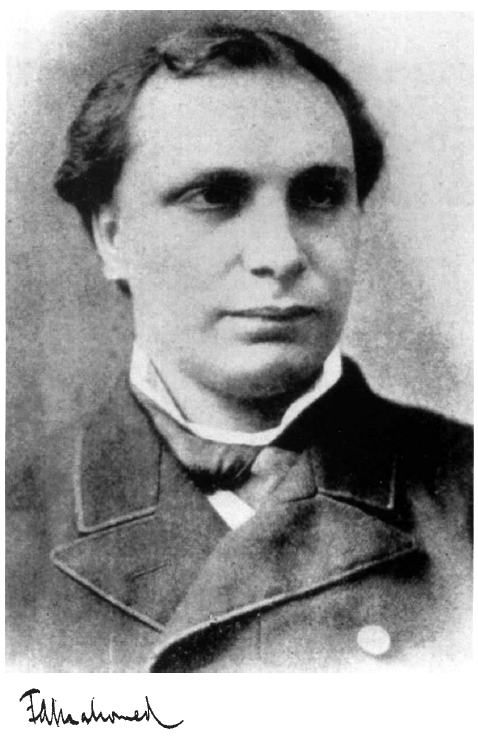

Frederick Akbar Mahomed on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Frederick Henry Horatio Akbar Mahomed (11 April 1849 – 22 November 1884) was an internationally known

Frederick Henry Horatio Akbar Mahomed (11 April 1849 – 22 November 1884) was an internationally known

In 1867, aged 18, Mahomed began to study medicine at the

In 1867, aged 18, Mahomed began to study medicine at the  Mahomed‘s earliest contribution, while still a

Mahomed‘s earliest contribution, while still a

Frederick Henry Horatio Akbar Mahomed (11 April 1849 – 22 November 1884) was an internationally known

Frederick Henry Horatio Akbar Mahomed (11 April 1849 – 22 November 1884) was an internationally known British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

physician

A physician (American English), medical practitioner (Commonwealth English), medical doctor, or simply doctor, is a health professional who practices medicine, which is concerned with promoting, maintaining or restoring health through th ...

from Brighton

Brighton () is a seaside resort and one of the two main areas of the City of Brighton and Hove in the county of East Sussex, England. It is located south of London.

Archaeological evidence of settlement in the area dates back to the Bronze A ...

, England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

.

Family and personal life

Frederick Henry Horatio Akbar Mahomed was born on 11 April 1849 inBrighton

Brighton () is a seaside resort and one of the two main areas of the City of Brighton and Hove in the county of East Sussex, England. It is located south of London.

Archaeological evidence of settlement in the area dates back to the Bronze A ...

. He was the eldest son of Frederick Mahomed (1818–1888) and his second wife, Sarah Hodgkinson (1816–1905). He was also the grandson of the pioneering India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

n traveller, author and entrepreneur Sake Dean Mahomed

Sake Dean Mahomed (1759–1851) was an Bengali traveller, surgeon, entrepreneur, and one of the most notable early non-European immigrants to the Western World. Due to non-standard transliteration, his name is often spelled in various ways. His ...

. Frederick Akbar Mahomed's father, Frederick Mahomed, ran a fencing

Fencing is a group of three related combat sports. The three disciplines in modern fencing are the foil, the épée, and the sabre (also ''saber''); winning points are made through the weapon's contact with an opponent. A fourth discipline, s ...

, gymnastics

Gymnastics is a type of sport that includes physical exercises requiring balance, strength, flexibility, agility, coordination, dedication and endurance. The movements involved in gymnastics contribute to the development of the arms, legs, shou ...

and callisthenics

Calisthenics (American English) or callisthenics (British English) ( /ˌkælɪsˈθɛnɪks/) is a form of strength training consisting of a variety of movements that exercise large muscle groups (gross motor movements), such as standing, graspi ...

academy in Hove

Hove is a seaside resort and one of the two main parts of the city of Brighton and Hove, along with Brighton in East Sussex, England. Originally a "small but ancient fishing village" surrounded by open farmland, it grew rapidly in the 19th cen ...

