French-Indian War on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The French and Indian War (1754–1763) was a theater of the

In Europe, the French and Indian War is conflated into the Seven Years' War and not given a separate name. "Seven Years" refers to events in Europe, from the official declaration of war in 1756—two years after the French and Indian War had started—to the signing of the peace treaty in 1763. The French and Indian War in America, by contrast, was largely concluded in six years from the

In Europe, the French and Indian War is conflated into the Seven Years' War and not given a separate name. "Seven Years" refers to events in Europe, from the official declaration of war in 1756—two years after the French and Indian War had started—to the signing of the peace treaty in 1763. The French and Indian War in America, by contrast, was largely concluded in six years from the

At this time, North America east of the Mississippi River was largely claimed by either Great Britain or France. Large areas had no colonial settlements. The French population numbered about 75,000 and was heavily concentrated along the St. Lawrence River valley, with some also in Acadia (present-day

At this time, North America east of the Mississippi River was largely claimed by either Great Britain or France. Large areas had no colonial settlements. The French population numbered about 75,000 and was heavily concentrated along the St. Lawrence River valley, with some also in Acadia (present-day  Between the French and British colonists, large areas were dominated by Indian tribes. To the north, the

Between the French and British colonists, large areas were dominated by Indian tribes. To the north, the  At this time, Spain claimed only the province of Florida in eastern America. It controlled Cuba and other territories in the

At this time, Spain claimed only the province of Florida in eastern America. It controlled Cuba and other territories in the

* to reaffirm to New France's Indian allies that their trading arrangements with colonists were exclusive to those authorized by New France

* to confirm Indian assistance in asserting and maintaining the French claim to the territories which French explorers had claimed

* to discourage any alliances between Britain and local Indian tribes

* to impress the Indians with a French show of force against British colonial settler incursion, unauthorized trading expeditions, and general trespass against French claimsAnderson (2000), p. 26.

Céloron's expedition force consisted of about 200 Troupes de la marine and 30 Indians, and they covered about between June and November 1749. They went up the St. Lawrence, continued along the northern shore of

* to reaffirm to New France's Indian allies that their trading arrangements with colonists were exclusive to those authorized by New France

* to confirm Indian assistance in asserting and maintaining the French claim to the territories which French explorers had claimed

* to discourage any alliances between Britain and local Indian tribes

* to impress the Indians with a French show of force against British colonial settler incursion, unauthorized trading expeditions, and general trespass against French claimsAnderson (2000), p. 26.

Céloron's expedition force consisted of about 200 Troupes de la marine and 30 Indians, and they covered about between June and November 1749. They went up the St. Lawrence, continued along the northern shore of

, ''Ohio State Parks Magazine'', Spring 2006 Céloron wrote an extensively detailed report. "All I can say is that the Natives of these localities are very badly disposed towards the French," he wrote, "and are entirely devoted to the English. I don't know in what way they could be brought back." Even before his return to Montreal, reports on the situation in the Ohio Country were making their way to London and Paris, each side proposing that action be taken.

The

The

In the spring of 1753, Paul Marin de la Malgue was given command of a 2,000-man force of Troupes de la Marine and Indians. His orders were to protect the King's land in the Ohio Valley from the British. Marin followed the route that Céloron had mapped out four years earlier. Céloron, however, had limited the record of French claims to the burial of lead plates, whereas Marin constructed and garrisoned forts. He first constructed Fort Presque Isle on Lake Erie's south shore near

In the spring of 1753, Paul Marin de la Malgue was given command of a 2,000-man force of Troupes de la Marine and Indians. His orders were to protect the King's land in the Ohio Valley from the British. Marin followed the route that Céloron had mapped out four years earlier. Céloron, however, had limited the record of French claims to the burial of lead plates, whereas Marin constructed and garrisoned forts. He first constructed Fort Presque Isle on Lake Erie's south shore near

Governor Robert Dinwiddie of Virginia was an investor in the Ohio Company, which stood to lose money if the French held their claim. He ordered 21-year-old Major

Governor Robert Dinwiddie of Virginia was an investor in the Ohio Company, which stood to lose money if the French held their claim. He ordered 21-year-old Major

Following the battle, Washington pulled back several miles and established Fort Necessity, which the Canadians attacked under the command of Jumonville's brother at the

Following the battle, Washington pulled back several miles and established Fort Necessity, which the Canadians attacked under the command of Jumonville's brother at the  In a second British action, Admiral Edward Boscawen fired on the French ship ''Alcide'' on June 8, 1755, capturing her and two troop ships.Fowler, pp. 74–75. The British harassed French shipping throughout 1755, seizing ships and capturing seamen. These actions contributed to the eventual formal declarations of war in spring 1756.Fowler, p. 98.

An early important political response to the opening of hostilities was the convening of the

In a second British action, Admiral Edward Boscawen fired on the French ship ''Alcide'' on June 8, 1755, capturing her and two troop ships.Fowler, pp. 74–75. The British harassed French shipping throughout 1755, seizing ships and capturing seamen. These actions contributed to the eventual formal declarations of war in spring 1756.Fowler, p. 98.

An early important political response to the opening of hostilities was the convening of the

Braddock led about 1,500 army troops and provincial militia on the Braddock expedition in June 1755 to take Fort Duquesne, with George Washington as one of his aides. The expedition was a disaster. It was attacked by French regulars, Canadian Militiamen, and Indian warriors ambushing them from hiding places up in trees and behind logs, and Braddock called for a retreat. He was killed and approximately 1,000 British soldiers were killed or injured. The remaining 500 British troops retreated to Virginia, led by Washington. Washington and

Braddock led about 1,500 army troops and provincial militia on the Braddock expedition in June 1755 to take Fort Duquesne, with George Washington as one of his aides. The expedition was a disaster. It was attacked by French regulars, Canadian Militiamen, and Indian warriors ambushing them from hiding places up in trees and behind logs, and Braddock called for a retreat. He was killed and approximately 1,000 British soldiers were killed or injured. The remaining 500 British troops retreated to Virginia, led by Washington. Washington and

Newcastle replaced him in January 1756 with Lord Loudoun, with Major General James Abercrombie as his second in command. Neither of these men had as much campaign experience as the trio of officers whom France sent to North America. French regular army reinforcements arrived in New France in May 1756, led by Major General

Newcastle replaced him in January 1756 with Lord Loudoun, with Major General James Abercrombie as his second in command. Neither of these men had as much campaign experience as the trio of officers whom France sent to North America. French regular army reinforcements arrived in New France in May 1756, led by Major General  The new British command was not in place until July. Abercrombie arrived in Albany but refused to take any significant actions until Loudoun approved them, and Montcalm took bold action against his inertia. He built on Vaudreuil's work harassing the Oswego garrison and executed a strategic

The new British command was not in place until July. Abercrombie arrived in Albany but refused to take any significant actions until Loudoun approved them, and Montcalm took bold action against his inertia. He built on Vaudreuil's work harassing the Oswego garrison and executed a strategic  French irregular forces (Canadian scouts and Indians) harassed Fort William Henry throughout the first half of 1757. In January, they ambushed British rangers near Ticonderoga. In February, they launched a raid against the position across the frozen Lake George, destroying storehouses and buildings outside the main fortification. In early August, Montcalm and 7,000 troops besieged the fort, which capitulated with an agreement to withdraw under parole. When the withdrawal began, some of Montcalm's Indian allies attacked the British column because they were angry about the lost opportunity for loot, killing and capturing several hundred men, women, children, and slaves. The aftermath of the siege may have contributed to the transmission of

French irregular forces (Canadian scouts and Indians) harassed Fort William Henry throughout the first half of 1757. In January, they ambushed British rangers near Ticonderoga. In February, they launched a raid against the position across the frozen Lake George, destroying storehouses and buildings outside the main fortification. In early August, Montcalm and 7,000 troops besieged the fort, which capitulated with an agreement to withdraw under parole. When the withdrawal began, some of Montcalm's Indian allies attacked the British column because they were angry about the lost opportunity for loot, killing and capturing several hundred men, women, children, and slaves. The aftermath of the siege may have contributed to the transmission of

