Frederick Russell Burnham on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Frederick Russell Burnham DSO (May 11, 1861 – September 1, 1947) was an American

Burnham was born on May 11, 1861, on a

Burnham was born on May 11, 1861, on a  Holmes had served under

Holmes had served under

Burnham, along with his wife and son, was trekking the 1,000 miles (1,609 km) north from Durban to Matabeleland with an American

Burnham, along with his wife and son, was trekking the 1,000 miles (1,609 km) north from Durban to Matabeleland with an American

Jameson sent a column of soldiers under Major Patrick Forbes to locate and capture Lobengula. The column camped on the south bank of the

Jameson sent a column of soldiers under Major Patrick Forbes to locate and capture Lobengula. The column camped on the south bank of the

The turning point in the war came when Burnham and Bonar Armstrong, a company native commissioner, found their way through the Matopos Hills to a

The turning point in the war came when Burnham and Bonar Armstrong, a company native commissioner, found their way through the Matopos Hills to a

The

The

Burnham was already a celebrated scout when he first befriended Baden-Powell during the Second Matabele War, but the backgrounds of these two scouts was as strange a contrast as it is possible to imagine. From his youth on the open plains, Burnham's earliest playmates were Sioux Indian boys and their ambitions pointed to excelling in the lore and arts of the trail and together they dreamed of some day becoming great scouts. When Burnham was a teenager he supported himself by hunting game and making long rides for Western Union through the California deserts, his early mentors were wise old scouts of the American West, and by 19 he was a seasoned scout chasing and being chased by Apache. The British scout he would later befriend and serve with in Matabeleland, Baden-Powell, was born in London and had graduated from Charterhouse, one of England's most famous public schools. Baden-Powell developed an ambition to become a scout at an early age. He passed an exam that gave him an immediate commission into the

Burnham was already a celebrated scout when he first befriended Baden-Powell during the Second Matabele War, but the backgrounds of these two scouts was as strange a contrast as it is possible to imagine. From his youth on the open plains, Burnham's earliest playmates were Sioux Indian boys and their ambitions pointed to excelling in the lore and arts of the trail and together they dreamed of some day becoming great scouts. When Burnham was a teenager he supported himself by hunting game and making long rides for Western Union through the California deserts, his early mentors were wise old scouts of the American West, and by 19 he was a seasoned scout chasing and being chased by Apache. The British scout he would later befriend and serve with in Matabeleland, Baden-Powell, was born in London and had graduated from Charterhouse, one of England's most famous public schools. Baden-Powell developed an ambition to become a scout at an early age. He passed an exam that gave him an immediate commission into the  Burnham later became close friends with others involved in the Scouting movement in the United States, such as Theodore Roosevelt, the Chief Scout Citizen, and

Burnham later became close friends with others involved in the Scouting movement in the United States, such as Theodore Roosevelt, the Chief Scout Citizen, and

After convalescing, Burnham became the London office manager for the Wa Syndicate, a commercial body with interests in the Gold Coast and neighboring territories in West Africa. He led the Wa Syndicate's 1901 expedition through the Gold Coast and the Upper Volta, looking for minerals and ways to improve river navigation. Between 1902 and 1904 he was employed by the East Africa Syndicate, for which he led a vast mineral prospecting expedition in the

After convalescing, Burnham became the London office manager for the Wa Syndicate, a commercial body with interests in the Gold Coast and neighboring territories in West Africa. He led the Wa Syndicate's 1901 expedition through the Gold Coast and the Upper Volta, looking for minerals and ways to improve river navigation. Between 1902 and 1904 he was employed by the East Africa Syndicate, for which he led a vast mineral prospecting expedition in the

Although Burnham had lived all over the world, he never had a great deal of wealth to show for his efforts. It was not until he returned to California, the place of his youth, that he found great affluence. In November 1923, he struck oil in Dominguez Hills (mountain range), Dominguez Hills, near Carson, California. In a field that covered just two square miles, over 150 wells from Unocal Corporation, Union Oil were soon producing 37,000 barrels a day, with 10,000 barrels a day going to the Burnham Exploration Company, a syndicate formed in 1919 between Frederick Burnham, his son Roderick, John Hayes Hammond, and his son Harris Hammond. In the first 10 years of operation, the Burnham Exploration Company paid out $10.2 million in dividends. The spot where Burnham found oil was land where "as a small boy he used to graze cattle, and shoot game which he sold to the neighboring mining districts to support his widowed mother and infant brother." Many years after the oil was depleted, the land near the Dominguez field was re-developed and became the site of the California State University, Dominguez Hills. In 2010, Occidental Petroleum Corporation expressed interest in redeveloping the former Dominguez oil field using modern extraction technologies.

Although Burnham had lived all over the world, he never had a great deal of wealth to show for his efforts. It was not until he returned to California, the place of his youth, that he found great affluence. In November 1923, he struck oil in Dominguez Hills (mountain range), Dominguez Hills, near Carson, California. In a field that covered just two square miles, over 150 wells from Unocal Corporation, Union Oil were soon producing 37,000 barrels a day, with 10,000 barrels a day going to the Burnham Exploration Company, a syndicate formed in 1919 between Frederick Burnham, his son Roderick, John Hayes Hammond, and his son Harris Hammond. In the first 10 years of operation, the Burnham Exploration Company paid out $10.2 million in dividends. The spot where Burnham found oil was land where "as a small boy he used to graze cattle, and shoot game which he sold to the neighboring mining districts to support his widowed mother and infant brother." Many years after the oil was depleted, the land near the Dominguez field was re-developed and became the site of the California State University, Dominguez Hills. In 2010, Occidental Petroleum Corporation expressed interest in redeveloping the former Dominguez oil field using modern extraction technologies.

An avid conservation movement, conservationist and hunter, Burnham supported the early conservation programs of his friends Theodore Roosevelt and Gifford Pinchot. He and his associate John Hayes Hammond led novel game expeditions to Africa with the goal of finding large animals such as Giant Eland, hippopotamus, zebra, and various bird species that might be bred in the United States and become game for future American sportsmen. Burnham, Hammond, and Duquesne appeared several times before the House Committee on Agriculture to ask for help in importing large African animals. In 1914, he helped establish the Wild Life Protective League of America, Department of Southern California, and served as its first Secretary.

