Gideon Algernon Mantell on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Gideon Algernon Mantell MRCS FRS (3 February 1790 – 10 November 1852) was a British

He returned to Lewes, and immediately formed a partnership with his former master, James Moore. In the wake of the

He returned to Lewes, and immediately formed a partnership with his former master, James Moore. In the wake of the

Inspired by

Inspired by

On 10 November 1852, Mantell took an overdose of opium and later lapsed into a coma. He died that afternoon. His

On 10 November 1852, Mantell took an overdose of opium and later lapsed into a coma. He died that afternoon. His

''The Fossils of the South Downs''

Royal

''The Geological Age of Reptiles''

In Jameson's Edinburgh Philosophical Journal, 1831, Vol. 11, pp. 81–85

''A Narrative of the Visit of their most Gracious Majesties William IV and Queen Adelaide, to the Ancient Borough of Lewes, on the 22nd of October 1830''

London: Lupton Relfe, 1831.

''The Geology of the South-East of England''

''Thoughts on a Pebble''

1836

8th edition, 1849

*''The Wonders of Geology'' or, a familiar exposition of geological phenomena: being the substance of a course of lectures delivered at Brighton. 2 vols, London, 1838.

vol 1:

428p, frontis & 4 plates

vol 2:

pages 429795 plus appendix, glossary and other material, coloured frontis & 10 coloured plates, most drawn by his wife. Mantell's most extensive work.

''The Medals of Creation''

2 vols, 1844. *''A Day's Ramble in and about the Antient Town of Lewes''. London: Henry G. Bohn, 1846.

''Thoughts on Animalcules''

small 4to, 144p, 12 coloured plates. London: Murray, 1846. 1850 title: ''The invisible world revealed by the microscope or, thoughts on animalcules''.

''Geological Excursions round the Isle of Wight and along the adjacent Coast of Dorsetshire''

1847. *

''Petrifactions and their teachings''

1851.

A History of Dinosaur Hunting and ReconstructionSchedule of Mantell related tours and events in and around Lewes and Brighton

Biography at Strange Science.net

Mantell and Wilds

by the Friends of West Norwood Cemetery

(1844) First Lessons in Geology and in the Study of Organic Remains by Gideon Mantell

The journal of Gideon Mantell, Hathi TrustScanned copy of ''The Fossils of the South Downs'' (1822)

{{DEFAULTSORT:Mantell, Gideon 1790 births 1852 deaths English geologists English palaeontologists 19th-century English medical doctors English obstetricians Fellows of the Royal Society People from Lewes Burials at West Norwood Cemetery Wollaston Medal winners Royal Medal winners Drug-related suicides in England

obstetrician

Obstetrics is the field of study concentrated on pregnancy, childbirth and the postpartum period. As a medical specialty, obstetrics is combined with gynecology under the discipline known as obstetrics and gynecology (OB/GYN), which is a surgic ...

, geologist

A geologist is a scientist who studies the solid, liquid, and gaseous matter that constitutes Earth and other terrestrial planets, as well as the processes that shape them. Geologists usually study geology, earth science, or geophysics, althou ...

and palaeontologist

Paleontology (), also spelled palaeontology or palæontology, is the scientific study of life that existed prior to, and sometimes including, the start of the Holocene epoch (roughly 11,700 years before present). It includes the study of foss ...

. His attempts to reconstruct the structure and life of ''Iguanodon

''Iguanodon'' ( ; meaning ' iguana-tooth'), named in 1825, is a genus of iguanodontian dinosaur. While many species have been classified in the genus ''Iguanodon'', dating from the late Jurassic Period to the early Cretaceous Period of Asia, ...

'' began the scientific study of dinosaurs: in 1822 he was responsible for the discovery (and the eventual identification) of the first fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

teeth, and later much of the skeleton, of ''Iguanodon''. Mantell's work on the Cretaceous

The Cretaceous ( ) is a geological period that lasted from about 145 to 66 million years ago (Mya). It is the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era, as well as the longest. At around 79 million years, it is the longest geological period of ...

of southern England was also important.

