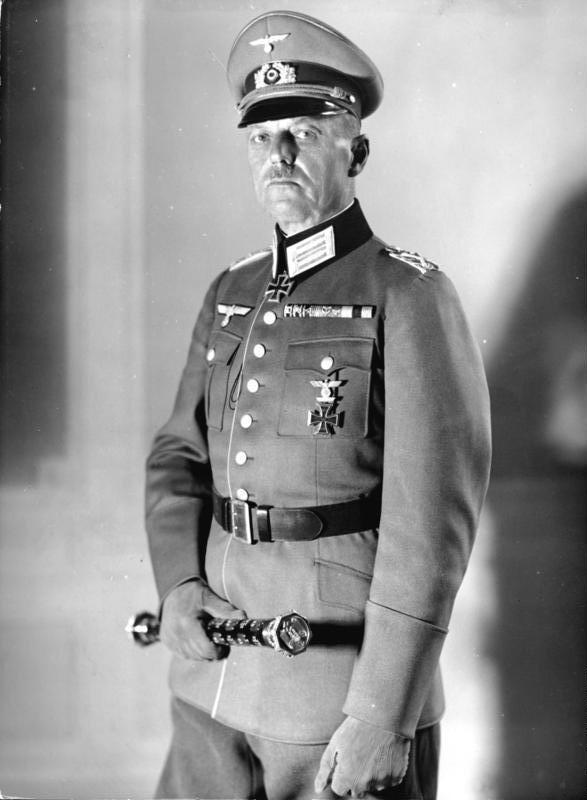

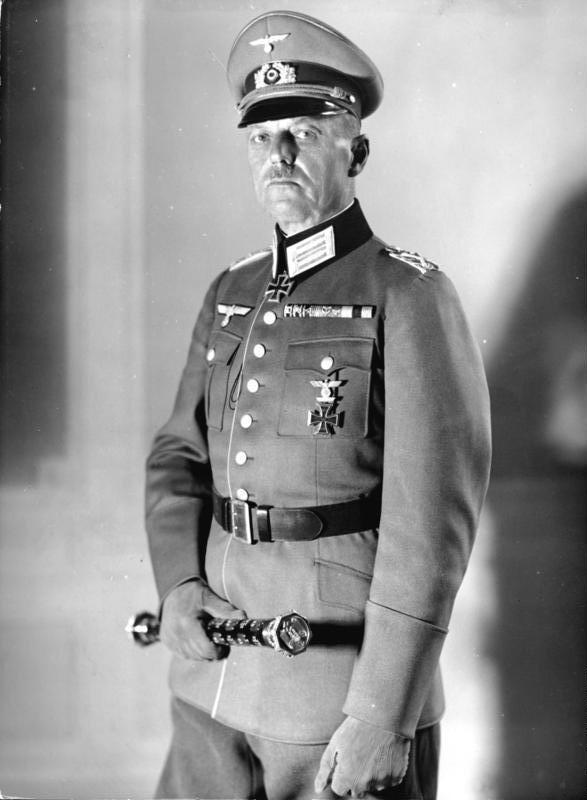

Gerd von Rundstedt on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Karl Rudolf Gerd von Rundstedt (12 December 1875 – 24 February 1953) was a German

Like most of the Army, Rundstedt feared the growing power of the

Like most of the Army, Rundstedt feared the growing power of the  During 1938 and 1939 Beck and other senior officers were hatching plots to remove Hitler from power if he provoked a new war with Britain and France over

During 1938 and 1939 Beck and other senior officers were hatching plots to remove Hitler from power if he provoked a new war with Britain and France over

Hitler's original plan was to attack in late November, before the French and British had time fully to deploy along their front. The plan, devised by Hitler, was essentially for a re-run of the invasion of 1914, with the main assault to come in the north, through Belgium and the Netherlands, then wheeling south to capture Paris, leaving the French Army anchored on the Maginot Line. Most senior officers were opposed to both the timing and the plan. Rundstedt, Manstein, Reichenau (commanding 6th Army in Army Group B), List and Brauchitsch remonstrated with Hitler in a series of meetings in October and November. They were opposed to an offensive so close to the onset of winter, and they were opposed to launching the main attack through Belgium, where the many rivers and canals would hamper armoured operations. Manstein in particular, supported by Rundstedt, argued for an armoured assault by Army Group A, across the Ardennes to the sea, cutting the British and French off in Belgium. This " Manstein Plan" was the genesis of the

Hitler's original plan was to attack in late November, before the French and British had time fully to deploy along their front. The plan, devised by Hitler, was essentially for a re-run of the invasion of 1914, with the main assault to come in the north, through Belgium and the Netherlands, then wheeling south to capture Paris, leaving the French Army anchored on the Maginot Line. Most senior officers were opposed to both the timing and the plan. Rundstedt, Manstein, Reichenau (commanding 6th Army in Army Group B), List and Brauchitsch remonstrated with Hitler in a series of meetings in October and November. They were opposed to an offensive so close to the onset of winter, and they were opposed to launching the main attack through Belgium, where the many rivers and canals would hamper armoured operations. Manstein in particular, supported by Rundstedt, argued for an armoured assault by Army Group A, across the Ardennes to the sea, cutting the British and French off in Belgium. This " Manstein Plan" was the genesis of the  Attention then turned to the attack on the French armies to the south. On 29 May, Hitler came to Rundstedt's headquarters at

Attention then turned to the attack on the French armies to the south. On 29 May, Hitler came to Rundstedt's headquarters at

Despite these successes, the campaign did not go according to plan. The front door was "kicked in", but the Red Army was not destroyed, and the Soviet state did not collapse. Once this became apparent, at the end of July, Hitler and his commanders had to decide how to proceed. Hitler ordered Army Group Centre to pause at Smolensk, while the panzer divisions were shipped to the north and the south.

Although Rundstedt opposed this diversion of forces, he was its beneficiary as attention was shifted to the southern front. He also benefited from disastrous decisions made by the Soviets. On 10 July Stalin appointed his old crony Marshal

Despite these successes, the campaign did not go according to plan. The front door was "kicked in", but the Red Army was not destroyed, and the Soviet state did not collapse. Once this became apparent, at the end of July, Hitler and his commanders had to decide how to proceed. Hitler ordered Army Group Centre to pause at Smolensk, while the panzer divisions were shipped to the north and the south.

Although Rundstedt opposed this diversion of forces, he was its beneficiary as attention was shifted to the southern front. He also benefited from disastrous decisions made by the Soviets. On 10 July Stalin appointed his old crony Marshal

In March 1942 Hitler re-appointed Rundstedt OB West, in succession to Witzleben, who was ill. He returned to the comfortable headquarters in the Hotel Pavillon Henri IV in Saint-Germain, which he had occupied in 1940–41. Rundstedt's command of French and his good relationship with the head of the collaborationist

In March 1942 Hitler re-appointed Rundstedt OB West, in succession to Witzleben, who was ill. He returned to the comfortable headquarters in the Hotel Pavillon Henri IV in Saint-Germain, which he had occupied in 1940–41. Rundstedt's command of French and his good relationship with the head of the collaborationist

The Allied invasion of Italy in September 1943 removed Rundstedt's fears that France would be invaded that summer, but he could not have doubted that the massive build-up of American troops in Britain meant that a cross-channel invasion would come in 1944. In October Rundstedt sent Hitler a memorandum on the defensive preparations. He placed no faith in the Atlantic Wall, seeing it merely as useful propaganda. He said: "We Germans, do not indulge in the tired Maginot spirit." He argued that an invasion could only be defeated by a defence in depth, with armoured reserves positioned well inland so that they could be deployed to wherever the invasion came, and launch counter-offensives to drive the invaders back. There were several problems with this, particularly the lack of fuel for rapid movements of armour, the Allied air superiority which enabled them to disrupt the transport system, and the increasingly effective sabotage efforts of the French resistance. Hitler was not persuaded: his view was that the invasion must be defeated on the beaches. Characteristically, however, he told Rundstedt he agreed with him, then sent Field Marshal

The Allied invasion of Italy in September 1943 removed Rundstedt's fears that France would be invaded that summer, but he could not have doubted that the massive build-up of American troops in Britain meant that a cross-channel invasion would come in 1944. In October Rundstedt sent Hitler a memorandum on the defensive preparations. He placed no faith in the Atlantic Wall, seeing it merely as useful propaganda. He said: "We Germans, do not indulge in the tired Maginot spirit." He argued that an invasion could only be defeated by a defence in depth, with armoured reserves positioned well inland so that they could be deployed to wherever the invasion came, and launch counter-offensives to drive the invaders back. There were several problems with this, particularly the lack of fuel for rapid movements of armour, the Allied air superiority which enabled them to disrupt the transport system, and the increasingly effective sabotage efforts of the French resistance. Hitler was not persuaded: his view was that the invasion must be defeated on the beaches. Characteristically, however, he told Rundstedt he agreed with him, then sent Field Marshal

field marshal

Field marshal (or field-marshal, abbreviated as FM) is the most senior military rank, ordinarily senior to the general officer ranks. Usually, it is the highest rank in an army and as such few persons are appointed to it. It is considered as ...

in the '' Heer'' (Army) of Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

.

