French battleship Justice on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Justice'' was a pre-dreadnought

The ''Liberté''-class battleships were originally intended to be part of the , which was to total six ships. After work on the first two ships had begun, the British began construction of the s. These ships carried a heavy

The ''Liberté''-class battleships were originally intended to be part of the , which was to total six ships. After work on the first two ships had begun, the British began construction of the s. These ships carried a heavy

With an initial budget of 41,565,620

With an initial budget of 41,565,620

On 16 April 1911, ''Justice'' and the rest of the fleet escorted ''Vérité'', which had aboard Fallières, the Naval Minister

On 16 April 1911, ''Justice'' and the rest of the fleet escorted ''Vérité'', which had aboard Fallières, the Naval Minister  On 19 January 1912, ''Justice'' and the battleship steamed to Malta in company with the destroyers and . ''Vérité'' joined the ships en route from Bizerte, and the five vessels arrived in Valletta on 22 January. There, they met King George V and Queen Mary of Britain, then returning from their voyage to India that year. On 24 April, ''Justice'' went to sea with ''République'' for gunnery training off the Hyères

On 19 January 1912, ''Justice'' and the battleship steamed to Malta in company with the destroyers and . ''Vérité'' joined the ships en route from Bizerte, and the five vessels arrived in Valletta on 22 January. There, they met King George V and Queen Mary of Britain, then returning from their voyage to India that year. On 24 April, ''Justice'' went to sea with ''République'' for gunnery training off the Hyères  After completing repairs, ''Justice'' returned to Les Salins in early 1914, where she and the other 2nd Squadron ships conducted torpedo training on 19 January. Later that month they steamed to Bizerte before returning to Toulon on 6 February. On 4 March, ''Justice'', ''Démocratie'', ''Vérité'', and ''République'' joined the 1st Squadron battleships and the 2nd Light Squadron for a visit to

After completing repairs, ''Justice'' returned to Les Salins in early 1914, where she and the other 2nd Squadron ships conducted torpedo training on 19 January. Later that month they steamed to Bizerte before returning to Toulon on 6 February. On 4 March, ''Justice'', ''Démocratie'', ''Vérité'', and ''République'' joined the 1st Squadron battleships and the 2nd Light Squadron for a visit to

On 8 December, the French naval command ordered ''Justice'' to steam to

On 8 December, the French naval command ordered ''Justice'' to steam to

battleship

A battleship is a large armored warship with a main battery consisting of large caliber guns. It dominated naval warfare in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The term ''battleship'' came into use in the late 1880s to describe a type of ...

built for the French Navy

The French Navy (french: Marine nationale, lit=National Navy), informally , is the maritime arm of the French Armed Forces and one of the five military service branches of France. It is among the largest and most powerful naval forces in t ...

in the early 1900s. She was the second member of the , which included three other vessels and was a derivative of the preceding , with the primary difference being the inclusion of a heavier secondary battery

A rechargeable battery, storage battery, or secondary cell (formally a type of energy accumulator), is a type of electrical battery which can be charged, discharged into a load, and recharged many times, as opposed to a disposable or prima ...

. ''Justice'' carried a main battery of four guns, like the ''République'', but mounted ten guns for her secondary armament in place of the guns of the earlier vessels. Like many late pre-dreadnought designs, ''Justice'' was completed after the revolutionary British battleship had entered service, rendering her obsolescent.

On entering service, ''Justice'' became the flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically the fi ...

of the 2nd Division of the Mediterranean Squadron, based in Toulon

Toulon (, , ; oc, label= Provençal, Tolon , , ) is a city on the French Riviera and a large port on the Mediterranean coast, with a major naval base. Located in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region, and the Provence province, Toulon is th ...

. She immediately began the normal peacetime training routine of squadron and fleet maneuvers and cruises to various ports in the Mediterranean. She also participated in several naval reviews for a number of French and foreign dignitaries. In September 1909, the ships of the 2nd Division crossed the Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe an ...

to the United States to represent France at the Hudson–Fulton Celebration. She collided with her sister ship

A sister ship is a ship of the same class or of virtually identical design to another ship. Such vessels share a nearly identical hull and superstructure layout, similar size, and roughly comparable features and equipment. They often share a ...

twice, the first in December 1913 and the second in August 1914, though she was not badly damaged in either accident.

Following the outbreak of war in July 1914, ''Justice'' was used to escort troopship convoys carrying elements of the French Army from French North Africa

French North Africa (french: Afrique du Nord française, sometimes abbreviated to ANF) is the term often applied to the territories controlled by France in the North African Maghreb during the colonial era, namely Algeria, Morocco and Tunisia. In ...

to face the Germans invading northern France. She thereafter steamed to contain the Austro-Hungarian Navy

The Austro-Hungarian Navy or Imperial and Royal War Navy (german: kaiserliche und königliche Kriegsmarine, in short ''k.u.k. Kriegsmarine'', hu, Császári és Királyi Haditengerészet) was the naval force of Austria-Hungary. Ships of the A ...

in the Adriatic Sea

The Adriatic Sea () is a body of water separating the Italian Peninsula from the Balkan Peninsula. The Adriatic is the northernmost arm of the Mediterranean Sea, extending from the Strait of Otranto (where it connects to the Ionian Sea) to t ...

, taking part in the minor Battle of Antivari in August. The increasing threat of Austro-Hungarian U-boat

U-boats were naval submarines operated by Germany, particularly in the First and Second World Wars. Although at times they were efficient fleet weapons against enemy naval warships, they were most effectively used in an economic warfare role ...

s and the unwillingness of the Austro-Hungarian fleet to engage in battle led to a period of monotonous patrols that ended with Italy's entry into the war on the side of France, which allowed the French fleet to be withdrawn. In mid-1916, she became involved in events in Greece, being stationed in Salonika

Thessaloniki (; el, Θεσσαλονίκη, , also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece, with over one million inhabitants in its metropolitan area, and the capital of the geographic region of ...

to put pressure on the Greek government to enter the war on the side of the Allies, but she saw little action for the final two years of the war.