Early life and medical career

Mantell was born inLewes

Lewes () is the county town of East Sussex, England. It is the police and judicial centre for all of Sussex and is home to Sussex Police, East Sussex Fire & Rescue Service, Lewes Crown Court and HMP Lewes. The civil parish is the centre of t ...

, Sussex as the fifth-born child of Thomas Mantell, a shoemaker, and Sarah Austen. He was raised in a small cottage in St. Mary's Lane with his two sisters and four brothers. As a youth, he showed a particular interest in the field of geology. He explored pits and quarries in the surrounding areas, discovering ammonite

Ammonoids are a group of extinct marine mollusc animals in the subclass Ammonoidea of the class Cephalopoda. These molluscs, commonly referred to as ammonites, are more closely related to living coleoids (i.e., octopuses, squid and cuttlefis ...

s, shells of sea urchin

Sea urchins () are spiny, globular echinoderms in the class Echinoidea. About 950 species of sea urchin live on the seabed of every ocean and inhabit every depth zone from the intertidal seashore down to . The spherical, hard shells (tests) o ...

s, fish bones, coral

Corals are marine invertebrates within the class Anthozoa of the phylum Cnidaria. They typically form compact colonies of many identical individual polyps. Coral species include the important reef builders that inhabit tropical oceans and se ...

, and worn-out remains of dead animals. The Mantell children could not study at local grammar schools because the elder Mantell was a follower of the Methodist church

Methodism, also called the Methodist movement, is a group of historically related denominations of Protestant Christianity whose origins, doctrine and practice derive from the life and teachings of John Wesley. George Whitefield and John's ...

and the 12 free schools were reserved for children who had been brought up in the Anglican

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of t ...

faith. As a result, Gideon was educated at a dame school

Dame schools were small, privately run schools for young children that emerged in the British Isles and its colonies during the early modern period. These schools were taught by a “school dame,” a local woman who would educate children f ...

in St. Mary's Lane, and learned basic reading and writing from an old woman. After the death of his teacher, Mantell was schooled by John Button, a philosophically radical Whig who shared similar political beliefs with Mantell's father. Mantell spent two years with Button, before being sent to his uncle, a Baptist minister, in Swindon

Swindon () is a town and unitary authority with borough status in Wiltshire, England. As of the 2021 Census, the population of Swindon was 201,669, making it the largest town in the county. The Swindon unitary authority area had a population ...

, for a period of private study.

Mantell returned to Lewes at age 15. With the help of a local Whig party leader, Mantell secured an apprenticeship

Apprenticeship is a system for training a new generation of practitioners of a trade or profession with on-the-job training and often some accompanying study (classroom work and reading). Apprenticeships can also enable practitioners to gain a ...

with a local surgeon named James Moore. He served as an apprentice to Moore in Lewes for a period of five years, in which he took care of Mantell's dining, lodging and medical issues. Mantell's early apprenticeship duties included cleaning vials, as well as separating and arranging drugs

A drug is any chemical substance that causes a change in an organism's physiology or psychology when consumed. Drugs are typically distinguished from food and substances that provide nutritional support. Consumption of drugs can be via inhalati ...

. Soon, he learned how to make pills and other pharmaceutical products

A medication (also called medicament, medicine, pharmaceutical drug, medicinal drug or simply drug) is a drug used to diagnose, cure, treat, or prevent disease. Drug therapy (pharmacotherapy) is an important part of the medical field and rel ...

. He delivered Moore's medicines, kept his accounts, wrote out bills and extracted teeth from his patients.Dean, p. 14. On 11 July 1807, Thomas Mantell died at the age of 57. He left his son some money for his future studies. As his time in apprenticeship began to wind down, he began to anticipate his medical education. He began to teach himself human anatomy

The human body is the structure of a human being. It is composed of many different types of cells that together create tissues and subsequently organ systems. They ensure homeostasis and the viability of the human body.

