After the

Russian Revolution

The Russian Revolution was a period of political and social revolution that took place in the former Russian Empire which began during the First World War. This period saw Russia abolish its monarchy and adopt a socialist form of government ...

, in which the Bolsheviks took over parts of the collapsing

Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War ...

in 1918, they faced enormous odds against the

German Empire

The German Empire (),Herbert Tuttle wrote in September 1881 that the term "Reich" does not literally connote an empire as has been commonly assumed by English-speaking people. The term literally denotes an empire – particularly a hereditary ...

and eventually negotiated terms to pull out of

World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

. They then went to war against both

domestic and

international enemies in the

bitter civil war. They set up the

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

in 1922 with

Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 1 ...

in charge. At first, it was treated as an unrecognized

pariah state because of its

repudiating of tsarist debts and threats to destroy capitalism at home and around the world. By 1922, Moscow had repudiated the goal of world revolution, and sought diplomatic recognition and friendly trade relations with the capitalist world, starting with Britain and Germany. Finally in 1933, the United States gave recognition. Trade and technical help from Germany and the United States arrived in the late 1920s. After Lenin died in 1924,

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet Union, Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as Ge ...

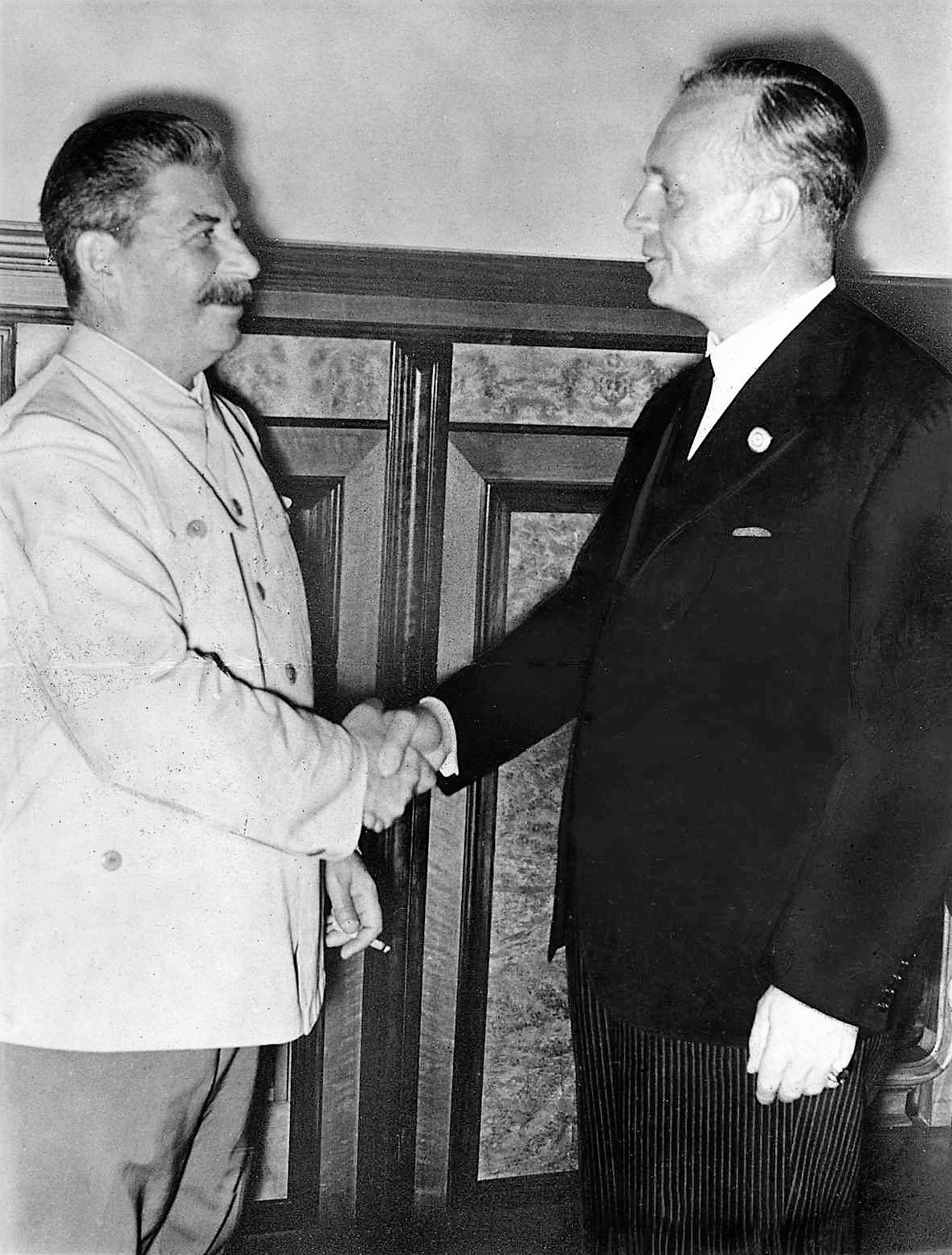

, became leader and then the dictator. He transformed the country in the 1930s into an industrial and military power. It strongly opposed Nazi Germany until August 1939, when it suddenly came to friendly terms with Berlin in the

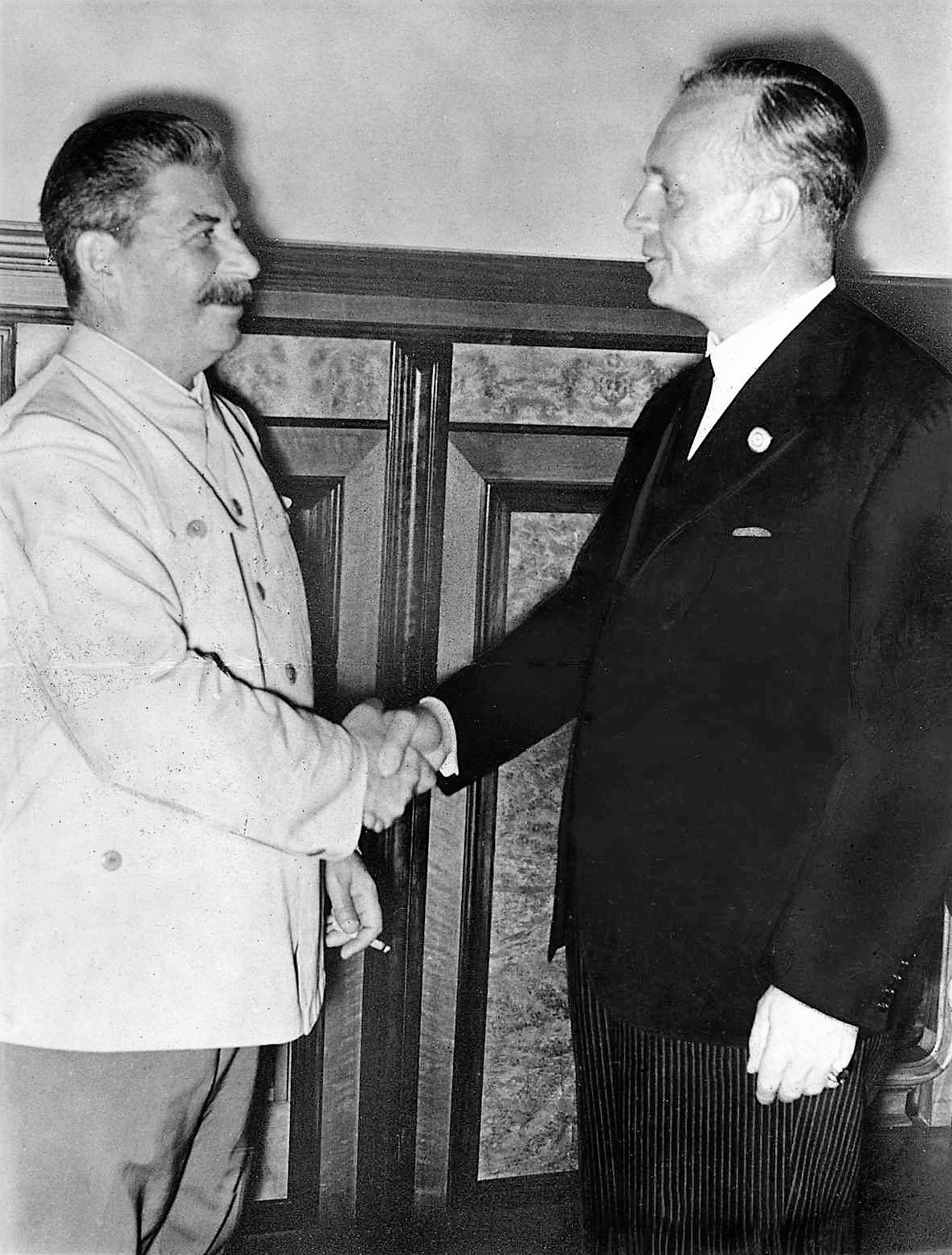

Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact

, long_name = Treaty of Non-Aggression between Germany and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics

, image = Bundesarchiv Bild 183-H27337, Moskau, Stalin und Ribbentrop im Kreml.jpg

, image_width = 200

, caption = Stalin and Ribbentrop shaking ...