, which included boxing

Boxing (also known as "Western boxing" or "pugilism") is a combat sport in which two people, usually wearing protective gloves and other protective equipment such as hand wraps and mouthguards, throw punches at each other for a predetermined ...

instruction. Cameron and Hicks dispute the suggestion that he ran Turkish bath

A hammam ( ar, حمّام, translit=ḥammām, tr, hamam) or Turkish bath is a type of steam bath or a place of public bathing associated with the Islamic world. It is a prominent feature in the culture of the Muslim world and was inherited ...

s at Brighton attributing this to a confusion of Mahomed's father Frederick with his uncle, Arthur. Mahomed had three brothers (Arthur George Suleiman, James Deen Kerriman and Henry), and one sister (Adeline). He was educated privately in Brighton prior to attending medical school.

On June 14, 1873, at the parish church of St Nicholas', Brighton, Mahomed married Ellen (Nellie) Chalk. The couple had two children, a son, Archibald in 1874 and a daughter, Ellen in 1876. Only a month after the birth of Ellen in 1876, his wife, Ellen, died suddenly of sepsis

Sepsis, formerly known as septicemia (septicaemia in British English) or blood poisoning, is a life-threatening condition that arises when the body's response to infection causes injury to its own tissues and organs. This initial stage is follo ...

and Mahomed and his family moved in with his uncle, Horatio, also a widower, in Seymour Street near Portman Square

Portman Square is a garden square in Marylebone, central London, surrounded by elegant townhouses. It was specifically for private housing let on long leases having a ground rent by the Portman Estate, which owns the private communal gardens. ...

, London. In 1879 Mahomed married Ada Chalk, the younger sister of his first wife. As such a marriage was not legal under English law, the couple married in Switzerland. They lived at 12 St Thomas' Street

Park End Street is a street in central Oxford, England, to the west of the centre of the city, close to the railway station at its western end.

Location

To the east, New Road links Park End Street to central Oxford. To the west, Frideswide ...

, close to Guy's Hospital

Guy's Hospital is an NHS hospital in the borough of Southwark in central London. It is part of Guy's and St Thomas' NHS Foundation Trust and one of the institutions that comprise the King's Health Partners, an academic health science centre.

...

. The couple had two daughters, Dorothy in 1880, and Janet in 1881, and a son, Humphry in 1883. In 1884 the family moved from St Thomas' Street into a six-story Georgian house at 24 Manchester Square

Manchester Square is an 18th-century garden square in Marylebone, London. Centred north of Oxford Street it measures internally north-to-south, and across. It is a small Georgian predominantly 1770s-designed instance in central London; cons ...

. Sadly, later that year, Mahomed contracted typhoid fever

Typhoid fever, also known as typhoid, is a disease caused by '' Salmonella'' serotype Typhi bacteria. Symptoms vary from mild to severe, and usually begin six to 30 days after exposure. Often there is a gradual onset of a high fever over several ...

, presumably from a patient at the London Fever Hospital

The London Fever Hospital was a voluntary hospital financed from public donations in Liverpool Road in London. It was one of the first fever hospitals in the country.

History

Originally established with 15 beds in 1802 in Gray's Inn Road, it mov ...

, where he was working. He died on 22 November 1884 from an intestinal hemorrhage

Bleeding, hemorrhage, haemorrhage or blood loss, is blood escaping from the circulatory system from damaged blood vessels. Bleeding can occur internally, or externally either through a natural opening such as the mouth, nose, ear, urethra, vag ...

and a perforated intestine

The gastrointestinal tract (GI tract, digestive tract, alimentary canal) is the tract or passageway of the digestive system that leads from the mouth to the anus. The GI tract contains all the major organs of the digestive system, in humans ...