Born into a Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an e ...

n family with a long military tradition, Rundstedt entered the Prussian Army

The Royal Prussian Army (1701–1919, german: Königlich Preußische Armee) served as the army of the Kingdom of Prussia. It became vital to the development of Brandenburg-Prussia as a European power.

The Prussian Army had its roots in the co ...

in 1892. During World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

, he served mainly as a staff officer. In the inter-war years, he continued his military career, reaching the rank of Colonel General () before retiring in 1938.

He was recalled at the beginning of World War II as commander of Army Group South

Army Group South (german: Heeresgruppe Süd) was the name of three German Army Groups during World War II.

It was first used in the 1939 September Campaign, along with Army Group North to invade Poland. In the invasion of Poland Army Group So ...

in the invasion of Poland

The invasion of Poland (1 September – 6 October 1939) was a joint attack on the Republic of Poland by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union which marked the beginning of World War II. The German invasion began on 1 September 1939, one week af ...

. He commanded Army Group A during the Battle of France

The Battle of France (french: bataille de France) (10 May – 25 June 1940), also known as the Western Campaign ('), the French Campaign (german: Frankreichfeldzug, ) and the Fall of France, was the German invasion of France during the Second Wor ...

, and requested the Halt Order during the Battle of Dunkirk. He was promoted to the rank of Field Marshal in 1940. In the invasion of the Soviet Union, he commanded Army Group South

Army Group South (german: Heeresgruppe Süd) was the name of three German Army Groups during World War II.

It was first used in the 1939 September Campaign, along with Army Group North to invade Poland. In the invasion of Poland Army Group So ...

, responsible for the largest encirclement in history, the Battle of Kiev. He was relieved of command in December 1941 after authorizing the withdrawal from Rostov, but was recalled in 1942 and appointed Commander-in-Chief in the West.

He was dismissed after the German defeat in Normandy in July 1944, but was again recalled as Commander-in-Chief in the West in September, holding this post until his final dismissal by Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 and the ...

in March 1945. Though aware of the various plots to depose Hitler, Rundstedt neither supported nor reported them. After the war, he was charged with war crimes, but did not face trial due to his age and poor health. He was released in 1949, and died in 1953.

Early life

Gerd von Rundstedt was born in Aschersleben, north ofHalle Halle may refer to:

Places Germany

* Halle (Saale), also called Halle an der Saale, a city in Saxony-Anhalt

** Halle (region), a former administrative region in Saxony-Anhalt

** Bezirk Halle, a former administrative division of East Germany

** Hal ...

in Prussian Saxony

The Province of Saxony (german: link=no, Provinz Sachsen), also known as Prussian Saxony () was a province of the Kingdom of Prussia and later the Free State of Prussia from 1816 until 1944. Its capital was Magdeburg.

It was formed by the m ...

(now in Saxony-Anhalt

Saxony-Anhalt (german: Sachsen-Anhalt ; nds, Sassen-Anholt) is a state of Germany, bordering the states of Brandenburg, Saxony, Thuringia and Lower Saxony. It covers an area of

and has a population of 2.18 million inhabitants, making i ...

). He was the eldest son of Gerd Arnold Konrad von Rundstedt, a cavalry officer who served in the Franco-Prussian War. The Rundstedts are an old Junker family that traced its origins to the 12th century and classed as members of the '' Uradel'', or old nobility, although they held no titles and were not wealthy. Virtually all the Rundstedt men since the time of Frederick the Great

Frederick II (german: Friedrich II.; 24 January 171217 August 1786) was King in Prussia from 1740 until 1772, and King of Prussia from 1772 until his death in 1786. His most significant accomplishments include his military successes in the Sil ...

had served in the Prussian Army

The Royal Prussian Army (1701–1919, german: Königlich Preußische Armee) served as the army of the Kingdom of Prussia. It became vital to the development of Brandenburg-Prussia as a European power.

The Prussian Army had its roots in the co ...

. Rundstedt's mother, Adelheid Fischer, was of Huguenot

The Huguenots ( , also , ) were a religious group of French Protestants who held to the Reformed, or Calvinist, tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, the Genevan burgomaster Be ...

(French Protestant) descent. He was the eldest of four brothers, all of whom became Army officers. Rundstedt's education followed the path ordained for Prussian military families: the junior cadet college at Diez, near Koblenz

Koblenz (; Moselle Franconian: ''Kowelenz''), spelled Coblenz before 1926, is a German city on the banks of the Rhine and the Moselle, a multi-nation tributary.

Koblenz was established as a Roman military post by Drusus around 8 B.C. Its nam ...

, then the military academy at Lichterfelde Lichterfelde may refer to:

* Lichterfelde (Berlin), a locality in the borough of Steglitz-Zehlendorf in Berlin, Germany

* Lichterfelde West, an elegant residential area in Berlin

* Lichterfelde, Saxony-Anhalt, a municipality in the Stendhal Distri ...

in Berlin.

Unable to meet the cost of joining a cavalry regiment, Rundstedt joined the 83rd Infantry Regiment in March 1892 as a cadet officer (). The regiment was based at Kassel

Kassel (; in Germany, spelled Cassel until 1926) is a city on the Fulda River in northern Hesse, Germany. It is the administrative seat of the Regierungsbezirk Kassel and the district of the same name and had 201,048 inhabitants in December 2020 ...

in Hesse-Kassel

The Landgraviate of Hesse-Kassel (german: Landgrafschaft Hessen-Kassel), spelled Hesse-Cassel during its entire existence, was a state in the Holy Roman Empire that was directly subject to the Emperor. The state was created in 1567 when the L ...

, which he came to regard as his home town and where he maintained a home until 1945. He undertook further training at the military college () at Hannover

Hanover (; german: Hannover ; nds, Hannober) is the capital and largest city of the German state of Lower Saxony. Its 535,932 (2021) inhabitants make it the 13th-largest city in Germany as well as the fourth-largest city in Northern Germany ...

, before being commissioned as a lieutenant in June 1893. He made a good impression on his superiors. In 1896 he was made regimental adjutant, and in 1903 he was sent to the prestigious War Academy () in Berlin for a three-year staff officer training course. At the end of his course Rundstedt was described as "an outstandingly able officer ... well suited for the General Staff." He married Luise "Bila" von Goetz in January 1902 and their only child, Hans Gerd von Rundstedt, was born in January 1903.

Rundstedt joined the General Staff of the German Army in April 1907 serving there until July 1914, when he was appointed chief of operations to the 22nd Reserve Infantry Division. This division was part of XI Corps, which in turn was part of General Alexander von Kluck's First Army. In 1914 this Army was deployed along the Belgian border, in preparation for the invasion of Belgium and France, in accordance with the German plan for victory in the west known as the Schlieffen Plan.

World War I

Rundstedt served as 22nd Division's chief of staff during the invasion of Belgium, but he saw no action since his Division was held in reserve during the initial advance. In December 1914, suffering from a lung ailment, he was promoted to Major and transferred to the military government ofAntwerp

Antwerp (; nl, Antwerpen ; french: Anvers ; es, Amberes) is the largest city in Belgium by area at and the capital of Antwerp Province in the Flemish Region. With a population of 520,504,

. In April 1915 his health recovered, and he was posted as chief of staff to the 86th Infantry Division which was serving as part of General Max von Gallwitz's forces on the Eastern Front. In September he was once again given an administrative post, as part of the military government of German-occupied Poland, based in Warsaw

Warsaw ( pl, Warszawa, ), officially the Capital City of Warsaw,, abbreviation: ''m.st. Warszawa'' is the capital and largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the River Vistula in east-central Poland, and its population is officiall ...

. He stayed in this post until November 1916, until he was promoted by being made chief of staff to an Army Corps, XXV Reserve Corps, which was fighting in the Carpathians

The Carpathian Mountains or Carpathians () are a range of mountains forming an arc across Central Europe. Roughly long, it is the third-longest European mountain range after the Urals at and the Scandinavian Mountains at . The range stretche ...