Immediately after the end of the war, she was sent to the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal mediterranean sea of the Atlantic Ocean lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bounded by Bulgaria, Georgia, Roma ...

, first to oversee the surrender of German-occupied Russian warships there, and then to join the Allied intervention in the Russian Civil War, helping to defend Odessa

Odesa (also spelled Odessa) is the third most populous city and municipality in Ukraine and a major seaport and transport hub located in the south-west of the country, on the northwestern shore of the Black Sea. The city is also the administrativ ...

and Sevastopol

Sevastopol (; uk, Севасто́поль, Sevastópolʹ, ; gkm, Σεβαστούπολις, Sevastoúpolis, ; crh, Акъя́р, Aqyár, ), sometimes written Sebastopol, is the largest city in Crimea, and a major port on the Black Sea ...

from the Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

. By April 1919, war-weary crews demanded to return to France, leading to a mutiny

Mutiny is a revolt among a group of people (typically of a military, of a crew or of a crew of pirates) to oppose, change, or overthrow an organization to which they were previously loyal. The term is commonly used for a rebellion among member ...

aboard ''Justice'' and two other battleships, though it was quickly suppressed. ''Justice'' was used to tow the crippled battleship back to France, thereafter becoming a training ship

A training ship is a ship used to train students as sailors. The term is mostly used to describe ships employed by navies to train future officers. Essentially there are two types: those used for training at sea and old hulks used to house classr ...

. She served in this capacity only briefly, however, and was placed in reserve in April 1920, decommissioned in March 1921, and sold for scrap

Scrap consists of Recycling, recyclable materials, usually metals, left over from product manufacturing and consumption, such as parts of vehicles, building supplies, and surplus materials. Unlike waste, scrap Waste valorization, has monetary ...

in December.

Design

The ''Liberté''-class battleships were originally intended to be part of the , which was to total six ships. After work on the first two ships had begun, the British began construction of the s. These ships carried a heavy

The ''Liberté''-class battleships were originally intended to be part of the , which was to total six ships. After work on the first two ships had begun, the British began construction of the s. These ships carried a heavy secondary battery

A rechargeable battery, storage battery, or secondary cell (formally a type of energy accumulator), is a type of electrical battery which can be charged, discharged into a load, and recharged many times, as opposed to a disposable or prima ...

of guns, which prompted the French Naval General Staff to request that the last four ''République''s be redesigned to include a heavier secondary battery in response. Ironically, the designer, Louis-Émile Bertin, had proposed such an armament for the ''République'' class, but the General Staff had rejected it since the larger guns had a lower rate of fire

Rate of fire is the frequency at which a specific weapon can fire or launch its projectiles. This can be influenced by several factors, including operator training level, mechanical limitations, ammunition availability, and weapon condition. In m ...

than the smaller guns that had been selected for the ''République'' design. Because the ships were broadly similar apart from their armament, the ''Liberté''s are sometimes considered to be a sub-class of the ''République'' type.

''Justice'' was long overall

__NOTOC__

Length overall (LOA, o/a, o.a. or oa) is the maximum length of a vessel's hull measured parallel to the waterline. This length is important while docking the ship. It is the most commonly used way of expressing the size of a ship, and ...

and had a beam

Beam may refer to:

Streams of particles or energy

*Light beam, or beam of light, a directional projection of light energy

**Laser beam

*Particle beam, a stream of charged or neutral particles

**Charged particle beam, a spatially localized grou ...

of and an average draft of . She displaced up to at full load. The battleship was powered by three vertical triple-expansion steam engines, each driving one propeller shaft using steam provided by twenty-four Niclausse boiler

A Field-tube boiler (also known as a bayonet tube)

is a form of water-tube boiler where the water tubes are single-ended. The tubes are closed at one end, and they contain a concentric inner tube. Flow is thus separated into the colder inner flow ...

s. They were rated at and provided a top speed of . Coal storage amounted to , which provided a maximum range of at a cruising speed of . She had a crew of 32 officers and 710 enlisted men.

''Justice''s main battery consisted of four Modèle 1893/96 guns mounted in two twin-gun turret

A gun turret (or simply turret) is a mounting platform from which weapons can be fired that affords protection, visibility and ability to turn and aim. A modern gun turret is generally a rotatable weapon mount that houses the crew or mechani ...

s, one forward and one aft of the superstructure

A superstructure is an upward extension of an existing structure above a baseline. This term is applied to various kinds of physical structures such as buildings, bridges, or ships.

Aboard ships and large boats

On water craft, the superstruct ...

. The secondary battery consisted of ten Modèle 1902 guns; six were mounted in single turrets, and four in casemate

A casemate is a fortified gun emplacement or armored structure from which artillery, guns are fired, in a fortification, warship, or armoured fighting vehicle.Webster's New Collegiate Dictionary

When referring to Ancient history, antiquity, th ...

s in the hull. She also carried thirteen Modèle 1902 guns and ten Modèle 1902 guns for defense against torpedo boats. The ship was also armed with two torpedo tube

A torpedo tube is a cylindrical device for launching torpedoes.

There are two main types of torpedo tube: underwater tubes fitted to submarines and some surface ships, and deck-mounted units (also referred to as torpedo launchers) installed aboa ...

s, which were submerged in the hull on the broadside

Broadside or broadsides may refer to:

Naval

* Broadside (naval), terminology for the side of a ship, the battery of cannon on one side of a warship, or their near simultaneous fire on naval warfare

Printing and literature

* Broadside (comic ...

