Francis Galton on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sir Francis Galton, FRS FRAI (; 16 February 1822 – 17 January 1911), was an English

Galton was a

Galton was a

Galton was a

Galton was a

Galton's formulation of regression and its link to the bivariate normal distribution can be traced to his attempts at developing a mathematical model for population stability. Although Galton's first attempt to study Darwinian questions, ''Hereditary Genius'', generated little enthusiasm at the time, the text led to his further studies in the 1870s concerning the inheritance of physical traits. This text contains some crude notions of the concept of regression, described in a qualitative matter. For example, he wrote of dogs: "If a man breeds from strong, well-shaped dogs, but of mixed pedigree, the puppies will be sometimes, but rarely, the equals of their parents. They will commonly be of a mongrel, nondescript type, because ancestral peculiarities are apt to crop out in the offspring."

This notion created a problem for Galton, as he could not reconcile the tendency of a population to maintain a normal distribution of traits from generation to generation with the notion of inheritance. It seemed that a large number of factors operated independently on offspring, leading to the normal distribution of a trait in each generation. However, this provided no explanation as to how a parent can have a significant impact on his offspring, which was the basis of inheritance.

Galton's solution to this problem was presented in his Presidential Address at the September 1885 meeting of the

Galton's formulation of regression and its link to the bivariate normal distribution can be traced to his attempts at developing a mathematical model for population stability. Although Galton's first attempt to study Darwinian questions, ''Hereditary Genius'', generated little enthusiasm at the time, the text led to his further studies in the 1870s concerning the inheritance of physical traits. This text contains some crude notions of the concept of regression, described in a qualitative matter. For example, he wrote of dogs: "If a man breeds from strong, well-shaped dogs, but of mixed pedigree, the puppies will be sometimes, but rarely, the equals of their parents. They will commonly be of a mongrel, nondescript type, because ancestral peculiarities are apt to crop out in the offspring."

This notion created a problem for Galton, as he could not reconcile the tendency of a population to maintain a normal distribution of traits from generation to generation with the notion of inheritance. It seemed that a large number of factors operated independently on offspring, leading to the normal distribution of a trait in each generation. However, this provided no explanation as to how a parent can have a significant impact on his offspring, which was the basis of inheritance.

Galton's solution to this problem was presented in his Presidential Address at the September 1885 meeting of the

Studying variation, Galton invented the Galton board, a

Studying variation, Galton invented the Galton board, a

In 1846, the French physicist Auguste Bravais (1811–1863) first developed what would become the correlation coefficient. After examining forearm and height measurements, Galton independently rediscovered the concept of

In 1846, the French physicist Auguste Bravais (1811–1863) first developed what would become the correlation coefficient. After examining forearm and height measurements, Galton independently rediscovered the concept of

In an effort to reach a wider audience, Galton worked on a novel entitled ''Kantsaywhere'' from May until December 1910. The novel described a utopia organized by a eugenic religion, designed to breed fitter and smarter humans. His unpublished notebooks show that this was an expansion of material he had been composing since at least 1901. He offered it to Methuen for publication, but they showed little enthusiasm. Galton wrote to his niece that it should be either "smothered or superseded". His niece appears to have burnt most of the novel, offended by the love scenes, but large fragments survived, and it was published online by University College, London.

Galton is buried in the family tomb in the churchyard of St Michael and All Angels, in the village of

In an effort to reach a wider audience, Galton worked on a novel entitled ''Kantsaywhere'' from May until December 1910. The novel described a utopia organized by a eugenic religion, designed to breed fitter and smarter humans. His unpublished notebooks show that this was an expansion of material he had been composing since at least 1901. He offered it to Methuen for publication, but they showed little enthusiasm. Galton wrote to his niece that it should be either "smothered or superseded". His niece appears to have burnt most of the novel, offended by the love scenes, but large fragments survived, and it was published online by University College, London.

Galton is buried in the family tomb in the churchyard of St Michael and All Angels, in the village of

It has been written of Galton that "On his own estimation he was a supremely intelligent man." Later in life, Galton proposed a connection between genius and insanity based on his own experience:

It has been written of Galton that "On his own estimation he was a supremely intelligent man." Later in life, Galton proposed a connection between genius and insanity based on his own experience:

Galton's Complete Works

at Galton.org (including all his published books, all his published scientific papers, and popular periodical and newspaper writing, as well as other previously unpublished work and biographical material). * * * * * * *

Biography and bibliography

in the Virtual Laboratory of the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science

History and Mathematics

Human Memory – University of Amsterdam

website with test based on the work of Galton * from Index Funds Advisor

IFA.comCatalogue of the Galton papers held at UCL Archives

Galton's novel ''Kantsaywhere''

* *, demonstrated by Alex Bellos * {{DEFAULTSORT:Galton, Francis 1822 births 1911 deaths 19th-century English people Alumni of King's College London Alumni of Trinity College, Cambridge Anthropometry Biopolitics Critics of Lamarckism Darwin–Wedgwood family English anthropologists English eugenicists English explorers English geographers English inventors English meteorologists English statisticians Evolutionary biologists British explorers of Africa Fellows of the Royal Geographical Society Fellows of the Royal Society Fellows of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland Presidents of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland Freemasons of the United Grand Lodge of England Independent scientists Intelligence researchers Knights Bachelor People educated at King Edward's School, Birmingham People from Birmingham, West Midlands Probability theorists Psychometricians Recipients of the Copley Medal Royal Medal winners

Victorian era

In the history of the United Kingdom and the British Empire, the Victorian era was the period of Queen Victoria's reign, from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. The era followed the Georgian period and preceded the Edwa ...

polymath

A polymath ( el, πολυμαθής, , "having learned much"; la, homo universalis, "universal human") is an individual whose knowledge spans a substantial number of subjects, known to draw on complex bodies of knowledge to solve specific pro ...

: a statistician

A statistician is a person who works with theoretical or applied statistics. The profession exists in both the private and public sectors.

It is common to combine statistical knowledge with expertise in other subjects, and statisticians may w ...

, sociologist, psychologist

A psychologist is a professional who practices psychology and studies mental states, perceptual

Perception () is the organization, identification, and interpretation of sensory information in order to represent and understand the pre ...

, anthropologist

An anthropologist is a person engaged in the practice of anthropology. Anthropology is the study of aspects of humans within past and present societies. Social anthropology, cultural anthropology and philosophical anthropology study the norms an ...

, tropical explorer

Exploration refers to the historical practice of discovering remote lands. It is studied by geographers and historians.

Two major eras of exploration occurred in human history: one of convergence, and one of divergence. The first, covering most ...

, geographer

A geographer is a physical scientist, social scientist or humanist whose area of study is geography, the study of Earth's natural environment and human society, including how society and nature interacts. The Greek prefix "geo" means "earth" a ...

, inventor

An invention is a unique or novel device, method, composition, idea or process. An invention may be an improvement upon a machine, product, or process for increasing efficiency or lowering cost. It may also be an entirely new concept. If an ...

, meteorologist

A meteorologist is a scientist who studies and works in the field of meteorology aiming to understand or predict Earth's atmospheric phenomena including the weather. Those who study meteorological phenomena are meteorologists in research, while t ...

, proto-geneticist

A geneticist is a biologist or physician who studies genetics, the science of genes, heredity, and variation of organisms. A geneticist can be employed as a scientist or a lecturer. Geneticists may perform general research on genetic processes ...

, psychometrician

Psychometrics is a field of study within psychology concerned with the theory and technique of measurement. Psychometrics generally refers to specialized fields within psychology and education devoted to testing, measurement, assessment, an ...

and a proponent of social Darwinism

Social Darwinism refers to various theories and societal practices that purport to apply biological concepts of natural selection and survival of the fittest to sociology, economics and politics, and which were largely defined by scholars in We ...

, eugenics

Eugenics ( ; ) is a fringe set of beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetic quality of a human population. Historically, eugenicists have attempted to alter human gene pools by excluding people and groups judged to be inferior o ...

