George Lloyd, 1st Baron Lloyd on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

George Ambrose Lloyd, 1st Baron Lloyd, (19 September 1879 – 4 February 1941) was a British

George Ambrose Lloyd, 1st Baron Lloyd, (19 September 1879 – 4 February 1941) was a British

In 1901 Lloyd joined the family firm

In 1901 Lloyd joined the family firm

The Papers of Lord Lloyd of Dolobran

held at

Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

politician strongly associated with the " Diehard" wing of the party. From 1937 to 1941 he was chairman of the British Council

The British Council is a British organisation specialising in international cultural and educational opportunities. It works in over 100 countries: promoting a wider knowledge of the United Kingdom and the English language (and the Welsh lan ...

, in which capacity he sought to ensure support for Britain's position in the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

.

Background

Lloyd was born at Olton Hall, Warwickshire, the son of Sampson Samuel Lloyd (whose namesake father was also aMember of Parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members o ...

) and Jane Emilia, daughter of Thomas Lloyd. He was educated at Eton and Trinity College, Cambridge

Trinity College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. Founded in 1546 by King Henry VIII, Trinity is one of the largest Cambridge colleges, with the largest financial endowment of any college at either Cambridge or Oxford. ...

. He coxed the Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cambridge bec ...

crew in the 1899 and 1900 Boat Races

A boat is a watercraft of a large range of types and sizes, but generally smaller than a ship, which is distinguished by its larger size, shape, cargo or passenger capacity, or its ability to carry boats.

Small boats are typically found on inl ...

. He left without taking a degree, unsettled by the deaths of both his parents in 1899, and made a tour of India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area, the List of countries and dependencies by population, second-most populous ...

.Article by Jason Tombs.

In 1901 Lloyd joined the family firm

In 1901 Lloyd joined the family firm Stewarts & Lloyds

Stewarts & Lloyds was a steel tube manufacturer with its headquarters in Glasgow at 41 Oswald Street. The company was created in 1903 by the amalgamation of two of the largest iron and steel makers in Britain, A. & J. Stewart & Menzies, Coatbridg ...

as its youngest director. In 1903 he first became involved with the tariff reform

The Tariff Reform League (TRL) was a protectionist British pressure group formed in 1903 to protest against what they considered to be unfair foreign imports and to advocate Imperial Preference to protect British industry from foreign competitio ...

movement of Joseph Chamberlain

Joseph Chamberlain (8 July 1836 – 2 July 1914) was a British statesman who was first a radical Liberal, then a Liberal Unionist after opposing home rule for Ireland, and eventually served as a leading imperialist in coalition with the C ...

. In 1904 he fell in love with Lady Constance Knox, daughter of the 5th Earl of Ranfurly, who forbade the match with his daughter considering him unsuitable (she then married Evelyn Milnes Gaskell, son of Rt. Hon. Charles Gaskell, in November 1905). In 1905 he turned down an offer by Stewarts & Lloyds of a steady position in London and chose to embark on a study of the East in the British Empire.

Foreign office

Through the efforts of his friends Samuel Pepys Cockerell, working in the commercial department of the Foreign Office, andGertrude Bell

Gertrude Margaret Lowthian Bell, CBE (14 July 1868 – 12 July 1926) was an English writer, traveller, political officer, administrator, and archaeologist. She spent much of her life exploring and mapping the Middle East, and became highl ...

, whom he had come to know, he started work as an unpaid honorary attaché in Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

. At "Old Stamboul" – as he came to remember the Embassy of Sir Nicholas O'Conor – he worked together with Laurence Oliphant, Percy Loraine

Sir Percy Lyham Loraine, 12th Baronet, (5 November 1880 – 23 May 1961) was a British diplomat. He was British High Commissioner to Egypt from 1929 to 1933, British Ambassador to Turkey from 1933 to 1939 and British Ambassador to Italy from ...

and Alexander Cadogan

Sir Alexander Montagu George Cadogan (25 November 1884 – 9 July 1968) was a British diplomat and civil servant. He was Permanent Under-Secretary for Foreign Affairs from 1938 to 1946. His long tenure of the Permanent Secretary's office makes ...

. There also he first met Mark Sykes

Colonel Sir Tatton Benvenuto Mark Sykes, 6th Baronet (16 March 1879 – 16 February 1919) was an English traveller, Conservative Party politician, and diplomatic advisor, particularly with regard to the Middle East at the time of the First Wo ...

and Aubrey Herbert

Colonel The Honourable Aubrey Nigel Henry Molyneux Herbert (3 April 1880 – 26 September 1923), of Pixton Park in Somerset and of Teversal, in Nottinghamshire, was a British soldier, diplomat, traveller, and intelligence officer associat ...

. In April 1906 Aubrey Herbert joined him on an exploration of the state of the Baghdad Railway

Baghdad (; ar, بَغْدَاد , ) is the capital of Iraq and the second-largest city in the Arab world after Cairo. It is located on the Tigris near the ruins of the ancient city of Babylon and the Sassanid Persian capital of Ctesiphon ...

. His confidential memorandum of November 1906 on the Hejaz railway gave a detailed account of many economic problems. This, and other papers – on Turkish finance, for example – led to his appointment in January 1907 as a special commissioner to investigate trading prospects around the Persian Gulf

The Persian Gulf ( fa, خلیج فارس, translit=xalij-e fârs, lit=Gulf of Fars, ), sometimes called the ( ar, اَلْخَلِيْجُ ٱلْعَرَبِيُّ, Al-Khalīj al-ˁArabī), is a mediterranean sea in Western Asia. The bo ...

.

Parliamentary candidate

Lloyd had been strongly influenced by Joseph Chamberlain's call fortariff reform

The Tariff Reform League (TRL) was a protectionist British pressure group formed in 1903 to protest against what they considered to be unfair foreign imports and to advocate Imperial Preference to protect British industry from foreign competitio ...

to link Britain and the Dominion

The term ''Dominion'' is used to refer to one of several self-governing nations of the British Empire.

"Dominion status" was first accorded to Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Newfoundland, South Africa, and the Irish Free State at the 1926 ...

s closer together, and the tariff issue now inspired Lloyd to enter politics.Atherton, 1994 page 26. At the January 1910 general election

The January 1910 United Kingdom general election was held from 15 January to 10 February 1910. The government called the election in the midst of a constitutional crisis caused by the rejection of the People's Budget by the Conservative-dominat ...

Lloyd was elected as a Liberal Unionist

The Liberal Unionist Party was a British political party that was formed in 1886 by a faction that broke away from the Liberal Party. Led by Lord Hartington (later the Duke of Devonshire) and Joseph Chamberlain, the party established a politic ...

Member of Parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members o ...

(MP) for West Staffordshire, marrying Blanche Lascelles the following year. In February 1914, Lloyd was adopted as Unionist Parliamentary candidate for Shrewsbury

Shrewsbury ( , also ) is a market town, civil parish, and the county town of Shropshire, England, on the River Severn, north-west of London; at the 2021 census, it had a population of 76,782. The town's name can be pronounced as either 'Sh ...

ahead of the next general election (expected no later than the end of 1915) when the sitting MP, unrelated namesake George Butler Lloyd

George Butler Lloyd (8 January 1854 – 28 March 1930) was a British banker and Conservative Party politician.

