Georg Major on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

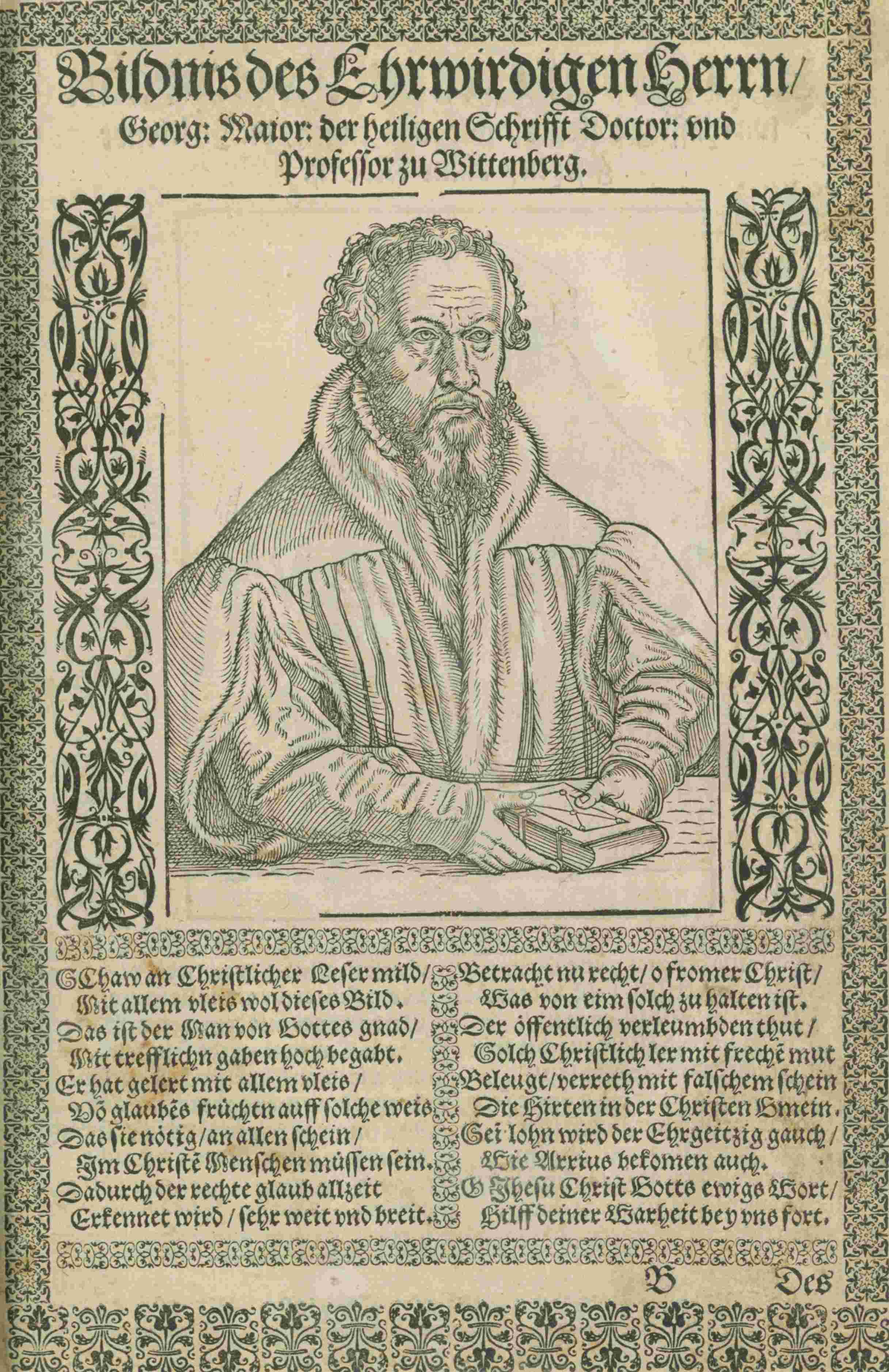

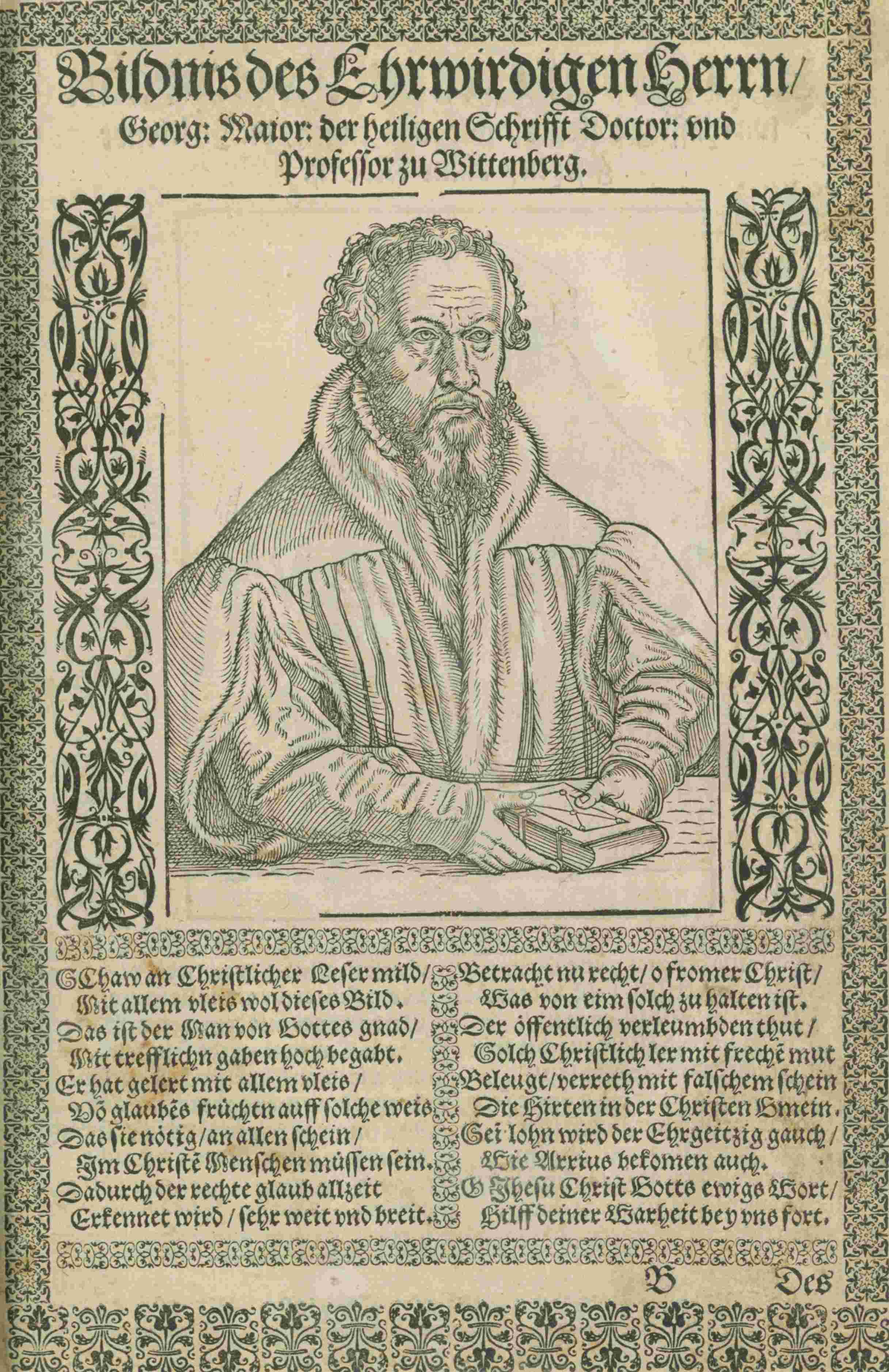

Georg Major (April 25, 1502 – November 28, 1574) was a

Georg Major (April 25, 1502 – November 28, 1574) was a

Georg Major (April 25, 1502 – November 28, 1574) was a

Georg Major (April 25, 1502 – November 28, 1574) was a Lutheran

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Catholic Church launched th ...

theologian of the Protestant Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...

.