, and scientific racism

Scientific racism, sometimes termed biological racism, is the pseudoscience, pseudoscientific belief that empirical evidence exists to support or justify racism (racial discrimination), racial inferiority, or racial superiority.. "Few tragedies ...

. He was knighted in 1909.

Galton produced over 340 papers and books. He also created the statistical concept of correlation

In statistics, correlation or dependence is any statistical relationship, whether causal or not, between two random variables or bivariate data. Although in the broadest sense, "correlation" may indicate any type of association, in statistic ...

and widely promoted regression toward the mean

In statistics, regression toward the mean (also called reversion to the mean, and reversion to mediocrity) is the fact that if one sample of a random variable is extreme, the next sampling of the same random variable is likely to be closer to it ...

. He was the first to apply statistical methods to the study of human differences and inheritance of intelligence

Research on the heritability of IQ inquires into the degree of variation in IQ within a population that is due to genetic variation between individuals in that population. There has been significant controversy in the academic community about the h ...

, and introduced the use of questionnaires and surveys for collecting data on human communities, which he needed for genealogical and biographical works and for his anthropometric studies. He was a pioneer of eugenics

Eugenics ( ; ) is a fringe set of beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetic quality of a human population. Historically, eugenicists have attempted to alter human gene pools by excluding people and groups judged to be inferior o ...

, coining the term itself in 1883, and also coined the phrase "nature versus nurture

Nature versus nurture is a long-standing debate in biology and society about the balance between two competing factors which determine fate: genetics (nature) and environment (nurture). The alliterative expression "nature and nurture" in English h ...

". His book ''Hereditary Genius

''Hereditary Genius: An Inquiry Into Its Laws and Consequences'' is a book by Francis Galton about the genetic inheritance of intelligence. It was first published in 1869 by Macmillan Publishers. The first American edition was published by D. A ...

'' (1869) was the first social scientific attempt to study genius

Genius is a characteristic of original and exceptional insight in the performance of some art or endeavor that surpasses expectations, sets new standards for future works, establishes better methods of operation, or remains outside the capabili ...

and greatness

Greatness is a concept of a state of superiority affecting a person or object in a particular place or area. Greatness can also be attributed to individuals who possess a natural ability to be better than all others. An example of an expressi ...

.

As an investigator of the human mind, he founded psychometrics

Psychometrics is a field of study within psychology concerned with the theory and technique of measurement. Psychometrics generally refers to specialized fields within psychology and education devoted to testing, measurement, assessment, and ...

(the science of measuring mental faculties) and differential psychology

Differential psychology studies the ways in which individuals differ in their behavior and the processes that underlie it. This is a discipline that develops classifications (taxonomies) of psychological individual differences. This is distingui ...

, as well as the lexical hypothesis

The lexical hypothesis (also known as the fundamental lexical hypothesis, lexical approach, or sedimentation hypothesis) is a thesis, current primarily in early personality psychology, and subsequently subsumed by many later efforts in that subfie ...

of personality. He devised a method for classifying fingerprint

A fingerprint is an impression left by the friction ridges of a human finger. The recovery of partial fingerprints from a crime scene is an important method of forensic science. Moisture and grease on a finger result in fingerprints on surfac ...

s that proved useful in forensic science

Forensic science, also known as criminalistics, is the application of science to criminal and civil laws, mainly—on the criminal side—during criminal investigation, as governed by the legal standards of admissible evidence and criminal ...

. He also conducted research on the power of prayer, concluding it had none due to its null effects on the longevity of those prayed for. His quest for the scientific principles of diverse phenomena extended even to the optimal method for making tea.

As the initiator of scientific meteorology

Meteorology is a branch of the atmospheric sciences (which include atmospheric chemistry and physics) with a major focus on weather forecasting. The study of meteorology dates back millennia, though significant progress in meteorology did no ...

, he devised the first weather map

A weather map, also known as synoptic weather chart, displays various meteorological features across a particular area at a particular point in time and has various symbols which all have specific meanings. Such maps have been in use since the mi ...

, proposed a theory of anticyclone

An anticyclone is a weather phenomenon defined as a large-scale circulation of winds around a central region of high atmospheric pressure, clockwise in the Northern Hemisphere and counterclockwise in the Southern Hemisphere as viewed from ...

s, and was the first to establish a complete record of short-term climatic phenomena on a European scale. He also invented the Galton Whistle for testing differential hearing ability. He was Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended ...

's half-cousin.

Early life

Galton was born at "The Larches", a large house in theSparkbrook

Sparkbrook is an inner-city area in south-east Birmingham, England. It is one of the four wards forming the Hall Green formal district within Birmingham City Council.

Etymology

The area receives its name from Spark Brook, a small stream that f ...

area of Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands in England. It is the second-largest city in the United Kingdom with a population of 1.145 million in the city proper, 2.92 million in the We ...

, England, built on the site of "Fair Hill", the former home of Joseph Priestley

Joseph Priestley (; 24 March 1733 – 6 February 1804) was an English chemist, natural philosopher, separatist theologian, grammarian, multi-subject educator, and liberal political theorist. He published over 150 works, and conducted ...

, which the botanist

Botany, also called , plant biology or phytology, is the science of plant life and a branch of biology. A botanist, plant scientist or phytologist is a scientist who specialises in this field. The term "botany" comes from the Ancient Greek wo ...

William Withering

William Withering FRS (17 March 1741 – 6 October 1799) was an English botanist, geologist, chemist, physician and first systematic investigator of the bioactivity of digitalis.

Withering was born in Wellington, Shropshire, the son of a surg ...

had renamed. He was Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended ...

's half-cousin, sharing the common grandparent Erasmus Darwin

Erasmus Robert Darwin (12 December 173118 April 1802) was an English physician. One of the key thinkers of the Midlands Enlightenment, he was also a natural philosopher, physiologist, slave-trade abolitionist, inventor, and poet.

His poems ...

. His father was Samuel Tertius Galton, son of Samuel Galton, Jr. He was also a cousin of Douglas Strutt Galton

Sir Douglas Strutt Galton (2 July 1822 – 18 March 1899) was a British engineer. He became a captain in the Royal Engineers and Secretary to the Railway Department, Board of Trade. In 1866 he was a member of the Royal Commission on Railways ...

. The Galtons were Quaker

Quakers are people who belong to a historically Protestant Christian set of denominations known formally as the Religious Society of Friends. Members of these movements ("theFriends") are generally united by a belief in each human's abili ...

gun-manufacturers and bankers, while the Darwins were involved in medicine and science.

Both the Galton and Darwin families included Fellow

A fellow is a concept whose exact meaning depends on context.

In learned or professional societies, it refers to a privileged member who is specially elected in recognition of their work and achievements.

Within the context of higher education ...

s of the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

and members who loved to invent in their spare time. Both Erasmus Darwin and Samuel Galton were founding members of the Lunar Society

The Lunar Society of Birmingham was a British dinner club and informal learned society of prominent figures in the Midlands Enlightenment, including industrialists, natural philosophers and intellectuals, who met regularly between 1765 and 1813 ...

of Birmingham, which included Matthew Boulton

Matthew Boulton (; 3 September 172817 August 1809) was an English manufacturer and business partner of Scottish engineer James Watt. In the final quarter of the 18th century, the partnership installed hundreds of Boulton & Watt steam engin ...

, James Watt

James Watt (; 30 January 1736 (19 January 1736 OS) – 25 August 1819) was a Scottish inventor, mechanical engineer, and chemist who improved on Thomas Newcomen's 1712 Newcomen steam engine with his Watt steam engine in 1776, which was ...

, Josiah Wedgwood

Josiah Wedgwood (12 July 1730 – 3 January 1795) was an English potter, entrepreneur and abolitionist. Founding the Wedgwood company in 1759, he developed improved pottery bodies by systematic experimentation, and was the leader in the indus ...

, Joseph Priestley

Joseph Priestley (; 24 March 1733 – 6 February 1804) was an English chemist, natural philosopher, separatist theologian, grammarian, multi-subject educator, and liberal political theorist. He published over 150 works, and conducted ...

and Richard Lovell Edgeworth

Richard Lovell Edgeworth (31 May 1744 – 13 June 1817) was an Anglo-Irish politician, writer and inventor.

