Gaelic language on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Goidelic or Gaelic languages ( ga, teangacha Gaelacha; gd, cànanan Goidhealach; gv, çhengaghyn Gaelgagh) form one of the two groups of

During the historical era, Goidelic was restricted to

During the historical era, Goidelic was restricted to

Were the Scots Irish?

in ''Antiquity'' #75 (2001). Dál Riata grew in size and influence, and Gaelic language and culture was eventually adopted by the neighbouring

Despite the ascent in Ireland of the English and Anglicised ruling classes following the 1607

Despite the ascent in Ireland of the English and Anglicised ruling classes following the 1607

* and are no longer used in counting. Instead the suppletive forms and are normally used for counting but for comparative purposes, the historic forms are listed in the table above

*

*

Comparison of Irish and Scottish Gaelic

{{DEFAULTSORT:Goidelic Languages Articles containing video clips

Insular Celtic languages

Insular Celtic languages are the group of Celtic languages of Brittany, Great Britain, Ireland, and the Isle of Man. All surviving Celtic languages are in the Insular group, including Breton, which is spoken on continental Europe in Brittany, ...

, the other being the Brittonic languages

The Brittonic languages (also Brythonic or British Celtic; cy, ieithoedd Brythonaidd/Prydeinig; kw, yethow brythonek/predennek; br, yezhoù predenek) form one of the two branches of the Insular Celtic language family; the other is Goidelic ...

.

Goidelic languages historically formed a dialect continuum

A dialect continuum or dialect chain is a series of language varieties spoken across some geographical area such that neighboring varieties are mutually intelligible, but the differences accumulate over distance so that widely separated varie ...

stretching from Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

through the Isle of Man

)

, anthem = "O Land of Our Birth"

, image = Isle of Man by Sentinel-2.jpg

, image_map = Europe-Isle_of_Man.svg

, mapsize =

, map_alt = Location of the Isle of Man in Europe

, map_caption = Location of the Isle of Man (green)

in Europe ...

to Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a Anglo-Scottish border, border with England to the southeast ...

. There are three modern Goidelic languages: Irish

Irish may refer to:

Common meanings

* Someone or something of, from, or related to:

** Ireland, an island situated off the north-western coast of continental Europe

***Éire, Irish language name for the isle

** Northern Ireland, a constituent unit ...

('), Scottish Gaelic

Scottish Gaelic ( gd, Gàidhlig ), also known as Scots Gaelic and Gaelic, is a Goidelic language (in the Celtic branch of the Indo-European language family) native to the Gaels of Scotland. As a Goidelic language, Scottish Gaelic, as well ...

('), and Manx ('). Manx died out as a first language

A first language, native tongue, native language, mother tongue or L1 is the first language or dialect that a person has been exposed to from birth or within the critical period. In some countries, the term ''native language'' or ''mother tongu ...

in the 20th century but has since been revived to some degree.

Nomenclature

''Gaelic'', by itself, is sometimes used to refer to Scottish Gaelic, especially in Scotland, and so it is ambiguous.Irish

Irish may refer to:

Common meanings

* Someone or something of, from, or related to:

** Ireland, an island situated off the north-western coast of continental Europe

***Éire, Irish language name for the isle

** Northern Ireland, a constituent unit ...

and Manx are sometimes referred to as Irish Gaelic and Manx Gaelic (as they are Goidelic or Gaelic languages), but the use of the word "Gaelic" is unnecessary because the terms Irish and Manx, when used to denote languages, always refer to those languages. This is in contrast to Scottish Gaelic

Scottish Gaelic ( gd, Gàidhlig ), also known as Scots Gaelic and Gaelic, is a Goidelic language (in the Celtic branch of the Indo-European language family) native to the Gaels of Scotland. As a Goidelic language, Scottish Gaelic, as well ...

, for which "Gaelic" distinguishes the language from the Germanic language

The Germanic languages are a branch of the Indo-European language family spoken natively by a population of about 515 million people mainly in Europe, North America, Oceania and Southern Africa. The most widely spoken Germanic language, E ...

known as Scots.

