moved to 1550 San Remo Drive in the Pacific Palisades neighborhood of Los Angeles, California. The Manns were prominent members of the German expatriate community of Los Angeles, and would frequently meet other emigres at the house of Salka and Bertold Viertel in Santa Monica, and at the Villa Aurora

The Villa Aurora at 520 Paseo Miramar is located in Pacific Palisades, Los Angeles and has been used as an artists' residence since 1995. It is the former home of the German-Jewish author Lion Feuchtwanger and his wife Marta. The Feuchtwanger ...

, the home of fellow German exile Lion Feuchtwanger

Lion Feuchtwanger (; 7 July 1884 – 21 December 1958) was a German Jewish novelist and playwright. A prominent figure in the literary world of Weimar Germany, he influenced contemporaries including playwright Bertolt Brecht.

Feuchtwanger's J ...

.Jewish Women's ArchiveSalka Viertel , Jewish Women's Archive

Retrieved 19 November 2016. On 23 June 1944 Thomas Mann was naturalized as a citizen of the United States. The Manns lived in Los Angeles until 1952.

Anti-Nazi broadcasts

The outbreak of World War II on 1 September 1939, prompted Mann to offer anti-Nazi speeches (in German) to the German people via theBBC #REDIRECT BBC #REDIRECT BBC

Here i going to introduce about the best teacher of my life b BALAJI sir. He is the precious gift that I got befor 2yrs . How has helped and thought all the concept and made my success in the 10th board exam. ...

...longwave

In radio, longwave, long wave or long-wave, and commonly abbreviated LW, refers to parts of the radio spectrum with wavelengths longer than what was originally called the medium-wave broadcasting band. The term is historic, dating from the e ...

band. In these eight-minute addresses, Mann condemned Hitler and his "paladins" as crude philistines completely out of touch with European culture. In one noted speech he said, "The war is horrible, but it has the advantage of keeping Hitler from making speeches about culture."

Mann was one of the few publicly active opponents of Nazism among German expatriates in the U.S. In a BBC broadcast of 30 December 1945, Mann expressed understanding as to why those peoples that had suffered from the Nazi regime would embrace the idea of German collective guilt

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ger ...

. But he also thought that many enemies might now have second thoughts about "revenge." And he expressed regret that such judgment cannot be based on the individual.

Last years

With the start of the Cold War he was increasingly frustrated by rising McCarthyism. As a 'suspected communist', he was required to testify to the House Un-American Activities Committee, where he was termed "one of the world's foremost apologists for Stalin and company." He was listed by HUAC as being "affiliated with various peace organizations or Communist fronts." Being in his own words a non-communist rather than an anti-communist, Mann openly opposed the allegations: "As an American citizen of German birth I finally testify that I am painfully familiar with certain political trends. Spiritual intolerance, political inquisitions, and declining legal security, and all this in the name of an alleged 'state of emergency.' ... That is how it started in Germany." As Mann joined protests against the jailing of the

With the start of the Cold War he was increasingly frustrated by rising McCarthyism. As a 'suspected communist', he was required to testify to the House Un-American Activities Committee, where he was termed "one of the world's foremost apologists for Stalin and company." He was listed by HUAC as being "affiliated with various peace organizations or Communist fronts." Being in his own words a non-communist rather than an anti-communist, Mann openly opposed the allegations: "As an American citizen of German birth I finally testify that I am painfully familiar with certain political trends. Spiritual intolerance, political inquisitions, and declining legal security, and all this in the name of an alleged 'state of emergency.' ... That is how it started in Germany." As Mann joined protests against the jailing of the Hollywood Ten

The Hollywood blacklist was an entertainment industry blacklist, broader than just Hollywood, put in effect in the mid-20th century in the United States during the early years of the Cold War. The blacklist involved the practice of denying empl ...

and the firing of schoolteachers suspected of being Communists, he found "the media had been closed to him". Finally he was forced to quit his position as Consultant in Germanic Literature at the Library of Congress and in 1952 he returned to Europe, to live in Kilchberg, near Zürich, Switzerland. He never again lived in Germany, though he regularly traveled there. His most important German visit was in 1949, at the 200th birthday of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (28 August 1749 – 22 March 1832) was a German poet, playwright, novelist, scientist, statesman, theatre director, and critic. His works include plays, poetry, literature, and aesthetic criticism, as well as t ...

, attending celebrations in Frankfurt am Main

Frankfurt, officially Frankfurt am Main (; Hessian: , "Frank ford on the Main"), is the most populous city in the German state of Hesse. Its 791,000 inhabitants as of 2022 make it the fifth-most populous city in Germany. Located on its na ...

and Weimar

Weimar is a city in the state of Thuringia, Germany. It is located in Central Germany between Erfurt in the west and Jena in the east, approximately southwest of Leipzig, north of Nuremberg and west of Dresden. Together with the neighbouri ...

, as a statement that German culture extended beyond the new political borders.

Death

Following his 80th birthday, Mann went on vacation to Noordwij in the Netherlands. On 18 July 1955, he began to experience pain and unilateral swelling in his left leg. The condition ofthrombophlebitis

Thrombophlebitis is a phlebitis (inflammation of a vein) related to a thrombus (blood clot). When it occurs repeatedly in different locations, it is known as thrombophlebitis migrans ( migratory thrombophlebitis).

Signs and symptoms

The following ...

was diagnosed by Dr. Mulders from Leiden and confirmed by Dr. Wilhelm Löffler. Mann was transported to a Zürich hospital, but soon developed a state of shock

Shock may refer to:

Common uses Collective noun

*Shock, a historic commercial term for a group of 60, see English numerals#Special names

* Stook, or shock of grain, stacked sheaves

Healthcare

* Shock (circulatory), circulatory medical emergen ...