Biography

Edgeworth was born in Pierrepont Street, Bath, England, son of Richard Edgeworth senior, and great-grandson of Sir Sal ...

. Both families were known for their literary talent. Erasmus Darwin composed lengthy technical treatises in verse. Galton's aunt Mary Anne Galton wrote on aesthetics and religion, and her autobiography detailed the environment of her childhood populated by Lunar Society members.

Galton was a

Galton was a child prodigy

A child prodigy is defined in psychology research literature as a person under the age of ten who produces meaningful output in some domain at the level of an adult expert. The term is also applied more broadly to young people who are extraor ...

– he was reading by the age of two; at age five he knew some Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

, Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

and long division, and by the age of six he had moved on to adult books, including Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

for pleasure, and poetry, which he quoted at length. Galton attended King Edward's School, Birmingham, but chafed at the narrow classical curriculum and left at 16. His parents pressed him to enter the medical profession, and he studied for two years at Birmingham General Hospital and King's College London

King's College London (informally King's or KCL) is a public research university located in London, England. King's was established by royal charter in 1829 under the patronage of King George IV and the Duke of Wellington. In 1836, King's ...

Medical School

A medical school is a tertiary educational institution, or part of such an institution, that teaches medicine, and awards a professional degree for physicians. Such medical degrees include the Bachelor of Medicine, Bachelor of Surgery (MBBS, ...

. He followed this up with mathematical studies at Trinity College Trinity College may refer to:

Australia

* Trinity Anglican College, an Anglican coeducational primary and secondary school in , New South Wales

* Trinity Catholic College, Auburn, a coeducational school in the inner-western suburbs of Sydney, New ...

, Cambridge, from 1840 to early 1844.

According to the records of the United Grand Lodge of England

The United Grand Lodge of England (UGLE) is the governing Masonic lodge for the majority of freemasons in England, Wales and the Commonwealth of Nations. Claiming descent from the Masonic grand lodge formed 24 June 1717 at the Goose & Gridiron ...

, it was in February 1844 that Galton became a freemason

Freemasonry or Masonry refers to fraternal organisations that trace their origins to the local guilds of stonemasons that, from the end of the 13th century, regulated the qualifications of stonemasons and their interaction with authorities ...

at the ''Scientific'' lodge, held at the Red Lion Inn in Cambridge, progressing through the three masonic degrees: Apprentice, 5 February 1844; Fellow Craft, 11 March 1844; Master Mason, 13 May 1844. A note in the record states: "Francis Galton Trinity College student, gained his certificate 13 March 1845". One of Galton's masonic certificates from ''Scientific'' lodge can be found among his papers at University College

In a number of countries, a university college is a college institution that provides tertiary education but does not have full or independent university status. A university college is often part of a larger university. The precise usage varies ...

, London.

A nervous breakdown

A mental disorder, also referred to as a mental illness or psychiatric disorder, is a behavioral or mental pattern that causes significant distress or impairment of personal functioning. Such features may be persistent, relapsing and remitt ...

prevented Galton's intent to try for honours. He elected instead to take a "poll" (pass) B.A. degree, like his half-cousin Charles Darwin. (Following the Cambridge custom, he was awarded an M.A. without further study, in 1847.) He briefly resumed his medical studies but the death of his father in 1844 left him emotionally destitute, though financially independent, and he terminated his medical studies entirely, turning to foreign travel, sport and technical invention.

In his early years Galton was an enthusiastic traveller, and made a notable solo trip through Eastern Europe to Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

, before going up to Cambridge. In 1845 and 1846, he went to Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning the North Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via a land bridg ...

and travelled up the Nile

The Nile, , Bohairic , lg, Kiira , Nobiin: Áman Dawū is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa and has historically been considered the longest riv ...

to Khartoum

Khartoum or Khartum ( ; ar, الخرطوم, Al-Khurṭūm, din, Kaartuɔ̈m) is the capital of Sudan. With a population of 5,274,321, its metropolitan area is the largest in Sudan. It is located at the confluence of the White Nile, flowing n ...

in the Sudan

Sudan ( or ; ar, السودان, as-Sūdān, officially the Republic of the Sudan ( ar, جمهورية السودان, link=no, Jumhūriyyat as-Sūdān), is a country in Northeast Africa. It shares borders with the Central African Republic t ...

, and from there to Beirut

Beirut, french: Beyrouth is the capital and largest city of Lebanon. , Greater Beirut has a population of 2.5 million, which makes it the third-largest city in the Levant region. The city is situated on a peninsula at the midpoint o ...

, Damascus

)), is an adjective which means "spacious".

, motto =

, image_flag = Flag of Damascus.svg

, image_seal = Emblem of Damascus.svg

, seal_type = Seal

, map_caption =

, ...

and down to Jordan

Jordan ( ar, الأردن; tr. ' ), officially the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan,; tr. ' is a country in Western Asia. It is situated at the crossroads of Asia, Africa, and Europe, within the Levant region, on the East Bank of the Jordan Rive ...

.

In 1850 he joined the Royal Geographical Society

The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers), often shortened to RGS, is a learned society and professional body for geography based in the United Kingdom. Founded in 1830 for the advancement of geographical scien ...

, and over the next two years mounted a long and difficult expedition into then little-known South West Africa

South West Africa ( af, Suidwes-Afrika; german: Südwestafrika; nl, Zuidwest-Afrika) was a territory under South African administration from 1915 to 1990, after which it became modern-day Namibia. It bordered Angola (Portuguese colony before 1 ...

(now Namibia

Namibia (, ), officially the Republic of Namibia, is a country in Southern Africa. Its western border is the Atlantic Ocean. It shares land borders with Zambia and Angola to the north, Botswana to the east and South Africa to the south and ea ...

). He wrote a book on his experience, "Narrative of an Explorer in Tropical South Africa". He was awarded the Royal Geographical Society's Founder's Medal in 1853 and the Silver Medal of the French Geographical Society for his pioneering cartographic survey of the region. This established his reputation as a geographer and explorer. He proceeded to write the best-selling ''The Art of Travel'', a handbook of practical advice for the Victorian on the move, which went through many editions and is still in print.

Middle years

Galton was a

Galton was a polymath

A polymath ( el, πολυμαθής, , "having learned much"; la, homo universalis, "universal human") is an individual whose knowledge spans a substantial number of subjects, known to draw on complex bodies of knowledge to solve specific pro ...

who made important contributions in many fields, including meteorology

Meteorology is a branch of the atmospheric sciences (which include atmospheric chemistry and physics) with a major focus on weather forecasting. The study of meteorology dates back millennia, though significant progress in meteorology did no ...

(the anticyclone

An anticyclone is a weather phenomenon defined as a large-scale circulation of winds around a central region of high atmospheric pressure, clockwise in the Northern Hemisphere and counterclockwise in the Southern Hemisphere as viewed from ...

and the first popular weather maps), statistics (regression and correlation), psychology

Psychology is the science, scientific study of mind and behavior. Psychology includes the study of consciousness, conscious and Unconscious mind, unconscious phenomena, including feelings and thoughts. It is an academic discipline of immens ...

(synaesthesia

Synesthesia (American English) or synaesthesia (British English) is a perceptual phenomenon in which stimulation of one sensory or cognitive pathway leads to involuntary experiences in a second sensory or cognitive pathway. People who rep ...

), biology

Biology is the scientific study of life. It is a natural science with a broad scope but has several unifying themes that tie it together as a single, coherent field. For instance, all organisms are made up of cells that process hereditary ...

(the nature and mechanism of heredity), and criminology

Criminology (from Latin , "accusation", and Ancient Greek , ''-logia'', from λόγος ''logos'' meaning: "word, reason") is the study of crime and deviant behaviour. Criminology is an interdisciplinary field in both the behavioural and s ...

(fingerprints). Much of this was influenced by his penchant for counting and measuring. Galton prepared the first weather map

A weather map, also known as synoptic weather chart, displays various meteorological features across a particular area at a particular point in time and has various symbols which all have specific meanings. Such maps have been in use since the mi ...

published in ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper '' The Sunday Times'' ( ...