.

The ship's main belt was thick in the central citadel, and was connected to two armored decks; the upper deck was thick while the lower deck was thick, with sloped sides. The main battery guns were protected by up to of armor on the fronts of the turrets, while the secondary turrets had of armor on the faces. The casemates were protected with of steel plate. The conning tower

A conning tower is a raised platform on a ship or submarine, often armored, from which an officer in charge can conn the vessel, controlling movements of the ship by giving orders to those responsible for the ship's engine, rudder, lines, and gro ...

had thick sides.

Modifications

The navy carried out tests to determine whether the main battery turrets could be modified to increase the elevation of the guns (and hence their range), which determined that the turrets could not be altered. Instead, the navy found that tanks on either side of the vessel could be flooded to induce aheel

The heel is the prominence at the posterior end of the foot. It is based on the projection of one bone, the calcaneus or heel bone, behind the articulation of the bones of the lower Human leg, leg.

Structure

To distribute the compressive for ...

of 2 degrees. This increased the maximum range of the guns from . New motors were installed in the secondary turrets in 1915–1916 to improve their training and elevation rates. Also in 1915, the 47 mm guns located on either side of the bridge

A bridge is a structure built to span a physical obstacle (such as a body of water, valley, road, or rail) without blocking the way underneath. It is constructed for the purpose of providing passage over the obstacle, which is usually somethi ...

were removed and the two on the aft superstructure were moved to the roof of the rear turret. On 8 December 1915, the naval command issued orders that the light battery was to be revised to eight of the 47 mm guns and ten guns. The light battery was revised again in 1916, with the four 47 mm guns being converted with high-angle anti-aircraft mounts. They were placed atop the rear main battery turret and the number 7 and 8 secondary turret roofs.

In 1912–1913, the ship received two Barr & Stroud

Barr & Stroud Limited was a pioneering Glasgow optical engineering firm. They played a leading role in the development of modern optics, including rangefinders, for the Royal Navy and for other branches of British Armed Forces during the 20th ce ...

rangefinders; by the end of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, the ship had been fitted with two rangefinders in addition to the 2 m rangefinders. One of the latter was moved to the aft superstructure and configured for high-angle fire control.

Service history

Construction – 1910

With an initial budget of 41,565,620

With an initial budget of 41,565,620 French francs

The franc (, ; sign: F or Fr), also commonly distinguished as the (FF), was a currency of France. Between 1360 and 1641, it was the name of coins worth 1 livre tournois and it remained in common parlance as a term for this amount of money. It w ...

, ''Justice'' was laid down

Laying the keel or laying down is the formal recognition of the start of a ship's construction. It is often marked with a ceremony attended by dignitaries from the shipbuilding company and the ultimate owners of the ship.

Keel laying is one o ...

at the La Seyne shipyard in Toulon

Toulon (, , ; oc, label= Provençal, Tolon , , ) is a city on the French Riviera and a large port on the Mediterranean coast, with a major naval base. Located in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region, and the Provence province, Toulon is th ...

on 1 April 1903, launched on 27 October 1904, and completed on 15 April 1908. This was over a year after the revolutionary British battleship entered service, which had rendered pre-dreadnoughts like ''Justice'' outdated. After commissioning, ''Justice'' was assigned to the 2nd Division of the Mediterranean Squadron, serving as its flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically the fi ...

, along with her sisters and . '' Contre-amiral'' (''CA''—Rear admiral) Jules Le Pord was the divisional commander at that time, and he came aboard the ship on 16 April. Beginning on 10 June and lasting into July, the Mediterranean and Northern Squadrons conducted their annual maneuvers off Bizerte

Bizerte or Bizerta ( ar, بنزرت, translit=Binzart , it, Biserta, french: link=no, Bizérte) the classical Hippo, is a city of Bizerte Governorate in Tunisia. It is the northernmost city in Africa, located 65 km (40mil) north of the cap ...

. The 2nd Division ships visited Bizerte in October. On 30 December, ''Justice'', ''Vérité'', and the destroyer

In naval terminology, a destroyer is a fast, manoeuvrable, long-endurance warship intended to escort

larger vessels in a fleet, convoy or battle group and defend them against powerful short range attackers. They were originally developed in ...

s and carried relief aid to Messina

Messina (, also , ) is a harbour city and the capital of the Italian Metropolitan City of Messina. It is the third largest city on the island of Sicily, and the 13th largest city in Italy, with a population of more than 219,000 inhabitants in ...

, Sicily to help survivors of an earthquake there.

The entire squadron was moored in Villefranche in February 1909 and thereafter conducted training exercises off Corsica

Corsica ( , Upper , Southern ; it, Corsica; ; french: Corse ; lij, Còrsega; sc, Còssiga) is an island in the Mediterranean Sea and one of the 18 regions of France. It is the fourth-largest island in the Mediterranean and lies southeast of ...

, followed by a naval review in Villefranche for President Armand Fallières on 26 April. During this period of training, on 17 March, ''Justice'' and the battleships ''Liberté'', , and conducted gunnery training, using the old ironclad

An ironclad is a steam engine, steam-propelled warship protected by Wrought iron, iron or steel iron armor, armor plates, constructed from 1859 to the early 1890s. The ironclad was developed as a result of the vulnerability of wooden warships ...

as a target

Target may refer to:

Physical items

* Shooting target, used in marksmanship training and various shooting sports

** Bullseye (target), the goal one for which one aims in many of these sports

** Aiming point, in field artillery, fi ...

. In June, ''République'', ''Justice'', and the protected cruiser got underway for training in the Atlantic; they met ''Patrie'', ''Démocratie'', ''Liberté'', and the armored cruiser at Cádiz

Cádiz (, , ) is a city and port in southwestern Spain. It is the capital of the Province of Cádiz, one of eight that make up the autonomous community of Andalusia.

