Geographic South Pole on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The South Pole, also known as the Geographic South Pole, Terrestrial South Pole or 90th Parallel South, is one of the two points where Earth's axis of rotation intersects its surface. It is the southernmost point on Earth and lies antipodally on the opposite side of Earth from the

The South Pole, also known as the Geographic South Pole, Terrestrial South Pole or 90th Parallel South, is one of the two points where Earth's axis of rotation intersects its surface. It is the southernmost point on Earth and lies antipodally on the opposite side of Earth from the

For most purposes, the Geographic South Pole is defined as the southern point of the two points where Earth's

For most purposes, the Geographic South Pole is defined as the southern point of the two points where Earth's

National Science Foundation, Office of Polar Programs The polar ice sheet is moving at a rate of roughly per year in a direction between 37° and 40° west of grid north, down towards the The Geographic South Pole is marked by a stake in the ice alongside a small sign; these are repositioned each year in a ceremony on

The Geographic South Pole is marked by a stake in the ice alongside a small sign; these are repositioned each year in a ceremony on

page 6, Antarctic Sun. 8 January 2006; McMurdo Station, Antarctica. The sign records the respective dates that

British explorer

British explorer

National Science Foundation Office of Polar Programs, 9 April 1993 The former dome seen in pictures of the Amundsen–Scott station is partially buried due to snow storms, and the entrance to the dome had to be regularly bulldozed to uncover it. More recent buildings are raised on stilts so that the snow does not build up against their sides.

NOAA South Pole Webcam

360° Panoramas of the South Pole

Images of this location

are available at the

South Pole Photo Gallery

Poles

by the Australian Antarctic Division

The Antarctic Sun

nbsp;– Online news source for the U.S. Antarctic Program

Big Dead Place

UK team makes polar trek history

nbsp;– BBC News article on first expedition to Pole of Inaccessibility without mechanical assistance * Listen to Ernest Shackleton describing his 190

South Pole Expedition

and read more about the recording on ustralianscreen online * The recording describing Shackleton's 1908 South Pole Expedition was added to the

The South Pole, also known as the Geographic South Pole, Terrestrial South Pole or 90th Parallel South, is one of the two points where Earth's axis of rotation intersects its surface. It is the southernmost point on Earth and lies antipodally on the opposite side of Earth from the

The South Pole, also known as the Geographic South Pole, Terrestrial South Pole or 90th Parallel South, is one of the two points where Earth's axis of rotation intersects its surface. It is the southernmost point on Earth and lies antipodally on the opposite side of Earth from the North Pole

The North Pole, also known as the Geographic North Pole or Terrestrial North Pole, is the point in the Northern Hemisphere where the Earth's axis of rotation meets its surface. It is called the True North Pole to distinguish from the Mag ...

, at a distance of 12,430 miles (20,004 km) in all directions.