. He was buried on the western side of Highgate Cemetery

Highgate Cemetery is a place of burial in north London, England. There are approximately 170,000 people buried in around 53,000 graves across the West and East Cemeteries. Highgate Cemetery is notable both for some of the people buried there as ...

. On his death a subscription was set up to assist his family and several notable physicians, including Sir William Gull

Sir William Withey Gull, 1st Baronet (31 December 181629 January 1890) was an English physician. Of modest family origins, he established a lucrative private practice and served as Governor of Guy's Hospital, Fullerian Professor of Physiology ...

, Sir Samuel Wilks, Sir James Paget

Sir James Paget, 1st Baronet FRS HFRSE (11 January 1814 – 30 December 1899) (, rhymes with "gadget") was an English surgeon and pathologist who is best remembered for naming Paget's disease and who is considered, together with Rudolf Virch ...

and Elizabeth Garrett Anderson

Elizabeth Garrett Anderson (9 June 1836 – 17 December 1917) was an English physician and suffragist. She was the first woman to qualify in Britain as a physician and surgeon. She was the co-founder of the first hospital staffed by women, ...

, contributed. His oldest son, Archibald, later became a doctor, and in 1914 Archibald and the rest of the family changed their name to Deane (possibly acknowledging Frederick's grandfather's name, Deen) to lessen the impact of the xenophobia

Xenophobia () is the fear or dislike of anything which is perceived as being foreign or strange. It is an expression of perceived conflict between an in-group and out-group and may manifest in suspicion by the one of the other's activities, a ...

and racial prejudice

Racism is the belief that groups of humans possess different behavioral traits corresponding to inherited attributes and can be divided based on the superiority of one race over another. It may also mean prejudice, discrimination, or antagonism ...

associated with the outbreak of the World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

.

Education and career

In 1867, aged 18, Mahomed began to study medicine at the

In 1867, aged 18, Mahomed began to study medicine at the Sussex County Hospital

The Royal Sussex County Hospital is an acute teaching hospital in Brighton, England. Together with the Princess Royal Hospital, it is administered by the University Hospitals Sussex NHS Foundation Trust. The services provided at the hospital in ...

, Brighton. Two years later in October 1869, he entered Guy's Hospital, London as a medical student. He was an outstanding student and, in 1871, won the student Pupils' Physical Society prize for his work on the sphygmograph

The sphygmograph ( ) was a mechanical device used to measure blood pressure in the mid-19th century. It was developed in 1854 by German physiologist Karl von Vierordt (1818–1884). It is considered the first external, non-intrusive device used ...

, having been runner-up the previous year. Mahomed qualified as a Member of the Royal College of Surgeons

The Royal College of Surgeons is an ancient college (a form of corporation) established in England to regulate the activity of surgeons. Derivative organisations survive in many present and former members of the Commonwealth. These organisations a ...

in 1872. Following qualification, Mahomed worked at Highgate Infirmary (St Pancras' North Infirmary, Central London Sick Asylum) for a year. In 1873, he was appointed as resident medical officer at the London Fever Hospital

The London Fever Hospital was a voluntary hospital financed from public donations in Liverpool Road in London. It was one of the first fever hospitals in the country.

History

Originally established with 15 beds in 1802 in Gray's Inn Road, it mov ...

in Liverpool Street, Islington

Islington () is a district in the north of Greater London, England, and part of the London Borough of Islington. It is a mainly residential district of Inner London, extending from Islington's High Street to Highbury Fields, encompassing the ar ...

. In 1874 Mahomed became a member of the Royal College of Physicians

The Royal College of Physicians (RCP) is a British professional membership body dedicated to improving the practice of medicine, chiefly through the accreditation of physicians by examination. Founded by royal charter from King Henry VIII in 1 ...

and was appointed as Student Tutor and Pathologist at St Mary's Hospital, Paddington

Paddington is an area within the City of Westminster, in Central London. First a medieval parish then a metropolitan borough, it was integrated with Westminster and Greater London in 1965. Three important landmarks of the district are Paddi ...