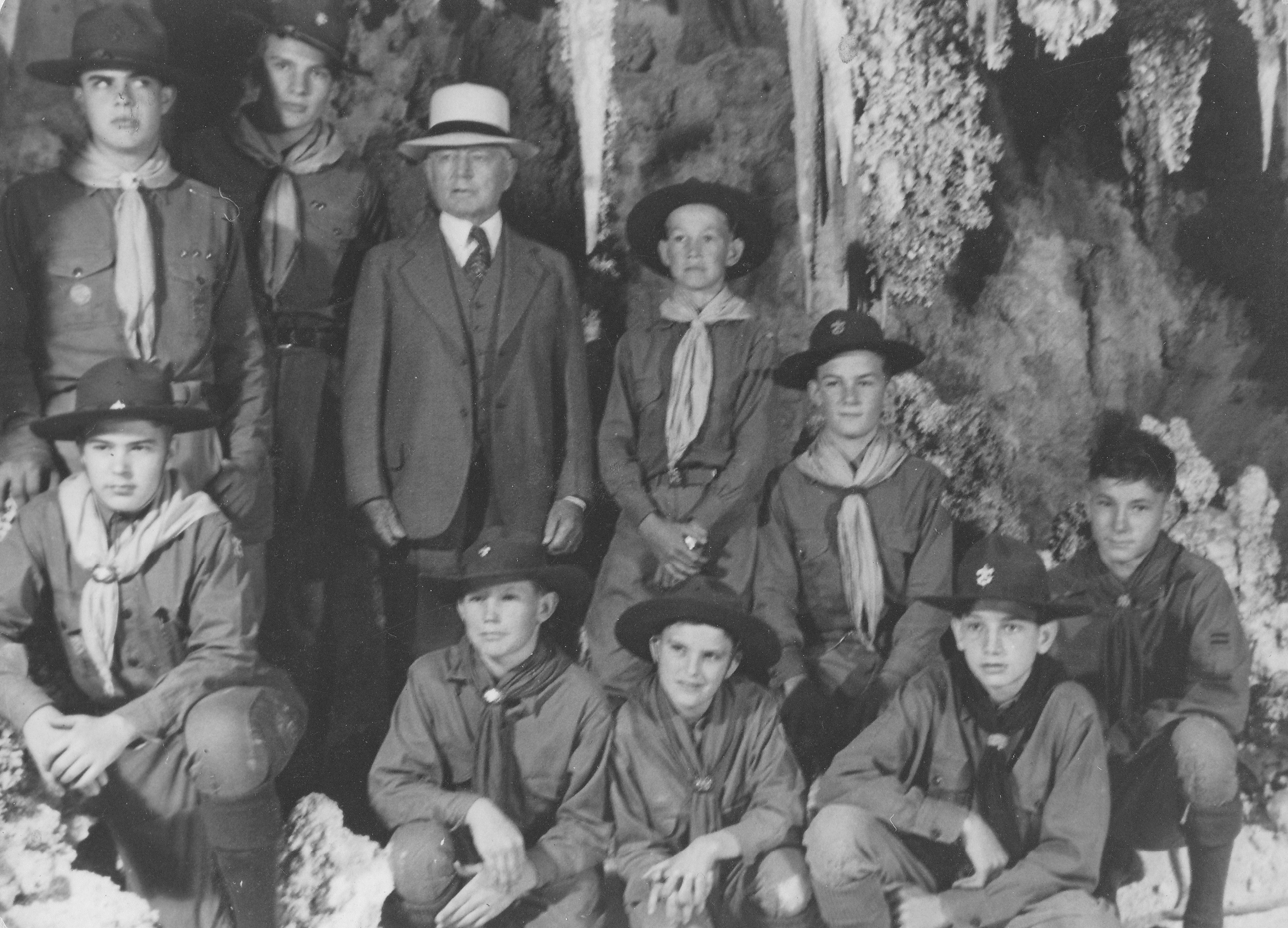

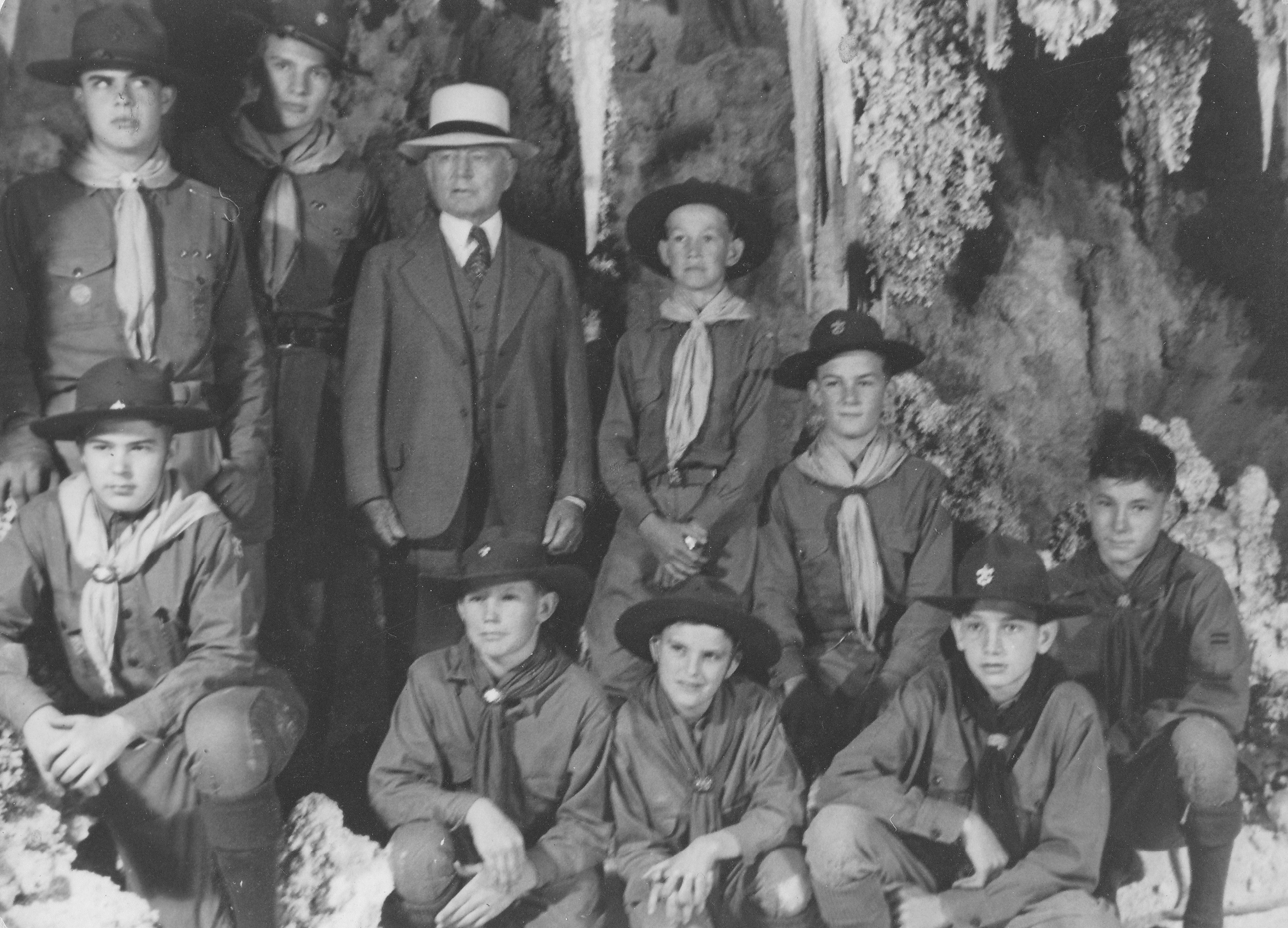

In his later years, Burnham filled various public offices and also served as a member of the Boone and Crockett Club of New York, and as a founding member of the American Committee for International Wildlife Protection (now a committee of the World Conservation Union). He was one of the original members of the first California State Parks Commission (serving from 1927 to 1934), a founding member of the Save the Redwoods League, president of the Southwest Museum of Los Angeles from 1938 until 1940, and he served as both the Honorary President of the Scouting in Arizona, Arizona Boy Scouts and as a regional executive for the BSA throughout the 1940s until his death in 1947.

In 1936, Burnham enlisted the Arizona Boy Scouts in a campaign to save the Desert Bighorn Sheep from probable extinction. Several other prominent Arizonans and environmental groups joined the movement and a "save the bighorns" poster contest was started in schools throughout the state. Burnham provided prizes and appeared in store windows from one end of Arizona to the other. The contest-winning bighorn emblem was made into neckerchief slides for the 10,000 Boy Scouts, and talks and dramatizations were given at school assemblies and on radio. On January 18, 1939, over 1.5 million acres (6,100 km2) were set aside in Arizona to establish the Kofa National Wildlife Refuge and the Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge, and Burnham gave the dedication speech.

An avid conservation movement, conservationist and hunter, Burnham supported the early conservation programs of his friends Theodore Roosevelt and Gifford Pinchot. He and his associate John Hayes Hammond led novel game expeditions to Africa with the goal of finding large animals such as Giant Eland, hippopotamus, zebra, and various bird species that might be bred in the United States and become game for future American sportsmen. Burnham, Hammond, and Duquesne appeared several times before the House Committee on Agriculture to ask for help in importing large African animals. In 1914, he helped establish the Wild Life Protective League of America, Department of Southern California, and served as its first Secretary.

In his later years, Burnham filled various public offices and also served as a member of the Boone and Crockett Club of New York, and as a founding member of the American Committee for International Wildlife Protection (now a committee of the World Conservation Union). He was one of the original members of the first California State Parks Commission (serving from 1927 to 1934), a founding member of the Save the Redwoods League, president of the Southwest Museum of Los Angeles from 1938 until 1940, and he served as both the Honorary President of the Scouting in Arizona, Arizona Boy Scouts and as a regional executive for the BSA throughout the 1940s until his death in 1947.

In 1936, Burnham enlisted the Arizona Boy Scouts in a campaign to save the Desert Bighorn Sheep from probable extinction. Several other prominent Arizonans and environmental groups joined the movement and a "save the bighorns" poster contest was started in schools throughout the state. Burnham provided prizes and appeared in store windows from one end of Arizona to the other. The contest-winning bighorn emblem was made into neckerchief slides for the 10,000 Boy Scouts, and talks and dramatizations were given at school assemblies and on radio. On January 18, 1939, over 1.5 million acres (6,100 km2) were set aside in Arizona to establish the Kofa National Wildlife Refuge and the Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge, and Burnham gave the dedication speech.

Burnham's wife of 55 years, Blanche (February 25, 1862 – December 22, 1939) of Nevada, Iowa, accompanied him in very primitive conditions through many travels in both the Southwest United States and southern Africa. Together they had three children, all of whom spent their early youth in Africa. In the early years, she watched over the children and the pack animals, and she always kept a rifle nearby. In the dark of night, she used her rifle many times against lions and hyena and, during the Siege of Bulawayo, against Matabele warriors. Several members of the Blick family joined the Burnhams in Rhodesia, moved with them to England, and returned to the United States with the Burnhams to live near Three Rivers, California. When Burnham Exploration Company struck it rich in 1923, the Burnhams moved to a mansion built by Pasadena architect Joseph Blick, his brother-in-law, in a new housing development then known as Hollywoodland (a name later shortened to "Hollywood") and took many trips around the world in high style. In 1939, Blanche suffered a stroke. She died a month later and was buried in the Three Rivers Cemetery.

