Geostrategist on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Geostrategy, a subfield of geopolitics, is a type of foreign policy guided principally by geographical factors as they inform, constrain, or affect political and military planning. As with all strategies, geostrategy is concerned with matching means to ends Strategy is as intertwined with

Cosmopolitan Mediation?: Conflict Resolution and the Oslo Accords

', Manchester University Press, 1999, p. 43 thus theoretical formulations in geostrategy usually heavily rely on empirical base although facts-

The most prominent

The most prominent

Influenced by the works of Alfred Thayer Mahan, as well as the German geographers

Influenced by the works of Alfred Thayer Mahan, as well as the German geographers

Turkey, a longtime U.S. ally, now pursues its own path. Guess why.

''

''Democratic Ideals and Reality.''

Washington, DC: National Defense University Press, 1996. * Mahan, Alfred Thayer. ''The Problem of Asia: Its Effects Upon International Politics.'' New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 2003. * Daclon, Corrado Maria. ''Geopolitics of Environment, A Wider Approach to the Global Challenges.'' Italy: Comunità Internazionale, SIOI, 2007. * Efremenko, Dmitry V

''Russian Geostrategic Imperatives. Collection of Essays.''

Moscow: Russian Academy of Sciences, Institute of Scientific Information for Social Sciences, 2019.

European Geostrategy

Ukrainian Geostrategy

* The GeGaLo index of geopolitical gains and losses assesses how the geopolitical position of 156 countries may change if the world fully transitions to renewable energy resources. Former fossil fuels exporters are expected to lose power, while the positions of former fossil fuel importers and countries rich in renewable energy resources is expected to strengthen.{{Cite journal, last1=Overland, first1=Indra, last2=Bazilian, first2=Morgan, last3=Ilimbek Uulu, first3=Talgat, last4=Vakulchuk, first4=Roman, last5=Westphal, first5=Kirsten, date=2019, title=The GeGaLo index: Geopolitical gains and losses after energy transition, journal=Energy Strategy Reviews, language=en, volume=26, pages=100406, doi=10.1016/j.esr.2019.100406, doi-access=free Geopolitics Strategy

geography

Geography (from Greek: , ''geographia''. Combination of Greek words ‘Geo’ (The Earth) and ‘Graphien’ (to describe), literally "earth description") is a field of science devoted to the study of the lands, features, inhabitants, an ...

as geography is with nation

A nation is a community of people formed on the basis of a combination of shared features such as language, history, ethnicity, culture and/or society. A nation is thus the collective identity of a group of people understood as defined by th ...

hood, or as Colin S. Gray and Geoffrey Sloan state it, " eography isthe mother of strategy."

Geostrategists, as distinct from geopoliticians, approach geopolitics from a nationalist

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: Th ...

point of view. Geostrategies are relevant principally to the context in which they were devised: the strategist's nation, the historically rooted national impulses, the strength of the country's resources, the scope of the country's goals, the political geography of the time period, and the technological factors that affect military, political, economic, and cultural engagement. Geostrategy can function prescriptively, advocating foreign policy based on geographic and historical factors, analytically, describing how foreign policy is shaped by geography and history, or predictively, projecting a country's future foreign policy decisions and outcomes.

Many geostrategists are also geographers, specializing in subfields of geography

Geography (from Greek: , ''geographia''. Combination of Greek words ‘Geo’ (The Earth) and ‘Graphien’ (to describe), literally "earth description") is a field of science devoted to the study of the lands, features, inhabitants, an ...

, such as human geography

Human geography or anthropogeography is the branch of geography that studies spatial relationships between human communities, cultures, economies, and their interactions with the environment. It analyzes spatial interdependencies between social ...

, political geography, economic geography

Economic geography is the subfield of human geography which studies economic activity and factors affecting them. It can also be considered a subfield or method in economics.

There are four branches of economic geography.

There is,

primary sect ...

, cultural geography, military geography, and strategic geography. Geostrategy is most closely related to strategic geography.

Especially following World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, some scholars divide geostrategy into two schools: the uniquely German organic state theory; and, the broader Anglo-American

Anglo-Americans are people who are English-speaking inhabitants of Anglo-America. It typically refers to the nations and ethnic groups in the Americas that speak English as a native language, making up the majority of people in the world who spe ...

geostrategies.

Definition

Most definitions of geostrategy below emphasize the merger ofstrategic

Strategy (from Greek στρατηγία ''stratēgia'', "art of troop leader; office of general, command, generalship") is a general plan to achieve one or more long-term or overall goals under conditions of uncertainty. In the sense of the "art ...

considerations with geopolitical factors. While geopolitics is ostensibly neutral — examining the geographic and political features of different regions, especially the impact of geography on politics — geostrategy involves comprehensive planning, assigning means for achieving national goals or securing assets of military

A military, also known collectively as armed forces, is a heavily armed, highly organized force primarily intended for warfare. It is typically authorized and maintained by a sovereign state, with its members identifiable by their distinct ...

or political significance.

Original definition

The term "geo-strategy" was first used by Frederick L. Schuman in his 1942 article "Let Us Learn Our Geopolitics." It was a translation of theGerman

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

term "''Wehrgeopolitik''" as used by German geostrategist Karl Haushofer. Previous translations had been attempted, such as "defense-geopolitics". Robert Strausz-Hupé had coined and popularized "war geopolitics" as another alternate translation.

Modern definitions

Theory and methodology

As a science or science based political practice geostrategy uses factual andempirical analysis

In philosophy, empiricism is an epistemological theory that holds that knowledge or justification comes only or primarily from sensory experience. It is one of several views within epistemology, along with rationalism and skepticism. Empiric ...

,Deiniol Jones, Cosmopolitan Mediation?: Conflict Resolution and the Oslo Accords

', Manchester University Press, 1999, p. 43 thus theoretical formulations in geostrategy usually heavily rely on empirical base although facts-

value

Value or values may refer to:

Ethics and social

* Value (ethics) wherein said concept may be construed as treating actions themselves as abstract objects, associating value to them

** Values (Western philosophy) expands the notion of value beyo ...

s relations or conclusions are differently observed by different and/or competitive geostrategic approaches. Geostrategic conceptions that stems from the theory become base for the countries foreign and international policies. Geostrategic conceptions are also historically acquired or even inherited from one country to another due to common history, relations between the countries, culture and even propaganda.