He was the eldest son of William Butler Lloyd (1825-1874), a banker, of Monkmoor Hall, Shrewsbury, and Preston Montford, Shropshire, a ...

, intended to retire. Lloyd was completely opposed to women's suffrage, writing that to give women the right to vote would ensure that they would vote "for the ''beaux yeux'' of the candidates".

The general election and his candidacy were both forestalled by the outbreak of the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

, while the sitting member continued to hold his seat until 1922. He and another backbench colleague in Parliament, Leopold Amery, lobbied the Conservative leadership to press for an immediate declaration of war against Germany on 1 August 1914.

In conjunction with Edward Wood (later Earl of Halifax

Earl of Halifax is a title that has been created four times in British history—once in the Peerage of England, twice in the Peerage of Great Britain, and once in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. The name of the peerage refers to Halifax, We ...

) he wrote ''The Great Opportunity'' in 1918. This book was meant to be a Conservative challenge to the Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor, (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. He was a Liberal Party politician from Wales, known for leading the United Kingdom during ...

coalition and stressed devolution of power from Westminster and the importance of reviving English industry and agriculture.

First World War

As aLieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations.

The meaning of lieutenant differs in different militaries (see comparative military ranks), but it is often ...

in the Warwickshire Yeomanry

The Warwickshire Yeomanry was a yeomanry regiment of the British Army, first raised in 1794, which served as cavalry and machine gunners in the First World War and as a cavalry and an armoured regiment in the Second World War, before being amalg ...

, Lloyd was called up after Britain entered the war three days later.

During that war he served on the staff of Sir Ian Hamilton

Sir Ian Standish Monteith Hamilton, (16 January 1853 – 12 October 1947) was a British Army general who had an extensive British Imperial military career in the Victorian and Edwardian eras. Hamilton was twice recommended for the Victoria Cro ...

at Gallipoli

The Gallipoli peninsula (; tr, Gelibolu Yarımadası; grc, Χερσόνησος της Καλλίπολης, ) is located in the southern part of East Thrace, the European part of Turkey, with the Aegean Sea to the west and the Dardanelles s ...

landing with the ANZACs on the first day of that campaign; took part in a special British mission to Petrograd

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

to improve Anglo-Russian liaison; visited Basra

Basra ( ar, ٱلْبَصْرَة, al-Baṣrah) is an Iraqi city located on the Shatt al-Arab. It had an estimated population of 1.4 million in 2018. Basra is also Iraq's main port, although it does not have deep water access, which is han ...

to update his study of commerce in the Persian Gulf; and, after a time in Cairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the largest urban agglomeration in Africa, the Arab world and the Middle East: The Greater Cairo metr ...

, with T. E. Lawrence and the Arab Bureau in Hejaz

The Hejaz (, also ; ar, ٱلْحِجَاز, al-Ḥijāz, lit=the Barrier, ) is a region in the west of Saudi Arabia. It includes the cities of Mecca, Medina, Jeddah, Tabuk, Yanbu, Taif, and Baljurashi. It is also known as the "Western Prov ...

, the Negev

The Negev or Negeb (; he, הַנֶּגֶב, hanNegév; ar, ٱلنَّقَب, an-Naqab) is a desert and semidesert region of southern Israel. The region's largest city and administrative capital is Beersheba (pop. ), in the north. At its sout ...

and the Sinai desert. He reached the rank of Captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

in the Warwickshire Yeomanry (in which regiment he continued to hold rank until 1925) and was awarded the Distinguished Service Order

The Distinguished Service Order (DSO) is a military decoration of the United Kingdom, as well as formerly of other parts of the Commonwealth, awarded for meritorious or distinguished service by officers of the armed forces during wartime, ty ...

and made Companion of the Indian Empire

The Most Eminent Order of the Indian Empire is an order of chivalry founded by Queen Victoria on 1 January 1878. The Order includes members of three classes:

#Knight Grand Commander (GCIE)

#Knight Commander ( KCIE)

#Companion ( CIE)

No appoi ...

in 1917. For services in the same war he also received the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War ...

's Order of St Anne, 3rd Class and the Order of Al Nahda (2nd class) of the Kingdom of Hejaz

The Hashemite Kingdom of Hejaz ( ar, المملكة الحجازية الهاشمية, ''Al-Mamlakah al-Ḥijāziyyah Al-Hāshimiyyah'') was a state in the Hejaz region in the Middle East that included the western portion of the Arabian Penins ...

.