. Moscow and Berlin by agreement divided up Poland and the Baltic nations. Stalin ignored repeated warnings that Hitler planned to invade. He was caught by surprise in June 1941 when

Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union. The Soviet forces nearly collapsed as the Germans reached the outskirts of Leningrad and Moscow. However, the Soviet Union proved strong enough to defeat Nazi Germany, with help from its key World War II allies, Britain and the United States. The Soviet army occupied most of Eastern Europe (except Yugoslavia) and increasingly controlled the governments.

In 1945, the USSR became one of the five permanent members of the

United Nations Security Council

The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN) and is charged with ensuring international peace and security, recommending the admission of new UN members to the General Assembly, ...

along with the United States, Britain, France, and China, giving it the right to

veto

A veto is a legal power to unilaterally stop an official action. In the most typical case, a president or monarch vetoes a bill to stop it from becoming law. In many countries, veto powers are established in the country's constitution. Veto ...

any of the Security Council's resolutions (''see''

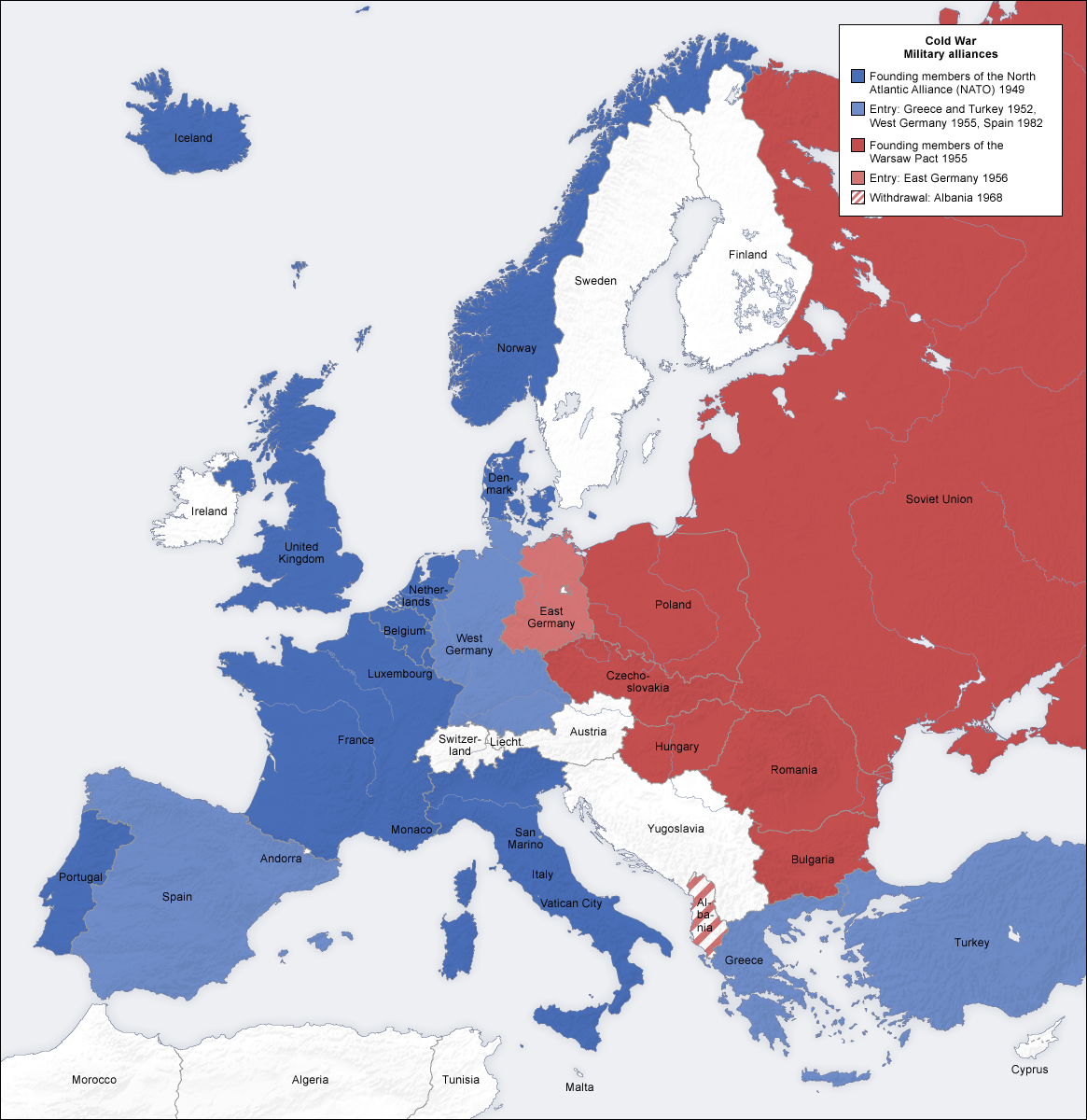

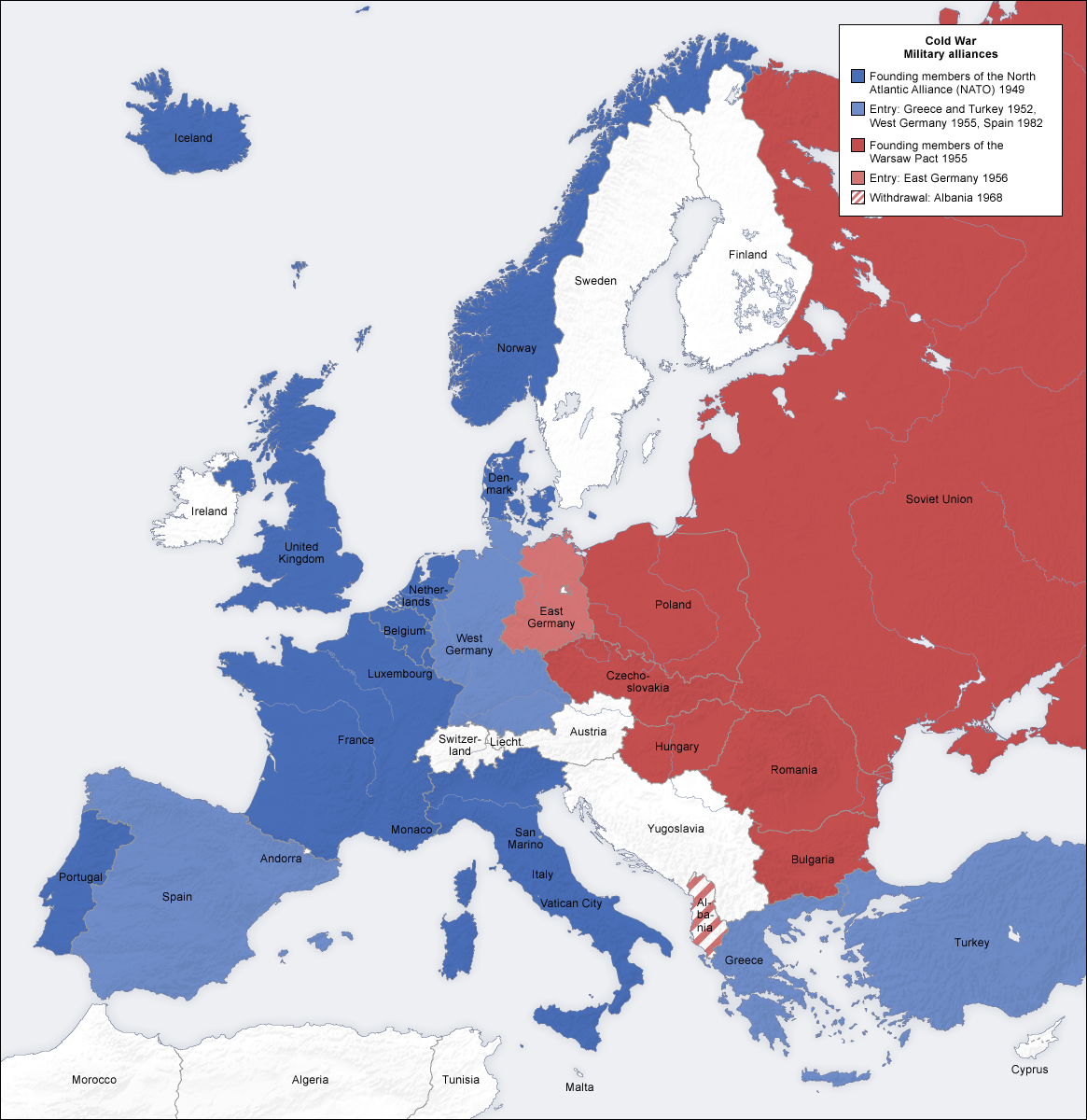

Soviet Union and the United Nations). By 1947, American and European anger at Soviet control over Eastern Europe led to a Cold War, with Western Europe organized economically with large sums of

Marshall Plan

The Marshall Plan (officially the European Recovery Program, ERP) was an American initiative enacted in 1948 to provide foreign aid to Western Europe. The United States transferred over $13 billion (equivalent of about $ in ) in economic re ...

money from Washington. Opposition to the danger of Soviet expansion formed the basis of the

NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two N ...

military alliance in 1949. There was no hot war, but the

Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because t ...

was fought diplomatically and politically across the world by the Soviet and NATO blocks.