The geostrategy of location include river valleys, inland sea, world ocean, world island, and so on. For instance, the start of Western civilization was located in the river valleys of the Nile

The Nile, , Bohairic , lg, Kiira , Nobiin: Áman Dawū is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa and has historically been considered the longest riv ...

in Egypt and the Tigris

The Tigris () is the easternmost of the two great rivers that define Mesopotamia, the other being the Euphrates. The river flows south from the mountains of the Armenian Highlands through the Syrian and Arabian Deserts, and empties into the ...

and Euphrates

The Euphrates () is the longest and one of the most historically important rivers of Western Asia. Tigris–Euphrates river system, Together with the Tigris, it is one of the two defining rivers of Mesopotamia ( ''the land between the rivers'') ...

in Mesopotamia. The Nile and Tigris and Euphrates not only provided the fertile soil for crop production, but also allowed for the floods that taxed the ingenuity of the inhabitants. The climate of the area was conducive to an existence based primarily upon agriculture. The rivers also provided the avenues of trade in a period when muscles of man and the winds of the sky were the motive power of ships. The river valleys became a unifying factor in the political development of the people.

History

Precursors

As early asHerodotus

Herodotus ( ; grc, , }; BC) was an ancient Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus, part of the Persian Empire (now Bodrum, Turkey) and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria (Italy). He is known fo ...

, observers saw strategy as heavily influenced by the geographic setting of the actors. In ''History

History (derived ) is the systematic study and the documentation of the human activity. The time period of event before the invention of writing systems is considered prehistory. "History" is an umbrella term comprising past events as well ...

'', Herodotus describes a clash of civilizations between the Egyptians, Persians

The Persians are an Iranian ethnic group who comprise over half of the population of Iran. They share a common cultural system and are native speakers of the Persian language as well as of the languages that are closely related to Persian. ...

, Scythia

Scythia ( Scythian: ; Old Persian: ; Ancient Greek: ; Latin: ) or Scythica (Ancient Greek: ; Latin: ), also known as Pontic Scythia, was a kingdom created by the Scythians during the 6th to 3rd centuries BC in the Pontic–Caspian steppe.

...

ns, and Greeks

The Greeks or Hellenes (; el, Έλληνες, ''Éllines'' ) are an ethnic group and nation indigenous to the Eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea regions, namely Greece, Cyprus, Albania, Italy, Turkey, Egypt, and, to a lesser extent, ot ...

—all of which he believed were heavily influenced by the physical geographic setting.

Dietrich Heinrich von Bülow Dietrich Heinrich Freiherr von Bülow (1757–1807) was a Prussian soldier and military writer, and brother of General Count Friedrich Wilhelm Bülow.

Early career

Von Bülow entered the Prussian army in 1773. Routine work proved distasteful to hi ...

proposed a geometrical science of strategy in the 1799 ''The Spirit of the Modern System of War.'' His system predicted that the larger states would swallow the smaller ones, resulting in eleven large states. Mackubin Thomas Owens

Mackubin Thomas Owens is a senior fellow at the Foreign Policy Research Institute. From 2015 until 2018, he served as dean of academic affairs at the Institute of World Politics. He was previously the associate dean of academics for electives and d ...

notes the similarity between von Bülow's predictions and the map of Europe after the unification of Germany and of Italy.

Golden age

Between 1890 and 1919 the world became a geostrategist's paradise, leading to the formulation of the classical geopolitical theories. The international system featured rising and fallinggreat power

A great power is a sovereign state that is recognized as having the ability and expertise to exert its influence on a global scale. Great powers characteristically possess military and economic strength, as well as diplomatic and soft power i ...

s, many with global reach. There were no new frontiers for the great powers to explore

Exploration refers to the historical practice of discovering remote lands. It is studied by geographers and historians.

Two major eras of exploration occurred in human history: one of convergence, and one of divergence. The first, covering most ...

or colonize

Colonization, or colonisation, constitutes large-scale population movements wherein migrants maintain strong links with their, or their ancestors', former country – by such links, gain advantage over other inhabitants of the territory. When ...

—the entire world was divided between the empires and colonial powers. From this point forward, international politics would feature the struggles of state against state.

Two strains of geopolitical thought gained prominence: an Anglo-American school, and a German school. Alfred Thayer Mahan and Halford J. Mackinder

Sir Halford John Mackinder (15 February 1861 – 6 March 1947) was an English geographer, academic and politician, who is regarded as one of the founding fathers of both geopolitics and geostrategy. He was the first Principal of University Ex ...

outlined the American and British conceptions of geostrategy, respectively, in their works ''The Problem of Asia'' and "'' The Geographical Pivot of History''". Friedrich Ratzel and Rudolf Kjellén

Johan Rudolf Kjellén (, 13 June 1864, in Torsö – 14 November 1922, in Uppsala) was a Swedish political scientist, geographer and politician who first coined the term "geopolitics". His work was influenced by Friedrich Ratzel. Along with Alexa ...

developed an organic theory of the state

Geopolitik is a branch of 19th-century German statecraft, foreign policy and geostrategy.

It developed from the writings of various German philosophers, geographers and thinkers, including Oswald Spengler (1880-1936), Alexander Humboldt (176 ...

which laid the foundation for Germany's unique school of geostrategy.

World War II

The most prominent

The most prominent German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

geopolitician was General Karl Haushofer. After World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, during the Allied occupation of Germany, the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

investigated many officials and public figures to determine if they should face charges of war crimes at the Nuremberg trials

The Nuremberg trials were held by the Allies of World War II, Allies against representatives of the defeated Nazi Germany, for plotting and carrying out invasions of other countries, and other crimes, in World War II.

Between 1939 and 1945 ...

. Haushofer, an academic primarily, was interrogated by Father Edmund A. Walsh

Fr. Edmund Aloysius Walsh, S.J. (October 10, 1885 – October 31, 1956) was an American Jesuit Catholic priest, author, professor of geopolitics and founder of the Georgetown University School of Foreign Service, the first school for interna ...

, a professor of geopolitics from the Georgetown School of Foreign Service, at the request of the U.S. authorities. Despite his involvement in crafting one of the justifications for Nazi aggression, Fr. Walsh determined that Haushofer ought not stand trial.

Cold War

After theSecond World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

, the term "geopolitics" fell into disrepute, because of its association with Nazi

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in ...

'' geopolitik''. Virtually no books published between the end of World War II and the mid-1970s used the word "geopolitics" or "geostrategy" in their titles, and geopoliticians did not label themselves or their works as such. German theories prompted a number of critical examinations of ''geopolitik'' by American geopoliticians such as Robert Strausz-Hupé, Derwent Whittlesey and Andrew Gyorgy.

As the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because t ...

began, N.J. Spykman and George F. Kennan

George Frost Kennan (February 16, 1904 – March 17, 2005) was an American diplomat and historian. He was best known as an advocate of a policy of containment of Soviet expansion during the Cold War. He lectured widely and wrote scholarly hist ...

laid down the foundations for the U.S. policy of containment

Containment was a geopolitical strategic foreign policy pursued by the United States during the Cold War to prevent the spread of communism after the end of World War II. The name was loosely related to the term '' cordon sanitaire'', which ...

, which would dominate Western geostrategic thought for the next forty years.