Colonial posts

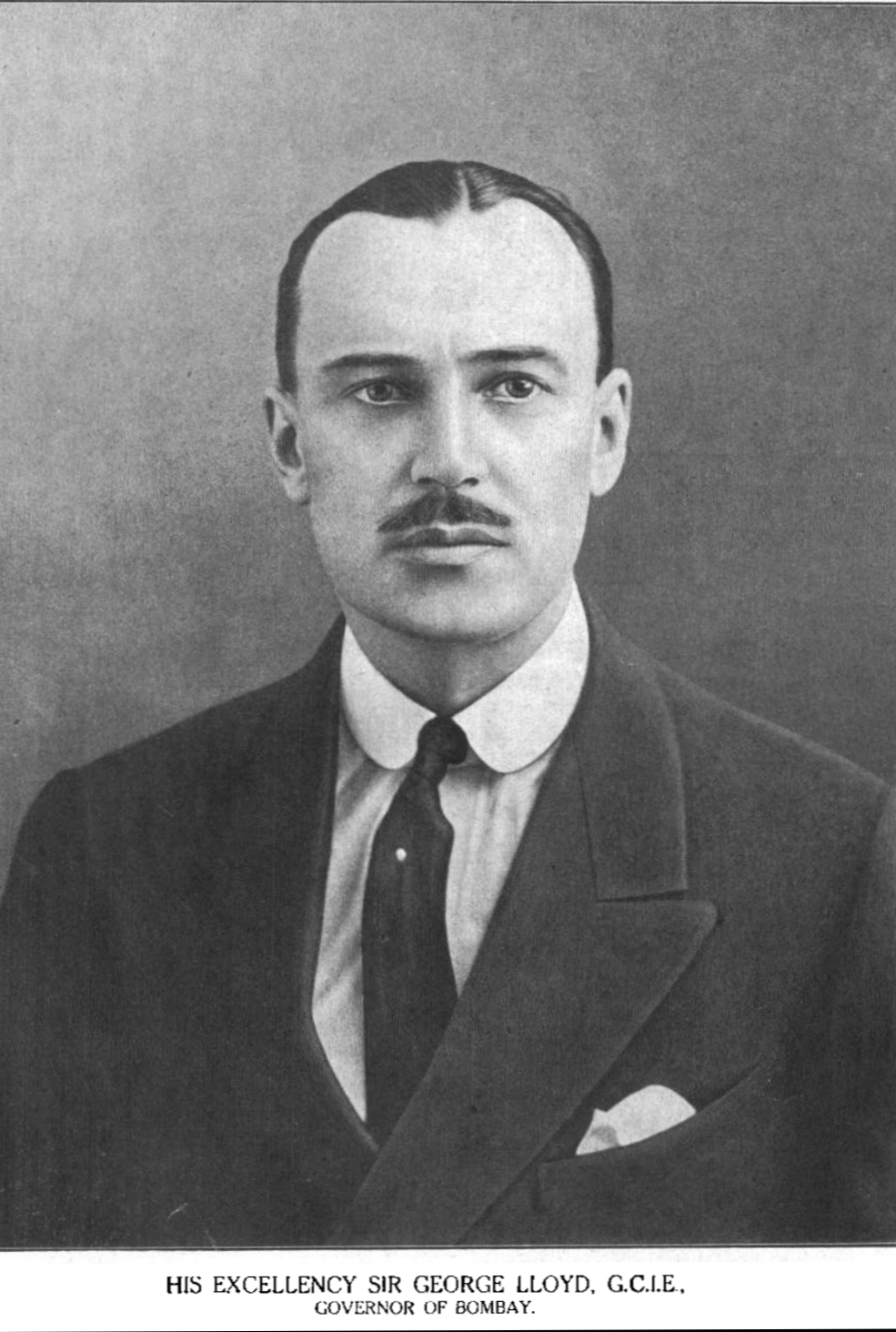

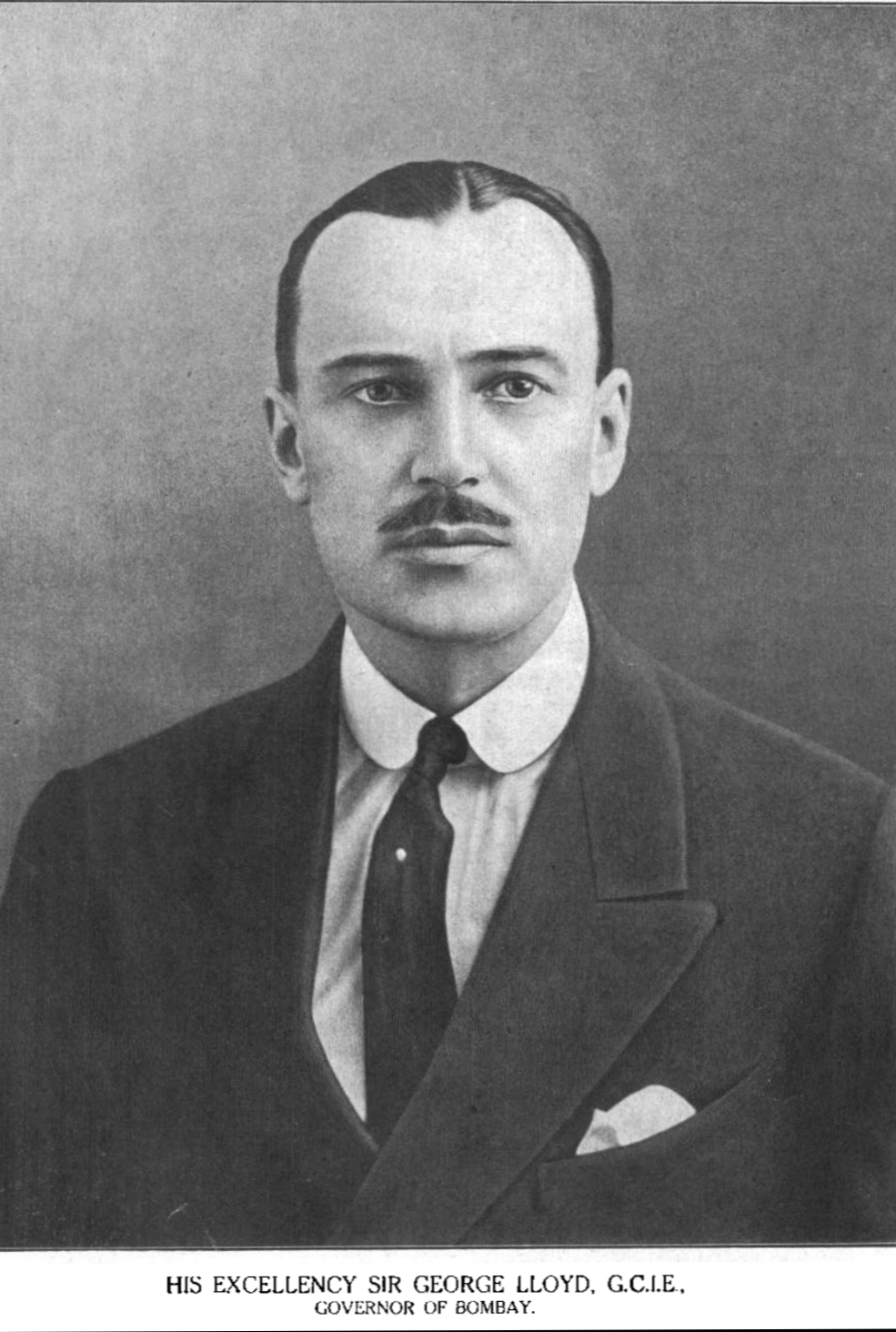

Bombay

In December 1918 he was appointedGovernor of Bombay

Until the 18th century, Bombay consisted of seven islands separated by shallow sea. These seven islands were part of a larger archipelago in the Arabian sea, off the western coast of India. The date of city's founding is unclear—historians tr ...

and made KCIE. His principal activities while governor were reclaiming land for housing in the Back Bay area of the city of Bombay

Mumbai (, ; also known as Bombay — List of renamed Indian cities and states#Maharashtra, the official name until 1995) is the capital city of the Indian States and union territories of India, state of Maharashtra and the ''de facto'' fin ...

and building the Lloyd Barrage (now Sukkur Barrage) an irrigation scheme, both of which were funded by loans raised in India instead of in England. Lloyd's administration was the first to raise such funds locally. His province was one of the centres of Indian nationalist unrest, to deal with which he insisted in 1921 on the arrest of Mahatma Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (; ; 2 October 1869 – 30 January 1948), popularly known as Mahatma Gandhi, was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalist Quote: "... marks Gandhi as a hybrid cosmopolitan figure who transformed ... anti- ...

, who was subsequently galled for six years for sedition

Sedition is overt conduct, such as speech and organization, that tends toward rebellion against the established order. Sedition often includes subversion of a constitution and incitement of discontent toward, or insurrection against, esta ...

. Lloyd was very strongly opposed to Indian independence or even bringing a measure of democracy to the Raj, writing of what he called "the fundamental unsuitability of modern western democratic methods of government to any Oriental people". A strong believer in what he regarded as the greatness of the British empire, Lloyd wrote from Bombay to a friend on 25 August 1920: "The real truth is that we can't withdraw the legions: every schoolboy knows what happened to Rome as the legions began to do so." The British historian Louise Atherton wrote that Lloyd was: "Idealistically, almost mystically, devoted to the British Empire, he advocated the use of force, if necessary, to maintain British control". He completed his term as governor in 1923 and was made a Privy Counsellor

The Privy Council (PC), officially His Majesty's Most Honourable Privy Council, is a formal body of advisers to the sovereign of the United Kingdom. Its membership mainly comprises senior politicians who are current or former members of ei ...

and GCSI

The Most Exalted Order of the Star of India is an order of chivalry founded by Queen Victoria in 1861. The Order includes members of three classes:

# Knight Grand Commander (:Knights Grand Commander of the Order of the Star of India, GCSI)

# ...

.