. On 12 August 1955, he died.Bollinger A. he death of Thomas Mann: consequence of erroneous angiologic diagnosis? '' Wiener Medizinische Wochenschrift'', 1999; 149(2–4):30–32. Postmortem, his condition was found to have been misdiagnosed. The pathologic diagnosis, made by Christoph Hedinger, showed he had actually suffered a perforated iliac artery aneurysm

An aneurysm is an outward bulging, likened to a bubble or balloon, caused by a localized, abnormal, weak spot on a blood vessel wall. Aneurysms may be a result of a hereditary condition or an acquired disease. Aneurysms can also be a nidus ( ...

resulting in a retroperitoneal

The retroperitoneal space (retroperitoneum) is the anatomical space (sometimes a potential space) behind (''retro'') the peritoneum. It has no specific delineating anatomical structures. Organs are retroperitoneal if they have peritoneum on thei ...

hematoma, compression and thrombosis

Thrombosis (from Ancient Greek "clotting") is the formation of a blood clot inside a blood vessel, obstructing the flow of blood through the circulatory system. When a blood vessel (a vein or an artery) is injured, the body uses platelets (t ...

of the iliac vein. (At that time, lifesaving vascular surgery had not been developed.) On 16 August 1955, Thomas Mann was buried in Village Cemetery, Kilchberg, Zürich, Switzerland.

Legacy

Mann's work influenced many later authors, such asYukio Mishima

, born , was a Japanese author, poet, playwright, actor, model, Shintoist, nationalist, and founder of the , an unarmed civilian militia. Mishima is considered one of the most important Japanese authors of the 20th century. He was considered fo ...

. Joseph Campbell also stated in an interview with Bill Moyers that Mann was one of his mentors. Many institutions are named in his honour, for instance the Thomas Mann Gymnasium of Budapest

Budapest (, ; ) is the capital and most populous city of Hungary. It is the ninth-largest city in the European Union by population within city limits and the second-largest city on the Danube river; the city has an estimated population ...

.

Career

Blanche Knopf

Blanche Wolf Knopf (July 30, 1894 – June 4, 1966) was the president of Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., and wife of publisher Alfred A. Knopf Sr., with whom she established the firm in 1915. Blanche traveled the world seeking new authors and was especial ...

of Alfred A. Knopf

Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. () is an American publishing house that was founded by Alfred A. Knopf Sr. and Blanche Knopf in 1915. Blanche and Alfred traveled abroad regularly and were known for publishing European, Asian, and Latin American writers in ...

publishing house was introduced to Mann by H.L. Mencken while on a book-buying trip to Europe. Knopf became Mann's American publisher, and Blanche hired scholar Helen Tracy Lowe-Porter

Helen Tracy Lowe-Porter (June 15, 1876 – April 26, 1963) was an American translator and writer, best known for translating almost all of the works of Thomas Mann for their first publication in English.

Personal life

Helen Tracy Porter was the ...

to translate Mann's books in 1924. Lowe-Porter subsequently translated Mann's complete works. Blanche Knopf continued to look after Mann. After ''Buddenbrooks'' proved successful in its first year, they sent him an unexpected bonus. Later in the 1930s, Blanche helped arrange for Mann and his family to emigrate to America.

Nobel Prize in Literature

Mann was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1929, after he had been nominated byAnders Österling

Anders Österling (13 April 1884 – 13 December 1981) was a Swedish poet, critic and translator. In 1919 he was elected as a member of the Swedish Academy when he was 35 years old and served the Academy for 62 years, longer than any other memb ...

, member of the Swedish Academy, principally in recognition of his popular achievement with the epic ''Buddenbrooks

''Buddenbrooks'' () is a 1901 novel by Thomas Mann, chronicling the decline of a wealthy north German merchant family over the course of four generations, incidentally portraying the manner of life and mores of the Hanseatic bourgeoisie in th ...

'' (1901), ''The Magic Mountain

''The Magic Mountain'' (german: Der Zauberberg, links=no, ) is a novel by Thomas Mann, first published in German in November 1924. It is widely considered to be one of the most influential works of twentieth-century German literature.

Mann s ...

'' (''Der Zauberberg'', 1924) and his numerous short stories. (Due to the personal taste of an influential committee member, only '' Buddenbrooks'' was cited at any great length.) Based on Mann's own family, ''Buddenbrooks'' relates the decline of a merchant family in Lübeck over the course of four generations. ''The Magic Mountain'' (''Der Zauberberg'', 1924) follows an engineering student who, planning to visit his tubercular cousin at a Swiss sanatorium

A sanatorium (from Latin '' sānāre'' 'to heal, make healthy'), also sanitarium or sanitorium, are antiquated names for specialised hospitals, for the treatment of specific diseases, related ailments and convalescence. Sanatoriums are often ...

for only three weeks, finds his departure from the sanatorium delayed. During that time, he confronts medicine and the way it looks at the body and encounters a variety of characters, who play out ideological conflicts and discontents of contemporary European civilization. The tetralogy ''Joseph and His Brothers'' is an epic novel written over a period of sixteen years, and is one of the largest and most significant works in Mann's oeuvre. Later, other novels included '' Lotte in Weimar'' (1939), in which Mann returned to the world of Goethe's novel ''The Sorrows of Young Werther

''The Sorrows of Young Werther'' (; german: Die Leiden des jungen Werthers) is a 1774 epistolary novel by Johann Wolfgang Goethe, which appeared as a revised edition in 1787. It was one of the main novels in the '' Sturm und Drang'' period in Ge ...

'' (1774); '' Doctor Faustus'' (1947), the story of the fictitious composer Adrian Leverkühn and the corruption of German culture

The culture of Germany has been shaped by major intellectual and popular currents in Europe, both religious and secular. Historically, Germany has been called ''Das Land der Dichter und Denker'' (the country of poets and thinkers). German cult ...

in the years before and during World War II; and '' Confessions of Felix Krull'' (''Bekenntnisse des Hochstaplers Felix Krull'', 1954), which was unfinished at Mann's death. These later works prompted two members of the Swedish Academy to nominate Mann for the Nobel Prize in Literature a second time, in 1948.

Influence

Throughout his Dostoevsky essay, he finds parallels between the Russian and the sufferings ofFriedrich Nietzsche

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (; or ; 15 October 1844 – 25 August 1900) was a German philosopher, prose poet, cultural critic, philologist, and composer whose work has exerted a profound influence on contemporary philosophy. He began his ...