Alexander de Seversky

Alexander Nikolaievich Prokofiev de Seversky (russian: link=no, Алекса́ндр Никола́евич Проко́фьев-Се́верский) (June 7, 1894 – August 24, 1974) was a Russian-American aviation pioneer, inventor, and in ...

would propose that airpower had fundamentally changed geostrategic considerations and thus proposed a "geopolitics of airpower." His ideas had some influence on the administration of President Dwight D. Eisenhower, but the ideas of Spykman and Kennan would exercise greater weight. Later during the Cold War, Colin Gray would decisively reject the idea that airpower changed geostrategic considerations, while Saul B. Cohen examined the idea of a "shatterbelt", which would eventually inform the domino theory.

Post-Cold War

After the Cold War ended, states started preferring management of space at low cost to expansion of it with military force. Use of military force in order to secure space causes not only great burden on countries, but also severe criticism from the international society as interdependence between countries continuously increases. As a way of new space management, countries either created regional institutions related to the space or makeregimes

In politics, a regime (also "régime") is the form of government or the set of rules, cultural or social norms, etc. that regulate the operation of a government or institution and its interactions with society. According to Yale professor Juan Jo ...

on specific issues to allow intervention on space. Such mechanisms let countries to have indirect control over space. The indirect space management reduces required capital and at the same time provides justification and legitimacy of the management, that the countries involved do not have to face criticism from the international society.

Notable geostrategists

The below geostrategists were instrumental in founding and developing the major geostrategic doctrines in the discipline's history. While there have been many other geostrategists, these have been the most influential in shaping and developing the field as a whole.Alfred Thayer Mahan

Alfred Thayer Mahan was anAmerican Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

officer and president of the U.S. Naval War College. He is best known for his '' Influence of Sea Power upon History'' series of books, which argued that naval supremacy was the deciding factor in great power

A great power is a sovereign state that is recognized as having the ability and expertise to exert its influence on a global scale. Great powers characteristically possess military and economic strength, as well as diplomatic and soft power i ...

warfare. In 1900, Mahan's book ''The Problem of Asia'' was published. In this volume he laid out the first geostrategy of the modern era.

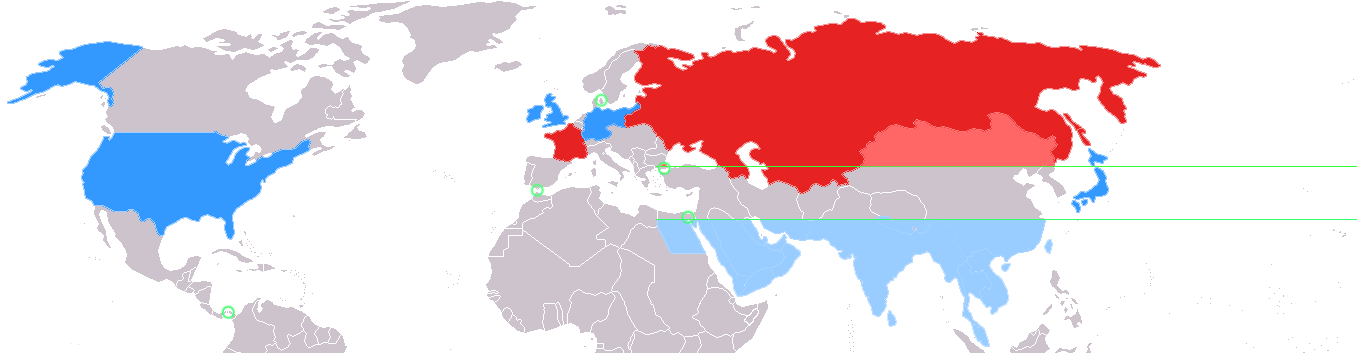

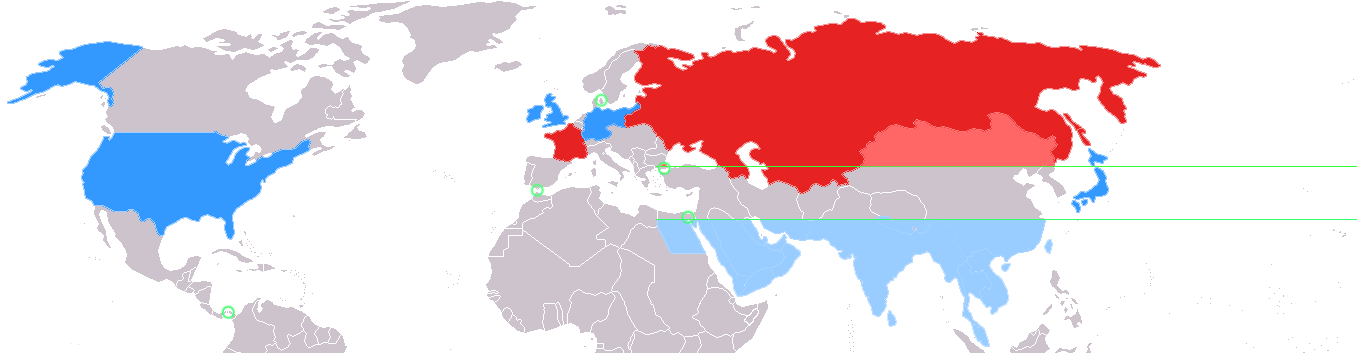

The ''Problem of Asia'' divides the continent of Asia into 3 zones:

* A northern zone, located above the 40th parallel north, characterized by its cold climate, and dominated by land power;

* The "Debatable and Debated" zone, located between the 40th and 30th parallels, characterized by a temperate climate; and,

* A southern zone, located below the 30th parallel north, characterized by its hot climate, and dominated by sea power.

The Debated and Debatable zone, Mahan observed, contained two peninsulas on either end (Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

and the Korean Peninsula

Korea ( ko, 한국, or , ) is a peninsular region in East Asia. Since 1945, it has been divided at or near the 38th parallel, with North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea) comprising its northern half and South Korea (Republic ...

), the Suez Canal, Palestine, Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

, Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the ...

, two countries marked by their mountain ranges (Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

and Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan,; prs, امارت اسلامی افغانستان is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. Referred to as the Heart of Asia, it is borde ...

), the Pamir Mountains, the Himalayas

The Himalayas, or Himalaya (; ; ), is a mountain range in Asia, separating the plains of the Indian subcontinent from the Tibetan Plateau. The range has some of the planet's highest peaks, including the very highest, Mount Everest. Over 10 ...

, the Yangtze

The Yangtze or Yangzi ( or ; ) is the longest river in Asia, the third-longest in the world, and the longest in the world to flow entirely within one country. It rises at Jari Hill in the Tanggula Mountains (Tibetan Plateau) and flows ...

, and Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the n ...