He was instrumental in selecting and sending the first ever truly Indian team of athletes to Olympics in 1920 to the 7th Olympic Games held at Antwerp, Belgium. He helped form the ad-hoc Indian Olympic Association under the chairmanship of industrialist and philanthropist Sir Dorabji Tata. Si Lloyd made special arrangements for preparations and training of the six member team in England, arranged for their travel, stay in military facilities both in London and then in Antwerp. He negotiated the arrangements with Sir Winston Churchill and got the required permissions even when the British empire was broke due to the first world war and struggling even to send their own teams to the Games. Ref.: India at the 1920 Summer Olympics

India sent its first Olympic team to the 1920 Summer Olympics in Antwerp, Belgium, some twenty years after a single athlete (Norman Pritchard) competed for India in 1900 (see India at the 1900 Summer Olympics).

Background, team selection, and lo ...

. A patron of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute

The Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute (BORI) is located in Pune, Maharashtra, India. It was founded on 6 July 1917 and named after Ramakrishna Gopal Bhandarkar (1837–1925), long regarded as the founder of Indology (Orientalism) in Ind ...

, he also established an annual grant dedicated to their efforts in producing a critical edition of the Hindu epic, ''Mahabharata

The ''Mahābhārata'' ( ; sa, महाभारतम्, ', ) is one of the two major Sanskrit epics of ancient India in Hinduism, the other being the '' Rāmāyaṇa''. It narrates the struggle between two groups of cousins in the K ...

.''

Egypt

He returned to Parliament again forEastbourne

Eastbourne () is a town and seaside resort in East Sussex, on the south coast of England, east of Brighton and south of London. Eastbourne is immediately east of Beachy Head, the highest chalk sea cliff in Great Britain and part of the l ...

in 1924, serving until 1925, when he was made Baron Lloyd, of Dolobran in the County of Montgomery, called after his Welsh ancestral home. Following his ennoblement, he was appointed High Commissioner to Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning the North Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via a land bridg ...

, serving until his resignation was forced upon him by Labour Foreign Secretary

The secretary of state for foreign, Commonwealth and development affairs, known as the foreign secretary, is a Secretary of State (United Kingdom), minister of the Crown of the Government of the United Kingdom and head of the Foreign, Commonwe ...

Arthur Henderson

Arthur Henderson (13 September 1863 – 20 October 1935) was a British iron moulder and Labour politician. He was the first Labour cabinet minister, won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1934 and, uniquely, served three separate terms as Leader of t ...

in 1929. His views and experience formed the background of a self-justifying two-volume book, ''Egypt Since Cromer

Cromer ( ) is a coastal town and civil parish on the north coast of the English county of Norfolk. It is north of Norwich, north-northeast of London and east of Sheringham on the North Sea coastline.

The local government authorities are Nor ...

'' (published 1933–34).

Lobbying

In 1930, Lloyd became president of the Navy League which lobbied the government for to spend more money on the Royal Navy and was a member of theIndia Defence League The India Defence League was a British pressure group founded in June 1933 dedicated to keeping India within the British Empire.

It grew from the parliamentary India Defence Committee and was founded with the support of 10 Privy Councillors, 28 p ...

, which lobbied the government not to grant home rule to India. During the 1930s he was one of the most prominent opponents of proposals to grant Indian Home Rule, working alongside Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

against the National Government. From 1931 to 1935 Lord Lloyd employed James Lees-Milne

(George) James Henry Lees-Milne (6 August 1908 – 28 December 1997) was an English writer and expert on country houses, who worked for the National Trust from 1936 to 1973. He was an architectural historian, novelist and biographer. His extensi ...

as one of his male secretaries. He was suspicious of Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 and the ...

and the Nazi

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in ...

movement, which he saw as a threat to Britain. He was agitating for rearmament against Germany as early as 1930, before Churchill did.

British Council

From July 1937 onward he was chairman of the British Council, in which he oversaw an increase in lectureships and made cultural tours of neutral capitals to maintain sympathy for Britain's cause during the early months of the Second World War. The council was a purportedly independent group meant to engage in cultural propaganda promoting the British way of life to the rest of the world that was in fact under the control of the Foreign Office. As head of the British Council, Lloyd ran his own private intelligence network , employing as one his spies, the journalist Ian Colvin, who served as the Berlin correspondent of ''The News Chronicle''.Watt, D.C. ''How War Came'', New York: Pantheon, 1989 p.182. Unusually, Lloyd enjoyed a privileged access to the secret reports of MI6, the British intelligence service. The British historian D.C. Watt called Lloyd "one of those uncontrollable ''lusi naturae'' the British elite throws up from time to time".Watt, D.C. ''How War Came'', New York: Pantheon, 1989 p.90. In November 1937, the Foreign Secretary,Anthony Eden

Robert Anthony Eden, 1st Earl of Avon, (12 June 1897 – 14 January 1977) was a British Conservative Party politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1955 until his resignation in 1957.

Achieving rapid promo ...

, instructed Lloyd that the British Council was to concentrate especially on improving Britain's image in Portugal, Greece, Turkey, Yugoslavia, Romania, and Poland. Regarding the Middle East, especially Egypt, as a crucial area of control for Britain, Lloyd regarded the approaches to the Near East as equally crucial, which led him to become obsessed with the Balkans, which called the "eastern approaches", independently of Eden's instructions.Atherton, 1994 page 28. In April 1938, he suggested in a memo sent to the Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain and the Foreign Secretary Lord Halifax that Britain needed to become more economically involved in the Balkans, which were rapidly falling into the German economic sphere of influence. After discussing the issue with King George II of Greece

George II ( el, Γεώργιος Βʹ, ''Geórgios II''; 19 July Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O.S.:_7_July.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>O.S.:_7_July">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html"_;"title="nowiki/ ...

during a visit to Athens in May 1938, Lloyd submitted another memo calling for Britain to increase the import of staple goods from Bulgaria, Turkey, Greece and Romania. In response, Britain granted Turkey a credit of £16 million pounds sterling that month, through Lloyd's idea of an "economic offensive" in the Balkans was not taken up at the time.Atherton, 1994 page 29.

Czechoslovakia

Lloyd was not in sympathy with the Chamberlain government's policies towards Czechoslovakia in August–September 1938, and his advice that he gave his old friend, Lord Halifax, who was serving as Foreign Secretary after Eden had resigned in February 1938 in protest against the Chamberlain's government's policies towards Fascist Italy, was not followed. Lloyd passed on to the government on 3 August 1938 a report from Colvin which stated that Germany planned to invade Czechoslovakia on 28 September 1938. In September 1938, the Prime MinisterNeville Chamberlain

Arthur Neville Chamberlain (; 18 March 18699 November 1940) was a British politician of the Conservative Party who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from May 1937 to May 1940. He is best known for his foreign policy of appeaseme ...

flew to Germany three times for summits with Hitler at Berchtesgaden, Bad Godesberg and Munich to discuss the Sudetenland

The Sudetenland ( , ; Czech and sk, Sudety) is the historical German name for the northern, southern, and western areas of former Czechoslovakia which were inhabited primarily by Sudeten Germans. These German speakers had predominated in the ...

crisis. In a letter of 20 October 1938 to Sir Percy Loraine

Sir Percy Lyham Loraine, 12th Baronet, (5 November 1880 – 23 May 1961) was a British diplomat. He was British High Commissioner to Egypt from 1929 to 1933, British Ambassador to Turkey from 1933 to 1939 and British Ambassador to Italy from ...

, Lloyd sardonically wrote of these three summits: "If at first you don't concede, fly, fly again."