Newcastle and Pitt joined in an uneasy coalition in which Pitt dominated the military planning. He embarked on a plan for the 1758 campaign that was largely developed by Loudoun. He had been replaced by Abercrombie as commander in chief after the failures of 1757. Pitt's plan called for three major offensive actions involving large numbers of regular troops supported by the provincial militias, aimed at capturing the heartlands of New France. Two of the expeditions were successful, with

Newcastle and Pitt joined in an uneasy coalition in which Pitt dominated the military planning. He embarked on a plan for the 1758 campaign that was largely developed by Loudoun. He had been replaced by Abercrombie as commander in chief after the failures of 1757. Pitt's plan called for three major offensive actions involving large numbers of regular troops supported by the provincial militias, aimed at capturing the heartlands of New France. Two of the expeditions were successful, with

The third invasion was stopped with the improbable French victory in the

The third invasion was stopped with the improbable French victory in the

The British proceeded to wage a campaign in the northwest frontier of Canada in an effort to cut off the French frontier forts to the west and south. They captured Ticonderoga and

The British proceeded to wage a campaign in the northwest frontier of Canada in an effort to cut off the French frontier forts to the west and south. They captured Ticonderoga and

Governor Vaudreuil in Montreal negotiated a capitulation with General Amherst in September 1760. Amherst granted his requests that any French residents who chose to remain in the colony would be given freedom to continue worshiping in their

Governor Vaudreuil in Montreal negotiated a capitulation with General Amherst in September 1760. Amherst granted his requests that any French residents who chose to remain in the colony would be given freedom to continue worshiping in their

The war changed economic, political, governmental, and social relations among the three European powers, their colonies, and the people who inhabited those territories. France and Britain both suffered financially because of the war, with significant long-term consequences.

Britain gained control of

The war changed economic, political, governmental, and social relations among the three European powers, their colonies, and the people who inhabited those territories. France and Britain both suffered financially because of the war, with significant long-term consequences.

Britain gained control of  The Quebec Act of 1774 addressed issues brought forth by Roman Catholic French Canadians from the 1763 proclamation, and it transferred the

The Quebec Act of 1774 addressed issues brought forth by Roman Catholic French Canadians from the 1763 proclamation, and it transferred the

excerpt

* * * * Nester, William R. ''The French and Indian War and the Conquest of New France'' (2015)

excerpt

* * Parkman, Francis.

Montcalm and Wolfe: The French and Indian War

'. Originally published 1884. New York: Da Capo, 1984. . * West, Doug (2016) ''French and Indian War – A Short History'

30 Minute Book Series

*

Map of French and Indian War. French and British forts and settlements, Indian tribes.

French and Indian War Profile and Videos

– Chickasaw.TV

The War That Made America

from PBS

FORGOTTEN WAR: Struggle for North America

from PBS

Seven Years' War timeline

online ebook

developed by HistoryAnimated.com {{DEFAULTSORT:French And Indian War Anglo-French wars Seven Years' War 1750s conflicts 1760s conflicts 1750s in Canada 1760s in Canada 1750s in New France 1760s in New France 1750s in the Thirteen Colonies 1760s in the Thirteen Colonies Colonization history of the United States Conflicts in New Brunswick Conflicts in Nova Scotia Events in New France Military history of Acadia Military history of New England Military history of the Thirteen Colonies Military history of Canada Military history of the Great Lakes New France Wabanaki Confederacy Wars involving France Wars involving Great Britain Wars involving the indigenous peoples of North America Wars involving the states and peoples of North America 18th century in Canada 18th century in New France 18th century in the British Empire 18th century in the French colonial empire 18th century in the Thirteen Colonies

Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (1754 ...

, which pitted the North American colonies of the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

against those of the French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

, each side being supported by various Native American tribes. At the start of the war, the French colonies had a population of roughly 60,000 settlers, compared with 2 million in the British colonies. The outnumbered French particularly depended on their native allies.

Two years into the French and Indian War, in 1756, Great Britain declared war on France, beginning the worldwide Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (1754 ...

. Many view the French and Indian War as being merely the American theater of this conflict; however, in the United States the French and Indian War is viewed as a singular conflict which was not associated with any European war. French Canadians call it the ('War of the Conquest').: 1756–1763

The British colonists were supported at various times by the Iroquois

The Iroquois ( or ), officially the Haudenosaunee ( meaning "people of the longhouse"), are an Iroquoian Peoples, Iroquoian-speaking Confederation#Indigenous confederations in North America, confederacy of First Nations in Canada, First Natio ...

, Catawba, and Cherokee

The Cherokee (; chr, ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯᎢ, translit=Aniyvwiyaʔi or Anigiduwagi, or chr, ᏣᎳᎩ, links=no, translit=Tsalagi) are one of the indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States. Prior to the 18th century, th ...

tribes, and the French colonists were supported by Wabanaki Confederacy

The Wabanaki Confederacy (''Wabenaki, Wobanaki'', translated to "People of the Dawn" or "Easterner") is a North American First Nations and Native American confederation of four principal Eastern Algonquian nations: the Miꞌkmaq, Maliseet ( ...

member tribes Abenaki

The Abenaki ( Abenaki: ''Wαpánahki'') are an Indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands of Canada and the United States. They are an Algonquian-speaking people and part of the Wabanaki Confederacy. The Eastern Abenaki language was pre ...

and Mi'kmaq

The Mi'kmaq (also ''Mi'gmaq'', ''Lnu'', ''Miꞌkmaw'' or ''Miꞌgmaw''; ; ) are a First Nations people of the Northeastern Woodlands, indigenous to the areas of Canada's Atlantic Provinces and the Gaspé Peninsula of Quebec as well as the no ...

, and the Algonquin, Lenape

The Lenape (, , or Lenape , del, Lënapeyok) also called the Leni Lenape, Lenni Lenape and Delaware people, are an indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands, who live in the United States and Canada. Their historical territory inclu ...

, Ojibwa

The Ojibwe, Ojibwa, Chippewa, or Saulteaux are an Anishinaabe people in what is currently southern Canada, the northern Midwestern United States, and Northern Plains.

According to the U.S. census, in the United States Ojibwe people are one of ...

, Ottawa

Ottawa (, ; Canadian French: ) is the capital city of Canada. It is located at the confluence of the Ottawa River and the Rideau River in the southern portion of the province of Ontario. Ottawa borders Gatineau, Quebec, and forms the c ...

, Shawnee

The Shawnee are an Algonquian-speaking indigenous people of the Northeastern Woodlands. In the 17th century they lived in Pennsylvania, and in the 18th century they were in Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana and Illinois, with some bands in Kentucky a ...

, and Wyandot (Huron) tribes. Fighting took place primarily along the frontiers between New France and the British colonies, from the Province of Virginia

The Colony of Virginia, chartered in 1606 and settled in 1607, was the first enduring English colony in North America, following failed attempts at settlement on Newfoundland by Sir Humphrey GilbertGilbert (Saunders Family), Sir Humphrey" (hist ...

in the south to Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador (; french: Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador; frequently abbreviated as NL) is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region ...

in the north. It began with a dispute over control of the confluence of the Allegheny River

The Allegheny River ( ) is a long headwater stream of the Ohio River in western Pennsylvania and New York. The Allegheny River runs from its headwaters just below the middle of Pennsylvania's northern border northwesterly into New York then i ...

and Monongahela River

The Monongahela River ( , )—often referred to locally as the Mon ()—is a U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map accessed August 15, 2011 river on the Allegheny Plateau in north-c ...

called the Forks of the Ohio, and the site of the French Fort Duquesne

Fort Duquesne (, ; originally called ''Fort Du Quesne'') was a fort established by the French in 1754, at the confluence of the Allegheny and Monongahela rivers. It was later taken over by the British, and later the Americans, and developed a ...

at the location that later became Pittsburgh

Pittsburgh ( ) is a city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, United States, and the county seat of Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, Allegheny County. It is the most populous city in both Allegheny County and Wester ...