The Kremlin controlled the socialist states that it established in the parts of Eastern Europe its army occupied in 1945. After eliminating capitalism and its advocates, it linked them to the USSR in terms of economics through

Comecon and later the military through the

Warsaw Pact

The Warsaw Pact (WP) or Treaty of Warsaw, formally the Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Mutual Assistance, was a collective defense treaty signed in Warsaw, Poland, between the Soviet Union and seven other Eastern Bloc socialist republi ...

. In 1948, relations with

Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia (; sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Jugoslavija, Југославија ; sl, Jugoslavija ; mk, Југославија ;; rup, Iugoslavia; hu, Jugoszlávia; rue, label= Pannonian Rusyn, Югославия, translit=Juhoslavij ...

disintegrated over mutual distrust between Stalin and

Tito

Tito may refer to:

People Mononyms

*Josip Broz Tito (1892–1980), commonly known mononymously as Tito, Yugoslav communist revolutionary and statesman

*Roberto Arias (1918–1989), aka Tito, Panamanian international lawyer, diplomat, and journal ...

. A similar

split happened with

Albania

Albania ( ; sq, Shqipëri or ), or , also or . officially the Republic of Albania ( sq, Republika e Shqipërisë), is a country in Southeastern Europe. It is located on the Adriatic and Ionian Seas within the Mediterranean Sea and share ...

in 1955. Like Yugoslavia and Albania, China was never controlled by the Soviet Army. The Kremlin wavered between the two factions fighting the Chinese Civil War, but ultimately supported the winner,

Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong pronounced ; also Romanization of Chinese, romanised traditionally as Mao Tse-tung. (26 December 1893 – 9 September 1976), also known as Chairman Mao, was a Chinese communist revolutionary who was the List of national founde ...

. Stalin and Mao both supported North Korea in its invasion of South Korea in 1950. But the United States and the United Nations mobilized the counterforce in the

Korean War

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Korean War

, partof = the Cold War and the Korean conflict

, image = Korean War Montage 2.png

, image_size = 300px

, caption = Clockwise from top:{ ...

(1950–53). Moscow provided air support but no ground troops; China sent in its large army that eventually stalemated the war. By 1960, disagreements between Beijing and Moscow had escalated out of control, and the two nations became bitter enemies in the contest for control of worldwide communist activities.

Tensions between the Soviet Union and the United States reached an all-time high during the 1962

Cuban Missile Crisis

The Cuban Missile Crisis, also known as the October Crisis (of 1962) ( es, Crisis de Octubre) in Cuba, the Caribbean Crisis () in Russia, or the Missile Scare, was a 35-day (16 October – 20 November 1962) confrontation between the United S ...

, in which Soviet missiles were placed on the island of Cuba well within range of US territory as a response to the failed

Bay of Pigs Invasion

The Bay of Pigs Invasion (, sometimes called ''Invasión de Playa Girón'' or ''Batalla de Playa Girón'' after the Playa Girón) was a failed military landing operation on the southwestern coast of Cuba in 1961 by Cuban exiles, covertly fin ...

and to deter more US attacks. This was retrospectively viewed as the closest the world ever came to a nuclear war. After the crisis was resolved, relations with the United States gradually eased into the 1970s, reaching a degree of détente as both Moscow and Beijing sought American favor.

In 1979, a socialist government took power in Afghanistan but was hard-pressed and requested military help from Moscow. The

Soviet army intervened to support the socialists, but found itself in a major confrontation. The presidency of Ronald Reagan in the United States was fiercely anti-Soviet, and mobilized its allies to support the guerrilla war against the Soviets in Afghanistan. The goal was to create something akin to the Vietnam War which would drain Soviet forces and morale. When

Mikhail Gorbachev

Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev (2 March 1931 – 30 August 2022) was a Soviet politician who served as the 8th and final leader of the Soviet Union from 1985 to the country's dissolution in 1991. He served as General Secretary of the Com ...

became the leader of the Soviet Union in 1985, he sought to

restructure the Soviet Union to resemble the

Scandinavian model of western

social democracy

Social democracy is a political, social, and economic philosophy within socialism that supports political and economic democracy. As a policy regime, it is described by academics as advocating economic and social interventions to promote s ...

and thus create a private sector economy. He removed Soviet troops from Afghanistan and began a hands-off approach in the USSR's relations with its Eastern European allies. This was well received by the United States, but it led to the breakaway of the Eastern European satellites in 1989, and the final collapse and

dissolution of the USSR in 1991. The new Russia, under

Boris Yeltsin

Boris Nikolayevich Yeltsin ( rus, Борис Николаевич Ельцин, p=bɐˈrʲis nʲɪkɐˈla(j)ɪvʲɪtɕ ˈjelʲtsɨn, a=Ru-Boris Nikolayevich Yeltsin.ogg; 1 February 1931 – 23 April 2007) was a Soviet and Russian politician wh ...

, was no longer communist.

The

Ministry of Foreign Affairs In many countries, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs is the government department responsible for the state's diplomacy, bilateral, and multilateral relations affairs as well as for providing support for a country's citizens who are abroad. The enti ...

implemented the foreign policies set by Stalin and after his death by the Politburo.

Andrei Gromyko

Andrei Andreyevich Gromyko (russian: Андрей Андреевич Громыко; be, Андрэй Андрэевіч Грамыка; – 2 July 1989) was a Soviet communist politician and diplomat during the Cold War. He served as ...

served as the Minister of Foreign Affairs for nearly thirty years (1957–1985).

Ideology and objectives of Soviet foreign policy

According to Soviet

Marxist–Leninist theorists, the basic character of Soviet foreign policy was set forth in Vladimir Lenin's ''

Decree on Peace'', adopted by the

Second Congress of Soviets

The All-Russian Congress of Soviets evolved from 1917 to become the supreme governing body of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic from 1918 until 1936, effectively. The 1918 Constitution of the Russian SFSR mandated that Congress sh ...

in November 1917. It set forth the dual nature of Soviet foreign policy, which encompasses both

proletarian internationalism

Proletarian internationalism, sometimes referred to as international socialism, is the perception of all communist revolutions as being part of a single global class struggle rather than separate localized events. It is based on the theory that ...

and

peaceful coexistence. On the one hand, proletarian internationalism refers to the common cause of the

working class

The working class (or labouring class) comprises those engaged in manual-labour occupations or industrial work, who are remunerated via waged or salaried contracts. Working-class occupations (see also " Designation of workers by collar colou ...

(or the

proletariat

The proletariat (; ) is the social class of wage-earners, those members of a society whose only possession of significant economic value is their labour power (their capacity to work). A member of such a class is a proletarian. Marxist philo ...

) of all countries in struggling to overthrow the

bourgeoisie

The bourgeoisie ( , ) is a social class, equivalent to the middle or upper middle class. They are distinguished from, and traditionally contrasted with, the proletariat by their affluence, and their great cultural and financial capital. Th ...

and to start a

communist revolution. Peaceful coexistence, on the other hand, refers to measures to ensure relatively peaceful government-to-government relations with capitalist states. Both policies can be pursued simultaneously: "Peaceful coexistence does not rule out but presupposes determined opposition to imperialist aggression and support for peoples defending their revolutionary gains or fighting foreign oppression."

[Text used in this cited section originally came from]

Chapter 10 of the Soviet Union Country Study

from the Library of Congress Country Studies

The Country Studies are works published by the Federal Research Division of the United States Library of Congress, freely available for use by researchers. No copyright is claimed on them. Therefore, they have been dedicated to the public domain a ...

project.

The Soviet commitment in practice to proletarian internationalism declined since the founding of the Soviet state, although this component of ideology still had some effect on later formulation and execution of Soviet foreign policy. Although pragmatic ''raisons d'état'' undoubtedly accounted for much of more recent Soviet foreign policy, the ideology of

class struggle

Class conflict, also referred to as class struggle and class warfare, is the political tension and economic antagonism that exists in society because of socio-economic competition among the social classes or between rich and poor.

The form ...

still played a role in providing a worldview and certain loose guidelines for action in the 1980s. Marxist–Leninist ideology reinforces other characteristics of political culture that create an attitude of competition and conflict with other states.

The general foreign policy goals of the Soviet Union were formalized in a party program ratified by delegates to the

Twenty-Seventh Party Congress in February–March 1986. According to the programme, "the main goals and guidelines of the CPSU's international policy" included ensuring favorable external conditions conducive to building

communism

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, ...

in the Soviet Union; eliminating the threat of world war;

disarmament

Disarmament is the act of reducing, limiting, or abolishing weapons. Disarmament generally refers to a country's military or specific type of weaponry. Disarmament is often taken to mean total elimination of weapons of mass destruction, such a ...

; strengthening the

world socialist system; developing equal and friendly relations with liberated (

third world

The term "Third World" arose during the Cold War to define countries that remained non-aligned with either NATO or the Warsaw Pact. The United States, Canada, Japan, South Korea, Western European nations and their allies represented the " First ...