It comprises a hea ...

, and he ultimately detailed his new-found knowledge in a volume entitled ''The Anatomy of the Bones, and the Circulation of Blood'', which contained dozens of detailed drawings of fetal and adult skeletal features. Soon, Mantell began his formal medical education in London. He received his diploma as a Member of the Royal College of Surgeons

The Royal College of Surgeons is an ancient college (a form of corporation) established in England to regulate the activity of surgeons. Derivative organisations survive in many present and former members of the Commonwealth. These organisations ...

in 1811. Four days later, he received a certificate from the Lying-in Charity for Married Women at Their Own Habitations that allowed him to act in midwifery

Midwifery is the health science and health profession that deals with pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period (including care of the newborn), in addition to the sexual and reproductive health of women throughout their lives. In many ...

duties.

He returned to Lewes, and immediately formed a partnership with his former master, James Moore. In the wake of the

He returned to Lewes, and immediately formed a partnership with his former master, James Moore. In the wake of the cholera

Cholera is an infection of the small intestine by some strains of the bacterium '' Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea that lasts a few days. Vomiting an ...

, typhoid

Typhoid fever, also known as typhoid, is a disease caused by ''Salmonella'' serotype Typhi bacteria. Symptoms vary from mild to severe, and usually begin six to 30 days after exposure. Often there is a gradual onset of a high fever over several d ...

and smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

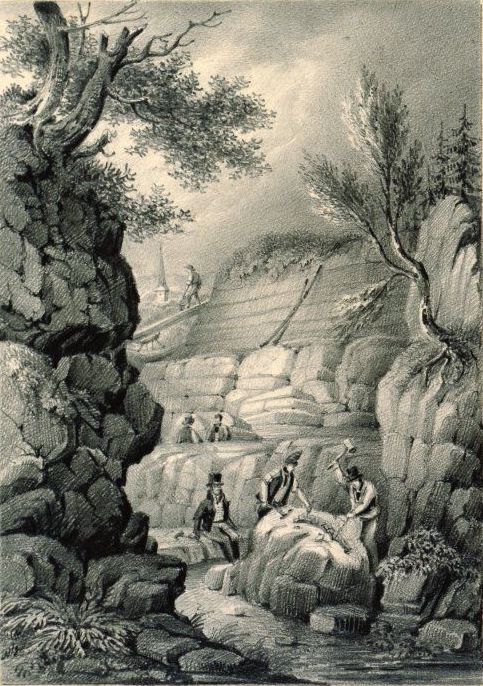

epidemics, Mantell found himself quite busy attending to more than 50 patients a day and delivering between 200 and 300 babies a year. As he later recalled, he would have to stay up for "six or seven nights in succession" due to his overwhelming doctoral duties. He was also able to increase his practice's profits from £250 to £750 a year. Although mainly occupied with running his busy country medical practice, he spent his little free time pursuing his passion, geology, often working into the early hours of the morning, identifying fossil specimens he found at the marl pits in Hamsey

Hamsey is a civil parish in the Lewes District of East Sussex, England. The parish covers a large area () and consists of the villages of Hamsey, Offham and Cooksbridge. The main centres of population in the parish are now Offham and Cooksbridge. ...

. In 1813, Mantell began to correspond with James Sowerby

James Sowerby (21 March 1757 – 25 October 1822) was an English naturalist, illustrator and mineralogist. Contributions to published works, such as ''A Specimen of the Botany of New Holland'' or ''English Botany'', include his detailed and app ...

