French battleship Dunkerque on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

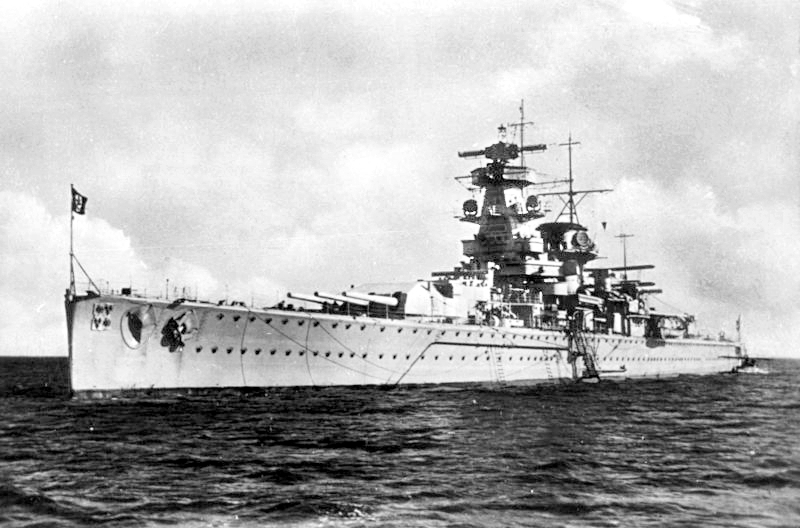

''Dunkerque'' was the lead ship of the of

The French Navy's design staff spent the decade following the 1922

The French Navy's design staff spent the decade following the 1922

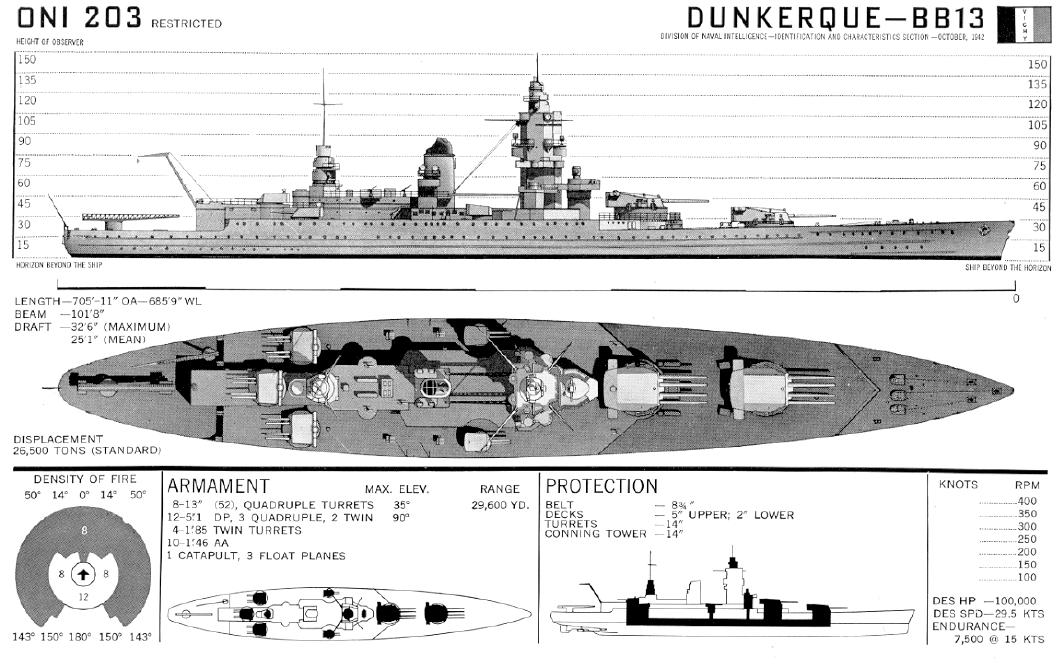

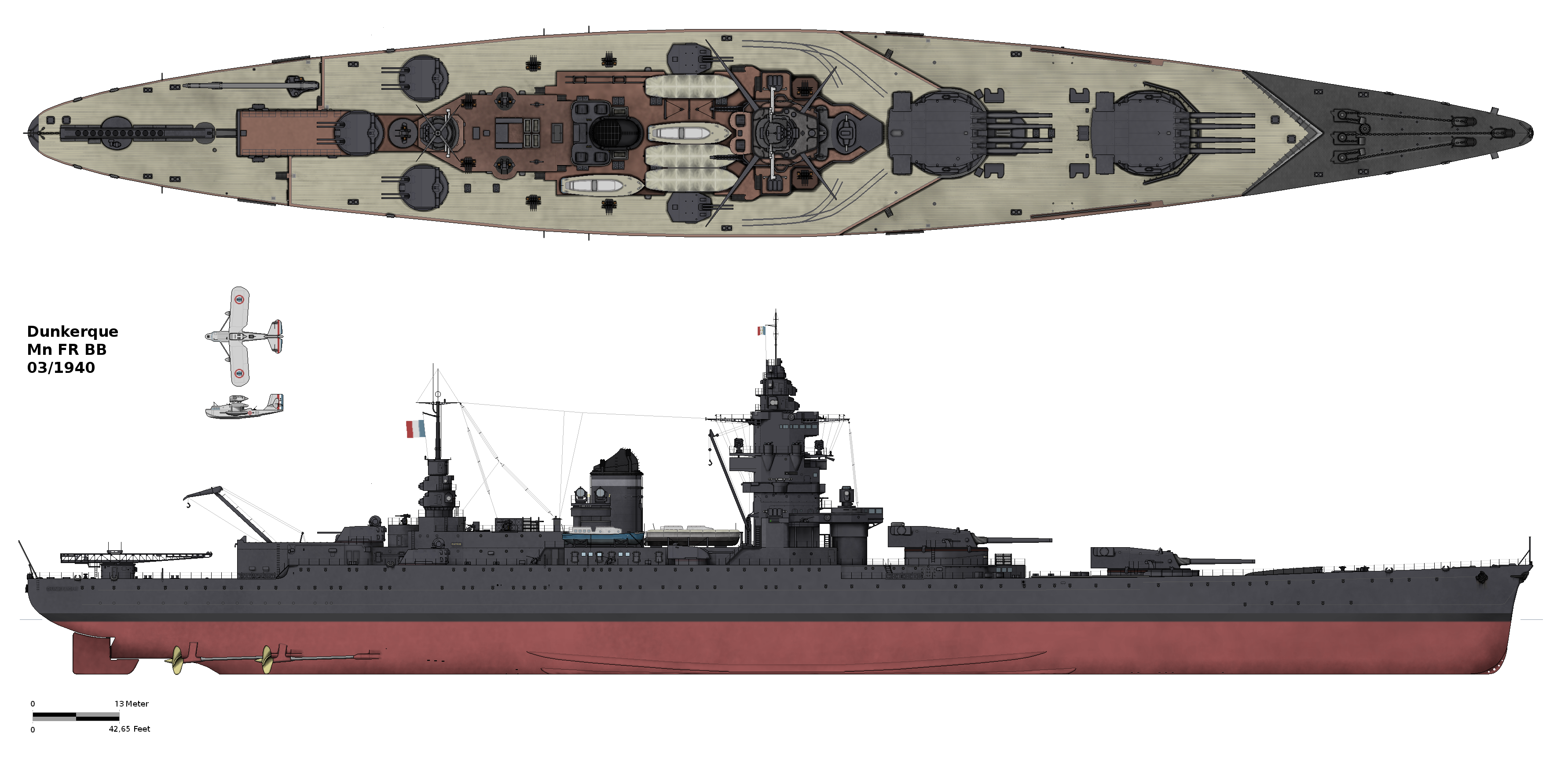

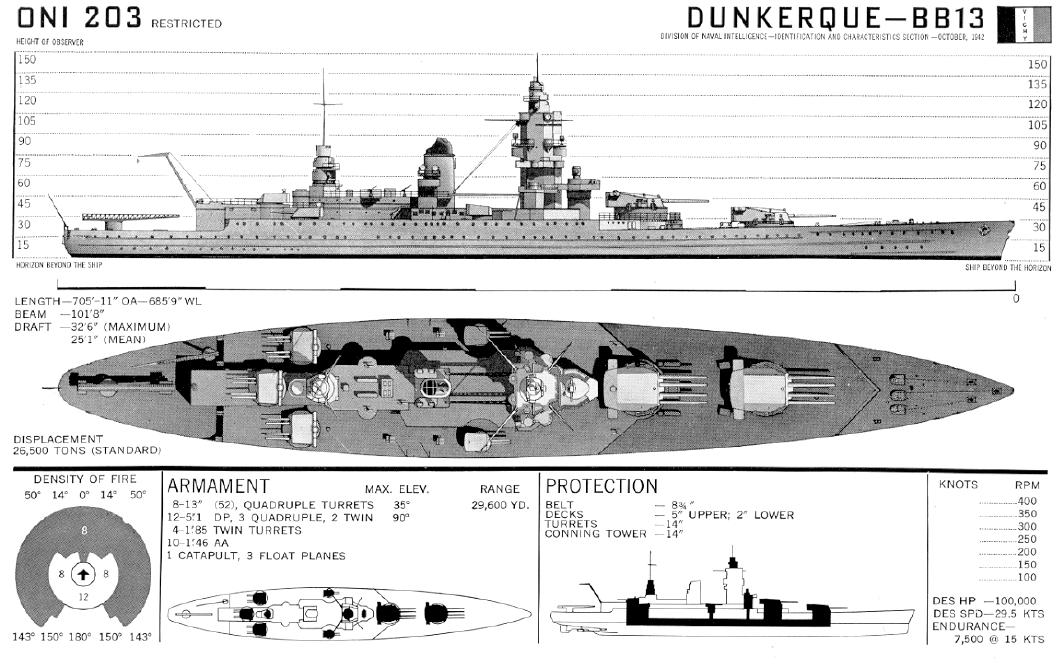

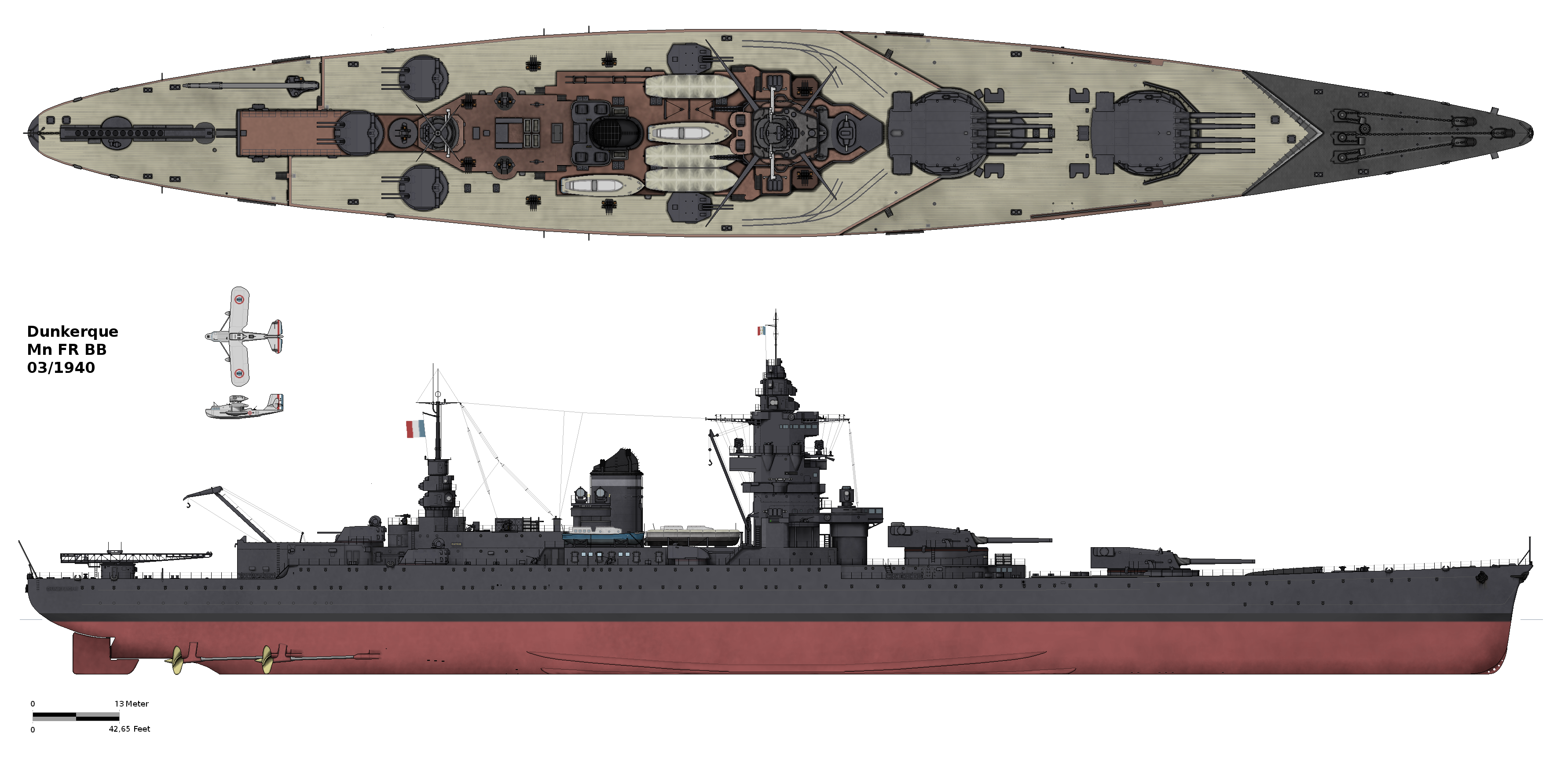

''Dunkerque'' displaced as built and fully loaded, with an overall length of , a beam of and a maximum draft of . She was powered by four Parsons geared steam turbines and six oil-fired Indret boilers, which developed a total of and yielded a maximum speed of . Her crew numbered between 1,381 and 1,431 officers and men. The ship carried a pair of spotter aircraft on the

''Dunkerque'' displaced as built and fully loaded, with an overall length of , a beam of and a maximum draft of . She was powered by four Parsons geared steam turbines and six oil-fired Indret boilers, which developed a total of and yielded a maximum speed of . Her crew numbered between 1,381 and 1,431 officers and men. The ship carried a pair of spotter aircraft on the

After entering service, ''Dunkerque'' continued her training program, though she was now included in exercises with the rest of the squadron. At the time, the squadron included the three s (the 2nd Battle Division), three cruisers (the 4th Cruiser Division), the

After entering service, ''Dunkerque'' continued her training program, though she was now included in exercises with the rest of the squadron. At the time, the squadron included the three s (the 2nd Battle Division), three cruisers (the 4th Cruiser Division), the

In August, as tensions with Germany were again heightened, this time over territorial demands on Poland, the French and British navies discussed coordination in the event of war with Germany; they agreed that the French would be responsible for covering Allied shipping south from the English Channel to the

In August, as tensions with Germany were again heightened, this time over territorial demands on Poland, the French and British navies discussed coordination in the event of war with Germany; they agreed that the French would be responsible for covering Allied shipping south from the English Channel to the  On arriving in Brest on 3 December, ''Dunkerque'' was docked for repairs to her bow. The experience off Iceland had highlighted defects with her design, including insufficient freeboard and insufficiently strong construction. These problems could not be easily corrected, however, leaving the ''Dunkerque''s vulnerable to storm damage. On 11 December, ''Dunkerque'' and the cruiser carried a shipment of part of the