. Within this zone, Mahan asserted that there were no strong states capable of withstanding outside influence or capable even of maintaining stability within their own borders. So whereas the political situations to the north and south were relatively stable and determined, the middle remained "debatable and debated ground."

North of the 40th parallel, the vast expanse of Asia was dominated by the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War ...

. Russia possessed a central position on the continent, and a wedge-shaped projection into Central Asia

Central Asia, also known as Middle Asia, is a region of Asia that stretches from the Caspian Sea in the west to western China and Mongolia in the east, and from Afghanistan and Iran in the south to Russia in the north. It includes the fo ...

, bounded by the Caucasus Mountains

The Caucasus Mountains,

: pronounced

* hy, Կովկասյան լեռներ,

: pronounced

* az, Qafqaz dağları, pronounced

* rus, Кавка́зские го́ры, Kavkázskiye góry, kɐfˈkasːkʲɪje ˈɡorɨ

* tr, Kafkas Dağla ...

and Caspian Sea

The Caspian Sea is the world's largest inland body of water, often described as the world's largest lake or a full-fledged sea. An endorheic basin, it lies between Europe and Asia; east of the Caucasus, west of the broad steppe of Central A ...

on one side and the mountains of Afghanistan and Western China on the other side. To prevent Russian expansionism and achievement of predominance on the Asian continent, Mahan believed pressure on Asia's flanks could be the only viable strategy pursued by sea powers.

South of the 30th parallel lay areas dominated by the sea powers – the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and ...

, the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

, Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwee ...

and Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the n ...

. To Mahan, the possession of India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area, the List of countries and dependencies by population, second-most populous ...

by the United Kingdom was of key strategic importance, as India was best suited for exerting balancing pressure against Russia in Central Asia. The United Kingdom's predominance in Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning the North Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via a land bridg ...

, China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, most populous country, with a Population of China, population exceeding 1.4 billion, slig ...

, Malaysia

Malaysia ( ; ) is a country in Southeast Asia. The federal constitutional monarchy consists of thirteen states and three federal territories, separated by the South China Sea into two regions: Peninsular Malaysia and Borneo's East Mal ...

, Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands. With an area of , Australia is the largest country by ...

, Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by to ...

and South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring coun ...

was also considered important.

The strategy of sea powers, according to Mahan, ought to be to deny Russia the benefits of commerce that come from sea commerce. He noted that both the Turkish Straits and Danish Straits could be closed by a hostile power, thereby denying Russia access to the sea. Further, this disadvantageous position would reinforce Russia's proclivity toward expansionism in order to obtain wealth or warm water ports. Natural geographic targets for Russian expansionism in search of access to the sea would therefore be the Chinese seaboard, the Persian Gulf

The Persian Gulf ( fa, خلیج فارس, translit=xalij-e fârs, lit=Gulf of Fars, ), sometimes called the ( ar, اَلْخَلِيْجُ ٱلْعَرَبِيُّ, Al-Khalīj al-ˁArabī), is a mediterranean sea in Western Asia. The bo ...

, and Asia Minor.

In this contest between land power and sea power, Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-ei ...

would find itself allied with France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

(a natural sea power, but in this case necessarily acting as a land power), arrayed against Germany, Britain, Japan, and the United States as sea powers. Further, Mahan conceived of a unified, modern state composed of Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with a small portion on the Balkan Peninsula ...

, Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

, and Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the ...

, possessing an efficiently organized army and navy to stand as a counterweight to Russian expansion.

Further dividing the map by geographic features, Mahan stated that the two most influential lines of division would be the Suez Canal and Panama Canal

The Panama Canal ( es, Canal de Panamá, link=no) is an artificial waterway in Panama that connects the Atlantic Ocean with the Pacific Ocean and divides North and South America. The canal cuts across the Isthmus of Panama and is a condui ...

. As most developed nations and resources lay above the North–South divide, politics and commerce north of the two canals would be of much greater importance than those occurring south of the canals. As such, the great progress of historical development would not flow from north to south, but from east to west, in this case leading toward Asia as the locus of advance.

Halford J. Mackinder

Halford J. Mackinder

Sir Halford John Mackinder (15 February 1861 – 6 March 1947) was an English geographer, academic and politician, who is regarded as one of the founding fathers of both geopolitics and geostrategy. He was the first Principal of University Ex ...

's major work, Democratic ideals and reality: a study in the politics of reconstruction, appeared in 1919. 2It presented his theory of the Heartland and made a case for fully taking into account geopolitical factors at the Paris Peace conference and contrasted (geographical) reality with Woodrow Wilson's idealism. The book's most famous quote was: "Who rules East Europe commands the Heartland; Who rules the Heartland commands the World Island; Who rules the World Island commands the World."

This message was composed to convince the world statesmen at the Paris Peace conference of the crucial importance of Eastern Europe as the strategic route to the Heartland was interpreted as requiring a strip of buffer state to separate Germany and Russia. These were created by the peace negotiators but proved to be ineffective bulwarks in 1939 (although this may be seen as a failure of other, later statesmen during the interbellum). The principal concern of his work was to warn of the possibility of another major war (a warning also given by economist John Maynard Keynes).

Mackinder was anti-Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

, and as British High Commissioner in Southern Russia in late 1919 and early 1920, he stressed the need for Britain to continue her support to the White Russian forces, which he attempted to unite.

Mackinder's work paved the way for the establishment of geography as a distinct discipline in the United Kingdom. His role in fostering the teaching of geography is probably greater than that of any other single British geographer.

Whilst Oxford did not appoint a professor of Geography until 1934, both the University of Liverpool and University of Wales, Aberystwyth established professorial chairs in Geography in 1917. Mackinder himself became a full professor in Geography in the University of London (London School of Economics

, mottoeng = To understand the causes of things

, established =

, type = Public research university

, endowment = £240.8 million (2021)

, budget = £391.1 milli ...

) in 1923.

Mackinder is often credited with introducing two new terms into the English language: "manpower" and "heartland".

The Heartland Theory was enthusiastically taken up by the German school of Geopolitik, in particular by its main proponent Karl Haushofer. Geopolitik was later embraced by the German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

Nazi

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in ...

regime in the 1930s. The German interpretation of the Heartland Theory is referred to explicitly (without mentioning the connection to Mackinder) in ''The Nazis Strike

''The Nazis Strike'' is the second film of Frank Capra's ''Why We Fight'' propaganda film series. It introduces Germany as a nation whose aggressive ambitions began in 1863 with Otto von Bismarck and the Nazis as its latest incarnation.

Heartland ...

'', the second of Frank Capra's " Why We Fight" series of American

American(s) may refer to:

* American, something of, from, or related to the United States of America, commonly known as the "United States" or "America"

** Americans, citizens and nationals of the United States of America

** American ancestry, pe ...

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

propaganda films.

The Heartland Theory and more generally classical geopolitics and geostrategy were extremely influential in the making of US strategic policy during the period of the Cold War.

