General will on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In

In

In

In political philosophy

Political philosophy or political theory is the philosophical study of government, addressing questions about the nature, scope, and legitimacy of public agents and institutions and the relationships between them. Its topics include politics, ...

, the general will (french: volonté générale) is the will

Will may refer to:

Common meanings

* Will and testament, instructions for the disposition of one's property after death

* Will (philosophy), or willpower

* Will (sociology)

* Will, volition (psychology)

* Will, a modal verb - see Shall and wi ...

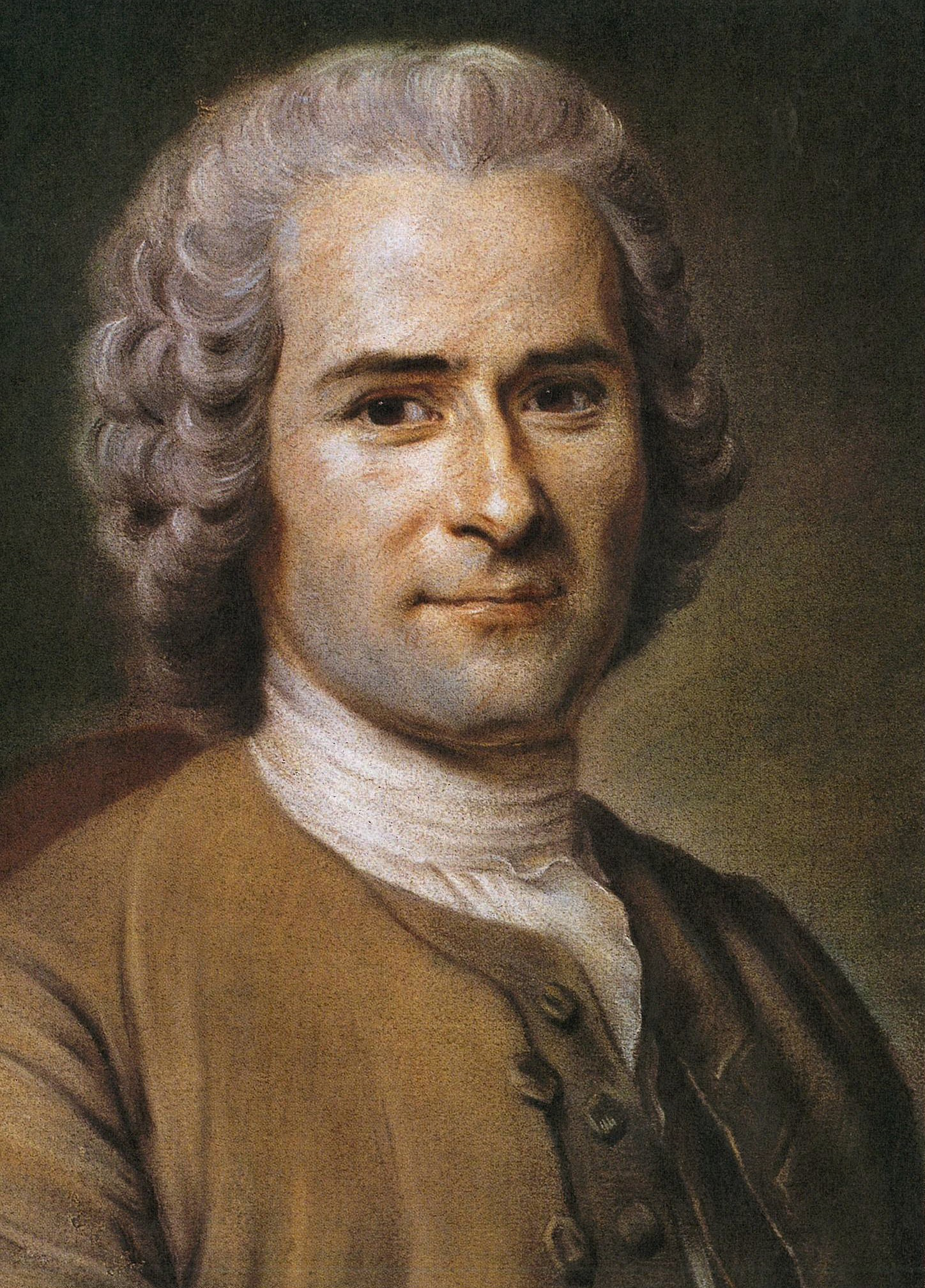

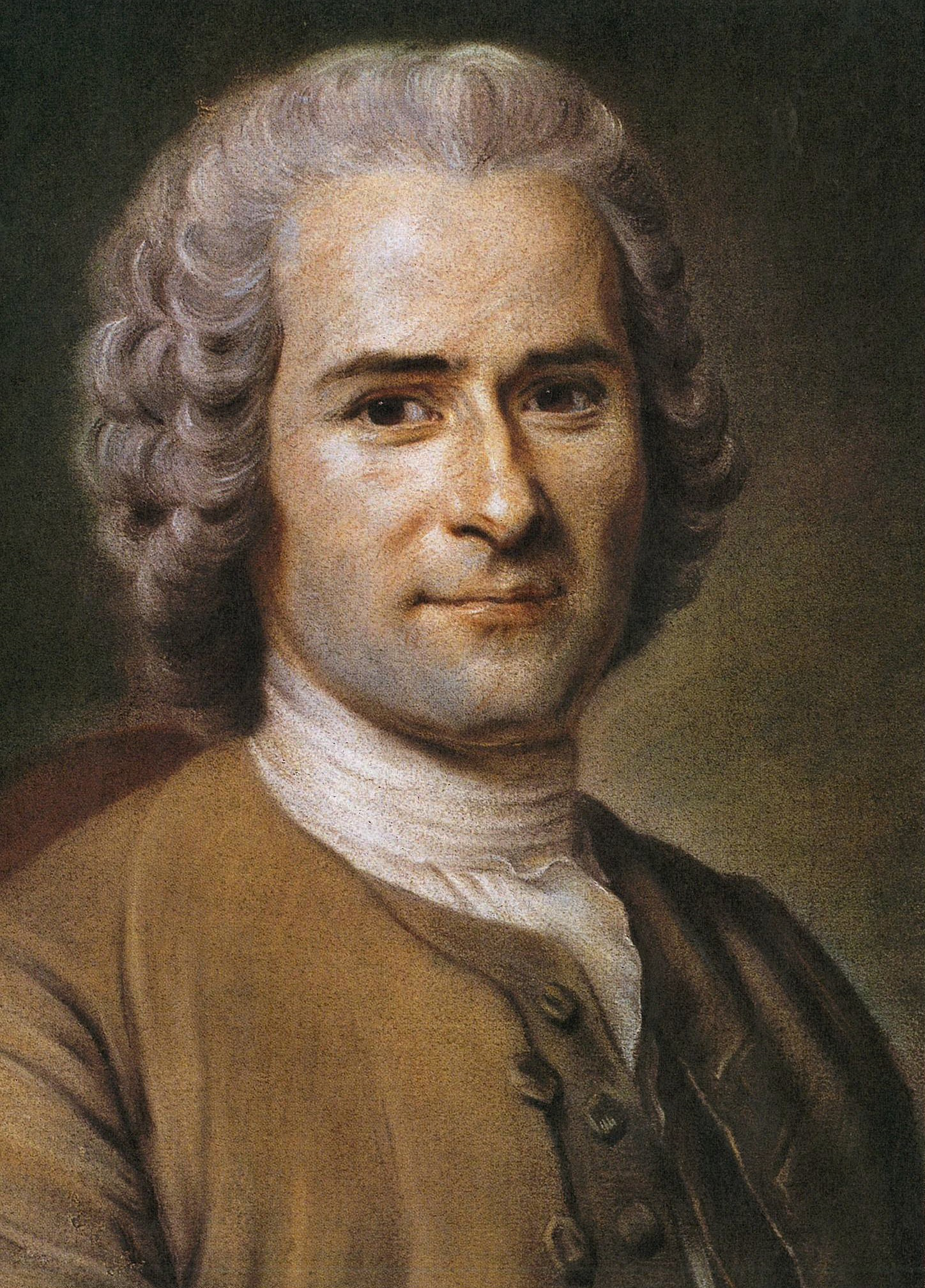

of the people as a whole. The term was made famous by 18th-century Genevan philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (, ; 28 June 1712 – 2 July 1778) was a Genevan philosopher, writer, and composer. His political philosophy influenced the progress of the Age of Enlightenment throughout Europe, as well as aspects of the French Revolu ...

.

Basic ideas

The phrase "general will", as Rousseau used it, occurs in Article Six of theDeclaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen

The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (french: Déclaration des droits de l'homme et du citoyen de 1789, links=no), set by France's National Constituent Assembly in 1789, is a human civil rights document from the French Revol ...

(French: ''Déclaration des droits de l'Homme et du citoyen''), composed in 1789 during the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are conside ...