'' (1 April 1875, showing the weather from the previous day, 31 March), now a standard feature in newspapers worldwide.

He became very active in the British Association for the Advancement of Science

The British Science Association (BSA) is a charity and learned society founded in 1831 to aid in the promotion and development of science. Until 2009 it was known as the British Association for the Advancement of Science (BA). The current Chi ...

, presenting many papers on a wide variety of topics at its meetings from 1858 to 1899. He was the general secretary from 1863 to 1867, president of the Geographical section in 1867 and 1872, and president of the Anthropological Section in 1877 and 1885. He was active on the council of the Royal Geographical Society for over forty years, in various committees of the Royal Society, and on the Meteorological Council.

James McKeen Cattell

James is a common English language surname and given name:

*James (name), the typically masculine first name James

* James (surname), various people with the last name James

James or James City may also refer to:

People

* King James (disambiguat ...

, a student of Wilhelm Wundt

Wilhelm Maximilian Wundt (; ; 16 August 1832 – 31 August 1920) was a German physiologist, philosopher, and professor, known today as one of the fathers of modern psychology. Wundt, who distinguished psychology as a science from philosophy and ...

who had been reading Galton's articles, decided he wanted to study under him. He eventually built a professional relationship with Galton, measuring subjects and working together on research.

In 1888, Galton established a lab in the science galleries of the South Kensington Museum. In Galton's lab, participants could be measured to gain knowledge of their strengths and weaknesses. Galton also used these data for his own research. He would typically charge people a small fee for his services.

In 1873, Galton wrote a controversial letter to ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper '' The Sunday Times'' ( ...

'' titled 'Africa for the Chinese', where he argued that the Chinese, as a race capable of high civilization and only temporarily stunted by the recent failures of Chinese dynasties, should be encouraged to immigrate to Africa and displace the supposedly inferior aboriginal blacks.

Heredity and eugenics

The publication by his cousin Charles Darwin of '' The Origin of Species'' in 1859 was an event that changed Galton's life. He came to be gripped by the work, especially the first chapter on "Variation under Domestication", concerninganimal breeding

Animal breeding is a branch of animal science that addresses the evaluation (using best linear unbiased prediction and other methods) of the genetic value (estimated breeding value, EBV) of livestock. Selecting for breeding animals with superior E ...

.

Galton devoted much of the rest of his life to exploring variation in human populations and its implications, at which Darwin had only hinted in ''The Origin of Species'', although he returned to it in his 1871 book ''The Descent of Man

''The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex'' is a book by English naturalist Charles Darwin, first published in 1871, which applies evolutionary theory to human evolution, and details his theory of sexual selection, a form of biol ...

'', drawing on his cousin's work in the intervening period. Galton established a research program which embraced multiple aspects of human variation, from mental characteristics to height; from facial images to fingerprint patterns. This required inventing novel measures of traits, devising large-scale collection of data using those measures, and in the end, the discovery of new statistical techniques for describing and understanding the data.

Galton was interested at first in the question of whether human ability was hereditary

Heredity, also called inheritance or biological inheritance, is the passing on of traits from parents to their offspring; either through asexual reproduction or sexual reproduction, the offspring cells or organisms acquire the genetic informa ...

, and proposed to count the number of the relatives of various degrees of eminent men. If the qualities were hereditary, he reasoned, there should be more eminent men among the relatives than among the general population. To test this, he invented the methods of historiometry

Historiometry is the historical study of human progress or individual personal characteristics, using statistics to analyze references to geniuses, their statements, behavior and discoveries in relatively neutral texts. Historiometry combines techn ...

. Galton obtained extensive data from a broad range of biographical sources which he tabulated and compared in various ways. This pioneering work was described in detail in his book ''Hereditary Genius'' in 1869. Here he showed, among other things, that the numbers of eminent relatives dropped off when going from the first degree to the second degree relatives, and from the second degree to the third. He took this as evidence of the inheritance of abilities.

Galton recognized the limitations of his methods in these two works, and believed the question could be better studied by comparisons of twins. His method envisaged testing to see if twins who were similar at birth diverged in dissimilar environments, and whether twins dissimilar at birth converged when reared in similar environments. He again used the method of questionnaires to gather various sorts of data, which were tabulated and described in a paper ''The history of twins'' in 1875. In so doing he anticipated the modern field of behaviour genetics

Behavioural genetics, also referred to as behaviour genetics, is a field of scientific research that uses genetic methods to investigate the nature and origins of individual differences in behaviour. While the name "behavioural genetics" co ...

, which relies heavily on twin studies. He concluded that the evidence favored nature rather than nurture. He also proposed adoption studies, including trans-racial adoption studies, to separate the effects of heredity and environment.

Galton recognized that cultural circumstances influenced the capability of a civilization's citizens, and their reproductive success. In ''Hereditary Genius'', he envisaged a situation conducive to resilient and enduring civilization as follows:

Galton invented the term ''eugenics

Eugenics ( ; ) is a fringe set of beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetic quality of a human population. Historically, eugenicists have attempted to alter human gene pools by excluding people and groups judged to be inferior o ...

'' in 1883 and set down many of his observations and conclusions in a book, ''Inquiries into Human Faculty and Its Development

''Inquiries into Human Faculty and Its Development'' is an 1883 book by Francis Galton, in which he covers a variety of psychological phenomena and their subsequent measurement. In this text he also references the idea of eugenics

Eugenics ...

''. In the book's introduction, he wrote:

He believed that a scheme of 'marks' for family merit should be defined, and early marriage between families of high rank be encouraged via provision of monetary incentives. He pointed out some of the tendencies in British society, such as the late marriages of eminent people, and the paucity of their children, which he thought were ''dysgenic

Dysgenics (also known as cacogenics) is the decrease in prevalence of traits deemed to be either socially desirable or well adapted to their environment due to selective pressure disfavoring the reproduction of those traits.

The adjective "dysgeni ...

''. He advocated encouraging eugenic marriages by supplying able couples with incentives to have children. On 29 October 1901, Galton chose to address eugenic issues when he delivered the second Huxley lecture at the Royal Anthropological Institute.

''The Eugenics Review

The ''Journal of Biosocial Science'' is a bimonthly peer-reviewed scientific journal covering the intersection of biology and sociology. It was the continuation of ''The Eugenics Review'', published by the Galton Institute from 1909 till 1968. It ...

'', the journal of the Eugenics Education Society, commenced publication in 1909. Galton, the Honorary President of the society, wrote the foreword for the first volume. The First International Congress of Eugenics was held in July 1912. Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

and Carls Elliot were among the attendees.

According to the ''Encyclopedia of Genocide

Israel W. Charny (born 1931) is an Israeli psychologist and genocide scholar. He is the editor of two-volume ''Encyclopedia of Genocide'', and executive director of the Institute on the Holocaust and Genocide in Jerusalem.

Background

Israel ...

'', Galton bordered on the justification of genocide when he stated: "There exists a sentiment, for the most part quite unreasonable, against the gradual extinction of an inferior race."

In June 2020, UCL announced the renaming of a lecture theatre named after Galton because of his connection with eugenics.

Model for population stability

Galton's formulation of regression and its link to the bivariate normal distribution can be traced to his attempts at developing a mathematical model for population stability. Although Galton's first attempt to study Darwinian questions, ''Hereditary Genius'', generated little enthusiasm at the time, the text led to his further studies in the 1870s concerning the inheritance of physical traits. This text contains some crude notions of the concept of regression, described in a qualitative matter. For example, he wrote of dogs: "If a man breeds from strong, well-shaped dogs, but of mixed pedigree, the puppies will be sometimes, but rarely, the equals of their parents. They will commonly be of a mongrel, nondescript type, because ancestral peculiarities are apt to crop out in the offspring."

This notion created a problem for Galton, as he could not reconcile the tendency of a population to maintain a normal distribution of traits from generation to generation with the notion of inheritance. It seemed that a large number of factors operated independently on offspring, leading to the normal distribution of a trait in each generation. However, this provided no explanation as to how a parent can have a significant impact on his offspring, which was the basis of inheritance.