The endonyms (, and in Irish, in Manx and in Scottish Gaelic) are derived from Old Irish

Old Irish, also called Old Gaelic ( sga, Goídelc, Ogham script: ᚌᚑᚔᚇᚓᚂᚉ; ga, Sean-Ghaeilge; gd, Seann-Ghàidhlig; gv, Shenn Yernish or ), is the oldest form of the Goidelic/Gaelic language for which there are extensive writt ...

, which in turn is derived from Old Welsh meaning "pirate, raider". The medieval mythology of the places its origin in an eponymous ancestor of the Gaels

The Gaels ( ; ga, Na Gaeil ; gd, Na Gàidheil ; gv, Ny Gaeil ) are an ethnolinguistic group native to Ireland, Scotland and the Isle of Man in the British Isles. They are associated with the Gaelic languages: a branch of the Celtic langu ...

and the inventor of the language, .

Classification

The family tree of the Goidelic languages, within the Insular Celtic branch of the Celtic language family, is as follows: *Primitive Irish

Primitive Irish or Archaic Irish ( ga, Gaeilge Ársa), also called Proto-Goidelic, is the oldest known form of the Goidelic languages. It is known only from fragments, mostly personal names, inscribed on stone in the ogham alphabet in Ireland ...

** Old Irish

Old Irish, also called Old Gaelic ( sga, Goídelc, Ogham script: ᚌᚑᚔᚇᚓᚂᚉ; ga, Sean-Ghaeilge; gd, Seann-Ghàidhlig; gv, Shenn Yernish or ), is the oldest form of the Goidelic/Gaelic language for which there are extensive writt ...

*** Middle Irish

Middle Irish, sometimes called Middle Gaelic ( ga, An Mheán-Ghaeilge, gd, Meadhan-Ghàidhlig), is the Goidelic language which was spoken in Ireland, most of Scotland and the Isle of Man from AD; it is therefore a contemporary of late Old Engl ...

**** Modern Irish

Irish ( Standard Irish: ), also known as Gaelic, is a Goidelic language of the Insular Celtic branch of the Celtic language family, which is a part of the Indo-European language family. Irish is indigenous to the island of Ireland and was t ...

**** Scottish Gaelic

Scottish Gaelic ( gd, Gàidhlig ), also known as Scots Gaelic and Gaelic, is a Goidelic language (in the Celtic branch of the Indo-European language family) native to the Gaels of Scotland. As a Goidelic language, Scottish Gaelic, as well ...

