Gareth Jones (journalist) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Gareth Richard Vaughan Jones (13 August 1905 – 12 August 1935) was a Welsh journalist who in March 1933 first reported in the

By 1932 Jones had been to the

By 1932 Jones had been to the

Gareth Jones commemorative websiteBukovsky's ''The Living'' websiteUkrainian Canadian Civil Liberties Association website

by his niece, Margaret Siriol Colley. Includes links to newspaper articles written by Jones from around the world. * *

New Release - Tell Them We Are Starving: The 1933 Diaries of Gareth Jones

' (Kashtan Press, 2015)

Gareth Vaughan Jones Collection, National Library of Wales

{{DEFAULTSORT:Jones, Gareth Richard Vaughan 1905 births 1935 deaths Alumni of Aberystwyth University Alumni of Trinity College, Cambridge British expatriates in the Soviet Union British people murdered abroad Deaths by firearm in China Holodomor Journalists killed while covering military conflicts Male murder victims Assassinated British journalists People from Barry, Vale of Glamorgan People murdered in China Recipients of the Order of Merit (Ukraine), 3rd class Unsolved murders in China Welsh journalists

Western world

The Western world, also known as the West, primarily refers to the various nations and states in the regions of Europe, North America, and Oceania.

, without equivocation and under his own name, the existence of the Soviet famine of 1932–1933

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

, including the Holodomor.

Jones had reported anonymously in ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper '' The Sunday Times'' (f ...

'' in 1931 on starvation in Soviet Ukraine and Southern Russia, and, after his third visit to the Soviet Union, issued a press release under his own name in Berlin on 29 March 1933 describing the widespread famine in detail. Reports by Malcolm Muggeridge

Thomas Malcolm Muggeridge (24 March 1903 – 14 November 1990) was an English journalist and satirist. His father, H. T. Muggeridge, was a socialist politician and one of the early Labour Party Members of Parliament (for Romford, in Essex). In ...

, writing in 1933 as an anonymous correspondent, appeared contemporaneously in the '' Manchester Guardian''; his first anonymous article specifying famine in the Soviet Union was published on 25 March 1933.

After being banned from re-entering the Soviet Union, Jones was kidnapped and murdered in 1935 while investigating in Japanese-occupied Mongolia; his murder was likely committed by the Soviet secret police, the NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (russian: Наро́дный комиссариа́т вну́тренних дел, Naródnyy komissariát vnútrennikh del, ), abbreviated NKVD ( ), was the interior ministry of the Soviet Union.

...

. Upon his death, former British prime minister David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor, (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. He was a Liberal Party politician from Wales, known for leading the United Kingdom during ...

said, "He had a passion for finding out what was happening in foreign lands wherever there was trouble, and in pursuit of his investigations he shrank from no risk. … Nothing escaped his observation, and he allowed no obstacle to turn from his course when he thought that there was some fact, which he could obtain. He had the almost unfailing knack of getting at things that mattered."

Early life and education

Born inBarry Barry may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Barry (name), including lists of people with the given name, nickname or surname, as well as fictional characters with the given name

* Dancing Barry, stage name of Barry Richards (born c. 19 ...

, Glamorgan, Jones attended Barry County School, where his father, Major Edgar Jones, was headmaster until around 1933. His mother, Annie Gwen Jones, had worked in Ukraine as a tutor to the children of Arthur Hughes, son of Welsh steel industrialist John Hughes, who founded the town of Hughesovka, modern-day Donetsk

Donetsk ( , ; uk, Донецьк, translit=Donets'k ; russian: Донецк ), formerly known as Aleksandrovka, Yuzivka (or Hughesovka), Stalin and Stalino (see also: cities' alternative names), is an industrial city in eastern Ukraine loca ...

, in Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inv ...

.

Jones graduated from the University College of Wales, Aberystwyth

, mottoeng = A world without knowledge is no world at all

, established = 1872 (as ''The University College of Wales'')

, former_names = University of Wales, Aberystwyth

, type = Public

, endowment = ...

in 1926 with a first-class honours degree in French. He also studied at the University of Strasbourg

The University of Strasbourg (french: Université de Strasbourg, Unistra) is a public research university located in Strasbourg, Alsace, France, with over 52,000 students and 3,300 researchers.

The French university traces its history to the ea ...

"Mr. Gareth Jones: Journalist and Linguist". ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper '' The Sunday Times'' (f ...