Life

Major was born inNuremberg

Nuremberg ( ; german: link=no, Nürnberg ; in the local East Franconian dialect: ''Nämberch'' ) is the second-largest city of the German state of Bavaria after its capital Munich, and its 518,370 (2019) inhabitants make it the 14th-largest ...

in 1502. At the age of nine he was sent to Wittenberg

Wittenberg ( , ; Low Saxon language, Low Saxon: ''Wittenbarg''; meaning ''White Mountain''; officially Lutherstadt Wittenberg (''Luther City Wittenberg'')), is the fourth largest town in Saxony-Anhalt, Germany. Wittenberg is situated on the Ri ...

, and in 1521 he entered the university there.Robert Kolb

Robert Kolb is professor emeritus of Systematic Theology at Concordia Seminary, St. Louis, Missouri, and a world-renowned authority on Martin Luther and the history of the Reformation. Biography and education

Robert Kolb was born on June 17, ...

(1976). Georg Major as Controversialist: Polemics in the Late Reformation. ''Church History

__NOTOC__

Church history or ecclesiastical history as an academic discipline studies the history of Christianity and the way the Christian Church has developed since its inception.

Henry Melvill Gwatkin defined church history as "the spiritual ...

''

45 (4): 455–68 He was a student of Martin Luther

Martin Luther (; ; 10 November 1483 – 18 February 1546) was a German priest, theologian, author, hymnwriter, and professor, and Order of Saint Augustine, Augustinian friar. He is the seminal figure of the Reformation, Protestant Refo ...

and Philip Melanchthon

Philip Melanchthon. (born Philipp Schwartzerdt; 16 February 1497 – 19 April 1560) was a German Lutheran reformer, collaborator with Martin Luther, the first systematic theologian of the Protestant Reformation, intellectual leader of the Lu ...

,Dingel, Irene (2020). Georg Major on Church Fathers and Councils. ''Lutheran Quarterly'' 34 (2): 152–70 the latter being a particular influence. When Cruciger returned to Wittenberg in 1529, Major was appointed rector of the Johannisschule in Magdeburg

Magdeburg (; nds, label=Low Saxon, Meideborg ) is the capital and second-largest city of the German state Saxony-Anhalt. The city is situated at the Elbe river.

Otto I, the first Holy Roman Emperor and founder of the Archdiocese of Magdebur ...

, but in 1537 he became court preacher at Wittenberg and was ordained by Martin Luther

Martin Luther (; ; 10 November 1483 – 18 February 1546) was a German priest, theologian, author, hymnwriter, and professor, and Order of Saint Augustine, Augustinian friar. He is the seminal figure of the Reformation, Protestant Refo ...

. He began to lecture on theology in 1541.

In 1545 he joined the theological faculty, and his authority increased to such an extent that in the following year the elector sent him to the Conference of Regensburg

The Colloquy of Regensburg, historically called the Colloquy of Ratisbon, was a conference held at Regensburg (Ratisbon) in Bavaria in 1541, during the Protestant Reformation, which marks the culmination of attempts to restore religious unity in th ...

, where he was soon captivated by the personality of Butzer. Like Philipp Melanchthon

Philip Melanchthon. (born Philipp Schwartzerdt; 16 February 1497 – 19 April 1560) was a German Lutheran reformer, collaborator with Martin Luther, the first systematic theologian of the Protestant Reformation, intellectual leader of the Lu ...

, he fled before the disastrous close of the Schmalkald war

The Schmalkaldic War (german: link=no, Schmalkaldischer Krieg) was the short period of violence from 1546 until 1547 between the forces of Emperor Charles V of the Holy Roman Empire (simultaneously King Charles I of Spain), commanded by the D ...

, and found refuge in Magdeburg. In the summer of 1547, he returned to Wittenberg, and in the same year became cathedral superintendent at Merseburg

Merseburg () is a town in central Germany in southern Saxony-Anhalt, situated on the river Saale, and approximately 14 km south of Halle (Saale) and 30 km west of Leipzig. It is the capital of the Saalekreis district. It had a diocese ...

, although he resumed his activity at the university in the following year.

In the negotiations of the Augsburg Interim

The Augsburg Interim (full formal title: ''Declaration of His Roman Imperial Majesty on the Observance of Religion Within the Holy Empire Until the Decision of the General Council'') was an imperial decree ordered on 15 May 1548 at the 1548 Diet ...