) countries; peaceful coexistence with the capitalist countries; and solidarity with communist and revolutionary-democratic parties, the international workers' movement, and

national liberation struggles.

Although these general foreign policy goals were apparently conceived in terms of priorities, the emphasis and ranking of the priorities have changed over time in response to domestic and international stimuli. After

Mikhail Gorbachev

Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev (2 March 1931 – 30 August 2022) was a Soviet politician who served as the 8th and final leader of the Soviet Union from 1985 to the country's dissolution in 1991. He served as General Secretary of the Com ...

became

General Secretary of the Communist Party in 1985, for instance, some Western analysts discerned in the ranking of priorities a possible de-emphasis of Soviet support for

national liberation movements

National may refer to:

Common uses

* Nation or country

** Nationality – a ''national'' is a person who is subject to a nation, regardless of whether the person has full rights as a citizen

Places in the United States

* National, Maryland, ...

. Although the emphasis and ranking of priorities were subject to change, two basic goals of Soviet foreign policy remained constant: national security (safeguarding

Communist Party

A communist party is a political party that seeks to realize the socio-economic goals of communism. The term ''communist party'' was popularized by the title of '' The Manifesto of the Communist Party'' (1848) by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engel ...

rule through internal control and the maintenance of adequate military forces) and, since the late 1940s,

influence over Eastern Europe.

Many Western analysts have examined the way Soviet behavior in various regions and countries supported the general goals of Soviet foreign policy. These analysts have assessed Soviet behavior in the 1970s and 1980s as placing primary emphasis on relations with the United States, which was considered the foremost threat to the national security of the Soviet Union. Second priority was given to relations with

Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural, and socio-economic connotations. The vast majority of the region is covered by Russia, whi ...

(the other members of the

Warsaw Pact

The Warsaw Pact (WP) or Treaty of Warsaw, formally the Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Mutual Assistance, was a collective defense treaty signed in Warsaw, Poland, between the Soviet Union and seven other Eastern Bloc socialist republi ...

) and

Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's countries and territories vary depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the ancient Mediterranean ...

(the European members of the

North Atlantic Treaty Organization

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two No ...

). Third priority was given to the littoral or propinquitous states along the southern border of the Soviet Union:

Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with a small portion on the Balkan Peninsula ...

(a NATO member),

Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

,

Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan,; prs, امارت اسلامی افغانستان is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. Referred to as the Heart of Asia, it is borde ...

,

China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, most populous country, with a Population of China, population exceeding 1.4 billion, slig ...

,

Mongolia

Mongolia; Mongolian script: , , ; lit. "Mongol Nation" or "State of Mongolia" () is a landlocked country in East Asia, bordered by Russia to the north and China to the south. It covers an area of , with a population of just 3.3 million ...

,

North Korea

North Korea, officially the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK), is a country in East Asia. It constitutes the northern half of the Korean Peninsula and shares borders with China and Russia to the north, at the Yalu (Amnok) and T ...

, and

Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the n ...

. Regions near to, but not bordering, the Soviet Union were assigned fourth priority. These included the

greater Middle East,

South Asia

South Asia is the southern subregion of Asia, which is defined in both geographical and ethno-cultural terms. The region consists of the countries of Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka.;;;;; ...

, and

Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia, also spelled South East Asia and South-East Asia, and also known as Southeastern Asia, South-eastern Asia or SEA, is the geographical south-eastern region of Asia, consisting of the regions that are situated south of mainland ...

. Last priority was given to

sub-Saharan Africa

Sub-Saharan Africa is, geographically, the area and regions of the continent of Africa that lies south of the Sahara. These include West Africa, East Africa, Central Africa, and Southern Africa. Geopolitically, in addition to the List of sov ...

,

Oceania

Oceania (, , ) is a geographical region that includes Australasia, Melanesia, Micronesia, and Polynesia. Spanning the Eastern and Western hemispheres, Oceania is estimated to have a land area of and a population of around 44.5 million ...

, and

Latin America

Latin America or

* french: Amérique Latine, link=no

* ht, Amerik Latin, link=no

* pt, América Latina, link=no, name=a, sometimes referred to as LatAm is a large cultural region in the Americas where Romance languages — languages derived ...

, except insofar as these regions either provided opportunities for strategic basing or bordered on strategic naval straits or sea lanes. In general, Soviet foreign policy was most concerned with superpower relations (and, more broadly, relations between the members of NATO and the Warsaw Pact), but during the 1980s Soviet leaders pursued improved relations with all regions of the world as part of its foreign policy objectives.

Commissars and ministers

The

Ministry of Foreign Affairs In many countries, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs is the government department responsible for the state's diplomacy, bilateral, and multilateral relations affairs as well as for providing support for a country's citizens who are abroad. The enti ...

—called "Narkomindel" until 1949—drafted policy papers for the approval of Stalin and the Politburo, and then sent their orders out to the Soviet embassies. The following persons headed the Commissariat/Ministry as commissars (narkoms), ministers, and deputy ministers during the Soviet era:

1917–1939

There were three distinct phases in Soviet foreign policy between the conclusion of the

Russian Civil War

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Russian Civil War

, partof = the Russian Revolution and the aftermath of World War I

, image =

, caption = Clockwise from top left:

{{flatlist,

*Soldiers ...

and the

Nazi-Soviet Pact in 1939, determined in part by political struggles within the USSR, and in part by dynamic developments in international relations and the effect these had on Soviet security.

Lenin, once in power, believed the

October Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key mom ...

would ignite the world's socialists and lead to a "World Revolution." Lenin set up the

Communist International

The Communist International (Comintern), also known as the Third International, was a Soviet-controlled international organization founded in 1919 that advocated world communism. The Comintern resolved at its Second Congress to "struggle by ...

(Comintern) to

export revolution to the rest of Europe and Asia. Indeed, Lenin set out to "liberate" all of Asia from imperialist and capitalist control. The first stage not only was defeated in key attempts, but angered the other powers by its promise to overthrow capitalism.

World revolution

The Bolsheviks seized power in Russia in the

October Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key mom ...

of November 1917 but they could not stop the

Imperial German Army

The Imperial German Army (1871–1919), officially referred to as the German Army (german: Deutsches Heer), was the unified ground and air force of the German Empire. It was established in 1871 with the political unification of Germany under the l ...

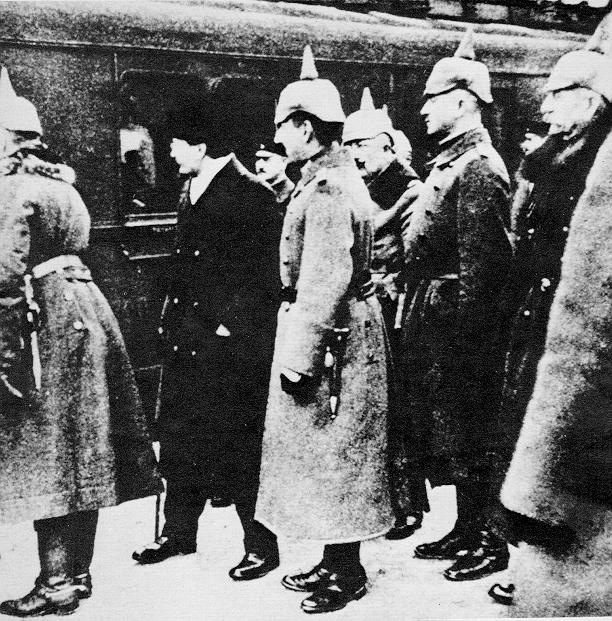

from advancing rapidly deep into Russia in

Operation Faustschlag. The Bolsheviks saw Russia as only the first step—they planned to incite revolutions against capitalism in every western country. The immediate threat was an unstoppable German attack. The Germans wanted to knock Russia out of the war so they could move their forces to the

Western Front Western Front or West Front may refer to:

Military frontiers

* Western Front (World War I), a military frontier to the west of Germany

*Western Front (World War II), a military frontier to the west of Germany

*Western Front (Russian Empire), a maj ...

in spring 1918 before the

American Expeditionary Force

The American Expeditionary Forces (A. E. F.) was a formation of the United States Army on the Western Front of World War I. The A. E. F. was established on July 5, 1917, in France under the command of General John J. Pershing. It fought along ...