, Pennsylvania. The dispute erupted into violence in the Battle of Jumonville Glen

The Battle of Jumonville Glen, also known as the Jumonville affair, was the opening battle of the French and Indian War, fought on May 28, 1754, near present-day Hopwood and Uniontown in Fayette County, Pennsylvania. A company of provincial ...

in May 1754, during which Virginia militiamen under the command of 22-year-old George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of ...

ambushed a French patrol.

In 1755, six colonial governors met with General Edward Braddock

Major-General Edward Braddock (January 1695 – 13 July 1755) was a British officer and commander-in-chief for the Thirteen Colonies during the start of the French and Indian War (1754–1763), the North American front of what is known in Europ ...

, the newly arrived British Army commander, and planned a four-way attack on the French. None succeeded, and the main effort by Braddock proved a disaster; he lost the Battle of the Monongahela on July 9, 1755, and died a few days later. British operations failed in the frontier areas of the Province of Pennsylvania

The Province of Pennsylvania, also known as the Pennsylvania Colony, was a British North American colony founded by William Penn after receiving a land grant from Charles II of England in 1681. The name Pennsylvania ("Penn's Woods") refers to Wi ...

and the Province of New York

The Province of New York (1664–1776) was a British proprietary colony and later royal colony on the northeast coast of North America. As one of the Middle Colonies, New York achieved independence and worked with the others to found the U ...

during 1755–57 due to a combination of poor management, internal divisions, effective Canadian scouts, French regular forces, and Native warrior allies. In 1755, the British captured Fort Beauséjour on the border separating Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia ( ; ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. Nova Scotia is Latin for "New Scotland".

Most of the population are native Eng ...

from Acadia

Acadia (french: link=no, Acadie) was a colony of New France in northeastern North America which included parts of what are now the Maritime provinces, the Gaspé Peninsula and Maine to the Kennebec River. During much of the 17th and earl ...

, and they ordered the expulsion of the Acadians

The Expulsion of the Acadians, also known as the Great Upheaval, the Great Expulsion, the Great Deportation, and the Deportation of the Acadians (french: Le Grand Dérangement or ), was the forced removal, by the British, of the Acadian peo ...

(1755–64) soon afterwards. Orders for the deportation were given by Commander-in-Chief William Shirley without direction from Great Britain. The Acadians were expelled, both those captured in arms and those who had sworn the loyalty oath to the King. Natives likewise were driven off the land to make way for settlers from New England.

The British colonial government fell in the region of Nova Scotia after several disastrous campaigns in 1757, including a failed expedition against Louisbourg and the Siege of Fort William Henry

The siege of Fort William Henry (3–9 August 1757, french: Bataille de Fort William Henry) was conducted by a French and Indian force led by Louis-Joseph de Montcalm against the British-held Fort William Henry. The fort, located at the south ...

; this last was followed by the Natives torturing and massacring their colonial victims. William Pitt came to power and significantly increased British military resources in the colonies at a time when France was unwilling to risk large convoys to aid the limited forces that they had in New France, preferring to concentrate their forces against Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an e ...

and its allies who were now engaged in the Seven Years' War in Europe. The conflict in Ohio ended in 1758 with the British–American victory in the Ohio Country. Between 1758 and 1760, the British military launched a campaign to capture French Canada

French Canadians (referred to as Canadiens mainly before the twentieth century; french: Canadiens français, ; feminine form: , ), or Franco-Canadians (french: Franco-Canadiens), refers to either an ethnic group who trace their ancestry to Fre ...

. They succeeded in capturing territory in surrounding colonies and ultimately the city of Quebec (1759). The following year the British were victorious in the Montreal Campaign in which the French ceded Canada in accordance with the Treaty of Paris (1763)

The Treaty of Paris, also known as the Treaty of 1763, was signed on 10 February 1763 by the kingdoms of Great Britain, France and Spain, with Portugal in agreement, after Great Britain and Prussia's victory over France and Spain during the S ...

.

France also ceded its territory east of the Mississippi to Great Britain, as well as French Louisiana

The term French Louisiana refers to two distinct regions:

* first, to colonial French Louisiana, comprising the massive, middle section of North America claimed by France during the 17th and 18th centuries; and,

* second, to modern French Louisi ...

west of the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the List of longest rivers of the United States (by main stem), second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest Drainage system (geomorphology), drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson B ...

to its ally Spain in compensation for Spain's loss to Britain of Spanish Florida

Spanish Florida ( es, La Florida) was the first major European land claim and attempted settlement in North America during the European Age of Discovery. ''La Florida'' formed part of the Captaincy General of Cuba, the Viceroyalty of New Spain, ...

. (Spain had ceded Florida to Britain in exchange for the return of Havana

Havana (; Spanish: ''La Habana'' ) is the capital and largest city of Cuba. The heart of the La Habana Province, Havana is the country's main port and commercial center.

, Cuba.) France's colonial presence north of the Caribbean was reduced to the islands of Saint Pierre and Miquelon

Saint Pierre and Miquelon (), officially the Territorial Collectivity of Saint-Pierre and Miquelon (french: link=no, Collectivité territoriale de Saint-Pierre et Miquelon ), is a self-governing territorial overseas collectivity of France in t ...

, confirming Great Britain's position as the dominant colonial power in northern America

Northern America is the northernmost subregion of North America. The boundaries may be drawn slightly differently. In one definition, it lies directly north of Middle America (including the Caribbean and Central America).Gonzalez, Joseph. 20 ...

.

Nomenclature

In British America, wars were often named after the sitting British monarch, such asKing William's War

King William's War (also known as the Second Indian War, Father Baudoin's War, Castin's War, or the First Intercolonial War in French) was the North American theater of the Nine Years' War (1688–1697), also known as the War of the Grand Alli ...

or Queen Anne's War

Queen Anne's War (1702–1713) was the second in a series of French and Indian Wars fought in North America involving the colonial empires of Great Britain, France, and Spain; it took place during the reign of Anne, Queen of Great Britain. In E ...

. There had already been a King George's War

King George's War (1744–1748) is the name given to the military operations in North America that formed part of the War of the Austrian Succession (1740–1748). It was the third of the four French and Indian Wars. It took place primarily in t ...

in the 1740s during the reign of King George II, so British colonists named this conflict after their opponents, and it became known as the ''French and Indian War''. This continues as the standard name for the war in the United States, although Indians fought on both sides of the conflict. It also led into the Seven Years' War overseas, a much larger conflict between France and Great Britain that did not involve the American colonies; some historians make a connection between the French and Indian War and the Seven Years' War overseas, but most residents of the United States consider them as two separate conflicts—only one of which involved the American colonies, and American historians generally use the traditional name. Less frequently used names for the war include the ''Fourth Intercolonial War'' and the ''Great War for the Empire''.Anderson (2000), p. 747.

In Europe, the French and Indian War is conflated into the Seven Years' War and not given a separate name. "Seven Years" refers to events in Europe, from the official declaration of war in 1756—two years after the French and Indian War had started—to the signing of the peace treaty in 1763. The French and Indian War in America, by contrast, was largely concluded in six years from the

In Europe, the French and Indian War is conflated into the Seven Years' War and not given a separate name. "Seven Years" refers to events in Europe, from the official declaration of war in 1756—two years after the French and Indian War had started—to the signing of the peace treaty in 1763. The French and Indian War in America, by contrast, was largely concluded in six years from the Battle of Jumonville Glen

The Battle of Jumonville Glen, also known as the Jumonville affair, was the opening battle of the French and Indian War, fought on May 28, 1754, near present-day Hopwood and Uniontown in Fayette County, Pennsylvania. A company of provincial ...

in 1754 to the capture of Montreal in 1760.

Canadians conflate both the European and American conflicts into the Seven Years' War (). French Canadians also use the term "War of Conquest" (), since it is the war in which New France

New France (french: Nouvelle-France) was the area colonized by France in North America, beginning with the exploration of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to Great Britain and Spa ...

was conquered by the British and became part of the British Empire. In Quebec, this term was promoted by popular historians Jacques Lacoursière

Jacques Lacoursière, (4 May 1932 – 1 June 2021) was a Canadian TV host, author and historian.

Life and career

Lacoursière was born in Shawinigan, in the Mauricie region, and then resided in Beauport in the Greater Quebec area.