On arriving in Brest on 3 December, ''Dunkerque'' was docked for repairs to her bow. The experience off Iceland had highlighted defects with her design, including insufficient freeboard and insufficiently strong construction. These problems could not be easily corrected, however, leaving the ''Dunkerque''s vulnerable to storm damage. On 11 December, ''Dunkerque'' and the cruiser carried a shipment of part of the

The only test in battle for ''Dunkerque'' came in the

The only test in battle for ''Dunkerque'' came in the  The third shell hit the ship shortly after 18:00; this projectile struck the upper edge of the belt on the starboard side; since the belt had only been designed to defeat German shells, the much more powerful British shell easily perforated it. The shell then passed through the handling room for the starboard secondary turret No. III, igniting propellant charges and detonating a pair of 130 mm shells as it did so. The 15 in round then penetrated an internal bulkhead and exploded in the medical storage room. The blast caused extensive internal damage, allowing smoke from the ammunition fire to enter the machinery spaces, which had to be abandoned, though debris from the explosion had jammed the armored doors shut. Only a dozen men were able to escape using a ladder at the forward end of the room. The fourth shell struck the belt aft of the third hit and at the waterline. It also defeated the belt and the torpedo bulkhead and then exploded in boiler room 2, causing extensive damage to the propulsion machinery. ''Dunkerque'' rapidly lost speed and then all electrical power; unable to get underway or further resist the British ships, ''Dunkerque'' was beached on the other side of Mers-el-Kébir

The third shell hit the ship shortly after 18:00; this projectile struck the upper edge of the belt on the starboard side; since the belt had only been designed to defeat German shells, the much more powerful British shell easily perforated it. The shell then passed through the handling room for the starboard secondary turret No. III, igniting propellant charges and detonating a pair of 130 mm shells as it did so. The 15 in round then penetrated an internal bulkhead and exploded in the medical storage room. The blast caused extensive internal damage, allowing smoke from the ammunition fire to enter the machinery spaces, which had to be abandoned, though debris from the explosion had jammed the armored doors shut. Only a dozen men were able to escape using a ladder at the forward end of the room. The fourth shell struck the belt aft of the third hit and at the waterline. It also defeated the belt and the torpedo bulkhead and then exploded in boiler room 2, causing extensive damage to the propulsion machinery. ''Dunkerque'' rapidly lost speed and then all electrical power; unable to get underway or further resist the British ships, ''Dunkerque'' was beached on the other side of Mers-el-Kébir

Repair work proceeded slowly, owing to a shortage of material and labor. After the

Repair work proceeded slowly, owing to a shortage of material and labor. After the  Italy received control of most of the wrecks, and they decided to repair as many ships as possible for service with the Italian fleet, but to

Italy received control of most of the wrecks, and they decided to repair as many ships as possible for service with the Italian fleet, but to

Maritimequest Dunkerque Photo Gallery

{{DEFAULTSORT:Dunkerque Dunkerque-class battleships World War II battleships of France Maritime incidents in July 1940 Shipwrecks of France World War II shipwrecks in the Mediterranean Sea 1935 ships World War II warships scuttled at Toulon Maritime incidents in November 1942 Scuttled vessels

battleship

A battleship is a large armour, armored warship with a main artillery battery, battery consisting of large caliber guns. It dominated naval warfare in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The term ''battleship'' came into use in the late 1 ...

s built for the French Navy

The French Navy (french: Marine nationale, lit=National Navy), informally , is the maritime arm of the French Armed Forces and one of the five military service branches of France. It is among the largest and most powerful naval forces in t ...

in the 1930s. The class also included . The two ships were the first capital ship

The capital ships of a navy are its most important warships; they are generally the larger ships when compared to other warships in their respective fleet. A capital ship is generally a leading or a primary ship in a naval fleet.

Strategic im ...

s to be built by the French Navy after World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

; the planned and es had been cancelled at the outbreak of war, and budgetary problems prevented the French from building new battleships in the decade after the war. ''Dunkerque'' was laid down

Laying the keel or laying down is the formal recognition of the start of a ship's construction. It is often marked with a ceremony attended by dignitaries from the shipbuilding company and the ultimate owners of the ship.

Keel laying is one o ...

in December 1932, was launched October 1935, and was completed in May 1937. She was armed with a main battery of eight 330mm/50 Modèle 1931 guns arranged in two quadruple gun turret

A gun turret (or simply turret) is a mounting platform from which weapons can be fired that affords protection, visibility and ability to turn and aim. A modern gun turret is generally a rotatable weapon mount that houses the crew or mechanis ...

s and had a top speed of .

''Dunkerque'' and ''Strasbourg'' formed the French Navy's ''1ère Division de Ligne'' (1st Division of the Line) prior to the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

. The two ships searched for German commerce raiders in the early months of the war, and ''Dunkerque'' also participated in convoy escort duties. The ship was badly damaged during the British attack at Mers-el-Kébir after the Armistice

An armistice is a formal agreement of warring parties to stop fighting. It is not necessarily the end of a war, as it may constitute only a cessation of hostilities while an attempt is made to negotiate a lasting peace. It is derived from the ...

that ended the first phase of France's participation in World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, but she was refloated and partially repaired to return to Toulon

Toulon (, , ; oc, label= Provençal, Tolon , , ) is a city on the French Riviera and a large port on the Mediterranean coast, with a major naval base. Located in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region, and the Provence province, Toulon is th ...

for comprehensive repairs. ''Dunkerque'' was scuttled

Scuttling is the deliberate sinking of a ship. Scuttling may be performed to dispose of an abandoned, old, or captured vessel; to prevent the vessel from becoming a navigation hazard; as an act of self-destruction to prevent the ship from being ...

in November 1942 to prevent her capture by the Germans, and subsequently seized and partially scrapped by the Italians and later the Germans. Her wreck remained in Toulon until she was stricken in 1955, and scrapped three years later.

Development

The French Navy's design staff spent the decade following the 1922

The French Navy's design staff spent the decade following the 1922 Washington Naval Treaty

The Washington Naval Treaty, also known as the Five-Power Treaty, was a treaty signed during 1922 among the major Allies of World War I, which agreed to prevent an arms race by limiting naval construction. It was negotiated at the Washington Nav ...

attempting to produce a satisfactory design to fill 70,000 tons as allowed by the treaty. Initially, the French sought a reply to the Italian s of 1925, but all proposals were rejected. A 17,500-ton cruiser, which could have handled the ''Trento''s, was inadequate against the old Italian battleships, however, and the 37,000-ton battlecruiser concepts were prohibitively expensive and would jeopardize further naval limitation talks. These attempts were followed by an intermediate design for a 23,690-ton protected cruiser

Protected cruisers, a type of naval cruiser of the late-19th century, gained their description because an armoured deck offered protection for vital machine-spaces from fragments caused by shells exploding above them. Protected cruisers re ...

in 1929; it was armed with guns, armored against guns, and had a speed of . Visually, it bore a profile strikingly similar to the final ''Dunkerque''.

The German s became the new focus for French naval architects in 1929. The design had to respect the 1930 London Naval Treaty

The London Naval Treaty, officially the Treaty for the Limitation and Reduction of Naval Armament, was an agreement between the United Kingdom, Japan, France, Italy, and the United States that was signed on 22 April 1930. Seeking to address is ...