**** Manx

Origin, history and range

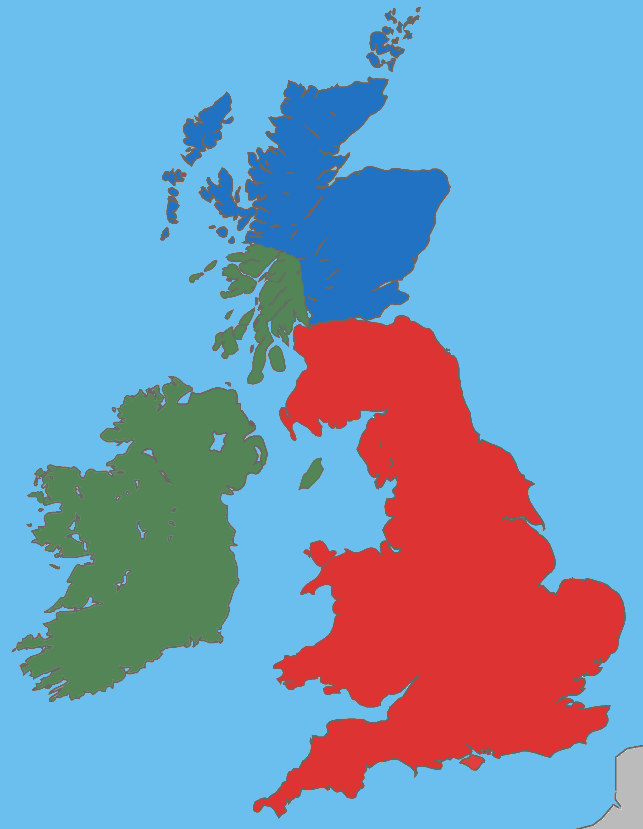

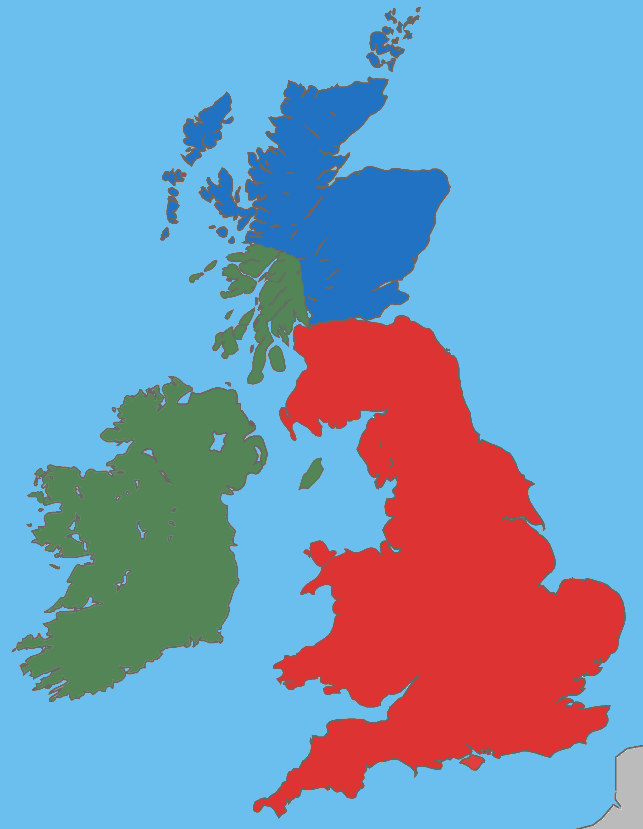

During the historical era, Goidelic was restricted to

During the historical era, Goidelic was restricted to Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

and, possibly, the west coast of Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a Anglo-Scottish border, border with England to the southeast ...

. Medieval Gaelic literature tells us that the kingdom of Dál Riata

Dál Riata or Dál Riada (also Dalriada) () was a Gaelic kingdom that encompassed the western seaboard of Scotland and north-eastern Ireland, on each side of the North Channel. At its height in the 6th and 7th centuries, it covered what is n ...

emerged in western Scotland during the 6th century. The mainstream view is that Dál Riata was founded by Irish migrants, but this is not universally accepted. Archaeologist Ewan Campbell

Ewan Campbell is a Scottish archaeologist and author, who serves as the senior lecturer of archaeology at the University of Glasgow. An author of a number of books, he is perhaps best known as the originator of the historical revisionist thesis t ...

says there is no archaeological evidence for a migration or invasion, and suggests strong sea links helped maintain a pre-existing Gaelic culture on both sides of the North Channel.Campbell, Ewan.Were the Scots Irish?

in ''Antiquity'' #75 (2001). Dál Riata grew in size and influence, and Gaelic language and culture was eventually adopted by the neighbouring

Picts

The Picts were a group of peoples who lived in what is now northern and eastern Scotland (north of the Firth of Forth) during Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages. Where they lived and what their culture was like can be inferred from e ...

(a group of peoples who may have spoken a Brittonic language) who lived throughout Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a Anglo-Scottish border, border with England to the southeast ...

. Manx, the language of the Isle of Man

)

, anthem = "O Land of Our Birth"

, image = Isle of Man by Sentinel-2.jpg

, image_map = Europe-Isle_of_Man.svg

, mapsize =

, map_alt = Location of the Isle of Man in Europe

, map_caption = Location of the Isle of Man (green)

in Europe ...

, is closely akin to the Gaelic spoken in the Hebrides

The Hebrides (; gd, Innse Gall, ; non, Suðreyjar, "southern isles") are an archipelago off the west coast of the Scottish mainland. The islands fall into two main groups, based on their proximity to the mainland: the Inner and Outer Hebr ...

and the Irish spoken in northeast and eastern Ireland and the now-extinct Galwegian Gaelic

Galwegian Gaelic (also known as Gallovidian Gaelic, Gallowegian Gaelic, or Galloway Gaelic) is an extinct dialect of Scottish Gaelic formerly spoken in southwest Scotland. It was spoken by the people of Galloway and Carrick until the ear ...

of Galloway

Galloway ( ; sco, Gallowa; la, Gallovidia) is a region in southwestern Scotland comprising the historic counties of Wigtownshire and Kirkcudbrightshire. It is administered as part of the council area of Dumfries and Galloway.