. Speaking of Nietzsche, he says: "his personal feelings initiate him into those of the criminal... in general all creative originality, all artist nature in the broadest sense of the word, does the same. It was the French painter and sculptor Degas

Edgar Degas (, ; born Hilaire-Germain-Edgar De Gas, ; 19 July 183427 September 1917) was a French Impressionist artist famous for his pastel drawings and oil paintings.

Degas also produced bronze sculptures, prints and drawings. Degas is espec ...

who said that an artist must approach his work in the spirit of the criminal about to commit a crime." Nietzsche's influence on Mann runs deep in his work, especially in Nietzsche's views on decay and the proposed fundamental connection between sickness and creativity. Mann held that disease is not to be regarded as wholly negative. In his essay on Dostoevsky we find: "but after all and above all it depends on who is diseased, who mad, who epileptic or paralytic: an average dull-witted man, in whose illness any intellectual or cultural aspect is non-existent; or a Nietzsche or Dostoyevsky. In their case something comes out in illness that is more important and conductive to life and growth than any medical guaranteed health or sanity... in other words: certain conquests made by the soul and the mind are impossible without disease, madness, crime of the spirit."

Sexuality

Mann's diaries reveal his struggles with his homosexuality, which found reflection in his works, most prominently through the obsession of the elderly Aschenbach for the 14-year-old Polish boy Tadzio in the novella ''

Mann's diaries reveal his struggles with his homosexuality, which found reflection in his works, most prominently through the obsession of the elderly Aschenbach for the 14-year-old Polish boy Tadzio in the novella ''Death in Venice

''Death in Venice ''(German: ''Der Tod in Venedig'') is a novella by German author Thomas Mann, published in 1912. It presents an ennobled writer who visits Venice and is liberated, uplifted, and then increasingly obsessed by the sight of a Poli ...

'' (''Der Tod in Venedig'', 1912).

Anthony Heilbut

Anthony Heilbut (born November 22, 1940) is an American writer, and record producer of gospel music. He is noted for his biography of Thomas Mann, and has also won a Grammy Award.

Life

Anthony Heilbut, the son of German Jewish refugees Bertha and ...

's biography ''Thomas Mann: Eros and Literature'' (1997) uncovered the centrality of Mann's sexuality to his oeuvre. Gilbert Adair

Gilbert Adair (29 December 19448 December 2011) was a Scottish novelist, poet, film critic, and journalist.Stuart Jeffries and Ronald BerganObituary: Gilbert Adair ''The Guardian'', 9 December 2011. He was critically most famous for the "fiend ...

's work ''The Real Tadzio'' (2001) describes how, in the summer of 1911, Mann had stayed at the Grand Hôtel des Bains on the Lido

Lido may refer to:

Geography Africa

* Lido, a district in the city of Fez, Morocco

Asia

* Lido, an area in Chaoyang District, Beijing

* Lido, a cinema theater in Siam Square shopping area in Bangkok

* Lido City, a resort in West Java owned by MN ...

of Venice with his wife and brother, when he became enraptured by the angelic figure of Władysław (Władzio) Moes, a 10-year-old Polish boy ( the real Tadzio). Mann's diary records his attraction to his own 13-year-old son, "Eissi" – Klaus Mann: "Klaus to whom recently I feel very drawn" (22 June). In the background conversations about man-to-man eroticism take place; a long letter is written to Carl Maria Weber on this topic, while the diary reveals: "In love with Klaus during these days" (5 June). "Eissi, who enchants me right now" (11 July). "Delight over Eissi, who in his bath is terribly handsome. Find it very natural that I am in love with my son ... Eissi lay reading in bed with his brown torso naked, which disconcerted me" (25 July). "I heard noise in the boys' room and surprised Eissi completely naked in front of Golo's bed acting foolish. Strong impression of his premasculine, gleaming body. Disquiet" (17 October 1920).

Klaus Mann

Klaus Heinrich Thomas Mann (18 November 1906 – 21 May 1949) was a German writer and dissident. He was the son of Thomas Mann, a nephew of Heinrich Mann and brother of Erika Mann, with whom he maintained a lifelong close relationship, and Golo ...

dealt openly from the beginning with his own homosexuality in his literary work and open lifestyle, referring critically to his father's " sublimation" in his diary. On the other hand, Thomas's daughter Erika Mann

Erika Julia Hedwig Mann (9 November 1905 – 27 August 1969) was a German actress and writer, daughter of the novelist Thomas Mann.

Erika lived a bohemian lifestyle in Berlin and became a critic of National Socialism. After Hitler came to power ...

and his son Golo Mann

Golo Mann (born Angelus Gottfried Thomas Mann; 27 March 1909 – 7 April 1994) was a popular German historian and essayist. Having completed a doctorate in philosophy under Karl Jaspers at Heidelberg, in 1933 he fled Hitler's Germany. He followe ...

came out only later in their lives.

Cultural references

''The Magic Mountain''

Several literary and other works make reference to Mann's book ''The Magic Mountain

''The Magic Mountain'' (german: Der Zauberberg, links=no, ) is a novel by Thomas Mann, first published in German in November 1924. It is widely considered to be one of the most influential works of twentieth-century German literature.

Mann s ...

'', including:

*Frederic Tuten

Frederic Tuten (born December 2, 1936) is an American novelist, short story writer and essayist. He has written five novels – ''The Adventures of Mao on the Long March'' (1971), ''Tallien: A Brief Romance'' (1988), ''Tintin in the New World: A ...

's 1993 novel ''Tintin in the New World'' features many characters (such as Clavdia Chauchat, Mynheer Peeperkorn and others) from ''The Magic Mountain'' interacting with Tintin

Tintin or Tin Tin may refer to:

''The Adventures of Tintin''

* ''The Adventures of Tintin'', a comics series by Belgian cartoonist Hergé

** Tintin (character), a fictional character in the series

** ''The Adventures of Tintin'' (film), 2011, ...

in Peru.

*Andrew Crumey

Andrew Crumey (born 1961) is a novelist and former literary editor of the Edinburgh newspaper ''Scotland on Sunday''.

Life and career

Crumey was born in Kirkintilloch, north of Glasgow, Scotland. He graduated with First Class Honours from the ...