Burnham's wife of 55 years, Blanche (February 25, 1862 – December 22, 1939) of Nevada, Iowa, accompanied him in very primitive conditions through many travels in both the Southwest United States and southern Africa. Together they had three children, all of whom spent their early youth in Africa. In the early years, she watched over the children and the pack animals, and she always kept a rifle nearby. In the dark of night, she used her rifle many times against lions and hyena and, during the Siege of Bulawayo, against Matabele warriors. Several members of the Blick family joined the Burnhams in Rhodesia, moved with them to England, and returned to the United States with the Burnhams to live near Three Rivers, California. When Burnham Exploration Company struck it rich in 1923, the Burnhams moved to a mansion built by Pasadena architect Joseph Blick, his brother-in-law, in a new housing development then known as Hollywoodland (a name later shortened to "Hollywood") and took many trips around the world in high style. In 1939, Blanche suffered a stroke. She died a month later and was buried in the Three Rivers Cemetery.

Burnham's first son, Roderick (August 22, 1886 – July 2, 1976), was born in Pasadena, California, but accompanied the family to Africa and learned the Matabele language, Northern Ndebele language, Sindebele. He went to boarding school in France in 1895, and then to a military school in England the following year. In 1898, he went to Skagway, Alaska with his father, and returned to Pasadena the next year. In 1904, he attended the University of California, Berkeley, joined the football team, but left Berkeley after a dispute with his coach. In 1905–08, he went to the University of Arizona, joined the Delta Kappa Epsilon fraternity, played the position of running back, and became the captain of the football team. He attended the Michigan School of Mines (now Michigan Technological University) in 1910, became a geologist, and worked for Union Oil as Manager of Lands and Foreign Exploration helping to develop the first wells in Mexico and Venezuela. He took time off from his job to serve in the U.S. Army in World War I and fought in France. He and his father became minority owners of the Burnham Exploration Company, incorporated in 1919 by Harris Hays Hammond (the son of John Hays Hammond, Sr). In 1930, he and Paramount Pictures founder W. W. Hodkinson started the Central American Aviation Corporation, the first airline in Guatemala.

Nada (May 1894 – May 19, 1896), Burnham's daughter, was the first white child born in Bulawayo; she died of fever and starvation during the town's siege. She was buried three days later in the town's Pioneer Cemetery, plot No. 144. Nada is the Zulu language, Zulu word for Agapanthus africanus, lily and she was named after the heroine in Sir H. Rider Haggard's Zulu tale, ''Nada the Lily (1892)''. Three of Haggard's books are dedicated to Burnham's daughter, Nada: ''The Wizard'' (1896), ''Elissa: The Doom of Zimbabwe'' (1899), and ''Black Heart and White Heart: A Zulu Idyll'' (1900).

Burnham's youngest son, Bruce B. Burnham (1897 – October 3, 1905), was staying with his parents in London when he accidentally drowned in the River Thames. His brother, Roderick, was in California the night Bruce died, yet claimed to know from a dream exactly what had happened. Roderick awoke screaming and rushed to tell his grandmother about his nightmare. The next morning, a cable arrived with the news of Bruce's death.

Burnham's first son, Roderick (August 22, 1886 – July 2, 1976), was born in Pasadena, California, but accompanied the family to Africa and learned the Matabele language, Northern Ndebele language, Sindebele. He went to boarding school in France in 1895, and then to a military school in England the following year. In 1898, he went to Skagway, Alaska with his father, and returned to Pasadena the next year. In 1904, he attended the University of California, Berkeley, joined the football team, but left Berkeley after a dispute with his coach. In 1905–08, he went to the University of Arizona, joined the Delta Kappa Epsilon fraternity, played the position of running back, and became the captain of the football team. He attended the Michigan School of Mines (now Michigan Technological University) in 1910, became a geologist, and worked for Union Oil as Manager of Lands and Foreign Exploration helping to develop the first wells in Mexico and Venezuela. He took time off from his job to serve in the U.S. Army in World War I and fought in France. He and his father became minority owners of the Burnham Exploration Company, incorporated in 1919 by Harris Hays Hammond (the son of John Hays Hammond, Sr). In 1930, he and Paramount Pictures founder W. W. Hodkinson started the Central American Aviation Corporation, the first airline in Guatemala.

Nada (May 1894 – May 19, 1896), Burnham's daughter, was the first white child born in Bulawayo; she died of fever and starvation during the town's siege. She was buried three days later in the town's Pioneer Cemetery, plot No. 144. Nada is the Zulu language, Zulu word for Agapanthus africanus, lily and she was named after the heroine in Sir H. Rider Haggard's Zulu tale, ''Nada the Lily (1892)''. Three of Haggard's books are dedicated to Burnham's daughter, Nada: ''The Wizard'' (1896), ''Elissa: The Doom of Zimbabwe'' (1899), and ''Black Heart and White Heart: A Zulu Idyll'' (1900).

Burnham's youngest son, Bruce B. Burnham (1897 – October 3, 1905), was staying with his parents in London when he accidentally drowned in the River Thames. His brother, Roderick, was in California the night Bruce died, yet claimed to know from a dream exactly what had happened. Roderick awoke screaming and rushed to tell his grandmother about his nightmare. The next morning, a cable arrived with the news of Bruce's death.

His brother Howard Burnham (1870–1918), born shortly before the family moved to Los Angeles, lost one leg at the age of 14 and suffered from tuberculosis. During his teenage years he lived with Fred in California and learned from his brother the art of Scoutcraft, how to shoot, and how to ride the range, all in spite of his wooden leg. Howard moved to Africa, became a mining engineer in the Johannesburg gold mines, and later wrote a text book on ''Modern Mine Valuation''. He traveled the world and for a time teamed up with Fred on Yaqui River irrigation project in Mexico. During World War I, Howard worked as a spy for the French government, operating behind enemy lines in southwest Germany. Throughout the war he used his wooden leg to conceal tools he needed for spying. From his death bed, Howard returned to France via Switzerland and shared his vital data and secrets with the French government: the Germans were not opening a new front in the Alps and there was no need to move allied troops away from the Western Front (World War I), Western Front. Howard was buried at Cannes, France, leaving behind his wife and four children. He had been named after his second cousin, Lieutenant Howard Mather Burnham who was killed in action in the American Civil War.

Burnham's first cousin Charles Edward Russell (1860–1941) was a journalist and politician and also a founder of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). The author of a number of books of biography and social commentary Russell won a Pulitzer Prize in 1928 for his biography: ''The American Orchestra and Theodore Thomas (conductor), Theodore Thomas''.

In 1943, at 83 years of age, Burnham married his much younger typist, Ilo K. Willits Burnham (June 20, 1894 – August 28, 1982). The couple sold their mansion and moved to Santa Barbara in 1946.

Burnham was a descendant of Thomas Burnham (1617–1688) of Hartford, Connecticut, the first American ancestor of a large number of Burnhams. The descendants of Thomas Burnham have been noted in every American war, including the French and Indian War.

His brother Howard Burnham (1870–1918), born shortly before the family moved to Los Angeles, lost one leg at the age of 14 and suffered from tuberculosis. During his teenage years he lived with Fred in California and learned from his brother the art of Scoutcraft, how to shoot, and how to ride the range, all in spite of his wooden leg. Howard moved to Africa, became a mining engineer in the Johannesburg gold mines, and later wrote a text book on ''Modern Mine Valuation''. He traveled the world and for a time teamed up with Fred on Yaqui River irrigation project in Mexico. During World War I, Howard worked as a spy for the French government, operating behind enemy lines in southwest Germany. Throughout the war he used his wooden leg to conceal tools he needed for spying. From his death bed, Howard returned to France via Switzerland and shared his vital data and secrets with the French government: the Germans were not opening a new front in the Alps and there was no need to move allied troops away from the Western Front (World War I), Western Front. Howard was buried at Cannes, France, leaving behind his wife and four children. He had been named after his second cousin, Lieutenant Howard Mather Burnham who was killed in action in the American Civil War.

Burnham's first cousin Charles Edward Russell (1860–1941) was a journalist and politician and also a founder of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). The author of a number of books of biography and social commentary Russell won a Pulitzer Prize in 1928 for his biography: ''The American Orchestra and Theodore Thomas (conductor), Theodore Thomas''.

In 1943, at 83 years of age, Burnham married his much younger typist, Ilo K. Willits Burnham (June 20, 1894 – August 28, 1982). The couple sold their mansion and moved to Santa Barbara in 1946.

Burnham was a descendant of Thomas Burnham (1617–1688) of Hartford, Connecticut, the first American ancestor of a large number of Burnhams. The descendants of Thomas Burnham have been noted in every American war, including the French and Indian War.

Burnham authored the following works:

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

Burnham authored the following works:

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

Major Burnham on Pine Tree Web Scouting site

*

', 35 min. silent b&w video. Footage shot in South Africa, Rhodesia and eastern Africa during a family trip. Smithsonian Institution archives. call# 85.4.1; AF–85.4.1 (1929) *hdl:10079/fa/mssa.ms.0115, Frederick Russell Burnham Papers (MS 115). Manuscripts and Archives, Yale University Library. A large collection of Burnham's documents: Correspondence, 1864–1947. Subject Files, 1890–1947. Writings, 1893–1946. Personal and Family Papers, 1879–1951. Photographs, ca. 1893–1924.