A native or ...

(in southwest Scotland), with some influence from Old Norse through the Viking

Vikings ; non, víkingr is the modern name given to seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded and se ...

invasions and from the previous British inhabitants.

The oldest written Goidelic language is Primitive Irish

Primitive Irish or Archaic Irish ( ga, Gaeilge Ársa), also called Proto-Goidelic, is the oldest known form of the Goidelic languages. It is known only from fragments, mostly personal names, inscribed on stone in the ogham alphabet in Ireland ...

, which is attested in Ogham

Ogham ( Modern Irish: ; mga, ogum, ogom, later mga, ogam, label=none ) is an Early Medieval alphabet used primarily to write the early Irish language (in the "orthodox" inscriptions, 4th to 6th centuries AD), and later the Old Irish langu ...

inscriptions from about the 4th century. The forms of this speech are very close, and often identical, to the forms of Gaulish

Gaulish was an ancient Celtic language spoken in parts of Continental Europe before and during the period of the Roman Empire. In the narrow sense, Gaulish was the language of the Celts of Gaul (now France, Luxembourg, Belgium, most of Switze ...

recorded before and during the time of the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post- Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Mediter ...

. The next stage, Old Irish

Old Irish, also called Old Gaelic ( sga, Goídelc, Ogham script: ᚌᚑᚔᚇᚓᚂᚉ; ga, Sean-Ghaeilge; gd, Seann-Ghàidhlig; gv, Shenn Yernish or ), is the oldest form of the Goidelic/Gaelic language for which there are extensive writt ...

, is found in glosses

A gloss is a brief notation, especially a marginal one or an interlinear one, of the meaning of a word or wording in a text. It may be in the language of the text or in the reader's language if that is different.

A collection of glosses is a ''g ...

(i.e. annotations) to Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

manuscript

A manuscript (abbreviated MS for singular and MSS for plural) was, traditionally, any document written by hand – or, once practical typewriters became available, typewritten – as opposed to mechanically printed or reproduced in ...

s—mainly religious and grammatical—from the 6th to the 10th century, as well as in archaic texts copied or recorded in Middle Irish

Middle Irish, sometimes called Middle Gaelic ( ga, An Mheán-Ghaeilge, gd, Meadhan-Ghàidhlig), is the Goidelic language which was spoken in Ireland, most of Scotland and the Isle of Man from AD; it is therefore a contemporary of late Old Engl ...

texts. Middle Irish, the immediate predecessor of the modern Goidelic languages, is the term for the language as recorded from the 10th to the 12th century: a great deal of literature survives in it, including the early Irish law texts.

Classical Gaelic

Classical Gaelic or Classical Irish () was a shared literary form of Gaelic that was in use by poets in Scotland and Ireland from the 13th century to the 18th century.

Although the first written signs of Scottish Gaelic having diverged from Ir ...

, otherwise known as Early Modern Irish

Early Modern Irish ( ga, Gaeilge Chlasaiceach, , Classical Irish) represented a transition between Middle Irish and Modern Irish. Its literary form, Classical Gaelic, was used in Ireland and Scotland from the 13th to the 18th century.

External ...

, covers the period from the 13th to the 18th century, during which time it was used as a literary standard in Ireland and Scotland. This is often called Classical Irish, while '' Ethnologue'' gives the name " Hiberno-Scottish Gaelic" to this standardised written language. As long as this written language was the norm, Ireland was considered the Gaelic homeland to the Scottish literati.

Later orthographic divergence has resulted in standardised pluricentristic orthographies. Manx orthography, which was introduced in the 16th and 17th centuries, was based loosely on English and Welsh orthography, and so never formed part of this literary standard.