. Here he saw much action against the Russians. In October 1917 he was appointed chief of staff to LIII Corps, in northern Poland. The following month, however, the October Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key mom ...

led to the collapse of the Russian armies and the end of the war on the eastern front. In August 1918 Rundstedt was transferred to the west, as chief of staff to XV Corps in Alsace

Alsace (, ; ; Low Alemannic German/ gsw-FR, Elsàss ; german: Elsass ; la, Alsatia) is a cultural region and a territorial collectivity in eastern France, on the west bank of the upper Rhine next to Germany and Switzerland. In 2020, it had ...

, under General Felix Graf von Bothmer. Here he remained until the end of the war in November. Bothmer described him as "a wholly excellent staff officer and amiable comrade." He was awarded the Iron Cross

The Iron Cross (german: link=no, Eisernes Kreuz, , abbreviated EK) was a military decoration in the Kingdom of Prussia, and later in the German Empire (1871–1918) and Nazi Germany (1933–1945). King Frederick William III of Prussia es ...

, first class, and was recommended for the Pour le Mérite

The ' (; , ) is an order of merit (german: Verdienstorden) established in 1740 by King Frederick II of Prussia. The was awarded as both a military and civil honour and ranked, along with the Order of the Black Eagle, the Order of the Red Eag ...

, but did not receive it. He thus ended World War I, although still a major, with a high reputation as a staff officer.

Weimar Republic

Rundstedt's Corps disintegrated in the wake of defeat and theGerman Revolution

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

, but while most officers were demobilised, he remained in the Army, apparently at the request of General Wilhelm Groener, who assumed leadership of the shattered Army. He briefly rejoined the General Staff, but this was abolished under the terms of the Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June 1 ...

, signed in June 1919. In October, Rundstedt was posted to the staff of Military District () V, based in Stuttgart

Stuttgart (; Swabian: ; ) is the capital and largest city of the German state of Baden-Württemberg. It is located on the Neckar river in a fertile valley known as the ''Stuttgarter Kessel'' (Stuttgart Cauldron) and lies an hour from the Sw ...

, under General Walter von Bergmann. He was there when the attempted military coup known as the Kapp Putsch

The Kapp Putsch (), also known as the Kapp–Lüttwitz Putsch (), was an attempted coup against the German national government in Berlin on 13 March 1920. Named after its leaders Wolfgang Kapp and Walther von Lüttwitz, its goal was to undo th ...

took place in March 1920. Bergmann and Rundstedt, like most of the Army leadership, refused to support the coup attempt: Rundstedt later described it as "a failure and a very stupid one at that." This was not an indication of any fondness for the Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic (german: link=no, Weimarer Republik ), officially named the German Reich, was the government of Germany from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a Constitutional republic, constitutional federal republic for the first time in ...

on Rundstedt's part – he remained a monarchist. It was a reflection of his view that Army officers should not interfere in politics, and should support the government of the day, whatever its nature: a view he was to hold firmly to throughout his career. He testified at the Nuremberg trials

The Nuremberg trials were held by the Allies of World War II, Allies against representatives of the defeated Nazi Germany, for plotting and carrying out invasions of other countries, and other crimes, in World War II.

Between 1939 and 1945 ...

in 1946: "We generals did not concern ourselves with politics. We did not take part in any political discussions, and we did not hold any political discussions among ourselves."

Rundstedt rose steadily in the small 100,000-man army (the ) allowed to Germany by the Versailles Treaty. In May 1920 he was made chief of staff to the 3rd Cavalry Division, based in Weimar

Weimar is a city in the state of Thuringia, Germany. It is located in Central Germany between Erfurt in the west and Jena in the east, approximately southwest of Leipzig, north of Nuremberg and west of Dresden. Together with the neighbouri ...

, thus achieving his early ambition of being a cavalry commander. He was promoted to lieutenant-colonel () in 1920, and to full colonel in 1923, when he was transferred to II, based in Stettin

Szczecin (, , german: Stettin ; sv, Stettin ; Latin: ''Sedinum'' or ''Stetinum'') is the capital and largest city of the West Pomeranian Voivodeship in northwestern Poland. Located near the Baltic Sea and the German border, it is a major s ...

. In 1926 he was made chief of staff to Group Command () 2, which covered the whole of western Germany and was based in Kassel

Kassel (; in Germany, spelled Cassel until 1926) is a city on the Fulda River in northern Hesse, Germany. It is the administrative seat of the Regierungsbezirk Kassel and the district of the same name and had 201,048 inhabitants in December 2020 ...

, and promoted to major general (). In 1928 Rundstedt finally left staff positions behind him and was made commander of the 2nd Cavalry Division, based in Breslau. This was considered a front-line posting, given Germany's tense relations with Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

and the fact that Poland at this time had a much bigger army than Germany.

In January 1932, Rundstedt was appointed commander of III, based in Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitu ...

, and also given command of the 3rd Infantry Division. This brought him, at 57, into the highest ranks of the German Army, reflected in his promotion to Lieutenant General (). It also inevitably brought him into close contact with the political world, which was in a disturbed state due to the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

and subsequent rise of Hitler's Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that created and supported t ...

. The Defence Minister, General Kurt von Schleicher, was scheming to bring the Nazis into the government, and the Chancellor, Franz von Papen

Franz Joseph Hermann Michael Maria von Papen, Erbsälzer zu Werl und Neuwerk (; 29 October 18792 May 1969) was a German conservative politician, diplomat, Prussian nobleman and General Staff officer. He served as the chancellor of Germany ...

, was planning to overthrow the Social Democrat

Social democracy is a political, social, and economic philosophy within socialism that supports political and economic democracy. As a policy regime, it is described by academics as advocating economic and social interventions to promote soc ...

government of Prussia, Germany's largest state. Despite his dislike of politics, Rundstedt could not remain uninvolved in these matters. In July 1932 Papen used his emergency powers to dismiss the Prussian Government. Martial law was briefly declared in Berlin and Rundstedt was made martial law plenipotentiary. He protested to Papen about this and martial law was lifted after a few days. In October Rundstedt was promoted to full General and given command of 1, covering the whole of eastern Germany.

Serving the Nazi regime

In January 1933 Hitler became chancellor, and within a few months, dictator. The Defence Minister, General Werner von Blomberg, ensured that the Army remained loyal to the new regime. In February he arranged for Hitler to meet with senior generals, including Rundstedt. Hitler assured the generals that he favoured a strong Army and that there would be no interference with its internal affairs. Rundstedt was satisfied with this, but made it clear in private conversations that he did not like the Nazi regime. He also said, however, that he would do nothing to oppose it. In 1934, when GeneralKurt Freiherr von Hammerstein-Equord

Kurt Gebhard Adolf Philipp Freiherr von Hammerstein-Equord (26 September 1878 – 24 April 1943) was a German general (''Generaloberst'') who was the Commander-in-Chief of the Reichswehr, the Weimar Republic's armed forces. He is regarded as "an ...

resigned as chief of staff, Hitler wished to appoint General Walther von Reichenau to succeed him. Rundstedt led a group of senior officers in opposing the appointment, on the grounds that Reichenau was too openly a supporter of the regime. Hitler and Blomberg backed down and General Werner Freiherr von Fritsch

Thomas Ludwig Werner Freiherr von Fritsch (4 August 1880 – 22 September 1939) was a member of the German High Command. He was Commander-in-Chief of the German Army from February 1934 until February 1938, when he was forced to resign after he ...

was appointed instead. When Fritsch was forced to resign in 1938, Rundstedt again blocked Reichenau's appointment, and the post went to General Walther von Brauchitsch

Walther Heinrich Alfred Hermann von Brauchitsch (4 October 1881 – 18 October 1948) was a German field marshal and the Commander-in-Chief (''Oberbefehlshaber'') of the German Army during World War II. Born into an aristocratic military family, ...

.

Like most of the Army, Rundstedt feared the growing power of the

Like most of the Army, Rundstedt feared the growing power of the Sturmabteilung

The (; SA; literally "Storm Detachment") was the original paramilitary wing of the Nazi Party. It played a significant role in Adolf Hitler's rise to power in the 1920s and 1930s. Its primary purposes were providing protection for Nazi ralli ...

(SA) and was relieved when it was purged, although he and many others were angered that two generals, Schleicher and Ferdinand von Bredow

Ferdinand von Bredow (16 May 1884 – 30 June 1934) was a German ''Generalmajor'' and head of the ''Abwehr'' (the military intelligence service) in the Reich Defence Ministry and deputy defence minister in Kurt von Schleicher's short-lived cabi ...