Galton's solution to this problem was presented in his Presidential Address at the September 1885 meeting of the

Galton's formulation of regression and its link to the bivariate normal distribution can be traced to his attempts at developing a mathematical model for population stability. Although Galton's first attempt to study Darwinian questions, ''Hereditary Genius'', generated little enthusiasm at the time, the text led to his further studies in the 1870s concerning the inheritance of physical traits. This text contains some crude notions of the concept of regression, described in a qualitative matter. For example, he wrote of dogs: "If a man breeds from strong, well-shaped dogs, but of mixed pedigree, the puppies will be sometimes, but rarely, the equals of their parents. They will commonly be of a mongrel, nondescript type, because ancestral peculiarities are apt to crop out in the offspring."

This notion created a problem for Galton, as he could not reconcile the tendency of a population to maintain a normal distribution of traits from generation to generation with the notion of inheritance. It seemed that a large number of factors operated independently on offspring, leading to the normal distribution of a trait in each generation. However, this provided no explanation as to how a parent can have a significant impact on his offspring, which was the basis of inheritance.

Galton's solution to this problem was presented in his Presidential Address at the September 1885 meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science

The British Science Association (BSA) is a charity and learned society founded in 1831 to aid in the promotion and development of science. Until 2009 it was known as the British Association for the Advancement of Science (BA). The current Chi ...

, as he was serving at the time as President of Section H: Anthropology. The address was published in ''Nature

Nature, in the broadest sense, is the physical world or universe. "Nature" can refer to the phenomena of the physical world, and also to life in general. The study of nature is a large, if not the only, part of science. Although humans are ...

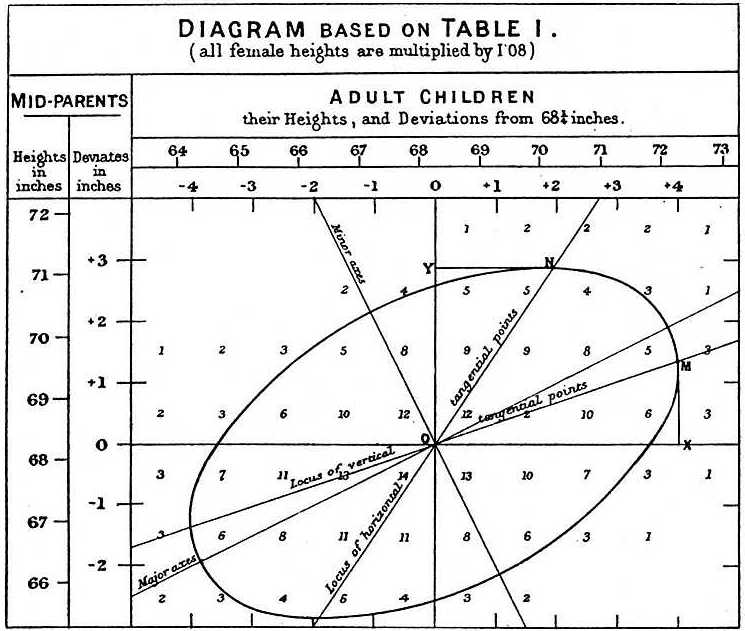

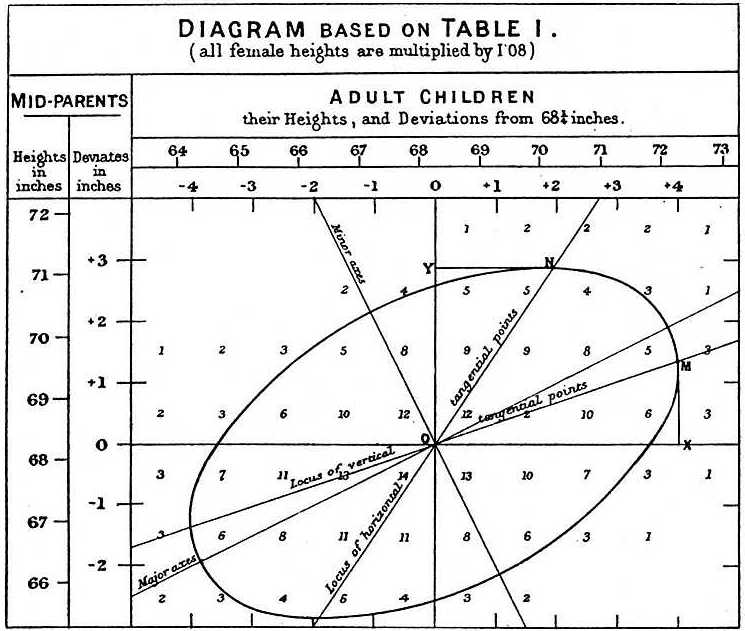

,'' and Galton further developed the theory in "Regression toward mediocrity in hereditary stature" and "Hereditary Stature." An elaboration of this theory was published in 1889 in ''Natural Inheritance.'' There were three key developments that helped Galton develop this theory: the development of the law of error in 1874–1875, the formulation of an empirical law of reversion in 1877, and the development of a mathematical framework encompassing regression using human population data during 1885.

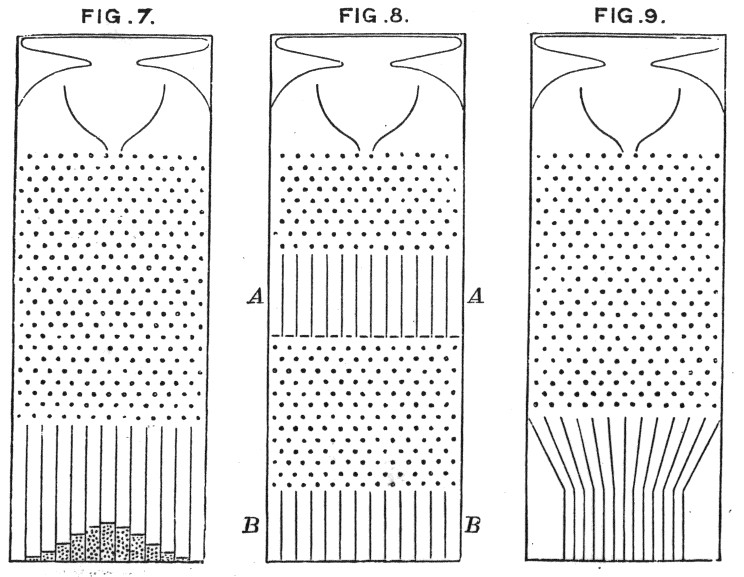

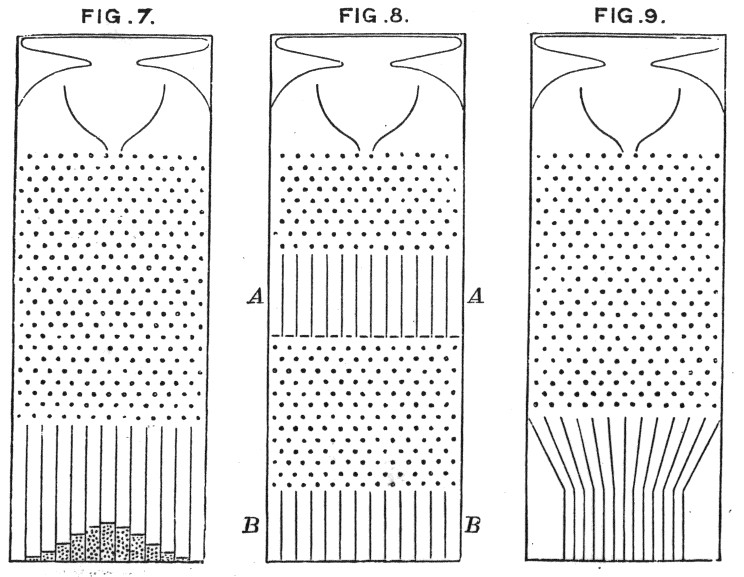

Galton's development of the law of regression to the mean, or reversion, was due to insights from the Galton board ('bean machine') and his studies of sweet peas. While Galton had previously invented the quincunx prior to February 1874, the 1877 version of the quincunx had a new feature that helped Galton demonstrate that a normal mixture of normal distributions is also normal. Galton demonstrated this using a new version of quincunx, adding chutes to the apparatus to represent reversion. When the pellets passed through the curved chutes (representing reversion) and then the pins (representing family variability), the result was a stable population. On Friday 19 February 1877 Galton gave a lecture entitled ''Typical Laws of Heredity'' at the Royal Institution

The Royal Institution of Great Britain (often the Royal Institution, Ri or RI) is an organisation for scientific education and research, based in the City of Westminster. It was founded in 1799 by the leading British scientists of the age, inc ...

in London. In this lecture, he posited that there must be a counteracting force to maintain population stability. However, this model required a much larger degree of intergenerational natural selection than was plausible.