Evidence of Mackinder's Heartland Theory can be found in the works of geopolitician Dimitri Kitsikis

Dimitri Kitsikis ( el, Δημήτρης Κιτσίκης; 2 June 1935 – 28 August 2021) was a Greek Turkologist, Sinologist and Professor of International Relations and Geopolitics. He also published poetry in French and Greek.

Life

Dimitri ...

, particularly in his geopolitical model " Intermediate Region".

Friedrich Ratzel

Influenced by the works of Alfred Thayer Mahan, as well as the German geographers

Influenced by the works of Alfred Thayer Mahan, as well as the German geographers Carl Ritter

Carl Ritter (August 7, 1779September 28, 1859) was a German geographer. Along with Alexander von Humboldt, he is considered one of the founders of modern geography. From 1825 until his death, he occupied the first chair in geography at the Univer ...

and Alexander von Humboldt

Friedrich Wilhelm Heinrich Alexander von Humboldt (14 September 17696 May 1859) was a German polymath, geographer, naturalist, explorer, and proponent of Romantic philosophy and science. He was the younger brother of the Prussian minister ...

, Friedrich Ratzel would lay the foundations for '' geopolitik'', Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwee ...

's unique strain of geopolitics.

Ratzel wrote on the natural division between land powers and sea power

Command of the sea (also called control of the sea or sea control) is a naval military concept regarding the strength of a particular navy to a specific naval area it controls. A navy has command of the sea when it is so strong that its rivals ...

s, agreeing with Mahan that sea power was self-sustaining, as the profit from trade

Trade involves the transfer of goods and services from one person or entity to another, often in exchange for money. Economists refer to a system or network that allows trade as a market.

An early form of trade, barter, saw the direct exc ...

would support the development of a merchant marine. However, his key contribution were the development of the concepts of '' raum'' and the organic theory of the state

Geopolitik is a branch of 19th-century German statecraft, foreign policy and geostrategy.

It developed from the writings of various German philosophers, geographers and thinkers, including Oswald Spengler (1880-1936), Alexander Humboldt (176 ...

. He theorized that states were organic

Organic may refer to:

* Organic, of or relating to an organism, a living entity

* Organic, of or relating to an anatomical organ

Chemistry

* Organic matter, matter that has come from a once-living organism, is capable of decay or is the product ...

and growing, and that border

Borders are usually defined as geographical boundaries, imposed either by features such as oceans and terrain, or by political entities such as governments, sovereign states, federated states, and other subnational entities. Political borders ca ...

s were only temporary, representing pauses in their natural movement. ''Raum'' was the land, spiritually connected to a nation

A nation is a community of people formed on the basis of a combination of shared features such as language, history, ethnicity, culture and/or society. A nation is thus the collective identity of a group of people understood as defined by th ...

(in this case, the German peoples), from which the people could draw sustenance, find adjacent inferior nations which would support them, and which would be fertilized by their ''kultur'' (culture).

Ratzel's ideas would influence the works of his student Rudolf Kjellén, as well as those of General Karl Haushofer.

Rudolf Kjellén

Rudolf Kjellén

Johan Rudolf Kjellén (, 13 June 1864, in Torsö – 14 November 1922, in Uppsala) was a Swedish political scientist, geographer and politician who first coined the term "geopolitics". His work was influenced by Friedrich Ratzel. Along with Alexa ...

was a Swedish political scientist and student of Friedrich Ratzel. He first coined the term "geopolitics." His writings would play a decisive role in influencing General Karl Haushofer's ''geopolitik'', and indirectly the future Nazi

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in ...

foreign policy.

His writings focused on five central concepts that would underlie German ''geopolitik'':

# ''Reich'' was a territorial concept that was composed of ''Raum'' (''Lebensraum

(, ''living space'') is a German concept of settler colonialism, the philosophy and policies of which were common to German politics from the 1890s to the 1940s. First popularized around 1901, '' lso in:' became a geopolitical goal of Imper ...

''), and strategic military shape;

# ''Volk

The German noun ''Volk'' () translates to people,

both uncountable in the sense of ''people'' as in a crowd, and countable (plural ''Völker'') in the sense of '' a people'' as in an ethnic group or nation (compare the English term '' folk ...

'' was a racial conception of the state;

# ''Haushalt'' was a call for autarky based on land, formulated in reaction to the vicissitudes of international markets

Globalization, or globalisation (Commonwealth English; see spelling differences), is the process of interaction and integration among people, companies, and governments worldwide. The term ''globalization'' first appeared in the early 20t ...

;

# ''Gesellschaft'' was the social aspect of a nation's organization and cultural appeal, Kjellén anthropomorphizing inter-state relations more than Ratzel had; and,

# ''Regierung'' was the form of government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive, and judiciary. Government i ...

whose bureaucracy

The term bureaucracy () refers to a body of non-elected governing officials as well as to an administrative policy-making group. Historically, a bureaucracy was a government administration managed by departments staffed with non-elected offi ...

and army

An army (from Old French ''armee'', itself derived from the Latin verb ''armāre'', meaning "to arm", and related to the Latin noun ''arma'', meaning "arms" or "weapons"), ground force or land force is a fighting force that fights primarily on ...

would contribute to the people's pacification and coordination.

General Karl Haushofer

Karl Haushofer's geopolitik expanded upon that of Ratzel and Kjellén. While the latter two conceived of geopolitik as the state-as-an-organism-in-space put to the service of a leader, Haushofer's Munich school specifically studied geography as it related to war and designs for empire. The behavioral rules of previous geopoliticians were thus turned into dynamic normative doctrines for action on lebensraum and world power. Haushofer defined geopolitik in 1935 as "the duty to safeguard the right to the soil, to the land in the widest sense, not only the land within the frontiers of the Reich, but the right to the more extensive Volk and cultural lands." Culture itself was seen as the most conducive element to dynamic expansion. Culture provided a guide as to the best areas for expansion, and could make expansion safe, whereas solely military or commercial power could not. To Haushofer, the existence of a state depended on living space, the pursuit of which must serve as the basis for all policies. Germany had a highpopulation density

Population density (in agriculture: standing stock or plant density) is a measurement of population per unit land area. It is mostly applied to humans, but sometimes to other living organisms too. It is a key geographical term.Matt RosenberPopu ...

, whereas the old colonial powers had a much lower density: a virtual mandate for German expansion into resource-rich areas. A buffer zone of territories or insignificant states on one's borders would serve to protect Germany.

Closely linked to this need was Haushofer's assertion that the existence of small states was evidence of political regression and disorder in the international system. The small states surrounding Germany ought to be brought into the vital German order. These states were seen as being too small to maintain practical autonomy (even if they maintained large colonial possessions) and would be better served by protection and organization within Germany. In Europe, he saw Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to ...

, the Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

, Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, República Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of th ...