Cádiz, one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in Western Europe, ...

, Spain on 12 June. Training included serving as targets for the fleet's submarine

A submarine (or sub) is a watercraft capable of independent operation underwater. It differs from a submersible, which has more limited underwater capability. The term is also sometimes used historically or colloquially to refer to remotely op ...

s in the Pertuis d'Antioche

The Pertuis d'Antioche (, ''Passage of Antioch'') is a strait on the Atlantic coast of Western France, between two islands, Île de Ré and Oléron, on the one side, and on the other side the continental coast between the cities of La Rochelle and ...

strait. The ships then steamed north to La Pallice, where they conducted tests with their wireless sets and gunnery training in Quiberon Bay

Quiberon Bay (french: Baie de Quiberon) is an area of sheltered water on the south coast of Brittany. The bay is in the Morbihan département.

Geography

The bay is roughly triangular in shape, open to the south with the Gulf of Morbihan to t ...

. From 8 to 15 July, the ships lay at Brest

Brest may refer to:

Places

*Brest, Belarus

**Brest Region

**Brest Airport

**Brest Fortress

*Brest, Kyustendil Province, Bulgaria

*Břest, Czech Republic

*Brest, France

**Arrondissement of Brest

**Brest Bretagne Airport

** Château de Brest

*Brest, ...

and the next day, they steamed to Le Havre

Le Havre (, ; nrf, Lé Hâvre ) is a port city in the Seine-Maritime department in the Normandy region of northern France. It is situated on the right bank of the estuary of the river Seine on the Channel southwest of the Pays de Caux, very cl ...

. There, they met the Northern Squadron for another fleet review for Fallières on 17 July. Ten days later, the combined fleet steamed to Cherbourg

Cherbourg (; , , ), nrf, Chèrbourg, ) is a former commune and subprefecture located at the northern end of the Cotentin peninsula in the northwestern French department of Manche. It was merged into the commune of Cherbourg-Octeville on 28 Feb ...

, where they held another fleet review, this time during the visit of Czar Nicholas II of Russia.

On 12 September, ''Justice'' and the other 2nd Division battleships departed Brest, bound for the United States. There they represented France during the Hudson–Fulton Celebration, which marked the 300th anniversary of the European discovery of the Hudson River

The Hudson River is a river that flows from north to south primarily through eastern New York. It originates in the Adirondack Mountains of Upstate New York and flows southward through the Hudson Valley to the New York Harbor between N ...

. The ships arrived back in Toulon on 27 October. ''Justice'' joined ''Patrie'', ''République'', ''Vérité'', ''Démocratie'', and ''Suffren'' for a simulated attack on the port of Nice

Nice ( , ; Niçard: , classical norm, or , nonstandard, ; it, Nizza ; lij, Nissa; grc, Νίκαια; la, Nicaea) is the prefecture of the Alpes-Maritimes department in France. The Nice agglomeration extends far beyond the administrative c ...

on 18 February 1910. The ships of the 1st Squadron held training exercises off Sardinia and Algeria from 21 May to 4 June, followed by combined maneuvers with the 2nd Squadron from 7 to 18 June. ''Justice'' began having trouble with her main battery, so she went into the shipyard in Toulon from 13 to 21 July for repairs. An outbreak of typhoid

Typhoid fever, also known as typhoid, is a disease caused by '' Salmonella'' serotype Typhi bacteria. Symptoms vary from mild to severe, and usually begin six to 30 days after exposure. Often there is a gradual onset of a high fever over several ...

among the crews of the battleships in early December forced the navy to confine them to Golfe-Juan to contain the fever. By 15 December, the outbreak had subsided.

1911–1914

On 16 April 1911, ''Justice'' and the rest of the fleet escorted ''Vérité'', which had aboard Fallières, the Naval Minister

On 16 April 1911, ''Justice'' and the rest of the fleet escorted ''Vérité'', which had aboard Fallières, the Naval Minister Théophile Delcassé

Théophile Delcassé (1 March 185222 February 1923) was a French politician who served as foreign minister from 1898 to 1905. He is best known for his hatred of Germany and efforts to secure alliances with Russia and Great Britain that became t ...

, and Charles Dumont, the Minister of Public Works, Posts and Telegraphs The Minister of Public Works, Posts and Telegraphs (french: Ministre des Travaux publics, des Postes et des Télégraphes) in the French cabinet was responsible from 25 October 1906 to 22 March 1913 for a combined portfolio formerly divided between ...