In 1875, Galton started growing sweet peas, and addressed the Royal Institution on his findings on 9 February 1877. He found that each group of progeny seeds followed a normal curve, and the curves were equally disperse. Each group was not centered about the parent's weight, but rather at a weight closer to the population average. Galton called this reversion, as every progeny group was distributed at a value that was closer to the population average than the parent. The deviation from the population average was in the same direction, but the magnitude of the deviation was only one-third as large. In doing so, Galton demonstrated that there was variability among each of the families, yet the families combined to produce a stable, normally distributed population. When Galton addressed the British Association for the Advancement of Science in 1885, he said of his investigation of sweet peas, "I was then blind to what I now perceive to be the simple explanation of the phenomenon."

Galton was able to further his notion of regression by collecting and analyzing data on human stature. Galton asked for help of mathematician J. Hamilton Dickson in investigating the geometric relationship of the data. He determined that the regression coefficient did not ensure population stability by chance, but rather that the regression coefficient, conditional variance, and population were interdependent quantities related by a simple equation. Thus Galton identified that the linearity of regression was not coincidental but rather was a necessary consequence of population stability.

The model for population stability resulted in Galton's formulation of the Law of Ancestral Heredity. This law, which was published in ''Natural Inheritance,'' states that the two parents of an offspring jointly contribute one half of an offspring's heritage, while the other, more-removed ancestors constitute a smaller proportion of the offspring's heritage. Galton viewed reversion as a spring, that when stretched, would return the distribution of traits back to the normal distribution. He concluded that evolution would have to occur via discontinuous steps, as reversion would neutralize any incremental steps. When Mendel's principles were rediscovered in 1900, this resulted in a fierce battle between the followers of Galton's Law of Ancestral Heredity, the biometricians, and those who advocated Mendel's principles.

Empirical test of pangenesis and Lamarckism

Galton conducted wide-ranging inquiries into heredity which led him to challenge Charles Darwin's hypothesis ofpangenesis

Pangenesis was Charles Darwin's hypothetical mechanism for heredity, in which he proposed that each part of the body continually emitted its own type of small organic particles called gemmules that aggregated in the gonads, contributing herita ...

. Darwin had proposed as part of this model that certain particles, which he called "gemmules

Pangenesis was Charles Darwin's hypothetical mechanism for heredity, in which he proposed that each part of the body continually emitted its own type of small organic particles called gemmules that aggregated in the gonads, contributing heritabl ...

" moved throughout the body and were also responsible for the inheritance of acquired characteristics. Galton, in consultation with Darwin, set out to see if they were transported in the blood. In a long series of experiments in 1869 to 1871, he transfused the blood between dissimilar breeds of rabbits, and examined the features of their offspring. He found no evidence of characters transmitted in the transfused blood.

Darwin challenged the validity of Galton's experiment, giving his reasons in an article published in ''Nature

Nature, in the broadest sense, is the physical world or universe. "Nature" can refer to the phenomena of the physical world, and also to life in general. The study of nature is a large, if not the only, part of science. Although humans are ...

'' where he wrote:

Galton explicitly rejected the idea of the inheritance of acquired characteristics (Lamarckism

Lamarckism, also known as Lamarckian inheritance or neo-Lamarckism, is the notion that an organism can pass on to its offspring physical characteristics that the parent organism acquired through use or disuse during its lifetime. It is also calle ...

), and was an early proponent of "hard heredity" through selection alone. He came close to rediscovering Mendel's particulate theory of inheritance, but was prevented from making the final breakthrough in this regard because of his focus on continuous, rather than discrete, traits (now regarded as polygenic

A polygene is a member of a group of non- epistatic genes that interact additively to influence a phenotypic trait, thus contributing to multiple-gene inheritance (polygenic inheritance, multigenic inheritance, quantitative inheritance), a type of ...

traits). He went on to found the biometric

Biometrics are body measurements and calculations related to human characteristics. Biometric authentication (or realistic authentication) is used in computer science as a form of identification and access control. It is also used to identify in ...

approach to the study of heredity, distinguished by its use of statistical techniques to study continuous traits and population-scale aspects of heredity.

This approach was later taken up enthusiastically by Karl Pearson

Karl Pearson (; born Carl Pearson; 27 March 1857 – 27 April 1936) was an English mathematician and biostatistician. He has been credited with establishing the discipline of mathematical statistics. He founded the world's first university st ...

and W. F. R. Weldon; together, they founded the highly influential journal ''Biometrika

''Biometrika'' is a peer-reviewed scientific journal published by Oxford University Press for thBiometrika Trust The editor-in-chief is Paul Fearnhead ( Lancaster University). The principal focus of this journal is theoretical statistics. It was ...

'' in 1901. (R. A. Fisher

Sir Ronald Aylmer Fisher (17 February 1890 – 29 July 1962) was a British polymath who was active as a mathematician, statistician, biologist, geneticist, and academic. For his work in statistics, he has been described as "a genius who a ...

would later show how the biometrical approach could be reconciled with the Mendelian approach.) The statistical techniques that Galton invented (correlation and regression—see below) and phenomena he established (regression to the mean) formed the basis of the biometric approach and are now essential tools in all social sciences.

Anthropometric Laboratory at the 1884 International Health Exhibition

In 1884, London hosted the International Health Exhibition. This exhibition placed much emphasis on highlighting Victorian developments in sanitation and public health, and allowed the nation to display its advanced public health outreach, compared to other countries at the time. Francis Galton took advantage of this opportunity to set up his anthropometric laboratory. He stated that the purpose of this laboratory was to "show the public the simplicity of the instruments and methods by which the chief physical characteristics of man may be measured and recorded." The laboratory was an interactive walk-through in which physical characteristics such as height, weight, and eyesight, would be measured for each subject after payment of an admission fee. Upon entering the laboratory, a subject would visit the following stations in order. First, they would fill out a form with personal and family history (age, birthplace, marital status, residence, and occupation), then visit stations that recorded hair and eye color, followed by the keenness, color-sense, and depth perception of sight. Next, they would examine the keenness, or relative acuteness, of hearing and highest audible note of their hearing followed by an examination of their sense of touch. However, because the surrounding area was noisy, the apparatus intended to measure hearing was rendered ineffective by the noise and echoes in the building. Their breathing capacity would also be measured, as well as their ability to throw a punch. The next stations would examine strength of both pulling and squeezing with both hands. Lastly, subjects' heights in various positions (sitting, standing, etc.) as well as arm span and weight would be measured. One excluded characteristic of interest was the size of the head. Galton notes in his analysis that this omission was mostly for practical reasons. For instance, it would not be very accurate and additionally it would require much time for women to disassemble and reassemble their hair and bonnets. The patrons would then be given a souvenir containing all their biological data, while Galton would also keep a copy for future statistical research. Although the laboratory did not employ any revolutionary measurement techniques, it was unique because of the simple logistics of constructing such a demonstration within a limited space, and because of the speed and efficiency with which all the necessary data were gathered. The laboratory itself was a see-through (lattice-walled) fenced off gallery measuring 36 feet long by 6 feet long. To collect data efficiently, Galton had to make the process as simple as possible for people to understand. As a result, subjects were taken through the laboratory in pairs so that explanations could be given to two at a time, also in the hope that one of the two would confidently take the initiative to go through all the tests first, encouraging the other. With this design, the total time spent in the exhibit was fourteen minutes for each pair. Galton states that the measurements of human characteristics are useful for two reasons. First, he states that measuring physical characteristics is useful in order to ensure, on a more domestic level, that children are developing properly. A useful example he gives for the practicality of these domestic measurements is regularly checking a child's eyesight, in order to correct any deficiencies early on. The second use for the data from his anthropometric laboratory is for statistical studies. He comments on the usefulness of the collected data to compare attributes across occupations, residences, races, etc. The exhibit at the health exhibition allowed Galton to collect a large amount of raw data from which to conduct further comparative studies. He had 9,337 respondents, each measured in 17 categories, creating a rather comprehensive statistical database. After the conclusion of the International Health Exhibition, Galton used these data to confirm in humans his theory of linear regression, posed after studying sweet peas. The accumulation of this human data allowed him to observe the correlation between forearm length and height, head width and head breadth, and head length and height. With these observations he was able to write ''Co-relations and their Measurements, chiefly from Anthropometric Data''. In this publication, Galton defined what co-relation as a phenomenon that occurs when "the variation of the one ariableis accompanied on the average by more or less variation of the other, and in the same direction."Innovations in statistics and psychological theory