, were killed. He was among the senior officers who later persuaded Hitler to have these two officers posthumously (but secretly) rehabilitated. Some sources also claim he was among those senior officers who demanded courts-martial for those responsible for the murders, although Rundstedt didn't testify to that at Nuremberg. The Army was uncomfortable with the purge but Rundstedt, and the rest of the Army, still took the personal oath of loyalty to Hitler that Blomberg introduced. Rundstedt also supported the regime's plans for rearmament, culminating in the denunciation of the Treaty of Versailles in 1935, which was followed by the reintroduction of conscription. By 1935, when he turned 60, Rundstedt was the senior officer of the German Army in terms of service, and second only to Blomberg in rank. Recognising his status, Hitler cultivated him, appointing him as Germany's representative at the funeral of King George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until his death in 1936.

Born during the reign of his grandmother Qu ...

in January 1936.

Given his prestige, Rundstedt was a central figure in the Blomberg–Fritsch Affair which engulfed the German Army in early 1938. This was a political manoeuvre by senior Nazis Hermann Göring and Heinrich Himmler to strengthen their positions within the Nazi regime at the expense of the military leadership. Together they forced the resignation of both Blomberg and Fritsch, the former under threat of blackmail because of his second wife's dubious past, and the latter on fabricated charges of homosexuality. On 31 January, Rundstedt and the Army Chief of Staff, General Ludwig Beck, representing the officer corps, had an angry meeting with Hitler. Rundstedt agreed that Blomberg had disgraced himself and demanded that he be court-martialled, which Hitler refused. On the other hand, he defended Fritsch, correctly accusing Himmler of having fabricated the allegations against him. He insisted that Fritsch have the right to defend himself before a Court of Honour, which Hitler reluctantly agreed to. Beck promoted Rundstedt as Fritsch's successor, but Rundstedt declined, and the post went to Brauchitsch. At Beck's urging, Fritsch challenged Himmler to a duel, but Rundstedt (as senior officer of the Army) declined to pass on Fritsch's letter.

During 1938 and 1939 Beck and other senior officers were hatching plots to remove Hitler from power if he provoked a new war with Britain and France over

During 1938 and 1939 Beck and other senior officers were hatching plots to remove Hitler from power if he provoked a new war with Britain and France over Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

or Poland, a war they were convinced Germany would lose. Rundstedt was aware of these plots, and Beck tried to recruit him to the plotters' ranks, knowing of his disdain for the Nazi regime. But Rundstedt stuck firmly to his position that officers should not be involved in politics, no matter how grave the issues at stake. On the other hand, he did not report these approaches to Hitler or the Gestapo

The (), abbreviated Gestapo (; ), was the official secret police of Nazi Germany and in German-occupied Europe.

The force was created by Hermann Göring in 1933 by combining the various political police agencies of Prussia into one orga ...

, then or later. From a purely military point of view, Rundstedt was apprehensive about Hitler's plans to attack Czechoslovakia, since he believed that Britain and France would intervene and Germany would be defeated. Brauchitsch lacked the courage to oppose Hitler directly, but agreed to Beck's request for a meeting of senior commanders. At the meeting widespread opposition to Hitler's plans to coerce Czechoslovakia over the Sudetenland

The Sudetenland ( , ; Czech and sk, Sudety) is the historical German name for the northern, southern, and western areas of former Czechoslovakia which were inhabited primarily by Sudeten Germans. These German speakers had predominated in the ...

issue was expressed. Beck urged the officers to oppose Hitler's plans openly, but Rundstedt, while agreeing about the dangers of war before Germany was fully re-armed, would not support him, but declared himself unwilling to provoke a new crisis between Hitler and the Army. He advised Brauchitsch not to confront Hitler, apparently afraid that Brauchitsch would be dismissed and replaced by Reichenau. When Hitler heard about the meeting, Beck was forced to resign. Even after this, two of Rundstedt's friends, Generals Erwin von Witzleben and Erich Hoepner

Erich Kurt Richard Hoepner (14 September 1886 – 8 August 1944) was a German general during World War II. An early proponent of mechanisation and armoured warfare, he was a Wehrmacht army corps commander at the beginning of the war, leading ...

, remained involved in anti-Hitler plots and continued to try to recruit him.

In November 1938, shortly after his division had taken part in the bloodless occupation of the Sudetenland, Rundstedt retired from the Army with the rank of Colonel-General (), second only to the rank of Field Marshal. It was suggested that Hitler had forced him out, either because of his opposition to the plan to invade Czechoslovakia or because of his support for Fritsch, but this seems not be the case: he had in fact asked permission to retire some time earlier. Just short of his 63rd birthday, he was not in good health and missed his family – he was now a grandfather. Moreover, despite their recent confrontations, he remained on good terms with Hitler, who made him honorary colonel () of his old regiment on his retirement. Rundstedt also agreed that in the event of war he would return to active service.

World War II

Invasion of Poland

Rundstedt's retirement did not last long. By early 1939 Hitler had decided to force a confrontation with Poland over the Polish Corridor, and planning for a war with Poland began. In May, Hitler approved Rundstedt's appointment as commander of Army Group South, to invade Poland fromSilesia

Silesia (, also , ) is a historical region of Central Europe that lies mostly within Poland, with small parts in the Czech Silesia, Czech Republic and Germany. Its area is approximately , and the population is estimated at around 8,000,000. S ...

and Slovakia

Slovakia (; sk, Slovensko ), officially the Slovak Republic ( sk, Slovenská republika, links=no ), is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east, Hungary to the south, Austria to the ...

. His chief of staff was General Erich von Manstein, his chief of operations Colonel Günther Blumentritt. His principal field commanders would be (from west to east as they entered Poland) General Johannes Blaskowitz

Johannes Albrecht Blaskowitz (10 July 1883 – 5 February 1948) was a German '' Generaloberst'' during World War II. He was a recipient of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves and Swords. After joining the Imperial German Army i ...

(8th Army), General Walther von Reichenau (10th Army), and General Wilhelm List

Wilhelm List (14 May 1880 – 17 August 1971) was a German field marshal during World War II who was convicted of war crimes by a US Army tribunal after the war. List commanded the 14th Army in the invasion of Poland and the 12th Army in the ...

(14 Army).

Rundstedt's armies advanced rapidly into southern Poland, capturing Kraków

Kraków (), or Cracow, is the second-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula, Vistula River in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, the city dates back to the seventh century. Kraków was the official capital of Poland un ...

on 6 September, but Reichenau's over-ambitious attempt to take Warsaw

Warsaw ( pl, Warszawa, ), officially the Capital City of Warsaw,, abbreviation: ''m.st. Warszawa'' is the capital and largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the River Vistula in east-central Poland, and its population is officiall ...

by storm on 9 September was repelled. Soon after, Blaskowitz's exposed northern flank was attacked by the Polish Poznań Army

Army Poznań ( pl, Armia Poznań) led by Major General Tadeusz Kutrzeba was one of the Polish Armies during the Invasion of Poland in 1939.

Tasks

Flanked by Armia Pomorze to the north and Łódź Army to the south, the Army was to provide fla ...

, leading to the major engagement of the Polish campaign, the Battle of the Bzura. Rundstedt and Manstein travelled to Blaskowitz's headquarters to take charge, and by 11 September the Poles had been contained in a pocket around Kutno. By 18 September the Poznan Army had been destroyed, and Warsaw was besieged. Reichenau's forces took Lublin

Lublin is the ninth-largest city in Poland and the second-largest city of historical Lesser Poland. It is the capital and the center of Lublin Voivodeship with a population of 336,339 (December 2021). Lublin is the largest Polish city east of ...

on 11 September, while List's army was advancing to the east towards Lvov, where they eventually linked up with Soviet forces advancing from the east under the terms of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact

, long_name = Treaty of Non-Aggression between Germany and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics

, image = Bundesarchiv Bild 183-H27337, Moskau, Stalin und Ribbentrop im Kreml.jpg

, image_width = 200

, caption = Stalin and Ribbentrop shaking ...

. Warsaw surrendered on 28 September, and by 6 October fighting in southern Poland had ceased.

From the first days of the invasion, there had been incidents of German troops shooting Polish soldiers after they had surrendered, and killing civilians, especially Polish Jews

The history of the Jews in Poland dates back at least 1,000 years. For centuries, Poland was home to the largest and most significant Ashkenazi Jewish community in the world. Poland was a principal center of Jewish culture, because of the l ...