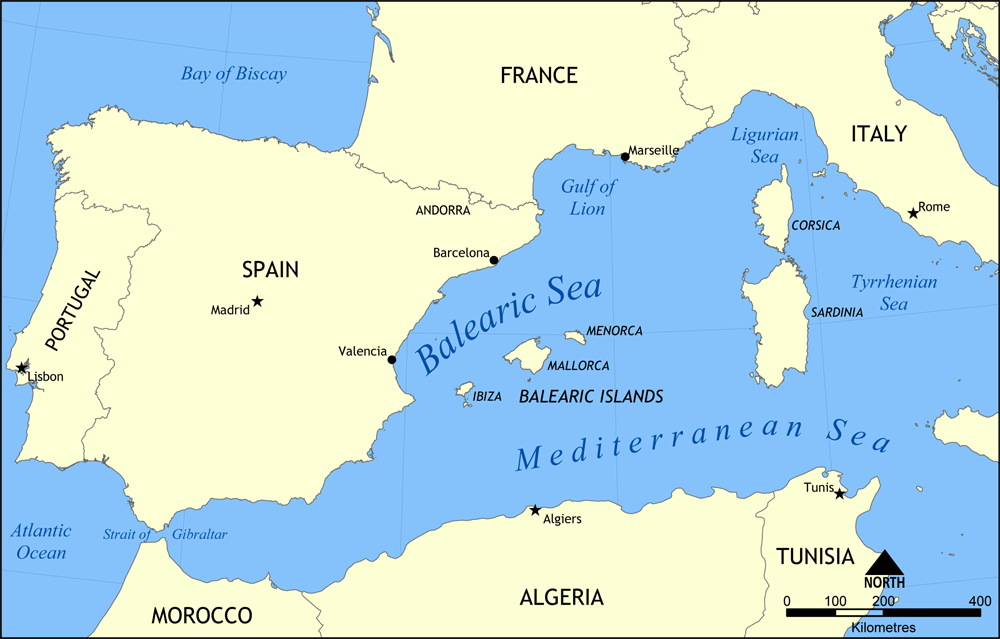

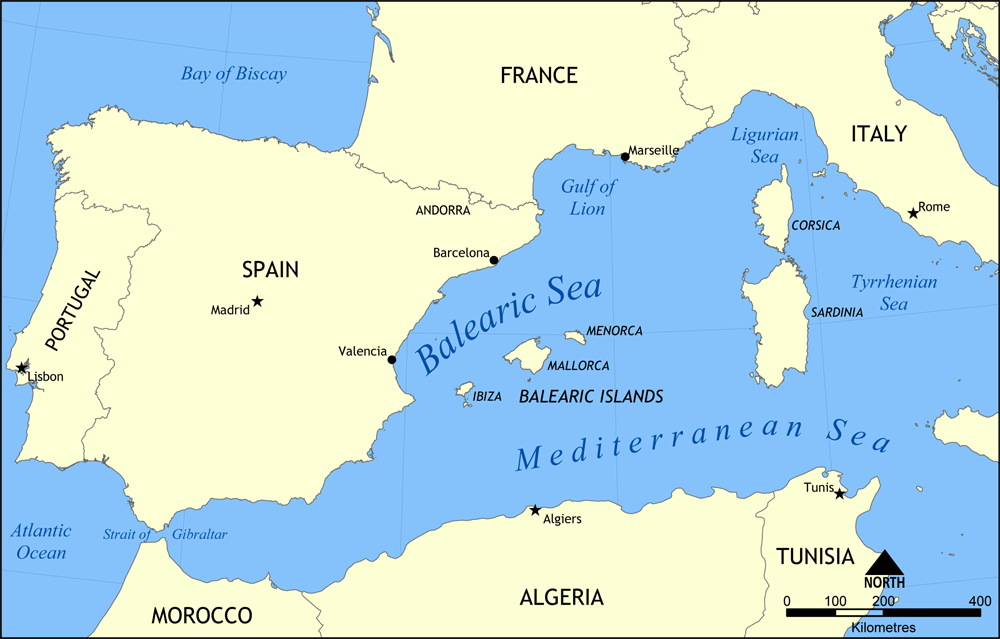

, to Bizerte. They arrived two days later and held a fleet review that included two British battleships, two Italian battleships, and a Spanish cruiser on 19 April. The fleet returned to Toulon on 29 April, where Fallières doubled the crews' rations and suspended any punishments to thank the men for their performance. ''Justice'' and the rest of 1st Squadron and the armored cruisers ''Ernest Renan'' and went on a cruise in the western Mediterranean in May and June, visiting a number of ports including Cagliari

Cagliari (, also , , ; sc, Casteddu ; lat, Caralis) is an Italian municipality and the capital of the island of Sardinia, an autonomous region of Italy. Cagliari's Sardinian name ''Casteddu'' means ''castle''. It has about 155,000 inhabitant ...

, Bizerte, Bône, Philippeville, Algiers

Algiers ( ; ar, الجزائر, al-Jazāʾir; ber, Dzayer, script=Latn; french: Alger, ) is the capital and largest city of Algeria. The city's population at the 2008 Census was 2,988,145Census 14 April 2008: Office National des Statistiques ...

, and Bougie. By 1 August, the battleships of the had begun to enter service, and they were assigned to the 1st Squadron, displacing the ''Liberté'' and ''République''-class ships to the 2nd Squadron. On 4 September, both squadrons held a major fleet review for Fallières off Toulon. The fleet then departed on 11 September for maneuvers off Golfe-Juan and Marseille, returning to Toulon on 16 September.

On 25 September, ''Liberté'' was destroyed by a magazine

A magazine is a periodical publication, generally published on a regular schedule (often weekly or monthly), containing a variety of content. They are generally financed by advertising, purchase price, prepaid subscriptions, or by a combinatio ...

explosion; a commission was convened aboard ''Justice'' the following day to investigate the accident. Just a month later, on 26 October, ''Justice'' also caught fire and two of her 194 mm and one of her 47 mm magazines had to be flooded to prevent a similar explosion. The fire was believed to have been started by a short circuit in the electrical system near the forward magazines. The fire nearly reached the ammunition in the magazines when the ship's commander ordered the magazines to be flooded, averting a catastrophic explosion. This occurred just days after the battleship had to flood her magazines to put out another accidental fire. The fleet thereafter made cruises to Les Salins d'Hyères, Le Lavandou

Le Lavandou (; oc, Lo Lavandor) is a commune in the Var department in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region in southeastern France. It derives its name either from the flower lavender (''lavanda'' in Provençal) that is prevalent in the area, o ...