's novel '' Mobius Dick'' (2004) imagines an alternative universe where an author named Behring has written novels resembling Mann's. These include a version of ''The Magic Mountain'' with Erwin Schrödinger

Erwin Rudolf Josef Alexander Schrödinger (, ; ; 12 August 1887 – 4 January 1961), sometimes written as or , was a Nobel Prize-winning Austrian physicist with Irish citizenship who developed a number of fundamental results in quantum theo ...

in place of Castorp.

*Haruki Murakami

is a Japanese writer. His novels, essays, and short stories have been bestsellers in Japan and internationally, with his work translated into 50 languages and having sold millions of copies outside Japan. He has received numerous awards for his ...

's novel '' Norwegian Wood'' (1987), in which the main character is criticized for reading ''The Magic Mountain'' while visiting a friend in a sanatorium.

*The song "Magic Mountain" by the band Blonde Redhead

Blonde Redhead is an American alternative rock band composed of Kazu Makino (vocals, keys/rhythm guitar) and twin brothers Simone and Amedeo Pace (drums/keys and lead guitar/bass/keys/vocals, respectively) that formed in New York City in 1993. ...

.

*The painting ''Magic Mountain (after Thomas Mann)'' by Christiaan Tonnis (1987). "The Magic Mountain" is also a chapter in Tonnis's 2006 book ''Krankheit als Symbol'' ("Illness as a Symbol").

*The 1941 film '' 49th Parallel'', in which the character Philip Armstrong Scott unknowingly praises Mann's work to an escaped World War II Nazi U-boat

U-boats were naval submarines operated by Germany, particularly in the First and Second World Wars. Although at times they were efficient fleet weapons against enemy naval warships, they were most effectively used in an economic warfare ro ...

commander, who later responds by burning Scott's copy of ''The Magic Mountain''.

*In Ken Kesey

Ken Elton Kesey (September 17, 1935 – November 10, 2001) was an American novelist, essayist and countercultural figure. He considered himself a link between the Beat Generation of the 1950s and the hippies of the 1960s.

Kesey was born in ...

's novel ''Sometimes a Great Notion

''Sometimes a Great Notion'' is the second novel by American author Ken Kesey, published in 1964. While ''One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest'' (1962) is more famous, many critics consider ''Sometimes a Great Notion'' Kesey's magnum opus. The story i ...

'' (1964), character Indian Jenny purchases a Thomas Mann novel and tries to find out "... just where was this mountain full of magic..." (p. 578).

*Hayao Miyazaki

is a Japanese animator, director, producer, screenwriter, author, and manga artist. A co-founder of Studio Ghibli, he has attained international acclaim as a masterful storyteller and creator of Japanese animated feature films, and is widel ...

's 2013 film ''The Wind Rises

is a 2013 Japanese animated historical drama film written and directed by Hayao Miyazaki, animated by Studio Ghibli for the Nippon Television Network, Dentsu, Hakuhodo DY Media Partners, Walt Disney Japan, Mitsubishi, Toho and KDDI. It was rele ...

'', in which an unnamed German man at a mountain resort invokes the novel as cover for furtively condemning the rapidly arming Hitler and Hirohito regimes. After he flees to escape the Japanese secret police, the protagonist, who fears his own mail is being read, refers to him as the novel's Mr. Castorp. The film is partly based on another Japanese novel, set like ''The Magic Mountain'' in a tuberculosis sanatorium.

*Father John Misty

Joshua Michael Tillman (born May 3, 1981), better known by his stage name Father John Misty, is an American musician, singer, songwriter, and record producer. He has also performed and released studio albums under the name J. Tillman.

Maintainin ...

's 2017 album '' Pure Comedy'' contains a song titled "So I'm Growing Old on Magic Mountain", in which a man, near death, reflects on the passing of time and the disappearance of his Dionysian youth in homage to the themes in Mann's novel.

*Viktor Frankl

Viktor Emil Frankl (26 March 1905 – 2 September 1997)

was an Austrian psychiatrist who founded logotherapy, a school of psychotherapy that describes a search for a life's meaning as the central human motivational force. Logotherapy is pa ...

's book ''Man's Search for Meaning

''Man's Search for Meaning'' is a 1946 book by Viktor Frankl chronicling his experiences as a prisoner in Nazi concentration camps during World War II, and describing his psychotherapeutic method, which involved identifying a purpose in life to ...

'' relates the "time-experience" of Holocaust prisoners to TB patients in ''The Magic Mountain'': "How paradoxical was our time-experience! In this connection we are reminded of Thomas Mann's ''The Magic Mountain'', which contains some very pointed psychological remarks. Mann studies the spiritual development of people who are in an analogous psychological position, i.e., tuberculosis patients in a sanatorium who also know no date for their release. They experience a similar existence—without a future and without a goal."

''Death in Venice''

Many literary and other works make reference to ''Death in Venice'', including: *Luchino Visconti

Luchino Visconti di Modrone, Count of Lonate Pozzolo (; 2 November 1906 – 17 March 1976) was an Italian filmmaker, stage director, and screenwriter. A major figure of Italian art and culture in the mid-20th century, Visconti was one of the ...

's 1971 film version of Mann's novella.

*Benjamin Britten

Edward Benjamin Britten, Baron Britten (22 November 1913 – 4 December 1976, aged 63) was an English composer, conductor, and pianist. He was a central figure of 20th-century British music, with a range of works including opera, other ...

's 1973 operatic adaptation in two acts of Mann's novella.

*Woody Allen

Heywood "Woody" Allen (born Allan Stewart Konigsberg; November 30, 1935) is an American film director, writer, actor, and comedian whose career spans more than six decades and multiple Academy Award-winning films. He began his career writing ...

's film ''Annie Hall

''Annie Hall'' is a 1977 American satirical romantic comedy-drama film directed by Woody Allen from a screenplay written by him and Marshall Brickman, and produced by Allen's manager, Charles H. Joffe. The film stars Allen as Alvy Singer, w ...

'' (1977) refers to the novella.