. Some of these incidents were the work of units of the SS-VT, forerunner of the Waffen-SS, but some involved regular Army units. Rundstedt's biographer says: "There is certainly no evidence that Rundstedt ever condoned, let alone encouraged, these acts." Rundstedt told Reichenau that such actions did not have his authorisation. In fact, both Rundstedt and Blaskowitz complained to the chief of staff, General Franz Halder

Franz Halder (30 June 1884 – 2 April 1972) was a German general and the chief of staff of the Army High Command (OKH) in Nazi Germany from 1938 until September 1942. During World War II, he directed the planning and implementation of Operati ...

, about the Army Command's apparent tolerance of such incidents. Nevertheless, as commander of Army Group South, Rundstedt was legally responsible for the behaviour of his troops, and these incidents later formed part of the charges of war crimes against him.

Behind the Army came SS (task forces) commanded by Theodor Eicke

Theodor Eicke (17 October 1892 – 26 February 1943) was a senior SS functionary and Waffen SS divisional commander during the Nazi era. He was one of the key figures in the development of Nazi concentration camps. Eicke served as the sec ...

, who began systematically executing Jews and members of the Polish educated classes. One commanded by Udo von Woyrsch

Udo Gustav Wilhelm Egon von Woyrsch (24 July 1895 – 14 January 1983) was a high-ranking SS official in Nazi Germany who participated in implementation of the regime's racial policies during World War II.

First World War

From early 1914 ...

operated in 14th Army's area. At Dynów Woyrsch's men herded the town's Jews into the synagogue

A synagogue, ', 'house of assembly', or ', "house of prayer"; Yiddish: ''shul'', Ladino: or ' (from synagogue); or ', "community". sometimes referred to as shul, and interchangeably used with the word temple, is a Jewish house of wor ...

then burned it down. By 20 September, over 500 Jews had been killed. In 1939, this was still too much for most German Army officers to stand. After complaints from numerous officers, Rundstedt banned Woyrsch's units from the area, but after his departure his order was rescinded. On 20 October Rundstedt resigned his command and was transferred to the western front.

Invasion of France and the Low Countries

On 25 October, Rundstedt took up his new post as commander of Army Group A, facing the French border in the Ardennes mountains sector, and based inKoblenz

Koblenz (; Moselle Franconian: ''Kowelenz''), spelled Coblenz before 1926, is a German city on the banks of the Rhine and the Moselle, a multi-nation tributary.

Koblenz was established as a Roman military post by Drusus around 8 B.C. Its nam ...

. To his north Army Group B under General Fedor von Bock

Moritz Albrecht Franz Friedrich Fedor von Bock (3 December 1880 – 4 May 1945) was a German who served in the German Army during the Second World War. Bock served as the commander of Army Group North during the Invasion of Poland ...

faced the Dutch and Belgian borders, while to his south Army Group C under General Wilhelm Ritter von Leeb

Wilhelm Josef Franz Ritter von Leeb (5 September 1876 – 29 April 1956) was a German field marshal and war criminal in World War II. Leeb was a highly decorated officer in World War I and was awarded the Military Order of Max Joseph which gr ...

faced the French along the Maginot Line

The Maginot Line (french: Ligne Maginot, ), named after the Minister of the Armed Forces (France), French Minister of War André Maginot, is a line of concrete fortifications, obstacles and weapon installations built by French Third Republic, F ...

. Manstein was again his chief of staff and Blumentritt his chief of operations, although Manstein soon departed to command an infantry corps and was replaced by General Georg von Sodenstern. Rundstedt's main field commanders (from north to south) were Blaskowitz (9th Army), List (12th Army) and General Ernst Busch (16th Army).

Hitler's original plan was to attack in late November, before the French and British had time fully to deploy along their front. The plan, devised by Hitler, was essentially for a re-run of the invasion of 1914, with the main assault to come in the north, through Belgium and the Netherlands, then wheeling south to capture Paris, leaving the French Army anchored on the Maginot Line. Most senior officers were opposed to both the timing and the plan. Rundstedt, Manstein, Reichenau (commanding 6th Army in Army Group B), List and Brauchitsch remonstrated with Hitler in a series of meetings in October and November. They were opposed to an offensive so close to the onset of winter, and they were opposed to launching the main attack through Belgium, where the many rivers and canals would hamper armoured operations. Manstein in particular, supported by Rundstedt, argued for an armoured assault by Army Group A, across the Ardennes to the sea, cutting the British and French off in Belgium. This " Manstein Plan" was the genesis of the

Hitler's original plan was to attack in late November, before the French and British had time fully to deploy along their front. The plan, devised by Hitler, was essentially for a re-run of the invasion of 1914, with the main assault to come in the north, through Belgium and the Netherlands, then wheeling south to capture Paris, leaving the French Army anchored on the Maginot Line. Most senior officers were opposed to both the timing and the plan. Rundstedt, Manstein, Reichenau (commanding 6th Army in Army Group B), List and Brauchitsch remonstrated with Hitler in a series of meetings in October and November. They were opposed to an offensive so close to the onset of winter, and they were opposed to launching the main attack through Belgium, where the many rivers and canals would hamper armoured operations. Manstein in particular, supported by Rundstedt, argued for an armoured assault by Army Group A, across the Ardennes to the sea, cutting the British and French off in Belgium. This " Manstein Plan" was the genesis of the blitzkrieg

Blitzkrieg ( , ; from 'lightning' + 'war') is a word used to describe a surprise attack using a rapid, overwhelming force concentration that may consist of armored and motorized or mechanized infantry formations, together with close air ...

of May 1940.

A combination of bad weather, the arguments of his generals, and a breach of security when the details of the original plan fell into Allied hands, eventually led Hitler to agree to postpone the attack until early 1940, when it was again delayed by the invasion of Denmark and Norway. In February, Hitler finally accepted the Manstein Plan. General Günther von Kluge's 4th Army and General Maximilian Reichsfreiherr von Weichs's 2nd Army were transferred from Army Group B to Rundstedt's command. General Ewald von Kleist was now to command Panzer

This article deals with the tanks (german: panzer) serving in the German Army (''Deutsches Heer'') throughout history, such as the World War I tanks of the Imperial German Army, the interwar and World War II tanks of the Nazi German Wehrma ...

(Armoured) Group Kleist, consisting of three armoured corps, led by Heinz Guderian, Georg-Hans Reinhardt and Hermann Hoth. These armoured corps were to be the spearhead of the German thrust into France. Although Manstein is often credited for the change of plans, he himself acknowledged Rundstedt's decisive role. "I would stress that my commander, Colonel-General von Rundstedt, agreed with my view throughout, and backed our recommendations to the full. Without his sanction we could never have kept up our attempts to change OKW's mind."

During this hiatus, the group of senior officers who were plotting against Hitler's war plans, led by Halder, renewed their efforts, convinced that an attack in the west would lead to a war which Germany would lose. Brauchitsch agreed with Halder's fears, but continued to vacillate about opposing Hitler – he asked Reichenau and Rundstedt to remonstrate with Hitler, but they refused. Witzleben suggested that Rundstedt, Leeb and Bock should jointly refuse to carry out Hitler's orders to carry out the attack. Two of the conspirators, Abwehr

The ''Abwehr'' ( German for ''resistance'' or ''defence'', but the word usually means ''counterintelligence'' in a military context; ) was the German military-intelligence service for the ''Reichswehr'' and the '' Wehrmacht'' from 1920 to 1944. ...

officers Hans Oster and Hans Bernd Gisevius, discussed this with Leeb, who turned them down but did not report them. On 13 March, Himmler came to Koblenz to give the generals, including Rundstedt, an ideological lecture, in the course of which he made it clear that the atrocities against civilians which some of them had witnessed in Poland had been carried out on his orders, and with the approval of Hitler. "I do nothing that the Führer does not know", he said.

The attack was finally launched on 10 May. By 14 May, Guderian and Hoth had crossed the Meuse

The Meuse ( , , , ; wa, Moûze ) or Maas ( , ; li, Maos or ) is a major European river, rising in France and flowing through Belgium and the Netherlands before draining into the North Sea from the Rhine–Meuse–Scheldt delta. It has a ...

and had broken open the Allied front. As planned, the British and French had advanced into Belgium to meet Bock's offensive, and were in danger of being cut off there by a German thrust to the sea. Both Hitler and Rundstedt had doubts about the safety of allowing the armoured corps to get too far ahead of their infantry support, however. Hitler sent the chief of staff of the Armed Forces Supreme Command (, OKW), General Wilhelm Keitel, to Rundstedt's headquarters, to urge caution. In Halder's words, Hitler was "frightened by his own success ... afraid to take any chance." Guderian objected vehemently to being ordered to halt, and Rundstedt was forced to mediate between Hitler and his impetuous armoured commanders, who were backed by Halder. By 20 May, Guderian's tanks had reached the sea at Abbeville and closed the trap on the British and French, who were already in retreat to the English Channel

The English Channel, "The Sleeve"; nrf, la Maunche, "The Sleeve" ( Cotentinais) or ( Jèrriais), ( Guernésiais), "The Channel"; br, Mor Breizh, "Sea of Brittany"; cy, Môr Udd, "Lord's Sea"; kw, Mor Bretannek, "British Sea"; nl, Het Ka ...

ports.