, Denmark

)

, song = ( en, "King Christian stood by the lofty mast")

, song_type = National and royal anthem

, image_map = EU-Denmark.svg

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of Denmark

, establish ...

, Switzerland

). Swiss law does not designate a ''capital'' as such, but the federal parliament and government are installed in Bern, while other federal institutions, such as the federal courts, are in other cities (Bellinzona, Lausanne, Luzern, Neuchâtel ...

, Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders wi ...

and the "mutilated alliance" of Austro-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe

Central Europe is an area of Europe between Western Europe and Eastern ...

as supporting his assertion.

Haushofer and the Munich school of geopolitik would eventually expand their conception of lebensraum and autarky well past a restoration of the German borders of 1914 and "a place in the sun." They set as goals a New European Order, then a New Afro-European Order, and eventually to a Eurasian Order. This concept became known as a pan-region, taken from the American Monroe Doctrine, and the idea of national and continental self-sufficiency. This was a forward-looking refashioning of the drive for colonies, something that geopoliticians did not see as an economic necessity, but more as a matter of prestige, and of putting pressure on older colonial powers. The fundamental motivating force was not be economic, but cultural and spiritual.

Beyond being an economic concept, pan-regions were a strategic concept as well. Haushofer acknowledged the strategic concept of the Heartland

Heartland or Heartlands may refer to:

Businesses and organisations

* Heartland Bank, a New Zealand-based financial institution

* Heartland Inn, a chain of hotels based in Iowa, United States

* Heartland Alliance, an anti-poverty organization ...

put forward by the Halford Mackinder. If Germany could control Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural, and socio-economic connotations. The vast majority of the region is covered by Russia, whi ...

and subsequently Russian territory, it could control a strategic area to which hostile sea power

Command of the sea (also called control of the sea or sea control) is a naval military concept regarding the strength of a particular navy to a specific naval area it controls. A navy has command of the sea when it is so strong that its rivals ...

could be denied. Allying with Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

and Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the n ...

would further augment German strategic control of Eurasia, with those states becoming the naval arms protecting Germany's insular position.

Nicholas J. Spykman

Nicholas J. Spykman was a Dutch-American geostrategist, known as the "godfather ofcontainment

Containment was a geopolitical strategic foreign policy pursued by the United States during the Cold War to prevent the spread of communism after the end of World War II. The name was loosely related to the term '' cordon sanitaire'', which ...

." His geostrategic work, ''The Geography of the Peace'' (1944), argued that the balance of power in Eurasia

Eurasia (, ) is the largest continental area on Earth, comprising all of Europe and Asia. Primarily in the Northern and Eastern Hemispheres, it spans from the British Isles and the Iberian Peninsula in the west to the Japanese archipelag ...

directly affected United States security.

N.J. Spykman based his geostrategic ideas on those of Sir Halford Mackinder's Heartland theory. Spykman's key contribution was to alter the strategic valuation of the Heartland vs. the "Rimland" (a geographic area analogous to Mackinder's "Inner or Marginal Crescent"). Spykman does not see the heartland as a region which will be unified by powerful transport or communication

Communication (from la, communicare, meaning "to share" or "to be in relation with") is usually defined as the transmission of information. The term may also refer to the message communicated through such transmissions or the field of inqui ...

infrastructure in the near future. As such, it won't be in a position to compete with the United States' sea power

Command of the sea (also called control of the sea or sea control) is a naval military concept regarding the strength of a particular navy to a specific naval area it controls. A navy has command of the sea when it is so strong that its rivals ...

, despite its uniquely defensive position. The rimland possessed all of the key resources and populations—its domination was key to the control of Eurasia. His strategy was for Offshore powers, and perhaps Russia as well, to resist the consolidation of control over the rimland by any one power. Balanced power would lead to peace.

George F. Kennan

George F. Kennan

George Frost Kennan (February 16, 1904 – March 17, 2005) was an American diplomat and historian. He was best known as an advocate of a policy of containment of Soviet expansion during the Cold War. He lectured widely and wrote scholarly hist ...

, U.S. ambassador to the Soviet Union, laid out the seminal Cold War geostrategy in his ''Long Telegram

The "X Article" is an article, formally titled "The Sources of Soviet Conduct", written by George F. Kennan and published under the pseudonym "X" in the July 1947 issue of ''Foreign Affairs'' magazine. The article widely introduced the term " ...

'' and ''The Sources of Soviet Conduct

The "X Article" is an article, formally titled "The Sources of Soviet Conduct", written by George F. Kennan and published under the pseudonym "X" in the July 1947 issue of ''Foreign Affairs'' magazine. The article widely introduced the term " ...

''. He coined the term "containment

Containment was a geopolitical strategic foreign policy pursued by the United States during the Cold War to prevent the spread of communism after the end of World War II. The name was loosely related to the term '' cordon sanitaire'', which ...

", which would become the guiding idea for U.S. grand strategy

Grand strategy or high strategy is a state's strategy of how means can be used to advance and achieve national interests. Issues of grand strategy typically include the choice of primary versus secondary theaters in war, distribution of resource ...

over the next forty years, although the term would come to mean something significantly different from Kennan's original formulation.

Kennan advocated what was called "strongpoint containment." In his view, the United States and its allies needed to protect the productive industrial areas of the world from Soviet domination. He noted that of the five centers of industrial strength in the world—the United States, Britain, Japan, Germany, and Russia—the only contested area was that of Germany. Kennan was concerned about maintaining the balance of power between the U.S. and the USSR

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nati ...

, and in his view, only these few industrialized areas mattered.

Here Kennan differed from Paul Nitze, whose seminal Cold War document, NSC 68 United States Objectives and Programs for National Security, better known as NSC68, was a 66-page top secret National Security Council (NSC) policy paper drafted by the Department of State and Department of Defense and presented to President Har ...

, called for "undifferentiated or global containment," along with a massive military buildup. Kennan saw the Soviet Union as an ideological and political challenger rather than a true military threat. There was no reason to fight the Soviets throughout Eurasia

Eurasia (, ) is the largest continental area on Earth, comprising all of Europe and Asia. Primarily in the Northern and Eastern Hemispheres, it spans from the British Isles and the Iberian Peninsula in the west to the Japanese archipelag ...

, because those regions were not productive, and the Soviet Union was already exhausted from World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, limiting its ability to project power abroad. Therefore, Kennan disapproved of U.S. involvement in Vietnam

Vietnam or Viet Nam ( vi, Việt Nam, ), officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam,., group="n" is a country in Southeast Asia, at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of and population of 96 million, making ...

, and later spoke out critically against Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan ( ; February 6, 1911June 5, 2004) was an American politician, actor, and union leader who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He also served as the 33rd governor of California from 1967 ...

's military buildup.