Frederick Russell Burnham Papers, 1879–1979, Hoover Institution Library and Archives, Stanford University.

Another large collection of Burnham's documents: Correspondence, speeches and writings, clippings, other printed matter, photographs, and memorabilia, relating to the Matabele Wars of 1893 and 1896 in Rhodesia, the Second Boer War, exploration expeditions in Africa, and gold mining in Alaska during the Klondike gold rush. {{DEFAULTSORT:Burnham, Frederick Russell 1861 births 1947 deaths American activists American explorers American mercenaries American people of English descent American pioneers Apache Wars British colonial army officers British military personnel of the Second Boer War Companions of the Distinguished Service Order Cowboys Military personnel from Minnesota Military snipers People from Bulawayo People from Mankato, Minnesota People from Santa Barbara, California People from the Municipality of Skagway Borough, Alaska People of the First Matabele War People of the Klondike Gold Rush People of the Second Matabele War Scouting pioneers

scout

Scout may refer to:

Youth movement

*Scout (Scouting), a child, usually 10–18 years of age, participating in the worldwide Scouting movement

** Scouts (The Scout Association), section for 10-14 year olds in the United Kingdom

**Scouts BSA, secti ...

and world-traveling adventurer. He is known for his service to the British South Africa Company

The British South Africa Company (BSAC or BSACo) was chartered in 1889 following the amalgamation of Cecil Rhodes' Central Search Association and the London-based Exploring Company Ltd, which had originally competed to capitalize on the expect ...

and to the British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurkha ...

in colonial Africa

Colonial or The Colonial may refer to:

* Colonial, of, relating to, or characteristic of a colony or colony (biology)

Architecture

* American colonial architecture

* French Colonial

* Spanish Colonial architecture

Automobiles

* Colonial (1920 a ...

, and for teaching woodcraft

The term woodcraft — or woodlore — denotes bushcraft skills and experience in matters relating to living and thriving in the woods—such as hunting, fishing, and camping—whether on a short- or long-term basis. Traditionally, woodcraft p ...

to Robert Baden-Powell

Lieutenant-General Robert Stephenson Smyth Baden-Powell, 1st Baron Baden-Powell, ( ; (Commonly pronounced by others as ) 22 February 1857 – 8 January 1941) was a British Army officer, writer, founder and first Chief Scout of the wor ...

in Rhodesia

Rhodesia (, ), officially from 1970 the Republic of Rhodesia, was an unrecognised state in Southern Africa from 1965 to 1979, equivalent in territory to modern Zimbabwe. Rhodesia was the ''de facto'' successor state to the British colony of So ...

. He helped inspire the founding of the international Scouting Movement

Scouting, also known as the Scout Movement, is a worldwide youth movement employing the Scout method, a program of informal education with an emphasis on practical outdoor activities, including camping, woodcraft, aquatics, hiking, backpacking, ...

.

Burnham was born on a Dakota Sioux

The Dakota (pronounced , Dakota language: ''Dakȟóta/Dakhóta'') are a Native American tribe and First Nations band government in North America. They compose two of the three main subcultures of the Sioux people, and are typically divided into ...

Indian reservation

An Indian reservation is an area of land held and governed by a federally recognized Native American tribal nation whose government is accountable to the United States Bureau of Indian Affairs and not to the state government in which it ...

in Minnesota, in the small village of Tivoli near the city of Mankato, there he learned the ways of American Indians as a boy. By the age of 14, he was supporting himself in California, while also learning scouting from some of the last of the cowboys and frontiersmen of the American Southwest

The Southwestern United States, also known as the American Southwest or simply the Southwest, is a geographic and cultural region of the United States that generally includes Arizona, New Mexico, and adjacent portions of California, Colorado ...

. Burnham had little formal education, never finishing high school. After moving to the Arizona Territory

The Territory of Arizona (also known as Arizona Territory) was a territory of the United States that existed from February 24, 1863, until February 14, 1912, when the remaining extent of the territory was admitted to the Union as the state o ...

in the early 1880s, he was drawn into the Pleasant Valley War

The Pleasant Valley War, sometimes called the Tonto Basin Feud, or Tonto Basin War, or Tewksbury-Graham Feud, was a range war fought in Pleasant Valley, Arizona in the years 1882–1892. The conflict involved two feuding families, the Grahams an ...

, a feud between families of ranchers and sheepherders. He escaped and later worked as a civilian tracker for the United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, ...

in the Apache Wars

The Apache Wars were a series of armed conflicts between the United States Army and various Apache tribal confederations fought in the southwest between 1849 and 1886, though minor hostilities continued until as late as 1924. After the Mexi ...

. Feeling the need for new adventures, Burnham took his family to southern Africa in 1893, seeing Cecil Rhodes

Cecil John Rhodes (5 July 1853 – 26 March 1902) was a British mining magnate and politician in southern Africa who served as Prime Minister of the Cape Colony from 1890 to 1896.

An ardent believer in British imperialism, Rhodes and his Bri ...

's Cape to Cairo Railway project as the next undeveloped frontier.

Burnham distinguished himself in several battles in Rhodesia and South Africa and became Chief of Scouts. Despite his U.S. citizenship, his military title was British and his rank of major was formally given to him by King Edward VII

Edward VII (Albert Edward; 9 November 1841 – 6 May 1910) was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and Emperor of India, from 22 January 1901 until Death and state funeral of Edward VII, his death in 1910.

The second chil ...

. In special recognition of Burnham's heroism, the King invested him into the Companions of the Distinguished Service Order

The Distinguished Service Order (DSO) is a military decoration of the United Kingdom, as well as formerly of other parts of the Commonwealth, awarded for meritorious or distinguished service by officers of the armed forces during wartime, ty ...

, giving Burnham the highest military honors earned by any American in the Second Boer War

The Second Boer War ( af, Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, the Anglo–Boer War, or the South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer Republics (the So ...

. He had become friends with Baden-Powell

Lieutenant-General Robert Stephenson Smyth Baden-Powell, 1st Baron Baden-Powell, ( ; (Commonly pronounced by others as ) 22 February 1857 – 8 January 1941) was a British Army officer, writer, founder and first Chief Scout of the worl ...

during the Second Matabele War in Rhodesia, teaching him outdoor skills and inspiring what would later become known as Scouting. Burnham returned to the United States, where he became involved in national defense efforts, business, oil, conservation, and the Boy Scouts of America

The Boy Scouts of America (BSA, colloquially the Boy Scouts) is one of the largest scouting organizations and one of the largest youth organizations in the United States, with about 1.2 million youth participants. The BSA was founded in ...

(BSA).

During World War I, Burnham was selected as an officer and recruited volunteers for a U.S. Army division similar to the Rough Riders

The Rough Riders was a nickname given to the 1st United States Volunteer Cavalry, one of three such regiments raised in 1898 for the Spanish–American War and the only one to see combat. The United States Army was small, understaffed, and di ...

, which Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

intended to lead into France. For political reasons, the unit was disbanded without seeing action. After the war, Burnham and his business partner John Hays Hammond

John Hays Hammond (March 31, 1855 – June 8, 1936) was an American mining engineer, diplomat, and philanthropist. He amassed a sizable fortune before the age of 40. An early advocate of deep mining, Hammond was given complete charge of Ce ...

formed the Burnham Exploration Company; they became wealthy from oil discovered in California. Burnham joined several new wilderness conservation organizations, including the California State Parks Commission. In the 1930s, he worked with the BSA to save the big horn sheep from extinction. This effort led to the creation of the Kofa and Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuges in Arizona. He earned the BSA's highest honor, the Silver Buffalo Award

The Silver Buffalo Award is the national-level distinguished service award of the Boy Scouts of America. It is presented for noteworthy and extraordinary service to youth on a national basis, either as part of, or independent of the Scouting pro ...

, in 1936, and remained active in the organization at both the regional and national level until his death in 1947. To symbolise the friendship between Burnham and Baden-Powell, the mountain beside Mount Baden-Powell

Mount Baden-Powell () is a peak in the San Gabriel Mountains of California named for the founder of the World Scouting Movement, Robert Baden-Powell, 1st Baron Baden-Powell. It was officially recognized by the USGS at a dedication ceremony in 1 ...

in California was formally named Mount Burnham

Mount Burnham is one of the highest peaks in the San Gabriel Mountains. It is in the Sheep Mountain Wilderness. It is named for Frederick Russell Burnham the famous American military scout who taught Scoutcraft (then known as ''woodcraft'') to R ...

in 1951.

Early life

Burnham was born on May 11, 1861, on a

Burnham was born on May 11, 1861, on a Dakota Sioux

The Dakota (pronounced , Dakota language: ''Dakȟóta/Dakhóta'') are a Native American tribe and First Nations band government in North America. They compose two of the three main subcultures of the Sioux people, and are typically divided into ...