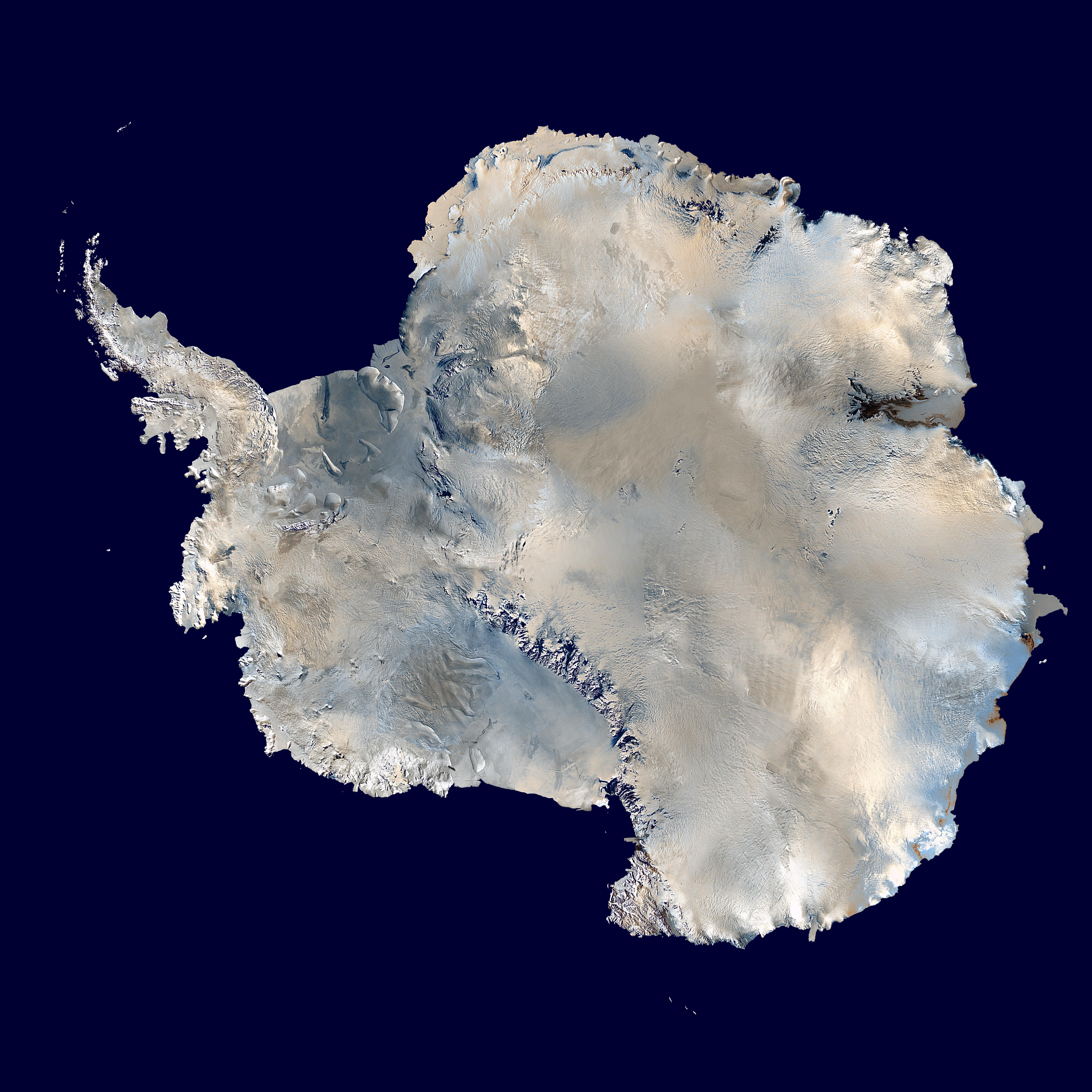

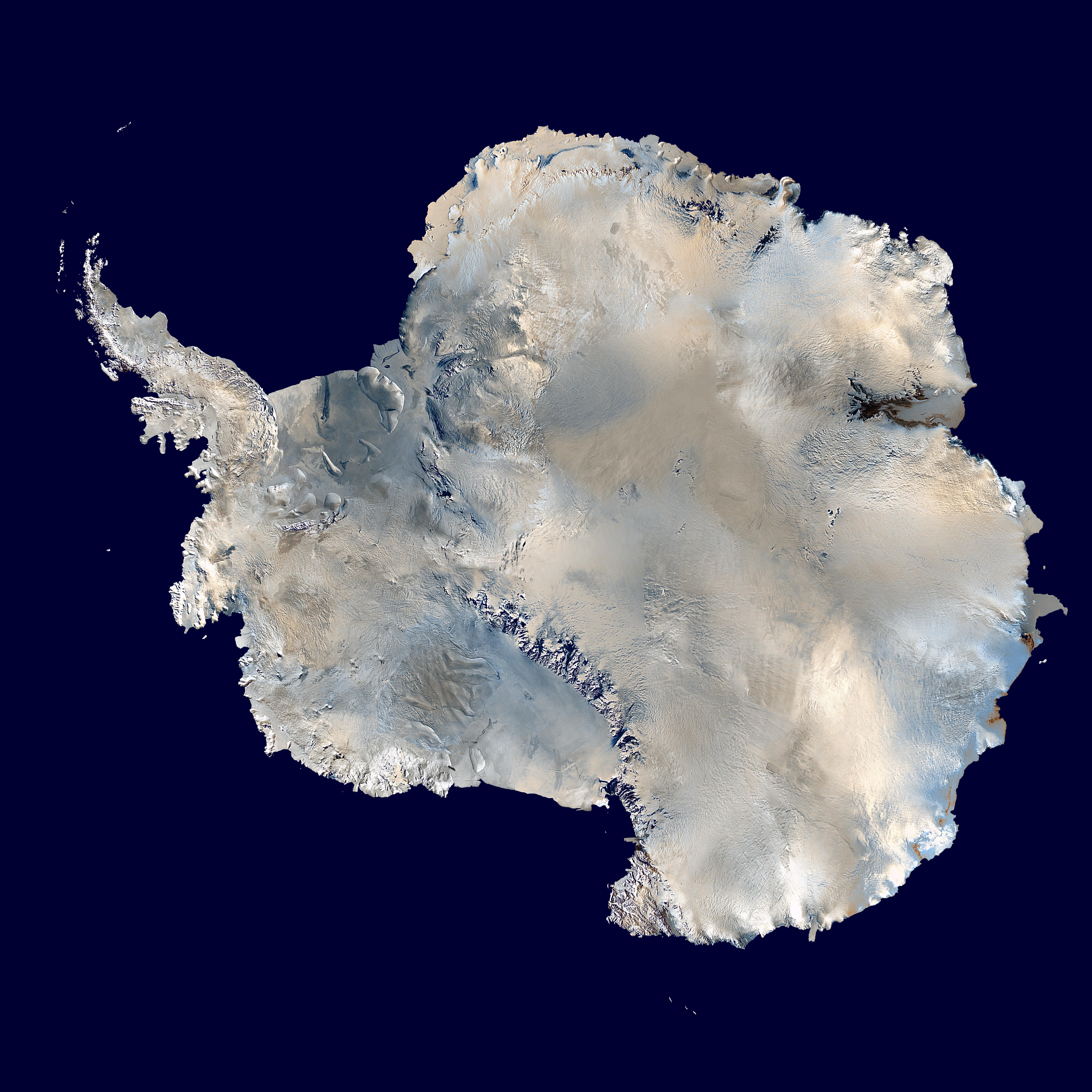

Situated on the continent of Antarctica

Antarctica () is Earth's southernmost and least-populated continent. Situated almost entirely south of the Antarctic Circle and surrounded by the Southern Ocean, it contains the geographic South Pole. Antarctica is the fifth-largest contine ...

, it is the site of the United States Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station

The Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station is the United States scientific research station at the South Pole of the Earth. It is the southernmost point under the jurisdiction (not sovereignty) of the United States. The station is located on the ...

, which was established in 1956 and has been permanently staffed since that year. The Geographic South Pole is distinct from the South Magnetic Pole, the position of which is defined based on Earth's magnetic field

A magnetic field is a vector field that describes the magnetic influence on moving electric charges, electric currents, and magnetic materials. A moving charge in a magnetic field experiences a force perpendicular to its own velocity and to ...

. The South Pole is at the centre of the Southern Hemisphere.

Geography

For most purposes, the Geographic South Pole is defined as the southern point of the two points where Earth's

For most purposes, the Geographic South Pole is defined as the southern point of the two points where Earth's axis of rotation

Rotation around a fixed axis is a special case of rotational motion. The fixed-axis hypothesis excludes the possibility of an axis changing its orientation and cannot describe such phenomena as wobbling or precession. According to Euler's rota ...

intersects its surface (the other being the Geographic North Pole

The North Pole, also known as the Geographic North Pole or Terrestrial North Pole, is the point in the Northern Hemisphere where the Earth's axis of rotation meets its surface. It is called the True North Pole to distinguish from the Mag ...

). However, Earth's axis of rotation is actually subject to very small "wobbles" (polar motion

Polar motion of the Earth is the motion of the Earth's rotational axis relative to its crust. This is measured with respect to a reference frame in which the solid Earth is fixed (a so-called ''Earth-centered, Earth-fixed'' or ECEF reference f ...

), so this definition is not adequate for very precise work.

The geographic coordinate