*Joseph Heller

Joseph Heller (May 1, 1923 – December 12, 1999) was an American author of novels, short stories, plays, and screenplays. His best-known work is the 1961 novel ''Catch-22'', a satire on war and bureaucracy, whose title has become a synonym for ...

's 1994 novel, '' Closing Time'', which makes several references to Thomas Mann and ''Death in Venice''.

*Alexander McCall Smith

Alexander "Sandy" McCall Smith, CBE, FRSE (born 24 August 1948), is a British writer. He was raised in Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) and formerly Professor of Medical Law at the University of Edinburgh. He became an expert on medical law an ...

's novel ''Portuguese Irregular Verbs

''Portuguese Irregular Verbs'' is a short comic novel by Alexander McCall Smith, and the first of McCall Smith's series of novels featuring Professor Dr von Igelfeld. It was first published in 1997. Some consider the book to be a series of con ...

'' (1997) has a final chapter entitled "Death in Venice" and refers to Thomas Mann by name in that chapter.

*Philip Roth

Philip Milton Roth (March 19, 1933 – May 22, 2018) was an American novelist and short story writer.

Roth's fiction—often set in his birthplace of Newark, New Jersey—is known for its intensely autobiographical character, for philosophicall ...

's novel ''The Human Stain

''The Human Stain'' is a novel by Philip Roth, published May 5, 2000. The book is set in Western Massachusetts in the late 1990s. It is narrated by 65-year-old author Nathan Zuckerman, who appears in several earlier Roth novels, and who also fig ...

'' (2000).

*Rufus Wainwright

Rufus McGarrigle Wainwright (born July 22, 1973) is a Canadian-American singer, songwriter, and composer. He has recorded 10 studio albums and numerous tracks on compilations and film soundtracks. He has also written two classical operas and set ...

's 2001 song "Grey Gardens", which mentions the character Tadzio in the refrain.

*Alan Bennett

Alan Bennett (born 9 May 1934) is an English actor, author, playwright and screenwriter. Over his distinguished entertainment career he has received numerous awards and honours including two BAFTA Awards, four Laurence Olivier Awards, and two ...

's 2009 play '' The Habit of Art'', in which Benjamin Britten

Edward Benjamin Britten, Baron Britten (22 November 1913 – 4 December 1976, aged 63) was an English composer, conductor, and pianist. He was a central figure of 20th-century British music, with a range of works including opera, other ...

is imagined paying a visit to W. H. Auden

Wystan Hugh Auden (; 21 February 1907 – 29 September 1973) was a British-American poet. Auden's poetry was noted for its stylistic and technical achievement, its engagement with politics, morals, love, and religion, and its variety in ...

about the possibility of Auden writing the libretto for Britten's opera ''Death in Venice

''Death in Venice ''(German: ''Der Tod in Venedig'') is a novella by German author Thomas Mann, published in 1912. It presents an ennobled writer who visits Venice and is liberated, uplifted, and then increasingly obsessed by the sight of a Poli ...

''.

* David Rakoff's essay "Shrimp", which appears in his 2010 collection ''Half Empty'', makes a humorous comparison between Mann's Aschenbach and E. B. White

Elwyn Brooks White (July 11, 1899 – October 1, 1985) was an American writer. He was the author of several highly popular books for children, including ''Stuart Little'' (1945), ''Charlotte's Web'' (1952), and '' The Trumpet of the Swan'' ...

's Stuart Little.

* Two main characters in ''Me and Earl and the Dying Girl

''Me and Earl and the Dying Girl'' is a 2012 debut novel written by Jesse Andrews. The novel was released in hardcover by Amulet Books on March 1, 2012, and in paperback on May 7, 2013.

Plot

Greg Gaines is a senior at Benson High School i ...

'' make a spoof film titled ''Death in Tennis''.

Other

*''Hayavadana'' (1972), a play byGirish Karnad

Girish Karnad (19 May 1938 – 10 June 2019) was an Indian actor, film director, Kannada writer, playwright and a Jnanpith awardee, who predominantly worked in South Indian cinema and Bollywood. His rise as a playwright in the 1960s marked the ...

was based on a theme drawn from ''The Transposed Heads'' and employed the folk theatre form of ''Yakshagana

Yakshagaana is a traditional theatre, developed in Dakshina Kannada, Udupi, Uttara Kannada, Shimoga and western parts of Chikmagalur districts, in the state of Karnataka and in Kasaragod district in Kerala that combines dance, music, dialogue, ...

''. A German version of the play, was directed by Vijaya Mehta

Vijaya Mehta (born 4 November 1934), is a noted Indian Marathi film and theatre director and also an actor in many films from the Parallel Cinema. She is a founder member of Mumbai-based theatre group, Rangayan with playwright Vijay Tendulka ...

as part of the repertoire of the Deutsches National Theatre, Weimar. ''Frontline

Front line refers to the forward-most forces on a battlefield.

Front line, front lines or variants may also refer to:

Books and publications

* ''Front Lines'' (novel), young adult historical novel by American author Michael Grant

* ''Frontlines ...

'', Vol. 16, No. 03, 30 January – 12 February 1999. A staged musical version of ''The Transposed Heads,'' adapted by Julie Taymor

Julie Taymor (born December 15, 1952) is an American director and writer of theater, opera and film. Her stage adaptation of ''The Lion King'' debuted in 1997, and received eleven Tony Award nominations, with Taymor receiving Tony Awards for Best ...

and Sidney Goldfarb, with music by Elliot Goldenthal

Elliot Goldenthal (born May 2, 1954) is an American composer of contemporary classical music and film and theatrical scores. A student of Aaron Copland and John Corigliano, he is best known for his distinctive style and ability to blend various ...

, was produced at the American Music Theater Festival in Philadelphia and the Lincoln Center

Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts (also simply known as Lincoln Center) is a complex of buildings in the Lincoln Square neighborhood on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. It has thirty indoor and outdoor facilities and is host to 5 milli ...

in New York in 1988.

*Mann's 1896 short story "Disillusionment" is the basis for the Leiber and Stoller

Lyricist Jerome Leiber (April 25, 1933 – August 22, 2011) and composer Michael Stoller (born March 13, 1933) were American songwriting and record producing partners. They found success as the writers of such crossover hit songs as " Hound Dog" ( ...

song "Is That All There Is?