Indian reservation

An Indian reservation is an area of land held and governed by a federally recognized Native American tribal nation whose government is accountable to the United States Bureau of Indian Affairs and not to the state government in which it ...

in Minnesota

Minnesota () is a state in the upper midwestern region of the United States. It is the 12th largest U.S. state in area and the 22nd most populous, with over 5.75 million residents. Minnesota is home to western prairies, now given over t ...

, to a missionary

A missionary is a member of a Religious denomination, religious group which is sent into an area in order to promote its faith or provide services to people, such as education, literacy, social justice, health care, and economic development.Tho ...

family living near the small pioneer town of Tivoli (now gone), about 20 miles (32 km) from Mankato

Mankato ( ) is a city in Blue Earth, Nicollet, and Le Sueur counties in the state of Minnesota. The population was 44,488 according to the 2020 census, making it the 21st-largest city in Minnesota, and the 5th-largest outside of the Minnea ...

. His father, the Reverend Edwin Otway Burnham

Rev Edwin Otway Burnham (September 24, 1824 – August 1, 1873) was a Congregational minister and missionary.

He was born in Ghent, Kentucky, his father died when he was 5 and his mother died the following year. He and his younger sister, Carol ...

, was a Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their n ...

minister educated and ordained in New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

; he was born in Ghent, Kentucky

Ghent is a home rule-class city along the south bank of the Ohio River in Carroll County, Kentucky, in the United States. The population was 323 at the 2010 census.

Geography

Ghent is located in northeastern Carroll County at (38.736116, -85.0 ...

. His mother Rebecca Russell Burnham had spent most of her childhood in Iowa

Iowa () is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States, bordered by the Mississippi River to the east and the Missouri River and Big Sioux River to the west. It is bordered by six states: Wiscon ...

, having emigrated with her family from Westminster

Westminster is an area of Central London, part of the wider City of Westminster.

The area, which extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street, has many visitor attractions and historic landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, B ...

, England at the age of three. In the Dakota War of 1862, Chief Little Crow and his Sioux warriors attacked the nearby town New Ulm, Minnesota

New Ulm is a city in Brown County, Minnesota, United States. The population was 14,120 at the 2020 census. It is the county seat of Brown County. It is located on the triangle of land formed by the confluence of the Minnesota River and the ...

; Burnham's father was in Mankato buying ammunition at the time, so when Burnham's mother saw Sioux approaching her cabin dressed in war paint, she knew she had to leave and could never escape carrying her baby. She hid Frederick in a basket of green corn husks in a corn field and fled for her life. Once the Sioux attack had been repulsed, she returned to find their house burned down, but the baby Frederick was safe, fast asleep in the basket with the corn husks.

The young Burnham attended schools in Iowa. There he met Blanche Blick, whom he later married. The Burnham family moved from Minnesota to Los Angeles, California

Los Angeles ( ; es, Los Ángeles, link=no , ), often referred to by its initials L.A., is the List of municipalities in California, largest city in the U.S. state, state of California and the List of United States cities by population, sec ...

in 1870, in search of easier living conditions soon after Edwin was seriously injured in an accident while rebuilding the family homestead. Two years later, Edwin died, leaving the family destitute. Burnham's mother and three-year-old younger brother Howard returned to Iowa to live with her parents; the 12-year-old Burnham remained in California alone to repay his family's debts and ultimately make his own way.

For the next few years, Burnham worked as a mounted messenger for the Western Union Telegraph Company in California and Arizona Territory

The Territory of Arizona (also known as Arizona Territory) was a territory of the United States that existed from February 24, 1863, until February 14, 1912, when the remaining extent of the territory was admitted to the Union as the state o ...

. On one occasion his horse was stolen from him by Tiburcio Vásquez

Tiburcio Vásquez (April 11, 1835 – March 19, 1875) was a Californio ''bandido'' who was active in California from 1854 to 1874. The Vasquez Rocks, north of Los Angeles, were one of his many hideouts and are named after him.

Early life

T ...

, a famous Californio

Californio (plural Californios) is a term used to designate a Hispanic Californian, especially those descended from Spanish and Mexican settlers of the 17th through 19th centuries. California's Spanish-speaking community has resided there sin ...

bandit. At 14, he began his life as a scout and Indian tracker in the Apache Wars

The Apache Wars were a series of armed conflicts between the United States Army and various Apache tribal confederations fought in the southwest between 1849 and 1886, though minor hostilities continued until as late as 1924. After the Mexi ...

, during which he took part in the United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, ...

expedition to find and capture or kill the Apache

The Apache () are a group of culturally related Native American tribes in the Southwestern United States, which include the Chiricahua, Jicarilla, Lipan, Mescalero, Mimbreño, Ndendahe (Bedonkohe or Mogollon and Nednhi or Carrizaleño a ...

chief Geronimo

Geronimo ( apm, Goyaałé, , ; June 16, 1829 – February 17, 1909) was a prominent leader and medicine man from the Bedonkohe band of the Ndendahe Apache people. From 1850 to 1886, Geronimo joined with members of three other Central Apache b ...

. In Prescott, Arizona

Prescott ( ) is a city in Yavapai County, Arizona, United States. According to the 2020 Census, the city's population was 45,827. The city is the county seat of Yavapai County.

In 1864, Prescott was designated as the capital of the Arizona ...

, he met an old scout named Lee who served under General George Crook

George R. Crook (September 8, 1828 – March 21, 1890) was a career United States Army officer, most noted for his distinguished service during the American Civil War and the Indian Wars. During the 1880s, the Apache nicknamed Crook ''Nanta ...

. Lee taught Burnham how to track Apache by detecting the odor of burning mescal, a species of aloe they often cooked and ate. With careful study of the local air currents and canyons, trackers could follow the odor to Apache hiding places from as far away as 6 miles (9.7 km). During the Apache uprisings, the young Burnham also learned much from Al Sieber, the Chief of Scouts, and his assistant Archie McIntosh

Archie is a masculine given name, a diminutive of Archibald. It may refer to:

People Given name or nickname

*Archie Alexander (1888–1958), African-American mathematician, engineer and governor of the US Virgin Islands

* Archie Blake (mathemati ...

, who had been Chief of Scouts in Crook's last two campaigns. Burnham learned much about scouting from these Indian trackers, who were advanced in age and fading from the frontier, including the vital lesson that "it is imperative that a scout should know the history, tradition, religion, social customs, and superstitions of whatever country or people he is called on to work in or among." But the scout who was to have perhaps the greatest influence on Burnham during his formative years was a man named Holmes.

Holmes had served under

Holmes had served under Kit Carson

Christopher Houston Carson (December 24, 1809 – May 23, 1868) was an American frontiersman. He was a fur trapper, wilderness guide, Indian agent, and U.S. Army officer. He became a frontier legend in his own lifetime by biographies and ...

and John C. Fremont

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Second E ...

, but he was old and physically impaired when he met Burnham. He had lost all of his family in the Indian wars and before he died he wanted to impart his knowledge of the frontier to the young Burnham. The two men traveled throughout the American Southwest

The Southwestern United States, also known as the American Southwest or simply the Southwest, is a geographic and cultural region of the United States that generally includes Arizona, New Mexico, and adjacent portions of California, Colorado ...

and northern Mexico, and Holmes taught him many scouting skills, such as how to track a trail, how to double and cover one's own trail, how to properly ascend and descend precipices, and how to tell the time at night. Burnham also learned survival skills from Holmes, such as where to find water in the desert, how to protect himself from snakes, and what to do in case of forest fires or floods. A stickler for details, Holmes impressed on him that even in the simplest things, such as braiding a rope, tying a knot, or putting on or taking off a saddle, there is a right way and a wrong way. The two men earned a living by hunting and prospecting. Burnham also worked as a cowboy, a guard for the mines, a guide, and a scout during these years.

In Globe, Arizona

Globe ( apw, Bésh Baa Gowąh "Place of Metal") is a city in Gila County, Arizona, United States. As of the 2020 census, the population of the city was 7,249. The city is the county seat of Gila County. Globe was founded c. 1875 as a mining ca ...

, Burnham unwittingly joined the losing side of the Pleasant Valley War

The Pleasant Valley War, sometimes called the Tonto Basin Feud, or Tonto Basin War, or Tewksbury-Graham Feud, was a range war fought in Pleasant Valley, Arizona in the years 1882–1892. The conflict involved two feuding families, the Grahams an ...

before mass killing started, and only narrowly escaped death. He had no stake in the feud, but he was drawn into the conflict by his association with the Gordon family.

Once the killing started, he felt he had to join a faction as a hired gun, although it put him on the wrong side of the law. In between raids and forays, he practiced incessantly with his pistol; he learned to shoot using either hand and from the back of a galloping horse. Even after his faction admitted defeat (the feud would begin again years later), Burnham still had many enemies.

During this time he met "a fine, hard riding young Kansan, who I had met on an Indian raid and whose nerve I greatly admired." The young Kansan, who had been swindled by an unscrupulous superintendent of mines, had a plan to rustle cattle and horses from the superintendent and sell them to Curly Bill (William Brocius

William Brocius (c. 1845 – March 24, 1882), better known as Curly Bill Brocius, was an American gunman, rustler and an outlaw Cowboy in the Cochise County area of the Arizona Territory during the late 1870s and early 1880s. His name is like ...