America

In the tense atmosphere of 1938, Lloyd tried hard to increase British propaganda in the United States to an attempt to involve the United States in the Sudetenland dispute, favoring an approach of trying to appeal to the American elite rather than the American people in general. In June 1938, he argued that the British Council should arrange for British professors to serve as visiting lecturers at American universities to strengthen Anglo-American relations.Cull, Nicholas "The Munich Crisis and British Propaganda Policy in the United States" pages 216–235 from ''The Munich Crisis, Prelude to World War II'' edited by Igor Lukes and Erik Goldstein, London: Frank Cass, 1999 page 218. The same month, the U.S Congress passed theForeign Agents Registration Act

The Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA)2 U.S.C. § 611 ''et seq.'' is a United States law that imposes public disclosure obligations on persons representing foreign interests.

, which required all propaganda by foreign governments in the United States to be registered with the State Department and labelled as propaganda. Representative Martin Dies Jr., chairman of the House Committee for the Investigation of Un-American Activities (HUAC), announced his committee would be investigating British attempts to get the United States involved in European conflicts, alleging that the only reason why the United States declared war on Germany in 1917 was because of improper British propaganda, and vowed his country would not be "tricked" again into declaring war on Germany. In response to the xenophobic mood in Congress, the British ambassador in Washington, Sir Ronald Lindsay, objected to Lloyd's plans, writing if the Foreign Office knew "what they were at", saying that any British Council propaganda in America would offend Congress. Even Lloyd's plans to use the British Pavilion at the upcoming World Fair in New York in 1939 to promote the British viewpoint drew objections from Lindsay that it would upset Congress. Lindsay regarded Dies as a particular problem as the congressman from Texas was known for his grandstanding style and his love of publicity, which led him to make fantastic and often bizarre statements. As a result of Lindsay's objections, Britain instituted a "No-Propaganda" policy in the United States that lasted until 1940. Die's investigation into British propaganda in America failed to find any, causing him to turn his attention to Hollywood, where he alleged that too many filmmakers had left-wing and therefore "un-American" views. Dies made headlines where he announced he found evidence that wealthy Hollywood filmmakers (who were all Jewish) were secretly members of the U.S Communist Party and were smuggling in Spanish Republican

The Spanish Republic (), commonly known as the Second Spanish Republic (), was the form of government in Spain from 1931 to 1939. The Republic was proclaimed on 14 April 1931, after the deposition of King Alfonso XIII, and was dissolved on 1 A ...

soldiers disguised as illegal immigrants from Mexico with the aim of staging a Communist coup, though the subsequent lack of evidence to back up these assertions discredited him.

Lloyd was forced to use a more informal approach to the United States, arranging for Americans with the power to influence American public opinion to visit Britain where they were met by notable British personalities who were instructed to impress them the importance of closer Anglo-American ties as a factor for world peace. The Britons recruited for this work were Sir George Schuster, the president of Lipton's Tea

Lipton is a British brand of tea, owned by Ekaterra. Lipton was also a supermarket chain in the United Kingdom, later sold to Argyll Foods, after which the company sold only tea. The company is named after its founder, Sir Thomas Lipton, who fo ...

; the American-born Conservative MP Ronald Tree

Arthur Ronald Lambert Field Tree (26 September 1897 – 14 July 1976) was a British Conservative Party politician, journalist and investor who served as the Member of Parliament (MP) for the Harborough constituency in Leicestershire from 1933 t ...

; the Scottish aristocrat Lord Lothian, the secretary of the Rhodes Trust

Rhodes House is a building part of the University of Oxford in England. It is located on South Parks Road in central Oxford, and was built in memory of Cecil Rhodes, an alumnus of the university and a major benefactor. It is listed Grade II* ...

; the Labour MP Josiah Wedgewood

Josiah Wedgwood (12 July 1730 – 3 January 1795) was an English potter, entrepreneur and abolitionist. Founding the Wedgwood company in 1759, he developed improved pottery bodies by systematic experimentation, and was the leader in the indu ...

; Angus Fletcher, the president of the British Library of Information; and Frank Darvall, the president of the English Speaking Union

The English-Speaking Union (ESU) is an international educational membership organistation. Founded by the journalist Sir Evelyn Wrench in 1918, it aims to bring together and empower people of different languages and cultures, by building skill ...

who had received his degree at Columbia University. In particular, American journalists were cultivated with the principle theme being that Britain and the United States were both champions of freedom and democracy and should work together more closely for that reason. As these meetings took place in Britain with individuals who were ostensibly expressing their own personal views, and the American correspondents in their writings and broadcasts merely recorded their own experiences of Britain, this completely by-passed the Foreign Agents Registration Act.

The Balkans

Accepting that Czechoslovakia was a lost cause after theMunich Agreement

The Munich Agreement ( cs, Mnichovská dohoda; sk, Mníchovská dohoda; german: Münchner Abkommen) was an agreement concluded at Munich on 30 September 1938, by Germany, the United Kingdom, France, and Italy. It provided "cession to Germany ...

, in the autumn of 1938, Lloyd focused on convincing the government that greater British involvement was needed with the remaining two members of the Little Entente, Yugoslavia and Romania.Atherton, 1994 page 30. Lloyd was especially involved with the latter, where his two principal collaborators were Grigore Gafencu

Grigore Gafencu (; January 30, 1892 – January 30, 1957) was a Romanian politician, diplomat and journalist.

Political career

Gafencu was born in Bârlad. He studied law and received his Ph.D. in law from the University of Bucharest. During ...

and Virgil Tilea, both of whom he knew from his work with the British Council. In October 1938, Lloyd visited Bucharest to meet King Carol II

Carol II (4 April 1953) was King of Romania from 8 June 1930 until his forced abdication on 6 September 1940. The eldest son of Ferdinand I, he became crown prince upon the death of his grand-uncle, King Carol I in 1914. He was the first of th ...

, supposedly to encourage Anglo-Romanian cultural links, but in fact, to hear a plan from the king for Britain to stop Romania from becoming an economic colony of Germany.Atherton, 1994 page 31. Lloyd who rather liked Carol, sent a series of vigorously written telegrams from Bucharest urging that Britain commit itself to spending £500,000 on buying Romanian oil, purchase 600,000 tons of Romanian wheat, and assist Romania with building a naval base where the Danube river flowed into the Black Sea. In the cabinet meetings, Lord Halifax used Lloyd's telegrams to argue that Britain should buy Romanian wheat, saying "how urgent the matter is, and of what importance it is without delay to try and do something in the economic sphere for Romania".Atherton, 1994 page 32. Chamberlain agreed with the idea, through he committed to buying only 200, 000 tons of Romanian wheat following objections from the Treasury.

Lloyd was the most consistent advocate of greater British support for Romania, arguing to Lord Halifax that it was too dangerous to let that oil-rich kingdom fall into the German sphere of influence.Atherton, 1994 page 33. Lloyd noted that Germany had no oil of its own and there were only two places in Europe where oil could be obtained in massive quantities, namely the Soviet Union and Romania, and since the latter was by far the weaker of the two, he believed that Romania would be Hitler's next target.Atherton, 1994 page 36. In response, Halifax argued that the Germans saw Romania as being in their sphere of influence, and too great of British involvement in that kingdom would had been seen by Adolf Hitler as an "encirclement". When Carol visited London between 15–18 November 1938, Lloyd was present to argue on his behalf. Despite all of Lloyd's advocacy of Carol's case during his London visit, Britain agreed to buy 200,000 tons of Romanian wheat at above world prices with an option to buy 400,000 tons while refusing the king's request for a £30 million pound loan. The Chamberlain government committed to spending £10 million pounds in support of threatened nations in November 1938 (through the bill authorising the spending was not passed until February 1939), of which the largest sum, £3 million pounds, went to China while in the Balkans £2 million pounds went to Greece and £1 million pounds to Romania.