, which limited the French to two 23,333-ton ships until 1936. Drawing upon previous work, the French developed a 23,333-ton design armed with 305 mm guns, armored against the German cruisers' guns, and with a speed of . As with the final ''Dunkerque'', the main artillery was concentrated entirely forward. The design was rejected by the French parliament in July 1931 and sent back for revision. The final revision grew to 26,500 tons; the 305 mm guns were replaced by 330mm/50 Modèle 1931 guns, the armor was slightly improved, and the speed slightly decreased. Parliamentary approval was granted in early 1932, and ''Dunkerque'' was ordered on 26 October.

Characteristics

fantail

Fantails are small insectivorous songbirds of the genus ''Rhipidura'' in the family Rhipiduridae, native to Australasia, Southeast Asia and the Indian subcontinent. Most of the species are about long, specialist aerial feeders, and named a ...

, and the aircraft facilities consisted of a steam catapult

A catapult is a ballistic device used to launch a projectile a great distance without the aid of gunpowder or other propellants – particularly various types of ancient and medieval siege engines. A catapult uses the sudden release of stor ...

and a crane to handle the floatplanes.

She was armed with eight 330mm/50 Modèle 1931 guns arranged in two quadruple gun turret

A gun turret (or simply turret) is a mounting platform from which weapons can be fired that affords protection, visibility and ability to turn and aim. A modern gun turret is generally a rotatable weapon mount that houses the crew or mechanis ...

s, both of which were placed in a superfiring pair forward of the superstructure. Her secondary armament consisted of sixteen /45 dual-purpose guns; these were mounted in three quadruple and two twin turrets. The quadruple turrets were placed on the stern, and the twin turrets were located amidships

This glossary of nautical terms is an alphabetical listing of terms and expressions connected with ships, shipping, seamanship and navigation on water (mostly though not necessarily on the sea). Some remain current, while many date from the 17t ...

. Close range antiaircraft defense was provided by a battery of eight guns in twin mounts and thirty-two guns in quadruple mounts. The ship's belt armor

Belt armor is a layer of heavy metal armor plated onto or within the outer hulls of warships, typically on battleships, battlecruisers and cruisers, and aircraft carriers.

The belt armor is designed to prevent projectiles from penetrating to ...

was thick amidships, and the main battery turrets were protected by of armor plate on the faces. The main armored deck was thick, and the conning tower

A conning tower is a raised platform on a ship or submarine, often armored, from which an officer in charge can conn the vessel, controlling movements of the ship by giving orders to those responsible for the ship's engine, rudder, lines, and gro ...

had thick sides.

Modifications

''Dunkerque'' was modified several times throughout her relatively short career. In 1937, afunnel

A funnel is a tube or pipe that is wide at the top and narrow at the bottom, used for guiding liquid or powder into a small opening.

Funnels are usually made of stainless steel, aluminium, glass, or plastic. The material used in its construct ...

cap was added and four of the 37 mm guns, which were the Modèle 1925 variant, were removed. These were replaced the following year with new Modèle 1933 guns. The 13.2 mm guns were also rearranged slightly, with the two mounts that were located abreast of the second main battery turret moved further aft. A new rangefinder

A rangefinder (also rangefinding telemeter, depending on the context) is a device used to measure distances to remote objects. Originally optical devices used in surveying, they soon found applications in other fields, such as photography an ...

was installed in 1940 on the fore tower.

Service history

Construction and working up

''Dunkerque'' waslaid down

Laying the keel or laying down is the formal recognition of the start of a ship's construction. It is often marked with a ceremony attended by dignitaries from the shipbuilding company and the ultimate owners of the ship.

Keel laying is one o ...

in the Arsenal de Brest, on 24 December 1932, in the Salou graving dock number 4. The hull was completed except for the forward-most section, since the dock was only long. She was launched on 2 October 1935 and towed to Laninon graving dock number 8, where the bow was fitted. After that was completed, she was towed out to the ''Quai d'Armement'' to have her armament installed and begin fitting-out

Fitting out, or outfitting, is the process in shipbuilding that follows the float-out/launching of a vessel and precedes sea trials. It is the period when all the remaining construction of the ship is completed and readied for delivery to her o ...

. Sea trials were carried out, starting on 18 April 1936, at which time her superstructure

A superstructure is an upward extension of an existing structure above a baseline. This term is applied to various kinds of physical structures such as buildings, bridges, or ships.

Aboard ships and large boats

On water craft, the superstruct ...

was not yet complete, and many of her secondary and anti-aircraft guns had not been installed. Two days later, she returned to Brest and had her machinery inspected before further trials through May. Her formal evaluation began on 22 May and continued until 9 October. On 4 February 1937, ''Dunkerque'' got underway for shooting trials to test the ship's secondary guns; she had aboard '' Vice-amiral'' (''VA''—Vice Admiral) Morris and '' Contre-amiral'' (''CA''—Rear Admiral) Rivet to observe the tests. Main battery tests were delayed by bad weather from 8 February to 11–14 February. ''VA'' François Darlan, the Chief of the Naval General Staff, came aboard on 3 March to observe further gunnery tests. The tests continued through April.

''VA'' Devin, the ''Préfet maritime de la 2e région'' (Prefect of the 2nd Maritime Region), came aboard ''Dunkerque'' on 15 May to take the ship to represent France at the Naval Review

A fleet review or naval review is an event where a gathering of ships from a particular navy is paraded and reviewed by an incumbent head of state and/or other official civilian and military dignitaries. A number of national navies continue to ...

marking the coronation of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth

The coronation of George VI and his wife, Elizabeth, as King and Queen of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Commonwealth, and as Emperor and Empress of India took place at Westminster Abbey, London, on Wednesday 12 May ...

. The ship left Brest on 17 May for the review and arrived back on 23 May. She participated in another review off the Île de Sein on 27 May, where she hosted Darlan and Alphonse Gasnier-Duparc

Alphonse Henri Gasnier-Duparc (21 June 1879, Dol-de-Bretagne – 10 October 1945, Saint-Malo) was a French politician. He served as mayor of Saint-Malo, senator for Ille-et-Vilaine (1932-1940) and List of Naval Ministers of France, Naval Minister. ...

, the Naval Minister. Gunnery testing resumed after the review and continued into mid-June, at which point she returned to the shipyard in Brest for further work. In late July, she went to sea for further trials before returning to Brest for additional work that lasted from 15 August to 14 October. In early 1938, the crew prepared the ship for her first major cruise to test her ability to operate at extended ranges, which began on 20 January. The voyage took the ship on a tour of French colonial possessions in the Atlantic; ports of call included Fort-de-France

Fort-de-France (, , ; gcf, label= Martinican Creole, Fodfwans) is a commune and the capital city of Martinique, an overseas department and region of France located in the Caribbean. It is also one of the major cities in the Caribbean.

Histo ...

in the Antilles

The Antilles (; gcf, label=Antillean Creole, Antiy; es, Antillas; french: Antilles; nl, Antillen; ht, Antiy; pap, Antias; Jamaican Patois: ''Antiliiz'') is an archipelago bordered by the Caribbean Sea to the south and west, the Gulf of Mex ...

(from 31 January to 4 February) and Dakar

Dakar ( ; ; wo, Ndakaaru) (from daqaar ''tamarind''), is the capital and largest city of Senegal. The city of Dakar proper has a population of 1,030,594, whereas the population of the Dakar metropolitan area is estimated at 3.94 million in 2 ...

, Senegal

Senegal,; Wolof: ''Senegaal''; Pulaar: 𞤅𞤫𞤲𞤫𞤺𞤢𞥄𞤤𞤭 (Senegaali); Arabic: السنغال ''As-Sinighal'') officially the Republic of Senegal,; Wolof: ''Réewum Senegaal''; Pulaar : 𞤈𞤫𞤲𞤣𞤢𞥄𞤲𞤣𞤭 ...

(from 25 February to 1 March). She returned to Brest on 6 March, thereafter conducting more gunnery testing on 11 March.