Historiometry

The method used in ''Hereditary Genius'' has been described as the first example ofhistoriometry

Historiometry is the historical study of human progress or individual personal characteristics, using statistics to analyze references to geniuses, their statements, behavior and discoveries in relatively neutral texts. Historiometry combines techn ...

. To bolster these results, and to attempt to make a distinction between 'nature' and 'nurture' (he was the first to apply this phrase to the topic), he devised a questionnaire that he sent out to 190 Fellows of the Royal Society

Fellowship of the Royal Society (FRS, ForMemRS and HonFRS) is an award granted by the judges of the Royal Society of London to individuals who have made a "substantial contribution to the improvement of natural knowledge, including mathemati ...

. He tabulated characteristics of their families, such as birth order and the occupation and race of their parents. He attempted to discover whether their interest in science was 'innate' or due to the encouragements of others. The studies were published as a book, ''English men of science: their nature and nurture'', in 1874. In the end, it promoted the nature versus nurture

Nature versus nurture is a long-standing debate in biology and society about the balance between two competing factors which determine fate: genetics (nature) and environment (nurture). The alliterative expression "nature and nurture" in English h ...

question, though it did not settle it, and provided some fascinating data on the sociology of scientists of the time.

The lexical hypothesis

Sir Francis was the first scientist to recognise what is now known as thelexical hypothesis

The lexical hypothesis (also known as the fundamental lexical hypothesis, lexical approach, or sedimentation hypothesis) is a thesis, current primarily in early personality psychology, and subsequently subsumed by many later efforts in that subfie ...

. This is the idea that the most salient and socially relevant personality differences in people's lives will eventually become encoded into language. The hypothesis further suggests that by sampling language, it is possible to derive a comprehensive taxonomy of human personality traits

In psychology, trait theory (also called dispositional theory) is an approach to the study of human personality. Trait theorists are primarily interested in the measurement of ''traits'', which can be defined as habitual patterns of behaviour, ...

.

The questionnaire

Galton's inquiries into the mind involved detailed recording of people's subjective accounts of whether and how their minds dealt with phenomena such as mental imagery. To better elicit this information, he pioneered the use of thequestionnaire

A questionnaire is a research instrument that consists of a set of questions (or other types of prompts) for the purpose of gathering information from respondents through survey or statistical study. A research questionnaire is typically a mix ...

. In one study, he asked his fellow members of the Royal Society of London to describe mental images that they experienced. In another, he collected in-depth surveys from eminent scientists for a work examining the effects of nature and nurture on the propensity toward scientific thinking.

Variance and standard deviation

Core to any statistical analysis is the concept that measurements vary: they have both acentral tendency

In statistics, a central tendency (or measure of central tendency) is a central or typical value for a probability distribution.Weisberg H.F (1992) ''Central Tendency and Variability'', Sage University Paper Series on Quantitative Applications in ...

, or mean, and a spread around this central value, or variance

In probability theory and statistics, variance is the expectation of the squared deviation of a random variable from its population mean or sample mean. Variance is a measure of dispersion, meaning it is a measure of how far a set of numbe ...

. In the late 1860s, Galton conceived of a measure to quantify normal variation: the standard deviation

In statistics, the standard deviation is a measure of the amount of variation or dispersion of a set of values. A low standard deviation indicates that the values tend to be close to the mean (also called the expected value) of the set, whil ...

.

Galton was a keen observer. In 1906, visiting a livestock fair, he stumbled upon an intriguing contest. An ox was on display, and the villagers were invited to guess the animal's weight after it was slaughtered and dressed. Nearly 800 participated, and Galton was able to study their individual entries after the event. Galton stated that "the middlemost estimate expresses the ''vox populi'', every other estimate being condemned as too low or too high by a majority of the voters", and reported this value (the median

In statistics and probability theory, the median is the value separating the higher half from the lower half of a data sample, a population, or a probability distribution. For a data set, it may be thought of as "the middle" value. The basic f ...

, in terminology he himself had introduced, but chose not to use on this occasion) as 1,207 pounds. To his surprise, this was within 0.8% of the weight measured by the judges. Soon afterwards, in response to an enquiry, he reported the mean of the guesses as 1,197 pounds, but did not comment on its improved accuracy. Recent archival research has found some slips in transmitting Galton's calculations to the original article in ''Nature'': the median was actually 1,208 pounds, and the dressed weight of the ox 1,197 pounds, so the mean estimate had zero error. James Surowiecki uses this weight-judging competition as his opening example: had he known the true result, his conclusion on the wisdom of the crowd would no doubt have been more strongly expressed.

The same year, Galton suggested in a letter to the journal ''Nature

Nature, in the broadest sense, is the physical world or universe. "Nature" can refer to the phenomena of the physical world, and also to life in general. The study of nature is a large, if not the only, part of science. Although humans are ...

'' a better method of cutting a round cake by avoiding making radial incisions.

Experimental derivation of the normal distribution

Studying variation, Galton invented the Galton board, a

Studying variation, Galton invented the Galton board, a pachinko

is a mechanical game originating in Japan that is used as an arcade game, and much more frequently for gambling. Pachinko fills a niche in Japanese gambling comparable to that of the slot machine in the West as a form of low-stakes, low-st ...

-like device also known as the bean machine, as a tool for demonstrating the law of error and the normal distribution

In statistics, a normal distribution or Gaussian distribution is a type of continuous probability distribution for a real-valued random variable. The general form of its probability density function is

:

f(x) = \frac e^

The parameter \mu ...

.

Bivariate normal distribution

He also discovered the properties of the bivariate normal distribution and its relationship tocorrelation

In statistics, correlation or dependence is any statistical relationship, whether causal or not, between two random variables or bivariate data. Although in the broadest sense, "correlation" may indicate any type of association, in statistic ...

and regression analysis

In statistical modeling, regression analysis is a set of statistical processes for estimating the relationships between a dependent variable (often called the 'outcome' or 'response' variable, or a 'label' in machine learning parlance) and one ...

.

Correlation and regression

In 1846, the French physicist Auguste Bravais (1811–1863) first developed what would become the correlation coefficient. After examining forearm and height measurements, Galton independently rediscovered the concept of

In 1846, the French physicist Auguste Bravais (1811–1863) first developed what would become the correlation coefficient. After examining forearm and height measurements, Galton independently rediscovered the concept of correlation

In statistics, correlation or dependence is any statistical relationship, whether causal or not, between two random variables or bivariate data. Although in the broadest sense, "correlation" may indicate any type of association, in statistic ...

in 1888 and demonstrated its application in the study of heredity, anthropology, and psychology. Galton's later statistical study of the probability of extinction of surnames led to the concept of Galton–Watson stochastic processes.

Galton invented the use of the regression line and for the choice of r (for reversion or regression) to represent the correlation coefficient.