''. 17 August 1935. Issue 47145, p. 12. and at Trinity College, Cambridge

Trinity College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. Founded in 1546 by King Henry VIII, Trinity is one of the largest Cambridge colleges, with the largest financial endowment of any college at either Cambridge or Oxford. ...

, from which he graduated in 1929 with another first in French, German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

** Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

, and Russian

Russian(s) refers to anything related to Russia, including:

*Russians (, ''russkiye''), an ethnic group of the East Slavic peoples, primarily living in Russia and neighboring countries

*Rossiyane (), Russian language term for all citizens and peo ...

. After his death, one of his tutors, Hugh Fraser Stewart

Hugh Fraser Stewart (1863–1948) was a British academic, churchman and literary critic.

Life

He was the second son of Ludovic(k) Charles Stewart, an army surgeon and son of Ludovick Stewart of Pityvaich, and Emma Ray or Rae. He was educated at T ...

, wrote in ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper '' The Sunday Times'' (f ...

'' that Jones had been an "extraordinary linguist". At Cambridge he was active in the Cambridge University League of Nations Union The League of Nations Union (LNU) was an organization formed in October 1918 in Great Britain to promote international justice, collective security and a permanent peace between nations based upon the ideals of the League of Nations. The League of N ...

, serving as its assistant secretary.

Career

Teaching; adviser to Lloyd George

After graduating, Jones taught languages briefly at Cambridge, and then in January 1930 was hired as Foreign Affairs Adviser to the British MP and formerprime minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister i ...

David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor, (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. He was a Liberal Party politician from Wales, known for leading the United Kingdom during ...

, thanks to an introduction by Thomas Jones. The post involved preparing notes and briefings Lloyd George could use in debates, articles, and speeches, and also included some travel abroad.

Journalism

In 1929, Jones became a professional freelance reporter, and by 1930 was submitting articles to a variety of newspapers and journals.Germany

In late January and early February 1933, Jones was inGermany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

covering the accession to power of the Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that created and supported t ...

, and was in Leipzig

Leipzig ( , ; Upper Saxon: ) is the most populous city in the German state of Saxony. Leipzig's population of 605,407 inhabitants (1.1 million in the larger urban zone) as of 2021 places the city as Germany's eighth most populous, as ...

on the day Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

was appointed Chancellor. A few days later on 23 February in the , "the fastest and most powerful three-motored aeroplane in Germany", Jones became one of the first foreign journalists to fly with Hitler as he accompanied Hitler and Joseph Goebbels to Frankfurt

Frankfurt, officially Frankfurt am Main (; Hessian: , " Frank ford on the Main"), is the most populous city in the German state of Hesse. Its 791,000 inhabitants as of 2022 make it the fifth-most populous city in Germany. Located on it ...

where he reported for the ''Western Mail'' on the new Chancellor's tumultuous acclamation in that city. He wrote in the Welsh '' Western Mail'' that if the had crashed the history of Europe would have changed.

Soviet Union

By 1932 Jones had been to the

By 1932 Jones had been to the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

twice, for three weeks in the summer of 1930 and for a month in the summer of 1931. He had reported the findings of each trip in his published journalism, including three articles titled "The Two Russias" he published anonymously in ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper '' The Sunday Times'' (f ...

'' in 1930, and three increasingly explicit articles, also anonymous, titled "The Real Russia" in ''The Times'' in October 1931 which reported the starvation of peasants in Soviet Ukraine and Southern Russia.

In March 1933, he travelled to the Soviet Union for a third and final time and on 7 March eluded authorities to slip into the Ukrainian SSR

The Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic ( uk, Украї́нська Радя́нська Соціалісти́чна Респу́бліка, ; russian: Украи́нская Сове́тская Социалисти́ческая Респ ...

, where he kept diaries of the man-made starvation he witnessed. On his return to Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and List of cities in Germany by population, largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's List of cities in the European Union by population within ci ...

on 29 March, he issued his press release, which was published by many newspapers, including ''The Manchester Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'', and changed its name in 1959. Along with its sister papers ''The Observer'' and ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardian'' is part of the Gu ...

'' and the ''New York Evening Post

The ''New York Post'' (''NY Post'') is a conservative daily tabloid newspaper published in New York City. The ''Post'' also operates NYPost.com, the celebrity gossip site PageSix.com, and the entertainment site Decider.com.

It was established i ...