. In 1875, Mahomed gained a doctorate (M.D.) from the University of Brussels. In 1877, he returned to Guy's Hospital as a Registrar (Senior Resident). He was elected as a Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians

The Royal College of Physicians (RCP) is a British professional membership body dedicated to improving the practice of medicine, chiefly through the accreditation of physicians by examination. Founded by royal charter from King Henry VIII in 1 ...

in 1880, and in 1881, he was awarded an M.B. from Cambridge University

, mottoeng = Literal: From here, light and sacred draughts.

Non literal: From this place, we gain enlightenment and precious knowledge.

, established =

, other_name = The Chancellor, Masters and Schola ...

for his thesis on "Chronic Bright's disease

Bright's disease is a historical classification of kidney diseases that are described in modern medicine as acute or chronic nephritis. It was characterized by swelling and the presence of albumin in the urine, and was frequently accompanied b ...

without albuminuria". In the same year, he was appointed Assistant Physician at Guy's Hospital and, in 1882, he was appointed as a Demonstrator in Morbid Anatomy at Guy's Hospital. Mahomed‘s earliest contribution, while still a

Mahomed‘s earliest contribution, while still a medical student

A medical school is a tertiary educational institution, or part of such an institution, that teaches medicine, and awards a professional degree for physicians. Such medical degrees include the Bachelor of Medicine, Bachelor of Surgery (MBBS, MB ...

, was to improve the sphygmograph

The sphygmograph ( ) was a mechanical device used to measure blood pressure in the mid-19th century. It was developed in 1854 by German physiologist Karl von Vierordt (1818–1884). It is considered the first external, non-intrusive device used ...

, a device for measuring blood pressure

Blood pressure (BP) is the pressure of circulating blood against the walls of blood vessels. Most of this pressure results from the heart pumping blood through the circulatory system. When used without qualification, the term "blood pressure" r ...

that had originally been devised by Karl von Vierordt

Karl von Vierordt (July 1, 1818 – November 22, 1884) was a German physiologist.

Vierordt was born in Lahr, Baden. He studied at the universities of Berlin, Göttingen, Vienna, and Heidelberg, and began a practice in Karlsruhe in 1842. In ...

and further developed by Étienne-Jules Marey

Étienne-Jules Marey (; 5 March 1830, Beaune, Côte-d'Or – 15 May 1904, Paris) was a French scientist, physiologist and chronophotographer.

His work was significant in the development of cardiology, physical instrumentation, aviation, cinema ...

. Mahomed’s major innovation was to make the sphygmograph quantitative, so that it was able to measure arterial blood pressure (in Troy ounces

Troy weight is a system of units of mass that originated in 15th-century England, and is primarily used in the precious metals industry. The troy weight units are the grain, the pennyweight (24 grains), the troy ounce (20 pennyweights), and the ...

). The description of the modified instrument was published in 1872. Following his graduation in the same year, Mahomed took up an appointment at the Central London Sick Asylum, where he worked with Sir William Broadbent, who became a strong supporter and friend. Several of Mahomed’s pulse tracings are contained in Broadbent’s classic book, ''The Pulse''. Mahomed used the new sphygmograph to measure arterial tension (blood pressure) in Bright's disease

Bright's disease is a historical classification of kidney diseases that are described in modern medicine as acute or chronic nephritis. It was characterized by swelling and the presence of albumin in the urine, and was frequently accompanied b ...

and a range of other conditions, including pregnancy

Pregnancy is the time during which one or more offspring develops ( gestates) inside a woman's uterus (womb). A multiple pregnancy involves more than one offspring, such as with twins.

Pregnancy usually occurs by sexual intercourse, but ca ...

, scarlet fever

Scarlet fever, also known as Scarlatina, is an infectious disease caused by ''Streptococcus pyogenes'' a Group A streptococcus (GAS). The infection is a type of Group A streptococcal infection (Group A strep). It most commonly affects childr ...

