French battleship Charles Martel on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Charles Martel'' was a

In 1889, the British

In 1889, the British

In February and March 1899, the squadron visited French Mediterranean ports and

In February and March 1899, the squadron visited French Mediterranean ports and

On 10 May Marquis was transferred to a new job and ''Charles Martel'' was transferred to the of the , along with the battleships ''Brennus'', ''Carnot'', and ''Hoche'' and the

On 10 May Marquis was transferred to a new job and ''Charles Martel'' was transferred to the of the , along with the battleships ''Brennus'', ''Carnot'', and ''Hoche'' and the

pre-dreadnought

Pre-dreadnought battleships were sea-going battleships built between the mid- to late- 1880s and 1905, before the launch of in 1906. The pre-dreadnought ships replaced the ironclad battleships of the 1870s and 1880s. Built from steel, protec ...

battleship of the French Navy

The French Navy (french: Marine nationale, lit=National Navy), informally , is the maritime arm of the French Armed Forces and one of the five military service branches of France. It is among the largest and most powerful naval forces in t ...

built in the 1890s. Completed in 1897, she was a member of a group of five broadly similar battleships ordered as part of the French response to a major British naval construction program. The five ships were built to the same basic design parameters, though the individual architects were allowed to deviate from each other in other details. Like her half-sisters

A sibling is a relative that shares at least one parent with the subject. A male sibling is a brother and a female sibling is a sister. A person with no siblings is an only child.

While some circumstances can cause siblings to be raised separat ...

—, , , and —she was armed with a main battery

A main battery is the primary weapon or group of weapons around which a warship is designed. As such, a main battery was historically a gun or group of guns, as in the broadsides of cannon on a ship of the line. Later, this came to be turreted ...

of two guns and two guns. The ship had a top speed of .

''Charles Martel'' spent her active career in the Escadre de la Méditerranée (Mediterranean Squadron) of the French fleet, first in the active squadron, and later in the Escadre de réserve ( Reserve Squadron). She regularly participated in fleet maneuvers, and in the 1901 exercises, the submarine hit her with a training torpedo

A modern torpedo is an underwater ranged weapon launched above or below the water surface, self-propelled towards a target, and with an explosive warhead designed to detonate either on contact with or in proximity to the target. Historically, s ...

. ''Charles Martel'' spent just five years in the active squadron, having been surpassed by more modern battleships during a period of rapid developments in naval technology. She spent the years 1902–1914 mostly in reserve, and the navy decommissioned the vessel in early 1914, hulking her and converting her into a barracks ship

A barracks ship or barracks barge or berthing barge, or in civilian use accommodation vessel or accommodation ship, is a ship or a non-self-propelled barge containing a superstructure of a type suitable for use as a temporary barracks for s ...

. After the outbreak of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

in August, her guns were removed for use on the front and she briefly served as a prison ship

A prison ship, often more accurately described as a prison hulk, is a current or former seagoing vessel that has been modified to become a place of substantive detention for convicts, prisoners of war or civilian internees. While many nat ...

. ''Charles Martel'' was condemned in 1919 and was sold for scrap the following year.

Design

In 1889, the British

In 1889, the British Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against ...

passed the Naval Defence Act that resulted in the construction of the eight s; this major expansion of naval power led the French government to pass its reply, the ''Statut Naval'' (Naval Law) of 1890. The law called for a total of twenty-four "''cuirasses d'escadre''" (squadron battleships) and a host of other vessels, including coastal defense battleships, cruisers, and torpedo boat

A torpedo boat is a relatively small and fast naval ship designed to carry torpedoes into battle. The first designs were steam-powered craft dedicated to ramming enemy ships with explosive spar torpedoes. Later evolutions launched variants of ...

s. The first stage of the program was to be a group of four squadron battleships that were built to different designs but met the same basic characteristics, including armor, armament, and displacement

Displacement may refer to:

Physical sciences

Mathematics and Physics

* Displacement (geometry), is the difference between the final and initial position of a point trajectory (for instance, the center of mass of a moving object). The actual path ...

. The naval high command issued the basic requirements on 24 December 1889; displacement would not exceed , the primary armament was to consist of and guns, the belt armor

Belt armor is a layer of heavy metal armor plated onto or within the outer hulls of warships, typically on battleships, battlecruisers and cruisers, and aircraft carriers.

The belt armor is designed to prevent projectiles from penetrating to ...

should be , and the ships should maintain a top speed of . The secondary battery was to be either or caliber, with as many guns fitted as space would allow.