'': I walked along through villages and twelve collective farms. Everywhere was the cry, 'There is no bread. We are dying'. This cry came from every part of Russia, from theThis report was denounced by several Moscow-resident American journalists such as Walter Duranty andVolga The Volga (; russian: Во́лга, a=Ru-Волга.ogg, p=ˈvoɫɡə) is the longest river in Europe. Situated in Russia, it flows through Central Russia to Southern Russia and into the Caspian Sea. The Volga has a length of , and a catchm ...,Siberia Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive region, geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a ...,White Russia White Russia, White Russian, or Russian White may refer to: White Russia *White Ruthenia, a historical reference for a territory in the eastern part of present-day Belarus * An archaic literal translation for Belarus/Byelorussia/Belorussia * Rus ..., theNorth Caucasus The North Caucasus, ( ady, Темыр Къафкъас, Temır Qafqas; kbd, Ишхъэрэ Къаукъаз, İṩxhərə Qauqaz; ce, Къилбаседа Кавказ, Q̇ilbaseda Kavkaz; , os, Цӕгат Кавказ, Cægat Kavkaz, inh, ..., andCentral Asia Central Asia, also known as Middle Asia, is a subregion, region of Asia that stretches from the Caspian Sea in the west to western China and Mongolia in the east, and from Afghanistan and Iran in the south to Russia in the north. It includes t .... I tramped through the black earth region because that was once the richest farmland in Russia and because the correspondents have been forbidden to go there to see for themselves what is happening.

In the train a Communist denied to me that there was a famine. I flung a crust of bread which I had been eating from my own supply into a spittoon. A peasant fellow-passenger fished it out and ravenously ate it. I threw an orange peel into the spittoon and the peasant again grabbed it and devoured it. The Communist subsided. I stayed overnight in a village where there used to be two hundred oxen and where there now are six. The peasants were eating the cattle fodder and had only a month's supply left. They told me that many had already died of hunger. Two soldiers came to arrest a thief. They warned me against travel by night, as there were too many 'starving' desperate men.

'We are waiting for death' was my welcome, but see, we still, have our cattle fodder. Go farther south. There they have nothing. Many houses are empty of people already dead,' they cried.

Eugene Lyons

Eugene Lyons (July 1, 1898 – January 7, 1985) was an American journalist and writer. A fellow traveler of Communism in his younger years, Lyons became highly critical of the Soviet Union after several years there as a correspondent of United P ...

, who had been obscuring the truth in order to please the dictatorial Soviet regime. On 31 March, ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid d ...

'' published a denial of Jones's statement by Duranty under the headline "Russians Hungry, But Not Starving". Duranty called Jones' report "a big scare story". Historian Timothy Snyder

Timothy David Snyder (born August 18, 1969) is an American historian specializing in the modern history of Central and Eastern Europe. He is the Richard C. Levin Professor of History at Yale University and a permanent fellow at the Institute ...

has written that "Duranty's claim that there was 'no actual starvation' but only 'widespread mortality from diseases due to malnutrition' echoed Soviet usages and pushed euphemism into mendacity. This was an Orwellian distinction; and indeed George Orwell himself regarded the Ukrainian famine of 1933 as a central example of a black truth that artists of language had covered with bright colors."

In the article, Kremlin sources denied the existence of a famine; part of ''The New York Times'' headline was: "Russian and Foreign Observers in Country See No Ground for Predications of Disaster."

On 11 April 1933, Jones published a detailed analysis of the famine in the ''Financial News

''Financial News'' is a financial newspaper and news website published in London. It is a weekly newspaper, published by eFinancial News Limited, covering the financial services sector through news, views and extensive people coverage. ''Fin ...

'', pointing out its main causes: forced collectivization of private farms, removal of 6–7 millions of "best workers" (the Kulaks

Kulak (; russian: кула́к, r=kulák, p=kʊˈlak, a=Ru-кулак.ogg; plural: кулаки́, ''kulakí'', 'fist' or 'tight-fisted'), also kurkul () or golchomag (, plural: ), was the term which was used to describe peasants who owned ov ...

) from their land, forced requisitions of grain and farm animals and increased "export of foodstuffs" from USSR.

On 13 May ''The New York Times'' published a strong rebuttal of Duranty from Jones, who stood by his report:

In a personal letter from Soviet Foreign Commissar Maxim Litvinov

Maxim Maximovich Litvinov (; born Meir Henoch Wallach; 17 July 1876 – 31 December 1951) was a Russian revolutionary and prominent Soviet statesman and diplomat.

