Geneva Convention relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

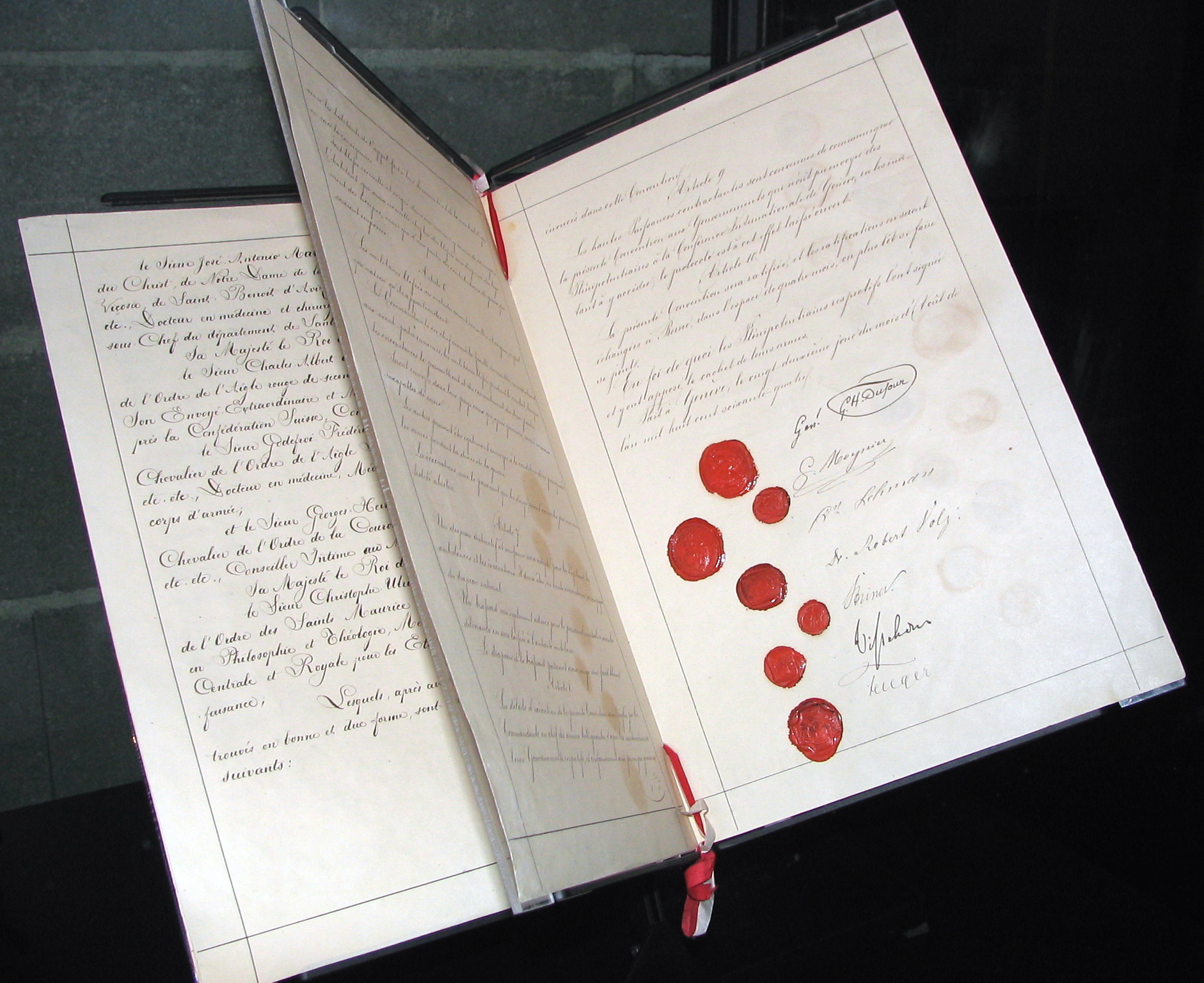

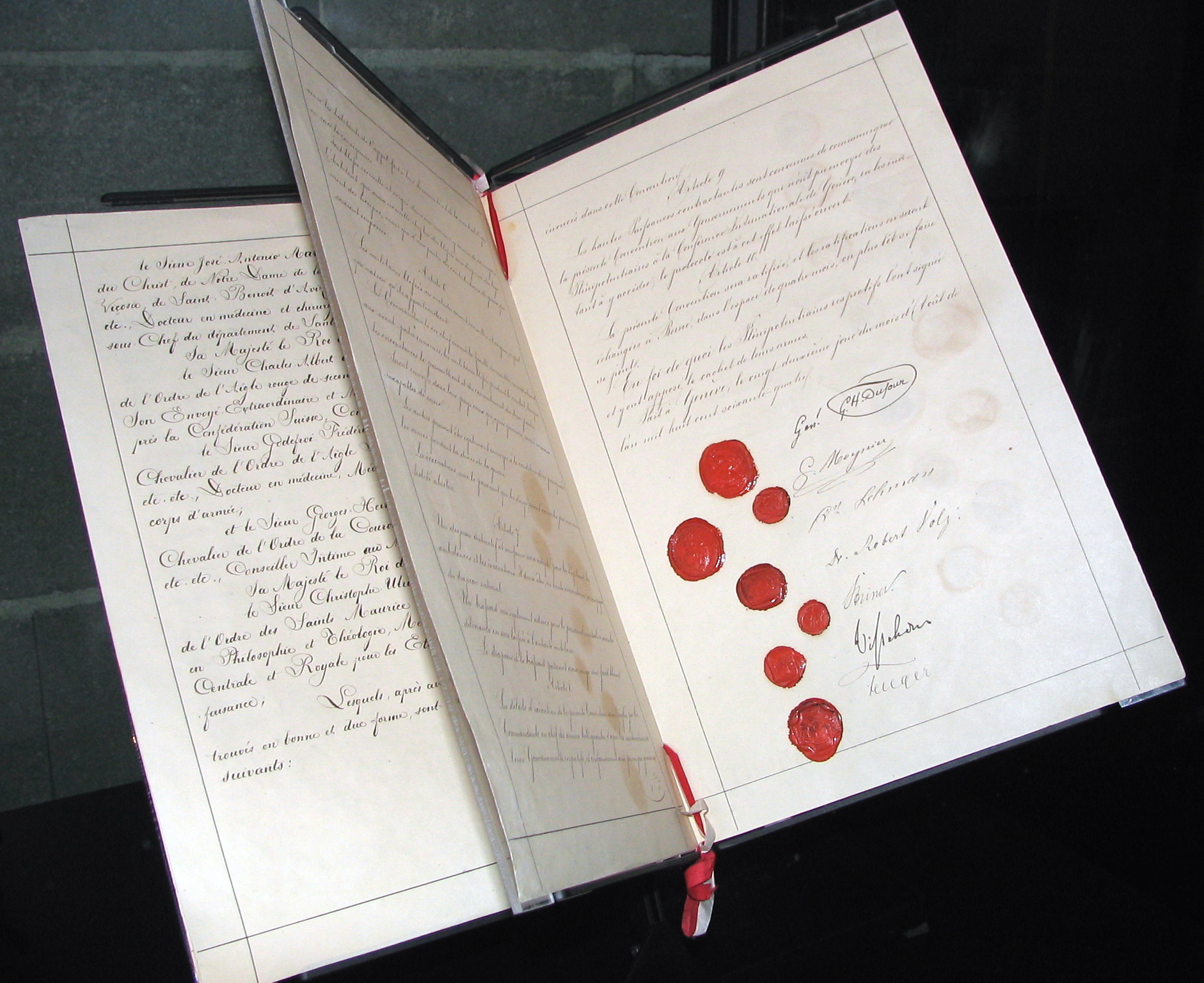

file:Geneva Convention 1864 - CH-BAR - 29355687.pdf, upright=1.15, Original document in single pages, 1864

The Geneva Conventions are four Treaty, treaties, and three additional Protocol (diplomacy), protocols, that establish international law, international legal standards for humanitarian treatment in war. The singular term ''Geneva Convention'' usually denotes the agreements of 1949, negotiated in the aftermath of the Second World War (1939–1945), which updated the terms of the two 1929 treaties and added two new conventions. The Geneva Conventions extensively define the basic rights of wartime prisoners (civilians and military personnel), established protections for the wounded and sick, and provided Humanitarian protection, protections for the civilians in and around a war-zone; moreover, the Geneva Convention also defines the rights and protections afforded to non-combatants. The treaties of 1949 were ratified, in their entirety or with Reservation (law), reservations, List of parties to the Geneva Conventions, by 196 countries. The Geneva Conventions concern only prisoners and non-combatants in war; they do not address the use of weapons of war, which are instead addressed by the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907, which concern conventional weapons, and the Geneva Protocol, which concerns Biological warfare, biological and chemical warfare.

file:Geneva Convention 1864 - CH-BAR - 29355687.pdf, upright=1.15, Original document in single pages, 1864

The Geneva Conventions are four Treaty, treaties, and three additional Protocol (diplomacy), protocols, that establish international law, international legal standards for humanitarian treatment in war. The singular term ''Geneva Convention'' usually denotes the agreements of 1949, negotiated in the aftermath of the Second World War (1939–1945), which updated the terms of the two 1929 treaties and added two new conventions. The Geneva Conventions extensively define the basic rights of wartime prisoners (civilians and military personnel), established protections for the wounded and sick, and provided Humanitarian protection, protections for the civilians in and around a war-zone; moreover, the Geneva Convention also defines the rights and protections afforded to non-combatants. The treaties of 1949 were ratified, in their entirety or with Reservation (law), reservations, List of parties to the Geneva Conventions, by 196 countries. The Geneva Conventions concern only prisoners and non-combatants in war; they do not address the use of weapons of war, which are instead addressed by the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907, which concern conventional weapons, and the Geneva Protocol, which concerns Biological warfare, biological and chemical warfare.