The geographic coordinate system (GCS) is a spherical or ellipsoidal coordinate system for measuring and communicating positions directly on the Earth as latitude and longitude. It is the simplest, oldest and most widely used of the various ...

s of the South Pole are usually given simply as 90°S, since its longitude is geometrically undefined and irrelevant. When a longitude is desired, it may be given as At the South Pole, all directions face north. For this reason, directions at the Pole are given relative to "grid north", which points northward along the prime meridian

A prime meridian is an arbitrary meridian (a line of longitude) in a geographic coordinate system at which longitude is defined to be 0°. Together, a prime meridian and its anti-meridian (the 180th meridian in a 360°-system) form a great c ...

. Along tight latitude circles, clockwise is east, and anti-clockwise is west, opposite to the North Pole

The North Pole, also known as the Geographic North Pole or Terrestrial North Pole, is the point in the Northern Hemisphere where the Earth's axis of rotation meets its surface. It is called the True North Pole to distinguish from the Mag ...

.

The Geographic South Pole is presently located on the continent of Antarctica

Antarctica () is Earth's southernmost and least-populated continent. Situated almost entirely south of the Antarctic Circle and surrounded by the Southern Ocean, it contains the geographic South Pole. Antarctica is the fifth-largest contine ...

, although this has not been the case for all of Earth's history

The history of Earth concerns the development of planet Earth from its formation to the present day. Nearly all branches of natural science have contributed to understanding of the main events of Earth's past, characterized by constant geologic ...

because of continental drift

Continental drift is the hypothesis that the Earth's continents have moved over geologic time relative to each other, thus appearing to have "drifted" across the ocean bed. The idea of continental drift has been subsumed into the science of pla ...

. It sits atop a featureless, barren, windswept and icy plateau at an altitude of above sea level, and is located about from the nearest open sea at the Bay of Whales

The Bay of Whales was a natural ice harbour, or iceport, indenting the front of the Ross Ice Shelf just north of Roosevelt Island, Antarctica. It is the southernmost point of open ocean not only of the Ross Sea, but worldwide. The Ross Sea ex ...