, gout

Gout ( ) is a form of inflammatory arthritis characterized by recurrent attacks of a red, tender, hot and swollen joint, caused by deposition of monosodium urate monohydrate crystals. Pain typically comes on rapidly, reaching maximal intensit ...

, alcohol

Alcohol most commonly refers to:

* Alcohol (chemistry), an organic compound in which a hydroxyl group is bound to a carbon atom

* Alcohol (drug), an intoxicant found in alcoholic drinks

Alcohol may also refer to:

Chemicals

* Ethanol, one of sev ...

and lead poisoning

Lead poisoning, also known as plumbism and saturnism, is a type of metal poisoning caused by lead in the body. The brain is the most sensitive. Symptoms may include abdominal pain, constipation, headaches, irritability, memory problems, inferti ...

. He found that in some individuals blood pressure was elevated before there was evidence of kidney disease

Kidney disease, or renal disease, technically referred to as nephropathy, is damage to or disease of a kidney. Nephritis is an inflammatory kidney disease and has several types according to the location of the inflammation. Inflammation can ...

, assessed by measurement of protein in the urine (proteinuria

Proteinuria is the presence of excess proteins in the urine. In healthy persons, urine contains very little protein; an excess is suggestive of illness. Excess protein in the urine often causes the urine to become foamy (although this symptom ma ...

). He also made the association between the elevated blood pressure and various post-mortem

An autopsy (post-mortem examination, obduction, necropsy, or autopsia cadaverum) is a surgical procedure that consists of a thorough examination of a corpse by dissection to determine the cause, mode, and manner of death or to evaluate any dis ...

changes, including enlargement of the heart

The heart is a muscular organ in most animals. This organ pumps blood through the blood vessels of the circulatory system. The pumped blood carries oxygen and nutrients to the body, while carrying metabolic waste such as carbon dioxide t ...

(cardiac hypertrophy

Ventricular hypertrophy (VH) is thickening of the walls of a ventricle (lower chamber) of the heart. Although left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) is more common, right ventricular hypertrophy (RVH), as well as concurrent hypertrophy of both ventri ...

), thickening and fibrosis

Fibrosis, also known as fibrotic scarring, is a pathological wound healing in which connective tissue replaces normal parenchymal tissue to the extent that it goes unchecked, leading to considerable tissue remodelling and the formation of perma ...

of the arterial wall

An artery (plural arteries) () is a blood vessel in humans and most animals that takes blood away from the heart to one or more parts of the body (tissues, lungs, brain etc.). Most arteries carry oxygenated blood; the two exceptions are the pul ...

, aneurysm

An aneurysm is an outward bulging, likened to a bubble or balloon, caused by a localized, abnormal, weak spot on a blood vessel wall. Aneurysms may be a result of a hereditary condition or an acquired disease. Aneurysms can also be a nidus (s ...

formation, and damage to the microcirculation

The microcirculation is the circulation of the blood in the smallest blood vessels, the microvessels of the microvasculature present within organ tissues. The microvessels include terminal arterioles, metarterioles, capillaries, and venules. ...

(arterio-capillary fibrosis). In effect, Mahomed was describing most of the key pathological effects of essential hypertension

Essential hypertension (also called primary hypertension, or idiopathic hypertension) is the form of hypertension that by definition has no identifiable secondary cause. It is the most common type affecting 85% of those with high blood pressure. T ...