The basic design for the ships was based on the previous battleship , but instead of mounting the main battery all on the centerline, the ships used the lozenge arrangement of the earlier , which moved two of the main battery guns to single turrets on the wings

A wing is a type of fin that produces lift while moving through air or some other fluid. Accordingly, wings have streamlined cross-sections that are subject to aerodynamic forces and act as airfoils. A wing's aerodynamic efficiency is expre ...

. Five naval architects submitted designs to the high command; the design that became ''Charles Martel'' was prepared by Charles Ernest Huin, who had also designed the ironclad battleship . Political considerations, namely parliamentary objections to increases in naval expenditures, led the designers to limit displacement to around . Huin submitted his finalized proposal in line with these considerations on 12 August 1890, and it was accepted and ordered on 10 September. Though the program called for four ships to be built in the first year, five were ultimately ordered: ''Charles Martel'', , , , and .

An earlier vessel, also named ''Charles Martel'', had been laid down

Laying the keel or laying down is the formal recognition of the start of a ship's construction. It is often marked with a ceremony attended by dignitaries from the shipbuilding company and the ultimate owners of the ship.

Keel laying is one o ...

in 1884 and cancelled under the tenure of Admiral Théophile Aube

Hyacinthe Laurent Théophile Aube () (22 November 1826, Toulon, Var – 31 December 1890, Toulon) was a French admiral, who held several important governmental positions during the Third Republic.

Aube served as Governor of Martinique

M ...

. The vessel, along with a sister ship named ''Brennus'', was a modified version of the ironclad battleships. After Aube's retirement in 1887, the plans for the ships were entirely redesigned, though the later pair of ships are sometimes conflated with the earlier, cancelled designs. This may be due to the fact that both of the ships named ''Brennus'' were built in the same shipyard, and material assembled for the first vessel was used in the construction of the second. The two pairs of ships were, nevertheless, distinct vessels.

The new ''Charles Martel'' and her half-sisters were disappointments in service; they generally suffered from stability problems, and Louis-Émile Bertin

Louis-Émile Bertin (23 March 1840 – 22 October 1924) was a French naval engineer, one of the foremost of his time, and a proponent of the " Jeune École" philosophy of using light, but powerfully armed warships instead of large battleships.

...

, the Director of Naval Construction in the late 1890s, referred to the ships as (prone to ''capsizing''). All five of the vessels compared poorly to their British counterparts, particularly their contemporaries of the . The ships suffered from a lack of uniformity of equipment, which made them hard to maintain in service, and their mixed gun batteries comprising several calibers made gunnery in combat conditions difficult, since shell splashes were hard to differentiate. Many of the problems that plagued the ships in service, particularly their stability and seakeeping

Seakeeping ability or seaworthiness is a measure of how well-suited a watercraft is to conditions when underway. A ship or boat which has good seakeeping ability is said to be very seaworthy and is able to operate effectively even in high sea stat ...

, were a result of the limitation on their displacement.

General characteristics and machinery

''Charles Martel'' was long between perpendiculars andlong overall

__NOTOC__

Length overall (LOA, o/a, o.a. or oa) is the maximum length of a vessel's hull measured parallel to the waterline. This length is important while docking the ship. It is the most commonly used way of expressing the size of a ship, an ...

. The ship had a beam of , a forward draft

Draft, The Draft, or Draught may refer to:

Watercraft dimensions

* Draft (hull), the distance from waterline to keel of a vessel

* Draft (sail), degree of curvature in a sail

* Air draft, distance from waterline to the highest point on a vesse ...

of and a draft of at the stern. She displaced at normal load and at full load

The displacement or displacement tonnage of a ship is its weight. As the term indicates, it is measured indirectly, using Archimedes' principle, by first calculating the volume of water displaced by the ship, then converting that value into wei ...

. ''Charles Martel''s hull was subdivided by 13 transverse bulkheads into 14 watertight compartment

A compartment is a portion of the space within a ship defined vertically between decks and horizontally between bulkheads. It is analogous to a room within a building, and may provide watertight subdivision of the ship's hull important in retaini ...

s and she was fitted with a ram

Ram, ram, or RAM may refer to:

Animals

* A male sheep

* Ram cichlid, a freshwater tropical fish

People

* Ram (given name)

* Ram (surname)

* Ram (director) (Ramsubramaniam), an Indian Tamil film director

* RAM (musician) (born 1974), Dutch

* ...

bow. Her forecastle

The forecastle ( ; contracted as fo'c'sle or fo'c's'le) is the upper deck of a sailing ship forward of the foremast, or, historically, the forward part of a ship with the sailors' living quarters. Related to the latter meaning is the phrase " be ...

gave her a high freeboard

In sailing and boating, a vessel's freeboard

is the distance from the waterline to the upper deck level, measured at the lowest point of sheer where water can enter the boat or ship. In commercial vessels, the latter criterion measured relativ ...

forward, but her quarterdeck was cut down to the main deck level aft. Her hull was given a marked tumblehome

Tumblehome is a term describing a hull which grows narrower above the waterline than its beam. The opposite of tumblehome is flare.