The Switzerland, Swiss businessman Henry Dunant went to visit wounded soldiers after the Battle of Solferino in 1859. He was shocked by the lack of facilities, personnel, and medical aid available to help these soldiers. As a result, he published his book, ''A Memory of Solferino'', in 1862, on the horrors of war. His wartime experiences inspired Dunant to propose:

* A permanent relief agency for humanitarian aid in times of war

* A government treaty recognizing the neutrality (international relations), neutrality of the agency and allowing it to provide aid in a war zone

The former proposal led to the establishment of the Red Cross in Geneva. The latter led to the First Geneva Convention, 1864 Geneva Convention, the first codified international treaty that covered the sick and wounded soldiers on the battlefield. On 22 August 1864, the Swiss government invited the governments of all European countries, as well as the United States, Brazil, and Mexico, to attend an official diplomatic conference. Sixteen countries sent a total of twenty-six delegates to Geneva. On 22 August 1864, the conference adopted the first Geneva Convention "for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded in Armies in the Field". Representatives of 12 states and kingdoms signed the convention:

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

For both of these accomplishments, Henry Dunant became co recipient of the first Nobel Peace Prize in 1901.

On 20 October 1868 the first unsuccessful attempt to expand the 1864 treaty was undertaken. With the 'Additional Articles relating to the Condition of the Wounded in War' an attempt was initiated to clarify some rules of the 1864 convention and to extend them to maritime warfare. The Articles were signed but were only ratified by the Netherlands and the United States of America. The Netherlands later withdrew their ratification. The protection of the victims of maritime warfare would later be realized by the third Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907#Hague Convention of 1899, Hague Convention of 1899 and the tenth Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907#Hague Convention of 1907, Hague Convention of 1907.