Lacoursi� ...

and Denis Vaugeois

Denis Vaugeois (born September 7, 1935) is a French-speaking author, publisher and historian from Quebec, Canada. He also served as a Member of the National Assembly (MNA) from 1976 to 1985.

Biography

He was born in Saint-Tite, a small town n ...

, who borrowed from the ideas of Maurice Séguin in considering this war as a dramatic tipping point of French Canadian identity and nationhood.

Background

At this time, North America east of the Mississippi River was largely claimed by either Great Britain or France. Large areas had no colonial settlements. The French population numbered about 75,000 and was heavily concentrated along the St. Lawrence River valley, with some also in Acadia (present-day

At this time, North America east of the Mississippi River was largely claimed by either Great Britain or France. Large areas had no colonial settlements. The French population numbered about 75,000 and was heavily concentrated along the St. Lawrence River valley, with some also in Acadia (present-day New Brunswick

New Brunswick (french: Nouveau-Brunswick, , locally ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. It is the only province with both English and ...

and parts of Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia ( ; ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. Nova Scotia is Latin for "New Scotland".

Most of the population are native Eng ...

), including Île Royale (Cape Breton Island

Cape Breton Island (french: link=no, île du Cap-Breton, formerly '; gd, Ceap Breatainn or '; mic, Unamaꞌki) is an island on the Atlantic coast of North America and part of the province of Nova Scotia, Canada.

The island accounts for 18. ...

). Fewer lived in ; Biloxi, Mississippi

Biloxi ( ; ) is a city in and one of two county seats of Harrison County, Mississippi, United States (the other being the adjacent city of Gulfport). The 2010 United States Census recorded the population as 44,054 and in 2019 the estimated popu ...

; Mobile, Alabama

Mobile ( , ) is a city and the county seat of Mobile County, Alabama, United States. The population within the city limits was 187,041 at the 2020 census, down from 195,111 at the 2010 census. It is the fourth-most-populous city in Alabama ...

; and small settlements in the Illinois Country

The Illinois Country (french: Pays des Illinois ; , i.e. the Illinois people)—sometimes referred to as Upper Louisiana (french: Haute-Louisiane ; es, Alta Luisiana)—was a vast region of New France claimed in the 1600s in what is n ...

, hugging the east side of the Mississippi River and its tributaries. French fur traders and trappers traveled throughout the St. Lawrence and Mississippi watersheds, did business with local Indian tribes, and often married Indian women. Traders married daughters of chiefs, creating high-ranking unions.

British settlers outnumbered the French 20 to 1 with a population of about 1.5 million ranged along the Atlantic coast of the continent from Nova Scotia and the Colony of Newfoundland

Newfoundland Colony was an English overseas possessions, English and, later, British Empire, British colony established in 1610 on the Newfoundland (island), island of Newfoundland off the Atlantic coast of Canada, in what is now the province of ...

in the north to the Province of Georgia

A province is almost always an administrative division within a country or state. The term derives from the ancient Roman ''provincia'', which was the major territorial and administrative unit of the Roman Empire's territorial possessions out ...

in the south. Many of the older colonies' land claims extended arbitrarily far to the west, as the extent of the continent was unknown at the time when their provincial charters were granted. Their population centers were along the coast, but the settlements were growing into the interior. The British captured Nova Scotia from France in 1713, which still had a significant French-speaking population. Britain also claimed Rupert's Land where the Hudson's Bay Company

The Hudson's Bay Company (HBC; french: Compagnie de la Baie d'Hudson) is a Canadian retail business group. A fur trading business for much of its existence, HBC now owns and operates retail stores in Canada. The company's namesake business di ...

traded for furs with local Indian tribes.

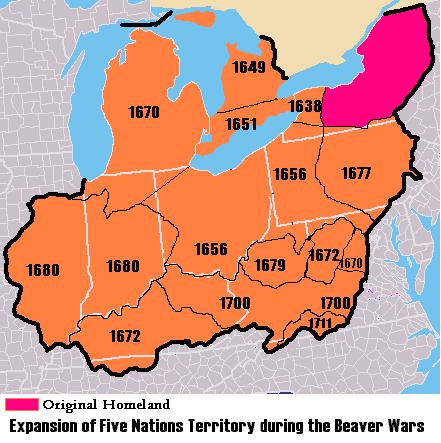

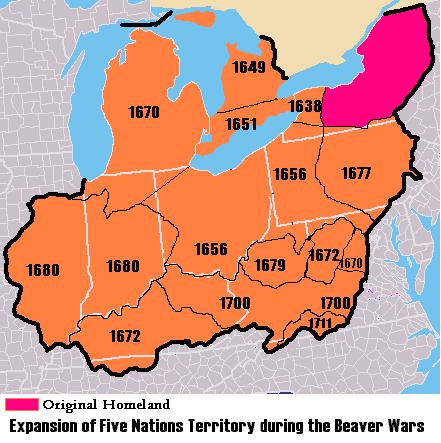

Between the French and British colonists, large areas were dominated by Indian tribes. To the north, the

Between the French and British colonists, large areas were dominated by Indian tribes. To the north, the Mi'kmaq

The Mi'kmaq (also ''Mi'gmaq'', ''Lnu'', ''Miꞌkmaw'' or ''Miꞌgmaw''; ; ) are a First Nations people of the Northeastern Woodlands, indigenous to the areas of Canada's Atlantic Provinces and the Gaspé Peninsula of Quebec as well as the no ...

and the Abenakis

The Abenaki (Abenaki: ''Wαpánahki'') are an Indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands of Canada and the United States. They are an Algonquian-speaking people and part of the Wabanaki Confederacy. The Eastern Abenaki language was pred ...

were engaged in Father Le Loutre's War

Father Le Loutre's War (1749–1755), also known as the Indian War, the Mi'kmaq War and the Anglo-Mi'kmaq War, took place between King George's War and the French and Indian War in Acadia and Nova Scotia. On one side of the conflict, the Br ...

and still held sway in parts of Nova Scotia, Acadia, and the eastern portions of the province of Canada

The Province of Canada (or the United Province of Canada or the United Canadas) was a British colony in North America from 1841 to 1867. Its formation reflected recommendations made by John Lambton, 1st Earl of Durham, in the Report on the ...

, as well as much of Maine. The Iroquois Confederation dominated much of upstate New York and the Ohio Country, although Ohio also included Algonquian-speaking populations of Delaware

Delaware ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States, bordering Maryland to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and New Jersey and the Atlantic Ocean to its east. The state takes its name from the adjacent ...

and Shawnee

The Shawnee are an Algonquian-speaking indigenous people of the Northeastern Woodlands. In the 17th century they lived in Pennsylvania, and in the 18th century they were in Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana and Illinois, with some bands in Kentucky a ...

, as well as Iroquoian

The Iroquoian languages are a language family of indigenous peoples of North America. They are known for their general lack of labial consonants. The Iroquoian languages are polysynthetic and head-marking.

As of 2020, all surviving Iroquoia ...

-speaking Mingos

The Mingo people are an Iroquoian group of Native Americans, primarily Seneca and Cayuga, who migrated west from New York to the Ohio Country in the mid-18th century, and their descendants. Some Susquehannock survivors also joined them, and ...

. These tribes were formally under Iroquois rule and were limited by them in their authority to make agreements.Anderson (2000), p. 23 The Iroquois Confederation initially held a stance of neutrality to ensure continued trade with both French and British. Though maintaining this stance proved difficult as the Iroquois Confederation tribes sided and supported French or British causes depending on which side provided the most beneficial trade.

The Southeast interior was dominated by Siouan-speaking Catawbas, Muskogee-speaking Creeks and Choctaw

The Choctaw (in the Choctaw language, Chahta) are a Native American people originally based in the Southeastern Woodlands, in what is now Alabama and Mississippi. Their Choctaw language is a Western Muskogean language. Today, Choctaw people are ...

, and the Iroquoian-speaking Cherokee

The Cherokee (; chr, ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯᎢ, translit=Aniyvwiyaʔi or Anigiduwagi, or chr, ᏣᎳᎩ, links=no, translit=Tsalagi) are one of the indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States. Prior to the 18th century, th ...

tribes. When war broke out, the French colonists used their trading connections to recruit fighters from tribes in western portions of the Great Lakes region

The Great Lakes region of North America is a binational Canadian–American region that includes portions of the eight U.S. states of Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Minnesota, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin along with the Canadian p ...