. Sowerby, a naturalist and illustrator who catalogued fossil shells, received from Mantell many fossilised specimens. In appreciation for the specimens Mantell had provided, Sowerby named one of the species ''Ammonites mantelli''. On 7 December, Mantell was elected as a fellow of the Linnean Society of London

The Linnean Society of London is a learned society dedicated to the study and dissemination of information concerning natural history, evolution, and taxonomy. It possesses several important biological specimen, manuscript and literature coll ...

. Two years later, he published his first paper, on the characteristics of the fossils found in the Lewes area.Dean, p. 31.

In 1816, he married Mary Ann Woodhouse, the 20-year-old daughter of one of his former patients who had died three years earlier. Since she was not 21 and still technically a minor under English law, she had to obtain permission from her mother and a special licence to marry Mantell. After obtaining consent and the licence, she married Mantell on 4 May at St. Marylebone Church. That year, he purchased his own medical practice and took up an appointment at the Royal Artillery Hospital, at Ringmer

Ringmer is a village and civil parish in the Lewes District of East Sussex, England.OS Explorer map Eastbourne and Beachy Head Scale: 1:25 000. Publisher:Ordnance Survey – Southampton B2 edition. Publishing Date:2009. The village is east of ...

, Lewes.

Geological research

Inspired by

Inspired by Mary Anning

Mary Anning (21 May 1799 – 9 March 1847) was an English fossil collector, dealer, and palaeontologist who became known around the world for the discoveries she made in Jurassic marine fossil beds in the cliffs along the English Channel ...

's sensational discovery of a fossilised animal resembling a huge crocodile

Crocodiles (family Crocodylidae) or true crocodiles are large semiaquatic reptiles that live throughout the tropics in Africa, Asia, the Americas and Australia. The term crocodile is sometimes used even more loosely to include all extant me ...

(later identified as an ichthyosaur

Ichthyosaurs (Ancient Greek for "fish lizard" – and ) are large extinct marine reptiles. Ichthyosaurs belong to the order known as Ichthyosauria or Ichthyopterygia ('fish flippers' – a designation introduced by Sir Richard Owen in 1842, alt ...

) at Lyme Regis

Lyme Regis is a town in west Dorset, England, west of Dorchester and east of Exeter. Sometimes dubbed the "Pearl of Dorset", it lies by the English Channel at the Dorset– Devon border. It has noted fossils in cliffs and beaches on the He ...

in Dorset, Mantell became passionately interested in the study of the fossilised animals and plants found in his area. The fossils he had collected from the region, near The Weald in Sussex, were from the chalk downlands covering the county. The chalk is part of the Upper Cretaceous

The Cretaceous ( ) is a geological period that lasted from about 145 to 66 million years ago (Mya). It is the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era, as well as the longest. At around 79 million years, it is the longest geological period of ...

System

A system is a group of interacting or interrelated elements that act according to a set of rules to form a unified whole. A system, surrounded and influenced by its environment, is described by its boundaries, structure and purpose and express ...

and the fossils it contains are marine

Marine is an adjective meaning of or pertaining to the sea or ocean.

Marine or marines may refer to:

Ocean

* Maritime (disambiguation)

* Marine art

* Marine biology

* Marine debris

* Marine habitats

* Marine life

* Marine pollution

Military ...

in origin. But by 1819, Mantell had begun acquiring fossils from a quarry, at Whitemans Green, near Cuckfield

Cuckfield ( ) is a village and civil parish in the Mid Sussex District of West Sussex, England, on the southern slopes of the Weald. It lies south of London, north of Brighton, and east northeast of the county town of Chichester. Nearby tow ...

. These included the remains of terrestrial

Terrestrial refers to things related to land or the planet Earth.