. The ice is estimated to be about thick at the Pole, so the land surface under the ice sheet

In glaciology, an ice sheet, also known as a continental glacier, is a mass of glacial ice that covers surrounding terrain and is greater than . The only current ice sheets are in Antarctica and Greenland; during the Last Glacial Period at Las ...

is actually near sea level.Amundsen–Scott South Pole StationNational Science Foundation, Office of Polar Programs The polar ice sheet is moving at a rate of roughly per year in a direction between 37° and 40° west of grid north, down towards the

Weddell Sea

The Weddell Sea is part of the Southern Ocean and contains the Weddell Gyre. Its land boundaries are defined by the bay formed from the coasts of Coats Land and the Antarctic Peninsula. The easternmost point is Cape Norvegia at Princess Martha ...

. Therefore, the position of the station and other artificial features relative to the geographic pole gradually shift over time.

The Geographic South Pole is marked by a stake in the ice alongside a small sign; these are repositioned each year in a ceremony on

The Geographic South Pole is marked by a stake in the ice alongside a small sign; these are repositioned each year in a ceremony on New Year's Day

New Year's Day is a festival observed in most of the world on 1 January, the first day of the year in the modern Gregorian calendar. 1 January is also New Year's Day on the Julian calendar, but this is not the same day as the Gregorian one. Wh ...

to compensate for the movement of the ice."Marker makes annual move"page 6, Antarctic Sun. 8 January 2006; McMurdo Station, Antarctica. The sign records the respective dates that

Roald Amundsen

Roald Engelbregt Gravning Amundsen (, ; ; 16 July 1872 – ) was a Norwegian explorer of polar regions. He was a key figure of the period known as the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration.

Born in Borge, Østfold, Norway, Amundsen bega ...

and Robert F. Scott reached the Pole, followed by a short quotation from each man, and gives the elevation as "9,301 ''FT.''". A new marker stake is designed and fabricated each year by staff at the site.

Ceremonial South Pole

The Ceremonial South Pole is an area set aside for photo opportunities at theSouth Pole Station

South is one of the cardinal directions or compass points. The direction is the opposite of north and is perpendicular to both east and west.

Etymology

The word ''south'' comes from Old English ''sūþ'', from earlier Proto-Germanic ''*sunþaz ...

. It is located some meters from the Geographic South Pole, and consists of a metallic sphere on a short barber pole, surrounded by the flags of the original Antarctic Treaty

russian: link=no, Договор об Антарктике es, link=no, Tratado Antártico

, name = Antarctic Treaty System

, image = Flag of the Antarctic Treaty.svgborder

, image_width = 180px

, caption ...

signatory states.

Historic monuments

Amundsen's Tent

The tent was erected by the Norwegian expedition led by Roald Amundsen on its arrival on 14 December 1911. It is currently buried beneath the snow and ice in the vicinity of the Pole. It has been designated a Historic Site or Monument (HSM 80), following a proposal by Norway to the Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting. The precise location of the tent is unknown, but based on calculations of the rate of movement of the ice and the accumulation of snow, it is believed, as of 2010, to lie between 1.8 and 2.5 km (1.1 and 1.5 miles) from the Pole at a depth of 17 m (56 ft) below the present surface.Argentine Flagpole

Aflagpole

A flagpole, flagmast, flagstaff, or staff is a pole designed to support a flag. If it is taller than can be easily reached to raise the flag, a cord is used, looping around a pulley at the top of the pole with the ends tied at the bottom. The fla ...

erected at the South Geographical Pole in December 1965 by the First Argentine Overland Polar Expedition has been designated a Historic Site or Monument (HSM 1) following a proposal by Argentina to the Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting.

Exploration

Pre-1900

In 1820, several expeditions claimed to have been the first to have sighted Antarctica, with the first being the Russian expedition led byFabian Gottlieb von Bellingshausen

Fabian Gottlieb Thaddeus von Bellingshausen (russian: Фадде́й Фадде́евич Беллинсга́узен, translit=Faddéy Faddéevich Bellinsgáuzen; – ) was a Russian naval officer, cartographer and explorer, who ultimately ...

and Mikhail Lazarev

Admiral Mikhail Petrovich Lazarev (russian: Михаил Петрович Лазарев, 3 November 1788 – 11 April 1851) was a Russian Naval fleet, fleet commander and an explorer.

Education and early career

Lazarev was born in Vladimir, R ...

. The first landing was probably just over a year later when American captain John Davis, a sealer, set foot on the ice.

The basic geography of the Antarctic coastline was not understood until the mid-to-late 19th century. American naval officer Charles Wilkes

Charles Wilkes (April 3, 1798 – February 8, 1877) was an American naval officer, ship's captain, and explorer. He led the United States Exploring Expedition (1838–1842).

During the American Civil War (1861–1865), he commanded ' during the ...

claimed (correctly) that Antarctica was a new continent, basing the claim on his exploration in 1839–40, while James Clark Ross

Sir James Clark Ross (15 April 1800 – 3 April 1862) was a British Royal Navy officer and polar explorer known for his explorations of the Arctic, participating in two expeditions led by his uncle John Ross, and four led by William Edwa ...

, in his expedition of 1839–1843, hoped that he might be able to sail all the way to the South Pole. (He was unsuccessful.)