, and Porquerolles through 15 December. At some point in 1911, the ship was featured in the film ''A Day on the French battleship "Justice"''.

On 19 January 1912, ''Justice'' and the battleship steamed to Malta in company with the destroyers and . ''Vérité'' joined the ships en route from Bizerte, and the five vessels arrived in Valletta on 22 January. There, they met King George V and Queen Mary of Britain, then returning from their voyage to India that year. On 24 April, ''Justice'' went to sea with ''République'' for gunnery training off the Hyères

On 19 January 1912, ''Justice'' and the battleship steamed to Malta in company with the destroyers and . ''Vérité'' joined the ships en route from Bizerte, and the five vessels arrived in Valletta on 22 January. There, they met King George V and Queen Mary of Britain, then returning from their voyage to India that year. On 24 April, ''Justice'' went to sea with ''République'' for gunnery training off the Hyères roadstead

A roadstead (or ''roads'' – the earlier form) is a body of water sheltered from rip currents, spring tides, or ocean swell where ships can lie reasonably safely at anchor without dragging or snatching.United States Army technical manual, TM 5- ...

; they were joined by ''Patrie'' and ''Vérité'' the next day. Admiral Augustin Boué de Lapeyrère inspected both battleship squadrons in Golfe-Juan from 2 to 12 July, after which the ships cruised first to Corsica and then to Algeria. The rest of the year passed uneventfully for ''Justice''.

In early 1913, ''Justice'' and the rest of the 2nd Squadron took part in training exercises off Le Lavandou. The French fleet, which by then included sixteen battleships, held large-scale maneuvers between Toulon and Sardinia beginning on 19 May. The exercises concluded with a fleet review for President Raymond Poincaré

Raymond Nicolas Landry Poincaré (, ; 20 August 1860 – 15 October 1934) was a French statesman who served as President of France from 1913 to 1920, and three times as Prime Minister of France.

Trained in law, Poincaré was elected deputy in 1 ...

. Gunnery practice followed from 1 to 4 July. The 2nd Squadron departed Toulon on 23 August with the armored cruisers and and two destroyer flotillas to conduct training exercises in the Atlantic. While en route to Brest, the ships stopped in Tangier, Royan, Le Verdon, La Pallice, Quiberon Bay, and Cherbourg. They reached Brest on 20 September, where they met a Russian squadron of four battleships and five cruisers. The ships then steamed back south, stopping in Cádiz, Tangier, Mers El Kébir

Mers El Kébir ( ar, المرسى الكبير, translit=al-Marsā al-Kabīr, lit=The Great Harbor ) is a port on the Mediterranean Sea, near Oran in Oran Province, northwest Algeria. It is famous for the attack on the French fleet in 1940, in t ...

, Algiers, and Bizerte before ultimately arriving back in Toulon on 1 November. On 3 December, ''République'', ''Justice'', ''Vérité'', and ''Démocratie'' conducted torpedo training and range-finding drills. While anchored at Les Salins on the night of 19/20 December, heavy winds blew ''Démocratie'' into ''Justice''; ''Démocratie''s port screw cut through ''Justice''s starboard anchor chain and the collision knocked two of ''Justice''s armor plates from her bow. Both vessels were forced to return to Toulon for repairs.

After completing repairs, ''Justice'' returned to Les Salins in early 1914, where she and the other 2nd Squadron ships conducted torpedo training on 19 January. Later that month they steamed to Bizerte before returning to Toulon on 6 February. On 4 March, ''Justice'', ''Démocratie'', ''Vérité'', and ''République'' joined the 1st Squadron battleships and the 2nd Light Squadron for a visit to

After completing repairs, ''Justice'' returned to Les Salins in early 1914, where she and the other 2nd Squadron ships conducted torpedo training on 19 January. Later that month they steamed to Bizerte before returning to Toulon on 6 February. On 4 March, ''Justice'', ''Démocratie'', ''Vérité'', and ''République'' joined the 1st Squadron battleships and the 2nd Light Squadron for a visit to Porto-Vecchio

Porto-Vecchio (, ; it, Porto Vecchio or ; co, Portivechju or ) is a commune in the French department of Corse-du-Sud, on the island of Corsica.

Porto-Vecchio is a medium-sized port city placed on a good harbor, the southernmost of the mars ...

, Sardinia. On 30 March, the 2nd Squadron ships steamed to Malta to visit the British Mediterranean Fleet

The British Mediterranean Fleet, also known as the Mediterranean Station, was a formation of the Royal Navy. The Fleet was one of the most prestigious commands in the navy for the majority of its history, defending the vital sea link between t ...

, remaining there until 3 April. The squadron visited various ports in June, but following the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand and the ensuing July Crisis, the fleet remained close to port, making only short training sorties as international tensions rose.

World War I

Following the outbreak of World War I in July 1914, France announced general mobilization on 1 August. The next day, Boué de Lapeyrère ordered the entire French fleet to begin raising steam at 22:15 so the ships could sortie early the next day. Faced with the prospect that the GermanMediterranean Division

The Mediterranean Division (german: Mittelmeerdivision) was a division consisting of the battlecruiser and the light cruiser of the German ''Kaiserliche Marine'' (Imperial Navy) in the early 1910s. It was established in response to the First Balk ...

—centered on the battlecruiser

The battlecruiser (also written as battle cruiser or battle-cruiser) was a type of capital ship of the first half of the 20th century. These were similar in displacement, armament and cost to battleships, but differed in form and balance of attr ...