A strong advocate of diplomatic agreements leading towards disarmament, Litvinov w ...

(whom Jones had interviewed while in Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 millio ...

) to Lloyd George, Jones was informed that he was banned from ever visiting the Soviet Union again.

After his Ukraine articles, the only work Jones could get was in Cardiff on the ''Western Mail'' covering "arts, crafts and coracles", according to his great-nephew Nigel Linsan Colley. But he managed to get an interview with the owner of nearby St Donat's Castle

St Donat's Castle ( cy, Castell Sain Dunwyd), St Donats, Wales, is a medieval castle in the Vale of Glamorgan, about to the west of Cardiff, and about to the west of Llantwit Major. Positioned on cliffs overlooking the Bristol Channel, the si ...

, the American press magnate William Randolph Hearst

William Randolph Hearst Sr. (; April 29, 1863 – August 14, 1951) was an American businessman, newspaper publisher, and politician known for developing the nation's largest newspaper chain and media company, Hearst Communications. His flamboya ...

. Hearst published Jones's account of what had happened in Ukraine – as he did for the almost identical eye-witness testimony of the disillusioned American Communist Fred Beal. – and arranged a lecture and broadcast tour of the USA.

Japan and China

Banned from the Soviet Union, Jones turned his attention to theFar East

The ''Far East'' was a European term to refer to the geographical regions that includes East and Southeast Asia as well as the Russian Far East to a lesser extent. South Asia is sometimes also included for economic and cultural reasons.

The ter ...

and in late 1934 he left Britain on a "Round-the-World Fact-Finding Tour". He spent about six weeks in Japan, interviewing important generals and politicians, and he eventually reached Beijing

}

Beijing ( ; ; ), alternatively romanized as Peking ( ), is the capital of the People's Republic of China. It is the center of power and development of the country. Beijing is the world's most populous national capital city, with over 21 ...

. From here he traveled to Inner Mongolia

Inner Mongolia, officially the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, is an autonomous region of the People's Republic of China. Its border includes most of the length of China's border with the country of Mongolia. Inner Mongolia also accounts for a ...

in newly Japanese-occupied Manchukuo in the company of a German journalist, Herbert Müller. Detained by Japanese forces, the pair were told that there were three routes back to the Chinese town of Kalgan

Zhangjiakou (; ; ) also known as Kalgan and by several other names, is a prefecture-level city in northwestern Hebei province in Northern China, bordering Beijing to the southeast, Inner Mongolia to the north and west, and Shanxi to the southw ...

, only one of which was safe.

Kidnapping and murder

Jones and Müller were subsequently captured by bandits who demanded a ransom of 200 Mauser firearms and 100,000 Chinese dollars (according to ''The Times'', equivalent to about £8,000). Müller was released after two days to arrange for the ransom to be paid. On 1 August, Jones's father received a telegram: "Well treated. Expect release soon." On 5 August, ''The Times'' reported that the kidnappers had moved Jones to an area southeast of Kuyuan and were now asking for 10,000 Chinese dollars (about £800), and two days later that he had again been moved, this time to Jehol. On 8 August the news came that the first group of kidnappers had handed him over to a second group, and the ransom had increased to 100,000 Chinese dollars again. The Chinese and Japanese governments both made an effort to contact the kidnappers. On 17 August 1935, ''The Times'' reported that the Chinese authorities had found Jones's body the previous day with three bullet wounds. The authorities believed that he had been killed on 12 August, the day before his 30th birthday."Mr. Gareth Jones: Murder by Bandits". ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper '' The Sunday Times'' (f ...

''. 17 August 1935. Issue 47145, p. 10. There was a suspicion that his murder had been engineered by the Soviet NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (russian: Наро́дный комиссариа́т вну́тренних дел, Naródnyy komissariát vnútrennikh del, ), abbreviated NKVD ( ), was the interior ministry of the Soviet Union.

...