1900–1950

British explorer

British explorer Robert Falcon Scott

Captain Robert Falcon Scott, , (6 June 1868 – c. 29 March 1912) was a British Royal Navy officer and explorer who led two expeditions to the Antarctic regions: the ''Discovery'' expedition of 1901–1904 and the ill-fated ''Terra Nov ...

on the ''Discovery'' Expedition of 1901–1904 was the first to attempt to find a route from the Antarctic coastline to the South Pole. Scott, accompanied by Ernest Shackleton

Sir Ernest Henry Shackleton (15 February 1874 – 5 January 1922) was an Anglo-Irish Antarctic explorer who led three British expeditions to the Antarctic. He was one of the principal figures of the period known as the Heroic Age of ...

and Edward Wilson, set out with the aim of travelling as far south as possible, and on 31 December 1902, reached 82°16′ S. Shackleton later returned to Antarctica as leader of the British Antarctic Expedition ( ''Nimrod'' Expedition) in a bid to reach the Pole. On 9 January 1909, with three companions, he reached 88°23' S – from the Pole – before being forced to turn back.

The first men to reach the Geographic South Pole were the Norwegian Roald Amundsen and his party on 14 December 1911. Amundsen named his camp Polheim

Polheim ("Home at the Pole") was Roald Amundsen's name for his camp (the first ever) at the South Pole. He arrived there on December 14, 1911, along with four other members of his expedition: Helmer Hanssen, Olav Bjaaland, Oscar Wisting, and Sverr ...

and the entire plateau surrounding the Pole King Haakon VII Vidde in honour of King Haakon VII of Norway

Haakon VII (; born Prince Carl of Denmark; 3 August 187221 September 1957) was the King of Norway from November 1905 until his death in September 1957.

Originally a Danish prince, he was born in Copenhagen as the son of the future Frederick V ...

. Robert Falcon Scott returned to Antarctica with his second expedition, the ''Terra Nova'' Expedition, initially unaware of Amundsen's secretive expedition. Scott and four other men reached the South Pole on 17 January 1912, thirty-four days after Amundsen. On the return trip, Scott and his four companions all died of starvation and extreme cold.

In 1914 Ernest Shackleton's Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition

The Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition of 1914–1917 is considered to be the last major expedition of the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration. Conceived by Sir Ernest Shackleton, the expedition was an attempt to make the first land crossing ...

set out with the goal of crossing Antarctica via the South Pole, but his ship, the ''Endurance

Endurance (also related to sufferance, resilience, constitution, fortitude, and hardiness) is the ability of an organism to exert itself and remain active for a long period of time, as well as its ability to resist, withstand, recover from a ...

'', was frozen in pack ice

Drift ice, also called brash ice, is sea ice that is not attached to the shoreline or any other fixed object (shoals, grounded icebergs, etc.).Leppäranta, M. 2011. The Drift of Sea Ice. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. Unlike fast ice, which is "fasten ...

and sank 11 months later. The overland journey was never made.

US Admiral Richard Evelyn Byrd

Richard Evelyn Byrd Jr. (October 25, 1888 – March 11, 1957) was an American naval officer and explorer. He was a recipient of the Medal of Honor, the highest honor for valor given by the United States, and was a pioneering American aviator, p ...

, with the assistance of his first pilot Bernt Balchen

Bernt Balchen (23 October 1899 – 17 October 1973) was a Norwegian pioneer polar aviator, navigator, aircraft mechanical engineer and military leader. A Norwegian native, he later became an American citizen and was a recipient of the Distingu ...

, became the first person to fly over the South Pole on 29 November 1929.

1950–present

It was not until 31 October 1956 that humans once again set foot at the South Pole, when a party led by AdmiralGeorge J. Dufek

George John Dufek (10 February 1903, Rockford, Illinois – 10 February 1977, Bethesda, Maryland) was an American naval officer, naval aviator, and polar expert. He served in World War II and the Korean War and in the 1940s and 1950s spent much ...

of the US Navy landed there in an R4D-5L Skytrain (C-47 Skytrain

The Douglas C-47 Skytrain or Dakota (Royal Air Force, RAF, Royal Australian Air Force, RAAF, Royal Canadian Air Force, RCAF, Royal New Zealand Air Force, RNZAF, and South African Air Force, SAAF designation) is a airlift, military transport ai ...

) aircraft. The US Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station

The Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station is the United States scientific research station at the South Pole of the Earth. It is the southernmost point under the jurisdiction (not sovereignty) of the United States. The station is located on the ...

was established by air over 1956–1957 for the International Geophysical Year

The International Geophysical Year (IGY; french: Année géophysique internationale) was an international scientific project that lasted from 1 July 1957 to 31 December 1958. It marked the end of a long period during the Cold War when scientific ...

and has been continuously staffed since then by research and support personnel.