''Dunkerque'' underwent another period of equipment inspections and gunnery testing after her return from the voyage that continued into May. From 1 to 4 July, she steamed to the English Channel

The English Channel, "The Sleeve"; nrf, la Maunche, "The Sleeve" ( Cotentinais) or ( Jèrriais), ( Guernésiais), "The Channel"; br, Mor Breizh, "Sea of Brittany"; cy, Môr Udd, "Lord's Sea"; kw, Mor Bretannek, "British Sea"; nl, Het Ka ...

to visit her namesake town, returning to Brest on 6 July by way of a stay in Saint-Vaast-la-Hougue

Saint-Vaast-la-Hougue is a commune in the Manche department in Normandy in north-western France.

Toponymy

Saint-Vaast is the Norman name of Saint Vedast and Hougue is a Norman language word meaning a "mound" or "loaf" and comes from the Old No ...

on 4–5 July. George VI and Elizabeth were visiting Boulogne

Boulogne-sur-Mer (; pcd, Boulonne-su-Mér; nl, Bonen; la, Gesoriacum or ''Bononia''), often called just Boulogne (, ), is a coastal city in Northern France. It is a sub-prefecture of the department of Pas-de-Calais. Boulogne lies on the C ...

on 16 July, so ''Dunkerque'' left Brest that day in company with a group of warships to visit the British monarch there. ''Dunkerque'' got underway again on 22 July, bound for Calais

Calais ( , , traditionally , ) is a port city in the Pas-de-Calais department, of which it is a subprefecture. Although Calais is by far the largest city in Pas-de-Calais, the department's prefecture is its third-largest city of Arras. Th ...

, where she saluted the British Royal Family as they left for home. On 1 September, ''Dunkerque'' was finally pronounced ready for service and was assigned to the Atlantic Squadron, becoming the flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically the ...

of its commander, ''Vice-amiral d'Escadre'' (Squadron Vice Admiral) Marcel-Bruno Gensoul

Marcel-Bruno Gensoul (12 October 1880 – 30 December 1973) was a French admiral who commanded the Force de Raid, based at Brest until the Armistice of 22 June 1940. Then, the force was transferred to Mers El Kébir in French North Africa.

Gen ...

.

Prewar service

After entering service, ''Dunkerque'' continued her training program, though she was now included in exercises with the rest of the squadron. At the time, the squadron included the three s (the 2nd Battle Division), three cruisers (the 4th Cruiser Division), the

After entering service, ''Dunkerque'' continued her training program, though she was now included in exercises with the rest of the squadron. At the time, the squadron included the three s (the 2nd Battle Division), three cruisers (the 4th Cruiser Division), the aircraft carrier

An aircraft carrier is a warship that serves as a seagoing airbase, equipped with a full-length flight deck and facilities for carrying, arming, deploying, and recovering aircraft. Typically, it is the capital ship of a fleet, as it allows a ...

, and numerous destroyer

In naval terminology, a destroyer is a fast, manoeuvrable, long-endurance warship intended to escort

larger vessels in a fleet, convoy or battle group and defend them against powerful short range attackers. They were originally developed ...

s and torpedo boat

A torpedo boat is a relatively small and fast naval ship designed to carry torpedoes into battle. The first designs were steam-powered craft dedicated to ramming enemy ships with explosive spar torpedoes. Later evolutions launched variants of ...

s. From 18 to 20 October, she took part in maneuvers with ''Béarn'', two torpedo boats, and a sloop

A sloop is a sailboat with a single mast typically having only one headsail in front of the mast and one mainsail aft of (behind) the mast. Such an arrangement is called a fore-and-aft rig, and can be rigged as a Bermuda rig with triangular sa ...

off the coast of Brittany

Brittany (; french: link=no, Bretagne ; br, Breizh, or ; Gallo: ''Bertaèyn'' ) is a peninsula, historical country and cultural area in the west of modern France, covering the western part of what was known as Armorica during the period ...

. ''Dunkerque'' departed Brest on 8 November in company with ''Béarn'' and the 4th Cruiser Division for a visit to Cherbourg

Cherbourg (; , , ), nrf, Chèrbourg, ) is a former commune and subprefecture located at the northern end of the Cotentin peninsula in the northwestern French department of Manche. It was merged into the commune of Cherbourg-Octeville on 28 Febr ...

to celebrate the twentieth anniversary of the Armistice with Germany

The Armistice of 11 November 1918 was the armistice signed at Le Francport near Compiègne that ended fighting on land, sea, and air in World War I between the Entente and their last remaining opponent, Germany. Previous armistices ...

that ended World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

. The ships thereafter got underway for training exercises that concluded with a return to Brest on 17 November. ''Dunkerque'' then used the wreck of the old battleship as a target before returning to the shipyard for maintenance that lasted until 27 February 1939.

The next day, ''Dunkerque'' sortied to take part in maneuvers with the Atlantic Squadron off the Brittany coast; another stint in the shipyard for repairs followed from 17 March to 3 April. Gunnery training off the coast of Brittany from 4 to 7 April. In response to the Sudetenland Crisis over Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

's demand to annex the Sudetenland

The Sudetenland ( , ; Czech and sk, Sudety) is the historical German name for the northern, southern, and western areas of former Czechoslovakia which were inhabited primarily by Sudeten Germans. These German speakers had predominated in the ...

region of Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

, the French naval command sent elements of the Atlantic Squadron, including ''Dunkerque'', three light cruiser

A light cruiser is a type of small or medium-sized warship. The term is a shortening of the phrase "light armored cruiser", describing a small ship that carried armor in the same way as an armored cruiser: a protective belt and deck. Prior to th ...

s, and eight large destroyers, on 14 April to cover the training cruiser as it returned from a cruise to the French West Indies

The French West Indies or French Antilles (french: Antilles françaises, ; gcf, label= Antillean Creole, Antiy fwansez) are the parts of France located in the Antilles islands of the Caribbean:

* The two overseas departments of:

** Guadeloupe ...

; at the time, a German squadron centered on the large heavy cruiser

The heavy cruiser was a type of cruiser, a naval warship designed for long range and high speed, armed generally with naval guns of roughly 203 mm (8 inches) in caliber, whose design parameters were dictated by the Washington Naval T ...

was off the coast of Spain. The ships returned to port two days later. On 24 April, the squadron was joined by ''Dunkerque''s sister ship

A sister ship is a ship of the same class or of virtually identical design to another ship. Such vessels share a nearly identical hull and superstructure layout, similar size, and roughly comparable features and equipment. They often share a ...

; the two ships were designated the 1st Battle Division. The ships received identification stripes on their funnels, one for ''Dunkerque'' as division leader, and two for ''Strasbourg''.

The squadron went to sea again the next day for exercises that lasted until 29 April. On 1 May, ''Strasbourg'' joined ''Dunkerque'' for the first time for a cruise to Lisbon

Lisbon (; pt, Lisboa ) is the capital and largest city of Portugal, with an estimated population of 544,851 within its administrative limits in an area of 100.05 km2. Lisbon's urban area extends beyond the city's administrative limits w ...

, Portugal on 1 May, arriving there two days later for a celebration of the anniversary of Pedro Álvares Cabral

Pedro Álvares Cabral ( or ; born Pedro Álvares de Gouveia; c. 1467 or 1468 – c. 1520) was a Portuguese nobleman, military commander, navigator and explorer regarded as the European discoverer of Brazil. He was the first human ...