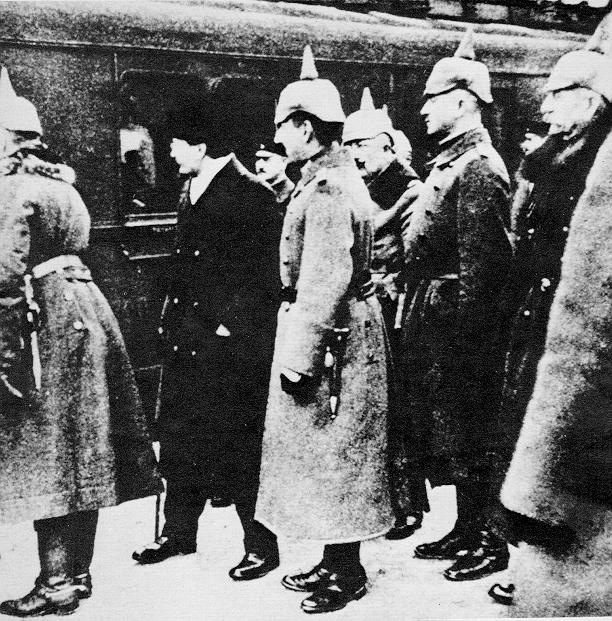

soldiers arrived in force. In early March 1918, after bitter internal debate, Russia agreed to harsh German peace terms at the

Treaty of Brest-Litovsk

The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (also known as the Treaty of Brest in Russia) was a separate peace treaty signed on 3 March 1918 between Russia and the Central Powers ( Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria, and the Ottoman Empire), that ended Russi ...

. Moscow lost control of the

Baltic States

The Baltic states, et, Balti riigid or the Baltic countries is a geopolitical term, which currently is used to group three countries: Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. All three countries are members of NATO, the European Union, the Eurozone ...

,

Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

,

Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inva ...

, and other areas that before the war produced much of Russia's food supply, industrial base, coal, and communication links with Western Europe." Russia's allies Britain and France felt betrayed: "The treaty was the ultimate betrayal of the Allied cause and sowed the seeds for the Cold War. With Brest-Litovsk the spectre of German domination in Eastern Europe threatened to become reality, and the Allies now began to think seriously about military intervention

n Russia"

In 1918 Britain sent in money and some troops to support the

anti-Bolshevik "White" counter-revolutionaries. France, Japan and the United States also sent forces to block German advances. In effect the Allies were helping the anti-Bolshevik White forces. The

Russian Civil War

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Russian Civil War

, partof = the Russian Revolution and the aftermath of World War I

, image =

, caption = Clockwise from top left:

{{flatlist,

*Soldiers ...

saw multiple uncoordinated attacks on the Bolsheviks from every direction. However, the Bolsheviks, operating a unified command from a central location, defeated all the opposition one by one and took full control of Russia, as well as breakaway provinces such as

Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inva ...

,

Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

,

Armenia

Armenia (), , group=pron officially the Republic of Armenia,, is a landlocked country in the Armenian Highlands of Western Asia.The UNbr>classification of world regions places Armenia in Western Asia; the CIA World Factbook , , and ''O ...

, and

Azerbaijan

Azerbaijan (, ; az, Azərbaycan ), officially the Republic of Azerbaijan, , also sometimes officially called the Azerbaijan Republic is a transcontinental country located at the boundary of Eastern Europe and Western Asia. It is a part of th ...

. The U.S. and France refused to deal with the now successful Communist regime because of its promise to support revolutions to overthrow governments everywhere. U.S. Secretary of State

Bainbridge Colby

Bainbridge Colby (December 22, 1869 – April 11, 1950) was an American politician and attorney who was a co-founder of the United States Progressive Party and Woodrow Wilson's last Secretary of State. Colby was a Republican until he helped co-f ...

stated:

:It is their

olshevikunderstanding that the very existence of Bolshevism in Russia, the maintenance of their own rule, depends, and must continue to depend, upon the occurrence of revolutions in all other great civilized nations, including the United States, which will overthrow and destroy their governments and set up Bolshevist rule in their stead. They have made it quite plain that they intend to use every means, including, of course, diplomatic agencies, to promote such revolutionary movements in other countries.

After Germany was defeated in November 1918 and the Whites were repulsed, the first priority for Moscow was instigating revolutions across Western Europe, above all Germany. It was the country that Lenin most admired and assumed to be most ready for revolution. Lenin also encouraged revolutions that failed in

Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwee ...

,

Bavaria

Bavaria ( ; ), officially the Free State of Bavaria (german: Freistaat Bayern, link=no ), is a state in the south-east of Germany. With an area of , Bavaria is the largest German state by land area, comprising roughly a fifth of the total l ...

and

Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Cr ...

from 1918 to 1920 - this support was solely political and economic, and the

Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian language, Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist R ...

did not participate in these revolutions. In 1920 the newly formed state of Poland expanded eastwards into the Russian territories of Ukraine and Belarus. The Red Army

retaliated, but was

defeated outside Warsaw in August 1920. Shortly afterwards, the RSFSR sued for peace, which was signed at the

Peace of Riga

The Peace of Riga, also known as the Treaty of Riga ( pl, Traktat Ryski), was signed in Riga on 18 March 1921, among Poland, Soviet Russia (acting also on behalf of Soviet Belarus) and Soviet Ukraine. The treaty ended the Polish–Soviet Wa ...

on 18 March 1921. The RSFSR recompensed 30 million

roubles

The ruble (American English) or rouble (Commonwealth English) (; rus, рубль, p=rublʲ) is the currency unit of Belarus and Russia. Historically, it was the currency of the Russian Empire and of the Soviet Union.

, currencies named ''ru ...

, as well as sizeable territory in Belarus and Ukraine.

Independent revolutions had failed to overthrow capitalism. Moscow pulled back from military action and set up the

Comintern

The Communist International (Comintern), also known as the Third International, was a Soviet-controlled international organization founded in 1919 that advocated world communism. The Comintern resolved at its Second Congress to "struggle by ...

, designed to foster local communist parties under Kremlin control.

[Service, ''Comrades! A history of world communism'' (2007) 107-18.]

Success in Central Asia and the Caucasus

Lenin's plans failed, although Russia did manage to hold onto the Central Asian and Caucasian domains that had been part of the

Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War ...

. The revolutionary stage ended after the Soviet defeat in the

Battle of Warsaw during the

Soviet-Polish War of 1920-21. As Europe's revolutions were crushed and revolutionary zeal dwindled, the Bolsheviks shifted their ideological focus from the

world revolution

World revolution is the Marxist concept of overthrowing capitalism in all countries through the conscious revolutionary action of the organized working class. For theorists, these revolutions will not necessarily occur simultaneously, but whe ...

and building socialism around the globe to building socialism inside the Soviet Union, while keeping some of the rhetoric and operations of the Comintern continuing. In the mid-1920s, a policy of peaceful co-existence began to emerge, with Soviet diplomats attempting to end the country's isolation, and concluding bilateral arrangements with capitalist governments. An agreement was reached with Germany, Europe's other pariah, in the

Treaty of Rapallo in 1922. At the same time the Rapallo treaty was signed it set up a secret system for hosting large-scale training and research facilities for the

German army

The German Army (, "army") is the land component of the armed forces of Germany. The present-day German Army was founded in 1955 as part of the newly formed West German ''Bundeswehr'' together with the ''Marine'' (German Navy) and the ''Luftwaf ...

and air force, despite the strict prohibitions on Germany in the

Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June 1 ...

. These facilities operated until 1933.

The Soviet Union finalized a treaty of friendship with

Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan,; prs, امارت اسلامی افغانستان is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. Referred to as the Heart of Asia, it is borde ...

, which had gained full independence following the

Third Anglo-Afghan War

The Third Anglo-Afghan War; fa, جنگ سوم افغان-انگلیس), also known as the Third Afghan War, the British-Afghan War of 1919, or in Afghanistan as the War of Independence, began on 6 May 1919 when the Emirate of Afghanistan inv ...

. The Afghan king,

Amanullah Khan

Ghazi Amanullah Khan (Pashto and Dari: ; 1 June 1892 – 25 April 1960) was the sovereign of Afghanistan from 1919, first as Emir and after 1926 as King, until his abdication in 1929. After the end of the Third Anglo-Afghan War in August 1 ...

, wrote to Moscow stressing his desire for permanent friendly relations; Lenin replied congratulating him and the Afghans for their defense. The Soviets saw possibilities in an alliance with Afghanistan against the United Kingdom, such as using it as a base for a revolutionary advance towards

British-controlled India. The treaty of friendship was finalized in 1921.

Communist International

The Communist International (Comintern), (1919–1943), was an international organization of

communist parties

A communist party is a political party that seeks to realize the socio-economic goals of communism. The term ''communist party'' was popularized by the title of '' The Manifesto of the Communist Party'' (1848) by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. ...

.

Obstensibly a new group to replace the former

Second International

The Second International (1889–1916) was an organisation of Labour movement, socialist and labour parties, formed on 14 July 1889 at two simultaneous Paris meetings in which delegations from twenty countries participated. The Second Internatio ...

after it had collapsed because of World War I, it served as an extension of Soviet foreign policy.

It was headed by

Grigory Zinoviev

Grigory Yevseyevich Zinoviev, . Transliterated ''Grigorii Evseevich Zinov'ev'' according to the Library of Congress system. (born Hirsch Apfelbaum, – 25 August 1936), known also under the name Ovsei-Gershon Aronovich Radomyslsky (russian: Ов ...

(1919–26) and based in the

Kremlin

The Kremlin ( rus, Московский Кремль, r=Moskovskiy Kreml', p=ˈmɐˈskofskʲɪj krʲemlʲ, t=Moscow Kremlin) is a fortified complex in the center of Moscow founded by the Rurik dynasty. It is the best known of the kremlins (Ru ...