—might attack the troopships carrying the French Army in North Africa to metropolitan France, the French fleet was tasked with providing heavy escort to the convoys. Accordingly, ''Justice'' and the rest of the 2nd Squadron were sent to Algiers, where they joined a group of seven passenger ship

A passenger ship is a merchant ship whose primary function is to carry passengers on the sea. The category does not include cargo vessels which have accommodations for limited numbers of passengers, such as the ubiquitous twelve-passenger freig ...

s that had a contingent of 7,000 troops from XIX Corps aboard. By this time, ''Justice'' was serving as the flagship of ''CA'' Tracou, the commander of the 2nd Division of the 2nd Squadron. While at sea, the new dreadnought battleships and and the ''Danton''-class battleships and , took over as the convoy's escort. Instead of attacking the convoys, ''Goeben'' bombarded Bône and Philippeville and then fled east to the Ottoman Empire.

On 12 August, France and Britain declared war on the Austro-Hungarian Empire

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

as the war continued to widen. The 1st and 2nd Squadrons were therefore sent to the southern Adriatic Sea

The Adriatic Sea () is a body of water separating the Italian Peninsula from the Balkan Peninsula. The Adriatic is the northernmost arm of the Mediterranean Sea, extending from the Strait of Otranto (where it connects to the Ionian Sea) to t ...

to contain the Austro-Hungarian Navy

The Austro-Hungarian Navy or Imperial and Royal War Navy (german: kaiserliche und königliche Kriegsmarine, in short ''k.u.k. Kriegsmarine'', hu, Császári és Királyi Haditengerészet) was the naval force of Austria-Hungary. Ships of the A ...

. On 15 August, the two squadrons arrived off the Strait of Otranto

The Strait of Otranto ( sq, Ngushtica e Otrantos; it, Canale d'Otranto; hr, Otrantska Vrata) connects the Adriatic Sea with the Ionian Sea and separates Italy from Albania. Its width at Punta Palascìa, east of Salento is less than . The st ...

, where they met the patrolling British cruisers and north of Othonoi. Boué de Lapeyrère then took the fleet into the Adriatic in an attempt to force a battle with the Austro-Hungarian fleet; the following morning, the British and French cruisers spotted vessels in the distance that, on closing with them, turned out to be the protected cruiser and the torpedo boat , which were trying to blockade the coast of Montenegro. In the ensuing Battle of Antivari, Boué de Lapeyrère initially ordered his battleships to fire warning shots, but this caused confusion among the fleet's gunners that allowed ''Ulan'' to escape. The slower ''Zenta'' attempted to evade, but she quickly received several hits that disabled her engines and set her on fire. She sank shortly thereafter and the Anglo-French fleet withdrew. In the course of the battle, a shell exploded in ''Justice''s starboard forward 194 mm casemate gun.

The French fleet patrolled the southern end of the Adriatic for the next three days with the expectation that the Austro-Hungarians would counterattack, but their opponent never arrived. At 09:20 on 17 August, ''Justice'' and ''Démocratie'' collided in heavy fog; the latter vessel lost her rudder and center screw, while ''Justice'' had her bow dented in. ''Justice'' withdrew to Malta for repairs, which only took four days to complete, and she returned to the fleet on 27 August. On 1 September, the French battleships then bombarded Austrian fortifications at Cattaro on 1 September in an attempt to draw out the Austro-Hungarian fleet, which again refused to take the bait. In addition, many of the ships still had shells loaded from the battle with ''Zenta'', and the guns could not be emptied apart from by firing them. On 18–19 September, the fleet made another incursion into the Adriatic, steaming as far north as the island of Lissa.

The fleet continued these operations in October and November, including a sweep off the coast of Montenegro to cover a group of merchant vessels replenishing their coal there. Throughout this period, the battleships rotated through Malta or Toulon for periodic maintenance; Corfu became the primary naval base in the area. The patrols continued through late December, when an Austro-Hungarian U-boat

U-boats were naval submarines operated by Germany, particularly in the First and Second World Wars. Although at times they were efficient fleet weapons against enemy naval warships, they were most effectively used in an economic warfare role ...

torpedoed ''Jean Bart'', leading to the decision by the French naval command to withdraw the main battle fleet from direct operations in the Adriatic. For the rest of the month, the fleet remained at Navarino Bay

Pylos (, ; el, Πύλος), historically also known as Navarino, is a town and a former municipality in Messenia, Peloponnese, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform, it has been part of the municipality Pylos-Nestoras, of which it is th ...

. The battle fleet thereafter occupied itself with patrols between Kythira and Crete; these sweeps continued until 7 May. Following the Italian entry into the war on the side of France, the French fleet handed control of the Adriatic operations to the Italian '' Regia Marina'' (Royal Navy) and withdrew its fleet to Malta and Bizerte, the latter becoming the main fleet base.

''Justice'' and ''Démocratie'' were detached from the main fleet in January 1916 to reinforce the Dardanelles Division, though the Allies evacuated their forces fighting there that month. In June, the French battle fleet was reorganized; ''Justice'', her two sisters, the two ''République''-class ships, and ''Suffren'' were assigned to the 3rd Squadron. The ships were tasked with pressuring the Greek government, which to that point had remained neutral, since King Constantine I

Constantine I ( , ; la, Flavius Valerius Constantinus, ; ; 27 February 22 May 337), also known as Constantine the Great, was Roman emperor from AD 306 to 337, the first one to convert to Christianity. Born in Naissus, Dacia Mediterranea ...

's wife Sophie

Sophie is a version of the female given name Sophia, meaning "wise".