In 1906 thirty-five states attended a conference convened by the Swiss government. On 6 July 1906 it resulted in the adoption of the "Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armies in the Field", which improved and supplemented, for the first time, the 1864 convention. It remained in force until 1970 when Costa Rica acceded to the 1949 Geneva Conventions.

The 1929 conference yielded two conventions that were signed on 27 July 1929. One, the "Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armies in the Field", was the third version to replace the original convention of 1864. The other was adopted after experiences in World War I had shown the deficiencies in the protection of prisoners of war under the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907. The "Convention relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War" was not to replace these earlier conventions signed at The Hague, rather it supplemented them.

Inspired by the wave of humanitarian and pacifistic enthusiasm following World War II and the outrage towards the war crimes disclosed by the Nuremberg Trials, a series of conferences were held in 1949 reaffirming, expanding and updating the prior Geneva and Hague Conventions. It yielded four distinct conventions:

*The First Geneva Convention "for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armed Forces in the Field" was the fourth update of the original 1864 convention and replaced the 1929 convention on the same subject matter.

*The Second Geneva Convention "for the Amelioration of the Condition of Wounded, Sick and Shipwrecked Members of Armed Forces at Sea" replaced the Hague Convention (X) of 1907. It was the first Geneva Convention on the protection of the victims of maritime warfare and mimicked the structure and provisions of the First Geneva Convention.

*The Third Geneva Convention "relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War" replaced the 1929 Geneva Convention that dealt with prisoners of war.

*In addition to these three conventions, the conference also added a new elaborate Fourth Geneva Convention "relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War". It was the first Geneva Convention not to deal with combatants, rather it had the protection of civilians as its subject matter. The 1899 and 1907 Hague Conventions had already contained some provisions on the protection of civilians and occupied territory. Article 154 specifically provides that the Fourth Geneva Convention is supplementary to these provisions in the Hague Conventions.

Despite the length of these documents, they were found over time to be incomplete. In fact, the very nature of war, armed conflicts had changed with the beginning of the Cold War era, leading many to believe that the 1949 Geneva Conventions were addressing a largely extinct reality: on the one hand, most armed conflicts had become internal, or civil wars, while on the other, most wars had become increasingly asymmetric warfare, asymmetric. Moreover, modern armed conflicts were inflicting an increasingly higher toll on civilians, which brought the need to provide civilian persons and objects with tangible protections in time of combat, thus bringing a much needed update to the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907. In light of these developments, two Protocols were adopted in 1977 that extended the terms of the 1949 Conventions with additional protections. In 2005, a third brief Protocol was added establishing an additional protective sign for medical services, the Emblems of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement#Red Crystal, Red Crystal, as an alternative to the ubiquitous Emblems of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement, Red Cross and Red Crescent emblems, for those countries that find them objectionable.

The Switzerland, Swiss businessman Henry Dunant went to visit wounded soldiers after the Battle of Solferino in 1859. He was shocked by the lack of facilities, personnel, and medical aid available to help these soldiers. As a result, he published his book, ''A Memory of Solferino'', in 1862, on the horrors of war. His wartime experiences inspired Dunant to propose:

* A permanent relief agency for humanitarian aid in times of war

* A government treaty recognizing the neutrality (international relations), neutrality of the agency and allowing it to provide aid in a war zone

The former proposal led to the establishment of the Red Cross in Geneva. The latter led to the First Geneva Convention, 1864 Geneva Convention, the first codified international treaty that covered the sick and wounded soldiers on the battlefield. On 22 August 1864, the Swiss government invited the governments of all European countries, as well as the United States, Brazil, and Mexico, to attend an official diplomatic conference. Sixteen countries sent a total of twenty-six delegates to Geneva. On 22 August 1864, the conference adopted the first Geneva Convention "for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded in Armies in the Field". Representatives of 12 states and kingdoms signed the convention:

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

For both of these accomplishments, Henry Dunant became co recipient of the first Nobel Peace Prize in 1901.

On 20 October 1868 the first unsuccessful attempt to expand the 1864 treaty was undertaken. With the 'Additional Articles relating to the Condition of the Wounded in War' an attempt was initiated to clarify some rules of the 1864 convention and to extend them to maritime warfare. The Articles were signed but were only ratified by the Netherlands and the United States of America. The Netherlands later withdrew their ratification. The protection of the victims of maritime warfare would later be realized by the third Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907#Hague Convention of 1899, Hague Convention of 1899 and the tenth Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907#Hague Convention of 1907, Hague Convention of 1907.

In 1906 thirty-five states attended a conference convened by the Swiss government. On 6 July 1906 it resulted in the adoption of the "Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armies in the Field", which improved and supplemented, for the first time, the 1864 convention. It remained in force until 1970 when Costa Rica acceded to the 1949 Geneva Conventions.

The 1929 conference yielded two conventions that were signed on 27 July 1929. One, the "Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armies in the Field", was the third version to replace the original convention of 1864. The other was adopted after experiences in World War I had shown the deficiencies in the protection of prisoners of war under the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907. The "Convention relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War" was not to replace these earlier conventions signed at The Hague, rather it supplemented them.

Inspired by the wave of humanitarian and pacifistic enthusiasm following World War II and the outrage towards the war crimes disclosed by the Nuremberg Trials, a series of conferences were held in 1949 reaffirming, expanding and updating the prior Geneva and Hague Conventions. It yielded four distinct conventions:

*The First Geneva Convention "for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armed Forces in the Field" was the fourth update of the original 1864 convention and replaced the 1929 convention on the same subject matter.