; it reported to Lenin and later Stalin. Lenin envisioned the national branches not as political parties, but "as a centralized quasi-religious, and quasi-military movement devoted to the revolution and to service of the Soviet state." Commentators compared it to the

Jesuit order

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders ...

, with its

vow of obedience. It coordinated the different parties and issued orders that they obeyed. The Comintern resolved at its

Second Congress to "struggle by all available means, including armed force, for the overthrow of the international bourgeoisie and the creation of an international Soviet republic as a transition stage to the complete abolition of the state". That policy was soon dropped by 1921 because it interfered with the decision to seek friendly relations with capitalistic nations. The new economic policy at home required trade with the West and bank credits if possible. The main obstacle was Moscow's refusal to honor Tsarist era debts. The Comintern was officially dissolved by Stalin in 1943 to avoid antagonizing its new allies against Germany, the United States and Great Britain.

Stalin: Socialism in one country

Trotsky argued for the continuation of the revolutionary process, in terms of his theory of

permanent revolution

Permanent revolution is the strategy of a revolutionary class pursuing its own interests independently and without compromise or alliance with opposing sections of society. As a term within Marxist theory, it was first coined by Karl Marx and F ...

. After Lenin's death in 1924, Trotsky was defeated by Stalin and

Nikolai Bukharin

Nikolai Ivanovich Bukharin (russian: Никола́й Ива́нович Буха́рин) ( – 15 March 1938) was a Bolshevik revolutionary, Soviet politician, Marxist philosopher and economist and prolific author on revolutionary theory. ...

. Trotsky was sent into exile and in 1940 was assassinated on Stalin's orders.

Stalin's main policy was

socialism in one country

Socialism in one country was a Soviet state policy to strengthen socialism within the country rather than socialism globally. Given the defeats of the 1917–1923 European communist revolutions, Joseph Stalin and Nikolai Bukharin encouraged th ...

. He focused modernization of the Soviet Union, developing manufacturing, building infrastructure and improving agriculture. Expansion and wars were no longer on the agenda. The Kremlin-sponsored the

united front

A united front is an alliance of groups against their common enemies, figuratively evoking unification of previously separate geographic fronts and/or unification of previously separate armies into a front. The name often refers to a political ...

policy, with foreign Communist parties taking the lead in education and national liberation movements. The goal was

opposition to fascism, especially the

Nazi

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in ...

variety.

The high point of the United Front was the partnership in

China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, most populous country, with a Population of China, population exceeding 1.4 billion, slig ...

between the

Chinese Communist Party

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP), officially the Communist Party of China (CPC), is the founding and sole ruling party of the People's Republic of China (PRC). Under the leadership of Mao Zedong, the CCP emerged victorious in the Chinese Ci ...

and the

nationalist

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: Th ...

Kuomintang

The Kuomintang (KMT), also referred to as the Guomindang (GMD), the Nationalist Party of China (NPC) or the Chinese Nationalist Party (CNP), is a major political party in the Republic of China, initially on the Chinese mainland and in Ta ...

. The

United Front policy in China effectively crashed to ruin in 1927, when Kuomintang leader

Chiang Kai-shek

Chiang Kai-shek (31 October 1887 – 5 April 1975), also known as Chiang Chung-cheng and Jiang Jieshi, was a Chinese Nationalist politician, revolutionary, and military leader who served as the leader of the Republic of China (ROC) from 1928 ...

massacred the native Communists and expelled all of his Soviet advisors, notably

Mikhail Borodin

Mikhail Markovich Gruzenberg, known by the alias Borodin, zh, 鮑羅廷 (9 July 1884 – 29 May 1951), was a Bolshevik revolutionary and Communist International (Comintern) agent. He was an advisor to Sun Yat-sen and the Kuomintang (KMT) in ...

. A

short war erupted in 1929 as the Soviets successfully fought to keep control of the

Chinese Eastern Railway in Manchuria.

After defeating all his opponents from both the left (led by Trotsky and

Grigory Zinoviev

Grigory Yevseyevich Zinoviev, . Transliterated ''Grigorii Evseevich Zinov'ev'' according to the Library of Congress system. (born Hirsch Apfelbaum, – 25 August 1936), known also under the name Ovsei-Gershon Aronovich Radomyslsky (russian: Ов ...

) and the right (led by Bukharin), Stalin was in full charge. He began the wholesale

collectivization

Collective farming and communal farming are various types of, "agricultural production in which multiple farmers run their holdings as a joint enterprise". There are two broad types of communal farms: agricultural cooperatives, in which member- ...

of Soviet agriculture, accompanied by a massive program of

planned industrialization.

Respectability and normal relations

After 1921 the main foreign policy goal was to be treated as a normal country by the major powers, and open trade relations and diplomatic recognition. There was no more crusading for world revolution, which the Communist Party leadership began to recognize would not come and that Soviet Russia would have to reach some form of temporary accommodation with the "bourgeois" capitalist countries.

The first breakthrough came in 1921 with the

Anglo-Soviet Trade Agreement

The Anglo-Soviet Trade Agreement was an agreement signed on 16 March 1921 to facilitate trade between the United Kingdom and the Russian Socialist Federal Soviet Republic. It was signed by Robert Horne, Chancellor of the Exchequer and Leonid Kras ...

that signified the de facto recognition of the Soviet state. The United States refused recognition until 1933, however,

Henry Ford

Henry Ford (July 30, 1863 – April 7, 1947) was an American industrialist, business magnate, founder of the Ford Motor Company, and chief developer of the assembly line technique of mass production. By creating the first automobile that ...

and other capitalists invested heavily in the Soviet Union, bringing along modern management techniques and new industrial technology.

Georgy Chicherin

Georgy Vasilyevich Chicherin (24 November 1872 – 7 July 1936), also spelled Tchitcherin, was a Russian Marxist revolutionary and a Soviet politician who served as the first People's Commissar for Foreign Affairs in the Soviet government from ...

was Soviet foreign minister, from 1918 to 1930. He worked against the League of Nations and attempted to lure the

Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic (german: link=no, Weimarer Republik ), officially named the German Reich, was the government of Germany from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a Constitutional republic, constitutional federal republic for the first time in ...

into an alliance with Moscow, an effort aided by his close personal friendship with German Ambassador

Ulrich von Brockdorff-Rantzau.

The League made several efforts to develop better relations with Russia but were always rebuffed because the Soviets regarded the League as simply an alliance of hostile, capitalist powers.

The USSR did not seek admission to the

League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference th ...

until 1934, when it joined with French backing.

Rapallo Treaty 1922

The

Genoa Conference of 1922 brought the Soviet Union and Germany for the first time into negotiations with the major European powers. The conference broke down when France insisted that Germany pay more in

reparations

Reparation(s) may refer to:

Christianity

* Restitution (theology), the Christian doctrine calling for reparation

* Acts of reparation, prayers for repairing the damages of sin

History

*War reparations

**World War I reparations, made from ...

, and demanded in Moscow start paying off the czarist era debts that it had repudiated. The Soviet Union and Germany were both pariah countries, deeply distrusted. The solution was to get together at the nearby city of

Rapallo

Rapallo ( , , ) is a municipality in the Metropolitan City of Genoa, located in the Liguria region of northern Italy.

As of 2017 it had 29,778 inhabitants. It lies on the Ligurian Sea coast, on the Tigullio Gulf, between Portofino and Chiav ...

,

Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

, where they quickly negotiated the

Treaty of Rapallo.

In a friendly agreement, they made a clean break with the past, repudiating all old financial and territorial obligations and agreeing to normalize diplomatic and economic relations. Secretly, the two sides established elaborate military cooperation, while publicly denying it. This enabled Germany to rebuild its army and air force secretly at camps in the Soviet Union, in violation of the Treaty of Versailles.

Great Britain

=Trade and recognition

=

At the direction of the Comintern, by 1937, 10% of

Communist Party of Great Britain

The Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) was the largest communist organisation in Britain and was founded in 1920 through a merger of several smaller Marxist groups. Many miners joined the CPGB in the 1926 general strike. In 1930, the CPGB ...

members were operating secretly inside the

British Labour Party

The Labour Party is a political party in the United Kingdom that has been described as an alliance of social democrats, democratic socialists and trade unionists. The Labour Party sits on the centre-left of the political spectrum. In all ...

, campaigning to change its policy on affiliation and engineer a

Popular Front

A popular front is "any coalition of working-class and middle-class parties", including liberal and social democratic ones, "united for the defense of democratic forms" against "a presumed Fascist assault".

More generally, it is "a coalition ...

.

The Labour leadership fought back and became bitter enemies of Communism. When Labour came to power in the

1945 general election, it was increasingly hostile to the Soviet Union and supported the Cold War.

=Zinoviev letter

=

The

Zinoviev letter was a document published by the London ''

Daily Mail

The ''Daily Mail'' is a British daily middle-market tabloid newspaper and news websitePeter Wilb"Paul Dacre of the Daily Mail: The man who hates liberal Britain", ''New Statesman'', 19 December 2013 (online version: 2 January 2014) publish ...