Terrestrial may also refer to:

* Terrestrial animal, an animal that lives on land opposed to living in water, or sometimes an animal that lives on or near the ground, as opposed to ...

and freshwater

Fresh water or freshwater is any naturally occurring liquid or frozen water containing low concentrations of dissolved salts and other total dissolved solids. Although the term specifically excludes seawater and brackish water, it does incl ...

ecosystem

An ecosystem (or ecological system) consists of all the organisms and the physical environment with which they interact. These biotic and abiotic components are linked together through nutrient cycles and energy flows. Energy enters the syst ...

s, at a time when all the known fossil remains from Cretaceous England, hitherto, were marine in origin. He named the new strata the ''Strata of Tilgate

Tilgate is one of 14 neighbourhoods within the town of Crawley in West Sussex, England. The area contains a mixture of privately developed housing, self-build groups and ex-council housing. It is bordered by the districts of Furnace Green to th ...

Forest'', after an historical wooded area and it was later shown to belong to the Lower Cretaceous

Lower may refer to:

* Lower (surname)

* Lower Township, New Jersey

*Lower Receiver (firearms)

* Lower Wick Gloucestershire, England

See also

*Nizhny

Nizhny (russian: Ни́жний; masculine), Nizhnyaya (; feminine), or Nizhneye (russian: Н� ...

.

By 1820, he had started to find very large bones at Cuckfield, even larger than those discovered by William Buckland

William Buckland DD, FRS (12 March 1784 – 14 August 1856) was an English theologian who became Dean of Westminster. He was also a geologist and palaeontologist.

Buckland wrote the first full account of a fossil dinosaur, which he named ' ...

, at Stonesfield in Oxfordshire. Then, in 1822, shortly before finishing his first book (''The Fossils of South Downs''), his wife found several large teeth (although some historians contend that they were in fact discovered by himself), the origin of which he could not ascertain. In 1821 Mantell planned his next book on the geology of Sussex. It was an immediate success with two hundred subscribers including a letter from King George IV

George IV (George Augustus Frederick; 12 August 1762 – 26 June 1830) was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and King of Hanover from the death of his father, King George III, on 29 January 1820, until his own death ten y ...

at Carlton House Palace which read ''"His majesty is pleased to command that his name should be placed at the head of the subscription list for four copies."''

How the king heard of Mantell is unknown, but Mantell's response is. Galvanised and encouraged, Mantell showed the teeth to other scientists but they were dismissed as belonging to a fish or mammal

Mammals () are a group of vertebrate animals constituting the class Mammalia (), characterized by the presence of mammary glands which in females produce milk for feeding (nursing) their young, a neocortex (a region of the brain), fur ...

and from a more recent rock layer than the other Tilgate Forest fossils. The eminent French anatomist

Anatomy () is the branch of biology concerned with the study of the structure of organisms and their parts. Anatomy is a branch of natural science that deals with the structural organization of living things. It is an old science, having it ...

, Georges Cuvier

Jean Léopold Nicolas Frédéric, Baron Cuvier (; 23 August 1769 – 13 May 1832), known as Georges Cuvier, was a French naturalist and zoologist, sometimes referred to as the "founding father of paleontology". Cuvier was a major figure in na ...

, identified the teeth as those of a rhinoceros

A rhinoceros (; ; ), commonly abbreviated to rhino, is a member of any of the five extant species (or numerous extinct species) of odd-toed ungulates in the family Rhinocerotidae. (It can also refer to a member of any of the extinct specie ...

.

Although according to Charles Lyell

Sir Charles Lyell, 1st Baronet, (14 November 1797 – 22 February 1875) was a Scottish geologist who demonstrated the power of known natural causes in explaining the earth's history. He is best known as the author of ''Principles of Geolo ...

, Cuvier made this statement after a late party and apparently had some doubts when reconsidering the matter when he awoke, fresh in the morning. ''"The next morning he told me that he was confident that it was something quite different."'' Strangely, this change of opinion did not make it back to Britain where Mantell was mocked for his error. Mantell was still convinced that the teeth had come from the Mesozoic

The Mesozoic Era ( ), also called the Age of Reptiles, the Age of Conifers, and colloquially as the Age of the Dinosaurs is the second-to-last era of Earth's geological history, lasting from about , comprising the Triassic, Jurassic and Cretace ...

strata and finally recognised that they resembled those of the iguana, but were twenty times larger. He surmised that the owner of the remains must have been at least 60 feet (18 metres) in length.