In a letter of 24 November, he mentioned that he just returned from the Balkans "to see what could be saved in the Balkans from the Nazis", an allusion to the recent tour of Balkans by the German economics minister, Dr Walther Funk

Walther Funk (18 August 1890 – 31 May 1960) was a German economist and Nazi official who served as Reich Minister for Economic Affairs (1938–1945) and president of Reichsbank (1939–1945). During his incumbency, he oversaw the mobi ...

, who pressed for greater economic integration of the region with the ''Reich''. Acting in his own capacity, Lloyd urged that the directors of the firm Spencer Limited to build grain silos in Romania as Carol had mentioned during his visit to London that Romania's ability to export wheat was hindered by the lack of grain silos. In January 1939, Lloyd advised Gafencu, who just been appointed Romanian foreign minister, to appoint someone of "considerable energy and position" to be the Romanian minister in London, which led to Tilea receiving the appointment.Atherton, 1994 page 34. After King Carol, the Balkan leader whom Lloyd was closest to was Prince Paul, the Regent of Yugoslavia for the boy king Peter II.

Working with a fellow member of the board of the Navy League, Lord Sempill

Lord Sempill (also variously rendered as Semple or Semphill) is a title in the Peerage of Scotland. It was created in circa 1489 for Sir John Sempill, founder of the collegiate Church of Lochwinnoch. Sempill was killed at the Battle of Flodde ...

, who had served as the deputy chairman of the London chamber of commence in 1931–34, Lloyd sought from January 1939 onward to encourage British businesses to buy many products from the Balkans as possible. Lord Semphill had once been an enthusiast for Nazi Germany, having joined the Anglo-German Fellowship

The Anglo-German Fellowship was a membership organisation that existed from 1935 to 1939, and aimed to build up friendship between the United Kingdom and Germany. It was widely perceived as being allied to Nazism. Previous groups in Britain wi ...

, but he was described as being " was impressed by Lloyd's propaganda efforts and wanted to back them with specific business arrangements." In February 1939, he visited Athens to meet the Greek dictator, General Ioannis Metaxas

Ioannis Metaxas (; el, Ιωάννης Μεταξάς; 12th April 187129th January 1941) was a Greek military officer and politician who served as the Prime Minister of Greece from 1936 until his death in 1941. He governed constitutionally for t ...

, in an effort to improve Anglo-Greek relations. In a bid to "soften the dictatorship", Lloyd arranged for greater British Council involvement with the National Youth Organisation, which he believed would allow the British Council to win over Greek public opinion. During his visit to Athens, Lloyd also advised King George II to dismiss the Germanophile Metaxas as prime minister and appoint an Anglophile as his successor, advice that the king refused. Lloyd made clear during his Greek visit his personal preference for Venizelism

Venizelism ( el, Βενιζελισμός) was one of the major political movements in Greece from the 1900s until the mid-1970s.

Main ideas

Named after Eleftherios Venizelos, the key characteristics of Venizelism were:

*Greek irredentism: T ...

, meeting several Venizelist Greek politicians, which was also a way of expressing his distaste for the 4th of August Regime

The 4th of August Regime ( el, Καθεστώς της 4ης Αυγούστου, Kathestós tis tetártis Avgoústou), commonly also known as the Metaxas regime (, ''Kathestós Metaxá''), was a totalitarian regime under the leadership of Gener ...

. Upon his return from Greece, Lloyd pressed very strongly for the government to force British tobacco companies to buy the Greek tobacco crop.Atherton, 1994 page 35. During his visit to Greece, both King George and Mextaxas had told him that Germany had more to offer Greece economically than did Britain, which led Lloyd to decide on a dramatic gesture which would prove otherwise. Lloyd's advocacy of buying the entire Greek tobacco crop for 1939 led to bureaucratic struggle as objections were raised that it was unfair to force British smokers to use Greek tobacco (regarded as inferior) when they were used to American and Canadian tobacco (regarded as superior).

Second world war

On 27 January 1939, Lloyd passed on to the government a report he received from Colvin that Germany was planning to invade Poland in the spring of 1939. In March 1939, Lloyd played a major role in the "Tilea affair" when Tilea claimed that Romania was on the brink of a German invasion, a claim he strongly endorsed despite the denials of Gafencu. Lloyd argued to Halifax based upon his sources in Romania that the Germany had indeed threatened an invasion, which the Romanians were denying out of the fear of enraging Hitler. In late March 1939, Lloyd received information from Colvin that Germany was planning on invading Poland that spring and on 23 March 1939 told Colvin that he would arrange for him to meet Chamberlain and Lord Halifax. Through Colvin did meet Chamberlain and Lord Halifax on 29 March 1939, it is not clear much credence Lloyd placed on his reports as on 31 March-the same day that Chamberlain announced the "guarantee" of Poland in the House of Commons-Lloyd told Halifax that he still regarded Romania rather than Poland as Hitler's probable next target. Lloyd argued that Britain and France should co-ordinate their policies in the Balkans as the best way of deterring Germany and played a major role in ensuring the Anglo-French "guarantees" of Romania and Greece issued on 13 April 1939.Atherton, 1994 page 37. After the Italians annexed Albania on 4 April 1939, there was a general consensus within the Chamberlain cabinet that Britain should "guarantee" Greece, but it was felt that the Romanians should commit to strengthening their alliance with Poland before Britain offered a "guarantee" of Romania. As the Danzig crisis was just beginning, Carol was reluctant to strengthen the Romanian alliance with Poland. When Tilea told Lloyd that Britain was hesitant to "guarantee" Romania while the French were not, Lloyd went to the French embassy. Lloyd was regarded as such an important personality that he was able to barge in as the French ambassadorCharles Corbin

Charles Corbin (1881–1970) was a French diplomat who served as ambassador to Britain before and during the early part of the Second World War, from 1933 to 27 June 1940.

Early life

He was born in Paris, the son of Paul Corbin, an industrialis ...

was on the telephone with the Premier Edouard Daladier. Lloyd who was fluent in French was able to talk to Daladier and told him if France held firm in ensuring the "guarantees" to Romania and Greece, then Britain would have to follow suit. As the British government did not wish to be seen operating out of sync with the French, the news that Daladier was going ahead with the "guarantee" forced London's hand. Atherton wrote about Lloyd's actions in April 1939: "The beneficiary was Romania, who received a guarantee unconditional on a closer defensive alliance with Poland, and which helped her to balance between the western powers, Germany, and Russia. In this instance, Lloyd had been working on behalf of Romania rather than Great Britain." However, Lloyd's attempts to lobby Halifax to issue a "guarantee" for Yugoslavia fell flat.