Proto-Goidelic

Proto-Goidelic, or proto-Gaelic, is the proposedproto-language

In the tree model of historical linguistics, a proto-language is a postulated ancestral language from which a number of attested languages are believed to have descended by evolution, forming a language family. Proto-languages are usually unattes ...

for all branches of Goidelic. It is proposed as the predecessor of Goidelic, which then began to separate into different dialects before splitting during the Middle Irish period into the separate languages of Irish

Irish may refer to:

Common meanings

* Someone or something of, from, or related to:

** Ireland, an island situated off the north-western coast of continental Europe

***Éire, Irish language name for the isle

** Northern Ireland, a constituent unit ...

, Manx, and Scottish Gaelic

Scottish Gaelic ( gd, Gàidhlig ), also known as Scots Gaelic and Gaelic, is a Goidelic language (in the Celtic branch of the Indo-European language family) native to the Gaels of Scotland. As a Goidelic language, Scottish Gaelic, as well ...

.

Irish

Irish is one of theRepublic of Ireland

Ireland ( ga, Éire ), also known as the Republic of Ireland (), is a country in north-western Europe consisting of 26 of the 32 Counties of Ireland, counties of the island of Ireland. The capital and largest city is Dublin, on the eastern ...

's two official languages along with English. Historically the predominant language of the island, it is now mostly spoken in parts of the south, west, and northwest. The legally defined Irish-speaking areas are called the ; all government institutions of the Republic, in particular the parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: representing the electorate, making laws, and overseeing the government via hearings and inquiries. Th ...

('), its upper house

An upper house is one of two chambers of a bicameral legislature, the other chamber being the lower house.''Bicameralism'' (1997) by George Tsebelis The house formally designated as the upper house is usually smaller and often has more restric ...

(') and lower house ('), and the prime minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister i ...

(') have official names in this language, and some are only officially referred to by their Irish names even in English. At present, the are primarily found in Counties Cork, Donegal, Mayo Mayo often refers to:

* Mayonnaise, often shortened to "mayo"

* Mayo Clinic, a medical center in Rochester, Minnesota, United States

Mayo may also refer to:

Places

Antarctica

* Mayo Peak, Marie Byrd Land

Australia

* Division of Mayo, an Aust ...

, Galway

Galway ( ; ga, Gaillimh, ) is a city in the West of Ireland, in the province of Connacht, which is the county town of County Galway. It lies on the River Corrib between Lough Corrib and Galway Bay, and is the sixth most populous city on ...

, Kerry

Kerry or Kerri may refer to:

* Kerry (name), a given name and surname of Gaelic origin (including a list of people with the name)

Places

* Kerry, Queensland, Australia

* County Kerry, Ireland

** Kerry Airport, an international airport in Count ...

, and, to a lesser extent, in Waterford

"Waterford remains the untaken city"

, mapsize = 220px

, pushpin_map = Ireland#Europe

, pushpin_map_caption = Location within Ireland##Location within Europe

, pushpin_relief = 1

, coordinates ...

and Meath. In the Republic of Ireland 1,774,437 (41.4% of the population aged three years and over) regard themselves as able to speak Irish to some degree. Of these, 77,185 (1.8%) speak Irish on a daily basis outside school. Irish is also undergoing a revival in Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ga, Tuaisceart Éireann ; sco, label= Ulster-Scots, Norlin Airlann) is a part of the United Kingdom, situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, that is variously described as a country, province or region. Nort ...

and has been accorded some legal status there under the 1998 Good Friday Agreement

The Good Friday Agreement (GFA), or Belfast Agreement ( ga, Comhaontú Aoine an Chéasta or ; Ulster-Scots: or ), is a pair of agreements signed on 10 April 1998 that ended most of the violence of The Troubles, a political conflict in No ...

but its official usage remains divisive to certain parts of the population. The 2001 census in Northern Ireland showed that 167,487 (10.4%) people "had some knowledge of Irish". Combined, this means that around one in three people () on the island of Ireland can understand Irish at some level.

Despite the ascent in Ireland of the English and Anglicised ruling classes following the 1607

Despite the ascent in Ireland of the English and Anglicised ruling classes following the 1607 Flight of the Earls

The Flight of the Earls ( ir, Imeacht na nIarlaí)In Irish, the neutral term ''Imeacht'' is usually used i.e. the ''Departure of the Earls''. The term 'Flight' is translated 'Teitheadh na nIarlaí' and is sometimes seen. took place in Se ...