People with the name Born in the Middle Ages

* Sophie, Countess of Bar (c. 1004 or 1018–1093), sovereign Countess of Bar and lady of Mousson

* Sophie of Thuringia, Duchess o ...

was the sister of the German Kaiser Wilhelm II. The French and British were growing increasingly frustrated by Constantine's refusal to enter the war, and sent the 3rd Squadron to Salonika try to influence events in the country. Over the course of June and July, the ships alternated between Salonika and Mudros, and later that month the fleet was transferred to Cephalonia

Kefalonia or Cephalonia ( el, Κεφαλονιά), formerly also known as Kefallinia or Kephallenia (), is the largest of the Ionian Islands in western Greece and the 6th largest island in Greece after Crete, Euboea, Lesbos, Rhodes and Chios. It i ...

.

In August, a pro-Allied group launched a coup against the Greek monarchy in the ''Noemvriana

The ''Noemvriana'' ( el, Νοεμβριανά, "November Events") of , or the Greek Vespers, was a political dispute which led to an armed confrontation in Athens between the royalist government of Greece and the forces of the Allies over th ...

'', which the Allies sought to support. Several French ships sent men ashore in Athens on 1 December to support the coup, but they were quickly defeated by the royalist Greek Army. In response, the British and French fleet imposed a blockade of the royalist-controlled parts of the country. By June 1917, Constantine had been forced to abdicate and the 3rd Squadron was disbanded; ''Justice'' returned to the 2nd Squadron on 1 July, which included the other ''Liberté''-class ships and three of the ''Danton''-class battleships. They remained in Corfu, largely immobilized due to shortages of coal, preventing training until late September 1918. In late October, members of the Central Powers began signing armistices with the British and French, signaling the end of the war. The 2nd Squadron ships were sent to Constantinople to oversee the surrender of Ottoman forces, and ''Justice'' and ''Démocratie'' proceeded into the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal mediterranean sea of the Atlantic Ocean lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bounded by Bulgaria, Georgia, Roma ...

, where they supervised the transfer of Russian warships that had been seized by the Germans back to Russian control.

Postwar career

On 8 December, the French naval command ordered ''Justice'' to steam to

On 8 December, the French naval command ordered ''Justice'' to steam to Odessa

Odesa (also spelled Odessa) is the third most populous city and municipality in Ukraine and a major seaport and transport hub located in the south-west of the country, on the northwestern shore of the Black Sea. The city is also the administrativ ...

to join the battleship , which was observing clashes between the communist Bolshevik and White forces during the Russian Civil War, part of the Allied intervention into the conflict. Three days later, when the Bolshevik forces appeared ready to advance into the city, ''Justice'', ''Mirabeau'', and the armored cruiser sent landing parties ashore to strengthen the White defenses. On 1 January 1919, ''Justice'' had returned to Constantinople; by that time, the French fleet in the Black Sea had been designated the 2nd Squadron, and it also included ''Démocratie'', the ''Danton''-class ships and ''Vergniaud'', and the dreadnought . The French squadron was thereafter tasked with supporting the White defenses of Sevastopol and blockading the coast of Ukraine, which had largely fallen to the control of the Bolsheviks.

By mid-April, the French command had reached the decision to withdraw French forces from active participation in the conflict, which led the crews of the ships to believe they would soon return home. When, on 19 April, it had become clear that this was not the case, men aboard ''Justice'', ''France'', and ''Jean Bart'' mutinied. The situation worsened after a group of Greek soldiers fired into a crowd of demonstrators ashore; one French sailor was killed and another five were injured. ''Justice''s crew was enraged, and began discussing opening fire on the Greek battleship , moored nearby. ''Justice''s captain ordered his ship's guns disabled by removing their breech blocks to prevent an attack. This intervention was enough to convince the crew to abandon the mutiny, though the crews of the dreadnoughts continued. The situation was eventually defused by returning the French squadron back to France, one of the mutineers' primary demands.

In the meantime, ''Mirabeau'' had run aground and been badly damaged in February and was refloated in April and taken into Sevastopol for repairs. The imminent threat of the Bolshevik conquest of the city forced her to be towed out of port by ''Justice'' on 5 May. She took the crippled battleship to Constantinople, where they stayed from 7 to 15 May before departing for France. On passing through the Dardanelles, both ships' crews held ceremonies to honor the men killed aboard the battleship during the Dardanelles campaign in 1915. To avoid further damage to ''Mirabeau'', ''Justice'' was limited to a speed of for the entire voyage. The ships reached Toulon on 24 May. On 6 June, ''Justice'' again acted as a tug, taking the minesweeping sloop

A sloop is a sailboat with a single mast typically having only one headsail in front of the mast and one mainsail aft of (behind) the mast. Such an arrangement is called a fore-and-aft rig, and can be rigged as a Bermuda rig with triangular sa ...

from Toulon to Brest, arriving there on 17 June. ''Justice'' thereafter was reduced to a training ship

A training ship is a ship used to train students as sailors. The term is mostly used to describe ships employed by navies to train future officers. Essentially there are two types: those used for training at sea and old hulks used to house classr ...

. On 1 April 1920, she was placed in special reserve and towed to the naval station of Landévennec

Landévennec (; ) is a commune in the Finistère department of Brittany in north-western France. Population

Geography

Landévennec is located on the Crozon peninsula, southeast of Brest.The river Aulne forms a natural boundary to the east. ...

on 27 April. She was decommissioned on 1 March 1921 and struck on 29 November. She was sold to ship breaker

''Ship Breaker'' is a 2010 young adult novel by Paolo Bacigalupi set in a post-apocalyptic future. Human civilization is in decline for ecological reasons. The polar ice caps have melted and New Orleans is underwater. On the Gulf Coast nea ...

s on 30 December, towed to Hamburg, Germany, and broken up in 1922.

Footnotes

References

* * * * * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Justice Liberté-class battleships Ships built in France