:The law is the expression of the general will. All citizens have the right to contribute personally, or through their representatives, to its formation. It must be the same for all, whether it protects or punishes. All citizens, being equal in its eyes, are equally admissible to all public dignities, positions, and employments, according to their capacities, and without any other distinction than that of their virtues and their talents.James Swenson writes:

To my knowledge, the only time Rousseau actually uses "expression of the general will" is in a passage of the ''Discours sur l'économie politique'', whose content renders it little susceptible of celebrity. ..But it is indeed a faithful summary of his doctrine, faithful enough that commentators frequently adopt it without any hesitation. Among Rousseau's definitions of law, the textually closest variant can be found in a passage of the ''Lettres écrites de la montagne'' summarizing the argument of ''Du contrat social'', in which law is defined as "a public and solemn declaration of the general will on an object of common interest."As used by Rousseau, the "general will" is considered by some identical to the

rule of law

The rule of law is the political philosophy that all citizens and institutions within a country, state, or community are accountable to the same laws, including lawmakers and leaders. The rule of law is defined in the ''Encyclopedia Britannic ...

, and to Spinoza's ''mens una''.

The notion of the general will is wholly central to Rousseau's theory ofpolitical legitimacy In political science, legitimacy is the right and acceptance of an authority, usually a governing law or a regime. Whereas ''authority'' denotes a specific position in an established government, the term ''legitimacy'' denotes a system of gove .... ..It is, however, an unfortunately obscure and controversial notion. Some commentators see it as no more than the dictatorship of the proletariat or the tyranny of the urban poor (such as may perhaps be seen in the French Revolution). Such was not Rousseau's meaning. This is clear from the ''Discourse on Political Economy'', where Rousseau emphasizes that the general will exists to protect individuals against the mass, not to require them to be sacrificed to it. He is, of course, sharply aware that men have selfish and sectional interests which will lead them to try to oppress others. It is for this reason that loyalty to the good of all alike must be a supreme (although not exclusive) commitment by everyone, not only if a truly general will is to be heeded but also if it is to be formulated successfully in the first place".

Criticisms

Early critics of Rousseau includedBenjamin Constant

Henri-Benjamin Constant de Rebecque (; 25 October 1767 – 8 December 1830), or simply Benjamin Constant, was a Franco-Swiss political thinker, activist and writer on political theory and religion.

A committed republican from 1795, he backed t ...

and Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (; ; 27 August 1770 – 14 November 1831) was a German philosopher. He is one of the most important figures in German idealism and one of the founding figures of modern Western philosophy. His influence extends ...

. Hegel argued that, because it lacked any grounding in an objective ideal of reason, Rousseau's account of the general will inevitably led to the Reign of Terror

The Reign of Terror (french: link=no, la Terreur) was a period of the French Revolution when, following the creation of the First French Republic, First Republic, a series of massacres and numerous public Capital punishment, executions took pl ...

. Constant also blamed Rousseau for the excesses of the French Revolution and rejected the total subordination of the citizen-subjects to the determinations of the general will.

In 1952 Jacob Talmon characterized Rousseau's "general will" as leading to a totalitarian democracy

Totalitarian democracy or anarcho-monarchism is a term popularized by Israeli historian Jacob Leib Talmon to refer to a system of government in which lawfully elected representatives maintain the integrity of a nation state whose citizens, whil ...

, because, Talmon argued, the state subjected its citizens to the supposedly infallible will of the majority

A majority, also called a simple majority or absolute majority to distinguish it from related terms, is more than half of the total.Dictionary definitions of ''majority'' aMerriam-WebsterKarl Popper

Sir Karl Raimund Popper (28 July 1902 – 17 September 1994) was an Austrian-British philosopher, academic and social commentator. One of the 20th century's most influential philosophers of science, Popper is known for his rejection of the ...

, also interpreted Rousseau in this way, while Bertrand Russell

Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell, (18 May 1872 – 2 February 1970) was a British mathematician, philosopher, logician, and public intellectual. He had a considerable influence on mathematics, logic, set theory, linguistics, a ...

warned that "the doctrine of general will ... made possible the mystic identification of a leader with its people, which has no need of confirmation by so mundane an apparatus as the ballot box." Other prominent critics include Isaiah Berlin

Sir Isaiah Berlin (6 June 1909 – 5 November 1997) was a Russian-British social and political theorist, philosopher, and historian of ideas. Although he became increasingly averse to writing for publication, his improvised lectures and talks ...

who argued that Rousseau's association of freedom with obedience to the General Will allowed totalitarian leaders to defend oppression in the name of freedom, and made Rousseau "one of the most sinister and formidable enemies of liberty in the whole history of human thought."