A small amount of tumblehome is normal in many naval architecture designs in order to allow any small projecti ...

to give the 27 cm guns wide fields of fire. Like earlier Huin designs, ''Charles Martel'' had a very tall superstructure; she was equipped with two heavy military masts, with a tall flying deck between them. In service, the tall superstructure made her top-heavy, though her high freeboard made her very seaworthy

Seakeeping ability or seaworthiness is a measure of how well-suited a watercraft is to conditions when underway. A ship or boat which has good seakeeping ability is said to be very seaworthy and is able to operate effectively even in high sea stat ...

. She normally had a crew of 651 officers and enlisted men, which increased to 751 when serving as a flagship.

''Charles Martel'' had two vertical, three-cylinder triple-expansion steam engine

A compound steam engine unit is a type of steam engine where steam is expanded in two or more stages.

A typical arrangement for a compound engine is that the steam is first expanded in a high-pressure ''(HP)'' cylinder, then having given up ...

s manufactured by Schneider-Creusot

Schneider et Cie, also known as Schneider-Creusot for its birthplace in the French town of Le Creusot, was a historic French iron and steel-mill company which became a major arms manufacturer. In the 1960s, it was taken over by the Belgian Empain ...

; each engine drove a single three-bladed, screw using steam supplied by twenty-four Lagrafel d'Allest water-tube boiler

A high pressure watertube boiler (also spelled water-tube and water tube) is a type of boiler in which water circulates in tubes heated externally by the fire. Fuel is burned inside the furnace, creating hot gas which boils water in the steam-gen ...

s at a maximum pressure of . The boilers were divided into four boiler rooms and were ducted into two funnels. Her engines were rated at , which was intended to give the ship a speed of normally and up to using forced draft The difference between atmospheric pressure and the pressure existing in the furnace or flue gas passage of a boiler is termed as draft. Draft can also be referred to as the difference in pressure in the combustion chamber area which results in the ...

. During her sea trials

A sea trial is the testing phase of a watercraft (including boats, ships, and submarines). It is also referred to as a "shakedown cruise" by many naval personnel. It is usually the last phase of construction and takes place on open water, and i ...

on 5 May 1897, ''Charles Martel'' reached a speed of from . The ship could carry a maximum of of coal, which gave her a range of at a speed of . Her 83-volt

The volt (symbol: V) is the unit of electric potential, electric potential difference (voltage), and electromotive force in the International System of Units (SI). It is named after the Italian physicist Alessandro Volta (1745–1827).

Defin ...

electrical power was provided by four 600- ampere dynamo

"Dynamo Electric Machine" (end view, partly section, )

A dynamo is an electrical generator that creates direct current using a commutator. Dynamos were the first electrical generators capable of delivering power for industry, and the foundati ...

s.

Armament

''Charles Martel''s main armament consisted of two 45- caliber Canon de 305 mm Modèle 1887 guns in two single-gun turrets, one each fore and aft of the superstructure. The hydraulically worked turrets had a range of elevation of -5° to +15°. They firedcast-iron

Cast iron is a class of iron–carbon alloys with a carbon content more than 2%. Its usefulness derives from its relatively low melting temperature. The alloy constituents affect its color when fractured: white cast iron has carbide impuriti ...

projectiles at the rate of one round

Round or rounds may refer to:

Mathematics and science

* The contour of a closed curve or surface with no sharp corners, such as an ellipse, circle, rounded rectangle, cant, or sphere

* Rounding, the shortening of a number to reduce the number ...

per minute. They had a muzzle velocity of which gave a range of at maximum elevation.

The ship's intermediate armament consisted of a pair of 45-caliber Canon de Modèle 1887 guns in single-gun wing turrets amidships

This glossary of nautical terms is an alphabetical listing of terms and expressions connected with ships, shipping, seamanship and navigation on water (mostly though not necessarily on the sea). Some remain current, while many date from the 17th ...

on each side and sponson

Sponsons are projections extending from the sides of land vehicles, aircraft or watercraft to provide protection, stability, storage locations, mounting points for weapons or other devices, or equipment housing.

Watercraft

On watercraft, a spon ...

ed out over the tumblehome of the ship's sides. Their turrets had the same range of elevation as the main battery. The guns had the same rate of fire and muzzle velocity as the larger guns, but their cast-iron shells only weighed and their maximum range was slightly less at .