), an outlaw with whom he had indirectly been in contact. Both men were broke at the time, and the job sounded easy. But Burnham had always rejected the life of a thief and even as a wanted man, he did not view himself as a criminal. Burnham began to see that even though he joined the feud to help his friends, he had been in the wrong, that "avenging only led to more vengeance and to even greater injustice than that suffered through the often unjustly administered laws of the land."

Burnham decided to reject the offer of the young Kansan (who followed through with the plan and was later killed), and that he needed to leave the Tonto Basin

The Tonto Basin, also known as Pleasant Valley, covers the main drainage basin of Tonto Creek and its tributaries in central Arizona, at the southwest of the Mogollon Rim, the higher elevation '' transition zone'' across central and eastern Ariz ...

. Judge Aaron Hackney

According to Abrahamic religions, Aaron ''′aharon'', ar, هارون, Hārūn, Greek (Septuagint): Ἀαρών; often called Aaron the priest ()., group="note" ( or ; ''’Ahărōn'') was a prophet, a high priest, and the elder brother of ...

, editor of the local ''Arizona Silver Belt

The ''Arizona Silver Belt'' is a newspaper in Globe, Arizona. It has been published since May 2, 1878. It is owned by News Media Corporation

News Media Corporation (NMC) is an America family-owned newspaper corporation that publishes 65 differ ...

'' newspaper and a friend, helped him escape to Tombstone, Arizona with the assistance of Neil McLeod. He was a well-known prizefighter in Tombstone and one of the most successful smugglers along the Arizona–Mexico frontier. The Gunfight at the O.K. Corral had occurred only a few months earlier, but as Tombstone was a boomtown

A boomtown is a community that undergoes sudden and rapid population and economic growth, or that is started from scratch. The growth is normally attributed to the nearby discovery of a precious resource such as gold, silver, or oil, althou ...

attracting new silver miners from all parts, it was an ideal location to hide out. Burnham assumed several aliases and occasionally he delivered messages for McLeod and his smuggler partners in Sonora, Mexico. From McLeod, he learned many valuable tricks for avoiding detection, passing coded messages, and throwing off pursuers.

Burnham eventually went back to California to attend high school, but he never graduated. He returned to Arizona and was appointed Deputy Sheriff of Pinal County

Pinal County is in the central part of the U.S. state of Arizona. According to the 2020 census, the population of the county was 425,264, making it Arizona's third-most populous county. The county seat is Florence. The county was founded in 187 ...

, but he soon went back to herding cattle and prospecting. After he went to Prescott, Iowa

Prescott is a city in Prescott Township, Adams County, Iowa, United States. The population was 191 at the time of the 2020 census.

Geography

Prescott is located at (41.022517, -94.612612).

According to the United States Census Bureau, the cit ...

to visit his childhood sweetheart Blanche, the two were married on February 6, 1884. He was 23 years old. He and Blanche settled down soon after in Pasadena, California

Pasadena ( ) is a city in Los Angeles County, California, northeast of downtown Los Angeles. It is the most populous city and the primary cultural center of the San Gabriel Valley. Old Pasadena is the city's original commercial district.

...

, to tend to an orange grove but soon Burnham returned to prospecting and scouting. Active as a Freemason

Freemasonry or Masonry refers to fraternal organisations that trace their origins to the local guilds of stonemasons that, from the end of the 13th century, regulated the qualifications of stonemasons and their interaction with authorities ...

, he rose to become a Thirty-Second Degree Mason of the Scottish Rite

The Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite of Freemasonry (the Northern Masonic Jurisdiction in the United States often omits the ''and'', while the English Constitution in the United Kingdom omits the ''Scottish''), commonly known as simply the S ...

.

During the 1880s, sections of the American press popularized the notion that the West had been won and there was nothing left to conquer in the United States. The time when great scouts like Kit Carson

Christopher Houston Carson (December 24, 1809 – May 23, 1868) was an American frontiersman. He was a fur trapper, wilderness guide, Indian agent, and U.S. Army officer. He became a frontier legend in his own lifetime by biographies and ...

, Daniel Boone

Daniel Boone (September 26, 1820) was an American pioneer and frontiersman whose exploits made him one of the first folk heroes of the United States. He became famous for his exploration and settlement of Kentucky, which was then beyond the we ...

, and Davy Crockett

David Crockett (August 17, 1786 – March 6, 1836) was an American folk hero, frontiersman, soldier, and politician. He is often referred to in popular culture as the "King of the Wild Frontier". He represented Tennessee in the U.S. House of ...

could explore and master the wild and uncharted Western territories was coming to a close. Contemporary scouts such as Buffalo Bill

William Frederick Cody (February 26, 1846January 10, 1917), known as "Buffalo Bill", was an American soldier, bison hunter, and showman. He was born in Le Claire, Iowa Territory (now the U.S. state of Iowa), but he lived for several years ...

, Wild Bill Hickok

James Butler Hickok (May 27, 1837August 2, 1876), better known as "Wild Bill" Hickok, was a folk hero of the American Old West known for his life on the frontier as a soldier, scout, lawman, gambler, showman, and actor, and for his involvement ...

, and Texas Jack Omohundro

John Baker Omohundro (July 27, 1846 – June 28, 1880), also known as "Texas Jack", was an American frontier scout, actor, and cowboy. Born in rural Virginia, he served the Confederate States of America during the American Civil War. He late ...

, were leaving the old West to become entertainers, and they battled great Native American chiefs like Sitting Bull

Sitting Bull ( lkt, Tȟatȟáŋka Íyotake ; December 15, 1890) was a Hunkpapa Lakota leader who led his people during years of resistance against United States government policies. He was killed by Indian agency police on the Standing Rock ...

, Chief Joseph

''Hin-mah-too-yah-lat-kekt'' (or ''Hinmatóowyalahtq̓it'' in Americanist orthography), popularly known as Chief Joseph, Young Joseph, or Joseph the Younger (March 3, 1840 – September 21, 1904), was a leader of the Wal-lam-wat-kain (Wallowa ...

, and Geronimo only in Wild West shows. In 1890 the United States Census Bureau

The United States Census Bureau (USCB), officially the Bureau of the Census, is a principal agency of the U.S. Federal Statistical System, responsible for producing data about the American people and economy. The Census Bureau is part of th ...

formally closed the American frontier

The American frontier, also known as the Old West or the Wild West, encompasses the geography, history, folklore, and culture associated with the forward wave of American expansion in mainland North America that began with European colonial ...

, ending the system under which land in the Western territories had been sold cheaply to pioneers. As a "soldier of fortune", as Richard Harding Davis

Richard Harding Davis (April 18, 1864 – April 11, 1916) was an American journalist and writer of fiction and drama, known foremost as the first American war correspondent to cover the Spanish–American War, the Second Boer War, and the First ...

later called him, Burnham began to look elsewhere for the next undeveloped frontier, feeling that the American West was becoming tame and unchallenging. When he heard of the work of Cecil Rhodes

Cecil John Rhodes (5 July 1853 – 26 March 1902) was a British mining magnate and politician in southern Africa who served as Prime Minister of the Cape Colony from 1890 to 1896.

An ardent believer in British imperialism, Rhodes and his Bri ...

and his pioneers in southern Africa, who were working to build a railway across Africa from Cape to Cairo, Burnham sold what little he owned. In 1893 with his wife and young son, he set sail for Durban

Durban ( ) ( zu, eThekwini, from meaning 'the port' also called zu, eZibubulungwini for the mountain range that terminates in the area), nicknamed ''Durbs'',Ishani ChettyCity nicknames in SA and across the worldArticle on ''news24.com'' from ...

in South Africa, intending to join Rhodes's pioneers in Matabeleland

Matabeleland is a region located in southwestern Zimbabwe that is divided into three provinces: Matabeleland North, Bulawayo, and Matabeleland South. These provinces are in the west and south-west of Zimbabwe, between the Limpopo and Zambe ...

and Mashonaland

Mashonaland is a region in northern Zimbabwe.

Currently, Mashonaland is divided into four provinces,

* Mashonaland West

* Mashonaland Central

* Mashonaland East

* Harare

The Zimbabwean capital of Harare, a province unto itself, lies entirely ...

.

Military career

First Matabele War

Burnham, along with his wife and son, was trekking the 1,000 miles (1,609 km) north from Durban to Matabeleland with an American

Burnham, along with his wife and son, was trekking the 1,000 miles (1,609 km) north from Durban to Matabeleland with an American buckboard

A buckboard is a four-wheeled wagon of simple construction meant to be drawn by a horse or other large animal. A distinctly American utility vehicle, the buckboard has no springs between the body and the axles. The suspension is provided by the f ...

and six donkeys when war broke out between Rhodes's British South Africa Company

The British South Africa Company (BSAC or BSACo) was chartered in 1889 following the amalgamation of Cecil Rhodes' Central Search Association and the London-based Exploring Company Ltd, which had originally competed to capitalize on the expect ...

and the Matabele (or Ndebele) King Lobengula

Lobengula Khumalo (c. 1845 – presumed January 1894) was the second and last official king of the Northern Ndebele people (historically called Matabele in English). Both names in the Ndebele language mean "the men of the long shields", a refer ...

in late 1893. He signed up to scout for the company immediately on reaching Matabeleland, and joined the fighting. Leander Starr Jameson

Sir Leander Starr Jameson, 1st Baronet, (9 February 1853 – 26 November 1917), was a British colonial politician, who was best known for his involvement in the ill-fated Jameson Raid.