Reflecting his special case in the Balkans, when Britain declared war on Germany on 3 September 1939, Lloyd had the pamphlet ''The British Case'' explaining why Britain had declared war, translated into Greek, Bulgarian, Romanian, Serbo-Croatian

Serbo-Croatian () – also called Serbo-Croat (), Serbo-Croat-Bosnian (SCB), Bosnian-Croatian-Serbian (BCS), and Bosnian-Croatian-Montenegrin-Serbian (BCMS) – is a South Slavic language and the primary language of Serbia, Croatia, Bosnia an ...

, and Slovene and ensured that it was widely distributed all over the Balkans.Atherton, 1994 page 45. A recurring theme of Lloyd's letters to Halifax during the Phoney War

The Phoney War (french: Drôle de guerre; german: Sitzkrieg) was an eight-month period at the start of World War II, during which there was only one limited military land operation on the Western Front, when French troops invaded Germa ...

was that the Treasury was not providing enough money for the British Council's work in the Balkans. In September 1939, Tilea began to promote the idea of a "Balkan bloc" consisting of all the Balkan state that would be committed to upholding neutrality in the Second World War with the understanding that the Allies would come to their aid should their neutrality be violated.Atherton, 1994 page 38. Lloyd who was in close contact with Churchill who was appointed First Lord of the Admiralty

The First Lord of the Admiralty, or formally the Office of the First Lord of the Admiralty, was the political head of the English and later British Royal Navy. He was the government's senior adviser on all naval affairs, responsible for the di ...

on 3 September 1939, called together with Churchill for a "Balkan league" which would form a line to block any German expansion into the Balkans. On 27 September 1939, Tilea asked Sir Alexander Cadogan

Sir Alexander Montagu George Cadogan (25 November 1884 – 9 July 1968) was a British diplomat and civil servant. He was Permanent Under-Secretary for Foreign Affairs from 1938 to 1946. His long tenure of the Permanent Secretary's office makes ...

, the Foreign Office's Permanent Undersecretary "whether it would not be a good plan to send someone out to Bucharest, and he quoted as an example Lord Lloyd, who had the ear of the King and might be able to give good advice on the subject of Balkan reconciliation and consolidation". It is possible that Lloyd and Tilea had been working together for the same day that Tilea had asked for Lloyd to go to the Balkans, Lloyd had told Lord Halifax of his desire to go the Balkans saying "the urgency of which at the present moment obviously cannot be exaggerated."

Balkan tour

By October 1939, it was agreed that Lloyd would visit not just Romania, but all the Balkan states to work for a "Balkan pact".Atherton, 1994 page 40. Sir Reginald Hoare, the British minister in Bucharest, was opposed to the plan to send Lloyd to the Balkans, butGeorge William Rendel

Sir George William Rendel (23 February 1889 – 6 May 1979) was a British diplomat.Eid Al Yahya, ''Travellers in Arabia'', (Stacey International, 2006).

Early years

Rendel, the son of the engineer George Wightwick Rendel was educated at Down ...

, the minister in Sofia, and Sir Michael Palairet

Sir Michael Palairet (29 September 1882 – 5 August 1956) was a British diplomat who was minister to Romania, Sweden and Austria, and minister and ambassador to Greece.

Early life

Palairet was the son of Charles Harvey Palairet, by his mar ...

, the minister in Athens, were supportive. In the interval, Lloyd had visited Spain to ask the Spanish dictator General Francisco Franco

Francisco Franco Bahamonde (; 4 December 1892 – 20 November 1975) was a Spanish general who led the Nationalist forces in overthrowing the Second Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil War and thereafter ruled over Spain from 193 ...

if he was willing to "guarantee" the proposed "Balkan pact", an aspect of his visit to Madrid that he neglected to tell the Foreign Office about. The Foreign Office first learned of this plan from the Yugoslav Regent, Prince Paul, in November 1939. On 3 November 1939, Lord Halifax called a meeting to discuss the merits and demerits of the Balkan League plan, which Lloyd was allowed to attend by special permission of Halifax over the objections of Cadogan who argued that an outsider like Lord Lloyd should be attending a Foreign Office meeting.

On 14 November 1939, Lloyd's Balkan tour began with a visit to Bucharest.Atherton, 1994 page 42. Gafencu suggested a "machinery for common action", but negotiations broken down when King Carol learned that the British "guarantee" of Romania applied only against Germany, not the Soviet Union as he wanted. As Carol had not seen Hoare for some time, the extended talks that Lord Lloyd had with the king was felt to provide "useful information and impressions". In Belgrade and Sofia, Lloyd's visit was hampered by inability of Britain to supply weapons on the scale both the Prince Paul of Yugoslavia and King Boris III of Bulgaria wanted. Moreover, the unwillingness of Boris to renounce Bulgarian territorial claims against Yugoslavia, Greece and Romania rendered the idea of a neutralist Balkan league impractical.Atherton, 1994 page 43. After finishing his Balkan tour, Lloyd went to Syria to see Maxime Weygand

Maxime Weygand (; 21 January 1867 – 28 January 1965) was a French military commander in World War I and World War II.

Born in Belgium, Weygand was raised in France and educated at the Saint-Cyr military academy in Paris. After graduating in 1 ...

whose ''Armée de la Syrie'' was intended by the French General Staff before the war to go to Thessaloniki

Thessaloniki (; el, Θεσσαλονίκη, , also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece, with over one million inhabitants in its metropolitan area, and the capital of the geographic region of ...

.

Upon his return to Britain in December 1939, Lloyd backed French plans for a revival of the Salonika front

The Macedonian front, also known as the Salonica front (after Thessaloniki), was a military theatre of World War I formed as a result of an attempt by the Allied Powers to aid Serbia, in the autumn of 1915, against the combined attack of German ...

strategy of World War I, urging at meetings of the Supreme War Council for British and French troops to land at Thessaloniki. In this, he was against the British government, which opposed the French plans for a "second front" in the Balkans under the grounds that it was unclear if Italy intended to remain neutral or not. Lloyd enlisted the aid of Foreign Office officials such as Robert Bruce Lockhart

Sir Robert Hamilton Bruce Lockhart, KCMG (2 September 1887 – 27 February 1970) was a British diplomat, journalist, author, secret agent and footballer. His 1932 book ''Memoirs of a British Agent''Sir Robert Bruce Lockhart, ''Memoirs of a Bri ...

who summarised his thesis: "Lloyd says that the only argument in the Balkans is strength. If we do nothing we shall lose everything. If we are vigorous we have the support of the Balkans. Therefore, without too much consideration of Italy we must go ahead with the formation of the Near Eastern force." In response to objections from Sir Percy Loraine

Sir Percy Lyham Loraine, 12th Baronet, (5 November 1880 – 23 May 1961) was a British diplomat. He was British High Commissioner to Egypt from 1929 to 1933, British Ambassador to Turkey from 1933 to 1939 and British Ambassador to Italy from ...

, the British ambassador in Rome, that he was not certain how long Italy would remain neutral, Lloyd argued that Britain should just ignore the possibility of Italy entering the war and start troops to Thessaloniki at once.Atherton, 1994 page 44. At the same time, Lloyd advised Halifax that Britain should start shipping weapons to Yugoslavia at once to indicate that Britain was serious about defending the Balkans. In January 1940, Lloyd wrote to Loraine that Benito Mussolini only respected force and of his belief that if the Allies landed in the Balkans that this was likely to persuade Mussolini to continue Italian neutrality.