's discovery of Brazil. The ships left Lisbon on 4 May and arrived in Brest three days later. There, they met a British squadron of warships that were visiting the port at the time. The two ''Dunkerque''-class ships sortied on 23 May in company with the 4th Cruiser Division and three destroyer divisions for maneuvers held off the coast of Great Britain. ''Dunkerque'' and ''Strasbourg'' then visited a number of British ports, including Liverpool

Liverpool is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the List of English districts by population, 10th largest English district by population and its E ...

from 25 to 30 May, Oban

Oban ( ; ' in Scottish Gaelic meaning ''The Little Bay'') is a resort town within the Argyll and Bute council area of Scotland. Despite its small size, it is the largest town between Helensburgh and Fort William. During the tourist season, ...

from 31 May to 4 June, Staffa on 4 June, Loch Ewe

Loch Ewe ( gd, Loch Iùbh) is a sea loch in the region of Wester Ross in the Northwest Highlands of Scotland. The shores are inhabited by a traditionally Gàidhlig-speaking people living in or sustained by crofting villages, the most notab ...

from 5 to 7 June, Scapa Flow

Scapa Flow viewed from its eastern end in June 2009

Scapa Flow (; ) is a body of water in the Orkney Islands, Scotland, sheltered by the islands of Mainland, Graemsay, Burray,S. C. George, ''Jutland to Junkyard'', 1973. South Ronaldsay a ...

on 8 June, Rosyth from 9 to 14 June, before stopping in Le Havre

Le Havre (, ; nrf, Lé Hâvre ) is a port city in the Seine-Maritime department in the Normandy region of northern France. It is situated on the right bank of the estuary of the river Seine on the Channel southwest of the Pays de Caux, very ...

, France from 16 to 20 June. The ships arrived back in Brest the next day. The squadron conducted more training off Brittany through July and into early August.

World War II

In August, as tensions with Germany were again heightened, this time over territorial demands on Poland, the French and British navies discussed coordination in the event of war with Germany; they agreed that the French would be responsible for covering Allied shipping south from the English Channel to the

In August, as tensions with Germany were again heightened, this time over territorial demands on Poland, the French and British navies discussed coordination in the event of war with Germany; they agreed that the French would be responsible for covering Allied shipping south from the English Channel to the Gulf of Guinea

The Gulf of Guinea is the northeasternmost part of the tropical Atlantic Ocean from Cape Lopez in Gabon, north and west to Cape Palmas in Liberia. The intersection of the Equator and Prime Meridian (zero degrees latitude and longitude) is i ...

in central Africa. To protect shipping from German commerce raiders, the French created the ''Force de Raid

The ''Force de Raid'' (Raiding Force) was a French naval squadron formed at Brest during naval mobilization for World War II. The squadron commanded by Vice Amiral d'Escadre Marcel Gensoul consisted of the most modern French capital ships ''D ...

'' (Raiding Force), with ''Dunkerque'' and ''Strasbourg'' as its core. The group, which was under Gensoul's command, also included three light cruisers and eight large destroyers, and was based in Brest. British observers informed the French Navy that the German "pocket battleships" of the ''Deutschland'' class had gone to sea in late August, bound for the Atlantic, and that contact with the vessels had been lost. On 2 September, the day after Germany invaded Poland, but before France and Britain declared war, the ''Force de Raid'' sortied from Brest to guard against a possible attack by the ''Deutschland''s. Upon learning that the German ships had been spotted in the North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Norway, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium. An epeiric sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian ...

, Gensoul ordered his ships to return to port after they met the French passenger liner

A passenger ship is a merchant ship whose primary function is to carry passengers on the sea. The category does not include cargo vessels which have accommodations for limited numbers of passengers, such as the ubiquitous twelve-passenger freig ...

in the Azores

)

, motto =( en, "Rather die free than subjected in peace")

, anthem= ( en, "Anthem of the Azores")

, image_map=Locator_map_of_Azores_in_EU.svg

, map_alt=Location of the Azores within the European Union

, map_caption=Location of the Azores wi ...

. The ''Force de Raid'' escorted the liner back to port and arrived in Brest on 6 September.

By this time, the German raiders had broken out into the Atlantic, so the British and French fleets formed hunter groups to track them down; the ''Force de Raid'' was split, with ''Dunkerque'' and ''Strasbourg'' operating individually as Force L and Force X, respectively. ''Dunkerque'', ''Béarn'', and three cruisers remained in Brest while ''Strasbourg'' and two French heavy cruisers joined the British aircraft carrier , based in Dakar. On 22 October, ''Dunkeque'' and two cruisers sortied with their destroyer screen to cover Convoy KJ 3 to Kingston, Jamaica

Kingston is the capital and largest city of Jamaica, located on the southeastern coast of the island. It faces a natural harbour protected by the Palisadoes, a long sand spit which connects the town of Port Royal and the Norman Manley Inte ...

, arriving back in Brest three days later. On 25 November, they again went to sea, joining the battlecruiser

The battlecruiser (also written as battle cruiser or battle-cruiser) was a type of capital ship of the first half of the 20th century. These were similar in displacement, armament and cost to battleships, but differed in form and balance of attr ...

for a patrol to try to catch the German battleships and , which had just sunk the British armed merchant cruiser

An armed merchantman is a merchant ship equipped with guns, usually for defensive purposes, either by design or after the fact. In the days of sail, piracy and privateers, many merchantmen would be routinely armed, especially those engaging in lo ...

. While cruising off Iceland, ''Dunkerque'' ran into very heavy seas; her bow was repeatedly submerged by the large waves, and she had to slow to to avoid damage. The Germans had by this time returned to port, so the Anglo-French force returned to its ports.

On arriving in Brest on 3 December, ''Dunkerque'' was docked for repairs to her bow. The experience off Iceland had highlighted defects with her design, including insufficient freeboard and insufficiently strong construction. These problems could not be easily corrected, however, leaving the ''Dunkerque''s vulnerable to storm damage. On 11 December, ''Dunkerque'' and the cruiser carried a shipment of part of the

On arriving in Brest on 3 December, ''Dunkerque'' was docked for repairs to her bow. The experience off Iceland had highlighted defects with her design, including insufficient freeboard and insufficiently strong construction. These problems could not be easily corrected, however, leaving the ''Dunkerque''s vulnerable to storm damage. On 11 December, ''Dunkerque'' and the cruiser carried a shipment of part of the Banque de France

The Bank of France (French: ''Banque de France''), headquartered in Paris, is the central bank of France. Founded in 1800, it began as a private institution for managing state debts and issuing notes. It is responsible for the accounts of the ...

's gold reserve to Canada. The ships arrived on 17 December and covered a convoy of seven troop ship

A troopship (also troop ship or troop transport or trooper) is a ship used to carry soldiers, either in peacetime or wartime. Troopships were often drafted from commercial shipping fleets, and were unable land troops directly on shore, typical ...

s that was also escorted by the battleship on the return voyage. While still at sea on 29 December, the convoy met the local escort forces in the Western Approaches, which took over responsibility of the convoy, allowing ''Dunkerque'' and ''Gloire'' to detach for Brest. After arriving there on 4 January 1940, ''Dunkerque'' underwent another period of maintenance that lasted until 6 February. The ship then conducted sea trials and training maneuvers from 21 February to 23 March.

Faced with increasingly hostile posturing by Italy during the spring of 1940, the ''Force de Raid'' was dispatched to Mers-el-Kébir on 2 April. ''Dunkerque'', ''Strasbourg'', two cruisers, and five destroyers left that afternoon and arrived three days later. The squadron was quickly ordered to return to Brest just a few days later in response to the German landings in Norway on 9 April. The ''Force de Raid'' left Mers-el-Kébir that day and arrived in Brest on the 12th, with the intention that the ships would cover convoys to reinforce Allied forces fighting in Norway. But the threat of Italian intervention continued to weigh on the French command, which reversed the ships' orders and transferred them back to Mers-el Kebir on 24 April; ''Dunkerque'' and the rest of the group left that day and arrived on 27 April. They conducted training exercises in the western Mediterranean from 9 to 10 May but saw little activity for the next month. On 10 June, Italy declared war on France and Britain.