*The Second Geneva Convention "for the Amelioration of the Condition of Wounded, Sick and Shipwrecked Members of Armed Forces at Sea" replaced the Hague Convention (X) of 1907. It was the first Geneva Convention on the protection of the victims of maritime warfare and mimicked the structure and provisions of the First Geneva Convention.

*The Third Geneva Convention "relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War" replaced the 1929 Geneva Convention that dealt with prisoners of war.

*In addition to these three conventions, the conference also added a new elaborate Fourth Geneva Convention "relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War". It was the first Geneva Convention not to deal with combatants, rather it had the protection of civilians as its subject matter. The 1899 and 1907 Hague Conventions had already contained some provisions on the protection of civilians and occupied territory. Article 154 specifically provides that the Fourth Geneva Convention is supplementary to these provisions in the Hague Conventions.

Despite the length of these documents, they were found over time to be incomplete. In fact, the very nature of war, armed conflicts had changed with the beginning of the Cold War era, leading many to believe that the 1949 Geneva Conventions were addressing a largely extinct reality: on the one hand, most armed conflicts had become internal, or civil wars, while on the other, most wars had become increasingly asymmetric warfare, asymmetric. Moreover, modern armed conflicts were inflicting an increasingly higher toll on civilians, which brought the need to provide civilian persons and objects with tangible protections in time of combat, thus bringing a much needed update to the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907. In light of these developments, two Protocols were adopted in 1977 that extended the terms of the 1949 Conventions with additional protections. In 2005, a third brief Protocol was added establishing an additional protective sign for medical services, the Emblems of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement#Red Crystal, Red Crystal, as an alternative to the ubiquitous Emblems of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement, Red Cross and Red Crescent emblems, for those countries that find them objectionable.

The Geneva Conventions are rules that apply only in times of armed conflict and seek to protect people who are not or are no longer taking part in hostilities; these include the sick and wounded of armed forces on the field, wounded, sick, and shipwrecked members of armed forces at sea, prisoners of war, and civilians. The first convention dealt with the treatment of wounded and sick armed forces in the field. The second convention dealt with the sick, wounded, and shipwrecked members of armed forces at sea. The third convention dealt with the treatment of prisoners of war during times of conflict. The fourth convention dealt with the treatment of civilians and their protection during wartime.

During the negotiations for the 1949 conventions, Britain and France successfully removed language from early drafts that they saw as unfavorable to their colonial rule.

The Geneva Conventions are rules that apply only in times of armed conflict and seek to protect people who are not or are no longer taking part in hostilities; these include the sick and wounded of armed forces on the field, wounded, sick, and shipwrecked members of armed forces at sea, prisoners of war, and civilians. The first convention dealt with the treatment of wounded and sick armed forces in the field. The second convention dealt with the sick, wounded, and shipwrecked members of armed forces at sea. The third convention dealt with the treatment of prisoners of war during times of conflict. The fourth convention dealt with the treatment of civilians and their protection during wartime.

During the negotiations for the 1949 conventions, Britain and France successfully removed language from early drafts that they saw as unfavorable to their colonial rule.

Not all violations of the treaty are treated equally. The most serious crimes are termed ''grave breaches'' and provide a legal definition of a war crime. Grave breaches of the Third and Fourth Geneva Conventions include the following acts if committed against a person protected by the convention:

* willful killing, torture or inhumane treatment, including Human subject research, biological experiments

* willfully causing great suffering or serious injury to body or health

* compelling a protected person to serve in the armed forces of a hostile power

* willfully depriving a protected person of the right to a fair trial if accused of a war crime.

Also considered grave breaches of the Fourth Geneva Convention are the following:

* taking of hostages

* extensive destruction and appropriation of property not justified by military necessity and carried out unlawfully and wantonly

* unlawful deportation, Population transfer, transfer, or Solitary confinement, confinement.How "grave breaches" are defined in the Geneva Conventions and Additional Protocols

Not all violations of the treaty are treated equally. The most serious crimes are termed ''grave breaches'' and provide a legal definition of a war crime. Grave breaches of the Third and Fourth Geneva Conventions include the following acts if committed against a person protected by the convention:

* willful killing, torture or inhumane treatment, including Human subject research, biological experiments

* willfully causing great suffering or serious injury to body or health

* compelling a protected person to serve in the armed forces of a hostile power

* willfully depriving a protected person of the right to a fair trial if accused of a war crime.

Also considered grave breaches of the Fourth Geneva Convention are the following:

* taking of hostages

* extensive destruction and appropriation of property not justified by military necessity and carried out unlawfully and wantonly

* unlawful deportation, Population transfer, transfer, or Solitary confinement, confinement.How "grave breaches" are defined in the Geneva Conventions and Additional Protocols

International Committee of the Red Cross. Nations who are party to these treaties must enact and enforce legislation penalizing any of these crimes. Nations are also obligated to search for persons alleged to commit these crimes, or persons having Command responsibility, ordered them to be committed, and to bring them to trial regardless of their nationality and regardless of the place where the crimes took place. The principle of universal jurisdiction also applies to the enforcement of grave breaches when the UN Security Council, United Nations Security Council asserts its authority and jurisdiction from the UN Charter to apply universal jurisdiction. The UNSC did this when they established the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda and the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia to investigate and/or prosecute alleged violations.

, consulted July 2014 The application of the Geneva Conventions in the Russo-Ukrainian War (2014–present) has been troublesome because some of the personnel who engaged in combat against the Ukrainians were not identified by insignia, although they did wear military-style fatigues. The types of comportment qualified as acts of perfidy under doctrine are listed in Articles 37 through 39 of the Geneva Convention; the prohibition of fake insignia is listed at Article 39.2, but the law is silent on the complete absence of insignia. The status of POWs captured in this circumstance remains a question. Educational institutions and organizations including Harvard University, the International Committee of the Red Cross, and the Rohr Jewish Learning Institute use the Geneva Convention as a primary text investigating torture and warfare.