(and the disappearance of much of the Gaelic nobility), Irish was spoken by the majority of the population until the later 18th century, with a huge impact from the Great Famine of the 1840s. Disproportionately affecting the classes among whom Irish was the primary spoken language, famine and emigration precipitated a steep decline in native speakers, which only recently has begun to reverse.

The Irish language has been recognised as an official and working language of the European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational political and economic union of member states that are located primarily in Europe. The union has a total area of and an estimated total population of about 447million. The EU has often been de ...

. Ireland's national language was the twenty-third to be given such recognition by the EU and previously had the status of a treaty language.

Scottish Gaelic

Some people in the north and west of mainland Scotland and most people in theHebrides

The Hebrides (; gd, Innse Gall, ; non, Suðreyjar, "southern isles") are an archipelago off the west coast of the Scottish mainland. The islands fall into two main groups, based on their proximity to the mainland: the Inner and Outer Hebr ...

still speak Scottish Gaelic, but the language has been in decline. There are now believed to be approximately 60,000 native speakers of Scottish Gaelic in Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a Anglo-Scottish border, border with England to the southeast ...

, plus around 1,000 speakers of the Canadian Gaelic dialect in Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia ( ; ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. Nova Scotia is Latin for "New Scotland".

Most of the population are native Eng ...

.

Its historical range was much larger. For example, it was the everyday language of most of the rest of the Scottish Highlands

The Highlands ( sco, the Hielands; gd, a’ Ghàidhealtachd , 'the place of the Gaels') is a historical region of Scotland. Culturally, the Highlands and the Lowlands diverged from the Late Middle Ages into the modern period, when Lowland S ...

until little more than a century ago. Galloway

Galloway ( ; sco, Gallowa; la, Gallovidia) is a region in southwestern Scotland comprising the historic counties of Wigtownshire and Kirkcudbrightshire. It is administered as part of the council area of Dumfries and Galloway.

A native or ...

was once also a Gaelic-speaking region, but the Galwegian dialect has been extinct there for approximately three centuries. It is believed to have been home to dialects that were transitional between Scottish Gaelic and the two other Goidelic languages. While Gaelic was spoken across the Scottish Borders and Lothian during the early High Middle Ages

The High Middle Ages, or High Medieval Period, was the period of European history that lasted from AD 1000 to 1300. The High Middle Ages were preceded by the Early Middle Ages and were followed by the Late Middle Ages, which ended around AD 150 ...

it does not seem to have been spoken by the majority and was likely the language of the ruling elite, land-owners and religious clerics. Some other parts of the Scottish Lowlands spoke Cumbric

Cumbric was a variety of the Common Brittonic language spoken during the Early Middle Ages in the ''Hen Ogledd'' or "Old North" in what is now the counties of Westmorland, Cumberland and northern Lancashire in Northern England and the souther ...

, and others Scots Inglis, the only exceptions being the Northern Isles

The Northern Isles ( sco, Northren Isles; gd, Na h-Eileanan a Tuath; non, Norðreyjar; nrn, Nordøjar) are a pair of archipelagos off the north coast of mainland Scotland, comprising Orkney and Shetland. They are part of Scotland, as are th ...

of Orkney and Shetland where Norse was spoken. Scottish Gaelic was introduced across North America with Gaelic settlers. Their numbers necessitated North American Gaelic publications and print media from Cape Breton Island to California.

Scotland takes its name from the Latin word for 'Gael', ', plural ' (of uncertain etymology). ''Scotland'' originally meant ''Land of the Gaels'' in a cultural and social sense. (In early Old English texts, ''Scotland'' referred to Ireland.) Until late in the 15th century, ''Scottis'' in Scottish English

Scottish English ( gd, Beurla Albannach) is the set of varieties of the English language spoken in Scotland. The transregional, standardised variety is called Scottish Standard English or Standard Scottish English (SSE). Scottish Standard ...

(or ''Scots Inglis'') was used to refer only to Gaelic, and the speakers of this language who were identified as ''Scots''. As the ruling elite became Scots Inglis/English-speaking, ''Scottis'' was gradually associated with the land rather than the people, and the word ''Erse'' ('Irish') was gradually used more and more as an act of culturo-political disassociation, with an overt implication that the language was not really Scottish, and therefore foreign. This was something of a propaganda label, as Gaelic has been in Scotland for at least as long as English, if not longer.