Evaluation

In January 1940, the attention of the Supreme War Council shifted towards Scandinavia, and the Balkan plan was abandoned. Lloyd's major interest in February–March 1940 was in building a "British Institute" in Bucharest to promote British culture, who was supported by Lord Halifax against objections from the Treasury that this was a waste of money in wartime. In an assessment of Lloyd's work in the Balkans, Atherton wrote: "His position was an ambivalent one: neither a diplomat nor a politician, but a peer with a semi-official position and influential political contacts. It was also increasingly irregular, but despite his opposition to the Munich agreement and, after September 1938, to further appeasement of Germany, Chamberlain never sought his removal".In cabinet

When Churchill became prime minister in May 1940, he appointed Lloyd asSecretary of State for the Colonies

The secretary of state for the colonies or colonial secretary was the British Cabinet minister in charge of managing the United Kingdom's various colonial dependencies.

History

The position was first created in 1768 to deal with the increas ...

and in December of that year he conferred on him the additional job of Leader of the House of Lords

The leader of the House of Lords is a member of the Cabinet of the United Kingdom who is responsible for arranging government business in the House of Lords. The post is also the leader of the majority party in the House of Lords who acts as ...

.

London Central Mosque

Lord Lloyd was a leading proponent of the futureLondon Central Mosque

The London Central Mosque (also known as the Regent's Park Mosque) is an Islamic place of worship located on the edge of Regent's Park in central London.

Design and location

It was designed by Sir Frederick Gibberd, completed in 1977, and ...

. As early as 1939 he worked with a Mosque Committee, comprising various prominent Muslims and ambassadors in London. After joining Churchill's cabinet, he sent a memo to the Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is ...

, pointing out that London contained "more uslimsthan any other European capital" but that in the British Empire "which actually contains more Moslems (''sic'') than Christians it was anomalous and inappropriate that there should be no central place of worship for Mussulmans 'sic''. He believed the gift of a site for the mosque would serve as "a tribute to the loyalty of the Moslems of the ritishEmpire and would have a good effect on Arab countries of the Middle East".

Other interests

In commerce, Lloyd was also director of theBritish South Africa Company

The British South Africa Company (BSAC or BSACo) was chartered in 1889 following the amalgamation of Cecil Rhodes' Central Search Association and the London-based Exploring Company Ltd, which had originally competed to capitalize on the expect ...

and Wagon Lit Holdings. In peacetime he habitually travelled in tropical countries every two months.

In his fifties he trained for and obtained a civil pilot's certificate in 1934, and in 1937 was appointed Honorary Air Commodore of No 600 (City of London) (Fighter) Squadron of the Auxiliary Air Force

The Royal Auxiliary Air Force (RAuxAF), formerly the Auxiliary Air Force (AAF), together with the Air Force Reserve, is a component of His Majesty's Reserve Air Forces (Reserve Forces Act 1996, Part 1, Para 1,(2),(c)). It provides a primary rein ...

, with which he insisted on training himself to qualify as a military pilot.

Family

In 1911, Lloyd married Blanche Isabella Lascelles, DGStJ, daughter of the Hon. Frederick Canning Lascelles, aRoyal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against Fr ...

Commander, and granddaughter of Henry Lascelles, 4th Earl of Harewood. Blanche was a lady in waiting to Alexandra of Denmark

Alexandra of Denmark (Alexandra Caroline Marie Charlotte Louise Julia; 1 December 1844 – 20 November 1925) was Queen of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Empress of India, from 22 January 1901 to 6 May 1910 as the wife of ...

from 1905 to 1911, and to Mary, Princess Royal and Countess of Harewood

Mary, Princess Royal and Countess of Harewood (Victoria Alexandra Alice Mary; 25 April 1897 – 28 March 1965), was a member of the British royal family. She was the only daughter of King George V and Queen Mary, the sister of Kings Edward VIII ...

(wife of Blanche's first cousin, Henry Lascelles, 6th Earl of Harewood) from 1941 to 1945.

Lloyd died of myeloid leukaemia at a clinic in Marylebone

Marylebone (usually , also , ) is a district in the West End of London, in the City of Westminster. Oxford Street, Europe's busiest shopping street, forms its southern boundary.

An ancient parish and latterly a metropolitan borough, it ...

, London, in February 1941, aged 61 and was buried at St Ippolyts, Hertfordshire

Hertfordshire ( or ; often abbreviated Herts) is one of the home counties in southern England. It borders Bedfordshire and Cambridgeshire to the north, Essex to the east, Greater London to the south, and Buckinghamshire to the west. For gov ...

. He was succeeded in the barony by his son, Alexander

Alexander is a male given name. The most prominent bearer of the name is Alexander the Great, the king of the Ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia who created one of the largest empires in ancient history.

Variants listed here are Aleksandar, Al ...

. Lady Lloyd died in December 1969, aged 89.

Some in the foreign office had thought Lloyd was a homosexual, and persisted in this view despite his marriage and the birth of his son. PAGE NUMBER REQUIRED He appears as the character 'Henry Fortescue' in Compton Mackenzie

Sir Edward Montague Compton Mackenzie, (17 January 1883 – 30 November 1972) was a Scottish writer of fiction, biography, histories and a memoir, as well as a cultural commentator, raconteur and lifelong Scottish nationalist. He was one of th ...

's novel ''Thin Ice''.

See also

*List of Cambridge University Boat Race crews

This is a list of the Cambridge University crews who have competed in The Boat Race since its inception in 1829.

Rowers are listed left to right in boat position from bow to stroke. The number following the rower indicates the rower's weight ...

Notes

References

*John Charmley

John Denis Charmley (born 9 November 1955) is a British academic and diplomatic historian. Since 2002 he has held various posts at the University of East Anglia: initially as Head of the School of History, then as the Head of the School of Mus ...

, ''Lord Lloyd and the Decline of the British Empire'', Weidenfeld, 1987.

*

*Goldstein, Erik "Neville Chamberlain, the British Official Mind and the Munich Crisis" pages 276–292 from ''The Munich Crisis, Prelude to World War II'' edited by Igor Lukes and Erik Goldstein, London: Frank Cass, 1999.

External links

* *The Papers of Lord Lloyd of Dolobran

held at

Churchill Archives Centre

The Churchill Archives Centre (CAC) at Churchill College at the University of Cambridge is one of the largest repositories in the United Kingdom for the preservation and study of modern personal papers. It is best known for housing the papers of ...

{{DEFAULTSORT:Lloyd, George Ambrose

1879 births

1941 deaths

Alumni of Trinity College, Cambridge

Arab Bureau officers

Barons Lloyd

British Army personnel of World War I

Cambridge University Boat Club rowers

Companions of the Distinguished Service Order

Conservative Party (UK) MPs for English constituencies

Diplomatic peers

Foreign Office personnel of World War II

Gay sportsmen

Governors of Bombay

High Commissioners of the United Kingdom to Egypt

Knights Grand Commander of the Order of the Indian Empire

Knights Grand Commander of the Order of the Star of India

Leaders of the House of Lords

LGBT politicians from England

Liberal Unionist Party MPs for English constituencies

Members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom

Ministers in the Churchill wartime government, 1940–1945

Secretaries of State for the Colonies

Stewards of Henley Royal Regatta

UK MPs 1910

UK MPs 1910–1918

UK MPs 1924–1929

UK MPs who were granted peerages

Warwickshire Yeomanry officers

Barons created by George V

People of the British Council

Lloyd family of Birmingham

People educated at Eton College