, which was not directly subject to the conflict between the French and British; these included the Hurons, Mississaugas

The Mississauga are a subtribe of the Anishinaabe-speaking First Nations peoples located in southern Ontario, Canada. They are closely related to the Ojibwe. The name "Mississauga" comes from the Anishinaabe word ''Misi-zaagiing'', meaning " ho ...

, Ojibwas, Winnebagos

The Ho-Chunk, also known as Hoocągra or Winnebago (referred to as ''Hotúŋe'' in the neighboring indigenous Iowa-Otoe language), are a Siouan-speaking Native American people whose historic territory includes parts of Wisconsin, Minnesota, Iow ...

, and Potawatomi

The Potawatomi , also spelled Pottawatomi and Pottawatomie (among many variations), are a Native American people of the western Great Lakes region, upper Mississippi River and Great Plains. They traditionally speak the Potawatomi language, a m ...

.

The British colonists were supported in the war by the Iroquois Six Nations and also by the Cherokees, until differences sparked the Anglo-Cherokee War in 1758. In 1758, the Province of Pennsylvania

The Province of Pennsylvania, also known as the Pennsylvania Colony, was a British North American colony founded by William Penn after receiving a land grant from Charles II of England in 1681. The name Pennsylvania ("Penn's Woods") refers to Wi ...

successfully negotiated the Treaty of Easton in which a number of tribes in the Ohio Country promised neutrality in exchange for land concessions and other considerations. Most of the other northern tribes sided with the French, their primary trading partner and supplier of arms. The Creeks and Cherokees were subject to diplomatic efforts by both the French and British to gain either their support or neutrality in the conflict.

At this time, Spain claimed only the province of Florida in eastern America. It controlled Cuba and other territories in the

At this time, Spain claimed only the province of Florida in eastern America. It controlled Cuba and other territories in the West Indies

The West Indies is a subregion of North America, surrounded by the North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea that includes 13 independent island countries and 18 dependencies and other territories in three major archipelagos: the Greate ...

that became military objectives in the Seven Years' War. Florida's European population was a few hundred, concentrated in St. Augustine

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; la, Aurelius Augustinus Hipponensis; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430), also known as Saint Augustine, was a theologian and philosopher of Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia, Roman North Afr ...

.

There were no French regular army troops stationed in America at the onset of war. New France was defended by about 3,000 troupes de la marine, companies of colonial regulars (some of whom had significant woodland combat experience). The colonial government recruited militia support when needed. The British had few troops. Most of the British colonies mustered local militia companies to deal with Indian threats, generally ill trained and available only for short periods, but they did not have any standing forces. Virginia, by contrast, had a large frontier with several companies of British regulars.

When hostilities began, the British colonial governments preferred operating independently of one another and of the government in London. This situation complicated negotiations with Indian tribes, whose territories often encompassed land claimed by multiple colonies. As the war progressed, the leaders of the British Army establishment tried to impose constraints and demands on the colonial administrations.

Céloron's expedition

New France's Governor-General Roland-Michel Barrin de La Galissonière was concerned about the incursion and expanding influence in the Ohio Country of British colonial traders such asGeorge Croghan

George Croghan (c. 1718 – August 31, 1782) was an Irish-born fur trader in the Ohio Country of North America (current United States) who became a key early figure in the region. In 1746 he was appointed to the Onondaga Council, the governin ...

. In June 1747, he ordered Pierre-Joseph Céloron to lead a military expedition through the area. Its objectives were:

* to reaffirm to New France's Indian allies that their trading arrangements with colonists were exclusive to those authorized by New France

* to confirm Indian assistance in asserting and maintaining the French claim to the territories which French explorers had claimed

* to discourage any alliances between Britain and local Indian tribes

* to impress the Indians with a French show of force against British colonial settler incursion, unauthorized trading expeditions, and general trespass against French claimsAnderson (2000), p. 26.

Céloron's expedition force consisted of about 200 Troupes de la marine and 30 Indians, and they covered about between June and November 1749. They went up the St. Lawrence, continued along the northern shore of

* to reaffirm to New France's Indian allies that their trading arrangements with colonists were exclusive to those authorized by New France

* to confirm Indian assistance in asserting and maintaining the French claim to the territories which French explorers had claimed

* to discourage any alliances between Britain and local Indian tribes

* to impress the Indians with a French show of force against British colonial settler incursion, unauthorized trading expeditions, and general trespass against French claimsAnderson (2000), p. 26.

Céloron's expedition force consisted of about 200 Troupes de la marine and 30 Indians, and they covered about between June and November 1749. They went up the St. Lawrence, continued along the northern shore of Lake Ontario

Lake Ontario is one of the five Great Lakes of North America. It is bounded on the north, west, and southwest by the Canadian province of Ontario, and on the south and east by the U.S. state of New York. The Canada–United States border sp ...

, crossed the portage at Niagara, and followed the southern shore of Lake Erie

Lake Erie ( "eerie") is the fourth largest lake by surface area of the five Great Lakes in North America and the eleventh-largest globally. It is the southernmost, shallowest, and smallest by volume of the Great Lakes and therefore also ha ...

. At the Chautauqua Portage near Barcelona, New York

Westfield is a town in the western part of Chautauqua County, New York, United States. The population was 4,513 at the 2020 census. Westfield is also the name of a village within the town, containing 65% of the town's population. This unique to ...

, the expedition moved inland to the Allegheny River

The Allegheny River ( ) is a long headwater stream of the Ohio River in western Pennsylvania and New York. The Allegheny River runs from its headwaters just below the middle of Pennsylvania's northern border northwesterly into New York then i ...

, which it followed to the site of Pittsburgh

Pittsburgh ( ) is a city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, United States, and the county seat of Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, Allegheny County. It is the most populous city in both Allegheny County and Wester ...

. There Céloron buried lead plates engraved with the French claim to the Ohio Country. Whenever he encountered British colonial merchants or fur-traders, he informed them of the French claims on the territory and told them to leave.

Céloron's expedition arrived at Logstown

"extensive flats"

, settlement_type = Historic Native American village

, image_skyline = Image:Logstown1.jpg

, imagesize = 220px

, image_alt =

, image_map1 = Pennsylvania in United States ...

where the Indians in the area informed him that they owned the Ohio Country and that they would trade with the British colonists regardless of the French.Fowler, p. 14. He continued south until his expedition reached the confluence of the Ohio and the Miami

Miami ( ), officially the City of Miami, known as "the 305", "The Magic City", and "Gateway to the Americas", is a coastal metropolis and the county seat of Miami-Dade County in South Florida, United States. With a population of 442,241 at ...

rivers, which lay just south of the village of Pickawillany

"ash people"

, settlement_type = Historic Native American village

, image_skyline =

, imagesize =

, image_alt =

, image_map1 = OHMap-doton-Piqua.png

, mapsize1 = 22 ...

, the home of the Miami

Miami ( ), officially the City of Miami, known as "the 305", "The Magic City", and "Gateway to the Americas", is a coastal metropolis and the county seat of Miami-Dade County in South Florida, United States. With a population of 442,241 at ...

chief known as "Old Briton Memeskia (in Miami-Illinois: Meemeehšihkia - ′Dragonfly′, c. 1695 – June 21, 1752), known as "Old Briton" by the British and as "La Demoiselle" by the French, was an eighteenth-century Piankashaw chieftain who fought against the French in 174 ...

". Céloron threatened Old Briton with severe consequences if he continued to trade with British colonists, but Old Briton ignored the warning. Céloron returned disappointedly to Montreal in November 1749."Park Spotlight: Lake Loramie", ''Ohio State Parks Magazine'', Spring 2006 Céloron wrote an extensively detailed report. "All I can say is that the Natives of these localities are very badly disposed towards the French," he wrote, "and are entirely devoted to the English. I don't know in what way they could be brought back." Even before his return to Montreal, reports on the situation in the Ohio Country were making their way to London and Paris, each side proposing that action be taken.

Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut Massachusett_writing_systems.html" ;"title="nowiki/> məhswatʃəwiːsət.html" ;"title="Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət">Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət'' En ...

governor William Shirley was particularly forceful, stating that British colonists would not be safe as long as the French were present.Fowler, p. 15.

Negotiations

War of the Austrian Succession

The War of the Austrian Succession () was a European conflict that took place between 1740 and 1748. Fought primarily in Central Europe, the Austrian Netherlands, Italy, the Atlantic and Mediterranean, related conflicts included King George ...

ended in 1748 with the signing of the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle, which was primarily focused on resolving issues in Europe. The issues of conflicting territorial claims between British and French colonies were turned over to a commission, but it reached no decision. Frontier areas were claimed by both sides, from Nova Scotia and Acadia in the north to the Ohio Country in the south. The disputes also extended into the Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe ...

, where both powers wanted access to the rich fisheries of the Grand Banks

The Grand Banks of Newfoundland are a series of underwater plateaus south-east of the island of Newfoundland on the North American continental shelf. The Grand Banks are one of the world's richest fishing grounds, supporting Atlantic cod, sword ...

off Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador (; french: Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador; frequently abbreviated as NL) is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region ...

.

In 1749, the British government gave land to the Ohio Company of Virginia for the purpose of developing trade and settlements in the Ohio Country. The grant required that it settle 100 families in the territory and construct a fort for their protection. But the territory was also claimed by Pennsylvania, and both colonies began pushing for action to improve their respective claims. In 1750, Christopher Gist explored the Ohio territory, acting on behalf of both Virginia and the company, and he opened negotiations with the Indian tribes at Logstown. He completed the 1752 Treaty of Logstown in which the local Indians agreed to terms through their "Half-King" Tanacharison and an Iroquois representative. These terms included permission to build a strong house at the mouth of the Monongahela River

The Monongahela River ( , )—often referred to locally as the Mon ()—is a U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map accessed August 15, 2011 river on the Allegheny Plateau in north-c ...

on the modern site of Pittsburgh

Pittsburgh ( ) is a city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, United States, and the county seat of Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, Allegheny County. It is the most populous city in both Allegheny County and Wester ...

, Pennsylvania.

Escalation in Ohio Country

Governor-General of New France Marquis de la Jonquière died on March 17, 1752, and he was temporarily replaced by Charles le Moyne de Longueuil. His permanent replacement was to be the Marquis Duquesne, but he did not arrive in New France until 1752 to take over the post. The continuing British activity in the Ohio territories prompted Longueuil to dispatch another expedition to the area under the command of Charles Michel de Langlade, an officer in the Troupes de la Marine. Langlade was given 300 men, including French-Canadians and warriors of the Ottawa tribe. His objective was to punish the Miami people of Pickawillany for not following Céloron's orders to cease trading with the British. On June 21, the French war party attacked the trading center at Pickawillany, capturing three traders and killing 14 Miami Indians, including Old Briton. He was reportedly ritually cannibalized by some Indians in the expedition party.Construction of French fortifications

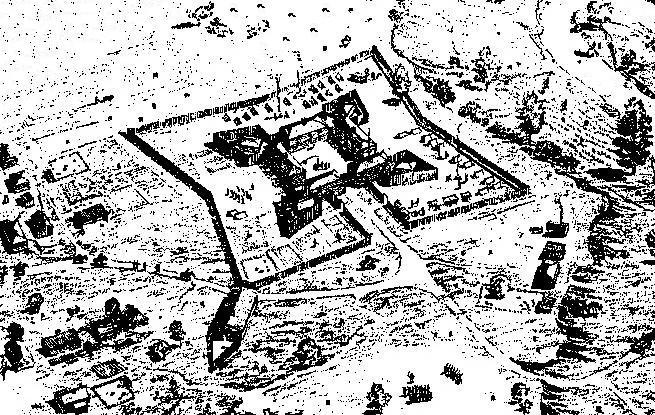

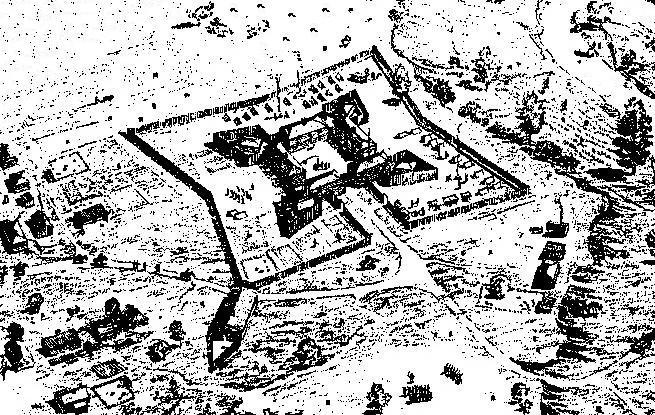

In the spring of 1753, Paul Marin de la Malgue was given command of a 2,000-man force of Troupes de la Marine and Indians. His orders were to protect the King's land in the Ohio Valley from the British. Marin followed the route that Céloron had mapped out four years earlier. Céloron, however, had limited the record of French claims to the burial of lead plates, whereas Marin constructed and garrisoned forts. He first constructed Fort Presque Isle on Lake Erie's south shore near

In the spring of 1753, Paul Marin de la Malgue was given command of a 2,000-man force of Troupes de la Marine and Indians. His orders were to protect the King's land in the Ohio Valley from the British. Marin followed the route that Céloron had mapped out four years earlier. Céloron, however, had limited the record of French claims to the burial of lead plates, whereas Marin constructed and garrisoned forts. He first constructed Fort Presque Isle on Lake Erie's south shore near Erie, Pennsylvania

Erie (; ) is a city on the south shore of Lake Erie and the county seat of Erie County, Pennsylvania, United States. Erie is the fifth largest city in Pennsylvania and the largest city in Northwestern Pennsylvania with a population of 94,831 ...

, and he had a road built to the headwaters of LeBoeuf Creek. He then constructed a second fort at Fort Le Boeuf in Waterford, Pennsylvania, designed to guard the headwaters of LeBoeuf Creek. As he moved south, he drove off or captured British traders, alarming both the British and the Iroquois. Tanaghrisson

Tanacharison (; c. 1700 – 4 October 1754), also called Tanaghrisson (), was a Native American leader who played a pivotal role in the beginning of the French and Indian War. He was known to European-Americans as the Half-King, a title als ...

was a chief of the Mingo

The Mingo people are an Iroquoian group of Native Americans, primarily Seneca and Cayuga, who migrated west from New York to the Ohio Country in the mid-18th century, and their descendants. Some Susquehannock survivors also joined them, and ...

Indians, who were remnants of Iroquois and other tribes who had been driven west by colonial expansion. He intensely disliked the French whom he accused of killing and eating his father. He traveled to Fort Le Boeuf and threatened the French with military action, which Marin contemptuously dismissed.Fowler, p. 31.

The Iroquois sent runners to the manor of William Johnson in upstate New York, who was the British Superintendent for Indian Affairs in the New York region and beyond. Johnson was known to the Iroquois as ''Warraghiggey'', meaning "he who does great things." He spoke their languages and had become a respected honorary member of the Iroquois Confederacy

The Iroquois ( or ), officially the Haudenosaunee ( meaning "people of the longhouse"), are an Iroquoian-speaking confederacy of First Nations peoples in northeast North America/ Turtle Island. They were known during the colonial years to ...

in the area, and he was made a colonel of the Iroquois in 1746; he was later commissioned as a colonel of the Western New York Militia.

The Indian representatives and Johnson met with Governor George Clinton and officials from some of the other American colonies at Albany, New York

Albany ( ) is the capital of the U.S. state of New York, also the seat and largest city of Albany County. Albany is on the west bank of the Hudson River, about south of its confluence with the Mohawk River, and about north of New York Cit ...