In the early 16th century the dialects of northern Middle English

Middle English (abbreviated to ME) is a form of the English language that was spoken after the Norman conquest of 1066, until the late 15th century. The English language underwent distinct variations and developments following the Old English ...

, also known as Early Scots, which had developed in Lothian and had come to be spoken elsewhere in the Kingdom of Scotland

The Kingdom of Scotland (; , ) was a sovereign state in northwest Europe traditionally said to have been founded in 843. Its territories expanded and shrank, but it came to occupy the northern third of the island of Great Britain, sharing a l ...

, themselves later appropriated the name Scots. By the 17th century Gaelic speakers were restricted largely to the Highlands and the Hebrides. Furthermore, the culturally repressive measures taken against the rebellious Highland communities by The Crown

The Crown is the state in all its aspects within the jurisprudence of the Commonwealth realms and their subdivisions (such as the Crown Dependencies, overseas territories, provinces, or states). Legally ill-defined, the term has different ...

following the second Jacobite Rebellion of 1746 caused still further decline in the language's use – to a large extent by enforced emigration (e.g. the Highland Clearances). Even more decline followed in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

The Scottish Parliament has afforded the language a secure statutory status and "equal respect" (but not full equality in legal status under Scots law) with English, sparking hopes that Scottish Gaelic can be saved from extinction and perhaps even revitalised.

Manx

Long the everyday language of most of theIsle of Man

)

, anthem = "O Land of Our Birth"

, image = Isle of Man by Sentinel-2.jpg

, image_map = Europe-Isle_of_Man.svg

, mapsize =

, map_alt = Location of the Isle of Man in Europe

, map_caption = Location of the Isle of Man (green)

in Europe ...

, Manx began to decline sharply in the 19th century. The last monolingual Manx speakers are believed to have died around the middle of the 19th century; in 1874 around 30% of the population were estimated to speak Manx, decreasing to 9.1% in 1901 and 1.1% in 1921. The last native speaker of Manx, Ned Maddrell, died in 1974.

At the end of the 19th century a revival of Manx began, headed by the Manx Language Society ('). Both linguists and language enthusiasts searched out the last native speakers during the 20th century, recording their speech and learning from them. In the United Kingdom Census 2011

A census of the population of the United Kingdom is taken every ten years. The 2011 census was held in all countries of the UK on 27 March 2011. It was the first UK census which could be completed online via the Internet. The Office for National ...

, there were 1,823 Manx speakers on the island, representing 2.27% of the population of 80,398, and a steady increase in the number of speakers.

Today Manx is used as the sole medium for teaching at five of the island's pre-schools by a company named ' ("little people"), which also operates the sole Manx-medium primary school, the '. Manx is taught as a second language at all of the island's primary and secondary schools and also at the University College Isle of Man

University College Isle of Man (UCM; gv, Colleish-Olloscoill Ellan Vannin) is the primary centre for tertiary, vocational education, higher education and adult education on the British Crown dependency of the Isle of Man, located in the Manx ca ...

and Centre for Manx Studies.

Comparison

Numbers

Comparison of Goidelic numbers, including Old Irish. Welsh numbers have been included for a comparison between Goidelic and Brythonic branches.Common phrases

Influence on other languages

There are several languages that show Goidelic influence, although they are not Goidelic languages themselves: *Shelta language

Shelta (; Irish: ''Seiltis'') is a language spoken by Rilantu Mincéirí (Irish Travellers), particularly in Ireland and the United Kingdom.McArthur, T. (ed.) ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (1992) Oxford University Press It ...

is sometimes thought to be a Goidelic language, but is in fact a cant

Cant, CANT, canting, or canted may refer to:

Language

* Cant (language), a secret language

* Beurla Reagaird, a language of the Scottish Highland Travellers

* Scottish Cant, a language of the Scottish Lowland Travellers

* Shelta or the Cant, a la ...

based on Irish and English, with a primarily Irish-based grammar and English-based syntax.