Do the Geneva Conventions Matter?

' Oxford University Press. * Giovanni Mantilla, "doi:10.1093/ejil/chx027, Conforming Instrumentalists: Why the USA and the United Kingdom Joined the 1949 Geneva Conventions," European Journal of International Law, Volume 28, Issue 2, May 2017, Pages 483–511. * Helen Kinsella,

The image before the weapon : a critical history of the distinction between combatant and civilian

Cornell University Press. * Boyd van Dijk (2022).

Preparing for War: The Making of the Geneva Conventions

'. Oxford University Press.

Texts and commentaries of 1949 Conventions & Additional Protocols

The Geneva Conventions: the core of international humanitarian law

ICRC

€”video * Commentaries: *

GCI: Commentary

*

GCII: Commentary

*

GCIII: Commentary

*

GCIV: Commentary

{{Authority control Geneva Conventions,

file:Geneva Convention 1864 - CH-BAR - 29355687.pdf, upright=1.15, Original document in single pages, 1864

The Geneva Conventions are four Treaty, treaties, and three additional Protocol (diplomacy), protocols, that establish international law, international legal standards for humanitarian treatment in war. The singular term ''Geneva Convention'' usually denotes the agreements of 1949, negotiated in the aftermath of the Second World War (1939–1945), which updated the terms of the two 1929 treaties and added two new conventions. The Geneva Conventions extensively define the basic rights of wartime prisoners (civilians and military personnel), established protections for the wounded and sick, and provided Humanitarian protection, protections for the civilians in and around a war-zone; moreover, the Geneva Convention also defines the rights and protections afforded to non-combatants. The treaties of 1949 were ratified, in their entirety or with Reservation (law), reservations, List of parties to the Geneva Conventions, by 196 countries. The Geneva Conventions concern only prisoners and non-combatants in war; they do not address the use of weapons of war, which are instead addressed by the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907, which concern conventional weapons, and the Geneva Protocol, which concerns Biological warfare, biological and chemical warfare.

file:Geneva Convention 1864 - CH-BAR - 29355687.pdf, upright=1.15, Original document in single pages, 1864

The Geneva Conventions are four Treaty, treaties, and three additional Protocol (diplomacy), protocols, that establish international law, international legal standards for humanitarian treatment in war. The singular term ''Geneva Convention'' usually denotes the agreements of 1949, negotiated in the aftermath of the Second World War (1939–1945), which updated the terms of the two 1929 treaties and added two new conventions. The Geneva Conventions extensively define the basic rights of wartime prisoners (civilians and military personnel), established protections for the wounded and sick, and provided Humanitarian protection, protections for the civilians in and around a war-zone; moreover, the Geneva Convention also defines the rights and protections afforded to non-combatants. The treaties of 1949 were ratified, in their entirety or with Reservation (law), reservations, List of parties to the Geneva Conventions, by 196 countries. The Geneva Conventions concern only prisoners and non-combatants in war; they do not address the use of weapons of war, which are instead addressed by the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907, which concern conventional weapons, and the Geneva Protocol, which concerns Biological warfare, biological and chemical warfare.

History

The Switzerland, Swiss businessman Henry Dunant went to visit wounded soldiers after the Battle of Solferino in 1859. He was shocked by the lack of facilities, personnel, and medical aid available to help these soldiers. As a result, he published his book, ''A Memory of Solferino'', in 1862, on the horrors of war. His wartime experiences inspired Dunant to propose:

* A permanent relief agency for humanitarian aid in times of war

* A government treaty recognizing the neutrality (international relations), neutrality of the agency and allowing it to provide aid in a war zone

The former proposal led to the establishment of the Red Cross in Geneva. The latter led to the First Geneva Convention, 1864 Geneva Convention, the first codified international treaty that covered the sick and wounded soldiers on the battlefield. On 22 August 1864, the Swiss government invited the governments of all European countries, as well as the United States, Brazil, and Mexico, to attend an official diplomatic conference. Sixteen countries sent a total of twenty-six delegates to Geneva. On 22 August 1864, the conference adopted the first Geneva Convention "for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded in Armies in the Field". Representatives of 12 states and kingdoms signed the convention:

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

For both of these accomplishments, Henry Dunant became co recipient of the first Nobel Peace Prize in 1901.

On 20 October 1868 the first unsuccessful attempt to expand the 1864 treaty was undertaken. With the 'Additional Articles relating to the Condition of the Wounded in War' an attempt was initiated to clarify some rules of the 1864 convention and to extend them to maritime warfare. The Articles were signed but were only ratified by the Netherlands and the United States of America. The Netherlands later withdrew their ratification. The protection of the victims of maritime warfare would later be realized by the third Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907#Hague Convention of 1899, Hague Convention of 1899 and the tenth Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907#Hague Convention of 1907, Hague Convention of 1907.

In 1906 thirty-five states attended a conference convened by the Swiss government. On 6 July 1906 it resulted in the adoption of the "Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armies in the Field", which improved and supplemented, for the first time, the 1864 convention. It remained in force until 1970 when Costa Rica acceded to the 1949 Geneva Conventions.

The 1929 conference yielded two conventions that were signed on 27 July 1929. One, the "Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armies in the Field", was the third version to replace the original convention of 1864. The other was adopted after experiences in World War I had shown the deficiencies in the protection of prisoners of war under the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907. The "Convention relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War" was not to replace these earlier conventions signed at The Hague, rather it supplemented them.

Inspired by the wave of humanitarian and pacifistic enthusiasm following World War II and the outrage towards the war crimes disclosed by the Nuremberg Trials, a series of conferences were held in 1949 reaffirming, expanding and updating the prior Geneva and Hague Conventions. It yielded four distinct conventions:

*The First Geneva Convention "for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armed Forces in the Field" was the fourth update of the original 1864 convention and replaced the 1929 convention on the same subject matter.