"Is That All There Is?", a song written by American songwriting team Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller during the 1960s, became a hit for American singer Peggy Lee and an award winner from her album of the same title in November 1969. The song wa ...

", famously recorded in 1969 by Peggy Lee.

*In a 1994 essay, Umberto Eco

Umberto Eco (5 January 1932 – 19 February 2016) was an Italian medievalist, philosopher, semiotician, novelist, cultural critic, and political and social commentator. In English, he is best known for his popular 1980 novel ''The Name of th ...

suggests that the media discuss "Whether reading Thomas Mann gives one erections" as an alternative to "Whether Joyce is boring".

*Mann's life in California during World War II, including his relationships with his older brother Heinrich Mann

Luiz Heinrich Mann (; 27 March 1871 – 11 March 1950), best known as simply Heinrich Mann, was a German author known for his socio-political novels. From 1930 until 1933, he was president of the fine poetry division of the Prussian Academy ...

and Bertolt Brecht is a subject of Christopher Hampton's play ''Tales from Hollywood''.

*Colm Tóibín

Colm Tóibín (, approximately ; born 30 May 1955) is an Irish novelist, short story writer, essayist, journalist, critic, playwright and poet.

His first novel, '' The South'', was published in 1990. '' The Blackwater Lightship'' was shortlis ...

's 2021 fictionalised biography ''The Magician'' is a portrait of Mann in the context of his family and political events.

Political views

During World War I, Mann supported

During World War I, Mann supported Kaiser Wilhelm II

, house = Hohenzollern

, father = Frederick III, German Emperor

, mother = Victoria, Princess Royal

, religion = Lutheranism (Prussian United)

, signature = Wilhelm II, German Emperor Signature-.svg

Wilhelm II (Friedrich Wilhelm Viktor ...

's conservatism, attacked liberalism and supported the war effort, calling the Great War "a purification, a liberation, an enormous hope". Yet in ''Von Deutscher Republik'' (1923), as a semi-official spokesman for parliamentary democracy, Mann called upon German intellectuals to support the new Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic (german: link=no, Weimarer Republik ), officially named the German Reich, was the government of Germany from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a constitutional federal republic for the first time in history; hence it is ...

. He also gave a lecture at the Beethovensaal in Berlin on 13 October 1922, which appeared in '' Die neue Rundschau'' in November 1922, in which he developed his eccentric defence of the Republic based on extensive close readings of Novalis

Georg Philipp Friedrich Freiherr von Hardenberg (2 May 1772 – 25 March 1801), pen name Novalis (), was a German polymath who was a writer, philosopher, poet, aristocrat and mystic. He is regarded as an idiosyncratic and influential figure of ...

and Walt Whitman

Walter Whitman (; May 31, 1819 – March 26, 1892) was an American poet, essayist and journalist. A humanist, he was a part of the transition between transcendentalism and realism, incorporating both views in his works. Whitman is among ...

. Thereafter, his political views gradually shifted toward liberal left and democratic principles.

Mann initially gave his support to the left-liberal German Democratic Party

The German Democratic Party (, or DDP) was a center-left liberal party in the Weimar Republic. Along with the German People's Party (, or DVP), it represented political liberalism in Germany between 1918 and 1933. It was formed in 1918 from the ...

before shifting further left and urging unity behind the Social Democrats

Social democracy is a political, social, and economic philosophy within socialism that supports political and economic democracy. As a policy regime, it is described by academics as advocating economic and social interventions to promote so ...

. In 1930 he gave a public address in Berlin titled "An Appeal to Reason", in which he strongly denounced Nazism

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) i ...

and encouraged resistance by the working class. This was followed by numerous essays and lectures in which he attacked the Nazis

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in N ...

. At the same time, he expressed increasing sympathy for socialist ideas. When the Nazis came to power in 1933, Mann and his wife were on holiday in Switzerland. Due to his strident denunciations of Nazi policies, his son Klaus advised him not to return. In contrast to those of his brother Heinrich and his son Klaus, Mann's books were not among those burnt publicly by Hitler's regime in May 1933, possibly since he had been the Nobel laureate in literature for 1929. In 1936, the Nazi government officially revoked his German citizenship.

During the war, Mann made a series of anti-Nazi radio-speeches, published as '' Listen, Germany!'' in 1943. They were recorded on tape in the United States and then sent to the United Kingdom, where the British Broadcasting Corporation #REDIRECT BBC #REDIRECT BBC #REDIRECT BBC

Here i going to introduce about the best teacher of my life b BALAJI sir. He is the precious gift that I got befor 2yrs . How has helped and thought all the concept and made my success in the 10th board ex ...

transmitted them, hoping to reach German listeners.

Views on Russian communism and Nazi-fascism

Mann expressed his belief in the collection of letters written in exile, ''Listen, Germany!'' (''Deutsche Hörer!''), that equating Russian communism with Nazi-fascism on the basis that both aretotalitarian

Totalitarianism is a form of government and a political system that prohibits all opposition parties, outlaws individual and group opposition to the state and its claims, and exercises an extremely high if not complete degree of control and reg ...

systems was either superficial or insincere in showing a preference for fascism. He clarified this view during a German press interview in July 1949, declaring that he was not a communist, but that communism at least had some relation to ideals of humanity and of a better future. He said that the transition of the communist revolution into an autocratic regime was a tragedy while Nazism was only "devilish nihilism".

Literary works

Play

1905: '' Fiorenza''Prose sketch

1893: "Vision"Short stories

*1894: "Gefallen" *1896: "The Will to Happiness" *1896: "Disillusionment" ("Enttäuschung") *1896: "Little Herr Friedemann

"Little Herr Friedemann" () is a short story by Thomas Mann. It initially appeared in 1896 in '' Die neue Rundschau'', and later appeared in 1898 in an anthology of Mann's short stories entitled collectively as ''Der kleine Herr Friedemann''.

"L ...