By this time, however, Kleist's armoured forces were thinly stretched and had suffered losses of up to 50% of their tanks. Kleist asked Rundstedt for a pause while the armoured units recovered and the infantry caught up, and Rundstedt agreed to this. At the same time, Göring attempted to persuade Hitler that the Luftwaffe

The ''Luftwaffe'' () was the aerial-warfare branch of the German '' Wehrmacht'' before and during World War II. Germany's military air arms during World War I, the '' Luftstreitkräfte'' of the Imperial Army and the '' Marine-Fliegerabt ...

could destroy the trapped Allied armies, freeing the German forces to turn south towards Paris. Hitler accepted this view, and on 24 May issued what became known as the Halt Order, preventing the German armour from rapidly capturing Calais

Calais ( , , traditionally , ) is a port city in the Pas-de-Calais department, of which it is a subprefecture. Although Calais is by far the largest city in Pas-de-Calais, the department's prefecture is its third-largest city of Arras. Th ...

and Dunkirk

Dunkirk (french: Dunkerque ; vls, label=French Flemish, Duunkerke; nl, Duinkerke(n) ; , ;) is a commune in the department of Nord in northern France.

. The Luftwaffe were unable to destroy the Allied armies, however, and the halt allowed the British Expeditionary Force and many French troops to be evacuated from Dunkirk. This decision, for which Hitler, Rundstedt and Kleist shared responsibility, proved very costly to Germany's war effort in the long term. After the war, Rundstedt described the Halt Order as "an incredible blunder" and assigned full blame to Hitler. His biographer concedes that this "does not represent the whole truth", because the original impetus for a pause came from Kleist and Rundstedt himself.

Attention then turned to the attack on the French armies to the south. On 29 May, Hitler came to Rundstedt's headquarters at

Attention then turned to the attack on the French armies to the south. On 29 May, Hitler came to Rundstedt's headquarters at Charleville-Mézières

or ''Carolomacérienne''

, image flag=Flag of Charleville Mezieres.svg

Charleville-Mézières () is a commune of northern France, capital of the Ardennes department, Grand Est.

Charleville-Mézières is located on the banks of the river Meuse.

...

to discuss the new offensive. Bock's Army Group B on the right was to advance on Paris, while Rundstedt's Army Group A, now consisting only of List's 12th Army, Weichs's 2nd Army and Busch's 16th Army, was to attack towards Soissons

Soissons () is a commune in the northern French department of Aisne, in the region of Hauts-de-France. Located on the river Aisne, about northeast of Paris, it is one of the most ancient towns of France, and is probably the ancient capital o ...

and Rheims. Rundstedt's attack began on 9 June, and within a few days had broken the French resistance

The French Resistance (french: La Résistance) was a collection of organisations that fought the German occupation of France during World War II, Nazi occupation of France and the Collaborationism, collaborationist Vichy France, Vichy régim ...

. By 12 June, his forces were across the Marne and advancing south-east towards Alsace

Alsace (, ; ; Low Alemannic German/ gsw-FR, Elsàss ; german: Elsass ; la, Alsatia) is a cultural region and a territorial collectivity in eastern France, on the west bank of the upper Rhine next to Germany and Switzerland. In 2020, it had ...

. Dijon

Dijon (, , ) (dated)

* it, Digione

* la, Diviō or

* lmo, Digion is the prefecture of the Côte-d'Or department and of the Bourgogne-Franche-Comté region in northeastern France. the commune had a population of 156,920.

The earlie ...

fell on 16 June and Lyon

Lyon,, ; Occitan: ''Lion'', hist. ''Lionés'' also spelled in English as Lyons, is the third-largest city and second-largest metropolitan area of France. It is located at the confluence of the rivers Rhône and Saône, to the northwest of ...

on 20 June. By this time French resistance was crumbling and on 22 June the French requested an armistice. In July, Hitler announced that Rundstedt and a number of other field commanders were to be promoted to the rank of Field Marshal () during the 1940 Field Marshal Ceremony. Although Rundstedt wished to resume his retirement, he was persuaded by Hitler to stay in France and set up headquarters at Saint-Germain-en-Laye about outside Paris. There he oversaw the planning for the proposed invasion of Britain, Operation Sealion, but never took the prospects for this operation seriously, and was not surprised when Hitler called it off in September after the Luftwaffe's setback in the Battle of Britain

The Battle of Britain, also known as the Air Battle for England (german: die Luftschlacht um England), was a military campaign of the Second World War, in which the Royal Air Force (RAF) and the Fleet Air Arm (FAA) of the Royal Navy defende ...

. Even then, Rundstedt was not to be allowed to retire, when in October Hitler appointed him Commander-in-Chief West (, or OB West).

Planning the war against the Soviet Union

By July 1940 Hitler was turning his mind to the invasion of theSoviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

, commissioning General Erich Marcks to prepare preliminary plans. Although the Hitler-Stalin pact had served Germany's interests well, both strategically and economically, his whole career had been based on anti-communism and the belief that "Jewish Bolshevism" was the main threat to Germany and the Aryan

Aryan or Arya (, Indo-Iranian *''arya'') is a term originally used as an ethnocultural self-designation by Indo-Iranians in ancient times, in contrast to the nearby outsiders known as 'non-Aryan' (*''an-arya''). In Ancient India, the term ...

race. In December Hitler made a firm decision for an attack on the Soviets the following spring, codenamed Operation Barbarossa

Operation Barbarossa (german: link=no, Unternehmen Barbarossa; ) was the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and many of its Axis allies, starting on Sunday, 22 June 1941, during the Second World War. The operation, code-named afte ...

. At this point Rundstedt learned that he was to give up his quiet life in occupied France and assume command of Army Group South, tasked with the conquest of Ukraine. Leeb would command in the north, heading for Leningrad

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

, and Bock in the centre, charged with capturing Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 million ...

. On the way, the three army groups were to encircle and destroy the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian language, Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist R ...

before it could retreat into the Russian interior.

Rundstedt, like most German officers, had favoured the policy of good relations with the Soviets followed by the commander General Hans von Seekt during the Weimar Republic years, when the Soviet connection was seen as a counter to the threat from Poland. He was also apprehensive about launching a new war in the east while Britain was undefeated. If so, he did nothing to oppose them, and in this he was in company even with officers who disliked and opposed Hitler's regime, such as Halder, who threw themselves into planning the invasion, and believed it would succeed. Even the most experienced officers shared Hitler's contempt for the Soviet state and army. "You have only to kick in the door," Hitler told Rundstedt, "and the whole rotten structure will come crashing down."

In March Rundstedt left Paris to set up Army Group South's headquarters in Breslau. On the way he attended a conference in Berlin at which Hitler addressed senior officers. He made it clear that the ordinary rules of warfare would not apply to the Russian campaign. "This is a war of extermination", he told them. "We do not wage war to preserve the enemy." This gave the generals a clear warning that they would be expected not to obstruct Hitler's wider war aims in the east – the extermination of the Jews and the reduction of the Slavic peoples to serfdom under a new (Master race) of German settlers. As part of this strategy, the Commissar Order

The Commissar Order (german: Kommissarbefehl) was an order issued by the German High Command ( OKW) on 6 June 1941 before Operation Barbarossa. Its official name was Guidelines for the Treatment of Political Commissars (''Richtlinien für die Be ...

was issued, which stated that all Red Army commissar

Commissar (or sometimes ''Kommissar'') is an English transliteration of the Russian (''komissar''), which means ' commissary'. In English, the transliteration ''commissar'' often refers specifically to the political commissars of Soviet and E ...

s were to be executed when captured. Rundstedt testified at Nuremberg about the attitude of the Army to this Order: "Our attitude was unanimously and absolutely against it. Immediately after the conference we approached Brauchitsch and told him that this was impossible ... The order was simply not carried out." This latter statement was clearly untrue, as the Commissar Order was widely carried out. But whether Rundstedt knew this was another matter, and this question was later to figure prominently in the issue of whether to charge him with war crimes.