*The Second Geneva Convention "for the Amelioration of the Condition of Wounded, Sick and Shipwrecked Members of Armed Forces at Sea" replaced the Hague Convention (X) of 1907. It was the first Geneva Convention on the protection of the victims of maritime warfare and mimicked the structure and provisions of the First Geneva Convention.

*The Third Geneva Convention "relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War" replaced the 1929 Geneva Convention that dealt with prisoners of war.

*In addition to these three conventions, the conference also added a new elaborate Fourth Geneva Convention "relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War". It was the first Geneva Convention not to deal with combatants, rather it had the protection of civilians as its subject matter. The 1899 and 1907 Hague Conventions had already contained some provisions on the protection of civilians and occupied territory. Article 154 specifically provides that the Fourth Geneva Convention is supplementary to these provisions in the Hague Conventions.

Despite the length of these documents, they were found over time to be incomplete. In fact, the very nature of war, armed conflicts had changed with the beginning of the Cold War era, leading many to believe that the 1949 Geneva Conventions were addressing a largely extinct reality: on the one hand, most armed conflicts had become internal, or civil wars, while on the other, most wars had become increasingly asymmetric warfare, asymmetric. Moreover, modern armed conflicts were inflicting an increasingly higher toll on civilians, which brought the need to provide civilian persons and objects with tangible protections in time of combat, thus bringing a much needed update to the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907. In light of these developments, two Protocols were adopted in 1977 that extended the terms of the 1949 Conventions with additional protections. In 2005, a third brief Protocol was added establishing an additional protective sign for medical services, the Emblems of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement#Red Crystal, Red Crystal, as an alternative to the ubiquitous Emblems of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement, Red Cross and Red Crescent emblems, for those countries that find them objectionable.

The Switzerland, Swiss businessman Henry Dunant went to visit wounded soldiers after the Battle of Solferino in 1859. He was shocked by the lack of facilities, personnel, and medical aid available to help these soldiers. As a result, he published his book, ''A Memory of Solferino'', in 1862, on the horrors of war. His wartime experiences inspired Dunant to propose:

* A permanent relief agency for humanitarian aid in times of war

* A government treaty recognizing the neutrality (international relations), neutrality of the agency and allowing it to provide aid in a war zone

The former proposal led to the establishment of the Red Cross in Geneva. The latter led to the First Geneva Convention, 1864 Geneva Convention, the first codified international treaty that covered the sick and wounded soldiers on the battlefield. On 22 August 1864, the Swiss government invited the governments of all European countries, as well as the United States, Brazil, and Mexico, to attend an official diplomatic conference. Sixteen countries sent a total of twenty-six delegates to Geneva. On 22 August 1864, the conference adopted the first Geneva Convention "for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded in Armies in the Field". Representatives of 12 states and kingdoms signed the convention:

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

For both of these accomplishments, Henry Dunant became co recipient of the first Nobel Peace Prize in 1901.

On 20 October 1868 the first unsuccessful attempt to expand the 1864 treaty was undertaken. With the 'Additional Articles relating to the Condition of the Wounded in War' an attempt was initiated to clarify some rules of the 1864 convention and to extend them to maritime warfare. The Articles were signed but were only ratified by the Netherlands and the United States of America. The Netherlands later withdrew their ratification. The protection of the victims of maritime warfare would later be realized by the third Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907#Hague Convention of 1899, Hague Convention of 1899 and the tenth Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907#Hague Convention of 1907, Hague Convention of 1907.

In 1906 thirty-five states attended a conference convened by the Swiss government. On 6 July 1906 it resulted in the adoption of the "Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armies in the Field", which improved and supplemented, for the first time, the 1864 convention. It remained in force until 1970 when Costa Rica acceded to the 1949 Geneva Conventions.

The 1929 conference yielded two conventions that were signed on 27 July 1929. One, the "Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armies in the Field", was the third version to replace the original convention of 1864. The other was adopted after experiences in World War I had shown the deficiencies in the protection of prisoners of war under the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907. The "Convention relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War" was not to replace these earlier conventions signed at The Hague, rather it supplemented them.

Inspired by the wave of humanitarian and pacifistic enthusiasm following World War II and the outrage towards the war crimes disclosed by the Nuremberg Trials, a series of conferences were held in 1949 reaffirming, expanding and updating the prior Geneva and Hague Conventions. It yielded four distinct conventions:

*The First Geneva Convention "for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armed Forces in the Field" was the fourth update of the original 1864 convention and replaced the 1929 convention on the same subject matter.

*The Second Geneva Convention "for the Amelioration of the Condition of Wounded, Sick and Shipwrecked Members of Armed Forces at Sea" replaced the Hague Convention (X) of 1907. It was the first Geneva Convention on the protection of the victims of maritime warfare and mimicked the structure and provisions of the First Geneva Convention.

*The Third Geneva Convention "relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War" replaced the 1929 Geneva Convention that dealt with prisoners of war.

*In addition to these three conventions, the conference also added a new elaborate Fourth Geneva Convention "relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War". It was the first Geneva Convention not to deal with combatants, rather it had the protection of civilians as its subject matter. The 1899 and 1907 Hague Conventions had already contained some provisions on the protection of civilians and occupied territory. Article 154 specifically provides that the Fourth Geneva Convention is supplementary to these provisions in the Hague Conventions.