. Mohawk Chief Hendrick

Hendrick Theyanoguin (c. 1691 – September 8, 1755), whose name had several spelling variations, was a Mohawk leader and member of the Bear Clan. He resided at Canajoharie or the Upper Mohawk Castle in colonial New York.Sivertsen, Barbara J. ...

was the speaker of their tribal council, and he insisted that the British abide by their obligations and block French expansion. Clinton did not respond to his satisfaction, and Hendrick said that the "Covenant Chain

The Covenant Chain was a series of alliances and treaties developed during the seventeenth century, primarily between the Iroquois Confederacy (Haudenosaunee) and the British colonies of North America, with other Native American tribes added. Firs ...

" was broken, a long-standing friendly relationship between the Iroquois Confederacy and the British Crown.

Virginia's response

Governor Robert Dinwiddie of Virginia was an investor in the Ohio Company, which stood to lose money if the French held their claim. He ordered 21-year-old Major

Governor Robert Dinwiddie of Virginia was an investor in the Ohio Company, which stood to lose money if the French held their claim. He ordered 21-year-old Major George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of ...

(whose brother was another Ohio Company investor) of the Virginia Regiment to warn the French to leave Virginia territory in October 1753.Anderson (2000), pp. 42–43 Washington left with a small party, picking up Jacob Van Braam

Jacobus van Braam (b. Bergen op Zoom, in the Netherlands, 1 April 1729, d. 1 August 1792 Charleville, France) was a sword master and mercenary who trained the 19-year-old George Washington in 1751 or shortly thereafter. He was also retained by W ...

as an interpreter, Christopher Gist (a company surveyor working in the area), and a few Mingos led by Tanaghrisson. On December 12, Washington and his men reached Fort Le Boeuf.

Jacques Legardeur de Saint-Pierre

Jacques Legardeur de Saint-Pierre (October 24, 1701 - September 8, 1755) was a Canadian colonial military commander and explorer who held posts throughout North America in the 18th century, just before and during the French and Indian War.

Famil ...

succeeded Marin as commander of the French forces after Marin died on October 29, and he invited Washington to dine with him. Over dinner, Washington presented Saint-Pierre with the letter from Dinwiddie demanding an immediate French withdrawal from the Ohio Country. Saint-Pierre said, "As to the Summons you send me to retire, I do not think myself obliged to obey it."Fowler, p. 35. He told Washington that France's claim to the region was superior to that of the British, since René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle

René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle (; November 22, 1643 – March 19, 1687), was a 17th-century French explorer and fur trader in North America. He explored the Great Lakes region of the United States and Canada, the Mississippi River, ...

had explored the Ohio Country nearly a century earlier.Ellis, ''His Excellency George Washington'', p. 5.

Washington's party left Fort Le Boeuf early on December 16 and arrived in Williamsburg on January 16, 1754. He stated in his report, "The French had swept south",Fowler, p. 36. detailing the steps which they had taken to fortify the area, and their intention to fortify the confluence of the Allegheny and Monongahela rivers.

Course of war

Even before Washington returned, Dinwiddie had sent a company of 40 men under William Trent to that point where they began construction of a smallstockade

A stockade is an enclosure of palisades and tall walls, made of logs placed side by side vertically, with the tops sharpened as a defensive wall.

Etymology

''Stockade'' is derived from the French word ''estocade''. The French word was derived f ...

d fort in the early months of 1754. Governor Duquesne sent additional French forces under Claude-Pierre Pécaudy de Contrecœur Claude-Pierre Pécaudy de Contrecœur was an officer in the colonial regular troops ( troupes de la marine), seigneur, and member of the Legislative Council of New France. Born on December 28, 1705 at Contrecœur, Quebec, son of Francois-Antoine P� ...

to relieve Saint-Pierre during the same period, and Contrecœur led 500 men south from Fort Venango on April 5, 1754. These forces arrived at the fort on April 16, but Contrecœur generously allowed Trent's small company to withdraw. He purchased their construction tools to continue building what became Fort Duquesne

Fort Duquesne (, ; originally called ''Fort Du Quesne'') was a fort established by the French in 1754, at the confluence of the Allegheny and Monongahela rivers. It was later taken over by the British, and later the Americans, and developed a ...

.

Early engagements

Dinwiddie had ordered Washington to lead a larger force to assist Trent in his work, and Washington learned of Trent's retreat while he was en route. Mingo sachem Tanaghrisson had promised support to the British, so Washington continued toward Fort Duquesne and met with him. He then learned of a French scouting party in the area from a warrior sent by Tanaghrisson, so he added Tanaghrisson's dozen Mingo warriors to his own party. Washington's combined force of 52 ambushed 40 '' Canadiens'' (French colonists ofNew France

New France (french: Nouvelle-France) was the area colonized by France in North America, beginning with the exploration of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to Great Britain and Spa ...

) on the morning of May 28 in what became known as the Battle of Jumonville Glen

The Battle of Jumonville Glen, also known as the Jumonville affair, was the opening battle of the French and Indian War, fought on May 28, 1754, near present-day Hopwood and Uniontown in Fayette County, Pennsylvania. A company of provincial ...

. They killed many of the Canadiens, including their commanding officer Joseph Coulon de Jumonville, whose head was reportedly split open by Tanaghrisson with a tomahawk. Historian Fred Anderson suggests that Tanaghrisson was acting to gain the support of the British and to regain authority over his own people. They had been inclined to support the French, with whom they had long trading relationships. One of Tanaghrisson's men told Contrecoeur that Jumonville had been killed by British musket fire.Anderson (2000), pp. 51–59. Historians generally consider the Battle of Jumonville Glen as the opening battle of the French and Indian War in North America, and the start of hostilities in the Ohio valley.

Battle of Fort Necessity

The Battle of Fort Necessity, also known as the Battle of the Great Meadows, took place on July 3, 1754, in what is now Farmington in Fayette County, Pennsylvania. The engagement, along with the May 28 skirmish known as the Battle of Jumonvill ...

on July 3. Washington surrendered and negotiated a withdrawal under arms. One of his men reported that the Canadian force was accompanied by Shawnee

The Shawnee are an Algonquian-speaking indigenous people of the Northeastern Woodlands. In the 17th century they lived in Pennsylvania, and in the 18th century they were in Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana and Illinois, with some bands in Kentucky a ...

, Delaware

Delaware ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States, bordering Maryland to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and New Jersey and the Atlantic Ocean to its east. The state takes its name from the adjacent ...

, and Mingo warriors—just those whom Tanaghrisson was seeking to influence.Anderson (2000), pp. 59–65.

News of the two battles reached England in August. After several months of negotiations, the government of the Duke of Newcastle

Thomas Pelham-Holles, 1st Duke of Newcastle upon Tyne and 1st Duke of Newcastle-under-Lyne, (21 July 169317 November 1768) was a British Whig statesman who served as the 4th and 6th Prime Minister of Great Britain, his official life extended ...

decided to send an army expedition the following year to dislodge the French.Fowler, p. 52. They chose Major General Edward Braddock

Major-General Edward Braddock (January 1695 – 13 July 1755) was a British officer and commander-in-chief for the Thirteen Colonies during the start of the French and Indian War (1754–1763), the North American front of what is known in Europ ...

to lead the expedition. Word of the British military plans leaked to France well before Braddock's departure for North America. In response, King Louis XV dispatched six regiments to New France under the command of Baron Dieskau in 1755. The British sent out their fleet in February 1755, intending to blockade French ports, but the French fleet had already sailed. Admiral Edward Hawke

Edward Hawke, 1st Baron Hawke, KB, PC (21 February 1705 – 17 October 1781), of Scarthingwell Hall in the parish of Towton, near Tadcaster, Yorkshire, was a Royal Navy officer. As captain of the third-rate , he took part in the Battle of T ...

detached a fast squadron to North America in an attempt to intercept them.

In a second British action, Admiral Edward Boscawen fired on the French ship ''Alcide'' on June 8, 1755, capturing her and two troop ships.Fowler, pp. 74–75. The British harassed French shipping throughout 1755, seizing ships and capturing seamen. These actions contributed to the eventual formal declarations of war in spring 1756.Fowler, p. 98.

An early important political response to the opening of hostilities was the convening of the

In a second British action, Admiral Edward Boscawen fired on the French ship ''Alcide'' on June 8, 1755, capturing her and two troop ships.Fowler, pp. 74–75. The British harassed French shipping throughout 1755, seizing ships and capturing seamen. These actions contributed to the eventual formal declarations of war in spring 1756.Fowler, p. 98.