After Amundsen and Scott, the next people to reach the South Pole ''overland'' (albeit with some air support) were Edmund Hillary

Sir Edmund Percival Hillary (20 July 1919 – 11 January 2008) was a New Zealand mountaineer, explorer, and philanthropist. On 29 May 1953, Hillary and Sherpa mountaineer Tenzing Norgay became the first climbers confirmed to have reached t ...

(4 January 1958) and Vivian Fuchs

Sir Vivian Ernest Fuchs ( ; 11 February 1908 – 11 November 1999) was an English scientist-explorer and expedition organizer. He led the Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition which reached the South Pole overland in 1958.

Biography

Fuchs ...

(19 January 1958) and their respective parties, during the Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition

The Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition (CTAE) of 1955–1958 was a Commonwealth-sponsored expedition that successfully completed the first overland crossing of Antarctica, via the South Pole. It was the first expedition to reach the South ...

. There have been many subsequent expeditions to arrive at the South Pole by surface transportation, including those by Havola, Crary and Fiennes Fiennes or Ffiennes may refer to:

Places

* Fiennes, a commune of the Pas-de-Calais ''département'' in northern France.

People

A toponymic surname pronounced and borne by a prominent English family, descendant from Eustace I Fiennes, a nobleman ...

. The first group of women to reach the pole were Pam Young, Jean Pearson, Lois Jones, Eileen McSaveney, Kay Lindsay and Terry Tickhill in 1969. In 1978–79 Michele Eileen Raney became the first woman to winter at the South Pole.

Subsequent to the establishment, in 1987, of the logistic support base at Patriot Hills Base Camp

Patriot Hills Base Camp was a private seasonally occupied camp in Antarctica. It was located in the Heritage Range of the Ellsworth Mountains, next to the Patriot Hills that gave it its name.

The camp was run by the private company Adventure Ne ...

, the South Pole became more accessible to non-government expeditions.

On 30 December 1989, Arved Fuchs

Arved Fuchs (born 26 April 1953) is a German polar explorer and writer.

Polar exploration

On 30 December 1989, Fuchs and Reinhold Messner were the first to reach the South Pole with neither animal nor motorised help, using skis and a pa ...

and Reinhold Messner

Reinhold Andreas Messner (; born 17 September 1944) is an Italian mountaineer, explorer, and author from South Tyrol. He made the first solo ascent of Mount Everest and, along with Peter Habeler, the first ascent of Everest without supplemental ...

were the first to traverse Antarctica via the South Pole without animal or motorized help, using only skis and the help of wind. Two women, Victoria E. Murden and Shirley Metz, reached the pole by land on 17 January 1989.

The fastest unsupported journey to the Geographic South Pole from the ocean is 24 days and one hour from Hercules Inlet

Hercules Inlet is a large, narrow, ice-filled inlet which forms a part of the southwestern margin of the Ronne Ice Shelf. It is bounded on the west by the south-eastern flank of the Heritage Range, and on the north by Skytrain Ice Rise. Hercules ...

and was set in 2011 by Norwegian adventurer Christian Eide, who beat the previous solo record set in 2009 by American Todd Carmichael

Todd Carmichael is an American entrepreneur, adventure traveler, philanthropist, television personality, author, inventor, and producer.

Carmichael is the CEO and co-founder for Philadelphia-based La Colombe. He is the first American to complete ...

of 39 days and seven hours, and the previous group record also set in 2009 of 33 days and 23 hours.

The fastest solo, unsupported and unassisted trek to the south pole by a female was performed by Hannah McKeand from the UK in 2006. She made the journey in 39 days 9 hours 33 minutes. She started on 19 November 2006 and finished on 28 December 2006.

In the 2011–12 summer, separate expeditions by Norwegian Aleksander Gamme

Aleksander Gamme (born July 23, 1976) is a Norwegian adventurer, polar explorer, researcher, author and public speaker.

In 2007, he climbed Mount Everest with Stian Voldmo. While he was there he worked on an interactive teaching project "Hamar til ...

and Australians James Castrission and Justin Jones jointly claimed the first unsupported trek without dogs or kites from the Antarctic coast to the South Pole and back. The two expeditions started from Hercules Inlet

Hercules Inlet is a large, narrow, ice-filled inlet which forms a part of the southwestern margin of the Ronne Ice Shelf. It is bounded on the west by the south-eastern flank of the Heritage Range, and on the north by Skytrain Ice Rise. Hercules ...

a day apart, with Gamme starting first, but completing according to plan the last few kilometres together. As Gamme traveled alone he thus simultaneously became the first to complete the task solo.

On 28 December 2018, Captain Lou Rudd became the first Briton to cross the Antarctic unassisted via the south pole, and the second person to make the journey in 56 days. On 10 January 2020, Mollie Hughes

Mollie Hughes (born 3 July 1990) is a British mountaineer and sports adventurer who in 2017 broke the world record for becoming the youngest woman to climb both sides of Mount Everest, and in 2020 became the youngest woman to ski solo to the Sout ...

became the youngest person to ski to the pole, aged 29.