'' newspaper four days before the

British general election in 1924. It purported to be a directive from

Grigory Zinoviev

Grigory Yevseyevich Zinoviev, . Transliterated ''Grigorii Evseevich Zinov'ev'' according to the Library of Congress system. (born Hirsch Apfelbaum, – 25 August 1936), known also under the name Ovsei-Gershon Aronovich Radomyslsky (russian: Ов ...

, the head of the

Communist International

The Communist International (Comintern), also known as the Third International, was a Soviet-controlled international organization founded in 1919 that advocated world communism. The Comintern resolved at its Second Congress to "struggle by ...

in Moscow, to the

Communist Party of Great Britain

The Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) was the largest communist organisation in Britain and was founded in 1920 through a merger of several smaller Marxist groups. Many miners joined the CPGB in the 1926 general strike. In 1930, the CPGB ...

, ordering it to engage in seditious activities. It said the resumption of diplomatic relations (by a

Labour government) would hasten the radicalization of the

British working class

The social structure of the United Kingdom has historically been highly influenced by the concept of social class, which continues to affect British society today. British society, like its European neighbours and most societies in world history, w ...

. This would have constituted a significant interference in

British politics, and as a result, it was deeply offensive to British voters, turning them against the Labour Party. The letter seemed authentic at the time, but historians now agree it was a forgery. The letter aided the

Conservative Party

The Conservative Party is a name used by many political parties around the world. These political parties are generally right-wing though their exact ideologies can range from center-right to far-right.

Political parties called The Conservative P ...

under

Stanley Baldwin

Stanley Baldwin, 1st Earl Baldwin of Bewdley, (3 August 186714 December 1947) was a British Conservative Party politician who dominated the government of the United Kingdom between the world wars, serving as prime minister on three occasions, ...

, by hastening the collapse of the

Liberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world. The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left.

__TOC__ Active liberal parties

This is a li ...

vote that produced a Conservative landslide against

Ramsay MacDonald

James Ramsay MacDonald (; 12 October 18669 November 1937) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, the first who belonged to the Labour Party, leading minority Labour governments for nine months in 1924 ...

's Labour Party.

argued that the most important impact was on the psychology of Labourites, who for years afterward blamed their defeat on foul play, thereby misunderstanding the political forces at work and postponing necessary reforms in the Labour Party.

United States

In the 1920s, the Republican governments in Washington refused to recognize the USSR. However some American businesses, led by

Henry Ford

Henry Ford (July 30, 1863 – April 7, 1947) was an American industrialist, business magnate, founder of the Ford Motor Company, and chief developer of the assembly line technique of mass production. By creating the first automobile that ...

, opened close relations. The Soviets greatly admired American technology and welcomed help in achieving the ambitious industrial goals of Stalin's

First Five-Year Plan

The first five-year plan (russian: I пятилетний план, ) of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) was a list of economic goals, created by Communist Party General Secretary Joseph Stalin, based on his policy of socialism in ...

. Ford built modern factories and trained Soviet engineers.

President Franklin Roosevelt recognized the USSR in 1933, in the expectation that trade would soar and help the US out of the depression. That did not happen, but Roosevelt maintained good relations until his death in 1945.

Attack social democratic parties

In the late 1920s and early 1930s, Stalin insisted on a policy of fighting against non-communist socialist movements everywhere. This new radical phase was paralleled by the formulation of a new doctrine in the International, that of the so-called

Third Period, an ultra-left switch in policy, which argued that

social democracy

Social democracy is a political, social, and economic philosophy within socialism that supports political and economic democracy. As a policy regime, it is described by academics as advocating economic and social interventions to promote s ...

, whatever shape it took, was a form of

social fascism

Social fascism (also socio-fascism) was a theory that was supported by the Communist International (Comintern) and affiliated communist parties in the early 1930s that held that social democracy was a variant of fascism because it stood in the way ...

, socialist in theory but

fascist

Fascism is a far-right, authoritarian, ultra-nationalist political ideology and movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and political and cultural liberalism, a belief in natural social hierarchy and the ...

in practice. All foreign Communist parties – increasingly agents of Soviet policy – were to concentrate their efforts in a struggle against their rivals in the working-class movement, ignoring the threat of real fascism. There were to be no united fronts against a greater enemy.

Battling Social Democracy in Germany 1927-1932

In Germany, Stalin gave a high priority to an anti-capitalist revolution in Germany. His

German Communist Party

The German Communist Party (german: Deutsche Kommunistische Partei, ) is a communist party in Germany. The DKP supports left positions and was an observer member of the European Left. At the end of February 2016 it left the European party.

His ...

(KPD) split the working-class vote with the moderate

Social Democratic Party

The name Social Democratic Party or Social Democrats has been used by many political parties in various countries around the world. Such parties are most commonly aligned to social democracy as their political ideology.

Active parties

For ...

. The SPD was the historic social democratic party in Germany, and tempered its Marxism to drop revolutionary goals and instead focus on systematic improvement of the condition of the working-class. This approach ran contrary to the goals and beliefs of the KPD which considered such short term consessions for the working that served only to delay the revolution. In the

Reichstag, the KPD sought to overthrow the Weimar regie, which was historically controlled by a moderate coalition of liberals, Catholics, and the social democrats. As the

Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that created and supported t ...

grew rapidly throughout the early 1930s, winning support among

Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

workers and financial capitalists, this system became increasingly undermined by political extremists. There was some fighting between the KPD and the Nazis in Germany's industrial cities. According to George Stein, a secret major military collaboration between Russia and Germany began in the early 1920s. Both sides benefitted from operational activities at the bases of Lipetsk, Kazan, and Torski. When Hitler and his Nazis came to power in 1933, the collaboration ended because Stalin feared the dangerous expansionist policy of the Nazis and neither he nor Hitler would risk further cooperation. Instead Stalin ordered Germans to cooperate with the SPD, but Hitler quickly suppressed both. With the KPD destroyed, a few leaders managed to escape into exile in Moscow, some of whom would executed and others become leaders of East Germany in 1945. Simultaneously in Germany, the Nazis completely destroyed the SPD, imprisoning its leaders or forcing them into exile as well.

Popular Fronts 1933-1939

Communists and parties on the left were increasingly threatened by the growth of the Nazi movement. Hitler came to power in January 1933 and rapidly consolidated his control over Germany, destroyed the communist and socialist movements in Germany, and rejected the restraints imposed by the Versailles treaty. Stalin in 1934 reversed his decision in 1928 to attack socialists, and introduced his new plan: the "popular front." It was a coalition of anti-fascist parties usually organized by the local communists acting under instructions from the Comintern. The new policy was to work with all parties on the left and center in a multiparty coalition against fascism and Nazi Germany in particular. The new slogan was: "The People's Front Against Fascism and War". Under this policy, Communist Parties were instructed to form broad alliances with all anti-fascist parties with the aim of both securing social advance at home and a military alliance with the USSR to isolate the fascist dictatorships. The "Popular Fronts" thus formed proved to be successful in only a few countries, and only for a few years each, forming the government in

France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

,

Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in the western part of South America. It is the southernmost country in the world, and the closest to Antarctica, occupying a long and narrow strip of land between the Andes to the eas ...

and

Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, ...

, and also China. It was not a political success elsewhere. The Popular Front approach played a major role in

Resistance movements

A resistance movement is an organized effort by some portion of the civil population of a country to withstand the legally established government or an occupying power and to disrupt civil order and stability. It may seek to achieve its objectives ...

in

France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

and other countries conquered by Germany after 1939. After the war it played a major role in French and Italian politics.

Hand-in-hand with the promotion of Popular Fronts,

Maxim Litvinov

Maxim Maximovich Litvinov (; born Meir Henoch Wallach; 17 July 1876 – 31 December 1951) was a Russian revolutionary and prominent Soviet statesman and diplomat.

A strong advocate of diplomatic agreements leading towards disarmament, Litvinov w ...

, the Soviet Commissar for Foreign Affairs between 1930 and 1939, aimed at closer alliances with Western governments, and placed ever greater emphasis on

collective security

Collective security can be understood as a security arrangement, political, regional, or global, in which each state in the system accepts that the security of one is the concern of all, and therefore commits to a collective response to threats ...

. The new policy led to the Soviet Union joining the

League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference th ...

in 1934 and the subsequent non-aggression pacts with France and Czechoslovakia. In the League the Soviets were active in demanding action against imperialist aggression, a particular danger to them after the 1931

Japanese invasion of Manchuria

The Empire of Japan's Kwantung Army invaded Manchuria on 18 September 1931, immediately following the Mukden Incident. At the war's end in February 1932, the Japanese established the puppet state of Manchukuo. Their occupation lasted until the ...

, which eventually resulted in the Soviet-Japanese

Battle of Khalkhin Gol

The Battles of Khalkhin Gol (russian: Бои на Халхин-Голе; mn, Халхын голын байлдаан) were the decisive engagements of the undeclared Soviet–Japanese border conflicts involving the Soviet Union, Mongolia, ...

.

Ignoring the agreement it signed to avoid involvement in the

Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlism, Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebeli ...