Despite the length of these documents, they were found over time to be incomplete. In fact, the very nature of war, armed conflicts had changed with the beginning of the Cold War era, leading many to believe that the 1949 Geneva Conventions were addressing a largely extinct reality: on the one hand, most armed conflicts had become internal, or civil wars, while on the other, most wars had become increasingly asymmetric warfare, asymmetric. Moreover, modern armed conflicts were inflicting an increasingly higher toll on civilians, which brought the need to provide civilian persons and objects with tangible protections in time of combat, thus bringing a much needed update to the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907. In light of these developments, two Protocols were adopted in 1977 that extended the terms of the 1949 Conventions with additional protections. In 2005, a third brief Protocol was added establishing an additional protective sign for medical services, the Emblems of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement#Red Crystal, Red Crystal, as an alternative to the ubiquitous Emblems of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement, Red Cross and Red Crescent emblems, for those countries that find them objectionable.

Commentaries

''The Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949. Commentary'' (''The Commentaries'') is a series of four volumes of books published between 1952 and 1958 and containing commentaries to each of the four Geneva Conventions. The series was edited by Jean Pictet who was the vice-president of the International Committee of the Red Cross. The ''Commentaries'' are often relied upon to provide authoritative interpretation of the articles.Contents

Conventions

In international law and diplomacy the term ''convention'' refers to ''an international agreement,'' or treaty. * The First Geneva Convention "for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armed Forces in the Field" (first adopted in 1864, revised in 1906, Geneva Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armies in the Field (1929), 1929 and finally 1949); * The Second Geneva Convention "for the Amelioration of the Condition of Wounded, Sick and Shipwrecked Members of Armed Forces at Sea" (first adopted in 1949, successor of the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907#Hague Convention of 1907, Hague Convention (X) 1907); * The Third Geneva Convention "relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War" (first adopted in Geneva Convention on Prisoners of War (1929), 1929, last revision in 1949); * The Fourth Geneva Convention "relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War" (first adopted in 1949, based on parts of the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907#Hague Convention of 1899, Hague Convention (II) of 1899 and Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907#Hague Convention of 1907, Hague Convention (IV) 1907). With two Geneva Conventions revised and adopted, and the second and fourth added, in 1949 the whole set is referred to as the "Geneva Conventions of 1949" or simply the "Geneva Conventions". Usually only the Geneva Conventions of 1949 are referred to as First, Second, Third or Fourth Geneva Convention. The treaties of 1949 were ratified, in whole or with Reservation (law), reservations, List of parties to the Geneva Conventions, by 196 countries.Protocols

The 1949 conventions have been modified with three amendment Protocol (diplomacy), protocols: * Protocol I (1977) relating to the Protection of Victims of International Armed Conflicts * Protocol II (1977) relating to the Protection of Victims of Non-International Armed Conflicts * Protocol III (2005) relating to the Adoption of an Additional Distinctive EmblemApplication

The Geneva Conventions apply at times of war and armed conflict to governments who have ratified its terms. The details of applicability are spelled out in Common Articles 2 and 3.Common Article 2 relating to international armed conflicts

This article states that the Geneva Conventions apply to all the cases of ''international'' conflict, where at least one of the warring nations have ratified the Conventions. Primarily: * The Conventions apply to all cases of Declaration of war, declared war between signatory nations. This is the original sense of applicability, which predates the 1949 version. * The Conventions apply to all cases of armed conflict between two or more signatory nations. This language was added in 1949 to accommodate situations that have all the characteristics of war without the existence of a formal declaration of war, such as a police action. * The Conventions apply to a signatory nation even if the opposing nation is not a signatory, but only if the opposing nation "accepts and applies the provisions" of the Conventions. Article 1 of Protocol I further clarifies that armed conflict against colonial domination and foreign occupation also qualifies as an ''international'' conflict. When the criteria of international conflict have been met, the full protections of the Conventions are considered to apply.Common Article 3 relating to non-international armed conflict

This article states that the certain minimum rules of war apply to armed conflicts "where at least one Party is not a State". The interpretation of the term ''armed conflict'' and therefore the applicability of this article is a matter of debate. For example, it would apply to conflicts between the Government and rebel forces, or between two rebel forces, or to other conflicts that have all the characteristics of war, whether carried out within the confines of one country or not. There are two criteria to distinguish non-international armed conflicts from lower forms of violence. The level of violence has to be of certain intensity, for example when the state cannot contain the situation with regular police forces. Also, involved non-state groups need to have a certain level of organization, like a military command structure. The other Geneva Conventions are not applicable in this situation but only the provisions contained within Article 3, and additionally within the language of Protocol II. The rationale for the limitation is to avoid conflict with the rights of Sovereign States that were not part of the treaties. When the provisions of this article apply, it states that:Enforcement

Protecting powers

The term ''protecting power'' has a specific meaning under these Conventions. A protecting power is a state that is not taking part in the armed conflict, but that has agreed to look after the interests of a state that is a party to the conflict. The protecting power is a mediator enabling the flow of communication between the parties to the conflict. The protecting power also monitors implementation of these Conventions, such as by visiting the zone of conflict and prisoners of war. The protecting power must act as an advocate for prisoners, the wounded, and civilians.Grave breaches

International Committee of the Red Cross. Nations who are party to these treaties must enact and enforce legislation penalizing any of these crimes. Nations are also obligated to search for persons alleged to commit these crimes, or persons having Command responsibility, ordered them to be committed, and to bring them to trial regardless of their nationality and regardless of the place where the crimes took place. The principle of universal jurisdiction also applies to the enforcement of grave breaches when the UN Security Council, United Nations Security Council asserts its authority and jurisdiction from the UN Charter to apply universal jurisdiction. The UNSC did this when they established the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda and the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia to investigate and/or prosecute alleged violations.