Recognition

He tried in vain to convince his peers that the fossils were from Mesozoic strata, by carefully studying rock layers.William Buckland

William Buckland DD, FRS (12 March 1784 – 14 August 1856) was an English theologian who became Dean of Westminster. He was also a geologist and palaeontologist.

Buckland wrote the first full account of a fossil dinosaur, which he named ' ...

famously disputed Mantell's assertion, by claiming that the teeth were of fish.

When it was proved Mantell was correct in 1825, the only question was what to call his new reptile. His original name was "Iguana-saurus" but he then received a letter from William Daniel Conybeare

William Daniel Conybeare FRS (7 June 178712 August 1857), dean of Llandaff, was an English geologist, palaeontologist and clergyman. He is probably best known for his ground-breaking work on fossils and excavation in the 1820s, including import ...

, ''"Your discovery of the analogy between the Iguana and the fossil teeth is very interesting but the name you propose will hardly do, because it is equally applicable to the recent iguana. Iguanoides or Iguanodon would be better."'' Mantell took this advice to heart and called his creature ''Iguanodon

''Iguanodon'' ( ; meaning ' iguana-tooth'), named in 1825, is a genus of iguanodontian dinosaur. While many species have been classified in the genus ''Iguanodon'', dating from the late Jurassic Period to the early Cretaceous Period of Asia, ...

''.

Years later, Mantell had acquired enough fossil evidence to show that the dinosaur's forelimbs were much shorter than its hind legs, therefore proving they were not built like a mammal as claimed by Sir Richard Owen

Sir Richard Owen (20 July 1804 – 18 December 1892) was an English biologist, comparative anatomist and paleontologist. Owen is generally considered to have been an outstanding naturalist with a remarkable gift for interpreting fossils.

Ow ...

. Mantell went on to demonstrate that fossil vertebra

The spinal column, a defining synapomorphy shared by nearly all vertebrates, Hagfish are believed to have secondarily lost their spinal column is a moderately flexible series of vertebrae (singular vertebra), each constituting a characteristi ...

e, which Owen had attributed to a variety of different species, all belonged to ''Iguanodon''. He also named a new genus of dinosaur called ''Hylaeosaurus

''Hylaeosaurus'' ( ; Greek: / "belonging to the forest" and / "lizard") is a herbivorous ankylosaurian dinosaur that lived about 136 million years ago, in the late Valanginian stage of the early Cretaceous period of England. It was found ...

'' and as a result became an authority on prehistoric reptiles.

Later years

In 1833, Mantell relocated toBrighton

Brighton () is a seaside resort and one of the two main areas of the City of Brighton and Hove in the county of East Sussex, England. It is located south of London.

Archaeological evidence of settlement in the area dates back to the Bronze A ...

but his medical practice suffered. He was almost rendered destitute, but for the town's council, which promptly transformed his house into a museum. There he gave a series of lectures that were published in 1838 with the title ''The wonders of geology, or, A familiar exposition of geological phenomena: being the substance of a course of lectures delivered at Brighton''. The museum in Brighton ultimately failed as a result of Mantell's habit of waiving the entrance fee. Financially destitute, Mantell offered to sell the entire collection to the British Museum

The British Museum is a public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is among the largest and most comprehensive in existence. It docum ...

in 1838 for £5,000, accepting the counter-offer of £4,000. He moved to Clapham Common

Clapham Common is a large triangular urban park in Clapham, south London, England. Originally common land for the parishes of Battersea and Clapham, it was converted to parkland under the terms of the Metropolitan Commons Act 1878. It is of g ...

in South London, where he continued his work as a doctor.

Mary Mantell left her husband in 1839. That same year, Gideon's son Walter emigrated to New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island coun ...