An early important political response to the opening of hostilities was the convening of the Albany Congress

The Albany Congress (June 19 – July 11, 1754), also known as the Albany Convention of 1754, was a meeting of representatives sent by the legislatures of seven of the 13 British colonies in British America: Connecticut, Maryland, Massachusetts, ...

in June and July, 1754. The goal of the congress was to formalize a unified front in trade and negotiations with the Indians, since the allegiance of the various tribes and nations was seen to be pivotal in the war that was unfolding. The plan that the delegates agreed to was neither ratified by the colonial legislatures nor approved by the Crown. Nevertheless, the format of the congress and many specifics of the plan became the prototype for confederation during the War of Independence

This is a list of wars of independence (also called liberation wars). These wars may or may not have been successful in achieving a goal of independence.

List

See also

* Lists of active separatist movements

* List of civil wars

* List of ...

.

British campaigns, 1755

The British formed an aggressive plan of operations for 1755. General Braddock was to lead the expedition to Fort Duquesne, while Massachusetts governor William Shirley was given the task of fortifyingFort Oswego

Fort Oswego was an 18th-century trading post in the Great Lakes region in North America, which became the site of a battle between French and British forces in 1756 during the French and Indian War. The fort was established in 1727 on the orders o ...

and attacking Fort Niagara

Fort Niagara is a fortification originally built by New France to protect its interests in North America, specifically control of access between the Niagara River and Lake Ontario, the easternmost of the Great Lakes. The fort is on the river's e ...

. Sir William Johnson

Sir William Johnson, 1st Baronet of New York ( – 11 July 1774), was a British Army officer and colonial administrator from Ireland. As a young man, Johnson moved to the Province of New York to manage an estate purchased by his uncle, Royal Na ...

was to capture Fort St. Frédéric

A fortification is a military construction or building designed for the defense of territories in warfare, and is also used to establish rule in a region during peacetime. The term is derived from Latin ''fortis'' ("strong") and ''facere'' ...

at Crown Point, New York, and Lieutenant Colonel Robert Monckton was to capture Fort Beauséjour to the east on the frontier between Nova Scotia and Acadia.

Braddock led about 1,500 army troops and provincial militia on the Braddock expedition in June 1755 to take Fort Duquesne, with George Washington as one of his aides. The expedition was a disaster. It was attacked by French regulars, Canadian Militiamen, and Indian warriors ambushing them from hiding places up in trees and behind logs, and Braddock called for a retreat. He was killed and approximately 1,000 British soldiers were killed or injured. The remaining 500 British troops retreated to Virginia, led by Washington. Washington and

Braddock led about 1,500 army troops and provincial militia on the Braddock expedition in June 1755 to take Fort Duquesne, with George Washington as one of his aides. The expedition was a disaster. It was attacked by French regulars, Canadian Militiamen, and Indian warriors ambushing them from hiding places up in trees and behind logs, and Braddock called for a retreat. He was killed and approximately 1,000 British soldiers were killed or injured. The remaining 500 British troops retreated to Virginia, led by Washington. Washington and Thomas Gage

General Thomas Gage (10 March 1718/192 April 1787) was a British Army general officer and colonial official best known for his many years of service in North America, including his role as British commander-in-chief in the early days of t ...

played key roles in organizing the retreat—two future opponents in the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

.

The British government initiated a plan to increase their military capability in preparation for war following news of Braddock's defeat and the start of parliament's session in November 1755. Among the early legislative measures were the Recruiting Act 1756, the Commissions to Foreign Protestants Act 1756 for the Royal American Regiment, the Navigation Act 1756, and the Continuance of Acts 1756. England passed the Naval Prize Act 1756 following the proclamation of war on May 17 to allow the capture of ships and establish privateering.

The French acquired a copy of the British war plans, including the activities of Shirley and Johnson. Shirley's efforts to fortify Oswego were bogged down in logistical difficulties, exacerbated by his inexperience in managing large expeditions. In conjunction, he was made aware that the French were massing for an attack on Fort Oswego in his absence when he planned to attack Fort Niagara. As a response, he left garrisons at Oswego, Fort Bull Fort Bull was located at the Oneida Carry in British North America (now New York, United States) during the French and Indian War.

On October 29, 1755 Governor William Shirley ordered Captain Mark Petrie to take the men under his command and to bui ...

, and Fort Williams, the last two located on the Oneida Carry

The Oneida Carry was an important link in the main 18th century trade route between the Atlantic seaboard of North America and interior of the continent. From Schenectady, near Albany, New York on the Hudson River, cargo would be carried upstream ...

between the Mohawk River

The Mohawk River is a U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map accessed October 3, 2011 river in the U.S. state of New York. It is the largest tributary of the Hudson River. The Mohawk ...

and Wood Creek at Rome, New York

Rome is a city in Oneida County, New York, United States, located in the central part of the state. The population was 32,127 at the 2020 census. Rome is one of two principal cities in the Utica–Rome Metropolitan Statistical Area, which l ...

. Supplies were cached at Fort Bull for use in the projected attack on Niagara.

Johnson's expedition was better organized than Shirley's, which was noticed by New France's governor the Marquis de Vaudreuil. Vaudreuil had been concerned about the extended supply line to the forts on the Ohio, and he had sent Baron Dieskau to lead the defenses at Frontenac against Shirley's expected attack. Vaudreuil saw Johnson as the larger threat and sent Dieskau to Fort St. Frédéric to meet that threat. Dieskau planned to attack the British encampment at Fort Edward at the upper end of navigation on the Hudson River

The Hudson River is a river that flows from north to south primarily through eastern New York. It originates in the Adirondack Mountains of Upstate New York and flows southward through the Hudson Valley to the New York Harbor between Ne ...

, but Johnson had strongly fortified it, and Dieskau's Indian support was reluctant to attack. The two forces finally met in the bloody Battle of Lake George between Fort Edward and Fort William Henry. The battle ended inconclusively, with both sides withdrawing from the field. Johnson's advance stopped at Fort William Henry, and the French withdrew to Ticonderoga Point, where they began the construction of Fort Carillon

Fort Carillon, presently known as Fort Ticonderoga, was constructed by Pierre de Rigaud de Vaudreuil, Governor of French Canada, to protect Lake Champlain from a British invasion. Situated on the lake some south of Fort Saint Frédéric, it ...

(later renamed Fort Ticonderoga after the British captured it in 1759).

Colonel Monckton captured Fort Beauséjour in June 1755 in the sole British success that year, cutting off the French Fortress Louisbourg

The Fortress of Louisbourg (french: Forteresse de Louisbourg) is a National Historic Site and the location of a one-quarter partial reconstruction of an 18th-century French fortress at Louisbourg on Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia. Its two s ...

from land-based reinforcements. To cut vital supplies to Louisbourg, Nova Scotia's Governor Charles Lawrence ordered the deportation of the French-speaking Acadian

The Acadians (french: Acadiens , ) are an ethnic group descended from the French who settled in the New France colony of Acadia during the 17th and 18th centuries. Most Acadians live in the region of Acadia, as it is the region where the desc ...

population from the area. Monckton's forces, including companies of Rogers' Rangers

Rogers' Rangers was a company of soldiers from the Province of New Hampshire raised by Major Robert Rogers and attached to the British Army during the Seven Years' War ( French and Indian War). The unit was quickly adopted into the British arm ...

, forcibly removed thousands of Acadians, chasing down many who resisted and sometimes committing atrocities. Cutting off supplies to Louisbourg led to its demise. The Acadian resistance was sometimes quite stiff, in concert with Indian allies including the Mi'kmaq, with ongoing frontier raids against Dartmouth and Lunenburg, among others. The only clashes of any size were at Petitcodiac in 1755 and at Bloody Creek near Annapolis Royal

Annapolis Royal, formerly known as Port Royal, is a town located in the western part of Annapolis County, Nova Scotia, Canada.

Today's Annapolis Royal is the second French settlement known by the same name and should not be confused with the ne ...

in 1757, other than the campaigns to expel the Acadians ranging around the Bay of Fundy