Defense of Rousseau

Some Rousseau scholars, however, such as his biographer and editor Maurice Cranston, and Ralph Leigh, editor of Rousseau's correspondence, do not consider Talmon's 1950s "totalitarian thesis" as sustainable. Supporters of Rousseau argued that Rousseau was not alone among republican political theorists in thinking that small, homogeneous states were best suited to maintaining the freedom of their citizens.Montesquieu

Charles Louis de Secondat, Baron de La Brède et de Montesquieu (; ; 18 January 168910 February 1755), generally referred to as simply Montesquieu, was a French judge, man of letters, historian, and political philosopher.

He is the princi ...

and Machiavelli were also of this opinion. Furthermore, Rousseau envisioned his ''Social Contract

In moral and political philosophy, the social contract is a theory or model that originated during the Age of Enlightenment and usually, although not always, concerns the legitimacy of the authority of the state over the individual.

Social ...

'' as part of a projected larger work on political philosophy, which would have dealt with issues in larger states. Some of his later writings, such as his ''Discourse on Political Economy'', his proposals for a Constitution of Poland, and his essay on maintaining perpetual peace, in which he recommends a federated European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational union, supranational political union, political and economic union of Member state of the European Union, member states that are located primarily in Europe, Europe. The union has a total area of ...

, gave an idea of the future direction of his thought.

His defenders also argued Rousseau is one of the great prose stylists and because of his penchant for the paradoxical effect obtained by stating something strongly and then going on to qualify or negate it, it is easy to misrepresent his ideas by taking them out of context.

Rousseau was also a great synthesizer who was deeply engaged in a dialog with his contemporaries and with the writers of the past, such as the theorists of Natural Law

Natural law ( la, ius naturale, ''lex naturalis'') is a system of law based on a close observation of human nature, and based on values intrinsic to human nature that can be deduced and applied independently of positive law (the express enacte ...

, Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes ( ; 5/15 April 1588 – 4/14 December 1679) was an English philosopher, considered to be one of the founders of modern political philosophy. Hobbes is best known for his 1651 book ''Leviathan'', in which he expounds an influ ...

and Grotius. Like "the body politic", "the general will" was a term of art and was not invented by Rousseau, though admittedly Rousseau did not always go out of his way to explicitly acknowledge his debt to the jurists and theologians who influenced him. Prior to Rousseau, the phrase "general will" referred explicitly to the general (as opposed to the particular) will or ''volition'' (as it is sometimes translated) of the Deity. It occurs in the theological writings of Malebranche, who had picked it up from Pascal

Pascal, Pascal's or PASCAL may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Pascal (given name), including a list of people with the name

* Pascal (surname), including a list of people and fictional characters with the name

** Blaise Pascal, Frenc ...

, and in the writings of Malebranche's pupil, Montesquieu

Charles Louis de Secondat, Baron de La Brède et de Montesquieu (; ; 18 January 168910 February 1755), generally referred to as simply Montesquieu, was a French judge, man of letters, historian, and political philosopher.

He is the princi ...

, who contrasted ''volonté particulière'' and ''volonté générale'' in a secular sense in his most celebrated chapter (Chapter XI) of ''De L'Esprit des Lois'' (1748). In his ''Discourse on Political Economy'', Rousseau explicitly credits Diderot

Denis Diderot (; ; 5 October 171331 July 1784) was a French philosopher, art critic, and writer, best known for serving as co-founder, chief editor, and contributor to the '' Encyclopédie'' along with Jean le Rond d'Alembert. He was a promi ...

's ''Encyclopédie

''Encyclopédie, ou dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers'' (English: ''Encyclopedia, or a Systematic Dictionary of the Sciences, Arts, and Crafts''), better known as ''Encyclopédie'', was a general encyclopedia publis ...

'' article "''Droit Naturel''" as the source of "the luminous concept" of the general will, of which he maintains his own thoughts are simply a development. Montesquieu, Diderot, and Rousseau's innovation was to use the term in a secular rather than theological sense.

Translations of ''volonté générale''

A central aclaration of Rousseau (Contrat Social II, 3) about the difference between ''volonté de tous'' (will of all) and ''volonté géneral'' (general will) is this: The following translation is correct, but with one fundamental error: What has been translated as „decision“ – similarly translated in other English and German editions – is by Rousseau „délibère“ and „délibération“. But a deliberation is not a decision, but a consultation among people in order to reach a mayority decision. Therefore the Roman principle: :''Deliberandum est diu quod statuendum est semel.'' :''What is once resolved is to be long deliberated upon before.'' Voting defines the opinion of the mayority and is a decision – the ''volonté de tous'' or the will of all. The ''volonté générale'' or general will is a consultation to find jointly a mayority decision. Translations which do no take into account this difference – voting without a deliberation and voting after the effort of finding a mayority agreement - lead to confused discussions about the meaning of the general will.Quotations

Diderot on the General Will mphasis addedEVERYTHING you conceive, everything you contemplate, will be good, great, elevated, sublime, if it accords with ''the general and common interest''. There is no quality essential to your species apart from that which you demand from all your fellow men to ensure your happiness and theirs . . . . not ever lose sight of it, or else you will find that your comprehension of the notions of goodness, justice, humanity and virtue grow dim. Say to yourself often, “I am a man, and I have no other truly inalienable natural rights except those of humanity.”