, as revenge for the embarrassment he had caused the Soviet regime. Lloyd George is reported to have said:

Legacy

Memorial

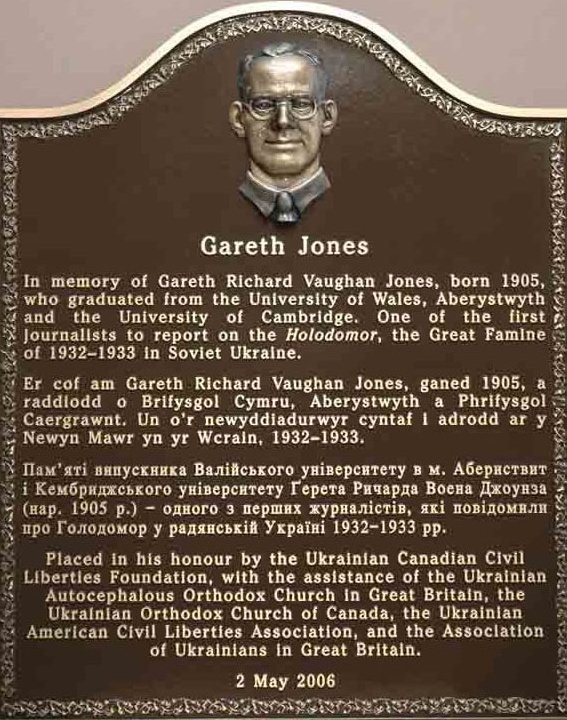

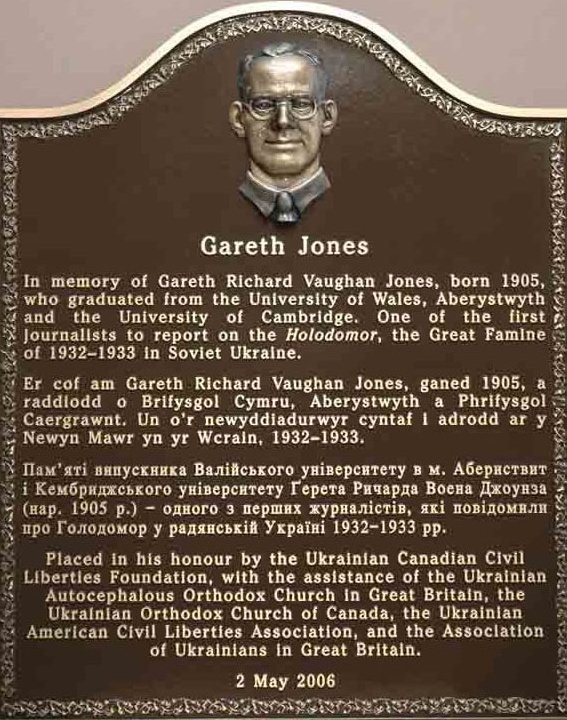

On 2 May 2006, a trilingual (English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ide ...

/ Welsh/Ukrainian

Ukrainian may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to Ukraine

* Something relating to Ukrainians, an East Slavic people from Eastern Europe

* Something relating to demographics of Ukraine in terms of demography and population of Ukraine

* So ...

) plaque was unveiled in Jones' memory in the Old College at Aberystwyth University, in the presence of his niece Margaret Siriol Colley, and the Ukrainian Ambassador to the UK, Ihor Kharchenko

Ihor Kharchenko (born May 15, 1962 in Kyiv, Ukraine) is a Ukrainian diplomat: an Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary of Ukraine.

Education

Ihor Kharchenko graduated from Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv in 1985, master's De ...

, who described him as an "unsung hero of Ukraine". The idea for a plaque and funding were provided by the Ukrainian Canadian Civil Liberties Association, working in conjunction with the Association of Ukrainians in Great Britain. Dr Lubomyr Luciuk, UCCLA's director of research, spoke at the unveiling ceremony.

In November 2008, Jones and fellow Holodomor journalist Malcolm Muggeridge

Thomas Malcolm Muggeridge (24 March 1903 – 14 November 1990) was an English journalist and satirist. His father, H. T. Muggeridge, was a socialist politician and one of the early Labour Party Members of Parliament (for Romford, in Essex). In ...

were posthumously awarded the Ukrainian Order of Merit at a ceremony in Westminster Central Hall

The Methodist Central Hall (also known as Central Hall Westminster) is a multi-purpose venue in the City of Westminster, London, serving primarily as a Methodist church and a conference centre. The building, which is a tourist attraction, also ho ...

, by Dr Kharchenko, on behalf of Ukrainian President

The president of Ukraine ( uk, Президент України, Prezydent Ukrainy) is the head of state of Ukraine. The president represents the nation in international relations, administers the foreign political activity of the state, condu ...

Viktor Yushchenko

Viktor Andriyovych Yushchenko ( uk, Віктор Андрійович Ющенко, ; born 23 February 1954) is a Ukrainian politician who was the third president of Ukraine from 23 January 2005 to 25 February 2010.

As an informal leader of th ...

for their exceptional service to the country and its people.