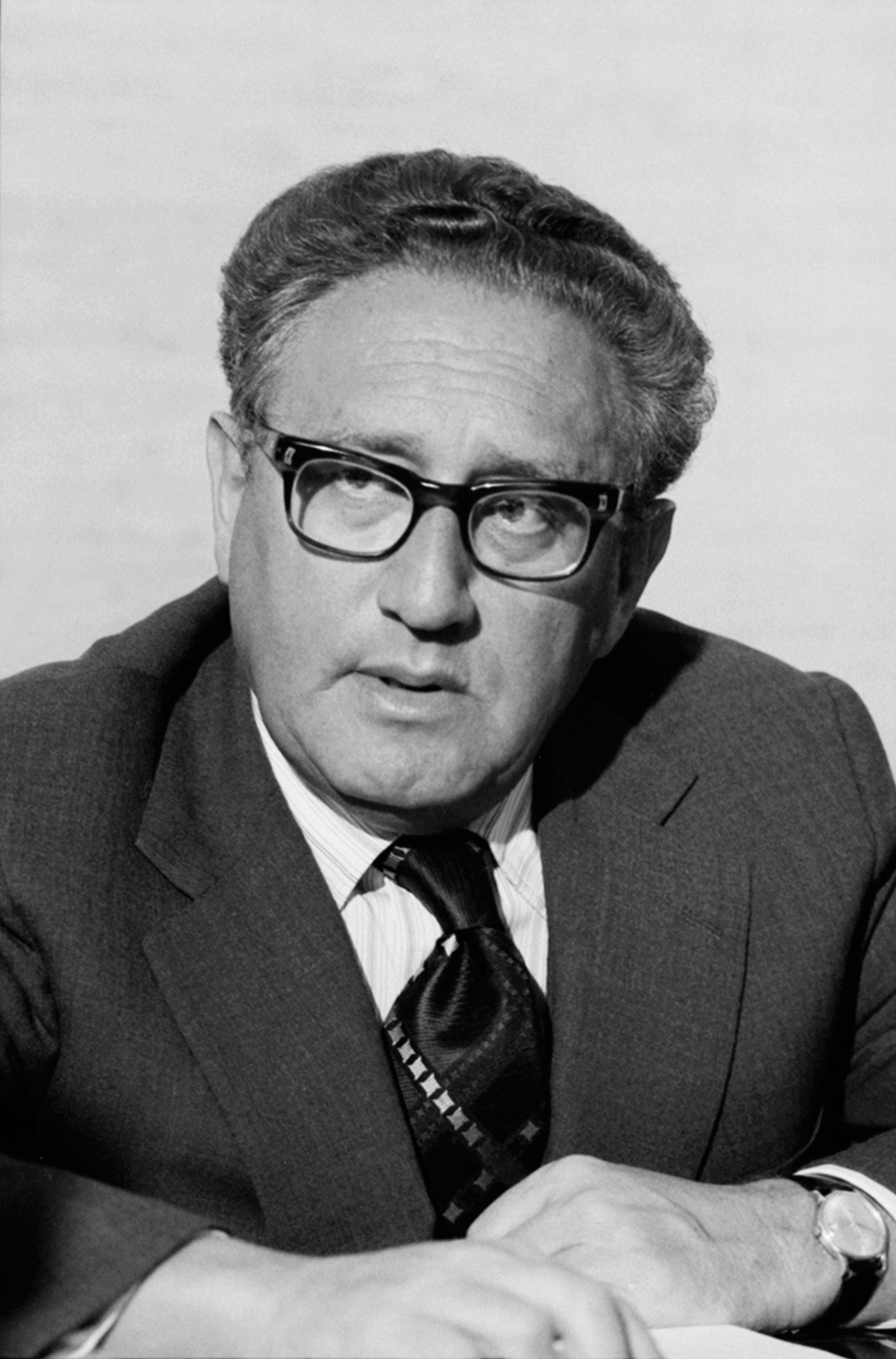

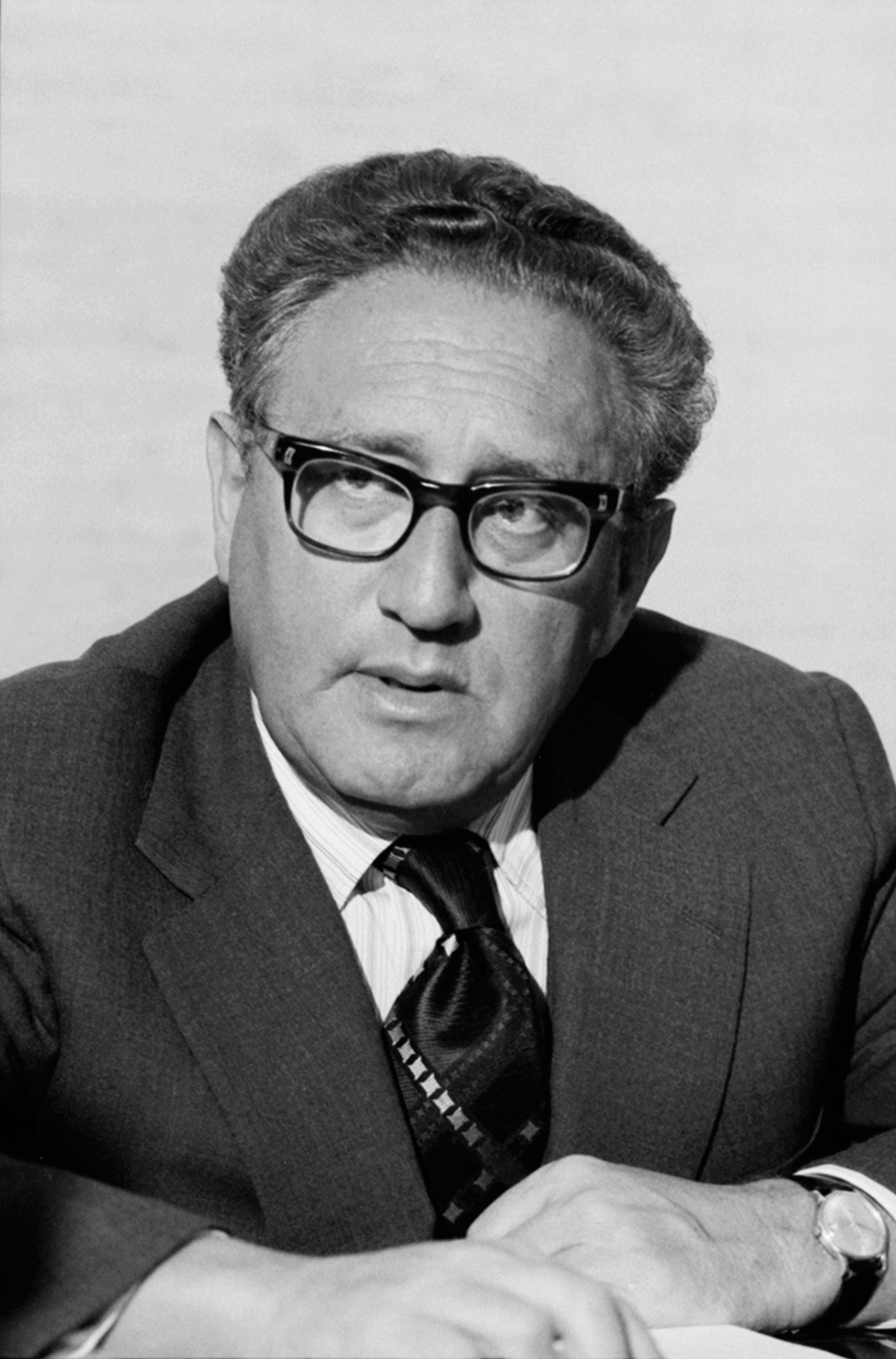

Henry Kissinger

Henry Kissinger

Henry Alfred Kissinger (; ; born Heinz Alfred Kissinger, May 27, 1923) is a German-born American politician, diplomat, and geopolitical consultant who served as United States Secretary of State and National Security Advisor under the presid ...

implemented two geostrategic objectives when in office: the deliberate move to shift the polarity of the international system from bipolar to tripolar; and, the designation of regional stabilizing states in connection with the Nixon Doctrine. In Chapter 28 of his long work, ''Diplomacy

Diplomacy comprises spoken or written communication by representatives of states (such as leaders and diplomats) intended to influence events in the international system.Ronald Peter Barston, ''Modern diplomacy'', Pearson Education, 2006, p. ...

'', Kissinger discusses the " opening of China" as a deliberate strategy to change the balance of power in the international system, taking advantage of the split within the Sino-Soviet bloc. The regional stabilizers were pro-American states which would receive significant U.S. aid in exchange for assuming responsibility for regional stability. Among the regional stabilizers designated by Kissinger were Zaire, Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

, and Indonesia

Indonesia, officially the Republic of Indonesia, is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania between the Indian and Pacific oceans. It consists of over 17,000 islands, including Sumatra, Java, Sulawesi, and parts of Borneo and New Gui ...

.Stephen Kinzer.Turkey, a longtime U.S. ally, now pursues its own path. Guess why.

''

American Prospect

''The American Prospect'' is a daily online and bimonthly print American political and public policy magazine dedicated to American modern liberalism and progressivism. Based in Washington, D.C., ''The American Prospect'' says it "is devoted to ...

'', 5 February 2006

Zbigniew Brzezinski

Zbigniew Brzezinski laid out his most significant contribution to post-Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because t ...

geostrategy in his 1997 book ''The Grand Chessboard

''The Grand Chessboard: American Primacy and Its Geostrategic Imperatives'' (1997) is one of the major works of Zbigniew Brzezinski. Brzezinski graduated with a PhD from Harvard University in 1953 and became Professor of American Foreign Policy ...

''. He defined four regions of Eurasia

Eurasia (, ) is the largest continental area on Earth, comprising all of Europe and Asia. Primarily in the Northern and Eastern Hemispheres, it spans from the British Isles and the Iberian Peninsula in the west to the Japanese archipelag ...

, and in which ways the United States ought to design its policy toward each region in order to maintain its global primacy. The four regions (echoing Mackinder and Spykman) are:

* Europe, the Democratic Bridgehead

* Russia, the Black Hole

* The Middle East, the Eurasian Balkans

* Asia, the Far Eastern Anchor

In his subsequent book, ''The Choice'', Brzezinski updates his geostrategy in light of globalization

Globalization, or globalisation (Commonwealth English; see spelling differences), is the process of interaction and integration among people, companies, and governments worldwide. The term ''globalization'' first appeared in the early 20t ...