Her secondary armament

Secondary armament is a term used to refer to smaller, faster-firing weapons that were typically effective at a shorter range than the main (heavy) weapons on military systems, including battleship- and cruiser-type warships, tanks/armored ...

consisted of eight 45-caliber Canon de Modèle 1888-91 guns which were mounted in single-gun turrets at the corners of the superstructure. The turrets had an elevation range of from -5° to +15°. The guns could fire their shells at a rate of fire of four rounds per minute. They had a muzzle velocity of and a range of .

Defense against torpedo boats was provided by six quick-firing (QF) 50-caliber Canon de Modèle 1891 guns, a dozen 40-caliber QF Modèle 1885 guns, and five 20-caliber QF revolving cannon, all in unprotected single mounts on the superstructure and in platforms on the military masts. The 65 mm guns had a rate of fire of eight rounds per minute and a range of while 47 mm guns could fire nine to fifteen rounds per minute to a range of . The five-barrel 37 mm revolving guns had a rate of fire of twenty to twenty-five rounds per minute and a range of . While conducting her sea trials in 1896, two of ''Charles Martel''s 65 mm and all of her 37 mm guns were replaced by four additional 47 mm guns.

Her armament suite was rounded out by four torpedo tube

A torpedo tube is a cylindrical device for launching torpedoes.

There are two main types of torpedo tube: underwater tubes fitted to submarines and some surface ships, and deck-mounted units (also referred to as torpedo launchers) installed aboa ...

s, two of which were submerged in the ship's hull, one on each broadside, with the other two on single rotating mounts abaft

This glossary of nautical terms is an alphabetical listing of terms and expressions connected with ships, shipping, seamanship and navigation on water (mostly though not necessarily on the sea). Some remain current, while many date from the 17th t ...

the forward 138 mm turrets; each mount could traverse an arc from 30° to 110° off the centerline. ''Charles Martel'' was initially equipped with Modèle 1892 torpedoes that had a warhead

A warhead is the forward section of a device that contains the explosive agent or toxic (biological, chemical, or nuclear) material that is delivered by a missile, rocket, torpedo, or bomb.

Classification

Types of warheads include:

* Expl ...

and a range of at a speed of .

Armor

''Charles Martel''s armor weighed , 38.5% of the ship's displacement, and was constructed from a mix ofnickel steel

Nickel is a chemical element with symbol Ni and atomic number 28. It is a silvery-white lustrous metal with a slight golden tinge. Nickel is a hard and ductile transition metal. Pure nickel is chemically reactive but large pieces are slow to r ...

and compound armor plates that were manufactured by Schneider-Creusot. The waterline belt extended the full length of the ship and it had an average height of , although it reduced to aft. The belt had a maximum thickness of 450 mm amidships where it protected the ammunition magazines

A magazine is a periodical publication, generally published on a regular schedule (often weekly or monthly), containing a variety of content. They are generally financed by advertising, purchase price, prepaid subscriptions, or by a combination ...

and propulsion machinery spaces and reduced to forward and aft. To save weight, the belt was tapered to a thickness at its bottom edge of amidships and at the ends of the ship. Above the belt was a thick strake

On a vessel's hull, a strake is a longitudinal course of planking or plating which runs from the boat's stempost (at the bows) to the sternpost or transom (at the rear). The garboard strakes are the two immediately adjacent to the keel on ea ...

of armor that created a highly-subdivided cofferdam

A cofferdam is an enclosure built within a body of water to allow the enclosed area to be pumped out. This pumping creates a dry working environment so that the work can be carried out safely. Cofferdams are commonly used for construction or re ...

to reduce the risk of flooding from battle damage. Coal storage bunkers were placed behind the upper side armor to increase its strength.

The faces and sides of the main and intermediate turrets were protected by armor plates in thickness and they had roofs. Their barbette

Barbettes are several types of gun emplacement in terrestrial fortifications or on naval ships.

In recent naval usage, a barbette is a protective circular armour support for a heavy gun turret. This evolved from earlier forms of gun protectio ...

s had of nickel-steel armor. The secondary turrets had 100 mm sides and roofs. The conning tower had walls thick and its communications tube was protected by of armor. The curved armored deck was 70 mm on the flat and 100 mm on its slope.

Service history

Active career

''Charles Martel'' was laid down on 1 August 1891 by theArsenal de Brest

The Brest Arsenal (French - ''arsenal de Brest'') is a collection of naval and military buildings located on the banks of the river Penfeld, in Brest, France. It is located at .