Climate and day and night

During winter (May through August), the South Pole receives no sunlight at all, and is completely dark apart from moonlight. In summer (November through February), the sun is continuously above the horizon and appears to move in a counter-clockwise circle. However, it is always low in the sky, reaching a maximum of 23.5° around the December solstice because of the 23.5° tilt of the earth's axis. Much of the sunlight that does reach the surface is reflected by the white snow. This lack of warmth from the sun, combined with the high altitude (about ), means that the South Pole has one of the coldest climates on Earth (though it is not quite the coldest; that record goes to the region in the vicinity of theVostok Station

Vostok Station (russian: :ru:Восток (антарктическая станция), ста́нция Восто́к, translit=stántsiya Vostók, , meaning "Station East") is a Russian Research stations in Antarctica, research station in ...

, also in Antarctica, which lies at a higher elevation).

The South Pole is at an altitude of but feels like . Centrifugal force from the spin of the planet pulls the atmosphere toward the equator. The South Pole is colder than the North Pole

The North Pole, also known as the Geographic North Pole or Terrestrial North Pole, is the point in the Northern Hemisphere where the Earth's axis of rotation meets its surface. It is called the True North Pole to distinguish from the Mag ...

primarily because of the elevation difference and for being in the middle of a continent. The North Pole is a few feet from sea level in the middle of an ocean.

In midsummer, as the sun reaches its maximum elevation of about 23.5 degrees, high temperatures at the South Pole in January average at . As the six-month "day" wears on and the sun gets lower, temperatures drop as well: they reach around sunset (late March) and sunrise (late September). In midwinter, the average temperature remains steady at around . The highest temperature ever recorded at the Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station was on Christmas Day, 2011, and the lowest was on 23 June 1982 (for comparison, the lowest temperature directly recorded anywhere on earth was at Vostok Station

Vostok Station (russian: :ru:Восток (антарктическая станция), ста́нция Восто́к, translit=stántsiya Vostók, , meaning "Station East") is a Russian Research stations in Antarctica, research station in ...

on 21 July 1983, though was measured indirectly by satellite in East Antarctica

East Antarctica, also called Greater Antarctica, constitutes the majority (two-thirds) of the Antarctic continent, lying on the Indian Ocean side of the continent, separated from West Antarctica by the Transantarctic Mountains. It lies almost ...

between Dome A

Dome A or Dome Argus is the loftiest ice dome on the Antarctic Plateau, located inland. It is thought to be the coldest naturally occurring place on Earth, with temperatures believed to reach . It is the highest ice feature in Antarctica, consis ...

and Dome F

Dome Fuji (ドームふじ ''Dōmu Fuji''), also called Dome F or Valkyrie Dome, is an Antarctic base located in the eastern part of Queen Maud Land at . With an altitude of above sea level, it is the second-highest summit or ''ice dome'' of ...

in August 2010). Mean annual temperature at the South Pole is –49.5 °C (–57.1 °F).

The South Pole has an ice cap climate

An ice cap climate is a polar climate where no mean monthly temperature exceeds . The climate covers areas in or near the high latitudes (65° latitude) to polar regions (70–90° north and south latitude), such as Antarctica, some of the northe ...

(Köppen climate classification

The Köppen climate classification is one of the most widely used climate classification systems. It was first published by German-Russian climatologist Wladimir Köppen (1846–1940) in 1884, with several later modifications by Köppen, notabl ...

'' EF''). It resembles a desert, receiving very little precipitation. Air humidity is near zero. However, high winds can cause the blowing of snowfall, and the accumulation of snow amounts to about 7 cm (2.8 in) per year.Initial environmental evaluation – development of blue-ice and compacted-snow runwaysNational Science Foundation Office of Polar Programs, 9 April 1993 The former dome seen in pictures of the Amundsen–Scott station is partially buried due to snow storms, and the entrance to the dome had to be regularly bulldozed to uncover it. More recent buildings are raised on stilts so that the snow does not build up against their sides.

Time

In most places on Earth, local time is determined bylongitude

Longitude (, ) is a geographic coordinate that specifies the east–west position of a point on the surface of the Earth, or another celestial body. It is an angular measurement, usually expressed in degrees and denoted by the Greek letter l ...

, such that the time of day is more-or-less synchronised to the perceived position of the Sun in the sky (for example, at midday the Sun is roughly perceived to be at its highest). This line of reasoning fails at the South Pole, where the Sun is seen to rise and set only once per year with solar elevation varying only with day of the year, not time of day. Because there are more than 24 time zones in the world and they all meet up at the South Pole, it can be any hour, any minute, any second at the South Pole. There is no ''a priori

("from the earlier") and ("from the later") are Latin phrases used in philosophy to distinguish types of knowledge, justification, or argument by their reliance on empirical evidence or experience. knowledge is independent from current ...