In the 1870s and 1880s he was a pioneer in the use of normal theory to fit histogram

A histogram is an approximate representation of the frequency distribution, distribution of numerical data. The term was first introduced by Karl Pearson. To construct a histogram, the first step is to "Data binning, bin" (or "Data binning, buck ...

s and ogives

The ''Ogives'' are four pieces for piano composed by Erik Satie in the late 1880s. They were published in 1889, and were the first compositions by Satie he did not publish in his father's music publishing house.

Satie was said to have been insp ...

to actual tabulated data, much of which he collected himself: for instance large samples of sibling and parental height. Consideration of the results from these empirical studies led to his further insights into evolution, natural selection, and regression to the mean.

Regression toward the mean

Galton was the first to describe and explain the common phenomenon ofregression toward the mean

In statistics, regression toward the mean (also called reversion to the mean, and reversion to mediocrity) is the fact that if one sample of a random variable is extreme, the next sampling of the same random variable is likely to be closer to it ...

, which he first observed in his experiments on the size of the seeds of successive generations of sweet peas.

The conditions under which regression toward the mean occurs depend on the way the term is mathematically defined. Galton first observed the phenomenon in the context of simple linear regression

In statistics, simple linear regression is a linear regression model with a single explanatory variable. That is, it concerns two-dimensional sample points with one independent variable and one dependent variable (conventionally, the ''x'' and ...

of data points. Galton developed the following model: pellets fall through a ''quincunx

A quincunx () is a geometric pattern consisting of five points arranged in a cross, with four of them forming a square or rectangle and a fifth at its center. The same pattern has other names, including "in saltire" or "in cross" in heraldry (d ...

'' or " bean machine" forming a normal distribution centered directly under their entrance point. These pellets could then be released down into a second gallery (corresponding to a second measurement occasion). Galton then asked the reverse question "from where did these pellets come?"

Theories of perception

Galton went beyond measurement and summary to attempt to explain the phenomena he observed. Among such developments, he proposed an early theory of ranges of sound andhearing

Hearing, or auditory perception, is the ability to perceive sounds through an organ, such as an ear, by detecting vibrations as periodic changes in the pressure of a surrounding medium. The academic field concerned with hearing is audit ...

, and collected large quantities of anthropometric data from the public through his popular and long-running Anthropometric Laboratory, which he established in 1884, and where he studied over 9,000 people. It was not until 1985 that these data were analysed in their entirety.

He made a beauty map of Britain, based on a secret grading of the local women on a scale from attractive to repulsive. The lowest point was in Aberdeen

Aberdeen (; sco, Aiberdeen ; gd, Obar Dheathain ; la, Aberdonia) is a city in North East Scotland, and is the third most populous city in the country. Aberdeen is one of Scotland's 32 local government council areas (as Aberdeen City), a ...

.

Differential psychology

Galton's study of human abilities ultimately led to the foundation ofdifferential psychology

Differential psychology studies the ways in which individuals differ in their behavior and the processes that underlie it. This is a discipline that develops classifications (taxonomies) of psychological individual differences. This is distingui ...

and the formulation of the first mental tests. He was interested in measuring humans in every way possible. This included measuring their ability to make sensory discrimination which he assumed was linked to intellectual prowess. Galton suggested that individual differences in general ability are reflected in performance on relatively simple sensory capacities and in speed of reaction to a stimulus, variables that could be objectively measured by tests of sensory discrimination and reaction

time. He also measured how quickly people reacted which he later linked to internal wiring which ultimately limited intelligence ability. Throughout his research Galton assumed that people who reacted faster were more intelligent than others.

Composite photography

Galton also devised a technique called " composite portraiture" (produced by superimposing multiple photographic portraits of individuals' faces registered on their eyes) to create an average face (seeaverageness

In physical attractiveness studies, averageness describes the physical beauty that results from averaging the facial features of people of the same gender and approximately the same age.Langlois, J.H., Musselman, L. (1995). The myths and mysteries ...

). In the 1990s, a hundred years after his discovery, much psychological research has examined the attractiveness of these faces, an aspect that Galton had remarked on in his original lecture. Others, including Sigmund Freud

Sigmund Freud ( , ; born Sigismund Schlomo Freud; 6 May 1856 – 23 September 1939) was an Austrian neurologist and the founder of psychoanalysis, a clinical method for evaluating and treating pathologies explained as originating in conflicts i ...

in his work on dreams, picked up Galton's suggestion that these composites might represent a useful metaphor for an Ideal type

Ideal type (german: Idealtypus), also known as pure type, is a typological term most closely associated with sociologist Max Weber (1864–1920). For Weber, the conduct of social science depends upon the construction of abstract, hypothetical con ...

or a concept

Concepts are defined as abstract ideas. They are understood to be the fundamental building blocks of the concept behind principles, thoughts and beliefs.

They play an important role in all aspects of cognition. As such, concepts are studied by ...

of a "natural kind

"Natural kind" is an intellectual grouping, or categorizing of things, in a manner that is reflective of the actual world and not just human interests. Some treat it as a classification identifying some structure of truth and reality that exists wh ...

" (see Eleanor Rosch)—such as Jewish men, criminals, patients with tuberculosis, etc.—onto the same photographic plate, thereby yielding a blended whole, or "composite", that he hoped could generalise the facial appearance of his subject into an "average" or "central type". (See also entry ''Modern physiognomy'' under Physiognomy

Physiognomy (from the Greek , , meaning "nature", and , meaning "judge" or "interpreter") is the practice of assessing a person's character or personality from their outer appearance—especially the face. The term can also refer to the genera ...

).

This work began in the 1880s while the Jewish scholar Joseph Jacobs

Joseph Jacobs (29 August 1854 – 30 January 1916) was an Australian folklorist, translator, literary critic, social scientist, historian and writer of English literature who became a notable collector and publisher of English folklore.

Jacobs ...

studied anthropology and statistics with Francis Galton. Jacobs asked Galton to create a composite photograph of a Jewish type. One of Jacobs' first publications that used Galton's composite imagery was "The Jewish Type, and Galton's Composite Photographs," ''Photographic News'', 29, (24 April 1885): 268–269.

Galton hoped his technique would aid medical diagnosis, and even criminology through the identification of typical criminal faces. However, his technique did not prove useful and fell into disuse, although after much work on it including by photographers Lewis Hine and John L. Lovell and Arthur Batut

Arthur Batut (9 February 1846 – 19 January 1918) was a French photographer and pioneer of aerial photography..

Life

Batut was born in 1846 in Castres, and developed interest in history, archeology and photography. His book on kite aerial photog ...

.

Fingerprints

The method of identifying criminals by their fingerprints had been introduced in the 1860s by SirWilliam James Herschel

Sir William James Herschel, 2nd Baronet (9 January 1833 – 24 October 1917)"Michele Triplett's Fingerprint Dictionary: H" (glossary), Michele Triplett, 2006, ''Fprints.nwlean.net'' webpage was a British ICS officer in India who used fingerprin ...

in India, and their potential use in forensic work was first proposed by Dr Henry Faulds

Henry Faulds (1 June 1843 – 24 March 1930) was a Scottish doctor, missionary and scientist who is noted for the development of fingerprinting.

Early life

Faulds was born in Beith, North Ayrshire, into a family of modest means. Aged 13, he wa ...

in 1880. Galton was introduced to the field by his half-cousin Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended ...

, who was a friend of Faulds's, and he went on to create the first scientific footing for the study (which assisted its acceptance by the courts) although Galton did not ever give credit that the original idea was not his.

In a Royal Institution

The Royal Institution of Great Britain (often the Royal Institution, Ri or RI) is an organisation for scientific education and research, based in the City of Westminster. It was founded in 1799 by the leading British scientists of the age, inc ...

paper in 1888 and three books ('' Finger Prints'', 1892; ''Decipherment of Blurred Finger Prints'', 1893; and ''Fingerprint Directories'', 1895), Galton estimated the probability of two persons having the same fingerprint

A fingerprint is an impression left by the friction ridges of a human finger. The recovery of partial fingerprints from a crime scene is an important method of forensic science. Moisture and grease on a finger result in fingerprints on surfac ...