Timeline

*1631-1635 Beginning of the foundations of the port infr ...

and launched on 29 August 1893. After completing fitting-out

Fitting out, or outfitting, is the process in shipbuilding that follows the float-out/launching of a vessel and precedes sea trials. It is the period when all the remaining construction of the ship is completed and readied for delivery to her o ...

work, she was commissioned for her trials on 10 January 1896. In October they were interrupted so that the battleship could participate in a naval review in Cherbourg with President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

* President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ...

Félix Faure

Félix François Faure (; 30 January 1841 – 16 February 1899) was the President of France from 1895 until his death in 1899. A native of Paris, he worked as a tanner in his younger years. Faure became a member of the Chamber of Deputies for ...

and Tsar

Tsar ( or ), also spelled ''czar'', ''tzar'', or ''csar'', is a title used by East and South Slavic monarchs. The term is derived from the Latin word ''caesar'', which was intended to mean "emperor" in the European medieval sense of the ter ...

Nicholas II. While conducting torpedo trials on 21 December, ''Charles Martel'' struck an uncharted rock that bent a propeller blade and slightly damaged the hull. Repairs were completed on 1 February 1897 and she was fully commissioned into the French Navy on 20 February. She was delayed in completing her sea trial

A sea trial is the testing phase of a watercraft (including boats, ships, and submarines). It is also referred to as a " shakedown cruise" by many naval personnel. It is usually the last phase of construction and takes place on open water, and ...

s, as her boiler tubes had to be replaced with a safer, weld-less design, following an accident aboard ''Jauréguiberry'' with the same type of tubes. Following her commissioning for service, she was assigned to the ''Escadre de la Méditerranée''. While working up on 5 March, her rudder

A rudder is a primary control surface used to steer a ship, boat, submarine, hovercraft, aircraft, or other vehicle that moves through a fluid medium (generally air or water). On an aircraft the rudder is used primarily to counter adve ...

servomotor

A servomotor (or servo motor) is a rotary actuator or linear actuator that allows for precise control of angular or linear position, velocity and acceleration. It consists of a suitable motor coupled to a sensor for position feedback. It also ...

briefly declutched and the ship drifted onto a rock; damage was minimal and she began her voyage to Toulon

Toulon (, , ; oc, label= Provençal, Tolon , , ) is a city on the French Riviera and a large port on the Mediterranean coast, with a major naval base. Located in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region, and the Provence province, Toulon is th ...

three days later. On 6 August she became the flagship of (Rear Admiral) Paul Dieulouard and took part in fleet maneuvers off Golfe-Juan

Golfe-Juan (; oc, Lo Gorg Joan, Lo Golfe Joan) is a seaside resort on France's Côte d'Azur. The distinct local character of Golfe-Juan is indicated by the existence of a demonym, "Golfe-Juanais", which is applied to its inhabitants.

Overview

...

and Les Salins d'Hyères the following month. Gunnery training revealed problems with some of the guns failing to return to battery that were rectified in October–November.

During a gunnery exercise on 29 March 1898, ''Charles Martel'', together with her half-sisters ''Carnot'', ''Jauréguiberry'', and the older battleships ''Brennus'' and , sank the aviso

An ''aviso'' was originally a kind of dispatch boat or "advice boat", carrying orders before the development of effective remote communication.

The term, derived from the Portuguese and Spanish word for "advice", "notice" or "warning", an ...

. Faure came aboard ''Charles Martel'' to observe a training exercise on 14–16 April and the ship visited Corsica between 21 and 31 May. She participated in the annual fleet maneuvers beginning on 8 July and made port visits in French North Africa

French North Africa (french: Afrique du Nord française, sometimes abbreviated to ANF) is the term often applied to the territories controlled by France in the North African Maghreb during the colonial era, namely Algeria, Morocco and Tunisia. I ...

before returning to Toulon on 30 July. The ship was assigned to the (Second Battleship Division) of the ''Escadre de la Méditerranée'' in mid-September and Germain Roustan hoisted his flag aboard, replacing Dieulouard, on 25 September. As tensions rose during the Fashoda Incident

The Fashoda Incident, also known as the Fashoda Crisis (French: ''Crise de Fachoda''), was an international incident and the climax of imperialist territorial disputes between Britain and France in East Africa, occurring in 1898. A French exped ...

with Great Britain, the fleet mobilized on 18 October and sortied to Les Salins d'Hyères. It stood down on 5 November and ''Charles Martel'' was docked for maintenance from 11 to 24 November.