Two days later, ''Dunkerque'' and ''Strasbourg'' sortied to intercept reported German and Italian ships that were incorrectly reported to be in the area. The French had received faulty intelligence that had indicated that the Germans would attempt to force a group of battleships through the Strait of Gibraltar

The Strait of Gibraltar ( ar, مضيق جبل طارق, Maḍīq Jabal Ṭāriq; es, Estrecho de Gibraltar, Archaic: Pillars of Hercules), also known as the Straits of Gibraltar, is a narrow strait that connects the Atlantic Ocean to the Medi ...

to strengthen the Italian fleet. After the French fleet got underway, reconnaissance aircraft reported spotting an enemy fleet steaming toward Gibraltar. Supposing the aircraft to have spotted the Italian battle fleet steaming to join the Germans, the French increased speed to intercept them, only to realize that the aircraft had in fact located the French fleet. The fleet then returned to port, marking the end of ''Dunkerque''s last wartime operation. On 22 June, France surrendered to Germany following the Battle of France

The Battle of France (french: bataille de France) (10 May – 25 June 1940), also known as the Western Campaign ('), the French Campaign (german: Frankreichfeldzug, ) and the Fall of France, was the German invasion of France during the Second Wor ...

; during the truce negotiations, the French Navy proposed demilitarizing ''Dunkerque'' and several other warships in Toulon

Toulon (, , ; oc, label= Provençal, Tolon , , ) is a city on the French Riviera and a large port on the Mediterranean coast, with a major naval base. Located in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region, and the Provence province, Toulon is th ...

. Under the terms of the Armistice

An armistice is a formal agreement of warring parties to stop fighting. It is not necessarily the end of a war, as it may constitute only a cessation of hostilities while an attempt is made to negotiate a lasting peace. It is derived from the ...

, ''Dunkerque'' and ''Strasbourg'' would remain at Mers-el-Kébir.

Mers-el-Kébir

attack on Mers-el-Kébir

The Attack on Mers-el-Kébir (Battle of Mers-el-Kébir) on 3 July 1940, during the Second World War, was a British naval attack on neutral French Navy ships at the naval base at Mers El Kébir, near Oran, on the coast of French Algeria. The atta ...

on 3 July. The British, misinterpreting the terms of the armistice as providing the Germans with access to the French fleet, feared that the ships would be seized and pressed into service against them despite assurances from Darlan that if the Germans attempted to take the vessels, their crews would scuttle them. Prime Minister Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

then convinced the War Cabinet

A war cabinet is a committee formed by a government in a time of war to efficiently and effectively conduct that war. It is usually a subset of the full executive cabinet of ministers, although it is quite common for a war cabinet to have senio ...

that the fleet must be neutralized or forced to re-join the war on the side of Britain. The British Force H

Force H was a British naval formation during the Second World War. It was formed in 1940, to replace French naval power in the western Mediterranean removed by the French armistice with Nazi Germany. The force occupied an odd place within the ...

, commanded by Admiral James Somerville

Admiral of the Fleet Sir James Fownes Somerville, (17 July 1882 – 19 March 1949) was a Royal Navy officer. He served in the First World War as fleet wireless officer for the Mediterranean Fleet where he was involved in providing naval suppo ...

and centered on HMS ''Hood'' and the battleships , and , arrived off Mers-el-Kébir to coerce the French battleship squadron to join the British cause or scuttle their ships. The French Navy refused, as complying with the demand would have violated the armistice signed with Germany. To ensure the ships would not fall into Axis hands, the British warships opened fire at 17:55. ''Dunkerque'' was tied alongside the mole with her stern facing the sea, so she could not return fire.

''Dunkerque''s crew loosed the chains and started to get the ship underway just as the British opened fire; the ship was engaged by HMS ''Hood''. The French gunners responded quickly and ''Dunkerque'' fired several salvos at ''Hood'' before being hit by four shells in quick succession. The first was deflected on the upper main battery turret roof above the right-most gun, though it shoved in the armor plate and ignited propellant charges in the right turret half that asphyxiated all the men in that half; the left half remained operational. The shell itself was deflected off the turret face and failed to explode when it landed around away. Fragments of armor plate that had been dislodged by the impact destroyed the run-out cylinder for the right gun, disabling it. The second shell passed through the unarmored stern, penetrating the armor deck and exiting the hull without exploding. Though it did little damage, the shell did cut the control line for the rudder

A rudder is a primary control surface used to steer a ship, boat, submarine, hovercraft, aircraft, or other vehicle that moves through a fluid medium (generally air or water). On an aircraft the rudder is used primarily to counter adve ...

, forcing the ship to use manual control, which hampered the crew's ability to steer the ship as they attempted to get underway.

The third shell hit the ship shortly after 18:00; this projectile struck the upper edge of the belt on the starboard side; since the belt had only been designed to defeat German shells, the much more powerful British shell easily perforated it. The shell then passed through the handling room for the starboard secondary turret No. III, igniting propellant charges and detonating a pair of 130 mm shells as it did so. The 15 in round then penetrated an internal bulkhead and exploded in the medical storage room. The blast caused extensive internal damage, allowing smoke from the ammunition fire to enter the machinery spaces, which had to be abandoned, though debris from the explosion had jammed the armored doors shut. Only a dozen men were able to escape using a ladder at the forward end of the room. The fourth shell struck the belt aft of the third hit and at the waterline. It also defeated the belt and the torpedo bulkhead and then exploded in boiler room 2, causing extensive damage to the propulsion machinery. ''Dunkerque'' rapidly lost speed and then all electrical power; unable to get underway or further resist the British ships, ''Dunkerque'' was beached on the other side of Mers-el-Kébir

The third shell hit the ship shortly after 18:00; this projectile struck the upper edge of the belt on the starboard side; since the belt had only been designed to defeat German shells, the much more powerful British shell easily perforated it. The shell then passed through the handling room for the starboard secondary turret No. III, igniting propellant charges and detonating a pair of 130 mm shells as it did so. The 15 in round then penetrated an internal bulkhead and exploded in the medical storage room. The blast caused extensive internal damage, allowing smoke from the ammunition fire to enter the machinery spaces, which had to be abandoned, though debris from the explosion had jammed the armored doors shut. Only a dozen men were able to escape using a ladder at the forward end of the room. The fourth shell struck the belt aft of the third hit and at the waterline. It also defeated the belt and the torpedo bulkhead and then exploded in boiler room 2, causing extensive damage to the propulsion machinery. ''Dunkerque'' rapidly lost speed and then all electrical power; unable to get underway or further resist the British ships, ''Dunkerque'' was beached on the other side of Mers-el-Kébir roadstead

A roadstead (or ''roads'' – the earlier form) is a body of water sheltered from rip currents, spring tides, or ocean swell where ships can lie reasonably safely at anchor without dragging or snatching.United States Army technical manual, TM 5 ...

to prevent her from being sunk.

The British fire ceased after less than twenty minutes, which limited the damage inflicted; Somerville hoped to minimize the damage done to Franco-British relations. Work on the ship began almost immediately; at 20:00, Gensoul ordered the crew to recover the dead and wounded while damage control teams stabilized the ship. Those not engaged in either work—some 800 men—were sent ashore. Half an hour later, he radioed Somerville that the ship had been largely evacuated. By the next morning, the fires had been suppressed and work to plate over the shell holes in the hull had begun. Wounded crewmen had been evacuated to a local hospital. Gensoul expected that the ship would be ready to sail for Toulon for permanent repairs within a few days and informed his superior, Admiral Jean-Pierre Esteva (''Amiral Sud'', the commander of naval forces in North Africa) as much. Esteva in turn issued a statement to that effect to the press in Algeria, which had the unintended effect of informing the British that ''Dunkerque'' had not been disabled permanently. Churchill ordered Somerville to return and destroy the ship; Somerville, hoping to avoid civilian casualties now that the ship was beached directly in front of the town of Saint André, secured permission to attack using only torpedo bomber

A torpedo bomber is a military aircraft designed primarily to attack ships with aerial torpedoes. Torpedo bombers came into existence just before the First World War almost as soon as aircraft were built that were capable of carrying the weight ...

s.