for the first time. Initially he termed this condition "Bright's disease without albuminuria" but later he described it as “high pressure diathesis”. His description of the condition is worth citing:‘…the existence of this abnormally high pressure does not necessarily mean disease, but only a tendency towards disease. It is a functional condition, not necessarily a permanent one, though it is generally more or less so in these individuals. These persons appear to pass on through life pretty much as others do… As age advances the enemy gains accessions of strength; perhaps the mode of life assists him - good living and alcoholic beverages make secure his position, or head work, mental anxiety, hurried meals, constant excitement, inappropriate or badly cooked food, or any other of the common but undesirable circumstances of everyday life, tend to intensify the existing condition, or, if not previously present, perhaps produce it. Now under this greatly increased arterial pressure, hearts begin to hypertrophy and arteries to thicken; what has previously been a functional condition tends to become more of the nature of an organic one…’Mahomed also proposed that reducing blood pressure would prolong life, although the means of doing that in his era were in the main limited to lifestyle advice. In 1880 Mahomed made a first foray into

public health

Public health is "the science and art of preventing disease, prolonging life and promoting health through the organized efforts and informed choices of society, organizations, public and private, communities and individuals". Analyzing the det ...

. He wrote to the British Medical Journal

''The BMJ'' is a weekly peer-reviewed medical trade journal, published by the trade union the British Medical Association (BMA). ''The BMJ'' has editorial freedom from the BMA. It is one of the world's oldest general medical journals. Origi ...

to advocate undertaking the comprehensive systematic documentation of disease in Britain; he termed this idea, Collective Investigation. Mahomed’s proposals were warmly supported by Sir George Murray Humphry, the President of the British Medical Association

The British Medical Association (BMA) is a registered trade union for doctors in the United Kingdom. The association does not regulate or certify doctors, a responsibility which lies with the General Medical Council. The association's headquar ...

, and a Collective Investigation Committee was formed in 1881 with Mahomed as secretary. Around this time Mahomed became acquainted with the British polymath, Francis Galton

Sir Francis Galton, FRS FRAI (; 16 February 1822 – 17 January 1911), was an English Victorian era polymath: a statistician, sociologist, psychologist, anthropologist, tropical explorer, geographer, inventor, meteorologist, proto- ...

, who shared an interest in factors predisposing to disease. Mahomed and Galton collaborated to produce composite photographs of over 400 patients with phthisis (tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, in ...

), which they compared with composite photographs based on 200 individuals without evidence of phthisis to test whether, as was widely believed, appearance or looks indicated a predisposition to disease. They found no evidence of a characteristic facial appearance associated with tuberculosis beyond some evidence of emaciation.

In 1882 Mahomed advocated expanding Collective Investigation to include a general collection of detailed family life histories: 'for encouraging patients to keep carefully prepared records of their lives and of the chief incidents therein, both medical and otherwise. These records would prove of very great value, alike to the patient, to the doctor, and to medical science.'A life-history subcommittee of the Collective Investigation Committee, including both Mahomed and Galton was formed in 1882. Initially the Collective Investigation Committee was very successful with 54 local Collective Investigation Committees being formed to collect data. Their preliminary findings were published in 1883 as a 76-page single volume called 'The Collective Investigation Record' and included results based on more than 2000 patients. In 1884, a Life History Album was published to allow parents to record details of family circumstances and child development. It was advertized in

Nature

Nature, in the broadest sense, is the physics, physical world or universe. "Nature" can refer to the phenomenon, phenomena of the physical world, and also to life in general. The study of nature is a large, if not the only, part of science. ...

and Galton offered prizes of £500 to people who submitted the most complete family records - within 5 months he had received in excess of 150 records. Over the subsequent 5 years data based on over 300 family records were published, with the main findings summarised in Galton’s book, Natural Inheritance. However, Mahomed would not see these achievements as he died in November 1884 from typhoid fever.

Contribution

Michael F. O'Rourke summarizes the contributions of Frederick Akbar Mahomed as follows:See also

*Sake Dean Mahomed

Sake Dean Mahomed (1759–1851) was an Bengali traveller, surgeon, entrepreneur, and one of the most notable early non-European immigrants to the Western World. Due to non-standard transliteration, his name is often spelled in various ways. His ...

References

{{DEFAULTSORT:Mahomed, Frederick Akbar 1849 births 1884 deaths Burials at Highgate Cemetery 19th-century English medical doctors Anglo-Indian people English people of Indian descent English people of Irish descent Gout researchers