, the USSR sent arms and troops and organized volunteers to fight for the

republican government. Communist forces systematically killed their old enemies the

Spanish anarchists

Anarchism in Spain has historically gained some support and influence, especially before Francisco Franco's victory in the Spanish Civil War of 1936–1939, when it played an active political role and is considered the end of the golden age of cl ...

, even though they were on the same Republican side. The Spanish government sent its entire treasury to Moscow for safekeeping, but it was never returned.

The

Munich Agreement

The Munich Agreement ( cs, Mnichovská dohoda; sk, Mníchovská dohoda; german: Münchner Abkommen) was an agreement concluded at Munich on 30 September 1938, by Germany, the United Kingdom, France, and Italy. It provided "cession to Germany ...

of 1938, the first stage in the dismemberment of Czechoslovakia, gave rise to Soviet fears that they were likely to be abandoned in a possible war with Germany.

In the face of continually dragging and seemingly hopeless negotiations with Britain and France, a new cynicism and hardness entered Soviet foreign relations when Litvinov was replaced by

Vyacheslav Molotov

Vyacheslav Mikhaylovich Molotov. ; (;. 9 March Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O._S._25_February.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New Style dates">O. S. 25 February">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dat ...

in May 1939.

Alliance with France

By 1935, Moscow and Paris identified

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

as the main military, diplomatic, ideological and economic threat. Germany could probably defeat each one separately in a war, but would avoid a

two-front war

According to military terminology, a two-front war occurs when opposing forces encounter on two geographically separate fronts. The forces of two or more allied parties usually simultaneously engage an opponent in order to increase their chance ...

against both of them simultaneously. The solution, therefore, was a military alliance. It was pursued by

Louis Barthou

Jean Louis Barthou (; 25 August 1862 – 9 October 1934) was a French politician of the Third Republic who served as Prime Minister of France for eight months in 1913. In social policy, his time as prime minister saw the introduction (in Jul ...

, the French foreign minister, but he was assassinated in October 1934 and his successor,

Pierre Laval

Pierre Jean Marie Laval (; 28 June 1883 – 15 October 1945) was a French politician. During the Third Republic, he served as Prime Minister of France from 27 January 1931 to 20 February 1932 and 7 June 1935 to 24 January 1936. He again occ ...

, was more inclined to Germany. However, after the declaration of

German rearmament

German rearmament (''Aufrüstung'', ) was a policy and practice of rearmament carried out in Germany during the interwar period (1918–1939), in violation of the Treaty of Versailles which required German disarmament after WWI to prevent Germ ...

in March 1935 the French government forced the reluctant Laval to conclude a treaty. Written in 1935, it took effect in 1936. Both Paris and Moscow hoped other countries would join in and

Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

to sign treaties with both France and the Soviet Union. Prague wanted to use the USSR as a counterweight against the growing strength of Nazi Germany. Poland might make a good partner too, but it refused to join in. The military provisions were practically useless because of multiple conditions and the requirement that the United Kingdom and

Fascist Italy approve any action. The effectiveness was undermined even further by the French government's insistent refusal to accept a military convention stipulating the way in which the two armies would coordinate actions in the event of war with Germany. The result was a symbolic pact of friendship and mutual assistance of little consequence other than raising the prestige of both parties.

The Treaty marked a large scale shift in Soviet policy in the Comintern from a pro-revisionist stance against the

Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June 1 ...

to a more western-oriented foreign policy as championed by

Maxim Litvinov

Maxim Maximovich Litvinov (; born Meir Henoch Wallach; 17 July 1876 – 31 December 1951) was a Russian revolutionary and prominent Soviet statesman and diplomat.

A strong advocate of diplomatic agreements leading towards disarmament, Litvinov w ...

. Hitler justified the

remilitarization of the Rhineland

The remilitarization of the Rhineland () began on 7 March 1936, when German military forces entered the Rhineland, which directly contravened the Treaty of Versailles and the Locarno Treaties. Neither France nor Britain was prepared for a milit ...

by the ratification of the treaty in the French parliament, claiming that he felt threatened by the pact. However, after 1936, the French lost interest, and all parties in Europe realized the treaty was effectively a dead letter. The

appeasement

Appeasement in an international context is a diplomatic policy of making political, material, or territorial concessions to an aggressive power in order to avoid conflict. The term is most often applied to the foreign policy of the UK governme ...

policies of the prime ministers of Britain and France,

Neville Chamberlain

Arthur Neville Chamberlain (; 18 March 18699 November 1940) was a British politician of the Conservative Party who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from May 1937 to May 1940. He is best known for his foreign policy of appeaseme ...

and

Édouard Daladier

Édouard Daladier (; 18 June 1884 – 10 October 1970) was a French Radical-Socialist (centre-left) politician, and the Prime Minister of France who signed the Munich Agreement before the outbreak of World War II.

Daladier was born in Carpe ...

were widely held because they seemed to promise what Chamberlain called "peace for our time." However, by early 1939 it was clear that it further encouraged Nazi aggression.

The Soviet Union was not invited to the critical

Munich conference in late September 1938, where Britain, France, and Italy appeased Hitler by giving in to his demands to take over the

Sudetenland

The Sudetenland ( , ; Czech and sk, Sudety) is the historical German name for the northern, southern, and western areas of former Czechoslovakia which were inhabited primarily by Sudeten Germans. These German speakers had predominated in the ...

, a largely German-speaking area of Western Czechoslovakia. Distrust was high in all directions. Leaders in London and Paris felt that Stalin wanted to see a major war between the capitalist nations Germany on the one hand, and Britain and France on the other, in order to advance the prospects of a working-class revolution in Europe. Meanwhile, Stalin felt the Western Powers were plotting to embroil Germany and Russia in war in order to preserve bourgeois capitalism.

After Hitler took over all of Czechoslovakia in 1939, proving appeasement was a disaster, Britain and France tried to involve the Soviet Union and a real military alliance. Their attempts were futile because Poland refused to allow any Soviet troops on its soil.

Diplomats purged

In 1937–1938, Stalin took total personal control of the party, by purging and executing tens of thousands of high-level and mid-level party officials, especially the

Old Bolshevik

Old Bolshevik (russian: ста́рый большеви́к, ''stary bolshevik''), also called Old Bolshevik Guard or Old Party Guard, was an unofficial designation for a member of the Bolshevik faction of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Par ...

s who had joined before 1917. The entire diplomatic service was downsized; many consular offices abroad were closed, and restrictions were placed on the activities and movements of foreign diplomats in the USSR. About a third of all foreign ministry officials were shot or imprisoned, including 62 of the 100 most senior officials. Key ambassadorial posts abroad, such as those in

Tokyo

Tokyo (; ja, 東京, , ), officially the Tokyo Metropolis ( ja, 東京都, label=none, ), is the capital and largest city of Japan. Formerly known as Edo, its metropolitan area () is the most populous in the world, with an estimated 37.46 ...

,

Warsaw

Warsaw ( pl, Warszawa, ), officially the Capital City of Warsaw,, abbreviation: ''m.st. Warszawa'' is the capital and largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the River Vistula in east-central Poland, and its population is officiall ...

,

Washington

Washington commonly refers to:

* Washington (state), United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A metonym for the federal government of the United States

** Washington metropolitan area, the metropolitan area centered o ...

,

Bucharest

Bucharest ( , ; ro, București ) is the capital and largest city of Romania, as well as its cultural, industrial, and financial centre. It is located in the southeast of the country, on the banks of the Dâmbovița River, less than north o ...

, and

Budapest

Budapest (, ; ) is the capital and most populous city of Hungary. It is the ninth-largest city in the European Union by population within city limits and the second-largest city on the Danube river; the city has an estimated population o ...

, were vacant.

Non-Aggression Pact with Germany (1939–1941)

In 1938–1939, the Soviet Union attempted to form strong military alliances with Germany's enemies, including Poland, France, and Great Britain, but they all refused. In an effort to delay a Nazi invasion and build up the Soviet military, Stalin made a non-aggression pact with Hitler and received control of a large swath of Eastern Europe, including the Baltic countries. The agreement provided for large sales of Russian grain and oil to Germany, while Germany would share its military technology with the Soviet Union. The ensuing

Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact

, long_name = Treaty of Non-Aggression between Germany and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics

, image = Bundesarchiv Bild 183-H27337, Moskau, Stalin und Ribbentrop im Kreml.jpg

, image_width = 200

, caption = Stalin and Ribbentrop shaking ...

astonished the world and signaled the war would start very soon. French historian

François Furet

François Furet (; 27 March 1927 – 12 July 1997) was a French historian and president of the Saint-Simon Foundation, best known for his books on the French Revolution. From 1985 to 1997, Furet was a professor of French history at the University ...

says, "The pact signed in Moscow by Ribbentrop and Molotov on 23 August 1939 inaugurated the alliance between the USSR and Nazi Germany. It was presented as an alliance and not just a nonaggression pact." Other historians dispute the characterization of this treaty as an "alliance," because Hitler secretly intended to

invade the USSR in the future.

World War II

Stalin controlled the foreign policy of the Soviet Union, with

Vyacheslav Molotov

Vyacheslav Mikhaylovich Molotov. ; (;. 9 March Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O._S._25_February.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New Style dates">O. S. 25 February">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dat ...