Diaries

In November 2009, Jones' diaries recording the man-made genocide of the Great Soviet Famine of 1932–33 went on display for the first time in the Wren Library ofTrinity College, Cambridge

Trinity College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. Founded in 1546 by King Henry VIII, Trinity is one of the largest Cambridge colleges, with the largest financial endowment of any college at either Cambridge or Oxford. ...

.

Depictions in film

Serhii Bukovskyi's 2008 Ukrainian film ''The Living

''The Living'' is a 2014 American drama film written and directed by Jack Bryan. It stars Fran Kranz, Jocelin Donahue, Kenny Wormald, Chris Mulkey, and Joelle Carter. Teddy (Kranz) learns he has beaten his wife, Molly (Donahue), in a drunken rag ...

'' is a documentary about the Great Famine of 1932–33 and Jones's attempts to uncover it. ''The Living'' premiered 21 November 2008 at the Kyiv Cinema House. It was screened in February 2009 at the European Film Market, in spring 2009 at the Ukrainian Film Festival in Cologne, and in November 2009 at the Second Annual Cambridge Festival of Ukrainian Film. It received the 2009 Special Jury Prize Silver Apricot in the International Documentary Competition at the Sixth Golden Apricot International Film Festival in July 2009 and the 2009 Grand Prize of Geneva in September 2009.

In 2012, the documentary film ''Hitler, Stalin, and Mr Jones'', directed by George Carey

George Leonard Carey, Baron Carey of Clifton (born 13 November 1935) is a retired Anglican bishop who was the Archbishop of Canterbury from 1991 to 2002, having previously been the Bishop of Bath and Wells.

During his time as archbishop the C ...

, was broadcast on the BBC series '' Storyville''. It has subsequently been screened in select cinemas.

The 2019 feature film '' Mr Jones'', starring James Norton and directed by Agnieszka Holland

Agnieszka Holland (born 28 November 1948) is a Polish film and television director and screenwriter, best known for her political contributions to Polish cinema. She began her career as assistant to directors Krzysztof Zanussi and Andrzej Wajda, ...

, focuses on Jones and his investigation of and reporting on the Ukrainian famine in the face of political and journalistic opposition. In January 2019, it was selected to compete for the Golden Bear

The Golden Bear (german: Goldener Bär) is the highest prize awarded for the best film at the Berlin International Film Festival. The bear is the heraldic animal of Berlin, featured on both the coat of arms and flag of Berlin.

History

The win ...

at the 69th Berlin International Film Festival

The 69th annual Berlin International Film Festival took place from 7 to 17 February 2019. French actress Juliette Binoche served as the Jury President. Lone Scherfig's drama film '' The Kindness of Strangers'' opened the festival. The Golden Bea ...

. The film won Grand Prix Golden Lions at the 44th Gdynia Film Festival

The Gdynia Film Festival (until 2011: Polish Film Festival, Polish: ''Festiwal Polskich Filmów Fabularnych w Gdyni'') is an annual film festival first held in Gdańsk (1974–1986), now held in Gdynia, Poland.

It has taken place every year sinc ...

in September 2019.

See also

*List of unsolved murders

These lists of unsolved murders include notable cases where victims were murdered in unknown circumstances.

* List of unsolved murders (before 1900)

* List of unsolved murders (1900–1979)

* List of unsolved murders (1980–1999)

* List of u ...

* Soviet famine of 1921

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

* Soviet famine of 1946–47

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

Notes

References

Further reading

* Ray Gamache: ''Gareth Jones : eyewitness to the Holodomor'', Cardiff : Welsh Academic Press, 2018,External links

Gareth Jones commemorative website

by his niece, Margaret Siriol Colley. Includes links to newspaper articles written by Jones from around the world. * *

New Release - Tell Them We Are Starving: The 1933 Diaries of Gareth Jones

' (Kashtan Press, 2015)

Gareth Vaughan Jones Collection, National Library of Wales

{{DEFAULTSORT:Jones, Gareth Richard Vaughan 1905 births 1935 deaths Alumni of Aberystwyth University Alumni of Trinity College, Cambridge British expatriates in the Soviet Union British people murdered abroad Deaths by firearm in China Holodomor Journalists killed while covering military conflicts Male murder victims Assassinated British journalists People from Barry, Vale of Glamorgan People murdered in China Recipients of the Order of Merit (Ukraine), 3rd class Unsolved murders in China Welsh journalists