. Walter later sent his father some important fossils from New Zealand. Gideon's daughter, Hannah, died in 1840.

In 1841 he began to suffer from what would eventually be diagnosed as scoliosis, possibly precipitated by a carriage accident. Despite being bent, crippled and in constant pain, he continued to work with fossilised reptiles and published a number of scientific books and papers until his death. He moved to Pimlico

Pimlico () is an area of Central London in the City of Westminster, built as a southern extension to neighbouring Belgravia. It is known for its garden squares and distinctive Regency architecture. Pimlico is demarcated to the north by Victor ...

in 1844 and began to take opium

Opium (or poppy tears, scientific name: ''Lachryma papaveris'') is dried latex obtained from the seed capsules of the opium poppy '' Papaver somniferum''. Approximately 12 percent of opium is made up of the analgesic alkaloid morphine, which ...

, as a painkiller, in 1845.

Death and legacy

post-mortem

An autopsy (post-mortem examination, obduction, necropsy, or autopsia cadaverum) is a surgical procedure that consists of a thorough examination of a corpse by dissection to determine the cause, mode, and manner of death or to evaluate any d ...

showed that he had been suffering from scoliosis

Scoliosis is a condition in which a person's spine has a sideways curve. The curve is usually "S"- or "C"-shaped over three dimensions. In some, the degree of curve is stable, while in others, it increases over time. Mild scoliosis does not ty ...

. A section of Mantell's spine

Spine or spinal may refer to:

Science Biology

* Vertebral column, also known as the backbone

* Dendritic spine, a small membranous protrusion from a neuron's dendrite

* Thorns, spines, and prickles, needle-like structures in plants

* Spine (zoolo ...

was removed, preserved and stored on a shelf at the Royal College of Surgeons

The Royal College of Surgeons is an ancient college (a form of corporation) established in England to regulate the activity of surgeons. Derivative organisations survive in many present and former members of the Commonwealth. These organisations ...

of England. It remained there until 1969 when it was destroyed due to lack of space.

Mantell's surgery, on the south side of Clapham Common, is now a dental surgery.

At the time of his death Mantell was credited with discovering 4 of the 5 genera of dinosaurs then known.

In 2000, in commemoration of Mantell's discovery and his contribution to the science of palaeontology, the ''Mantell Monument'' was unveiled at Whiteman's Green, Cuckfield. The monument has been confirmed as the location of the ''Iguanodon'' fossils that Mantell first described in 1822.

He is buried at West Norwood Cemetery

West Norwood Cemetery is a rural cemetery in West Norwood in London, England. It was also known as the South Metropolitan Cemetery.

One of the first private landscaped cemeteries in London, it is one of the " Magnificent Seven" cemeteries of ...

within a sarcophagus

A sarcophagus (plural sarcophagi or sarcophaguses) is a box-like funeral receptacle for a corpse, most commonly carved in stone, and usually displayed above ground, though it may also be buried. The word ''sarcophagus'' comes from the Gre ...

attributed to Amon Henry Wilds

Amon Henry Wilds (1784 or 1790 – 13 July 1857) was an English architect. He was part of a team of three architects and builders who—working together or independently at different times—were almost solely responsible for a surge in resid ...

that replicates the sanctuary of Natakamani's Temple of Amun

Amun (; also ''Amon'', ''Ammon'', ''Amen''; egy, jmn, reconstructed as ( Old Egyptian and early Middle Egyptian) → (later Middle Egyptian) → ( Late Egyptian), cop, Ⲁⲙⲟⲩⲛ, Amoun) romanized: ʾmn) was a major ancient Egypt ...

. (The name ammonite

Ammonoids are a group of extinct marine mollusc animals in the subclass Ammonoidea of the class Cephalopoda. These molluscs, commonly referred to as ammonites, are more closely related to living coleoids (i.e., octopuses, squid and cuttlefis ...

is, coincidentally, derived from Amun.)