, 9/11 and the intervening six years between the two books.

In his journal called ''America's New Geostrategy'', he discusses the need of shift in America's geostrategy to avoid its massive collapse like many scholars predict. He points out that:

* the United States needs to shift away from its long-standing preoccupation with the threat of a nuclear war between the superpower

A superpower is a state with a dominant position characterized by its extensive ability to exert influence or project power on a global scale. This is done through the combined means of economic, military, technological, political and cultural ...

s or a massive Soviet conventional attack in central Europe.

* a doctrine and a force posture are needed that will enable the United States to respond more selectively to a large number of possible security threats to enhance deterrence in the current and foreseeable conditions.

* the United States should rely to a greater extent on a more flexible mix of nuclear and even non-nuclear strategic forces capable of executing more selective military mission

Other notable geostrategists

See also

* German geostrategy * Indian geostrategy * Pakistani geostrategy * Geostrategy in Taiwan *Geostrategy in Central Asia

Central Asia has long been a geostrategic location because of its proximity to the interests of several great powers and regional powers.

Strategic geography

Central Asia has had both the advantage and disadvantage of a central location between ...

* Oil geostrategy

* Geoeconomics

References

Further reading

* Brzezinski, Zbigniew. ''The Grand Chessboard: American Primacy and its Geostrategic Imperatives.'' New York: Basic Books, 1997. * Brzezinski, Zbigniew. ''America's New Geostrategy.'' Council on Foreign Relations, 1988 * Gray, Colin S. and Geoffrey Sloan. ''Geopolitics, Geography and Strategy.'' Portland, OR: Frank Cass, 1999. * Mackinder, Halford J''Democratic Ideals and Reality.''

Washington, DC: National Defense University Press, 1996. * Mahan, Alfred Thayer. ''The Problem of Asia: Its Effects Upon International Politics.'' New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 2003. * Daclon, Corrado Maria. ''Geopolitics of Environment, A Wider Approach to the Global Challenges.'' Italy: Comunità Internazionale, SIOI, 2007. * Efremenko, Dmitry V

''Russian Geostrategic Imperatives. Collection of Essays.''

Moscow: Russian Academy of Sciences, Institute of Scientific Information for Social Sciences, 2019.

European Geostrategy

Ukrainian Geostrategy

* The GeGaLo index of geopolitical gains and losses assesses how the geopolitical position of 156 countries may change if the world fully transitions to renewable energy resources. Former fossil fuels exporters are expected to lose power, while the positions of former fossil fuel importers and countries rich in renewable energy resources is expected to strengthen.{{Cite journal, last1=Overland, first1=Indra, last2=Bazilian, first2=Morgan, last3=Ilimbek Uulu, first3=Talgat, last4=Vakulchuk, first4=Roman, last5=Westphal, first5=Kirsten, date=2019, title=The GeGaLo index: Geopolitical gains and losses after energy transition, journal=Energy Strategy Reviews, language=en, volume=26, pages=100406, doi=10.1016/j.esr.2019.100406, doi-access=free Geopolitics Strategy