The second attack took place on 6 July. A flight of twelve Fairey Swordfish

The Fairey Swordfish is a biplane torpedo bomber, designed by the Fairey Aviation Company. Originating in the early 1930s, the Swordfish, nicknamed "Stringbag", was principally operated by the Fleet Air Arm of the Royal Navy. It was also us ...

torpedo bombers, armed with torpedoes modified for use in shallow water, were launched from the carrier in three waves of six, three, and three aircraft. They received an escort of three Blackburn Skua

The Blackburn B-24 Skua was a carrier-based low-wing, two-seater, single- radial engine aircraft by the British aviation company Blackburn Aircraft. It was the first Royal Navy carrier-borne all-metal cantilever monoplane aircraft, as well as t ...

fighters

Fighter(s) or The Fighter(s) may refer to:

Combat and warfare

* Combatant, an individual legally entitled to engage in hostilities during an international armed conflict

* Fighter aircraft, a warplane designed to destroy or damage enemy warplan ...

. The French had failed to erect torpedo nets around the ship, and Gensoul, who had hoped to reinforce the idea that the ship had been evacuated, ordered that her anti-aircraft guns not be manned. Three patrol boat

A patrol boat (also referred to as a patrol craft, patrol ship, or patrol vessel) is a relatively small naval vessel generally designed for coastal defence, border security, or law enforcement. There are many designs for patrol boats, and the ...

s were moored alongside to evacuate the remaining crew aboard in the event of another attack, and these vessels were loaded with depth charge

A depth charge is an anti-submarine warfare (ASW) weapon. It is intended to destroy a submarine by being dropped into the water nearby and detonating, subjecting the target to a powerful and destructive hydraulic shock. Most depth charges use h ...

s. The first wave scored a hit on the patrol boat ''Terre-Neuve'', and though it failed to explode, the hole it punched in her hull caused her to sink in the shallow water. Another torpedo hit the wreck in the second wave and exploded, leading to a secondary explosion of fourteen of her depth charges, which was the equivalent of of TNT, equal to eight Swordfish torpedoes. The explosion caused extensive damage to ''Dunkerque''s bow and likely would have resulted in a magazine detonation had her captain not ordered the magazines be flooded as soon as the Swordfishes appeared. The blast killed another 30, bringing the total killed in both attacks to 210.

''Dunkerque'' had been badly damaged in the attack, far more so than the 3 July shelling; some of water had flooded the ship through a hole opened in the hull, and a length of her hull, double bottom, and torpedo bulkhead had been deformed by the blast. The forward armor belt was also distorted and her armored decks had been pushed up. A survey of the damage was conducted on 11 July, but the scale of the damage was beyond what the local shipyard could repair, as it lacked a drydock of sufficient size. Engineers from Toulon were sent to assist the repair work, which began with the fabrication of a sheet of steel that was bolted over the hull from 19 to 23 August and then sealed with of concrete between 31 August and 11 September. The hull was then pumped dry and re-floated on 27 September, thereafter being towed to a quay in Saint André for further repairs. At this time, torpedo nets were set up around the ship and her anti-aircraft guns were manned. One of the workers accidentally started a serious fire with a welding torch

Principle of burn cutting

Oxy-fuel welding (commonly called oxyacetylene welding, oxy welding, or gas welding in the United States) and oxy-fuel cutting are processes that use fuel gases (or liquid fuels such as gasoline or petrol, diesel, ...

on 5 December.

Work continued well into 1941, and in April she conducted stationary trials with her machinery. Her crew returned on 19 May and she was ready to return to Toulon by July, but heavy fighting during the Mediterranean Campaign forced the French to wait to avoid being caught in the cross fire. On 25 January 1942 another fire broke out from a short circuit

A short circuit (sometimes abbreviated to short or s/c) is an electrical circuit that allows a current to travel along an unintended path with no or very low electrical impedance. This results in an excessive current flowing through the circu ...

. ''Dunkerque'' was finally ready to cross the Mediterranean on 19 February; she got underway at 04:00, escorted by the destroyers , , , , and . Some 65 fighters, bombers, and torpedo bombers covered the ships while they made the crossing. ''Dunkerque'' reached Toulon at 23:00 on 20 February; her crew was reduced to comply with the terms of the armistice on 1 March, and on 22 June, she entered the large Vauban dock for permanent repairs.

Scuttling at Toulon

Wehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the ''Heer'' (army), the '' Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmacht''" replaced the previo ...

occupied the Zone libre

The ''zone libre'' (, ''free zone'') was a partition of the French metropolitan territory during World War II, established at the Second Armistice at Compiègne on 22 June 1940. It lay to the south of the demarcation line and was administered b ...

in retaliation for the successful Allied landings in North Africa, the Germans attempted to seize the French warships remaining under Vichy

Vichy (, ; ; oc, Vichèi, link=no, ) is a city in the Allier department in the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region of central France, in the historic province of Bourbonnais.

It is a spa and resort town and in World War II was the capital of ...

control on 27 November. To prevent them from seizing the ships, their crews scuttled the fleet in Toulon, including ''Dunkerque'', which still lay incomplete in the Vauban drydock. Demolition charges were placed on the ship and she was set on fire. Her commanding officer, ''Capitaine de vaisseau

Captain is the name most often given in English-speaking navies to the rank corresponding to command of the largest ships. The rank is equal to the army rank of colonel and air force rank of group captain.

Equivalent ranks worldwide include ...

'' (Captain) Amiel, initially refused to sink his ship without written orders, but was finally convinced to do so by the commanding officer of the nearby light cruiser . Since she was still in the dry dock, the locks had to be opened to flood the ship, which would have taken two to three hours. Since she was in the far side of the dockyard, it took the Germans over an hour to reach the vessel, and in the confusion, they made no attempt to close the locks.

Italy received control of most of the wrecks, and they decided to repair as many ships as possible for service with the Italian fleet, but to

Italy received control of most of the wrecks, and they decided to repair as many ships as possible for service with the Italian fleet, but to scrap

Scrap consists of recyclable materials, usually metals, left over from product manufacturing and consumption, such as parts of vehicles, building supplies, and surplus materials. Unlike waste, scrap has monetary value, especially recovered m ...

those that were too badly damaged to quickly return to service. The Italians deemed ''Dunkerque'' to be a total loss, and so began to dismantle ''in situ

''In situ'' (; often not italicized in English) is a Latin phrase that translates literally to "on site" or "in position." It can mean "locally", "on site", "on the premises", or "in place" to describe where an event takes place and is used in ...

''. As part of this process, the ship was deliberately damaged to prevent the French from being able to repair her if she was recaptured; the Italians cut down the main battery guns to render them unusable. The partially scrapped hulk was in turn seized by the Germans when Italy surrendered to the Allies in September 1943. In 1944, the Germans removed the ship's bow to float her out of the drydock to free up the dock and continue the scrapping process. While in Axis possession, she was bombed several times by Allied aircraft. The hulk was condemned on 15 September 1955 and renamed ''Q56''. Her remains, which amounted to not more than , were sold for final demolition on 30 September 1958 for 226,117,000 francs.

Footnotes

Notes

Citations

References

* * * * * * * *External links

Maritimequest Dunkerque Photo Gallery

{{DEFAULTSORT:Dunkerque Dunkerque-class battleships World War II battleships of France Maritime incidents in July 1940 Shipwrecks of France World War II shipwrecks in the Mediterranean Sea 1935 ships World War II warships scuttled at Toulon Maritime incidents in November 1942 Scuttled vessels