Works by Mantell

Sixty-seven books and memoirs appear in Agassiz and Strickland's ''Bibliographia Zoologiæ'', and forty-eight scientific papers in theRoyal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

's Catalogue.''The Fossils of the South Downs''

Royal

4to

Quarto (abbreviated Qto, 4to or 4º) is the format of a book or pamphlet produced from full sheets printed with eight pages of text, four to a side, then folded twice to produce four leaves. The leaves are then trimmed along the folds to produc ...

, 42 plates. London 1822. This was his first book, the plates of which were drawn by his wife. Expensive, at £3. 3/- (three guineas). At double the price, plates were hand-coloured.Price details from trade adverts in other volumes.

*''Outlines of the natural history of the environs of Lewes''. 4to, 24pp, 3pl. Lewes, 1824.

*''Illustrations of the Geology of Sussex'', containing figures and descriptions of the fossils of Tilgate Forest. Royal 4to, 20 plates, £2. 15s. 6d. 1827.''The Geological Age of Reptiles''

In Jameson's Edinburgh Philosophical Journal, 1831, Vol. 11, pp. 81–85

''A Narrative of the Visit of their most Gracious Majesties William IV and Queen Adelaide, to the Ancient Borough of Lewes, on the 22nd of October 1830''

London: Lupton Relfe, 1831.

''The Geology of the South-East of England''

8vo

Octavo, a Latin word meaning "in eighth" or "for the eighth time", (abbreviated 8vo, 8º, or In-8) is a technical term describing the format of a book, which refers to the size of leaves produced from folding a full sheet of paper on which multip ...

, with coloured maps, sections, and numerous plates, £1. 1/-. 1833.''Thoughts on a Pebble''

1836

8th edition, 1849

*''The Wonders of Geology'' or, a familiar exposition of geological phenomena: being the substance of a course of lectures delivered at Brighton. 2 vols, London, 1838.

Lithographic

Lithography () is a planographic method of printing originally based on the immiscibility of oil and water. The printing is from a stone (lithographic limestone) or a metal plate with a smooth surface. It was invented in 1796 by the German a ...

plates drawn by his wife. Data from 4th ed of 1840vol 1:

428p, frontis & 4 plates

vol 2:

pages 429795 plus appendix, glossary and other material, coloured frontis & 10 coloured plates, most drawn by his wife. Mantell's most extensive work.

''The Medals of Creation''

2 vols, 1844. *''A Day's Ramble in and about the Antient Town of Lewes''. London: Henry G. Bohn, 1846.

''Thoughts on Animalcules''

small 4to, 144p, 12 coloured plates. London: Murray, 1846. 1850 title: ''The invisible world revealed by the microscope or, thoughts on animalcules''.

''Geological Excursions round the Isle of Wight and along the adjacent Coast of Dorsetshire''

1847. *

''Petrifactions and their teachings''

1851.

References

Sources

* **US edition: ''Terrible Lizard: the first dinosaur hunters and the birth of a new science''. New York:Henry Holt and Company

Henry Holt and Company is an American book-publishing company based in New York City. One of the oldest publishers in the United States, it was founded in 1866 by Henry Holt and Frederick Leypoldt. Currently, the company publishes in the fields ...

, 2000.

*

*

*

External links

*A History of Dinosaur Hunting and Reconstruction

Biography at Strange Science.net

Mantell and Wilds

by the Friends of West Norwood Cemetery

(1844) First Lessons in Geology and in the Study of Organic Remains by Gideon Mantell

The journal of Gideon Mantell, Hathi Trust

{{DEFAULTSORT:Mantell, Gideon 1790 births 1852 deaths English geologists English palaeontologists 19th-century English medical doctors English obstetricians Fellows of the Royal Society People from Lewes Burials at West Norwood Cemetery Wollaston Medal winners Royal Medal winners Drug-related suicides in England