Barbarossa was initially scheduled for May, at the beginning of the Russian spring, but was postponed until June because unseasonably wet weather made the roads impassable for armour (not because of the German invasion of Yugoslavia and Greece in April, as is commonly supposed). Rundstedt moved his headquarters to Tarnów

Tarnów () is a city in southeastern Poland with 105,922 inhabitants and a metropolitan area population of 269,000 inhabitants. The city is situated in the Lesser Poland Voivodeship since 1999. From 1975 to 1998, it was the capital of the Tarn� ...

in south-eastern Poland. Since the dividing line between Army Group Centre

Army Group Centre (german: Heeresgruppe Mitte) was the name of two distinct strategic German Army Groups that fought on the Eastern Front in World War II. The first Army Group Centre was created on 22 June 1941, as one of three German Army for ...

and Army Group South was just south of Brest-Litovsk

Brest ( be, Брэст / Берасьце, Bieraście, ; russian: Брест, ; uk, Берестя, Berestia; lt, Brasta; pl, Brześć; yi, בריסק, Brisk), formerly Brest-Litovsk (russian: Брест-Литовск, lit=Lithuanian Br ...

, he was in command of more than half of the total German-Soviet front. Sodenstern was again his chief of staff. Under his command were (from north to south) Reichenau (6th Army), Kleist (1st Panzer Army) and General Carl-Heinrich von Stülpnagel

Carl-Heinrich Rudolf Wilhelm von Stülpnagel (2 January 1886 – 30 August 1944) was a German general in the Wehrmacht during World War II who was an army level commander. While serving as military commander of German-occupied France and as comm ...

(17th Army). These three armies, bunched between Lublin and the Carpathians, were to thrust south-eastwards into Ukraine, aiming to capture Kiev

Kyiv, also spelled Kiev, is the capital and most populous city of Ukraine. It is in north-central Ukraine along the Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2021, its population was 2,962,180, making Kyiv the seventh-most populous city in Europe.

Ky ...

and encircle and destroy the Soviet forces west of the Dnieper

}

The Dnieper () or Dnipro (); , ; . is one of the major transboundary rivers of Europe, rising in the Valdai Hills near Smolensk, Russia, before flowing through Belarus and Ukraine to the Black Sea. It is the longest river of Ukraine an ...

. In the south, General Eugen Ritter von Schobert

Eugen Siegfried Erich Ritter von Schobert (13 March 1883 – 12 September 1941) was a German general during World War II. He commanded the 11th Army during Operation Barbarossa, the invasion of the Soviet Union. Schobert died when his observati ...

(11th Army), supported by the Hungarian and Romanian armies, and also an Italian Army Corps, was to advance into Bessarabia

Bessarabia (; Gagauz: ''Besarabiya''; Romanian: ''Basarabia''; Ukrainian: ''Бессара́бія'') is a historical region in Eastern Europe, bounded by the Dniester river on the east and the Prut river on the west. About two thirds o ...

(now Moldova

Moldova ( , ; ), officially the Republic of Moldova ( ro, Republica Moldova), is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by Romania to the west and Ukraine to the north, east, and south. The unrecognised state of Transnistri ...

) and the southern Ukraine. It's unlikely that Rundstedt thought a decisive victory was possible at this point; while saying farewell to the commander of Army Group North in early May, he remarked: "See you again in Siberia."

Operation Barbarossa

The attack began on 22 June. Despite ample warning from intelligence sources and defectors,Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet Union, Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as Ge ...

and the Soviet Command were caught by surprise, and the Germans rapidly broke through the frontier defences, helped by their total command of the air. But the Soviet commander in northern Ukraine, Colonel-General Mikhail Kirponos, was one of the better Soviet generals, and he commanded the Red Army's largest and best-equipped force: nearly a million men and 4,800 tanks. The Germans soon encountered stubborn resistance. Rundstedt testified at Nuremberg: "The resistance at the frontier was not too great, but it grew continually as we advanced into the interior of the country. Very strong tank forces, tanks of a better type, far superior to ours, appeared." The Soviet tank armies were in fact stronger than the German panzer divisions, and in the T-34

The T-34 is a Soviet medium tank introduced in 1940. When introduced its 76.2 mm (3 in) tank gun was less powerful than its contemporaries while its 60-degree sloped armour provided good protection against anti-tank weapons. The C ...

they possessed a superior tank: Kleist called it "the finest tank in the world." Rundstedt said after the war: "I realised soon after the attack that everything that had been written about Russia was wrong." But at this stage of the war the Red Army tank commanders lacked the tactical skill and experience of the German panzer commanders, and after ten days of bitter fighting Kleist's armour broke through, reaching Zhitomir, only 130 km from Kiev, on 12 July. By 30 July the Red Army in Ukraine was in full retreat. Rundstedt and his commanders were confident that they could seize Kiev "off the march," that is, without a prolonged siege.

Despite these successes, the campaign did not go according to plan. The front door was "kicked in", but the Red Army was not destroyed, and the Soviet state did not collapse. Once this became apparent, at the end of July, Hitler and his commanders had to decide how to proceed. Hitler ordered Army Group Centre to pause at Smolensk, while the panzer divisions were shipped to the north and the south.

Although Rundstedt opposed this diversion of forces, he was its beneficiary as attention was shifted to the southern front. He also benefited from disastrous decisions made by the Soviets. On 10 July Stalin appointed his old crony Marshal

Despite these successes, the campaign did not go according to plan. The front door was "kicked in", but the Red Army was not destroyed, and the Soviet state did not collapse. Once this became apparent, at the end of July, Hitler and his commanders had to decide how to proceed. Hitler ordered Army Group Centre to pause at Smolensk, while the panzer divisions were shipped to the north and the south.

Although Rundstedt opposed this diversion of forces, he was its beneficiary as attention was shifted to the southern front. He also benefited from disastrous decisions made by the Soviets. On 10 July Stalin appointed his old crony Marshal Semyon Budyonny

Semyon Mikhailovich Budyonnyy ( rus, Семён Миха́йлович Будённый, Semyon Mikháylovich Budyonnyy, p=sʲɪˈmʲɵn mʲɪˈxajləvʲɪdʑ bʊˈdʲɵnːɨj, a=ru-Simeon Budyonniy.ogg; – 26 October 1973) was a Russian ca ...

commander in the Ukraine, with orders to stop the German advance at all costs. Budyonny ordered Kirponos to push his forces forwards to Kiev and Uman

Uman ( uk, Умань, ; pl, Humań; yi, אומאַן) is a city located in Cherkasy Oblast in central Ukraine, to the east of Vinnytsia. Located in the historical region of the eastern Podolia, the city rests on the banks of the Umanka River ...

, despite the danger of encirclement, rather than withdraw and make a stand on the Dnieper. Rundstedt therefore decided to break off the advance towards Kiev, and to direct Kleist's armour south-eastwards, towards Krivoy Rog

Kryvyi Rih ( uk, Криви́й Ріг , lit. "Curved Bend" or "Crooked Horn"), also known as Krivoy Rog (Russian: Кривой Рог) is the largest city in central Ukraine, the 7th most populous city in Ukraine and the 2nd largest by area. Kr ...

. By 30 July the Germans were at Kirovograd, 130 km east of Uman, cutting off the Soviet line of retreat (which had in any case been forbidden by Stalin). Meanwhile, Schobert's 11th Army was advancing north-eastwards from Bessarabia. On 2 August the two armies met, trapping over 100,000 Soviet troops, virtually all of whom were killed or captured. Southern Ukraine was thus left virtually defenceless, and by 25 August, when they entered Dniepropetrovsk

Dnipro, previously called Dnipropetrovsk from 1926 until May 2016, is Ukraine's fourth-largest city, with about one million inhabitants. It is located in the eastern part of Ukraine, southeast of the Ukrainian capital Kyiv on the Dnieper R ...

, the Germans had occupied everything west of the Dnieper (except Odessa

Odesa (also spelled Odessa) is the third most populous city and municipality in Ukraine and a major seaport and transport hub located in the south-west of the country, on the northwestern shore of the Black Sea. The city is also the administrativ ...

, which held out until October). Nevertheless, this had all taken longer than expected, and the Red Army was showing no signs of collapse. Rundstedt wrote to his wife on 12 August: "How much longer? I have no great hope that it will be soon. The distances in Russia devour us."