Early life and family

He was born on 9 February 1853, o ...

, the company's Chief Magistrate in Mashonaland, hoped to defeat the Matabele quickly by capturing Lobengula at his royal town of Bulawayo

Bulawayo (, ; Ndebele: ''Bulawayo'') is the second largest city in Zimbabwe, and the largest city in the country's Matabeleland region. The city's population is disputed; the 2022 census listed it at 665,940, while the Bulawayo City Council ...

, and so sent Burnham and a small group of scouts ahead to report on the situation there. While on the outskirts of town they watched as the Matabele burned down and destroyed everything in sight. By the time the company troops had arrived in force, Lobengula and his warriors had fled and there was little left of old Bulawayo. The company then moved into the remains of Bulawayo, established a base, and sent out patrols to find Lobengula. The most famous of these patrols was the Shangani Patrol

The Shangani Patrol (or Wilson's Patrol) was a 34-soldier unit of the British South Africa Company that in 1893 was ambushed and annihilated by more than 3,000 Matabele warriors in pre-Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), during the First Matab ...

, led by Major Allan Wilson and the man he chose as his Chief of Scouts, Fred Burnham.

Shangani Patrol

Jameson sent a column of soldiers under Major Patrick Forbes to locate and capture Lobengula. The column camped on the south bank of the

Jameson sent a column of soldiers under Major Patrick Forbes to locate and capture Lobengula. The column camped on the south bank of the Shangani River

The Shangani is a river in Zimbabwe that starts near Gweru, Gweru River being one of its main tributaries' and goes through Midlands and Matabeleland North provinces. It empties into the Gwayi River.

The Shangani River was the site of the 4 D ...

about north-east of the village of Lupane on the evening of December 3, 1893. The next day, late in the afternoon, a dozen men under the command of Major Wilson were sent across the river to patrol the area. The Wilson Patrol came across a group of Matabele women and children who claimed to know Lobengula's whereabouts. Burnham, who served as the lead scout of the Wilson Patrol, sensed a trap and advised Wilson to withdraw, but Wilson ordered his patrol to advance.

Soon afterwards, the patrol found the king and Wilson sent a message back to the laager

A wagon fort, wagon fortress, or corral, often referred to as circling the wagons, is a temporary fortification made of wagons arranged into a rectangle, circle, or other shape and possibly joined with each other to produce an improvised milita ...

requesting reinforcements. Forbes, however, was unwilling to set off across the river in the dark, so he sent only 20 more men, under the command of Henry Borrow, to reinforce Wilson's patrol. Forbes intended to send the main body of troops and artillery across the river the following morning; however, the main column was ambushed by Matabele warriors and delayed. Wilson's patrol too came under attack, but the Shangani River had swollen and there was now no possibility of retreat. In desperation, Wilson sent Burnham and two other men, Pearl "Pete" Ingram (a Montana

Montana () is a state in the Mountain West division of the Western United States. It is bordered by Idaho to the west, North Dakota and South Dakota to the east, Wyoming to the south, and the Canadian provinces of Alberta, British Columb ...

cowboy) and William Gooding (an Australian), to cross the Shangani River, find Forbes, and bring reinforcements. In spite of a shower of bullets and spears, the three made it to Forbes, but the battle raging there was just as intense as the one they had left, and there was no hope of anyone reaching Wilson in time. As Burnham loaded his rifle to beat back the Matabele warriors, he quietly said to Forbes, "I think I may say that we are the sole survivors of that party." Wilson, Borrow, and their men were indeed surrounded by hundreds of Matabele warriors; escape was impossible, and all were killed.

Colonial-era histories called this the Shangani Patrol, and hailed Wilson and Borrow as national heroes. Their last stand together became a kind of national myth

A national myth is an inspiring narrative or anecdote about a nation's past. Such myths often serve as important national symbols and affirm a set of national values. A national myth may sometimes take the form of a national epic or be incorpor ...

, as Lewis Gann writes, "a glorious memory, hodesia'sown equivalent of the bloody Alamo massacre and Custer's Last Stand

The Battle of the Little Bighorn, known to the Lakota and other Plains Indians as the Battle of the Greasy Grass, and also commonly referred to as Custer's Last Stand, was an armed engagement between combined forces of the Lakota Sioux, Nor ...

in the American West

The Western United States (also called the American West, the Far West, and the West) is the region comprising the westernmost states of the United States. As American settlement in the U.S. expanded westward, the meaning of the term ''the Wes ...

". The version of events recorded by history is based on the accounts of Burnham, Ingram and Gooding, the Matabele present at the battle (particularly ''inDuna'' Mjaan), and the men of Forbes' column. While all of the direct evidence

Direct evidence supports the truth of an assertion (in criminal law, an assertion of guilt or of innocence) directly, i.e., without an intervening inference. A witness relates what they directly experienced, usually by sight or hearing, but also p ...

given by eyewitnesses supports the findings of the Court of Inquiry, some historians and writers debate whether or not Burnham, Ingram and Gooding really were sent back by Wilson to fetch help, and suggest that they might have simply deserted when the battle got rough. The earliest recording of this claim of desertion is long after the event in a letter written in 1935 by John Coghlan to a friend, John Carruthers, that "a very reliable man informed me that Wools-Sampson told him" that Gooding had confessed on his deathbed that he and the two Americans had not actually been despatched by Wilson, and had simply left on their own accord. This double hearsay confession, coming from an anonymous source, is not mentioned in Gooding's 1899 obituary, which instead recounts the events as generally recorded. Several well-known writers have used the Coghlan letter, as shaky as it is, as clearance to create hypothetical evidence in an attempt to challenge and revise the historical record.

All of the officers and troopers of Forbes' column had high praise for Burnham's actions, and none reported any doubts about his conduct even decades later. One member of the column, Trooper M E Weale, told the '' Rhodesia Herald'' in 1944 that once Commandant Piet Raaff took over command from the disgraced Major Forbes it was greatly due to Burnham's good scouting that the column managed to get away: "I have always felt that the honours were equally divided between these two men, to whom we owed our lives on that occasion." For his service in the war, Burnham was presented the British South Africa Company Medal

The British South Africa Company Medal (1890–97). In 1896, Queen Victoria sanctioned the issue by the British South Africa Company of a medal to troops who had been engaged in the First Matabele War. In 1897, the award was extended to those eng ...

, a gold watch, and a share of a 300-acre (120 ha) tract of land in Matabeleland. It was here that Burnham uncovered many artifacts in the huge granite ruins of the ancient civilization of Great Zimbabwe

Great Zimbabwe is a medieval city in the south-eastern hills of Zimbabwe near Lake Mutirikwi and the town of Masvingo. It is thought to have been the capital of a great kingdom during the country's Late Iron Age about which little is known. C ...

. Matabeleland became part of the Company domain, which was formally named Rhodesia

Rhodesia (, ), officially from 1970 the Republic of Rhodesia, was an unrecognised state in Southern Africa from 1965 to 1979, equivalent in territory to modern Zimbabwe. Rhodesia was the ''de facto'' successor state to the British colony of So ...

, after Rhodes, in 1895. Matabeleland and Mashonaland became collectively called Southern Rhodesia

Southern Rhodesia was a landlocked self-governing colony, self-governing British Crown colony in southern Africa, established in 1923 and consisting of British South Africa Company (BSAC) territories lying south of the Zambezi River. The reg ...

.

Northern Rhodesia exploration

In 1895, Burnham oversaw and led the Northern Territories British South Africa Exploration Company expedition that first established for the British South Africa Company that major copper deposits existed north of theZambezi

The Zambezi River (also spelled Zambeze and Zambesi) is the fourth-longest river in Africa, the longest east-flowing river in Africa and the largest flowing into the Indian Ocean from Africa. Its drainage basin covers , slightly less than ha ...

in North-Eastern Rhodesia

North-Eastern Rhodesia was a British protectorate in south central Africa formed in 1900.North-Eastern Rhodesia Order in Council, 1900 The protectorate was administered under charter by the British South Africa Company. It was one of what were ...

. Along the Kafue River

The Kafue River is the longest river lying wholly within Zambia at about long. Its water is used for irrigation and for hydroelectric power. It is the largest tributary of the Zambezi, and of Zambia's principal rivers, it is the most centra ...

, Burnham saw many similarities to copper deposits he had worked in the United States, and he encountered native peoples wearing copper bracelets. After this expedition he was elected a fellow of the Royal Geographical Society

The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers), often shortened to RGS, is a learned society and professional body for geography based in the United Kingdom. Founded in 1830 for the advancement of geographical scien ...