'' reason for placing the South Pole in any particular time zone, but as a matter of practical convenience the Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station keeps New Zealand Time

Time in New Zealand is divided by law into two standard time, standard time zones. The main islands use New Zealand Standard Time (NZST), 12 hours in advance of Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) / List of military time zones, military M (Mike), ...

(UTC+12/UTC+13). This is because the US flies its resupply missions ("Operation Deep Freeze

Operation Deep Freeze (OpDFrz or ODF) is codename for a series of United States missions to Antarctica, beginning with "Operation Deep Freeze I" in 1955–56, followed by "Operation Deep Freeze II", "Operation Deep Freeze III", and so on. (There w ...

") out of McMurdo Station

McMurdo Station is a United States Antarctic research station on the south tip of Ross Island, which is in the New Zealand-claimed Ross Dependency on the shore of McMurdo Sound in Antarctica. It is operated by the United States through the Unit ...

, which is supplied from Christchurch

Christchurch ( ; mi, Ōtautahi) is the largest city in the South Island of New Zealand and the seat of the Canterbury Region. Christchurch lies on the South Island's east coast, just north of Banks Peninsula on Pegasus Bay. The Avon River / ...

, New Zealand.

Flora and fauna

Due to its exceptionally harsh climate, there are no native resident plants or animals at the South Pole. Off-coursesouth polar skua

The south polar skua (''Stercorarius maccormicki'') is a large seabird in the skua family, Stercorariidae. An older name for the bird is MacCormick's skua, after explorer and naval surgeon Robert McCormick, who first collected the type specimen. ...

s and snow petrel

The snow petrel (''Pagodroma nivea'') is the only member of the genus ''Pagodroma.'' It is one of only three birds that has been seen at the Geographic South Pole, along with the Antarctic petrel and the south polar skua, which have the most so ...

s are occasionally seen there.

In 2000 it was reported that microbe

A microorganism, or microbe,, ''mikros'', "small") and ''organism'' from the el, ὀργανισμός, ''organismós'', "organism"). It is usually written as a single word but is sometimes hyphenated (''micro-organism''), especially in olde ...

s had been detected living in the South Pole ice. Scientists published in the journal ''Gondwana Research

''Gondwana Research'' is a peer-reviewed scientific journal with an "all earth science" scope and an emphasis on the origin and evolution of continents. It is part of the Elsevier

Elsevier () is a Dutch academic publishing company specializin ...

'' that evidence had been found of dinosaurs with feathers to protect the animals from the extreme cold. The fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

s had been found over 100 years ago in Koonwarra

Koonwarra is a town in the South Gippsland region of Victoria, Australia. At the , Koonwarra had a population of 404. The town straddles the South Gippsland Highway. Located around 128 km southeast of Melbourne, the town was served by rail ...

, Australia, but in sediment

Sediment is a naturally occurring material that is broken down by processes of weathering and erosion, and is subsequently transported by the action of wind, water, or ice or by the force of gravity acting on the particles. For example, sand an ...

which had accumulated under a lake which had been near to the South Pole millions of years ago.

See also

*List of Antarctic expeditions

This list of Antarctic expeditions is a chronological list of expeditions involving Antarctica. Although the existence of a southern continent had been hypothesized as early as the writings of Ptolemy in the 1st century AD, the South Pole was no ...

* South Pole Telescope

The South Pole Telescope (SPT) is a diameter telescope located at the Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station, Antarctica. The telescope is designed for observations in the microwave, millimeter-wave, and submillimeter-wave regions of the electrom ...

References

External links

NOAA South Pole Webcam

360° Panoramas of the South Pole

Images of this location

are available at the

Degree Confluence Project

The Degree Confluence Project is a World Wide Web-based, all-volunteer project which aims to have people visit each of the integer degree intersections of latitude and longitude on Earth, posting photographs and a narrative of each visit online. ...

South Pole Photo Gallery

Poles

by the Australian Antarctic Division

The Antarctic Sun

nbsp;– Online news source for the U.S. Antarctic Program

Big Dead Place

UK team makes polar trek history

nbsp;– BBC News article on first expedition to Pole of Inaccessibility without mechanical assistance * Listen to Ernest Shackleton describing his 190

South Pole Expedition

and read more about the recording on ustralianscreen online * The recording describing Shackleton's 1908 South Pole Expedition was added to the

National Film and Sound Archive

The National Film and Sound Archive of Australia (NFSA), known as ScreenSound Australia from 1999 to 2004, is Australia's audiovisual archive, responsible for developing, preserving, maintaining, promoting and providing access to a national co ...

's Sounds of Australia

The Sounds of Australia, formerly the National Registry of Recorded Sound, is the National Film and Sound Archive's selection of sound recordings which are deemed to have cultural, historical and aesthetic significance and relevance for Australi ...

registry in 2007

{{Authority control

East Antarctica

Extreme points of Earth

Geography of Antarctica

Polar regions of the Earth

Historic Sites and Monuments of Antarctica