" ("Der kleine Herr Friedemann")

*1897: "Death" ("Der Tod")

*1897: " The Clown" ("Der Bajazzo")

*1897: "The Dilettante"

*1898: " Tobias Mindernickel"

*1899: "The Wardrobe" ("Der Kleiderschrank")

*1900: "Luischen" ("Little Lizzy") – written in 1897

*1900: "The Road to the Churchyard" ("Der Weg zum Friedhof")

*1903: "The Hungry"

*1903: "The Child Prodigy" ("Das Wunderkind")

*1904: "A Gleam"

*1904: "At the Prophet's"

*1905: "A Weary Hour"

*1907: "Railway Accident"

*1908: "Anecdote" ("Anekdote")

*1911: "The Fight between Jappe and the Do Escobar"

Novels

*1901: ''Buddenbrooks

''Buddenbrooks'' () is a 1901 novel by Thomas Mann, chronicling the decline of a wealthy north German merchant family over the course of four generations, incidentally portraying the manner of life and mores of the Hanseatic bourgeoisie in th ...

'' (''Buddenbrooks – Verfall einer Familie'')

*1909: ''Royal Highness

Royal Highness is a style used to address or refer to some members of royal families, usually princes or princesses. Monarchs and their consorts are usually styled ''Majesty''.

When used as a direct form of address, spoken or written, it t ...

'' (''Königliche Hoheit'')

*1924: ''The Magic Mountain

''The Magic Mountain'' (german: Der Zauberberg, links=no, ) is a novel by Thomas Mann, first published in German in November 1924. It is widely considered to be one of the most influential works of twentieth-century German literature.

Mann s ...

'' (''Der Zauberberg'')

*1939: '' Lotte in Weimar: The Beloved Returns''

*1947: '' Doctor Faustus'' (''Doktor Faustus'')

*1951: ''The Holy Sinner

''The Holy Sinner'' () is a German novel written by Thomas Mann. Published in 1951, it is based on the medieval verse epic ''Gregorius'' written by the German Minnesinger Hartmann von Aue (c. 1165–1210). The book explores a subject that fasci ...

'' (''Der Erwählte'')

Series

''Felix Krull'' #''Felix Krull'' (''Bekenntnisse des Hochstaplers Felix Krull'') (written in 1911, published in 1922) #'' Confessions of Felix Krull'', (''Bekenntnisse des Hochstaplers Felix Krull. Der Memoiren erster Teil''; expanded from 1911 short story), unfinished (1954) ''Joseph and His Brothers

''Joseph and His Brothers'' (''Joseph und seine Brüder'') is a four-part novel by Thomas Mann, written over the course of 16 years. Mann retells the familiar stories of Genesis, from Jacob to Joseph (chapters 27–50), setting it in the hi ...

'' (''Joseph und seine Brüder'') (1933–43)

#''The Stories of Jacob'' (''Die Geschichten Jaakobs'') (1933)

#''Young Joseph'' (''Der junge Joseph'') (1934)

#''Joseph in Egypt'' (''Joseph in Ägypten'') (1936)

#''Joseph the Provider'' (''Joseph, der Ernährer'') (1943)

Novellas

*1902: ''Gladius Dei'' *1903: ''Tristan

Tristan (Latin/ Brythonic: ''Drustanus''; cy, Trystan), also known as Tristram or Tristain and similar names, is the hero of the legend of Tristan and Iseult. In the legend, he is tasked with escorting the Irish princess Iseult to we ...

''

*1903: ''Tonio Kröger

''Tonio Kröger'' () is a novella by Thomas Mann, written early in 1901, when he was 25. It was first published in 1903. A. A. Knopf in New York published the first American edition in 1936, translated by Helen Tracy Lowe-Porter.

Plot summary

T ...

''

*1905: '' The Blood of the Walsungs'' (''Wӓlsungenblut'') (2nd Edition: 1921)

*1912: ''Death in Venice

''Death in Venice ''(German: ''Der Tod in Venedig'') is a novella by German author Thomas Mann, published in 1912. It presents an ennobled writer who visits Venice and is liberated, uplifted, and then increasingly obsessed by the sight of a Poli ...

'' (''Der Tod in Venedig'')

*1918: ''A Man and His Dog

''A Man and His Dog'' (''Un Homme et Son Chien'') is a 2008 French film directed by French director Francis Huster, starring Jean-Paul Belmondo, based on the 1952 film '' Umberto D.'' directed by Vittorio De Sica, and written by Cesare Zavattini. ...

'' (''Herr und Hund''), sometimes translated as ''Bashan and I''

*1925: '' Disorder and Early Sorrow'' (''Unordnung und frühes Leid'')

*1930: ''Mario and the Magician

''Mario and the Magician'' (german: Mario und der Zauberer) is a novella written by German author Thomas Mann in 1929.

Plot summary

The narrator describes a trip by his family to the fictional seaside town of Torre di Venere, Italy (a fictional ...

'' (''Mario und der Zauberer'')

*1940: '' The Transposed Heads'' (''Die vertauschten Köpfe – Eine indische Legende'')

*1944: '' The Tables of the Law'' – a commissioned work (''Das Gesetz'')

*1954: '' The Black Swan'' (''Die Betrogene: Erzählung'')

Essays

*1915: "Frederick and the Great Coalition" ("Friedrich und die große Koalition") *1918: "Reflections of an Unpolitical Man" ("Betrachtungen eines Unpolitischen") *1922: "The German Republic" ("Von deutscher Republik") *1930: "A Sketch of My Life" ("Lebensabriß") – autobiographical *1950: "Michelangelo according to his poems" ("Michelangelo in seinen Dichtungen") *1947: ''Essays of Three Decades'', translated from the German by H. T. Lowe-Porter. st American ed. New York, A. A. Knopf, 1947. Reprinted as Vintage book, K55, New York, Vintage Books, 1957. *"Nietzsche's Philosophy in the Light of Recent History"Miscellaneous

*1937: "The Problem of Freedom" ("Das Problem der Freiheit"), speech *1938: '' The Coming Victory of Democracy'' – collection of lectures *1938: "This Peace" ("Dieser Friede"), pamphlet *1938: "Schopenhauer", philosophy and music theory on Arthur Schopenhauer *1940: "This War!" ("Dieser Krieg!"), article *1943: '' Listen, Germany!'' (Deutsche Hörer!) – collection of lettersCompilations in English