. Later, the British South Africa Company built the mining towns of the Copperbelt

The Copperbelt () is a natural region in Central Africa which sits on the border region between northern Zambia and the southern Democratic Republic of Congo. It is known for copper mining.

Traditionally, the term ''Copperbelt'' includes the ...

and a railroad to transport the ore through Portuguese Mozambique

Portuguese Mozambique ( pt, Moçambique) or Portuguese East Africa (''África Oriental Portuguesa'') were the common terms by which Mozambique was designated during the period in which it was a Portuguese colony. Portuguese Mozambique originally ...

.

Second Matabele War

In March 1896, the Matabele again rose up against the British South Africa Company administration in what became called the Second Matabele War or the First ''Chimurenga

''Chimurenga'' is a word in the Shona language. The Ndebele equivalent, though not as widely used since the majority of Zimbabweans are Shona speaking, is ''Umvukela'', meaning "revolutionary struggle" or uprising. In specific historical terms ...

'' (liberation war). Mlimo, the Matabele spiritual leader, is credited with fomenting much of the anger that led to this confrontation. The colonists' defenses in Matabeleland were undermanned due to the ill-fated Jameson Raid

The Jameson Raid (29 December 1895 – 2 January 1896) was a botched raid against the South African Republic (commonly known as the Transvaal) carried out by British colonial administrator Leander Starr Jameson, under the employment of Cecil ...

into the South African Republic

The South African Republic ( nl, Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek, abbreviated ZAR; af, Suid-Afrikaanse Republiek), also known as the Transvaal Republic, was an independent Boer Republic in Southern Africa which existed from 1852 to 1902, when i ...

(or Transvaal), and in the first few months of the war alone hundreds of white settlers were killed. With few troops to support them, the settlers quickly built a laager in the centre of Bulawayo on their own and mounted patrols under such figures as Burnham, Robert Baden-Powell

Lieutenant-General Robert Stephenson Smyth Baden-Powell, 1st Baron Baden-Powell, ( ; (Commonly pronounced by others as ) 22 February 1857 – 8 January 1941) was a British Army officer, writer, founder and first Chief Scout of the wor ...

, and Frederick Selous

Frederick Courteney Selous, DSO (; 31 December 1851 – 4 January 1917) was a British explorer, officer, professional hunter, and conservationist, famous for his exploits in Southeast Africa. His real-life adventures inspired Sir Henry Ride ...

. The Matabele retreated into their stronghold of the Matopos Hills

The Matobo National Park forms the core of the Matobo or Matopos Hills, an area of granite kopjes and wooded valleys commencing some south of Bulawayo, southern Zimbabwe. The hills were formed over 2 billion years ago with granite being force ...

near Bulawayo, a region that became the scene of the fiercest fighting between Matabele warriors and settler patrols. It was also during this war that two scouts of very different backgrounds, Burnham and Baden-Powell, would first meet and discuss ideas for training youth that would eventually become the plan for the program and the code of honor for the Boy Scouts

Boy Scouts may refer to:

* Boy Scout, a participant in the Boy Scout Movement.

* Scouting, also known as the Boy Scout Movement.

* An organisation in the Scouting Movement, although many of these organizations also have female members. There are t ...

.

Assassination of Mlimo

The turning point in the war came when Burnham and Bonar Armstrong, a company native commissioner, found their way through the Matopos Hills to a

The turning point in the war came when Burnham and Bonar Armstrong, a company native commissioner, found their way through the Matopos Hills to a sacred cave

A cave or cavern is a natural void in the ground, specifically a space large enough for a human to enter. Caves often form by the weathering of rock and often extend deep underground. The word ''cave'' can refer to smaller openings such as sea ...

not many miles from the Mangwe district

Mangwe District is a district of the Province Matabeleland South in Zimbabwe

Zimbabwe (), officially the Republic of Zimbabwe, is a landlocked country located in Southeast Africa, between the Zambezi and Limpopo Rivers, bordered by South ...

, to a sanctuary then known only to the Matabele where Mlimo had been hiding. Not far from the cave was a village (now gone) of about 100 huts filled with many warriors. The two men tethered their horses to a thicket and crawled on their bellies, screening their slow, cautious movements by means of branches held before them. Once inside the cave, they waited until Mlimo entered. Mlimo was said to be about 60 years old, with very dark skin, sharp-featured; American news reports of the time described him as having a cruel, crafty look. Burnham and Armstrong waited until Mlimo entered the cave and started his dance of immunity, at which point Burnham shot Mlimo just below the heart, killing him.

Burnham and Armstrong leapt over the dead Mlimo and ran down a trail toward their horses. The warriors in the village nearby picked up their arms and searched for the attackers; to distract them, Burnham set fire to some of their huts. The two men escaped and rode back to Bulawayo. Shortly after, Cecil Rhodes walked unarmed into the Matabele stronghold and made peace with the rebels, ending the Second Matabele War.

Klondike Gold Rush

With the Matabele wars over, Burnham decided it was time to leave Africa and move on to other adventures. The family returned to California. Soon after, Fred traveled to Alaska and theYukon

Yukon (; ; formerly called Yukon Territory and also referred to as the Yukon) is the smallest and westernmost of Canada's three territories. It also is the second-least populated province or territory in Canada, with a population of 43,964 as ...

to prospect in the Klondike Gold Rush, taking with him his eldest son Roderick, who was then 12 years old. On hearing of the Spanish–American War

, partof = the Philippine Revolution, the decolonization of the Americas, and the Cuban War of Independence

, image = Collage infobox for Spanish-American War.jpg

, image_size = 300px

, caption = (clock ...

, Burnham rushed home to volunteer his services, but the war had ended before he could get to the fighting. Burnham returned to the Klondike having played no part in the war. Colonel Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

regretted this as much as Burnham and paid him a great tribute in his book.

Second Boer War

The

The Second Boer War

The Second Boer War ( af, Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, the Anglo–Boer War, or the South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer Republics (the So ...

(October 1899 – May 1902) was fought between the British and two independent Boer

Boers ( ; af, Boere ()) are the descendants of the Dutch-speaking Free Burghers of the eastern Cape frontier in Southern Africa during the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. From 1652 to 1795, the Dutch East India Company controlled this are ...

republics, the South African Republic and the Orange Free State

The Orange Free State ( nl, Oranje Vrijstaat; af, Oranje-Vrystaat;) was an independent Boer sovereign republic under British suzerainty in Southern Africa during the second half of the 19th century, which ceased to exist after it was defeat ...

, partly the result of long-simmering strife between them. It was directly caused by each side's desire to control the lucrative Witwatersrand gold mines in the Transvaal. Field Marshal Frederick Roberts, one of the British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurkha ...

's most successful commanders of the 19th century, was appointed to take overall command of British forces, relieving General Redvers Buller

General Sir Redvers Henry Buller, (7 December 1839 – 2 June 1908) was a British Army officer and a recipient of the Victoria Cross, the highest award for gallantry in the face of the enemy that can be awarded to British and Commonwealth forc ...

, following a number of Boer successes in the early weeks of the war, including the Siege of Mafeking

The siege of Mafeking was a 217-day siege battle for the town of Mafeking (now called Mafikeng) in South Africa during the Second Boer War from October 1899 to May 1900. The siege received considerable attention as Lord Edward Cecil, the son of ...

, in which Baden-Powell, his small regiment of men, and the townspeople had been besieged by thousands of Boer troops since the conflict began. Roberts asked General Frederick Carrington

Major General Sir Frederick Carrington, (23 August 1844, Cheltenham – 22 March 1913, Cheltenham), was a British soldier and friend of Cecil Rhodes. He acquired fame by suppressing the 1896 Matabele rebellion.

Biography

Carrington was educ ...

, who had commanded the British forces in Matabeleland three years earlier, whom he should appoint as his Chief of Scouts in South Africa. Carrington had selected Burnham for this role and advised Roberts to do the same, describing Burnham as "the finest scout who ever scouted in Africa."

Roberts sent for Burnham soon after arriving in South Africa on the RMS ''Dunottar Castle''. The American scout was prospecting near Skagway, Alaska, when he received the following telegram in January 1900: "Lord Roberts appoints you on his personal staff as Chief of Scouts. If you accept, come at once the quickest way possible." Cape Town

Cape Town ( af, Kaapstad; , xh, iKapa) is one of South Africa's three capital cities, serving as the seat of the Parliament of South Africa. It is the legislative capital of the country, the oldest city in the country, and the second largest ...

is at the opposite end of the globe from the Klondike, so Burnham left immediately departing on the very same boat that had brought him the telegram. In an unusual step for a foreigner, Burnham received a command post from Roberts and the British Army rank of captain. Burnham reached the front just before the Battle of Paardeberg

The Battle of Paardeberg or Perdeberg ("Horse Mountain") was a major battle during the Second Anglo-Boer War. It was fought near ''Paardeberg Drift'' on the banks of the Modder River in the Orange Free State near Kimberley.