*The Bungee language

Bungi (also called Bungee, Bungie, Bungay, Bangay, or the Red River Dialect) is a dialect of English with substratal influence from Scottish English, the Orcadian dialect of Scots, Norn, Scottish Gaelic, French, Cree, and Ojibwe (Saulteaux). ...

in Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

is an English dialect spoken by Métis that was influenced by Orkney English, Scots English, Cree, Ojibwe

The Ojibwe, Ojibwa, Chippewa, or Saulteaux are an Anishinaabe people in what is currently southern Canada, the northern Midwestern United States, and Northern Plains.

According to the U.S. census, in the United States Ojibwe people are one of ...

, and Scottish Gaelic

Scottish Gaelic ( gd, Gàidhlig ), also known as Scots Gaelic and Gaelic, is a Goidelic language (in the Celtic branch of the Indo-European language family) native to the Gaels of Scotland. As a Goidelic language, Scottish Gaelic, as well ...

.

* Beurla Reagaird is a cant spoken by Scottish travelling folk, which is to a large extent based on Scottish Gaelic.

* The Welsh language spoken in West Wales may still retain some influences of its Goidelic speaking past - the same applies to Cornish spoken in Western Cornwall and the English dialect of Merseyside Scouse

Scouse (; formally known as Liverpool English or Merseyside English) is an accent and dialect of English associated with Liverpool and the surrounding county of Merseyside. The Scouse accent is highly distinctive; having been influenced he ...

.

* English and especially Highland English

Highland English ( sco, Hieland Inglis) is the variety of Scottish English spoken by many in the Scottish Highlands and the Hebrides. It is more strongly influenced by Gaelic than are other forms of Scottish English.

Phonology

*The '' svarabhak ...

have numerous words of both Scottish Gaelic and Irish origin.

See also

*

* Differences between Scottish Gaelic and Irish

Although Irish Gaelic, Scottish Gaelic, and Manx Gaelic are closely related as Goidelic Celtic languages (or Gaelic languages), they are different in many ways. While most dialects are not immediately mutually comprehensible (although many indi ...

* Goidelic substrate hypothesis The Goidelic substrate hypothesis refers to the hypothesized language or languages spoken in Ireland before the Prehistoric settlement of the British Isles (disambiguation), Iron Age arrival of the Goidelic languages.

Hypothesis of non-Indo-Europea ...

* Proto-Celtic

Proto-Celtic, or Common Celtic, is the ancestral proto-language of all known Celtic languages, and a descendant of Proto-Indo-European. It is not attested in writing but has been partly reconstructed through the comparative method. Proto-Celti ...

* Specific dialects of Irish:

** Connacht Irish

Connacht Irish () is the dialect of the Irish language spoken in the province of Connacht. Gaeltacht regions in Connacht are found in Counties Mayo (notably Tourmakeady, Achill Island and Erris) and Galway (notably in parts of Connemara and o ...

** Munster Irish

Munster Irish () is the dialect of the Irish language spoken in the province of Munster. Gaeltacht regions in Munster are found in the Gaeltachtaí of the Dingle Peninsula in west County Kerry, in the Iveragh Peninsula in south Kerry, in Cap ...

** Newfoundland Irish

The Irish language was once widely spoken on the island of Newfoundland before largely disappearing there by the early 20th century.

** Ulster Irish

Ulster Irish ( ga, Gaeilig Uladh, IPA=, IPA ga=ˈɡeːlʲɪc ˌʊlˠuː) is the variety of Irish spoken in the province of Ulster. It "occupies a central position in the Gaelic world made up of Ireland, Scotland and the Isle of Man". Ulster Ir ...

* Specific dialects of Scottish Gaelic:

** Canadian Gaelic

** Galwegian Gaelic

Galwegian Gaelic (also known as Gallovidian Gaelic, Gallowegian Gaelic, or Galloway Gaelic) is an extinct dialect of Scottish Gaelic formerly spoken in southwest Scotland. It was spoken by the people of Galloway and Carrick until the ear ...

* Literature in the other languages of Britain

References

External links

* Scottish Gaelic Wikipedia * Irish language Wikipedia * Manx WikipediaComparison of Irish and Scottish Gaelic

{{DEFAULTSORT:Goidelic Languages Articles containing video clips