*1922''Stories of Three Decades''

(24 stories written from 1896 to 1922, trans. H. T. Lowe-Porter) *1988: ''Death in Venice and Other Stories'' (trans. David Luke). Includes: "Little Herr Friedemann"; "The Joker"; "The Road to the Churchyard"; "Gladius Dei"; "Tristan"; "Tonio Kroger"; "Death in Venice". *1997: ''Six Early Stories'' (trans. Peter Constantine). Includes: "A Vision: Prose Sketch"; "Fallen"; The Will to Happiness"; "Death"; "Avenged: Study for a Novella"; "Anecdote". *1998: ''Death in Venice and Other Tales'' (trans. Joachim Neugroschel). Includes: "The Will for Happiness"; "Little Herr Friedemann"; "Tobias Mindernickel"; "Little Lizzy"; "Gladius Dei"; "Tristan"; "The Starvelings: A Study"; "Tonio Kröger"; "The Wunderkind"; "Harsh Hour"; "The Blood of the Walsungs"; "Death in Venice". *1999: ''Death in Venice and Other Stories'' (trans. Jefferson Chase). Includes: "Tobias Mindernickel"; "Tristan"; "Tonio Kröger"; "The Child Prodigy"; "Hour of Hardship"; "Death in Venice"; "Man and Dog".

Research

Databases

TMI Research

The metadatabase TMI-Research brings together archival materials and library holdings of the network "Thomas Mann International". The network was founded in 2017 by the five houses Buddenbrookhaus/Heinrich-und-Thomas-Mann-Zentrum (Lübeck), the Monacensia im Hildebrandhaus (Munich), the Thomas Mann Archive of the ETH Zurich (Zurich/Switzerland), theThomas Mann House

The Thomas Mann House (in German: ''Thomas-Mann-Haus'') in Pacific Palisades, Los Angeles, in the U.S. state of California is the former residence of Nobel Prize laureate Thomas Mann, who lived there with his family during his exile from 1942 un ...

(Los Angeles/USA) and the Thomo Manno kultūros centras/Thomas Mann Culture Centre (Nida/Lithuania). The houses stand for the main stations of Thomas Mann's life. The platform, which is hosted by ETH Zurich, allows researches in the collections of the network partners across all houses. The database is freely accessible and contains over 165,000 records on letters, original editions, photographs, monographs and essays on Thomas Mann and the Mann family. Further links take you to the respective source databases with contact options and further information.

See also

* Erich Heller (esp. ''s.v.'' "Writings on Thomas Mann", "Life in letters") *Patrician (post-Roman Europe)

Patricianship, the quality of belonging to a patriciate, began in the ancient world, where cities such as Ancient Rome had a social class of patrician families, whose members were initially the only people allowed to exercise many political f ...

* Terence James Reed

Terence James Reed, FBA (born 1937), known professionally as Jim Reed, is a scholar of German literature. He was Taylor Professor of the German Language and Literature at the University of Oxford from 1989 to 2004.

Born in 1937, Reed completed h ...

's ''Thomas Mann: The Uses of Tradition'' (1974)

Notes

Further reading

* Von Gronicka, André. 1970. ''Thomas Mann: Profile and Perspectives with Two Unpublished Letters and a Chronological List of Important Events'' St ed.ed. New York: Random House. * Hamilton, Nigel (1978), ''The Brothers Mann: The Lives ofHeinrich Heinrich may refer to:

People

* Heinrich (given name), a given name (including a list of people with the name)

* Heinrich (surname), a surname (including a list of people with the name)

*Hetty (given name), a given name (including a list of peo ...

and Thomas Mann'', Yale University Press,

* Heller, Erich, ''Thomas Mann: The Ironic German'', Cambridge University Press, (1981),

* Martin Mauthner, ''German Writers in French Exile 1933–1940'' (London, 2007).

* David Horton, ''Thomas Mann in English: A Study in Literary Translation'' (London, New Delhi, New York, Sydney, 2013)

* Colm Tóibín

Colm Tóibín (, approximately ; born 30 May 1955) is an Irish novelist, short story writer, essayist, journalist, critic, playwright and poet.

His first novel, '' The South'', was published in 1990. '' The Blackwater Lightship'' was shortlis ...

, ''The Magician'', Viking, 2021, . A novel based on Mann's life.

External links

Thomas Mann's Profile on FamousAuthors.org

*

First prints of Thomas Mann. Collection Dr. Haack, Leipzig (Germany)

References to Thomas Mann in European historic newspapers

*

List of Works

* * Thomas Mann Collection. Yale Collection of German Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

TMI Research

b

Thomas Mann International

Cross-house research in the archive and library holdings of the network partners in Lübeck, Munich, Zurich and Los Angeles

Electronic editions

* * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Mann, Thomas 1875 births 1955 deaths 19th-century German novelists 19th-century German short story writers 20th-century German novelists 20th-century German short story writers Bisexual men Bisexual writers Emigrants from Nazi Germany to Switzerland Exilliteratur writers German anti-fascists German autobiographers German emigrants to the United States German essayists German Lutherans German male novelists German male short story writers German Nobel laureates German people of Brazilian descent German people of Portuguese descent LGBT academics LGBT Nobel laureates LGBT writers from Germany Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich alumni Modernist writers Nobel laureates in Literature People of the German Empire People of the Weimar Republic Philosophical pessimists Princeton University faculty Recipients of the Pour le Mérite (civil class) Social critics Technical University of Munich alumni Writers from LübeckThomas

Thomas may refer to:

People

* List of people with given name Thomas

* Thomas (name)

* Thomas (surname)

* Saint Thomas (disambiguation)

* Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) Italian Dominican friar, philosopher, and Doctor of the Church

* Thomas the A ...

Thomas

Thomas may refer to:

People

* List of people with given name Thomas

* Thomas (name)

* Thomas (surname)

* Saint Thomas (disambiguation)

* Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) Italian Dominican friar, philosopher, and Doctor of the Church

* Thomas the A ...

Members of the American Academy of Arts and Letters