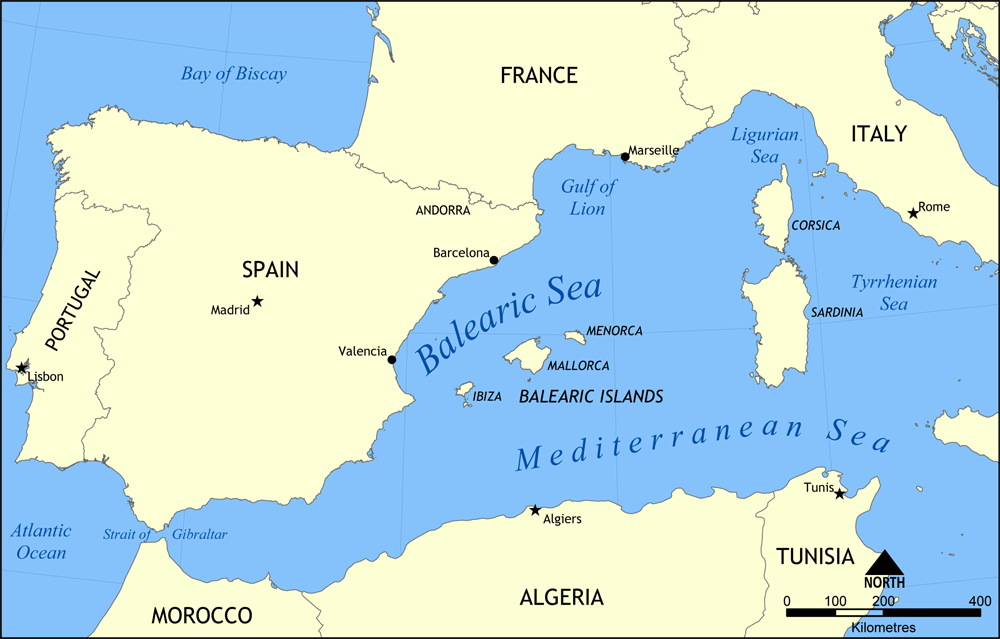

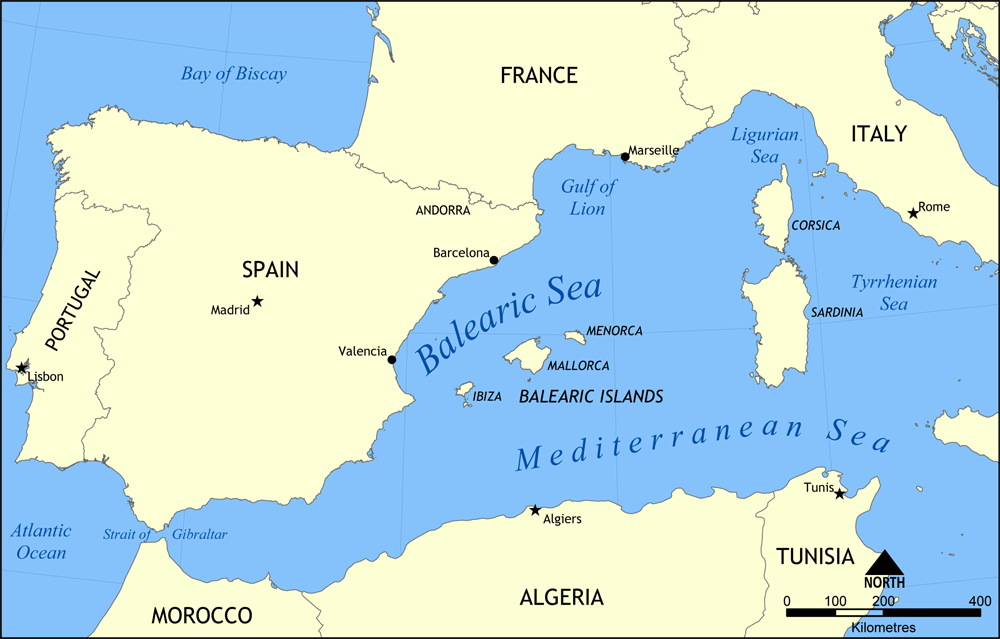

In February and March 1899, the squadron visited French Mediterranean ports and

In February and March 1899, the squadron visited French Mediterranean ports and Barcelona

Barcelona ( , , ) is a city on the coast of northeastern Spain. It is the capital and largest city of the autonomous community of Catalonia, as well as the second most populous municipality of Spain. With a population of 1.6 million within ci ...

, Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

. After repairs in Toulon in September, the ship joined the squadron in a cruise in the Eastern Mediterranean that lasted from 11 October to 21 December. She was docked for maintenance in January 1900 and then joined the battleships ''Brennus'', , , ''Bouvet'', and ''Jauréguiberry'' and four protected cruiser

Protected cruisers, a type of naval cruiser of the late-19th century, gained their description because an armoured deck offered protection for vital machine-spaces from fragments caused by shells exploding above them. Protected cruisers re ...

s for maneuvers off Golfe-Juan, including night-firing training on 6 March. Over the course of April, the ships visited numerous French ports along the Mediterranean coast, and on 31 May the fleet steamed to Corsica for a visit that lasted until 8 June. During the fleet maneuvers held that June, ''Charles Martel'' led Group II, which included four cruisers and a pair of destroyers, under Roustan's command. The exercises included a blockade of Group III's battleships by Group II. The ''Escadre de la Méditerranée'' then rendezvoused with the (Northern Squadron) off the coast of Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, República Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of ...

before proceeding to Quiberon Bay

Quiberon Bay (french: Baie de Quiberon) is an area of sheltered water on the south coast of Brittany. The bay is in the Morbihan département.

Geography

The bay is roughly triangular in shape, open to the south with the Gulf of Morbihan to t ...

for joint maneuvers in July. The maneuvers concluded with a naval review

A fleet review or naval review is an event where a gathering of ships from a particular navy is paraded and reviewed by an incumbent head of state and/or other official civilian and military dignitaries. A number of national navies continue to ...

in Cherbourg on 19 July for President Émile Loubet

Émile François Loubet (; 30 December 183820 December 1929) was the 45th Prime Minister of France from February to December 1892 and later President of France from 1899 to 1906.

Trained in law, he became mayor of Montélimar, where he was not ...

. On 1 August, the fleet departed for Toulon, arriving on 14 August. On 26 September, Charles Aubry de la Noé relived Roustan as the commander of the .

The year 1901 passed uneventfully for ''Charles Martel'', except for the fleet maneuvers conducted that year. During the June exercises, ''Charles Martel'' was hit by a training torpedo fired by the submarine , which was ruled against the rules, and her light guns sank the torpedo boat during target practice. The sailed on 22 August to welcome Nicholas II and his wife, and arrived at Dunkirk, having rendezvoused with the ''lang, fr, Escadre du Nord'' on 31 August at Cherbourg en route. On 15 October Aubry de la Noé was relieved by René-Julien Marquis. ''Charles Martel'' was docked for maintenance at the end of the month and had a radio telegraph

Wireless telegraphy or radiotelegraphy is transmission of text messages by radio waves, analogous to electrical telegraphy using electrical cable, cables. Before about 1910, the term ''wireless telegraphy'' was also used for other experimental t ...

installed. In early 1902, the ship made the usual visits to French Mediterranean ports.

Reserve fleet

On 10 May Marquis was transferred to a new job and ''Charles Martel'' was transferred to the of the , along with the battleships ''Brennus'', ''Carnot'', and ''Hoche'' and the

On 10 May Marquis was transferred to a new job and ''Charles Martel'' was transferred to the of the , along with the battleships ''Brennus'', ''Carnot'', and ''Hoche'' and the armored cruiser

The armored cruiser was a type of warship of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It was designed like other types of cruisers to operate as a long-range, independent warship, capable of defeating any ship apart from a battleship and fast eno ...

s , , and as more modern ships had joined the fleet. She initially served as the flagship of Joseph Besson, though by July 1903 her place as flagship had been taken by the battleship . During this period in reserve, the ship was frequently reactivated for short periods to replace active vessels that had to be docked for maintenance. During the fleet maneuvers in July 1905, ''Charles Martel''s main guns had a rate of fire of one round every nine minutes and her intermediate guns one round about every four minutes. She remained in the ; by 1906, she was in the , under the command of Paul-Louis Germinet. Her above-water torpedo tubes were removed on 13 June. On 16 September, she was present for a major fleet review in Marseilles that saw visits from British, Spanish, and Italian squadrons. The ship was maintained in a state of , a state of reduced readiness; ''Charles Martel'' was in full commission for three months of the year for training, and in reserve with a reduced crew for the remainder. She remained in this status for the duration of 1907. During an exercise off Corsica, the armored cruiser ran aground on 20 November 1907 during a severe storm. After lightening the cruiser, ''Charles Martel'' and the armored cruiser were able to pull ''Condé'' off.