Right to a fair trial when no crime is alleged

Soldiers, as prisoners of war, will not receive a trial unless the allegation of a war crime has been made. According to article 43 of the 1949 Conventions, soldiers are employed for the purpose of serving in war; engaging in armed conflict is legitimate, and does not constitute a grave breach. Should a soldier be arrested by belligerent forces, they are to be considered "lawful combatants" and afforded the protectorate status of a prisoner of war (POW) until the cessation of the conflict. Human rights law applies to any incarcerated individual, including the right to a fair trial. Charges may only be brought against an enemy POW after a fair trial, but the initial crime being accused must be an explicit violation of the accords, more severe than simply fighting against the captor in battle. No trial will otherwise be afforded to a captured soldier, as deemed by human rights law. This element of the convention has been confused during past incidents of detainment of US soldiers by North Vietnam, where the regime attempted to try all imprisoned soldiers in court for committing grave breaches, on the incorrect assumption that their sole existence as enemies of the state violated international law.Legacy

Although warfare has changed dramatically since the Geneva Conventions of 1949, they are still considered the cornerstone of contemporary international humanitarian law. They protect combatants who find themselves ''hors de combat,'' and they protect civilians caught up in the zone of war. These treaties came into play for all recent international armed conflicts, including the War in Afghanistan (2001–2021), War in Afghanistan, the 2003 invasion of Iraq, Insurgency in the North Caucasus, the invasion of Chechnya (1994–2017), and the Russo-Georgian War. The Geneva Conventions also protect those affected by non-international armed conflicts such as the Syrian civil war. The lines between combatants and civilians have blurred when the actors are not exclusively High Contracting Parties (HCP). Since the fall of the Soviet Union, an HCP often is faced with a non-state actor, as argued by General Wesley Clark in 2007. Examples of such conflict include the Sri Lankan Civil War, the Second Sudanese Civil War, Sudanese Civil War, and the Colombian Armed Conflict, as well as most military engagements of the US since 2000. Some scholars hold that Common Article 3 deals with these situations, supplemented by Protocol II (1977). These set out minimum legal standards that must be followed for internal conflicts. International tribunals, particularly the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY), have clarified international law in this area. In the 1999 ''Prosecutor v. Dusko Tadic'' judgement, the ICTY ruled that grave breaches apply not only to international conflicts, but also to internal armed conflict. Further, those provisions are considered customary international law. Controversy has arisen over the US designation of irregular opponents as "unlawful enemy combatants" (see also unlawful combatant), especially in the SCOTUS judgments over the Guantanamo Bay detention camp brig facility ''Hamdi v. Rumsfeld'', ''Hamdan v. Rumsfeld'' and ''Rasul v. Bush'', and later ''Boumediene v. Bush''. President George W. Bush, aided by Attorneys-General John Ashcroft and Alberto Gonzales and General Keith B. Alexander, claimed the power, as Commander in Chief of the Armed Forces, to determine that any person, including an American citizen, who is suspected of being a member, agent, or associate of Al Qaeda, the Taliban, or possibly any other terrorist organization, is an "enemy combatant" who can be detained in U.S. military custody until hostilities end, pursuant to the international law of war.presidency.ucsb.edu: "Press Briefing by White House Counsel Judge Alberto Gonzales, DoD General Counsel William Haynes, DoD Deputy General Counsel Daniel Dell'Orto and Army Deputy Chief of Staff for Intelligence General Keith Alexander June 22, 2004", consulted July 2014 The application of the Geneva Conventions in the Russo-Ukrainian War (2014–present) has been troublesome because some of the personnel who engaged in combat against the Ukrainians were not identified by insignia, although they did wear military-style fatigues. The types of comportment qualified as acts of perfidy under doctrine are listed in Articles 37 through 39 of the Geneva Convention; the prohibition of fake insignia is listed at Article 39.2, but the law is silent on the complete absence of insignia. The status of POWs captured in this circumstance remains a question. Educational institutions and organizations including Harvard University, the International Committee of the Red Cross, and the Rohr Jewish Learning Institute use the Geneva Convention as a primary text investigating torture and warfare.

New challenges

Artificial intelligence and autonomous weapon systems, such as military robots and cyber-weapons, are creating challenges in the creation, interpretation and application of the laws of armed conflict. The complexity of these new challenges, as well as the speed in which they are developed, complicates the application of the Conventions, which have not been updated in a long time. Adding to this challenge is the very slow speed of the procedure of developing new treaties to deal with new forms of warfare, and determining agreed-upon interpretations to existing ones, meaning that by the time a decision can be made, armed conflict may have already evolved in a way that makes the changes obsolete.See also

* Attacks on humanitarian workers * Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons * Customary international humanitarian law * Declaration on the Protection of Women and Children in Emergency and Armed Conflict * Geneva Conference (disambiguation) * Geneva Academy of International Humanitarian Law and Human Rights * German Prisoners of War in the United States * Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907 – traditional rules on fighting wars * :Human rights * Human shield * International Committee of the Red Cross * International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies * International humanitarian law * Laws of war * Nuremberg Principles * Reprisals * Rule of Law in Armed Conflicts Project * Saint Petersburg Declaration of 1868 * Targeted killingPeople

* Ian FishbackNotes

Further reading

* Matthew Evangelista and Nina Tannenwald (eds.). 2017.Do the Geneva Conventions Matter?

' Oxford University Press. * Giovanni Mantilla, "doi:10.1093/ejil/chx027, Conforming Instrumentalists: Why the USA and the United Kingdom Joined the 1949 Geneva Conventions," European Journal of International Law, Volume 28, Issue 2, May 2017, Pages 483–511. * Helen Kinsella,

The image before the weapon : a critical history of the distinction between combatant and civilian

Cornell University Press. * Boyd van Dijk (2022).

Preparing for War: The Making of the Geneva Conventions

'. Oxford University Press.

References

External links

*Texts and commentaries of 1949 Conventions & Additional Protocols

The Geneva Conventions: the core of international humanitarian law

ICRC

€”video * Commentaries: *

GCI: Commentary

*

GCII: Commentary

*

GCIII: Commentary

*

GCIV: Commentary

{{Authority control Geneva Conventions,