But, you will ask, in what does this general will reside? Where can I consult it? .. he answer is:In the principles of prescribed law of all civilized nations, in the social practices of savage and barbarous peoples; in the tacit agreements obtaining amongst the enemies of mankind; and even in those two emotions — indignation and resentment — which nature has extended as far as animals to compensate for social laws and public retributions. --Denis Diderot, “''Droit Naturel''” article in the ''Rousseau on the General Will mphasis addedEncyclopédie ''Encyclopédie, ou dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers'' (English: ''Encyclopedia, or a Systematic Dictionary of the Sciences, Arts, and Crafts''), better known as ''Encyclopédie'', was a general encyclopedia publis ...''.

AS long as several men assembled together consider themselves as a single body, they have only ''one will'' which is directed towards their common preservation and general well-being. Then, all the animating forces of the state are vigorous and simple, and its principles are clear and luminous; it has no incompatible or conflicting interests; the ''common good'' makes itself so manifestly evident that only common sense is needed to discern it. Peace, unity and equality are the enemies of political sophistication. Upright and simple men are difficult to deceive precisely because of their simplicity; stratagems and clever arguments do not prevail upon them, they are not indeed subtle enough to be dupes. When we see among the happiest people in the world bands of peasants regulating the affairs of state under an oak tree, and always acting wisely, can we help feeling a certain contempt for the refinements of other nations, which employ so much skill and effort to make themselves at once illustrious and wretched?

A state thus governed needs very few laws ../blockquote>However, when the social tie begins to slacken and the state to weaken, when particular interests begin to make themselves felt and sectional societies begin to exert an influence over the greater society, the ''common interest'' then becomes corrupted and meets opposition, voting is no longer unanimous; the general will is no longer the will of all; contradictions and disputes arise, and even the best opinion is not allowed to prevail unchallenged."For this reason the sensible rule for regulating public assemblies is one intended not so much to uphold the general will there, as to ensure that it is always questioned and always responds.''The Social Contract'', Book IV, Chapter 1, Paragraph 6.

See also

*Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (french: Déclaration des droits de l'homme et du citoyen de 1789, links=no), set by France's National Constituent Assembly in 1789, is a human civil rights document from the French Revol ...*Natural law Natural law ( la, ius naturale, ''lex naturalis'') is a system of law based on a close observation of human nature, and based on values intrinsic to human nature that can be deduced and applied independently of positive law (the express enacte ...*Natural and legal rights Some philosophers distinguish two types of rights, natural rights and legal rights. * Natural rights are those that are not dependent on the laws or customs of any particular culture or government, and so are ''universal'', '' fundamental'' an ...*Popular sovereignty Popular sovereignty is the principle that the authority of a state and its government are created and sustained by the consent of its people, who are the source of all political power. Popular sovereignty, being a principle, does not imply any ...*Rule of Law The rule of law is the political philosophy that all citizens and institutions within a country, state, or community are accountable to the same laws, including lawmakers and leaders. The rule of law is defined in the ''Encyclopedia Britannic ...*Social Contract In moral and political philosophy, the social contract is a theory or model that originated during the Age of Enlightenment and usually, although not always, concerns the legitimacy of the authority of the state over the individual. Social ...*Universalizability The concept of universalizability was set out by the 18th-century German philosopher Immanuel Kant Immanuel Kant (, , ; 22 April 1724 – 12 February 1804) was a German philosopher and one of the central Enlightenment thinkers. Born ...

Notes

Further reading

Foisneau, Luc. “Governing a Republic: Rousseau’s General Will and the Problem of Government.” ''Republics of Letters: A Journal for the Study of Knowledge, Politics, and the Arts'' 2, no. 1 (December 15, 2010)

* Riley, Patrick. "A Possible Explanation of Rousseau's General Will", " ''The American Political Science Review''. Vol. 64. No. 1 (March 1970). pp. 86–97 {{Jean-Jacques Rousseau Political philosophy Free will Jean-Jacques Rousseau