In September 1909 the battleship became the flagship of the Inspector of Flotillas and one of her propellers was damaged by an errant torpedo while the inspector was observing firing exercises by torpedo boats. The following month the was reorganized with the redesignated as the and the as the , since by then the six and s had entered service. The new ships allowed for the creation of a new (Second Battle Squadron) within the , ''Charles Martel'' became the replacement ship for the on 5 October and departed for Cherbourg on 5 November, sustaining some storm damage en route. After her arrival on the 13th, she welcomed King Manuel II of Portugal

'' Dom'' Manuel II (15 November 1889 – 2 July 1932), "the Patriot" ( pt, "o Patriota") or "the Unfortunate" (), was the last King of Portugal, ascending the throne after the assassination of his father, King Carlos I, and his elder brother, ...

to France and then escorted the British royal yacht '' Victoria and Albert'', with King Edward VII

Edward VII (Albert Edward; 9 November 1841 – 6 May 1910) was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and Emperor of India, from 22 January 1901 until his death in 1910.

The second child and eldest son of Queen Victoria and ...

aboard, back to Britain. The ship was assigned to of the on 16 October 1910. Achille Adam hoisted his flag aboard the ship on 21 July 1911. When the s began entering service in that year, the fleet was reorganized again, with ''Charles Martel'' and the other older ships being transferred to the new on 5 October, which was based in Brest

Brest may refer to:

Places

*Brest, Belarus

**Brest Region

**Brest Airport

**Brest Fortress

* Brest, Kyustendil Province, Bulgaria

* Břest, Czech Republic

*Brest, France

** Arrondissement of Brest

**Brest Bretagne Airport

** Château de Brest

*Br ...

, and Adam becoming commander of its .

The ship's hydraulic reloading machinery for the main and intermediate turrets was replaced by manual-loading gear in August 1911, which generally rendered her combat ineffective. She was present for another naval review off Toulon on 4 September. Adam hauled his flag down on 25 February 1912 and ''Charles Martel'' was reduced to reserve status on 1 March. She was reduced to special reserve on 1 July and was transferred to Landévennec

Landévennec (; ) is a commune in the Finistère department of Brittany in north-western France. Population

Geography

Landévennec is located on the Crozon peninsula, southeast of Brest.The river Aulne forms a natural boundary to the east. ...

, Brittany

Brittany (; french: link=no, Bretagne ; br, Breizh, or ; Gallo: ''Bertaèyn'' ) is a peninsula, historical country and cultural area in the west of modern France, covering the western part of what was known as Armorica during the period ...

, in November 1913. Together with her contemporaries ''Brennus'', ''Carnot'' and ''Masséna'', ''Charles Martel'' was decommissioned and hulked to serve as a barracks ship

A barracks ship or barracks barge or berthing barge, or in civilian use accommodation vessel or accommodation ship, is a ship or a non-self-propelled barge containing a superstructure of a type suitable for use as a temporary barracks for s ...

on 1 April 1914.

After the beginning of World War I in August, the ship hosted the headquarters controlling German prisoners of war temporarily housed in fortresses in Brittany in late September. Some of her boilers were removed during the war to equip three tugboat

A tugboat or tug is a marine vessel that manoeuvres other vessels by pushing or pulling them, with direct contact or a tow line. These boats typically tug ships in circumstances where they cannot or should not move under their own power, su ...

s; her main guns were removed in 1915 and bored out to convert them to Obusier de Modèle 1915 railroad

Rail transport (also known as train transport) is a means of transport that transfers passengers and goods on wheeled vehicles running on rails, which are incorporated in tracks. In contrast to road transport, where the vehicles run on a pre ...

howitzers. The ship's 274 mm guns were converted into Canon de 274 Modèle 87/93 Glissement railroad guns two years later and her 138.6 mm guns were placed on wheeled gun carriages for service with the army

An army (from Old French ''armee'', itself derived from the Latin verb ''armāre'', meaning "to arm", and related to the Latin noun ''arma'', meaning "arms" or "weapons"), ground force or land force is a fighting force that fights primarily on ...

. Late in the war she was used as a prison ship

A prison ship, often more accurately described as a prison hulk, is a current or former seagoing vessel that has been modified to become a place of substantive detention for convicts, prisoners of war or civilian internees. While many nat ...

. ''Charles Martel'' was condemned on 30 October 1919 and was listed for sale on 21 September 1920. She was purchased for 675,000 francs

The franc is any of various units of currency. One franc is typically divided into 100 centimes. The name is said to derive from the Latin inscription ''francorum rex'' (King of the Franks) used on early French coins and until the 18th centu ...

on 20 December by the Dutch firm of Franck Rijsdik Shipbreaking & Co. and towed to Hendrik-Ido-Ambacht

Hendrik-Ido-Ambacht () is a town and municipality in the western Netherlands. It is located on the island of IJsselmonde, and borders with Zwijndrecht, Ridderkerk, and the Noord River (with Alblasserdam and Papendrecht on the other side).

The j ...

to begin demolition.

Footnotes

References

* * * * * * * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Charles Martel Ships built in France 1893 ships Battleships of the French Navy