, he took the part of Melanchthon in first opposing it and then making concessions. This attitude incurred the enmity of the opponents of the Interim, especially after he cancelled a number of passages in the second edition of his ''Psalterium'' in which he had violently attacked the position of Maurice, Elector of Saxony

Maurice (21 March 1521 – 9 July 1553) was Duke (1541–47) and later Elector (1547–53) of Saxony. His clever manipulation of alliances and disputes gained the Albertine branch of the Wettin dynasty extensive lands and the electoral dignity.

...

, whom he now requested to prohibit all polemical treatises proceeding from Magdeburg, while he condemned the preachers of Torgau who were imprisoned in Wittenberg on account of their opposition to the Interim. He was even accused of accepting bribes from Maurice.

In 1552, Count Hans Georg, who favored the Interim, appointed him superintendent of Eisleben

Eisleben is a town in Saxony-Anhalt, Germany. It is famous as both the hometown of the influential theologian Martin Luther and the place where he died; hence, its official name is Lutherstadt Eisleben. First mentioned in the late 10th century, E ...

, on the recommendation of Melchior Kling. The orthodox clergy of the County of Mansfeld

Mansfeld, sometimes also unofficially Mansfeld-Lutherstadt, is a town in the district of Mansfeld-Südharz, in Saxony-Anhalt, Germany.

Protestant reformator Martin Luther grew up in Mansfeld, and in 1993 the town became one of sixteen places in ...

, however, immediately suspected him of being an interimist and adiaphorist, and he tried to defend his position in public, but his apology resulted in a dispute called the Majoristic Controversy.

At Christmas

Christmas is an annual festival commemorating Nativity of Jesus, the birth of Jesus, Jesus Christ, observed primarily on December 25 as a religious and cultural celebration among billions of people Observance of Christmas by country, around t ...

, 1552, Count Albrecht expelled him without trial and he fled to Wittenberg, where he resumed his activity as professor and member of the Wittenberg Consistory

Consistory is the anglicized form of the consistorium, a council of the closest advisors of the Roman emperors. It can also refer to:

*A papal consistory, a formal meeting of the Sacred College of Cardinals of the Roman Catholic Church

*Consistory ...

. Thence forth he was an important and active member in the circle of the Wittenberg Philippists

The Philippists formed a party in early Lutheranism. Their opponents were called Gnesio-Lutherans.

Before Luther's death

''Philippists'' was the designation usually applied in the latter half of the sixteenth century to the followers of Philip ...

.

From 1558 to 1574 he was dean of the theological faculty and repeatedly held the rectorate of the university. He lived long enough to experience the first overthrow of Crypto-Calvinism

Crypto-Calvinism is a pejorative term describing a segment of those members of the Lutheran Church in Germany who were accused of secretly subscribing to Calvinist doctrine of the Eucharist in the decades immediately after the death of Martin Luth ...

in the Electorate of Saxony

The Electorate of Saxony, also known as Electoral Saxony (German: or ), was a territory of the Holy Roman Empire from 1356–1806. It was centered around the cities of Dresden, Leipzig and Chemnitz.

In the Golden Bull of 1356, Emperor Charles ...

, and Paul Crell, his son-in-law, signed for him at Torgau in May 1574 the articles which repudiated Calvinism

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John Cal ...

and acknowledged the unity of Luther and Melanchthon.

He died at Wittenberg in 1574.

Works

His significant writings include: * A text edition of ''Justini ex Trogo Pompejo historia'' (Hagenau, 1526); * an edition of Luther's smaller catechism in Latin and Low German (Magdeburg, 1531); * ''Sententiae veterum poetarum'' (1534); * ''Quaestiones rhetoricae'' (1535); * ''Vita Patrum'' (Wittenberg, 1544); * ''Psalterium Davidis juxta translationem veterem repurgatum'' (1547); * ''De origine et auctoritate verbi Dei'' (1550); * ''Commonefactio ad ecclesiam catholicam, orthodoxam, de fugiendis ... blasphemiis Samosatenicis'' (1569). He also wrote commentaries on the Pauline epistles and homilies on the pericopes.References

{{DEFAULTSORT:Major, Georg 1502 births 1574 deaths German Lutheran theologians Philippists Clergy from Nuremberg University of Wittenberg alumni University of Wittenberg faculty 16th-century German Protestant theologians German male non-fiction writers 16th-century German male writers 16th-century Lutheran theologians