Neither the success at Uman nor what followed at Kiev would have happened had Rundstedt not backed his subordinates and resisted Hitler's interference in the conduct of the campaign. As during the French campaign, Hitler was panicked by his own success. By early July he was full of anxiety that the German armour was advancing too quickly, without infantry support, and that it was exposed to Soviet counter-attacks. On 10 July Brauchitsch arrived at Rundstedt's headquarters at Brody, with instructions from Hitler that Kleist was turn south towards Vinnitsa and link up with Schobert's army there, rather than continue south-east to Kirovograd. This would still have trapped many Soviet divisions, but it would have allowed the mass of Soviet forces at Uman and Kiev to escape. Rundstedt defended Kleist's ability to execute the larger encirclement, and persuaded Brauchitsch that he was right. Brauchitsch then contacted Halder, who succeeded in persuading Hitler to support Rundstedt. This was a sign that Rundstedt still had Hitler's respect, as were Hitler's two visits to Rundstedt's armies during this period.

After Uman Budyonny's forces massed around Kiev – over 700,000 men – were left dangerously exposed, with Kleist's 1st Panzer Army regrouping to the south-east and General Heinz Guderian's 2nd Panzer Army (part of Army Group Centre) smashing General Yeromenko's Briansk Front and advancing south from Gomel in White Russia

White Russia, White Russian, or Russian White may refer to:

White Russia

*White Ruthenia, a historical reference for a territory in the eastern part of present-day Belarus

* An archaic literal translation for Belarus/Byelorussia/Belorussia

* Ru ...

, on a line well east of Kiev. The danger of encirclement was obvious, but Stalin stubbornly refused to consider withdrawal, despite warnings from both Budyonny and Kirponos that catastrophe was imminent. Budyonny has been freely blamed by postwar writers for the disaster at Kiev, but it is clear that while he was out of his depth as a front commander, he warned Stalin of the danger, and was dismissed for his pains. On 12 September Kleist crossed the Dnieper at Cherkasy heading north-east, and on 16 September his tanks linked up with Guderian's at Lokhvitsa, nearly 200 km east of Kiev. Although many Soviet troops were able to escape eastwards in small groups, around 600,000 men – four whole armies comprising 43 divisions, nearly one-third of the Soviet Army's strength at the start of the war – were killed or captured, and the great majority of those captured died in captivity. Kiev fell on 19 September. Kirponos was killed in action on 20 September, shortly before resistance ceased.

Rundstedt had thus presided over one of the greatest victories in the history of warfare. But this catastrophe for the Red Army resulted far more from the inflexibility of Stalin than it did from the talents of Rundstedt as a commander or the skill of the German Army. David Stahel, a recent historian of the Kiev campaign, wrote: "Germany had been handed a triumph far in excess of what its exhausted armoured forces could have achieved without Stalin's obduracy and incompetence." In fact both the German Army and the Red Army were driven more by the dictates of their respective political masters rather than by the decisions of the military professionals. Stahel sums the situation up with his chapter heading: "Subordinating the generals: the dictators dictate." Kirponos could have withdrawn most of his army across the Dnieper in time had Stalin allowed him to do so, and Rundstedt himself acknowledged this. Had this happened, Rundstedt's forces would have been in no state to give chase: they were exhausted after two months of ceaseless combat. Despite their successes, they had sustained high levels of casualties and even higher levels of loss of equipment, both of which were impossible to replace. By September the German Army in the Soviet Union had suffered nearly 500,000 casualties. In a statement to the Army on 15 August, Rundstedt acknowledged: "It is only natural that such great effort would result in fatigue, the combat strength of the troops has weakened and in many places there is a desire for rest." But, said Rundstedt: "We must keep pressure on the enemy for he has many more reserves than we." This was a remarkable admission so early in the Russian campaign, and it showed that Rundstedt was already well aware of how unrealistic the German belief in a quick victory had been.

Dismissal

Despite the triumph at Kiev, by the end of September Rundstedt was becoming concerned about the state of his command. After three months of continuous fighting, the German armies were exhausted, and the Panzer divisions were in urgent need of new equipment as a result of losses in battle and damage from the poorly-paved Ukrainian roads. As autumn set in, the weather deteriorated, making the situation worse. Rundstedt wanted to halt on the Dnieper for the winter, which would allow the German Army time to rest and be re-equipped. But the German armies could not rest, for fear the Soviet southern armies (now commanded by the stubborn MarshalSemyon Timoshenko

Semyon Konstantinovich Timoshenko (russian: link=no, Семён Константи́нович Тимоше́нко, ''Semyon Konstantinovich Timoshenko''; uk, Семе́н Костянти́нович Тимоше́нко, ''Semen Kostiantyno ...

) would regroup and consolidate a front on the Donets

The Seversky Donets () or Siverskyi Donets (), usually simply called the Donets, is a river on the south of the East European Plain. It originates in the Central Russian Upland, north of Belgorod, flows south-east through Ukraine (Kharkiv, D ...

or the Don. So, soon after the fall of Kiev, the offensive was resumed. Reichenau advanced east towards Kharkov

Kharkiv ( uk, Ха́рків, ), also known as Kharkov (russian: Харькoв, ), is the second-largest city and municipality in Ukraine.

and Kleist and Stülpnagel headed south-east towards the lower Donets. In the south 11th Army and the Romanians (commanded by Manstein following the death of Schobert) advanced along the Sea of Azov

The Sea of Azov ( Crimean Tatar: ''Azaq deñizi''; russian: Азовское море, Azovskoye more; uk, Азовське море, Azovs'ke more) is a sea in Eastern Europe connected to the Black Sea by the narrow (about ) Strait of Ker ...

coast towards Rostov.

The Soviet armies were in a poor state after the catastrophes of Uman and Kiev, and could offer only sporadic resistance, but the German advance was slowed by the autumn rains and the Soviet scorched earth

A scorched-earth policy is a military strategy that aims to destroy anything that might be useful to the enemy. Any assets that could be used by the enemy may be targeted, which usually includes obvious weapons, transport vehicles, commun ...

policy, which denied the Germans food and fuel and forced them to rely on overstretched lines of supply. Rundstedt's armies were also weakened by the transfer of units back to Army Group Centre to take part in the attack on Moscow ( Operation Typhoon). Reichenau did not take Kharkov until 24 October. Nevertheless, during October Rundstedt's forces won another great victory when Manstein and Kleist's tanks reached the Sea of Azov, trapping two Soviet Armies around Mariupol

Mariupol (, ; uk, Маріу́поль ; russian: Мариу́поль) is a city in Donetsk Oblast, Ukraine. It is situated on the northern coast ( Pryazovia) of the Sea of Azov, at the mouth of the Kalmius River. Prior to the 2022 Russia ...

and taking over 100,000 prisoners. This victory enabled Manstein to undertake the conquest of the Crimea

Crimea, crh, Къырым, Qırım, grc, Κιμμερία / Ταυρική, translit=Kimmería / Taurikḗ ( ) is a peninsula in Ukraine, on the northern coast of the Black Sea, that has been occupied by Russia since 2014. It has a p ...

(apart from the fortress city of Sevastopol

Sevastopol (; uk, Севасто́поль, Sevastópolʹ, ; gkm, Σεβαστούπολις, Sevastoúpolis, ; crh, Акъя́р, Aqyár, ), sometimes written Sebastopol, is the largest city in Crimea, and a major port on the Black Sea ...

) against only weak opposition, while Kleist advanced towards Rostov. Despite these defeats, the Red Army was able to fall back on the Don in reasonably good order, and also to evacuate many of the industrial plants of the Donbass.

On 3 November Brauchitsch visited Rundstedt's headquarters at Poltava

Poltava (, ; uk, Полтава ) is a city located on the Vorskla River in central Ukraine. It is the capital city of the Poltava Oblast (province) and of the surrounding Poltava Raion (district) of the oblast. Poltava is administrativel ...

, where Rundstedt told him that the armies must halt and dig in for the winter. But Hitler drove his commanders on, insisting on an advance to the Volga

The Volga (; russian: Во́лга, a=Ru-Волга.ogg, p=ˈvoɫɡə) is the longest river in Europe. Situated in Russia, it flows through Central Russia to Southern Russia and into the Caspian Sea. The Volga has a length of , and a catch ...

and into the North Caucasus

The North Caucasus, ( ady, Темыр Къафкъас, Temır Qafqas; kbd, Ишхъэрэ Къаукъаз, İṩxhərə Qauqaz; ce, Къилбаседа Кавказ, Q̇ilbaseda Kavkaz; , os, Цӕгат Кавказ, Cægat Kavkaz, inh, ...

, to seize the oilfields at Maikop